Abstract

Populus adenopoda, an endemic tree species in China with considerable ecological and industrial value, is threatened by climate change-induced habitat loss. Understanding its spatial response is critical for conservation. This study employed the MaxEnt model with 181 occurrence records and seven environmental variables to project its current and future suitable habitats under multiple climate scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, SSP585 for the 2050s and 2090s). The model exhibited high predictive performance (AUC = 0.947 and TSS = 0.817). Annual precipitation and the minimum temperature of the coldest month were the dominant factors shaping its distribution. Currently, the total suitable habitat spans approximately 228.19 × 104 km2, predominantly in subtropical China. Future projections consistently revealed a stark degradation of highly suitable habitat, with losses of up to 78.81% under SSP585 by the 2090s, partially offset by an expansion of low-suitability areas. A pronounced northwestward shift of the habitat centroid indicates a potential migration toward higher elevations. These results provide a critical scientific foundation for developing climate-adaptive conservation strategies, including identifying priority areas and planning assisted migration, to ensure the long-term sustainability of P. adenopoda.

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change, manifested primarily through alterations in temperature and precipitation regimes [1], poses a fundamental threat to global forest ecosystems [2]. It profoundly alters the distribution, composition, and structure of tree species worldwide [3], directly impacting their survival, growth, and regeneration [4]. These changes can lead to significant range shifts, habitat fragmentation, and biodiversity loss, jeopardizing ecosystem services and threatening the economic sustainability of forest-dependent industries [5]. Understanding and predicting species’ range shifts in response to these changing climatic conditions is therefore a cornerstone of proactive forest ecology and management. This is particularly crucial for economically important tree species, as their spatial suitability directly influences timber production, carbon sequestration potential, and biodiversity conservation strategies [6,7].

Populus adenopoda a fast-growing deciduous tree endemic to China, is a species of significant ecological and economic value [8]. Ecologically, it serves as a pioneer species crucial for ecosystem restoration and plays a key role in riparian ecosystems. Economically, it is a vital source of timber widely used in afforestation, pulp and paper production, and wood-based panel industries [9,10]. Its distribution is primarily confined to the mountainous areas of southern China, and its productivity is highly sensitive to climatic conditions, particularly minimum winter temperatures and annual precipitation. Given this limited natural range and specific habitat requirements, P. adenopoda is considered highly vulnerable to the anticipated effects of climate change. However, the precise impacts on its spatial distribution and habitat quality remain quantitatively unclear. Furthermore, a comprehensive assessment using the latest CMIP6 global climate scenarios is notably lacking, and the uncertainty inherent in such regional distribution models underscores the need for studies that can inform future field validation efforts [11,12]. This knowledge gap significantly hinders the development of effective, long-term conservation and sustainable management strategies for this valuable species.

Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in several key ecological theories that directly inform our hypotheses, model structure, and interpretation of results. First, the concept of the ecological niche [13,14], particularly the Grinnellian niche [15,16] defined by large-scale abiotic conditions, provides the foundational premise that a species’ distribution is constrained by a suite of environmental variables [17,18]. This theory justifies the use of Species Distribution Models (SDMs) and guides our selection of macroclimatic predictors to define the potential range of P. adenopoda.

Second, theories of species tolerance and stress [19] suggest that distribution limits are primarily set by physiological thresholds to climatic extremes (e.g., minimum winter temperature, drought) rather than averages [20]. This critically shaped our a priori selection of bioclimatic variables, leading us to prioritize those representing critical limiting factors for a temperate deciduous tree, such as temperature of the coldest month and precipitation seasonality.

Furthermore, the framework of ecosystem resilience and replenishment [21,22] underpins our interpretation of how a pioneer species like P. adenopoda might respond to rapid change. The concept of resilience informs our analysis of potential future refugia-areas that may remain suitable and act as reservoirs for population persistence. The concept of replenishment, through natural or assisted migration, guides our discussion on management strategies to compensate for habitat loss in other parts of its range.

Finally, we adopt a “driver-response” model of climate impact [23], wherein projected changes in macroclimatic variables (the drivers) are hypothesized to directly elicit a spatial response in the species’ distribution of suitable habitat. This causal framework structures our entire analytical approach, from model projection to the assessment of range shifts and habitat contraction.

Collectively, these theories shape our central hypothesis: that future climate change will act as a primary environmental driver, pushing the distribution of P. adenopoda beyond its current climatic tolerance limits, thereby resulting in measurable range shifts, the degradation of core habitats (a loss of resilience), and a contraction in its overall suitable area.

Species Distribution Models (SDMs) are pivotal for anticipating species responses to climate change [24], offering critical insights for proactive forest management and conservation planning [25,26,27,28]. The Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model, renowned for its efficacy with presence-only data, has been extensively employed to project distributional shifts of numerous tree species under future climates [27,29,30,31]. Previous studies have consistently predicted potential range contractions, expansions, and altitudinal migrations for various forest trees [32,33]. However, many of these applications remain focused on predicting binary (suitable vs. unsuitable) habitat changes, which provides limited guidance for practical management. A more nuanced assessment-one that quantifies gradients of habitat suitability, identifies potential degradation of core habitats, and tracks directional shifts in distribution centroids-is essential to formulate targeted and effective conservation strategies [11,34,35]. Yet, a comprehensive evaluation of this nature is notably lacking for P. adenopoda, particularly one that incorporates the latest CMIP6 global climate scenarios. This gap constrains our ability to develop robust strategies for the preservation and sustainable management of this ecologically and economically significant tree species.

Therefore, this study aims to (1) identify the dominant environmental factors limiting the current distribution of P. adenopoda; (2) model and quantify the changes in its suitable habitat area and spatial pattern under both current and future (CMIP6 scenarios) climate conditions; and (3) critically evaluate the degradation of highly suitable habitat and the trajectory of distribution centroid shifts. Our findings will yield spatially explicit projection maps and precise ecological thresholds for P. adenopoda. Ultimately, this research is designed to provide a scientific basis for establishing conservation priorities, guiding assisted migration efforts, and formulating climate-adaptive management strategies to ensure the persistence and sustainable use of this economically important forest resource.

2. Materials and Methods

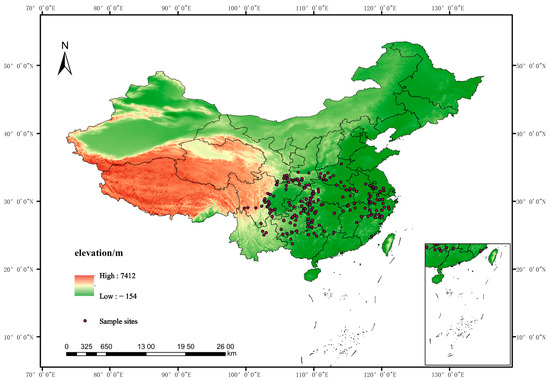

2.1. Collection and Screening of Distributed Data

Occurrence data for Populus adenopoda were compiled from two sources: the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, http://www.gbif.org/) and georeferenced specimen records from our laboratory collection. The initial dataset was rigorously cleaned to minimize common errors in biodiversity databases. Records with coordinate inaccuracies (e.g., located in oceans or urban centers) or those outside the species’ accepted natural range were manually removed. This step was crucial for eliminating gross errors and spatial biases. To mitigate spatial clustering bias, the remaining records were spatially thinned using ENMTools V3.1.2. This thinning procedure ensures that the model captures the broader environmental envelope of the species rather than fine-scale sampling artifacts, thereby improving model transferability. This process retained only the single occurrence point closest to the center within each 2.5 arc-min grid cell, ensuring a minimum distance of approximately 5 km between points [36,37]. This final set of 181 unique presence records (Figure 1) was used for model training and validation.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the occurrence records for Populus adenopoda. The 181 final occurrence points were obtained from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and georeferenced specimens from our laboratory collection, which were cleaned and deduplicated.

2.2. Environmental Variables

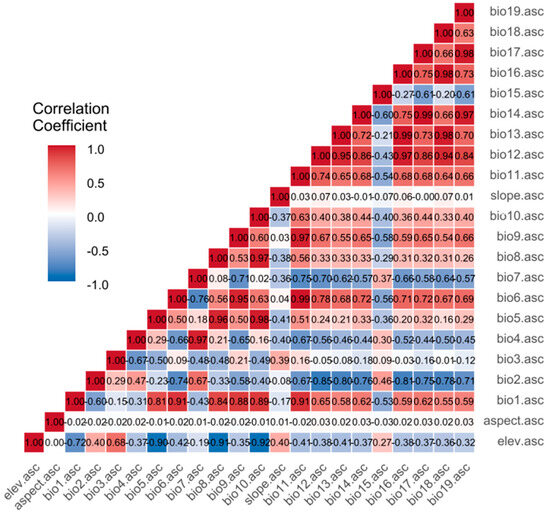

The environmental variables consist of 19 biogenic and 3 topographic factors (Table A1). Climate data were used for both the current period (1970–2000) and future periods (2041–2060, 2081–2100) under four representative concentration pathways (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, SSP585), covering nine climate scenarios in total. All climate data were obtained from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org) at a spatial resolution of 2.5 arc-mins [38]. WorldClim was selected as it provides a globally consistent, long-term climatology that is specifically tailored for species distribution modeling studies. While satellite-derived products (e.g., MODIS) offer finer spatial resolution, WorldClim’s interpolation from meteorological stations provides a more direct measure of the climatic conditions experienced by terrestrial plants over a multi-decadal period, which is critical for understanding species’ fundamental niches. The BCC-CSM2-MR climate model from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) was selected because it accurately captures historical climate patterns across China [39]. Topographic data, specifically digital elevation models (DEMs) at a 2.5 arc-min resolution, were sourced from WorldClim version 2.1. Slope and aspect were calculated from these DEMs. Using ArcGIS version 10.8.2, all environmental layers were masked and extracted to match China’s boundaries based on the administrative map. These raster layers were then converted into ASCII format for further analysis. We acknowledge that the ~2.5 arc-min spatial resolution, while standard for range-wide studies, may not capture fine-scale topographic microclimates, and the interpolative nature of the dataset introduces inherent uncertainties. The provincial administrative map of China was downloaded from the National Geomatics Center of China (http://ngcc.sbsm.gov.cn/). To reduce multicollinearity and avoid model overfitting [40], Pearson correlation coefficients among the 19 bioclimatic variables and three topographical variables were calculated with ENMTools (Figure 2). When the absolute correlation coefficient between two variables exceeded 0.8, they were considered highly correlated. The variable with the higher contribution was kept for further analysis [41,42]. This variable selection process is essential to ensure model stability and enhance the ecological interpretability of the results by preventing the influence of redundant predictors. Ultimately, seven environmental variables were selected for subsequent studies (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Correlation heatmap of the 22 environmental variables used for modeling. The matrix includes 19 bioclimatic and 3 topographic factors sourced from the WorldClim database, and displays their pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients (r). Variables strongly correlated (|r| > 0.8) were excluded from subsequent modeling to avoid multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Contribution of the key environmental variables to the MaxEnt model for Populus adenopoda. Variable importance is quantified by its percent contribution to the model and its permutation importance. Climate data (bio-climates) and topographic data (elev, slope, aspect) were sourced from WorldClim 2.1.

2.3. Construction and Evaluation of Species Distribution Model

The Maximum Entropy modeling algorithm (MaxEnt, version 3.4.4) was selected for this study due to its proven efficacy with presence-only species occurrence data, its ability to model complex non-linear relationships between species and environment, and its production of a continuous, interpretable habitat suitability index. These characteristics make it superior for our purposes compared to simpler regression models (which may not capture complexity) or other machine learning models (which can be less interpretable and often require absence data). The model was configured with regularization to prevent overfitting. Distribution data of P. adenopoda along with the seven selected environmental variables were imported into MaxEnt in csv format for model construction. The parameters were configured as follows: 75% of the occurrences were randomly allocated to the training dataset and the remaining 25% to the test dataset [43,44]. Bootstrap was selected as the sampling replication method to ensure equal probability of selection across iterations. The maximum number of iterations was set to 1000, and the model was run with 10 replicates. The bootstrap replication method was chosen as it provides a robust estimate of model uncertainty by repeatedly sampling the occurrence data with replacement. The output format was set to logistic. The contribution rates of environmental factors were analyzed using the jackknife test [37,44]. In MaxEnt model predictions, the contribution rate of each environmental factor is commonly used to indicate its relative importance, with a higher value denoting a greater contribution of the factor to the modeling outcome. The accuracy of the MaxEnt model was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) and the true skill statistic (TSS). The AUC value ranges from 0 to 1.0, where a model is considered to have good predictive performance when 0.8 < AUC ≤ 0.9, and excellent predictive performance when 0.9 < AUC ≤ 1.0 [45,46]. Model performance was also evaluated using the TSS, which ranges from −1 to +1. Values of 0, −1, and +1 correspond to random prediction, performance worse than random, and perfect agreement, respectively. The TSS effectively balances model sensitivity and specificity, with values exceeding 0.8 indicating excellent performance [47,48].

2.4. Classification of Suitable Habitat and Calculation of Centroid Migration

The continuous habitat suitability surface (asc format) generated by MaxEnt was imported into ArcGIS 10.8. We reclassified the suitability index into four distinct grades using the Jenks Natural Breaks Classification Method in the Reclassify tool. This method was selected as it optimally arranges continuous data by minimizing within-class variance and maximizing between-class variance, thereby identifying intrinsic, ecologically meaningful groupings in the probability data, as opposed to arbitrary divisions created by equal interval or quantile methods. The resulting suitability grades were defined as: poorly suitable habitat (<0.08), lowly suitable habitat (0.08–0.27), moderately suitable habitat (0.27–0.46), and highly suitable habitat (0.46–1.0). These threshold intervals, derived from the current distribution data, were then consistently applied to reclassify the suitability maps under all future scenarios to ensure comparability. Finally, the areal extent of each suitability grade was calculated using the ArcGIS Zonal Statistics tool.

The probability of the existence of P. adenopula ≥ 0.08 was considered the suitable habitat, and the probability of the existence of P. adenopula ≤ 0.08 was defined as the unsuitable habitat. To investigate the dynamic shifts in the suitable habitat of P. adenopula, we employed a two-pronged analytical approach using the SDMToolbox in ArcGIS, which included Habitat Change Overlay Analysis and Centroid Movement Analysis. First, the continuous habitat suitability maps were converted into binary (suitable/unsuitable) layers using the classification thresholds derived from the Jenks Natural Breaks method [15,30]. These binary layers for two time periods (e.g., current vs. future) were then used as inputs for the following analyses:

Habitat Change Overlay Analysis (Range Change Analysis): To quantitatively assess the changes in habitat area-a standard approach in species distribution modeling studies-we conducted a spatial overlay of the binary layers. This pixel-by-pixel comparison quantified the areal extent of three distinct dynamic categories:

- Habitat Expansion: Area suitable only in the future period.

- Habitat Contraction: Area suitable only in the current period.

- Unchanged Habitat: Area suitable in both periods.

The results of this analysis, representing the magnitude of habitat gain, loss, and stability, are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Areal extent of suitable habitats for Populus adenopoda under current and future climates (×104 km2). The table shows the area of poorly, moderately, and highly suitability classes, and the total suitable area for the baseline period, 2050s, and 2090s under four SSP scenarios.

Table 3.

Changes in the area of suitable habitat for Populus adenopoda under future climate scenarios (unit: ×104 km2). The table shows the projected gains, losses, and stable areas for total habitat and for each suitability class (poorly, moderate, highly) in the 2050s and 2090s across four SSP scenarios, compared to the current baseline.

Centroid Movement Analysis: To complement the area-based assessment and understand the directional shift of the distribution core, we calculated the geographical centroid (the mean center) of the suitable habitat area for each time period. The centroid, representing the spatial ‘center of mass’ of the distribution, was computed as the average X-coordinate and the average Y-coordinate of all pixels classified as suitable habitat. The “Centroid Changes (Lines)” tool in the SDMToolbox was then used to generate a vector line connecting the centroids from the current to the future period.

The Euclidean distance of this line provides a synthesized measure of the overall shift intensity of the species’ suitable habitat core. The direction (bearing) of this vector reveals the spatial trajectory (e.g., northward, upward) of the distribution shift. It is important to note that the centroid movement is an integrated metric reflecting the net effect of concurrent habitat expansion and contraction. For instance, a pronounced northward shift could result from substantial habitat loss in the southern part of the range and/or significant habitat gain in the northern part. Therefore, the results of this analysis are interpreted in conjunction with the Habitat Change Overlay Analysis to obtain a comprehensive understanding of both the magnitude and spatial pattern of habitat dynamics.

3. Results

3.1. Model Optimization Results and Accuracy Evaluation

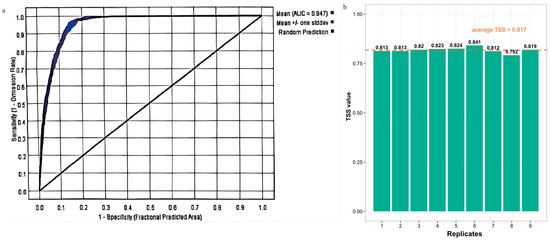

The ROC curve and the area under the curve (AUC) are metrics used to evaluate predictive accuracy. Generally, an AUC value within (0.9, 1.0] indicates excellent prediction. The model obtained from MaxEnt after 10 replicate runs, achieved an average AUC value of 0.947 (standard deviation = ±0.004, range = 0.941–0.951), and the average TSS value is 0.817, these results show that the model has an excellent and highly consistent predictive performance (Figure 3). This indicates that the model provides a robust and reliable simulation of the potential distribution of P. adenopoda in China.

Figure 3.

Predictive performance of the Populus adenopoda distribution model. (a) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve with Area Under the Curve (AUC) value. (b) True Skill Statistic (TSS) values from 10 bootstrap replicates (mean = 0.817). Both metrics confirm high model accuracy.

3.2. Environmental Variables Contribution

To robustly evaluate the contributions of the environmental variables, we prioritized the permutation importance metric for interpretation, as it is less sensitive to correlated predictors. The percent contribution is provided as supplementary data regarding the model-building process in Table 1.

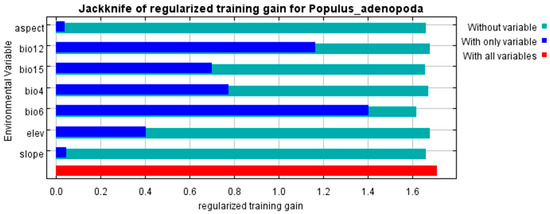

The results revealed that the distribution of P. adenopoda was predominantly constrained by thermal factors. Bio6 (min temperature of the coldest month) emerged as the most critical predictor with the highest permutation importance (52.4%). Although bio12 (annual precipitation) accounted for the largest share of the model’s percent contribution (42.0%), its permutation importance (16.5%) confirmed it as a secondary, albeit significant, factor. Another temperature-related variable, bio4 (temperature seasonality), also held a moderate yet relevant role (permutation importance: 15.2%). A notable discrepancy was observed for elevation, which demonstrated a high permutation importance (14.2%) despite a low percent contribution (2.1%), highlighting its strong independent predictive power. The effects of slope, bio15 (precipitation seasonality), and aspect were minimal.

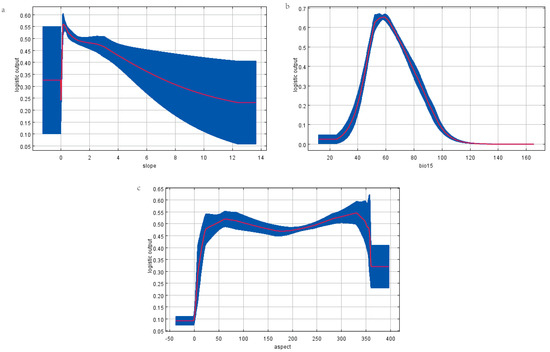

3.3. Relationship Between Distribution Probability and Dominant Environmental Factors

Through an analysis of the jackknife test (Figure 4), percent contribution, and permutation importance, we identified four dominant habitat factors for P. adenopoda based on a hierarchical criterion that prioritized permutation importance due to its robustness. The final selection comprised variables that ranked within the top four in permutation importance and were consistently supported by the other two metrics.

Figure 4.

Assessment of environmental variable importance using the Jackknife test in the MaxEnt model. The analysis shows the model gain when each variable is used in isolation (blue bars), the model gain when each variable is omitted (green bars), and the model gain using all variables (red bar).

The selected variables were: bio6 (min temperature of the coldest month), which was the most important variable across all three metrics; bio4 (temperature seasonality), ranking second in permutation importance; elev (elevation), ranking third in permutation importance; and bio12 (annual precipitation), which, despite a lower rank in permutation importance (fourth), was consistently among the top factors in both percent contribution (second) and jackknife training gain (second). This consensus confirms their collective dominance in shaping the species’ distribution.

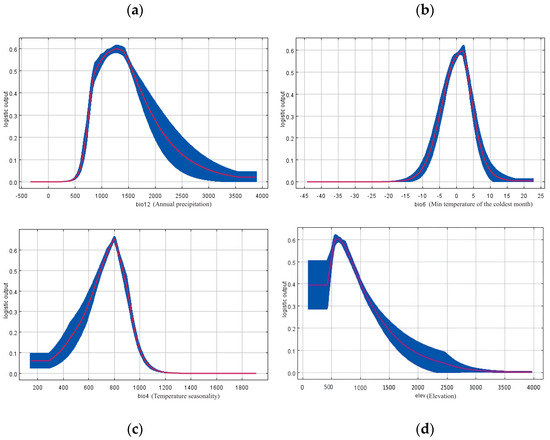

The response curves for these four dominant factors are presented in Figure 5. Response curves for the remaining variables (bio15, slope, aspect), which exhibited lower and less consistent importance across the different metrics, are provided in the Appendix A (Figure A1).

Figure 5.

Response curves of Populus adenopoda to the four most influential environmental variables identified by the MaxEnt model. The curves depict the predicted probability of presence as a function of changes in (a) Annual Precipitation (bio12), (b) Mean Temperature of the Coldest Quarter (bio6), (c) Temperature Seasonality (bio4), and (d) Elevation. These curves represent the species’ marginal response to each variable while holding all other variables at their average value. Environmental data were sourced from the WorldClim database.

With spatial units having a probability value p ≥ 0.5 defined as the most suitable distribution area [11,30], the response curves of the four main habitat factors were used to determine the environmental adaptation thresholds for P. adenopoda in the study region (Figure 5): bio6 (−2.04 to 3.18 °C), bio12 (877.25 to 1566.35 mm), bio4 (692.76 to 865.97 °C), and elev (430.35 to 887.78 m).

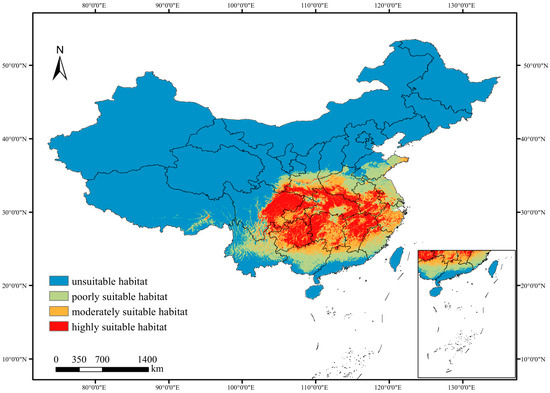

3.4. Distribution of Suitable Habitat of P. adenopoda Under Current Climate Scenario

The optimal MaxEnt model simulation revealed that the total suitable habitat area for P. adenopoda under current climatic scenarios is approximately 228.19 × 104 km2, accounting for about 23.94% of China’s total land area. Among these suitable habitats, the highly suitable areas were estimated to cover 73.95 × 104 km2, followed by 66.02 × 104 km2 of moderately suitable habitat, and 88.22 × 104 km2 of poorly suitability habitat (Table 2). Geographically, the suitable habitats are primarily concentrated in southern China, including but not limited to Yunnan, Chongqing, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guizhou, and Zhejiang provinces (Figure 6). Southeastern coastal regions of China may also fall within the predicted suitable range. Moderately suitable habitats were mainly distributed around the peripheries of the highly suitable habitats, extending into central and eastern provinces. The core areas of highly suitable habitat were located in Guizhou, Chongqing, Hubei, and Hunan provinces.

Figure 6.

Predicted distribution of suitable habitats for Populus adenopoda under current climatic conditions (1970–2000 baseline). The habitat suitability, derived from the MaxEnt model, is classified into four categories: unsuitable (<0.08), poorly (0.08–0.27), moderately (0.27–0.46), and highly (>0.46). The map was generated based on an ensemble of 10 model runs. Climate data were sourced from the WorldClim database (Version 2.1).

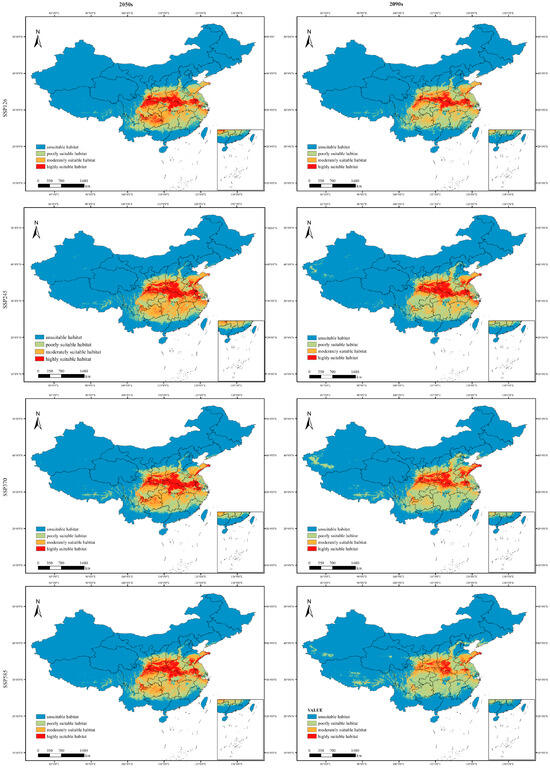

3.5. Prediction of Suitable Habitat in P. adenopoda Under Different Climate Scenarios in the Future

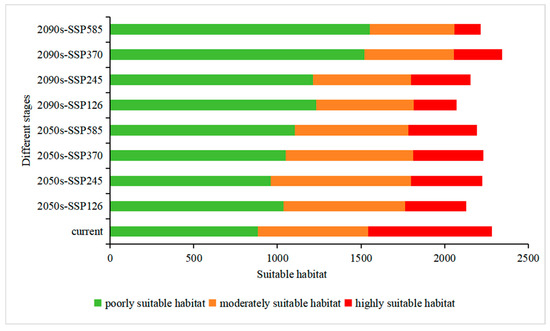

This study assessed the area of suitable habitats for P. adenopoda in four climate scenarios over two future periods (Figure 7). Projected changes in the suitable habitat area for P. adenopoda under different future climate scenarios revealed complex and concerning trends relative to the current baseline (Table 2 and Table 3). While the total suitable area (sum of all three classes) showed varying trends, a consistent pattern of habitat degradation was observed across all scenarios.

Figure 7.

Projected distribution of suitable habitats for Populus adenopoda in the 2050s and 2090s under four CMIP6 climate scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, SSP585). Maps are derived from MaxEnt modeling, with habitat classified into four suitability levels.

The total suitable habitat area exhibited variation across different future scenarios. Under certain pathways such as SSP370 in the 2090s, a slight increase was observed (reaching 234.50 × 104 km2). In contrast, more extreme scenarios like SSP126 in the 2090s predicted a reduction to 207.31 × 104 km2 (Table 2), reflecting a divergent response to varying climate pathways.

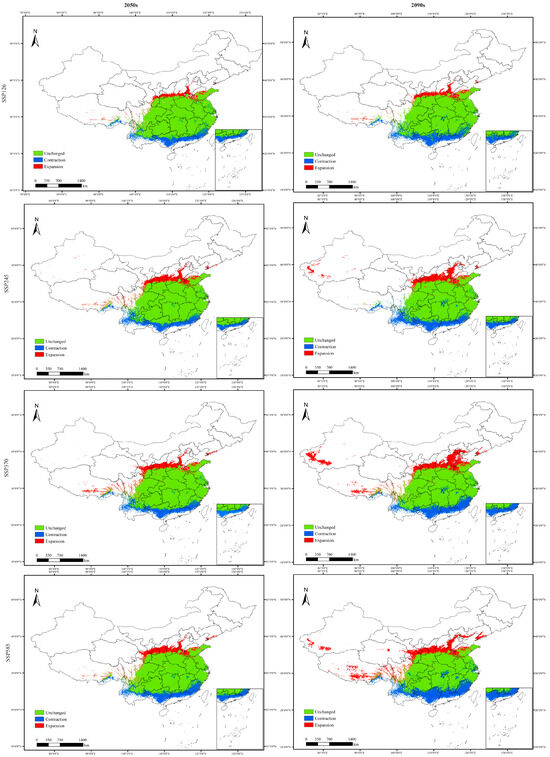

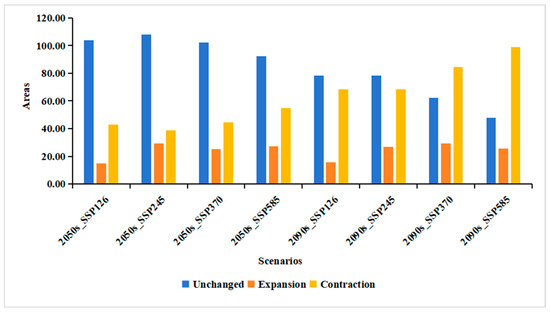

A consistent and critical trend emerged across all future scenarios: a severe contraction of highly suitable habitat. Losses ranged from −42.38% (2050s SSP245) to a drastic −78.81% (2090s SSP585, Table 3), underscoring a significant deterioration in the quality of the core habitat. Concurrently, poorly suitable habitat expanded markedly, with increases from +8.70% to +75.92%, suggesting that future climates may render new areas marginally suitable but of low ecological value for long-term species persistence. The moderately suitable habitat showed a non-uniform response, gaining area in some mid-century scenarios (e.g., +27.40% under 2050s SSP245) but declining across all end-century scenarios (e.g., −23.11% under 2090s SSP585), highlighting a progressive escalation of climatic pressures over time (Table 3 and Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Projected changes in the distribution pattern of potentially suitable habitats for Populus adenopoda between the 2050s (2041–2060) and 2090s (2081–2100) under four CMIP6 climate scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585). The changes are categorized into three types: unchanged (areas remaining suitable under both current and future climates), expansion (areas becoming suitable in the future), contraction (areas becoming unsuitable in the future). The maps were generated by comparing the future projections from the MaxEnt model with the current potential distribution.

The magnitude of habitat changes was profoundly influenced by both the time period and the emission scenario. The most severe impacts were consistently projected under the high-emission scenario SSP585, particularly by the 2090s, which resulted in the largest expansion of low-suitability area (+75.92%) and the greatest loss of high-suitability core habitat (−78.81%). Conversely, the low-emission scenario SSP126 projected relatively moderate changes, though still indicating a substantial decline (>65%) in highly suitable areas by the 2090s. This pattern emphasizes that the species’ distribution vulnerability is highly sensitive to the degree of climate change mitigation (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Area of potential suitable habitat for Populus adenopoda under current and future climates. The bars represent the total area of poorly, moderately, and highly suitability classes for the baseline period and future scenarios (2050s, 2090s; SSP126, 245, 370, 585), as projected by the MaxEnt model. Area is given in 104 km2.

Geospatially, these quantitative changes suggest a potential northward and eastward shift in the distribution centroid, with a pronounced shift from high-quality to low-quality habitats across southern and central China. The core suitable areas are projected to become increasingly fragmented. Similarly, using the maxTSS threshold of 0.25 to convert the continuous probability predictions into binary (suitable/non-suitable) maps revealed a significant future decrease in overall suitable area and a marked contraction in species range (Figure A2). This finding is consistent with the primary results obtained using the Natural Breaks method.

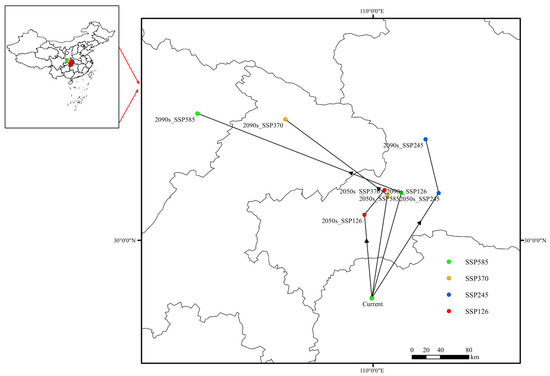

3.6. Centroid Migration of Suitable Habitat Under Future Climate Scenarios

This study reveals the characteristics of the dynamic response of the spatial distribution pattern of suitable habitats for P. adenopoda to climatic stress through centroid migration trajectory analysis (Figure 10). Under current climatic scenario, the centroid of the highly suitable habitat for P. adenopoda in China is located in Yongshun County, Hunan Province (29.26° N, 109.98° E). Under the four future climate scenarios, the centroid of suitable habitats generally shifts northward initially, followed by a southwestward migration. Under the SSP126 scenario, by the 2050s, the centroid is projected to migrate northward to Enshi City, Hubei Province (109.88° E, 30.31° N), with a migration distance of 117.06 km. By the 2090s, the centroid shifts northeastward by 42.58 km (Table 4).

Figure 10.

Migration of the distribution centroid for Populus adenopoda under different climate scenarios. The map shows the calculated centroid location for the baseline period and its projected shift in the 2050s and 2090s under four SSPs. The arrows connect the baseline centroid to its future positions, indicating the direction and magnitude of the overall range shift.

Table 4.

Centroid coordinates and shifts of suitable habitat for Populus adenopoda. The table lists the longitude and latitude (decimal degrees) of the distribution centroid for the baseline and future scenarios (2050s, 2090s; SSP126 to SSP585). The migration distance from the baseline centroid is provided in kilometers (km).

Under the SSP245 scenario, by the 2050s, the centroid shifts northeastward to Yichang City, Hubei Province (110.82° E, 30.59° N), with a displacement of 168.42 km. By the 2090s, it continues to migrate northward by an additional 76.93 km, remaining within Yichang City. Under the SSP370 scenario, by the 2050s, the centroid relocates to Badong County, Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province (110.17° E, 30.56° N), over a distance of 145.61 km. By the 2090s, it shifts northwestward by 162.44 km to Wuxi County, Chongqing Municipality.

Under the SSP585 scenario, the distribution centroid of P. adenopoda initially resides within Hubei Province (110.35° E, 30.59° N) and later shifts into Sichuan Province (107.77° E, 31.59° N). It is noteworthy that the projected centroid shift of approximately 269 km under SSP585 by 2100 is substantial, highlighting the intense pressure on species to track their suitable climate under a high-emission future. Comprehensive analysis indicates a general northwestward shift in the centroid of suitable habitats for P. adenopoda in the future. This trajectory suggests a potential adaptive migration toward higher latitudes and elevations in response to climate warming.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms Underlying Distribution Shifts and Ecological Implications

Our study identifies minimum temperature of the coldest month (bio6) and annual precipitation (bio12) as the predominant factors governing the distribution of P. adenopoda, a finding that aligns with the known physiology of subtropical pioneer trees [49,50]. The paramount importance of bio6 suggests that frost tolerance and avoidance of xylem embolism during freezing events are likely key physiological constraints [51]. This is corroborated by our response curve, which indicates a sharp decline in suitability when bio6 falls below −2.04 °C, a threshold consistent with its observed distribution limit where winter temperatures rarely fall below this value and supported by recent ecophysiological studies on related species [52].

Under future climates, rising minimum temperatures are projected to relax this cold constraint at the northern and high-elevation boundaries, theoretically permitting range expansion. However, our projections reveal a counterintuitive trend: a severe contraction of high-suitability core habitats. This paradox can be explained by a concomitant increase in moisture stress. The significant role of bio12, coupled with recent research, indicates that reduced annual precipitation and increased temperature seasonality may push conditions beyond the species’ hydraulic safety margin. This trade-off between released cold stress and emergent drought stress underscores the non-linear nature of species responses to climate change, where factors acting on different physiological processes can have opposing effects on the distribution. Our binary projection using the maxTSS threshold of 0.25 further confirms this pattern, showing a significant increase in contraction areas and only a limited expansion, resulting in a net decrease in the unchanged suitable habitat. This suggests that the newly gained, marginally suitable areas are ecologically insufficient to compensate for the loss of high-quality core habitats.

4.2. Comparative Vulnerability and Conservation Context

The projected pattern of habitat degradation—where core areas diminish while marginal areas expand—is emerging as a common trend for many endemic species in subtropical China [53,54]. However, the magnitude of projected loss for P. adenopoda (>78% loss of highly suitable habitat under SSP585) is notably more severe than that projected for more widespread relatives like Populus davidiana [55]. This contrast underscores the critical influence of ecological amplitude on climate change vulnerability.

The projected northwestward shift of the distribution centroid represents a logical response to tracking cooler and potentially wetter conditions, a pattern observed in numerous other species across the Northern Hemisphere [53,56,57]. However, this climatic suitability does not guarantee successful population establishment. The migration path traverses regions with complex topography and potentially fragmented landscapes, which are known to impede natural dispersal for tree species with limited seed dispersal capabilities [58,59]. Therefore, while our models project a potential climatic distribution under an unlimited dispersal assumption, the realized distribution will likely be significantly smaller, highlighting a critical challenge for conservation.

4.3. Management Implications: From Projection to Action

Our spatially explicit projections, validated by both the Natural Breaks and TSS threshold methods, provide a robust foundation for translating ecological thresholds into actionable conservation strategies. We propose a triage approach focusing on three key actions:

First, the identified core refugia in central-southern China (e.g., the Wuling Mountains), which remain stable across multiple future scenarios, must be prioritized for enhanced protection. This includes strengthening existing reserve networks and maintaining habitat connectivity to facilitate natural gene flow, a key strategy for conserving biodiversity in a changing climate [60,61,62].

Second, for forest management in currently suitable areas, our results indicate that plantations within zones projected to become marginal or undergo contraction face increased risks. In these areas, pre-adaptive strategies—such as thinning to reduce water competition or selecting more drought-tolerant provenances within assisted regeneration programs—should be tested and implemented [63,64].

Finally, the future climatically suitable areas identified in northern Sichuan and southern Gansu represent potential targets for assisted migration. However, these regions must be rigorously evaluated not only for climatic suitability but also for soil compatibility and current land use, as guided by recent assisted migration frameworks [65,66]. This critical step mitigates potential ecological risks and ensures conservation resources are invested in areas with the highest likelihood of supporting viable future populations.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While our study provides robust insights, several limitations must be acknowledged to guide the interpretation of our results and future research. First, as a climate-envelope model, MaxEnt establishes correlations between species occurrences and macro-climatic variables but does not explicitly incorporate critical biotic interactions (e.g., competition, pests) or fine-scale edaphic factors. The omission of these variables, particularly soil properties, is a key reason why our model might overestimate suitability in some newly expanded areas or underestimate potential in localized refugia with buffering microclimates [67,68]. Second, while the BCC-CSM2-MR climate model is well-validated for China, relying on a single model introduces uncertainty. Future studies would benefit from a multi-model ensemble approach to better quantify and capture the uncertainty inherent in climate projections [69,70]. Finally, the assumption of unlimited species dispersal is optimistic. Generating more realistic projections requires future work to integrate models of dispersal limitation and future land-use change scenarios. Furthermore, conducting eco-physiological experiments to empirically validate the identified thresholds for P. adenopoda would significantly strengthen the mechanistic basis of the model and refine future predictions [71,72].

5. Conclusions

This study employed MaxEnt modeling to achieve its three primary objectives: identifying the key environmental drivers for P. adenopoda, projecting its habitat shifts under climate change, and deriving targeted conservation strategies. Our findings provide clear answers: (1) The species’ distribution is predominantly constrained by the minimum temperature of the coldest month (bio6) and annual precipitation (bio12), with a critical lower cold tolerance threshold at −2.04 °C; (2) future projections reveal a severe habitat degradation, with highly suitable areas declining by up to 78.8% under SSP585 and the distribution centroid shifting northwest by up to 269.44 km; (3) consequently, conservation must prioritize the identified core refugia (e.g., Guizhou, Hunan, Chongqing, Hubei) to prevent fragmentation, while assisted migration is recommended to future suitable zones given the improbability of sufficient natural regeneration.

To guide future research and ground-truth these projections, we propose the following specific actions: systematically surveying soil compatibility and land use in migration corridors, employing UAV-based monitoring for regional habitat assessment, and initiating provenance trials to test genetic adaptation to drought and cold stress. This work provides a spatially explicit, actionable framework for the conservation of P. adenopoda under climate change.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization: Y.T.; Data curation, Validation, Writing—review and editing: J.S.; Methodology, Formal analysis: B.C.; Software, Investigation: R.W.; Investigation, Formal analysis: Y.Z.; Investigation: J.Z. (Jingkai Zhang); Writing—review and editing: J.Z. (Jianguo Zhang); Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Methodology: Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jia Song was employed by the company Powerchina Northwest Engineering Corporation Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of environmental variables used in the study, including 19 climate factors and 3 terrain factors.

Table A1.

List of environmental variables used in the study, including 19 climate factors and 3 terrain factors.

| Type | Code | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate | bio1 | Annual mean temperature | °C |

| bio2 | Mean diurnal range (Mean of monthly (max.temp. − min.temp.)) | °C | |

| bio3 | Isothermality (bio2/bio7) (×100) | ||

| bio4 | Temperature seasonality (standard deviation × 100) | ||

| bio5 | Max temperature of the warmest month | °C | |

| bio6 | Min temperature of the coldest month | °C | |

| bio7 | Temperature annual range (bio5–bio6) | °C | |

| bio8 | Mean temperature of the wettest quarter | °C | |

| bio9 | Mean temperature of the driest quarter | °C | |

| bio10 | Mean temperature of the warmest quarter | °C | |

| bio11 | Mean temperature of the coldest quarter | °C | |

| bio12 | Annual precipitation | mm | |

| bio13 | Precipitation of the wettest month | mm | |

| bio14 | Precipitation of the driest month | mm | |

| bio15 | Precipitation seasonality (Coefficient of variation) | ||

| bio16 | Precipitation of the wettest quarter | mm | |

| bio17 | Precipitation of the driest quarter | mm | |

| bio18 | Precipitation of the warmest quarter | mm | |

| bio19 | Precipitation of coldest quarter | mm | |

| topographical | elev | Elevation | m |

| slope | ° | ||

| aspect |

Figure A1.

Single response curves for the three remaining dominant environmental factors: (a) slope, (b) precipitation Seasonality (bio15), and (c) aspect. The curves depict the modeled relationship between each factor and the predicted habitat suitability, derived from the MaxEnt model. Values on the y-axis represent the logistic probability of presence (ranging from 0 to 1).

Figure A2.

Dynamics of habitat suitability for Populus adenopoda under future SSP scenarios. The changes in suitable habitat area (km2) from the baseline are quantified as Expansion, Contraction, and Unchanged, using a TSS threshold of 0.25 in the ensemble SDM projections.

References

- Schipper, E.L.F.; Revi, A.; Preston, B.L.; Carr, E.R.; Eriksen, S.H.; Fernández-Carril, L.R.; Glavovic, B.; Hilmi, N.J.M.; Ley, D.; Mukerji, R.; et al. Climate Resilient Development Pathways. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M.M.B., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.M.; Knutti, R. Anthropogenic Contribution to Global Occurrence of Heavy-Precipitation and High-Temperature Extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; McDowell, N.G. On Underestimation of Global Vulnerability to Tree Mortality and Forest Die-off from Hotter Drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 2015, 6, art129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, L.; Ferchaud, A.-L.; Berger, C.S.; Venney, C.J.; Xuereb, A. Genomics for Monitoring and Understanding Species Responses to Global Climate Change. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L.; Roehrdanz, P.R.; Krishna Bahadur, K.C.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Donatti, C.I.; Saenz, L.; Wright, T.M.; Hijmans, R.J.; Mulligan, M.; Berg, A.; et al. The Environmental Consequences of Climate-Driven Agricultural Frontiers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, A.; Ammer, C.; Löf, M.; Madsen, P.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; Schall, P.; Spathelf, P.; Rock, J. Adaptive Forest Management in Central Europe: Climate Change Impacts, Strategies and Integrative Concept. Scand. J. For. Res. 2009, 24, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, R.; Augustynczik, A.L.D.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Lasch-Born, P.; Suckow, F.; Hanewinkel, M. Realizing Mitigation Efficiency of European Commercial Forests by Climate Smart Forestry. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zheng, H.; Milne, R.I.; Zhang, L.; Mao, K. Strong Population Bottleneck and Repeated Demographic Expansions of Populus adenopoda (Salicaceae) in Subtropical China. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Hou, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X. Prediction of the Potential Distribution of Chimonobambusautilis (Poaceae, Bambusoideae) in China, Based on the MaxEnt Model. Biodivers. Data J. 2024, 12, e126620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Shi, X.-D.; Shi, L.; Yao, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yang, W.-Z.; Liao, Z.-Y.; Qi, Y. Enhanced Risk Assessment Framework Integrating Distribution Dynamics, Genetically Inferred Populations, and Morphological Traits of Diploderma Lizards. Zool. Res. 2025, 46, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Spatial Distribution and Topographic Gradient Effects of Habitat Quality in the Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lin, J. Projecting Future Land Use Evolution and Its Effect on Spatiotemporal Patterns of Habitat Quality in China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, J.; Peterson, A.T. What Is the Shape of the Fundamental Grinnellian Niche? Theor. Ecol. 2020, 13, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, L.P.; Hayward, M.W.; Loyola, R. What Do You Mean by “Niche”? Modern Ecological Theories Are Not Coherent on Rhetoric about the Niche Concept. Acta Oecologica 2021, 110, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, J. The Niche-Relationships of the California Thrasher. Auk 1917, 34, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinnell, J. The Origin and Distribution of the Chestnut-Backed Chickadee. Auk 1904, 21, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Chevalier, M.; Adde, A.; Zarzo-Arias, A.; Goicolea, T.; Broennimann, O.; Petitpierre, B.; Scherrer, D.; Rey, P.-L.; Collart, F.; et al. Spatially Nested Species Distribution Models (N-SDM): An Effective Tool to Overcome Niche Truncation for More Robust Inference and Projections. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 1588–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Merino, S.M.; Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Lira-Noriega, A. Ecological Niche Models and Species Distribution Models in Marine Environments: A Literature Review and Spatial Analysis of Evidence. Ecol. Model. 2020, 415, 108837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglielli, G.; Hutchings, M.J.; Laanisto, L. The Triangular Space of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Woody Species: A Unified Trade-off Model. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, J.; Tao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. From Thermal Tolerance to Distribution Resilience: Physiology-Informed Species Distribution Models Moderated Range Shifts for an Intertidal Crab Species under Climate Change. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.W.F.; Coffman, G.C. Integrating the Resilience Concept into Ecosystem Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, S.; Wu, G.; Zheng, X.; Wu, X. Ecological Restorations Enhance Ecosystem Stability by Improving Ecological Resilience in a Typical Basin of the Yangtze River, China. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordling, K.; Fahrenbach, N.L.S.; Samset, B.H. Climate Variability Can Outweigh the Influence of Climate Mean Changes for Extreme Precipitation under Global Warming. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 1659–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kort, H.; Baguette, M.; Lenoir, J.; Stevens, V.M. Toward Reliable Habitat Suitability and Accessibility Models in an Era of Multiple Environmental Stressors. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 10937–10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R. Species Distribution Models: Ecological Explanation and Prediction Across Space and Time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 40, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sun, J.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Luo, D.; Guo, J.; He, X.; Zhao, G.; Tian, X.; Qiu, J.; Feng, Z.; et al. Planning Ginkgo biloba Future Fruit Production Areas under Climate Change: Application of a Combinatorial Modeling Approach. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 533, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lin, F.; Li, M.; Mei, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Zheng, Y. Prediction of the Potential Distribution of a Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus) in China Based on MaxEnt Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; O’Neill, G.A.; Coops, N.C.; Wang, T. Predicting the Site Productivity of Forest Tree Species Using Climate Niche Models. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 562, 121936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change on the Distribution of Species: Are Bioclimate Envelope Models Useful? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum Entropy Modeling of Species Geographic Distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, S.; Chen, S. Predicting the Potential Habitat Suitability of Saussurea Species in China under Future Climate Scenarios Using the Optimized Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Pan, K.; Hu, Q.; He, M.; Li, J. Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change on the Potential Distribution of Major Native Non-Food Bioenergy Plants in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru-Ru, W.U.; Mei-Zhen, L.I.U.; Xian, G.U.; Xin-Yue, C.; Li-Yue, G.U.O.; Gao-Ming, J.; Ru-Yi, Q.I. Prediction of Suitable Habitat Distribution and Potential Impact of Climate Change on Distribution Patterns of Cupressus Gigantea. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 48, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, Z.; Stith, B.; Bowling, A.C.; Langtimm, C.A.; Swain, E.D. Evaluation of Habitat Suitability Index Models by Global Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analyses: A Case Study for Submerged Aquatic Vegetation. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 2503–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, D.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Feng, S. A Framework for Assessing Variations in Ecological Networks to Support Wildlife Conservation and Management. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Gao, C.; Yang, C. Potential Distribution of Tamarix boveana Bunge in Mediterranean Coastal Countries Under Future Climate Scenarios. Forests 2025, 16, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Hou, Y.; Yu, C. Optimized MaxEnt Modeling of Catalpa Bungei Habitat for Sustainable Management Under Climate Change in China. Forests 2025, 16, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-Km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) Experimental Design and Organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, P.; Nóbrega, C.C. Evaluating Collinearity Effects on Species Distribution Models: An Approach Based on Virtual Species Simulation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, W.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, H.; Jiang, J. Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Sapindus delavayi Based on the MaxEnt Model. Forests 2022, 13, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. The Optimized Maxent Model Reveals the Pattern of Distribution and Changes in the Suitable Cultivation Areas for Reaumuria songarica Being Driven by Climate Change. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.F.; Ahmed, A.M.A.; Abdel-Dayem, M.S.; Abdullah, M.A.R. Ecological Niche Modeling and Land Cover Risk Areas for Rift Valley Fever Vector, Culex Tritaeniorhynchus Giles in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechergui, K.; Jiang, M.; Qi, Z.; Alamri, S.M.; Alamery, E.R.; Faqeih, K.Y.; AlAmri, A.R.; Jaouadi, W.; Yan, X. The Effects of Climate Change on Distributions of Four Endemic and Medicinal Species in the North Africa Using MaxEnt Modeling and GIS Tools. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 235, 121766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of Species Distributions with Maxent: New Extensions and a Comprehensive Evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Sharma, L.K.; Kumar, R.; Naik, R.; Divyansh, K. Assessing the Susceptibility for Potential Site Suitability and Distribution of Flamingos with Respect to Changing Climate Using Maxent Modelling. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.B.; Park, G.E.; Kim, H.J.; Huh, J.H.; Um, Y. Predicting the Habitat Suitability for Angelica Gigas Medicinal Herb Using an Ensemble Species Distribution Model. Forests 2023, 14, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canturk, U.; Koç, İ.; Erdem, R.; Ozturk Pulatoglu, A.; Donmez, S.; Ozkazanc, N.K.; Sevik, H.; Ozel, H.B. Climate-Driven Shifts in Wild Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Habitats in Türkiye: A Multi-Model Projection for Conservation Planning. Forests 2025, 16, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Delzon, S.; Clearwater, M.J.; Bellingham, P.J.; McGlone, M.S.; Richardson, S.J. Climatic Limits of Temperate Rainforest Tree Species Are Explained by Xylem Embolism Resistance among Angiosperms but Not among Conifers. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, C.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xia, C. Predicting Potential Habitats of the Endangered Mangrove Species Acanthus ebracteatus Under Current and Future Climatic Scenarios Based on MaxEnt and OPGD Models. Plants 2025, 14, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ullah, F.; Zou, J.; Zeng, X. Molecular and Physiological Responses of Plants That Enhance Cold Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Dai, H.; Fang, L.; Korpelainen, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Li, C. Sex-Specific Non-Structural Carbohydrate Variation and Hydraulics Explain Differences in Drought Resistance of Populus Euphratica Females and Males along an Aridity Gradient. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 2925–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J. Projected Degradation of Quercus Habitats in Southern China under Future Global Warming Scenarios. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 568, 122133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, A.E.; Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Caitlin Fisher-Reid, M.; Hua, X.; Karanewsky, C.J.; Ryu, H.Y.; Sbeglia, G.C.; Spagnolo, F.; Waldron, J.B.; Wiens, J.J. Causes of Warm-Edge Range Limits: Systematic Review, Proximate Factors and Implications for Climate Change. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, G.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Du, S. Future Climate Change Will Have a Positive Effect on Populus Davidiana in China. Forests 2019, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guan, B.-Q.; Chen, R.; Yi, R.; Jiang, X.-L.; Xie, K.-Q. Investigating the Distribution Dynamics of the Camellia Subgenus Camellia in China and Providing Insights into Camellia Resources Management Under Future Climate Change. Plants 2025, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jiang, C.; Li, X.; Fan, H.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Optimized MaxEnt Modeling Reveals Major Decline and Shift of Giant Panda Habitat under CMIP6 Ensemble Projections. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, J.D.; Altermatt, F.; Finn, D.S.; Heino, J.; Olden, J.D.; Pauls, S.U.; Lytle, D.A. The Role of Dispersal in River Network Metacommunities: Patterns, Processes, and Pathways. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 63, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanson, G.P.; Cairns, D.M. Effects of Dispersal, Population Delays, and Forest Fragmentation on Tree Migration Rates. Plant Ecol. 1997, 131, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Peng, J.; Dong, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, M.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Z. Expanding China’s Protected Areas Network to Enhance Resilience of Climate Connectivity. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-W.; Hou, N.; Woeste, K.; Zhang, C.; Yue, M.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Zhao, P. Population Genetic Structure and Adaptive Differentiation of Iron Walnut Juglans Regia Subsp. in Sigillata Southwest China. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 14154–14166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, T.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, G.; Fei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Qiao, X. Wuling Mountains Function as a Corridor for Woody Plant Species Exchange Between Northern and Southern Central China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 837738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, A.; Granda, L.; Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Šamajová, O.; Šamaj, J.; Cerkal, R. A Dual Strategy of Breeding for Drought Tolerance and Introducing Drought-Tolerant, Underutilized Crops into Production Systems to Enhance Their Resilience to Water Deficiency. Plants 2020, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Raman, H.; Wheeler, D.; Kalenahalli, Y.; Sharma, R. Data-Driven Approaches to Improve Water-Use Efficiency and Drought Resistance in Crop Plants. Plant Sci. 2023, 336, 111852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelRahman, M.A.E.; Saleh, A.M.; Arafat, S.M. Assessment of Land Suitability Using a Soil-Indicator-Based Approach in a Geomatics Environment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpoti, K.; Kabo-bah, A.T.; Zwart, S.J. Review—Agricultural Land Suitability Analysis: State-of-the-Art and Outlooks for Integration of Climate Change Analysis. Agric. Syst. 2019, 173, 172–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.H. Why Understanding the Pioneering and Continuing Contributions of BIOCLIM to Species Distribution Modelling Is Important. Austral Ecol. 2018, 43, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ellison, A.M.; Davis, C.C. Incorporating Responses of Traits to Changing Climates into Species Distribution Models: A Path Forward. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Scaife, A.A.; Shepherd, T.G.; Deser, C.; Dunstone, N.; Schmidt, G.A.; Trenberth, K.E.; Turkington, T. Importance of Internal Variability for Climate Model Assessment. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Lee, D.-K.; Gutowski, W.; Dairaku, K.; McGregor, J.; Katzfey, J.; Gao, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Ensemble Evaluation and Projection of Climate Extremes in China Using RMIP Models. Int. J. Clim. 2018, 38, 2039–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.J., Jr.; Hefley, T.J.; Robertson, E.P.; Zuckerberg, B.; McCleery, R.A.; Dorazio, R.M. A Practical Guide for Combining Data to Model Species Distributions. Ecology 2019, 100, e02710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhof, E.; Campos-Arguedas, F.; Arias, N.S.; Kovaleski, A.P. Thresholds for Spring Freeze: Measuring Risk to Improve Predictions in a Warming World. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).