Abstract

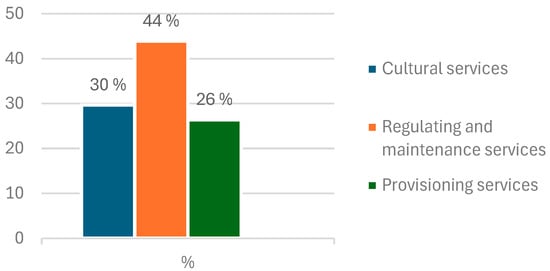

The study examines the extent to which the concept of ecosystem services is reflected in Estonian forestry legislation and how local communities and interest groups perceive and prioritise these services. Using a three-step methodology, the analysis combined (1) a content analysis of key legal acts—including the Forest Act, Nature Conservation Act, and related regulations; (2) a qualitative review of 26 forest management proposals submitted by communities to the State Forest Management Centre between 2021 and 2024; and (3) a comparative synthesis of legislative and community perspectives in order to identify their main areas of convergence and divergence. The findings reveal that provisioning services, particularly timber production, are most explicitly regulated, while regulating and cultural services appear mainly through indirect references. Community expectations, however, emphasise regulating (44%) and cultural (30%) services—especially habitat conservation, recreation, and landscape aesthetics—over provisioning benefits (26%). This discrepancy highlights a structural imbalance between legal framework and societal values. The study concludes that a more systematic integration of ecosystem services into forest management practice and regulations is required to achieve a balanced approach that accounts for ecological, social, and economic dimensions.

1. Introduction

Forest ecosystems perform a wide range of functions within society, providing both material and non-material benefits. In addition to provisioning services such as timber and other forest products, forests offer essential regulating and cultural services, including climate change mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and recreational and aesthetic values. The valuation and incorporation of these ecosystem services into legal and administrative frameworks are prerequisites for the sustainable management of forests and the preservation of both natural and cultural environments [1,2,3].

Estonian forest policy has historically been guided by the principle of multifunctionality, encompassing ecological, social, and economic dimensions. In the first Forest Act of the Republic of Estonia, adopted in 1934, forests were classified into protection forests and production forests. The former primarily served regulatory functions (such as soil protection and wind protection) but also fulfilled cultural roles, including heritage conservation and aesthetic purposes. In the Forest Act adopted in 1993 [4], the terms “forest category” and “primary function of forests” were used to denote the principal purpose assigned to forest land by law or pursuant to the law. As early as the 1990s and early 2000s, attention was paid to the non-timber values of forests—such as recreation, berry picking, hunting, and nature conservation—although the term “ecosystem services” was not yet in use.

Forest policy and the broader context of forest management are influenced by forest ownership structure and the legal responsibilities arising from different forms of ownership. Estonian forests are divided into state forests, municipal forests, and private forests. According to the 2023 National Forest Inventory [5], of Estonia’s 2.334 million hectares of forest land, 1.185 million hectares (50.4%) were state-owned (of which 1.07 million hectares are managed by the State Forest Management Centre, RMK), 1.16 million hectares (49.5%) were privately owned, and the ownership of 1320 hectares (0.1%) was unspecified. The Forest Act [6] applies equally to all owners, regardless of whether the owner is a natural person, a legal entity, the state, or a local government. The Act sets out the responsibilities of the state in the forestry sector, the most far-reaching of which is guiding forestry development through the preparation of sectoral development plans and forestry-related legislation. With regard to ownership categories, the state is responsible for governing and managing state forests and for supporting private forestry.

Within state forests, a specific category is formed by forests of high public interest (hereinafter HPI forests), which are located near settlements and are actively used by local residents. Under the Forest Act [6], the manager of state forests must involve local residents and stakeholders in planning forestry activities in forests situated near populated areas. Before planning management activities, RMK organises public discussions and invites written proposals. All proposals and their summaries are made publicly available on RMK’s website [7]. This participatory model provides valuable insights into which ecosystem services local communities prioritise and the extent to which their expectations align with or diverge from existing legal and economic approaches.

In this context, the aim of the present study is threefold:

- (1)

- to evaluate the extent to which Estonian forest management legislation reflects and supports the concept of ecosystem services;

- (2)

- to analyse which ecosystem services are emphasised in the proposals submitted by local residents and stakeholder groups regarding the management of HPI forests, administered by the State Forest Management Centre (RMK); and

- (3)

- to compare legislative and community perspectives in order to identify their principal areas of convergence and divergence.

International developments such as the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [1] and the European Commission’s TEEB framework [8] influenced the adoption of the ecosystem services concept in Estonia during the 2010s. A study launched and published in 2012 [9] sought to introduce the concept of ecosystem services in Estonia and to explain, based on a literature review, the various interpretations of the concept and the reasons underlying those differences. Among other contributions, the study provided an overview of methods and approaches for assessing the value of benefits supplied by the natural environment, as well as the possibilities for integrating ecosystem services into decision-making and policy development at national, local government, and enterprise levels.

The concept was also adopted in forestry sector and integrated into strategic forest planning. Initially, this shift represented primarily a terminological adjustment. However, as the new term became established in natural resource management and the importance of accounting for the value of ecosystem services was increasingly emphasised, forest policy gradually shifted from sector-specific benefits toward a more integrated ecosystem services logic. For example, the Estonian Forestry Development Plan until 2020 [10] addressed the importance of forest habitats, carbon sequestration, recreational areas, and hunting, referring to these as environmental services. This marked a transition to a more systematic approach, in which non-timber forest values came to be understood as benefits that could be assessed, mapped, and incorporated into decision-making processes.

Active application of the ecosystem services concept began with the baseline study conducted for the preparation of the Forestry Development Plan 2030 [11]. During the drafting of the development plan, stakeholders likewise emphasised the need to integrate natural-value accounting more effectively into forest management planning.

The monetary valuation of ecosystem services helps make the previously invisible benefits of nature comparable and thereby supports more balanced decision-making between environmental and economic objectives [12]. However, the monetary assessment of many services—particularly cultural and supporting ecosystem services—is methodologically challenging, as their value is not reflected in market prices and cannot be directly measured. Estonian research has illustrated this complexity well. Sirgmets et al. [13] demonstrated that expanding the area of strictly protected forests could reduce the potential income from forestry by 0.8%–2% annually, whereas Adermann et al. [14] found that the monetary value of carbon sequestration could exceed timber revenues severalfold. These studies highlight both the potential and the limitations of the economic valuation of ecosystem services, yet they do not account for perception-based or subjective values. Fujimoto’s [15] study in the Järvselja region introduced this dimension, showing that monetary and subjective valuations may differ significantly. This divergence underscores the need to integrate economic and qualitative approaches in the valuation of ecosystem services to inform evidence-based forestry policy that aligns with societal expectations.

At present, the consideration of natural values is regulated by several legal acts, such as the Forest Act [6] and the Forest Management Regulation [16]. However, a systematic approach that would include the application of monetary valuation of ecosystem services in forest management planning is still lacking.

In Estonia, the assessment of ecosystem services has been primarily based on the ELME projects (2015–2023) [17], which mapped the distribution and condition of ecosystems, identified 27 ecosystem services, and evaluated them using approximately 70 indicators. Within the framework of ELME2, a methodology for the economic valuation of ecosystem services was developed, and maps illustrating the values of selected services—including monetary unit estimates—were produced [18]. Although the ELME projects have established a strong foundation for ecosystem service accounting, their practical implementation has remained uneven. The “Draft Forestry Development Plan up to 2030” [3] likewise emphasises the need to consider climate impacts, biodiversity, and social values. In practice, however, the focus continues to rest predominantly on provisioning services, particularly timber production. The draft plan highlights the importance of recognising non-market benefits such as recreation, landscape aesthetics, and cultural heritage, which provide significant societal value yet are difficult to quantify in monetary terms. According to data from the State Forest Management Centre (RMK), the recreational and educational use of forests has increased substantially in recent years, indicating a growing public appreciation of these non-material benefits [19].

Several international studies highlight the importance of measuring, mapping, and conducting monetary valuation of ecosystem services in ensuring their continued provision and in shaping effective natural resource management practices [20,21,22]. The extent to which legislative acts and regulations influence the provision of ecosystem services has been examined by only a limited number of authors, predominantly within the contexts of governance or forest policy [21,22,23]. A study by Nichiforel et al. [23] demonstrated that the delivery of forest ecosystem services in Romania remains closely tied to the normative forest management planning process. The authors also emphasise the need to adapt the regulatory governance framework for forest ecosystem services, for example, by incorporating bottom-up participatory approaches. Winkel et al. [24] introduce several EU-level policy pathways that could enhance the provision of diverse forest ecosystem services in Europe. One of these pathways is the establishment of a coherent regulatory policy framework that integrates a range of policy instruments across both European and national levels.

Although the concept of ecosystem services has become well established in Estonian scientific research, its implementation within forest policy remains at an early stage of development. The current situation is characterised by a clear tension: while international frameworks and scientific evidence underscore the importance of integrating ecosystem services, forest management practices continue to be primarily oriented towards timber production. Nevertheless, accounting for ecosystem services is crucial not only for meeting international obligations but also for achieving a balanced consideration of the economic, ecological, and societal dimensions of forestry. Community proposals submitted to the RMK offer valuable insights into which ecosystem services are perceived as most significant by local communities and stakeholder groups. Given the close interlinkages between the ecosystem services framework and policies in spatial planning, forestry, and nature conservation, it is essential to understand the extent to which these values are reflected in the national legislative framework.

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the treatment of ecosystem services in Estonian forestry legislation and to analyse societal expectations and opportunities for a more systematic implementation of ecosystem services in the management of forests important to local communities. Integrating ecosystem services that are significant to the population into forest management planning would help to balance the sector’s economic competitiveness with the social and ecological well-being. When the classification, mapping, and valuation of ecosystem services have been examined in Estonia for more than a decade, the systematic analysis of forest legislation using CICES classification has not previously been studied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets and Selection Criteria

The analysis was based on two main datasets: forest-related legislation and proposals submitted by local communities. The initial coding was conducted in May 2025, followed by verification and consensus adjustments in August 2025. Any discrepancies were discussed, and the methodology and coding rules were refined where necessary. Coding and summary tables were compiled in MS Excel, as the dataset size was manageable without the need for specialised analytical software.

To identify ecosystem services, the study applied the “Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services” (CICES), version 5.1 [18], which distinguishes three main service groups: provisioning, regulation and maintenance, and cultural services. The coding framework was developed on the basis of previous ecosystem service assessment and mapping projects, “ELME1” and “ELME2” [25], which defined CICES categories adapted to the Estonian context. After pilot coding, six additional CICES service categories were added, as they appeared repeatedly in community proposals but were not included in the initial framework (e.g., noise regulation, and inspiration for culture, art, and design, etc.).

The study examined the current versions of the Nature Conservation Act [26], the Forest Act [6], and regulations adopted under it: the Forest Management Regulation [16], the Forest Inventory Guidelines [27], and the Classification of Key Habitats [28]. The inclusion criterion was any legal act that regulates or guides the principles, restrictions, or value orientations of forest management (Appendix A). Together, these texts form the institutional framework through which the study assesses how the principles of ecosystem services are incorporated into national forest management related legislation.

The analysis of the community perspective was based on documents published on the website of the RMK between 2021 and 2024, concerning forests of heightened public interest (HPI forests) [7]. The dataset included summaries of 26 different HPI forest areas across 15 municipalities (one document per area).

2.2. Content Analysis of Legal Acts

The content analysis of legal acts was conducted in two stages. First, a full-text search was carried out using the keywords “ecosystem service” and “nature’s benefit” to identify direct references to ecosystem services. In addition, specific keywords corresponding to CICES service categories—such as “aesthetics”, “microclimate”, “recreation”, etc., (Appendix B).

In the second stage, all legal texts were read in full, and each provision was assessed to determine the extent to which it considered a particular ecosystem service. Each paragraph was coded as either “Yes”, “Indirect”, or “No”. A “Yes” label was assigned when a provision explicitly or implicitly supported the maintenance of an ecosystem service, even if it did not directly use ecosystem service terminology. “Indirect” indicated partial consideration of a service without substantial contribution to its preservation, while “No” was used when no relevant regulatory reference could be identified. For each identified reference, the corresponding service category and a brief justification were recorded.

2.3. Content Analysis of Community Proposals

In the content analysis of community proposals, the main unit of analysis was a text excerpt from an individual proposal. When the same ecosystem service was described within a single excerpt using multiple expressions, it was treated as one semantic unit. References were classified into two types: direct references, where the service was explicitly mentioned (e.g., “berries”, “carbon sequestration”), and indirect references, where the service was not named directly but the meaning was clearly associated with a specific service (e.g., “the beauty of nature”—aesthetic service, Appendix B). Technical or administrative passages without substantive relevance to ecosystem services were excluded from the analysis, and duplicate content was counted only once. The methodology followed previous studies that identified direct and indirect references to ecosystem services in planning documents [29].

The inclusion criteria were official, content-based summaries published by RMK; duplicate files and formal notifications were excluded. In total, 133 substantive proposal excerpts were identified from the documents, of which 84 originated from local residents or community groups, 34 from non-governmental organisations, and 13 from representatives of local municipalities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ecosystem services and corresponding keywords mentioned in the HPI forest proposals submitted to RMK (based on CICES v5.1). Numbers in parentheses indicate the frequency of occurrences.

The calculation of ecosystem service proportions was based on the internal distribution within each service group (cultural, regulating, and provisioning services). First, the total number of occurrences of services within each group across all analysed documents was determined. All services belonging to the same category were then summed to obtain the total count for that service group. Subsequently, the proportion of each individual service within its group was calculated by dividing the number of its occurrences by the total number of occurrences within that group. Thus, the percentages presented in the graphs represent the relative frequency of each service within its respective category.

2.4. Limitations

The interpretation of the results should consider several limitations. The findings of this analysis are based on proposals prepared by local communities, which reflect the perceptions, value judgments, and priorities of participating residents. Therefore, the results are not statistically representative of all state forests in Estonia; however, they provide a meaningful reflection of common value conflicts and local expectations regarding the management and decision-making practices of the State Forest Management Centre (RMK). Secondly, the identification of indirect references is inherently interpretative. This limitation was mitigated through the use of a coding framework, pilot coding, and collective discussions to ensure consistency. Thirdly, legal acts and community texts differ in their purpose, language, and level of detail, which may result in similar themes being expressed in different ways.

OpenAI ChatGPT 5.1 was used solely to improve linguistic clarity and ensure consistency of terminology. The tool was not used for generating data, codes, or figures.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Legal Acts

The Nature Conservation Act [26] aims to ensure the preservation of biological diversity by protecting natural habitats and maintaining favourable conditions for species of fauna, flora, and fungi. It also seeks to safeguard natural environments of cultural and aesthetic value. Nature conservation is guided by the principles of sustainable development, which require that alternative solutions be considered in each decision-making process (Nature Conservation Act §1–2). The Act addresses ecosystem services more broadly and systematically than the Forest Act, encompassing all three categories of services—cultural, regulating, and provisioning.

The Forest Act [6] aims to ensure the protection and sustainable management of forests as ecosystems. According to the Act, forest management is considered sustainable when it maintains biodiversity, forest productivity, regeneration capacity, and vitality, while enabling multifunctional forest use that satisfies ecological, economic, social, and cultural needs (Forest Act §2). The objective of the Act is comprehensive, seeking to balance various interests and to ensure the interaction of the forest’s ecological, economic, and social functions. The Forest Management Regulation [16] specifies the provisions of the Forest Act by establishing concrete technical standards, such as the minimum age and conditions for regeneration felling. The regulation directly supports provisioning services, particularly timber production, but lacks a systematic approach to regulating and cultural services. Therefore, its contribution to ecosystem services is mainly limited to maintaining forest productivity (Table 2). The Forest Inventory Guideline [27] governs forest inventory procedures and the preparation of management plans. While the guideline enables the collection of data on biodiversity, protected species, and other ecosystem components, its primary focus remains on forest management planning. Ecosystem services are not explicitly addressed, meaning that their assessment and consideration depend largely on the initiative of inventory compilers and decision-makers.

Table 2.

Ecosystem services and their treatment in Estonian legal acts. Titles written in italics indicate regulations established under the Forest Act.

The Key Habitat Regulation [28] represents one of the few legal instruments that explicitly links ecosystem services with nature conservation values. The Key Habitat Classifier and its accompanying selection manual establish a mechanism for habitat protection, thereby directly supporting regulating and maintenance services, including biodiversity conservation. However, the protection mechanism relies heavily on the voluntary participation of forest owners, which renders the system somewhat uncertain.

Table 2 provides an overview of how different legal acts address ecosystem services based on the CICES classification [30]. A clear pattern emerges: provisioning services are most extensively regulated under the Forest Act [6] and the Forest Management Regulation [16]; regulating services dominate in the Nature Conservation Act [26] and the Key Habitat Regulation [28]; and cultural services are primarily acknowledged at a conceptual level. However, the implementation of cultural services often depends on local-level initiatives and community engagement.

Overall, the legal acts complement one another: the Forest Act [6] and its implementing regulations primarily address provisioning services, while the Nature Conservation Act [26] and the Key Habitat Regulation [28] predominantly support regulating and cultural services. However, there is no unified framework that ensures a balance among the three categories of ecosystem services. This pattern is not unique to Estonia: international studies have similarly found that ecosystem services are incorporated into legal frameworks in a fragmented manner, often through indirect references [31].

3.2. Ecosystem Services Reflected in the HPI-Forest Management Proposals Submitted to the RMK

The results of the analysis indicate that the management proposals for HPI-forests place the greatest emphasis on regulating and maintaining ecosystem services (44%) (Figure 1), referring primarily to habitat conservation, the protection of natural values, and protective functions such as wind and noise regulation. The second most frequently highlighted category comprises cultural services (30%), which mainly reflect recreational opportunities, aesthetic appreciation, and functions related to leisure and health. Provisioning services account for a somewhat smaller proportion (26%), referring chiefly to the importance attributed to timber, berries, and mushrooms. It should be noted, however, that timber harvesting is mentioned predominantly in an indirect context—mainly in relation to forest maintenance or sanitary felling needs, rather than as a primary objective of forest use. Overall, this distribution suggests that community members’ expectations of HPI-forests are diverse, encompassing conservation, cultural, and economic values.

Figure 1.

Distribution of ecosystem services identified from the proposals according to CICES V5.1 categories.

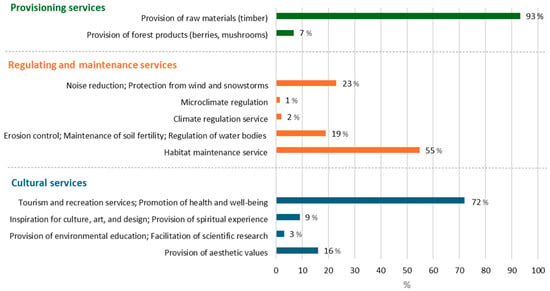

Within the category of cultural services, community members most frequently value tourism and recreation services, along with the promotion of health and well-being (72%) (Figure 2). The key themes relate to the preservation of recreational forests, health trails, and other leisure opportunities, which are regarded as integral to community well-being. The second most prominent aspect is aesthetic value (16%), where respondents emphasise the need to maintain the visual beauty of forest landscapes and the attractiveness of the area. Spiritual and cultural values (9%) encompass the role of forests in preserving local cultural heritage, historical sites, and spiritual connections. The least frequently mentioned aspect is the facilitation of environmental education and scientific research (3%), although respondents highlight the importance of these forests in supporting outdoor learning activities for local schools.

Figure 2.

Distribution of ecosystem services mentioned in community forest management proposals by service type. Percentages represent the share of each service within its respective service group (each group totals 100%).

Among regulating and supporting services, the most frequently mentioned is the habitat preservation service (55%). The proposals emphasise the role of forests in maintaining natural habitats, key biotopes, and biodiversity. The second most frequently cited service is the reduction in noise and protection against wind and snowstorms (23%). Soil fertility maintenance and water regime regulation are mentioned less frequently (19%), with the main concern related to the use of heavy forestry machinery that causes deep ruts in the soil. The proposals express a desire for forestry operations to be carried out carefully and in an environmentally sustainable manner, avoiding soil damage and visual disturbance of the landscape. Climate regulation services account for a smaller share (2%), focusing mainly on carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation. The least mentioned service is microclimate regulation (1%). In the category of provisioning services, the clear dominant service is the supply of raw materials (wood), which is mentioned in 93% of the proposals. Although wood is not generally viewed as the primary goal, it is still regarded as an important forest good, closely linked to preferred logging methods, such as continuous-cover forestry or thinning. The provision of non-timber forest products (berries, mushrooms) is mentioned much less frequently (7%), yet these are still valued as an important local food source and as part of traditional forest use.

3.3. Comparison of Legal Acts and Community Proposals

The prioritisation of different ecosystem services and the establishment of management rules for them vary to some extent between legislative acts and the proposals made by local residents. It must be acknowledged, of course, that legislative acts have their own specific purposes—for example, the Nature Conservation Act [26] and the Forest Act [6] serve distinct roles. Consequently, these acts address ecosystem services from different perspectives, taking into account all forests across the country. In contrast, the proposals made by residents are primarily based on their perceptions of the role of nearby forests in their living environment. A comparison of the legislative framework and residents’ viewpoints is presented in Table 3 by groups, highlighting both the convergence and divergence of ecosystem services.

Table 3.

Comparative overview of ecosystem service groups: coverage in Estonian legal acts and importance to local communities.

4. Discussion

The study confirms that ecosystem services are addressed unevenly and predominantly indirectly in Estonia’s forestry law. The Forest Act [6] focuses mainly on provisioning services (especially timber production), whereas regulating services are only partially and cultural services barely covered; by contrast, the Nature Conservation Act [26] primarily supports regulating and cultural services, leaving the economic dimension largely secondary. A unified framework that would balance provisioning, regulating, and cultural services has not yet emerged. A similar pattern is described internationally: ecosystem services enter legal frameworks in a fragmented manner and often through indirect references, which limits comprehensive accounting of their overall contribution to societal well-being [31].

Our analysis shows that ecosystem services enter the legal domain in three ways: (1) direct norms (e.g., logging restrictions, zoning regimes), (2) indirect principles (e.g., sustainability, non-deterioration of the water regime), and (3) procedural instruments (e.g., protection and management plans, public participation). International literature indicates that these instruments are applied diffusely across sectors and institutions, resulting in a piecemeal treatment [32]. Stronger policy coherence and mainstreaming are needed [31,33]. At the European level, the “EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030” [2] and the 2021 “EU Forest Strategy” [34] set the direction, encouraging the integration of ecosystem services values into policy and legal instruments. Research on spatial planning and environmental impact assessment shows that when ecosystem services accounting is made a mandatory procedural step in plans and assessments, it becomes standard practice; however, its depth and quality vary by context and institution [35].

It emerged that the management proposals for HPI-forests reflect diverse expectations, highlighting the significant role of forests in maintaining ecological, social, and economic values. Regulating and maintenance services are considered the most important—above all the protection of habitats and the preservation of natural protective functions. Similar results have been reported in international studies [36,37], indicating that communities tend to associate forests more with ecological and social benefits than with economic raw material. According to Janeczko et al. [38] who assessed the relevance of forest ecosystem services depending on the socio−demographic profiles of respondents, regulatory services were most important to respondents, followed by cultural services and least important were provisioning services. Cultural services are underrepresented in the legal framework, even though forests’ contributions to aesthetic values, education, and mental and physical well-being are often the most tangible benefits for communities [36,37]. This exacerbates tensions between forest owners’ resource-oriented perspectives and local residents’ ecological and cultural expectations.

Both our results and studies from the near region point to a consistent value hierarchy. Estonian communities prioritise regulating and maintenance services (notably habitat protection and natural protective functions), underscoring risk perception and dependence on ecosystem functioning. Among cultural services, recreational and health benefits are highlighted, entrenching forests’ role in everyday well-being. In Northern Europe, links between forests and health benefits have been shown repeatedly [39], helping to explain why Estonian public opinion results align with this broader trend. Provisioning services, particularly timber harvesting, are more acceptable when implemented with lower-intensity methods (selection and thinning), which reduce conflicts among ecosystem services. The implementation of alternative management practices alongside clear-cutting and even-aged stands would help maintain late-successional forest structures and support biodiversity, carbon stocks, and forest resilience [40].

The policy implication is clear: to reduce tensions between forestry and nature conservation, the legal framework must be rebalanced. In practical terms, legislation and forest management planning should consider the cumulative impacts of different management regimes on ecosystem services, rather than only isolated effects [11]. Accordingly, the Forest Management Regulation [16] should be updated so that, alongside productivity, systematic assessments are made of impacts on biodiversity, climate regulation, and recreational values. The planning practice of HPI-forest management in Estonia follows the approach emphasised by Winkel et al. [24], which involves granting forest-related societal groups access to policymaking processes at the appropriate scale and within the relevant context, thereby ensuring transparent decision-making. The shift from single-function to multifunctional forests makes stakeholder decision-making more complex, and local communities are one of many actors.

5. Conclusions

The results of the analysis indicate that the treatment of ecosystem services in Estonian forest-related legislation is fragmented and uneven. Three main conclusions can be drawn: (1) Provisioning services are the most comprehensively regulated, particularly in the Forest Act and its implementing regulations, which focus primarily on forest resource management and the maintenance of stand productivity. Other provisioning services, such as those for berries, mushrooms, and medicinal plants, are addressed only indirectly. (2) The treatment of regulating and maintenance services is inconsistent. The Nature Conservation Act highlights habitat protection, climate regulation, and the safeguarding of water and soil resources, whereas the Forest Act refers to these functions only indirectly. The Key Habitat Regulation provides the most concrete support in this regard, directly linking habitat protection with forest management practices. (3) Cultural services are the least represented in legislation. Although the Forest Act mentions multifunctional forest use, aesthetic, spiritual, and educational values remain marginal and are addressed in more detail only in the Nature Conservation Act through the establishment of national parks and local protected areas.

The analysis of proposals concerning HPI forests revealed that local communities primarily value the ecological and social functions of forests. Wood was regarded as an important but not a primary forest good. Overall, the proposals reflect an understanding of forests as public goods, the main value of which lies in their ecological and social functions rather than in economic productivity alone.

Comparison of legislative and community perspectives revealed both overlaps and differences. Both legal acts and communities emphasise the importance of habitat protection and biodiversity, demonstrating strong alignment in the area of regulating and maintenance services. However, there is a notable divergence in the treatment of cultural services: communities attach much greater importance to the recreational and spiritual functions of forests than is reflected in current legislation. For provisioning services, partial convergence was observed; both acknowledge the importance of timber, but communities favour sustainable, small-scale, and locally appropriate use. Achieving balance requires a coherent and integrated approach that treats provisioning, regulating, and cultural services as interdependent components of a single system.

This necessitates adjustments to legislative and administrative mechanisms to ensure that ecological, economic, and social objectives are addressed as mutually supportive rather than separate. It is particularly important to update the Forest Management Regulation so that it incorporates a holistic treatment of ecosystem services and provides a framework for systematic impact assessment. Updating the regulation could strengthen linkages between forest policy, climate policy, and biodiversity strategies, thus creating a more coherent framework that supports balanced consideration of all ecosystem service categories.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The analysis focused on selected cases of HPI forests, and therefore the results may not fully reflect the diversity of community perspectives across Estonia. The analysis relied on community proposals that represent the perceptions and priorities of participating residents, rather than statistically representative samples. Legal texts and community proposals also differ in purpose, language, and level of detail, which may result in similar themes being expressed differently. Furthermore, the study focused on a subset of ecosystem service categories adapted to the Estonian context, which may not capture all relevant services in other frameworks.

Given the focus and results of this study, it is important to further investigate how the management of HPI forests can enhance both ecological and social outcomes, and what trade-offs and synergies exist among forest ecosystem services. Developing appropriate management models for these forests that balance recreation, timber production, and biodiversity is essential. Future research should also assess the socio-economic impacts of HPI forest management, including its contribution to local quality of life, rural development, and social cohesion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and K.K.; methodology, P.K. and K.K.; formal analysis, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; project administration, P.K.; funding acquisition, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Environmental Investment Centre, grant number RE.4.08.23-0122.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RMK | State Forest Management Centre |

| HPI-forests | Forest with high public interest |

Appendix A

Data on Legal Acts. Titles written in italics indicate regulations established under the Forest Act. The table presents the legislative documents examined in the study, indicating the version date, official source, and date of download.

Table A1.

Legal Acts included in the analysis.

Table A1.

Legal Acts included in the analysis.

| Document | Date of Version | Source/URL | Date of Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature Conservation Act | 4 December 2024 | https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/104122024013 | 13 February 2025 |

| Forest Act | 19 December 2024 | https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/MS | 13 February 2025 |

| Forest Management Regulation | 13 July 2023 | https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/113072023034 | 13 February 2025 |

| Forest Inventory Guideline | 31 May 2024 | https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/13124148?leiaKehtiv | 13 February 2025 |

| Key Habitat Classification | 29 December 2024 | https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/116122010003?leiaKehtiv | 13 February 2025 |

Appendix B

Coding Framework for Ecosystem Services. The table provides definitions, classifications, and typical keywords used to identify direct or indirect references to ecosystem services in legal texts and community proposals. The initial set of codes was established prior to the analysis, based on the CICES v5.1 framework and relevant literature. Additional codes were added inductively during the coding process when recurrent themes emerged that were not captured by the predefined categories.

Table A2.

Coding framework for identifying ecosystem services and their corresponding CICES v5.1 categories.

Table A2.

Coding framework for identifying ecosystem services and their corresponding CICES v5.1 categories.

| Code (CICES v5.1) | Ecosystem Service | Service Category | Description | Example Keywords or Expressions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1.5.1 | Provision of forest products (berries, mushrooms) | Provisioning | Collection of natural forest products (e.g., berries, mushrooms) for food or trade. | berries, mushrooms, forest products, wild food |

| 1.1.5.2; 1.1.5.3 | Provision of medicinal and ornamental plants | Provisioning | Harvesting of plants and plant parts for medicinal or decorative purposes. | medicinal plants, herbs, decorative branches, ornamental plants |

| 1.1.1.2 | Provision of raw materials (timber) | Provisioning | Extraction of timber and other materials for industrial or domestic use. | timber, logs, felling, selective cutting, continuous cover forestry, sanitary cutting, forest management method, shelterwood cutting, tending cutting, thinning, clear-cutting, protective cutting, gap cutting |

| 1.1.6.1 *; 1.1.6.2 * | Provision of wild game and materials | Provisioning | Provision of wild animals for food, fur, or other materials. | hunting, wild meat |

| 1.2.1.2 * | Provision of genetic resources | Provisioning | Provision of genetic material from forest species for breeding or biotechnological use. | genetic diversity, species conservation, genetic resources |

| 2.2.2.2; 2.2.2.3 | Habitat maintenance and conservation | Regulating and maintenance | Maintenance of habitats and ecological conditions supporting biodiversity. | habitat, nesting site, colony, species protection, key habitat, nature conservation, habitat, nesting period, old-growth forest, natural regeneration, biodiversity, natural value, ecological diversity |

| 2.2.1.1 | Erosion control | Regulating and maintenance | Role of vegetation in stabilising soil and preventing erosion. | erosion, slope stability, soil protection |

| 2.2.1.3 | Regulation of water bodies and flood protection | Regulating and maintenance | Contribution of vegetation and wetlands to water balance and flood prevention. | flood prevention, water retention, riverbank |

| 2.1.2.2 | Noise reduction | Regulating and maintenance | Role of vegetation and forests in dispersing and reducing noise. | noise barrier, buffer zone, noise mitigation |

| 2.2.1.4; 2.2.1.2 | Protection from wind and snowstorms | Regulating and maintenance | Physical protection provided by forests against wind, snow, and storms. | windbreak, buffer zone, wind protection |

| 2.2.6.1 | Climate regulation service | Regulating and maintenance | Regulation of climate through carbon sequestration and temperature moderation. | carbon sequestration, CO2 absorption, climate mitigation; climate change; greenhouse gas |

| 2.2.4.1; 2.2.4.2 | Maintenance of soil fertility | Regulating and maintenance | Nutrient cycling and preservation of soil fertility through ecosystem processes. | soil fertility, nutrient cycling, humus formation, soil protection |

| 2.2.2.1 * | Pollination | Regulating and maintenance | Contribution of forests and grasslands to plant pollination by insects and other organisms. | pollinators, bees |

| 2.1.1.2 * | Air quality regulation | Regulating and maintenance | Filtering of air pollutants and improvement of air quality by vegetation. | clean air, air filtration |

| 2.1.2.1 * | Regulation of waste and toxic substances | Regulating and maintenance | Absorption, decomposition, or storage of pollutants in natural systems. | self-purification, pollutant breakdown, filtering capacity |

| 2.2.6.2 | Microclimate regulation | Regulating and maintenance | Balancing local temperature and humidity through vegetation cover. | shade, cooling effect, microclimate |

| 3.1.1.1 | Tourism and recreation | Cultural | Opportunities provided by nature for recreation, leisure, and tourism activities. | hiking, recreation, tourism, relaxation, recreational forest, peri-urban forest, foraging, health trail |

| 3.1.1.2 | Promotion of health and well-being | Cultural | Contribution of natural environments to physical and mental health. | relaxation, well-being, fresh air, stress relief, mental and physical health |

| 3.1.2.4 | Provision of aesthetic values | Cultural | The beauty and aesthetic experience of natural landscapes. | landscape beauty, view, aesthetic experience, aesthetics, regional attractiveness |

| 3.1.2.2 | Provision of environmental education | Cultural | The role of nature in educational and awareness-raising activities. | environmental education, outdoor learning, awareness |

| 3.1.2.3; 3.2.1.1; 3.2.1.2 | Provision of spiritual experiences | Cultural | Spiritual, symbolic, or religious meanings associated with nature. | sacred site, spirituality, cultural site, cultural heritage |

| 3.1.2.1 | Support for scientific research | Cultural | Use of natural environments for scientific observation and research. | fieldwork, monitoring, scientific study |

| 3.2.1.3 | Inspiration for culture, art, and design | Cultural | Inspiration derived from nature for creative expression, art, and design. | inspiration, creativity, art, design |

Note. * CICES codes marked with an asterisk were not used in the HPI forest proposals, as no corresponding references or keywords emerged from the submitted texts.

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Ed.) Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Series; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59726-040-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Commission EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Ministry of Climate of the Republic of Estonia Forestry Development Plan 2021–2030. Available online: https://kliimaministeerium.ee/MAK2030 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Republic of Estonia. Forest Act, RT I 1993, 69, 990. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Estonian Environment Agency. Yearbook Forest 2023; Estonian Environment Agency: Tallinn, Estonia, 2025.

- Republic of Estonia. Forest Act RT I, 19.12.2024. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- State Forest Management Centre (RMK) Forest Work Plans (Metsatööde Plaanid). Available online: https://rmk.ee/metsatood/kogukonnaalad/metsatoode-plaanid/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- CBD Secretariat the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB). Available online: https://www.cbd.int/incentives/teeb (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Sall, M.; Uustal, M.; Peterson, K. Ecosystem Services—Overview of the Benefits Provided by Nature and Their Monetary Value; Sustainable Estonia Institute (SEI Tallinn): Tallinn, Estonia, 2012; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment of Estonia. Estonian Forestry Development Plan Until 2020; Ministry of the Environment of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2010.

- Estonian University of Life Sciences. University of Tartu. In Ecosystem Services of Estonian Forests; Baseline Study for the Estonian Forestry Development Plan Until 2030; Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia; University of Tartu: Tartu, Estonia, 2018; pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty Years of Ecosystem Services: How Far Have We Come and How Far Do We Still Need to Go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgmets, R.; Kaimre, P.; Padari, A. Economic Impact of Enlarging the Area of Protected Forests in Estonia. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adermann, V.; Padari, A.; Sirgmets, R.; Kosk, A.; Kaimre, P. Valuation of Timber Production and Carbon Sequestration on Järvselja Nature Protection Area. For. Stud. 2015, 63, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S. Prioritization of Ecosystem Services on the Example of Järvselja Nature Reserve Using Analytic Hierarchy Process. Master’s Thesis, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Tartu, Estonia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Estonia. Forest Management Regulation, RT I, 13.06.2025, 14. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Estonian Environment Agency ELME—Tools Necessary for Assessing Environmental Status, Forecasts, and Data Availability Related to Biodiversity, Socio-Economic and Climate Change Factors. Available online: https://keskkonnaagentuur.ee/elme (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Helm, A.; Kull, A.; Kiisel, M.; Poltimäe, H.; Rosenvald, R.; Veromann, E.; Reitalu, T.; Kmoch, A.; Virro, H.; Mõisja, K.; et al. National Assessment and Mapping of the Socio-Economic Value of Terrestrial Ecosystem Services in Estonia. Final Technical Report; University of Tartu: Tartu, Estonia; Estonian University of Life Sciences: Tartu, Estonia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- State Forest Management Centre (RMK) Facts and Figures 2024. Available online: https://rmk.ee/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/RMK_faktid_ja_numbrid.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Primmer, E.; Furman, E. Operationalising Ecosystem Service Approaches for Governance: Do Measuring, Mapping and Valuing Integrate Sector-Specific Knowledge Systems? Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, E.; Furman, E. How Have Measuring, Mapping and Valuation Enhanced Governance of Ecosystem Services? Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 67, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Baral, H. Governing Forest Ecosystem Services for Sustainable Environmental Governance: A Review. Environments 2018, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Duduman, G.; Scriban, R.E.; Popa, B.; Barnoaiea, I.; Drăgoi, M. Forest Ecosystem Services in Romania: Orchestrating Regulatory and Voluntary Planning Documents. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G.; Lovrić, M.; Muys, B.; Katila, P.; Lundhede, T.; Pecurul, M.; Pettenella, D.; Pipart, N.; Plieninger, T.; Prokofieva, I.; et al. Governing Europe’s Forests for Multiple Ecosystem Services: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policy Options. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 145, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estonian Environment Agency. Countrywide Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and Their Services. Available online: https://loodusveeb.ee/en/countrywide-MAES-EE (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Republic of Estonia. Nature Conservation Act, RT I, 12.07.2025, 17. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Estonia. Forest Inventory Guideline, RT I, 31.05.2024, 11. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Estonia. Key Habitat Classifier, Selection Guidelines, Protection Management, and Detailed Principles for Calculating Compensation and Use Fees, RT I, 29.12.2024, 54. In State Gazette (Riigi Teataja); Republic of Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.; Sherren, K.; Duinker, P.N. The Use of Ecosystem Services Concepts in Canadian Municipal Plans. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 38, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin-Young, M. Marion Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) Version 5.1: Guidance on the Application of CICES; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018.

- Primmer, E.; Varumo, L.; Krause, T.; Orsi, F.; Geneletti, D.; Brogaard, S.; Aukes, E.; Ciolli, M.; Grossmann, C.; Hernández-Morcillo, M.; et al. Mapping Europe’s Institutional Landscape for Forest Ecosystem Service Provision, Innovations and Governance. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 47, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, E.; Jokinen, P.; Blicharska, M.; Barton, D.N.; Bugter, R.; Potschin, M. Governance of Ecosystem Services: A Framework for Empirical Analysis. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; et al. (Eds.) IPBES (2019): Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Forest Strategy for 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Geneletti, D. Reasons and Options for Integrating Ecosystem Services in Strategic Environmental Assessment of Spatial Planning. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2011, 7, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C.; Martín-López, B. Socio-Cultural Valuation of Ecosystem Services: Uncovering the Links between Values, Drivers of Change, and Human Well-Being. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbés-Blázquez, M.; González, J.A.; Pascual, U. Towards an Ecosystem Services Approach That Addresses Social Power Relations. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Banaś, J.; Woźnicka, M.; Zięba, S.; Banaś, K.U.; Janeczko, K.; Fialova, J. Sociocultural Profile as a Predictor of Perceived Importance of Forest Ecosystem Services: A Case Study from Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The Influence of Urban Green Environments on Stress Relief Measures: A Field Experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuluvainen, T.; Gauthier, S. Young and Old Forest in the Boreal: Critical Stages of Ecosystem Dynamics and Management under Global Change. For. Ecosyst. 2018, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).