Stand Structure and Successional Pathway in an Artificial Hybrid Pine (Pinus × rigitaeda) Plantation from a Temperate Monsoon Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Field Sampling

2.2.2. Tree-Ring

2.2.3. Environmental and Climatic Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Two-Way Indicator Species Analysis (TWINSPAN)

2.3.2. Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS)

2.3.3. Successional Index (SI)

2.3.4. Coefficient of Variation (CV)

2.3.5. Generalized Additive Model (GAM)

2.3.6. Weibull Survival Function

3. Results

3.1. Overall View of Data

3.2. Structural Attributes of the Stand

3.3. Quadrat Analysis

3.3.1. TWINSPAN

3.3.2. Integrated NMDS Ordination of Vegetation Layers

3.3.3. Layer-Specific NMDS Ordination and Environmental Gradient Patterns

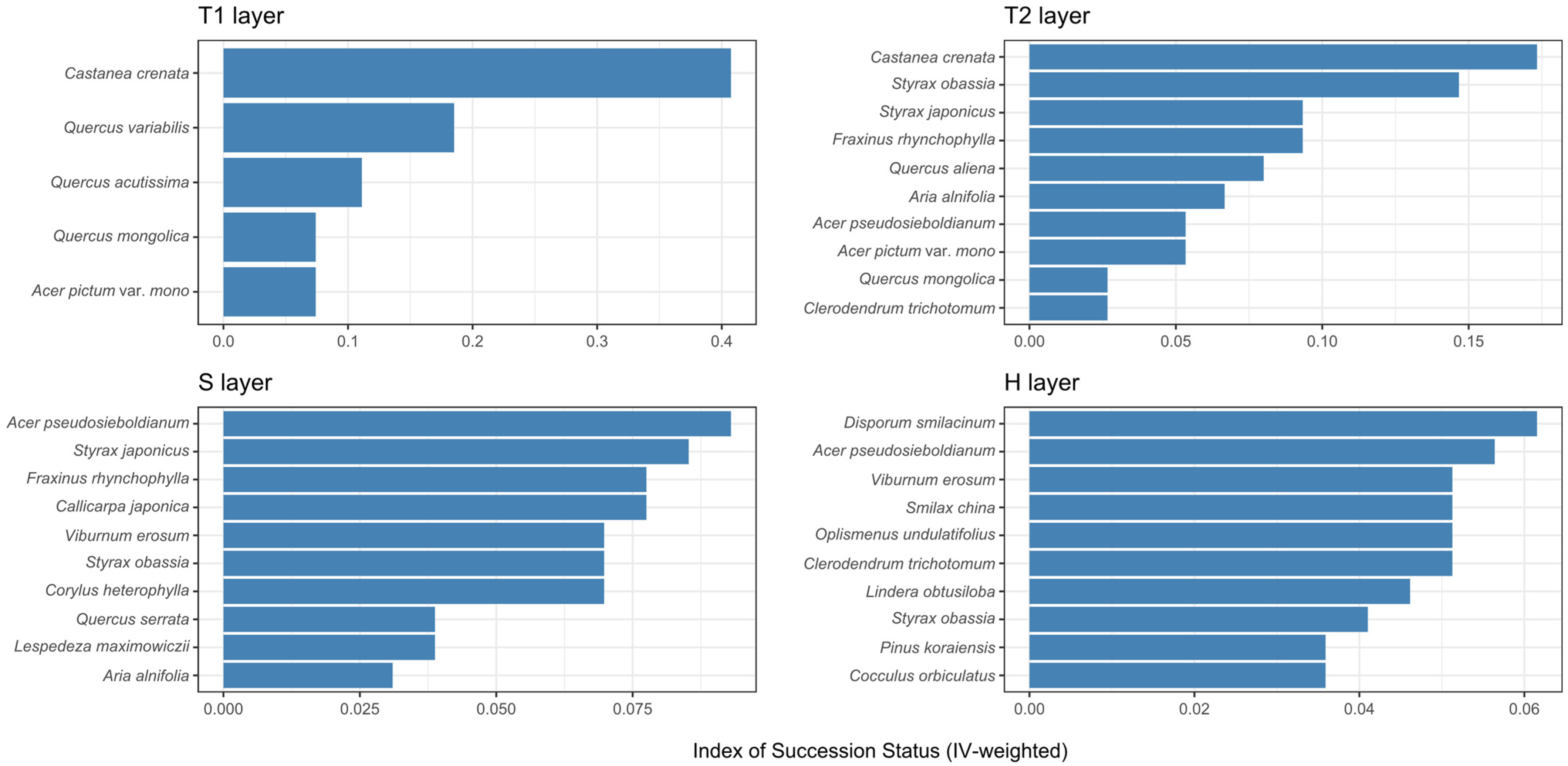

3.3.4. Successional Index (IV-Weighted)

3.4. Tree-Ring Analysis

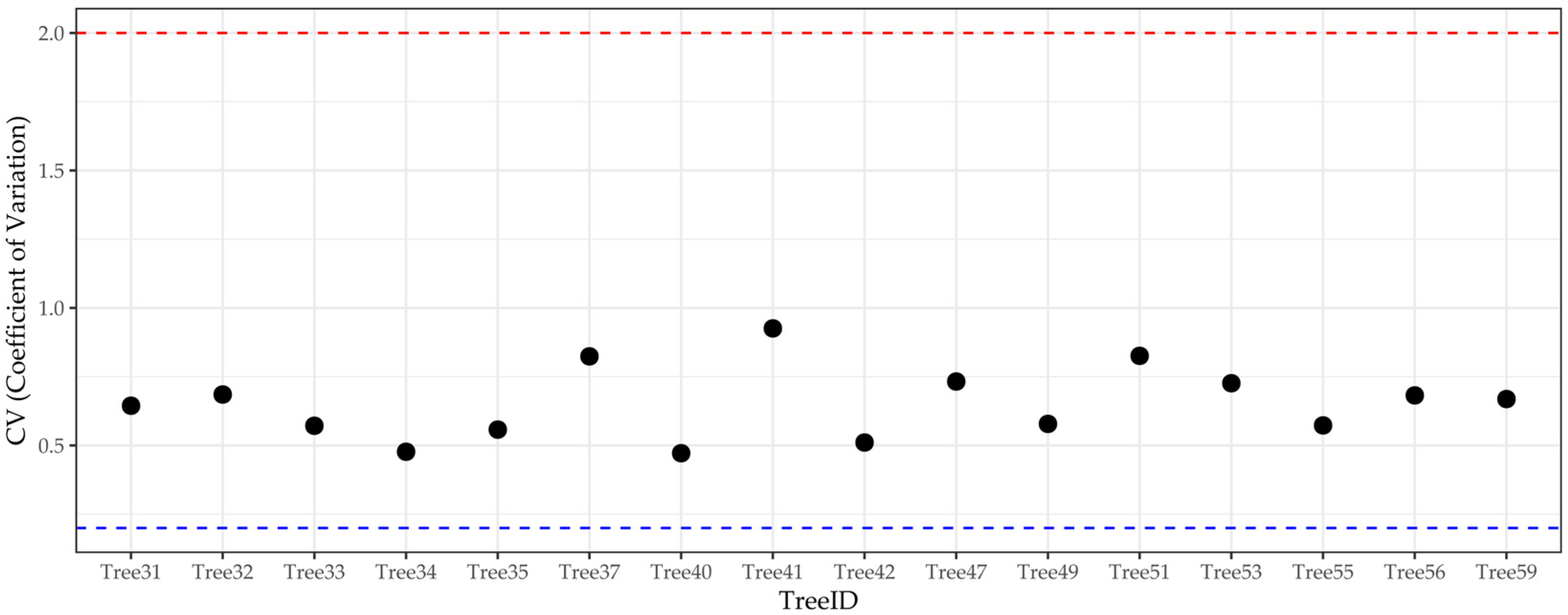

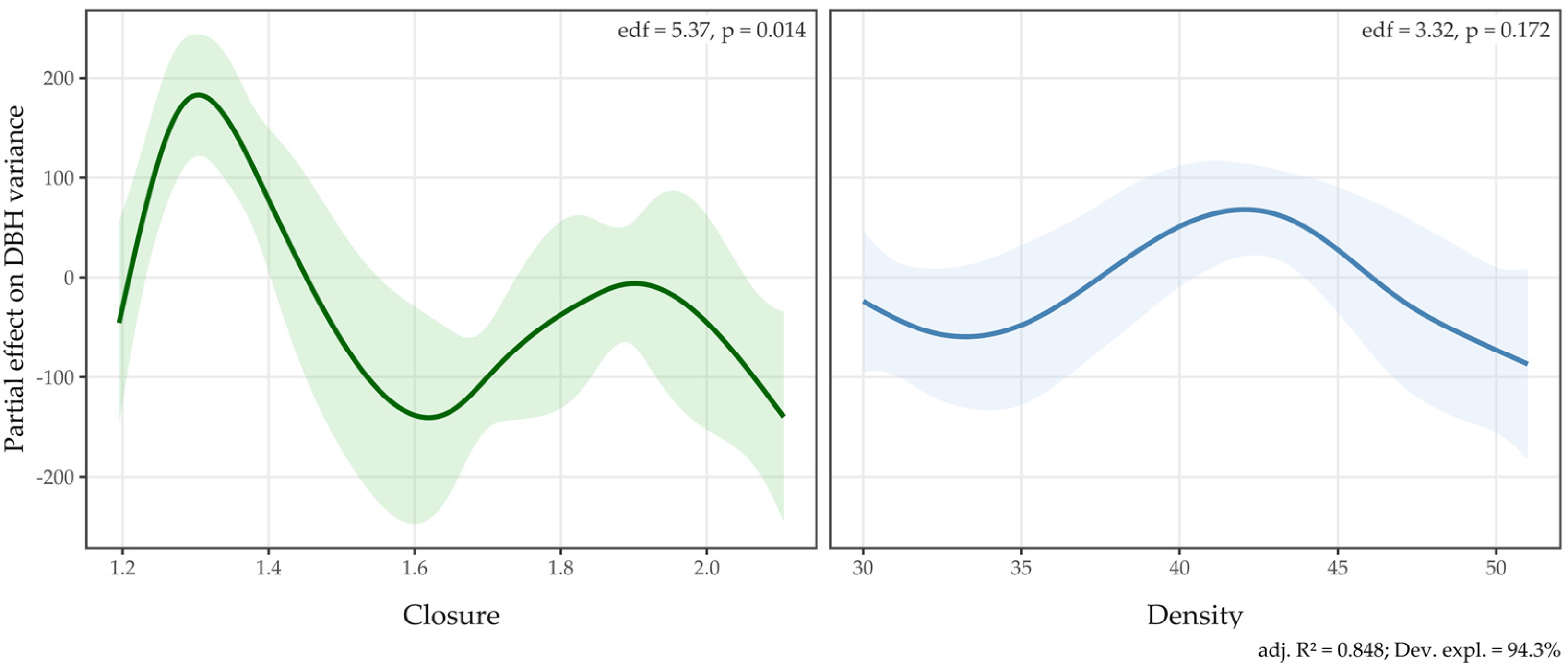

3.4.1. Growth Variability Analysis

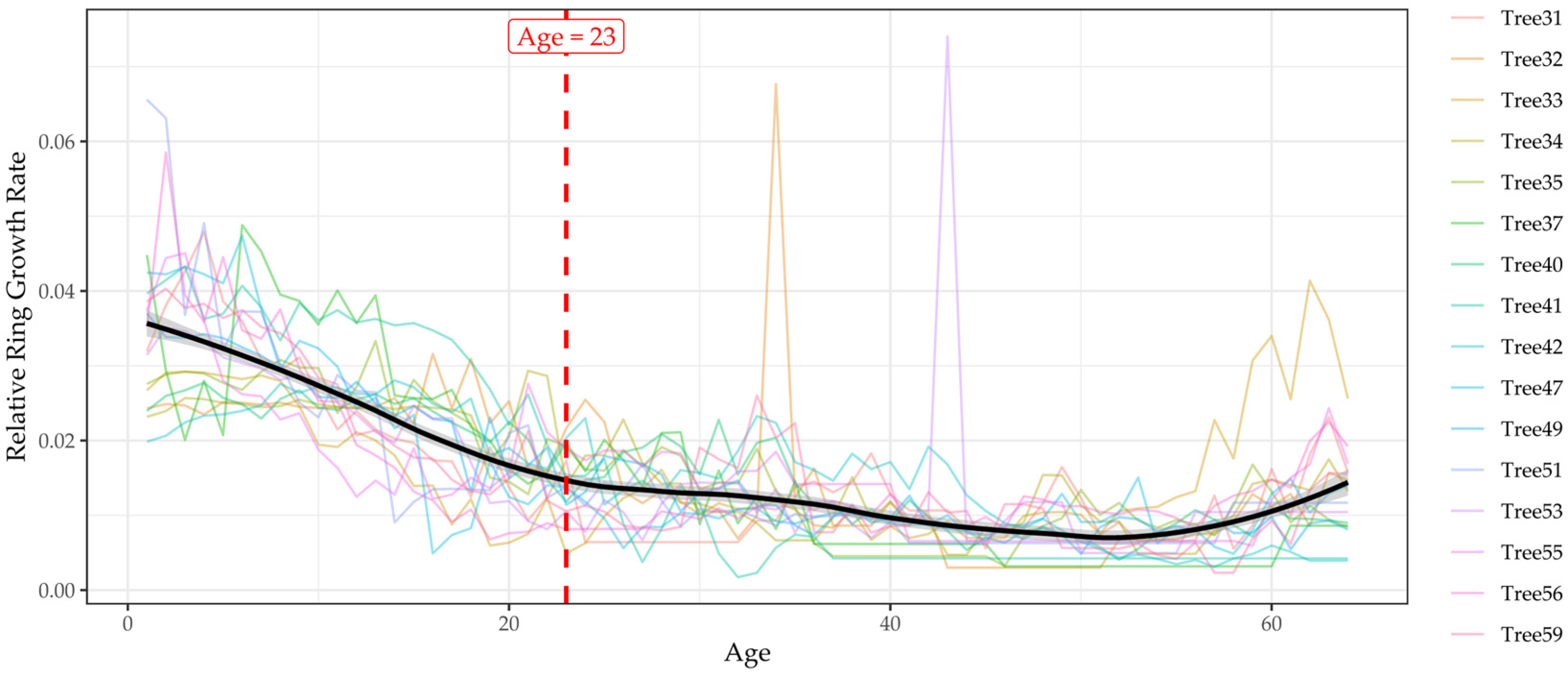

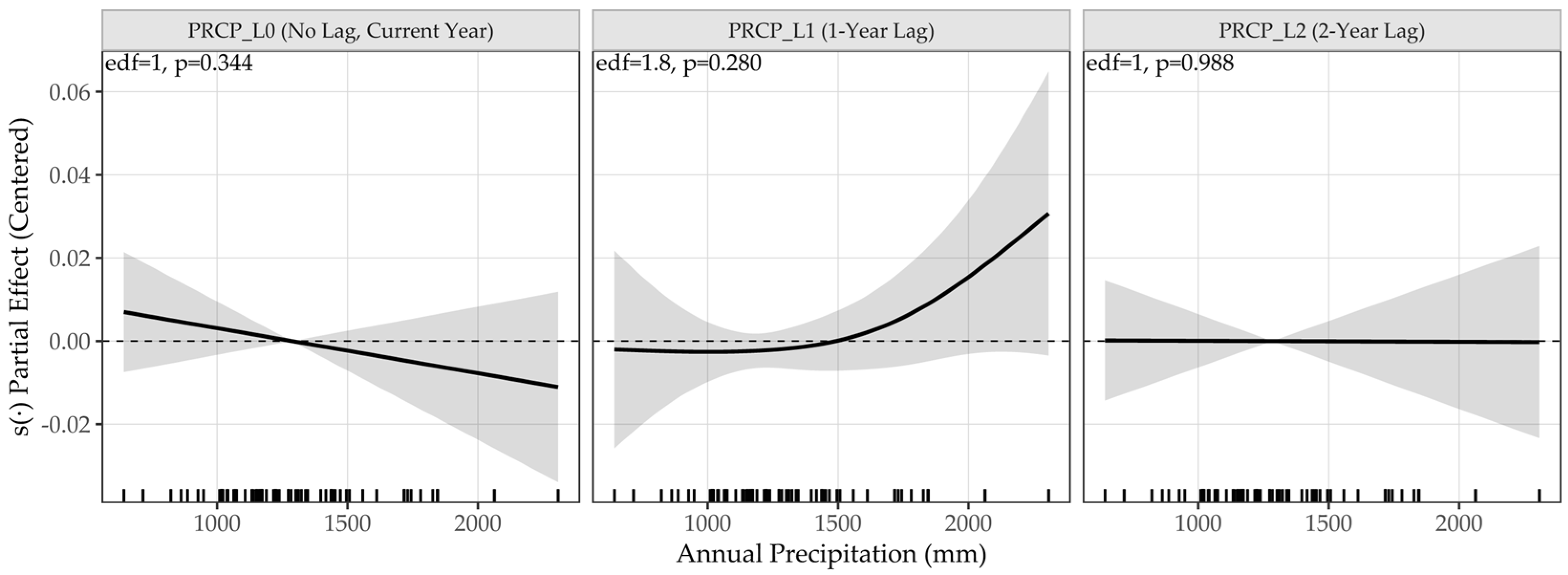

3.4.2. Age-Dependent Growth Dynamics and Climatic Effects

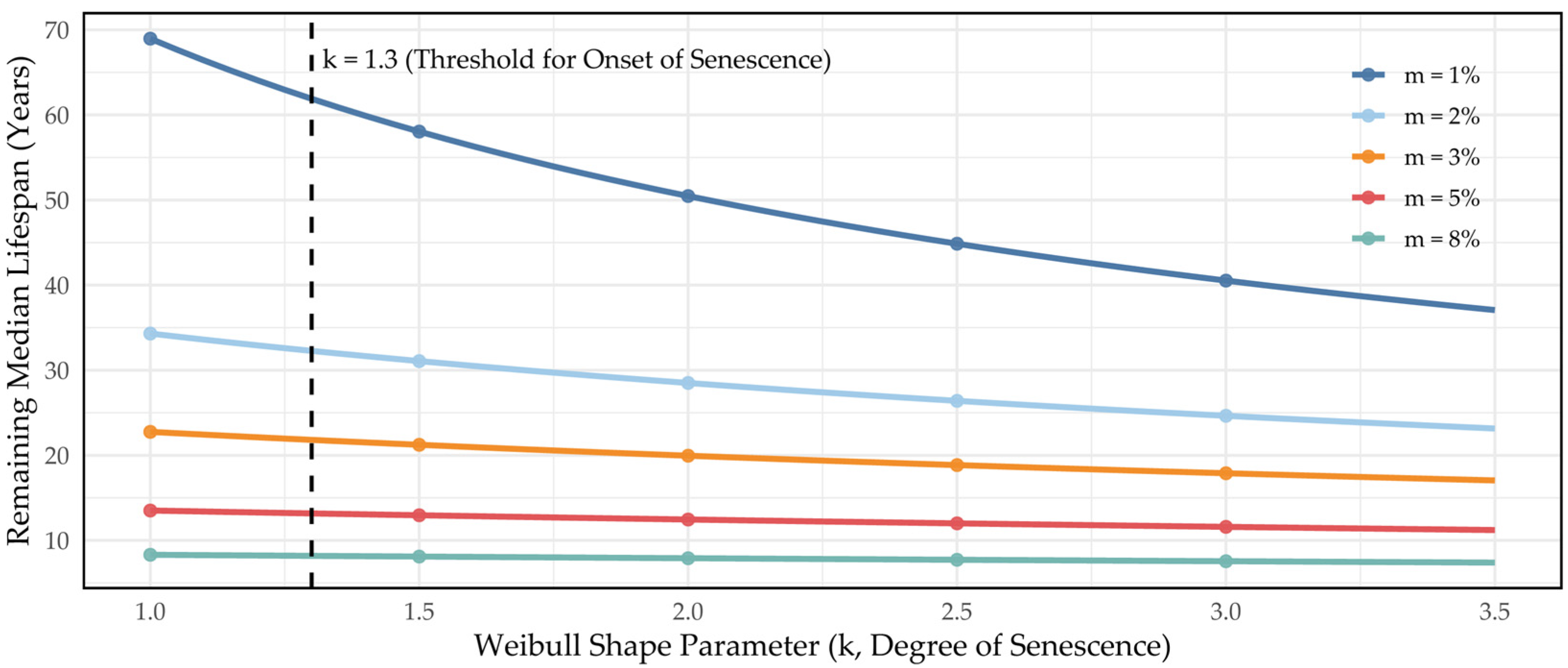

3.4.3. Survival Analysis of Artificial Hybrid Pine Using the Weibull Function

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural and Compositional Transitions Toward Mixed Forests

4.1.1. Vegetation Classification (TWINSPAN)

4.1.2. Structural Heterogeneity (NMDS)

4.1.3. Vertical Ecological Differentiation Across Vegetation Layers (NMDS)

4.1.4. Successional Trajectories (SI Index)

4.2. Growth Decline, Physiological Aging, and Mortality Dynamics

4.2.1. Growth Trend (Tree-Ring)

4.2.2. Longevity and Mortality (Weibull)

4.2.3. Density–Closure Effects (GAM)

4.3. Ecological and Management Implications

- Retain mature P. × rigitaeda individuals as temporary canopy cover to buffer microclimate and stabilize soil,

- Encourage natural regeneration of native hardwoods through selective gap creation, and

- Maintain understory integrity and herb-layer diversity to support seedling recruitment and nutrient cycling.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TWINSPAN | Two-way Indicator Species Analysis |

| NMDS | Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling |

| GAM | Generalized Additive Model |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| CA | Correspondence Analysis |

| SI | Successional Index |

| T1 | Tree 1 (Canopy) |

| T2 | Tree 2 (Subcanopy) |

| S | Shrub |

| H | Herb |

| RGR | Relative Growth Rate |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| IV | Importance Value |

References

- Hyun, S.N.; Ahn, M.S. Artificial hybridization of Pinus rigida Mill. and Pinus taeda L. and the characteristics of Pinus × rigitaeda. Korean J. For. 1965, 28, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service. National Forest Statistics Yearbook 2020; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; An, J.H.; Shin, H.C.; Lee, C.S. Assessment of restoration effects and invasive potential based on vegetation dynamics of Pinus rigida plantation in Korea. Forests 2020, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.C.; Kim, K.S.; Pi, J.H.; Lee, C.S. Restoration effects influenced by plant species and landscape context in Young-il region, Southeast Korea: Structural and compositional assessment on restored forest. J. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.G.; Binkley, D.; Fownes, J.H. Age-related decline in forest productivity: Pattern and process. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1997, 27, 213–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, D.; Stape, J.L.; Ryan, M.G.; Barnard, H.R.; Fownes, J.H. Age-related decline in forest ecosystem growth: An individual-tree, stand-structure, and biogeochemical perspective. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 169, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo, A.E.; Helmer, E.H. Emerging forests on abandoned land: Puerto Rico’s new forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 190, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanowski, J.; Catterall, C.P.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W. Consequences of broadscale timber plantations for biodiversity in cleared rainforest landscapes of tropical and subtropical Australia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 208, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, F.S. The ecological significance of the herbaceous layer in temperate forest ecosystems. BioScience 2007, 57, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Dominant height growth and site index curves for pitch–loblolly hybrid pine (Pinus rigida × P. taeda) plantations. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2002, 91, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y.; Lee, W.K.; Park, S.K.; Kim, K.S.; Oh, M.Y. The suitable site for planting Pinus rigida × P. taeda. J. Korean For. Soc. 1987, 76, 200–205. Available online: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO198716247608666.page (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Kim, C.; Jeong, J.; Cho, H.S.; Son, Y. Carbon and nitrogen status of litterfall, litter decomposition and soil in even-aged larch, red pine and rigitaeda pine plantations. J. Plant Res. 2010, 123, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Society of Forest Science. A Study on the Judgement of Reforestation Site of Pinus rigitaeda and Its Distribution Plan; Final Report of Policy Research Project (2009–2010); Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2010; p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System; Version 3.40; Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2025; Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Korea Forest Service (KFS). Forest Function Classification Map (Thematic Map). Forest Spatial Information Service. 2024. Available online: https://map.forest.go.kr/forest/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Kwon, T.H. Soil Classification of Korean Forest Ecosystems; Korea Forest Research Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H. Forest Soils of Korea; Korean Society of Soil Science and Fertilizer: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie: Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde, 3rd ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Dombois, D.; Ellenberg, H. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Korea National Arboretum. National Standard Plant List in Korea. 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.go.kr/kpni/index.do (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). Korea Meteorological Administration Open Data Portal. 2025. Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Version 4.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Hill, M.O. TWINSPAN: A Fortran Program for Arranging Multivariate Data in an Ordered Two-Way Table by Classification of the Individuals and Attributes; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zelený, D. twinspanR: TWo-Way Indicator Species Analysis (and Its Modified Version) in R, R Package Version 0.22; commit d581f367f5ea67a35a32749ea871d2d36f670312; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://github.com/zdealveindy/twinspanR (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Gauch, H.G.; Whittaker, R.H. Hierarchical classification of community data. J. Ecol. 1981, 69, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, B.; Grace, J.B. Analysis of Ecological Communities; MjM Software: Gleneden Beach, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, M. Vegetation Description and Data Analysis: A Practical Approach, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, J.B. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling: A numerical method. Psychometrika 1964, 29, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchin, P.R. An evaluation of the robustness of techniques for ecological ordination. Vegetatio 1987, 69, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, R Package Version 2.7-2. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Ramsay, J.O. Maximum likelihood estimation in multidimensional scaling. Psychometrika 1977, 42, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C.; Cox, T.F. Dissimilarity analysis: Unifying principle and extensions. J. Multivar. Anal. 2004, 90, 138–165. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, J.T.; McIntosh, R.P. An upland forest continuum in the prairie–forest border region of Wisconsin. Ecology 1951, 32, 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; You, Y.H.; Robinson, G.R. Secondary succession and natural habitat restoration in abandoned rice fields of central Korea. Restor. Ecol. 2002, 10, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Collins, S.L.; Armesto, J.J. A hierarchical consideration of causes and mechanisms of succession. Vegetatio 1987, 69, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klesse, S.; DeRose, R.J.; Guiterman, C.H.; Lynch, A.M.; O’Connor, C.D.; Shaw, J.D.; Evans, M.E.K. Sampling bias overestimates climate change impacts on forest growth in the southwestern United States. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S.; Devlin, S.J. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Generalized Additive Models; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fritts, H.C. Tree Rings and Climate; Academic Press: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Guisan, A.; Edwards, T.C.; Hastie, T. Generalized linear and generalized additive models in studies of species distributions: Setting the scene. Ecol. Model. 2002, 157, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.J.; Miller, D.L.; Simpson, G.L.; Ross, N. Hierarchical GAMs in ecology: An introduction with mgcv. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, J.J.; Gazol, A.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Fajardo, A.; McIntire, E.J.B.; Liang, E. Tree growth and treeline responses to temperature: Different questions and concepts. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheil, D.; May, R.M. Mortality and recruitment rate evaluations in heterogeneous tropical forests. J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadow, K.; Kotze, H. Tree survival and maximum density of planted forests—Observations from South African spacing studies. For. Ecosyst. 2014, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; Dell, T.R. Quantifying diameter distributions with the Weibull function. For. Sci. 1973, 19, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeide, B. Analysis of growth equations. For. Sci. 1993, 39, 594–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monserud, R.A.; Sterba, H. Modeling individual tree mortality for Austrian forest species. For. Ecol. Manag. 1999, 113, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-R.; Son, Y.; Noh, N.J.; Lee, S.K.; Jo, W.; Son, J.A.; Kim, C.; Bae, S.-W.; Lee, S.-T.; Kim, H.-S.; et al. Effect of thinning on carbon storage in soil, forest floor and coarse woody debris of Pinus densiflora stands with different stand ages in Gangwon-do, central Korea. For. Sci. Technol. 2011, 7, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsogt, K.; Zandraabal, T.; Lin, C. Diameter and Height Distributions of Natural Even-Aged Pine Forests (Pinus sylvestris L.) in Western Khentey, Mongolia. Taiwan J. For. Sci. 2013, 28, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 2nd ed.; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, Y.-M.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, C.-S. Vegetation trajectories of Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc.) forests at Mt. Seorak, Korea. J. Plant Biol. 2006, 49, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, Y.; Lee, J.; Cho, S.; Noh, J. Review on the succession process of Pinus densiflora forests in South Korea: Progressive and disturbance-driven succession. J. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 44, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Ahmed, S.; Jacobs, M.; Schmied, G.; Hilmers, T. Linking crown structure with tree ring pattern: Methodological considerations and proof of concept. Trees 2022, 36, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, D.; Son, Y.; Jeong, J. The Influence of Tree Structural and Species Diversity on Temperate Forest Productivity and Stability in Korea. Forests 2019, 10, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, A.; Valentine, H.T. Crown ratio influences allometric scaling in trees. Ecology 2006, 87, 2967–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Piñol, J. Drought-induced mortality and hydraulic architecture in Scots pine populations of the NE Iberian Peninsula. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 161, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.S.; McKenzie, D.; Peterson, D.L.; Westerling, A.L. Climate and wildfire area burned in western U.S. ecoprovinces, 1916–2003. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 1003–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, G.L.; Hafley, W.L.; Buford, M.A. Predicting Mortality with a Weibull Distribution. For. Sci. 1980, 26, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, O.B.; Burkhart, H.E. Modeling Survival of Loblolly Pine Trees in Thinned and Unthinned Plantations. Can. J. For. Res. 1992, 22, 1878–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diéguez-Aranda, U.; Castedo-Dorado, F.; Álvarez-González, J.G.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R. Modelling Mortality of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Plantations in the Northwest of Spain. Eur. J. For. Res. 2005, 124, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T. Size-Structured Tree Populations in Gap-Dynamic Forest: The Forest Architecture Hypothesis for the Stable Coexistence of Species. J. Ecol. 1993, 81, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, L.; Cao, Y.; Wu, D.; Hao, G. Aging Mongolian pine plantations face high risks of drought-induced growth decline: Evidence from both individual tree and forest stand measurements. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.W.; Ratkowsky, D.A.; Davis, A.W. Problems of Hypothesis Testing of Regressions with Multiple Measurements from Individual Sampling Units. For. Ecol. Manag. 1984, 7, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeide, B. A Relationship between Size of Trees and Their Number. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 72, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Forrester, D.I.; Bauhus, J. Mixed-Species Forests: Ecology and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, Y.; Lee, B.-C.; Cho, J.-H.; Lee, K.-S.; Jang, I.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Hong, S.-K.; Jung, H.-C.; Choung, H.-L. Forest responses to the large-scale east coast fires in Korea. Ecol. Res. 2004, 19, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, U. Forest litter and shrubs act as an understory filter for the survival of Quercus mongolica seedlings in Mt. Kwan-ak, South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, Y.-M.; Park, S.-A.; Lee, C.-S. Structure and dynamics of Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora) stands established as riparian vegetation at the Tsang Stream in Mt. Seorak National Park, Eastern Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 30, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, B.; Cho, D. Comparison of stand structure and growth characteristics between Pinus koraiensis plantation and natural oak stands in Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 46, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H. Gradient analysis of vegetation. Biol. Rev. 1967, 42, 207–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condit, R.; Engelbrecht, B.M.J.; Pino, D.; Pérez, R.; Turner, B.L. Species Distributions in Response to Individual Soil Nutrients and Seasonal Drought across a Community of Tropical Trees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5064–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.F.; Scheffers, B.R. Vertical Stratification Influences Global Patterns of Biodiversity. Ecography 2019, 42, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, M.J.; North, M.P.; Werner, C.M.; Fick, S.E.; Latimer, A.M. Local Forest Structure Variability Increases Resilience to Wildfire in Dry Western U.S. Coniferous Forests. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewel, J.J. Designing Agricultural Ecosystems for the Humid Tropics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1986, 17, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Vanderklein, D.; Mencuccini, M. Tree height and age-related decline in growth in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Oecologia 2007, 150, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, C.; Bugmann, H. Trade-Offs between Growth Rate, Tree Size and Lifespan of Mountain Pine (Pinus montana) in the Swiss National Park. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmking, M.; van der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; van der Maaten, E.; Scharnweber, T.; Buras, A.; Biermann, C.; Gurskaya, M.; Hallinger, M.; Lange, J.; Shetti, R.; et al. Global assessment of relationships between climate and tree-ring growth: Non-stationarity challenges for forest productivity projections. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.G.; Lee, W.K.; Kim, M.; Kwak, D.A.; Kwak, H.; Park, T.; Byun, W.H.; Son, Y.; Choi, J.K.; Lee, Y.J.; et al. Radial Growth Response of Pinus densiflora and Quercus spp. to Topographic and Climatic Factors in South Korea. J. Plant Ecol. 2013, 6, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, A.; Pederson, N.; Baliva, M.; Brunetti, M.; Dinella, A.; Kitamura, K.; Knapp, H.D.; Schirone, B.; Piovesan, G. The longevity of broadleaf deciduous trees in Northern Hemisphere temperate forests: Insights from tree-ring series. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houminer, N.; David-Schwartz, R.; Lloret, F.; David, A.; Klein, T. Comparison of morphological and physiological traits between Pinus halepensis, Pinus brutia and their hybrids under drought. Forests 2022, 13, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, H.S. Pine Hybrids—A Review of Their Use, Performance and Genetics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 148, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, F.H.; Likens, G.E. Pattern and Process in a Forested Ecosystem; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.F.; Spies, T.A.; Van Pelt, R.; Carey, A.B.; Thornburgh, D.A.; Berg, D.R.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Harmon, M.E.; Keeton, W.S.; Shaw, D.C.; et al. Disturbances and the Structural Development of Natural Forest Ecosystems with Some Implications for Silviculture. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 155, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.D.; Larson, B.C. Forest Stand Dynamics, Update ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Westoby, M. The self-thinning rule. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1984, 14, 167–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J.; Thomas, S.C. Size Variability and Competition in Plant Monocultures. Oikos 1986, 47, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H. Diversity and productivity in forests: Evidence from long-term experimental plots. In Forest Diversity and Function; Scherer-Lorenzen, M., Körner, C., Schulze, E.D., Eds.; Ecological Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 176, pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, A.; Messier, C. The Role of Plantations in Managing the World’s Forests in the Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 8, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, W.; Seol, A.; Jung, S. Stand Structure and Successional Pathway in an Artificial Hybrid Pine (Pinus × rigitaeda) Plantation from a Temperate Monsoon Region. Forests 2025, 16, 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121840

Kim W, Seol A, Jung S. Stand Structure and Successional Pathway in an Artificial Hybrid Pine (Pinus × rigitaeda) Plantation from a Temperate Monsoon Region. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121840

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Woosung, Ara Seol, and Suyoung Jung. 2025. "Stand Structure and Successional Pathway in an Artificial Hybrid Pine (Pinus × rigitaeda) Plantation from a Temperate Monsoon Region" Forests 16, no. 12: 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121840

APA StyleKim, W., Seol, A., & Jung, S. (2025). Stand Structure and Successional Pathway in an Artificial Hybrid Pine (Pinus × rigitaeda) Plantation from a Temperate Monsoon Region. Forests, 16(12), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121840