Application of Cow Manure Enhances Soil Nutrients, Reshapes Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Promotes Growth of Toona fargesii Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Chemical Analysis of Soil Samples

2.4. DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of Cow Manure Application on Soil Properties and Seedling Growth

3.2. The Bacterial and Fungal Compositions in Rhizosphere Soil

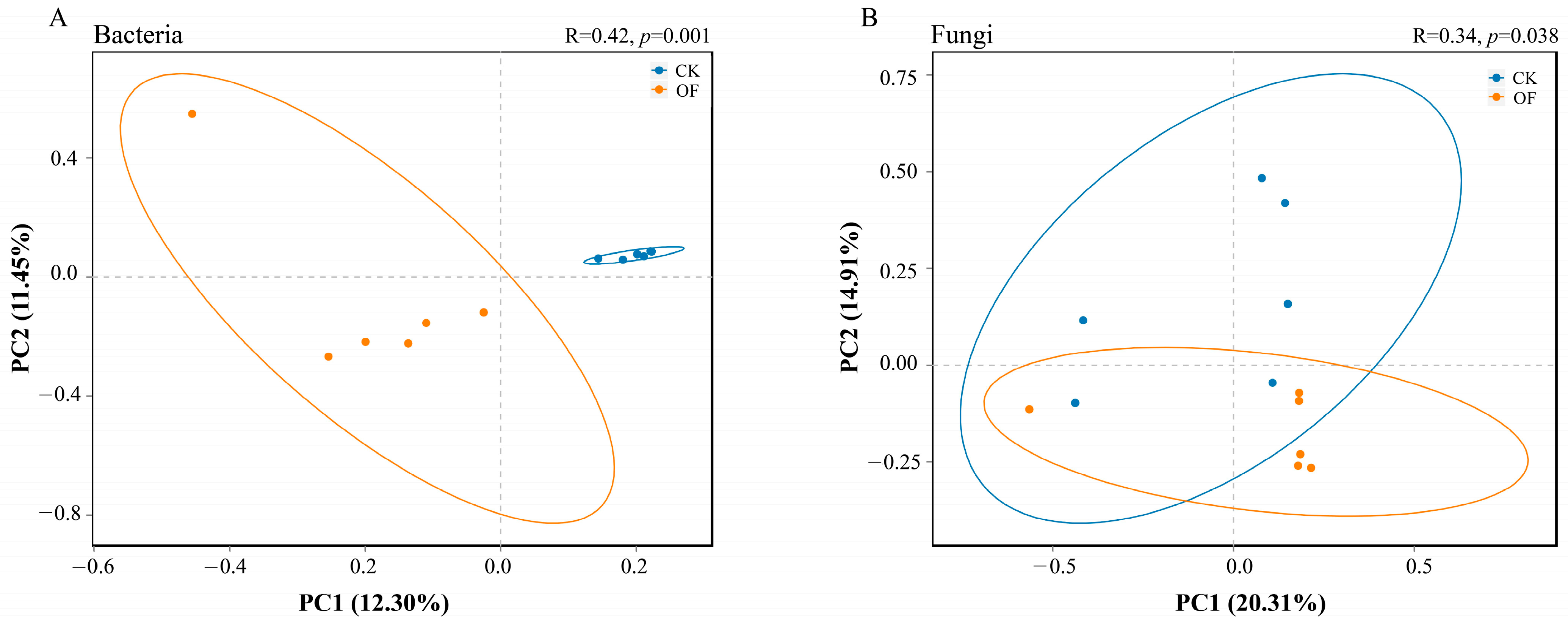

3.3. Diversity of Bacterial and Fungal Communities

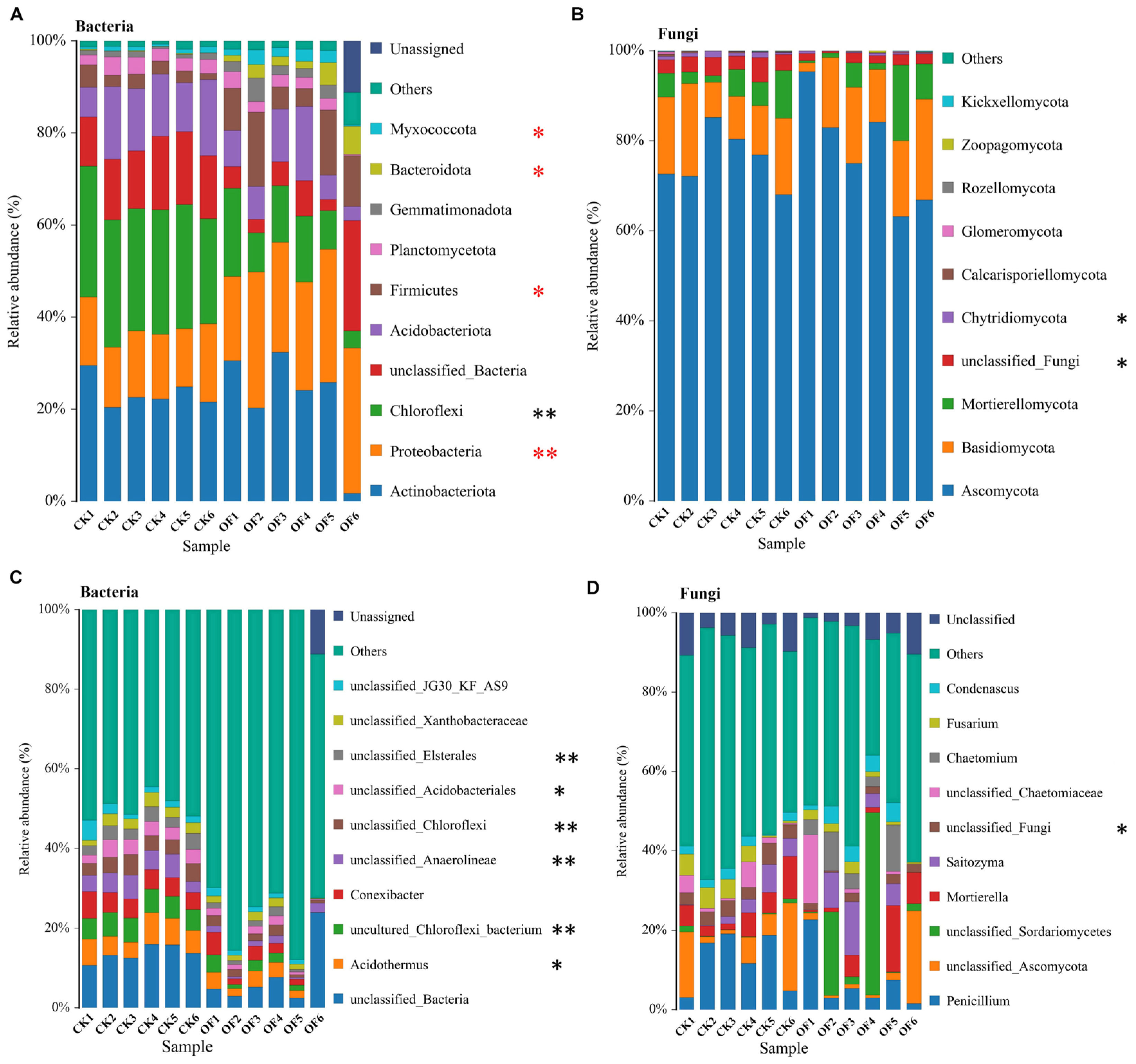

3.4. The Microbiome Structure of Bacteria and Fungi at the Phylum and Genus Levels

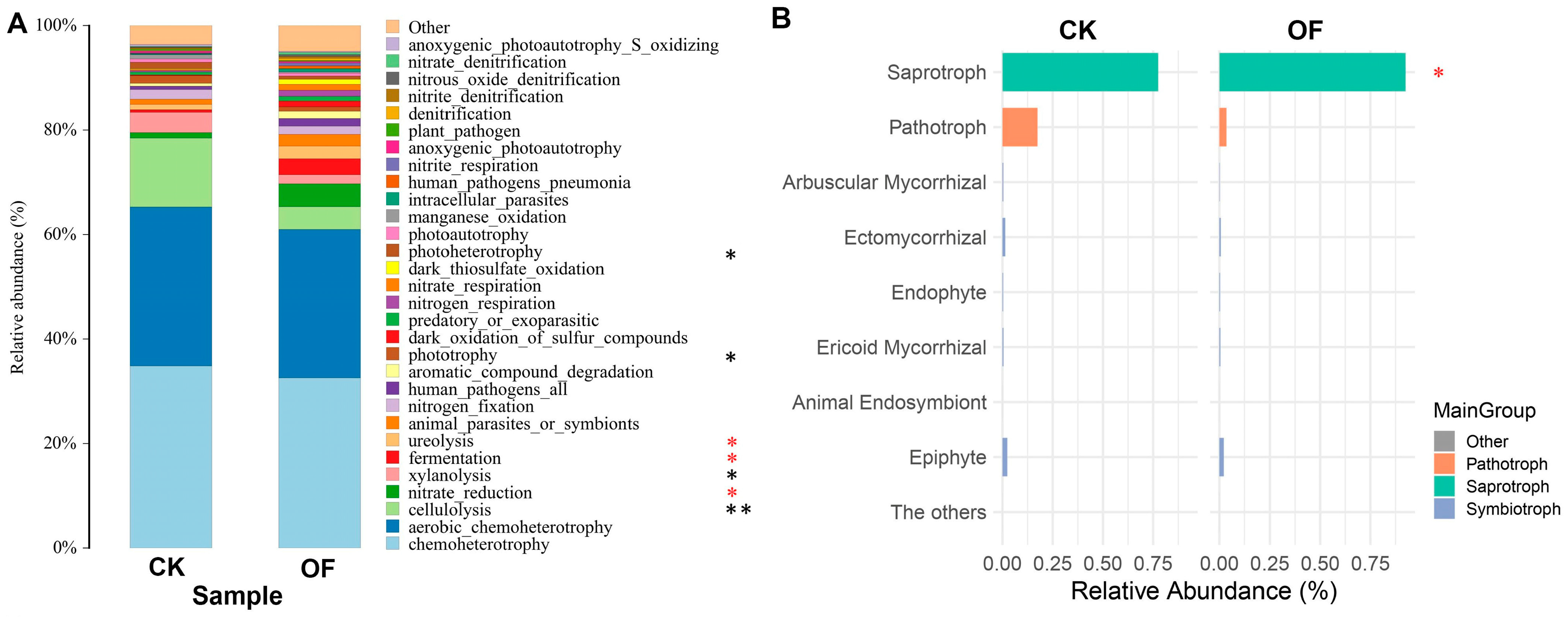

3.5. Functional Annotation of Bacteria and Fungi

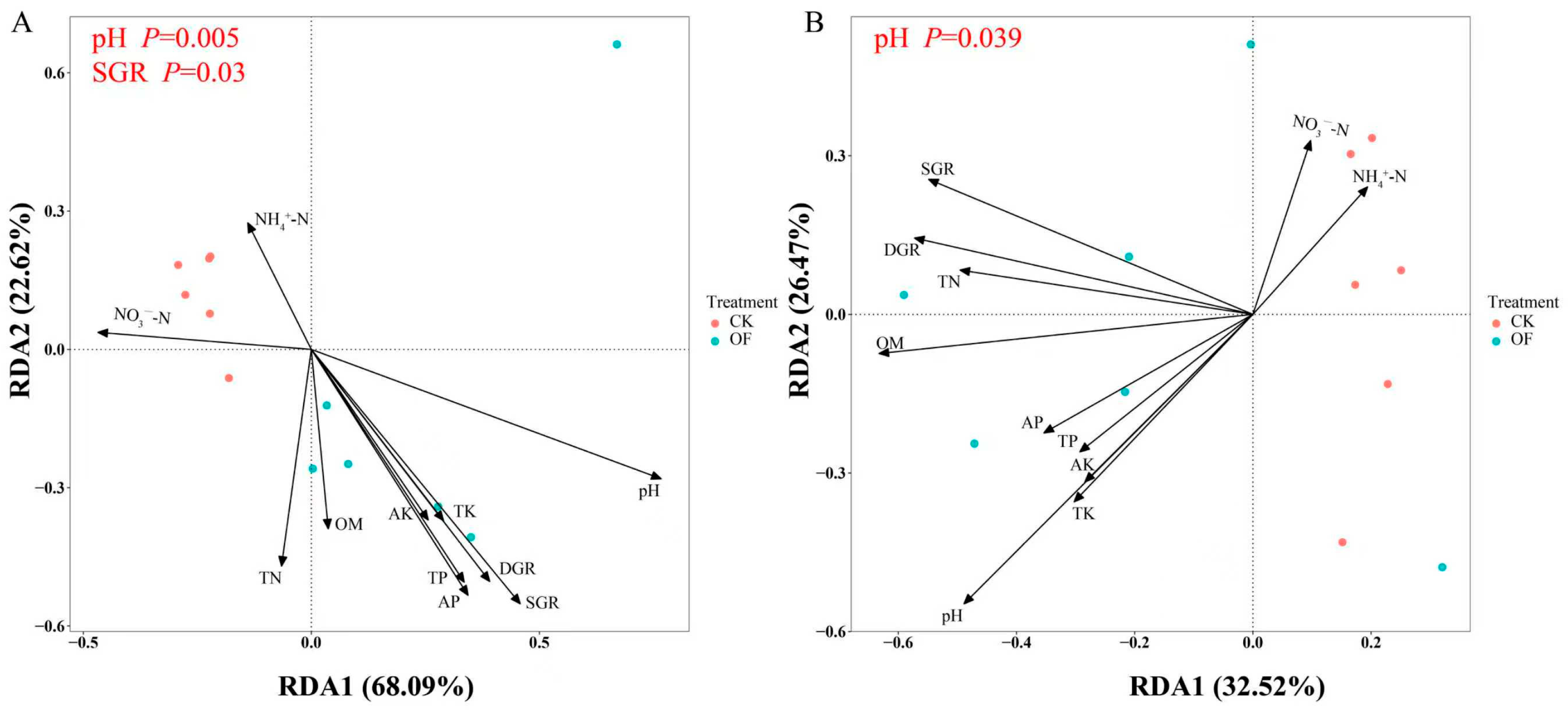

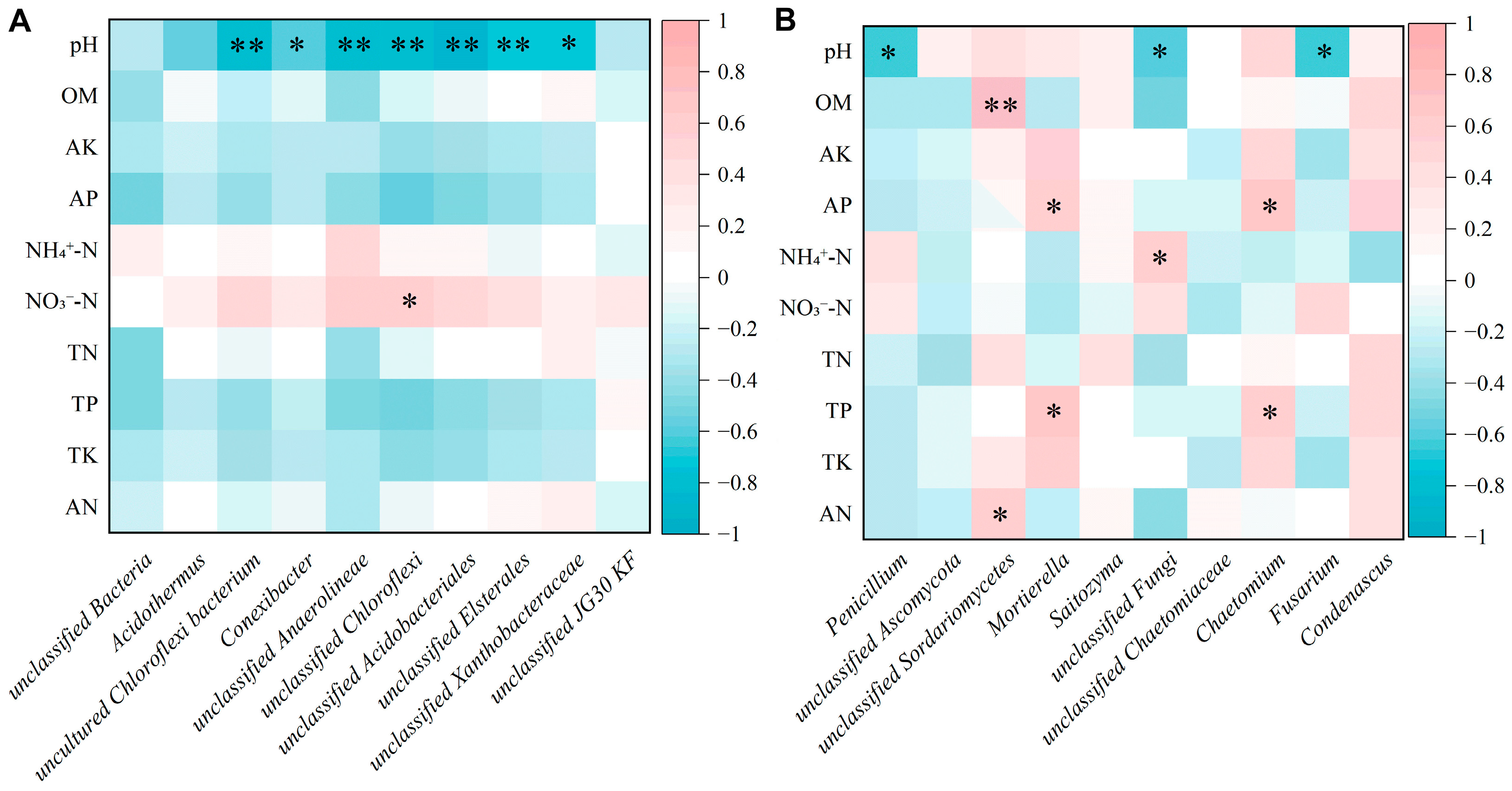

3.6. Relationship Between Soil Properties and Bacterial Structure and Function

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Short-Term Application of Cow Manure on Soil Properties and Seeding Growth

4.2. Effects of Cow Manure on Rhizosphere Microbial Diversity and Community Structure

4.3. Potential Mechanistic Insights into Microbial Functions and Soil Fertility

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, M.Y.; Li, H.T.; Wang, R.S.; Lan, S.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Sui, H.S.; Li, W.Z. Traditional Uses, Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of the Toona sinensis Plant. Molecules 2024, 29, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Ji, C.Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.X.; Wang, R.S.; Li, W.Z. Chemical Constituents of the Pericarp of Toona sinensis and Their Chemotaxonomic Significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2022, 104, 104458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.Q.; Ma, J.K.; Guo, C.C.; Zhong, Q.W.; Yu, W.W.; Jia, T.; Zhang, L. Insights into the Root Sprouts of Toona fargesii in a Natural Forest: From the Morphology, Physiology, and Transcriptome Levels. Forests 2024, 15, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Liu, K.F.; Li, Y.N.; Cheng, Q.Q.; Cao, W.; Luo, H.; Ma, J.K.; Zhang, L. Differential Metabolites Regulate the Formation of Chromatic Aberration in Toona fargesii Wood. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokkalingam, U. Learning Lessons from China’s Forest Rehabilitation Efforts: National Level Review and Special Focus on Guangdong Province; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Physicochemical Properties of a Red Soil Affected by the Longterm Application of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers. In Organic Fertilizers—From Basic Concepts to Applied Outcomes; Larramendy, M.L., Soloneski, S., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-953-51-2449-8. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yin, M.Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Tang, F.Y. Rice Husk Ash Addition to Acid Red Soil Improves the Soil Property and Cotton Seedling Growth. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Chowdhury, S.; Babin, D.; Sandmann, M.; Jacquiod, S.; Sommermann, L.; Sørensen, S.J.; Fliessbach, A.; Mäder, P.; Geistlinger, J.; Smalla, K.; et al. Effect of Long-term Organic and Mineral Fertilization Strategies on Rhizosphere Microbiota Assemblage and Performance of Lettuce. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 2426–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BharathKumar, S.; Prasanth, P.; Sreenivas, M.; Gouthami, P.; Sathish, G.; Jnanesha, A.C.; Kumar, S.R.; Gopal, S.V.; Sravya, K.; Kumar, A.; et al. Unveiling the Influence of NPK, Organic Fertilizers, and Plant Growth Enhancers on China Aster (Callistephus chinensis L.) CV. ‘Arka Kamini’ Seed Yield. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 227, 120778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, J.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Gillings, M.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Effects of Organic Fertilizers on Plant Growth and the Rhizosphere Microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e01719-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jo, N.Y.; Shim, S.Y.; Le, T.Y.L.; Jeong, W.Y.; Kwak, K.W.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, B.O.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, M.G.; et al. Impact of Organic Liquid Fertilizer on Plant Growth of Chinese Cabbage and Soil Bacterial Communities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, B.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, N.; Du, H.; Liu, F.; Yu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. Effects of Organic Fertilizer Replacement on the Microbial Community Structure in the Rhizosphere Soil of Soybeans in Albic Soil. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Chen, M.X.; Lam, P.Y.; Dini Andreote, F.; Dai, L.; Wei, Z. Multifaceted Roles of Flavonoids Mediating Plant-Microbe Interactions. Microbiome 2022, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Muhammad Aslam, M.; Gao, Y.Y.; Dai, L.; Hao, G.F.; Wei, Z.; Chen, M.X.; Dini Andreote, F. Microbiome-Mediated Signal Transduction within the Plant Holobiont. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phour, M.; Sehrawat, A.; Sindhu, S.S.; Glick, B.R. Interkingdom Signaling in Plant-Rhizomicrobiome Interactions for Sustainable Agriculture. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 241, 126589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenblum, E.; Massalha, H.; Aharoni, A. Plant–Microbe Interactions in the Rhizosphere via a Circular Metabolic Economy. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3168–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; He, H.; Cheng, L.; Li, S.; Wan, T.; Qin, J.; Li, J. Bio-Organic Fertilizers Enhance Yield in Continuous Cotton Cropping Systems Through Rhizosphere Microbiota Modulation and Soil Nutrient Improvement. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Shao, Q.; Fu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, J.; Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, J. Bio-Organic Fertilizers Modulate Therhizosphere Bacterial Community to Improve Plant Yield in Reclaimed Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1660229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Shi, J.; Gao, P.; Cai, Z.; Li, F. EM Biofertilizer and Organic Fertilizer Co-Application Modulate Vegetation-Soil-Bacteria Interaction Networks in Artificial Grasslands of Alpine Mining Regions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1659475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Semenov, V.M.; Van Bruggen, A.H.C. Long-Term Fertilization Rather than Plant Species Shapes Rhizosphere and Bulk Soil Prokaryotic Communities in Agroecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 154, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.H.; Du, H.; Gao, K.; Fang, Y.T.; Wang, K.L.; Zhu, T.B.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, D.J. Plant Species Diversity Enhances Soil Gross Nitrogen Transformations in a Subtropical Forest, Southwest China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 1364–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.K.; Aneja, K.R.; Rana, D. Current Status of Cow Dung as a Bioresource for Sustainable Development. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2016, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Sun, L.T.; Wang, Y.; Fan, K.; Xu, Q.S.; Li, Y.S.; Ma, Q.P.; Wang, J.G.; Ren, W.M.; Ding, Z.T. Cow Manure Application Effectively Regulates the Soil Bacterial Community in Tea Plantation. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Zhu Barker, X.; Decock, C. Effects of Organic Fertilizers on the Soil Microorganisms Responsible for N2O Emissions: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Singh, A.; Bala, J.; Chauhan, R.; Kumar, R.; Badiyal, A.; Walia, A. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria from Dung of Indigenous and Exotic Cow Breeds and Their Effect on the Growth of Pea Plant in Sustainable Agriculture. Biotechnol. Environ. 2025, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R. Analytical Methods for Soil and Agro-Chemistry; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.E. Chemical Analysis of Ecological Materials; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.L.; Page, A.L.; Helmke, P.A.; Loeppert, R.H. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 0-89118-825-8. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture Circular: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.R.; Gregorich, E.G. Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-429-12622-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, B.M. Usadel Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly Accurate OTU Sequences from Microbial Amplicon Reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME Improves Sensitivity and Speed of Chimera Detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J.E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C.J.; Brown, C.T.; Callahan, B.J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A.M.; Chase, J.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerfield, P.J.; Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. A Generalised Analysis of Similarities (ANOSIM) Statistic for Designs with Ordered Factors. Austral Ecol. 2021, 46, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.F.; He, Z.L.; Luo, F.; Zhou, J.Z. Molecular Ecological Network Analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, S.; Parfrey, L.W.; Doebeli, M. Decoupling Function and Taxonomy in the Global Ocean Microbiome. Science 2016, 353, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.W.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An Open Annotation Tool for Parsing Fungal Community Datasets by Ecological Guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, J.N.; Pop, M.; Bravo, H.C. Metastats: An Improved Statistical Method for Analysis of Metagenomic Data. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, P17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; Nagarajan, N.; Pop, M. Statistical Methods for Detecting Differentially Abundant Features in Clinical Metagenomic Samples. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Si, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Cao, K.; Wang, J.H. Various Green Manure-Fertilizer Combinations Affect the Soil Microbial Community and Function in Immature Red Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1255056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Jeong, S.T.; Das, S.; Kim, P.J. Composted Cattle Manure Increases Microbial Activity and Soil Fertility More Than Composted Swine Manure in a Submerged Rice Paddy. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.A.; McDonald, M.D.; Burke, J.; Robertson, I.; Coker, H.; Gentry, T.J.; Lewis, K.L. Influence of Fertilizer and Manure Inputs on Soil Health: A Review. Soil Secur. 2024, 16, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Shang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Yu, A. Drive Soil Nitrogen Transformation and Improve Crop Nitrogen Absorption and Utilization—A Review of Green Manure Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1305600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Lv, L.; Liu, D.; He, X.M.; Wang, W.T.; Feng, Y.Z.; Islam, M.d.S.; Wang, Q.J.; Chen, W.G.; Liu, Z.G.; et al. A Global Meta-Analysis of Animal Manure Application and Soil Microbial Ecology Based on Random Control Treatments. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, P.; Jing, Y. Effects of Long-Term Application of Organic Manure and Chemical Fertilizer on Soil Properties and Microbial Communities in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of North China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 993973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.P.; Banerjee, S.; He, J.Z.; Fan, J.B.; Wang, Z.H.; Wei, X.Y.; Hu, H.W.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, C.J.; Wan, S.; et al. Manure Application Increases Microbiome Complexity in Soil Aggregate Fractions: Results of an 18-Year Field Experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 307, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, H.; Xu, M.W.; Zhao, Y.G.; Shi, X.Y.; Shi, Y.; Wan, S.Q. Key Microbes in Wheat Maize Rotation Present Better Promoting Wheat Yield Effect in a Variety of Crop Rotation Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.Y.; Xia, L.L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.Q.; Chu, H.Y.; Liu, W.J.; Yuan, S.; Gao, X.; et al. Organic Amendments Enhance Soil Microbial Diversity, Microbial Functionality and Crop Yields: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.C.; Wu, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Peng, X.H.; Luo, Y.M. Divergent Soil Health Responses to Long-Term Inorganic and Organic Fertilization Management on Subtropical Upland Red Soil in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, N.; Zhu, C.; Xue, C.; Chen, H.; Duan, Y.H.; Peng, C.; Guo, S.W.; Shen, Q.R. Insight into How Organic Amendments Can Shape the Soil Microbiome in Long-Term Field Experiments as Revealed by Network Analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 99, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.K.; Tang, S.; Zhou, J.J.; Wanek, W.; Gregory, A.S.; Ge, T.; Marsden, K.A.; Chadwick, D.R.; Liang, Y.C.; Wu, L.H.; et al. Long-Term Manure and Mineral Fertilisation Drive Distinct Pathways of Soil Organic Nitrogen Decomposition: Insights from a 180-Year-Old Study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 207, 109840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Penton, C.R.; Ruan, Y.Z.; Shen, Z.Z.; Xue, C.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.R. Inducing the Rhizosphere Microbiome by Biofertilizer Application to Suppress Banana Fusarium Wilt Disease. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 104, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.Q.; Bi, J.J.; Qian, X.Y.; Peng, C.; Sun, M.M.; Wang, E.Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Zeng, X.; Feng, H.Q.; Song, A.L.; et al. Organic Manure Amendment Fortifies Soil Health by Enriching Beneficial Metabolites and Microorganisms and Suppressing Plant Pathogens. Agronomy 2025, 15, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Baquerizo, M.; Oliverio, A.M.; Brewer, T.E.; Benavent González, A.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K.; Fierer, N. A Global Atlas of the Dominant Bacteria Found in Soil. Science 2018, 359, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, B.M.; Stegen, J.C.; Kim, M.; Dong, K.; Adams, J.M.; Lee, Y.K. Soil pH Mediates the Balance between Stochastic and Deterministic Assembly of Bacteria. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SGR (%) | DGR (%) | pH | OM (mg kg−1) | AN (mg kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | AK (mg kg−1) | NH4+-N (mg kg−1) | NO3−-N (mg kg−1) | TN (mg kg−1) | TP (mg kg−1) | TK (mg kg−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 34.90 ± 5.49 | 90.88 ± 6.02 | 6.22 ± 0.024 | 11.56 ± 0.74 | 64.02 ± 5.28 | 17.02 ± 0.92 | 109.80 ± 32.31 | 5.62 ± 1.90 | 22.58 ± 3.49 | 632.98 ± 50.07 | 431.80 ± 22.99 | 19.67 ± 1.65 |

| OF | 73.51 ± 11.82 | 117.02 ± 12.16 | 6.36 ± 0.013 | 15.17 ± 1.77 | 77.73 ± 8.42 | 20.52 ± 2.44 | 182.18 ± 71.14 | 4.41 ± 0.40 | 10.60 ± 3.20 | 831.23 ± 121.90 | 507.68 ± 57.90 | 23.73 ± 3.58 |

| relative change (%) a | 110.63 | 28.76 | 2.25 | 31.23 | 21.42 | 20.56 | 65.92 | −21.53 | −53.06 | 31.32 | 17.57 | 20.64 |

| p value | 0.022 | 0.11 | 0.00083 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.044 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, G.; Tie, J.; Cao, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. Application of Cow Manure Enhances Soil Nutrients, Reshapes Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Promotes Growth of Toona fargesii Seedlings. Forests 2025, 16, 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121846

Xu L, Yang X, Zhang Y, Liao G, Tie J, Cao W, Yu Y, Zhang L. Application of Cow Manure Enhances Soil Nutrients, Reshapes Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Promotes Growth of Toona fargesii Seedlings. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121846

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ling, Xiao Yang, Yang Zhang, Guoxiang Liao, Jiaming Tie, Wen Cao, Yi Yu, and Lu Zhang. 2025. "Application of Cow Manure Enhances Soil Nutrients, Reshapes Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Promotes Growth of Toona fargesii Seedlings" Forests 16, no. 12: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121846

APA StyleXu, L., Yang, X., Zhang, Y., Liao, G., Tie, J., Cao, W., Yu, Y., & Zhang, L. (2025). Application of Cow Manure Enhances Soil Nutrients, Reshapes Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Promotes Growth of Toona fargesii Seedlings. Forests, 16(12), 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121846