Abstract

Madhuca hainanensis is a rare, endemic tree species of Hainan Island, with considerable ecological and economic value. Its natural regeneration is severely limited by habitat fragmentation and environmental stress. To investigate its adaptive across environmental gradients, we established experimental plots in the Jianfengling area of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, encompassing elevation (400–1000 m) and canopy closure (30%–90%) gradients. Sapling growth and health were monitored for one year, alongside measurements of soil physicochemical properties and leaf photosynthetic pigment content. The results indicate that elevation was the primary factor influencing growth, with saplings at lower elevations exhibiting higher increments in height, diameter, and crown spread. While canopy closure was not statistically significant, moderate openness (30%–50%) at low elevations favored growth, whereas high-elevation, heavily shaded conditions constrained development. Sapling health declined over time, particularly in high-elevation and high-canopy-closure plots, and the interaction between elevation and canopy closure amplified physiological stress. Redundancy analysis revealed that elevation and canopy closure jointly explained ~36%–38% of the variance in growth and health, with chlorophyll a, carotenoids, and soil available phosphorus also contributing to sapling performance. These findings indicate that M. hainanensis is highly sensitive to light and elevation-related environmental gradients, and that low-elevation sites with moderate canopy openness are optimal for restoration and cultivation. This study provides a scientific basis for in situ conservation, wild reintroduction, and management of this threatened endemic species.

1. Introduction

Madhuca hainanensis Chun & F.C. How is a tall evergreen tree in the family Sapotaceae, endemic to Hainan Island. It is a rare species valued for its hard, dense, and decay-resistant timber, suitable for machinery, shipbuilding, and bridge construction. The seeds are rich in oil, with potential applications in culinary use, soap production, and medicine [1,2,3]. Due to its dual ecological and economic importance, wild populations of M. hainanensis have been subjected to extensive logging since the 20th century, resulting in a sharp decline in habitat area. Currently, the species persists only in fragmented populations within Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, including the Diaoluoshan, Jianfengling, and Bawangling regions, as well as several remote mountainous areas [3,4]. It is listed as a Class II nationally protected plant and recognized as a vulnerable species [5,6].

The distribution pattern of M. hainanensis is influenced by a combination of environmental and biological factors. Prolonged deforestation and habitat fragmentation have severely reduced its native range. Remaining individuals are mainly found on mid- to upper slopes and ridges at elevations ranging from a few hundred to over one thousand meters, where water and thermal resources are relatively sufficient [7,8,9]. However, the species’ reproductive biology limits its dispersal potential: its fleshy fruits have a restricted dispersal range, and the seeds, which mature during the dry season, are prone to dehydration and dormancy, resulting in poor natural regeneration [3]. In addition, geographic barriers such as the Changhua and Nansheng Rivers impede animal-mediated seed dispersal, further restricting gene flow and population expansion [8,10]. Consequently, M. hainanensis exhibits a narrow distribution, population isolation, and high sensitivity to environmental variation, which are all factors that collectively constrain its natural regeneration and ecological resilience.

In recent years, research on the conservation and restoration of M. hainanensis has intensified, covering population surveys, propagation techniques, genetic diversity assessments, wood property analyses, and community structure studies [3,4,11,12]. These investigations have shown that although the species demonstrates high seed germination rates and rapid seedling growth under controlled conditions, its survival in natural environments remains low, primarily due to limiting factors such as light availability, soil moisture, temperature, and stand structure [2,11]. Within tropical forest ecosystems, environmental variables exhibit marked spatial heterogeneity; variations in elevation and canopy structure together create complex microenvironmental gradients [13]. Typically, increasing elevation leads to lower temperatures, altered humidity and nutrient conditions, and reduced solar radiation, all of which strongly influence plant photosynthesis, respiration, and carbon allocation [14]. Meanwhile, canopy closure determines understory light intensity and radiation availability, thereby regulating seedling photosynthetic input, carbon balance, and growth performance [15]. Previous studies have shown that moderate canopy openness promotes the growth and survival of tropical tree seedlings, whereas excessive shading or intense radiation can induce photosynthetic inhibition, oxidative stress, and metabolic imbalance [16,17]. As a light-demanding yet semi-shade-tolerant species, M. hainanensis is expected to be highly responsive to microenvironmental variations across different elevation and canopy closure combinations. These environmental interactions not only affect its photosynthetic capacity and nutrient uptake but also determine its adaptability and potential for successful ecological restoration.

Based on these ecological uncertainties, this study was conducted in the Jianfengling area of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. Experimental plots were established across different elevations and canopy closure levels, focusing on M. hainanensis saplings. Growth indicators and health conditions were systematically monitored, while soil physicochemical properties and leaf photosynthetic pigment content were measured concurrently. Through comprehensive statistical analyses, this research aims to clarify the physiological and ecological responses of M. hainanensis to varying habitat conditions and to reveal its adaptive mechanisms across environmental gradients. The findings provide theoretical foundations and practical guidance for in situ conservation, population restoration, and reintroduction of this endangered tree species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seedling Sources and Selection

Seedlings of M. hainanensis used for the field reintroduction experiment were obtained from the Yunlong Nursery Base of the Hainan Academy of Forestry Sciences. The fruits of M. hainanensis typically ripen from early February to late March each year. Seeds were collected by harvesting naturally fallen mature fruits. After shell removal, seeds were sown in a nursery substrate of river sand, red soil, and cocopeat. Vigorous, pest-free seedlings (~90–100 cm tall) were selected after three years of cultivation and acclimatized for one month at the Jianfengling Nursery, Ledong County, with part of the original substrate retained around roots to reduce transplant shock, before field transplantation.

2.2. Selection of Reintroduction Plots

Based on literature review, expert consultation, and field surveys, the natural distribution range of M. hainanensis was delineated. Preliminary investigations were conducted using the transect method; once target individuals were located, detailed plot surveys were performed. Within each survey site, 20 m × 20 m tree plots centered on M. hainanensis individuals were established. For each plot, all tree-layer species were recorded, including species name, tree height (≥1.5 m), and diameter at breast height (DBH ≥ 1 cm) (Supplementary Table S1). Results indicated that M. hainanensis populations are mainly distributed in the Jianfengling and Diaoluoshan areas of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, typically inhabiting lowland and montane rainforests at elevations between 400 m and 1000 m.

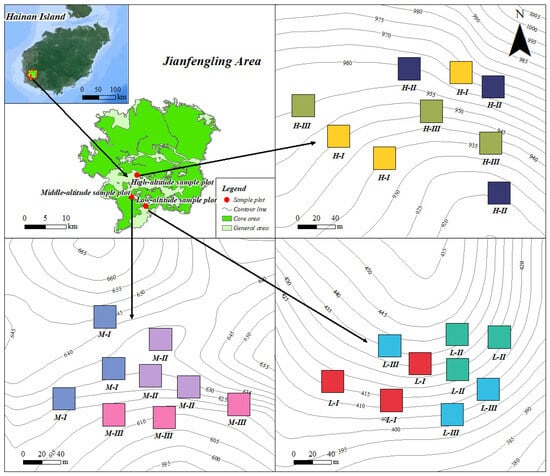

Considering the species’ biological requirements for adequate moisture and light, experimental plots were established across distinct elevation and canopy-closure gradients to simulate representative habitat conditions. Elevation gradients were categorized as low (L: 400–500 m), medium (M: 600–700 m), and high (H: 900–1000 m), while canopy-closure levels were classified as I (30%–50%), II (50%–70%), and III (70%–90%). Elevation was measured using GPS equipment (Garmin GPSMAP 66sr, Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA). Canopy closure was measured using fisheye lens photography(Nikon 8 mm f/2.8, Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan), with image analysis conducted through Hemiview (Delta-T Devices Ltd., Cambridge, UK). This design yielded nine treatment combinations (L-I to H-III), each replicated three times, resulting in a total of 27 plots (20 m × 20 m each) (Figure 1). Within each plot, GPS coordinates and elevation were recorded, and additional habitat parameters, including slope gradient, were also documented for subsequent analysis (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of field planting sites for Madhuca hainanensis saplings. L, M, and H represent low (400–500 m), medium (600–700 m), and high (900–1000 m) elevations, respectively; I, II, and III represent low (30%–50%), medium (50%–70%), and high (70%–90%) canopy closures, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of environmental variables for all experimental plots.

2.3. Field Replanting

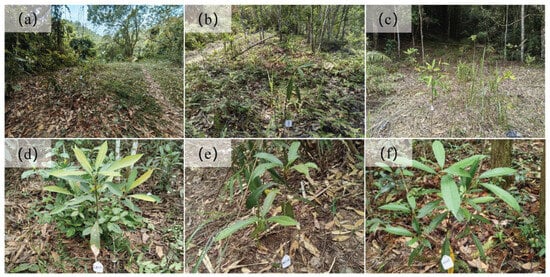

From May to June 2024, 30 saplings were transplanted into each experimental plot, resulting in consistent initial planting densities across all treatments. Prior to planting, the shrub and herbaceous layers within the plots were cleared to ensure uniform environmental conditions, except for differences in light intensity. Before transplantation, saplings were randomly assigned to different plots, and standard site preparation was conducted. Planting holes measuring 30 cm × 30 cm × 40 cm were excavated, and saplings were planted in a manner simulating their natural growth pattern in the wild, avoiding alignment in rows. Tree spacing was set at 1.5 m × 2.0 m. During transplantation, the root systems of saplings were treated with a 0.125% carbendazim solution as root-settling water, followed by immediate thorough watering. After planting, uniform management practices were implemented across all plots, including irregular soil loosening, watering, pest and disease control, and clearing of surrounding vegetation to maintain consistent light conditions. Each sapling was labeled with an identification tag. With 30 saplings planted in each of the 27 plots, a total of 810 saplings were introduced into the field reintroduction experiment. Growth was tracked sequentially according to sapling identification numbers (Figure 2). From June 2024, monitoring of growth and health status was conducted quarterly (September 2024, December 2024, March 2025, and June 2025). For each monitoring period, sample trees were photographed, and corresponding data were recorded.

Figure 2.

Field restoration and growth conditions of Madhuca hainanensis saplings. (a–c): Field restoration sites at different elevations (low, medium, and high); (d–f): Growth performance of M. hainanensis saplings at different elevations in June 2025.

Growth indicators applied in this study included tree height, ground diameter, and crown spread (tree height and crown spread were measured using a diameter tape, while ground diameter was measured with vernier calipers). Health status was evaluated following plant physiology and forest ecology monitoring standards [18,19], with modifications to suit the present study. Sapling health was classified into five categories: healthy, mild stress, moderate stress, severe stress, and dead (Table 2). Due to the low frequency of moderate and severe stress cases, these two categories were combined into a single “moderate–severe stress” category.

Table 2.

Criteria for Assessing the Health Status of Madhuca hainanensis saplings.

2.4. Sample Collection and Analysis

Soil and plant samples were collected from each plot in June 2025. Five healthy individuals were randomly selected per plot. Rhizosphere soil was sampled from the 0–20 cm layer surrounding the root zone of each selected tree. The collected soil was thoroughly mixed, and approximately 500 g of the composite sample was retained for analysis. Upon return to the laboratory, samples were cleaned of stones and plant debris, then sieved through a 2 mm mesh and divided into two subsamples: one air-dried for physicochemical analyses, and the other stored at 4 °C for subsequent determinations.

Leaf samples consisted of mature leaves collected from the same individuals used for soil sampling. Leaf pigments, including chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids, were extracted with 80% acetone following the method of Lichtenthaler [17]. Absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 663 nm, 645 nm, and 470 nm, and pigment concentrations were calculated using standard equations.

Soil physicochemical properties were determined according to established protocols [20]:

- Soil organic matter (SOM): potassium dichromate external heating method.

- Total nitrogen (TN): Kjeldahl digestion method.

- Alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen (AN): alkali diffusion method.

- Total phosphorus (TP): molybdenum–antimony colorimetric method after H2SO4-HClO4 digestion.

- Available phosphorus (AP): molybdenum–antimony colorimetric method after extraction with 0.5 mol L−1 NaHCO3 (pH 8.5).

- Total potassium (TK): NaOH fusion followed by flame photometry.

- Available potassium (AK): flame photometry after extraction with 1 mol L−1 NH4OAc.

- Soil pH: soil–water suspension (1:2.5, w/v) measured using a calibrated pH meter.

2.5. Data Analysis

Prior to statistical analysis, all data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance. Data that did not meet these assumptions were appropriately transformed before further analysis (as in ln(x + 1)). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine differences in height, ground diameter, and crown spread growth of healthy M. hainanensis saplings under different elevation and canopy closure conditions (For growth-related ANOVA, the sample size (n) was the number of healthy saplings recorded in each monitoring period. This number varied over time because stressed and dead individuals were excluded, but all observations originated from the initial 810 planted saplings.). Post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s HSD test at a significance level of p < 0.05. To evaluate the main and interactive effects of environmental gradients on sapling health status, multiple linear regression analysis was performed. Elevation and canopy closure were used as independent variables, while the proportions of saplings in different health categories were treated as dependent variables to assess the influence of key environmental factors on health dynamics. Pearson correlation analysis was applied to explore relationships among growth indicators, health indices, leaf photosynthetic pigments, and soil physicochemical properties. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was subsequently conducted to evaluate the combined explanatory effects of elevation, canopy closure, and soil and leaf physiological factors on sapling growth and health status, thereby identifying dominant environmental drivers. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2. Graphical visualizations were generated using the ggplot2 (version 3.4.2) [21], vegan (version 2.7-2) [22], and corrplot (version 0.84) [23] packages.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Growth Indices of M. hainanensis

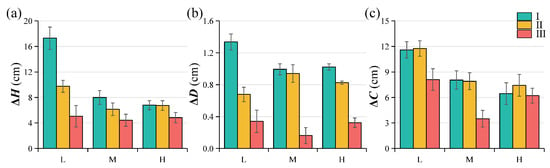

Analysis of annual growth increments revealed that elevation was the only significant predictor of sapling performance. Elevation significantly affected ΔH (p = 0.028) and ΔC (p = 0.008), whereas its effect on ΔD was non-significant. Neither canopy closure nor the interaction between elevation and canopy closure showed significant effects on any growth index (Table 3).

Table 3.

Two-way ANOVA results for elevation and canopy closure effects on sapling growth increments.

Despite the absence of statistical significance for most factors, the descriptive patterns in Figure 3 reveal a clear elevational trend: saplings at lower elevations consistently showed higher increments in height, diameter, and crown spread than those at mid- and high-elevation sites. Under low-elevation, low-canopy-closure conditions (30%–50%), saplings exhibited the most vigorous growth, with mean annual increases of 17.29 cm in height, 1.34 cm in ground diameter, and 11.59 cm in crown spread, values significantly higher than those recorded at mid- and high-elevation sites. In contrast, growth was markedly suppressed under high-elevation, high-canopy-closure conditions (70%–90%), with corresponding increases of only 4.85 cm, 0.32 cm, and 6.21 cm, respectively. Although canopy closure did not exert a statistically significant effect, these descriptive trends suggest that low-elevation habitats with moderate light availability (30%–50% canopy closure) provide the most favorable conditions for M. hainanensis sapling growth, whereas high-elevation and heavily shaded environments impose substantial limitations on development.

Figure 3.

Growth of healthy M. hainanensis saplings in terms of plant (a) height (ΔH), (b) ground diameter (ΔD), and (c) crown spread (ΔC) from June 2024 to June 2025. L, M, and H indicate low, medium, and high elevations; I, II, and III correspond to canopy closure levels of 30%–50%, 50%–70%, and 70%–90%, respectively.

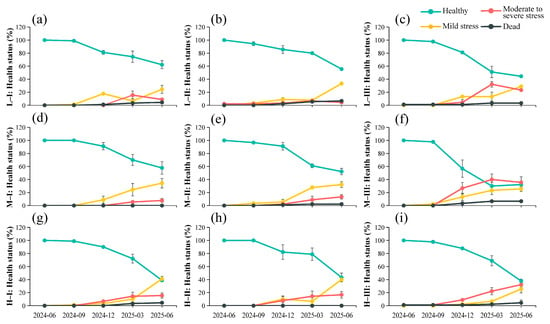

3.2. Dynamic Changes in the Health Status of M. hainanensis

From June 2024 to June 2025, the health status of saplings exhibited marked temporal variation across different elevation and canopy closure conditions (Figure 4). At the beginning of the observation period (June 2024), saplings in all plots were generally healthy, with no visibly stressed or dead individuals. However, from September to December 2024, mild and moderate–severe stress saplings began to appear, particularly in high-elevation and high-canopy-closure (70%–90%) plots. During this period, the proportion of healthy individuals declined from 0.98 to approximately 0.57, while the proportion of moderate–severe stress individuals increased to 0.27. By March 2025, the proportion of healthy saplings in high-elevation, high-canopy-closure plots had fallen below 0.30, the proportion of moderate–severe stress saplings increased to around 0.40, and the mortality rate reached 0.07. By June 2025, health conditions had further deteriorated: the proportion of healthy individuals in these plots ranged from 0.38 to 0.44, while moderate–severe stress accounted for 0.23–0.36. In contrast, saplings in low-elevation, low-canopy-closure plots maintained relatively high health levels (0.58–0.62). Overall, sapling health exhibited a progressive shift over time from “healthy,” “mild stress” to “moderate–severe stress” and “dead,” with the most pronounced deterioration occurring in high-elevation, high-shade environments.

Figure 4.

Temporal dynamics of M. hainanensis health status under different elevations and canopy closure levels. L, M, and H represent low, medium, and high elevation, respectively; I, II, and III represent canopy closure of 30%–50%, 50%–70%, and 70%–90%, respectively. The codes L-I, M-I, H-I, etc., indicate specific combinations of elevation and canopy closure treatments. (a) L-I: 400–500 m, 30%–50% canopy closure; (b) L-II: 400–500 m, 50%–70% canopy closure; (c) L-III: 400–500 m, 70%–90% canopy closure; (d) M-I: 600–700 m, 30%–50% canopy closure; (e) M-II: 600–700 m, 50%–70% canopy closure; (f) M-III: 600–700 m, 70%–90% canopy closure; (g) H-I: 900–1000 m, 30%–50% canopy closure; (h) H-II: 900–1000 m, 50%–70% canopy closure; (i) H-III: 900–1000 m, 70%–90% canopy closure.

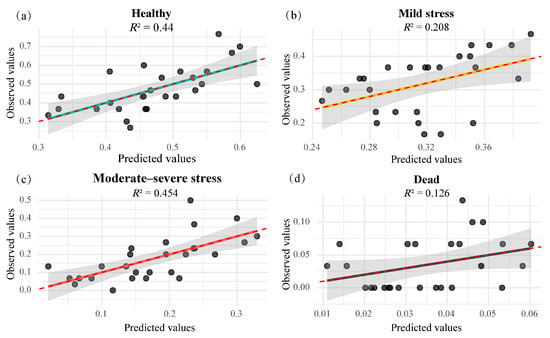

Multiple linear regression analysis further substantiated these findings (Table 4). The proportion of healthy saplings significantly decreased with increasing elevation (p = 0.029) and canopy closure (p = 0.026). The proportion of mild stress saplings showed a positive correlation with elevation (p = 0.015), and a significant interaction was observed between elevation and canopy closure (p = 0.038), suggesting that the combination of high elevation and dense canopy intensified physiological stress. In contrast, neither moderate–severe stress nor mortality showed significant associations with elevation or canopy closure (all p > 0.05), likely due to environmental heterogeneity and individual variability among plots. Model fitting results (Figure 5) demonstrated good consistency between predicted and observed values for some health categories—particularly “Healthy” (R2 = 0.440) and “Moderate–severe stress” (R2 = 0.454)—whereas other categories exhibited weak explanatory power and limited predictive accuracy.

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis of seedling growth status of M. hainanensis in relation to elevation and canopy closure.

Figure 5.

Scatter plots of observed versus predicted values for the health status of M. hainanensis saplings. (a) Proportion of healthy individuals; (b) proportion of mild stress individuals; (c) proportion of moderate–severe stress individuals; (d) proportion of dead individuals. Solid lines represent linear regression fits, and the red dashed line (y = x) serves as a reference to indicate the degree of agreement between predicted and observed values; R2 denotes the coefficient of determination for the model.

3.3. Comprehensive Effects of Environmental Factors on the Growth of M. hainanensis

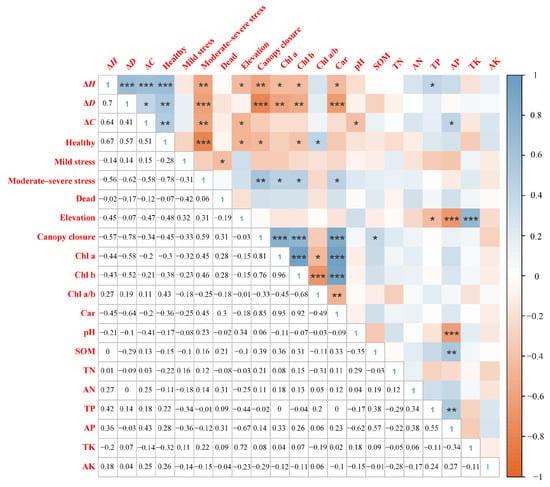

Correlation analysis and RDA indicated that the growth and health status of young M. hainanensis were primarily driven by elevation and canopy closure, while photosynthetic pigment content reflected the physiological adjustments of saplings to these environmental gradients (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Correlation analysis indicated that canopy closure exerted the strongest inhibitory effect on growth, showing significant negative correlations with height increment (ΔH), diameter increment (ΔD), and the proportion of healthy individuals (p < 0.05), but highly significant positive correlations with chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and carotenoid (Car) content (p < 0.01). Elevation also exhibited significant negative correlations with ΔH, crown spread increment (ΔC), and the proportion of healthy individuals (p < 0.05). Among soil variables, only SOM showed a positive correlation with both canopy closure and Car content (p < 0.05), while soil pH was negatively correlated with ΔC. In addition, photosynthetic pigment contents were positively correlated with the proportion of moderate–severe stress individuals (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Heatmap of correlations between growth and health indicators of M. hainanensis and environmental factors. ΔH, ΔD, and ΔC represent increases in plant height, ground diameter, and crown spread, respectively; Chl a, Chl b, and Car represent chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids, respectively; SOM, TN, AN, TP, AP, TK, and AK represent soil organic matter, total nitrogen, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, total phosphorus, available phosphorus, total potassium, and available potassium, respectively. Color intensity indicates the strength of correlation. * indicates significance at p < 0.05, ** at p < 0.01, and *** at p < 0.001.

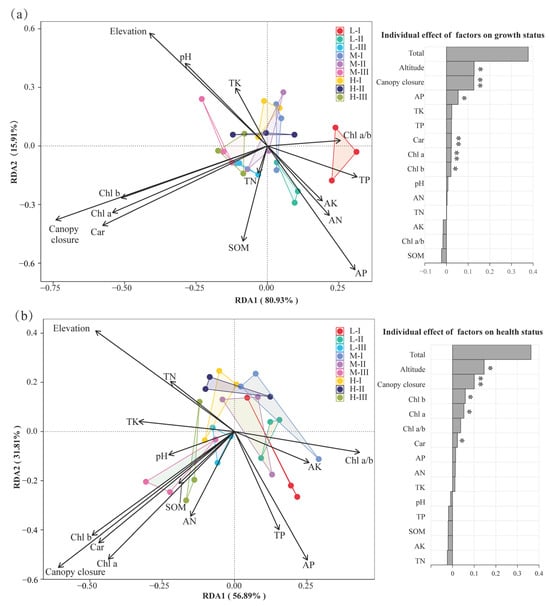

Figure 7.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of environmental factors with (a) growth indices and (b) health status of M. hainanensis. The left panels show the RDA ordination plots, illustrating the distribution of plots and response variables along environmental gradients; the right panels display bar plots of the explanatory contribution of each environmental factor to the response variables (* indicates significance at p < 0.05, and ** at p < 0.01). (a) Response variables: height increment (ΔH), diameter increment (ΔD), and crown spread increment (ΔC). (b) Response variables: proportion of Healthy, Mild stress, Moderate–severe stress, and Dead. Explanatory variables: Elevation, Canopy closure, chlorophyll a (Chl a), chloro-phyll b (Chl b), carotenoids (Car), soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), alka-line hydrolyzable nitrogen (AN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), total potassium (TK), and available potassium (AK).Plot codes (L-I, M-I, H-I, etc.) indicate different combinations of elevation and canopy closure treatments.

RDA further illustrated the integrated influence of environmental factors. For growth indicators (Figure 7a), environmental variables collectively explained approximately 37.8% of the total variance, with RDA1 and RDA2 contributing 80.93% and 15.91%, respectively. Elevation (0.128, accounting for ~33.8%) and canopy closure (0.126, accounting for ~33.5%) were identified as the dominant regulatory factors, while AP (~14.3%), Chl a (~5.8%), and Car (~6.0%) served as secondary contributors. For sapling health status (Figure 7b), environmental factors collectively explained about 36.3% of the total variation. RDA1 and RDA2 accounted for 56.89% and 31.81% of this variation, respectively. Elevation (0.146, 40.2%) and canopy closure (0.100, 27.6%) again emerged as the principal drivers. Chl b (~16.3%), Chl a (~14.5%), and the Chl a/b ratio (~10.4%) also contributed notably to health variation, while Car, AP, AN, and TK exhibited secondary regulatory effects.

4. Discussion

4.1. Response of M. hainanensis Growth to Elevation and Canopy Closure Gradients

Results showed that increases in elevation and canopy closure significantly reduced the growth rates of stem height, ground diameter, and crown spread in M. hainanensis, indicating that high-elevation and high-canopy-cover environments substantially constrain sapling growth and health (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This pattern is consistent with general ecological trends in tropical forest species, where saplings typically exhibit higher photosynthetic efficiency and carbon accumulation under low-elevation, low-canopy-closure conditions with more favorable light and temperature regimes [15,24]. In contrast, high elevations and dense canopies markedly limit light and temperature, which are known to constrain photosynthetic performance and potentially nutrient uptake in many tropical species [25,26,27]. Increased canopy closure may alter understory microclimate, potentially affecting transpiration and root functioning. These interacting physiological constraints are reflected in simultaneous declines in height and diameter growth, supporting the conclusion that M. hainanensis is highly light-sensitive and grows optimally under low to moderate canopy closure in forest gaps or edge habitats.

Dynamic monitoring further revealed a progressive and consistent deterioration in sapling health, transitioning from “healthy” to “mild stress”, “moderate–severe stress”, and ultimately “dead.” This decline was most pronounced in high-elevation, high-closure plots, highlighting the combined limitation of light and low temperature on sapling survival. Regression analysis showed that canopy closure exerted a stronger negative influence on health than elevation (Table 4), emphasizing light availability as the primary factor regulating early carbon balance. Specifically, the reduced understory light likely limits carbon gain, which may contribute to the observed stress responses [28,29]. Meanwhile, shaded environments have been associated with reduced stress tolerance in other species, which may help explain the patterns observed [17,30]. Notably, the interaction between elevation and canopy closure was significant for the “Mild stress” category (p = 0.038), indicating context-dependent effects of shading. At higher elevations, dense canopy at high elevation may intensify low-light and low-temperature constraints, contributing to the observed interaction—intensifying mild stress, whereas at lower elevations, partial shading may buffer heat or water stress, resulting in weaker effects [31,32]. As a typical light-demanding species, M. hainanensis requires sufficient irradiance and nutrient availability for optimal growth, making high-elevation, cooler sites particularly challenging for sapling establishment, as reflected by the increased proportion of stressed saplings [2].

Importantly, the mortality model (Table 4) identified no significant environmental predictors for dead saplings. Although mortality visually appeared higher in high-elevation and high-closure plots (Figure 4), this pattern was too variable to be statistically explained by the measured habitat factors. This suggests that first-year mortality was driven primarily by transplant shock—mortality may reflect a combination of transplant-related stress and microsite heterogeneity, which could obscure clear habitat signals, which collectively obscured any clear habitat signal [33,34]. Two methodological considerations further clarify this outcome. First, elevation is confounded with geographical location, meaning that observed elevational patterns inherently reflect site-level influences such as parent material, herbivory, slope, and microclimate [25,33]. Second, the one-year post-transplant period (June 2024–June 2025) likely captured strong transplant shock superimposed on habitat conditions, especially in high-elevation and high-shade sites, amplifying early mortality [34,35].

4.2. Integrated Regulation of M. hainanensis Growth by Environmental Factors and Implications for Ecological Adaptation

Correlation analysis and RDA revealed that the growth and health status of young M. hainanensis are jointly regulated by multiple environmental factors, including elevation, canopy closure, and photosynthetic pigment content (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Elevation and canopy closure emerged as the dominant environmental drivers, jointly explaining approximately 33%–40% of the total variance, underscoring their decisive role in niche differentiation [25,36]. The remaining >60% unexplained variance likely reflects transplant shock, individual variation in stress resilience, small-scale heterogeneity in soil depth, drainage, and airflow, unmeasured biotic factors (e.g., herbivory or pathogens), and the confounding effect of geographical location [35]. This underscores that the measured variables only partially capture the complexity governing early establishment outcomes.

Photosynthetic pigment indices (Chl a, Chl b, and Car) showed significant positive correlations with canopy closure, likely reflecting a physiological response to shading by increasing chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations under shaded conditions [37,38]. However, pigment content also showed a positive correlation with “moderate–severe stress”, indicating that elevated pigments do not necessarily reflect successful acclimation. In high-shade, high-stress environments, higher pigment levels may reflect a stress-induced adjustment rather than successful acclimation rather than a sign of improved performance. Transplant-related effects may also influence pigment–stress relationships and contribute to variability. Moreover, although morpho-physiological adjustments such as pigment upregulation can partially mitigate shade stress, they are insufficient to compensate for the substantial reductions in carbon assimilation, ultimately resulting in suppressed height, ground diameter, and crown growth [39,40,41]. Interestingly, pigment content was positively correlated with “moderate–severe stress,” suggesting that high pigment levels may not indicate successful acclimation. Saplings in high-shade, high-stress environments may upregulate chlorophyll and carotenoids to enhance light capture and photoprotection, but these adjustments often fail to offset low carbon gain and other stressors [42]. Alternatively, elevated pigments may reflect stress-induced photoprotection, with photosynthetic inefficiency triggering pigment accumulation as a defensive response. Transient effects such as transplant shock may also contribute, temporarily linking high pigment levels to poor sapling health [43].

RDA results indicated that the positive association between chlorophyll content and health status suggest that chlorophyll levels may serve as an indicator of sapling responses to environmental stress. Multiple linear regression models further demonstrate that predictors differ in explanatory power. Models for “Healthy” and “Moderate–severe stress” individuals explained moderate variance, whereas models for “Mild stress” and “Dead” individuals performed poorly. The lack of significant predictors for mortality highlights that early death is governed by complex interactions among transplant shock, microhabitat variability, and unmeasured factors [35,44]. Thus, mortality patterns in this study should not be over-interpreted as deterministic evidence of habitat unsuitability. A significant interaction between canopy closure and elevation was detected in the “Mild stress” category, suggesting that the effect of canopy closure on sapling stress depends on altitude. High canopy closure at high elevations intensifies shading and low-temperature stress, whereas at lower elevations moderate canopy cover may buffer heat or water stress [45,46]. This context-dependent pattern emphasizes the need to consider interactive environmental gradients rather than relying solely on main effects when designing reintroduction and restoration strategies.

4.3. Implications for Restoration and Ecological Adaptation

Although we did not observe natural regeneration of M. hainanensis within the surveyed understory, several mature individuals were recorded in the surrounding forest near our experimental sites. This indicates that the species is present in the landscape, yet successful seedling recruitment is extremely limited. The coexistence of adult trees and the absence of juveniles suggest that regeneration failure may not be fully explained by dispersal limitation alone; microsite constraints are a plausible contributing factor [35,44]. This reinforces our finding that early recruitment is highly sensitive to canopy and elevation conditions, and that the current forest understory—particularly at higher elevations and under dense canopy—provides unsuitable microsites for natural regeneration.

Overall, M. hainanensis exhibits high sensitivity to both light and temperature gradients. Early establishment is primarily constrained by canopy closure, with high-elevation, high-closure environments significantly impeding sapling growth, survival, and potential regeneration. These constraints are further compounded by interactions among elevation, transplant shock, microhabitat heterogeneity (e.g., soil depth, drainage, airflow), and possible provenance effects, all of which contribute to the complexity of early recruitment outcomes [44,47]. Consequently, our results suggest that low-elevation sites with moderate canopy openness may offer more favorable conditions for establishment (30%–50%), such as forest gaps or open woodlands, where sufficient light availability and favorable thermal conditions support optimal sapling establishment. Long-term monitoring is essential to assess whether saplings surviving in higher-elevation or higher-shade habitats can achieve stable growth and ultimately reach reproductive maturity. Future restoration programs should therefore integrate shade management and fine-scale microhabitat assessment to maximize establishment success across heterogeneous environments.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the growth performance and health status of young M. hainanensis trees under varying elevation and canopy closure conditions, elucidating their integrated responses to light, temperature, and soil environments. The key findings are as follows:

- (1)

- The growth of M. hainanensis saplings was mainly driven by elevation, with lower-elevation saplings showing higher increments in height, diameter, and crown spread. While canopy closure was not statistically significant, moderate openness (30%–50%) at low elevations favored growth, whereas high-elevation, shaded conditions constrained development.

- (2)

- Sapling health exhibited a continuous decline throughout the monitoring period. The proportion of healthy individuals significantly decreased in high-elevation and high-canopy-closure plots, while the proportions of mild and moderate–severe stress individuals increased markedly. Multiple regression analysis indicated that canopy closure exerted a stronger negative influence on health than elevation, with a significant interaction between the two factors amplifying physiological stress.

- (3)

- Photosynthetic pigment content increased significantly under high canopy closure, reflecting a degree of light-adaptive adjustment. However, this compensatory response was insufficient to mitigate growth inhibition under low-light conditions. SOM and AP promoted sapling growth, whereas pH and AK exhibited no significant effects. These findings suggest that, in tropical lowland rainforests, light limitation plays a more critical role than nutrient limitation in regulating early sapling growth.

Overall, M. hainanensis saplings appear highly sensitive to environmental gradients associated with elevation—particularly changes in light availability—during their early developmental stages. Saplings showed better growth performance in lower-elevation sites with moderately open canopies, conditions similar to forest gaps or open stands. To improve survival rates during artificial reintroduction and enhance natural regeneration potential, ecological restoration should prioritize habitats with sufficient light and moderate canopy openness. Management measures aimed at optimizing understory light through canopy regulation are also recommended.

This study provides a scientific basis for assessing habitat adaptability and guiding restoration and management strategies for M. hainanensis. It also offers valuable reference for the conservation and reintroduction of other rare tropical tree species. Future research should focus on the long-term growth dynamics, community-level competition interactions, and regeneration mechanisms of M. hainanensis as well as the roles of key edaphic factors in shaping its ecological niche. Such efforts will help refine population conservation and restoration strategies and provide a more robust scientific foundation for managing this threatened endemic species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121844/s1, Table S1: Field survey data of M. hainanensis.

Author Contributions

R.W. and X.W.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, data curation writing; B.Z. and L.L.: Data curation, Visualization; J.Y., X.L., Z.D. and F.L.: methodology, investigation; B.W., S.H. and J.L.: resources, supervision, project administration. All authors contributed to the article, approved the submitted version, revised the manuscript, and provided assistance with review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hainan Province Department of Science and Technology (Technological lnnovation Special Grant for Provincial Research Institutes, No. KYYSLK2023-013).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, L.; Zeng, D.Q.; Chen, F.F.; Liu, M.H. Research summary on current status and suggestions of Madhuca hainanensis. Trop. For. 2018, 46, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Duan, Z.J.; Liao, L.G.; Zhang, B.J.; Yang, J.; Wu, B. Research progress and conservation strategies of Madhuca hainanensis. For. Sci. Commun. 2025, 68, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H.; Zhang, S.W.; Yang, X.B.; Li, D.H.; Shang, N.Y.; Du, C.Y. Madhuca hainanensis community species composition and interspecific association. J. South. Agric. 2024, 55, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.T.; Chen, Y.K.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y. The complete chloroplast genome of Madhuca hainanensis (Sapotaceae), an endemic and endangered timber species in Hainan Island, China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2021, 6, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.H.; Zhong, Q.X.; Fu, Y.D. Rare and endangered plants and key protected wild plants in Hainan. J. Hainan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2003, 16, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.Q.; Chen, Y.K.; Yang, X.B.; Zhang, K.; Li, D.H.; Jiang, Y.X.; Li, J.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, S.W.; Zhu, Z.C. A dataset on inventory and geographical distributions of wild vascular plants in Hainan Province. China Biodivers. Sci. 2023, 31, 23067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.D.; Du, S.J.; Xu, X.O.; Zou, Y.J.; Wu, H.X.; Lin, Z.W. Quantitative analysis of priority conservation of endemic wild endangered woody plants in Hainan. For. Environ. Sci. 2018, 34, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.L.; Huang, S.M. Study on the natural distribution of Madhuca hainanensis. Trop. For. 1996, 24, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, S.L. Preliminary study on national level protected wild plant resources in Hainan Mihouling forest farm. Trop. For. 2015, 43, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.L.; Wang, L.L.; Han, W.T.; Wang, J. Discussion on ecological protection and restoration of tropical rain forest in Hainan. For. World 2025, 14, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.J.; Lin, B.; Chen, F.F.; Zeng, X.Q. Germination experiment research of Madhuca hainanensis seed. Trop. For. 2017, 45, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.P.; Chen, L.; Luo, W.; Jim, C.Y. Species diversity and distribution pattern of venerable trees in topical Jianfengling National Forest Park (Hainan, China). J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 77, 126542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Weber, B.; Ryel, R.J. Spatial and temporal variability of canopy structure in a tropical moist forest. Acta Oecol. 2001, 22, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, K.; Aiba, S.I. Ecosystem structure and productivity of tropical rain forests along altitudinal gradients with contrasting soil phosphorus pools on Mount Kinabalu Borneo. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Ntagkas, N.; Siebenkäs, A.; Mäenpää, M.; Matsubara, S.; Pons, T. A meta-analysis of plant responses to light intensity for 70 traits ranging from molecules to whole-plant performance. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1073–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, J.L.; Thomas, S.C. Determinants of whole-plant light requirements in Bornean rain forest tree saplings. J. Ecol. 2007, 95, 1208–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Niinemets, Ü. Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Importance of root growth in overcoming planting stress. New For. 2005, 30, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, A.N. Physiological processes in plantation establishment and the development of specifications for forest planting stock. Can. J. For. Res. 1990, 20, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Package ‘Vegan’; R Package Version 2.7-2. 2025. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Wei, T.Y.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.H.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J.; Freidank, M.; Cai, J.; Protivinsky, T. Corrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix; R Package Version 0.84. 2017. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Kitajima, K. Relative Importance of Photosynthetic Traits and Allocation Patterns as Correlates of Seedling Shade Tolerance of 13 Tropical Trees. Oecologia 1994, 98, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arihafa, A.; Mack, A.L. Treefall gap dynamics in a tropical rain forest in Papua New Guinea. Pac. Sci. 2013, 67, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Tropical forest recovery: Legacies of human impact and natural disturbances. Perspect. Plant Ecol. 2003, 6, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.; Pockman, W.T.; Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; Cobb, N.; Kolb, T.; Plaut, J.; Sperry, J.; West, A.; Williams, D.G.; et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: Why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 2008, 178, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, W.H.; Duan, G.H.; Chen, J.L.; Zhu, W.S.; Wu, J.W. The age-dependent response of carbon coordination in the organs of Pinus yunnanensis seedlings under shade stress. Plants 2025, 14, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.P.; Tan, Z.M.; Zhou, Y.G.; Guo, S.R.; Sang, T.; Wang, Y.; Shu, S. Physiological mechanism of strigolactone enhancing tolerance to low-light stress in cucumber seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, E.V.; Vitousek, P.A.; Cuevas, E. Experimental investigation of nutrient limitation of forest growth on wet tropical mountains. Ecology 1998, 79, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottingham, A.T.; Turner, B.L.; Whitaker, J.; Ostle, N.J.; McNamara, N.P.; Bardgett, R.D.; Salinas, N.; Meir, P. Soil microbial nutrient constraints along a tropical forest elevation gradient: A belowground test of a biogeochemical paradigm. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 6071–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard Verdier, M.; Navas, M.L.; Vellend, M.; Violle, C.; Fayolle, A.; Garnier, E. Community assembly along a soil depth gradient: Contrasting patterns of plant trait convergence and divergence in a M editerranean rangeland. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliet, J.A.; Puértolas, J.; Planelles, R.; Jacobs, D.F. Nutrient loading of forest tree seedlings to promote stress resistance and field performance: A Mediterranean perspective. New For. 2013, 44, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Why seedlings survive: Influence of plant attributes. New For. 2012, 43, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricca, A.; Di Musciano, M.; Ferrara, A.; Theurillat, J.-P.; Cutini, M. Community assembly along climatic gradient: Contrasting pattern between-and within-species. Perspect. Plant Ecol. 2022, 56, 125675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Ač, A.; Marek, M.V.; Kalina, J.; Urban, O. Differences in pigment composition, photosynthetic rates and chlorophyll fluorescence images of sun and shade leaves of four tree species. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 45, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Bhadouria, R.; Srivastava, P.; Devi, R.S.; Chaturvedi, R.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Effects of light availability on leaf attributes and seedling growth of four tree species in tropical dry forest. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.J.; Kitajima, K.; Kraft, N.J.; Reich, P.B.; Wright, I.J.; Bunker, D.E.; Condit, R.; Dalling, J.W.; Davies, S.J.; Díaz, S.; et al. Functional traits and the growth–mortality trade-off in tropical trees. Ecology 2010, 91, 3664–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiba, S.I.; Kitayama, K. Light and nutrient limitations for tree growth on young versus old soils in a Bornean tropical montane forest. J. Plant Res. 2020, 133, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmig Adams, B.; Adams, W.W., III. Photoprotection in an ecological context: The remarkable complexity of thermal energy dissipation. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, M.; Kołton, A.; Muras, P. The complex issue of urban trees—Stress factor accumulation and ecological service possibilities. Forests 2020, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Sohail; Zaman, S.; Li, G.H.; Fu, M. Adaptive responses of plants to light stress: Mechanisms of photoprotection and acclimation. A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1550125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löf, M.; Madsen, P.; Metslaid, M.; Witzell, J.; Jacobs, D.F. Restoring forests: Regeneration and ecosystem function for the future. New For. 2019, 50, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.U.; Afzal, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Hart, R.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Alsubeie, M.S.; Calixto, E.S.; Ijaz, F.; Ali, N.; et al. Response of plant physiological attributes to altitudinal gradient: Plant adaptation to temperature variation in the Himalayan region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Jose, S.; Nichols, J.D.; Bristow, M. Growth and physiological response of six Australian rainforest tree species to a light gradient. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Shen, S.F.; Chan, S.F. Niche theory and species range limits along elevational gradients: Perspectives and future directions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2024, 55, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).