Abstract

Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc.) is a dicotyledonous plant from the Rosaceae family that originated in China. Functional genomic studies in Japanese apricot are essential to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying key agronomic traits and to accelerate crop improvement. However, the lack of an efficient genetic transformation system has hindered gene function analysis and impeded molecular breeding efforts. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation has emerged as a robust tool for functional gene validation and studying root-specific processes across diverse plant species, due to its simple protocol and rapid turnaround time. Notably, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation remains notoriously recalcitrant in Rosaceae species, particularly in Japanese apricot. Through screening of ten Japanese apricot varieties, we identified ‘Muguamei’ (MGM) as the optimal cultivar for tissue culture. Using its genotype, we established an Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation system for Japanese apricot via an in vitro approach. The binary vector incorporated the RUBY reporter for visual selection and eYGFPuv for fluorescent validation of transformation events. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of PmPDS in ‘Muguamei’ calli generated albino phenotypes, confirming successful genome editing. Through optimization of antibiotics, the study achieved an 80% explant survival rate using Woody Plant Medium (WPM) supplemented with 6-BA (0.5 mg/L) and TDZ (0.05 mg/L). For in vitro micropropagation, we found that ‘Muguamei’ exhibited optimal shoot growth in the presence of 6-BA (0.06 mg/L) and TDZ (0.1 mg/L), and up to 8 bud proliferation lines could be reached under 4.0 mg/L 6-BA. During the rooting of micro shoots, ½MS medium performed better and reached the optimum root length (35.70 ± 4.56 mm) and number (6.00 ± 1.00) under IAA (0.5 mg/L) and IBA (0.4 mg/L). Leaf explants were cultured on WPM supplemented with TDZ (4.0 mg/L) and NAA (0.2 mg/L). 50 mg/L kanamycin concentrations were the suitable screening concentration.

1. Introduction

Japanese apricot is a traditional fruit tree native to Asia. China has cultivated Japanese apricot for over 3000 years, accumulating diverse germplasm resources. It is a small deciduous tree that typically grows to a height of 4–10 m. It blooms from December to March, with fruit ripening between April and July. Extracts derived from Japanese apricot have long been utilised in traditional Chinese medicine due to their wide range of nutritional and functional properties. With their remarkable storage stability and versatility for value-added processing, Japanese apricot fruits represent an economically important agricultural commodity [1].

Currently, the relevant literature on Japanese apricot primarily focuses on its extracts [2], organic acids [3], and cold resistance-related traits [4], with almost no reports on tissue culture and genetic transformation. However, the lack of effective genetic transformation systems has hindered further research. In vitro regeneration of stone fruit cultivars remains particularly challenging, with typically low success rates and extended regeneration timelines. In contrast, the genetic transformation system of callus offers a faster, more efficient, and scalable alternative for plant functional genomics studies, including hormone research [5] and abiotic stress [6]. A genetic transformation system based on callus has been well established in various stone fruits, such as apple [7], pear [8], and peach [9]. In the case of Japanese apricot, only a few studies are currently available.

The genetic modification via gene knockout or overexpression is an effective strategy for studying gene function, and stable genetic transformation is a powerful tool for these analyses. During the genetic transformation process, efficient reporter genes facilitate the detection of plant status and selection of transgenic material [10]. Moreover, reporter genes enable the screening of positive transformation lines due to their distinctive visual effects [11]. However, conventional reporters such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) and β-glucuronidase (GUS) have limitations. Considering that the new reporting system should be non-invasive, continuous, and cost-effective, we first established two overexpression systems using RUBY (a betalain biosynthesis system) and eYGFPuv (an enhanced yellow GFP-like protein derived from Chiridius poppei) as reporter genes in Japanese apricot. In contrast to conventional reporter systems, the RUBY reporter offers distinct advantages by catalyzing the conversion of tyrosine into vividly pigmented betalains, which produce striking red coloration readily discernible to the naked eye without requiring specialized instrumentation or chemical substrates [12]. Similarly, the eYGFPuv reporter has been extensively optimized to exhibit maximal fluorescence intensity, enabling visual detection under UV illumination without the necessity of fluorescence microscopy [13].

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-4ssociated nuclease 9 (Cas9) system has been widely used in various model plants to improve desirable agronomic characteristics in crop plants, serving as a powerful genome-editing tool. Firstly, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) identifies and guides the Cas9 nuclease to cleave the appropriate target sequence. Following the formation of the sgRNA-Cas9-DNA ternary complex, the Cas9 endonuclease catalysis the formation of precise double-strand breaks (DSBs) at the predetermined genomic locus. In plant cells, these DSBs are primarily repaired through the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which is error-prone and often introduces small nucleotide insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site. This indel formation can result in gene knockout or disruption, allowing for precise and targeted mutagenesis [14]. Inactivation of the PHYTOENE DESATURASE (PDS) gene is often used to validate the CRISPR/Cas9 system. As a key gene in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, it is responsible for green plant coloration. Knocking out the PDS gene blocks carotenoid production, leading to the accumulation of the colorless precursor octahydrolycopene and resulting in an albino phenotype [15].

In this study, we established a comprehensive system for the micropropagation and genetic transformation of Japanese apricot calli. Through the initial cultivation of ten Japanese apricot varieties, we identified specific cultivars well-suited to tissue culture conditions. Subsequently, we conducted refined root induction experiments on the varieties for further research. Orthogonal experiments were conducted to assess induction capabilities under different plant growth regulators (PGRs), including 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), thidiazuron (TDZ), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D). Following the selection of appropriate antibiotic concentrations through sensitivity testing, exogenous RUBY and eYGFPuv [16] were successfully introduced into Japanese apricot callus tissues via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Then, we successfully knocked out the PmPDS through the CRISPR system. Additionally, this approach offers potential for research on in vitro regeneration of Japanese apricot and gene function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Explants Preparation

Plant materials were obtained from the National Germplasm Repository of the Nanjing Agricultural University. For initiation, one-year-old tender shoots from ten Japanese apricot cultivars (‘Longyan’, ‘Esu’, ‘Xinyilve’, ‘Nannongwumei’, ‘Muguamei’, ‘Huanghoumei’, ‘Xiaolve’, ‘Lve’, ‘Hongxuzhusha’, and ‘Touguhong’) were selected as explants. The explants were treated with 50 mL/L detergent (Blue Moon, Lanyueliang (China) Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) for 1 h, rinsed three times with sterile water in a laminar flow hood, immersed in 75% ethanol for 1 min, and soaked in sterile 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min. Subsequently, the explants were rinsed again with sterile water. Side buds were dissected with a 1 cm segment, and the stem segments were placed on the initial medium with different antibacterial agents (I: None Inhibitor; II: 1.5 mL/L Zhipeijin (A commercial fungal inhibitor; MuMuShengWu, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China); III: 50 mg/L ampicillin.) (Woody Plant Medium (WPM): 7 g/L agar + 30 g/L sucrose, 0.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.05 mg/L TDZ, pH = 5.8). The explants were cultured in darkness for 14 days, followed by 16 days of light exposure. Thereafter, the contamination and browning rates were documented.

2.2. Selection of Subculture Medium

In vitro plants cultivated for one month were selected, and under sterile conditions in a laminar flow cabinet, apical shoot tips approximately 1 cm in length were excised. Expanded leaves were carefully removed, and the shoot tips were subsequently inoculated onto culture media supplemented with plant growth regulators (PGRs) (Table S1). The remaining components of each combination were the same (7 g/L agar and 30 g/L sucrose, pH 5.8). Each culture medium was placed with five in vitro plants, with three replicates per treatment. The cultures were maintained at 23 °C under a photoperiod of 16 h of light provided by cool-white, fluorescent lamps (100–140 µmol m−2 s−1) per day. After 30 days of cultivation, the height, number of leaves, and number of clusters per tissue-cultured seedling were recorded. The cluster number was determined based on the number of lateral bud germinations. Among the ten tested Japanese apricot cultivars, only three were successfully transferred from culture dishes to tissue culture bottles. However, only the ‘Muguamei’ (MGM) cultivar consistently survived after the second subculture. Therefore, ‘MGM’ was selected as the representative cultivar for further experiments and was subjected to treatments with 6-BA (0.02, 0.06, 0.12, 0.2, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/L) and TDZ (0.1 mg/L).

2.3. Rooting and Acclimatization of In Vitro Plants

Axillary buds obtained from subcultured plantlets were transferred onto rooting culture medium with different concentrations of IBA (0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.0 mg/L). To determine the optimal rooting medium, three basal culture media were used: half-strength Murashige and Skoog (½MS), full-strength MS, and WPM. Each tissue culture bottle was inoculated with three materials, with five replicates per material. After 30 days of rooting culture, in vitro plantlets exhibiting vigorous growth were selected for acclimatization. The tissue culture bottles were opened, and the plantlets were exposed for 24 h under controlled conditions at 23 °C with a 16 h photoperiod and 60% relative humidity. This was followed by an additional 24 h of open cultivation at room temperature under natural light conditions. A plantlet was considered successfully rooted if it had produced more than two roots and the longest root length exceeded 10 mm. A potting mixture consisting of perlite and soil in a 1:3 (v:v) ratio was prepared, and the plantlets were carefully removed, washed to eliminate residual medium, and transplanted into the pots. The pots were placed in a greenhouse and maintained under standard watering and fertilization regimes to support acclimatization and continued growth.

2.4. Callus Induction and Multiplication

To establish an appropriate suitable callus induction medium (CIM), the leaves of tissue-cultured plantlets obtained from subculture were transversely cut at the midpoint and placed flat onto culture media supplemented with varying concentrations of auxins (NAA, IBA, and 2,4-D: 0.2 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, and 1.0 mg/L) and cytokinins (6-BA, TDZ: 0.5 mg/L, 2.0 mg/L, and 4.0 mg/L). The explants were subjected to a 14-day dark treatment at 25 °C, followed by transfer to culture conditions at 25 °C under a 16 h photoperiod. Five replicates per treatment were used, each plate with twenty-five leaf segments. After 30 days, the callus tissue was evaluated, and its size, colour, and morphological characteristics were documented (Table S2).

2.5. Screening for Optimal Kanamycin Concentration for Genetic Transformation

To determine the appropriate concentration of kanamycin, callus tissues were cultured on media supplemented with kanamycin (Kan) at concentrations of 5, 25, 50, 100, and 150 mg/L. The growth status of the callus tissues was recorded after 30 days. Concentrations that significantly inhibited callus growth without completely suppressing callus activity were selected for subsequent genetic transformation experiments.

2.6. Reporter Gene Vector Construction

The binary vector pCAMBIA1301 was used as the backbone for all constructs. This plasmid (~12.5 kb) features a hygromycin phosphotransferase (hptII) gene, driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, for the selection of transformed plant tissues, and a kanamycin resistance gene for selection in E. coli. The vector was engineered to 2 × 35S::eYGFPuv, containing the eYGFPuv reporter gene driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, and was used in this study. The construction of RUBY based on the [17]. The plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by the chemical transformation method. Transformed colonies were selected on solid Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin and 50 mg/L rifampicin. Verified colonies were preserved as glycerol stocks at −80 °C, and the presence of eYGFPuv and RUBY was confirmed by PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.7. CRISPR/Cas9 Vector Construction

The CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector was developed in our laboratory. We used CRISPR-offinder (v1.2) to perform a genome-wide scan for protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites with default parameters. Two PAM sites with high editing efficiency and low off-target activity were selected as single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences [18]. These were incorporated into the CRISPR/Cas9 vector via homologous re-combination, driven by AtU6-29 and AtU9-26 promoters, respectively.

2.8. Genetic Transformation

The preserved Agrobacterium glycerol stock was streaked onto solid LB agar plates supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L rifampicin for activation. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for three days. A single colony was then inoculated into 50 mL Agrobacterium liquid medium cultured overnight at 28 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the bacterial culture reached 0.6–0.8, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000× g for 10 min at 24 °C. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 45 mL of bacterial suspension medium. The resuspended culture was then incubated at 28 °C with shaking at 220 rpm for 1 h to activate the virulence of Agrobacterium before subsequent transformation procedures. Leaves of the ‘Muguamei’ (MGM) cultivar were then cultured in the Agrobacterium suspension for 15 min. After infiltration, the leaves were cultured on co-cultivation medium supplemented with 100 μmol/L AS in darkness at 25 °C for 2 days. Subsequently, the callus tissues were transferred to delay medium containing 200 mg/L Timentin for 7 days, followed by selection on primary selection medium supplemented with 200 mg/L Timentin and 50 mg/L kanamycin to isolate transgenic callus tissue. A total of 25 leaf ex-plants were plated per Petri dish, with each treatment comprising 16 replicate plates. After one month, calli were collected and subcultured every 15 days for genetic and phenotypic analyses. The relevant culture media involved are:

(1) Agrobacterium Solid Medium: LB agar + 1 mL/L Kan (50 mg/mL) + 1 mL/L rifampicin (50 mg/mL)

(2) Agrobacterium Liquid Medium: LB broth + 1 mL/L Kan (50 mg/mL) + 1 mL/L rifampicin (50 mg/mL)

(3) Bacterial Suspension Medium: WPM + 30 g/L sug + 0.5 mg/L 6-BA + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D + 100 μmol/L AS

(4) Co-cultivation Medium: WPM + 30 g/L sug+ 7 g/L agr + 0.5 mg/L 6-BA + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D + 100 μmol/L AS

(5) Delay Medium: WPM + 30 g/L sug+ 7 g/L agr + 0.5 mg/L 6-BA + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D + 200 mg/L Timentin

(6) Primary Selection Medium: WPM + 30 g/L sug+ 7 g/L agr + 4.0 mg/L TDZ + 0.2 mg/L NAA + 200 mg/L Timentin + 50 mg/L Kan

2.9. Callus Tissue eYGFPuv and RUBY Observation

Transgenic calli expressing RUBY exhibited red coloration, observable under ambient conditions, whereas those expressing eYGFPuv emitted green fluorescence under 365 nm ultraviolet (UV) light. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using specific primers was conducted to confirm the presence of transgenes in the transformed cells. Amplification products were analyzed on a 1.0% (w/v) agarose gel and subjected to imaging for further observation.

2.10. RT-PCR Identification of Resistant Callus

To verify the expression of RUBY and eYGFPuv in transgenic callus, non-transgenic ‘Muguamei’ (MGM) callus was used as the wild-type (WT) control. Three replicates of transgenic RUBY calli (RUBY1, RUBY2, RUBY3) and three replicates of transgenic eYGFPuv calli (eYGFPuv1, eYGFPuv2, eYGFPuv3) were analyzed. Total RNA was extracted using the Polysaccharide Polyphenol Plant RNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using TaKaRa’s M-MLV (RNase H-) reverse transcriptase, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 0.4 μL of each primer, 1× ROX reference dye, 10 μL of 2 × SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa), and 100 ng of cDNA template. The RT-qPCR program consisted of one cycle at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 34 s at 60 °C. Each sample was subjected to three biological and three technical replicates, with data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3) for Student’s t-test analysis. Gene expression was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method, the internal control genes were from a previous study [19].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

The data from Section 3.1 were analyzed using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction. Other datasets were analyzed using a t-test (p < 0.05) in SPSS statistical software (version 26.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for hypothesis testing. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.0, San Diego, CA, USA) and images were processed using Adobe Photoshop (version 21.0.0.37, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Bacteriostatic Agents on Ten Japanese Apricot Varieties in the Primary Experiment

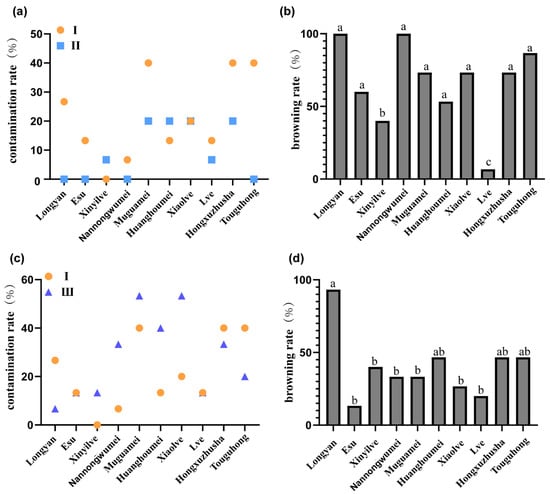

Ten Japanese apricot varieties were evaluated for their response to three antibacterial treatments: no antibacterial agent I, Zhipeijin II (a commercial fungal inhibitor mainly composed of matrine, rotenone, azadirachtin, pyrethrin, nicotine, kudzu saponin, eucalyptol and star anise oil), and ampicillin III (AMP). Following the application of fungal antibiotics, ‘Lve’ demonstrated a significantly higher germination rate compared to other varieties. Compared to the blank control group, the contamination rates of eight tested varieties decreased, except for ‘Xinyilve’, ‘Huanghoumei’, and ‘Xiaolve’. Specifically, contamination rates of ‘Longyan’, ‘Muguamei’, ‘Hongxuzhusha’, and ‘Touguhong’ were reduced by 26.67%, 20.00%, 20.00%, and 40.00%, respectively (Figure 1a). However, the browning rates of these four varieties remained elevated (>50%) (Figure 1b). Further analysis revealed that the bacterial antibiotic AMP failed to significantly reduce contamination rates in most plants, with only ‘Longyan’, ‘Touguhong’, and ‘Hongxuzhusha’ showing reductions (Figure 1c). Other varieties exhibited no improvement or even increased contamination rates, though browning rates remained below 50% (except ‘Longyan’) (Figure 1d). Collectively, Zhipeijing can effectively control primary culture contamination (average inhibition rate: 12%), but its induction of oxidative stress exacerbated tissue browning, resulting in a decoupling between reduced contamination and improved survival rates. While bacterial antibiotics minimally affect plant morphology, they still negatively impact survival rates.

Figure 1.

Survival rate of first-generation plants under different antibiotic treatments. (a) Contamination rate of different Japanese apricot varieties under Inhibitors I and II. (b) Browning rate of different Japanese apricot varieties under Inhibitor II. (c) Germination rate of different Japanese apricot varieties under Inhibitors I and III. (d) Browning rate of different Japanese apricot varieties under Inhibitor III. Inhibitor I: no inhibitor; Inhibitor II: 1.5 mL/L Zhipeijin (a commercial antifungal agent); Inhibitor III: 50 mg/L ampicillin. Values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), according to the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction.

3.2. Effects of Phytohormones on Tissue Culture of Japanese Apricot In Vitro Plants

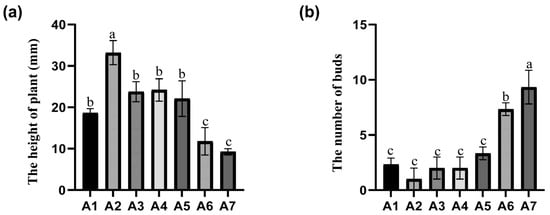

Selecting one-month-old ‘MGM’ in vitro plants as the research subject, the study investigated the effect of PGRs on ‘MGM’ in vitro plant proliferation under different concentration combinations. During the initial growth stage, the A1–A7 series treatments showed a trend of normal distribution in plant height with a gradual increase in 6-BA concentration (Figure 2a). With the 0.06 mg/L low concentration treatment group, the in vitro plant height reached the maximum value (33.17 ± 2.90 mm), which was significantly better than other treatment groups. When the 6-BA concentration exceeded A6 (2.0 mg/L), the in vitro plants height inhibitory effect intensified. In contrast, lateral shoot induction was observed: below the threshold concentration of 1.0 mg/L, the proliferation coefficient of lateral shoots was only 1.0–3.3; while when the concentration was elevated to 2.0 mg/L, the number of lateral shoots showed an exponential increase (7.33 ± 0.57), which was 733% higher than that of the lowest concentration group (Figure 2b). This effect revealed a dual mechanism of action of 6-BA in regulating the nutrient growth and organogenesis of ‘MGM’ subculture. A2, which contained 30 g/L sucrose, 7 g/L agar, 1 g/L polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), 0.06 mg/L 6-BA + 0.1 mg/L TDZ in WPM, was suitable for the induction of healthy in vitro plants. The experiment demonstrated that varying concentrations of the tested factors had a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05) on the subsequent growth and development of in vitro plants, indicating that concentration levels of 6-BA play a critical role in optimising in vitro culture conditions.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic response of ‘MGM’ to varying 6-BA concentrations after 40 days of subculture treatment (a) Plant height of ‘MGM’ after 40 days of hormone treatment. (b) Number of buds in ‘MGM’ after 40 days of hormone treatment. Each treatment consisted of a constant TDZ concentration (0.10 mg/L) combined with increasing levels of 6-BA: A1 (0.02 mg/L), A2 (0.06 mg/L), A3 (0.12 mg/L), A4 (0.25 mg/L), A5 (1.00 mg/L), A6 (2.00 mg/L), and A7 (4.00 mg/L). Values followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s test.

3.3. In Vitro Shoot Proliferation, Rooting, and Ex Vitro Acclimatization

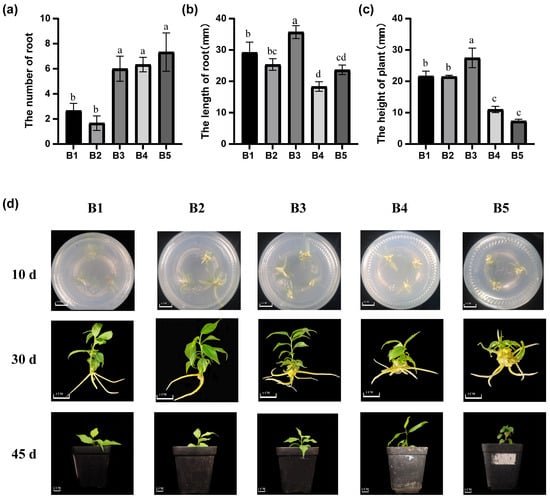

Using ‘MGM’ tissue cultures as experimental subjects, the optimal rooting medium was determined by varying culture media and plant hormone concentrations. Because of the lack of regenerative buds, buds from successive cultures were used as experimental materials. Based on previous studies, we used a combination of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and IBA. Among WPM, MS, and ½ MS media, growth was best in ½ MS media, with an average root length of 27.46 ± 3.10 mm, average plant height of 35.70 ± 4.56 mm, and average number of roots of 6.00 ±1.00, all significantly higher than other treatments (Table 1). By the 30th day, as IBA concentration increased, the number of roots per plant continued to increase and spread. When the concentration of IBA exceeded 0.4 mg/L, the induction of root number by IBA was optimized (Figure 3a). Comparative analyses with other treatment groups showed that the B2 (0.4 mg/L) IBA treatment exhibited a specific advantage in root length index (35.70 ± 4.56 mm), which was significantly higher than the adjacent concentration gradients (0.2 mg/L: 25.36 ± 1.86 mm; 0.6 mg/L: 18.3 ± 1.52 mm) (Figure 3b), the above-ground growth of treatments B1–B3 was better than that of treatments B4–B5 (Figure 3c). On the 10th day, only a few root hairs were observed in the B1 treatment, whereas treatments B2–B5 showed significant root development. When the plants were transplanted, the B3 treatment showed greater number of leaves and larger leaf area. The roots in treatments B2 and B3 were superior in length and thickness compared to those in treatments B4–B5 (Figure 3d). In summary, the most effective culture medium was ½ MS medium containing 30 g/L sucrose, 7 g/L agar, 1 g/L PVP, 0.5 mg/L IAA + 0.4 mg/L IBA.

Table 1.

The influence of different medium on rooting experiment of Japanese apricots.

Figure 3.

Rooting response of in vitro plants to different hormone treatments. (a) Number of roots in ‘MGM’ after 30 days of hormone treatment. (b) Root length in ‘MGM’ after 30 days of hormone treatment. (c) Plant height in ‘MGM’ after 30 days of hormone treatment. (d) Rooting response to IAA and IBA after 10, 30, and 45 days. Treatments B1–B5 consisted of a constant IAA concentration (0.5 mg/L) combined with increasing concentrations of IBA: B1 (0.00 mg/L), B2 (0.20 mg/L), B3 (0.40 mg/L), B4 (0.80 mg/L), and B5 (1.00 mg/L). Values followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s test.

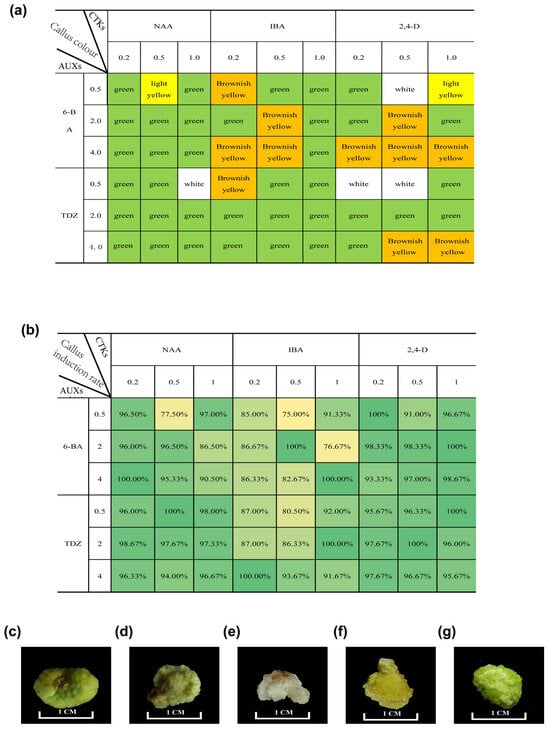

3.4. Effects of Different Concentrations and Types of Phytohormones on Plant Callus

For callus tissue induction, ‘MGM’ tissue culture leaves were selected as explant materials to study the effect of phytohormones on callus proliferation and adventitious bud regeneration at different concentrations. In the process of callus induction by cytokinin, the callus induced by TDZ was greener, and the induction rate was higher than that 6-BA (Figure 4a,b). Continuing with the treatments involving 6-BA and IBA, after 14 days of dark incubation, lower concentrations of 6-BA showed better induction effects but were generally inferior to other groups (Table S3). In treatments with TDZ and IBA, the callus induction rate was moderate, primarily consisting of normal callus with occasional dense callus. Overall, callus size was moderate (Table S4). In the combination of 6-BA and NAA treatments, the callus induction rate was moderate, mainly consisting of dense callus, which aged slowly and had a smaller volume (Table S5). Higher concentrations of 6-BA resulted in poorer induction, with smaller callus tissue formation. Most callus tissues induced by TDZ appeared dark green, but when the ratio of TDZ to 2,4-D was low, the callus tissues tended to be white and loose (Table S6). Conversely, when the TDZ concentration was high, the callus tissue tended to turn green. Similar characteristics were observed when 6-BA was combined with 2,4-D.

Figure 4.

Callus status under different hormone treatments. (a) Callus colour after 30 days of culture under different hormone treatments. (b) Induction rate under different hormone treatments. (c) Callus morphology at varying ratios of 2,4-D to cytokinin (4.0 mg/L TDZ + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D). (d) Callus morphology at varying ratios of 2.0 mg/L TDZ + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D. (e) Callus morphology at varying ratios of 0.5 mg/L TDZ + 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D. (f) Callus morphology at varying ratios of 0.5 mg/L TDZ + 0.5 mg/L 2,4-D. (g) Callus morphology at varying ratios of 0.5 mg/L TDZ + 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D.

In the process of callus induction by auxin, the callus induced by NAA was greener than the others, but the 2,4-D performed better in the induction rate of callus (Figure 4a,b). In treatments involving 6-BA and 2,4-D, after 14 days of dark incubation, milky-white callus tissue appeared on the petiole, albeit small (Table S7). Most leaves could induce callus with higher concentrations of 2,4-D, significantly affecting callus tissue colour and density, turning it white and loose. The same effect was observed in treatments with TDZ and 2,4-D (Figure 4c–g). For treatments with TDZ and NAA, after 14 days of dark incubation, most leaves had visible chunky milky-white callus tissue, with no apparent differences between low and high concentrations initially (Table S8).

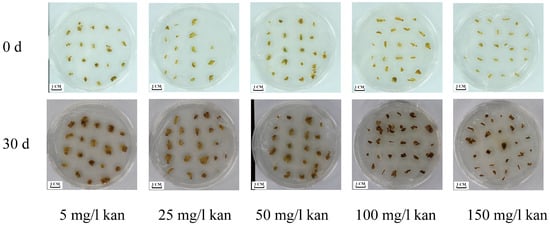

3.5. Effect of Varying Kanamycin Concentrations on Callus Proliferation

Our preliminary results showed that the optimal CIM for Japanese apricot was WPM + 4.0 mg/L TDZ + 0.2 mg/L NAA. To confirm the suitable concentrations of kanamycin, the calli of ‘MGM’ were cultured on CIM with different concentrations of kanamycin (Table 2). Callus growth responded negatively to kanamycin supplementation. At 25 mg/L, growth inhibition was marginal (10.2 ± 2.34% reduction), whereas concentrations ≥ 100 mg/L caused severe browning and 82.3 ± 4.62% biomass loss (Figure 5). These results confirm that 50 mg/L kanamycin is the critical threshold for effective selection.

Table 2.

The influence of different concentrations of kanamycin on the propagation of callus of Japanese apricot.

Figure 5.

Effects of different concentrations of kanamycin on the proliferation of ‘MGM’ callus. The callus was grown for 25 days on a WPM proliferation medium containing 5, 25, 50, 100, and 150 mg/L kanamycin.

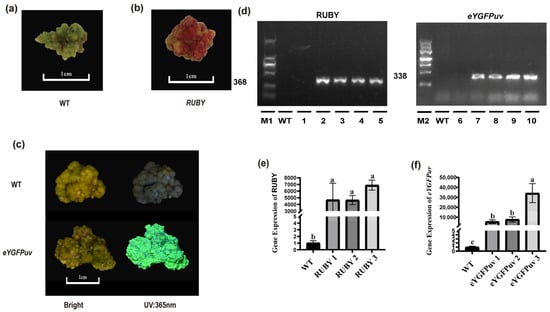

3.6. Genetic Transformation of Japanese Apricot Callus with RUBY and eYGFPuv Reporters

To determine whether ‘MGM’ is a suitable transgenic material, we conducted genetic transformation experiments using RUBY and eYGFPuv. In the RUBY transformation experiments, the 17 stable calli expressing the gene were obtained from the 439 leaves (3.9%) (Figure 6a,b). Genomic PCR analysis confirmed the insertion of the target fragment in the resistant callus tissue, whereas the wild type showed no detection of this insertion (Figure 6d). In eYGFPuv fluorescence detection, the 32 calli from the 532 leaves exhibited fluorescence signals (6%) (Figure 6c), and genomic PCR analysis confirmed the insertion of the eYGFPuv transgene into the resistant callus (Figure 6d). RT-PCR analysis indicated that RUBY and eYGFPuv expression was significantly higher in the transgenic callus than in the wild type (Figure 6e,f). Thus, ‘MGM’ can serve as a stable genetic transformation material in Japanese apricots. The specific primer sequence is shown in Table S9.

Figure 6.

Identification of putative transformants. (a) Wild-type (WT) callus sample. (b) Transgenic callus overexpressing RUBY. (c) Transgenic callus overexpressing eYGFPuv and WT under bright light and 365 nm UV. (d) PCR amplification of eYGFPuv and RUBY gene fragments. The amplified fragment length was 368 bp for RUBY and 338 bp for eYGFPuv. M1 and M2 are markers of 2000 and 4500 bp, respectively. Lane 1: water control; Lane 2: RUBY plasmid; Lanes 3–5: transgenic RUBY lines; Lane 6: water control; Lane 7: eYGFPuv plasmid; Lanes 8–10: transgenic eYGFPuv lines. (e) RT-PCR confirmation of RUBY-overexpressing callus. (f) RT-PCR confirmation of eYGFPuv-overexpressing callus. Values followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s test.

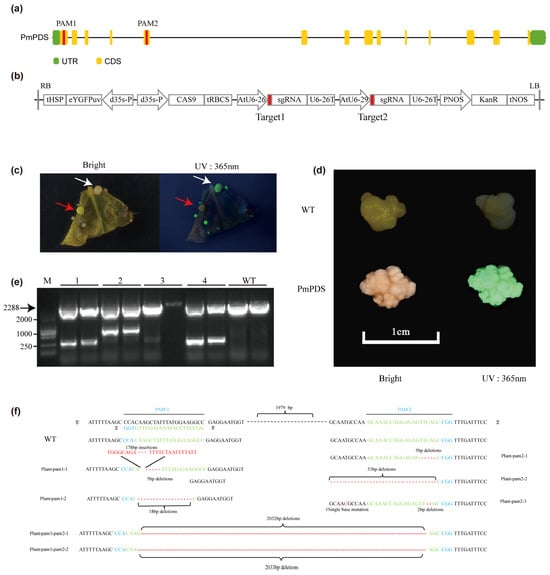

3.7. Targeted Inactivation of the PmPDS Gene Using CRISPR/Cas9 System

We designed two specific sgRNAs based on the genome sequence for targeting the first and the fifth exon of the PmPDS gene (Figure 7a). The selected sgRNA sequences (3′-CCACAAGCTATTTATGGAAGGCC-5′) and (5′-GCAAACCAGGAGAGTTCAGCCGG-3′) showed high specificity and no off-target sites (Table S10). By assembling PAM sites and sgRNA, it was confirmed by sequencing and introduced into Agrobacterium cells for transformation (Figure 7b). Among 873 initial explants, 52 exhibited fluorescence, indicating putative transformation. Of these, 34 fluorescent calli developed an albino phenotype. Sanger sequencing confirmed that 65.38% (34/52) of the fluorescent calli carried successful edits in the target gene. Compared to green callus (the red arrow), we observed the appearance of an albino phenotype corresponding to a fluorescent response at 365 nm UV (The white arrow) (Figure 7c). In addition, many young calli showed fluorescent responses, demonstrating the feasibility of eYGFPuv as an early detection of gene editing, and we also observed the emergence of chimeras. The transgenic phenotype remained consistently observable through multiple subculture cycles, demonstrating stable genetic transformation (Figure 7d). During the experiment, the transgenic trait was maintained through multiple subcultures (>5) of the callus. PCR amplification of the region spanning the two sgRNA target sites showed that it was present in four albino clauses but not in wild-type plants (Figure 7e). To confirm the inactivation of PmPDS gene, we amplified the PmPDS gene region, cloned it into blunt vector, and conducted sequencing analysis (Figure 7f). Sequencing results indicated that single-nucleotide or double-nucleotide insertions and deletions as well as large fragment insertions and deletions occurred in the expected regions targeted by the designed sgRNAs. These introduced mutations caused frameshifts in the reading frame, resulting in premature termination codons and subsequent inactivation of the PDS enzyme. The specific primer sequence is shown in Table S9.

Figure 7.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of the PmPDS gene in ‘MGM’. (a) Schematic representation of the PmPDS gene showing the sequence targeted by sgRNA-PmPDS. (b) Schematic representation of the CRISPR/Cas9 construct. (c) Transgenic callus under natural light and 365 nm UV at the early stage of genetic modification. The red arrow indicates green fluorescence where the target was not knocked out, while the white arrow indicates knockout events, with the phenotype appearing slightly white. (d) WT and transgenic callus under natural light and 365 nm UV after multiple generations of proliferation. (e) PCR amplification of PmPDS containing PAM sites. Fragments of >2000 bp indicate the distance between the two PAM sites, while shorter bands suggest random cleavage between PAM sites by Cas9. Precise sequence length requires confirmation by sequencing. M: 2000 bp marker. Lanes 1–4: PmPDS knockout callus; lane 3 showed no band, likely a false positive. (f) DNA sequences of mutated PmPDS at target 1 and target 2. The frequency of each mutation type was estimated by random sequencing of PCR products cloned from the genome to assess genome-editing efficiency.

4. Discussion

In recent years, with continuous improvements in high-throughput genome sequencing technologies, an increasing number of fruit tree genomes have been published, providing references for improving fruit tree crop traits. Additionally, the functional identification of genes underlying essential horticultural traits, such as colour, shape, and texture, has significantly accelerated the advancement of genetic engineering and molecular breeding strategies in fruit tree species [20]. Japanese apricot has undergone extensive genomic analysis, resulting in the identification of numerous regulatory genes associated with important agronomic traits [21]. Callus tissue can be used for plant regeneration and as a bioreactor for possibly producing bioactive compounds from plants [22]. Establishing a callus tissue genetic transformation system will lay the foundation for the functional analysis of genes related to the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds [23].

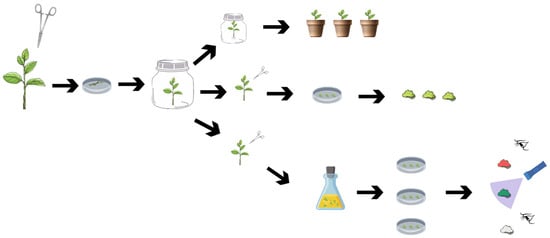

In this study, we optimized the entire process from the initial in vitro culture to the successful development of viable in vitro plants and the establishment of an efficient genetic transformation system. This comprehensive workflow provides a valuable platform for future molecular and genetic research in Japanese apricot. The specific process is as follows (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic flowchart of tissue culture propagation in Japanese apricot.

External contamination by fungi, bacteria, or yeast is a severe issue in commercial micropropagation [24]. In our study, a comparative analysis revealed cultivar-dependent patterns of antibiotic susceptibility in Japanese apricot. The ‘Lve’ genotype manifested 33.34% greater plant survival rates under 1.5 mL/L “Zhipeijin” (A commercial fungal inhibitor), contrasting sharply with ‘Touguhong’, which showed 13.37% reduction in vitro plants survival efficiency (Figure 1a), suggesting genotype-specific stress adaptation mechanisms. Micropropagation experiments with seedless grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv ‘Sultanine’ demonstrated that antibiotic supplementation (200 mg/L cefotaxime + 100 mg/L oxytetracycline) significantly suppressed microbial contamination during shoot proliferation [25]. It is noteworthy that most varieties showed increased plant browning under antibiotic treatment, and antioxidant capacity may be responsible for the differences in response to antibiotics among plants. Further study of this phenomenon may help inform the use of antibiotics in primary experiments.

Phytohormones are the primary influencing factors in subcultures. Both 6-BA and TDZ are cytokinins that primarily induce cell division, initiate bud formation, and promote bud growth [26]. 6-BA is the most suitable for meristematic tissue culture in other woody species, such as Betula albosinensis [27] and Picea pungens [28]. In our study, we found that a low concentration of 6-BA better promotes the growth of in vitro microshoots, and a high concentration of 6-BA significantly improves the shoot proliferation coefficient. This response pattern mirrors previous findings in apple (Malus × domestica) tissue culture systems [29]. Unlike other species, it is difficult to identify a medium formulation that allows in vitro microshoots to achieve both robust growth and a high proliferation coefficient.

Successful rooting and transplantation of in vitro plants are essential criteria for measuring the success of micropropagation systems. We found that 1/2 MS medium is more suitable for rooting culture than WPM. Rooting experiments in Lophopetalum wightianum Arn (Raktan) demonstrated superior root development in 1/4-strength MS medium compared to 1/2-strength [30], potentially attributable to reduced osmotic pressure enhancing water uptake capacity and subsequent root growth promotion [31]. The medium and auxin concentrations are widely considered the main limiting factors in rooting experiments. Among these, IBA, a suitable rooting phytohormone, has been commonly used in plants such as agaves [32].

During the induction of callus tissue, the callus status was different with different phytohormones. Calli induced by other plants can also show significant differences. We observed that 2,4-D had a positive effect on the induction of white sparse healing in experiments on the induction of healing tissues in leaves, and that high concentrations of 2,4-D delayed the accumulation of green colour in healing tissues in the light. In contrast, TDZ promoted the accumulation of green colour. Compact and green calli have been successfully used in Prunus persica to study RNAi Construct against the PPV Virus [9]. PbMDH3 was activated by PbWRKY26 to positively regulate the accumulation of malate in pear fruit, which was verified by the white loose callus in pears [8]. Genetic transformation of white clover (Trifolium repens) is initiated by white loose callus [33]. The establishment and validation of a callus tissue transformation system for German chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) was based on a green loose callus [34]. Based on the above understanding of the role of hormones, we established a suitable medium formulation and successfully obtained many positive healing tissues with normal growth and progeny in transgenic experiments. Therefore, different callus types should be chosen based on the specific experiment and the physiological needs of the plant. The changes in callus under different plant hormones in this experiment can be used as a reference for future studies.

Genetic engineering facilitates gene function studies and enables targeted breeding [35]. Genotypes used to play a significant role in plant transformation [36]. Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation is a highly efficient and cost-effective gene-delivery system widely used in plant genetic engineering. Most studies utilize immature seeds or cotyledons as starting materials. However, for clonally propagated crops, regeneration from adult tissues is recommended to maintain desired clonal characteristics, though this approach remains challenging. In a study on peach rootstock GF 677, a genetic transformation efficiency of only 0.3% was achieved via callus transformation [37]. Similarly, somatic embryogenesis-based transformation using immature cotyledons of peach reached merely 0.6% [38]. In contrast, the transformation efficiency for ZJB callus was approximately 18% [16]. These results highlight the significant variation in transformation efficiency across different varieties, albeit generally remaining at low levels. We successfully obtained positive callus tissues overexpressing RUBY and eYGFPuv in ‘MGM’ and observed distinct phenotypes with gene-editing efficiencies of 3.9% and 6.0%. The current ‘MGM’ callus tissue transformation system shows promise, similar to systems used in other plants such as exploring the gene function of MdERF3 by apple ‘Orin’ callus [6], using the Arabidopsis T87 cell line for abiotic stress and hormone treatment [5], but further research is needed to achieve regeneration and fruiting.

CRISPR-Cas9 has become an essential tool for genetic research, though its efficacy varies significantly across species. In fruit crops, most studies have focused on citrus [39], Vitis [40], Castanea [41] and Malus [42] for introducing biotic/abiotic stress resistance, while genetic transformation in Prunus species remains challenging. The main challenges we encountered in this part of the study were as follows: (1) the absence of transgenic plantlets, (2) the lack of intra-species comparative analysis across multiple cultivars, (3) the omission of functional gene overexpression, and (4) the relatively low editing efficiency. observed our study still establishes a feasible transformation protocol for Prunus species.

To validate our CRISPR system, we knocked out the PmPDS gene and achieved 65.38% editing efficiency in Japanese apricot, higher than the 31.8% reported in apple [43] and 23.8% in highbush blueberry [44]. The observed outcome may be attributed to our use of multiple sgRNAs, a strategy which has been previously shown to enhance editing efficiency [45]. While sgRNA length—such as the 20-nt variant shown to be optimal in poplar (Populus alba × Populus tremula var. glandulosa) [45]—is a key factor for improving editing efficiency and a direction for our future work, the primary bottleneck lies in plant regeneration. This is exemplified by Castanea sativa Mill, where a PDS knockout achieved 94% efficiency in embryonic calli but only a 13% shoot regeneration rate [46]. However, this potential is contingent on overcoming the significant challenge of in vitro regeneration, a hurdle that is particularly acute in Prunus species due to their general recalcitrance to regeneration and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, despite the identification of numerous key genes controlling fruit, habit, and disease resistance traits [47].

Notably, CRISPR itself can enhance regeneration. For instance, CRISPRa-mediated activation of SlWRKY29 promotes somatic embryogenesis in tomato [48]. Utilizing various Cas nucleases—such as Cas12a (Cpf1), Cas13, and Cas14 [49]—enables precise genome editing in both mammals and plants. To date, only a limited number of studies have reported the use of Cas12a [16] or CRISPRi [50] in woody plants. These technologies offer promising avenues for creating tree models with specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), thereby facilitating the validation of functional SNPs and clarifying their biological roles. Such approaches hold significant potential for future applications in fruit tree improvement.

In our study, the ‘MGM’ cultivar was identified as the variety amenable to micro-propagation. It exhibited a high multiplication coefficient of 7.33, demonstrated a strong rooting capacity (producing an average of 6 roots per shoot with a mean length of 35.7 mm), and developed robust aerial parts after acclimatization. Furthermore, it achieved a maximum callus induction rate of 100%. This cultivar also proved to be a competent host for genetic transformation, as evidenced by the successful expression of both marker genes and the CRISPR system in its callus tissues. We believe that we can further improve the efficiency of gene editing by optimizing the infiltration conditions and by changing the vector components. Obtaining callus tissue is a critical step for the further development of somatic embryogenesis or plant regeneration and represents a key focus for future research.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the ‘Muguamei’ cultivar is a suitable genotype for tissue culture in Japanese apricot. We successfully established a reliable micropropagation protocol and a callus-based genetic transformation system and provided essential tools for functional genomics research. Furthermore, we developed a CRISPR/Cas9 knockout system, paving the way for advanced molecular breeding and genetic improvement in Japanese apricot.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121812/s1, Table S1: Different treatment in subculture; Table S2: Different hormone concentrations in callus induction; Table S3: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of 6-BA and IBA; Table S4: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of TDZ and IBA; Table S5: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of 6-BA and NAA; Table S6: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of TDZ and 2,4-D; Table S7: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of 6-BA and 2,4-D; Table S8: The performance of MGM under different concentrations of TDZ and NAA; Table S9: The sequence of gene primers was designed; Table S10: The screening of PAM sites.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Y.W., P.Z. and Z.G.; data collection: Y.W. and P.Z.; analysis and interpretation of results: X.L., C.M. and S.G.; draft manuscript preparation: Y.W.; manuscript editing: Z.N., X.H. and F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372670, 32502637), the “JBGS” Project of Seed Industry Revitalization in Jiangsu Province (JBGS [2021] 019), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYZZ2025), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Bailly, C. Anticancer Properties of Prunus mume Extracts (Chinese Plum, Japanese Apricot). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 246, 112215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Du, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Lyu, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, W.; Li, W. Polyphenols from Prunus mume: Extraction, Purification, and Anticancer Activity. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 4380–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccichet, I.; Chiozzotto, R.; Tura, D.; Tagliabue, A.G.; Tartarini, S.; Da Silva Linge, C.; Spinardi, A.; Rossini, L.; Bassi, D.; Cirilli, M. Dissection of Acidity-Related Traits in an Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Germplasm Collection Revealed the Genetic Architecture of Organic Acids Content and Profile. Fruit Res. 2025, 5, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, F.; Ma, C.; Iqbal, S.; Huang, X.; Omondi, O.K.; Ni, Z.; Shi, T.; Tariq, R.; Khan, U.; Gao, Z. Rootstock-Mediated Transcrip-tional Changes Associated with Cold Tolerance in Prunus mume Leaves. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, A.; Kwiatkowska, A.; Jerzmanowski, A.; Prymakowska-Bosak, M. Up-Regulation of Stress-Inducible Genes in Tobacco and Arabidopsis Cells in Response to Abiotic Stresses and ABA Treatment Correlates with Dynamic Changes in Histone H3 and H4 Modifications. Planta 2007, 227, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-P.; Wang, X.-N.; Yao, J.-F.; Ren, Y.-R.; You, C.-X.; Wang, X.-F.; Hao, Y.-J. Apple MdMYC2 Reduces Aluminum Stress Tolerance by Directly Regulating MdERF3 Gene. Plant Soil 2017, 418, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Sun, X.; Yue, P.; Qiao, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, A.; Yuan, H.; Yu, W. The MdAux/IAA2 Transcription Repressor Regulates Cell and Fruit Size in Apple Fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, R.; Wang, A.; Zhai, R.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Xu, L. PbWRKY26 Positively Regulates Malate Accumulation in Pear Fruit by Activating PbMDH3. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 288, 154061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbadini, S.; Ricci, A.; Limera, C.; Baldoni, D.; Capriotti, L.; Mezzetti, B. Factors Affecting the Regeneration, via Organogenesis, and the Selection of Transgenic Calli in the Peach Rootstock Hansen 536 (Prunus persica × Prunus amygdalus) to Express an RNAi Construct against PPV Virus. Plants 2019, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Canli, F.A.; Wang, X.; Sibbald, S. Genetic Transformation of Prunus domestica L. Using the hpt Gene Coding for Hygromycin Resistance as the Selectable Marker. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Du, F.; Wu, R.; Kong, J.; An, S. Construction and Optimization of a Genetic Transformation System for Efficient Expression of Human Insulin-GFP Fusion Gene in Flax. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Zhan, H.; Zhao, Y. A Reporter for Noninvasively Monitoring Gene Expression and Plant Transformation. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Lu, H.; Tang, D.; Hassan, M.M.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.-G.; Tuskan, G.A.; Yang, X. Expanding the Application of a UV-Visible Reporter for Transient Gene Expression and Stable Transformation in Plants. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, S.; Li, C. Progress and Challenges in Applying CRISPR/Cas Techniques to the Genome Editing of Trees. For. Res. 2022, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Orbović, V.; Wang, N. CRISPR-LbCas12a-mediated Modification of Citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, R.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Hyden, B.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Cao, H. Establishment of Genetic Transformation System of Peach Callus. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xue, Y.; Luo, J.; Han, M.; Liu, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, C. Developing a UV–Visible Reporter-assisted CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System to Alter Flowering Time in Chrysanthemum indicum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zheng, X.; Qu, W.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Miao, Y.-L.; Han, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. CRISPR-Offinder: A CRISPR Guide RNA Design and off-Target Searching Tool for User-Defined Protospacer Adjacent Motif. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhou, P.; Ma, Y.; Tan, W.; Huang, X.; Segbo, S.; Iqbal, S.; Shi, T.; Ni, Z.; Gao, Z. A NAC Family Gene PmNAC32 Associated with Photoperiod Promotes Flower Induction in Prunus mume. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cao, K.; Deng, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Fang, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Guan, L. An Integrated Peach Genome Structural Variation Map Uncovers Genes Associated with Fruit Traits. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhou, P.; Ma, C.; Tan, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Ni, Z.; Shi, T.; Hayat, F. Allelic Variation of PmCBF03 Contributes to the Altitude and Temperature Adaptability in Japanese Apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc.). Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3762–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.J.; Yim, D.G.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Shim, Y.Y.; Kang, S.N. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts of Balloon Flower Root (Platycodon grandiflorum), Japanese Apricot (Prunus mume), and Grape (Vitis vinifera) and Their Effects on Beef Jerky Quality. Foods 2024, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozyigit, I.I.; Dogan, I.; Hocaoglu-Ozyigit, A.; Yalcin, B.; Erdogan, A.; Yalcin, I.E.; Cabi, E.; Kaya, Y. Production of Secondary Metabolites Using Tissue Culture-Based Biotechnological Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1132555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meziani, R.; Mazri, M.A.; Essarioui, A.; Alem, C.; Diria, G.; Gaboun, F.; El Idrissy, H.; Laaguidi, M.; Jaiti, F. Towards a New Approach of Controlling Endophytic Bacteria Associated with Date Palm Explants Using Essential Oils, Aqueous and Methanolic Extracts from Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2019, 137, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mohammadi, R.; Akbari, R. The Effects of Cytokinin and Auxin Interactions on Proliferation and Rooting of Seedless Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. ‘Sultanine’. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2019, 61, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, S.; Ghori, N.; Hyat, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. Use of Auxin and Cytokinin for Somatic Embryogenesis in Plant: A Story from Competence towards Completion. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 99, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Gao, H.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Cai, J. Establishment of Tissue Culture System of Betula albosinensis. For. Res. 2021, 34, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cao, X.; Qin, C.; Chen, S.; Cai, J.; Sun, C.; Kong, L.; Tao, J. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators and Sucrose on Proliferation and Quality of Embryogenic Tissue in Picea pungens. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. Cyclanilide Induces Lateral Bud Outgrowth by Modulating Cytokinin Biosynthesis and Signalling Pathways in Apple Identified via Transcriptome Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.; Parvin, W.; Bashar, K.K.; Tareq, S.A.M.; Hossain, J.M.; Rahman, M.M. Micro-Propagation and Mass Production of Lophopetalum wightianum Arn., a Globally Threatened Evergreen Tree Species in Bangladesh. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2025, 161, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, D.; Erol, H.; Biçen, B.; Şimşek, Ö.; Aka Kaçar, Y. The Effects of Different Strength of MS Media on In Vitro Propagation and Rooting of Spathiphyllum. Anadolu J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 37, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J. Tissue Culture and Rapid Propagation Technology for Gentiana rhodantha. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, T.; Tang, T.; Cheng, B.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y. Development of Two Protocols for Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of White Clover (Trifolium repens) via the Callus System. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, L.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Jin, Y. Establishment and Validation of a Callus Tissue Transformation System for German Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.N.; Pan, J.; Cambon, A.; Chaires, J.B.; Garbett, N.C. Group Classification Based on High-Dimensional Data: Application to Differential Scanning Calorimetry Plasma Thermogram Analysis of Cervical Cancer and Control Samples. Open Access Med. Stat. 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shi, L.; Liang, X.; Zhao, P.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Chang, Y.; Hiei, Y.; Yanagihara, C.; Du, L.; et al. The Gene TaWOX5 Overcomes Genotype Dependency in Wheat Genetic Transformation. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. (Ed.) Agrobacterium Protocols: Volume 2; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1224, ISBN 978-1-4939-1657-3. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, H. Genetic Transformation Strategies in Fruit Crops. In Genetic Transformation; Alvarez, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, N. Highly Efficient Generation of Canker Resistant Sweet Orange Enabled by an Improved CRISPR/Cas9 System. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.-Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.-Q. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of VvMLO3 Results in Enhanced Resistance to Powdery Mildew in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; San José, M.C.; Vieitez, A.M.; Allona, I.; Aragoncillo, C.; Ballester, A. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of European Chestnut Somatic Embryos with a Castanea sativa (Mill.) Endochitinase Gene. New For. 2016, 47, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Bai, S.; Wang, N.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Dong, C. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of MdCNGC2 in Apple Callus and VIGS-Mediated Silencing of MdCNGC2 in Fruits Improve Resistance to Botryosphaeria dothidea. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 575477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, C.; Hirai, N.; Komori, S.; Wada, M.; Okada, K.; Osakabe, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Osakabe, Y. Efficient Genome Editing in Apple Using a CRISPR/Cas9 System. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaia, G.; Pavese, V.; Moglia, A.; Cristofori, V.; Silvestri, C. Knockout of Phytoene Desaturase Gene Using CRISPR/Cas9 in Highbush Blueberry. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1074541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, H. Increased Genome Editing Efficiency in Poplar by Optimizing sgRNA Length and Copy Number. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavese, V.; Moglia, A.; Corredoira, E.; Martínez, M.T.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Botta, R. First Report of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Castanea sativa Mill. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 728516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerva, L.; Dalla Costa, L.; Ciacciulli, A.; Sabbadini, S.; Pavese, V.; Dondini, L.; Vendramin, E.; Caboni, E.; Perrone, I.; Moglia, A. The Role of Italy in the Use of Advanced Plant Genomic Techniques on Fruit Trees: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Lozano, E.; Cabrera-Ponce, J.L.; Barraza, A.; López-Calleja, A.C.; García-Vázquez, E.; Rivera-Toro, D.M.; De Folter, S.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Editing of SlWRKY29 by CRISPR-Activation Promotes Somatic Embryogenesis in Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, F.; Puchta, H. The CRISPR/Cas Revolution Reaches the RNA World: Cas13, a New Swiss Army Knife for Plant Biologists. Plant J. 2018, 94, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Stürchler, A.; Anjanappa, R.B.; Zaidi, S.S.-A.; Hirsch-Hoffmann, M.; Gruissem, W.; Vanderschuren, H. Linking CRISPR-Cas9 Interference in Cassava to the Evolution of Editing-Resistant Geminiviruses. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).