Abstract

Eucalyptus plantations have suffered severe damage from scarab grubs in recent years. To investigate the actual scarab species that damage Eucalyptus trees, continuous closed-net monitoring and monthly soil-digging surveys were conducted in Eucalyptus plantations in Lancang County, China, from 2024 to 2025. The primarily affected roots were covered with nylon mesh bags until the insects reached adulthood. A few adults were successfully collected from the damaged roots. The scarab species that infests Eucalyptus trees has been identified as Megistophylla grandicornis (Fairmaire, 1891). It exhibited a single generation annually in local Eucalyptus plantations. Adults emerge from late April to June, and larvae cause damage from July to November. Eucalyptus trees with severely damaged roots exhibit reduced growth vigor and are highly prone to windthrow and death, leading to substantial losses in forestry production. These preliminary results provide foundational data for recognizing Megistophylla grandicornis as a new root pest of Eucalyptus and establishing targeted larval-monitoring protocols in Eucalyptus plantations.

1. Introduction

The Eucalyptus spp. (Myrtales: Myrtaceae) plantations in Lancang County, Yunnan Province, China, cover a wide area, and the economic output significantly affects the profitability of the local forestry industry. In recent years, Eucalyptus plantations have suffered serious damage caused by scarabs. Damage was observed across all age classes, from two-month-old to mature stands. The larvae cluster together to feed on the roots of Eucalyptus trees. This weakens the growth of the Eucalyptus trees and eventually leads to their falling and death. This seriously affects the preservation rate and yield. Scarab chafer is a general term for the Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea. The larvae are usually called white grubs. Herbivorous chafers are important pests in agroforestry. Adults can congregate to feed on the above-ground parts of plants, consuming leaves, buds, and tender shoots, thereby affecting the growth of plants. Larvae feed on underground roots of various plants. Scarab larvae (white grubs) are recognized as significant root pests of agricultural and forestry crops. They are characterized by high species diversity, wide distribution, polyphagous feeding habits, cryptic soil-dwelling lifestyles, and complex life histories [1].

It is important to understand the primary species and their damage characteristics and actively adopt various control measures to mitigate this damage. This is crucial for promoting the healthy development of Eucalyptus plantations. Previous studies on the dominant scarab species that damage crops often employed methods such as soil excavation surveys and light trapping during the adult stage [2,3,4]. However, due to factors such as some scarab species being insensitive to light, exhibiting weak phototaxis, being diurnal, or having distinct feeding and oviposition behaviors in adults [5,6,7,8,9], the dominant adult species captured in light traps within monitoring plots may not correspond to the larval species responsible for root-feeding damage [3]. Sometimes, the species caught in light traps are neither the primary scarab species causing damage nor those with maximum harmfulness. Preliminary light monitoring revealed a rich diversity of scarab beetle species within the Eucalyptus plantations of the Lancang area. However, only a few species of scarab beetles pose a serious threat to Eucalyptus trees. It remains unclear which species are truly harmful.

Since August 2024, an investigation has been conducted on the scarab species responsible for the damage and their distinctive damage features in the dying and fallen Eucalyptus trees affected by white grubs in Nuozhadu Town, Lancang County, China. To identify the species of root-feeding scarabs that damage Eucalyptus roots, this study employed the closed-net monitoring method in the field for the first time. The monitoring commenced upon the discovery of harmful larvae on the roots, and persisted until the emergence of adults. Furthermore, plants such as Eucalyptus, along with adults, were co-raised in closed-net chambers. This setup enabled a closed-loop observation of the oviposition behavior of the adults and the developmental process of the larvae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Site

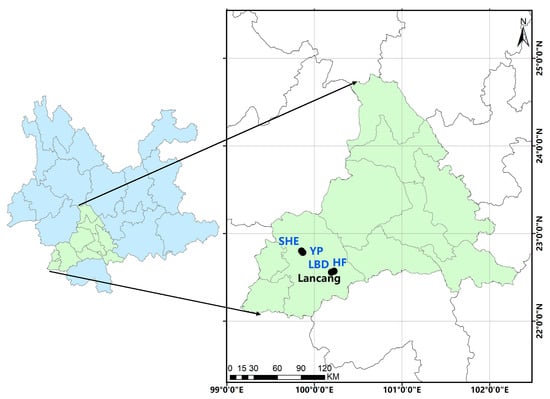

The present study was conducted from August 2024 to August 2025 in the Eucalyptus plantations of Lancang County (22°01′–23°16′ N, 99°29′–100°35′ E), situated in the southwestern part of Pu’er City, Yunnan Province, China. The study area has a mean annual temperature of 19.2 °C, an annual precipitation of 1624 mm [10]. The area features a subtropical mountain monsoon climate characterized by ample rainfall, abundant sunshine, mild winters, moderate summers, and well-defined dry and rainy seasons. The topography and geomorphology of the region are intricate, characterized by substantial altitude variations and a complex climate. The region supports diverse subtropical vegetation, including native shrubs and invasive understory species. Different representative Eucalyptus stands damaged by grubs were selected for continuous monitoring (Figure 1). The monitoring plots were situated at elevations ranging from 1500 to 1800 m a.s.l, featuring sandy loam soil (pH 4.5–4.9). The main cultivated clones in the Eucalyptus stands were locally adapted E. urophylla × E. grandis (DH3229) and E. grandis × E. urophylla (GL9), with stand ages ranging from 1 to 2 years. The main understory plants include Ageratina adenophora (Crofton weed), Betula alnoides (Southwest birch), Rubus pectinellus (Yellow raspberry), and so on. Four representative plots showing visible root damage were selected for continuous monitoring of scarab beetle activity.

Figure 1.

Scarab-monitoring site information in Eucalyptus stands Lancang County (LBD, SEH, YP and HF: monitoring plots).

2.2. Damage Survey

Soil-digging surveys in this study were initiated in August 2024. The surveys were conducted by manually digging with a hoe within a 1 m diameter range and 60 cm depth around dying plants, fallen plants, and residual stumps in the young Eucalyptus plantations during the last ten days of each month for one year. In each monitoring plot, soil-digging surveys were conducted to collect all the scarabs. A total of 30 sample trees were included. Additionally, any lodged plants found were also surveyed. Severe damage to the taproots and larger lateral roots of Eucalyptus was recorded. The insect stages, the number of individuals, and their distribution were recorded. Scarabs discovered through soil digging around the roots and closed-net monitoring were marked with the collection location, time, and numbers, and then taken back to the laboratory for further observation and research.

2.3. Indoor Rearing of Scarab Larvae

All live larvae collected from the damaged roots in the field plantations, except those monitored in closed nets, were brought back to the laboratory for rearing. Larvae were reared in a basement under conditions of 22 °C and 65% humidity. Each larva was placed individually in a 12 × 12 × 7.5 cm (length, width, height) rearing container. Sieved soil with a soil moisture content of 18% was used to fill each container to three-quarters of its volume. Fresh carrot slices were used as food [11]. Inspections were conducted weekly, dead insects were removed, and the carrots were replaced with fresh ones. This method has successfully reared a few (10%) scarab larvae to adulthood in preliminary trials. In this experiment, larvae collected from damaged Eucalyptus roots were also reared using this method, with a small quantity of Eucalyptus wood chips added [12].

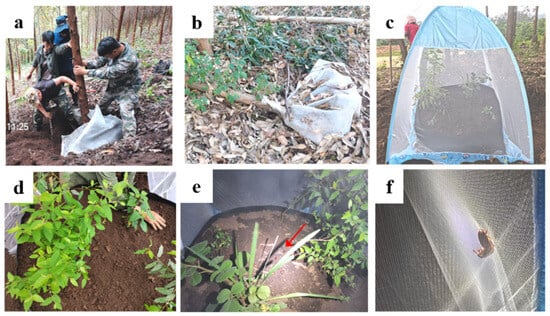

2.4. Outdoor Rearing of Adult Scarabs in Nylon Mesh Chamber

Adult scarab beetles were reared outdoors starting from late May at the Institute of Highland Forest Science, Chinese Academy of Forestry, located in Kunming. During the local summer in June, the average daily low temperature was 16 °C, while the average daily high temperature reached 25 °C. The monthly rainfall totaled 553 mm, and 23 days with precipitation [13]. Adults were reared in an outdoor nylon mesh chamber measuring 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.5 m in length, width, and height, with a 10 cm layer of sieved fine soil. Potted plants, including E. urophylla × E. grandis (DH3229), E. grandis × E. urophylla (GL9), B. alnoides, A. adenophora, and R. pectinellus collected from the wild understory were placed in the net cage (Figure 2a,b). Three pairs of adult males and females were selected from those collected from damaged roots and placed in 20 × 20 × 25 cm rearing containers. The containers were filled to half the volume with sieved moist soil. To prevent excessive rainfall in May and June from affecting the rearing of scarab beetles, a simple homemade rain-proof device made of plastic foam boards was constructed (Figure 2c). The rearing container was placed inside the nylon mesh cage. Three independent mesh cages were set up, each containing the same number of beetles and host plants. Inspections were conducted every two days to check for adult insects laying eggs. The eggs were collected and placed in a 12 × 12 × 7.5 cm rearing container for observation. Weekly checks were conducted to monitor egg hatching and larval development. Dead larvae and adults were immersed in 75% ethanol for microscopic examination. Two months after the adults died out, the soil in potted plants and mesh cages was inspected for the larvae.

Figure 2.

Rearing and monitoring of scarab adults in the nylon chamber. (a): Nylon chamber; (b): plants in the chamber; (c): rainproof plastic foam board.

2.5. Field Closed-Net Monitoring of Scarab Larvae

In two-year-old Eucalyptus stands in LBD, trees that exhibited lodging were inspected through closed-net monitoring. The monitoring site had an average monthly temperature of 21 °C and a mean monthly relative humidity of 72% from May to June. Lodged trees, whose above-ground portions were tilted or had fallen to the ground, with visibly fresh green foliage and whose roots were fully or partially exposed, were selected to confirm the presence of numerous larvae in the roots. Sharp machetes and chainsaws were used to quickly trim tree trunks above 2 m and roots above 1 m, minimizing soil and larvae disturbance around the roots. Preserve the original soil along with the roots to provide a habitat and food for the larvae. The roots, grubs, and soil were then enclosed within a 40-mesh nylon mesh (mesh size: approximately 400 μm; 2 × 2 × 2 m), which features durability and UV resistance, ensuring long-term stability during the enclosure period (Figure 3a,b). Given that natural larval mortality affects the success rate of obtaining adults, 10 additional root-feeding larvae excavated from the roots were added to the net bag. Secure the bag tightly with straps to prevent the scarabs from escaping. Repeat the above procedure for 5 plants at the LBD site. Inspections were carried out during the adults’ emergence period of the following year.

Figure 3.

Rearing and monitoring of scarabs in the Eucalyptus plantations field. (a): Pruning and netting of fresh fallen Eucalyptus tree; (b): status of roots after 5 months of nylon mesh-covered treatment; (c): closed-net monitoring chambers in the Eucalyptus plantations; (d): planting plants in closed-net chamber; (e): adults (indicated by red arrow) released into the net chamber; (f): mating adults in net chambers in May.

2.6. Field Monitoring of Scarab Adults in Closed-Net Chambers

During the adult stage in May, dead branches and fallen leaves in open areas within the Eucalyptus stands were cleared away, and the ground was leveled. An enclosed-net chamber was constructed using a Mongolian yurt mosquito net with dimensions of 2 × 1.8 × 1.5 m, with fully enclosed at the base and a T-shaped door. A non-woven fabric planting bag (1.28 m in diameter and 30 cm in height) was placed inside the net chamber. The bag was filled to two-thirds of its capacity with sifted soil to ensure that no other insects were present. Seedlings of several species, such as E. grandis × E. urophylla (GL9), B. alnoides, A. adenophora, R. pectinellus, and pre-cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea), were planted in the soil. These plants served as oviposition hosts, feeding sources and mimic natural understory vegetation. Ten adults, including two female adults previously collected from the damaged roots in the net bags, were introduced into the chamber. Additionally, 10 adults of the same species, collected via ultraviolet lamps at dusk, were added to the chamber. Observations of adult activities were initiated at 8:00 PM, and their mating behavior was confirmed (Figure 3c–f). This process was repeated in June. Two field net chambers were constructed at the LBD site. Monthly soil inspections were conducted to monitor the development of eggs and larvae.

2.7. Specimen Identification

The morphological characteristics of the scarab species specimens were examined using a ZEISS Stemi 508 stereomicroscope. The microscope was equipped with a TOUPCAM microscopic camera lens, and images were processed using ToupView software (version: C2CMOS12000KPA). The species were identified mainly based on the combination of larval epipharynx and male genitalia, referring to available specialized literature and books [14,15,16]. Additionally, relevant experts were consulted to assist in species identification. Specimens are deposited in the Insect Resource Research Laboratory, Institute of Highland Forest Science, Chinese Academy of Forestry.

3. Results

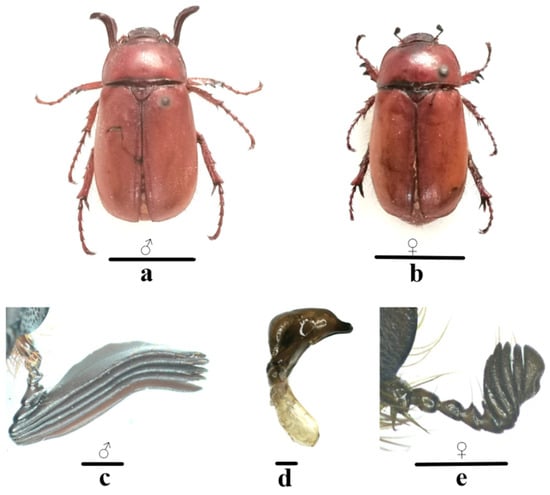

3.1. Identification

Scarabs discovered and collected from the roots of damaged Eucalyptus trees in several stands during 2024–2025 underwent morphological identification. The species identified was Megistophylla grandicornis (Fairmaire, 1891) (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The adult body is 21–26 mm long, 11–13 mm wide, oval, hairless and punctate dorsal surface, chestnut brown and shiny. Long, soft yellow setae are present on the ventral surface of the thorax. The sheath wings are not longitudinally ribbed, and the margins are folded with long cilia. The anterior margin of the clypeus is slightly concave with upturned edges, and there is a transverse ridge on the top of the head. The pronotum is transversely broad. The antennae consist of 10 segments, and the lamellate part (club) is composed of 5 segments, whose edges are equipped with short spinous hairs. In males, the lamellate part is long, large, flat, and curved outward (Figure 4c). In contrast, it is thick and short in females (Figure 4e). In addition to the noticeable differences in antennae, the legs of female adults are also slightly shorter than those of males. The phallobase of male genitalia is shorter than the parameres. The parameres exhibit a goose-head-like shape, with a central concave area in lateral view (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

The adult morphological characteristics of Megistophylla grandicornis. (a): Dorsal view of male adult; (b): dorsal view of female adult; (c): antennae of male adult; (d): lateral view of male genitalia; (e): antennae of female adult. Scale bars: 10 mm for (a,b); 1 mm for (c–e).

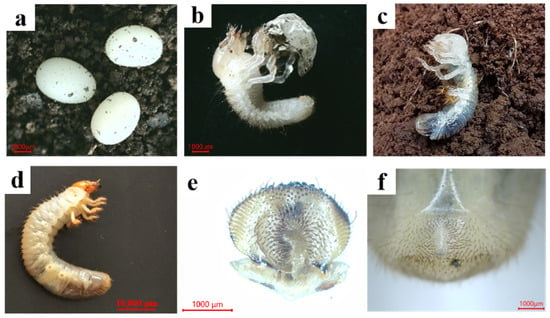

Figure 5.

Developmental stages and larval morphology of M. grandicornis. (a): Eggs; (b): first-instar larva (newly hatched larva with egg shell); (c): second-instar larva (newly molting larva with exuviate); (d): third-instar larva; (e): epipharynx; (f): raster.

3.2. Collection and Rearing of Scarabs

All second-instar and third-instar larvae were collected from roots in the field and brought back to the laboratory for rearing. However, they died within 2 months indoors. Under the outdoor nylon mesh chamber, the lifespan of adults is 15–20 days, and the adults lay eggs multiple times. The incubation period lasts 19–30 days, during which continuous hatching occurs. All first-instar larvae died within one month under indoor rearing conditions and no second-instar larvae were observed. Few second-instar larvae have been found in the outdoor chamber.

A total of 16 adults were collected from five trees, which had been sealed in bags since August and inspected in mid-May during root net monitoring. There are 4 female adults, with an average of 3 adults per tree. A total of 5 larvae, including one third-instar larva, were collected from two field enclosed-net chambers in mid-August, two months after the release of adults. The period from the collection of adults, adult egg-laying, to the emergence of third-instar larvae lasts approximately two months.

3.3. Field Fundamental Occurrence Patterns

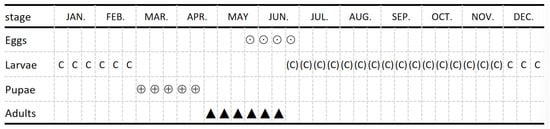

M. grandicornis pupation begins in early March. Adults are first observed in mid-April, and the peak incidence of adults occurs from late May to early June in field (Figure 6). No notches caused by the feeding of scarabs on Eucalyptus leaves were observed during the adult stage, whether in young Eucalyptus stands, field closed-net chambers, or outdoor mesh enclosures. Eggs and newly hatched larvae are seldom found in the soil, whereas second-instar larvae are sometimes observed in the shallow soil layer from June to July. From July to November, the third-instar larvae mainly gnawed on the large lateral roots and taproots voraciously, causing the wilting and even death of the trees during the peak larval period. In December, they gradually ceased feeding and entered a state of overwintering. The pupae and larvae remained within the infested Eucalyptus roots, specifically in oval-shaped earthen chambers. These chambers were constructed with wood chips and fine soil at the inwardly concave sites within the xylem of the injured roots.

Figure 6.

Occurrence and damage history of M. grandicornis in Eucalyptus plantations. (Key: ⊙: Egg; C: Larvae; (C): Damage-stage larvae; ⊕: Pupae; ▲: Adult.).

3.4. Hazardous Stage

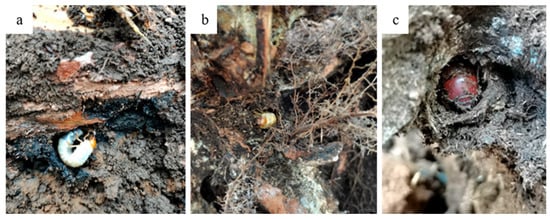

The early instar larvae are primarily found in the shallow soil layer, causing relatively minor damage to the trees, which is not easily detectable. The third-instar larvae mainly congregate beneath the large lateral roots and around the taproots in the deeper soil layer, below 20–30 cm, and feed on the roots. Most of the third-instar larvae, pupae, and adults were found near the root systems of severely damaged trees (Figure 7). The primary hazardous stage of Eucalyptus occurs during the third-instar larval stage.

Figure 7.

M. grandicornis on Eucalyptus roots: (a): Larvae on lateral roots; (b): larvae on taproots; (c): adult on roots.

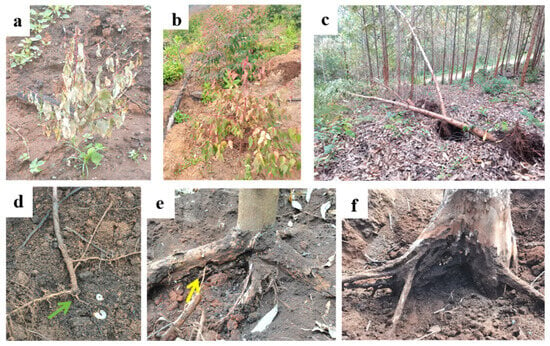

3.5. Damage Features

When the taproots and main lateral roots of a Eucalyptus plant were consumed by grubs, the above-ground portion, including the canopy branches and leaves, exhibited a sub-healthy state. The above-ground and underground damage features are shown in Figure 8. The leaves lose their green color, become sparse, and wither. The trees become weakened or even die. The Eucalyptus trees, having been victimized, were prone to wind damage and death after the strong winds during the rainy season, which lasts from August to November. Sometimes, the majority of the lateral roots and taproots of the toppled trees had been gnawed off. The damaged parts of lateral roots are mainly located 20–30 cm underground. Grubs gnaw beneath the lateral roots. In severe cases, they can nibble on the lateral roots until the roots break. The affected taproots are primarily located 20–60 cm underground, starting from the taproot’s periphery. In severe cases, the taproot may be completely gnawed off, exposing the xylem of the damaged roots. Commonly, numerous grooves arranged in a disorderly manner can be observed. Sometimes, the depth of the root damage can extend to 130 cm underground. Simultaneously, the common tissue color of wounds on the roots of Eucalyptus trees infested by grubs turns black, which is associated with the infection of pathogenic fungi and root lesions (Figure 7a).

Figure 8.

Damaged features of M. grandicornis larvae on Eucalyptus plants. (a): 2-month-old plants showing wilting; (b): 6-month-old plant showing discoloration and wilting; (c): collapsed damaged plants in 2-year-old stands; (d): the chewed taproots of the two-month-old tree (indicated by green arrow); (e): gnawed lateral roots of standing tree (indicated by yellow arrow); (f): severely gnawed stump.

4. Discussion

In this study, specimens were directly collected from the roots of damaged trees and reared within closed nylon mesh bags until the adults emerged. Monitoring of adult egg-laying and larval development was subsequently carried out in enclosed-net chambers to conduct a closed-loop survey of harmful scarab beetle species. The results of the survey study on scarabs identified that the actual species that damages Eucalyptus trees was M. grandicornis in the Nuozhadu area of Lancang County. This species was previously classified under the genus Hecatomnus, which is currently regarded as a synonym of the genus Megistophylla. The male adult morphological characteristics are consistent with those described in previous studies [14,17]. The species has been reported to be distributed across various regions in China, including Zhejiang, Hubei, Jiangxi, Hunan, Fujian, Guangxi, Chongqing, Guizhou, and Yunnan [14].

This result differs from the scarab species reported by previous researchers as being harmful to Eucalyptus trees. In the Leizhou Peninsula in Guangdong, adults of Anomala cupripes fed on Eucalyptus leaves and tender shoots, while their larvae consumed the root systems of young trees [18]. In the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, the scarab beetle Euetheola humilis damaged the basal bark and roots of young E. saligna trees [19]. In Australia, Eucalyptus trees are particularly affected by species such as Anoplognathus spp., Automolius spp., Heteronychus spp., Heteronyx spp. and Liparetrus spp., which cause a substantial amount of leaf loss. Heteronychus arator was regarded as the most damaging scarab species in young Eucalyptus plantations [8]. A. chloropyrus extensively chewed on the leaves of E. grandis and E. dunnii [20]. On the island of North Sumatra, Indonesia, the larvae of Exopholis hypoleuca have caused damage to the roots of young Eucalyptus trees [12]. The young Eucalyptus forests in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, suffered severe damage from the larvae of Maladera sp. [21]. The species responsible for the most damage vary by region and can be significantly influenced by factors such as geographical conditions, climatic differences, crop species, and differences in their geographical sources [22]. Additionally, the feeding preferences of different species of scarab beetles also play a role [23].

The rearing of M. grandicornis larvae remains stunted at the first-instar stage under laboratory conditions. The developmental progression from the first-instar to the second-instar cannot be observed yet. However, some adults can be successfully obtained from the roots that are infested and enclosed in net bags in the field. Monitoring in understory net chambers also successfully yielded some second-instar and third-instar larvae. Compared to the simplified and controlled indoor conditions, the complex field environment, including ground vegetation, climatic conditions, and micro-soil environments, proved relatively favorable for the development of scarabs. Larvae collected from the roots in field have difficulty surviving when transferred to indoor rearing. This may be due to issues related to environmental adaptation and dietary change, which requires further research.

M. grandicornis is a native species recorded in Yunnan. It has been found in Kunming City (Fumin County, Luquan County, Anning County), Yuxi City, and Gejiu City [16,24]. It can harm many tree species. The larvae feed voraciously on the roots of chestnut trees from March to April in Fumin and Luquan Counties. A peak in chestnut tree mortality occurred from April to May. Compared to chestnut plantations, the peak damage caused by M. grandicornis larvae in Eucalyptus plantations mainly occurs from July to November. During this period, a large number of Eucalyptus trees die or fall, and this is the peak period for the larvae. Heavy rainfall occurs during the rainy season, which lasts from June to August. This period marks the primary planting season for Eucalyptus trees in Lancang. Shortly after being planted, young trees suffered feeding damage from third-instar larvae. Affected trees emerged successively, starting from the second month after planting. The combined effects of loose soil and wind cause affected Eucalyptus trees to lose effective support, making them prone to lodging and dying. The outbreak periods of this scarab vary among stands in different regions and across different plant species. Both in chestnut and Eucalyptus plantations, severe infestations have been observed in large-scale monoculture stands. These are always characterized by relatively low biodiversity and a scarcity of natural enemies [25]. Once a pest successfully establishes in the stands, it tends to spread rapidly and cause substantial damage [26]. Before the extensive damage starts in July, it is recommended to implement preventive pest-control measures during the initial establishment of new plantations to reduce the infestation risk for young seedlings. Trees are most vulnerable to scarab attacks within the first 12 months after planting [27]. During the high-risk period from July to November, continuous monitoring of pest populations is essential, and corresponding control measures should be adopted.

M. grandicornis damages Eucalyptus roots during its larval stage. So far, no feeding on Eucalyptus leaves by adults has been observed in the monitoring plots. This may be related to certain unique physical and chemical properties of the leaves of some Eucalyptus varieties [9], as well as the content of insect-resistant substances such as 1,8-cineole and α-pinene [28]. The clones planted in the monitoring plots are E. grandis × E. urophylla and E. urophylla × E. grandis, whose roots have been severely gnawed by larvae. It remains unclear whether the severity of feeding damage caused by M. grandicornis varies among different Eucalyptus clones. Follow-up feeding tests are being conducted using various Eucalyptus roots to determine their feeding preferences. Previous observations indicate that the dominant leaf-feeding scarab species that harm Eucalyptus stands may change over the years [20]. During the initial phase of light trap monitoring, the dominant species of scarab beetles attracted at the same location changed between the two consecutive years. The monitoring period in this study was limited. Ongoing closed-net monitoring is being carried out. Subsequent monitoring results are anticipated to further clarify whether the dominant harmful root-feeding species affecting local Eucalyptus plantations will change or shift with the adjustment of adapted clones.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted preliminary surveys of root-feeding pests in Eucalyptus plantations in Lancang County, Yunnan Province, China, with a focus on M. grandicornis larvae. The identity of the species and its damage features were clarified, laying a foundation for future targeted monitoring and control of this pest in Eucalyptus stands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and L.S.; methodology, X.H. and T.D.; investigation, X.H., T.D. and W.W.; data curation, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, X.H., T.D., L.S., W.W. and Y.L.; project administration, L.S. and T.D.; funding acquisition, L.S. and T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Technologies for Controlling Scarab Beetles in Eucalyptus Plantations; the Science and Technology Department of Yunnan Province (202449CE340005); and the Key Technologies for Green and Efficient Control of Important Forest Pests in Coniferous Plantations (202302AE090017).

Data Availability Statement

All images in the text were made by the authors. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chen Bin from Yunnan Agricultural University for his valuable suggestions regarding the processing of scarab beetle samples, and Gao Chuanbu from the Institute of Zoology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, for his assistance in the morphological identification of scarab beetle species. The authors also acknowledge Li Yunfei, Li Haibo, and Yan Qiang et al. from Simao Jinlanchang High-Yield Forestry Co., Ltd. for their assistance in collection of scarabs’ specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

This study was funded by Sinar Mas Group. The first author, Dr. Huang Xiaohong, is a doctoral candidate jointly supervised by a subsidiary of Sinar Mas Group and the Chinese Academy of Forestry. The institutional affiliation has been approved by the company, and there are no conflicts of interest related to this paper. The authors independently conducted the research design, data analysis, and conclusion drafting, and the company did not interfere in the academic process.

References

- Liu, G.R. Color Atlas of Common Scarab Beetles in Northern China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1997; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.H.; Long, X.Z.; Zeng, X.R.; Wei, D.W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zeng, T. Preliminary investigation of scarabs species on upland crops and the population dynamics in Guangxi. Plant Prot. 2014, 40, 150–153, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Song, Z.Q.; Men, X.Y.; Cui, H.Y.; Li, L.L.; Song, Y.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, W.X. Species Investigation of Grubs in Honeysuckle Fields in Pingyi, Shandong Province. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2023, 55, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Yang, B.Y.; Yang, H.Q.; Yan, C.J.P.; Cao, H.Y.; Wang, G.; He, Y.Y.; Chen, B.; Du, G.Z. Investigation of scarab species on upland crops and population dynamics in Lancang area of Yunnan province. Plant Prot. 2025, 51, 233–239, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, L.; Fan, Z.Y.; Shen, H.L.; Liu, D.; Li, L.L.; Wang, W.H.; Li, S.M. The Luring Effect of Trap Lamp on the Population of Scarab Beetles. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2021, 62, 1374–1377, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, F.; Hai, X.X.; Fan, F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, S. The phototactic behavior of oriental brown chafer Serica orientalis to different monochromatic lights and light intensities. J. Plant Prot. 2016, 43, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.H.; Qu, M.J.; Chen, H.L.; Zhang, G.L.; Su, W.H. Population dynamics of three common peanut scarabs by light trapping in Anhui Province. J. Environ. Entomol. 2015, 37, 955–961. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer, M.J.; Weir, T.A. Summer activity patterns of nocturnal Scarabaeoidea (Coleoptera) of the southern tablelands of New South Wales. Aust. J. Entomol. 2007, 46, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhoff, E.; Blum, R.; Delb, H. Spring phenology of cockchafers, Melolontha spp. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), in forests of south-western Germany: Results of a 3-year survey on adult emergence, swarming flights, and oogenesis from 2009 to 2011. J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Lancang. Available online: https://www.lancang.gov.cn/info/6977/740892.htm (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- González-Chang, M.; Glare, T.; Lefort, M.-C.; Postic, E.; Wratten, S. An improved method to produce adults of Costelytra zealandica White (Coleoptera: Melolonthinae) from field-collected larvae. Wētā 2017, 51, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pasaribu, I.; Sunarko, H.; Abad, J.I.M.; Kkadan, S.K.; Tavares, W.; Durán, Á. First Report of White Grub Exopholis hypoleuca Wiedemann (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) on Eucalyptus spp. (Myrtaceae) Plantations. In Proceedings of the International Conference and the 10th Congress of the Entomological Society of Indonesia, ICCESI 2019, Bali, Indonesia, 6–9 October 2019; Atlantis Press: Kuta, Bali, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Historical Weather for Kunming City in June 2025. Available online: http://www.ynweather.com/kunming/history202506.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gao, C.B.; Li, C.L.; Fang, H. Megistophylla octobracchia gao & Li, new species (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Melolonthinae) from yunnan, China, and redescription of M. grandicornis (fairmaire, 1891). Zootaxa 2019, 4565, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L. Economic Insect Fauna of China, Vol. 28: Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea (Larvae); Science Press: Beijing, China, 1984; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Forestry Department. Forest Insects of Yunnan; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 1987; pp. 554–556. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Wen, L.Z.; Chen, K. Identification of common scarabaeid occurrence in tobacco fields in Hunan Province, China (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae). Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2012, 28, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, S.H.; Yu, Y.; Liang, X.M.; Ou, S. Preliminary study on comprehensive control of Anomala cupripes in Eucalyptus plantations. Eucalypt Sci. Technol. 2002, 19, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, O.; Garcia, M.S.; Cunha, U.S.D.; Back, E.C.; Bernardi, D.; Ramiro, G.A.; Finkenauer, E. Ocorrência de Euetheola humilis (Burmeister) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) em Eucalyptus saligna Smith (Myrtaceae), no Rio Grande do Sul. Neotrop. Entomol. 2008, 37, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carne, P.B.; Greaves, R.T.G.; McInnes, R.S. Insect damage to plantation-grown eucalypts in north coastal New South Wales, with particular reference to Christmas beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Aust. J. Entomol. 1974, 13, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri-Molina, D.; Govender, P. The impact of white grub (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) damage on growth of Eucalyptus grandis and Acacia mearnsii plantation trees in South Africa. Aust. For. 2022, 85, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.B.; Farrow, R.A.; Matsuki, M. Variation in insect damage and growth in Eucalyptus globulus. Agric. For. Entomol. 2002, 4, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, C.V.; Stone, C.; Hughes, L. Feeding preferences of the Christmas beetle Anoplognathus chloropyrus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) and four paropsine species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on selected Eucalyptus grandis clonal foliage. Aust. For. 2004, 67, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, X.M.; Chen, S.Q.; Shen, C.M.; Cui, J.; Hu, B.; Yu, W.H.; Dong, Z.G.; Huang, J.L. Damage feature and adult occurrence of Hecatomnus grandicornis in chestnut growing areas of Kunming City. J. West China For. Sci. 2010, 39, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.M.A.; da Silva, P.G.; Puker, A.; Ad’Vincula, H.L. Exotic pastureland is better than Eucalyptus monoculture: β-Diversity responses of flower chafer beetles to Brazilian Atlantic Forest conversion. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2021, 41, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, R.M.; Campelo, F.T.; Corassa, J.D.N. Infestation levels of the defoliator Glena unipennaria (Guenée, 1857) (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) in eucalyptus production systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 94, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, M.; Patel, V. Effect of imidacloprid on the growth of Eucalyptus nitens seedlings. Aust. For. 2003, 66, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.B.; Wanjura, W.J.; Brown, W.V. Selective herbivory by Christmas beetles in response to intraspecific variation in Eucalyptus terpenoids. Oecologia 1993, 95, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).