ALIVE: A New Protocol for Investigating the Modern Pollen Deposition of Italian Forest Communities and the Correlation with Their Species Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Recall the origins of modern pollen monitoring projects in Europe and the launch of the EPMP (Section 2);

- -

- Review the available literature and the procedures adopted by other scholars regarding fieldwork activities for modern pollen deposition monitoring and vegetation analysis (Section 2);

- -

- Propose a simple yet effective experimental design integrating vegetation surveys with modern pollen deposition monitoring, developed within the ALIVE “TrAcking Long-term declIne of forest biodiVErsity in Italy to support conservation actions” Project, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research in 2023 (details in Section 3). This design (Section 4) aims to address the critical gap in modern pollen databases, which often lack corresponding vegetation data, and to generate high-quality paired datasets suitable for refining pollen–vegetation models and improving palaeoecological reconstructions;

- -

- Describe the main results of the ALIVE Project and introduce a new database of modern pollen deposition and data on forest tree species across Italy (Section 5). These data, collected from a wide range of ecological and biogeographical settings, are intended to support pollen-vegetation calibration studies and palaeoenvironmental reconstructions. They also represent a significant contribution to the existing body of modern palynological data at both national and European scale.

2. Pollen Monitoring in Europe: A Literature Review

- (i)

- The number of mosses collected at each site varies (1, 3, 5, more than 10);

- (ii)

- Vegetation surrounding the traps is not always recorded, and when it is, no common protocol exists.

| Reference | Study Area | Sampled Ecosystems | Number of Mosses Sampled at Each Site | Vegetation Relevées |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | Western Norway | mown and grazed vegetation | Several (not specified), later analysed individually. | Within an area of 10 m2, five 1 m2 plot were surveyed. Vascular plants identified to the same taxonomic level as for pollen types. |

| [25] | Central Pyrenees (Spain) | montane, subalpine and alpine vegetation | 2–4 mosses collected in an area of ca. 10 m2 and then mixed into one sample. | Vegetation survey according to Braun-Blanquet (all plants) at the site and notes on the vegetation around the site. |

| [26] | Western Italian Alps | forest openings above/below the treeline | 1 | General description of the main vegetation type. |

| [27] | Western Amazonia | montane forests | Several (not specified), likely mixed in one sample. | Vegetation data from 15 permanent plots of 1 ha. |

| [28] | Cyprus | coastal/wetlands, orchards, garigue, maquis, forests | 15–20, mostly of surface soil, sometimes leaf litter and mosses. | Perennial plant species recorded over an area of about 100 m diameter. |

| [29] | transect across Finnish Lapland | from tundra-like open communities to boreal conifer forests | 1 | No site-specific relevées. General description of the vegetation zones encountered along the transect, with plant names (no cover). |

| [30] | Pechora-Ilych Nature Reserve (Russia) | pristine dark conifer forest | 1 | Detailed vegetation descriptions in a 1 m radius and at a 400 m2 scale. |

| [31] | Namibia | savannas | No mosses, instead surface soils. | Vegetation recorded following Braun-Blanquet (species list and plant cover). |

| [32] | Tibetan Plateau (China) | alpine meadows and grasslands, sub-alpine shrubs, patchy conifer and deciduous forests | 5 mosses later mixed in one sample. | Vegetation survey in each plot (list of vascular species and plant cover). |

| [33] | Northern China | conifer forest, deciduous forest, deciduous shrub, grass meadow, grass steppe, desert steppe and desert | 4–5 subsamples (moss pollsters, litter and topsoil) collected randomly within an area of ca. 50 m2 and mixed into one sample. | No site-specific relevées. Distinction of 7 vegetation types and list of the most frequent plants within each type. |

| [34] | Tagus Basin (Spain) | thermo-Mediterranean to oro-Mediterranean vegetation belt | Several moss fragments (usually 5) within a plot of ca. 20 × 20 m2, later homogenised in the lab. | Vegetation structure and composition recorded, especially for woody taxa. Local tree and (in some cases) shrub cover (%) were recorded. |

| [35] | Serra da Estrela (Portugal) | meso-Mediterranean cultural landscapes with pine plantations, supra-Mediterranean heathlands, oro-Mediterranean high-elevation grasslands | 1 | Abundance of vascular plants was surveyed in 1 m2. Up to 200 m away species were recorded using a ‘nearest individual’ method of plotless sampling. |

| [36] | Northern Greece | coastal meso-Mediterranean maquis, temperate and subalpine forests, alpine treeless vegetation | Not specified | Vegetation composition recorded within a 10 m2 plot, with a focus on woody species. Presence/absence and canopy cover recorded every m along two orthogonal 10 m long transects. |

- (a)

- Interdisciplinary nature of Palynology: Palynology lies at the interface between botany, ecology, geology, and archaeology. Not all palynologists are trained botanists with a strong background in plants identification, taxonomy, and vegetation ecology. Accurate vegetation surveys and plant identification require expertise and time, which not all teams possess, leading to inconsistent or missing vegetation data accompanying modern pollen samples.

- (b)

- Fieldwork constraints: Fieldwork is often limited by tight schedules, restricted funding, and logistical challenges, and it is therefore sometimes skipped or simplified.

- (c)

- Historical evolution of protocols: Modern pollen analysis protocols developed differently across countries. Early studies mostly focused on pollen itself rather than its vegetation context, so vegetation surveys were frequently not integrated.

- (d)

- Methodological challenges in vegetation description: Vegetation descriptions are difficult to standardise across ecosystems, making standard protocols challenging to enforce. In the absence of a central authority or standardised guidelines specific to modern pollen sampling and associated vegetation surveys, researchers often develop local or lab-specific methods.

3. The ALIVE Project: Establishing an Effective Protocol to Monitor Pollen Deposition in Forest Ecosystems

- (i)

- A survey of available pollen records from the last six millennia for the Italian Peninsula, to define the rates, patterns, timing, and modes of range shifts in the target taxa across the country;

- (ii)

- A comparison of past and current distribution of the target taxa using vegetation maps and new evidence on modern pollen deposition collected within the ALIVE project primarily through the analysis of moss polsters.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. The ALIVE Experimental Design for Field Data Collection

4.2. Moss Samples Lab Processing and Pollen Analysis

4.3. Pollen Distribution Mapping, Data Visualisation and Explorative Statistical Analysis

4.4. Spatial Modelling

5. Results

5.1. The New Dataset of Modern Pollen Deposition Sites for Italy

5.2. Overview of the ALIVE Dataset: Relationships Between Variables and Detrended Correspondence Analysis on the 20 Target Taxa

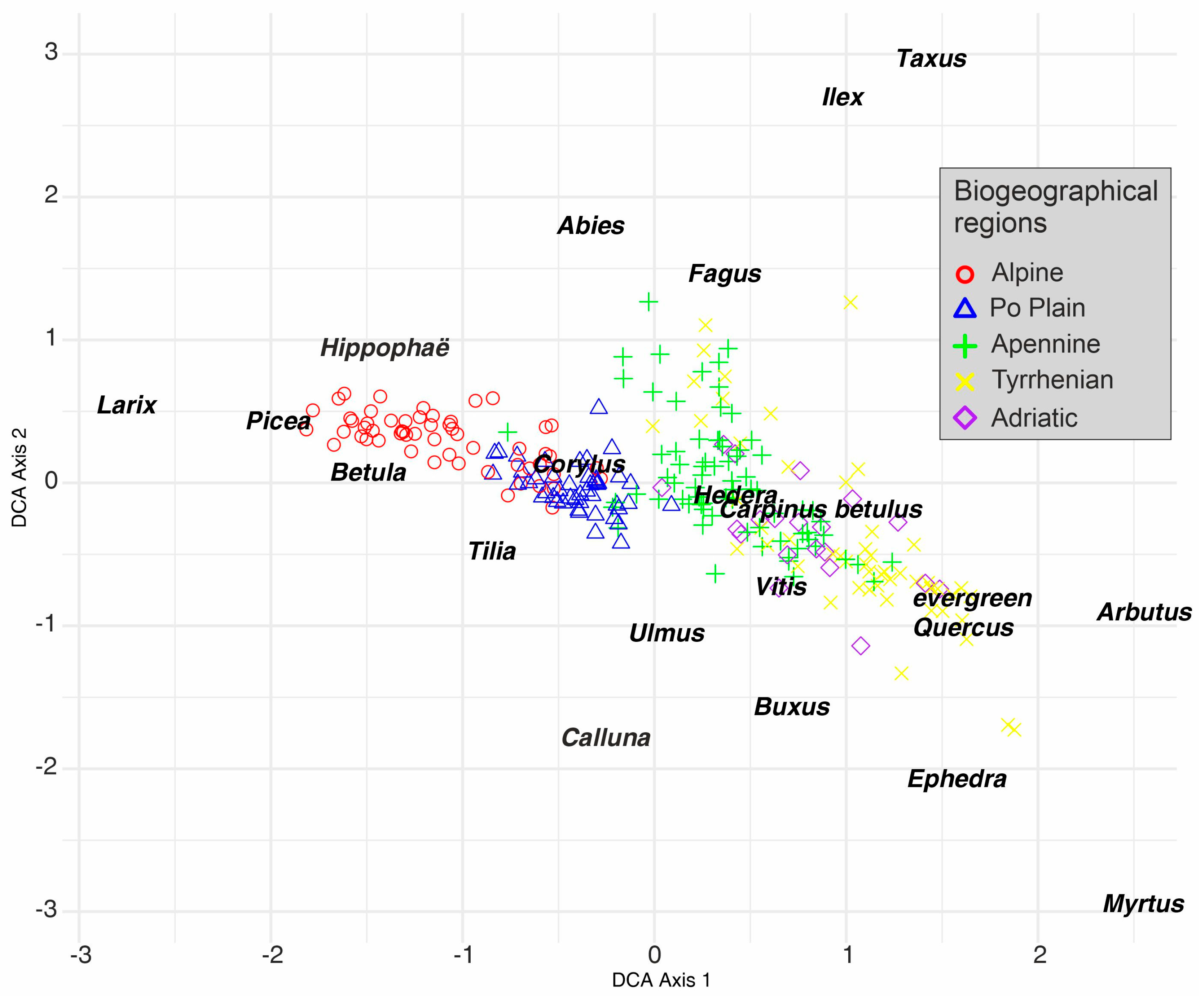

5.3. Overview of the ALIVE Dataset: Detrended Correspondence Analysis on the 20 Target Taxa

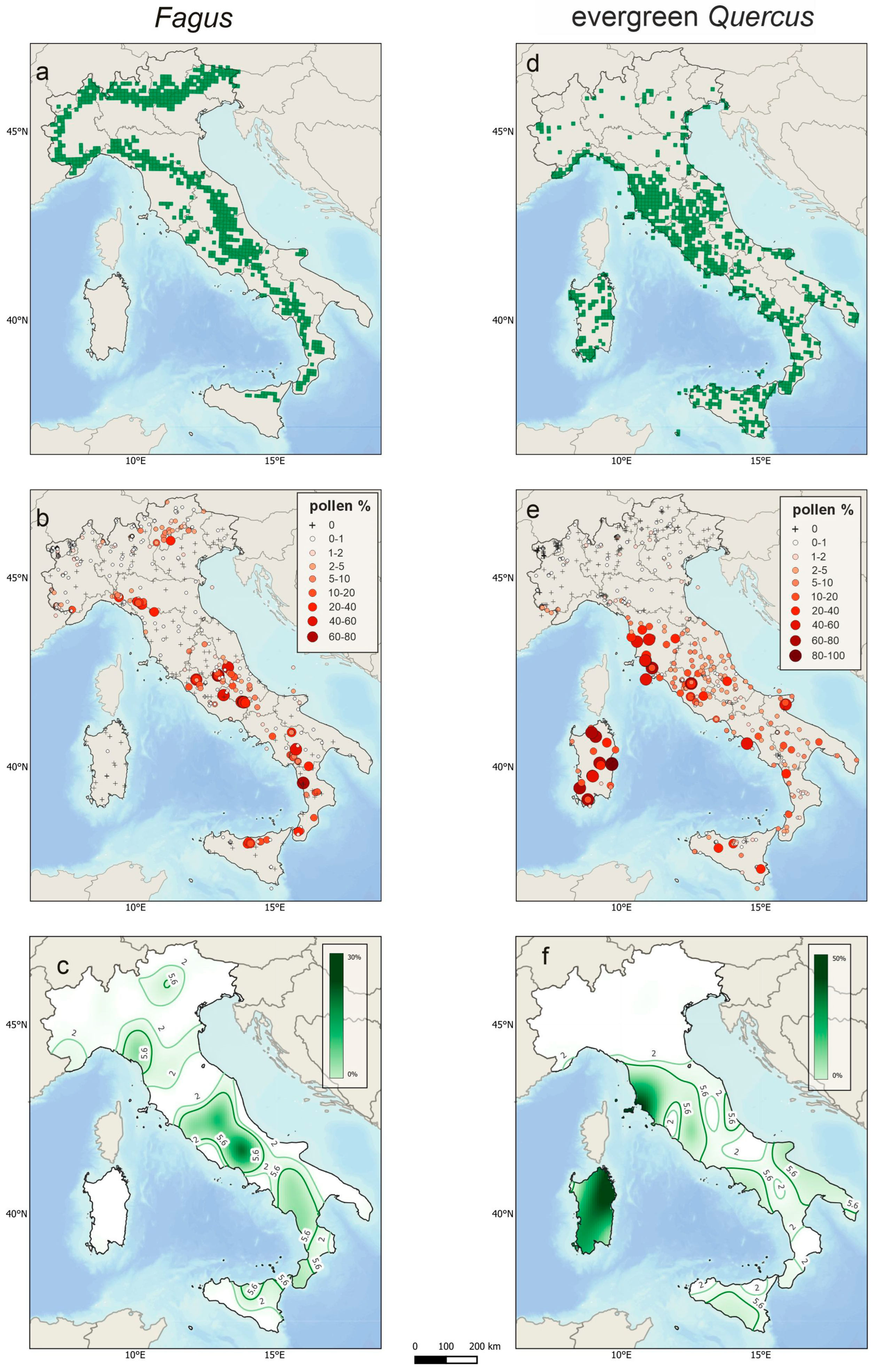

5.4. Occurrence Maps and Bayesian Modelling on Modern Pollen Deposition Data: An Example for Two Forest Tree Taxa (Fagus and Evergreen Quercus)

5.5. The ALIVE Database

6. Discussion

6.1. Progresses in Pollen Deposition Studies and Open Questions

- (i)

- Identify plants to the lowest possible taxonomical level. Once the species list is compiled, each plant name can be matched to its corresponding pollen morphological type harmonising the two taxonomies by downscaling the botanical one;

- (ii)

- Identify plants in the field according to pollen taxonomy (e.g., Poaceae, instead of individual grass species). This approach speeds up fieldwork and simplifies the comparison between pollen and vegetation, but inevitably results in the loss of detailed botanical information that could be valuable for future research.

6.2. Different Ways to Express the Pollen Concentration of Moss Samples

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

- -

- Estimating tree species density in forest ecosystems;

- -

- Exploring pollen dispersion patterns and identifying percentage thresholds for the local presence of forest taxa;

- -

- Developing transfer functions to model the relationship among modern pollen data, present-day vegetation, and climate variables, thereby supporting palaeoecological reconstructions;

- -

- Improving the statistical comparison between pollen and vegetation data through a more precise recording of plant cover, since Braun-Blanquet classes involve a degree of uncertainty, whereas pollen data are expressed as exact percentage values.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALIVE | acronym of the project “TrAcking Long-term declIne of forest biodiVErsity in Italy to support conservation actions” |

| EPMP | European Pollen Monitoring Programme |

| EMPD | Eurasian Modern Pollen Database |

References

- Prentice, I.C. Records of vegetation in time and space: The principles of pollen analysis. In Vegetation History; Book series “Handbook of vegetation Scienc”; Huntley, B., Webb, T., III, Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 7, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, H.H.; Birks, H.J.B.; Kaland, P.E.; Moe, D. The Cultural Landscape: Past, Present and Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, H.J.B.; Berglund, B.E. One hundred years of Quaternary pollen analysis 1916–2016. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2018, 27, 271–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, H.J.B.; Felde, V.A.; Bjune, A.E.; Grytnes, J.-A.; Seppä, H.; Giesecke, T. Does pollen-assemblage richness reflect floristic richness? A review of recent developments and future challenges. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2016, 228, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, W.D.; Julier, A.C.M.; Adu-Bredu, S.; Diagbletey, G.D.; Fraser, W.T.; Jardine, P.E.; Lomax, B.H.; Malhi, Y.; Manu, E.A.; Mayle, F.E.; et al. Pollen-vegetation richness and diversity relationships in the tropics. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2018, 27, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, V.; Hicks, S.; Svobodová-Svitavská, H.; Bozilova, E.; Panajiotidis, S.; Filipova-Marinova, M.; Jensen, C.E.; Tonkov, S.; Pidek, I.A.; Święta-Musznicka, J.; et al. Patterns in recent and Holocene pollen accumulation rates across Europe—the Pollen Monitoring Programme Database as a tool for vegetation reconstruction. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 4511–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novenko, E.; Mazei, N.; Shatunov, A.; Chepurnaya, A.; Borodina, K.; Korets, M.; Prokushkin, A.; Kirdyanov, A.V. Modern Pollen–Vegetation Relationships: A View from the Larch Forests of Central Siberia. Land 2024, 13, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLauchlan, K.K.; Barnes, C.S.; Craine, J.M. Interannual variability of pollen productivity and transport in mid-North America from 1997 to 2009. Aerobiologia 2011, 27, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.T.; Lyford, M.E. Pollen dispersal models in Quaternary plant ecology: Assumptions, parameters, and prescriptions. Bot. Rev. 1999, 65, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Møller, P.F.; Giesecke, T.; Stavngaard, B.; Fontana, S.L.; Bradshaw, R.H.W. The effect of climate conditions on inter-annual flowering variability monitored by pollen traps below the canopy in Draved Forest, Denmark. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2010, 19, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhu, L.; Ju, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Haberzettl, T. A modern pollen dataset from lake surface sediments on the central and western Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.D. Quaternary pollen taphonomy: Examples of differential redeposition and differential preservation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 1999, 149, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.S. Chapter 12. Paleoclimatology. Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 405–451. [Google Scholar]

- Pardoe, H.S.; Giesecke, T.; van der Knaap, W.O.; Svitavská-Svobodová, H.; Kvavadze, E.V.; Panajiotidis, S.; Gerasimidis, A.; Pidek, I.A.; Zimny, M.; Święta-Musznicka, J.; et al. Comparing pollen spectra from modified Tauber traps and moss samples: Examples from a selection of woodland across Europe. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2010, 19, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, P.R. The use of mosses in modern pollen studies at Morton Lochs—Fife. Bot. Soc. Edinb. Trans. 1985, 44, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.; Hyvärinen, V.-P. Sampling modern pollen deposition by means of ‘Tauber Traps’: Some considerations. Pollen Et. Spores 1986, 28, 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, P.T.; Kershaw, A.P.; Grindrod, J. Pollen transport and deposition in riverine and marine environments within the humid tropics of northeastern Australia. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2005, 134, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razafimanantsoa, A.H.I.; Razanatsoa, E. Modern pollen rain reveals differences across forests, open and mosaic landscapes in Madagascar. Plants People Planet. 2024, 6, 729–742. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, A.; Paciorek, C.J.; McLachlan, J.S.; Goring, S.; Williams, J.W.; Jackson, S.T. Quantifying pollen-vegetation relationships to reconstruct ancient forests using 19th-century forest composition and pollen data. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 137, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.A.S.; Zanon, M.; Collins, P.; Mauri, A.; Bakker, J.; Barboni, D.; Barthelmes, A.; Beaudouin, C.; Bjune, A.E.; Bozilova, E.; et al. The European Modern Pollen Database (EMPD) project. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2013, 22, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.; Ammann, B.; Latalowa, M.; Pardoe, H.; Tinsley, H. European Pollen Monitoring Programme. Project Description and Guidelines; Oulu University Press: Oulu, Finland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber, H. A static non-overload pollen collector. New Phytol. 1974, 73, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.; Tinsley, H.; Pardoe, H.; Cundill, P. European Pollen Monitoring Programme. Supplement to the Guidelines; Oulu University Press: Oulu, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle, K.L. Use of Modern Pollen Samples and Estimated Pollen Representation Factors as Aids in the Interpretation of Cultural Activity in Local Pollen Diagrams. Nor. Archaeol. Rev. 1999, 32, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañellas-Boltà, N.; Rull, V.; Vigo, J.; Mercadé, A. Modern pollen--vegetation relationships along an altitudinal transect in the central Pyrenees (southwestern Europe). Holocene 2009, 19, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortu, E.; Klotz, S.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Caramiello, R.; Siniscalco, C. Elevation-induced variations of pollen assemblages in the North-western Alps: An analysis of their value as temperature indicators. CR Biol. 2010, 333, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrego, D.H.; Silman, M.R.; Correa Metrio, A.; Bush, M.B. Pollen-vegetation relationships along steep climatic gradients in western Amazonia. J. Veg. Sci. 2011, 22, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, P.L. Modern vegetation, pollen and climate relationships on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2012, 185, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisitsyna, O.V.; Hicks, S. Estimation of pollen deposition time-span in moss polsters with the aid of annual pollen accumulation values from pollen traps. Grana 2014, 53, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisitsyna, O.V.; Smirnov, N.S.; Aleynikov, A.A. Modern pollen data from pristine taiga forest of Pechora-Ilych state nature biosphere reserve (Komi republic, Russia): First results. Ecol. Quest. 2017, 26, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, X.; Mapani, B.; Blaumb, N.; Herzschuh, U. Composition and diversity of vegetation and pollen spectra along gradients of grazing intensity and precipitation in southern Africa. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2018, 253, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Duo, L.; Pang, Y.-Z.; Felde, V.A.; Birks, H.H.; Birks, H.J.B. Modern pollen assemblages and their relationships to vegetation and climate in the Lhasa Valley, Tibetan Plateau, China. Quat. Int. 2018, 467, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Mab, Y.; Li, D.; Pei, Q. Modern pollen and its relationship with vegetation and climate in the Mu Us Desert and surrounding area, northern China: Implications of palaeoclimatic and palaeocological reconstruction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2020, 547, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Molino, C.; Devaux, L.; Georget, M.; Hanquiez, V.; Sánchez Goñi, M.F. Modern pollen representation of the vegetation of the Tagus Basin (central Iberian Peninsula). Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2020, 276, 104193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, S.E.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; van der Knaap, W.O.; Akindola, R.B.; Adeleye, M.A.; Mariani, M. Pollen and plant diversity relationships in a Mediterranean montane area. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2021, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, C.; Tinner, W.; Felde, V.A.; Gobet, E.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Morales-Molino, C. Modern pollen—Vegetation—Plant diversity relationships across large environmental gradients in northern Greece. Holocene 2022, 32, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmarr, J. Tablets with spores used in absolute pollen analysis. Pollen Et Spores 1971, XIII, 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Erdtman, H. The acetolysis method. A revised description. Sven. Bot. Tidskr. 1960, 54, 561–564. [Google Scholar]

- Faegri, K.; Iversen, J.; Kaland, P.E.; Krzywinski, K. Textbook of Pollen Analysis; Blackburn Press: Caldwell, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, P.D.; Webb, J.A.; Collison, M.E. Pollen Analysis, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K.D.; Willis, K.J. Pollen. In Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Magri, D.; Di Rita, F. Archaeopalynological Preparation Techniques. In Plant Microtechniques and Protocols; Yeung, E.C.T., Stasolla, C., Sumner, M.J., Huang, B.Q., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 495–506. [Google Scholar]

- Reille, M. Pollen et Spores d’Europe et d’Afrique du nord; Jerome, S., Ed.; Université de Marseille: Marseille, France, 1992; Volume 1 + Suppl. I–II. [Google Scholar]

- Beug, H.J. Leitfaden der Pollenbestimmung für Mitteleuropa und Angrenzende Gebiete; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: München, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, B.A.S.; Chevalier, M.; Sommer, P.; Carter, V.A.; Finsinger, W.; Mauri, A.; Phelps, L.N.; Zanon, M.; Abegglen, R.; Åkesson, C.M.; et al. The Eurasian Modern Pollen database (EMPD), Version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 12, 2423–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.W.; Grimm, E.C.; Blois, J.L.; Charles, D.F.; Davis, E.B.; Goring, S.J.; Graham, R.W.; Smith, A.J.; Anderson, M.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; et al. The Neotoma Paleoecology Database, a Multiproxy, International, Community-Curated Data Resource. Quat. Res. 2018, 89, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.7-1. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Donato, G.; Belongie, S. Approximate Thin Plate Spline Mappings. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2002; Heyden, A., Sparr, G., Nielsen, M., Johansen, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2352, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N. Thin Plate Regression Splines. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2003, 65, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Fernandes, R.; DSSM: Pandora IsoMemo Spatiotemporal Modeling. R Package Version 25.06.1. 2025. Available online: https://pandora-isomemo.github.io/DSSM/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Lisitsyna, O.V.; Giesecke, T.; Hicks, S. Exploring Pollen Percentage Threshold Values as an Indication for the Regional Presence of Major European Trees. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2011, 166, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrillo, E.; Alessi, N.; Massimi, M.; Spada, F.; De Sanctis, M. Nationwide Vegetation Plot Database—Sapienza University of Rome: State of the Art, Basic Figures and Future Perspectives. Phytocoenologia 2017, 47, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimidis, A.; Panajiotidis, S.; Hicks, S.; Athanasiadis, N. An eight-year record of pollen deposition in the Pieria mountains (N. Greece) and its significance for interpreting fossil pollen assemblages. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2006, 141, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Broström, A.; Nielsen, A.B.; Gaillard, M.-J.; Sugita, S. Pollen productivity estimates of key European plant taxa for quantitative reconstruction of past vegetation. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2008, 17, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjogren, P.; van der Knaap, W.O.; Huusko, A.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N. Pollen productivity, dispersal, and correction factors for major tree taxa in the Swiss Alps based on pollen-trap results. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2008, 152, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poska, A.; Pidek, I.A. Pollen dispersal and deposition characteristics of Abies alba, Fagus sylvatica and Pinus sylvestris, Roztocze region (SE Poland). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2010, 19, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M.; Okabe, T. Vegetation mapping with the aid of Low-Altitude aerial photography. Appl. Veg. Sci. 1998, 1, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, H.; Morisada, S.; Ogawa, M.; Kawada, M. Vegetation mapping with the aid of aerial images taken by UAV with a near-infrared sensor. Landsc. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 25, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Quercus ilex in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. Eur. Atlas For. Tree Species 2016, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zechmeister, H.G. Annual growth of four Pleurocarpus moss species and their applicability for biomonitoring heavy metals. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1998, 52, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaeva, O.V.; Shmakova, N.Y.; Lukyanova, L.M. On the growth of Polytrichum, Pleurozium and Hylocomium in the forest belt of the Khibini Mountains. Arctoa 2013, 22, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Varela, Z.; Real, C.; Branquinho, C.; Afonso do Paço, T.; Cruz de Carvalho, R. Optimizing artificial moss growth for environmental studies in the Mediterranean area. Plants 2021, 10, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name and Provenance | Pollen Grains Counted, Lycopodium Spores Added/Counted | Sample Weight, Volume, TOC vs. Weight and Volume | Pollen Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larix M3_2m Mount Spundascia (Central Italian Alps) | Pollen sum: 1001 grains | moss weight: 2.6 g | 102,797 grains/g |

| Lycopodium spores added: 13,761 | moss volume: 12 cm3 | 17,133 grains/cm3 | |

| Lycopodium spores counted: 67 | moss total organic content: 0.1872 g | 1,177,129 grains/g of total organic matter | |

| moss total organic content: 0.0678 cm3 | 3,030,084 grains/cm3 of total organic matter |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pini, R.; Bertuletti, P.; Caucci, L.; Celant, A.; De Luca, E.; De Santis, S.; Ferigato, L.; Fontana, V.; Furlanetto, G.; Magri, D.; et al. ALIVE: A New Protocol for Investigating the Modern Pollen Deposition of Italian Forest Communities and the Correlation with Their Species Composition. Forests 2025, 16, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111722

Pini R, Bertuletti P, Caucci L, Celant A, De Luca E, De Santis S, Ferigato L, Fontana V, Furlanetto G, Magri D, et al. ALIVE: A New Protocol for Investigating the Modern Pollen Deposition of Italian Forest Communities and the Correlation with Their Species Composition. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111722

Chicago/Turabian StylePini, Roberta, Paolo Bertuletti, Lorenzo Caucci, Alessandra Celant, Elisa De Luca, Simone De Santis, Laura Ferigato, Valentina Fontana, Giulia Furlanetto, Donatella Magri, and et al. 2025. "ALIVE: A New Protocol for Investigating the Modern Pollen Deposition of Italian Forest Communities and the Correlation with Their Species Composition" Forests 16, no. 11: 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111722

APA StylePini, R., Bertuletti, P., Caucci, L., Celant, A., De Luca, E., De Santis, S., Ferigato, L., Fontana, V., Furlanetto, G., Magri, D., Michelangeli, F., & Di Rita, F. (2025). ALIVE: A New Protocol for Investigating the Modern Pollen Deposition of Italian Forest Communities and the Correlation with Their Species Composition. Forests, 16(11), 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111722