Abstract

Biological invasions are major threats to global biodiversity, and mapping their distribution is essential to prioritizing management efforts. The Pinaceae family (hereafter pines) includes invasive trees, particularly in Southern Hemisphere regions where they are non-native. These invasions can increase the severity of fires in wildland–urban interfaces (WUIs). We mapped pine invasion in the Bariloche WUI (≈150,000 ha, northwest Patagonia, Argentina) using supervised land cover classification of Sentinel-2 imagery with a Random Forest algorithm on Google Earth Engine, achieving 90% overall accuracy but underestimating the pine invasion area by about 25%. We then assessed in which main vegetation context pine invasions occurred relying on major vegetation units across the precipitation gradient of our study area. Invasions cover 2% of the study area, mainly in forests (61%), steppes (25.4%), and shrublands (13.4%). Most invaded areas (89.1%) are on private land; nearly 70% are on large properties (>10 ha), where state financial incentives could support removal. Another 13.5% occur on many small properties (<1 ha), where awareness campaigns could enable decentralized, low-effort control. Our land cover map can be developed further to integrate invasion dynamics, inform fire risk and behavior models, optimize management actions, and guide territorial planning. Overall, it provides a valuable tool for targeted, scale-appropriate strategies to mitigate ecological and fire-related impacts of invasive pines.

1. Introduction

Biological invasions are among the most significant threats to biodiversity conservation worldwide, as they undermine ecosystem integrity and generate economic consequences [1]. Invasive species contributed to 60% of documented extinctions and were the sole driver of 16%. In 2019, the cost of invasions exceeded USD 423 billion, with 92% associated with impacts on ecosystem services and human well-being, and only 8% to management expenditures [2]. Although most countries include invasion targets in their biodiversity strategies, effective actions are often lacking, and sometimes economic development policies unintentionally promote invasions. Moreover, climate change is expected to exacerbate the invasive species risks, including their role in wildfires. To address these challenges, the management of biological invasions should integrate decision-support tools, preventive planning and regulatory measures, eradication, containment and control programs, and ecosystem-based management and restoration [2].

The spread of invasive species is closely tied to human activity, as explained by the GloNAF project, which showed that humans have reshaped plant global distribution, mainly by moving species from the Northern Hemisphere to other regions [3]. This is the case of Pinaceae species, introduced in many Southern Hemisphere countries for their economic value, but which have spread beyond plantation areas and became invasive, generating ecological, economic, and social impacts [4,5].

In northern Andean Patagonia, Argentina, forestry with Pinaceae species began in the 1950s, primarily in temperate forest regions, driven by government programs that offered fiscal and financial incentives to promote economic diversification and supply materials for cellulose and paper production [6]. In Río Negro province a total of 9681.5 ha were afforested between the years 1978 and 1990 [7]. Pinus ponderosa, P. contorta var. latifolia, and Pseudotsuga menziesii were the most frequently planted species [8]. The replacement of native forests has been banned since 1982 [9]. Many plantations, however, were abandoned, particularly after incentive payments for their maintenance and use were discontinued. These stands persist within native forest areas, acting as sources of invasion and degrading adjacent ecosystems [6]. Today, the widespread invasion of Pinaceae in northwestern Patagonia reflects inadequate management practices and the abandonment of early plantations [10].

Ecological, economic, and social impacts of pine invasion, and their link to plantations are currently under intense debate [11,12,13]. Plantations provide potential benefits such as employment, industrial support, and carbon sequestration [4,11], though the latter remains controversial [14,15]. However, they degrade ecosystem services by altering the hydrological balance and modifying litter and soil biota [16]. Moreover, plantations act as propagule sources, promoting pine invasions into surrounding ecosystems [5], which threaten biodiversity by outcompeting native plant species, reducing fauna richness, and altering ecosystem functioning, particularly fire regimes [17,18,19,20].

Invasive pines alter fuel properties and fire regimes by increasing biomass, enhancing vertical and horizontal fuel continuity, and exhibiting high flammability due to traits such as resin production, volatile compounds, and combustible litter [10,21]. Their influence varies among species, with serotinous taxa like Pinus radiata and some populations of P. contorta reinforcing invasion–fire feedbacks [22,23]. These processes are particularly concerning in wildland–urban interface (WUI) areas, where pine invasions are widespread and pose major risks by facilitating spot fires through firebrand production [24]. In the Andean–Patagonian region, WUI expanded by 76% between 1981 and 2016, concentrating 77% of recorded fires [25]. In recent decades, extreme fire events have become increasingly frequent in this region, particularly during summer seasons between 2012 and 2025, causing severe social and economic impacts [26]. In the Andean Patagonia alone, more than 800 houses and other infrastructure have been destroyed in the WUI, compromising not only the ecological functioning of ecosystems but also a wide range of ecosystem services, including agricultural, tourism, and other socio-economic activities [27,28]. Satellite-based measurements of radiative power from the most recent fire in the northwestern Patagonia (Epuyén town) in January 2025 revealed that the energy released per hectare in exotic conifer plantations was three to ten times higher than that released in areas dominated by native forest, shrublands, or rural and urban landscapes (pers. comm. Thomas Kitzberger). Understanding and mapping pine invasion spatial distribution in WUIs is therefore essential for identifying invasion hotspots and to prioritize sites for effective management strategies implementation, such as biomass removal to reduce flammability and overall fire risk [29].

In this context, remote sensing is an indispensable tool for land use and land cover (LULC) mapping, including invasive species detection. The ability to discriminate different land cover types relies on their differential response across the electromagnetic spectrum, the use of spectral indices, and metrics that capture temporal dynamics [30]. Since the launch of Sentinel-2, its 10 m spatial resolution and higher revisit frequency have substantially improved the accuracy of land cover classifications in multiple ecological contexts [31]. Nevertheless, detecting pine invasions remains a methodological challenge due to their strong spatial heterogeneity. Invasion fronts often appear as small, sparse individuals or low-density clusters that fall below the detection threshold of moderate-resolution sensors initially and exhibit spectral properties similar to surrounding shrublands or native forests as they form mature patches [32]. Sentinel-2 partially overcomes these constraints through its fine spatial resolution and high revisit frequency, which enable the derivation of phenological metrics that have been shown to improve land cover classification accuracy [31].

In this study, we aimed to assess the spatial extent of Pinaceae invasions in Bariloche WUI, the main demographic, economic, and touristic hub of northwestern Patagonia. Our specific objectives were: (1) to produce a map of Pinaceae invasions by combining existing plantation database with field surveys and remote sensing tools; (2) to quantify the invaded area and characterize its spatial distribution pattern in the main invaded ecosystems; and (3) to explore potential applications of the invasion map as a decision-support tool for management, fire prevention, and land use planning in the WUI. We expect that pine invasions in this region can be reliably mapped and quantified, thereby supporting the identification of priority areas for management and fire risk reduction.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area corresponds to the Andean portion of northern Patagonia, Argentina, around latitude 41° S. Physiographically, it includes lakes, glacial valleys, and mountain slopes covered mainly by forests dominated by Nothofagus species. Elevation ranges from 700 to 2400 m a.s.l. The climate is Mediterranean, with rainfall concentrated in autumn and winter [33]. Mean annual rainfall and temperature range from 1300 mm and 8 °C in the west [34] to 574 mm and 9 °C in the east (San Ramón Ranch, unpublished data). The region’s climate is influenced by the Andean barrier and the Pacific anticyclone [35]. The rain shadow effect of the Andes causes mean annual precipitation to decline sharply from approximately 3000 mm on the western slopes to less than 800 mm only 50 km eastward [36]. This, in turn, determines a west–east vegetation gradient with decreasing diversity, as forests are gradually replaced by the arid Patagonian steppe. Pine invasions (Pinus contorta, P. ponderosa, P. radiata, and Pseudotsuga menziesii; hereafter pines) occur in different environments along this precipitation gradient.

The study area covers 146,619.73 ha, including the municipal territories of Bariloche and Dina Huapi contiguous cities (40.93–41.39° S, 71.58–70.89° W). The area with pine plantations and related invasions comprises five different jurisdictions, including municipal lands of Bariloche and Dina Huapi, a sector of Nahuel Huapi National Park, and portions administered by Río Negro and Neuquén provinces. The limits of the study area were defined based on the WWF HydroSHEDS Basins Level 10, intersected with the municipal boundary of Bariloche. The area is bounded by basin divides to the north, east, and south, by the municipal boundary to the west, and by Lake Nahuel Huapi at its center.

Since the available plantation databases provide information only on the location and extent of plantations, an exhaustive search was conducted, allowing the establishment dates of some plantations to be determined. Jurisdictional boundaries (national, provincial, and municipal) and land tenure of pine-invaded areas were determined by integrating cadastral parcel maps from Río Negro and Neuquén provinces with spatial databases provided by the National Parks Administration [37,38].

2.2. Land Cover Model

To map the pine invasions, we performed a supervised classification of land use/land cover for the period 2023–2024 using Sentinel-2 satellite images and the Random Forest algorithm on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. The classification includes the following classes: pine plantation, pine invasion, barren land, native forest, rocky outcrop, shrubland, steppe, urban, water, and wetland. We obtained training samples for each class in order to train the supervised classification algorithm, which assigns each pixel in the Sentinel-2 images (10 m resolution) to a land use and land cover class. Most of the training samples were obtained through the interpretation of high- and medium-resolution satellite imagery (i.e., Google Earth historical imagery and Sentinel-2 scenes for winter, spring, summer, and autumn 2023–2024). In a limited number of cases, where the identification of specific land cover types was ambiguous, phenological signatures from the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Normalized Difference Fraction Index (NDFI) were used to support class attribution for the 2000–2024 period. Although the mapped period corresponds to 2023–2024, historical Google Earth images were frequently used because older scenes often provide superior detail, shadow definition, and viewing angles that enhance interpretability; moreover, they allow the reconstruction of invasion histories and the identification of early establishment stages. Phenological trajectories, particularly gradual increases in NDFI values were especially useful for confirming invasion processes and distinguishing them from native vegetation. Sample collection was carried out by a group of eight local specialists, with whom we conducted interpretation workshops to standardize criteria across classes. These criteria included patch shape and size, color and texture patterns, and the position of vegetation types along the west–east climatic gradient and local geomorphology. For the training dataset, polygons were manually digitized over large, homogeneous, and pure patches that exhibited a clear and unambiguous spectral signal of each class. Polygon size was defined to capture fine-scale heterogeneity within each homogeneous patch while avoiding excessive variation across classes; therefore, all polygons were kept below 40 Sentinel-2 pixels (≈0.4 ha) and were selected to be broadly comparable in size to prevent bias toward classes represented by larger patches. A minimum of 50 polygons were digitized for each land use and land cover class (excluding urban). The number of polygons per class were: pine plantation (70 interpreted and 25 from field surveys), pine invasion (62 not used in the training step), barren land (61), native forest (50 interpreted and 18 from field surveys), rocky outcrops (61), shrublands (50), steppe (50), water (56), and wetlands (80).

We generated the attribute space using quarterly composites of visible and infrared reflectance (6 bands), four spectral indices, annual metrics summarizing the temporal dynamics of the indices (functional attributes), a canopy height model [39] and three geomorphological attributes (height, slope, and aspect). We implemented cloud and cloud shadow masking by combining Sentinel-2 Surface Reflectance with the Sentinel-2 Cloud Probability dataset, following the s2cloudless approach [40,41]. Quarterly composites were constructed for summer, autumn, winter, and spring. Each composite considered the pixel with the median value of the frequency distribution from all good-quality observations within each period. Based on these quarterly composites, we calculated the following spectral indices: NDVI, Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI), Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR), and Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) [31,42].

The temporal dynamics of vegetation was characterized using functional attributes derived from these spectral indices. For each index, we calculated the mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation (4 metrics × 4 indices). We constructed a digital elevation model (DEM) including elevation, slope, and aspect using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) with a spatial resolution of 30 m available in GEE [43]. The attribute space was composed of 60 bands: reflectance from the six visible and infrared bands for the four seasons (6 × 4), the four spectral indices for the four seasons (4 × 4), the functional attributes for each spectral index calculated over the entire year (4 × 4), the canopy height model and the three geomorphological attributes derived from the DEM.

We sampled the attribute space using the training polygons to train the Random Forest algorithm [44], excluding the pine invasion samples. Thus, a series of complex decisions was generated in a multidimensional space, which were then applied to the study area, classifying all pixels into the defined classes. The key step in the classification was the separation of pine areas in invasions and plantations, which was achieved through the integration of external datasets. For this, the plantation database provided by the Andean Patagonian Forest Research and Extension Center [45] was used as a baseline, and pine plantations were further digitized manually from high-resolution imagery to complement and improve the existing information. The broader land cover classification included all classes, while the urban class was subsequently incorporated using the Open Buildings dataset available in GEE [46]. This hierarchical approach ensured a consistent mapping of both general land cover types and the specific distinction between pine invasions and plantations. After performing the supervised land cover classification, we determined the main vegetation contexts in which pine invasions occurred by overlaying the invasion map with the major vegetation units (forest, shrubland, and steppe) along the precipitation gradient of the study area.

To analyze invasion dynamics in greater detail, we selected a well-known invasion site in the Arroyo del Medio basin, where a dense Pinus contorta population has expanded from adjacent plantations over the past two decades. Using high-resolution historical imagery from Google Earth (2004–2025), we manually digitized the invaded areas for each available date and delineated the maximum invasion front. We then calculated the mean invasion rate (ha yr−11) by dividing the total invaded area by the 21-year period, and estimated the mean advance rate (m yr−11) by measuring the average distance between plantation boundaries and the farthest invasion front, thus obtaining the average annual expansion rate over the study period.

Validation of the classification was performed through the interpretation of randomly selected points stratified across the ten land cover classes [47]. For the classes pine plantation and pine invasion, 200 points were generated each, given their central importance to the study, while 100 points were assigned to each of the remaining classes. The random points were generated independently of the training dataset, using random stratified sampling within the mapped extent of each class using a preliminary version of the map. Randomization included a minimum distance constraint of 500 m between points of the same class to reduce spatial autocorrelation. Points were interpreted using high-resolution Google Earth imagery, including the available historical images on the platform to reconstruct invasion dynamics or vegetation changes while focusing on interpreting conditions for the 2023–2024 period. To ensure distribution among interpreters, the total pool of points was divided into eight subsets, each assigned to a distinct interpreter. For each point, the interpreter recorded the assigned class, whether it was located on a boundary, and their level of confidence applying the same interpretation criteria defined for the training sample collection. Points located on class boundaries or where the land cover class could not be reliably determined were excluded from the analysis. Given the difficulty of detecting pine invasions through satellite image interpretation, particularly in early or low-density stages where visual contrast with the surrounding vegetation is minimal, we also incorporated the 62 invasion polygons that had been excluded from the training dataset. Thus, we avoid the generation of evident commission errors patterns during model calibration while providing independent, well-characterized samples for validation. The final distribution of validation samples was as follows: pine plantation (147), pine invasion (132), native forest (95), water (51), steppe (142), rocky outcrop (42), urban (66), wetlands (74), shrubland (112), and barren land (49). This distribution reflects the fact that many initial samples were discarded during the validation process, and that the class distribution in the final map differed from the preliminary version used to stratify the original sample selection. Based on the interpreted points, confusion matrices were constructed and accuracy metrics were calculated, including overall accuracy, producer and user accuracy, and omission and commission errors. These assessments were performed at two conceptual levels of resolution: one considering the ten original classes and another with three aggregated classes (pine plantation, pine invasion, and non-pine class).

We conducted 84 field surveys of pine plantations and invasions, and native vegetation across our study area to better understand the spatial patterns of invasion and to refine the discrimination of land cover types that were difficult to interpret using satellite imagery. Based on a preliminary version of the map, we identified and visited areas where confusion among classes was most likely, such as transitional zones, shaded slopes, and mixed covers, in order to improve the training dataset for the classification algorithm. Using the ODK Collect [48] mobile application loaded with preliminary versions of the map and a predefined survey form developed in KoboToolbox [49], we conducted field assessments with a smartphone. At sites where the preliminary map showed inconsistencies, we recorded the geographic location, interpreted the land cover type, and collected photographic evidence. When necessary, we also digitized polygons directly in the field using the preliminary map and the high-resolution imagery available within the application. All information, exported as a shapefile, was subsequently processed and incorporated as training samples for the classification.

3. Results

Between 1978 and 1990, a total of 9681.5 ha were planted in the province of Río Negro and 17,951 ha in the province of Neuquén. Within the study area, the earliest pine plantations date back to 1927, when Pinus radiata and P. sylvestris were established on the San Pedro Peninsula. Most plantations, however, were established between 1960 and 1990. Plantation size varied widely across sites, from small-scale plots of about 3.5 ha on the San Pedro Peninsula to extensive plantations covering up to 2324 ha on Arroyo del Medio basin. The main species planted were Pinus ponderosa, P. contorta, P. radiata, P. sylvestris, and Pseudotsuga menziesii, often mixed within the same property (Table 1).

Table 1.

Establishment date, area (ha), and dominant pine species of plantations in different sectors of the study area.

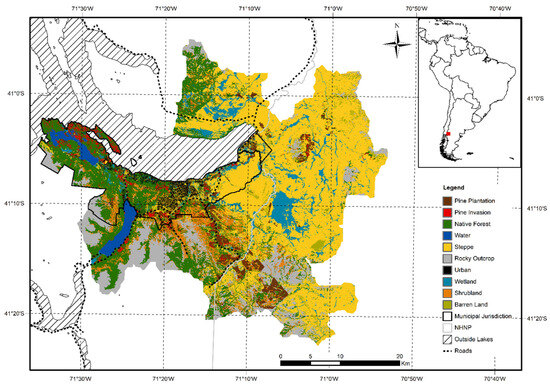

Actually, pine dominated areas occupied 6,886 ha in total, representing 4.7% of the study area, of which 4013 ha (2.7%) corresponded to plantations and 2873 ha (2.0%) to pine invasion. Pine invasion thus accounted for 41.7% of the total surface covered by pines and occurred across the main ecosystems along the regional environmental gradient, including steppe (64,205 ha, 43.8%), native forests (29,019 ha, 19.8%), and shrublands (10,000 ha, 6.8%), which together constitute the dominant natural matrix of the study area (Table 2). Although pine plantations were primarily established in the eastern sector, in transitional zones between steppe and shrubland, pine invasions were concentrated in the west, within native forests, and in all cases were associated with plantations acting as propagule sources (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Area occupied by each land cover class.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the land cover classes in the study area nearby Bariloche city. The sub-panel shows, within a map inset of South America, the location of the study area (red square) in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina.

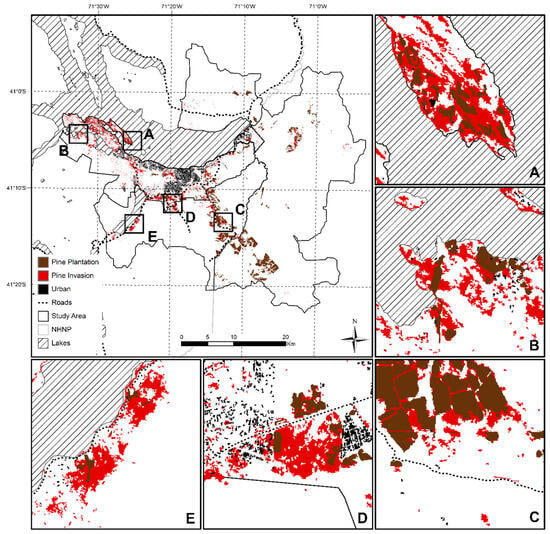

We identified five major invasion foci: the San Pedro Península and Circuito Chico in the west; Gutierrez lake and Ventana mountain in the southwest; and Arroyo del Medio basin in the southeast (Figure 2). The majority of invasion patches were located in forest, shrubland, and steppe ecosystems, while only a small fraction occurred in wetlands. Forests accounted for 1740.84 ha invaded by pines (61.2% of total invaded area), steppes for 721.5 ha (25.4%), and shrublands for 381.5 ha (13.4%). Plantations exhibited regular, continuous, and compact spatial patterns, often characterized by straight borders and right angles, whereas invasions displayed heterogeneous and irregular shapes, fragmented into patches. Invasion patches showed a wide variation in sizes, with 65.4% of the invaded area distributed across 367 patches larger than 1 ha, of which the largest 37 (>10 ha) represented 33.8% of the total invaded area. The remaining 34.5% of the total invaded area was spread across 7558 smaller patches.

Figure 2.

Coverage of pine plantation and pine invasion in the study area. Details for different subareas: (A) Península San Pedro, (B) Circuito Chico, (C) the Arroyo del Medio basin, (D) Ventana mountain, and (E) the area around Gutierrez lake.

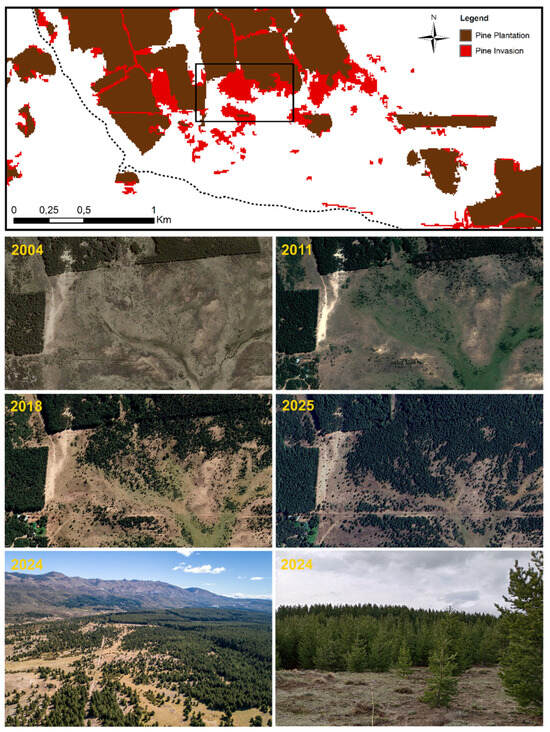

A representative example of the spatiotemporal dynamics of P. contorta invasion is shown in the Arroyo del Medio basin, where expansion from a plantation into the surrounding steppe was documented over two decades (Figure 3). The sequence of high-resolution images (2004–2025) reveals a progressive and continuous spread of invasive individuals that gradually coalesced into dense patches, advancing at an estimated average rate of 0.43 ha/yr and 14.6 m/yr along the invasion front. The pattern illustrates the transition from isolated trees to closed stands, a process favored by open steppe conditions and the proximity to mature plantations that act as persistent sources of propagules. The 2024 drone and field images illustrate, in greater detail, the establishment of dense regeneration beyond the original plantation boundary, highlighting the ongoing spread and maturation of invasion fronts across the steppe.

Figure 3.

Google Earth image sequence spanning 21 years from 2004 to 2025, illustrating the progressive spread of the invasive Pinus contorta in Arroyo del Medio basin. The last two images (2024) were captured by a drone and field survey, respectively. The last two images (2024) were acquired using a drone (DJI Phantom 4 Pro, equipped with a 1-inch 20MP CMOS sensor, a 24 mm lens with an f/2.8–f/11 aperture, and a mechanical shutter) and through field survey, respectively.

Pine invaded areas were distributed across four jurisdictions: municipal land of Bariloche (2066.4 ha, 71.8% of total invaded area), municipal land of Dina Huapi (27.7 ha, 1%), a sector of Nahuel Huapi National Park (621.8 ha, 21.6%), and a portion of Río Negro province (162.2 ha, 5.6%). The total area invaded by pines was mostly distributed across privately owned lands (2560 ha, 89.1%), while only nearly 10% (313.2 ha) was located in state lands. Pine-invaded areas on private lands were distributed across a range of cadastral unit sizes, spanning properties of less than 1 ha to those over 1000 ha (Table 3). Small parcels (<1 ha) represented 13.5% (345.6 ha) of the invaded area on private lands, whereas the 339 larger ones (>10 ha) accounted for nearly 70% (1756.9 ha) of the total invaded area on private lands.

Table 3.

Subdivision of pine invaded private lands by parcel size and cadastral units.

The Random Forest showed that geomorphological attributes were the strongest predictors in the model. Elevation was the most influential variable (importance = 50.12), followed by slope (36.93) and aspect (29.55), indicating that the environmental gradients associated with topography constituted key variables for discriminating among the different classes. Sentinel-2 spectral features also contributed substantially to model performance. Dry-season SWIR1 (B11v = 28.38), autumn SWIR1 (B11o = 24.43) and spring SWIR2 (B12p = 24.36) were among the highest-ranked predictors, together with winter NDMI (23.99), canopy height (23.96), and autumn NBR (21.31).

Validation considering the ten land cover classes achieved an overall accuracy of 0.75. The best-performing classes were water (producer’s accuracy = 0.98; user’s accuracy = 1.00), urban (0.88 and 0.98, respectively), and pine plantations (0.89 and 0.81). In contrast, natural classes such as shrubland (0.55 and 0.93), forest (0.86 and 0.52), and steppe (0.67 and 0.84) exhibited higher omission and commission errors (Table S1). When the land cover types were aggregated into three major classes (pine plantation, pine invasion, and non-pine class) the overall accuracy increased to 0.90.

Table 4a shows the confusion matrix. The plantation class showed a producer’s accuracy of 0.89 and a user’s accuracy of 0.81, with an omission error of 11%. The invasion class performed less well, with a user’s accuracy of 0.77 and a producer’s accuracy of 0.53, with most of the confusions between native forest and pine plantations reflecting a 47% underestimation of invaded areas. Finally, the non-pine class exhibited the highest values (0.97 and 0.93), with very low omission and commission errors (3% and 7%, respectively) (Table 4b).

Table 4.

Results from the validation analysis considering 3 land cover classes. (a) Confusion matrix considering three major classes: pine plantations, pine invasions, and the non-pine class. (b) Model producer error, omission error, user accuracy, and commission error for the validation considering three major classes: pine plantations, pine invasions, and the non-pine class.

4. Discussion

According to our findings, pine invasion originating from plantations was mapped and quantified, consistent with results from similar remote-sensing studies worldwide [55,56]. Our study area is representative of a broader region encompassing parts of the central Andean Patagonia [12], where pine plantations have been widely established (Neuquén province: 3,342,622 ha; Río Negro province: 1,157,783 ha; Chubut province: 2,100,788 ha) [45]. Most processes observed in our study area, such as land parcels, urban growth, and wildland–urban interface expansion, mirror patterns occurring in many other Patagonian and Andean towns. Thus, we propose our study area as a model system, and the tool developed here is likely applicable to other regions as well.

Pine invasions represent about half of the total study area occupied by pines, which underscores the magnitude of unregulated spread beyond plantation boundaries. This finding highlights the central role of plantations as sources of propagules, from which invasions originate and expand into native ecosystems [5]. Many plantations, particularly those established in the western sector of the study area, are several decades old and date back to the city’s early development in the 20th century [53], acting as persistent sources of propagules. In this context, distinguishing between plantations and invasions in the mapping is fundamental for allowing the identification of priority areas for biomass management and fire risk reduction.

The literature indicates that pine invasion patterns in Patagonia are strongly influenced by precipitation gradients and vegetation types, with grasslands and shrublands typically being more susceptible than forests [4,5,57,58]. In contrast, our map shows that over 60% of the invasions detected in the study area occur within native forest. Although our data do not allow us to assess underlying mechanisms, previous studies suggest that wetter temperate forests may provide favorable growing conditions for pines, and that past disturbances such as clearing or fire may facilitate establishment during forest regeneration. As a result, forests show large invasion patches, while in shrublands and steppes invasions are distributed more often in numerous small and scattered patches, consistent with propagule dispersal and the initial establishment of isolated individuals [59]. The coexistence of large consolidated foci and thousands of smaller patches reveals a hierarchical pattern of expansion, in which a few historical nuclei function as epicenters of spread, while a constellation of satellite patches signals the continuity of the invasion process. These cases illustrate not only the magnitude of invasion in the most well-known sites but also the ability of pines to expand under contrasting environmental and land use contexts.

The detection of pine plantations and invasions using Sentinel-2 imagery proved useful, although it posed significant methodological challenges. Unlike conventional land cover classifications, which are usually based on physiognomic types such as forest, shrubland, or steppe [60], this study required the identification of a specific taxonomic group—pines—which is more difficult to capture spectrally. Pine invasions are highly heterogeneous in density and age structure [56,61]. In advanced stages, their spectral signatures increasingly overlap with those of native forests, as both vegetation structure and functioning become similar. In contrast, in shrubland and steppe environments, the spatial resolution of Sentinel-2 enables the detection of large and dense stands, whereas isolated individuals or early invasion fronts remain below the detection threshold and are often confused with surrounding vegetation. This challenge becomes even more pronounced when attempting to spectrally distinguish pine invasions from plantations.

For the training of the pine detection step, we relied exclusively on plantation samples, as these provided a cleaner spectral signal. Including invasion samples during training led to a strong overestimation of invaded areas, since many pixels represented heterogeneous conditions, whose spectral signatures resembled shrublands or steppes rather than pine invasions. After generating the general pine layer, we tested a second classification using both samples to distinguish plantations from invasions, but this approach misclassified many plantation areas as invasions. Consequently, we adopted a plantation database as the baseline to separate the two categories. Although useful, the 2017 layer is not exempt from problems, as many plantations in the western sector of the study area were likely unmapped due to their mixture with native vegetation since this layer was created by manual digitization combining Landsat imagery (30 m resolution) with Spot 5 data (10 m resolution). Therefore, we conducted a detailed review and update based on the interpretation of high resolution google earth imagery, including historical scenes, and manually digitized previously unmapped plantations. Another limitation is that, in some cases, very old and dense invasions were classified as plantations, reflecting the difficulty of distinguishing between these classes, particularly since some invasions in the region had already been developing for more than 50 years when the dataset was produced [4].

These limitations are consistent with the accuracy results obtained in our validation. The high omission error observed for the invasion class reflects the under-detection of scattered trees, while commission errors result from the misclassification of native vegetation with similar spectral properties. Both error types tend to compensate for each other in terms of detected area, leading to an overall underestimation of invasions of around 25%, which is consistent with the difficulty of detecting early stages of invasion [62]. Furthermore, the validation dataset itself is imperfect, as visual interpretation does not always allow an accurate distinction of invasions due to the heterogeneity of situations. Despite these limitations, the resulting map provides a robust representation of the general distribution of pines, highlights areas under active invasion pressure, and constitutes a valuable tool to guide detailed field and drone surveys to support the planning of management actions.

Pine invasion in the study area spans multiple jurisdictions with overlapping land tenures. Over 70% of the invaded area lies within the neighboring municipal lands of Bariloche and Dina Huapi, mostly low-impact areas with native vegetation, having direct implications for fire risk management. Nevertheless, the WUI is not officially defined in this area, by comparing different methodologies, we can state that a large portion of the invasions are located within the interface zone [63]. Another substantial fraction of the invasion occurs within Nahuel Huapi National Park, spanning both Río Negro and Neuquén provinces, where private lands coexist with lands under federal jurisdiction. This overlap of jurisdictions poses significant challenges for the planning and coordination of management actions, which must balance conservation goals with forestry production demands and population safety. The situation is further complicated by the lack of legislation regulating the monitoring, enforcement, and management of propagule dispersal from plantations. Although the first National Law No. 21695 (1977) did not provide economic support for thinning and pruning activities, the subsequent National Law No. 25080 (1998), introduced tax incentives and regulations to promote these practices within the forestry sector [9]. However, many plantation owners did not implement such management actions, and in the absence of an authority to oversee their enforcement, much of the current invasion originates from the lack of application of these silvicultural practices. The diversity of contexts, including residential, productive, and conservation areas, requires tailored strategies. In WUI zones, early detection and control are essential to reduce risks, whereas in productive and public lands, plantation management must be balanced with the prevention of new invasions.

Our results on the distribution of invaded areas across different types of land ownership and sizes of land properties can be used to build engagement strategies with land owners or managers towards the goal of control these pine invasions. Private lands accounted for nearly 90% of the invaded area, making it essential to build communication channels with land owners and agree on possible solutions to this growing problem [64]. On one hand, 13.5% of the invaded area on private lands is distributed across many (more than 45,000) small land properties (less than 1 ha). In these cases, the solution is highly decentralized and potentially simpler, since the removal of just a few trees per property (e.g., between one and ten individuals per household) could substantially reduce the overall invasion. Although such actions may represent a considerable effort at the household level, small-scale interventions distributed among many actors could collectively yield an effective regional outcome. One possible strategy to remove these invasive pines would be to engage with this population of land owners through education and outreach channels so that everyone becomes aware of the negative impacts produced by invasive pines (for example, the increased risk of fires across the WUI, which directly affects land owners). On the other hand, nearly 70% of the invaded area on private land is distributed across relatively few (less than 350) big land properties (over 10 ha). Due to the potentially large cost of removing invasive pines across these large areas, big land owners would require some kind of economic incentive to take any action. To engage with them and agree on possible management strategies it would be crucial that the state offers them financial incentives, such as those given to land owners since the 1980s to promote forestry in this region. Implementing an incentive scheme proportional to the area affected on each property would help motivate landowners to actively participate in control efforts.

WUIs are inherently fire-prone [63], with the Bariloche WUIs exemplifying this elevated fire hazard [21,30]. Our results indicate that pine invasions are predominantly concentrated within these WUIs, highlighting the social dimension of the problem, as pines can increase fire risk through the alteration of plant fuel [65,66] and the release of firebrands capable of igniting spot fires [24,67]. Incorporating detailed invasion maps into management strategies is therefore essential for reducing fire risk in a city where WUI areas are experiencing rapid expansion [68]. Such maps enable evidence-based directives that integrate urban development, conservation goals, and fire mitigation efforts, providing a strategic framework to address both ecological and social risks.

5. Conclusions

We produced a map which provides a representation of the general distribution of pine plantation and invasion in the WUI of Bariloche, a representative sector of central Andean Patagonia. By integrating existing plantation database with field surveys and remote sensing, we were able to quantify the current extent and distribution of pine invasions with a level of detail not previously available for the region. The mapped patterns show marked heterogeneity in pine invasions among jurisdictions and land use contexts, underscoring the influence of local environmental and management conditions on invasion.

The map highlights areas under active invasion pressure, and constitutes a valuable tool to guide and support the planning of management actions. It could inform and support legislation aimed at regulating the use of invasive species, particularly in WUI areas. Specific measures, such as restricting the sale of ornamental pine species or implementing urgent regulations to curb propagule dispersal from plantations and encourage landowner monitoring, are recommendations derived from the observed risks and distribution. Aligning economic incentives with ecological restoration is also relevant, emphasizing the need to promote value chains, local processing, and market diversification to offset the management costs associated with removing less-valued pine species.

This mapping in a base platform requiring expansion and refinement to maximize its utility. Future work should focus on integrating ecological data and models that were not developed in this study, such as integrating ecological niche models to allow projections of invasion potential under current and future climate and disturbance scenarios, combining spatial data with invasion dynamics to build WUI fire risk maps and fire behavior models, and supporting territorial planning processes by optimizing management actions and providing a strategic framework to reduce ecological and social risks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121853/s1. Table S1: Results from the validation analysis considering 10 land cover classes. (a) Confusion matrix (b) Model producer’s error, omission error, user’s accuracy and commission error for the validation considering 10 land cover classes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; Methodology, C.E.B. and J.M.; Formal analysis, C.E.B.; Investigation, all authors; Writing—original draft, all authors; Review and editing, S.L.G. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the framework of the project PICT-2021-I-A-00079 (Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the governance network Red Pinos, particularly Pedro Laterra. We also express our appreciation to Santiago Quiroga for his valuable contribution to the interpretation of areas affected by pine invasion and native vegetation within the study area.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Murphy, G.E.P.; Romanuk, T.N. A meta-analysis of declines in local species richness from human disturbances. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and Their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Roy, H.E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P., Renard Truong, T., Bacher, S., Galil, B.S., Hulme, P.E., Ikeda, T., Sankaran, K.V., McGeoch, M.A., et al., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2023.

- Van Kleunen, M.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Pergl, J.; Winter, M.; Weber, E.; Kreft, H.; Weigelt, P.; Kartesz, J.; Nishino, M.; et al. Global exchange and accumulation of non-native plants. Nature 2015, 525, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Nuñez, M.A.; Ledgard, N.J.; Pauchard, A.; Richardson, D.M.; Sarasola, M.; Van Wilgen, B.W.; Zalba, S.M.; Zenni, R.D.; Bustamante, R.; et al. Spread and impact of introduced conifers in South America: Lessons from other southern hemisphere regions. Austral Ecol. 2010, 35, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, M.A.; Chiuffo, M.C.; Torres, A.; Paul, T.; Dimarco, R.D.; Raal, P.; Policelli, N.; Moyano, J.; García, R.A.; van Wilgen, B.W.; et al. Ecology and management of invasive Pinaceae around the world: Progress and challenges. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3099–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, J.O.; Loguercio, G.A.; Salvador, G. Razones para forestar en Patagonia. Foro ecología y sociedad: ¿Por qué plantar en Patagonia? Estado actual y el rol futuro de los bosques plantados. Ecol. Austral 2015, 25, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchio, O. Los bosques de cultivo en Patagonia 1978–1999. Patagon. For. 2015, 2, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter, T.; Laclau, P. Ecotono–bosque y plantaciones forestales en Patagonia norte. Ecol. Austral 1998, 8, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Congress of Argentine Nation 2007. Available online: https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/55000-59999/55596/texact.htm (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Franzese, J.; Raffaele, E.; Chiuffo, M.C.; Blackhall, M. The legacy of pine introduction threatens the fuel traits of Patagonian native forests. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 267, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defossé, G. ¿Conviene seguir fomentando las plantaciones forestales en el norte de la Patagonia? Ecol. Austral 2015, 25, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruelo, J. ¿Conviene seguir fomentando las plantaciones forestales en el norte de la Patagonia Argentina? ¿Dónde? ¿Para qué? ¿A quién le conviene? Ecol. Austral 2015, 25, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, E.; Núñez, M.; Relva, M. Plantaciones de coníferas exóticas en Patagonia: Los riesgos de plantar sin un manejo adecuado. Ecol. Austral 2015, 25, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, M.A.; Davis, K.T.; Dimarco, R.D.; Peltzer, D.A.; Paritsis, J.; Maxwell, B.D.; Pauchard, A. Should tree invasions be used in treeless ecosystems to mitigate climate change? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, J.; Dimarco, R.D.; Paritsis, J.; Peterson, T.; Peltzer, D.A.; Crawford, K.M.; McCary, M.A.; Davis, K.T.; Pauchard, A.; Nuñez, M.A. Unintended consequences of planting native and non-native trees in treeless ecosystems to mitigate climate change. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 2480–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.A.; Tarabini, M.M.; Buduba, C.G.; Von Müller, A.R.; La Manna, L.A. Balance hídrico en plantaciones de Pinus radiata en el NO de la Patagonia argentina. Ecol. Austral 2019, 29, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasevic, J.A.; Estades, C.F. Effects of the structure of pine plantations on their “softness” as barriers for ground-dwelling forest birds in south-central Chile. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paritsis, J.; Aizen, M.A. Effects of exotic conifer plantations on the biodiversity of understory plants, epigeal beetles and birds in Nothofagus dombeyi forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, P.; Villaseñor, N.; Uribe, S.; Estades, C.F. Local and landscape determinants of small mammal abundance in industrial pine plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, J.; Zamora-Nasca, L.B.; Caplat, P.; García-Díaz, P.; Langdon, B.; Lambin, X.; Montti, L.; Pauchard, A.; Nuñez, M.A. Predicting the impact of invasive trees from different measures of abundance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, L.; Beletzky, N.A.; de Torres Curth, M.I.; Oddi, F.J. From leaves to landscape: A multiscale approach to assess fire hazard in wildland-urban interface areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzese, J.; Raffaele, E. Fire as a driver of pine invasions in the Southern Hemisphere: A review. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.T.; Maxwell, B.D.; McWethy, D.B.; Pauchard, A.; Nuñez, M.A.; Whitlock, C. Pinus contorta invasions increase wildfire fuel loads and may create a positive feedback with fire. Ecology 2017, 98, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.; Porto, L.; Viegas, D. Characterisation of firebrands released from different burning tree species. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 7, 651135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, M.M.; Martinuzzi, S.; Kramer, H.A.; Defossé, G.E.; Argañaraz, J.; Radeloff, V.C. Rapid WUI growth in a natural amenity-rich region in central-western Patagonia, Argentina. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2019, 28, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, M.A.O.; Victoriano, S.A.; Mariezcurrena, M. Incendios en la Patagonia: La vuelta a la asistencia presencial en PAE luego de un año de pandemia y virtualidad. Cuad. Crisis 2022, 21, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo, A.; Fernandez, M.T.; Pons, D.H.; Claps, L.; Chillo, M.V.; Sarasola, M.M. Informe Inicial: Evaluación de Daños por Incendio Confluencia: Zonas Forestales, Agrícolas y de Interfaz Río Negro; Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2025; 26p.

- Defossé, G.E. Fuegos de vegetación: Evolución de un fenómeno socio-ecológico global y su impacto en la interfase urbano-rural (iur) de la Patagonia Andina de Argentina. Cienc. Inv. 2021, 71, 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Trueman, M.; Standish, R.J.; Orellana, D.; Cabrera, W. Mapping the extent and spread of multiple plant invasions can help prioritise management in Galapagos National Park. NeoBiota 2014, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J. Principles of Remote Sensing; Longman: London, UK, 1985; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri, D.; Simwanda, M.; Salekin, S.; Nyirenda, V.R.; Murayama, Y.; Ranagalage, M. Sentinel-2 data for land cover/use mapping: A review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, W.; Brabyn, L.; Serrao-Neumann, S. Monitoring invasive pines using remote sensing: A case study from Sri Lanka. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provincial Water Department. Resumen Meteorológico 1999–2005, Estación San Carlos de Bariloche, Río Negro; Provincial Water Department: Bariloche, Argentina, 2011; 4p. [Google Scholar]

- Paruelo, J.M.; Beltrán, A.; Jobbágy, E.; Sala, O.E.; Golluscio, R.A. The climate of Patagonia: General patterns and controls on biotic processes. Ecol. Austral 1998, 8, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, A. Deserts and Semi-Deserts of Patagonia. In Ecosystems of the World; Goodall, D.W., Ed.; Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Río Negro Land Registry Agency. Available online: https://mapasagencia.rionegro.gov.ar/portal/home/item.html?id=6cf2b698ac584d65a409c1719b833d2c (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- National Park Administration. Plan de Gestión del Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi; National Park Administration: Bariloche, Argentina, 2019. Available online: https://nahuelhuapi.gov.ar/plan-de-gestion/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Lang, N.; Jetz, W.; Schindler, K.; Wegner, J.D. A high-resolution canopy height model of the Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupanc, A. Improving Cloud Detection with Machine Learning. 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/sentinel-hub/improving-cloud-detection-with-machine-learning-c09dc5d7cf13 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Skakun, S.; Wevers, J.; Brockmann, C.; Doxani, G.; Aleksandrov, M.; Batič, M.; Frantz, D.; Gascon, F.; Gómez-Chova, L.; Hagolle, O.; et al. Cloud Mask Intercomparison eXercise (CMIX): An evaluation of cloud masking algorithms for Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 274, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco Salinero, E. Teledetección Ambiental: La Observación de la Tierra Desde el Espacio; Grupo Planeta: Madrid, Spain, 2008; p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Alsdorf, D. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agroindustry. Inventario Nacional de Plantaciones Forestales. Región Patagonia–Inventario de Plantaciones Forestales en Secano. Ministerio de Agroindustria. 2017. Available online: https://www.magyp.gob.ar/desarrollo-foresto-industrial/pdf/Inventario_Patagonia_Andina.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sirko, W.; Brempong, E.A.; Marcos, J.T.C.; Annkah, A.; Korme, A.; Hassen, M.A.; Sapkota, K.; Shekel, T.; Diack, A.; Nevo, S.; et al. High-Resolution Building and Road Detection from Sentinel-2. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loola Bokonda, P.; Ouazzani-Touhami, K.; Souissi, N. Mobile data collection using open data kit. In Proceedings of the International Conference Europe Middle East & North Africa Information Systems and Technologies to Support Learning, Marrakech, Morocco, 21–23 November 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay, D.; Roy, R.; Roy, K. From Pen to Pixel: Exploring Kobo Toolbox as a modern approach to smart data collection. Food Sci. Rep. 2024, 5, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Diez, J.; Varela, S.; Martínez Meier, A.; Caballé, G.; Claps, L.; Andreassi, L.; Salvaré, F. Aprovechando residuos forestales: Una alternativa de manejo integral de plantaciones de Pinus ponderosa en la cuenca de Arroyo del Medio. Presencia 2017, 68, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, F. Inventario Forestal Forestación “Estancia Fortín Chacabuco”; Fortìn Chacabuco: Bariloche, Argentina, 2016; 13p. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfeld, J.; Murgic, I.; Christie, M. Caracterización de Áreas Críticas y de Conservación del Cerro Otto: Bases Para el Ordenamiento Territorial; CIEFAP: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Paritsis, J. Efectos de las Plantaciones de Coníferas Exóticas Sobre el Ensamble de Plantas Vasculares, Coleópteros Epígeos y Aves del Bosque de Nothofagus dombeyi. Bachelor’s Thesis, National University of Comahue, Bariloche, Argentina, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Defossé, G.; Dentoni, M.C. Estudio de Grandes Incendios: El Caso de la Estancia San Ramón, en Bariloche-Río Negro, Argentina; GTZ: Eschborn, Geramny, 1999; 92p. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, M.E.; Morton, D.C.; Cook, B.D.; Masek, J.; Zhao, F.; Nelson, R.F.; Huang, C. Mapping pine plantations in the southeastern U.S. using structural, spectral, and temporal remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, M.A.; Paritsis, J. How are monospecific stands of invasive trees formed? Spatio-temporal evidence from Douglas fir invasions. AoB Plants 2018, 10, ply041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; Liebhold, A.M.; Guo, Q.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Jo, I.; Ordonez, K.; Fei, S. Biotic resistance to exotic invasions: Its role in forest ecosystems, confounding artifacts, and future directions. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3287–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M.; Williams, P.A.; Hobbs, R.J. Pine invasions in the Southern Hemisphere: Determinants of spread and invasibility. J. Biogeogr. 1994, 21, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, B.; Pauchard, A.; Aguayo, M. Pinus contorta invasion in the Chilean Patagonia: Local patterns in a global context. Biol. Invasions 2010, 12, 3961–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagne, A.; Le Bris, A.; Monkam, D.; Mallet, C. Classification of vegetation classes by using time series of Sentinel-2 images for large scale mapping in Cameroon. In Proceedings of the XXIVth ISPRS Congress, Nice, France, 6–11 June 2022; pp. 673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, T.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Nuñez, M.A.; Ferrero, M.E.; Baldi, G.; Teste, F.P. Stealth invasions on the rise: Rapid long-distance establishment of exotic pines in mountain grasslands of Argentina. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 2989–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimun, S.R.; Rahman, M.M. A comprehensive review of tree cover mapping using satellite sensor data. Discov. Geosci. 2025, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Ghermandi, L. How to define the wildland–urban interface? Methods and limitations: Towards a unified protocol. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1284631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díaz, P.; Montti, L.; Powell, P.A.; Phimister, E.; Pizarro, J.C.; Fasola, L.; Langdon, B.; Pauchard, A.; Raffo, E.; Bastías, J.; et al. Identifying priorities, targets, and actions for the long-term social and ecological management of invasive non-native species. Environ. Manag. 2022, 69, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paritsis, J.; Landesmann, J.; Kitzberger, T.; Tiribelli, F.; Sasal, Y.; Quintero, C.; Dimarco, R.D.; Barrios-García, M.N.; Iglesias, A.L.; Diez, J.P.; et al. Pine plantations and invasion alter fuel structure and potential fire behavior in a Patagonian forest-steppe ecotone. Forests 2018, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, R.; Blackhall, M.; Franzese, J.; Bogino, S.; Cendoya, A. Changes in the distribution and availability of plant fuel associated with the invasion of non-native Pinus halepensis in high-altitude grasslands of Argentina. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 229, 105356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Bakar, B.H.A.; Mamat, H.; Gong, L.; Nursyamsi, N. A laboratory-scale study of selected Chinese typical flammable wildland timbers ignition formation mechanism. Fire 2023, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Clavé, S. La urbanización turística. De la conquista del viaje a la reestructuración de la ciudad turística. Doc. Anàl. Geogr. 1998, 32, 17–43. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).