Abstract

Threats to forest ecosystems from pest insects are supposed to become more severe due to climate change. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of forest pest insects and the mechanisms of their outbreaks is going to be of even greater importance. To understand these phenomena and cope with the consequences, the question of which patterns show meta-populations of pest insects before and after outbreaks is of high interest. Therefore, long-term studies have been carried out in two research areas in North-West Poland with the aim of studying the fluctuations of meta-populations of the Nun moth (Lymantria monacha L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) using pheromone traps. Synchronization of the fluctuations at the individual study plots was tested for correlations with the numbers of the Nun moth per trap, changes in the numbers of the Nun moth per trap, and the growth factors. The studied Nun moth meta-populations showed a certain pattern in fluctuations of their sub-populations (interaction groups) with phases of asynchronous and synchronous fluctuations; the latter seem to be important when it comes to distinctive peaks in Nun moth numbers in the meta-populations. We conclude that predicting population dynamics of the Nun moth demands long-term studies, including research on both density-dependent factors and stochastic processes.

1. Introduction

Amongst other factors, pest insects represent a significant threat to forest ecosystems. These problems are supposed to become more severe as a result of climate change. For the US Southwest, Canada, and Alaska, for example, unusually hot and dry weather patterns have been reported to cause increased outbreaks of pests [1]. Similar trends have been observed in Europe, where warmer winters and longer vegetation seasons promote the survival and reproduction of defoliating insects [2,3]. Thus, understanding the dynamics of forest pest insects and the mechanisms of their outbreaks is inevitably going to be increasingly important. Healthy forests are of great importance for sustainable development and directly or indirectly affect many of the UN Sustainability Goals [4], for instance, goal 13 (climate action) and especially goal 15 (life on land) [5].

One essential aspect regarding insect population dynamics is metapopulations and the synchronization of their sub-populations. Meta-populations are described by Hanski and Gilpin [6] as systems of local populations connected by dispersing individuals. As a local population, they understand the scale at which individuals interact with each other during their routine daily activities. Den Boer [7,8] describes populations as interaction groups on more or less isolated sites, but when the dimensions of the site greatly exceed the distances covered by the individuals, a continuum of interaction groups, being parts of a composite population (meta-population), exists. Comprehending such systems is of high importance when it comes to developing conservation strategies for animal populations [9] but also with respect to management strategies of pest insects. For example, Alrashedi et al. [10], who considered the management of meta-populations across patchy landscapes, concluded that control actions have to be local to each patch but also coordinated between patches. Some studies indicate that dispersal among populations plays a crucial role referring to their synchronizations [11,12].

Accordingly, to fathom the phenomenon of pest insect outbreaks and cope with the consequences, the question, which patterns show meta-populations of pest insects before and after outbreaks is of high interest. However, since this demands long-term research, such patterns are rarely studied and not much is known. In order to deepen our understanding of forest pest population dynamics, long-term studies have been carried out in research areas in North-West Poland with the aim of studying the fluctuations of meta-populations of selected forest pest insects, among them the Nun moth (Lymantria monacha L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) [13]. Two large research areas were studied with numerous study plots set up in them. Each research area can be perceived as a meta-population, and the study plots constitute local populations or sub-populations (interaction groups).

The Nun moth is one of the basic pests of pine trees in Poland and other parts of Europe. Male individuals have a body length of 35–45 mm, whereas the somewhat bigger females reach 45–65 mm. Most individuals of the species have characteristic black and white markings on the forewings, but individuals with a predominantly dark, even black, coloration also occur [14]. According to Bejer [15], larvae of this species hatch at the beginning of May and adults generally emerge from mid-July. Egg laying begins immediately after mating, around the end of July. The caterpillar develops within the eggshell until autumn and goes through several dormant phases (partly diapause) until the following spring. It easily survives low winter temperatures [14]. However, it has been shown that temperature has an impact on larval development [16]. In Poland, serious outbreaks have been reported, for example, for the period 1978–1984 [17]. Other studies [18,19] demonstrated a northward expansion of this species, which corresponds with changes in weather in Finland.

During our long-term studies, it was possible to follow the fluctuations of the Nun moth on individual study plots and over the whole research area. In both research areas, we observed situations of peaks in the numbers of this insect as well as abrupt declines. In the present paper we aim to: (1) describe the population dynamics of the Nun moth in the research areas (meta-populations) and look for similarities in the observed patterns; (2) analyze synchronization patterns in numbers of the Nun moths between study plots in the research areas; (3) study the impact of selected climatic factors on the population dynamics; (4) draw conclusions regarding predicting population dynamics of the Nun moth.

By analyzing the long-term data and discussing the mechanisms behind the population dynamics, we think that our study will be of very high value for understanding of meta-populations of the Nun moth in particular and pest insects in general.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Areas

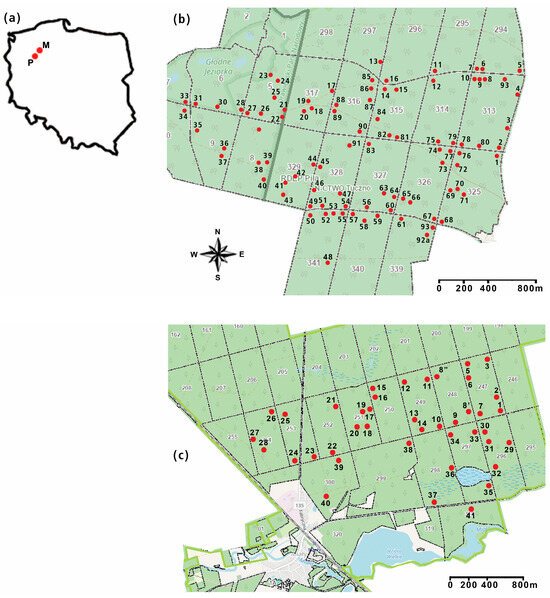

The studies were carried out in two research areas, named Martew and Potrzebowice (Figure 1). The areas are 40 km apart.

Figure 1.

Research areas Martew and Potrzebowice; (a) location of the research areas in Poland (P—Potrzebowice, M—Martew), (b) Martew research area red dots with numbers show locations of study plots), (c) Potrzebowice research area (red dots with numbers show locations of study plots).

The Martew research area is located in the Tuczno community and has an area of more than 400 ha. It was established in 1989. The forest complex consists of fresh coniferous forests, fresh mixed coniferous forests, and fresh mixed broadleaved forests [20]. On more than 90 study plots, comprehensive studies on, amongst others, pest insects, carabid beetles (Carabidae), and selected soil parameters are carried out.

The Potrzebowice research area, however, is located in the Potrzebowice Forest District. It is a forest complex of more than 400 ha. Research in this area started in 1988, but in 1992, the whole research area was destroyed by a forest fire. Nowadays, the area is composed mainly of pine stands [20] on which comprehensive studies have been carried out on 41 study plots since 2007.

2.2. Data Collection

Collection of data was carried out using pheromone traps of IBL-1 type [21] (Figure 2) with Lymodor as pheromone (Chemipan R&D Laboratories, Warsaw, Poland), starting from the turn of the month from June to July and finishing in the middle of September. Lymodor attracts the males of the Nun moth. In each study plot, one trap was installed. The traps were controlled, and the number of collected individuals was counted about every two weeks. This research design was maintained consistently throughout the entire long-term study.

Figure 2.

IBL-1 type pheromone trap in the field (Chemipan R&D Laboratories, Warsaw, Poland).

In the Martew research area, the inventory of the Nun moth was started on several study plots in 1989, but in 1996, the number of plots was significantly increased. Therefore, we present the data starting in 1996. From 2011, however, 20 study plots located in the Drawa National Park were excluded from the inventory. Therefore, these plots, as well as all other plots that were studied in less than 60% of the years, were removed from the analyses. However, not all of the other areas were studied every year either, so the number of active traps differed between the study years (Table 1). In a part of the research area, a control treatment of Nun moth larvae was performed on 26 May 2003, using a spray with the following composition: Nomolt 150SC 0.15 L, Ikar 95EC 0.50 L, and water 1.35 L [13]. Nomolt 150SC disrupts the larval metamorphosis process, and Ikar 95EC increases the insecticide’s adhesion to the leaf surface and facilitates its penetration into the plant.

Table 1.

Total number of individuals of the Nun moth, number of traps, individuals per trap, number of traps with an increase compared to the previous year, number of traps with no change compared to the previous year, and number of traps with a decrease compared to the previous year for the Martew research area in the years of study.

In the Potrzebowice research area, after the aforementioned forest fire, the Nun moth has been continuously studied on all 41 study plots since 2007.

For both research areas, data up to and including 2024 were used in the analyses.

For each year, the number of individuals counted at all controls was summarized for each study plot, and the total number of individuals was calculated. By dividing the total number by the number of traps, the number of collected individuals per trap was computed in order to compensate for differences due to different numbers of traps.

Except for the first year, the numbers of traps showing an increase, no change, or a decrease in collected individuals compared to the previous year were calculated.

In order to check the impact of climatic factors on the dynamics of the Nun moth populations, selected climate data were used. Data on temperature (average temperature in a given month, available till June 2024) and precipitation (total precipitation in a given month, available till April 2024) were taken for the closest location (i.e., Piła for temperature and Tuczno for precipitation) from the resources of the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

As measure for synchronization of the fluctuations at the individual study plots, we calculated the percentage share of plots with an increase in Nun moth numbers compared to the year before (years 1997–2024 for Martew and 2008–2024 for Potrzebowice) and as climatic factors we defined average temperature in coldest winter month, average temperature in warmest summer month, and precipitation in driest month for October–September period. All these values were tested for correlations with numbers of the Nun moths per trap, changes in numbers of the Nun moths per trap, i.e., number per trap (year)—number per trap (year − 1), and the growth factor, i.e., number per trap (year)/number per trap (year − 1), applying Spearman’s rs rank correlations using PAST version 4.03 [22].

3. Results

Altogether, in the Martew research area, 112,453 individuals of the Nun moth were collected during the years of study reported in this paper (Table 1). In the Potrzebowice research area, the sum of individuals for the years included was 117,079 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total number of individuals of the Nun moth, number of traps, individuals per trap, numbers of traps with an increase compared to the previous year, numbers of traps with no change compared to the previous year, and number of traps with a decrease compared to the previous year for Potrzebowice, the research area in the years of study.

3.1. Martew Research Area

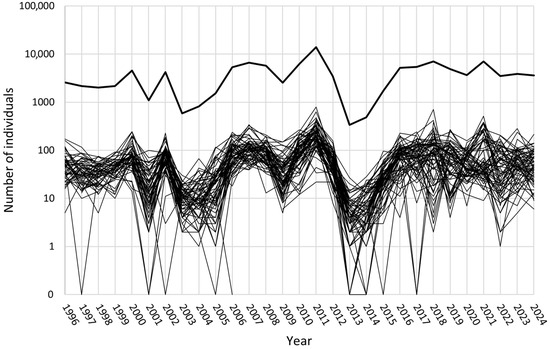

In the Martew research area, the total number of collected individuals in the study years ranged from a minimum of 339 in 2013 to a maximum of 13,997 in 2011. However, not every year the same number of pheromone traps was installed. The number of individuals per trap ranged from 5.5 (2013) to 225.8 (2011) (Table 1).

Pronounced “peaks” in total numbers of individuals are visible in 2000, 2002, 2011 (with a particular high number of total individuals), and 2021 (Figure 3). Except for 2021, in all these years, a high number of plots showed an increase in collected individuals compared to the year before (Table 1). Based on an assessment of the situation in 2002 by the Regional Directorate of State Forests in Piła, the aforementioned control treatment was carried out in March 2003, influencing the results in 2003. Probably also because of this treatment, the number of collected individuals dropped at the majority of the sampling plots. In 2001, a decline in the majority of the plots was also observed.

Figure 3.

Fluctuations in the numbers of collected individuals at the study plots in the Martew research area over the years of the study. In order to visualize zero values, they were replaced by 0.1, and the axis label was adjusted. Bold line—sum of individuals.

Synchronization of Nun moth occurrence at the study plots (percentage share of plots with an increase in Nun moth numbers compared to the year before) was statistically significantly positively correlated with the number of Nun moth individuals per trap, changes in the number of Nun moth individuals per trap, and the growth factor. As could be expected, the highest significance was detected for the correlation with the growth factor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman’s rs-values and associated p-values for correlations of the percentage share of plots with an increase in Nun moth numbers compared to the year before with numbers of Nun moth individuals per trap, changes in numbers of Nun moth individuals per trap, and growth factors for the research areas Martew and Potrzebowice.

3.2. Potrzebowice Research Area

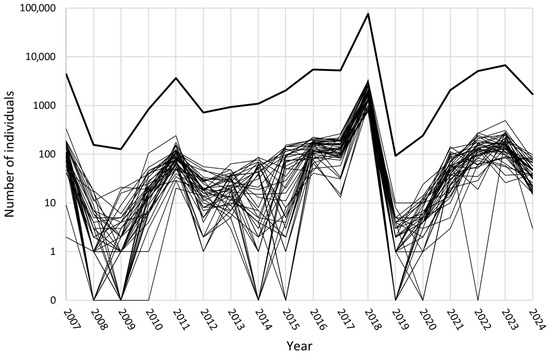

In the Potrzebowice research area, the number of collected individuals in the studied years ranged from a minimum of 92 in 2019 to a maximum of 76,352 in 2018, which means from 2.2 (2019) to 1862.2 (2018) individuals per trap (Table 2).

Pronounced “peaks” in total numbers of individuals of the Nun moth occurred in 2011 and very significantly in the year 2018. In 2011, the number of collected individuals increased on all plots compared to the year before (Table 2). Already in 2010, such an increase was observed on almost all of the study plots. In 2018, compared to the previous year, the number of individuals increased at all study plots by at least four times, up to almost 16 times at the individual plots (Figure 4). In the next year, however, the number of collected individuals dropped drastically at all plots. Before 2018 the dynamics in the research area were characterized by changes of much lower dimensions on a larger number of the study plots with a rather balanced proportion of plots showing an increase and plots showing a decrease in most of the years, except 2016.

Figure 4.

Fluctuations in the numbers of collected individuals at the study plots in the Potrzebowice research area over the years of the study. In order to visualize zero values, they were replaced by 0.1, and the axis label was adjusted. Bold line—sum of individuals.

Also in the Potrzebowice research area, synchronization of the study plots (percentage share of plots with an increase in Nun moth numbers compared to the year before) was positively correlated with the number of Nun moth individuals per trap, changes in the number of Nun moth individuals per trap, and the growth factor. All of these correlations were statistically significant, with the highest significance for the correlation with growth factor and the lowest for the correlation with the number of Nun moth individuals per trap (Table 3).

3.3. Climatic Factors

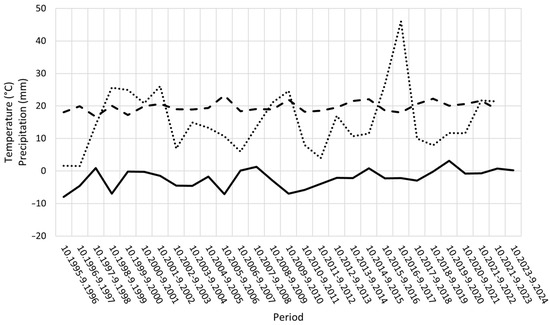

Average temperature in coldest winter month, average temperature in warmest summer month, and precipitation in driest month for October-September periods showed notable fluctuations (Figure 5). However, no statistically significant correlations with the parameters of the Nun moth populations were detected (Spearman rank correlations, n.s.).

Figure 5.

Average temperature in coldest winter month (°C) (solid line), average temperature in warmest summer month (°C) (broken line), and precipitation in driest month (mm) (dotted line) for October–September periods during the study.

4. Discussion

Using the data collected during the long-term studies, we were able to describe and analyze patterns of the dynamics in meta-populations of the Nun moth. When discussing the data for the research area Martew, it has to be taken into account that not the same number of study plots were monitored every year, which might have influenced the results. However, since we excluded plots that were studied in less than 60% of the years and standardized the total catches in the years of study by calculating the numbers of collected individuals per trap, we assess this influence to be rather small. Moreover, the control treatment in early 2003 at some of the study plots has to be considered. According to Szyszko et al. [13], analyzing changes in both adults and larvae of L. monacha, the control treatment had a significant impact on the Nun moth larvae, but not on the population dynamics of the insect in general. The increased larval mortality as a result of the treatment was set off by a fast growth in their occurrence after the treatment, with corresponding abundance models (comparable mean values calculated over the respective study plots) in areas with treatment and areas without treatment already in 2006.

Due to the forest fire in 1992, the Potrzebowice research object is much more homogeneous with respect to the age of the study plots than the Martew research area. It cannot be excluded that the degree of diversity in the age of the study plot had an impact on the patterns of the Num moth population dynamics.

The observed patterns of population dynamics of the Nun moth in both research areas and the detected correlations between the extent of synchronization between the study plots and the numbers of Nun moth individuals per trap, changes in these numbers, and growth factors suggest that synchronization of the fluctuations at the study plots is important. Very high total values of Nun moth occurrence are not a phenomenon of sudden, very strong increases only on single study plots, but are characterized by a high degree of synchronization between the plots. Our results suggest that when asynchronous fluctuations between subpopulations shift towards synchronization, the probability of large-scale outbreaks increases.

One important question concerns the reasons for synchronization and asynchronization. It is a fiercely discussed topic—which factors have a major influence on the population dynamics of animals as the Nun moth. In particular, two paradigms are debated—the first includes the idea of density-dependent processes and regulation, and the second one gives a greater place to density-independent processes, variability, and stochasticity [23]. Based on the latter, den Boer [24] stated that asynchronously fluctuating ‘interaction groups’ (‘subpopulations’) significantly increase the chance of survival of the population as a whole, because it results in ‘spreading the risk of extinction’. Several studies indicate that both types of processes are undergoing simultaneously. For example, research [25] showed that fluctuations of populations of the red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio L.) are due to the combined effects of density-dependent and density-independent processes. Similarly, demography and dispersal of pike (Esox lucius L.) seem to depend on a complex interplay between density-dependent and density-independent factors [26].

Dispersal between populations and sub-populations (interaction groups) also has an important influence on populations. The research on 74 species of carabid beetles in the Dutch countryside showed the importance of dispersal for the survival of local populations [8]. Based on studies on the spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana Clem.), regarding its population dynamics, a key role was attributed to dispersal, because it can synchronize the demography of distant populations [27]. According to Alrashedi et al. [10], taking into account the effects of dispersal is important when it comes to developing control strategies for managing meta-populations of pests. The adult Nun moths are strong flyers, which can disperse up to 3.5 km [28,29]. The Nun moth larvae are also able to spread over significant distances by wind dispersal [19,30]. Accordingly, the exchange of individuals between the study plots in our research areas can easily have taken place.

The population dynamics of L. monacha may also be influenced by climate change. Besides the already mentioned northward expansion of this species [18,19], life cycle parameters may change. For example, increased temperature may cause a faster larval development [16]. Also, for other pest insects, correlations between weather factors and species dynamics have been shown, for example, the Spruce budworm (C. fumiferana), a major pest of coniferous forests in North America [31,32]. The populations of these species were correlated with both host tree cone production (a food source) and high temperatures in May [32]. As for the Nun moth, the range of the related Spongy moth (Lymantria dispar L.) has recently also shown a clear northward expansion, presumably due to climate change [33].

Studies [34] have shown that forest structure, as well as warm and dry conditions, had an effect on the occurrence of mass outbreaks of L. monacha. For the related Spongy moth (L. dispar), both density-dependent and density-independent processes should be considered, because factors as host plants, weather, and natural enemies seem to influence its population dynamics [35].

We did not detect significant correlations between the fluctuations in the Nun moth populations and the climatic parameters studied by us. However, the impact of climatic factors cannot be excluded. We recognize a need for more detailed and comprehensive studies in this subject area.

To be able to predict forest pest mass occurrence is important for developing effective forest protection strategies. For forest stands in Siberia, it was demonstrated that remote sensing data can be a helpful tool in this context [36]. Studying a Polish forest site, Sikorski et al. [37] proposed that UAV multispectral mapping and vegetation data can be helpful tools for successful monitoring and prevention of infestations by Ips beetles. Ramazi et al. [38] used machine learning to determine predictors for infestations by a mountain beetle, and Rosselló et al. [39] included field monitoring data as an active part of a pest population density model simulation. Our long-term studies in two research areas in North-West Poland provided valuable insight into the population dynamics of the Nun moth, which might be useful when it comes to predicting future development of Nun moth (meta-)populations. We could demonstrate that the synchronization of sub-populations (interaction groups) seems to play an important role. As already proposed [13], improving the methods of forecasting the mass occurrences of the Nun moth should include the principles of the “spreading of risk” theory.

However, many other factors may play a role. For example, Szyszko [40], using a set of biotic and non-biotic data, hypothesized that stands threatened by pests are middle-aged pine stands that are characterized by a carabid beetle fauna with a low state of development. This implies that further studies are necessary, with a focus on both density-dependent factors and stochastic processes. Very important for understanding population dynamics are long-term studies [41]. More long-term studies on forest pest population dynamics, as those conducted by us, are necessary to develop strategies for sustainable forest management under changing climate conditions.

5. Conclusions

Our long-term studies provided new insight into the population dynamics of the Nun moth based on meta-population long-term data in Polish forests. Such information is crucial for achieving sustainable forest management. We could demonstrate that the studied Nun moth meta-populations show patterns in fluctuations of their sub-populations (interaction group) with phases of asynchronous and synchronous fluctuations.

Synchronization of fluctuations between sub-populations (interaction group) seems to be important when it comes to distinctive peaks in Nun moth numbers in the meta-populations. However, predicting the population dynamics of the Nun moth requires long-term studies, including research on both density-dependent factors and stochastic processes. This should be considered in future studies, including the application of modern analytical tools such as remote sensing and machine learning, which may enhance the prediction of forest pest fluctuations and strengthen forest protection strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and J.S.; methodology, A.S., I.D., A.J., M.K., K.S.-P. and J.S.; validation, A.S., I.D., A.J., M.K., K.S.-P. and J.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S., I.D., A.J., M.K., K.S.-P. and J.S.; data curation, A.S., I.D. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., I.D., A.J., M.K. and K.S.-P.; writing—review and editing, A.S., I.D., A.J., M.K. and K.S.-P.; visualization, A.S. and I.D.; supervision, A.S., I.D. and J.S.; project administration, A.J.; funding acquisition, A.S., I.D., A.J. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was long-term funded by the General Directorate of the State Forests (DGLP), Poland. The APC was funded by the General Directorate of the State Forests (DGLP), grant number MZ.271.3.8.2022.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the many people who have helped over the years, especially to Monika Bartłomiejczyk-Pikuła, Bernard Majer, and the late Krzysztof Płatek.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Logan, J.A.; Régnière, J.; Powell, J.A. Assessing the impacts of global warming on forest pest dynamics. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netherer, S.; Schopf, A. Potential effects of climate change on insect herbivores in European forests—General aspects and the pine processionary moth as specific example. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nature Clim. Change 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Ma, Z.; Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Lei, J. Forests and Forestry in Support of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Bibliometric Analysis. Forests 2022, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanski, I.; Gilpin, M. Metapopulation dynamics: Brief history and conceptual domain. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1991, 42, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Boer, P.J. Dispersal power and survival. Carabids in a cultivated countryside. Miscell. Papers LH Wagening. 1977, 14, 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- den Boer, P.J. The significance of dispersal power for the survival of species, with special reference to the carabid beetles in a cultivated countryside. Fortschr. Zool. 1979, 25, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hanski, I.; Schulz, T.; Wong, S.C.; Ahola, V.; Ruokolainen, A.; Ojanen, S.P. Ecological and genetic basis of metapopulation persistence of the Glanville fritillary butterfly in fragmented landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashedi, Y.; Mueller, M.; Townley, S. Adaptive, consensus-based control strategies for managing meta-populations of pests. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhold, A.M.; Koenig, W.D.; Bjørnstad, O.N. Spatial synchrony in population dynamics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Hong, P.; Luo, M.; Hu, H.; Wang, S. Dispersal increases spatial synchrony of populations but has weak effects on population variability: A meta-analysis. Am. Nat. 2022, 200, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyszko, J.; Płatek, K.; Schwerk, A. Wpływ zastosowania Nomoltu 150 dla zwalczania brudnicy mniszki (Lymantria monacha) w roku 2003 na występowanie tego gatunku w latach następnych. Sylwan 2009, 153, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Majunke, C.; Möller, K.; Funke, M. Die Nonne (Lymantria monacha L., Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae), 3rd, ed.; Waldschutz-Merkblatt 52; Landesforstanstalt: Eberswalde, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bejer, B. The Nun moth in European spruce forests. In Dynamics of Forest Insect Populations. Patterns, Causes, Implications; Berryman, A.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, T.; Hilszczański, J. The effect of temperature and humidity changes on insects development and their impact on forest ecosystems in the context of expected climate change. For. Res. Pap. 2013, 74, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr, J. Nun moth outbreak in Poland 1978–1984. Z. Angew. Ent. 1985, 99, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fält-Nardmann, J.J.J.; Tikkanen, O.-P.; Ruohomäki, K.; Otto, L.-F.; Leinonen, R.; Pöyry, J.; Saikkonen, K.; Neuvonen, S. The recent northward expansion of Lymantria monacha in relation to realized changes in temperatures of different seasons. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 427, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, M.; Viiri, H.; Tikkanen, O.-P.; Elfving, R.; Neuvonen, S. From a rare inhabitant into a potential pest—Status of the nun moth in Finland based on pheromone trapping. Silva Fenn. 2020, 54, 10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymitryszyn, I.; Szyszko, J.; Rylke, J. (Eds.) Terenowe Metody Oceny i Wyceny Zasobów Przyrodniczych/Field Methods of Evaluation and Assessment of Natural Resources; WULS-SGGW Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- PGL Lasy Państwowe. Instrukcja Ochrony Lasu; Dyrekcja Generalna Lasów Państwowych: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- den Boer, P.J.; Reddingius, J. Regulation and Stabilization Paradigms in Population Ecology; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- den Boer, P.J. Spreading of risk and stabilization of animal numbers. Acta Biotheor. 1968, 18, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasinelli, G.; Schaub, M.; Hӓfliger, G.; Frey, M.; Jakober, H.; Müller, M.; Stauber, W.; Tryjanowski, P.; Zollinger, J.-L.; Jenni, L. Impact of density and environmental factors on population fluctuations in a migratory passerine. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.O.; Winfield, I.J.; Vøllestad, A.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Stenseth, N.C. Density dependence and density independence in the demography and dispersal of Pike over four decades. Ecol. Monogr. 2007, 77, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroque, J.; Wittische, J.; James, P.M.A. Quantifying and predicting population connectivity of an outbreaking forest insect pest. Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 37, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, N.; Allen, E.A. Nun Moth—Lymantria monacha; Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Pacific Forestry Centre: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Molet, T. CPHST Pest Datasheet for Lymantria monacha; USDA-APHIS PPQ-CPHST; NC State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Keena, M. Nun moth. In The Use of Classical Biological Control to Preserve Forests in North America; Van Driesche, R., Reardon, R., Eds.; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2014; pp. 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Nenzén, H.K.; Peres-Neto, P.; Gravel, D. More than Moran: Coupling statistical and simulation models to understand how defoliation spread and weather variation drive insect outbreak dynamics. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.; Régnière, J.; Therrien, P. Bottom-up factors contribute to large-scale synchrony in spruce budworm populations. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarev, V.I.; Klobukov, G.I.; Napalkova, V.V.; Akhanaev, Y.B.; Pavlushin, S.V.; Yakimova, M.E.; Subbotina, A.O.; Picq, S.; Cusson, M.; Martemyanov, V.V. Phenological Features of the Spongy Moth, Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae), in the Northernmost Portions of Its Eurasian Range. Insects 2023, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, R.; Möller, K.; Wenning, A.; Degenhardt, A.; Schröder, J. Importance of Ecological Variables in Explaining Population Dynamics of Three Important Pine Pest Insects. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalouni, U.; Schädler, M.; Brandl, R. Natural enemies and environmental factors affecting the population dynamics of the gypsy moth. J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, A.; Tarasova, O.; Soukhovolsky, V.; Ivanova, Y. Is It Possible to Predict a Forest Insect Outbreak? Backtesting Using Remote Sensing Data. Forests 2024, 15, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, P.; Archiciński, P.; Ciężkowski, W.; Kościelny, M.; Kościelna, A.; Schwerk, A. Forest ecosystem disturbance affects tree dieback from Ips bark beetles, evidence from UAV multispectral mapping. Sylwan 2023, 167, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazi, P.; Kunegel-Lion, M.; Greiner, R.; Lewis, M.A. Predicting insect outbreaks using machine learning: A mountain pine beetle case study. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 13014–13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, N.B.; Rossini, L.; Speranza, S.; Garone, E. Towards pest outbreak predictions: Are models supported by field monitoring the new hope? Ecol. Inform. 2023, 78, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszko, J. Planning of Prophylaxis in Threatened Pine Forest Biocoenoses Based on an Analysis of the Fauna of Epigeic Carabidae; Warsaw Agricultural University Press: Warsaw, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke, B.A.; Miller, D.A.W.; Janzen, F.J. What have long-term field studies taught us about population dynamics? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 50, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).