Cooling Effects in Large Urban Mountains: A Case Study of Chengdu Longquan Mountains Urban Forest Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.2.1. Land Surface Temperature Data

2.2.2. Additional Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Land Surface Temperature Inversion

2.3.2. Spatiotemporal Analysis of LST

Classification of Heat Island Intensity

2.3.3. Spatial Quantification of Cooling Effects

2.3.4. Factors Affecting Cooling Effect

XGBoost Model and SHAP Explainability Method

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Evolution of the Urban Heat Island

3.2. Interannual Variation in the Summer Cooling Effect

3.3. Analysis of the Factors Influencing the Spatial Variation in Cooling Effect

3.3.1. Importance Ranking of Drivers of Cooling Intensity

3.3.2. Marginal Effects of Drivers on Cooling Intensity

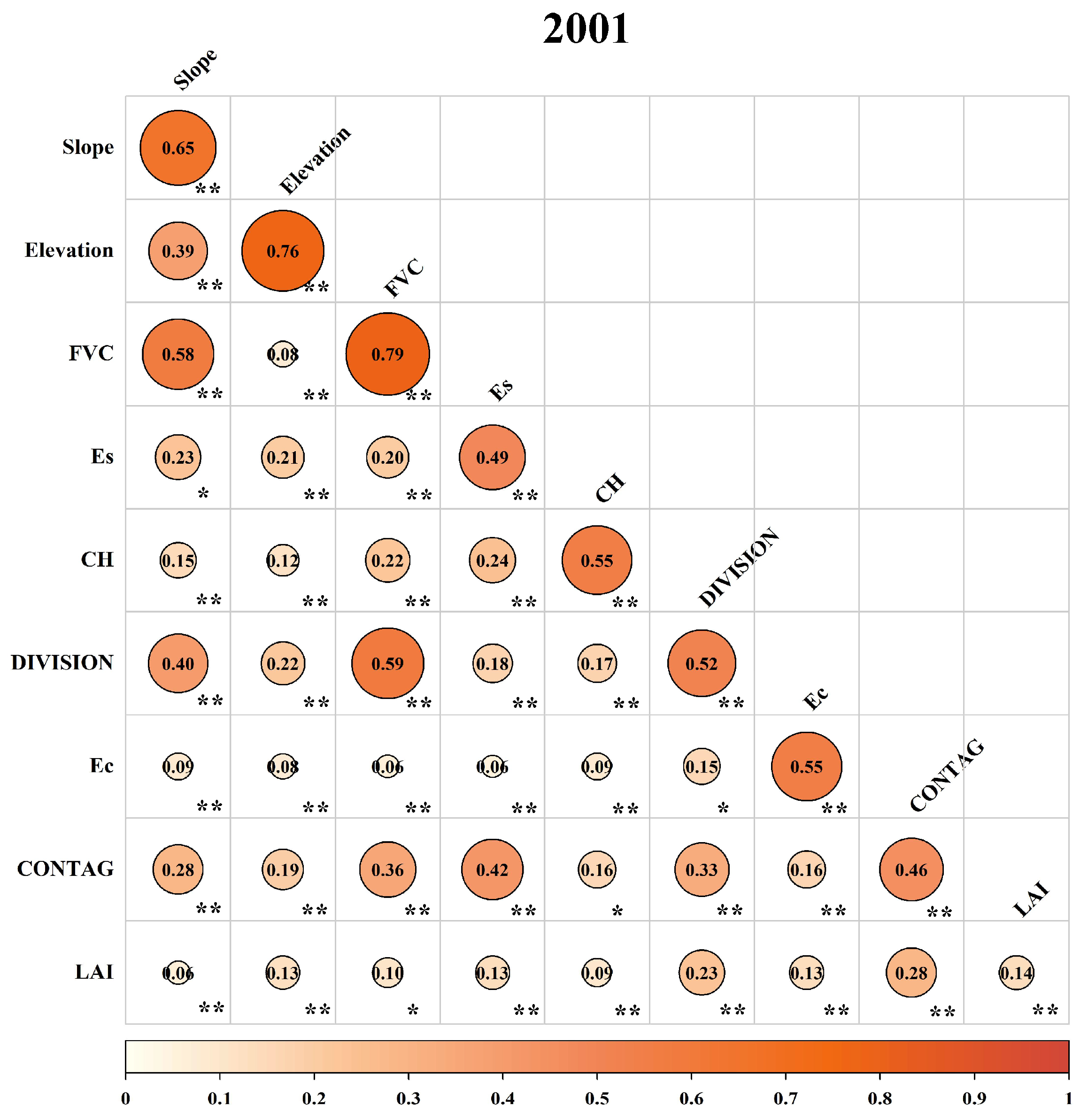

3.3.3. The Interaction of Driving Factors on Cooling Intensity

4. Discussion

4.1. Significant Temporal and Spatial Variations in the Thermal Environment of LMFP

4.2. Spatial Range of Cooling Effects of LMFP on Surrounding Areas

4.3. Key Driving Factors and Their Interactions in the Cooling Effects of LMFP over Time

4.4. Methodological Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UHI | Urban Heat Island | CH | Canopy Height |

| LUM | Large Urban Mountains | LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| LMFP | Longquan Mountain Forest Park | FVC | Fractional Vegetation Cover |

| LST | Land surface temperature | Es | Vegetation Transpiration |

| RTE | Radiative Transfer Equation | Ec | Soil Evaporation |

| PCD | Park Cooling Distance | CA | Class Area |

| PCA | Park Cooling Area | PD | Patch Density |

| PCI | Park Cooling Intensity | LPI | Largest Patch Index |

| PCE | Park Cooling Efficiency | SHDI | Shannon’s Diversity Index |

| MCI | Mountain Cooling Intensity | AI | Aggregation Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nations, U. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhan, W.; Zhou, B.; Tong, S.; Chakraborty, T.C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Du, H.; Middel, A.; Li, J.; et al. Dual impact of global urban overheating on mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Yu, Y. The impact of urban morphology on land surface temperature under seasonal and diurnal variations: Marginal and interaction effects. Build. Environ. 2025, 272, 112673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; DENNIS, L.Y.C.; LIU, C. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of Urban Heat Island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bherwani, H.; Singh, A.; Kumar, R. Assessment methods of urban microclimate and its parameters: A critical review to take the research from lab to land. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Remote sensing of urban heat islands from an environmental satellite. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1972, 53, 647–648. [Google Scholar]

- Diem, P.K.; Nguyen, C.T.; Diem, N.K.; Diep, N.T.H.; Thao, P.T.B.; Hong, T.G.; Phan, T.N. Remote sensing for urban heat island research: Progress, current issues, and perspectives. Remote Sens. Appl. 2024, 33, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yan, K.; Xiong, D.; Xu, P.; Yan, Y.; Lin, L. Cooling effects of urban parks under various ecological factors. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lai, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, B.; Tan, X.; Zeng, F.; Liang, S.; Xiao, A.; Shang, X. A study of the thermal comfort in urban mountain parks and its physical influencing factors. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 118, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terschanski, J.; Nunes, M.H.; Aalto, I.; Pellikka, P.; Wekesa, C.; Maeda, E.E. The role of vegetation structural diversity in regulating the microclimate of human-modified tropical ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, P.E.; Briles, C.E.; Whitlock, C.; Austin, A. Fire-regime complacency and sensitivity to centennial-through millennial-scale climate change in Rocky Mountain subalpine forests, Colorado, USA. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Shi, X.; Jin, X. Influences of wind direction on the cooling effects of mountain vegetation in urban area. Build. Environ. 2022, 209, 108663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Shangguan, D.; Wang, R.; Xie, C.; Li, D.; Cheng, X. Cold and Wet Island Effect in Mountainous Areas: A Case Study of the Maxian Mountains, Northwest China. Forests 2024, 15, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, N.C.; Arnone, E.; Gobiet, A.; Haslinger, K.; Kotlarski, S.; Notarnicola, C.; Palazzi, E.; Seibert, P.; Serafin, S.; Schoener, W.; et al. Climate Changes and Their Elevational Patterns in the Mountains of the World. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Ohta, T. Seasonal variations in the cooling effect of urban green areas on surrounding urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Song, J.; Huang, J.; Zhuang, C.; Guo, R.; Gao, Y. Synergistic cooling effects (SCEs) of urban green-blue spaces on local thermal environment: A case study in Chongqing, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menteş, Y.; Yilmaz, S.; Qaid, A. The cooling effect of different scales of urban parks on land surface temperatures in cold regions. Energ. Build. 2024, 308, 113954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Y.; Wang, J.; Sia, A. Perspectives on five decades of the urban greening of Singapore. Cities 2013, 32, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Kumilamba, G.; Yu, L. Optimizing green space configuration for mitigating land surface temperature: A case study of karst mountainous cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitanova, L.L.; Kusaka, H. Study on the urban heat island in Sofia City: Numerical simulations with potential natural vegetation and present land use data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algretawee, H. The effect of graduated urban park size on park cooling island and distance relative to land surface temperature (LST). Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yue, W.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, P.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Y.; He, T. Quantifying the cooling effect and benefits of urban parks: A case study of Hangzhou, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.A.; Colli, M.F.; Martinez, C.F.; Correa-Cantaloube, E.N. Park cool island and built environment. A ten-year evaluation in Parque Central, Mendoza-Argentina. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, W.; Yin, Y. Enhanced accessibility to park cooling services in developed areas: Experimental insights on the walkability in large urban agglomerations. Build. Environ. 2025, 272, 112665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Dan, Y.; Qiao, R.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, J. How to quantify the cooling effect of urban parks? Linking maximum and accumulation perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Sohn, W.; Lee, D. Urban cooling factors: Do small greenspaces outperform building shade in mitigating urban heat island intensity? Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganmohan, M.; Knapp, S.; Buchmann, C.M.; Schwarz, N. The Bigger, the Better? The Influence of Urban Green Space Design on Cooling Effects for Residential Areas. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Bao, Y. Cool island effects of urban remnant natural mountains for cooling communities: A case study of Guiyang, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y. Spatio-Temporal Features of Urban Heat Island and Its Relationship with Land Use/Cover in Mountainous City: A Case Study in Chongqing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Banjara, P.; Pandey, V.P.; Aryal, A.; Pradhan, P.; Al-Douri, F.; Pradhan, N.R.; Talchabhadel, R. Quantifying the cooling effects of blue-green spaces across urban landscapes: A case study of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, H. Exploring the impact of natural and human activities on vegetation changes: An integrated analysis framework based on trend analysis and machine learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Yu, J.; Xin, C.; Ye, T.; Wang, T.A.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Quantifying and Comparing the Cooling Effects of Three Different Morphologies of Urban Parks in Chengdu. Land 2023, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikhosravi, G.; Khalidi, S.; Shahmoradi, M. Effects of climates and physical variables of parks on the radius and intensity of cooling of the surrounding settlements. Urban Clim. 2023, 51, 101601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yim, S.H.L.; Heo, Y. Interpreting complex relationships between urban and meteorological factors and street-level urban heat islands: Application of random forest and SHAP method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowe, P.; Mutanga, O.; Odindi, J.; Dube, T. Effect of landscape pattern and spatial configuration of vegetation patches on urban warming and cooling in Harare metropolitan city, Zimbabwe. GISci. Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OTTLE, C.; STOLL, M. Effect of atmospheric absorption and surface emissivity on the determination of land surface temperature from infrared satellite data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 2025–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekertekin, A. Validation of Physical Radiative Transfer Equation-Based Land Surface Temperature Using Landsat 8 Satellite Imagery and SURFRAD in-situ Measurements. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2019, 196, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokdemir, N.; Marangoz, A.M.; Sekertekin, A. Satellite-Based Thermal Analysis of Water-Induced Cooling in Afyonkarahisar, Türkiye. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 76, 107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, G.; Markham, B.L.; Helder, D.L. Summary of current radiometric calibration coefficients for Landsat MSS, TM, ETM+, and EO-1 ALI sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsi, J.A.; Schott, J.R.; Palluconi, F.D.; Hook, S.J. Validation of a Web-Based Atmospheric Correction Tool for Single Thermal Band Instruments; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; p. 58820E. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Li, X.; Qian, W. Optimizing the spatial pattern of the cold island to mitigate the urban heat island effect. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, G.; Tian, G.; Jombach, S. Mapping and Analyzing the Park Cooling Effect on Urban Heat Island in an Expanding City: A Case Study in Zhengzhou City, China. Land 2020, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Sun, H.; Qi, J.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y. Examining water bodies’ cooling effect in urban parks with buffer analysis and random forest regression. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X. The influence of local background climate on the dominant factors and threshold-size of the cooling effect of urban parks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, D.; Ou, J.; Rui, Q.; Jin, B.; Zhu, Z.; Ding, G. Exploring the integrating factors and size thresholds affecting cooling effects in urban parks: A diurnal balance perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, H.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Rötzer, T.; Petzold, F.; Ludwig, F. Machine learning-based prediction of tree crown development in competitive urban environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 101, 128527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghale, B.; Mamgain, S.; Gupta, K.; Roy, A. Urban Parks and their Cooling Potential: Evaluating how Park Characteristics Affects Land Surface Temperature. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 48, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, T.; Yan, C. Seasonal variation in vegetation cooling effect and its driving factors in a subtropical megacity. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachofen, C.; Peillon, M.; Meili, N.; Bourgeois, I.; Grossiord, C. High transpirational cooling by urban trees despite extreme summer heatwaves. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronken-Smith, R.A.; Oke, T.R. Scale Modelling of Nocturnal Cooling in Urban Parks. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1999, 93, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yin, H.; James, P.; Hutyra, L.R.; He, H.S. Effects of spatial pattern of greenspace on urban cooling in a large metropolitan area of eastern China. Landsc. Urban Plan 2014, 128, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Tanaka, T.; Ohta, T. Impacts of land use and topography on the cooling effect of green areas on surrounding urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.F.; Daniel, J.S.G.; Dong, J.; Trigo, I.F.; Salvucci, G.D.; Entekhabi, D. Tropical Surface Temperature Response to Vegetation Cover Changes and the Role of Drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Peng, L.L.H.; Feng, N.; Wen, H.; Ling, Z.; Yang, X.; Dong, L. Spatial-temporal pattern in the cooling effect of a large urban forest and the factors driving it. Build. Environ. 2022, 209, 108676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sheng, S.; Xiao, H. The cooling effect of hybrid land-use patterns and their marginal effects at the neighborhood scale. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsa-Barreiro, J.; Li, Y.; Morales, A.; Pentland, A.S. Globalization and the shifting centers of gravity of world’s human dynamics: Implications for sustainability. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 239, 117923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, E.; Rajagopalan, P.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, Y. Review on the impact of urban geometry and pedestrian level greening on outdoor thermal comfort. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y. Monitoring surface urban heat island formation in a tropical mountain city using Landsat data (1987—2015). Isprs. J. Photogramm. 2017, 133, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Adu, B.; Wu, J.; Qin, G.; Li, H.; Han, Y. Spatial and temporal variations of drought in Sichuan Province from 2001 to 2020 based on modified temperature vegetation dryness index (TVDI). Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wu, F.; Dong, L. Influence of a large urban park on the local urban thermal environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, A.; Karachaliou, E.; Dosiou, A.; Tavantzis, I.; Stylianidis, E. Exploring patterns of surface urban heat island intensity: A comparative analysis of three Greek urban areas. Discov. Cities 2024, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevo, C.A.; Stralberg, D.; Nielsen, S.E.; Bayne, E. Topographic and vegetation drivers of thermal heterogeneity along the boreal—Grassland transition zone in western Canada: Implications for climate change refugia. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Season | Image Date | Cloud Cover (%) | Transit Time (UTC + 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Summer | 14 June 2001 | 8.7 | 10:31 |

| 2011 | Summer | 30 June 2011 | 6.3 | 10:29 |

| 2023 | Summer | 5 July 2023 | 7.9 | 10:30 |

| UHI Intensity Grade | Grading Method |

|---|---|

| Strong Negative UHI | Ts ≤ μ − 2std |

| Moderate Negative UHI | μ − 2std < Ts ≤ μ − std |

| Weak Negative UHI | μ − std < Ts ≤ μ |

| NO UHI | μ < Ts ≤ μ + std |

| Weak UHI | μ + std < Ts ≤ μ + 2std |

| Moderate UHI | μ + 2std < Ts ≤ μ + 3std |

| Strong UHI | Ts > μ + 3std |

| Type | 2001 Summer | 2011 Summer | 2023 Summer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Cooling | 37.59% | 19.18% | 22.48% |

| Strong Cooling | 15.25% | 14.67% | 33.60% |

| Moderate Cooling | 17.57% | 20.01% | 9.19% |

| Weak Cooling | 18.02% | 18.72% | 18.65% |

| Very weak Cooling | 11.56% | 27.43% | 16.08% |

| Year | Season | PCD (m) | PCI (°C) | PCA (km2) | PCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Summer | 330 | 2.623 | 101.121 | 14.83 |

| 2011 | Summer | 390 | 2.751 | 117.048 | 17.17 |

| 2023 | Summer | 420 | 2.785 | 124.844 | 18.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Y.; Lin, L.; Pan, J.; Feng, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, T.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, L. Cooling Effects in Large Urban Mountains: A Case Study of Chengdu Longquan Mountains Urban Forest Park. Forests 2025, 16, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121850

Ren Y, Lin L, Pan J, Feng Y, Yu C, Li T, Liu J, Guo Z, Zhang L. Cooling Effects in Large Urban Mountains: A Case Study of Chengdu Longquan Mountains Urban Forest Park. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121850

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Yuhang, Liang Lin, Junjie Pan, Yi Feng, Chao Yu, Tianyi Li, Jialin Liu, Zian Guo, and Lin Zhang. 2025. "Cooling Effects in Large Urban Mountains: A Case Study of Chengdu Longquan Mountains Urban Forest Park" Forests 16, no. 12: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121850

APA StyleRen, Y., Lin, L., Pan, J., Feng, Y., Yu, C., Li, T., Liu, J., Guo, Z., & Zhang, L. (2025). Cooling Effects in Large Urban Mountains: A Case Study of Chengdu Longquan Mountains Urban Forest Park. Forests, 16(12), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121850