Abstract

Türkiye’s forest governance exhibits a persistent policy–implementation gap rooted in a governance paradox: while the Ecosystem-Based Functional Planning (EBFP) system promotes ecological integrity and adaptive management, the foundational Forest Law No. 6831 (1956) still legitimizes extractive uses under a broad “public interest” doctrine. This contradiction has enabled 94,148 permits covering 654,833 ha of forest conversion, while marginalizing nearly seven million forest-dependent villagers from decision-making. The study applies a doctrinal and qualitative document-analysis approach, integrating legal, institutional, and socio-economic dimensions. It employs a comparative design with five EU transition countries—Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece—selected for their shared post-socialist administrative legacies and diverse pathways of forest-governance reform. The analysis synthesizes legal norms, policy instruments, and institutional practices to identify drivers of reform inertia and regulatory capture. Findings reveal three interlinked failures: (1) institutional and ministerial conflicts that entrench centralized decision-making and weaken environmental oversight—illustrated by the fact that only 0.97% of Environmental Impact Assessments receive negative opinions; (2) economic and ecological losses, with foregone ecosystem-service values exceeding EUR 200 million annually and limited access to carbon markets; and (3) participatory deficits and social contestation, exemplified by local forest conflicts such as the Akbelen case. A comparative SWOT analysis indicates that Poland’s confrontational policy reforms triggered EU infringement penalties, Romania’s fragmented legal restitution fostered illegal logging networks, and Greece’s recent modernization offers lessons for gradual legal harmonization. Drawing on these insights, the paper recommends comprehensive Forest Law reform that integrates ecosystem-service valuation, climate adaptation, and transparent participatory mechanisms. Alignment with the EU Nature Restoration Regulation (2024/1991) and Biodiversity Strategy 2030 is proposed as a phased transition pathway for Türkiye’s candidate-country obligations. The study concludes that partial reforms reproduce systemic contradictions: bridging the policy–law divide requires confronting entrenched political-economy dynamics where state actors and extractive-industry interests remain institutionally intertwined.

1. Introduction

Türkiye possesses remarkable forest resources shaped by diverse biogeographical and climatic zones, yet its forest governance has long been characterized by a structural governance paradox. While contemporary instruments such as Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) and Ecosystem-Based Functional Planning (EBFP)—introduced in 2008 and later integrated into secondary regulations—embody internationally recognized ecological principles, the country’s foundational Forest Law No. 6831 (1956) continues to reflect a mid-twentieth-century resource-production paradigm. This law privileges extractive use over ecological integrity and lacks explicit provisions for biodiversity conservation, ecosystem resilience, or climate adaptation. Consequently, Türkiye’s Forest sector operates within a persistent policy–implementation gap, where modern ecological aspirations are constrained by an outdated legal and institutional framework [1,2,3,4].

The quantitative extent of this contradiction is striking. Between 1993 and 2022, 654,833 ha of state forests were irreversibly converted through 94,148 permits granted under Articles 16–18 of the 1956 Law. Only 0.97% of 6926 Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) received negative decisions, reflecting systemic regulatory capture and the predominance of economic priorities [5]. Meanwhile, Türkiye’s protected forest coverage (8.7%) remains far below the EU average (>25%) and the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 target of 30% protected areas [6,7]. These figures represent not only administrative inefficiencies but also foregone carbon sequestration, lost ecosystem-service value, and social exclusion for over seven million forest-dependent villagers [8].

Similar paradoxes can be observed across EU transition countries, where forest governance reforms have followed divergent yet instructive paths. Poland’s centralized control and restrictions on civic forestry triggered the Białowieża Forest infringement case, resulting in EUR 100,000 daily penalties imposed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) [9,10]. Romania’s rapid restitution and fragmented institutional reforms fostered informal timber networks and persistent illegal logging [11,12]. Bulgaria’s budgetary rigidity and short planning cycles undermined sustainability despite 50% FSC certification [13], while Greece’s 2024 Forest Law (No. 5106) now offers a gradual alignment with EU ecological standards. These comparative experiences demonstrate that partial reforms produce the most adverse outcomes—a critical warning for Türkiye as an EU candidate country navigating similar legal-institutional tensions.

Although previous research has addressed Türkiye’s biodiversity [2], environmental legislation [14], and SFM implementation [15], no study has systematically analyzed the policy–law paradox from an integrated legal, institutional, and political-economy perspective. Key questions remain unanswered: How are contradictions between modern ecological policies and production-oriented legislation managed in administrative and judicial practice? What ministerial conflicts, lobbying pressures, and power asymmetries sustain this governance inertia? What are the quantifiable costs in terms of foregone ecosystem-service values, lost carbon-market opportunities, and rural livelihood degradation? How do societal actors—communities, NGOs, and media—contest and negotiate this paradox? And, crucially, what lessons can Türkiye derive from Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece, which have already traversed comparable transitions?

To address these questions, this study adopts the Adaptive Governance framework [16], which conceptualizes flexibility, learning, and cross-scale coordination as prerequisites for resilience in social–ecological systems. This approach is complemented by Policy Arrangement Theory (PAT) [17,18], emphasizing the interplay of actors, rules, and discourses within power relations. Together, these perspectives illuminate how entrenched legal norms (the 1956 Law), institutional rivalries (between the Ministries of Environment, Forestry, and Energy), and prevailing development-centered discourses interact to reproduce a governance regime resistant to transformation—a pattern consistent with institutional path dependency [19].

Within this framework, the study employs a multi-faceted qualitative methodology, combining doctrinal legal analysis, document-based content analysis, and comparative evaluation of five EU transition cases. The countries were selected based on three criteria: (i) shared post-socialist or centralized administrative legacies; (ii) comparable experiences with EU environmental policy alignment; and (iii) availability of detailed legal and policy documentation. This comparative lens allows the identification of reform drivers, institutional innovations, and governance failures relevant to Türkiye’s Forest sector.

By integrating insights from law, political economy, economics, and sociology, the paper provides an interdisciplinary critique of Türkiye’s Forest governance system and advances evidence-based recommendations for closing the policy–law gap. Ultimately, it argues that reconciling ecological policy with legal reality is indispensable for Türkiye’s transition toward adaptive, transparent, and EU-aligned forest governance capable of balancing conservation, development, and societal participation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a multi-faceted qualitative research design to examine the complex ecology–law nexus shaping Türkiye’s Forest governance. The methodology integrates doctrinal legal analysis, document-based qualitative content analysis, and comparative institutional evaluation. It aims not only to describe but to critically assess how law, policy, and political economy interact to produce governance paradoxes in the forestry sector.

2.1. Doctrinal and Policy Analysis

A doctrinal legal analysis was conducted of Türkiye’s principal legislative framework, encompassing the Constitution of the Republic of Türkiye (1982), the Forest Law No. 6831 (1956), the Environmental Law No. 2872 (1983), and the National Parks Law No. 2873 (1983). The analysis traced amendments, secondary regulations, and administrative circulars to identify areas of normative conflict, hierarchical inconsistency, and policy misalignment. This legal mapping was complemented by an evaluation of relevant Constitutional Court rulings and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) procedures.

2.2. Qualitative Content Analysis and Triangulation

The qualitative phase followed established approaches to document analysis [20] and thematic analysis [21]. It involved a four-step analytical sequence:

- Data Collection: Compilation of primary laws, ministerial regulations, strategic plans, and judicial decisions between 1990–2024.

- Thematic Coding: Identification of recurring patterns concerning legal contradictions, ministerial mandates, and participatory mechanisms.

- Comparative Synthesis: Integration of institutional, economic, and social dimensions into a cohesive analytical framework.

- Validation and Triangulation: Cross-checking of findings with secondary academic literature, official statistics, and policy reports.

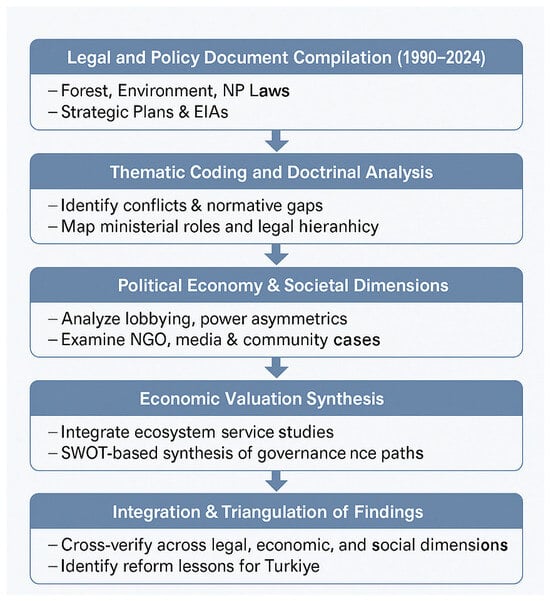

This methodological design was deemed most appropriate given the absence of direct stakeholder interviews, which were constrained by administrative access limitations. Instead, the study relies on publicly available legal and policy documentation, ensuring transparency and reproducibility of results. The overall sequence of analytical phases is summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates the integration of legal, economic, and societal dimensions in the methodological design.

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow diagram.

2.3. Political Economy and Economic Valuation Dimensions

To address the political economy dimension, inter-ministerial dynamics, lobbying activities, and institutional path dependencies were examined using policy reports, parliamentary records, and budget data [22,23]. The economic valuation component synthesized findings from existing ecosystem-service valuation studies [24,25,26,27,28], allowing for comparison between short-term fiscal gains and long-term ecological losses. The analysis also assessed barriers to carbon-market participation and monetized opportunity costs of foregone ecosystem services [29,30,31].

2.4. Societal and Participatory Dimensions

The societal component explored conflict and participation dynamics through case-based evidence, including the Akbelen Forest and Mount Ida disputes [5,32,33]. It further analyzed NGO advocacy strategies [34], public participation mechanisms within forest planning [8,35,36], and media framing of environmental controversies [37,38]. These cases illustrate how civic engagement and institutional asymmetries interact within Türkiye’s forestry governance landscape.

2.5. Comparative Institutional Analysis

To contextualize the national findings, a comparative institutional analysis was undertaken across five EU member states—Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece—that have undergone major forest-governance transitions. The selection was guided by three criteria:

- (i)

- Shared post-socialist or centralized administrative legacies;

- (ii)

- Relevance to EU environmental policy alignment and acquis transposition; and

- (iii)

- Availability of comprehensive legal and policy data.

The comparison focused on legal reforms, institutional restructuring, implementation gaps, and outcomes of adaptive governance reforms. A SWOT-based comparative synthesis was developed to identify transferable lessons for Türkiye’s ongoing policy and legislative modernization [9,10,11,12,13,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

2.6. Scope and Relevance

The geographical scope encompasses Türkiye’s entire 23 million hectares of forest land, justified by the centralized administrative structure of Turkish forestry and the nationwide implications of the policy–law gap [2]. The analysis holds particular relevance to Türkiye’s EU candidate status, where alignment with the environmental acquis communitarian remains a persistent policy and governance challenge [46,47]. The methodological integration of doctrinal, economic, and social perspectives provides a comprehensive understanding of how institutional rigidity, political incentives, and socio-ecological constraints jointly shape the dynamics of forest governance and reform in Türkiye.

3. Results

3.1. Fundamentals of Forest Ecology and Ecosystem Services

Understanding the complex structure and functioning of forest ecosystems is fundamental for evaluating the effectiveness of legal regulations aimed at protecting and managing these ecosystems [33,48]. Forests are complex ecosystems where living (biotic) components such as plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms interact with non-living (abiotic) environmental factors like soil, water, air, light, and temperature [49,50,51,52,53]. These interactions determine ecological roles (niche), geographical areas where communities settle (biotope), and resilience to environmental factors [54,55,56,57,58,59].

Türkiye’s forests provide invaluable ecosystem services classified into four categories [60,61,62]: Provisioning Services include timber, firewood, non-timber forest products (fruits, nuts, mushrooms), medicinal plants, genetic resources, and clean drinking water [63,64]. The General Directorate of Forestry (GDF) manages the production and distribution of these services. Regulating Services encompass climate regulation through carbon sequestration—Turkish forests store 64–100 tC/ha on average [24]—air and water quality improvement, erosion control, flood risk reduction, and pollination [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. These services are often unquantified in management decisions despite their enormous economic value.

Cultural Services provide recreation, tourism, aesthetic beauty, spiritual satisfaction, education, and scientific research opportunities [76,77,78]. GDF manages recreational sites and urban forests directly related to these services. Supporting Services include fundamental ecological processes like nutrient cycling, soil formation, primary production, and habitat provision [79,80,81,82]. Without these services, other ecosystem functions cannot be sustained.

The establishment of an Ecosystem Services Department within the GDF and its focus on payment systems and carbon markets [83,84] indicates growing institutional recognition. However, this structuring focuses primarily on services generating market value (carbon) [85], raising questions about whether the full value of all regulating and cultural services is understood and integrated into routine forest management decisions [86,87] and the general legal framework [88,89].

This imbalance between the mapped multifunctionality of forests and their selective economic valuation exemplifies the governance paradox: ecological complexity is acknowledged at the policy level but remains legally and economically invisible in decision-making.

3.2. The Turkish Legal Framework: A Dualistic Structure

Türkiye’s environmental and forest governance is characterized by a dualistic legal structure, with modern overarching laws coexisting uneasily with a sector-specific, antiquated primary law. The Environmental Law (No. 2872) establishes the “polluter pays” principle, mandates Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for major projects, and sets general goals for biodiversity and ecosystem protection [90,91]. The National Parks Law (No. 2873) and associated regulations establish a sophisticated classification system with strict protection regimes for sensitive areas [92,93]. Secondary regulations adopting the Ecosystem-Based Functional Planning (EBFP) approach and national Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Criteria and Indicators reflect contemporary ecological thinking [94]. These policies mandate consideration of forests’ multiple ecological and social functions beyond timber.

The Forest Law (No. 6831), enacted in 1956, remains the primary legal instrument governing forest management. Its core philosophy is rooted in definition, protection against direct threats (illegal logging, fire), and state-controlled exploitation of timber resources [95,96,97]. The law’s main structure does not explicitly incorporate modern concepts like biodiversity conservation, ecosystem health, resilience, or climate change adaptation [98,99]. Most critically, Articles 16, 17, and 18 contain provisions allowing non-forestry activities like mining, energy production, and tourism development within state forests through permits and servitudes [100,101].

Quantifying the Impact: Between 1993 and 2022, the permit system resulted in 94,148 total permits granted under the “public interest” doctrine [5], 654,833 hectares of state forests irreversibly lost [5], only 67 of 6926 Annex-1 EIA reports (0.97%) receiving negative decisions [5], and 1303 of 73,210 Annex-2 projects (1.8%) requiring full EIA [5]. Non-forestry uses reached 3.5% of all forest areas, dominated by energy and mining sectors [5].

This dualism creates the central problem: progressive principles embedded in modern policies and framework laws are systematically overridden by the permissions and priorities enshrined in the foundational—and legally more powerful—Forest Law This institutional rigidity represents an entrenched path dependency, where outdated legal norms override adaptive ecological frameworks, preventing transformation consistent with Adaptive Governance principles of flexibility and cross-sectoral coordination.

3.3. The Planning–Permitting Paradox: EBFP vs. Articles 16/17

A core finding is the operational conflict between planning and permitting. The Ecosystem-Based Functional Planning (EBFP) approach, legally adopted by GDF, requires management plans to identify and map multiple forest functions, including biodiversity conservation, soil and water protection, recreation, and timber production. Plans are designed to manage forests holistically based on these designated functions [94].

However, Articles 16, 17, and 18 of the Forest Law operate as a powerful parallel track that can override the logic of EBFP. These articles grant the administration authority to issue permits for high-impact activities like mining, energy plants, and large-scale tourism facilities in any forest area, regardless of its designated function in the EBFP plan, as long as a “public interest” argument is made [100,101].

The 2020 Akbelen Forest case illustrates this conflict: despite its ecological function designation, a coal mining expansion permit was issued to YK Energy (Limak Group/IC Ictas). Following widespread local protests, courts ruled in favor of the project, prioritizing economic interest over ecological integrity [32].

This institutional paradox reveals how the planning framework is progressive in theory but regressive in practice. The coexistence of EBFP and the 1956 permitting regime demonstrates a clear governance paradox—a modern planning tool rendered ineffective by the legal supremacy of an outdated statute.

3.4. Political Economy of the Policy–Law Gap

The persistence of the policy–law gap in Turkish forestry is deeply rooted in political economy dynamics, where entrenched bureaucratic interests, power asymmetries, and institutional inertia systematically favor extractive sectors over ecological and social goals [101]. Türkiye’s forest governance system, although administratively centralized, is politically fragmented across competing ministries with overlapping and often contradictory mandates. The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry retains exclusive control over state forests, while the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change oversees environmental impact assessments, biodiversity protection, and climate policy [102]. This structural dualism produces ministerial conflict and weak horizontal coordination.

Since the early 2000s, forest policy has been increasingly influenced by a growth-oriented development paradigm embedded in successive national plans that position natural resources as economic inputs rather than ecological assets. This approach manifests in regulatory capture, where forestry and energy policies are designed to accommodate private-sector demands rather than ecological thresholds. Political pressures to sustain macroeconomic growth through infrastructure, mining, and energy expansion have driven continuous legal amendments to Forest Law No. 6831, systematically broadening “public interest” exceptions under Articles 16–18.

Between 2002 and 2023, more than twenty amendments to the Forest Law, together with Presidential Decree 6990, progressively weakened environmental safeguards and shortened permitting procedures [103]. This process bypassed parliamentary scrutiny, concentrating discretionary authority within the executive branch. Such centralization reflects a path-dependent governance model where policy continuity favors administrative convenience over adaptive reform. Rather than re-evaluating the 1956 framework, successive governments have adapted it through incremental exceptions, producing what scholars describe as modernization without transformation.

These political dynamics are reinforced by asymmetrical information flows and limited transparency. Forest inventory data, environmental impact assessment (EIA) decisions, and concession details are rarely disclosed publicly, enabling bureaucratic discretion that benefits established industrial actors [104,105,106]. State–industry collusion is particularly visible in the mining and energy sectors, where many concession holders maintain close political ties. The near-universal approval rate of EIA applications—0.97% negative decisions across 6926 cases [5]—illustrates the functional erosion of environmental checks.

The result is a governance regime that prioritizes short-term fiscal gains and political legitimacy over long-term ecological stability. In the language of Adaptive Governance, the system exhibits low adaptive capacity and high rigidity traps: decision-making remains centralized, feedback from civil society is suppressed, and cross-sectoral learning mechanisms are absent [107,108]. This rigidity persists through institutional capture, fiscal dependence on concession revenues, and the delegitimization of civil society—over 1500 environmental and community organizations have been closed since 2016 [34], curtailing advocacy capacity and reinforcing state monopoly over forest discourse.

These dynamics mirror broader patterns observed in post-socialist EU transition states before accession, where economic ministries dominated environmental agencies until binding EU oversight imposed external discipline.

To contextualize Türkiye’s experience, a comparative institutional assessment was conducted across five EU transition countries—Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece—each facing distinct political economy constraints during forest governance reform (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of forest governance transitions in EU countries.

The comparative insights drawn from Table 1 highlight that successful governance transitions in EU states were achieved not merely through legal harmonization but by restructuring incentive systems and accountability mechanisms. In Türkiye’s case, the absence of supranational enforcement perpetuates the governance paradox: the same state that enacts progressive ecological policies simultaneously enables their violation through legal and institutional loopholes. Adaptive Governance emerged where transparency, cross-sectoral participation, and enforceable ecological standards became institutionalized—conditions that Türkiye has yet to establish.

3.5. Economic Dimensions of the Policy–Law Gap

The policy–law gap imposes substantial and systematically overlooked economic costs by prioritizing short-term extractive revenues over long-term ecological and social benefits. Valuation studies specific to Türkiye reveal the immense economic worth of forest ecosystem services—such as carbon storage, water regulation, and soil conservation—which can amount to hundreds of millions of dollars annually [24,25,26,27]. Yet, conventional cost–benefit analyses employed in project evaluation frameworks exclude non-market environmental goods, presenting a distorted picture that converts genuine economic gains into perceived losses [28].

This mispricing of nature generates substantial opportunity costs. For instance, the 654,833 hectares of forest allocated to mining, energy, and infrastructure permits represent an estimated annual loss of approximately EUR 130 million in ecosystem services, accumulating to EUR 3.9 billion over a typical 30-year concession period. These figures exclude the foregone carbon sequestration potential, which alone accounts for additional unquantified climate costs. The fiscal burden of this loss disproportionately affects rural and forest-dependent communities that rely on ecological functions for water, soil stability, and local livelihoods, while corporate actors and central authorities capture most financial benefits [32,109,110].

At the same time, the absence of long-term legal permanence in land-use rights precludes Türkiye’s participation in international carbon markets, now valued at over $850 billion globally. The core principle of these markets—permanence—requires guaranteed carbon retention for at least 100 years, a condition incompatible with Türkiye’s permitting regime under Articles 16–18, which allows any forest area to be converted to non-forestry use. Consequently, Türkiye forfeits an estimated $1.35 billion in potential annual carbon credit revenue [29,30,31]. This exclusion also prevents access to EU Green Deal funding mechanisms and voluntary carbon certification programs (such as VERRA and Gold Standard), which demand transparent legal frameworks for carbon ownership, monitoring, and benefit-sharing.

The economic paradox is thus twofold: forests are legally treated as productive assets for timber and concession revenues, yet their most valuable functions—climate regulation, water retention, and biodiversity maintenance—remain invisible in fiscal accounting [111]. This invisibility perpetuates a governance cycle in which extractive rents are recognized, but ecosystem dividends are ignored. Moreover, by centralizing fiscal benefits within the state budget, the current system excludes local stakeholders from co-benefit mechanisms such as payments for ecosystem services (PES) or community forest enterprises, which are increasingly adopted in EU and Latin American countries as instruments of adaptive and inclusive forest governance [112,113].

Comparative evidence underscores that countries integrating ecosystem accounting into fiscal planning—such as France, Finland, and Costa Rica—achieved improved policy coherence between environmental protection and economic growth. Türkiye’s continued reliance on concession-based revenue, by contrast, reinforces a fiscal trap: state institutions become financially dependent on the very permits that erode the natural capital they are mandated to protect [114,115]. This fiscal dependency not only undermines adaptive governance but also deters sustainable investment.

The global pool of environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-linked assets, projected to exceed $53 trillion by 2025, systematically avoids jurisdictions characterized by policy instability, tenure uncertainty, and opaque concession processes—all of which apply to Türkiye [5,11,116,117,118]. The frequent, politically motivated amendments to the Forest Law further discourage private-sector participation in sustainable forest management, certification (FSC, PEFC), and nature-based carbon projects.

Ultimately, the economic dimension of the governance paradox reveals that unsustainable fiscal logic—prioritizing immediate extractive income over long-term ecological capital—locks Türkiye into a cycle of environmental degradation and financial underperformance. Integrating natural capital accounting and ecosystem-service valuation into the legal and budgetary framework would represent a transformative step toward adaptive governance. Such integration would not only reduce opportunity costs but also enable Türkiye to access green finance instruments, align with EU climate objectives, and position its forestry sector within the rapidly growing global market for sustainable investment.

3.6. Societal Dimensions

The policy–law gap in Turkish forestry generates profound societal repercussions, most visibly through a participation paradox, where formal rights to public involvement coexist with a deeply entrenched top-down management tradition [8,35,119]. This paradox undermines both the legitimacy and effectiveness of forest governance by excluding the very actors most affected by forest policy outcomes. Although public participation mechanisms are formally included under Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) procedures and national forestry plans, these mechanisms often operate as symbolic consultations rather than genuine decision-making platforms [120]. The European Commission has repeatedly noted that Türkiye fails to meet EU standards for inclusive and deliberative public consultation [46,121].

High-profile conflicts such as those in Akbelen Forest and Mount Ida (Kazdağları) reveal how this participation deficit translates into open social contestation. In both cases, administrative permits justified under the vague and elastic “public interest” doctrine [122] were used to override constitutional provisions protecting forests as “national assets” [115]. Local protests were met with suppression, while environmental defenders faced stigmatization and criminalization. At Akbelen, long-term community sit-ins were dispersed with excessive force in 2023 [32], while in Kazdağları, legal challenges were dismissed despite evident ecological harm [33]. These events illustrate how environmental governance failures spill over into the societal domain, eroding trust in institutions and deepening social polarization.

Despite this hostile context, Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations (ENGOs) such as TEMA Foundation, WWF-Türkiye, Doğa Derneği, and Ekoloji Birliği have developed adaptive advocacy strategies. These include forging alliances with local communities, pursuing strategic litigation, mobilizing media visibility, and engaging with international environmental networks [34,123]. Such approaches embody elements of adaptive governance, emphasizing learning, collaboration, and multi-level engagement. However, their effectiveness remains limited by restrictive legal frameworks and a polarized media environment. Pro-government media typically frame extractive projects as symbols of national progress, while environmental opposition is portrayed as “anti-development” or politically motivated [37,108,124]. Opposition media, conversely, emphasize deforestation and corruption but often lack the institutional reach to influence policy outcomes [125]. This discursive polarization prevents evidence-based dialogue and reinforces the power asymmetries that sustain the policy–law gap.

Underlying these tensions is a structural asymmetry in property and participation. Approximately 99.9% of Türkiye’s forests remain state-owned [126], managed under a centralized bureaucratic model. In contrast, about seven million forest villagers depend directly on these ecosystems for fuelwood, grazing, and non-timber forest products [127]. Their customary resource-use practices constitute a form of informal governance pluralism [128], yet these systems lack formal legal recognition or co-management rights [113,127]. Instead, forest villagers are typically engaged as seasonal laborers or concession beneficiaries under short-term, state-controlled arrangements, reinforcing dependency rather than empowerment.

This persistent participation paradox violates the principles of polycentricity and knowledge sharing central to Adaptive Governance theory. Rather than fostering mutual learning and distributed decision-making, the current model sustains hierarchical control and limited transparency. The absence of institutionalized platforms for community input, knowledge integration, and conflict resolution not only undermines social equity but also weakens ecological outcomes. In the absence of participatory legitimacy, even well-intentioned conservation measures face local resistance, reducing their long-term sustainability.

Empirical evidence from EU member states underscores that participatory governance reforms—such as community forestry in Portugal and Spain or co-management councils in Finland—improve both ecological resilience and social trust. For Türkiye, embracing these models would mean institutionalizing participation not as a procedural formality but as a structural necessity for adaptive governance. Recognizing and formalizing community rights, enhancing transparency in permitting, and integrating citizen science and local knowledge into forest planning processes are key steps toward bridging the societal dimension of the policy–law gap.

3.7. Legal Gaps and Economic Interests

Beyond the planning-permitting paradox, the 1956 Forest Law contains no specific provisions addressing modern ecological challenges, creating legal vacuums in critical areas. The law lacks any mention of climate adaptation strategies, temperature-resilient species selection, or disaster risk reduction—despite Mediterranean forests facing severe climate impacts. Research projects that 51.2% of Mediterranean tree species currently vulnerable could rise to 85.2% by 2100 [129]. Turkish forests experienced 2862 forest fires in 2021 (worst year on record) [130], yet legal frameworks for climate-smart forestry remain embryonic. The EU Forest Strategy 2030 makes climate adaptation a central pillar, requiring member states to integrate climate resilience into forest management [131]. The proposed Forest Monitoring Law (2023) would establish binding monitoring frameworks for forest resilience [132]. Türkiye’s legal framework lacks equivalent provisions, leaving climate adaptation to discretionary policies easily overridden by permit decisions.

The Forest Law contains no comprehensive framework for Invasive Alien Species (IAS) prevention or management—a critical gap as globalization increases invasion risks. The EU Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 establishes listing, early detection, rapid eradication, and management requirements for IAS [133]. Research emphasizes that “legal frameworks for invasive species management” must include clear prevention, detection, control, and enforcement provisions [134]. Türkiye’s absence of such frameworks leaves management to ad hoc responses.

No explicit definition or penalties exist for forest soil contamination in the 1956 Forest Law [135,136]. While the Environmental Law (No. 2872) addresses general pollution, the lack of forest-specific provisions creates enforcement gaps—particularly relevant for mining permits that can cause heavy metal contamination, acid drainage, and long-term soil degradation.

The establishment of GDF’s Ecosystem Services Department [83,84] represents policy-level recognition, but lacks a binding legal foundation in primary law. Without Forest Law provisions establishing legal frameworks for carbon crediting, monitoring, verification, and benefit-sharing, participation in compliance and voluntary carbon markets remains problematic due to regulatory uncertainty documented in economic analysis [29,30,31].

When forestry and environmental law conflicts in Türkiye reach the courts, legal gaps are further deepened by judicial ambiguity. It is observed that the judiciary does not follow a consistent path in balancing competing legal principles and generally defers to the administration’s broad interpretation of “public interest,” which prioritizes economic development [137,138,139]. In cases such as Akbelen and Kazdağları (Mount Ida), it has been documented that court decisions have favored mining activities or have been insufficient in halting the projects [32,33]. This situation stands in sharp contrast to the approach of the European Union’s Court of Justice in the Białowieża Forest case, which clearly established the legal supremacy of ecological protection and enforced it with heavy financial penalties [9,10,39]. The absence of such a clear legal hierarchy and enforcement power in Türkiye renders legal challenges “formalistic” and prevents the courts from serving as a reliable accountability mechanism for ecological protection.

3.8. Comparative Insights for Türkiye

The comparative assessment (Table 1) underscores that successful forest governance transitions in EU member states hinged on three interrelated enabling factors:

- Legal alignment that enforces ecological supremacy and judicial accountability (Poland, Greece);

- Fiscal mechanisms that support multi-decadal forest cycles and reduce dependency on short-term revenues (Bulgaria, Czechia);

- Participatory decentralization ensuring ownership clarity and community involvement (Romania).

Poland’s Białowieża Forest case illustrates enforceable ecological supremacy through direct financial sanctions imposed by the Court of Justice of the European Union, demonstrating that binding legal instruments are crucial for compliance [9,10,39]. Romania’s fragmented restitution experience highlights the risks of incomplete reforms and unclear ownership, where decentralization without capacity building produced illegal logging and governance instability [11,12,40]. Bulgaria’s budgetary rigidity demonstrates that fiscal structures must be compatible with forest rotation cycles to ensure long-term planning and resilience [13,41]. Greece’s 2024 hybrid model, combining state and private management, exemplifies a gradual modernization pathway within limited institutional capacity [44,45]. From an Adaptive Governance perspective, these enabling factors represent three dimensions of institutional adaptability:

- Rule enforcement and reflexivity (legal alignment);

- Learning and feedback loops (fiscal adaptability);

- Polycentric participation and knowledge sharing (decentralization).

Türkiye diverges from these pathways due to its persistent centralized authority, legal rigidity, and weak adaptive capacity. Bridging this divide requires comprehensive reform of the Forest Law (No. 6831) that integrates ecosystem-service valuation, climate adaptation, and participatory governance. Embedding Adaptive Governance principles—flexibility, transparency, and institutional learning—would transform Türkiye’s static legal architecture into a dynamic, EU-aligned system capable of reconciling conservation, economic development, and social equity.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Multi-Dimensional Policy–Law Gap

Türkiye’s forest governance paradox operates as a multi-dimensional policy–law gap encompassing four interrelated domains—legal, institutional, economic, and societal—each reinforcing rigidity and undermining adaptability. At its core lies the enduring conflict between the 1956 Forest Law’s production-oriented logic and the ecosystem-based philosophy of modern Ecosystem-Based Functional Planning (EBFP). This tension manifests in what can be termed the planning–permitting paradox: while EBFP plans designate ecological protection zones, Articles 16–18 of the Forest Law legally authorize extractive industry permits that can override these ecological designations. Thus, the policy–law gap constitutes the overarching structural condition, and the planning–permitting paradox its operational expression.

This dualism persists due to legal path dependency and the state’s reluctance to reform the 1956 framework despite multiple amendments since 2002. Each reform cycle has reinforced rather than replaced the outdated paradigm, producing a governance regime resistant to ecological learning. Adaptive Governance theory identifies such rigidity as a failure of reflexivity—the inability of institutions to revise their foundational rules in response to environmental feedback. In Türkiye’s case, reflexivity is blocked by the dominance of legal continuity over ecological adaptation.

At the institutional level, ministerial conflicts privilege economic development over environmental protection, while regulatory capture ensures that decision-making remains skewed toward extractive industries. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process functions largely as a procedural formality, with 99% approval rates indicating near-total administrative compliance rather than environmental scrutiny [5]. These patterns reveal a system structurally aligned with power asymmetry, where policy actors representing forestry, energy, and mining interests dominate decision-making arenas. The result is a governance architecture that performs stability but delivers ecological erosion.

The economic dimension of this gap reflects the absence of ecological accounting. Forest conversion decisions ignore the value of ecosystem services such as water regulation (EUR 201 million annually [27]) and carbon sequestration (potentially exceeding $1 billion per year [29,30,31]). By maximizing short-term extractive revenue, the state foregoes long-term ecological and social capital, effectively transferring wealth from rural communities to corporate actors. This distributional inequity exemplifies a maladaptive feedback loop: economic policies designed for immediate fiscal gain generate ecological degradation, which in turn erodes the very natural capital that sustains economic productivity.

At the societal level, the exclusion of forest-dependent communities from governance perpetuates legitimacy crises. Approximately seven million forest villagers remain outside formal decision-making mechanisms [8], while civil society organizations face institutional constraints—over 1500 environmental NGOs have been closed since 2016 [34]. The resulting participation deficit breeds social conflict, exemplified by the Akbelen protests [32], and amplifies polarization through politicized media framing [37,108,124]. These conditions violate the polycentric participation and social learning principles essential to adaptive governance.

Taken together, these four domains—legal rigidity, institutional capture, economic undervaluation, and societal exclusion—interact in a negative feedback loop that sustains the policy–law gap. The system reproduces its own inefficiencies: political economy dynamics (lobbying, capture) yield economic outcomes favoring extractive sectors; these, in turn, trigger societal conflicts that justify further administrative control, deepening rigidity. In adaptive governance terms, Türkiye’s forest governance exhibits a maladaptive equilibrium—stable in form, but unsustainable in function—where institutional learning is systematically suppressed.

4.2. Comparative Insights: Learning from EU Transition Country Failures

To contextualize Türkiye’s policy–law gap within a broader European trajectory, a comparative analysis was undertaken across five EU transition countries—Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece—that faced parallel challenges of reconciling legacy forest regimes with new ecological and governance standards. These cases reveal three recurrent failure patterns common to transitional systems: (1) incomplete legal reform, (2) fiscal misalignment, and (3) weak participatory decentralization. Together, they illustrate how structural rigidity and fragmented reform undermine adaptive capacity even under EU supervision.

Romania provides the clearest example of incomplete reform. Three successive restitution laws (1991, 2000, 2005) sought to decentralize ownership without establishing coherent governance frameworks. The result was a fragmented property structure—51% non-state ownership—and the emergence of powerful informal networks and persistent illegal logging [11,12,40]. Implication for Türkiye: piecemeal reform of Articles 16–18 without an integrated legal restructuring risks creating similar incoherence, where administrative exceptions proliferate faster than oversight capacity.

Bulgaria demonstrates fiscal misalignment. The country’s rigid budget mechanism—requiring annual surplus returns—proved incompatible with the multi-decadal nature of forest cycles, forcing short-term financial closure in long-term ecological systems [13,41]. Although nearly 50% of forests achieved FSC certification, enforcement remained weak due to budgetary contradictions. Implication for Türkiye: forest financing mechanisms must align with ecological time horizons; current reliance on permit revenues replicates Bulgaria’s short-termism, undermining sustainability despite formal policy improvements.

Czechia illustrates the limits of fragmented restitution. After reforms, 145,000 new forest owners emerged, 90% of whom possessed parcels smaller than 2 hectares—too small for viable management [42,43]. When the bark beetle outbreak (2015–2020) hit, fragmented governance and poor coordination magnified the crisis, exposing the absence of adaptive learning structures. Implication for Türkiye: while its 99.9% state ownership avoids fragmentation, over-centralization produces the opposite problem—low responsiveness and lack of community co-management. Introducing participatory forestry councils could provide a “polycentric middle path” between state monopoly and atomized ownership.

Poland’s case highlights enforceable ecological supremacy. The Białowieża Forest conflict culminated in the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) imposing EUR 100,000 daily penalties for violations of the Birds and Habitats Directives [9,10,39]. This direct legal enforcement forced policy realignment and reaffirmed ecological primacy. Implication for Türkiye: as an EU candidate, Türkiye will ultimately face external accountability under accession conditions; proactive legal alignment is strategically preferable to reactive compliance through penalty.

Greece, the most recent reformer, represents incremental modernization under constrained capacity. The 2024 hybrid public–private management model (Law 5106/2024) aims to address limited state capacity by enabling private-sector and community participation in forest operations [44,45]. While implementation is still nascent, early results indicate greater financial sustainability and innovation in restoration. Implication for Türkiye: hybrid governance models—combining state oversight with localized management—could enhance flexibility and innovation within Türkiye’s state-dominant system.

Across these cases, a common thread emerges: partial reforms consistently produce maladaptive outcomes. Legal amendments without institutional reform, or fiscal modernization without participatory frameworks, fail to deliver resilience. For Türkiye, this comparative evidence underscores the necessity of comprehensive, sequenced reform—simultaneously addressing legal, institutional, economic, and participatory dimensions. Adaptive governance can only emerge when these elements evolve together, creating reflexive feedback between law, policy, and society.

4.3. Theoretical Contributions: Advancing the Adaptive Governance Framework

This study advances adaptive governance theory by demonstrating how policy–law gaps undermine ecosystem resilience in transitional and semi-authoritarian contexts. While most research on adaptive governance emphasizes flexibility, learning, and stakeholder participation as drivers of institutional resilience [16,140,141], these assumptions often rest on the presence of pluralism, legal certainty, and the rule of law. Türkiye’s forest governance, characterized by legal rigidity and ministerial dominance, challenges these assumptions and reveals that the barriers to adaptation are not procedural but structural. The findings thus extend adaptive governance theory to political systems where legal frameworks and power asymmetries fundamentally limit institutional learning.

The first contribution lies in identifying legal path dependency as a structural constraint that precedes and prevents adaptive change. Existing studies focus on how institutions evolve through feedback and learning, yet Türkiye’s case shows that when a primary law—such as the 1956 Forest Law—embeds an outdated production-oriented paradigm, adaptation becomes legally impossible without dismantling that framework. Despite twelve amendments since 2002, the law’s core logic remains unchanged, reproducing rather than reforming its extractive orientation. Adaptive governance in such contexts requires not only improved processes but also the deliberate unblocking of rigid legal architectures that suppress change.

The second contribution relates to the role of power asymmetry as a determining factor in governance outcomes. Although adaptive governance theory acknowledges the influence of power, it rarely addresses how entrenched interests capture decision-making structures. In Türkiye, the dominance of state ministries and extractive industries produces regulatory capture that neutralizes participatory mechanisms. The 99% Environmental Impact Assessment approval rate and centralized ministerial control exemplify how procedural reforms become symbolic when power is monopolized. Adaptive governance, therefore, cannot rely solely on pluralistic ideals but must explicitly confront and redistribute institutional power.

The third contribution involves recognizing that economic valuation, while essential for informed decision-making, is insufficient for adaptation unless embedded in enforceable legal frameworks. The quantified economic value of Türkiye’s forest ecosystem services—estimated at over EUR 200 million annually [24,25,26,27]—has not translated into policy change because valuation remains non-binding. The case demonstrates that ecological knowledge without institutional accountability perpetuates the very inefficiencies adaptive governance seeks to resolve. Effective adaptation requires mechanisms that ensure ecosystem valuation informs and constrains administrative discretion.

Finally, the study underscores the significance of societal legitimacy as a precondition for adaptive governance. Even the most sophisticated legal or economic reforms fail if they lack public trust and social inclusion. Türkiye’s forest conflicts in Akbelen and Mount Ida reveal how exclusionary governance erodes legitimacy and provokes resistance. When civil society is constrained and communities are marginalized, adaptive learning loops collapse. Legitimacy thus functions as the social foundation upon which adaptive governance must rest, linking institutional flexibility with public consent and long-term resilience.

By integrating these dimensions—legal rigidity, power asymmetry, economic accountability, and societal legitimacy—this study expands adaptive governance theory beyond its Western institutional assumptions. It demonstrates that in transitional and semi-authoritarian contexts, adaptation requires structural transformation rather than procedural adjustment. Adaptive governance, therefore, should be conceived not merely as an environmental management framework but as a political reform paradigm capable of reconciling ecological sustainability with democratic accountability.

4.4. Policy Implications

Türkiye’s EU candidacy creates both external pressure and a unique opportunity for comprehensive forest governance reform. The evolving EU environmental acquis now establishes binding ecological standards that Türkiye will ultimately be required to meet during the accession process. These include the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, which mandates that 30% of terrestrial and marine areas be protected and 10% strictly conserved [6,7,47,142]; the EU Nature Restoration Regulation (2024/1991), which legally obliges member states to restore at least 30% of degraded habitats by 2030 and to ensure that forest ecosystems contribute to climate adaptation, biodiversity, and carbon neutrality [143]; and the EU Forest Strategy 2030, which redefines forest policy around multifunctionality, adaptive management, and social participation [131]. Collectively, these frameworks make clear that biodiversity protection, ecosystem-service valuation, and participatory governance are not optional—they are prerequisites for alignment with the European Green Deal.

In contrast, Türkiye’s Forest Law (No. 6831) continues to reflect a mid-20th-century resource-extraction paradigm. Its silence on biodiversity, ecosystem services, climate adaptation, and invasive alien species demonstrates the deep misalignment between national forestry law and EU norms. The Environmental Law (No. 2872) and National Parks Law (No. 2873) provide partial alignment with EU environmental principles, but they lack legal supremacy over the Forest Law, allowing extractive permits under Articles 16–18 to override ecological designations. This legal hierarchy must be reversed: ecological integrity should have precedence over sectoral exploitation. Without this, Türkiye cannot credibly claim progress toward EU compliance.

The EU Invasive Alien Species Regulation (1143/2014) offers a strong example of the type of comprehensive framework Türkiye currently lacks. It mandates listing, early detection, rapid eradication, and management mechanisms for IAS [133], while Türkiye’s existing framework has no preventive structure or enforcement tools. Similarly, the FAO Forest Law Guidelines emphasize that forest legislation should secure good governance, improve law compliance, address illegal logging, and recognize customary rights [144,145]. Türkiye’s current institutional architecture fails in these dimensions due to ministerial fragmentation, limited inter-agency coordination, and the near-total absence of community co-management provisions.

Policy reform, therefore, must proceed on four parallel tracks. First, legal reform is essential: a complete revision of the 1956 Forest Law should incorporate climate-adaptive principles, explicit references to ecosystem services, restoration obligations, and transparent permitting criteria. Second, institutional restructuring must strengthen coordination between the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, ensuring that environmental authority is not subordinated to extractive economic objectives. Third, economic mechanisms should internalize ecosystem values through national Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes, carbon crediting frameworks, and incentives for certified sustainable forest management (FSC/PEFC). Fourth, participatory reforms must formally recognize community and NGO roles in forest governance, protect the operational freedom of environmental organizations, and establish local advisory councils consistent with the Aarhus Convention’s principles of access to information, participation, and justice.

Implementing these four dimensions together would align Türkiye with EU environmental standards while addressing domestic governance failures. Partial or isolated reforms—such as amending only Articles 16 and 17—would reproduce the same contradictions observed in Romania’s fragmented restitution and Bulgaria’s budgetary rigidity [11,12,13,40,41,42]. The evidence from comparative cases is unambiguous: fragmented, incremental reforms fail; comprehensive, sequenced reforms succeed. The long-term policy lesson is that ecological modernization cannot occur without legal modernization. Türkiye’s path toward adaptive and sustainable forest governance, therefore, depends on its willingness to reconceptualize forests not as extractive resources but as living infrastructure essential to national climate resilience, economic diversification, and social equity.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study, while providing a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment of Türkiye’s forest governance paradox, inevitably faces several methodological and empirical limitations. The research design primarily relied on qualitative and doctrinal analysis, which enabled an in-depth examination of legal texts, institutional frameworks, and comparative governance structures but limited the extent to which empirical verification could be performed. Future studies should complement this approach with systematic field-based data collection, including semi-structured interviews with policymakers, forestry officials, and community representatives. Such empirical depth would allow for triangulation between legal interpretation, administrative practice, and local experience, thereby strengthening the validity of conclusions about the policy–law gap’s real-world effects.

A second limitation concerns the scope of the comparative analysis. The study concentrated on five EU transition countries—Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Greece—that represent relevant but not exhaustive examples of governance transition. Expanding future research to include additional Mediterranean and non-EU contexts (such as Croatia, North Macedonia, or Morocco) could provide broader insights into how varying political regimes, legal cultures, and EU alignment pressures shape forest governance trajectories [146,147,148]. Comparative regional datasets could also enable cluster analysis to identify structural similarities and reform typologies across governance models.

A third limitation lies in the reliance on secondary ecosystem valuation data. Although valuation studies provided a robust foundation for estimating the magnitude of economic losses from forest conversion [24,25,26,27,28], future research should generate primary economic data through spatially explicit valuation of key ecosystem services—particularly carbon sequestration, hydrological regulation, and cultural services—in high-conflict areas such as Akbelen, Mount Ida, and the Western Black Sea region. Incorporating geospatial modeling, carbon accounting, and remote sensing data could reveal how localized permit decisions aggregate into national-scale ecological and economic outcomes.

Furthermore, the socio-legal dimensions of governance legitimacy warrant more granular investigation. Future studies should employ stakeholder mapping, participatory observation, and discourse analysis to understand how narratives of “public interest,” “national development,” and “environmental security” are constructed and contested among state, corporate, and civil actors. Such work would help clarify the mechanisms of power reproduction within Türkiye’s forestry institutions and provide empirically grounded pathways for democratizing forest governance.

Finally, future research should aim to develop a comprehensive Forest Governance Observatory—a national database systematically recording legal amendments, administrative decisions, Environmental Impact Assessments, and judicial rulings relevant to forestry and conservation. This database could facilitate longitudinal studies of how law, policy, and practice evolve, enabling the application of quantitative techniques such as policy diffusion modeling and institutional network analysis. It would also serve as a tool for evidence-based policymaking, providing the transparency and accountability necessary to align Türkiye’s forest sector with both EU accession requirements and the broader principles of adaptive governance.

In sum, while this study provides an important conceptual and analytical foundation, advancing understanding of Türkiye’s policy–law gap will require future interdisciplinary research that integrates doctrinal precision with empirical fieldwork, comparative breadth, and data-driven analysis. Bridging these gaps will be essential not only for academic rigor but also for informing the next generation of forest policy reforms that balance ecological integrity, economic development, and social justice.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Türkiye’s forest governance system faces a fundamental and multi-dimensional policy–implementation gap rooted in the persistence of an outdated 1956 Forest Law that remains structurally misaligned with contemporary principles of ecosystem-based and adaptive management. The resulting dualism—between modern ecological policy and antiquated legal design—has produced systemic governance failures: 654,833 hectares of state forest have been irreversibly converted through permitting mechanisms [5]; administrative and judicial interpretations consistently privilege short-term extractive interests [22,137]; and the legal framework remains unprepared for climate change, biodiversity loss, and social equity challenges [129]. These are not isolated technical shortcomings but reflections of deeper political economy dynamics—regulatory capture by extractive industries [22,23,107], economic models that externalize ecological costs [24,25,26,27,28], and participatory deficits that exclude forest-dependent communities from decision-making [8]. Collectively, these dynamics perpetuate a governance regime that is both ecologically unsustainable and institutionally rigid.

The comparative findings further confirm that incremental or piecemeal reforms—similar to Romania’s fragmented restitution, Bulgaria’s budget rigidity, or Poland’s delayed compliance with EU ecological law [9,10,11,12,13]—fail to address the systemic nature of governance dysfunction. Meaningful reform, therefore, requires a comprehensive and simultaneous transformation across legal, institutional, economic, and participatory dimensions. Legally, Türkiye must move beyond minor amendments and undertake a full revision of the 1956 Forest Law to embed biodiversity conservation, ecosystem-service valuation, and climate adaptation as binding principles. This reform should establish an explicit hierarchy of norms whereby ecological designations and ecosystem functions hold legal precedence over extractive authorizations. The ambiguous “public interest” clause in Articles 16–18 must be narrowly redefined and subject to transparent, science-based criteria, while new legal mechanisms should be introduced for emerging issues such as invasive alien species, soil contamination, and carbon crediting [131,133,143].

Institutionally, reform must strengthen coordination between the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, mandating joint decision-making for high-impact land-use permits. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process must be depoliticized and made subject to independent review to ensure accountability. Protected area coverage should be expanded toward the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 target of 30% [6,7,142], and community participation must be legally recognized through mechanisms that guarantee local representation and the protection of customary rights [113,121].

Economically, the integration of ecosystem-service valuation into all forest-related permitting and investment decisions is essential for making the true cost of resource extraction visible. Establishing a national payment for ecosystem services (PES) framework and enabling participation in carbon markets could convert ecological stewardship into a viable economic pathway. Socially, shifting toward inclusive and transparent governance—where forest villagers, NGOs, and scientific actors share decision-making power—will enhance legitimacy, equity, and resilience.

In the long term, Türkiye’s transition must embrace the principles of adaptive governance: flexibility, transparency, multi-level coordination, and institutional learning. Moving from a centralized, state-dominant regime toward polycentric, regionalized forest governance structures would align Türkiye with EU and global best practices. Achieving this transformation requires political will to confront entrenched interests and a clear recognition that ecological modernization and democratic accountability are mutually reinforcing.

Türkiye now stands at a critical juncture. The current governance crisis—though severe—offers a rare opportunity to realign forest policy with the country’s ecological, social, and economic realities. International experience from countries such as Costa Rica, Finland, and Germany shows that comprehensive forest reform grounded in science, participation, and justice can yield durable ecological recovery and economic prosperity [149,150,151]. Bridging Türkiye’s policy–law gap through courageous, evidence-based, and multi-dimensional reform is not merely a legal necessity but a societal imperative for safeguarding its globally significant forest heritage, empowering its seven million forest-dependent citizens, and ensuring a resilient and sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ü.B., M.Ç., H.T.Y., N.T.Y., D.P., M.A. and M.Š.; methodology, M.Ç., Ü.B. and D.P.; software, M.Ç. and Ü.B.; validation, D.P., Ü.B., M.Š. and M.Ç.; formal analysis, M.Ç., Ü.B., H.T.Y., N.T.Y., D.P., M.Š. and M.A.; investigation, M.Ç., Ü.B. and D.P.; resources, data curation; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ç., Ü.B. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, M.Ç., Ü.B., H.T.Y., N.T.Y. and D.P.; visualization, D.P., M.Š. and M.A.; supervision, D.P., M.Š. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dönmez, A.A.; Yerli, S.V.; Pullaiah, T. Biodiversity in Türkiye. Glob. Biodivers. 2018, 2, 397–442. [Google Scholar]

- Şekercioğlu, Ç.H.; Anderson, S.; Akçay, E.; Bilgin, R.; Can, Ö.E.; Semiz, G.; Tavşanoğlu, Ç.; Yokeş, M.B.; Soyumert, A.; İpekdal, K.; et al. Türkiye’s globally important biodiversity in crisis. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2752–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, H. Managing the fragmentation of international environmental law: Forests at the intersection of the climate and biodiversity regimes. N. Y. Univ. J. Int. Law Politics 2011, 44, 1205. [Google Scholar]

- Bosselmann, K. Losing the forest for the trees: Environmental reductionism in the law. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2424–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, D.; Atmiş, E.; Erdönmez, C. A Different Dimension in Deforestation and Forest Degradation: Non-Forestry Uses of Forests in Türkiye. Land Use Policy 2024, 139, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. Communication COM(2020). 380 Final. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. Protected Planet: Protected Area Profile for Türkiye (September 2025). 2025. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/country/TUR (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Atmis, E.; Günşen, H.B.; Lise, W. Public participation in forestry in Türkiye. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Białowieża Forest Case: Judgement by Court of Justice of the EU. IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law. 2018. Available online: https://iucn.org/news/world-commission-environmental-law/201805/białowieża-forest-case-judgement-court-justice-eu (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Notes from Poland. Polish Law Does Not Adequately Protect Forests, Finds EU Court. 2 March 2023. Available online: https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/03/02/polish-law-does-not-adequately-protect-forests-finds-eu-court/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Bouriaud, L.; Nichiforel, L.; Nunes, L.; Pereira, H.; Bajraktari, A. The winding road towards sustainable forest management in Romania, 1989–2022: A case study of post-communist social–ecological transition. Land 2022, 11, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestpolicy.org. Romania (Country Profile). Last Updated June 2024. Available online: https://forestpolicy.org/risk-tool/country/romania (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Country Report—Bulgaria; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/ad744e/AD744E05.htm (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Elvan, O.D. Analysis of environmental impact assessment practices and legislation in Türkiye. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmiş, E.; Günşen, H. Ecosystem services in recreational forests of Türkiye: Analysis of national forest policies and scientific studies. Int. For. Rev. 2022, 24, 469–485. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobšinská, Z.; Živojinović, I.; Nedeljković, J.; Petrović, N.; Jarský, V.; Oliva, J.; Šálka, J.; Sarvašová, Z.; Weiss, G. Actor power in the restitution processes of forests in three European countries in transition. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.T.; Saint Ville, A.S.; Song, A.M.; Po, J.Y.; Berthet, E.; Brammer, J.R.; Brunet, N.D.; Jayaprakash, L.G.; Lowitt, K.N.; Rastogi, A. A framework for analyzing institutional gaps in natural resource governance. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 823–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkent, E.Z. Reflections of Stakeholders on the Forest Resources Governance with Power Analysis in Türkiye. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, M.; Djoudi, H.; Moeliono, M.; Pham, T.T.; Wong, G.Y.; Di Gregorio, M. The forest frontier in the Global South: Climate change policies and the promise of development and equity. Ambio 2021, 50, 2010–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkent, E.Z. Assessment and valuation of key ecosystem services provided by two forest ecosystems in Türkiye. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 32670–32681. [Google Scholar]

- Başkent, E.Z. Characterizing and Assessing Key Ecosystem Services in a Representative Forest Ecosystem in Türkiye. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 74, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirici, M.E.; Berberoglu, S. Terrestrial carbon dynamics and economic valuation of ecosystem service for land use management in the Mediterranean region. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, S.E.; Hein, L.; Cuceloglu, G. Accounting for the water related ecosystem services of forests in the Southern Aegean region of Turkey. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez-de-Salamanca, Á. Valuation of ecosystem services: A source of financing Mediterranean loss-making forests. Small-Scale For. 2023, 22, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Midkiff, D.; Yin, R.; Zhang, H. Carbon finance and funding for forest sector climate solutions: A review and synthesis of the principles, policies, and practices. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1309885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, B.K.; Cullenward, D.; Strong, A.L.; Grubert, E.; Heilmayr, R.; Sivas, D.A.; Wara, M. Managing uncertainty in carbon offsets: Insights from California’s standardized approach. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.A.P.; Wunder, S.; Sills, E.O.; Börner, J.; Rifai, S.W.; Neidermeier, A.N.; Frey, G.P.; Kontoleon, A. Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation. Science 2023, 381, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limb, L. Grandparents Among Activists Defending Turkish Forest from Coal Mining. Euronews Green, 28 July 2023. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2023/07/28/we-will-not-give-up-how-a-turkish-forest-became-the-site-of-fierce-coal-mine-resistance (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Demir, M.; Barton, G. Correlates of deforestation in Türkiye: Evidence from high-resolution satellite data. New Perspect. Türkiye 2023, 68, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bey, N. Configurational analysis of environmental NGOs and their influence on environmental policy in Türkiye. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krott, M. Part 1: The policies for shaping the rural environment. In The Multifunctional Role of Forests: Policies, Methods and Case Studies; Cesaro, L., Gatto, P., Pettenella, D., Eds.; EFI Proceedings No. 55; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2008; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Advancement of Forest Village Communities Through Effective Participation and Partnership in State-Owned Forestry Administration; Türkiye’s Case; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2000; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/XII/0223-C1.htm (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Park, C.; Kleinschmit, D. Framing forest conservation in the global media: An interest-based approach. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 68, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritten, D.; Saastamoinen, O.; Sajama, S. Media coverage of forest conflicts: A reflection of the conflicts’ intensity and impact? Scand. J. For. Res. 2012, 27, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reconnect Europe. The Białowieża Case: A Tragedy in Six Acts. RECONNECT Policy Brief. 2020. Available online: https://reconnect-europe.eu/blog/the-bialowieza-case/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Nichiforel, L.; Deuffic, P.; Thorsen, B.J.; Weiss, G.; Hujala, T.; Keary, K.; Bouriaud, L. Two decades of forest-related legislation changes in European countries analysed from a property rights perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 115, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Stewardship Council. Bulgaria Joins the Global Network for Sustainable Forest Management. FSC News. 2020. Available online: https://fsc.org/en/newscentre/general-news/bulgaria-joins-the-global-network-for-sustainable-forest-management (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Cienciala, E. Climate-Smart Forestry Case Study: Czech Republic. In Forest Bioeconomy and Climate Change. Managing Forest Ecosystems; Hetemäki, L., Kangas, J., Peltola, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Development of Czech Forest Related Policy and Institutions on the Threshold of the Third Millennium; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2000; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/XII/0715-c2.htm (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Koulelis, P.P.; Tsiaras, S.; Andreopoulou, Z.S. Greece’s Forest Sector from the Perspective of Timber Production: Evolution or Decline? A Forest Policy Brief for Greece. MedForest. 2023. Available online: https://medforest.net/2023/12/05/a-forest-policy-brief-for-greece/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Tovima.com. Greece’s forests: Untapped Wealth or Wasted Potential? To Vima. 2024. Available online: https://www.tovima.com/science/greeces-forests-untapped-wealth-or-wasted-potential/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- European Commission. Türkiye 2021 Report. Commission Staff Working Document SWD (2021); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Atmiş, E. A critical review of the (potentially) negative impacts of current protected area policies on the nature conservation of forests in Türkiye. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, E.P.; Führer, E.; Ryan, D.; Andersson, F.; Hüttl, R.; Piussi, P. European forest ecosystems: Building the future on the legacy of the past. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 132, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.G.; Sinha, D.K.; Singh, D.K. Ecological concept. In Veterinary Public Health & Epidemiology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, A. Introduction to Ecology; University of Mysore: Mysore, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ignacimuthu, S. Environmental Studies; MJP Publisher: Chennai, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.; Packham, J. Ecology of Woodlands and Forests; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khaire, B.S.; Ganjure, R.S. Environmental Biology (Ecology); Xoffencer International Book Publication House: Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Udvardy, M.F. Notes on the ecological concepts of habitat, biotope and niche. Ecology 1959, 40, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J. The niche, biogeography and species interactions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2011, 366, 2336–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H.; Levin, S.A.; Root, R.B. Niche, habitat, and ecotope. Am. Nat. 1973, 107, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, R.F. Beyond Kyoto: Forest management in a time of rapid climate change. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, F.; Lamb, R.L. Biodiversity: Concept, measurement, and management. In Conservation Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 35–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tomalka, J.; Hunecke, C.; Murken, L.; Heckmann, T.; Cronauer, C.; Becker, R.; Collignon, Q.; Collins-Sowah, P.; Crawford, M.; Gloy, N. Stepping Back from the Precipice: Transforming Land Management to Stay Within Planetary Boundaries; Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK): Potsdam, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Soliveres, S.; Penone, C.; Manning, P.; van der Plas, F.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Ammer, C.; Schall, P.; Gossner, M.M. Multiple forest attributes underpin the supply of multiple ecosystem services. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, I. Challenges in delivering climate change policy through land use targets for afforestation and peatland restoration. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]