Abstract

Understory vegetation (shrubs and herbs) mediates belowground biogeochemical processes in forests through litter inputs, root exudation, and microenvironmental regulation; however, the magnitude of these regulatory effects remains poorly quantified. Here, we conducted a 10-year small-scale understory vegetation manipulation experiment in a coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest in central China, aiming to systematically assess the impacts of understory vegetation on soil carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) dynamics. Two experimental treatments were established: (1) the “None” treatment (removal of both understory vegetation and litter) and (2) the “Understory” treatment (litter removal while retaining understory vegetation). Results indicated that compared with the “None” treatment, the “Understory” treatment did not significantly alter the concentrations or stocks of soil organic C (SOC) and total N (p > 0.05), suggesting a weak responsiveness of SOC and total N to understory vegetation presence. In contrast, understory vegetation exerted a significant positive effect on soil P fractions: total P concentration and stock increased by 3.97% and 2.68%, organic P by 6.65% and 5.32%, and available P by 46.38% and 43.96%, respectively (p < 0.05). These results demonstrate that understory vegetation exerts a more pronounced regulatory effect on soil P dynamics than on C and N dynamics. In conclusion, understory vegetation plays a pivotal role in promoting soil P sequestration and improving P availability in coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest ecosystems. We recommend retaining understory vegetation in forest management practices to sustain soil P availability and mitigate widespread P limitation in such ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Forest ecosystems serve as the primary reservoirs of global carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P), and the stability of their biogeochemical cycling processes directly modulates the responses and feedbacks to global climate change [1,2]. Understory vegetation (including shrubs and herbs), characterized by high biomass accumulation potential and rapid turnover rates, constitutes an integral component of forest ecosystems [1,2]. Through litterfall input, root exudate release, and microenvironmental modulation, understory vegetation not only directly regulates the input fluxes and chemical forms of soil C, N, and P but also indirectly drives microbial-mediated nutrient transformation and sequestration processes, thereby playing an irreplaceable role in maintaining forest soil functions and ecosystem stability [1,2,3,4,5].

Despite extensive research on the effects of understory vegetation on soil C, N, and P cycling, notable controversies persist in the current understanding [3,4,5,6]. Understory vegetation removal is generally hypothesized to reduce soil organic C (SOC) stocks by decreasing aboveground C inputs [1,2,3,4,5]. Conversely, other studies have demonstrated that this practice can enhance microbial activity by increasing soil temperature, thereby promoting soil C accumulation [6]. These discrepancies are primarily attributed to variations in ecosystem types, climatic conditions, and plant functional traits. In the context of N cycling, N acts as a limiting nutrient for plant and microbial growth. Understory vegetation can influence key microbial processes such as nitrification and denitrification by regulating belowground C allocation [7,8,9]. However, due to the synergistic effects of soil temperature, moisture, and substrate availability, no consensus has been reached concerning the impacts of understory vegetation on labile N fractions (e.g., NH4+-N and NO3−-N) [7,8,9]. In contrast, research on P cycling remains relatively limited. As the most limiting nutrient element in terrestrial ecosystems, P tends to undergo adsorption and immobilization by clay minerals, iron oxides, and aluminum oxides, forming iron-bound P (Fe-P) and aluminum-bound P (Al-P) with extremely low bioavailability [10,11]. Nevertheless, the regulatory role of understory vegetation in the transformation of soil P fractions (including organic, inorganic, and available fractions) via litter decomposition and root exudate release has yet to be systematically and quantitatively elucidated to date [8,9,12,13].

Understory vegetation removal is a common silvicultural practice worldwide, aimed at alleviating plant competition, promoting seedling regeneration, and preventing forest fires [1,2,3,4], a practice particularly prevalent in subtropical and warm temperate forest regions of China [5,6,7,8,9]. This practice disrupts the material exchange balance between understory vegetation and soil, triggering cascading effects on soil microenvironments (temperature, moisture, pH) and biogeochemical processes [14,15,16,17,18]. However, since most of the existing studies have focused on short-term (<5 years) observations within individual climate zones (tropical or temperate), this short time frame may not be long enough to induce a threshold response in some processes. Consequently, there is still significant uncertainty regarding their long-term impacts on soil C, N, and P stocks [19,20,21,22]. More importantly, forests in climate transition zones (e.g., subtropical–temperate transition zones) are characterized by species convergence between northern and southern regions, with high environmental heterogeneity, more complex biogeochemical cycling processes, and greater sensitivity to global climate change [1,23], making them core areas for global change research. Nevertheless, systematic verification through long-term in situ experiments on the regulatory effects of understory vegetation manipulation on soil C-N-P cycling in this region remains lacking, impeding our understanding and prediction of nutrient cycling processes in sensitive ecosystems.

This study was conducted in mixed coniferous–broadleaved forests in the subtropical–temperate transition zone of central China, utilizing a long-term understory vegetation manipulation experimental facility established in 2015. We systematically investigated the effects of understory vegetation removal on the contents and stocks of SOC, total N, total P, and their key fractions, while simultaneously analyzing the dynamic changes in key regulatory factors such as microbial biomass and fine root biomass. Based on ecosystem biogeochemical cycling theory, two scientific hypotheses were proposed: (1) Long-term understory removal will reduce litter return and root exudates, decreasing exogenous C/N/P inputs and thereby lowering SOC, total N, and total P concentrations and stocks; (2) Understory removal will reduce root exudates (e.g., organic acids, phosphatases), suppressing microbial biomass and activity, which will weaken insoluble P solubilization and significantly lower soil nutrient bioavailability.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The study was conducted in a coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest within the Dabieshan National Field Observation and Research Station of Forest Ecosystem (31°52′ N, 114°04′ E; 205 m above sea level), located in Xinyang City, Henan Province, China. Climatologically, the long-term (1951–2011) mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) in this region are 15.2 °C and 1120 mm, respectively. Approximately 90% of the annual precipitation is concentrated during the growing season, which spans from April to October [24,25]. The soil at this site is characterized as yellow-brown sandy-loam and classified as Cambisols according to the FAO soil classification system [10]. At the initiation of the experiment in 2015, soil physicochemical properties in non-treatment plots were: SOC concentration 28.62 g kg−1, total N concentration 2.57 g kg−1, total P concentration 0.40 g kg−1, bulk density 0.99 g cm−3, and pH 4.5 [1,8,9,23]. The canopy layer is dominated by three main tree species: Quercus variabilis Blume, Quercus acutissima Carruth., and Liquidambar formosana Hance. The understory vegetation consists of shrubs and herbaceous plants, with the dominant species including Lindera glauca (Sieb. et Zucc.) Bl., Vitex negundo L., Rubus corchorifolius L. f., Lygodium japonicum (Thunb.) Sw., and Carex rigescens (Franch.) V. Krecz [6,23,26].

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was implemented on a south-facing slope (slope gradient: ~20°) within the aforementioned coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest. In August 2015, four independent main plots were established, each 20 m × 20 m in size. To account for spatial heterogeneity, two paired experimental treatments were randomly assigned within each main plot. The two treatments were defined as follows: (1) “None” treatment (shrub layer + litter removal): complete removal of all understory shrub vegetation and surface litter; (2) “Understory” treatment (litter-only removal): only surface litter was removed, while the understory shrub layer was retained. This setup resulted in a total of 8 experimental subplots, with each main plot serving as one biological replicate (4 main plots × 2 treatments). Adjacent experimental subplots were separated by a 5 m-wide buffer zone to prevent cross-treatment interference (e.g., litter drift, root expansion). All subplots were standardized in terms of slope gradient, elevation, and aspect, ensuring uniform initial environmental conditions across treatments to eliminate confounding effects from topographic variations.

Specific operational protocols for the treatments were as follows: Understory vegetation was removed by cutting plants at the soil surface, with root systems retained intact to minimize soil profile disturbance; litter removal involved the thorough clearing of both undecomposed and partially decomposed litter layers. To sustain the treatment effects, monthly maintenance was performed, which included clearing newly accumulated litter and regrown understory vegetation in the respective treatment plots.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Fine Root Biomass Determination

Soil sampling was conducted in August 2024 across 8 experimental plots (4 replicates per treatment: understory-retained/removed). Prior to sampling, surface litter was carefully removed to avoid contamination. For each plot, five 0–10 cm topsoil cores (5 cm inner diameter, stainless steel auger) were randomly collected to minimize within-plot variability, then combined and homogenized into one composite sample. All 8 composite samples were immediately sealed in sterile bags, labeled with plot ID, treatment, sampling date, and depth, and transported to the laboratory at 4 °C within 24 h to preserve soil physicochemical properties and microbial activity.

Upon arrival at the laboratory, visible organic debris (e.g., fine roots [0–2 mm diameter], litter fragments) was manually removed. Fine roots were carefully separated, cleaned, and reserved for subsequent analyses: oven-dried at 105 °C for 30 min to deactivate enzymes, followed by drying at 65 °C to constant weight, and weighed to calculate fine root biomass. The remaining soil was sieved through a 2 mm mesh to exclude coarse particles, then divided into three subsamples for targeted analyses: (1) stored at 4 °C for determining physicochemical parameters (e.g., pH, soil moisture, available N, available P); (2) stored at −20 °C for soil microbial analyses; and (3) air-dried for assaying other soil properties.

2.4. Soil Analyses

Soil moisture was determined by oven-drying fresh soil aliquots at 105 °C to a constant weight [10]. Soil pH was measured using a digital pH meter with a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v). Soil bulk density (BD) was determined using stainless steel cutting rings (volume: 100 cm3, inner diameter: 50 mm) collected from three soil profiles per plot; the soil samples in the rings were oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight for BD calculation [11].

Soil organic C (SOC) and total N were analyzed using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany). Prior to the analysis of SOC, air-dried soil samples were treated with 1 mol L−1 HCl for 48 h at 30 °C to remove inorganic carbonates. NH4+-N and NO3−-N were extracted with 2 mol·L−1 KCl solution, and their concentrations were determined via a continuous-flow analytical system (San++, Skalar Analytical B.V., Breda, The Netherlands). Available N was calculated as the sum of NH4+-N and NO3−-N.

Soil microbial biomass C (MBC), N (MBN), and P (MBP) were determined using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method, with conversion factors of 0.45, 0.54, and 0.40 for MBC, MBN, and MBP, respectively [27,28]. Soil available P was extracted from moist soil samples by the Bray-1 method (0.03 mol·L−1 NH4F + 0.025 mol·L−1 HCl) at a soil-to-solution ratio of 1:5 (w/v) [29].

Total soil P was determined colorimetrically following digestion of air-dried soil (<0.15 mm) with a mixture of HClO4 and H2SO4 [29]. Soil inorganic P was extracted by shaking 1 g of air-dried soil (<2 mm) with 50 mL of 0.5 mol·L−1 H2SO4 for 16 h; phosphate ions in the filtrate were measured colorimetrically [11,29]. Soil organic P was calculated as the difference between total P and inorganic P.

2.5. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

Soil C, N, and P stocks were computed as S = A × B × X, where S denotes the stock of C, N, or P (kg m–2 or g m–2); A represents the soil sampling depth (cm); B is the soil bulk density (g cm−3); and X indicates the corresponding C, N, or P content (g kg−1 or mg kg−1).

All data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Prior to formal statistical analyses, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution, and Levene’s test was employed to verify the homogeneity of variance. When these assumptions were violated, data were subjected to natural logarithm (ln) transformation to achieve normality and homoscedasticity. Given the paired treatment design within each block (i.e., “None” vs. “Understory” plots nested within the same block), paired t-tests were performed to examine significant differences in soil properties and fine root biomass between the two treatments. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all inferences. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Fine Root Biomass and Soil Properties

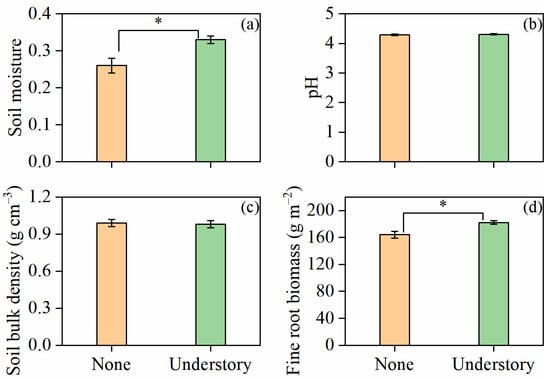

The results suggest that fine root biomass was influenced by understory vegetation management. Compared with the none treatment, the understory treatment significantly reduced fine root biomass (p < 0.05; Figure 1d). Except for soil pH and soil bulk density, which showed no significant differences between the two treatments, understory treatment significantly increased soil moisture by 26% (p < 0.05; Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Soil moisture (a), soil pH (b), soil bulk density (c), and fine root biomass (d) under different understory vegetation treatments. Values represent means ± standard error (n = 8). Asterisks (*) denote significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

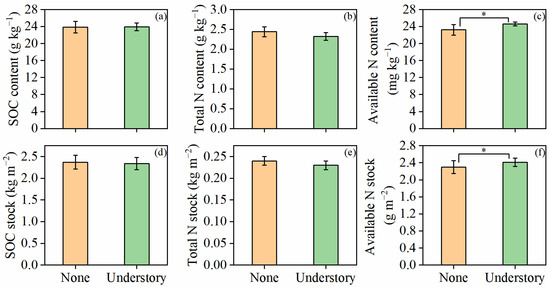

3.2. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen

SOC and total N did not respond significantly to understory vegetation management. No significant differences were observed between the two treatments in terms of both their content and stock (p > 0.05; Figure 2a,b,d,e). However, understory vegetation significantly increased the content (6%) and stock (4.8%) of available N (p < 0.05; Figure 2c,f).

Figure 2.

Contents and stocks of soil organic carbon (SOC) (a,d), total nitrogen (N) (b,e), and available N (c,f) under different understory vegetation treatments. Values are presented as means ± standard error (n = 8). Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

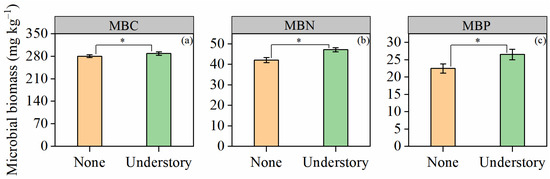

3.3. Soil Microbial Biomass

Soil microbial biomass C (MBC), N (MBN), and P (MBP) exhibited consistent responses to understory vegetation management. Compared with the none treatment, the understory treatment significantly increased the contents of MBC, MBN, and MBP by 2.9%, 12.1%, and 18.1%, respectively (p < 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Contents of soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) (a), nitrogen (MBN) (b), and phosphorus (MBP) (c) under different understory vegetation treatments. Values are expressed as means ± standard error (n = 8). Asterisks (*) denote significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

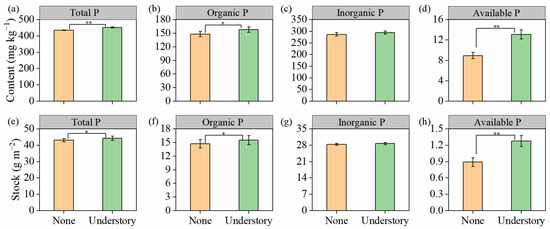

3.4. Soil Phosphorus

Soil P exhibited high sensitivity to understory vegetation management. With the exception of inorganic P, for which no significant difference was observed between the two treatments, the other P fractions showed significant differences. Specifically, the understory treatment significantly increased the contents and stocks of total P, organic P, and available P (p < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Contents and stocks of soil total (a,e), organic (b,f), inorganic (c,g), and available phosphorus (P) (d,h) under different understory vegetation treatments. Values are expressed as means ± standard error (n = 8). Asterisks (*) denote significant differences (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Soil C

Contrary to our a priori hypotheses, our results revealed no significant differences in soil organic C (SOC) content or stocks between the understory vegetation retention and exclusion treatments. This indicates that understory vegetation exerted no substantial influence on SOC concentration or stock, and further underscores the weak responsiveness of the soil C pool to changes in understory vegetation cover within the study region’s forests. However, previous investigations have demonstrated that in certain contexts, retaining understory vegetation can significantly increase topsoil SOC, whereas its removal elicits a pronounced decline [17,18,19,30]. In contrast, our findings align with those from select temperate forest studies, where soil C content did not undergo substantial shifts with the presence or absence of understory vegetation [31,32]. While retaining understory vegetation augmented organic C inputs in this experiment, it failed to enhance SOC pools—a pattern likely driven by enhanced soil respiration that offset the accumulative effect of C inputs [33]. It is widely recognized that understory vegetation supplies labile organic substrates to soil microorganisms via leaf litter, root residues, and exudates, thereby fostering gains in microbial biomass and activity [22]. The significant elevation of microbial biomass C concentration under the understory retention treatment in our study lends empirical support to this paradigm. Understory vegetation may therefore stimulate microbial activity, thereby elevating soil respiration rates and accelerating organic C decomposition. Ultimately, this process offsets the potential accumulation of C from exogenous inputs, resulting in no significant differences in SOC concentration or stock between the two treatments.

An alternative plausible mechanism is that a dynamic balance between C inputs and outputs was established under the understory exclusion treatment (None) [34]. In this study, the exclusion treatment not only removed all aboveground understory vegetation but also the entire surface litter layer. This disturbance likely facilitated the root proliferation of overstory trees into the soil space previously occupied by the understory, with elevated C inputs (e.g., via increased root exudation) partially compensating for C losses associated with vegetation removal. Meanwhile, residual understory roots persisted in decomposing within the soil, thereby releasing labile organic C [35]. Collectively, the combined contributions of increased tree root C inputs and C released from decomposing understory residues may have effectively offset the C loss induced by understory removal. Ultimately, this balance resulted in no significant differences in SOC concentration or stock between the two treatments.

The third plausible reason for the lack of significant change in SOC within the 0–10 cm layer is the translocation of C fractions to deeper soil horizons (>10 cm), which inhibits their accumulation in the topsoil. This phenomenon occurs because the highly mobile dissolved organic C (DOC), originating from understory root exudates and litter decomposition, penetrates below 10 cm through macropore or matrix flow. In line with this observation, Wu et al. [34] reported that there was no significant increase in forest SOC within the 0–10 cm layer despite continuous C input. This was mainly because the highly mobile DOC steadily migrated to the 10–80 cm depth range through macropores, thus maintaining a dynamic equilibrium of SOC in the topsoil [34].

4.2. Changes in Soil N

Previously, researchers have documented in tree girdling experiments and root-free soil systems that soil available N content increases as plant N uptake declines [2,36,37]. However, our study failed to replicate this pattern. Instead, we found that soil available N content was elevated when understory vegetation remained intact, indicating that available N released from plant root exudates and soil organic matter decomposition surpassed plant N uptake.

Notably, while available N content was significantly higher in understory retention plots than in understory removal plots, no significant differences in soil total N concentration or stocks were observed between the two treatments. This implies that the forest soil N pool in the study region was not substantially modulated by the presence or absence of understory vegetation. This observation could be explained by the dual role of understory vegetation in mediating N cycling: on the one hand, it assimilates soil N via growth, and on the other hand, it promotes N accumulation through litterfall and root exudation. In our study, understory removal reduced plant N uptake but concurrently decreased organic matter inputs, which in turn inhibited soil N mineralization and accumulation [8,9]. Meanwhile, roots of dominant overstory trees may have rapidly colonized the vacated soil niches, buffering the changes in the soil N pool. In contrast, in understory-retained plots, continuous organic matter input facilitated N accumulation, but this input also enhanced microbial biomass N (MBN) by improving C substrate availability. Increased MBN further strengthened microbial activity and N turnover, promoting greater N loss as N2O [38,39]. Ultimately, these counteracting processes offset the N accumulation effect, leading to stable soil total N content across the two treatments.

Another important reason for the lack of significant difference in total N storage in the 0–10 cm soil layer between understory-retained and understory-removed plots may be related to N leaching or vertical translocation to deeper soil layers, coupled with the limitation of our shallow sampling depth. For plots with retained understory vegetation, understory root decomposition and root exudation undoubtedly increase N input to the soil [8,9], which would theoretically promote N accumulation in the topsoil. However, the enhanced organic matter input may also increase the availability of labile N (e.g., nitrate-N produced by microbial nitrification) and improve soil porosity through root penetration and organic matter decomposition [8,9,40]. These changes facilitate the downward movement of N via macropore flow or matrix flow. As a result, the additional N input from understory vegetation did not accumulate significantly in the topsoil layer. In contrast, understory removal reduced N input from litter and roots, and the lack of understory root uptake also limited the vertical movement of N to some extent. Thus, the total N content in the 0–10 cm layer of both treatments remained relatively balanced. This explanation is supported by previous studies showing that understory vegetation can promote N leaching to deep soil by increasing labile N supply and improving soil permeability [40], and shallow sampling often underestimates the actual effect of vegetation on soil N cycling. Therefore, the vertical translocation of N to unmeasured deep layers, driven by increased N input in understory-retained plots, is likely a key factor masking the potential N accumulation in the 0–10 cm layer, ultimately leading to no significant difference between the two treatments.

4.3. Changes in Soil P

Our results demonstrated that retaining understory vegetation significantly increased the concentration and stock of soil available P, indicating high sensitivity of soil available P to the presence of understory vegetation [7]. The elevation of available P content likely stemmed from enhanced microbial activity, which was promoted by increased C and nutrient inputs from litter in understory retention plots [11]. This mechanism is supported by empirical evidence: soil microbial biomass P (MBP) was significantly higher in understory retention plots than in exclusion plots. Microorganisms serve as critical sources and sinks of soil available P and are directly involved in organic P mineralization [8,9,11]. Spohn and Kuzyakov (2013) highlighted that in temperate forest soils, microbial P mineralization may be driven by microbial C demand—microorganisms preferentially assimilate C during organic P decomposition, with only minimal P uptake. Under such conditions, P released via mineralization is not fully immobilized by microorganisms but is converted to bioavailable P, thereby enhancing soil P availability [41,42,43,44].

Furthermore, we found that understory retention significantly increased the content and stock of soil total P and organic P. This phenomenon is highly likely to be closely linked to the increase in soil fine root biomass [24]. The buildup of fine roots may have facilitated the uptake of P from deep soil layers by understory vegetation and its translocation to the topsoil [11,40,42,43]. Although partial fine root undergo C mineralization after death, as indicated by increased microbial biomass and a slight (non-significant) rise in total soil organic C (SOC) concentration, P exhibited a distinct accumulation trend in the topsoil.

Consistent with our hypothesis, understory removal resulted in reduced total P, organic P, and available P contents and stocks, which may be attributed to decreased P supply from litter inputs. In contrast to C and N, the biogeochemical cycle of P in natural ecosystems does not rely on atmospheric inputs (e.g., photosynthesis or biological N fixation); its primary short-term source is litter decomposition [10,11]. During ecosystem succession, P is depleted via plant biomass removal, leaching, and erosion [11,44]. In unfertilized soils, such P losses cannot be offset [45,46,47]. Additionally, the absence of understory vegetation may diminish the release of root exudates and the activity of mycorrhizal fungi, thereby further inhibiting P mobilization and transformation processes.

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study used a 10-year, small-scale understory manipulation experiment to reveal how understory vegetation affects soil C, N, and P concentrations and stocks in forests within climate transition zones. However, this field experiment has certain limitations, outlined below: (1) It is restricted to two experimental treatments (vegetation retained/litter removed vs. vegetation + litter removed) without an orthogonal design, precluding the disentanglement of the independent and interactive effects of understory vegetation and litter; (2) the narrow spatial sampling scale constrains the generalizability of the results; (3) despite a 10-year manipulation, the timeframe is still inadequate to capture long-term soil C/N/P dynamics (soil biogeochemical processes typically operate on decadal to centennial scales); (4) sampling was confined to the 0–10 cm topsoil, overlooking vertical nutrient migration and transformation in deep soil horizons (>10 cm). Future research should: (1) implement an orthogonal design (vegetation × litter) incorporating additional replicates and treatment levels; (2) broaden the spatial sampling scope to enhance generalizability across heterogeneous forest habitats; (3) prolong long-term monitoring or integrate chronosequence data to capture cumulative biogeochemical responses; (4) perform soil profile sampling (e.g., 0–100 cm) to quantify vertical C/N/P distribution and migration. These adjustments will strengthen the robustness of inferences regarding understory vegetation’s role in soil nutrient cycling.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the effects of understory vegetation on soil C, N, and P pools via a 10-year manipulation experiment in a coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest. Key findings are as follows: Understory vegetation had no significant impacts on SOC and total N concentrations and stocks. This is due to the counterbalance between increased organic C input and stimulated microbial respiration, as well as the counterbalancing effects of understory vegetation on N uptake and return, which together maintain stable soil C and N pools. In contrast, retaining understory vegetation significantly increased total P, organic P, and available P concentrations and stocks. This is mainly driven by microbial activity enhancement (promoting organic P mineralization) and increased fine root biomass (facilitating deep soil P uptake and translocation to the topsoil). Removal of understory vegetation reduced litter-derived P supply and inhibited P activation, decreasing soil P pools. Overall, understory vegetation exerts differential effects on soil C, N, and P cycling: negligible for C and N pools but pivotal for enhancing P pools and bioavailability. These findings support retaining understory vegetation as a low-cost ecological measure to alleviate soil P limitation, providing a scientific basis for vegetation management in temperate coniferous–broadleaf mixed forests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and S.F.; Data curation, Q.H.; Formal analysis, X.G.; Funding acquisition, X.G.; Investigation, X.G. and Q.H.; Methodology, X.G.; Project administration, S.F.; Resources, S.F.; Supervision, Y.Y. and S.F.; Validation, J.C.; Visualization, X.G. and L.C.; Writing—original draft, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was jointly financed by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M741727), the Xinyang Academy of Ecological Research Open Foundation (No. 2023XYQN14), and the Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Henan Dabieshan National Field Observation and Research Station of Forest Ecosystem.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feng, J.Y.; Li, Z.; Hao, Y.F.; Wang, J.; Ru, J.Y.; Song, J.; Wan, S.Q. Litter removal exerts greater effects on soil microbial community than understory removal in a subtropical-warm temperate climate transitional forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Chen, F.; Wan, S.; Sun, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, J. Understory vegetation plays the key role in sustaining soil microbial biomass and extracellular enzyme activities. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 4481–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Yuan, C.; Wu, Q. Understory vegetation removal significantly affected soil biogeochemical properties in forest ecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 193, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Zhao, F.; Ning, J.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, X.; Zang, H. Impact of understory vegetation on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamic in aerially seeded Pinus massoniana plantations. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Lin, F.; Jiang, C. Understory vegetation management regulates soil carbon and nitrogen storage in rubber plantations. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2023, 127, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Gao, J.J.; Ma, H.X.; Wan, S.Q. Changes in plant litter and root carbon inputs alter soil respiration in three different forests of a climate transitional region. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 358, 110212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.X.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Zhang, Q.F.; Zhou, J.C.; Yue, K.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Fan, Y.X. Keystone bacterial functional module activates P-mineralizing genes to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis of organic P in a subtropical forest soil with 5-year N addition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldpausch, T.; Couto, E.; Rodrigues, L.; Pauletto, D.; Johnson, M.; Fahey, T.; Riha, S. Nitrogen aboveground turnover and soil stocks to 8 m depth in primary and selectively logged forest in southern Amazonia. Global Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1793–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Liang, X.; Duan, B. Understory Vegetation Regulated the Soil Stoichiometry in Cold-Temperate Larch Forests. Plants 2025, 14, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Fu, S. Effects of nitrogen deposition and increased precipitation on soil phosphorus dynamics in a temperate forest. Geoderma 2020, 380, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Li, X.G.; Zhao, L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Regulation of soil phosphorus cycling in grasslands by shrubs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Q. Differential factors determine the response of soil P fractions to N deposition in wet and dry seasons in a subtropical Moso bamboo forest. Plant Soil 2024, 498, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Bai, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F. Phosphorus dynamics: From soil to plant. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Cheng, Y. Understory vegetation had important impact on soil microbial characteristics than canopy tree under N addition in a Pinus tabuliformis plantation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 360, 108763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ouyang, S.; Tan, X. Effects of understory vegetation and climate change on forest litter decomposition: Implications for plant and soil management. Plant Soil 2025, 515, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritika; Negi, A.K. The underestimated role of understory vegetation dynamics for forest ecosystem resilience: A review. Plant Ecol. 2025, 226, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, F.; Liang, K.; Liu, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, F.; Yu, M. Understory Vegetation Preservation Offsets the Decline in Soil Organic Carbon Stock Caused by Aboveground Litter Removal in a Subtropical Chinese Fir Plantation. Forests 2024, 15, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.M.; Wang, G.G.; Xu, Z.J. Litter addition and understory removal influenced soil organic carbon quality and mineral nitrogen supply in a subtropical plantation forest. Plant Soil 2021, 460, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xia, H.; Li, Z. Impacts of litter and understory removal on soil properties in a subtropical Acacia mangium plantation in China. Plant Soil 2008, 304, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; van Groenigen, K.; Hungate, B.; Terrer, C.; van Groenigen, J.; Maestre, F.; Elsgaard, L. Long-term nitrogen loading alleviates phosphorus limitation in terrestrial ecosystems. Global Change Biol. 2020, 26, 5077–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fang, S.; Fang, X.; Jin, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, C. Forest understory vegetation study: Current status and future trends. For. Res. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, F. Aboveground litter input alters the effects of understory vegetation removal on soil microbial communities and enzyme activities along a 60-cm profile in a subtropical plantation forest. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 176, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Fan, C.; Zhao, S. Effect of Litter Changes on Soil Microbial Community and Respiration in a Coniferous–Broadleaf Mixed Forest. Ecosystems 2025, 28, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Wu, D.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Fu, S. Canopy and understory nitrogen addition have different effects on fine root dynamics in a temperate forest: Implications for soil carbon storage. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, W. Canopy nitrogen deposition enhances soil ecosystem multifunctionality in a temperate forest. Global Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Zhu, S. CAN Canopy Addition of Nitrogen Better Illustrate the Effect of Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition on Forest Ecosystem? Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Powlson, D.S.; Jenkinson, D.S. Measurement of microbial biomass phosphorus in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1982, 14, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, C.; Tiessen, H.; Stewart, J.W.B. Correction for P-sorption in the measurement of soil microbial biomass P by CHCl3 fumigation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Soil and Agro-Chemistry Analysis; China Agricultural Scio-Technological Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Xiao, W.; Liu, C. Effects of thinning and understorey removal on soil extracellular enzyme activity vary over time during forest recovery after treatment. Plant Soil 2023, 492, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W.; Fu, B. Effects of land-use change on soil total carbon pool: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2026, 396, 110021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Zhao, X.; Ou, Z.; He, R.; Wang, P.; Cao, A. Forest management practices change topsoil carbon pools and their stability. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Spohn, M. Effects of long-term litter manipulation on soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in a temperate deciduous forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, K.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y.; Chai, B. Structure and Stability of Soil Organic Carbon Pools Along Depth in Forests and Grasslands in the Luya Mountains. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 6567–6575. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; He, K.; Zhang, Q.; Han, M.; Zhu, B. Changes in plant inputs alter soil carbon and microbial communities in forest ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 3426–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; He, Y.; Shang, H.; Hu, C.; Duan, C.; Fu, D. Changes in plant carbon inputs alter soil phosphorus dynamics in a coniferous forest ecosystem in subtropical mountain area. Catena 2024, 247, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, B.; Sietio, O.-M.; Strakova, P.; Prommer, J.; Wild, B.; Hagner, M.; Pihlatie, M.; Fritze, H.; Richter, A.; Heinonsalo, J. Plant roots increase both decomposition and stable organic matter formation in boreal forest soil. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Chang, S. Understory N application overestimates the effect of atmospheric N deposition on soil N2O emissions. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, P.; Zhu, K.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, Q. Soil microbial communities as potential regulators of N2O sources in highly acidic soils. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, W.; Hu, P.; Vesterdal, L.; Zhao, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, K. Mosses stimulate soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation during vegetation restoration in a humid subtropical area. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, E.V.; de Oliveira Silva, É.; Duda, G.P. Microbial enzymatic stoichiometry and the acquisition of C, N, and P in soils under different land-use types in Brazilian semiarid. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 220159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.P.; Fang, X. Plant above-ground biomass and litter quality drive soil microbial metabolic limitations during vegetation restoration of subtropical forests. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 220154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Su, F.; Sayer, E.J. Fine root litter quality regulates soil carbon storage efficiency in subtropical forest soils. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 230182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Phosphorus mineralization can be driven by microbial need for carbon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 61, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.W.; Syers, J.K. The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 1976, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Augusto, L.; Goll, D.S.; Ringeval, B.; Wang, Y.; Helfenstein, J.; Huang, Y.; Hou, E. Global patterns and drivers of phosphorus fractions in natural soils. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 4147–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Song, C.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Peng, C. Long-term increase in rainfall decreases soil organic phosphorus decomposition in tropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).