Abstract

WUSCHEL-related homeobox plays important roles in diverse biological processes, such as plant growth and development, hormonal homeostasis, and abiotic stress adaptation. Lycium barbarum (goji berry) is a model species for studying regeneration in woody plants; however, the LbWOX gene family has yet to be characterized. This work reports a genomic and transcriptomic characterization of the LbWOX genefamily in Lycium barbarum. Eighteen LbWOX genes were identified with uneven distribution across eight chromosomes. These genes were grouped into three subfamilies via phylogenetic classification. Additionally, cis-regulatory element characterization suggests that the expression of LbWOX genes is mainly influenced by plant differentiation, phytohormones, and various abiotic stresses. Expression profiles derived from RNA-Seq of root, stem, leaf, and fruit revealed that all eighteen genes were expressed. Notably, LbWOX1 and LbWOX4 were highly expressed in leaves, suggesting a role in leaf growth and a potential to enhance differentiation capacity. Furthermore, LbWOX4 showed elevated expression in roots and stems, an association with vascular development that implicates them as prime candidates for enhancing adventitious root formation during cutting propagation. This work represents the first genome-wide analysis of the LbWOX genes, integrating high-throughput RNA-Seq to characterize the function of all eighteen identified members. Our research provides further insights for future studies of LbWOX gene functions in wolfberry.

1. Introduction

Goji (Lycium barbarum L.) is a widely cultivated woody perennial species in Solanaceae family. It serves as an excellent pioneer species for restoring saline–alkali soils in northwest China. This is due to its strong stress tolerance. The species is cultivated for its fruit (goji or wolfberry). It is known for various health benefits. These include nourishing the blood [1], improving vision [2], and providing antioxidant [3] and anti-inflammatory [4] effects. Goji berry holds a prominent position in traditional medicine across Asia. Conventional methods to improve goji yield and quality often rely on hybridization. This process crosses stress-tolerant lines with nutrient-rich varieties. However, such breeding is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. As a result, genetic transformation has been adopted. This approach helps modify L. barbarum var Qingqi 1. It offers a new way to develop improved germplasm.

However, genetic transformation faces major challenges. These include strong genotype dependence and low organogenesis efficiency. Studies in other species indicate that the WOX gene family could help overcome these issues. The WOX genes are plant-specific regulators. These include WUSCHEL (WUS) and WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) genes. They all contain a conserved homeobox area. In 1996, Laux et al. first discovered the WUS transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana [5,6]. Since then, researchers have identified 15 AtWOX members. These members are grouped into three clades. WOX transcription factors function as central regulators of plant development. They are involved in root and shoot development and also help regulate hormones and respond to abiotic stress [7].

In root development, for example, Populus PtWOX5 overexpression limits cell division. It also suppresses differentiation-related genes. These changes increase lateral root formation. However, they also slow lateral root growth [8]. In transgenic hybrid poplar, ectopic expression of PtoWOX4a and PtoWOX5a enhances adventitious root regeneration [9]. Transgenic A. thaliana expressing lotus genes NnWOX1-1 and NnWOX4-3 forms longer roots. These plants also produce more roots than their wild-type counterparts [10]. Overexpression of PeWOX11a or PeWOX11b enhances root development on cuttings. It also promotes ectopic root formation in region parts of poplar [11]. Additionally, AtWOX11/12 activate AtWOX5/7, which in turn drives the initiation of root primordia. This activation promotes root primordium initiation [12]. Overexpression of PeWOX11a/11b enhances root development on cuttings [11].

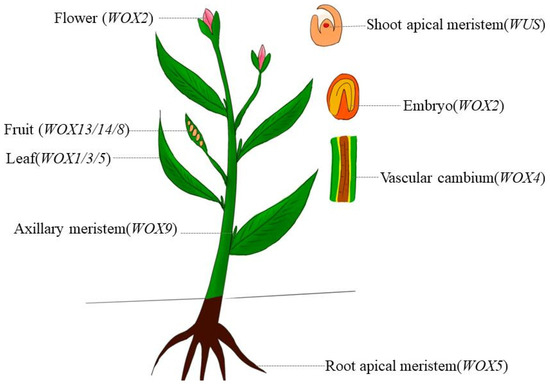

WOX transcription factors are essential for shoot apical meristem (SAM) and shoot regeneration in many species. For example, genes like SsuWOX1 [13], TaWOX5 [14], and GmWOX18 [15] increase regeneration capacity. Others, such as WUS2, BABYBOOM (BBM) [16], and LhWOX5 [17] enhance shoot differentiation. StWOX9 [18], OsWOX5 [19], and MtWOX5 [20] support floral or nodule meristem formation. In contrast, MdWOX11 inhibits shoot formation in apple [21]. During regeneration, genes including D-TYPE CYCLIN (CYCD3-1), SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), and WUS are upregulated in tomato in specific patterns [22]. Cytokinin influences this process through WUS, CLAVATA3 (CLV3) [23,24]. Additionally, TaMOC1 may help regulate spike development in wheat (Figure 1) [25].

Figure 1.

The WOX gene family functions in plants.

WOX genes also help plants cope with abiotic stress and help regulate hormones. For example, GhWOX4 improves drought tolerance in cotton by promoting vascular growth [26]. PagWOX11/12a [27], JrWOX11 [28], HvWOX8 [29], and VdWOX8 [30] enhance salt tolerance via reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging or osmotic adjustment. In rice, OsWOX11 provides tolerance to potassium deficiency [31]. Under cold stress, PkWOX11 expression increases at 10 °C [32]. However, most WOX genes in pineapple are downregulated after chilling [33]. Low temperatures can also delay wheat spike development by affecting abscisic acid (ABA) and WOX6 [34]. Rice OSWOX11 helps initiate crown roots by directly suppressing RESPONSE REGULATOR gene (OsRR2). OsRR2 is a type-A negative regulator of cytokinin signaling. This repression occurs together with the transcription factor APETALA2 (AP2) [35,36].

The WOX genes regulate plant regeneration and organogenesis through several key mechanisms. First, WOX genes can suppress negative regulators to improve regeneration. For example, WOX13 suppresses shoot regeneration in A. thaliana. Knocking out WOX13 speeds up regeneration, suggesting new strategies for tissue culture [37]. Second, they activate positive regulators to promote organ formation. Overexpression of WOX5 enhances root apical meristem regeneration by increasing callus cell pluripotency [38,39]. Third, WOX proteins interact with co-factors to overcome genotype limitations. Co-expressing WUS with BBM helps bypass genotype restrictions in maize, improving transformation efficiency [16]. OsBBM1 initiates embryogenesis, while OsWOX9A stabilizes chromatin and activates regenerative genes without fertilization [40]. WOX/BBM transcription factors counteract epigenetic repression by coordinating DNA demethylation and histone modifications. These changes enable chromatin remodeling, which supports regeneration [41,42,43]. Fourth, WOX genes can modulate hormone pathways to promote organogenesis. In regulating leaf blade expansion, NsWOX9 binds to the NsCKX3 promoter to modulate cytokinin levels, thereby balancing cell proliferation and differentiation [44,45].

Although WOX genes are well-studied in many species, their roles in L. barbarum remain unknown. Previous research has focused on their functions in shoot and root development and hormone signaling, and the enhancement of genetic transformation efficiency. However, no study has identified or characterized WOX genes in L. barbarum. To address this unexplored area, we performed bioinformatic analysis of WOX transcription factors in L. barbarum. This included characterizing the LbWOX genes, mapping their chromosomal locations, conducting phylogenetic and multiple sequence analyses, identifying gene structures, conserved motifs, and three-dimensional structures, performing synteny analysis, and investigating their expression patterns. This helped us understand their functional roles and tissue-specificity. Our results provide foundational insights and thus offer a resource for leveraging the LbWOX gene family to enhance genetic transformation efficiency and advance molecular breeding in L. barbarum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of LbWOX Genes

The genome assembly files (accession number ASM1917538v2) of L. barbarum were retrieved from the NCBI [46]. We obtained the protein sequences of AtWOX genes from TAIR (accession number GCF_000001735.4) (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Using these as queries, we screened LbWOX domain-containing proteins in L. barbarum by performing a BLASTP [47] search against its complete protein set (E-value cutoff of <1 × 10−5). We also used the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) model of the WOX domain (PF00046) from the Pfam [48] database to screen the L. barbarum protein database. Candidate WOX genes were identified using HMMER v3.0 (http://hmmer.org/, accessed on 15 May 2025) with an E-value cutoff of <1 × 10−5 against the L. barbarum proteome. Redundant and non-specific conserved WOX domains were manually removed after cross-referencing with NCBI Conserved Domain Search (CD-Search) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/, accessed on 15 May 2025), and the remaining validated genes are classified as LbWOX genes in this study. We characterized the physicochemical properties of the LbWOX proteins using the ExPASy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 15 May 2025), including chromosome, start/end position (S/EP), amino acid length (AAL), molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), and subcellular localization (SL). Subcellular localization was predicted with ProtComp 9.0 (https://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=index&group=programs&subgroup=proloc, accessed on 15 May 2025).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the LbWOX Proteins

We performed intraspecific and interspecific collinearity analyses of the LbWOX genes using TBtools-II [49]. For multiple sequence alignment, we used WOX protein sequences from L. barbarum, potato (S. tuberosum), A. thaliana, Zea mays (maize), Triticum aestivum (wheat), Physcomitrium patens, and tomato (S. lycopersicum). The alignment was performed with MEGA 11 software [50]. We then constructed a phylogenetic tree with the neighbor-joining approach with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 11. The tree was visualized on the Interactive Tree of Life(iTOL v7) (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 15 May 2025).

2.3. Gene Analysis of LbWOX Genes: Conserved Motifs, Chromosomal Distribution, Synteny, Cis-Regulatory Elements

To characterize the structure and genomic organization of the LbWOX gene family, a series of bioinformatic analyses was performed. Protein sequences were aligned and compared using ESPript 3.0 [51]. The exon–intron architecture was determined using TBtools-II. Conserved protein motifs were identified with the MEME suite [52], specifying a maximum of 15 motifs [51], while tertiary structures were predicted through homology modeling on the SWISS-MODEL platform [53]. Genomic coordinates, including chromosomal locations and lengths, were extracted from the official annotation file. For promoter analysis, a 2000 bp region upstream of each transcription start site was defined, and cis-regulatory elements (CREs) within these regions were identified using PlantCARE [54]. Finally, TBtools-II [49] was employed to integrate and visualize these genomic features.

2.4. Transcriptomic Data Download, Normalization, and Heatmap Generation

To investigate LbWOX genes potentially involved in L. barbarum growth and development, we analyzed their transcript abundance in fruit tissue by RNA-Seq (data unpublished). Sequencing was performed by Metware Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) on an Illumina NovaSeq (or MGIseq 2000) platform, generating paired-end 150 bp reads. Following stringent quality control, each of the three biological replicates yielded ≥20 million clean read pairs (≥6 Gb of high-quality data). Publicly available transcriptome data for roots, stems, and leaves were retrieved from the NCBI database [55] (accessed on 15 May 2025). All expression data were normalized using a log2(FPKM+1) transformation [49], and expression patterns were visualized with the R (4.5.1) [56].

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Characterization of the LbWOX Genes

We identified eighteen LbWOX genes based on the existence of a conserved homeobox domain (PF00046). This was confirmed through PROSITE, HMMER, and NCBI-CDD analyses. Bioinformatic analysis showed that these proteins contain 168 to 382 amino acids. Their molecular weights range from 19.96 kDa to 43.50 kDa. The predicted isoelectric point (pI) values vary from 5.16 (acidic) to 10.06 (basic). Subcellular localization predictions suggest that all LbWOX proteins are located in the nucleus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of physicochemical properties and subcellular localization of LbWOXs in L. barbarum.

3.2. Gene Location of LbWOX Genes on L. barbarum Chromosomes

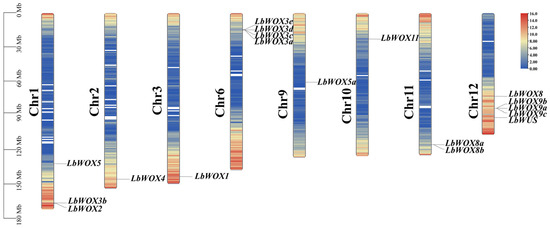

We mapped the genomic positions of the LbWOX genes using the wolfberry genome GFF file and physical location data (Figure 2). The eighteen LbWOX genes are unevenly distributed across chromosomes 1 to 12. Most are located near the ends of the chromosomes. Chromosomes 1, 6, and 12 contain more LbWOX genes. In contrast, chromosomes 2, 3, and 9 each have only one copy. No LbWOX genes were found on the other chromosomes. Notably, LbWOX8a and LbWOX8b form a tandem duplication cluster. This suggests that local duplication events helped expand the LbWOX family in wolfberry during evolution.

Figure 2.

Distribution of LbWOX genes across the L. barbarum genome. The left axis displays chromosome length in megabases (Mb). Gene density is depicted by a red-to-blue color gradient, representing high to low density, respectively. Only eight chromosomes are shown. The remaining four chromosomes (out of 12 total) contain no LbWOX genes.

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of LbWOX Genes

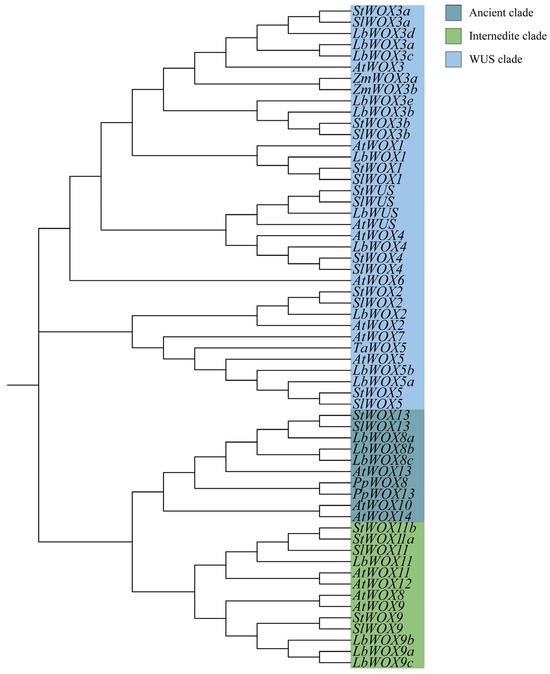

A tree was reconstructed to resolve the evolutionary relationships of the LbWOX sequences. Sequences from L. barbarum, S. tuberosum, S. lycopersicum, and A. thaliana were aligned using MEGA 11.0. The results (Figure 3) show that the LbWOXs are segregated into three clades: WUS clade, intermediate clade, and ancient clade. The WUS clade contains the largest number of members, such as LbWUS, LbWOX1, LbWOX2, LbWOX3a-e, LbWOX4, and LbWOX5. In contrast, the intermediate clade comprises only LbWOX11 and LbWOX9, while the ancient clade contains a single member, LbWOX8. Unlike some other species, L. barbarum has no LbWOX13 gene in the ancient clade. This suggests that LbWOX8 may have taken over its function. This pattern is also seen in barley, where only one LbWOX8 homolog exists in the ancient clade [29]. Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis revealed that PpWOX13 and PpWOX8 cluster with LbWOX8 within the ancient clade, confirming the deep evolutionary conservation of the WOX8 lineage [37]. Notably, LbWOX1 and LbWOX6 exhibit high sequence similarity yet are retained as distinct genes. The maize genome contains multiple WOX3 orthologs, including NARROW SHEATH1 (NS1), NS2, WOX3a/3a+, and WOX3b, which are functionally parallel to the WOX3a-e subfamily in L. barbarum [57,58].

Figure 3.

Phylogeny of WOX sequences from A. thaliana, S. tuberosum (potato), S. lycopersicum (tomato), Zea mays (maize), Triticum aestivum (wheat), Physcomitrium patens and L. barbarum. The tree is divided into ten subcategories.

3.4. Multiple Sequence Comparison Analysis of the LbWOXs

A comparative analysis of LbWOX and AtWOX protein sequences was performed with ESPript 3.0. This analysis showed strong conservation in their homeodomain structures. Both proteins share a Helix-Loop-Helix-Turn-Helix (HLHTH) folding pattern (Figure 4). In the L. barbarum homeodomain, several key residues are highly conserved. Conserved residues include a Q (helix 1); I and L (helix 2); a L (turn); and N, V, W, F, Q, N, and R (helix 3). These results match previous findings in Melastoma dodecandrum Lour [30]. The strong conservation of these positions suggests a critical indispensable role in LbWOX proteins. Additionally, LbWOXs clustered with known WOX genes from A. thaliana. This supports their predicted roles in functional differentiation.

Figure 4.

Functional domain analysis of LbWOX family members. The red blocks indicate highly conserved residues; α1, α2, and α3 correspond to α-helices within the protein structure.

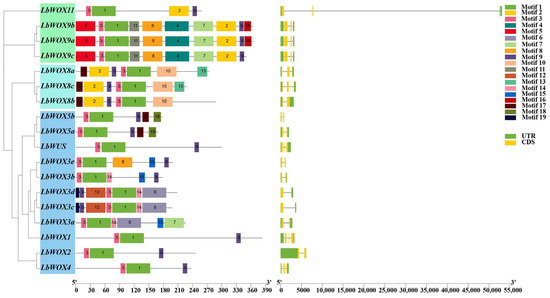

3.5. Identification of Structure, Conserved Motifs and Three-Dimensional Structure Analysis

To characterize the LbWOX gene family, we examined their exon–intron compositions, which revealed considerable structural diversity. The number of exons among the 18 family members varied from two to four. Specifically, ten genes comprise two exons, three contain three exons, and five feature four exons (Figure 5). Notably, the gene structures were highly conserved within each phylogenetic clade, with closely related members sharing nearly identical exon–intron patterns. This structural conservation underscores the evolutionary relationships within the LbWOX family and suggests functional similarities among its members.

Figure 5.

Identification of gene structure and conserved motifs in LbWOX proteins was performed with TBtools-II. In the schematic representation, distinct motifs are annotated as colored boxes, with a scale indicating their lengths in amino acids (aa).

Our MEME analysis revealed 19 conserved domains, spanning from 11 to 50 amino acids in length, within the eighteen LbWOX proteins (Figure 5). All eighteen LbWOX proteins universally harbor motif 1 and motif 3, established components of the homeobox domain. This conservation implies their essential structural and functional roles, a conclusion consistent with prior studies [59]. Notably, motif 10 is exclusive to LbWOX8, representing a distinctive feature of the ancient clade. Within the intermediate clade, motifs 4 and 5 are exclusively contained within LbWOX9a, LbWOX9b, and LbWOX9c, while motif 12 is specific to LbWOX3c and LbWOX3d.

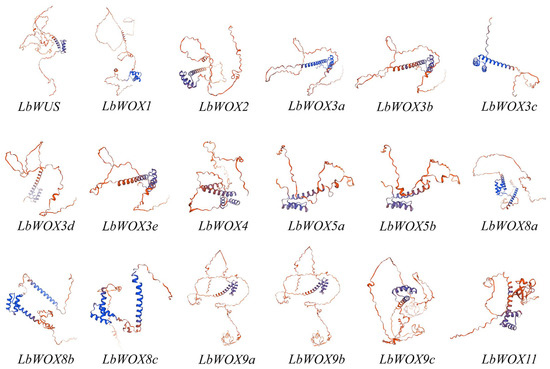

To elucidate the architecture of LbWOX proteins, a structural model was generated using SWISS-MODEL. Although the 18 identified LbWOX proteins display diverse lengths and structural configurations, they consistently contain a conserved homeodomain, representing a defining characteristic of plant WOX protein family members (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prediction of the tertiary structure of LbWOX family proteins.

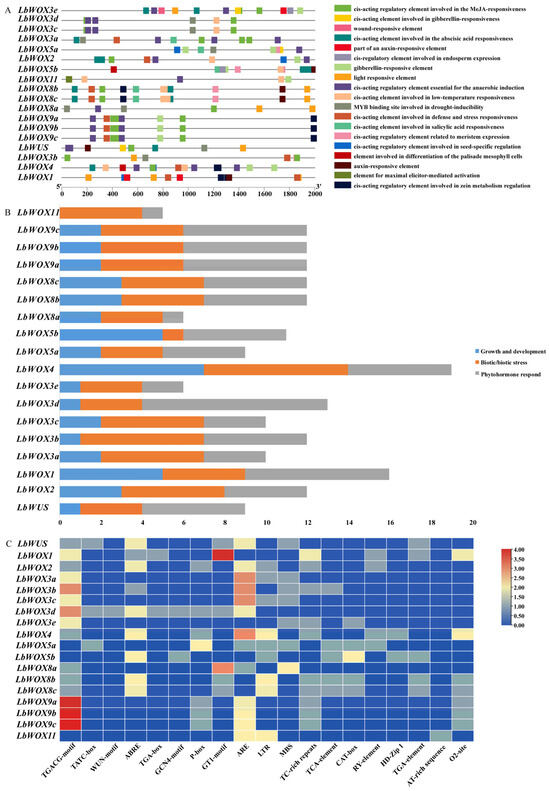

3.6. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements

Analysis of CREs in promoter areas reveals functional diversity among gene families by modulating pathways such as plant development, stress adaptation, light signaling, and metabolism [30,60]. Following filtration of generic elements, we detected 19 specific cis-regulatory motifs assigned to functional categories including cell development and so on (Figure 7A). Notable elements included those associated with mesophyll cell differentiation, along with endosperm expression, auxin-responsive element and meristem expression. The prevalence of phytohormone-related motifs suggests that LbWOX gene expression is likely modulated by hormonal signals. Furthermore, differentiation-related elements were identified in LbWOX4 and LbWOX5b, implicating their roles in tissue differentiation. Strikingly, LbWOX4 contained the highest abundance of growth-related cis-elements among all members, pointing to its potentially central role in this process (Figure 7B,C).

Figure 7.

CREs were predicted in the promoters of LbWOX genes. Analyses were performed via PlantCARE on regions spanning 2 kb upstream of the translation initiation sites. Differentiation-related CREs are depicted as distinctly colored bars within the promoter architecture profiles. (A) Cis-regulatory element; (B) Statistics of Growth and Development, Biotic/Abiotic Stress, and Phytohormone Responses; (C) Statistics of Cis-regulatory element contained in LbWOX family genes.

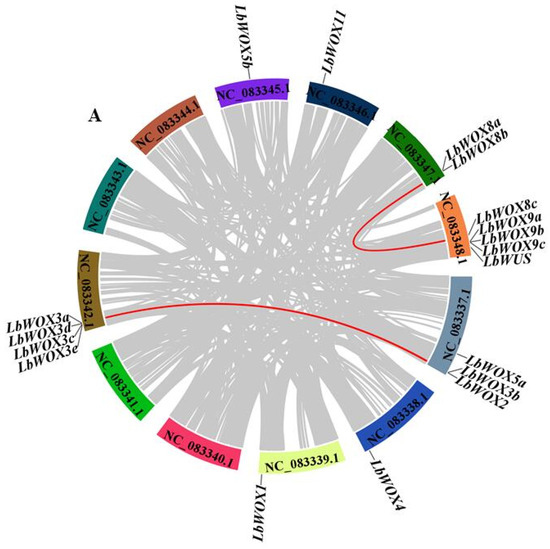

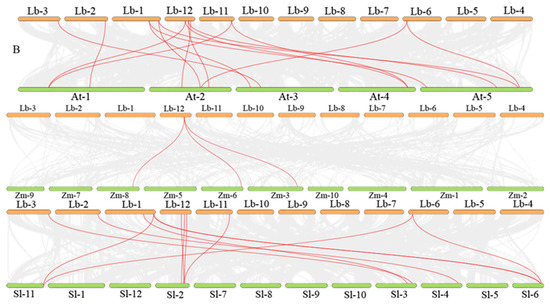

3.7. Synteny Analysis of the LbWOX Genes

We identified two segmental duplication events within syntenic blocks (Figure 8A), which have contributed to the amplification of the LbWOX genes. These duplications provide insight into the family’s evolutionary history and functional diversification of LbWOXs. Intraspecific synteny analysis identified two segmental duplication events in the LbWOXs gene family: LbWOX2–LbWOX3d and LbWOX3b–LbWOX3d, suggesting these duplications contributed to the family’s expansion. Tandem duplication analysis revealed four distinct pairs of recently duplicated genes within the LbWOX family: LbWOX3a/3c, LbWOX8b/8c, LbWOX9a/9b, and LbWOX9b/9c, indicating multiple local amplification events. We compared collinearity relationships between LbWOXs and AtWOXs (Figure 8B), which revealed 15 syntenic gene pairs. Furthermore, we performed comparative synteny analyses of L. barbarum with maize and tomato. The analysis identified three syntenic gene pairs between L. barbarum and maize (Figure 8B). Additionally, eleven orthologous gene pairs were detected in the L. barbarum-tomato comparison (Figure 8B). These results reveal conserved genomic organization between these species. The higher number of syntenic pairs with tomato supports the close phylogenetic relationship expected within Solanaceous species.

Figure 8.

Syntenic relationships of LbWOX genes were analyzed between L. barbarum and A. thaliana. Intra-genomic synteny is shown in (A), with red lines connecting syntenic gene pairs. (B) displays comparative synteny between the two species; Syntenic LbWOX gene pairs (red lines) are shown against a background of genome-wide collinear blocks (gray lines). (Note: NC_083337.1 corresponds to chromosome 1, with subsequent accessions following in numerical order).

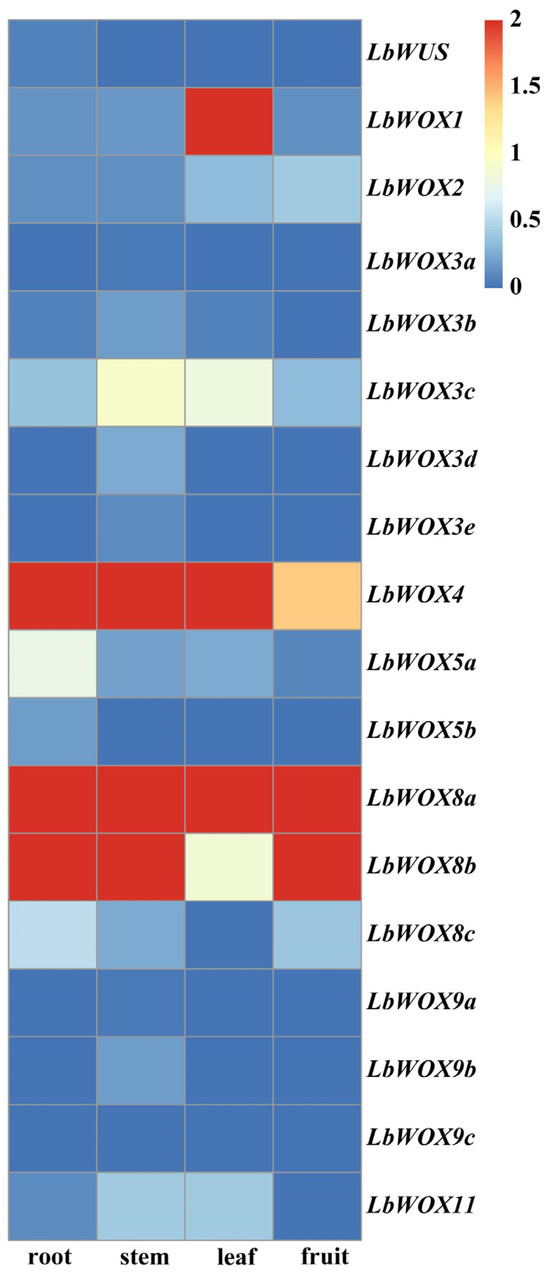

3.8. Expression Patterns of LbWOX Genes

To characterize the expression patterns of the LbWOX gene family (Figure 9), we analyzed transcriptomic data from four tissues of L. barbarum. While LbWUS showed low constitutive expression, consistent with its specialized role in the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and analogous to the function of TaWUS [61] in wheat floral whorl development, LbWOX9 transcripts were also low, aligning with a putative function in embryonic development [62]. In contrast, several members exhibited marked tissue specificity. Notably, LbWOX4 (WUS clade) was highly expressed in roots and stems, with peak levels in stems, suggesting a primary role in stem development; this aligns with its reported function in root vascular procambium differentiation in A. thaliana and S. lycopersicum [63]. Similarly, high LbWOX1 expression in leaves corresponds to the roles of its orthologs AtWOX1 and CSWOX1 in leaf blade growth [64]. Expression of LbWOX2 in leaves and fruit parallels the role of PpWOX2 [65] in regulating embryogenesis-related traits, and elevated LbWOX3c expression in stems and leaves is congruent with findings for ZmWOX3 [66]. The expression pattern of LbWOX11 (in stems and leaves) is similar to that of DcWOX11 in Dendrobium catenatum. In that species, overexpression of DcWOX11 alters leaf morphology in Arabidopsis, hinting at a conserved role in leaf development [67]. Furthermore, phylogenetic clustering of tomato SlWOX13 [68] with LbWOX8 and their shared high fruit expression suggests functional conservation. The known capacity of PpWOX13-like genes to reprogram leaf cells into stem cells in Physcomitrella patens [37] implies that the ancient WOX13/8 clade may possess broad developmental plasticity, a hypothesis further supported by the wide tissue expression of LbWOX8. The multifunctional potential of this clade warrants further investigation (Table 2).

Figure 9.

Expression heatmap of LbWOX genes across different organs of L. barbarum. This figure depicts the expression patterns of 18 LbWOX genes in various plant tissues. Expression values are log2-transformed; the red rectangle indicates high expression, and blue rectangle represents low expression.

Table 2.

Summary of WOX genes in this study.

4. Discussion

The WOX gene family functions as central regulators of tissue differentiation, coordinating key developmental programs in plants. It helps regulate stem cell development, leaf growth, and root formation. We identified eighteen LbWOX genes in L. barbarum in this research. The eight chromosomes harbor these genes in an uneven distribution. The count of LbWOX genes is similar to that in potato (11) [80,81] and tomato (10) [82]. It is slightly higher than in grape (12) [83] and tobacco (9) [84]. By comparison, Brassica napus has many more WOX genes—a total of 58 [85]. These differences may be due to variations in genome size or gene duplication events. Phylogenetic analyses showed that L. barbarum WOX genes fall into three clades. Their branching pattern is similar to that in other Solanaceae species like potato and tomato. The clade distribution is also consistent with these related species. Every LbWOX protein contains a conserved homeodomain, matching earlier reports [86]. NS1 and NS2 are orthologs of WOX3 in maize (Zea mays), encoding WOX3 transcription factors that function in the mediolateral development of leaves and embryonic organs. WOX3a is a paralogous WOX3 gene, which also acts in mediolateral organ patterning, with expression and function notably observed in the leaf, coleoptile, and scutellum [57,58]. Therefore, we suggest that LbWOX genes likely help control differentiation and plant growth in L. barbarum, similar to their functions in other species.

Motif analyses showed that all 18 LbWOX genes contain motifs 1 and 3. This suggests that these genes may have similar functions. Different clades also have unique motifs. Notably, motif 4 is exclusively present in the intermediate clade. In Melastoma dodecandrum Lour, the ancient clade contains motifs 3, 6, and 10, which are absent in other evolutionary branches; the intermediate clade likewise features a unique motif [87]. These clade-specific motif patterns suggest functional divergence among WOX genes across lineages. For instance, AtWOX5, which belongs to the WUS clade, exhibits predominant expression in roots and inflorescences. It governs development in these organs. Similarly, PtoWOX5a from poplar shows high expression in roots [9]. NtabWUS can maintain shoot apical stem cell activity [81]. LlWOX11 positively regulates bulbil formation in Lilium lancifolium [88].

Cis-regulatory element analysis helps us understand gene function, agronomic traits, and plant metabolism [89]. Studies show that WOX regulators are key players in developmental processes [90] and stress adaptation [82]. Through bioinformatic examination of promoter regions of LbWOX genes, we identified numerous cis-elements associated with cellular differentiation, meristem expression and so on. These findings imply putative roles for LbWOX genes in mediating cell differentiation, light perception, stress responses, and developmental regulation in L. barbarum.

Gene duplication plays a dual role in plant evolution. It supports functional diversification and may lead to new protein oligomeric states [91]. Segmental and tandem duplications constitute primary modes for gene family amplification [92]. Synteny analysis was conducted with TBtools to investigate the amplification of the LbWOX genes. This collinearity analysis found multiple homologous gene pairs between LbWOX and SlWOX genes. These results suggest they share a common ancestor.

Gene expression patterns help us understand gene function. We employed RNA-Seq to profile the expression in four tissues: roots, stems, leaves, and fruits. Most WOX genes showed little or no expression. However, LbWOX4 was expressed in roots and stems. We found cis-elements for mesophyll cell differentiation in the promoters of LbWOX4 and LbWOX5b. LbWOX4 has the largest number of cis-elements compared to other members, suggesting that LbWOX4 may perform diverse regulatory functions in root and stem differentiation. Furthermore, the high expression of LbWOX4 in roots and stems, coupled with its association with vascular development, implicates it as a prime candidate for enhancing adventitious root formation during cutting propagation. This finding is consistent with the role of PiWOX4 in promoting cambium and procambium differentiation. It further suggests that this conserved function can enhance both rooting efficiency and overall survival rates of cuttings [93]. These results agree with transcriptomic studies in other species. For example, PaWOX4, PaCLE41a, PaCLE41b, and PaTDR are highly expressed in shoots and woody tissues in spruce. PagWOX4 helps regulate cambial activity [94]. PttWOX4 could modulates cell division and promotes stem growth [74]. Similarly, AtWOX4 is involved in TDIF signaling pathway associated with stem cell [95]. Together, these evidence establish a conserved function for WOX genes in plant cell differentiation and organogenesis.

Our results clarify the functional diversification among LbWOX regulators in L. barbarum. This improves our understanding of their roles and potential applications. However, our study has certain limitations. The identification of LbWOX genes and the prediction of their functions were primarily based on bioinformatic approaches. Further experimental studies may be required to validate the predictions and elucidate the regulatory mechanism of LbWOX genes on plant regeneration.

5. Conclusions

We report on the genome-wide characterization of the LbWOX genes. We identified 18 LbWOX genes in total, which are located in the wolfberry’s 8 chromosomes. Cis-regulatory element analysis linked these genes to cell differentiation, hormone responses, stress adaptation, and development. Synteny analysis indicated that segmental duplication helped expand this gene family. Expression profiling revealed distinct tissue-specific patterns: LbWOX1 and LbWOX4 were highly expressed in leaves, suggesting a role in leaf growth and a potential to enhance differentiation capacity. Concurrently, the high expression of LbWOX4 and LbWOX8 in roots and stems, associated with vascular development, implicates them as key candidates for improving adventitious root formation in cutting propagation. Notably, LbWOX8b/c was also highly expressed in fruit, pointing to a potential role in regulating ripening timing, which could inform breeding strategies for synchronized harvest. Collectively, these findings establish a foundational genetic framework for targeting LbWOX genes in molecular breeding strategies to reduce genotype-dependent constraints and improve regeneration efficiency in goji berry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F., Z.Z., S.Y., G.D., H.W., and J.L.; methodology, G.D., J.L., and Z.Z.; investigation, S.Y., Z.Z., G.D., and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F., Z.Z., G.D., S.Y., H.W. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z., H.W., S.Y., and G.F.; supervision, G.F.; funding acquisition, G.F., G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This Research was Funded by A Major Science and Technology Project under the Qinghai Province Science and Technology Plan (2023-NK-A4).

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptome data used in this study is available from the NCBI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie, W.; Chen, H.G.; Chen, R.H.; Zhao, C.; Gong, X.J.; Zhou, X. Intervention effect of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide on lead-induced kidney injury mice and its mechanism: A study based on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117197. [Google Scholar]

- Neelam, K.; Dey, S.; Sim, R.; Lee, J.; Au Eong, K.-G. Fructus lycii: A Natural Dietary Supplement for Amelioration of Retinal Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Fan, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Isolation, structural characterization, and antioxidativity of polysaccharide LBLP5-A from Lycium barbarum leaves. Process. Biochem. 2016, 51, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Duan, G.; Qi, Y.; Almezgagi, M.; Fan, G.; Ma, Y. Exploration of chemical compositions in different germplasm wolfberry using UPLC-MS/MS and evaluation of the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1426944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, T.; Mayer, K.F.; Berger, J.; Jürgens, G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 1996, 122, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; Jia, L.; Wang, M.; Huang, A.; You, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. WUS-RELATED HOMEOBOX 14 boosts de novo plant shoot regeneration. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, F.; Chang, Z.; Kong, X.; Xia, L.; Zhou, W.; Laux, T.; Zhang, L. Functional conservation and divergence of the WOX gene family in regulating meristem activity: From Arabidopsis to crops. Plant Physiol. 2025, 199, kiaf374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Jia, H.; Liu, B.; Sun, P.; Hu, J.; Wang, L.; Lu, M. The WUSCHEL-related homeobox 5a (PtoWOX5a) is involved in adventitious root development in poplar. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Lu, M. WUSCHEL-related Homeobox genes in Populus tomentosa: Diversified expression patterns and a functional similarity in adventitious root formation. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Shiting, L.; Chen, Z.; Yuyan, H.; Minrong, Z.; Shuyan, L.; Libao, C. NnWOX1-1, NnWOX4-3, and NnWOX5-1 of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn) promote root formation and enhance stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xie, W.; Huang, M. Two WUSCHEL-related HOMEOBOX genes, PeWOX11a and PeWOX11b, are involved in adventitious root formation of poplar. Physiol. Plant. 2015, 155, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, L. Transcription Factors WOX11/12 Directly Activate WOX5/7 to Promote Root Primordia Initiation and Organogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Lin, Z.; He, H.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, K.; Du, K.; Zhang, R. Comprehensive analysis and identification of the WOX gene family in Schima superba and the key gene SsuWOX1 for enhancing callus regeneration capacity. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shi, L.; Liang, X.; Zhao, P.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Chang, Y.; Hiei, Y.; Yanagihara, C.; Du, L.; et al. The gene TaWOX5 overcomes genotype dependency in wheat genetic transformation. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Shan, Z.; Zhou, X.-a. Genome-Wide Analysis of the WOX Gene Family and Function Exploration of GmWOX18 in Soybean. Plants 2019, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Ryan, L.; Sardesai, N.; Wu, E.; Lenderts, B.; Lowe, K.; Che, P.; Anand, A.; Worden, A.; van Dyk, D.; et al. Leaf transformation for efficient random integration and targeted genome modification in maize and sorghum. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, X.; Hao, Z.; Long, X.; Shi, J.; Chen, J. Overexpression of Liriodenron WOX5 in Arabidopsis Leads to Ectopic Flower Formation and Altered Root Morphology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, T.; Abel, C.; Wahl, V. Flowering time and the identification of floral marker genes in Solanum tuberosum ssp. andigena. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, O.-S.; Jung, Y.J.; Seo, P.J. Ectopic expression of WOX5 promotes cytokinin signaling and de novo shoot regeneration. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 2415–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipova, M.A.; Mortier, V.; Demchenko, K.N.; Tsyganov, V.E.; Tikhonovich, I.A.; Lutova, L.A.; Dolgikh, E.A.; Goormachtig, S. WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX5Gene Expression and Interaction of CLE Peptides with Components of the Systemic Control Add Two Pieces to the Puzzle of Autoregulation of Nodulation. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Ma, D.; Niu, C.; Ma, X.; Li, K.; Tahir, M.M.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D. Transcriptome analysis reveals the regulatory mechanism by which MdWOX11 suppresses adventitious shoot formation in apple. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, J.; Jie, E.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Jiang, L.; Ahn, W.S.; Kim, C.A.-O.X.; Kim, S.W. Temporal and Spatial Expression Analysis of Shoot-Regeneration Regulatory Genes during the Adventitious Shoot Formation in Hypocotyl and Cotyledon Explants of Tomato (CV. Micro-Tom). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, R.; Weng, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Xiao, H. Domain-specific expression of meristematic genes is defined by the LITTLE ZIPPER protein DTM in tomato. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, M.; Iwase, A.; Rymen, B.; Lambolez, A.; Kojima, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Heyman, J.; Watanabe, S.; Seo, M.; De Veylder, L.; et al. Wounding Triggers Callus Formation via Dynamic Hormonal and Transcriptional Changes. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Xu, W.; Chang, J.; Li, A.; Mao, X.; Zhang, X.; Jing, R. Novel function of a putative MOC1 ortholog associated with spikelet number per spike in common wheat. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Wei, X.; Liu, L.; Li, F.; Ge, X. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed GhWOX4 Intercedes Myriad Regulatory Pathways to Modulate Drought Tolerance and Vascular Growth in Cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Wen, S.S.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Gao, B.; Lu, M.Z. PagWOX11/12a activates PagCYP736A12 gene that facilitates salt tolerance in poplar. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Song, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Lei, X.; Pei, D. Characterization of walnut JrWOX11 and its overexpression provide insights into adventitious root formation and development and abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 951737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Zhou, L.; Zong, Y.; Gao, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. Genome-Wide Identification of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Barley Reveals the Potential Role of HvWOX8 in Salt Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Geng, W.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H. Genome-wide prediction and functional analysis of WOX genes in blueberry. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Feng, H.; Hu, Q.; Qu, H.; Chen, A.; Yu, L.; Xu, G. Improving rice tolerance to potassium deficiency by enhancing OsHAK16p: WOX11-controlled root development. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, J.; Joshi, S.; Gupta, S.; Kesarwani, V.; Shankar, R.; Joshi, R. Genome-wide identification of WUSHEL-related homeobox genes reveals their differential regulation during cold stress and in vitro organogenesis in Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle ex Benth. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.—Plant 2024, 60, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.U.; Azam, S.M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, C.; Ali, H.; Zhao, L.; Chen, P.; Yi, L.; Priyadarshani, S.V.G.N.; Yuan, Q. Expression Profiles of Wuschel-Related Homeobox Gene Family in Pineapple (Ananas comosus L). Trop. Plant Biol. 2017, 10, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, H.; Ran, L.; Zang, Y.; Xiong, F. Cytological and molecular characteristics of delayed spike development in wheat under low temperature in early spring. Crop. J. 2022, 10, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Song, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, D.X. The Interaction between Rice ERF3 and WOX11 Promotes Crown Root Development by Regulating Gene Expression Involved in Cytokinin Signaling. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Dai, M.; Huang, L.; Zhou, D.X. The WUSCHEL-related homeobox gene WOX11 is required to activate shoot-borne crown root development in rice. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, M.; Iwase, A.; Ito, T.; Tanaka, H.; Favero, D.S.; Kawamura, A.; Sakamoto, S.; Wakazaki, M.; Tameshige, T.; Fujii, H.; et al. Wound-inducible WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX 13 is required for callus growth and organ reconnection. Plant Physiol. 2021, 188, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, M.S.; Pasternak, T.; Omelyanchuk, N.A.; Novikova, D.D.; Palme, K.; Mironova, V.V.; Lavrekha, V.V. Cell Dynamics in WOX5-Overexpressing Root Tips: The Impact of Local Auxin Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 560169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, N.; Xu, L. Pluripotency acquisition in the middle cell layer of callus is required for organ regeneration. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Shankle, K.; Cho, M.J.; Tjahjadi, M.; Khanday, I.; Sundaresan, V. Synergistic induction of fertilization-independent embryogenesis in rice egg cells by paternal-genome-expressed transcription factors. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 1892–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Tan, Y.S.; Singh, P.; Khalid, N.; Harikrishna, J.A. Expression and DNA methylation of SERK, BBM, LEC2 and WUS genes in in vitro cultures of Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants Int. J. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 24, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Z.J.; Su, Y.H.; Han, H.N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.S. DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis by modulating WUSCHEL expression and auxin signaling. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Xiong, T.; Liang, K.; Liao, C.; Huang, B.; Lu, Y.; et al. Identification and Functional Analysis of WOX Genes in Macadamia spp. Reveal WOX1 and WOX4 Homologs Involved in Shoot Regeneration. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wolabu, T.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tadesse, D.; Chen, N.; Xu, A.; Bi, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. WOX family transcriptional regulators modulate cytokinin homeostasis during leaf blade development in Medicago truncatula and Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3737–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Du, K.; Kang, X.; Wei, H. The diverse roles of cytokinins in regulating leaf development. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.L.; Li, Y.L.; Fan, Y.F.; Li, Z.; Yoshida, K.; Wang, J.Y.; Ma, X.K.; Wang, N.; Mitsuda, N.; Kotake, T.; et al. Wolfberry genomes and the evolution of Lycium (Solanaceae). Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A ”one for all, all for one“ bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, R.; Wang, H.; Hui, T.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; An, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Morphological, physiological, and transcriptomic insights into response the of Lycium barbarum L. (‘Ningqi No.1’) seedlings to low-nitrogen stress. Genomics 2025, 117, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. iMeta 2022, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, R.; Scanlon, M.J. Genetic analyses of embryo homology and ontogeny in the model grass Zea mays subsp. mays. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satterlee, J.W.; Evans, L.J.; Conlon, B.R.; Conklin, P.; Martinez-Gomez, J.; Yen, J.R.; Wu, H.; Sylvester, A.W.; Specht, C.D.; Cheng, J.; et al. A Wox3-patterning module organizes planar growth in grass leaves and ligules. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Xu, A.; Xu, P.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Yang, X.; Ming, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Xue, L.; et al. Transcriptional dynamics and functions of WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) genes from Ginkgo biloba in tissue culture. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, L. Recruitment of IC-WOX Genes in Root Evolution. Trends Plant Sci 2018, 23, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Xia, Y.; Li, Z.; Jing, D.; Du, J.; Niu, N.; Ma, S.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Identification of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family, and Interaction and Functional Analysis of TaWOX9 and TaWUS in Wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendelman, A.; Zebell, S.; Rodriguez-Leal, D.; Dukler, N.; Robitaille, G.; Wu, X.; Kostyun, J.; Tal, L.; Wang, P.; Bartlett, M.E.; et al. Conserved pleiotropy of an ancient plant homeobox gene uncovered by cis-regulatory dissection. Cell 2021, 184, 1724–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Strable, J.; Shimizu, R.; Koenig, D.; Sinha, N.; Scanlon, M.J. WOX4 promotes procambial development. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, H.; Li, C.; Shen, G.; Liu, X.; Weng, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, Z. WUSCHEL-related homeobox1 (WOX1) regulates vein patterning and leaf size in Cucumis sativus. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, S.B.; Trontin, J.F.; Raschke, J.; Zoglauer, K.; Rupps, A. Constitutive Overexpression of a Conifer WOX2 Homolog Affects Somatic Embryo Development in Pinus pinaster and Promotes Somatic Embryogenesis and Organogenesis in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 838421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Zhang, X.; Gregory, J.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Minow, M.A.A.; Galli, M.; Gallavotti, A.; Schmitz, R.J. WUSCHEL-dependent chromatin regulation in maize inflorescence development at single-cell resolution. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.T.; Fu, K.; Han, Z.G.; Li, C.; Si, J.P.; Chen, D.H. Functional analysis of WOX family genes in Dendrobium catenatum during growth and development. Yi Chuan = Hered. 2023, 45, 700–714. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhou, Y.; Lai, H.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X. WUSCHEL-related homeobox transcription factor SlWOX13 regulates tomato fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 2322–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musialak-Lange, M.; Fiddeke, K.; Franke, A.; Kragler, F.; Abel, C.; Wahl, V. The trehalose 6-phosphate pathway coordinates dynamic changes at the shoot apical meristem in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2025, 199, kiaf300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Tsugeki, R.; Rikirsch, E.; Laux, T.; Okada, K. Roles of the middle domain-specific WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX genes in early development of leaves in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, Y.; Gong, W.; Laux, T.; Li, S.; Xiong, F. A tripartite transcriptional module regulates protoderm specification during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 2038–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Nakata, M.; Okada, K. The three-domain model: A new model for the early development of leaves in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa Chhetri, G.; Du, Q.; Zhao, S.; Cui, X.; Qi, L.; Wang, H. RABBIT EARS directly regulates WOX4 transcription and inhibits secondary growth in Arabidopsis stem. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 3010–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukoglu, M.; Nilsson, J.; Zheng, B.; Chaabouni, S.; Nilsson, O. WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX4 (WOX4)-like genes regulate cambial cell division activity and secondary growth in Populus trees. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Lam, E. Plant metacaspases orchestrate wound-induced pathways for immunity and tissue regeneration. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2025, 124, e70531. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Xiong, F.; Wangler, A.M.; Bischoff, T.; Wang, K.; Miao, Y.; Slane, D.; Schwab, R.; Laux, T.; Bayer, M. Phosphorylation-dependent activation of the bHLH transcription factor ICE1/SCRM promotes polarization of the Arabidopsis zygote. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Bian, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Cao, L.; et al. A rice single cell transcriptomic atlas defines the developmental trajectories of rice floret and inflorescence meristems. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. WOX11 and 12 are involved in the first-step cell fate transition during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Tan, F.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Yuan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.X. WOX11 recruits a histone H3K27me3 demethylase to promote gene expression during shoot development in rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2356–2369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-S.; Park, K.H.; Park, S.-J.; Ko, S.-R.; Moon, K.-B.; Koo, H.; Cho, H.S.; Park, S.U.; Jeon, J.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; et al. WUSCHEL controls genotype-dependent shoot regeneration capacity in potato. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hamyat, M.; Liu, C.; Ahmad, S.; Gao, X.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y. Identification and Characterization of the WOX Family Genes in Five Solanaceae Species Reveal Their Conserved Roles in Peptide Signaling. Genes 2018, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Sun, M.; Chen, S.; Ma, H.; Lin, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, M. Molecular characterization and gene expression analysis of tomato WOX transcription factor family under abiotic stress and phytohormone treatment. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, G.; Minuto, M.; Boccacci, P.; Perrone, I.; Vallania, R.; Gribaudo, I. Characterization of expression dynamics of WOX homeodomain transcription factors during somatic embryogenesis in Vitis vinifera. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, P.; Sun, M.X. Comparative Analysis of WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Genes Revealed Their Parent-of-Origin and Cell Type-Specific Expression Pattern During Early Embryogenesis in Tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Liu, M.M.; Ran, F.; Guo, P.C.; Ke, Y.Z.; Wu, Y.W.; Wen, J.; Li, P.F.; Li, J.N.; Du, H. Global Analysis of WOX Transcription Factor Gene Family in Brassica napus Reveals Their Stress- and Hormone-Responsive Patterns. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zong, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, D. Genome-wide analysis of WOX gene family in rice, sorghum, maize, Arabidopsis and poplar. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Xie, K.; Ahmad, S.; Zhao, K.; Peng, D.; Liu, Z.J.; Zhou, Y. The Genome-Level Survey of the WOX Gene Family in Melastoma dodecandrum Lour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, P.; Bi, M.; Xu, L.; Ming, J. Identification of cis-acting elements recognized by transcription factor LlWOX11 in Lilium lancifolium. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70224. [Google Scholar]

- Yocca, A.E.; Edger, P.P. Current status and future perspectives on the evolution of cis-regulatory elements in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 65, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, N.; Zhao, Y. The rice WUSCHEL-related homeobox genes are involved in reproductive organ development, hormone signaling and abiotic stress response. Gene 2014, 549, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, S.; Tawfik, D.S.; Levy, E.D. How gene duplication diversifies the landscape of protein oligomeric state and function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2022, 76, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zong, F.; Xue, X.; Gao, J.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; He, B.; Lin, W.; Wu, B.; et al. Impact of naphthalene acetic acid and Piriformospora indica on WOX gene expression and rooting in woody ornamentals. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, C.; Chai, G.; Wang, D.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; He, G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, Y.; et al. Ubiquitinated DA1 negatively regulates vascular cambium activity through modulating the stability of WOX4 in Populus. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3364–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Fukuda, H. TDIF peptide signaling regulates vascular stem cell proliferation via the WOX4 homeobox gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).