Novel Tomicus yunnanensis (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) Attractants Utilizing Dynamic Release of Catalytically Oxidized α-Pinene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Source of Test Insects

2.1.2. Experimental Materials and Apparatus

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation Method of Ti-Cu-SSZ-13 Catalyst

- (1)

- Titanium dioxide solid was mixed with concentrated hydrochloric acid and deionized water, followed by stirring until a homogeneous slurry was obtained, thereby preparing the titanium dioxide solution.

- (2)

- A mixture containing the titanium dioxide solution from step (1) and a citric acid solution was prepared. The powdered molecular sieve was added to this mixture for impregnation, followed by drying and calcination in a muffle furnace to obtain the catalyst powder.

- (3)

- The catalyst powder was then shaped, dried, and calcined to produce the final formed catalyst.

2.2.2. Preparation Method of New Attractant

- System with catalyst and heating: α-pinene + H2O2 + solvent + catalyst, reacted at 40 °C.

- System without catalyst but with heating: α-pinene + H2O2 + solvent, reacted at 40 °C.

- System without catalyst and without heating (background control): α-pinene + H2O2 + solvent, reacted at room temperature (approximately 25 °C).

2.2.3. New Attractant Trapping Test Method

2.2.4. Detection of New Attractant Reaction System

2.2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

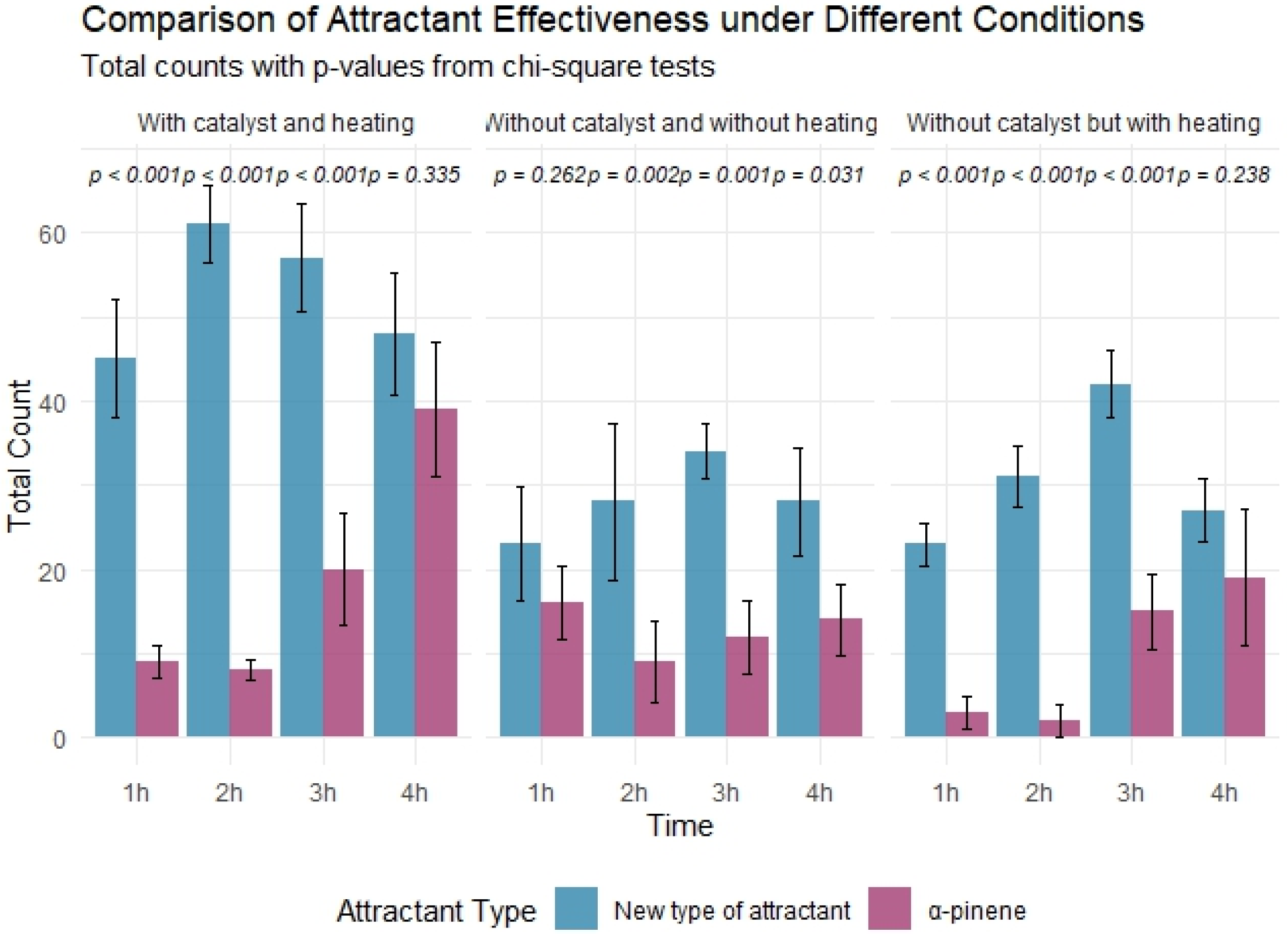

3.1. Trapping Results and Analysis of T. yunnanensis for the Three Reaction Systems

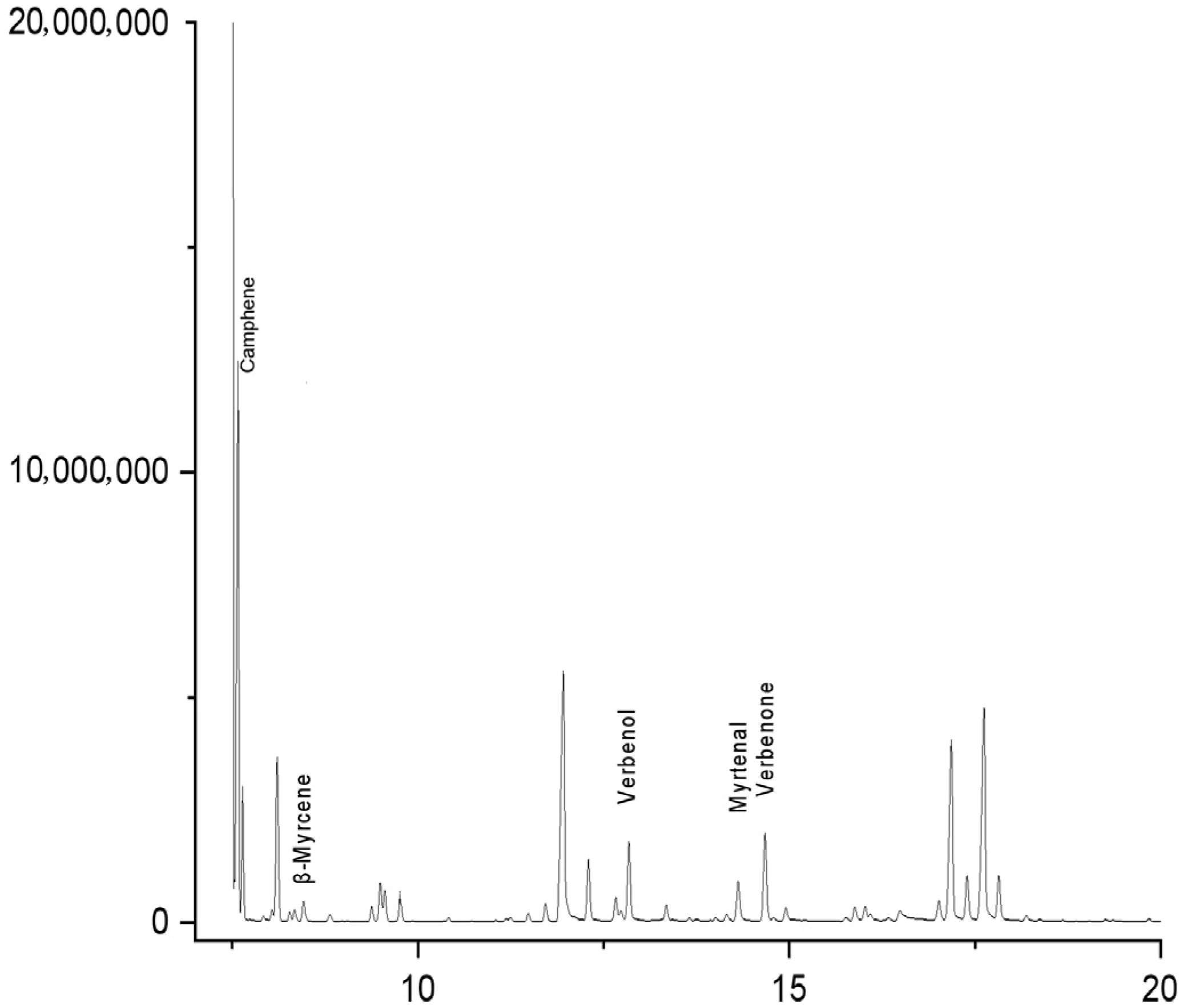

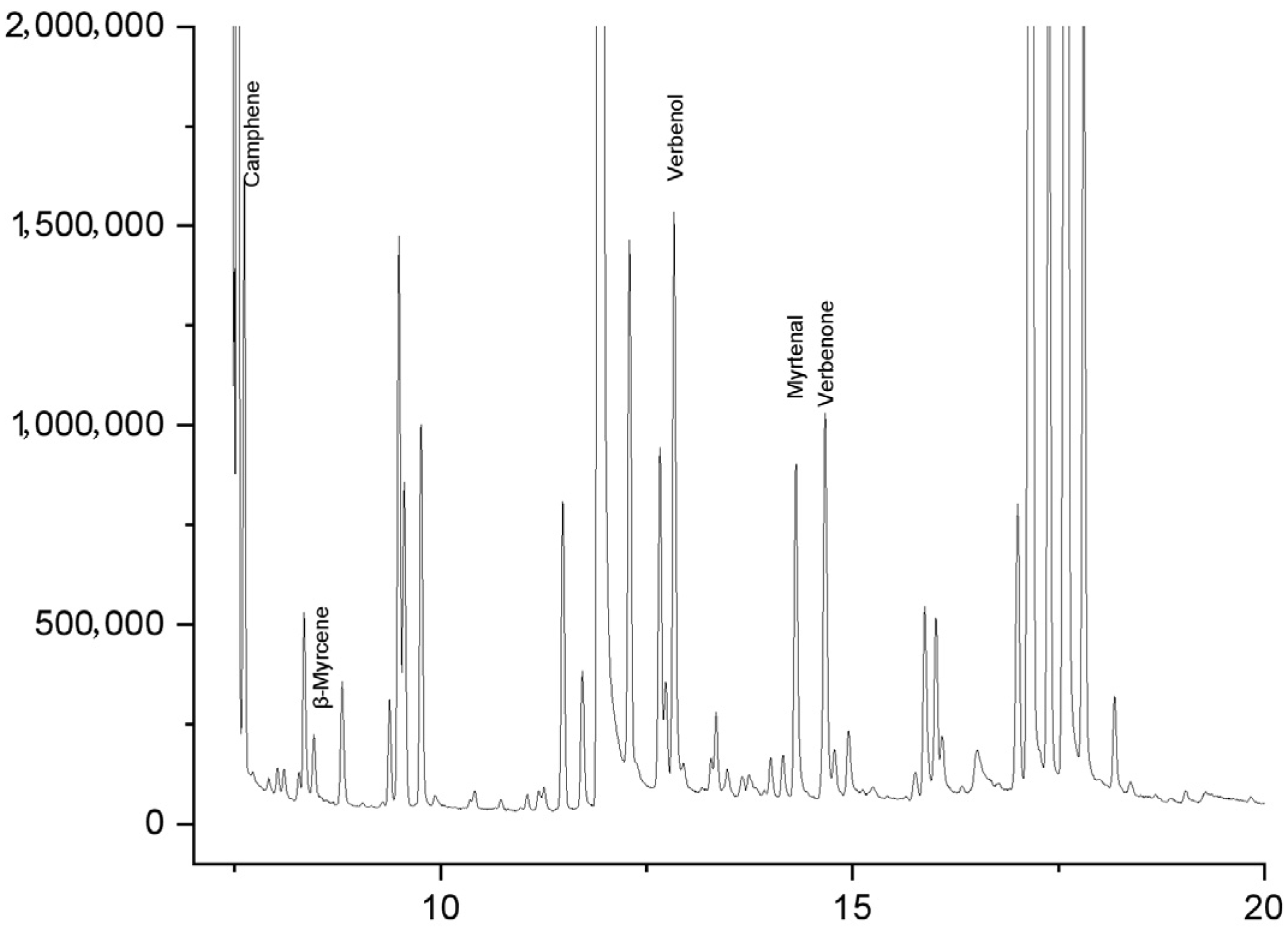

3.2. Results and Analysis of New Attractant Reaction System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wood, S.L.; Bright, D.E. A catalog of Scolytidae and Platypodidae (Coleoptera), Part 2: Taxonomic Index. Great Basin Nat. Mem. 1992, 13, 1833. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Kerdelhué, C.; Ye, H.; Lieutier, F. Genetic study of the forest pest Tomicus piniperda (Col., Scolytinae) in Yunnan province (China) compared to Europe: New insights for the systematics and evolution of the genus Tomicus. Heredity 2004, 93, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall, L.R.; Faccoli, M.; Ye, H. Description of the Yunnan shoot borer, Tomicus yunnanensis Kirkendall & Faccoli sp n. (Curculionidae, Scolytinae), an unusually aggressive pine shoot beetle from southern China, with a key to the species of Tomicus. Zootaxa 2008, 1819, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.; Skrzecz, I. Ecological segregation of bark beetle (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Scolytinae) infested Scots pine. Ecol. Res. 2016, 31, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Liu, H. Techniques of clearing Tomicus piniperda damaged woods in Pinus yunnanensis stands. Yunnan For. Sci. Technol. 2000, 2, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gitau, C.W.; Bashford, R.; Carnegie, A.J.; Gurr, G.M. A review of semiochemicals associated with bark beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) pests of coniferous trees: A focus on beetle interactions with other pests and their associates. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 297, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H. Tomicus yunnanensis; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, F.; Gurr, G.M.; Carnegie, A.J.; Bedding, R.A.; Bashford, R.; Gitau, C.W. Biology of the bark beetle Ips grandicollis Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) and its arthropod, nematode and microbial associates: A review of management opportunities for Australia. Austral Entomol. 2014, 53, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braquehais, F. Trap trees as an integral part of the control of beetle pests. Bol. Estac. Cent. Ecol. 1973, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Suckling, D.M.; Wearing, C.H.; Byers, J.A. Potential of mass trapping for long-term pest management and eradication of invasive species. J. Econ. Entomol. 2006, 99, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E.M.; Bentz, B.J.; Munson, A.S.; Vandygriff, J.C.; Turner, D.L. Evaluation of funnel traps for estimating tree mortality and associated population phase of spruce beetle in Utah. Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 36, 2574–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebe, C.; Blaženec, M.; Jakuš, R.; Unelius, C.R.; Schlyter, F. Semiochemical diversity diverts bark beetle attacks from Norway spruce edges. J. Appl. Entomol. 2011, 135, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, B.L. Host-related responses and their suppression: Some behavioral considerations. In Chemical Control of Insect Behavior: Theory and Application; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. Advances in insect pheromone research and application in China. Insect Knowl. 2000, 2, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, G. Prospects of new semiochemicals and technologies. In Application of Semiochemical for Management of Bark Beetle infestations, Proceedings of an Informal Conference: Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 12–16 December 1993; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1995; pp. 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.G.; Xuan, W.J.; Sheng, C.F. Research progress on the application of sex pheromones in pest monitoring and forecasting. Plant Prot. 2006, 32, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.H.; Yuan, Z.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Gao, C.Q.; Wang, H.K. Preliminary report on field trapping effects of semiochemicals on Tomicus minor. For. Pest Dis. 2007, 26, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.S.; Shu, N.B.; Huai, K.Y.; Zhu, X.; Jin, H. Attraction experiments of several compounds to Tomicus piniperda. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 1993, 3, 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Li, L.S.; Jiang, Z.L.; Liu, H.P.; Huai, K.Y.; Shu, N.B. Studies on the aggregation pheromone of Tomicus piniperda in Pinus yunnanensis. Yunnan For. Sci. Technol. 1997, 2, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.X.; Gao, Z.L.; Lyu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, H.; Liu, F.C. Taxis test of Tomicus piniperda to extracts of Pinus yunnanensis twigs. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 2002, 5, 384–386. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.C.; Wang, H.B.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, Y.J. Research progress on monitoring and controlling Tomicus piniperda using volatile chemicals from Pinus yunnanensis. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2008, 2, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.L.; Ma, H.F.; Ze, S.Z. Differential response of Tomicus yunnanensis to volatiles from trunk and twig of Pinus yunnanensis. J. Environ. Entomol. 2011, 33, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.; Zhang, M.D.; Qian, L.B.; Ze, S.Z.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.B. Electroantennographic and behavioral responses of Tomicus yunnanensis to volatiles from initially infested Pinus yunnanensis. J. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 43, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.J.; Yan, G.; Li, Z.B. Composition and stage-specific variations of semiochemical substances in Tomicus yunnanensis. J. West. For. Sci. 2024, 53, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.D.; Pierce, H.D.; Borden, J.H. Host compounds as kairomones for the western balsam bark beetle Dryocoetes confusus Sw. (Col., Scolytidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 1998, 122, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-H.; Clarke, S.R.; Kang, L.; Wang, H.-B. Field trials of potential attractants and inhibitors for pine shoot beetles in the Yunnan province, China. Ann. For. Sci. 2005, 62, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Y. Studies on semiochemicals of three Tomicus species infesting Pinus yunnanensis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S.F.; Kong, X.B.; Zhang, Z. Semiochemical regulation of the intraspecific and interspecific behavior of Tomicus yunnanensis and Tomicus minor during the shoot-feeding phase. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H. Studies on Chemical Ecological Relationships of Three Tomicus Species. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Reaction System | Time | χ2 | df | p-Value | Significance (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With catalyst and heating | 1 h | 24.00 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant |

| 2 h | 40.71 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant | |

| 3 h | 17.78 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant | |

| 4 h | 0.93 | 1 | 0.335 | Non-significant | |

| Without catalyst but with heating | 1 h | 15.39 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant |

| 2 h | 25.49 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant | |

| 3 h | 12.79 | 1 | <0.001 | Significant | |

| 4 h | 1.39 | 1 | 0.238 | Non-significant | |

| Without catalyst and without heating | 1 h | 1.26 | 1 | 0.262 | Non-significant |

| 2 h | 9.76 | 1 | 0.002 | Significant | |

| 3 h | 10.52 | 1 | 0.001 | Significant | |

| 4 h | 4.67 | 1 | 0.031 | Significant |

| Category | Compound Name | 1 h Attractant | 2 h Attractant | 3 h Attractant | 4 h Attractant | RT/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene Hydrocarbons | camphene | 46.55 | 53.06 | 45.14 | 37.10 | 7.58 |

| β-pinene | 12.93 | 9.75 | 9.72 | 10.41 | 8.1 | |

| D-limonene | 3.45 | 2.72 | 2.59 | 2.94 | 9.49 | |

| (E)-3,7-dimethylocta-1,3,6-triene | 2.30 | 1.81 | 1.73 | 2.04 | 9.77 | |

| β-myrcene | 2.01 | 1.36 | 1.51 | 1.58 | 8.47 | |

| α-phellandrene | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 8.82 | |

| p-isopropyltoluene | 0.86 | 0.91 | 1.30 | 1.36 | 9.38 | |

| α-terpinene | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 14.16 | |

| Oxygenated Monoterpenes | verbenone | 6.90 | 6.80 | 7.78 | 8.37 | 14.67 |

| verbenol | 6.03 | 6.12 | 7.78 | 9.73 | 12.84 | |

| myrtenal | 3.74 | 3.40 | 4.10 | 4.75 | 14.31 | |

| campholenic aldehyde | 3.16 | 4.08 | 6.48 | 7.69 | 12.3 | |

| cineole | 2.87 | 2.04 | 2.16 | 2.26 | 9.56 | |

| (-)-trans-pinocarveol | 2.01 | 1.81 | 2.16 | 2.49 | 12.66 | |

| (±)-2(10)-pinen-3-one | 1.44 | 1.36 | 1.51 | 1.58 | 13.34 | |

| α-pinene oxide | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 1.13 | 11.49 | |

| carveol | 0.86 | 1.13 | 1.51 | 1.8 | 15.88 | |

| 2-cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-, (1R,5S)-rel- | 0.57 | 0.23 | 1.51 | 1.58 | 14.95 |

| Category | Compound Name | 1 h Attractant | 2 h Attractant | 3 h Attractant | 4 h Attractant | RT/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene Hydrocarbons | 1-ethenyl-5,5-dimethylbicyclo[2.1.1]hexane | 79.52 | 45.17 | 77.55 | 77.50 | 6.51 |

| camphene | 3.56 | 10.85 | 3.68 | 3.45 | 7.52 | |

| 4-methyl-1-(propan-2-yl)bicyclo[3.1.0]hex-2-ene | 1.65 | 5.01 | 1.84 | 1.60 | 6.72 | |

| D-limonene | 1.22 | 1.67 | 1.32 | 1.26 | 9.49 | |

| (E)-3,7-dimethylocta-1,3,6-triene | 0.87 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 9.77 | |

| α-phellandrene | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 8.8 | |

| β-myrcene | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 8.46 | |

| p-cymene | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 9.38 | |

| Oxygenated Monoterpenes | trans-verbenol | 2.17 | 5.01 | 1.67 | 1.94 | 12.84 |

| campholenic aldehyde | 1.13 | 4.73 | 1.93 | 2.11 | 12.29 | |

| α-pinene oxide | 1.04 | 1.67 | 0.79 | 1.18 | 11.49 | |

| verbenone | 0.95 | 3.06 | 1.23 | 1.18 | 14.67 | |

| myrtenol | 0.87 | 2.50 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 14.31 | |

| cineole | 0.78 | 1.95 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 9.56 | |

| (-)-trans-pinocarveol | 0.69 | 2.23 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 12.66 | |

| carveol | 0.35 | 1.11 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 15.88 | |

| cis-verbenol | 0.26 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 12.73 | |

| (±)-2(10)-pinen-3-one | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 13.34 | |

| (1R,5R)-rel-2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-2-cyclohexen-1-ol | 0.17 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 14.95 | |

| 2,6,6-trimethyl-(1α,2α,5α)-norpinan-3-one | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 13.29 | |

| isoborneol | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 14.01 | |

| α-terpineol | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 14.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Feng, D.; Li, H.; Chen, P.; Zhao, G. Novel Tomicus yunnanensis (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) Attractants Utilizing Dynamic Release of Catalytically Oxidized α-Pinene. Forests 2025, 16, 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121847

Wang M, Feng D, Li H, Chen P, Zhao G. Novel Tomicus yunnanensis (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) Attractants Utilizing Dynamic Release of Catalytically Oxidized α-Pinene. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121847

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Meiying, Dan Feng, Haoran Li, Peng Chen, and Genying Zhao. 2025. "Novel Tomicus yunnanensis (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) Attractants Utilizing Dynamic Release of Catalytically Oxidized α-Pinene" Forests 16, no. 12: 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121847

APA StyleWang, M., Feng, D., Li, H., Chen, P., & Zhao, G. (2025). Novel Tomicus yunnanensis (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) Attractants Utilizing Dynamic Release of Catalytically Oxidized α-Pinene. Forests, 16(12), 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121847