Abstract

Urban vegetation plays a role as a sink, but accurately estimating carbon storage requires cultivar-specific allometric equations due to variations in growth patterns. This study develops and compares carbon storage models for cultivars of Hibiscus syriacus L.: ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’, ranked first and second in preference in South Korea and most widely planted in urban areas, to address the lack of specific data for these popular varieties. We destructively sampled 106 trees from experimental nurseries in Korea, measuring growth parameters, partitioned biomass, and component-specific carbon content. A non-linear regression equation modeled the relationship between root collar diameter (RCD) and total carbon storage. RCD proved the most effective predictor, resulting in high-performance power-function models (R2 = 0.99) for both cultivars: ‘Wonhwa’ (CS = 0.02RCD2.41) and ‘Chilbo’ (CS = 0.01RCD2.38). An extra sum-of-squares F-test confirmed a statistically significant difference between the models (p < 0.001). Notably, both cultivars exhibited a branch-dominant allocation pattern (accounting for approximately 50–51% of total biomass), which contrasts significantly with the stem-dominant pattern typically observed in forest-grown trees. The observed inter-cultivar differences indicate that using a single species-level equation can yield inaccurate carbon estimates. Consequently, we recommend that urban managers apply these cultivar-specific equations rather than generic species-level models to minimize estimation uncertainty and support precise carbon inventory management.

1. Introduction

Climate change, evident in the rising frequency of droughts, wildfires, and floods, highlights the urgent need for effective carbon sinks. Many countries are creating sustainable carbon sinks, such as gardens and urban forests, in populated areas to reduce greenhouse gases, the primary driver of climate change [1,2,3,4]. The Republic of Korea is also increasing green spaces within urban environments to meet its climate goals [5]. To accurately evaluate the carbon sequestration potential of trees in these areas [6], it is essential to develop species-specific allometric equations [7,8,9,10,11]. Allometric equations are statistical models that estimate tree biomass and carbon storage based on easily measurable tree variables, such as diameter and height, grounded in the biological principle that tree dimensions are proportionally related throughout their growth [12]. Since direct measurement of a tree’s total biomass is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and impractical for large-scale assessments, allometric equations are favored for their convenience and efficiency [8,13,14].

However, the application of these equations requires careful consideration, as using general or forest-based models for urban trees can yield inaccurate results. Urban environments possess unique characteristics that significantly impact tree morphology and physiology [15,16]. Models designed for trees in natural forest settings often produce substantial errors when applied to urban trees, previous studies indicating that forest-based models can produce substantial errors, often leading to biomass overestimations ranging from 60% to over 300% when applied to urban trees [17,18]. This discrepancy arises from the distinct environmental pressures faced by urban trees, including intensive management practices (such as pruning), altered soil conditions from compaction and sealing, and changes in light availability [19,20,21,22]. These factors greatly affect their architecture and biomass allocation compared to forest trees. Additionally, recent research has shown that frequent pruning can reduce a tree’s potential carbon storage by as much as 30% over its lifespan, highlighting a critical variable often overlooked in general models [23,24]. Consequently, the development of urban-specific and even species-specific models is essential for accurate carbon accounting [8,10,11,25,26].

Biomass allocation is affected by both environmental factors and the genetic traits of the plant [23,27]. Even within a single species, there can be considerable differences in growth and biomass distribution due to variations in stand age or geographical origin [23,28]. Some species with a broad range of genetic diversity show varying patterns of biomass distribution [23,29,30]. This intraspecific variation is especially evident in horticulturally developed plants [30], where cultivars are artificially selected for particular aesthetic or functional traits, resulting in distinct growth forms [29,31].

The Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus L.), Korea’s national flower, is a woody plant belonging to the Malvaceae family. Its attractive flowers and extended blooming period make it a popular ornamental tree in urban settings [29,32]. Since the 1960s, active development of new cultivars has resulted in approximately 300 varieties [33,34,35]. These cultivars display a range of growth forms, from multi-stemmed shrubs to taller, single-stemmed trees [34]. Despite their widespread use in urban landscapes, there is a lack of empirically derived allometric models for this species and its various cultivars, creating a significant data gap in urban carbon inventories [5,8,15,29]. This gap complicates accurate assessments of urban greening and the valuation of ecosystem services provided by specific plant selections [8,15,16,36,37,38].

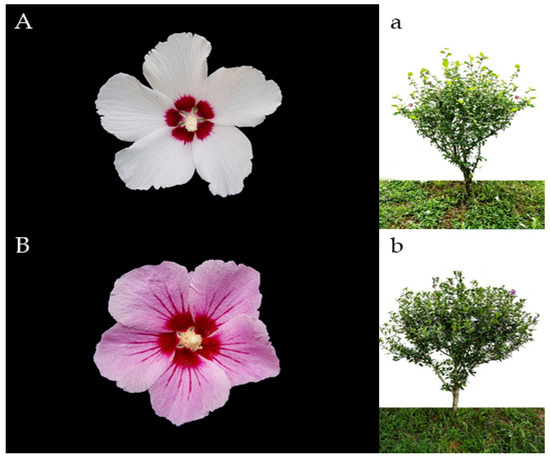

This study aims to develop and compare allometric equations for estimating carbon storage in the major Hibiscus syriacus cultivars ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo.’ Both cultivars were developed by the National Institute of Forest Science in 1990 and are the most widely used due to their high ornamental value and substantial flowering volume. The two cultivars exhibit differences in tree form and growth patterns: ‘Wonhwa’ has a somewhat upright form with thick branches, while ‘Chilbo’ has a more open shape and slightly drooping branches (Appendix A Figure A1 and Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3). The two cultivars exhibit distinct growth characteristics; ‘Wonhwa’ shows a rapid vertical growth strategy with a mean annual shoot growth of 59 cm, which is approximately 40% higher than the 42 cm observed in ‘Chilbo’ (Table A2). Furthermore, ‘Wonhwa’ possesses nearly twice number of leaves per branch (Mean: 14.7) compared to ‘Chilbo’ (Mean: 7.7), resulting in a significantly denser canopy structure (Table A2).

Considering the morphological differences between the erect ‘Wonhwa’ and spreading ‘Chilbo’, and recognizing that RCD has been identified as a higher predictor for determining the biomass of shrubs and small trees compared to DBH or height [39,40,41], we hypothesized that (1) significant differences in biomass allocation patterns would exist between the two cultivars, and (2) root collar diameter (RCD) would serve as the most reliable predictor for estimating carbon storage in these cultivars. Therefore, this study will: (1) quantify and compare the distinct biomass allocation patterns of ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo,’ (2) determine their component-specific carbon content, and ultimately, (3) develop and statistically validate robust, cultivar-specific allometric equations to highlight the importance for such models in urban areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Materials

The plant materials used in this study were the Hibiscus syriacus cultivars ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’. A total of 106 individuals were harvested, comprising 51 ‘Wonhwa’ and 55 ‘Chilbo’, from nurseries in Sejong (36°40′42″ N, 127°12′12″ E) and Suwon (37°15′03″ N, 126°57′17″ E). The cultivars in Suwon were cultivated in a 0.3 ha field nursery, while those in Sejong were grown as pot-grown saplings. To ensure a representative dataset covering the full range of growth stages, we employed a stratified random sampling method based on root collar diameter (RCD) size classes. The cultivation history of the saplings varied by age group: the 3–9-year-old group included pot-grown saplings, while the 10–13-year-old group consisted of trees that were grown in a field nursery for approximately 10 years after being planted as 3-year-old rooted cuttings. To develop robust allometric equations applicable to a broad spectrum of tree sizes, it is essential to secure a dataset covering a wide range of diameter classes. Therefore, we employed a stratified random sampling method that included both pot-grown saplings and field-grown trees. This approach minimizes extrapolation errors and ensures the statistical validity of the regression models across the entire developmental spectrum of the cultivars, while also reflecting the typical planting stocks used in urban forestry. The sampled trees were grown freely with minimal artificial intervention, such as light pruning, and were selected for their healthy and vigorous condition, being free of diseases and pests. Detailed planting information and site characteristics for the sampled cultivars are provided in Table 1. To minimize variations in carbon content associated with different propagation methods in very young plants, individuals ranging in age from 3 to 13 years were included in the study. A statistically sufficient number of samples were collected and analyzed, covering a broad distribution of tree sizes necessary for developing regression models [9,10]. A summary of the morphometric measurements for the sampled trees can be found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of the study sites, including planting information and cultivation system for Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’.

Table 2.

Summary morphometric measurements for Hibiscus syriacus cultivars used for variable selection. Values for the individual cultivars (‘Wonhwa’, ‘Chilbo’) were averaged from trees of the same age range (3 to 13 years) for comparison, while the ‘Total’ column includes data from all ages.

2.2. Biomass and Carbon Content Analysis

To analyze biomass allocation, harvested trees were first separated into above- and below-ground portions by severing them at the root collar. The above-ground biomass was further fractionated based on organ type: leaves and twigs were manually stripped or separated using pruning shears, while branches were separated from the main stem using pruning shears and electric pruning shears. Roots were washed using high-pressure water spray to remove soil particles. This procedure followed standardized destructive sampling guides commonly used in biomass studies [15,23,42]. The samples were then placed in separate paper bags according to their component and dried in an oven (DH, WOF-L800, DAIHAN, Wonju-si, Republic of Korea) at 85 °C until they reached a constant weight. This drying process took approximately 7 days, although larger root samples required up to 10 days. The dry weight of each component was measured in grams (g) to two decimal places. Next, the dried samples were ground into fine particles (<2 mm) using a grinder. The carbon content of each component was analyzed using the dry combustion method with an elemental analyzer (Vario Macro Cube, Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany) at a combustion temperature of 1150 °C, a standard method for determining carbon concentration in plant tissues [9,43]. The carbon content measurements for each component were taken in triplicate, and the values were averaged. Preliminary analysis showed that the coefficient of variation (CV) for leaf area was approximately 24–25% for both cultivars. Given the natural variability of field-grown plants, this level indicates morphological consistency, suggesting that a sample size of 10 leaves is statistically sufficient to capture the representative mean.

Total carbon storage (CS) was calculated by summing the products of the dry weight and carbon fraction (CF) for each component:

The variables measured for developing allometric equations included root collar diameter (RCD), height, crown width, root width, root length, and leaf area. Morphometric measurements followed standard dendrometric protocols. Root collar diameter (RCD) was measured at the stem base (including bark) in two perpendicular directions using a Vernier caliper (NV500-DC150PRO, Navimro, Seoul, Republic of Korea), and the mean value was recorded. Plant height (H) was measured as the length from the root collar to the apical tip. Crown width (CW) and root width (RW) were determined by measuring two perpendicular axes (widest and narrowest) and calculating the average. All linear dimensions were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm, except for RCD, which was recorded to 0.01 mm. For leaf area, ten leaves were randomly sampled from each individual, and their area was measured using an image scanner (Perfection V700, Epson, Suwa, Japan) and image analysis software (Winseedle Pro 2020, Regent Instruments Inc., Quebec, QC, Canada); the values were then averaged.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

In this study, plant biomass was divided into four components: leaves and twigs, branches, stems, and roots. This approach was used to create reliable allometric equations that represent the growth characteristics of each cultivar.

To select the most suitable predictor variables for the allometric equations while avoiding multicollinearity, we employed a two-stage process. First, we conducted factor analysis to reduce the dimensionality of the growth variables by grouping them into underlying factors. Next, we performed a goodness-of-fit comparison using several machine learning algorithms (MRMR, RReliefF) and the statistical test (F-test) to identify the single most influential variable for the final model [44,45,46,47]. The goodness-of-fit comparison employed several established algorithms, including Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (MRMR), the F-test, and RReliefF. MRMR is a variable selection algorithm designed to identify predictors that exhibit a high correlation with the dependent variable while concurrently minimizing redundancy among the independent variables. The F-test evaluates the degree of correlation between independent and dependent variables. RReliefF assesses the relative importance of independent variables by measuring their efficacy in distinguishing between neighboring instances.

Factor analysis is a statistical technique for dimensionality reduction that uncovers common underlying factors among a set of independent variables. We excluded variables with a correlation coefficient below 0.5 as non-essential. For variable extraction, we used principal component analysis and applied the Varimax method for factor rotation, extracting factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.

With the selected variable, we tested various linear and non-linear model forms, including Robust Regression (RR). To assess the statistical significance of the two resulting equations, we conducted an extra sum-of-squares F-test (Chow test), a standard method for evaluating significant differences between nested regression models [8,48].

We tested four candidate model structures commonly used in dendrometric studies to identify the best fit for carbon storage estimation:

Among these, the power function is theoretically preferred in allometric studies as it describes the constant relative growth rate between two plant parts (scaling law) [42].

Additionally, we utilized Robust Regression (RR) in the model development process. RR is a method designed to be robust to outliers, thereby preventing them from disproportionately affecting the model and ensuring more stable regression coefficients. This is accomplished by assigning lower weights to outliers instead of removing them. We compared two RR algorithms to determine the optimal model. First, Least Absolute Residuals (LAR) minimizes the sum of absolute deviations, thereby reducing the influence of outliers unlike Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). Second, the Bisquare (Tukey’s bisquare) weighting function was evaluated, which minimizes the impact of extreme residuals by assigning them zero weight beyond a specified threshold.

The predictive performance of the developed models was evaluated using the Coefficient of Determination (R2), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The equations are as follows:

where, represents the observed value, is the predicted value, is the mean of the observed values, n is the total number of samples, RSS is the residual sum of squares, and k is the number of parameters in the model. The optimal models were selected based on the highest R2 and the lowest RMSE, AIC, and BIC values.

Separate non-linear regression analyses were conducted to develop allometric equations for each cultivar, ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo.’ To assess the statistical significance of the resulting equations, we performed an extra sum-of-squares F-test (Chow test), which compares the residual sum of squares from separate models (full model) to that of a single model (reduced model). This method is a standard approach for testing significant differences between nested regression models [42].

To explore the impact of cultivation environment on biomass allocation strategies, we calculated the root-shoot ratio (R), defined as the ratio of the dry weight of belowground biomass to that of aboveground biomass [23]. An independent samples t-test was conducted to statistically compare the mean R between the two cultivars, ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo.’ This analysis was carried out separately for each cultivation environment (younger pot-grown and older field-grown) to identify inherent, cultivar-specific allocation strategies under different conditions.

Model estimation, including the development of allometric equations, was performed using MATLAB R2025a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Statistical and factor analyses, including group comparisons, were conducted using SPSS Statistics Digital 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Biomass Allocation and Carbon Content

Table 3 compares the biomass allocation ratios of the two Hibiscus cultivars from this study—categorized by cultivar and cultivation environment (younger pot-grown and older field-grown)—with results from other studies on major landscape trees and shrubs. Across the entire age range, ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’ exhibited similar biomass distribution patterns, with both cultivars allocating the largest proportion of their biomass to branches (51% for ‘Wonhwa’ and 50% for ‘Chilbo’). This growth form distinctly sets them apart from typical trees and shrubs.

Table 3.

Biomass partitioning by plant part for various species: A comparison of the present study with literature data.

However, a closer examination by cultivation environment revealed subtle differences between the cultivars. In the younger pot-grown group, ‘Wonhwa’ allocated a larger share of its resources to branches (38.9%), while ‘Chilbo’ directed a greater proportion to roots (30.9%). As they transitioned to the field-grown group, both cultivars significantly increased their biomass allocation to branches (‘Wonhwa’ at 53.9% and ‘Chilbo’ at 51.8%), but ‘Wonhwa’ continued to prioritize branch growth. In contrast, ‘Chilbo’ consistently allocated a higher proportion of its biomass to roots throughout all growth stages compared to ‘Wonhwa’.

Table 4 presents the carbon content of each part of two Hibiscus cultivars. The average carbon content was 44.16% for ‘Wonhwa’ and 43.35% for ‘Chilbo’. In both cultivars, the carbon content was lowest in the leaves and twigs, approximately 40%, while the woody parts—such as branches, stems, and roots—exhibited higher carbon contents, around 44–45%. This pattern is consistent with general plant physiological characteristics, where photosynthetic tissues like leaves typically have lower carbon content compared to woody parts that are rich in lignin and cellulose [3,27,28].

Table 4.

Carbon content by plant parts for Hibiscus syriacus cultivar.

3.2. Variable Selection and Allometric Equation Development

Table 5 summarizes the variable importance analysis results for developing allometric equations. Machine learning algorithms consistently identified Root Collar Diameter (RCD) as the most effective single predictor of carbon storage. For the ‘Wonhwa’ cultivar, the F-Test ranked RCD highest with a score of 38.19, followed by root length at 36.13 and root width at 23.04. Similarly, for ‘Chilbo’, the F-Test identified RCD as the top predictor with a score of 53.75, followed by root length at 43.48 and height at 32.11. This indicates that RCD best represents the overall size of both the aboveground and belowground components for both cultivars. While multivariate models (e.g., combining RCD, H, and CW) exhibited slightly lower AIC and BIC values compared to the single-variable model (Table 6 and Table 7), the inclusion of additional variables introduced model complexity without yielding a proportional increase in practical predictive capability. Consequently, the single-variable RCD model was selected as the optimal estimator. This decision aligns with the results of our variable importance analysis (Table 5), confirming that RCD is the most statistically significant predictor for generating a robust and parsimonious model.

Table 5.

Variable selection for allometric equation models development: Results of variable importance and factor analysis for Hibiscus syriacus cultivars.

Table 6.

Comparison of fit statistics for candidate allometric equations estimating carbon storage of Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’.

Table 7.

Comparison of fit statistics for candidate allometric equations estimating carbon storage of Hibiscus syriacus ‘Chilbo’.

To quantitatively validate the model selection, we compared the fit statistics (R2, RMSE, AIC, BIC) of various candidate models using RCD, H, and CW as single or combined predictors (Table 6 and Table 7). The analysis confirmed that RCD-based power models consistently provided the most reliable single-variable predictions. For instance, in ‘Wonhwa’, the RCD power model achieved an R2 of 0.86, showing significantly higher values than the best Height-based model (R2 = 0.38). Similarly, for ‘Chilbo’, the RCD model (R2 = 0.91) demonstrated superior explanatory power compared to Height (R2 = 0.58) and Crown Width (R2 = 0.85). Although multi-variable models (e.g., combining RCD, H, and CW) yielded marginal improvements in R2, the single-variable RCD model was selected as the final estimator.

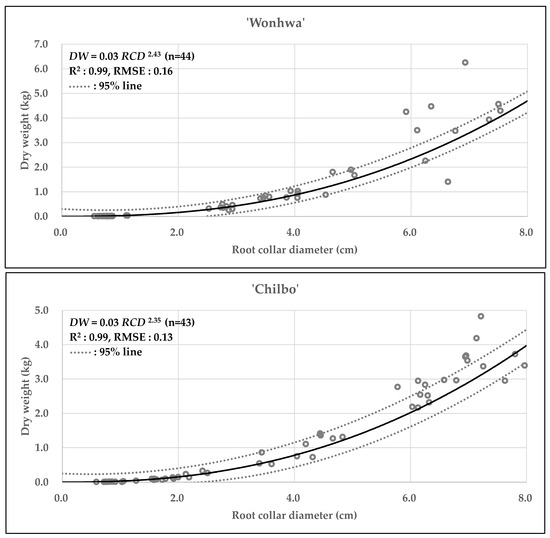

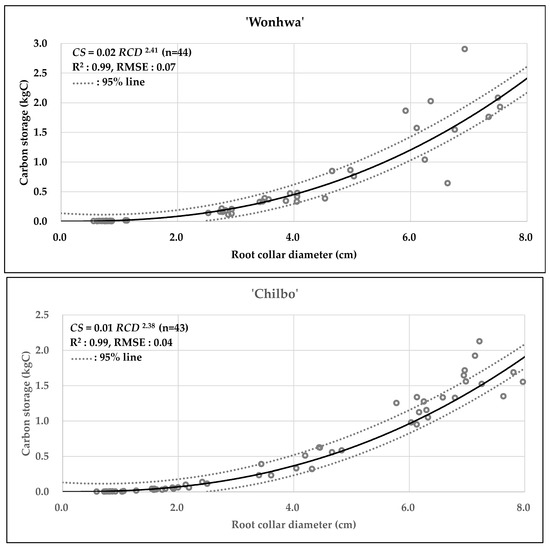

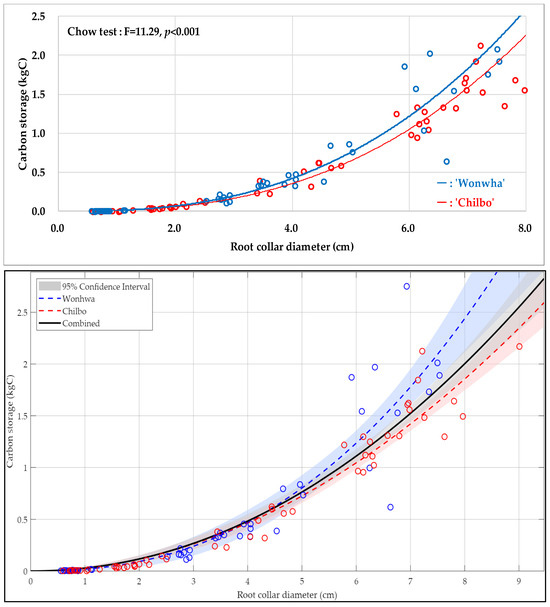

Table 8 and Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the statistical summary and visual representation of the final allometric equation models developed. The non-linear regression analysis, using RCD as the predictor, resulted in distinct and power-function with high explanatory power equations for both cultivars. The model for ‘Wonhwa’ was CS = 0.02RCD2.41 (R2 = 0.99), and for ‘Chilbo’ it was CS = 0.01RCD2.38 (R2 = 0.99). Both models demonstrated a very high coefficient of determination, indicating that they explain 99% of the variability in the data. The scatter plots in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 visually confirm this, as the regression lines closely align with the actual data points. The extra sum-of-squares F-test showed that the difference between the two cultivar-specific models was statistically significant (p < 0.001). This strongly supports the validity of using separate models for ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’ rather than a single combined model.

Table 8.

Statistical summary of the F-test comparing separate and combined allometric equation models.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of dry weight (kg) as a function of root collar diameter (cm) for Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’, and ‘Chilbo’. Circles indicate observed data. The solid lines represent the fitted allometric equation models, and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals for each model.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of carbon storage (kgC) as a function of root collar diameter (cm) for Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’, and ‘Chilbo’. Circles indicate observed data. The solid lines represent the fitted allometric equation models, and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals for each model.

Figure 3.

Carbon storage allometric equation models for Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’ (blue) and ‘Chilbo’ (red). The top graph presents the results of the Chow test comparing the two equations. Below, the blue and red circles denote the observed values for ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’, respectively, and the shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

To evaluate the impact of the cultivation environment (younger pot-grown and older field-grown) on the allometric equations, a Chow test was conducted, with results summarized in Table 9. Analyzing all Hibiscus samples collectively revealed a statistically significant difference between the allometric equations of the younger pot-grown and older field-grown groups (p < 0.05). This finding indicates that both the cultivation environment and age influence the overall growth patterns of Hibiscus. When examining the cultivars individually, no significant difference was observed between the two groups for ‘Wonhwa’ (p > 0.05). In contrast, a highly significant difference was found for ‘Chilbo’ (p < 0.001), suggesting that the ‘Chilbo’ cultivar exhibits a more pronounced change in growth patterns in response to the cultivation environment and growth stage compared to ‘Wonhwa’.

Table 9.

Allometric equation model comparison by cultivation environment/age group (Chow test).

3.3. Comparison of Root-Shoot Ratio Between Cultivars by Growth Environment

Table 10 summarizes the results of the t-test comparing the root-shoot ratio (R) allocation between the ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’ cultivars in both growth environments. A highly significant difference was found between the two cultivars in both younger pot-grown and older field-grown conditions (p < 0.001). In the younger pot-grown group, the mean R of ‘Chilbo’ was significantly higher than that of ‘Wonhwa’. This difference was even more pronounced in the field-grown group, where ‘Chilbo’s’ mean R was over three times greater than that of ‘Wonhwa’. These findings suggest that ‘Chilbo’ consistently allocates a significantly larger proportion of its biomass to roots compared to ‘Wonhwa’, regardless of the cultivation environment.

Table 10.

Comparison of t-test for Root-Shoot Ratio between cultivars by growth environment.

4. Discussion

In this study, both Hibiscus syriacus cultivars exhibited a branch-dominant biomass allocation pattern, with branches accounting for approximately 50–51% of the total biomass (Table 3). This architecture contrasts with the stem-dominant pattern (typically 36–44%) observed in major landscape trees such as Zelkova, Acer, and Ginkgo [2,7,9]. This allocation strategy reflects the inherent growth form of Hibiscus syriacus, which exhibits a pattern favoring lateral canopy expansion over vertical stem growth, a trait that likely facilitates an enhanced flowering display. Similar branch-heavy patterns have been reported for other shrubs species [41,50,51], supporting the view that generalized forest-based equations may not be suitable for these cultivars [7,9].

Our variable importance analysis identified Root Collar Diameter (RCD) as a reliable single predictor for carbon storage, showing higher R2 values compared to Height and Crown Width (Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7). The performance of RCD can be attributed to the morphology of these cultivars. For shrubs and small trees, RCD serves as a proxy for the total volume of conductive tissue [39]. This finding is consistent with literature advocating the use of RCD over DBH or height for estimating the biomass of shrubs and small trees [28,40].

A key finding of this research is the statistically significant difference between the allometric equations of ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’ (p < 0.001), supporting our hypothesis that distinct cultivars require separate models. This divergence is driven by their inherent morphological traits: ‘Wonhwa’ is characterized by an erect form with rapid vertical growth, whereas ‘Chilbo’ displays a spreading form with a more open canopy [35]. These inherent morphological traits likely influence distinct biomass allocation strategies, although environmental plasticity also plays a role. This indicates that a single pooled model may not be applicable. This underscores the necessity of developing cultivar-specific models, corresponding to IPCC Tier 3 standards, to reduce uncertainty in urban carbon inventories where specific cultivars are intensively managed [29,48].

Furthermore, ‘Chilbo’ consistently exhibited a higher root-to-shoot ratio and greater phenotypic plasticity between the younger pot-grown group and the older field-grown group compared to ‘Wonhwa’ (Table 9 and Table 10). It is important to note that because the younger trees were pot-grown and the older trees were field-grown, the effects of ontogeny (age) and cultivation environment are confounded and cannot be statistically separated in this study. However, the observed variations in the younger pot-grown group likely reflect the plants’ physiological response to restricted rooting volumes. These findings align with the ‘fast-slow’ plant economics spectrum theory and are consistent with previous studies on the impact of containerization on root architecture [23,52,53,54].

5. Conclusions

This study developed cultivar-specific allometric equations for Hibiscus syriacus ‘Wonhwa’ and ‘Chilbo’, addressing the data gap for these widely planted urban shrubs, which are extensively managed in South Korean streetscapes as the national flower [5,35]. Our results highlight three key findings based on quantitative evidence:

Model Accuracy: Root collar diameter (RCD) was identified as the most reliable predictor, exhibiting stability against outliers and yielding power-function models with high explanatory power (R2 = 0.99 for both cultivars) compared to height or crown width.

Biomass Allocation: Both cultivars exhibited a unique branch-dominant allocation pattern, with branches comprising approximately 50–51% of the total biomass, which contrasts significantly with the stem-dominant pattern of typical timber species.

Genetic Divergence: A statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) was confirmed between the allometric equations of the erect-type ‘Wonhwa’ and the spreading-type ‘Chilbo’. This divergence reflects their distinct ecological strategies, where ‘Chilbo’ allocates more resources to roots, demonstrating higher phenotypic plasticity in response to cultivation environments.

6. Recommendations

Based on these findings, we offer the following recommendations to enhance the precision of urban carbon inventories:

Adoption of Cultivar-Specific Models: Urban forest managers should apply the specific equations derived in this study (‘Wonhwa’, ‘Chilbo’) rather than a generic species-level mean. Using a pooled model may lead to estimation errors due to the distinct morphological traits of each cultivar.

Consideration of Nursery History: When assessing carbon stocks of young plantations, practitioners should account for the cultivation history (younger pot-grown and older field-grown), as root-to-shoot ratios can vary notably during the establishment phase.

Refinement of Inventories: To meet IPCC Tier 3 standards, urban greening inventories should be updated to record specific cultivar information. Future research should expand this methodology to other shrub species with high horticultural value to construct a comprehensive urban carbon database.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-K.K., H.S. and C.-B.K.; methodology, H.-K.K.; software, H.-K.K.; validation, S.L. and Y.-K.L.; formal analysis, H.-K.K.; investigation, G.-E.B., H.-A.K. and J.-S.L.; resources, H.S. and J.-M.L.; data curation, S.-H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-K.K.; writing—review and editing, C.-B.K., H.S. and J.-M.L.; visualization, H.-K.K.; supervision, C.-B.K.; project administration, C.-B.K. and H.-C.K.; funding acquisition, C.-B.K. and Y.-J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a fund from the Sejong National Arboretum (SJNA), Korean Arboreta and Gardens Institute (KoAGI). This work was supported by the Research Program for Forest Science & Technology Development of the National Institute of Forest Science (Project No. FG0403-2023-02-2025).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| CF | Carbon fraction |

| CS | Carbon storage |

| CW | Crown Width |

| H | Height |

| R | Root-shoot ratio |

| LAR | Least Absolute Residuals |

| RCD | Root collar diameter |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RR | Robust Regression |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Morphological characteristics of Hibiscus syriacus cultivar: (A) Flower form of ‘Wonhwa’, (a) plant form of ‘Wonhwa’, (B) flower form of ‘Chilbo’, and (b) plant form of ‘Chilbo’.

Table A1.

Hibiscus syriacus Cultivar Characteristics [35].

Table A1.

Hibiscus syriacus Cultivar Characteristics [35].

| Cultivar | Classification | Breeding Method | Organization | Release |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Wonhwa’ | White with red-eye zone | Artificial selection | National Institute of Forest Science (Republic of Korea) | 1990. |

| ‘Chilbo’ | Pink with red-eye zone | Artificial selection | National Institute of Forest Science (Republic of Korea) | 1990. |

Table A2.

Growth Characteristics of Hibiscus syriacus for Cultivar [35].

Table A2.

Growth Characteristics of Hibiscus syriacus for Cultivar [35].

| Cultivar | Shape | Shape Index | Annual Shoot Growth (cm) | Leaf Shape | Number of Leaves per Branch | Leaf Blade | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (cm) | Width (cm) | ||||||

| ‘Wonhwa’ | Semi-erect | 60~63 | 58.9 | Broadly ovate | 14.7 | 5.3~6.8 | 3.8~5.0 |

| ‘Chilbo’ | Spreading | 65~66 | 42.1 | Lanceolate | 7.7 | 5.9~6.5 | 2.6~4.1 |

Note: It quantifies the tree’s size, shape, and density, A high crown index indicates that a tree’s branches are widely spread. Conversely, alow crown index suggests an arrow and tree plant shape., Data for ‘No. of nodes with leaves’ derived from this study; other traits from [35].

Table A3.

Flowering Characteristics of Hibiscus syriacus for Cultivar.

Table A3.

Flowering Characteristics of Hibiscus syriacus for Cultivar.

| Cultivar | Flower Type | Flower Diamter (cm) | Flowering Period | Duration of Flowering (Day) | Number of Flowers per Node (Inflorescence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Wonhwa’ | Single flower | 8–12 | Late June–Early October | 89–103 | 2.6–3.8 |

| ‘Chilbo’ | Single flower | 8–9 | Early July–Mid-September | 79–108 | 1.4–3.8 |

References

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Urban Trees in the USA. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, H.-K.; Ahn, T.-W. Carbon Storage and Uptake by Deciduous Tree Species for Urban Landscape. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 40, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Calvo Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize, S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P., Federici, S., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, X. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Urban Forests in Shenyang, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G. History of Seoul’s Parks and Green Space Policies: Focusing on Policy Changes in Urban Development. Land 2022, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, N.; Escobedo, F.J.; Staudhammer, C.L.; Brandeis, T. Analyzing the Causal Factors of Carbon Stores in a Subtropical Urban Forest. Ecol. Complex. 2014, 20, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Baek, G.; Choi, B.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Son, Y.; Kim, C. Allometric Equations for Estimating the Carbon Storage of Maple Trees in an Urban Settlement Area. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2023, 112, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizgar, L.; Pattnaik, N.; Yazdi, H.; Qiguan, S.; Pauleit, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Ludwig, F.; Pretzsch, H.; Rötzer, T. Branch Biomass Allometries for Urban Tree Species Based on Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) Data. Trees 2025, 39, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Baek, G.; Choi, B.; Lee, J.; Son, Y.; Kim, C. Development of Allometric Equations for Carbon Storage of Ginkgo Biloba Linn., Zelkova Serrata (Thunb.) Makino. and Prunus × Yedoense Matsum. Planted in Jinju-City. J. Clim. Chang. Res. 2022, 13, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.K.; Park, C.-W.; Lee, S.J.; Ko, S.; Kim, K.N.; Son, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Oh, S.; Lee, W.-K.; Son, Y. Allometric Equations for Estimating the Aboveground Volume of Five Common Urban Street Tree Species in Daegu, Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, E.G.; Van Doorn, N.; De Goede, J. Structure, Function and Value of Street Trees in California, USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.P.; Lai, H.R.; Wijedasa, L.S.; Tan, P.Y.; Edwards, P.J.; Richards, D.R. Height–Diameter Allometry for the Management of City Trees in the Tropics. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 114017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, H.C.; McDonnell, J.P. Biomass Measurement: A Synthesis of the Literature. In Tennessee Valley Authority, Proceedings of the IUFRO Workshop on Forest Resource Inventories, Vernon, BC, Canada, 22–27 July 1979; Tennessee Valley Authority: Norris, TN, USA, 1979; pp. 544–595. [Google Scholar]

- Peper, P.; McPherson, E.G.; Mori, S. Equations for Predicting Diameter, Height, Crown Width, and Leaf Area of San Joaquin Valley Street Trees. Arboric. Urban For. 2001, 27, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-M.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, B.; Jung, J.-Y.; Lee, S.; Jo, H.; Kim, G.; Kwon, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Yoon, T.K.; et al. Enhanced Accuracy in Urban Tree Biomass Estimation: Developing Allometric Equations with Land Use Classifications. Forests 2025, 16, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, C.; Escobedo, F.J.; Zipperer, W.C. A Framework for Developing Urban Forest Ecosystem Services and Goods Indicators. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 99, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, K.M.; Lum, S. Aboveground Biomass Estimation of Tropical Street Trees. J. Urban Ecol. 2018, 4, jux020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, M.R.; Burke, I.C.; Lefsky, M.A.; Peper, P.J.; McPherson, E.G. Urban Forest Biomass Estimates: Is It Important to Use Allometric Relationships Developed Specifically for Urban Trees? Urban Ecosyst. 2009, 12, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampoorter, E.; De Frenne, P.; Hermy, M.; Verheyen, K. Effects of Soil Compaction on Growth and Survival of Tree Saplings: A Meta-Analysis. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2011, 12, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speak, A.F.; Salbitano, F. The Impact of Pruning and Mortality on Urban Tree Canopy Volume. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 79, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, S.; Fini, A.; Napoli, M.; Frangi, P.; Vigevani, I.; Corsini, D.; Ferrini, F. Effects of Severe Pruning on the Microclimate Amelioration Capacity and on the Physiology of Two Urban Tree Species. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 103, 128583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Biber, P.; Uhl, E.; Dahlhausen, J.; Rötzer, T.; Caldentey, J.; Koike, T.; Van Con, T.; Chavanne, A.; Seifert, T.; et al. Crown Size and Growing Space Requirement of Common Tree Species in Urban Centres, Parks, and Forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass Allocation to Leaves, Stems and Roots: Meta-analyses of Interspecific Variation and Environmental Control. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.; Haoran, W.; Mehmood, K.; Muhammad, B.; Hussain, W.; Hussain, K.; Shahzad, F.; Qun, Y.; Zhongkui, J. Evaluating Biomass and Carbon Stock Responses to Thinning and Pruning in Mature Larix Principis-Rupprechtii Mayr Stands: A Case Study from Northern China. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2025, 8, 1592009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, E.G.; Van Doorn, N.S.; Peper, P.J. Urban Tree Database and Allometric Equations; General Technical Report PSW-GTR-253; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, A.; Rötzer, T.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, H. Structure and Ecosystem Services of Small-Leaved Lime (Tilia Cordata Mill.) and Black Locust (Robinia Pseudoacacia L.) in Urban Environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B. The World-wide ‘Fast–Slow’ Plant Economics Spectrum: A Traits Manifesto. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, C.; Zhou, L.; Gui, Q.; Gong, M.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Chai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X. Intraspecific Variation and Environmental Determinants of Leaf Functional Traits in Polyspora Chrysandra Across Yunnan, China. Plants 2025, 14, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöman, H.; Watkins, H.; Kelly, L.J.; Hirons, A.; Kainulainen, K.; Martin, K.W.E.; Antonelli, A. Resilient Trees for Urban Environments: The Importance of Intraspecific Variation. Plants People Planet 2024, 6, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerband, A.C.; Funk, J.L.; Barton, K.E. Intraspecific Trait Variation in Plants: A Renewed Focus on Its Role in Ecological Processes. Ann. Bot. 2021, 127, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureysens, I.; Bogaert, J.; Blust, R.; Ceulemans, R. Biomass Production of 17 Poplar Clones in a Short-Rotation Coppice Culture on a Waste Disposal Site and Its Relation to Soil Characteristics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 187, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváthová, E.; Badura, T.; Duchková, H. The Value of the Shading Function of Urban Trees: A Replacement Cost Approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kwon, S.-H.; Park, Y.; Choi, Y.-I.; Kwon, H.-Y. ‘Huiwon’: A Cultivar of Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus L.) with Plate-Shaped Flowers for Pot Cultivation. Korean J. Breed. Sci. 2024, 56, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.; Shin, H. ‘Laon’: A Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus L.) Cultivar with a Large and Distinct Eye Zone Developed for Pot Cultivation. Flower Res. J. 2025, 33, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Forest Research Institute (KFRI). Characteristics of Hibiscus Syriacus Cultivars; KFRI: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafatmandrad, M.; Khosravi Mashizi, A. Plant Species Selection for Urban Green Spaces in Arid Lands: A New Approach Using Ecosystem Services and Disservices. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, U.K.; Senthil, R. Framework for Enhancing Urban Living Through Sustainable Plant Selection in Residential Green Spaces. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Assessment and Valuation of the Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Forests. In Ecology, Planning, and Management of Urban Forests; Carreiro, M.M., Song, Y.-C., Wu, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 53–83. ISBN 978-0-387-71424-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Fang, X.; Wu, A.; Xiang, W.; Lei, P.; Ouyang, S. Allometric Equations for Estimating Biomass of Natural Shrubs and Young Trees of Subtropical Forests. New For. 2024, 55, 15–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucker, T.; Bouriaud, O.; Coomes, D.A. Crown Plasticity Enables Trees to Optimize Canopy Packing in Mixed-species Forests. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; Enrico, L.; Casanoves, F.; Díaz, S. Shrub Biomass Estimation in the Semiarid Chaco Forest: A Contribution to the Quantification of an Underrated Carbon Stock. Ann. For. Sci. 2013, 70, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, N.; Saint-André, L.; Henry, M. Manual for Building Tree Volume and Biomass Allometric Equations: From Field Measurement to Prediction; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.C.; Martin, A.R. Carbon Content of Tree Tissues: A Synthesis. Forests 2012, 3, 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.; Lee, S.; Oh, S. Improved Measures of Redundancy and Relevance for mRMR Feature Selection. Computers 2019, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.A.; Trong, N.L.; Cong, D.B.; Nguyen, P.N. MRMR Feature Selection Algorithm for Microgrid Frequency Stability Classification. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 23422–23429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Long, F.; Ding, C. Feature Selection Based on Mutual Information Criteria of Max-Dependency, Max-Relevance, and Min-Redundancy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y. Biomass Allocation and Allometry in Juglans Mandshurica Seedlings from Different Geographical Provenances in China. Forests 2024, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K. Estimation of Carbon Storage Through the Development of Carbon Emission Factorsfor Major Shrubs in Neighborhood Green Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Annighöfer, P.; Ameztegui, A.; Ammer, C.; Balandier, P.; Bartsch, N.; Bolte, A.; Coll, L.; Collet, C.; Ewald, J.; Frischbier, N.; et al. Species-Specific and Generic Biomass Equations for Seedlings and Saplings of European Tree Species. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintural, W.P.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Go, S.; Park, B.B. Quantifying Regulating Ecosystem Services of Urban Trees: A Case Study of a Green Space at Chungnam National University Using i-Tree Eco. Forests 2024, 15, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J. Allocation, Plasticity and Allometry in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhu, W.; Du, A.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z. Stand Age Affects Biomass Allocation and Allometric Models for Biomass Estimation: A Case Study of Two Eucalypts Hybrids. Forests 2025, 16, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.; Wiseman, P.E.; Dickinson, S.; Harris, J.R. Contemporary Concepts of Root System Architecture of Urban Trees. Arboric. Urban For. 2010, 36, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).