Abstract

This study examined changes in runoff responses in a 17.8 ha catchment, with a focus on quick and delayed runoff components associated with logging and replantation. In total, 176 precipitation events were observed from 2011 to 2019, including in the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods. Approximately 70% of the catchment, which was originally dominated by Pitch pine (Pinus rigida), was clearcut between November 2013 and November 2014 and subsequently replanted with Japanese cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa). Event-based results revealed that both quick and delayed runoff increased significantly under high-magnitude precipitation events (Pt > 60 mm), indicating that rainfall intensity primarily controlled the generation of event runoff. During the operation period, increases in quick runoff contributed to a larger quick-runoff fraction, whereas in the post-cutting period, replantation promoted hydrological recovery by increasing delayed runoff and extending the flow duration. These changes reflect shifts in internal hydrological pathways associated with forest removal and regrowth. Overall, the results highlight that the runoff responses to clearcutting and replantation are strongly mediated by event-scale runoff components and rainfall intensity.

1. Introduction

Clearcutting is practiced widely in forest management; it involves the concentrated harvesting of all trees in a forest, similar to commercial logging, i.e., complete removal of the tree layer and subsequent regeneration of even-aged stands [1]. Clearcutting greatly constrains species inhabiting plantations and can dramatically alter the composition of understory plant species [2]. Additionally, clearcutting indirectly affects soil aggregate composition and stability by influencing aboveground vegetation growth, soil hydrothermal conditions, and microbial activity (e.g., [3,4]). In turn, these changes can significantly influence hydrological processes and runoff generation in forested catchments.

Although numerous studies have investigated the general hydrological impacts of clearcutting, changes in runoff responses following replantation, especially under intensive forest management and species-specific reforestation practices, remain poorly understood (e.g., [5,6]). Filling this knowledge gap is critical for forested headwater catchments, where even small hydrological changes can influence regional water resources. Moreover, understanding the runoff responses associated with replantation following clearcutting is essential for ensuring forest ecosystem function and sustainable water resources.

The hydrological consequences of clearcutting are complex and vary depending on post-cutting conditions, especially replantation rate (e.g., [3]). For example, several studies [7,8,9] have reported that runoff from forest-dominated headwater catchments typically increases in the short term after clearcutting. However, clearcutting can also reduce runoff because regenerating young-growth tree stands increases evapotranspiration [10,11] and may cause water resource limitations in downstream areas over the long term [12]. In addition, mechanized harvesting can intensify soil disturbance, further enhancing overland flow and sediment transport [13,14,15]. In particular, the use of heavy timber machinery causes soil compaction and reduces both the macroporosity and infiltration capacity of soil (e.g., [16]).

Among plantation species, Japanese cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) is widely planted because of its high timber production and ecological restoration potential [17]. Many of these plantations are located in forested headwater areas, that contribute substantially to the downstream water supply [18,19,20,21]. Forested headwater streams are vital sources of potable water for communities worldwide and are frequently managed specifically for that purpose [22]. Therefore, promoting sustainable forest management from a water management viewpoint is essential for protecting downstream water availability (e.g., [23]).

Considering the complexities above, it is essential to investigate hydrological responses to clearcutting and replantation, particularly in relation to runoff characteristics, under intensive forest management. This study evaluated the hydrological impacts of clearcutting and subsequent Japanese cypress replantation in the southern region of the Republic of Korea. The specific objectives of this study were to: (1) examine catchment runoff responses to replanting after clearcutting and (2) evaluate dominant flow patterns during pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods using event-based analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

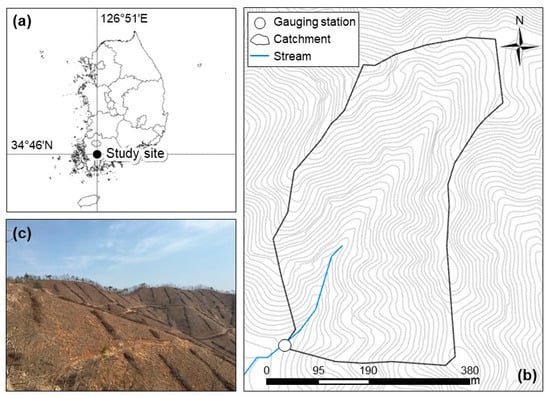

This study was conducted in a headwater catchment (17.8 ha) that drains Japanese cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) plantations located in the Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea (34°46′ N, 126°51′ E) (Figure 1). The catchments are managed by the National Institute of Forest Science (NiFoS) (Figure 1). The mean of the dominant slope gradients on the catchment is 28.8° and elevation ranges from 146 to 345 m above sea level. The soil is a slightly dry brown forest soil with underlying igneous rock. The mean annual precipitation (mm ± standard deviation; SD) from 2000 to 2019 at the Yichi Automatic Weather Station (AWS) was 1478.1 ± 318.2 mm (minimum–maximum values: 891.0–2126.5 mm), with 52% occurring from July to September. The mean annual temperature ± SD was 12.72 ± 0.5 °C (11.1–13.1 °C). Based on the Köppen–Geiger classification system [24,25], the climate type in the study area is Cfa (warm temperate fully humid hot summer). Climate classes are subclassified further according to precipitation and temperature conditions [26]. Before cutting, the catchment was dominated by pitch pine (Pinus rigida) and broad-leaved tree species. Following cutting, the area was replanted with a commercial Japanese cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) plantation. Stream channels were 0.74 km in length and 0.27 m/m in slope. The streamside vegetation consisted of forest cover and an understory that changed to open or closed types with a seasonal distribution (e.g., [27]).

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the study site and (b) monitoring station. The hillslope condition in (c) the catchment after cutting in 2016 (ref., [28]).

2.2. Experimental Design and Data Collection

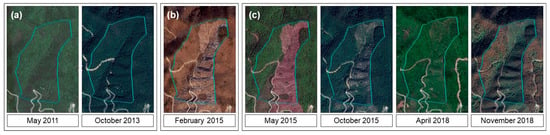

The catchment was felled to 70% clearcutting from September to November 2013 and July to December 2014. During the period, logged timber was dragged and gathered on skid trails by excavator, as a form of commercial clearcut harvesting. The observations were divided into pre-cutting period (April 2011–October 2013), an operation period (November 2013–November 2014), and a post-cutting period (April 2015–June 2019) (Figure 2). Because the catchment is frozen from December to March, measurements were not performed during this period (e.g., [27]). This winter monitoring gap may represent a potential source of bias because the hydrological responses under freeze–thaw conditions were not observed in this study.

Figure 2.

Photos of changes in forest conditions. (a) Pre-cutting (in May 2011 and October 2013). (b) Immediately after operation in February 2015. (c) Post-cutting in May and October 2015 and April and November 2018. The photos are based on publicly accessible satellite image-based maps.

Precipitation data were obtained from the Yichi AWS of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) Weather Data Service. API7 reflects soil moisture conditions near the surface, whereas API30 represents moisture in the deep soil matrix [29,30]. Water level in sharp-crested weirs (90° V-notch weirs) was measured using a capacitance water level recorder (OTT-Thalimedes Water Level Logger; OTT Mess-Technik, Kempten, Germany). Water level was measured at 10-min intervals for each catchment outlet. The runoff (mm) was divided by the projected catchment area.

2.3. Data Analysis

The selected precipitation events were defined based on an inter-storm period of at least 48-h. Because catchment runoff decreases quickly after precipitation ceases, a 48-h period without precipitation was considered sufficient to distinguish independent precipitation events [31,32]. In addition, precipitation events with total precipitation < 5 mm were excluded from the analysis [33].

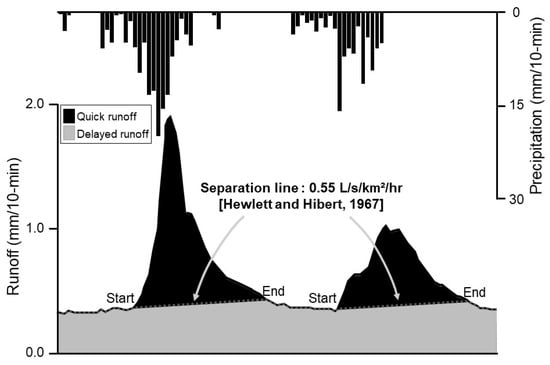

The hydrograph was separated into quick runoff (Qq) and delayed runoff (Qd) following the method of [34]. A fixed separation line with a recession slope of 0.55 L/s/km2/hr was extended from the inflection point on the falling limb of each event hydrograph [34] (Figure 3). This recession value has been widely applied in forested headwater, ≤1 km2 in drainage area with similar hydro-geomorphic characteristics (e.g., [18,32]), and the use of this method reduces subjective decisions by the researcher and enhances reproducibility compared with alternative approaches such as horizontal separation or groundwater recession-curve techniques (e.g., [35]).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the hydrograph separation procedure used in this study, which is based on [34].

The start of each event corresponded to the initial rise of the hydrograph, and the end of the event corresponded to the intersection between the falling limb and extended separation line. The period between these two points was treated as the duration of the runoff event. Flow duration for Qq and Qd was calculated as the cumulative active-flow time, defined as the total period over which each separated runoff component occurred during each event (e.g., [34,36]).

Runoff coefficients of quick runoff (Cq) and delayed runoff (Cd) were calculated by dividing each catchment runoff component (i.e., Qq and Qd) by total precipitation (Pt) (e.g., [37,38]). Runoff fractions of Qq and Qd (Qq/Qt and Qd/Qt) were calculated by dividing each catchment runoff component by total runoff (Qt) (e.g., [39,40]). To identify factors affecting runoff from the catchment, the relationships between total runoff responses and both precipitation and antecedent precipitation were examined. In this study, Pt and maximum 10-, 30-, and 60-min precipitation intensities were employed because rainfall intensity is related to the kinetic energy of raindrops during soil-splash detachment [41] and occurrence of overland flow [42]. The 7- and 30-day antecedent precipitation indices (API7 and API30, respectively) were calculated as rainfall parameters [31]. API7 reflects soil moisture conditions near the surface, whereas API30 represents moisture in the deep soil matrix [29,30].

The non-parametric Mann–Whitney statistical test was used based on assumptions of normality and variance equality (e.g., [43]), to compare mean differences in runoff responses characteristics among the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R v4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Precipitation Patterns and Catchment Runoff Responses

Annual precipitation at the Yichi AWS from 2011 to 2019 was from 891 to 2127 mm. The 20-year mean annual precipitation was 1478 mm. Notably, the precipitations in 2011, 2012, 2016, 2018, and 2019 were higher than the 20-year average. Mean monthly rainfall was 128 mm, with 703 mm as the greatest monthly rainfall (August 2012). The maximum 1-day precipitation in the pre-cutting period was recorded on 8 August 2011, at 148 mm, whereas those in the operation and post-cutting periods were 174 and 186 mm, respectively, on 2 August 2014 and 24 August 2018, respectively. In addition, the mean maximum 1-day precipitation for 20 years at the Yichi AWS was 155 mm.

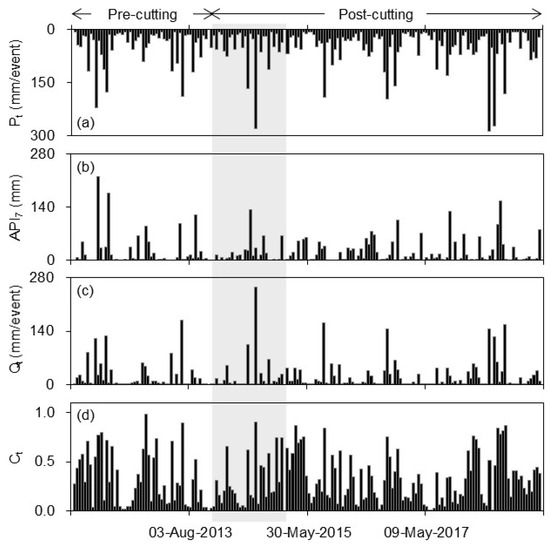

Among the 176 precipitation events observed over the entire monitoring period, 51, 28, and 97 occurred in the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods, respectively (Table 1, Figure 3). In addition, 44% of the events occurred during the flood season (June–September), whereas 34% and 23% occurred in the spring (April–May) and fall (October–November) seasons, respectively. The maximum total precipitation per event was 220.5 mm during the pre-cutting period (21–28 June 2011), 280.0 mm during the operation period (1–10 August 2014), and 286.5 mm during the post-cutting period (26 June–4 July 2018). Mean total precipitation per event were 45.1, 47.9, and 46.4 mm in the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods, respectively.

Table 1.

Precipitation event and runoff characteristics in three separate periods.

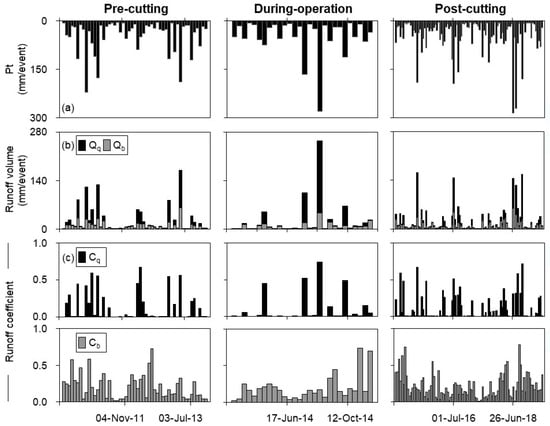

For all observed precipitation events, runoff responded quickly to precipitation, with increased precipitation amounts in the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods (Figure 4a,c). As shown in Table 1, API7 decreased during the operation period and API30 varied widely across all periods. However, neither API7 nor API30 exhibited a statistically significant relationship with Qt across the study periods.

The maximum Qt per event in the pre-cutting period was 169.6 mm, with 189.5 mm of Pt, and 19.5 mm/h precipitation intensity (3–11 June 2013). In the operation period, the maximum Qt per event was 254.7 mm, and with 280.0 mm Pt and 23.0 mm/h precipitation intensity (1–10 August 2014). The maximum Qt per event in the post-cutting period was 161.8 mm, with 192.0 mm of Pt and 20.5 mm/h precipitation intensity (11–15 July 2015).

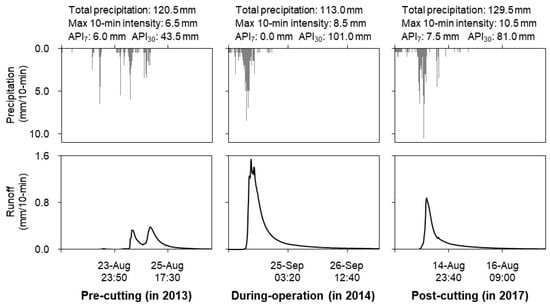

Figure 5 presents representative event-scale precipitation and runoff responses for the pre-cutting, during-operation, and post-cutting periods. These hydrographs were selected under similar precipitation conditions to facilitate comparison among periods and do not represent statistically derived groups. Despite similar precipitation characteristics among the three selected precipitation events, runoff responses differed markedly across periods (Figure 5). Peak runoff per event was 0.38 mm (38.1 mm total runoff) in the pre-cutting period, increased substantially to 1.54 mm (66.3 mm total runoff) during the operation period, and then declined to 0.87 mm (44.3 mm total runoff) in the post-cutting period (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

(a) Total precipitation (Pt, mm/event), (b) 7-day antecedent precipitation index (API7, mm), (c) total runoff (Qt, mm/event), and (d) total runoff coefficient (Ct, dimensionless) during 176 observed precipitation events from 2011 to 2019. The shaded area indicates operation period.

Figure 5.

Precipitation (P, mm/10-min) and runoff (Q, mm/10-min) responses for selected precipitation events during pre-cutting (22–27August 2013), operation (23–26 September 2014), and post-cutting (13–17 August 2017). API7 and API30 indicate 7- and 30-day antecedent precipitation indices.

3.2. Catchment Runoff Component Analysis

The precipitation indices, as runoff response characteristics, were used to determine relative changes in runoff generation and dominant flow during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

For all observed precipitation events, quick runoff (Qq) and delayed runoff (Qd) responded to increased Pt, particularly during the operation period (Figure 6). Event runoff volume ranged from 0.0 to 107.4 mm for the Qq and 0.1 to 62.1 mm for the Qd in the pre-cutting period. The Qq and Qd were 0.0–207.2 and 0.3–47.6 mm in the operation period, and 0.0–129.8 and 0.1–58.4 mm in the post-cutting period, respectively (Figure 6a). The flow durations of Qq were 4.3, 1.7, and 6.4 days during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods, respectively. The flow durations of Qd were 199.2, 116.6, and 359.1 days, respectively (Figure 6b). Runoff coefficients of quick runoff (Cq) and delayed runoff (Cd) exhibited varied patterns in three separate periods, with increases in Cd being more pronounced than those of Cq during the post-cutting period (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

(a) Total precipitation (Pt, mm/event), (b) runoff volumes of quick and delayed runoff (Qq and Qd, mm/event), and (c) runoff coefficients (Cq and Cd, dimensionless) during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods.

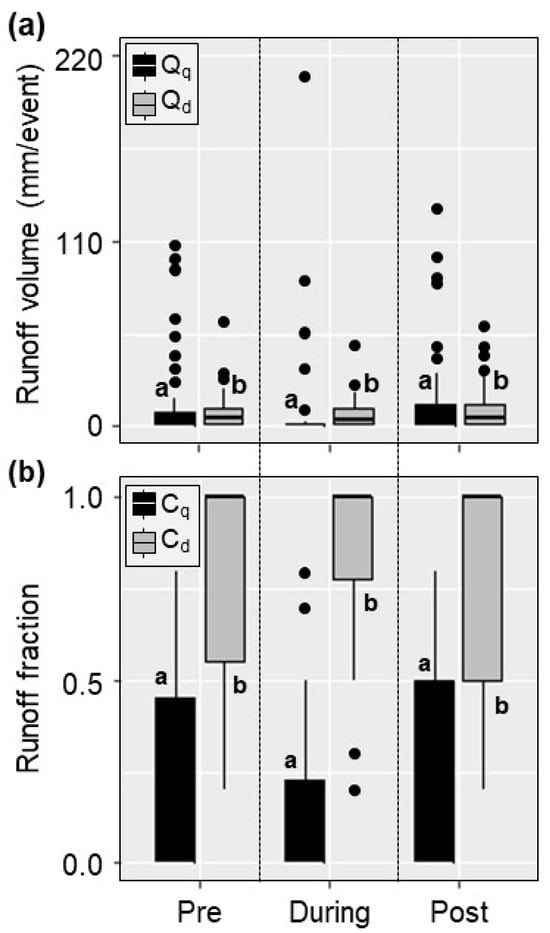

Differences in runoff volume and runoff fraction between Qq and Qd were significant across all periods, with increased Qq and Qd/Qt responses during the operation period, and subsequent reductions in Qq and Qd/Qt in the post-cutting period (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.01) (Figure 7). Across all periods, Qq was consistently lager than Qd (Figure 7a), however, Qd/Qt remained higher than Qq/Qt (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Box plots of (a) quick and delayed runoff volumes (Qq and Qd, mm/event) and (b) runoff fractions (Qq/Qt and Qd/Qt, dimensionless) during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods. The upper and lower hinges represent the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles, respectively). Whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and data points beyond the whiskers represent outliers. Different letters (a,b) denote statistically significant differences among periods based on the Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05).

3.3. Interaction Between Catchment Runoff Component and Precipitation

The Qq and Qd amounts were strongly correlated with Pt (Pearson correlation coefficient (r) = 0.817–0.950, p < 0.001), indicating that event magnitude was the dominant driver of runoff generation (Table 2). The Max 60-min intensity also showed moderate correlations with both components (r = 0.419–0.623, p < 0.05), suggesting an additional influence of rainfall intensity. During the pre- and post-cutting periods, Qq and Qd were significantly correlated with Pt and all intensity metrics (r = 0.412–0.908, p < 0.05), whereas during the operation period, these metrics were only significantly correlated with Pt and Max 60-min intensity (r = 0.458–0.950, p < 0.05). This pattern indicates that logging temporarily reduced the predictive relevance of short-duration intensities while both runoff components consistently showed the strongest association with Pt.

Table 2.

Correlation analysis between quick and delayed runoff amounts and precipitation characteristics.

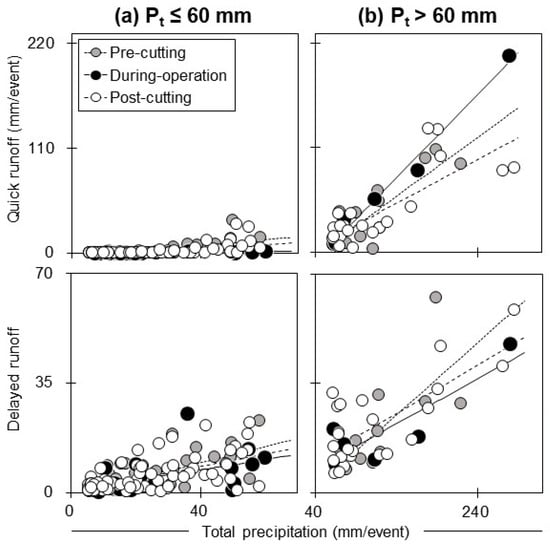

To examine the effect of Pt on Qq and Qd generation, precipitation events were classified into two groups (i.e., Pt ≤ 60 mm and Pt > 60 mm) across the three cutting periods (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The 60 mm threshold was determined empirically based on the distribution of the observed Pt and associated changes in runoff responses in the study catchment. It is also consistent with previously reported precipitation magnitudes associated with changes in dominant runoff generation processes (e.g., [44,45]). Here, for low-magnitude precipitation events (Pt ≤ 60 mm), both Qq and Qd increased slightly with Pt and exhibited no distinct differences among the three periods (Figure 8a). However, when Pt exceeded approximately 60 mm, corresponding to high-magnitude precipitation events (Pt > 60 mm) with 7.0–48.0 mm of Max 60-min intensity, Qq and Qd increased linearly with an increase in Pt. In particular, the Qq of the operation period was significantly higher than those of the pre- and post-cutting periods (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

Relationship between total precipitation (mm/event) and both quick and delayed runoff amounts (mm/event) of (a) total precipitation (Pt) ≤ 60 and (b) Pt > 60 mm during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods. Solid and dashed lines indicate regression relationships fitted for each period within the two precipitation groups.

Table 3 shows that the relationships between Pt and both Qq and Qd for Pt > 60 mm were strong, with R2 values of 0.50–0.99 and all slopes significant at p < 0.01 in three periods. In contrast, the models for Pt ≤ 60 mm showed low R2 values, indicating that Pt explained only a limited portion of the Qq and Qd responses during low-magnitude precipitation.

Table 3.

Summary of the regression analyses for total precipitation and quick and delayed runoff amounts.

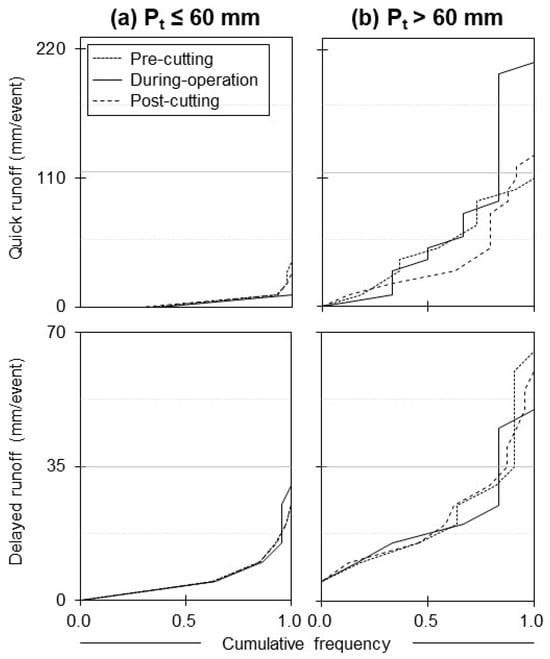

These patterns shown in Figure 8 were consistently reflected in the cumulative distribution patterns (Figure 9). In the case of low-magnitude precipitation events (Pt ≤ 60 mm), both Qq and Qd exhibited nearly identical cumulative distributions across the three periods (Figure 9a). However, for high-magnitude precipitation events (Pt > 60 mm), the cumulative distribution of Qq shifted notably toward higher values during the operation period (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

Cumulative frequency distributions of quick and delayed runoff amounts (mm/event) for (a) total precipitation (Pt) ≤ 60 and (b) Pt > 60 mm during the pre-cutting, operation, and post-cutting periods. Gray dashed and solid lines represent the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Clearcutting and Replantation on Runoff Responses

Event changes in runoff ratios in the operation-period were relatively dry compared to those in both pre- and post-cutting periods due to the sparse understory vegetation with low soil moisture (Figure 4). This was because hydrological responses to any given precipitation are strongly scale dependent [29,42]. In addition, the dominant hydrological processes in headwater catchment may differ in association with differences in vegetation type, topography, and soil properties [46,47,48]. Similarly, Oda et al. [49] reported that changes in canopy interception appeared to account for runoff response following clearcutting and the subsequent runoff recovery in a coniferous forest.

Clearcutting and associated ground-based logging operations increase soil surface flow connectivity and promote rapid concentrated flow along skid trails and logging roads [50,51]. These compacted and hydraulically efficient pathways shorten flow paths, decrease surface roughness, and provide preferential routes for water movement, thereby offering a mechanistic explanation for the observed increase in Qq, particularly during high-magnitude precipitation events. Moreover, the dominant flow pathway tends to shift from subsurface to surface flow (i.e., overland flow) as soil compaction and structural degradation reduce the infiltration capacity and near-surface water storage, thereby increasing runoff rates under severe disturbance (e.g., [52,53,54]).

The removal of vegetation cover associated with forest harvesting further increases average surface runoff volumes and total water yield in a given land area by reducing canopy interception and root-mediated soil structure [55]. In addition, mechanized harvesting can intensify soil disturbance, particularly along skid trails and extraction routes, thereby enhancing both overland flow generation and sediment transport [13,14,15]. These cumulative impacts highlight the importance of assessing the complex interactions between vegetation and hydrological processes at multiple scales when evaluating runoff responses to forest management (e.g., [46,56,57]). Moreover, understanding both the magnitude and persistence of clearcutting effects on runoff in headwater catchments is essential for conserving water resources (e.g., [12,58]). This pattern is likely associated with forest disturbance, whereby reduced infiltration and altered soil-surface flow pathways promote rapid runoff generation largely independent of antecedent moisture conditions [59]. Despite similar event runoff pathways in the clearcutting and replantation treatments (Figure 4), the increase in Qq observed following clearcutting may intensify shear stress on hillslopes and within channels, thereby potentially accelerating erosion rates (e.g., [53,60]).

For the precipitation events analyzed in this study, peak runoff followed peak precipitation almost immediately and discharge receded rapidly once precipitation ceased (Figure 4), indicating a highly responsive, surface-driven runoff regime. Although antecedent precipitation indices (API7 and API30) are widely recognized as important controls on runoff generation in forested catchments, they did not show significant relationships with discharge in this study, which indicates a fundamental shift in dominant hydrological processes during the operation period.

Under undisturbed forest conditions, API7 and API3 are commonly used as proxies for subsurface soil moisture storage and thus are closely linked to runoff response through their control on saturation development, storage capacity, and subsurface flow connectivity [29,30,42,61]. However, during the operation period, heavy machinery use, repeated passes along temporary skid trails, and timber extraction activities likely compacted the surface soil, reduced macroporosity, and lowered the infiltration capacity (e.g., [16,52,62]). These structural changes diminished the soil’s ability to store and transmit antecedent moisture, thereby weakening the hydrological relevance of antecedent precipitation index as a control on runoff.

Instead, precipitation was rapidly converted into infiltration-excess overland flow and routed along compacted surface pathways, bypassing the subsurface soil matrix that would normally regulate runoff through antecedent moisture (e.g., [54,63,64,65]). As a result, event-scale runoff was governed more strongly by rainfall intensity and surface hydrological connectivity than by pre-event soil moisture conditions.

Such mechanisms are consistent with previous studies showing that the cumulative hydrological impacts of clearcutting depend on local precipitation regimes and catchment properties [66] and forest harvesting increases the proportion of precipitation that becomes runoff and alters runoff pathways within forested catchment [67].

4.2. Dominant Catchment Flow After Clearcutting and Replantation

The runoff response characteristics based on PT (Figure 6), suggest that Qq responded more sensitively to canopy removal during the operation period and subsequent recovery than Qd in the post-cutting period. The flow duration of Qq increased by approximately 48.6% and that of Qd increased by approximately 80.3% after clearcutting with replantation, when compared with the pre-cutting period, demonstrating that forest regrowth promotes longer and more stable discharge. The results suggest that clearcutting temporarily reduces soil infiltration [68] and initial increases in Qq (i.e., higher Qq contributions) [69]. Swank et al. [70] also reported that an immediate catchment response to forest harvesting is increased water yield owing to a reduction in total ecosystem evapotranspiration and an increase in runoff.

The observed temporary increase Qq of the operation period represented a hydrological response to clearcutting, whereas the consistently higher Qd/Qt indicated that the overall runoff generation remained predominantly attributable to Qd following replantation (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Four dominant hydrological flow paths may affect runoff responses in headwater catchments: Hortonian overland, saturation overland, subsurface, and bedrock flows [29,42,71,72,73]. From these flow paths affected cutting, in our study catchment, we found that the contribution of Qq was greater than that of the Qd, particularly during the operation period (e.g., [68,69,74]).

Increases in Qd were much more pronounced than changes in Qq slightly (although not significant) (Figure 6). We found that Qd increased slightly (but not significantly) after clearcutting and replantation. This is because the increased total runoff generated by the increased net precipitation did not contribute directly to increases in the Qq component in the pre- and post-cutting periods (Figure 6). In addition, event runoff responses in our study catchment were mostly associated with subsurface flow in the soil matrix, rather than with bedrock flow (e.g., [32]). Thus, our findings indicate that the fraction between Qq and Qd changed significantly before and after clearcutting and replantation (Figure 7).

In addition, event-based analyses revealed that both runoff components were controlled strongly by event magnitude (Pt > 60) and max 60-min intensity, suggesting that high and intense precipitation govern catchment runoff behavior under different forest conditions (Figure 8). For low-magnitude precipitation events (Pt ≤ 60 mm), both Qq and Qd exhibited nearly identical cumulative distributions across the three periods, indicating minimal clearcutting effects on runoff generation under low-rainfall conditions (Figure 9a). However, for high-magnitude precipitation events (Pt > 60 mm), the cumulative distribution of Qq shifted notably toward higher values during the operation period, suggesting enhanced Qq response after forest disturbance (Figure 9b). For instance, according to Reid and Dunne [75] and Sidle et al. [76], soil infiltration on roads and skid trail surfaces was low enough to generate overland flow and resultant soil. In addition, Wemple et al. [74] showed that the logging roads was associated with increasing Qq generation and modified flow routing through extensions to the drainage network. The variations in hydrological responses to forest practices may be related to the spatial patterns of forest management and the dominant hydrological pathways (e.g., [32]). Thus, under precipitation, disturbance by heavy machines on skid trails could accelerate elevation of Qq and Qd/Qt during the operation period (Figure 7). In contrast, reduced Qq and Qq/Qt were observed in the post-cutting period associated with canopy recovery, changes in net precipitation, soil water availability, and evapotranspiration after clearcutting and replantation (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). These results were associated with hydrological responses to forest disturbances and gradual recovery after replantation [10,77]. If such a pattern continued for several years after clearcutting with replanting, forest cover and streamflow are generally expected to vary inversely because reduced forest cover leads to less transpiration and interception loss [67,78]. Such trends indicate that, as canopy recovery becomes re-established, evapotranspiration gradually increases and runoff returns to pre-cutting level, reflecting the hydrological recovery of the replanted forest. For instance, Mason et al. [79] observed that trees had been successfully established at all sites, and that in most cases canopy closure occurred within about 10 years after clear cutting in replanted Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis). Likoski et al. [80] showed that the four years after logging, canopy recovery was observed, with canopy variables recovering pre-clearcutting levels.

Therefore, detailed hydrological observations of the catchment can also identify the factors and processes that cause changes in runoff response. Such studies could provide quantitative evidence supporting sustainable forest management practices that balance timber harvesting with catchment water conservation as reforestation, which plays a crucial role in re-establishing subsurface flow pathways and restoring hydrological stability in a managed forest catchment. Moreover, it is important to recognize that forest disturbance also influences surface runoff (e.g., [32]) and mass movements (e.g., sediment and nutrient transport; [60,81]). Furthermore, studies that integrate transported sediment and eroded soils would provide important data on how observed hydrological changes translate into geomorphic and biogeochemical impacts after replantation following clearcutting. Using an event-based analysis with 176 precipitation events allowed us to minimize temporal confounding and interpret Qq and Qd responses mechanistically in relation to forest disturbance and replantation.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Changes in runoff responses were investigated after replantation following clearcutting in a headwater catchment draining coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest. Our main findings are as follows: (1) Quick runoff increased during the operation period, especially under high-magnitude precipitation events (Pt > 60 mm), indicating that forest disturbance temporarily enhanced rapid runoff pathways; (2) quick runoff decreased while delayed runoff increased during the post-cutting period, reflecting a shift toward slower subsurface flow contributions as canopy cover and interception gradually recovered; and (3) event runoff responses were strongly governed by rainfall intensity, with the greatest changes in quick and delayed runoff occurring under large and intense precipitation events. Our results indicate that reforestation effectively mitigates the rapid runoff response induced by clearcutting, thereby contributing to hydrological stabilization through increased delayed flow and extended flow duration. These findings demonstrate that clearcutting and subsequent replantation alter the balance between quick and delayed runoff in a headwater catchment, shifting dominant flow pathways over time. Therefore, by linking these event-scale hydrological responses to the cutting phases, this study directly addresses its stated objectives and provides insights into how forest disturbance and regrowth regulate runoff generation in forested headwater systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N. and H.L.; methodology, S.N. and H.L.; software, S.N. and H.L.; validation, S.N. and H.L.; formal analysis, S.N. and H.L.; investigation, H.L. and H.T.C.; resources, H.L. and H.T.C.; data curation, S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.; writing—review and editing, S.N. and H.L.; visualization, S.N. and Q.L.; supervision, H.T.C. and B.C.; project administration, H.T.C. and B.C.; funding acquisition, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out with the support of the “Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. FE0100-2025-04-2025)” provided by the National Institute of Forest Science.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not available publicly as they are from a project for obtaining specific research results and because of the intellectual property rights at the National Institute of Forest Science.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fedrowitz, K.; Gustafsson, L. Does the amount of trees retained at clearfelling of temperate and boreal forests influence biodiversity response? Environ. Evid. 2012, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.B.; Platt, K.H.; Coker, R.E.J. Understory species composition patterns in a Pinus radiata D. Don plantation on the central North Island volcanic plateau, New Zealand. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1995, 25, 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, R.J.; Kimmins, J.P. The ecological effects of clear-cutting. Environ. Rev. 1993, 1, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Tan, B.; Li, J.; Xu, H. Effects of Strip Clearcutting and Replanting on the Soil Aggregate Composition and Stability in Cunninghamia lanceolata Plantations in Subtropical China. Forests 2025, 16, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patric, J.H. Effects of wood products harvest on forest soils and water relations. J. Environ. Qual. 1980, 9, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, J.M.; Beall, F.D.; Webster, K.L.; Hazlett, P.W.; Creed, L.F.; Semkin, R.G.; Jeffries, D.S. Hydrologic response to and recovery from differing silvicultural systems in a deciduous forest landscape with seasonal snow cover. J. Hydrol. 2018, 557, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J.M.; Hewlett, J.D. A review of catchment experiments to determine the effect of vegetation changes on water yield and evapotranspiration. J. Hydrol. 1982, 55, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harr, R.D. Potential for augmenting water yield through forest practices in western Washington and western Oregon. Water Resour. Bull. 1983, 19, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stednick, J.D. Monitoring the effects of timber harvest on annual water yield. J. Hydrol. 1996, 176, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, J.W.; Adams, M.B.; Corbett, E.S.; Verry, E.S.; Lynch, J.A. Long-Term impacts of forest treatments on water yield: A summary for Northeastern USA. J. Hydrol. 1993, 150, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréassian, V. Waters and forests: From historical controversy to scientific debate. J. Hydrol. 2004, 291, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, J.I.; Finér, L.; Laurén, A.; Piirainen, S.; Launiainen, S. Effects of clear-cutting on annual and seasonal runoff from a boreal forest catchment in eastern Finland. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 304, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greacen, E.L.; Sands, R. A review of compaction of forest soils. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1980, 18, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenbrenner, J.W.; Robichaud, P.R.; Brown, R.E. Rill erosion in burned and salvage logged western montane forests: Effects of logging equipment type, traffic level, and slash treatment. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, K.; Mokharuddin, A.M.; Nik Muhamad, M. Surface runoff and soil loss from a skid trail and a logging road in a tropical forest. J. Trop. For. Sci. 1995, 7, 558–559. [Google Scholar]

- Malmer, A.l.; Grip, H. Soil disturbance and loss of infiltrability caused by mechanized and manual extraction of tropical rain-forest in Sabah, Malaysia. For. Ecol. Manage 1990, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-G.; Kang, H.-M. Characteristics of Vegetation Structure in Chamaecyparis obtusa stands. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2015, 29, 907–916. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, T.; Sidle, R.C.; Richardson, J.S. Understanding processes and downstream linkages of headwater systems. Bioscience 2002, 52, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.J.; Han, D.H. A Small Stream Management Plan to Protect the Aquatic Ecosystem; Korea Environment Institute Report (No. RE-09); Korea Environment Institute (KEI): Sejong-Si, Republic of Korea, 2008; pp. 1–149. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Jun, J.H.; Kim, K.H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Choi, H.T.; Jeong, Y.H. Variation of suspended solid concentration, electrical conductivity and pH of stream water in the regrowth and rehabilitation forested catchments. South Korea. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2007, 96, 21–28. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.C.; Lee, H.H. Variations of stream water quality caused by discharge change-at a watershed in Mt. Palgong. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2000, 89, 342–355. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N.; Stolton, S. Running Pure: The Importance of Forest Protected Areas to Drinking Water; Research Report for the World Bank and WWF Alliance for Forest Conservation and Sustainable Use; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; WWF Alliance for Forest Conservation and Sustainable Use: Gland, Switzerland, 2003; ISBN 2-88085-262-5. [Google Scholar]

- Šach, F.; Švihla, V.; Černohous, V.; Kantor, P. Management of mountain forests in the hydrology of a landscape, the Czech Republic-review. J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climateclassification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, K.R.; Akyuez, F.A.; Wiche, G.J.; Lin, W. Changes in seasonality and timing of peak streamflow in snow and semi-arid climates of the north-central United States, 1910–2012. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Jang, S.J.; Chun, K.W.; Lee, J.U.; Kim, S.W. Seasonal water temperature variations in response to air temperature and precipitation in a forested headwater stream and an urban river: A case study from the Bukhan River basin, South Korea. For. Sci. Technol. 2021, 17, 46–55. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Forest Science (NiFoS). Investigation of Runoff Characteristics in Forested Watersheds of the Jeollanam-Do; National Institute of Forest Science: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016; p. 6. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Sidle, R.C.; Tsuboyama, Y.; Noguchi, S.; Hosoda, I.; Fujieda, M.; Shimizu, T. Stormflow generation in steep forested headwaters: A linked hydrogeomorphic paradigm. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Shi, Z.H.; Zhu, H.D.; Zhang, H.Y.; Ai, L.; Yin, W. Soil moisture dynamics within soil profiles and associated environmental controls. Catena 2016, 136, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, T.; Asano, Y.; Uchida, T.; Onda, Y.; Sidle, R.C.; Miyata, S.; Ki, K.; Mizugaki, S.; Fukuyama, T.; Fukushima, T. Evaluation of storm runoff pathways in steep nested catchments draining a Japanese cypress forest in central Japan: A geochemical approach. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, X.B.; Gomi, T.; Miyata, S.; Sidle, R.C.; Kosugi, K.; Onda, Y. Runoff responses to forest thinning at plot and catchment scales in a headwater catchment draining Japanese cypress forest. J. Hydrol. 2012, 444–445, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, B.X.; Hiraoka, M.; Gomi, T.; Onda, Y.; Kato, H. Peak flow responses to strip thinning in a nested, forested headwater catchment. J. Hydrol. 2015, 29, 5098–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, J.D.; Hibbert, A.R. Factors Affecting the Response of Small Watersheds to Precipitation in Humid Areas. In Forest Hydrology; Sopper, W.E., Lull, H.W., Eds.; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S.; Chun, K.W.; Lee, J.U.; Kang, W.S.; Jang, S.J. Hydrograph Separation and Flow Characteristic Analysis for Observed Rainfall Events during Flood. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 54, 49–60. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durighetto, N.; Botter, G. On the relation between active network length and catchment discharge. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL099500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, A.; Villani, P.; Grayson, R.B.; Western, A.W. On the Relationship between Runoff Coefficient and Catchment Initial Conditions. In Proceedings of the MODSIM 2003 International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand Inc., Townsville, Australia, 14–17 July 2003; Volume 2, pp. 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Cheng, L.; Liu, P.; Qin, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.-Y. An analytical baseflow coefficient curve for depicting the spatial variability of mean annual catchment baseflow. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.T.T.; Ghafouri-Azar, M.; Bae, D.-H. Long-Term Variation of Runoff Coefficient during Dry and Wet Seasons Due to Climate Change. Water 2019, 11, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Ding, J.; Han, L. Quantifying the effects of human activities and climate variability on runoff changes using variable infiltration capacity model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanko, K.; Mizugaki, S.; Onda, Y. Estimation of soil splash detachment rates on the forest floor of an unmanaged Japanese cypress plantation based on field measurements of throughfall drop sizes and velocities. Catena 2008, 72, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, T.; Sidle, R.C.; Miyata, S.; Kosugi, K.; Onda, Y. Dynamic runoff connectivity of overland flow on steep forested hillslopes: Scale effects and runoff transfer. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W08411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Halbach, T.R.; Simcik, M.F.; Gulliver, J.S. Input characterization of perfluoroalkyl substances in wastewater treatment plants: Source discrimination by exploratory data analysis. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3101–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp-van Meerveld, H.J.; McDonnell, J.J. Threshold relations in subsurface stormflow: 1. A 147-storm analysis of the Panola hillslope. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W02410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrnčíř, M.; Šanda, M.; Kulasová, A.; Císlerová, M. Runoff formation in a small catchment at hillslope and catchment scales. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 2248–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stomph, T.J.; de Ridder, N.; Steenhuis, T.S.; van de Giesen, N.C. Scale effects of Hortonian overland flow and rainfall-runoff dynamics: Laboratory validation of a process-based model. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2002, 27, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammeraat, E.L.H. Scale dependent thresholds in hydrological and erosion response of a semi-arid catchment in Southeast Spain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Kim, K.; Tsuboyama, Y.; Hosoda, I. Development and application of a simple hydrogeomorphic model for headwater catchments. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W00H13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, T.; Egusa, T.; Ohte, N.; Hotta, N.; Tanaka, N.; Green, M.B.; Suzuki, M. Effects of changes in canopy interception on stream runoff response and recovery following clear-cutting of a Japanese coniferous forest in Fukuroyamasawa Experimental Watershed in Japan. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croke, J.C.; Hairsine, P.B. Sediment delivery in managed forests: A review. Environ. Rev. 2006, 14, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Hiraoka, M.; Gomi, T.; Dung, B.X.; Onda, Y.; Kato, H. Suspended-Sediment responses after strip thinning in headwater catchments. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 12, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.D.; Sutherland, R.A.; Giambelluca, T.W. Acceleration of Horton overland flow and erosion by footpaths in an upland agricultural watershed in northern Thailand. Geomorphology 2001, 41, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Ziegler, A.D.; Negishi, J.N.; Nik, A.R.; Siew, R.; Turkelboom, F. Erosion processes in steep terrain—Truths, myths, and uncertainties related to forest management in Southeast Asia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 224, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemke, J.J.; Enderling, M.; Klein, A.; Skubski, M. The influence of soil compaction on runoff formation. A case study focusing on skid trails at forested andosol sites. Geosciences 2019, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etehadi Abari, M.; Majnounian, B.; Malekian, A.; Jourgholami, M. Effects of forest harvesting on runoff and sediment characteristics in the Hyrcanian forests, northern Iran. Eur. J. For. Res. 2017, 136, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis Castro, N.M.; Auzet, A.V.; Chevallier, P.; Leprun, J.C. Land use change effects on runoff and erosion from plot to catchment scale on the basaltic plateau of Southern Brazil. Hydrol. Process. 1999, 13, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Kosugi, K.I.; Nishi, Y.; Gomi, T.; Sidle, R.C.; Mizuyama, T. Spatial pattern of infiltration rate and its effect on hydrological processes in a small headwater catchment. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, J.D.; Helvey, J.D. Effects of forest clear-felling on the storm hydrograph. Water Resour. Res. 1970, 6, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Scharrón, C.E.; LaFevor, M.C. Effects of forest roads on runoff initiation in low-order ephemeral streams. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 8613–8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, T.; Moore, R.D.; Hassan, M.A. Suspended sediment dynamics in small forest streams of the Pacific Northwest. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2005, 41, 877–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocca, L.; Melone, F.; Moramarco, T. On the estimation of antecedent wetness conditions in rainfall–runoff modeling. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsuka, Y.; Gomi, T.; Hiraoka, M.; Miyata, S.; Onda, Y. Infiltration capacity and runoff characteristics of a forest road. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2014, 96, 315–322. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.D.; Giambelluca, T.W. Importance of rural roads as source areas for runoff in mountainous areas of northern Thailand. J. Hydrol. 1997, 196, 204–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imerson, A.C.; Verstraten, J.M.; van Mulligen, E.J.; Sevink, J. The effects of fire and water repellency in infiltration and runoff under Mediterranean type forest. Catena 1992, 19, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Shimizu, T. Restricted increases of water storage during storm evens owing to soil water repellency in a Japanese cypress plantation. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 2356–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, X. Forest disturbance thresholds and cumulative hydrological impacts. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2024WR037339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.D.; Wondzell, S.M. Physical hydrology and the effects of forest harvesting in the Pacific Northwest: A review. Am. J. Water Resour. 2005, 41, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemette, F.; Plamondon, A.P.; Prévost, M.; Lévesque, D. Rainfall generated stormflow response to clearcutting a boreal forest: Peak flow comparison with 50 world-wide basin studies. J. Hydrol. 2005, 302, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampe, E.A.; Segura, C.; Jones, J.A. Fifty years of runoff response to conversion of old-growth forest to planted forest in the HJ Andrews Forest, Oregon, USA. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, W.T.; Vose, J.M.; Elliott, K.J. Long-term hydrologic and ecosystem responses to forest cutting and regrowth in the southern Appalachians. For. Ecol. Manage 2001, 143, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Hirano, T.; Gomi, T.; Terajima, T. Hortonian overland flow from Japanese forest plantations—An aberration, the real thing, or something in between? Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 3237–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Kosugi, K.; Gomi, T.; Onda, Y.; Mizuyama, T. Surface runoff as affected by soil water repellency in a Japanese cypress forest. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, B.X.; Miyata, S.; Gomi, T. Effect of forest thinning on overland flow generation on hillslopes covered by Japanese cypress. Ecohydrology 2011, 4, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemple, B.C.; Jones, J.A.; Grant, G.E. Channel network extension by logging roads in two basins, Western Cascades, Oregon. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1996, 32, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L.M.; Dunne, T. Sediment production from forest road surfaces. Water Resour. Res. 1984, 20, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Sasaki, S.; Otsuki, M.; Noguchi, S.; Nik, R.A. Sediment pathways in a tropical forest: Effects of logging roads and skid trails. Hydrol. Process. 2004, 18, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhar, U.; Kermavnar, J.; Kozamernik, E.; Petrič, M.; Ravbar, N. The effects of large-scale forest disturbances on hydrology—An overview with special emphasis on karst aquifer systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 235, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeking, S.A.; Tarboton, D.G. Variable streamflow response to forest disturbance in the Western US: A large-sample hydrology approach. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, W.L.; McKay, H.M.; Weatherall, A.; Connolly, T.; Harrison, A.J. The effects of whole-tree harvesting on three sites in upland Britain on the growth of Sitka spruce over ten years. Forestry 2012, 85, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likoski, J.K.; Vibrans, A.C.; Silva, D.A.D.; Fantini, A.C. Canopy recovery four years after logging: A management study in a southern brazilian secondary forest secondary forest. Cerne 2021, 27, e-102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Tei, R.; Arai, H.; Onda, Y.; Kato, H.; Kawaguchi, S.; Gomi, T.; Dung, B.X.; Nam, S. Influence of strip thinning on nutrient outflow concentrations from plantation forested watersheds. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 5109–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).