Chemical Modification of Pachira aquatica Oil for Bio-Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of the Fruits and Extraction of the Oil

2.2. Characterization of Pachira aquatica Oil

2.3. Transesterification of the P. aquatica Oil

2.4. Production of Bioadhesive

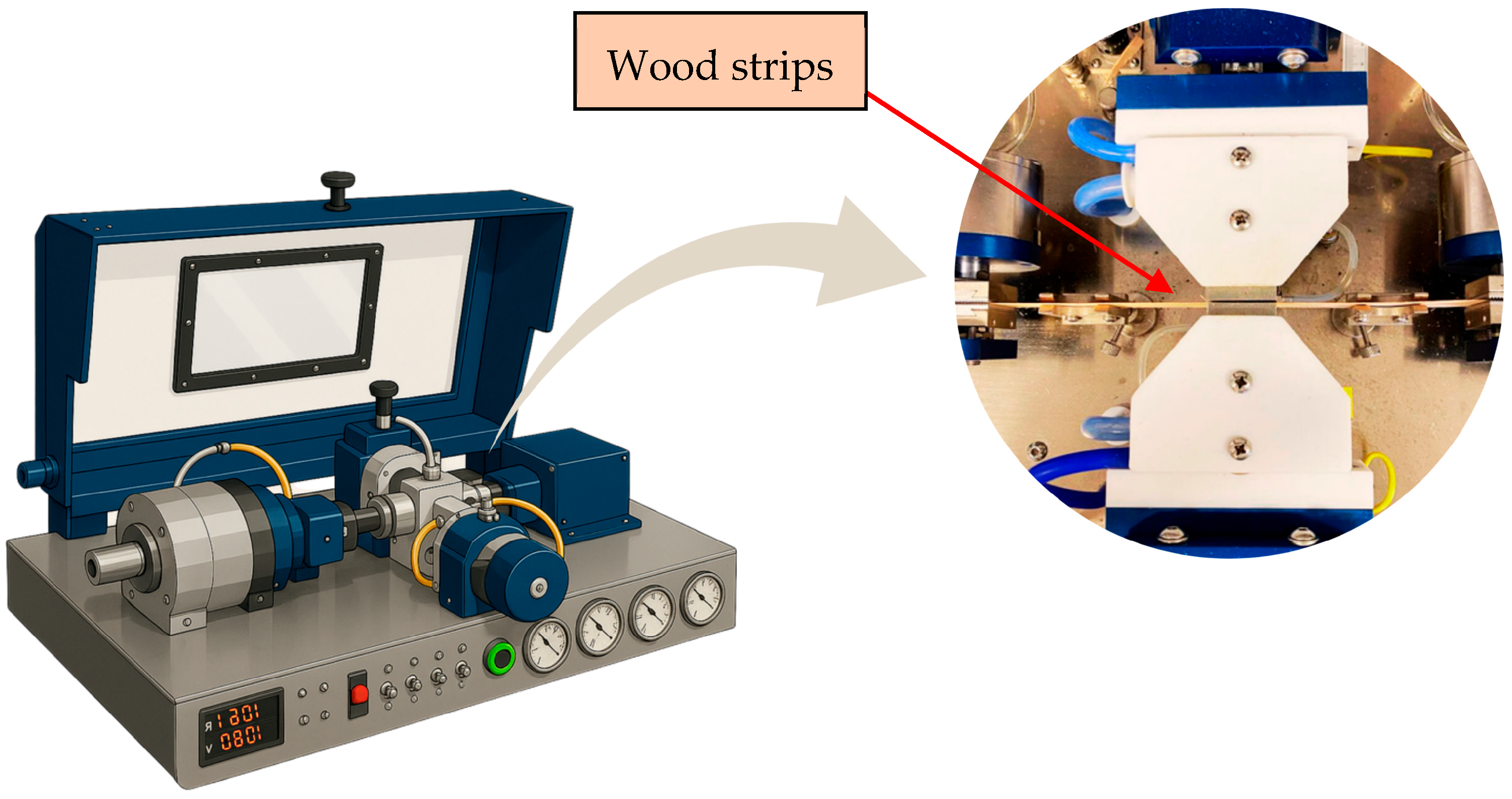

2.5. Adhesion Test with the Bioadhesive

2.6. Experimental Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

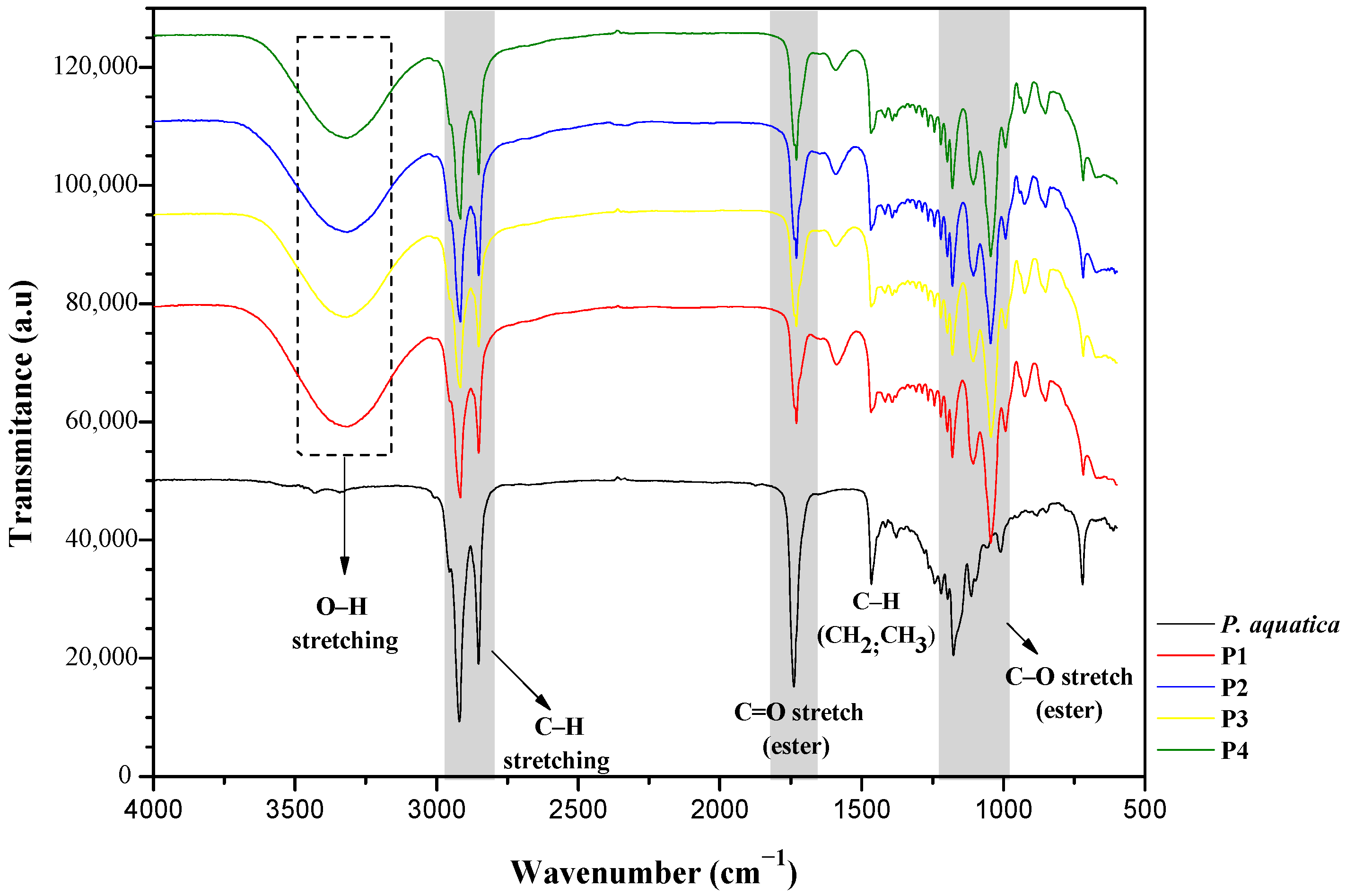

3.1. P. aquatica Oil Characteristics

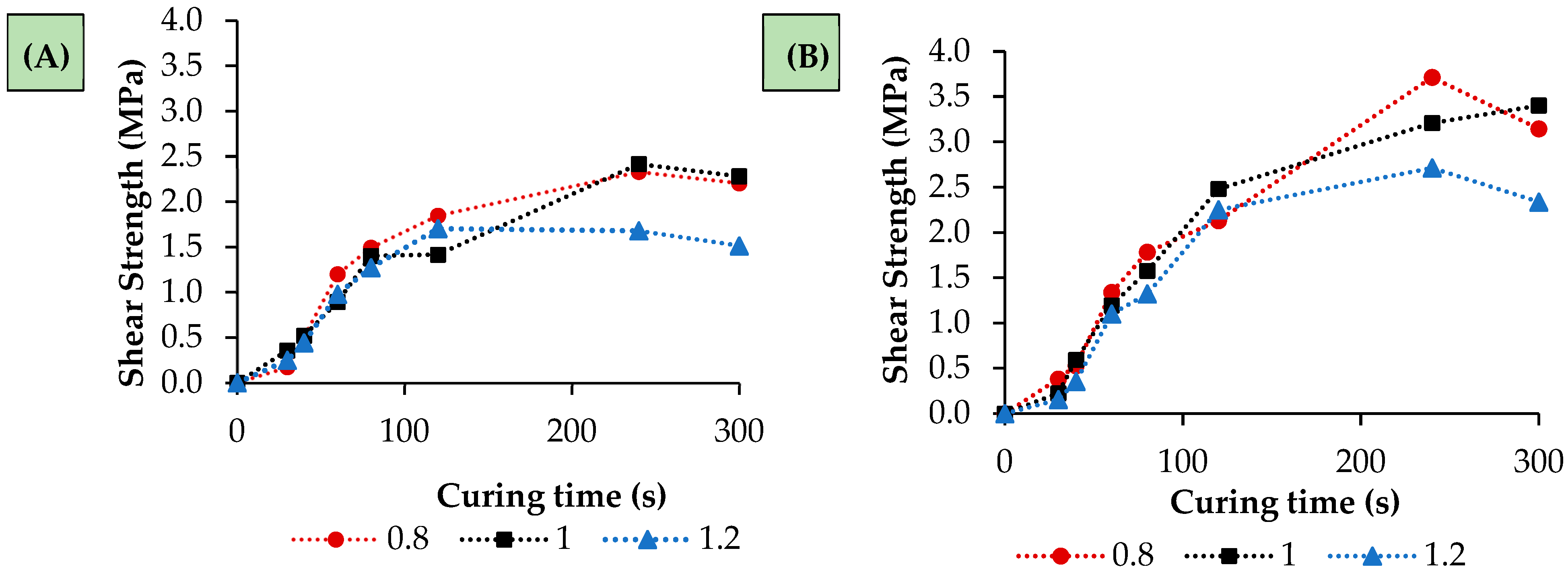

3.2. Performance of the Bioadhesives Based on the P. aquatica Oil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunky, M. Naturally-Based Adhesives for Wood and Wood-Based Panels. In Biobased Adhesives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 517–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmilä, V.; Adamopoulos, S.; Karlsson, O.; Kumar, A. Development of Sustainable Bio-Adhesives for Engineered Wood Panels—A Review. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 38604–38630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluyor, E.O.; Obahiagbon, K.O.; Ori-Jesu, M. Biodegradation of Vegetable Oils: A Review. Sci. Res. Essay 2009, 4, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Ciastowicz, Ż.; Pamuła, R.; Bobak, Ł.; Białowiec, A. Characterization of Vegetable Oils for Direct Use in Polyurethane-Based Adhesives: Physicochemical and Compatibility Assessment. Materials 2025, 18, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciastowicz, Ż.; Pamuła, R.; Białowiec, A. Utilization of Plant Oils for Sustainable Polyurethane Adhesives: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahdan, S.N.; Hirzin, R.S.F.N. Pre-Treatment of Used Cooking Oil Followed by Transesterification Reaction in the Production of Used Cooking Oil-Based Polyol. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 18, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Hu, S. Bio-Based Polyols and Polyurethanes, 1st ed.; Springer Briefs in Molecular Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaikade, D.S.; Sabnis, A.S. Polyurethane Foams from Vegetable Oil-Based Polyols: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 2239–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Liu, G.; Curtis, J.M. Characterization of Canola Oil Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2011, 31, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.K.; Kirpluks, M.; Priya, A.; Kaur, G. Conversion of Food Waste-Derived Lipid to Bio-Based Polyurethane Foam. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briede, S.; Platnieks, O.; Barkane, A.; Sivacovs, I.; Leitans, A.; Lungevics, J.; Gaidukovs, S. Tailored Biobased Resins from Acrylated Vegetable Oils for Application in Wood Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.; Silva, S.; Costa Júnior, S.; Bezerra, G. Análise Sensorial de Produto Elaborado a Partir Da Farinha de Munguba (Pachira aquatica Aubl.). In Proceedings of the VI Congresso Latino-Americano de Agroecologia X Congresso Brasileiro de Agroecologia, V Seminário de Agroecologia do Distrito Federal e Entorno, Brasília, DF, Brazil, 12–15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.L.A.; Bora, P.S.; Azevedo, C.C. Caracterização Química Parcial Das Proteínas Das Amêndoas Da Munguba (Pachira aquatica Aubl). Rev. Inst. Adolfo Lutz 2010, 69, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, A.L.; Escudeiro, A. Pachira aquatica (Bombacaceae) Na Obra “História Dos Animais e Árvores Do Maranhão” de Frei Cristóvão de Lisboa. Rodriguésia 2002, 53, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, T.S.S.; Boas, J.C.V.; Souza, M.L.F.S.; Oliveira, M.V.L.; Cordoba, L.B.; Neto, J.A.B.; Vargas, M.O.F. Análise Comparativa Das Propriedades Funcionais de Munguba (Pachira aquatica Aubl.) e Seus Alternativos Alimentares Possíveis. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 41577–41588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, N.; Luzia, D.M.M. Caracterização Do Óleo Das Sementes de Pachira aquatica Aublet Para Aproveitamento Alimentar. Acta Amaz. 2012, 42, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatorre, F.M.; Cupertino, G.F.M.; Pereira, A.K.S.; Souza, E.C.; Silva, Á.M.; Ucella Filho, J.G.M.; Saloni, D.; Profeti, L.P.R.; Profeti, D.; Dias Júnior, A.F. Photoluminous Response of Biocomposites Produced with Charcoal. Polymers 2023, 15, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.R.; Barros-Timmons, A.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Pinto, P.C.R. Effect of Different Catalysts on the Oxyalkylation of Eucalyptus Lignoboost® Kraft Lignin. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulyanska, Y.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Esteves, B.; Guiné, R.; Domingos, I. FTIR Monitoring of Polyurethane Foams Derived from Acid-Liquefied and Base-Liquefied Polyols. Polymers 2024, 16, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arniza, M.Z.; Hoong, S.S.; Idris, Z.; Yeong, S.K.; Hassan, H.A.; Din, A.K.; Choo, Y.M. Synthesis of Transesterified Palm Olein-Based Polyol and Rigid Polyurethanes from This Polyol. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2015, 92, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, N.A.; Pereira, J.; Ferra, J.; Cruz, P.; Martins, J.; Magalhães, F.D.; Mendes, A.; Carvalho, L.H. Evaluation of Bonding Performance of Amino Polymers Using ABES. J. Adhes. 2014, 90, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7998-19; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Effect of Temperature on the Cohesive Strength Development of Adhesives Using Lap Shear Bonds Under Tensile Loading. American Society for Testing and Material: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Esteves, B.; Martins, J.; Martins, J.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Vicente, J.; Domingos, I. Liquefied Wood as a Partial Substitute of Melamine-Urea-Formaldehyde and Urea-Formaldehyde Resins. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2015, 17, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Rodrigues, A.P.; Pereira, G.A.; Tomé, P.H.F.; Arruda, H.S.; Eberlin, M.N.; Pastore, G.M. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Monguba (Pachira aquatica) Seeds. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.F. Caracterização Química Do Óleo Extraído Da Pachira aquatica Aubl. Periód. Tchê Quím. 2008, 5, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunky, M. Wood Adhesives Based on Natural Resources: A Critical Review: Part IV. Special Topics. In Progress in Adhesion and Adhesives; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 761–840. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, D.J.; Pokhrel, G.; Collins, A. Adhesion Theories in Naturally-based Bonding. In Biobased Adhesives; Dunky, M., Mittal, K.L., Eds.; Jhon Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović-Grmuša, I.; Rančić, M.; Tešić, T.; Stupar, S.; Milošević, M.; Gržetić, J. Bio-Epoxy Resins Based on Lignin and Tannic Acids as Wood Adhesives—Characterization and Bonding Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, C.M.; Orakwue, C.C.; Ani, O.N.; Chinedu, M.P.; Kadurumba, C.H.; Ahaneku, I.E. Methyl Ester Production from Cotton Seed Oil via Catalytic Transesterification Process; Characterization, Fatty Acids Composition, Kinetics, and Thermodynamics Study. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 5, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chang, X.; Shi, L.; Lv, S.; Zhang, Y. Castor Oil-Based Adhesives: A Comprehensive Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 209, 117924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, T.A.; Lopes, T.I.B.; Nazario, C.E.D.; Oliveira, S.L.; Alcantara, G.B. Vegetable Oils: Are They True? A Point of View from ATR-FTIR, 1H NMR, and Regiospecific Analysis by 13C NMR. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavia, D.L.; Lampman, G.M.; Kriz, G.S.; Vyvyan, J.R. Introdução à Espectroscopia, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning, Ed.: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fontalvo-Gómez, M.; Colucci, J.A.; Velez, N.; Romañach, R.J. In-Line Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman Spectroscopy Coupled with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for in Situ Evaluation of the Transesterification Reaction. Appl. Spectrosc. 2013, 67, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borówka, G.; Semerjak, G.; Krasodomski, W.; Lubowicz, J. Purified Glycerine from Biodiesel Production as Biomass or Waste-Based Green Raw Material for the Production of Biochemicals. Energies 2023, 16, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Pai, S.D.K.R.; Reghunath, B.S.; Pinheiro, D. Unveiling Cutting Edge Innovations in the Catalytic Valorization of Biodiesel Byproduct Glycerol into Value Added Products. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202204501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavafer, A.; Ball, M.C. Good Vibrations: Raman Spectroscopy Enables Insights into Plant Biochemical Composition. Funct. Plant Biol. 2022, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Ferreira, E.N.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; Kebir, N.; Leveneur, S. Epoxidation Showdown: Unveiling the Kinetics of Vegetable Oils vs Their Methyl Ester Counterparts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 18849–18860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Karak, N. Effect of the NCO/OH Ratio on the Properties of Mesua ferrea L. Seed Oil-modified Polyurethane Resins. Polym. Int. 2006, 55, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kalita, H.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Synthesis and Characterization of Vegetable Oil Based Polyurethane Derived from Low Viscous Bio Aliphatic Isocyanate: Adhesion Strength to Wood-Wood Substrate Bonding. Macromol. Res. 2017, 25, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Pereira, J.; Coelho, C.; Ferra, J.; Mena, P.; Magalhães, F.; Carvalho, L. Adhesive Bond Strength Development Evaluation Using ABES in Different Lignocellulosic Materials. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2013, 47, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.A.; Ferra, J.; Martins, J.; Coelho, C.; Pereira, J.; Cruz, P.; Magalhães, F.; Carvalho, L. Impact of Thermal Treatment on Bonding Performance of UF/PVAc Formulations. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2014, 5, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, P.N.; Yarmohamadi, M.; Hasanzadeh, R.; Nuri, S. Preparation of Polyurethane Wood Adhesives by Polyols Formulated with Polyester Polyols Based on Castor Oil. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 68, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somani, K.P.; Kansara, S.S.; Patel, N.K.; Rakshit, A.K. Castor Oil Based Polyurethane Adhesives for Wood-to-Wood Bonding. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2003, 23, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Lu, Q.; Tan, W.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. The Influence of the NCO/OH Ratio and the 1,6-Hexanediol/Dimethylol Propionic Acid Molar Ratio on the Properties of Waterborne Polyurethane Dispersions Based on 1,5-Pentamethylene Diisocyanate. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2019, 13, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-X.; Dou, R.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y.-X.; Leng, L.-J.; Osman, S.M.; Luque, R. Bio-Adhesives Derived from Sewage Sludge via Hydrothermal Carbonization: Influence of Aqueous Phase Recycling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Singh, P. Kinetic Study of Polyurethane Reaction between Castor Oil/TMP Polyol and Diphenyl Methane Diisocyanate in Bulk. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2006, 55, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palle, I.; Lodin, V.; Mohd Yunus, A.A.; Lee, S.H.; Md Tahir, P.; Hori, N.; Antov, P.; Takemura, A. Effects of NCO/OH Ratios on Bio-Based Polyurethane Film Properties Made from Acacia mangium Liquefied Wood. Polymers 2023, 15, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.R.; Gama, N.; Magina, S.; Barros-Timmons, A.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Pinto, P.C.O.R. Polyurethane Adhesives Based on Oxyalkylated Kraft Lignin. Polymers 2022, 14, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, S.; Setiawan, I.P.; Pusbanarum, D.; Antov, P.; Iswanto, A.H.; Kristak, L.; Lee, S.H.; Lubis, M.A.R. Adhesion and Cohesion Performance of Polyurethane Made of Bio-Polyol Derived from Modified Waste Cooking Oil for Exterior Grade Plywood. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2400225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Prado, A.; Hohl, D.K.; Balog, S.; Espinosa, L.M.; Weder, C. Plant Oil-Based Supramolecular Polymer Networks and Composites for Debonding-on-Demand Adhesives. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascano, D.; Gomez-Caturla, J.; Garcia-Sanoguera, D.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Ivorra-Martinez, J. Optimizing Biobased Thermoset Resins by Incorporating Cinnamon Derivative into Acrylated Epoxidized Soybean Oil. Mater. Des. 2024, 243, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, O.; Heyd, B.; Broyart, B.; Castillo, R.; Maillard, M.-N. Oxidative Reactivity of Unsaturated Fatty Acids from Sunflower, High Oleic Sunflower and Rapeseed Oils Subjected to Heat Treatment, under Controlled Conditions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szori, M.; Csizmadia, I.G.; Viskolcz, B. Nonenzymatic Pathway of PUFA Oxidation. A First-Principles Study of the Reactions of OH Radical with 1,4-Pentadiene and Arachidonic Acid. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Liang, L.; Li, L. Effect of Fatty Acids on Vegetable-Oil-Derived Sustainable Polyurethane Coatings for Controlled-Release Fertilizer. Coatings 2024, 14, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Vega, M.J.; Martínez-Force, E.; Garcés, R. Lipid Characterization of Seed Oils from High-palmitic, Low-palmitoleic, and Very High-stearic Acid Sunflower Lines. Lipids 2005, 40, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peptu, C.; Diaconu, A.-D.; Danu, M.; Peptu, C.A.; Cristea, M.; Harabagiu, V. The Influence of the Hydroxyl Type on Crosslinking Process in Cyclodextrin Based Polyurethane Networks. Gels 2022, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Z.S.; Zhang, W.; Zlatanić, A.; Lava, C.C.; Ilavskyý, M. Effect of OH/NCO Molar Ratio on Properties of Soy-Based Polyurethane Networks. J. Polym. Environ. 2002, 10, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.I.A.M.; Bonnia, N.N.; Hirzin, R.S.F.N.; Ali, E.S.; Zawawi, E.Z.E. Effect of NCO/OH Ratio on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Castor-Based Polyurethane Grouting Materials. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1349, 012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jašek, V.; Figalla, S. Vegetable Oils for Material Applications–Available Biobased Compounds Seeking Their Utilities. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, J.M. Avaliação da Toxicidade, Genotoxicidade e Mutagenicidade do Óleo da Semente de Pachira aquatica Aublet. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, T.G. Potencial Nutricional das Amêndoas de Pachira aquatica Aubl. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, J.C.J.; Gucciardi, E.; Cavallaro, S. Chemical Transformations of Renewable Lubricant Feedstocks. In Biolubricants; Bart, J.C.J., Gucciardi, E., Cavallaro, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 249–350. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Lu, X.; Savage, P.E. Catalytic Hydrothermal Deoxygenation of Palmitic Acid. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharyya, D.K. Utilization of High-melting Palm Stearin in Lipase-catalyzed Interesterification with Liquid Oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1997, 74, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, J.A.; Bautista, L.F.; Morales, G.; Iglesias, J.; Briones, D. Biodiesel Production with Heterogeneous Sulfonic Acid-Functionalized Mesostructured Catalysts. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Shi, S.Q. Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polymeric Diphenylmethane Diisocyanate/Bio-Oil Adhesive System. For. Prod. J. 2012, 62, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN 205; Adhesives—Wood Adhesives for Non-Structural Applications: Determination of Tensile Shear Strength of Lap Joints. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

| Polyol | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Molar Ratio (Glycerol/Oil) | Catalyst (%)-(NaOH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 180 | 6 | 6:1 | 2.0 |

| P2 | 200 | 6 | 6:1 | 2.0 |

| P3 | 200 | 6 | 18:1 | 2.0 |

| P4 | 200 | 6 | 13:1 | 2.0 |

| Bioadhesives | Polyol Amount (mL)/Isocyanate (mL)— (NCO/OH Ratio) | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| P3-T1 * | 3:4.0—(1.00) | 105 |

| P3-T2 | 3:3.2—(0.80) | 105 |

| P3-T3 | 3:4.8—(1.20) | 105 |

| P3-T4 | 3:3.0—(0.75) | 115 |

| P3-T5 | 3:3.0—(0.75) | 95 |

| P3-T6 | 3:3.0—(0.75) | 140 |

| P3-T7 | 3:2.4—(0.60) | 105 |

| P4-T1 | 3:4.5—(1.00) | 105 |

| P4-T2 | 3:3.6—(0.80) | 105 |

| P4-T3 | 3:5.4—(1.20) | 105 |

| Bioadhesives | Shear Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|

| P3-T1 | 1.33 (0.80) a * |

| P3-T2 | 1.39 (0.82) a * |

| P3-T3 | 1.12 (0.59) a * |

| P3-T4 | 1.75 (0.78) a * |

| P3-T5 | 0.83 (0.71) b * |

| P3-T6 | 1.91 (0.38) a * |

| P3-T7 | 1.22 (0.66) a * |

| P4-T1 | 1.81 (1.25) a * |

| P4-T2 | 1.86 (1.25) a * |

| P4-T3 | 1.46 (1.00) a * |

| Pure oil (Control) | 0.30 (0.28) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, E.; Esteves, B.; Domingos, I.; Almeida, M.; Araújo, B.; Chaves, I.; Fassarella, M.; Lelis, R.; Paes, J.; Carvalho, L.; et al. Chemical Modification of Pachira aquatica Oil for Bio-Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. Forests 2025, 16, 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121843

Silva E, Esteves B, Domingos I, Almeida M, Araújo B, Chaves I, Fassarella M, Lelis R, Paes J, Carvalho L, et al. Chemical Modification of Pachira aquatica Oil for Bio-Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121843

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Emilly, Bruno Esteves, Idalina Domingos, Margarida Almeida, Bruno Araújo, Izabella Chaves, Michelângelo Fassarella, Roberto Lelis, Juarez Paes, Luísa Carvalho, and et al. 2025. "Chemical Modification of Pachira aquatica Oil for Bio-Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives" Forests 16, no. 12: 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121843

APA StyleSilva, E., Esteves, B., Domingos, I., Almeida, M., Araújo, B., Chaves, I., Fassarella, M., Lelis, R., Paes, J., Carvalho, L., & Gonçalves, F. (2025). Chemical Modification of Pachira aquatica Oil for Bio-Based Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. Forests, 16(12), 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121843