Abstract

This article presents a cooperative framework for multi-robot wildfire monitoring that integrates dynamic Voronoi partitioning with large language model (LLM)-enhanced nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) to address challenges in dynamic unknown environments. Conventional methods, particularly fixed-weight NMPC, lack adaptability in scenarios with suddenly changing obstacles, such as spreading fire fronts. Our approach employs a hierarchical architecture. At the task allocation level, an enhanced dynamic Voronoi algorithm ensures robust and collision-free area partitioning. At the motion control level, we innovatively leverage the semantic reasoning capability of LLMs to dynamically adjust the cost function weights of the NMPC in real time based on environmental features, overcoming the parameter rigidity of traditional controllers. Extensive simulations in benchmark environments demonstrate the framework’s superior performance over deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) and fixed-weight NMPC baselines, showing significant improvements in exploration efficiency and obstacle avoidance success rate. This work provides a viable solution that bridges high-level semantic cognition with low-level optimal control for robust autonomous surveillance.

1. Introduction

With continued technological advances, robots, as highly autonomous and programmable entities, have demonstrated significant advantages in many fields, such as industry, agriculture, medicine, military, and entertainment [1]. In particular, robots often play an irreplaceable role when exploring high-risk or inaccessible areas for humans, such as deep oceans, space, nuclear accident sites, and rugged mountains [2]. However, in these scenarios, unknown and complex environments are often beyond the capabilities of a single robot [3,4], and they often require multi-robot systems to operate in concert [5]. Through simultaneous exploration and operation in multiple areas, multi-robot systems tend to have higher exploration efficiency and greater coverage than single robots in unknown environments [6]. In addition, their advantages in handling large amounts of data, adapting to complex tasks, and providing system redundancy make them more robust and reliable compared to single robots [7]. These advantages have led to the widespread application of multi-robot systems in industry [8], mapping [9], agriculture [10], security surveillance [11], and disaster monitoring [12]. Although the above advances have significantly improved the task execution capabilities of multi-robot systems, the real-time coordination of multi-objective optimization for area coverage, obstacle avoidance safety, and motion energy consumption still poses a key challenge when autonomously exploring unknown dynamic environments. Existing studies have mainly implemented path planning through nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) with fixed weights [13,14]. However, in scenarios such as the sudden change in obstacle density or dynamic update of target points, the controller often suffers from performance degradation due to the solidification of target weights. How to construct an environment-adaptive decision-making mechanism becomes a core challenge for improving the robustness of multi-robot systems [15].

To address the core challenge of multi-objective co-optimization in the multi-robot collaborative exploration of unknown environments, academics are advancing theoretical innovations along two paths of spatial intelligent allocation and semantic control fusion. On the one hand, the spatial partitioning algorithm based on the dynamic Voronoi diagram provides an efficient task allocation mechanism for multi-robot cooperative exploration through geometric exclusivity constraints [15,16]. The algorithm optimizes region coverage through distributed computation and significantly reduces the risk of inter-robot trajectory conflict [17]. However, the existing Voronoi methods still face an inherent contradiction between coverage efficiency and obstacle avoidance response in real-time dynamic scenes. The static weight evaluation function is difficult to adapt to the sudden change characteristics of complex environments, resulting in a system that is prone to fall into a local optimum or trigger motion oscillations in obstacle-intensive regions. On the other hand, the breakthrough of large language models (LLMs) in environmental semantic parsing and multimodal rule reasoning provides a new paradigm for establishing nonlinear mapping between environmental features and control parameters [18]. Its natural language interface enables tje dynamic mapping of perceptual features such as obstacle density and target distance to the cost function weight space of model predictive control (MPC). Nevertheless, there are still technical barriers to the heterogeneous fusion between the discrete semantic output of LLM and the continuous optimization process of MPC—the former relies on symbolic logic reasoning and the latter needs to satisfy the differential smoothness constraints of real-time numerical computation. How to seamlessly integrate the discrete semantic output of LLM with the continuous optimization process of traditional controllers is still a technical bottleneck that needs to be solved.

To address the above challenges, this article proposes a collaborative exploration framework based on dynamic Voronoi partitioning with large language model-enhanced nonlinear model predictive control (LLM-NMPC) to address the challenges of multi-objective co-optimization and cross-modal decision fusion in multi-robot collaborative exploration of unknown environments. The research aims to break through the adaptability limitations of traditional fixed-weight strategies in mutating scenarios and address the heterogeneous coupling of semantic reasoning systems and continuous control processes. By constructing a closed-loop architecture of “high-level semantic decision-making and low-level motion control”, the study innovatively couples spatial intelligent allocation and semantic parameter regulation at a hierarchical level: At the spatial allocation level, the dynamic Voronoi algorithm implements partitioning based on real-time environment characteristics to ensure balanced allocation of tasks to the multi-robot system; at the control parameter level, LLM-NMPC is used to control the multi-robot system through the LLM-NMPC. At the control parameter level, LLM-NMPC dynamically reconfigures the control parameters through a semantic mapping mechanism to make the exploration strategy adaptive to changes in environmental complexity. This bimodal synergistic mechanism combines the advantages of the geometric constraint approach with the context-awareness capability of the semantic reasoning system to form an environment-responsive decision-making paradigm. The framework provides a solution that combines both high-level decision optimization and bottom-level motion control for unknown environment exploration tasks.

The contributions of this article are as follows:

- LLM-NMPC Cross-Modal Framework: Novel embedding of large language models (LLMs) into the NMPC architecture enables adaptive adjustment of cost function weights based on environmental semantics, effectively resolving the parameter rigidity problem in dynamic obstacle scenarios.

- Enhanced Dynamic Voronoi Partitioning: Introduction of parameter constraints, event-triggered reconfiguration, and region inheritance protocols significantly improves task allocation robustness and exploration continuity for multi-robot systems in dynamic environments (including communication failures).

- Systematic Experimental Validation: Comprehensive multi-scenario benchmarking on heterogeneous platforms against DDPG and fixed-weight NMPC demonstrates the framework’s superior performance in exploration efficiency and obstacle avoidance success rate.

2. The Proposed Method

2.1. Overall Framework Description

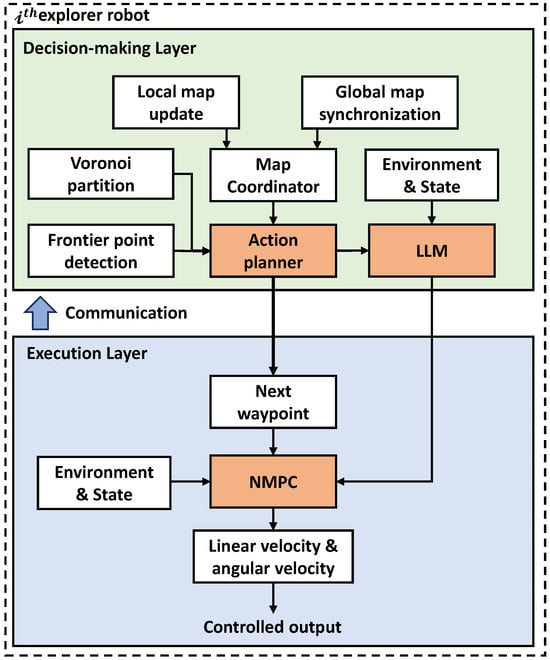

Figure 1 illustrates the collaborative navigation framework based on dynamic Voronoi partitioning and large language model-enhanced nonlinear model predictive control (LLM-NMPC), comprising a decision-making layer and an execution layer. As shown in Figure 1, the objective at the decision-making layer is to determine the most optimal location for each robot to explore within the current environment. Each robot continuously senses its surroundings through its own sensors, constructing and updating its local map. This map incorporates newly detected obstacles, vacant areas, and unknown regions near the robot. Global map synchronization is achieved via a communication module, where all robots share their local maps with a map coordinator. This coordinator fuses the information to form a unified, globally consistent environment and state map. This global map serves as the foundation for all decision-making. The action planner serves as the core logic unit within the decision layer. It synthesizes information from Voronoi partitioning and frontier point detection, enabling each robot to identify its own territory and determine which points warrant exploration. Within its designated area, it preliminarily screens candidate target points. The action planner constructs the current state—including obstacle density, robot position, target point distances, etc.—into a natural language prompt sent to the LLM. Leveraging its embedded expert knowledge and semantic reasoning capabilities, the LLM evaluates the current situation and outputs a high-level strategy. This strategy directly manifests as adjustment recommendations for the NMPC controller’s weight parameters, thereby endowing decision-making with a semantic understanding of complex environments. At the execution layer, the NMPC serves as the core controller. It receives the next waypoint from the decision layer while simultaneously acquiring real-time environment and state information. When solving constrained optimization problems, its cost function balances multiple objectives. The weights assigned to each objective within this cost function are dynamically adjusted by the LLM in the decision layer, enabling adaptive control. Ultimately, the underlying robot chassis can directly execute the control outputs—linear velocity and angular velocity.

Figure 1.

The hierarchical control structure includes decision and execution layers, as well as state-monitoring closed-loop feedback.

In this article, we innovatively designed an obstacle density field quantization model based on LiDAR point cloud data and used the kernel density estimation method to map the local obstacle distribution characteristics into a continuously differentiable obstacle density index. This index is encoded as a structured semantic feature vector, together with parameters such as robot positional state and target distance deviation. Subsequently, the feature vector is converted into semantic cues that conform to natural language logic, which drives the LLM to generate dynamic weight adjustment commands based on a preset expert rule base. After Lipschitz continuity check and boundary truncation at the security constraint layer, the instructions are injected into the cost function reconstruction module of NMPC in real time so that the system automatically improves the obstacle avoidance weights in dense obstacle areas, and at the same time, it strengthens the path tracking weights in the open environments to guarantee heading accuracy, thus breaking through the limitations of the traditional fixed-weight strategy in dynamic scenarios. In addition, by introducing the rolling time-domain prediction mechanism and the closed-loop error compensation strategy, the NMPC controller continuously transforms the discrete semantic decisions of the LLM output into smooth motion trajectories, which significantly shortens the control cycle and improves the adaptability and robustness of the multi-robot system.

2.2. Dynamic Voronoi Partitioning for Multi-Robot Task Assignment

In a multi-robot cooperative exploration task, a dynamic Voronoi partition-based task assignment mechanism effectively avoids repeated exploration and improves the overall efficiency by dividing the robots’ work areas in real time. The core of this mechanism is to dynamically partition the exploration area into several Voronoi cells, each corresponding to a robot.

2.2.1. Dynamic Voronoi Partition Modeling and Frontier Point Selection

Let the unknown environment Q be a two-dimensional convex polygonal space, the set of robots is , and the robot positions are . Define the dynamic Voronoi cell as follows:

where is the current position of robot , and denotes the set of its neighboring robots. This definition ensures that any point q within each Voronoi cell has the shortest distance to , thus naturally forming an exclusive exploration region for the robots. The dynamic adjustment of the Voronoi boundaries relies on the local communication between the robots, and it only needs to share the neighbor position information to achieve distributed computation and satisfy real-time requirements.

The robots exchange position information through the communication range to ensure the accuracy of the neighbor set . The sensing range determines the generation area of the frontier point , which needs to satisfy to ensure the timeliness of information synchronization. For the frontier point selection problem, we combine the distance cost and path cost to establish a multi-objective optimization function:

where is the Euclidean distance from to , is the backtracking distance from to the initial information node, and the weighting parameter regulates the exploration strategy: breadth-prioritized exploration is performed when , and depth-prioritized exploration is performed when .

Minimize by solving

The robot selects the optimal frontier point within its Voronoi cell for the local optimization of task assignment.

2.2.2. Dynamic Update Mechanism

After the multi-objective optimization function determines the local optimal objective of each robot, a dynamic response mechanism needs to be established to cope with the change in system topology.

Parameter Constraints

First of all, we need to establish a cooperative parameter constraint system using the sensor sensing radius to determine the single-machine information acquisition ability and communication radius to ensure the integrity of domain information; we also need to determine the minimum safety distance to prevent the robot from collision. In particular, the sensor sensing radius indicates that a single scan of the robot can detect the environment within the maximum radius, constituting a circular sensing domain:

This ensures that , where is the maximum diagonal distance from the environment, and N is the number of robots. This inequality is derived from the geometric coverage theory and ensures that the concatenation of the perception domains of each robot provides complete coverage of the environment. The coefficient 1.2 is derived by simulation optimization, which balances the trade-off between sensing capability and energy consumption.

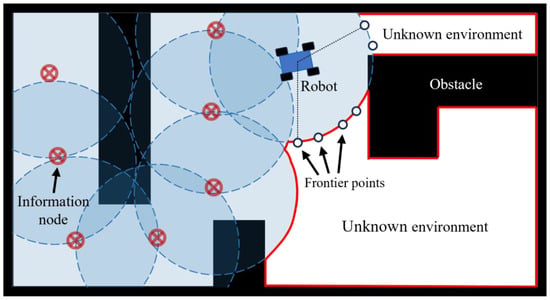

The communication radius is strictly required to ensure that the robots must be within the communication range when the sensing domains overlap (as shown in Figure 2). At the same time, if the distance between two robots is , their perception domains must overlap , proving that there is double coverage in the region. In addition, a certain safety margin, e.g., , is needed to compensate for the actual factors in the real environment, such as the attenuation of wireless signals by the environment, the robot’s localization error, and the temporary blockage of dynamic obstacles.

Figure 2.

This is a single robot exploring the location environment. Information nodes are marked by red notations, and the perceived range is indicated by blue dashed circles. Some newly generated frontier points are marked by small black circles indicating the next possible path points. The uncovered white area is the unknown environment.

In order to maintain the safety of robot physical interaction, collision avoidance needs to be realized by constructing a repulsive potential field function using the minimum safe distance :

where is a virtual potential energy (unitless) designed as a penalty term within the optimization framework. While analogous to a physical energy in its formulation, its primary function is to generate a repulsive effect. The corresponding virtual repulsive force is then incorporated into the system’s dynamics, influencing the control inputs. The stiffness coefficient k (also unitless) determines the strength of this repulsive response.

When the distance between the two robots is , the potential energy derivative increases drastically, resulting in a strong repulsive acceleration. The value of is determined by a combination of the physical dimensions of the robot and braking performance:

where is the maximum motion velocity of the robot, is the maximum braking acceleration of the robot, and is the integrated sensor system error.

Trigger Condition

The setting of the position update threshold follows the quantization control theory, the essence of which is to construct a discrete event triggering mechanism in the state space . When and only when the maximum displacement of the robot population is satisfied,

the system triggers the Voronoi topology reconstruction. This threshold satisfies with respect to sensor accuracy , which meets the error control criteria of the principle. After triggering, the topology update process can be modeled as a discrete dynamical system:

The convergence is proved as follows: define the global position vector ; then, the iterative equation can be expressed as , where J is the Jacobian matrix:

when the accuracy requirement is , the number of iterations coincides with the actual observed height.

This dynamic update mechanism forms a closed-loop regulation through a triple-constraint parameter: determines perception granularity, guarantees information connectivity, maintains physical security, and the three are dynamically balanced by the trigger threshold. In particular, the combination of the linear convergence property of the Jacobian iteration and the event-triggered mechanism enables the system to operate without global reconfiguration for of the work cycle, which significantly reduces the communication overhead.

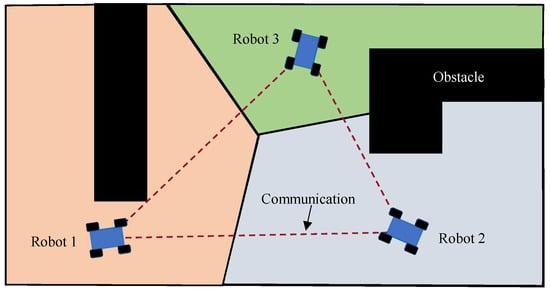

Figure 2 illustrates the exploration strategy of a single robot exploring an unknown environment, while Figure 3 shows the division of the exploration area by multiple robots exploring the same environment.

Figure 3.

Example of Voronoi division when using three robots to explore the same environment as in Figure 2. The work areas of all robots are represented by different colors. Note that the Voronoi partitioning is dynamically updated based on the different positions of the robots at different moments, which is a more robust method used to deal with unexpected disturbances in the environment.

2.2.3. Fault Tolerance Mechanism

In order to further improve the robustness of the system, a fault-tolerant protocol based on region inheritance is proposed for abnormal working conditions such as communication interruption or node failure. When the robot is detected to be offline, its original Voronoi region is dynamically reallocated:

where the communication radius and the motion velocity satisfy the constraint , ensuring that the area takeover is completed within the maximum response delay .

In practical implementation, this redistribution is achieved by having the neighboring robots of the failed robot immediately recalculate the Voronoi diagram among themselves, excluding . This calculation automatically absorbs the orphaned cells of into the existing adjacent cells, ensuring continuous coverage without requiring a central coordinator.

The above progressive design constructs a complete task allocation technology chain, and each link forms a closed-loop optimization system through strict mathematical model constraints and parameter coupling, which effectively solves the core problems of task conflict, high communication load, and insufficient dynamic environment adaptability in the collaborative exploration of multiple robots. Based on the Voronoi geometric coverage theory, the system divides the exclusive workspace to eliminate repetitive exploration and transforms the global topology reconstruction into progressive local iteration through the distributed event triggering mechanism, which significantly reduces the communication overhead. Meanwhile, combining the repulsive potential field constraints and the region inheritance protocol, a dual fault-tolerance mechanism is established at the physical obstacle avoidance layer and the task assignment layer, which not only ensures the safe cooperative motion among robots but also supports the seamless task takeover through the dynamic coupling of communication radius and motion speed when the node fails, and it builds a unified framework that takes into account both the computational efficiency and the robustness of engineering for cluster cooperation in the dynamic and uncertain environments.

2.3. Nonlinear Model Predictive Controller Design

The core of robot motion control lies in the establishment of an accurate dynamics model and a multi-objective optimization framework. Firstly, a system dynamics model is established to describe the kinematic behavior of the robot, and the current state and control inputs are used to predict the state at the next moment, which provides dynamic constraints for optimization, and the following discrete nonlinear system of robot kinematics is defined:

where the state variables, , contain the robot’s position coordinates , heading angle , linear velocity , and angular velocity at moment k. The control inputs, , correspond to linear acceleration , and angular acceleration , respectively. The discretization step defines the time interval of the prediction model, which lays the foundation for the subsequent multistep state prediction.

In order to realize high-precision trajectory tracking, the reference trajectory needs to have smoothness and continuity. Therefore, the three-times B-spline interpolation method is used to parameterize the trajectory and ensure the continuity of the trajectory:

reflecting a sequence of control points, , through linear interpolation. These points form the skeleton of the B-spline curve, determining the basic shape of the trajectory. The parameter n controls the granularity of the interpolation; a larger n results in denser control points and finer control over the trajectory shape:

where is the cubic B-spline basis function. It calculates the coordinate of a point on the trajectory for a given parameter u by taking a weighted sum of all control points . The key advantage of the cubic B-spline is its inherent guarantee of C2 continuity for the generated trajectory, meaning that the position, velocity, and acceleration are all continuous.

In robotic motion control, the second-order derivative continuity of a trajectory implies that its curvature changes continuously without abrupt acceleration changes. This is crucial for NMPC controllers, as it provides a smooth reference input, preventing control command jitter, increased energy loss, and even system instability caused by non-smooth reference trajectories.

Based on the above dynamics model and trajectory parameterization, the NMPC controller needs to optimize the multi-objective cost function in the prediction time domain. The total cost function is defined as follows:

It contains five sub-costs corresponding to different control objectives:

The trajectory-tracking cost is as follows:

where and are the weights to regulate the position and heading angle tracking accuracy, and is the reference trajectory point.

The control volume cost is as follows:

where and are the weights for suppressing linear acceleration and angular acceleration amplitude, which reduces the control energy consumption.

Controlling the cost of smoothness requires the following:

The weights and further ensure the continuity of motion by constraining the difference between neighboring control inputs.

The obstacle potential’s field cost is as follows:

The weights, , regulate the intensity of obstacle avoidance, M denotes the total number of obstacles in the environment, denotes the positional coordinates of the obstacle, and is the potential field range parameter that controls the decay rate of the Gaussian function.

The end goal attracts the following cost:

where is a weight that controls the rate of convergence of the terminals, prompting the robot to approach the target at the end of the prediction time domain. denotes the robot position coordinates at step N (end) of the prediction time domain.

By dynamically adjusting the above weighting parameters, the controller can realize a flexible trade-off between path tracking accuracy, energy consumption, smoothness, obstacle avoidance safety, and terminal convergence speed.

In this study, the weighting factors , , , , , and are determined through a two-stage tuning procedure. In the first stage, we select nominal values and admissible ranges based on control intuition and the physical properties of the robots: Larger values are assigned to and to prioritize tracking accuracy, whereas and are set to smaller values to penalize excessive accelerations and improve motion smoothness. The weights and are chosen to reflect the required safety margin to obstacles and the desired convergence speed in the wildfire monitoring task. These nominal values and ranges are refined offline in ROS–Gazebo simulations by sweeping each parameter within its interval and selecting combinations that achieve a satisfactory trade-off between tracking error, control effort, and collision avoidance performance. In the second stage, the nominal weights serve as prior values that are further adjusted online by the LLM module according to the perceived scene type, which leads to the time-varying weight trajectories.

In order to implement constraints to ensure that the robot’s motion is within physical feasibility and enforce safety rules for obstacle avoidance, we introduce a system of constraints to construct the set of hard constraints:

Specifically, it includes state constraints, control constraints, and safe distance constraints. Among them, the state constraints and have no restrictions on the robot’s position , which is actually constrained by the environment boundary, but to avoid angular entanglement, it will restrict the heading angle and limit the range of linear velocity V and angular velocity based on the robot’s physical mechanism; the control constraints limit linear acceleration a based on driving ability, and the steering response speed limits angular acceleration . The safe distance ensures that the minimum distance between the robot center and the obstacle meets the obstacle avoidance requirements.

The control problem has now been transformed into a nonlinear programming problem with constraints, which needs to be processed with the numerical optimization solver IPOPT to construct a finite-time domain optimal control problem.

The nonlinear programming problem with constraints defines the core objective of NMPC: minimizing the cost function (15) while satisfying the dynamics, state, control and obstacle avoidance constraints. Where is the sequence of states in the prediction time domain, and each contains the robot’s position, velocity, and orientation; is the sequence of control inputs in the prediction time domain, and each contains the acceleration and steering commands. Note that the variables x and u follow the constraints in (21).

However, solving optimization problems with constraints directly is numerically very difficult, especially when the number of constraints is large. For this reason, the augmented Lagrangian function is introduced to transform the problem into an unconstrained form by the following steps:

We define the following augmented Lagrangian function:

where the multiplier is the optimization variable used to ensure that the constraint is satisfied. All inequality constraints (21) are integrated as and relaxed by the multiplier and the penalty term .

The generalized Lagrangian function transforms the original problem into an unconstrained optimization problem, but its nonlinear nature makes it almost impossible to solve the analytical solution directly. Therefore, an iterative solution using the proposed Newton method is required.

The proposed Newton method significantly reduces the computational complexity by avoiding the direct computation of the second order derivatives by approximating the Hessian matrix:

Update the variable U, the multiplier , by the step size , and the gradient direction:

The Armijo line search ensures that each iteration step brings down the objective function.

The optimal control sequence is obtained through iterative optimization, since, in the NMPC framework, each optimization predicts the future N-step trajectory based on the current state , but the dynamic changes in the environment may cause the subsequent predictions to fail. Therefore, only the first step control quantity is actually executed:

However, the open-loop control quantity may cause the actual trajectory to deviate from the expected one due to model errors or external perturbations. For this reason, a closed-loop compensation strategy is introduced:

where K is a calming compensation term that is satisfied:

where regulates the position tracking error, and regulates the heading angle error.

The overall framework first predicts the future N-step state based on the current state and dynamics model and then solves the minimization problem of the multi-objective cost function to satisfy the dynamics, state, control, and safety constraints. It then executes the first optimal control quantities and enhances closed-loop stability through calming compensation, and finally, it re-predicts and plans the new sampling moments to adapt to environmental changes. This framework enables motion control in complex environments through mathematical modeling and parametric design.

2.4. Dynamic Weight Adjustment Mechanism of LLM in NMPC Controllers

We innovatively designed a deep collaborative framework integrating large language modeling (LLM) and nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC). The LLM component is implemented using the OpenAI GPT-4o API (chatgpt-4o-latest), with its temperature parameter set to 0.1 to maximize output consistency for our control tasks. This framework pioneers a new paradigm of adaptive high-level exploratory policy control based on semantic understanding in Algorithm 1. The system achieves intelligent decision-making and robust control in complex dynamic scenarios by building a semantic bridge from environment sensing to control optimization. Its core innovation is to utilize the contextual reasoning capability of LLM to map unstructured environmental information into dynamic weight parameters for nonlinear optimization problems, thus breaking through the limitations of fixed weights or rule-based adjustments in traditional control methods.

The system architecture adopts layered closed-loop control, and it constructs a full-link framework from perceptual semantic parsing to weight optimization control execution. The perception layer extracts the environment feature vector through raster map analysis, where the obstacle density quantifies the degree of environmental congestion and the nearest obstacle distance characterizes the urgency of obstacle avoidance. These features, together with the robot state , constitute the input space of the large language model, which generates weight vectors through a pre-trained semantic mapping function . This mapping process is realized through a structured cueing template , which encodes the robot position, motion state, goal location, and environmental features encoded as natural language commands, inducing the macro-language model to output weight parameters that meet the control requirements. The generated weight parameters directly influence the design of the optimization objective function (15) of NMPC. This dynamic weighting mechanism enables the system to adaptively adjust the optimization objective according to the scene semantics, e.g., significantly boosting to a preset upper limit in obstacle-intensive regions and prioritizing when approaching the target.

To ensure the robustness of the system, a two-layer decision fusion mechanism is designed. When the big language model fails to work due to functional anomalies, the system automatically switches to the rule-based reasoning mode , which selects preset weights according to the threshold conditions: Open environments focus on path tracking, narrow channel spaces strengthen obstacle avoidance, and endpoint accuracy is improved when the target is close to the target. This hybrid architecture retains the scene generalization capability of the large language model, while ensuring base stability through symbolic rules.

| Algorithm 1 LLM-NMPC for Multi-Robot Navigation |

| Require: LLM API, Robot states , Goal g, Obstacles , Kinematic model K |

| Ensure: Control commands and trajectories for each robot |

| 1: Initialize: , N, |

| 2: repeat |

| 3: for each robot i do |

| 4: Collect current states from ROS nodes |

| 5: |

| 6: |

| 7: if is valid then |

| 8: |

| 9: else |

| 10: Fill missing weights from |

| 11: end if |

| 12: |

| 13: for to do |

| 14: |

| 15: |

| 16: Apply constraints: , |

| 17: end for |

| 18: |

| 19: Apply control: |

| 20: return |

| 21: end for |

| 22: until There is no information update for each status information node of each robot |

At the control execution layer, the system adopts a hierarchical fault-tolerant strategy to cope with extreme situations. When the NMPC solver fails to converge due to nonlinear constraints or initial value problems, the safe fallback mechanism generates the degradation control law , where the linear velocity is dynamically adjusted according to the heading deviation , and the angular velocity implements proportional control. This mechanism ensures the basic mobility function while buying buffer time for system recovery.

The method can be extended to multi-robot cooperative scenarios with distributed optimization through independent weight mapping functions. The state vector of each robot contains its exclusive position and velocity and local environment features, and the weight adjustment process operates independently under namespace isolation to avoid parameter coupling in group decision-making.

Compared with the traditional nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC), the framework is innovative in three aspects: First, natural language processing is introduced into the control parameter optimization, and an explicit mapping between semantic understanding and mathematical optimization is established; second, the scenario adaptive smooth transition is achieved through hybrid neural symbolic architecture, which maintains basic performance when the language model fails; third, the design of multi-layer security boundaries is carried out, including weighting range constraints, solution failure detection, and degradation control over activation mechanisms.

3. Results and Illustration

3.1. Experimental Settings

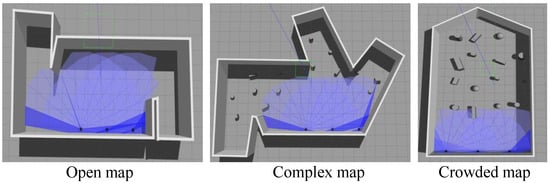

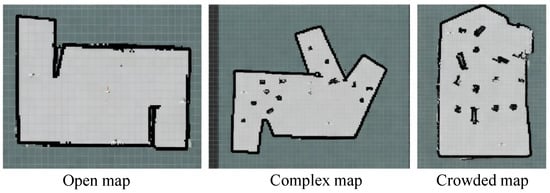

ROS is widely used in robotics software development. Its modular design, standardized protocols, and mature ecosystem of tools solve the underlying challenges of communication, collaboration, and development in multi-robot systems, and it becomes the technical foundation for building complex multi-machine systems and provides higher security, real-time, and cross-platform capabilities. With the popularization of ROS, Gazebo has become a mainstream robot simulation platform. In this study, ROS Gazebo (Ubuntu 18.04 LTS, ROS 1: Melodic Morenia, Gazebo 9) is adopted as the simulation environment and validated using the Turtlebot3 robot. In order to evaluate the proposed method, a variety of scenarios with different obstacle density distributions are designed in Gazebo: as shown in Figure 4, an open map with no obstacles, a crowded map with a high density of obstacles, and a complex map with sudden changes in obstacle density. Figure 5 shows the Turtlebot3 robot model loaded in Gazebo.

Figure 4.

Different simulated environments.

Figure 5.

Turtlebot3 robot in Gazebo.

In an open scene without obstacles, the basic navigation performance is verified, and the task allocation efficiency and map building capability are evaluated; in a high-density obstacle congested scene, the obstacle avoidance limit performance of the control algorithm is tested to ensure that there are no collisions and motion stagnation in the exploration process. In a complex scene with sudden changes in obstacle density, the dynamic adaptability of the method is evaluated: When the LiDAR detects low obstacle densities, the system should adaptively increase the trajectory smoothing weights and reduce the obstacle avoidance weights; conversely, in high-obstacle-density regions, the system should enhance the obstacle avoidance weights and reduce the trajectory smoothing priority.

3.2. Comparison with Other Algorithms and Evaluation Indicators

In the comparison experiments, the proposed LLM-enhanced NMPC method based on Voronoi partitioning is compared with the deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm (DDPG) and fixed-weight nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC), respectively. The evaluation metrics cover exploration efficiency, safety, and robustness: Exploration efficiency is evaluated by the exploration completion time (s) and the number of times the specified exploration rate is achieved; safety is measured by the number of collisions with obstacles, successful obstacle avoidance rates (%), and the number of robot jams; robustness is evaluated by the average exploration completion rate (%) of unsuccessful trials.

3.3. Unknown Environment Exploration

The robots do not know the particular environment beforehand. Subsequently, we employ a multi-robot system to model the unknown environment, constructed by visualizing the robot’s trajectories and maps through Rviz v1.13.21. Figure 6 shows an example of the robot exploration of an unknown domain with different obstacle densities. As shown, the robots can successfully avoid obstacles and construct a relatively comprehensive map of the unknown environment.

Figure 6.

Building maps for different simulated environments in Figure 4.

3.4. Analysis of Experimental Results

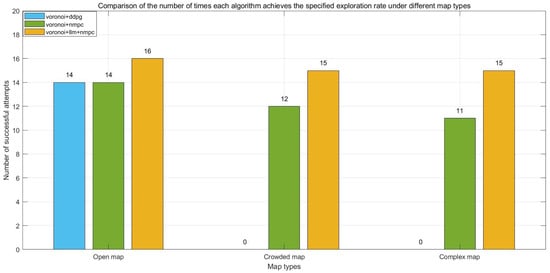

3.4.1. Mission Efficiency Advantages

As shown in Figure 7, in 20 repeated experiments and in open scenarios, the number of times the proposed method reaches 99% of the exploration rate (16 times) is 10% higher than that of the fixed-weight NMPC (14 times), which is significantly better than that of DDPG (12 times). In congested scenarios, the success rate of the proposed method (15 times) is 25% higher than that of the fixed-weight NMPC. In complex scenarios, the advantage of the proposed method over fixed-weight NMPC is further enlarged, which verifies the dynamic environment adaptability of LLM-NMPC.

Figure 7.

The number of times each algorithm achieves the specified exploration rate.

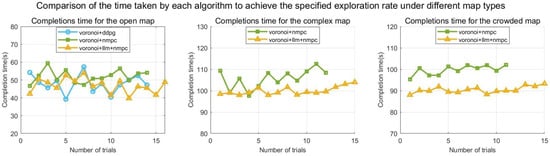

Figure 8 further quantifies time efficiency: In complex scenarios, the average completion time of the proposed method is significantly lower than that of the fixed-weight NMPC, which is due to the semantic weight adjustment mechanism of the LLM—when the sensor detects a sudden change in the density of the obstacles ( rises), the system automatically raises (19) to the preset upper limit, effectively avoiding path oscillations.

Figure 8.

The time taken by each algorithm to achieve the specified exploration rate.

3.4.2. Safety Performance Verification

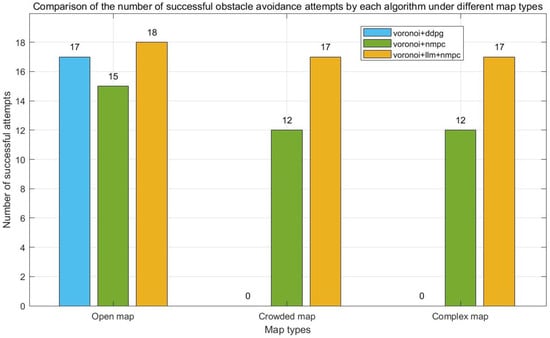

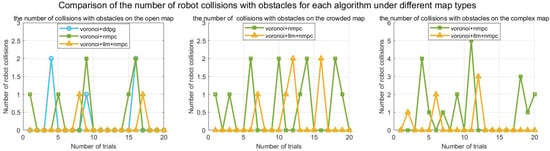

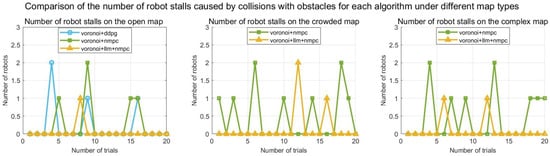

Figure 9 and Figure 10 verify obstacle avoidance and collision performance: In complex scenarios, the proposed method achieves an average number of successful obstacle avoidance of 17 times/trial (Figure 9), and an average number of collisions of only 0.8 times/trial (Figure 10), which is 81% lower than that of the fixed-weighted NMPC (with an average number of collisions of 4.2 times/trial). This advantage stems from the fact that LLM-NMPC dynamically adjusts the potential field cost weights by resolving the distance to the nearest obstacle in real time —when the distance of the nearest obstacle is less than 0.3 m, is raised from 0.4 to the preset upper limit (19), which triggers the strong obstacle avoidance response of NMPC. Figure 11 verifies the fault robustness: The frequency of severe jamming during exploration is significantly higher for the traditional methods, DDPG and fixed-weight NMPC, than for LLM-NMPC. Although the neighboring robots can automatically take over the offline node area when communication is interrupted, the efficiency and effectiveness of a single exploration will be reduced, so a reduction in the number of jamming times is crucial to improve the system’s fault robustness.

Figure 9.

The number of successful obstacle avoidance attempts by each algorithm.

Figure 10.

The number of robot collisions with obstacles for each algorithm.

Figure 11.

The number of robot stalls caused by collisions with obstacles for each algorithm.

The safety performance of the proposed method is quantitatively evaluated and compared against the baseline algorithms in terms of obstacle avoidance success, collision incidents, and system robustness. The key quantitative results across all test scenarios are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of safety performance metrics (average per trial).

3.4.3. Robustness

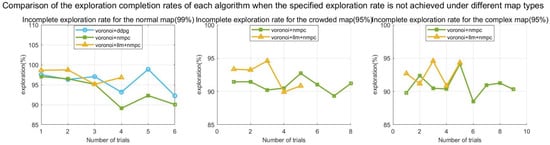

Figure 12 counts the exploration completion of the unmet trials. Under the challenge of dynamic unknown environments, the proposed method demonstrates excellent adaptability: As shown in Figure 12, the average exploration completion of its unattained trials reaches 94.7%, which is significantly better than that of the fixed-weight NMPC and DDPG. This advantage stems from the synergistic effect of the dual fault-tolerance mechanism: When the robot’s displacement deviation exceeds a threshold due to sudden changes in obstacle density, the LLM carries out a high-level decision to eliminate the coverage of blind zones; meanwhile, the LLM response timeout triggered by a communication interruption will activate the degraded control strategy , which maintains the base exploration capability via the safe command . This result verifies the strong robustness of the cross-modal fusion mechanism of geometric constraints and semantic control under extreme working conditions, such as sudden environmental changes and communication interruptions.

Figure 12.

The exploration completion rates of each algorithm when the specified exploration rate is not achieved.

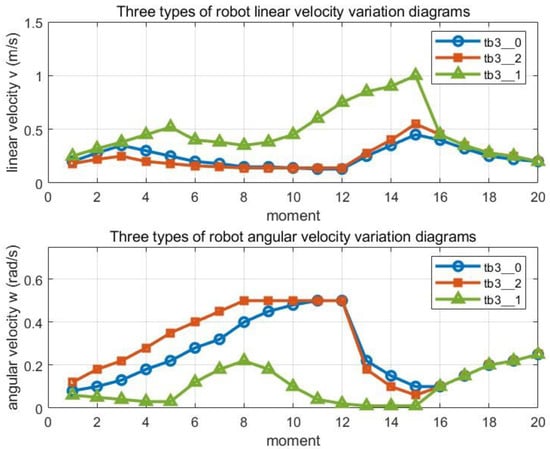

3.5. Qualitative Simulation Experiment

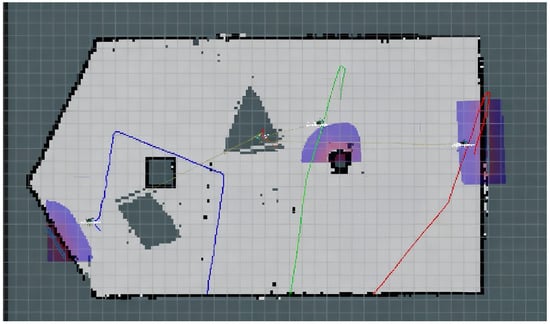

In this subsection, we visualize the motion trajectories of the three robots under the proposed method in Figure 13. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 show the values of the six weights for each robot at 10 sampled moments in its trajectory. The results show that the weights in the cost function (15) change dynamically in real time, making the path planning smoother and more efficient. The three robots always maintain a safe spacing when traveling, choose a better path in the obstacle area, and effectively avoid obstacles and prevent collisions. Figure 14 visualizes the changes in linear and angular velocities of the robots. LLM balances obstacle avoidance performance, path smoothness, and target tracking accuracy by adjusting the weights of NMPC in real time, ensuring that the robots efficiently and stably complete the exploration tasks in complex dynamic environments and verifying its superior performance.

Figure 13.

The motion trajectories of the three robots under the proposed method.

Table 2.

The 6 weight values for the robot in the blue trajectory (Figure 13) at the 10 sampled moments of the trajectory show that the weights are constantly changing.

Table 3.

The 6 weight values for the robot in the red trajectory (Figure 13) at the 10 sampled moments of the trajectory show that the weights are constantly changing.

Table 4.

The 6 weight values for the robot in the green trajectory (Figure 13) at the 10 sampled moments of the trajectory show that the weights are constantly changing.

Figure 14.

Variations in the linear and angular velocities of three robots.

4. Discussion

Dynamic Voronoi partitioning-based task assignment and autonomous navigation fusing large language models are the supporting research published in this study, and in this section, we present a comprehensive survey of existing techniques and review their development.

4.1. Robot Navigation Based on Voronoi Diagrams

The technological development in the field of environment sensing and autonomous navigation continues to drive the innovation of the application of Voronoi partitioning theory. In early research, Warum et al. [19] introduced online Voronoi partitioning into multi-robot systems for the first time, and they realized the balanced deployment of robots through the grid division of environment space, which significantly reduced the probability of task conflict. However, this method has mechanical defects at the level of dynamic environment modeling. Alitappeh et al. [20] constructed a multi-objective deployment model integrating spatial optimization and positional decision-making on this basis, and although the deployment efficiency was improved by , the dynamic response mechanism of the environment has not yet broken through the key performance threshold.

In the field of safe navigation, the probabilistic safe buffer model [21] effectively copes with the problem of localization bias through a distributed computing architecture, but its computational time-consuming and real-time demands result in a significant contradiction. For the obstacle distribution continuity problem, the geodesic fusion partitioning method [22] successfully eliminates the coverage blindness of the traditional method, but its dynamic obstacle processing module still has a failure probability of about in real-world scenario requirements. The geometric path planner [23] improves navigation efficiency by , but its environmental adaptability metrics are still lower than the dynamic scene requirements.

In terms of cutting-edge research, the autonomous collision avoidance model [24] achieves communication-free coordination in of the scenarios, but the coordination success rate drops to in high-density dynamic environments; the multimode exploration strategy [25] reduces path redundancy by , but these breakthroughs have not yet completely solved the core technical difficulties in dynamic unknown environments.

Nevertheless, the existing Voronoi framework generally adopts a fixed evaluation function to deal with the contradictory relationship between obstacle avoidance and trajectory smoothing, and it fails to establish an adaptive adjustment mechanism of weights in dynamic scenarios. In particular, there is a theoretical gap in the parameter differentiation between dense obstacle areas and open areas [26]. In this article, as a breakthrough, we introduce a large language model-enhanced nonlinear model predictive control architecture, and we effectively solve the limitations of the traditional Voronoi method in complex dynamic exploration environments by constructing a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism.

4.2. Navigation with LLM

The integration of a large language model (LLM) in autonomous navigation systems enhances cross-modal data integration and semantic understanding, significantly improving environmental interaction capabilities. The FLAME architecture [27] employs a triple optimization mechanism and an automatic data generation strategy, improving the Touchdown test’s performance by 7.3% while solving urban navigation challenges. The DDN system [28] achieves goal-driven localization via object feature modeling, while the LIM2N model [29] optimizes human–machine collaboration efficiency using language-sketch multi-source inputs. Bai et al. [30] demonstrates that GPT-4 enhances short-term path decision accuracy through task decomposition and environmental feedback.

Recent advances in semantic-driven navigation technology face limitations in dynamic response mechanisms: excessive semantic reliance introduces susceptibility to environmental noise, causing average decision delays of 1.2 s during microenvironment changes that compromise navigation stability. Addressing this, VLM-GroNav [31] fuses visual language models with terrain awareness for real-time trajectory planning, while the zero-shot navigation agent [32] achieves 83% success in multilevel task planning. The LM-Nav framework [33] integrates GPT-3 and CLIP modules for multimodal target navigation.

For spatial cognition enhancement, the STMR technique [34] enhances complex task reasoning through the semantic mapping of landmarks. The VLFM architecture [35] integrates deep observation and value maps to maintain performance leadership in multiple benchmark tests. The novel cross-dimensional characterization module [36] improves obstacle adaptation to 91% through 2D/3D information fusion. Zhou et al. [37] points out that real-time regulation and cross-domain migration capability for dynamic environments are the core directions for future breakthroughs.

Aiming at the dynamic response delay and environmental noise sensitivity problems of semantically driven technologies, especially the rigid constraints of the traditional parameter regulation framework in dynamic obstacle scenarios (average decision delay of 1.2 s), this article proposes a cross-modal dynamic coupling control paradigm. This paradigm integrates the large language model (LLM) and the nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC), and it constructs a closed-loop architecture of “high-level decision-making–low-level control”: the LLM parses the semantic features of the environment in real time, and the NMPC adjusts the weight matrix of the cost function online through the dynamic mapping mechanism from the feature space to the parameter space. This mechanism breaks through the traditional fixed-weight model and effectively solves the parameter rigidity problem in dynamic obstacle scenarios while retaining the advantage of semantic cognition so as to improve the navigation accuracy and obstacle avoidance response capability of the system.

4.3. Practical Limitations and Computational Constraints

Although the proposed LLM–NMPC framework shows clear advantages in terms of exploration efficiency, safety, and robustness in the simulation scenarios, several practical limitations and computational constraints remain. First, the controller is built on a simplified kinematic model and assumes accurate state estimation. In real wildfire monitoring missions, unmodeled dynamics, such as wheel slip on rough terrain, strong winds, or rapidly changing fire fronts, as well as sensor noise and localization drift, may degrade the control performance and lead to suboptimal or even unsafe behavior. Additional robust or adaptive mechanisms are therefore required before deployment in complex outdoor environments.

Second, the combination of nonlinear model predictive control and LLM-based weight adjustment introduces non-negligible computational overhead. In the experiments of this article, the system runs in real time on a workstation-class computer with a small team of robots and a moderate prediction horizon. However, on resource-constrained embedded platforms, or when the number of robots and the complexity of the environment further increase, the optimization and inference time may exceed strict real-time requirements, resulting in longer planning cycles and degraded navigation performance. In such cases, model reduction, shorter horizons, or more efficient numerical solvers and compressed language models would be needed.

Third, the current design of the LLM-driven weight adaptation relies on manually designed prompts and a limited set of representative scene types. When the environment differs significantly from these typical patterns, the semantic interpretation of the scene and the resulting weight adjustment may no longer be optimal, and simpler fixed-parameter controllers or specialized planners may perform better. Moreover, all evaluations in this work are conducted in simulations; transferring the framework to real multi-robot wildfire monitoring and data collection will require addressing communication delays, scalability to larger robot teams, and hardware failures in a systematic way. These limitations point to important directions for future work, including the integration of robust and learning-based model adaptation, the co-design of lightweight optimization and language modules for on-board deployment, and the collection of real-world data to refine the semantic-to-parameter mapping under more diverse and challenging conditions.

5. Conclusions

This article successfully developed an innovative architecture integrating dynamic Voronoi partitioning with large language model-augmented nonlinear model predictive control (LLM-NMPC), effectively addressing the core challenge of collaborative exploration in multi-robot systems within dynamically unknown environments. Through a hierarchical closed-loop design, this framework achieves the seamless integration of semantic decision-making and motion control: An improved dynamic Voronoi algorithm combines event triggering with zone inheritance mechanisms, significantly enhancing the robustness of dynamic task allocation and the continuity of zone coverage. Simultaneously, LLM-NMPC establishes an adaptive mapping from environmental features to control parameters by embedding the semantic reasoning capabilities of large language models into the nonlinear optimization process, overcoming the parameter rigidity issue in dynamic obstacle scenarios faced by traditional methods. Experimental validation demonstrates that, in complex scenarios simulating sudden changes in obstacle density during fire propagation, this approach significantly outperforms traditional deep reinforcement learning and fixed-weight NMPC methods on key metrics such as regional exploration efficiency and obstacle avoidance success rate. This research provides a comprehensive solution for autonomous monitoring tasks in complex dynamic environments by integrating advanced semantic cognition with real-time optimization control, advancing the deep integration of artificial intelligence and automatic control theory in critical environmental applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S.; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, J.S.; resources, J.S.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NMPC | Nonlinear Model Predictive Control |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| B-spline | Basis-Spline |

| IPOPT | Interior Point OPTimize |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

References

- Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Liang, H.; Li, P.; Wang, T.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, C. Current trends in the development of intelligent unmanned autonomous systems. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2017, 18, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragança, S.; Costa, E.; Castellucci, I.; Arezes, P.M. A brief overview of the use of collaborative robots in industry 4.0: Human role and safety. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Queralta, J.P.; Taipalmaa, J.; Pullinen, B.C.; Sarker, V.K.; Gia, T.N.; Tenhunen, H.; Gabbouj, M.; Raitoharju, J.; Westerlund, T. Collaborative multi-robot systems for search and rescue: Coordination and perception. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, J. Hierarchical control framework for path planning of mobile robots in dynamic environments through global guidance and reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, N.; Clegg, A.; Truong, J.; Undersander, E.; Yang, T.Y.; Arnaud, S.; Ha, S.; Batra, D.; Rai, A. Asc: Adaptive skill coordination for robotic mobile manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 9, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, W.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.; Gao, F.; Jian, Z.; et al. Multi-Robot System for Cooperative Exploration in Unknown Environments: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.07278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, R.; Albu-Schäffer, A.; Bicchi, A.; Bischoff, R.; Chatila, R.; De Luca, A.; De Santis, A.; Giralt, G.; Guiochet, J.; Hirzinger, G.; et al. Safe and dependable physical human-robot interaction in anthropic domains: State of the art and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- An, X.; Wu, C.; Lin, Y.; Lin, M.; Yoshinaga, T.; Ji, Y. Multi-robot systems and cooperative object transport: Communications, platforms, and challenges. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2023, 4, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, P.Y.; Beltrame, G. Swarm-slam: Sparse decentralized collaborative simultaneous localization and mapping framework for multi-robot systems. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 9, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, J.; Fan, L.; Zhou, Q.; Yin, K.; Wang, J.; Song, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z. Review of wheeled mobile robots’ navigation problems and application prospects in agriculture. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 49248–49268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Bhowmick, P.; Lanzon, A. Distributed adaptive time-varying group formation tracking for multiagent systems with multiple leaders on directed graphs. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2019, 7, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Lei, Y.; Zhong, F. Bayesian reinforcement learning for multi-robot decentralized patrolling in uncertain environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 11691–11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Meng, Y.; Liu, L.; Gu, Q.; Huang, J.; Liang, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Chang, X.; Gan, X. Path tracking for car-like robots based on neural networks with NMPC as learning samples. Electronics 2022, 11, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.; Burri, M.; Siegwart, R. Linear vs nonlinear mpc for trajectory tracking applied to rotary wing micro aerial vehicles. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 3463–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, J. Multirobot unknown environment exploration and obstacle avoidance based on a Voronoi diagram and reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Son, H.I. A voronoi diagram-based workspace partition for weak cooperation of multi-robot system in orchard. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 20676–20686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Niu, H.; Carrasco, J.; Lennox, B.; Arvin, F. Voronoi-based multi-robot autonomous exploration in unknown environments via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 14413–14423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Yang, G.; Yang, L.; Chi, H.; Yang, L. Applications of large language models and multimodal large models in autonomous driving: A comprehensive review. Drones 2025, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, K.M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Coordinated multi-robot exploration using a segmentation of the environment. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1160–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Alitappeh, R.J.; Jeddisaravi, K.; Guimarães, F.G. Multi-objective multi-robot deployment in a dynamic environment. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 6481–6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Alonso-Mora, J. B-uavc: Buffered uncertainty-aware voronoi cells for probabilistic multi-robot collision avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Multi-Robot and Multi-Agent Systems (MRS), New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 22–23 August 2019; pp. 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.G.; Guruprasad, K. GM-VPC: An algorithm for multi-robot coverage of known spaces using generalized Voronoi partition. Robotica 2020, 38, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, S.; Sarras, I.; Eudes, A.; Marzat, J. Voronoi-based geometric distributed fleet control of a multi-robot system. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Shenzhen, China, 13–15 December 2020; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Brito, B.; Alonso-Mora, J. Decentralized probabilistic multi-robot collision avoidance using buffered uncertainty-aware Voronoi cells. Auton. Robot. 2022, 46, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Luo, M.; Zhou, B. Time-Efficient autonomous Exploration in unknown environment by Multi-Representation strategy. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 28427–28440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayawli, B.B.K.; Mei, X.; Shen, M.; Appiah, A.Y.; Kyeremeh, F. Mobile robot path planning in dynamic environment using voronoi diagram and computation geometry technique. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86026–86040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Cai, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, C. Boosting Efficient Reinforcement Learning for Vision-and-Language Navigation With Open-Sourced LLM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 10, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, A.G.H.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Dong, H. Find what you want: Learning demand-conditioned object attribute space for demand-driven navigation. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 16353–16366. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Cho, Y.; Kim, M.; Jung, J.; Joe, M.; Been, P.Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; PARK, W.; et al. Integrating Visual and Linguistic Instructions for Context-Aware Navigation Agents. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on Open-World Agents, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Taylor, C.N. Future uncertainty-based control for relative navigation in GPS-denied environments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 3491–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnoor, M.; Weerakoon, K.; Seneviratne, G.; Xian, R.; Guan, T.; Jaffar, M.K.M.; Rajagopal, V.; Manocha, D. Robot Navigation Using Physically Grounded Vision-Language Models in Outdoor Environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.20445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Zhang, Y. Achieving multitasking robots in multi-robot tasks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 8948–8954. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, D.; Osiński, B.; Levine, S. Lm-nav: Robotic navigation with large pre-trained models of language, vision, and action. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; pp. 492–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pears, N.; Liang, B. Ground plane segmentation for mobile robot visual navigation. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Expanding the Societal Role of Robotics in the the Next Millennium (Cat. No. 01CH37180), Maui, HI, USA, 29 October–3 November 2001; Volume 3, pp. 1513–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, B.; Yaw, S.; Middleton, R. CostMAP: An open-source software package for developing cost surfaces using a multi-scale search kernel. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, B. Learning Cross Dimension Scene Representation for Interactive Navigation Agents in Obstacle-Cluttered Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6264–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hong, Y.; Wu, Q. Navgpt: Explicit reasoning in vision-and-language navigation with large language models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 7641–7649. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).