Overexpression of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Gene, ZeF3H, from Zelkova schneideriana Enhanced Plant Tolerance to Chilling Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Treatment

2.2. Gene Expression Parttern of ZeF3H in Zelkova schneideriana

2.3. Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis of ZeF3H Gene

2.4. The Construction of the Expression Vector and Gene Transformation

2.5. Physiological Index Measurement

2.6. Evans Blue Staining Experiment

3. Results

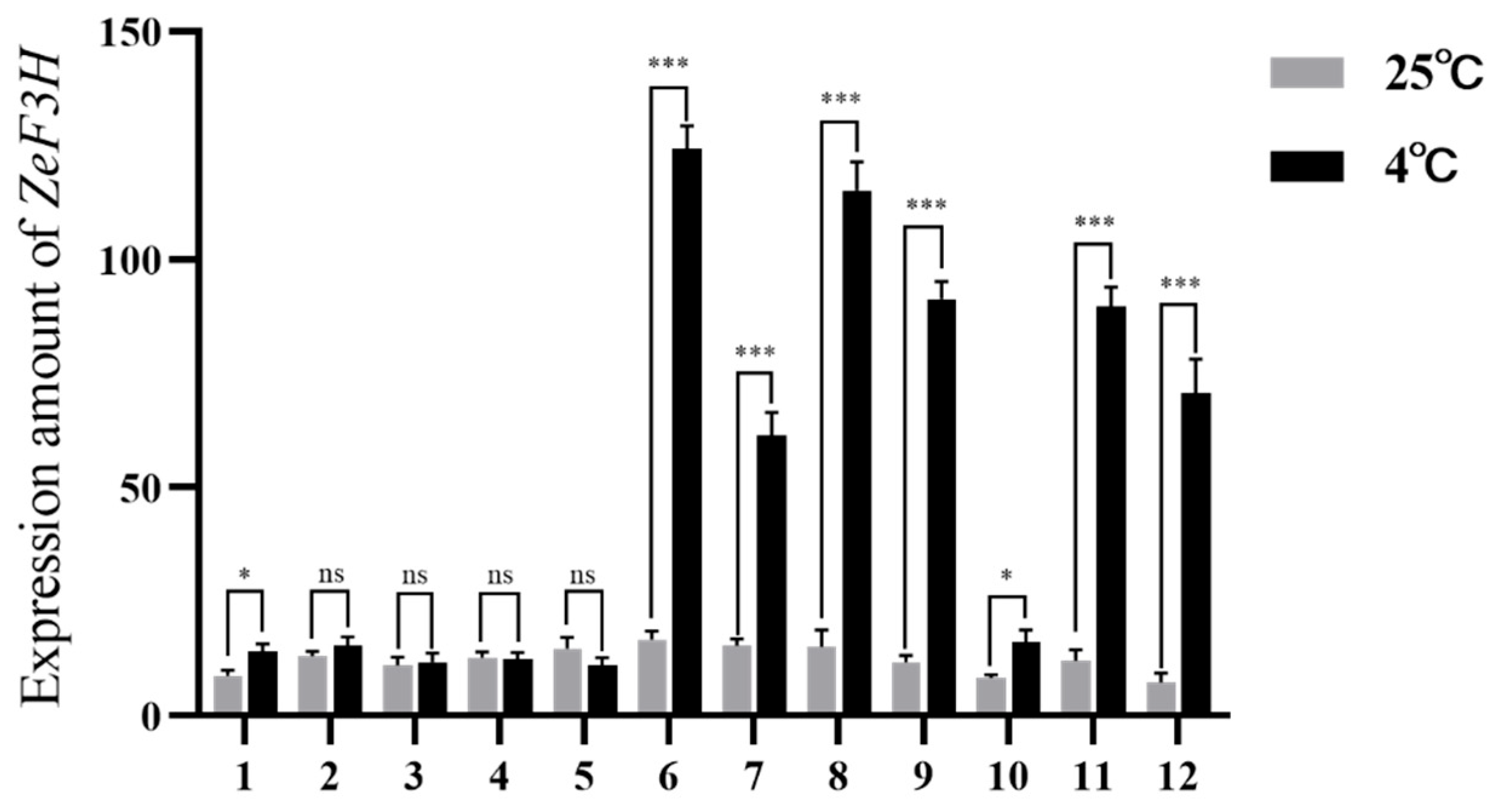

3.1. Expression Pattern of ZeF3H in Z. schneideriana

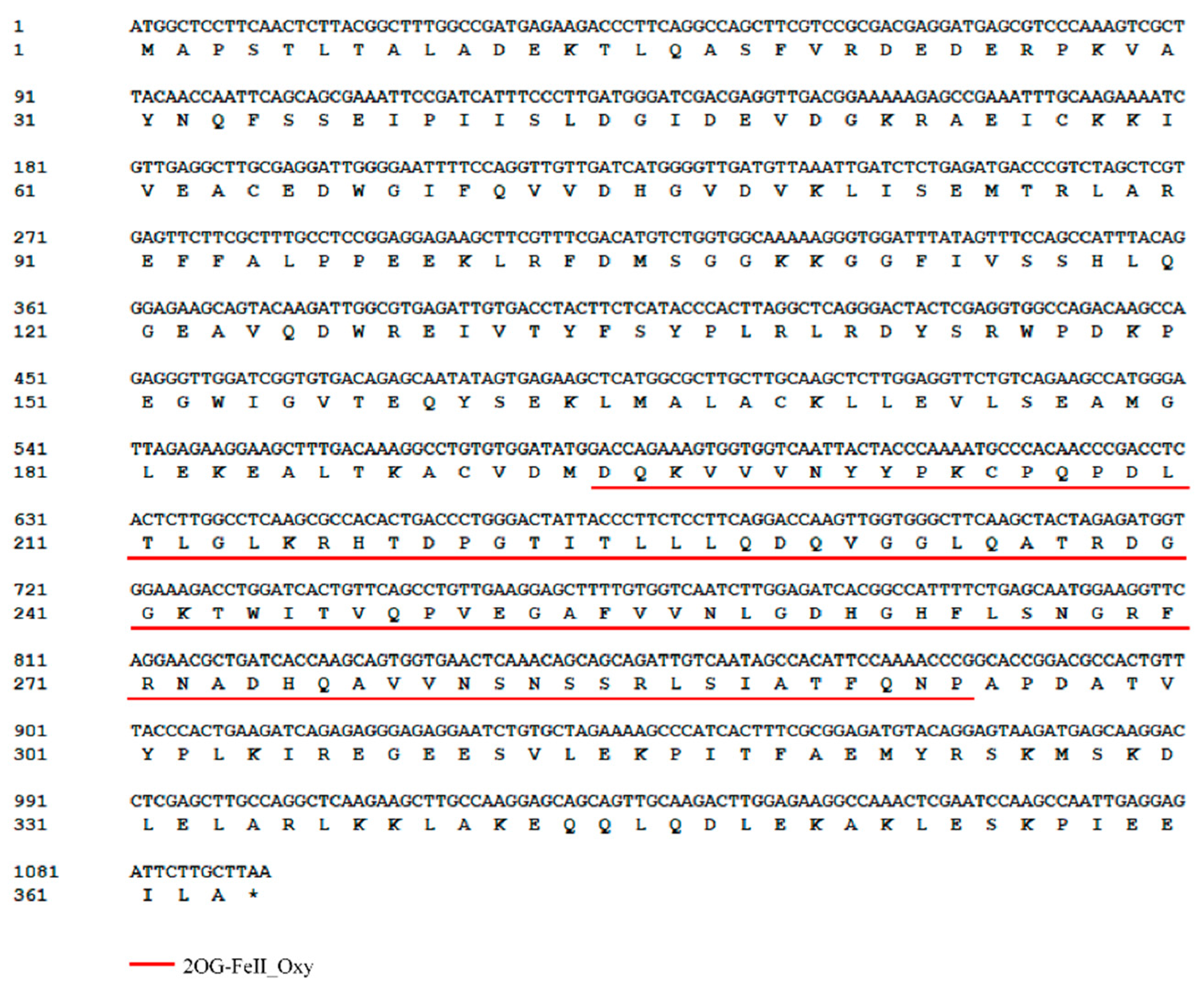

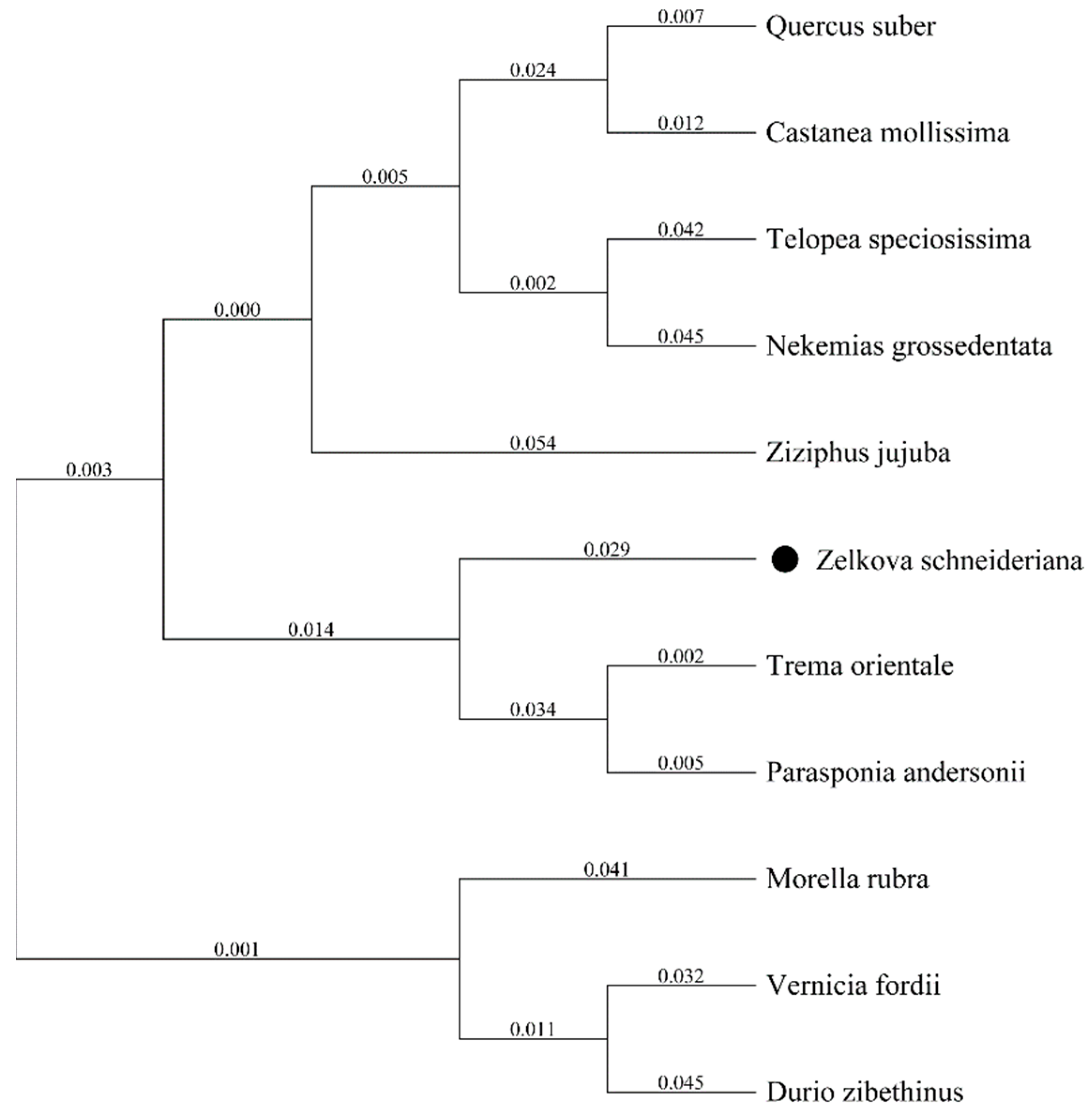

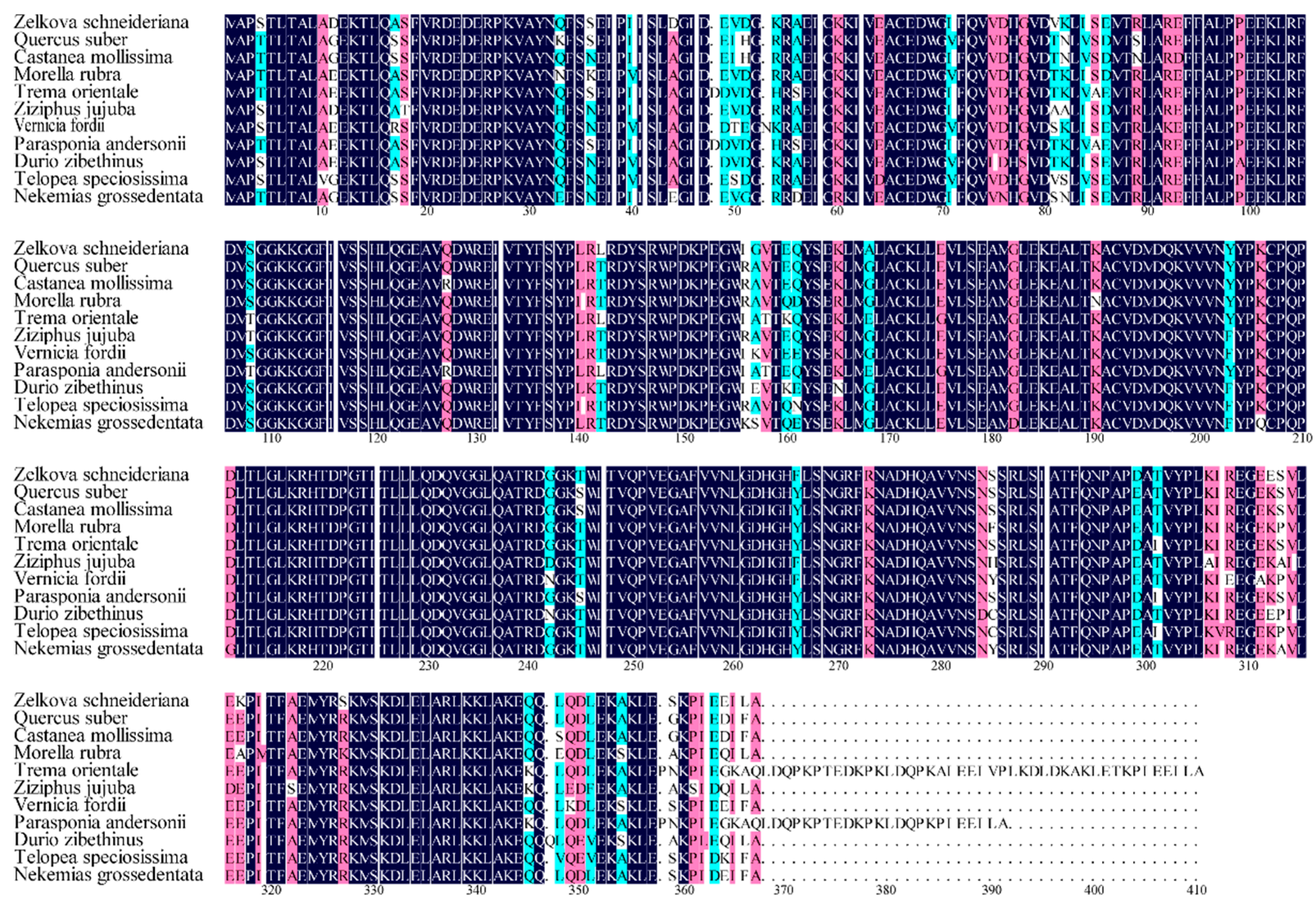

3.2. Characteristics of ZeF3H

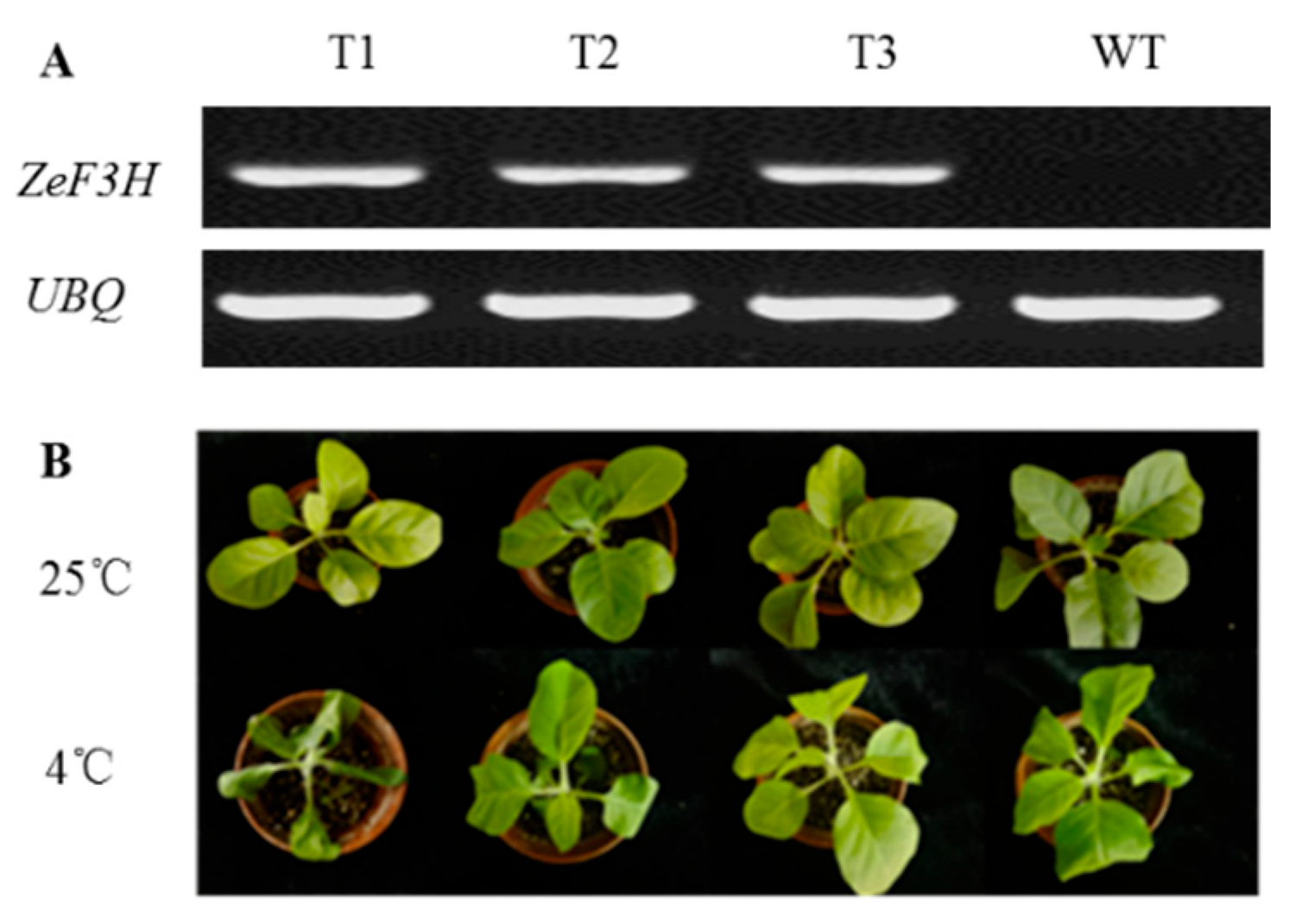

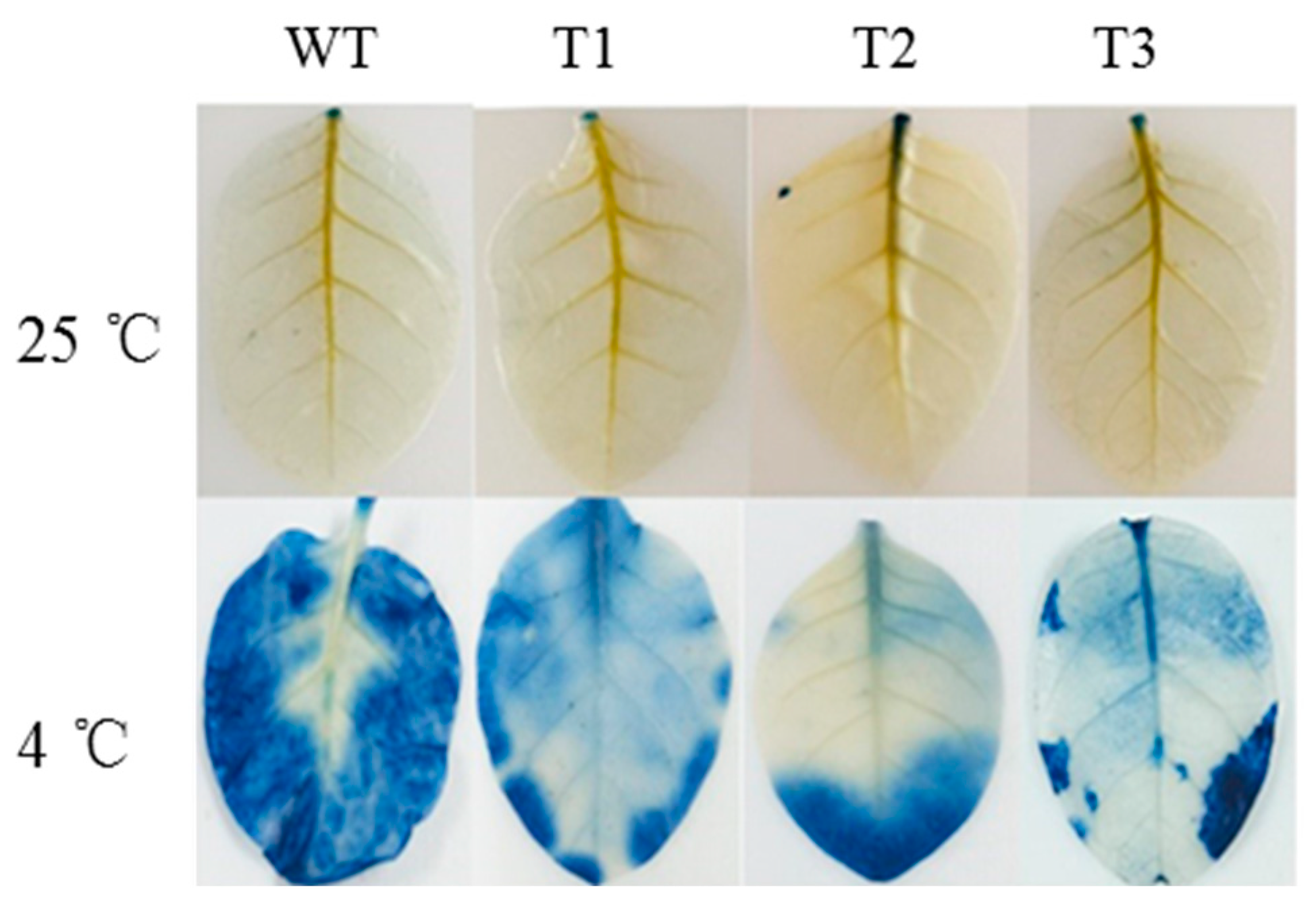

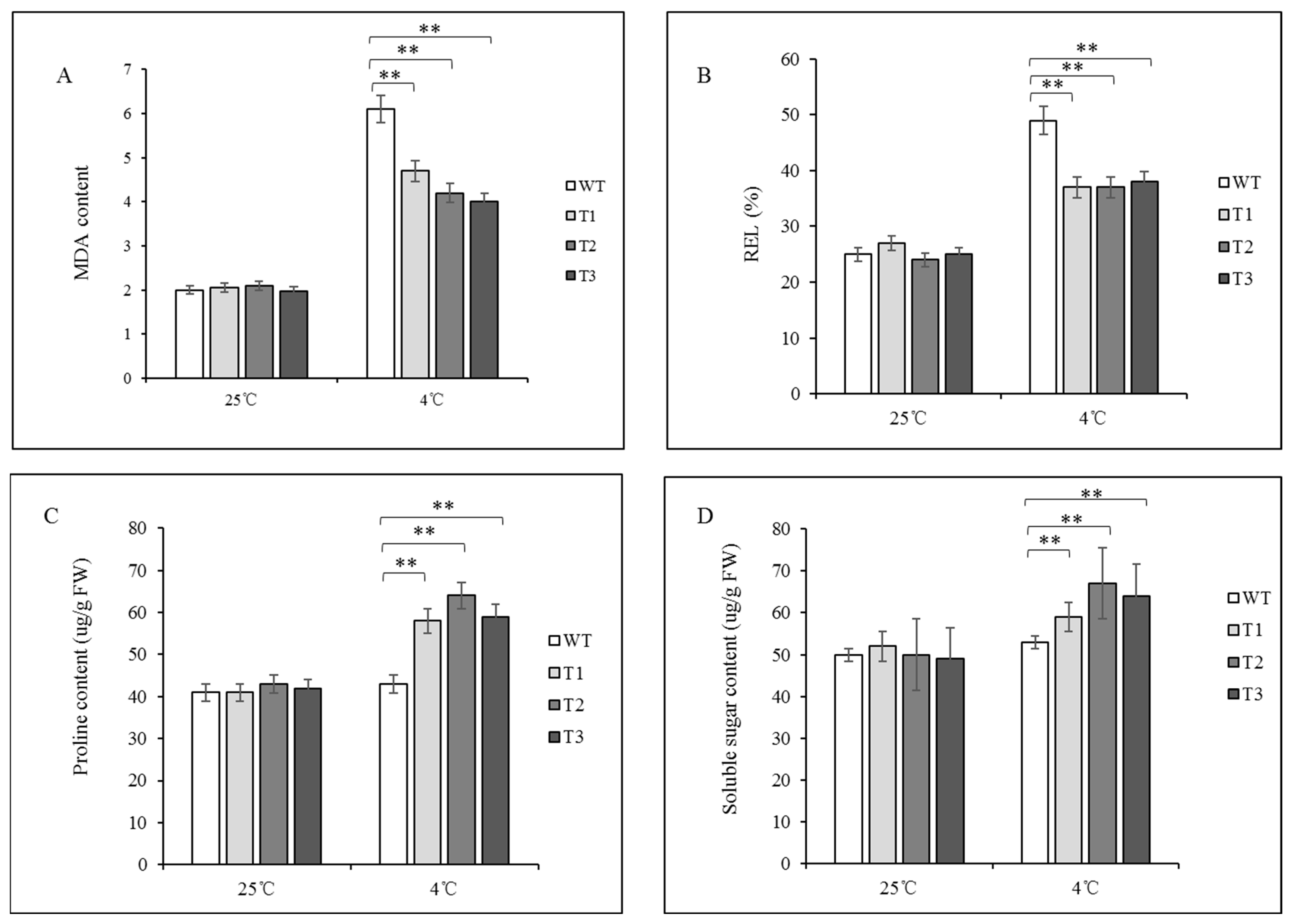

3.3. ZeF3H Enhanced Plant’s Tolerance to Chilling Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, J.; Han, W.; Wang, M. Ultraviolet and environmental stresses involved in the induction and regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis: A review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 4966–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effects of stress. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrussa, E.; Braidot, E.; Zancani, M.; Peresson, C.; Bertolini, A.; Patui, S.; Vianello, A. Plant flavonoids-biosynthesis, transport and involvement in stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 14950–14973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhai, J.; Shao, L.; Lin, W.; Peng, C. Corrigendum: Accumulation of anthocyanins: An adaptation strategy of Mikania micrantha to low temperature in winter. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1049, Erratum in Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fan, R.; Sun, G.; Sun, T.; Fan, Y.; Bai, S.; Guo, S.; Huang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Flavonoids improve drought tolerance of maize seedlings by regulating the homeostasis of reactive oxygen species. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, M.; Jin, J.; Yu, K.; Zhang, J.; Cao, F. Comprehensive evaluation of drought tolerance of six Chinese chestnut varieties (clones) based on flavonoids and other physiological indexes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Yu, H.; Guo, H.; Lin, T.; Kou, L.; Wang, A.; Shao, N.; Ma, H.; Xiong, G. Transcriptional regulation of strigolactone signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature 2020, 583, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Fan, R.; Fan, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Song, C. The flavonoid biosynthesis regulator PFG3 confers drought stress tolerance in plants by promoting flavonoid accumulation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 196, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Duan, H.; Li, Y.; Tie, L.; Ding, G. The PmCHS and PmANR of Pinus massoniana regulate flavonoid metabolism in response to high temperatures and drought. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Wang, Y.; Dai, L.; Jiang, K.; Zeng, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L.; Bian, C.; Liu, Q. The transcription factor GmbZIP131 enhances soybean salt tolerance by regulating flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, 092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.U.; Park, J.I.; Jung, H.J.; Yang, T.J.; Hur, Y.; Nou, I.S. Characterization of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) genes and their association with cold and freezing stress in Brassica rapa. Gene 2014, 550, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Evolutionary dynamic analyses on monocot flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase gene family reveal evidence of plant-environment interaction. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Ahn, J.H. Accumulation of flavonols in response to ultraviolet-B irradiation in soybean is related to induction of flavanone 3-beta-hydroxylase and flavonol synthase. Mol. Cells 2008, 25, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Li, J.; Xing, M.; Grierson, D.; Sun, C.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Chen, K. Hydroxylation decoration patterns of flavonoids in horticultural crops: Chemistry, bioactivity and biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, 068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, M.; Yamada, E.; Saito, M.; Fujita, K.; Takahashi, H.; Nakatsuka, K. Molecular characterization of mutations in white-flowered torenia plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Rani, A.; Kumar, S.; Sood, P.; Mahajan, M.; Yadav, S.K.; Singh, B.; Ahuja, P.S. An early gene of the flavonoid pathway, flavanone 3-hydroxylase, exhibits a positive relationship with the concentration of catechins in tea (Camellia sinensis). Tree Physiol. 2008, 28, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; WS Jia, W.; Wang, H.; Xiao, M. RNAi-mediated silencing of the flavanone 3-hydroxylase gene and its effect on flavonoid biosynthesis in strawberry fruit. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 32, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Kang, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, R.; Chao, N.; Liu, L. Functional characterization of flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) and its role in anthocyanin and flavonoid biosynthesis in mulberry. Molecules 2022, 27, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Diao, J.; Ji, J.; Wang, G.; Guan, C.; Jin, G.; Wang, Y. Molecular cloning and identification of a flavanone 3-hydroxylase gene from Lycium chinense, and its overexpression enhances drought stress in tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 98, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, C.; Dong, W.; da Silva, J.A.T.; He, C.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Huang, L.; Zhao, C.; Zeng, D.; Li, C.; et al. Functional analysis of flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) from Dendrobium officinale, which confers abiotic stress tolerance. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Cao, H.; Zeng, Q.; Guo, X.; Shao, H.; Wang, H.; Luo, L.; Yue, C.; Zeng, L. Integrated physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analysis reveals mechanism underlying the Serendipita indica-enhanced drought tolerance in tea plants. Plants 2025, 14, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, B.; Xu, K. Interaction of nitric oxide and polyamines involves antioxidants and physiological strategies against chilling-induced oxidative damage in Zingiber officinale Roscoe. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 170, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Lee, H. Evaluation of freezing injury in temperate fruit trees. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, K.; Liang, R. Research progress on efficient cultivation, development and utilization of the precious fast growing tree Zelkova schneideriana. For. Sci. Technol. 2024, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, J. Genome-wide profiling of the genes related to leaf discoloration in Zelkova schneideriana. Forests 2024, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Xie, B.; Xu, J. The expansin gene PttEXPA8 from poplar (Populus tomentosa) confers heat resistance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016, 126, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. Combined drought and heat stress in Camellia oleifera cultivars: Leaf characteristics, soluble sugar and protein contents, and Rubisco gene expression. Trees 2015, 29, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldeen, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1963, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, R.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, J. Over-expression of PttEXPA8 gene showed various resistances to diverse stresses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Zhang, S.; Gu, Y.; Hu, H.; Sun, L.; Lu, C.; Warburton, M.L.; Li, H.; Zhu, J. Systematic analysis of the F3H family in maize reveals a role for ZmF3H6 in salt stress tolerance. New Crops 2026, 3, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Zhang, S.; Deng, Y.; Wang, G.; Kong, F. Overexpression of a tomato flavanone 3-hydroxylase-like protein gene improves chilling tolerance in tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. Functional Study of Tobacco NtMLP423 Gene in Drought and Cold Stress. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Transgenic creeping bentgrass plants expressing a Picea wilsonii dehydrin gene (PicW) demonstrate improved freezing tolerance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, D.C.; Stettler, M.; Mettler, T.; Vaughan, C.K.; Li, J.; Francisco, P.; Gil, D.; Reinhold, H.; Eicke, S.; Messerli, G. Beta-amylase4, a noncatalytic protein required for starch breakdown, acts upstream of three active β-amylases in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1040–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Yue, C.; Tang, H.; Qian, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Cloning of β-amylase gene (CsBAM3) and its expression model response to cold stress in tea plant. Acta Agron. Sin. 2017, 43, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, M.; Santelia, D. Starch as a determinant of plant fitness under abiotic stress. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gong, X.; Gao, J.; Dong, H.; Zhang, S.; Tao, S.; Huang, X. Transcriptomic and evolutionary analyses of white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) β-amylase genes reveals their importance for cold and drought stress responses. Gene 2019, 689, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hu, C.; Qi, X.; Chen, J.; Zhong, Y.; Muhammad, A.; Lin, M.; Fang, J. The AaCBF4-AaBAM3.1 module enhances freezing tolerance of kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta). Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; Nie, Y. Fe(II) and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases for natural product synthesis: Molecular insights into reaction diversity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panat, N.A.; Maurya, D.K.; Ghaskadbi, S.S.; Sandur, S.K. Troxerutin, a plant flavonoid, protects cells against oxidative stress-induced cell death through radical scavenging mechanism. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Peng, T.; Xue, S. Mechanisms of plant saline-alkaline tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 281, 153916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Ayugase, J. Effect of low temperature on flavonoids, oxygen radical absorbance capacity values and major components of winter sweet spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2095–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, L.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Xu, J. Overexpression of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Gene, ZeF3H, from Zelkova schneideriana Enhanced Plant Tolerance to Chilling Stress. Forests 2025, 16, 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121838

Gong L, Hu J, Liu X, Lu X, Xu J. Overexpression of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Gene, ZeF3H, from Zelkova schneideriana Enhanced Plant Tolerance to Chilling Stress. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121838

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Longfeng, Jiayu Hu, Xiao Liu, Xiaoxiong Lu, and Jichen Xu. 2025. "Overexpression of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Gene, ZeF3H, from Zelkova schneideriana Enhanced Plant Tolerance to Chilling Stress" Forests 16, no. 12: 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121838

APA StyleGong, L., Hu, J., Liu, X., Lu, X., & Xu, J. (2025). Overexpression of Flavonoid Biosynthesis Gene, ZeF3H, from Zelkova schneideriana Enhanced Plant Tolerance to Chilling Stress. Forests, 16(12), 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121838