Abstract

The steadily increasing demand for energy and concerns about climate change have prompted countries to promote the use of renewable energy sources, including lignocellulosic biomass. In this context, this work aims to assess the biomass production for energy purposes in crops with short rotation, as well as its effect on soil properties. Deciduous tree species were used, mainly Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila L.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) and a hybrid poplar clone (Populus × euroamericana (Dode) Guinier, clone ‘AF2’). Four field trials were implemented, under two different types of Mediterranean climate, where highly productive taxa were tested, in addition to the mixed planting of a nitrogen-fixing species with a non-fixing one. Short-rotation coppices (SRCs) of these taxa yield about 12–14 t ha−1 year−1 of high-quality dry woody biomass, when fertilizers and irrigation water are supplied; generate 205–237 GJ ha−1 year−1 net and earnings of about EUR 1.5 per EUR 1 invested; and sequester into the soil 0.36–0.83 t ha−1 year−1 of C and 57 kg ha−1 year−1 of N. Therefore, these species raised as SRCs could improve degraded soils if the crop is properly managed, resulting in favorable economic, energy and CO2 emission balances. The use of mixed plantations can bring economic and environmental gains, and the biomass transformation into high-quality chips or pellets gives it added value.

1. Introduction

In the context of climate change, international institutions have promoted the use of clean and renewable energy sources, including biomass, to protect the global environment and reduce greenhouse gas emissions [1,2]. Currently, biomass accounts for more than half of all global renewable energy production and about 11% of all energy sources [3]. For instance, the Energy Roadmap 2050 of the European Commission has set as a goal to reduce CO2 emissions that renewable energy sources increase their contribution to gross final energy consumption by at least 55% [4]. As a consequence, the use of lignocellulosic biomass is steadily expanding and can play an essential role in achieving the renewable energy goal in 2050. It is regarded as a flexible primary energy due to the value-added products derived from it, such as chips, pellets, biogas, bio-based materials and chemicals [5,6,7], apart from traditional uses. Additionally, the increasing demand for woody biomass for industrial purposes such as wood pulp and wood-based panels [8] also contributes to expanding its use. Therefore, in order to meet the growing global demand, plantations of fast-growing species could supplement the additional woody biomass that traditional agroforestry systems cannot supply, and constitute a fundamental complement in the biomass market, since they provide an alternative use for abandoned land, contributing to rural development while reducing CO2 emissions [5,9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, these plantations could reduce some negative effects of biomass exploitation in traditional forest systems, such as the depletion of soil fertility caused by nutrient removal in whole-tree harvesting, as well as the alteration of habitat and biodiversity in sensitive sites [13,14,15,16]. Short-rotation coppice (SRC) plantations consist of a woody cultivation in short cycles (usually less than 7 years) of fast-growing species capable of sprouting from the stump after being cut, and provide a suitable means of obtaining this raw material in short periods of time [17].

Currently, different plant taxa are managed worldwide as SRC crops (e.g., the genera Populus, Salix, Eucalyptus, Paulownia, Gmelina, Robinia, Casuarina, Leucaena, etc.), and also some species such as Ulmus pumila L., Platanus × hispanica Mill. ex Münchh. and Ailanthus altissima (Mill) Swingle. have been studied for woody biomass production [18,19,20,21]. Most of the above-mentioned species are multiple-purpose species providing numerous goods and services (e.g., biofuel, carbon sequestration, soil restoration, wood pulp, forage, etc.). Under optimal environmental conditions, commercial plantations can reach up to 25 t ha−1 year−1 dry matter with poplars and willows, around 40 t ha−1 year−1 with eucalypts, Paulownia, Casuarina and Leucaena, and 15 t ha−1 year−1 with black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) [11,12,18,22,23]. However, adverse environmental conditions, such as the winter frosts of inland and high-altitude continental areas as well as the typical summer drought of Mediterranean climates, compromise the growth and survival of many of these taxa to such an extent that if they survive, the production can drop well below 5 t ha−1 year−1. Moreover, most of these woody energy crops will be established on degraded soils, and they will be required to produce a large amount of biomass profitably [12,24]. Farmland degradation is a serious problem today. Currently, in Europe alone, 45% of farmland contains less than 2% organic matter, 15% suffer from problems derived from excess inorganic nitrogen fertilization, and significant signs of erosion can be observed in more than 147 million hectares [25,26]. At least 70% of all these degraded and low-fertility lands are under a climate where Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and/or Popupulus sp. can grow. However, special attention must also be paid to the quality of the biomass grown on contaminated soils (e.g., uncultivated land or post-industrial soils), since apart from nitrogen contamination, other elements, including heavy metals, may affect plant growth, biomass quality and industrial processes for transforming it into various types of fuels [27].

Recent studies have shown that Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and Populus sp. stand out in areas under a Mediterranean continental climate with cold winters, in Central Europe and North America, as they can tolerate winter frosts well below −20 °C [19,28,29,30,31]. The latter has a great capacity to adapt to different environmental conditions, as well as a high hybridization capacity and ease of vegetative propagation. These characteristics, together with its rapid growth, have contributed to the development of a very extensive clonal offer, which requires the prior selection of each site and specific use. However, this genus requires wet soils, while R. pseudoacacia and U. pumila are alternatives due to their great drought tolerance [18,19,32], but they must be managed with care since they can become invasive and alter the native plant habitats [33,34]. Ulmus pumila and Robinia pseudoacacia have not been subjected to advanced genetic improvement programs, nor do they offer selected clonal plants. For the latter species, studies in this regard were started a few years ago [35,36] in central Europe, but the clones are not adapted to the arid edaphoclimatic conditions of the Mediterranean basin, nor are they available on the market. Consequently, these two species require selection, improvement and breeding programs due to the high growth variability shown by R. pseudoacacia in trial plots established up to now, and the difficulties of vegetative propagation of U. pumila, mainly in vitro [37,38].

Thus, it is necessary to evaluate the biomass yield and the environmental effect of an intensive production system such as SRC on degraded soils [7,39,40], since the knowledge in Mediterranean environment is still scarce and depends on the cultivated species, cultivation practices and environmental factors [11,12,41]. In this respect, a N-fixing species such as Robinia pseudoacacia can be used in SRC energy crops [19,42], since it can contribute to decreasing inorganic nitrogen fertilization, and as a result to reducing economic and energy costs [43]. Moreover, many studies have shown that mixtures of species can be more productive than monocultures because species’ interactions can increase resource availability as well as resource use efficiency (i.e., less intense inter-specific than intraspecific competition). An example of this is the mixture of nitrogen-fixing and non-nitrogen-fixing species, mainly if soil nitrogen is limited [19,22,44,45].

This manuscript compiles four field trials carried out in the Mediterranean environment that assessed the biomass production and the evolution of the top layer of the soil after being subjected to intensive SRC energy crops. It aims to evaluate whether SRC plantations of fast-growing tree species can improve a degraded soil while producing high-quality biomass. Soil properties were assessed under hybrid poplar (Populus × euroamericana (Dode) Guinier), black locust and Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila L.) subjected to different cultivation treatments. The main objectives are: (a) to evaluate plant growth and biomass production of hybrid poplars, black locust and Siberian elm subjected to different SRC treatments in two contrasting Mediterranean environments; (b) to assess their appropriateness for use as bioenergy; (c) to determine the changes of soil properties after a cropping period of 5 to 8 years; and (d) to analyze carbon sequestration and the economic and environmental viability of this production system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Plant Material

This article shows the research carried out in four independent field trials, which have several aspects in common: the location was the same for three of them; two species, Robinia pseudoacacia L. and Populus × euroamericana (Dode) Guinier, were used in the four trials, and Ulmus pumila L. in three of them; the crops were developed in Spain under a Mediterranean climate; they were designed as short-rotation coppices (SRC) for energy purposes; and both the irrigation and fertilization also coincided to a great extent. Different intraspecific taxa were used for poplars and black locust because the tolerance to environmental stresses and the nutrient requirements of these species can vary significantly [19,31,36]. Two sites with marginal agricultural lands were selected, located in the provinces of Granada (Los Morales—Mo; UTM, zone 30S, X:535457, Y:4191514, 1084 m.a.s.l.) and Huelva (La Rábida—Ra; UTM, zone 29S, X: 685054, Y: 4119168, 7 m.a.s.l.). Three field trials were established at Los Morales (Mo1, Mo2 and Mo3) and one at La Rábida (Ra4). The main climate conditions and soil characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 and Table S1, respectively. Both sites have a typical Mediterranean climate with hot and dry summers, but with cold winters in Los Morales and mild winters in La Rábida, which makes the vegetative period more than two months longer in Ra than in Mo. The soils were permeable alkaline soils (pH = 8.2–8.7) with low salinity (EC ≤ 331 μS cm−1), appropriate C/N ratio, high Ca and Mg contents, deficient in P, Fe, Mn and Zn, and with medium (Los Morales) or low (La Rábida) levels of OM, CEC, N, K and active limestone. The stoniness was 19.2% and 23.4%, and the bulk density was 1.32 and 1.55 kg dm−3, for Los Morales and La Rábida, respectively. Previously, the land had been dedicated to the cultivation of rain-fed barley, and it did not present problems of contamination by heavy metals or other nutrients. The N, P and K contents in the irrigation water were 6.1, 0.15 and 0.22 mg L−1, respectively.

Table 1.

Climatic conditions at the field plots during the three time periods studied. Mo (Los Morales), Ra (La Rábida).

Table 2.

Physical–chemical characteristics of the upper soil layer (0–30 cm) at the beginning of the experiments (mean (SE)). Mo (Los Morales), Ra (La Rábida). See also Table S1.

A randomized complete block design was established in each field trial, with four blocks per trial. Each taxon was present in each block within an experimental unit. Therefore, there were four experimental units in each field trial, which were called replicates. The experimental unit was of a different size in each of the four field trials. It consisted of 3–4 parallel lines containing 6–30 plants per line, with a spacing of 0.6–1.0 m between plants and 2.0–3.3 m between lines; the crop density ranged, therefore, from 3787 to 5556 plants per hectare (Table 3, Figures S1–S3). In the Mo1 and Mo2 trials, three adjacent uncropped areas with natural vegetation (predominantly weeds) were selected as controls for the purpose of taking soil samples during the study period (Figure S1).

Table 3.

General characteristics of the four field trials at the two locations, Los Morales (Mo) and La Rábida (Ra). See also Figures S1–S3.

Before planting, soil preparation and the eradication of pre-existing weeds consisted of a deep plowing at 50 cm, shallow tillage (harrowing), pre-emergent herbicide application (Oxifluorfen 24%, 2.5 L ha−1), and a standard fertilization with N (75 kg ha−1), K (62.3 kg ha−1), P (32.7 kg ha−1) and S (24 kg ha−1), corresponding to a 15–15–15 (12 S) ratio fertilizer (N–P2O5–K2O, plus 12 SO3). Subsequently, after planting, fertilizers were added by fertigation: N (50 kg ha−1 year−1), K (41.5 kg ha−1 year−1), P (21.8 kg ha−1 year−1), S (16.0 kg ha−1 year−1), 3 kg ha−1 year−1 of Fe–Zn–Mn (4.5%–1.5%–0.5%) chelated by EDDHA, 100 g ha−1 year−1 of Cu (14%) chelated by EDTA, 50 g ha−1 year−1 of H3BO3 and 5 g ha−1 year−1 of (NH4)2MoO4. Sulfur was supplied for facilitating the absorption of Fe, Zn and Mn, since they seem to be somewhat locked-away from plants, as symptoms of foliar interveinal chlorosis were observed. The only experiment that deviated from this general fertilization guideline was Mo2, since it was designed with the main purpose of evaluating treatments that include a mixture of a nitrogen-fixing species (Robinia pseudoacaia) with a non-nitrogen-fixing species (Populus × euroamericana). However, it was decided to supply nitrogen in the fertilization schedule of the Mo2 trial by reducing the amount applied by half (i.e., 37.5 kg ha−1 of N before planting and 25 kg ha−1 year−1 from the second year on), because the viability of the R. pseudoacacia-nitrifying bacteria’s symbiosis was not totally guaranteed, since it was the first time this species was planted on this site; the proportions of nitrogen in the plant derived from the atmosphere vary among seed sources [46]; and plant growth had to be facilitated in these nutrient-poor soils. The other nutrients were supplied at the same quantities as in the other trials. The experiments Mo1, Mo3 and Ra4, on the contrary, had as their main objective to compare the productivity of different taxa, belonging to the same or different species.

The Mo1 and Mo2 experiments were established in 2011, while Mo3 and Ra4 were in 2015 (Table 3). At the time of planting (from mid-March to mid-May), the vegetative material consisted of:

- Bare root nursery seedlings, 50–70 cm in length, of two Robinia pseudoacacia L. taxa (the improved cultivar “Nyírségi” and commercial nursery plants from Germany), Populus nigra L., Ailanthus altissima (Mill) Swingle., and Ulmus pumila L;

- Paulownia plants of 15–20 cm in height (Paulownia fortunei (Seem.) Hemsl., clone “UHU”) coming from root cuttings;

- Bare root nursery plants, 50–70 cm in length, coming from rooted hardwood cuttings of Platanus × hispanica Mill. ex Münchh;

- Poplar hardwood cuttings of 20–25 cm in length belonging to five hybrid clones—four clones of Populus × euroamericana (Dode) Guinier (clones “Adige”, “AF2”, “Oudenberg”, “I214”), and one clone of Populus × interamericana van Broekhuizen (clone “Raspalje”).

Weeds were mechanically controlled again three months after planting, but fortunately it was unnecessary to control them thereafter, due to the high planting density and the rapid growth of the new sprouts after harvesting. Every year, from early June to mid-September and according to the rainfall, 160–480 mm of water was supplied by drip irrigation in order to offset summer drought and achieve an annual water supply (rainfall + irrigation) of around 700–800 mm. The adjacent unmanaged areas did not receive any agronomic practices (soil preparation, weeds control, fertilization, irrigation, etc.), but they were left under their natural vegetation. The application of pesticides was unnecessary in the Ra4 trial; however, in the Mo1 and Mo2 trials, occasionally during the whole period studied (only in two years) a pest caused by Xanthogaleruca luteola that affected Ulmus pumila had to be controlled, by spraying 0.5 L ha−1 of Deltamethrin at 2.5% every time.

2.2. Shoot Growth and Biomass Assessment

Stem diameter (D, measured 10 cm above ground), height (H) and the number of stems from the stump (NSt) were annually measured in 4–20 plants per replicate depending on the trial. In order to avoid the edge effect, only plants belonging to the middle line were measured (Table 3, Figures S1–S3). Once D and NSt were measured, the quadratic mean diameter (QMD, i.e., the average diameter of the plant per plant basal area) and the plant basal area at the measurement height of D (BA, m2 ha−1) were obtained. The basal area of the plant (BA) was calculated by adding the cross-sectional area of all of the main stems of the plant and dividing by the area of land occupied by the plant (Aplant), where Aplant is the result of dividing 10000 (m2 ha−1) by plantation density (plants ha−1).

For the Mo1, Mo2 and Ra4 trials, two short rotations were analyzed by annually measuring plant growth for 3–4 years after planting (1st rotation), and also measuring growth every year in re-sprouted shoots for 3–4 years after cutting (2nd rotation), whereas only the 1st rotation was analyzed for Mo3 (Table 3). In addition, phenology was assessed on a monthly basis by recording the presence of reproductive organs (developing or ripe), and the status of the twigs and buds (developing or resting).

The plant age was identified according to the following convention: RijSk, where (i) indicates how many times a stump has been cut, (j) the age in years of the stump-roots, and (k) the age of the main shoots at the time of measuring. For instance, in the Mo1 experiment, R04S4 means a 4-year-old plant that has never been cut after planting, while R18S4 means a plant whose roots are 8 years old, but it was cut after the fourth year, so the aboveground part is only 4 years old.

Biomass production was assessed at the end of winter (February to March), before spring bud break, from the measured data of D and H. For this purpose, specific allometric equations relating D and H to the shoot dry weight were developed for these plants, similar to those performed in other studies [20,47,48,49], by cutting and weighing a sample of shoots with a stem diameter (D) ranging from 10 to 140 mm. The dry weights of aboveground woody (AGWB) and non-woody (AGNWB) parts were assessed separately, after being oven-dried at 65 °C. As leaves had fallen several months ago, non-woody biomass was reduced to dehydrated ripe legumes, and was only present in Robinia pseudoacacia. Total dry weight (AGTB) was determined as AGWB + AGNWB. Since all studied taxa belonged to deciduous species, none of them maintained leaves on the measurement dates (February to March), which coincide with the dates on which the harvest takes place. Different equations were tested with combinations of D, H and/or D2 as predictor variables, and most of them yielded an excellent fit. However, since the stem diameter is very easy to measure and the power equation using D as the only predictor (AGWB = a·Db) also showed a very good fit (Table 4), it was thus used for estimating AGWB. The strong correlation (r > 0.90, p < 0.001) obtained between D and H for the type of stems assessed (Table S2) allowed us to remove H from the biomass weight estimation equation. A single allometric relationship was used to evaluate the AGWB, on a dry weight basis, of the same taxon in any of the trials (Table 4).

Table 4.

Allometric equations relating the stem diameter at 10 cm above ground (D, mm) to the aboveground dry weight (AGWB, g). AGWB = a·Db. Stems with D ranging from 10 to 140 mm were used. Significance level, p < 0.001 for all cases. n = sample size.

2.3. Physical–Chemical Properties of Soil and Plant Biomass

Soil samples were taken at the beginning of the assays (original soil) and also at the end of every rotation, in March–April, under four taxa (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Ulmus pumila, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ailanthus altissima). Four soil subsamples per replicate and taxa (0–30 cm depth) were taken with a soil core between planted lines, 1 m apart from the central line. The litterfall and soil mineral layer were then separated, and the subsamples belonging to each taxon/treatment and replicate were pooled. For the Mo1 and Mo2 experiments, soil samples in adjacent uncultivated areas (control areas, Figure S1) were also taken. The dry weight of the litterfall layer (i.e., leaves, shoots and reproductive organs partially decomposed) was therefore also quantified.

Litterfall was washed with distilled water, oven-dried at 65 °C to a constant weight, ground and stored at room temperature (15–20 °C) in sealed containers until being analyzed. Soil samples were air-dried at room temperature for one month, milled and sieved (2 mm mesh). Concerning the plant biomass (roots and aboveground part), four shoots per replicate of Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Ulmus pumila, and Robinia pseudoacacia were randomly sampled at the end of every rotation and pooled for analysis. In the same way as for litter, these samples were washed, oven-dried at 65 °C, ground and stored at room temperature, and their properties were analyzed. The physical–chemical characterization of litterfall, plant biomass and mineral soil was performed following standardized methods (Table S3).

2.4. Valuation of Biomass and Determination of the Economic, Energy and CO2 Balances of the Production Process

Aboveground woody biomass was ground (Woodstock 3PH, Smartec®, Italy) and sieved to a 0.2–5.0 mm particle size in order to create homogenous samples. Then, for the purpose of increasing the economic value of the biomass yielded, pellets were manufactured using a pelleting press (PLT-400, Smartec®, Italy). The moisture content was set to 130 g kg−1 with a bulk density of 183, 268 and 216 kg m−3 for “AF2”, R. pseudoacacia and U. pumila, respectively, and an operating temperature from 95 to 105 °C. Die channels six millimeters in diameter were used; the inlet part of the channel was a cone-shaped opening 3.5 mm deep with 70° angles; the active part was 26 mm long for “AF2” and 22 mm for R. pseudoacacia and U. pumila, so the compression ratios were, respectively, 4.33 and 3.67. After that, the ash content, bulk density, length and diameter, mechanical durability, chemical composition and moisture content of the pellets were assessed according to the standard ISO 17225-2:2014 [50].

Without attempting to delve deeper into the socio-economic and environmental analysis, this paper provides a brief environmental, energy and economic analysis of a biomass supply chain based on an experimental poplar/black locust/Siberian elm plantation grown as an SRC in an area under a Mediterranean climate. Calculations consider a plantation cycle of 15–17 years with 4–5 rotations (harvests) every 3–5 years. The rates and wood price, fuel consumption, and machinery performance (Table 5) have been obtained from the companies TRAGSA [51] and ENCE [52], two of the largest Spanish forestry companies, and from recent studies carried out by other authors and institutions [11,12,43,53,54,55,56,57]. We have also taken into account the calculation methodology used by previous studies [58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Soil preparation, herbicide, plants and planting, harvesting, materials and the installation of irrigation system, grubbing and land clearing were considered as fixed costs, whereas irrigation (water and energy), fertilizer and transport were taken as variable costs. Financial costs, land, and extra costs have not been considered.

Table 5.

Technical characteristics of machinery, operation inventory and costs, and energy equivalent.

2.5. Data Analysis

The dependent variables (DV; i.e., D, H, NSt, etc.) were evaluated in the same plants for several years during the first two rotations after planting; therefore, our data structure resulted in repeated measurements for each plant, and repeated measures ANOVAs were applied [65]. Hence, as the within-plant observations were autocorrelated, a model in which the plant (within-replicate) was considered a random effect was used. The first and second rotations were analyzed separately. Taxa (TX, in the Mo1, Mo3 and Ra4 trials) or treatment (TR, in the Mo2 trial) were included as fixed effects. The annual growth was evaluated by introducing the evaluation period (year, Y) as a fixed effect. The replicate (Rep) growth differences were also assessed, which represents the block effect. The model also included the pairwise and triple interactions between main effects as fixed effects. It was tested in advance that the data met the assumptions of normality and sphericity. To evaluate the among taxa/treatments comparisons, the Tukey HSD test was used in order to differentiate the homogeneous groups. Significant differences were established at p < 0.05. Thus, the full models had the following structure:

or,

DVijkl = Repi + Yj + TXk + (Rep × Y)ij + (Rep × TX)ik + (Y × TX)jk + (Rep × Y × TX)ijk + εijkl

DVijkl = Repi + Yj + TRk + (Rep × Y)ij + (Rep × TR)ik + (Y × TR)jk + (Rep × Y × TR)ijk + εijkl

Soil properties were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA (Mo1, Mo2 and Mo3 trials) by considering the fixed effects of taxon/treatment (TX—each of the taxa evaluated and natural vegetation; TR—each of the mixture treatment assessed in Mo2 trial) and rotation (Year). A three-way ANOVA was conducted for the Ra4 assay by considering TX, soil layer (SLY: 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm) and rotation (Year) as fixed effects. Their pairwise and triple interactions were also included in the model as fixed effects. Since soil sampling did not take place at exactly the same point every year, a repeated measures ANOVA was not applied. A one-way ANOVA was applied to the nutrient content of litterfall and biomass sampled at the end of the studied periods, the taxon (TX) being the fixed effect. Significant differences were also established at p < 0.05. To evaluate the among-taxa/treatments and year comparisons the Bonferroni test was used. The free R software and the SPSS 19.0 software (IBM® SPSS Statistics®) were used for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Shoot Growth and Biomass Production

Mortality was very low in all trials (<5%) during the study period, except for Robinia pseudoacacia, which was 12% as a whole. It took place primarily during the first summer after planting, so the failed plants were replaced the following fall. No measurement took place on replanted plants. Except for Populus × euroamericana “AF2” and Ulmus pumila, all taxa showed slight symptoms of interveinal foliar chlorosis [66], which were more pronounced for R. pseudoacacia and Populus × interamericana “Raspalje”. This deficiency was corrected by applying chelates of Fe, Zn and Mn. As expected for deciduous species like these, the usual winter frosts in Los Morales (−7 to −9 °C) did not cause damage to the plants. However, an occasional frost of −13.6 °C in January 2012 severely damaged the aerial part of Paulownia fortunei “UHU”, although the plants did not die and new shoots sprouted the following spring. Ailanthus altissima and Ulmus pumila were the taxa that best withstood water stress (caused by a short heat wave event or a short delay in irrigation). The other taxa suffered partial wilting and defoliation.

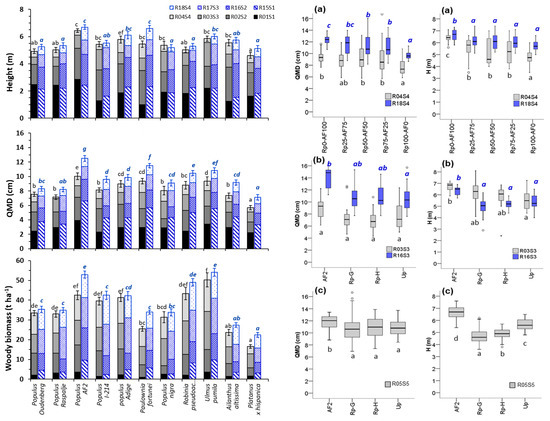

The increase in height (H) and stem diameter (D), as well as biomass production, differed significantly both between taxa (p < 0.001) and between years (p < 0.001) for all the trials, while no significant differences were obtained between replicates within a trial or for the main effect interactions (p > 0.150). All experiments considered, the average heights achieved by the more productive taxa were 5–7 m, while average stem diameters exceeded 8 cm, reaching up to 12 cm in the Mo3 trial, and maximum diameters of 15 cm were obtained (Figure 1, Table S4). Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila stood out for their biomass production in the Mo1 trial.

Figure 1.

(Left) Mean annual values of plant height (H), quadratic mean diameter (QMD) and woody biomass dry weight of the aboveground part (AGWB) for the eleven taxa assessed in the Mo1 trial. The bars indicate the standard error (SE) at the end of the fourth year of each rotation (R04S4 the 1st rotation, and R18S4 the 2nd one); (Right) Boxplots of quadratic mean diameter (QMD) and plant height (H) in the Mo2 (a), Ra4 (b) and Mo3 (c) trials for the last year of each rotation. First rotation (grey colors) and second rotation (blue color). Different letters indicate significant differences between taxa or treatments (p < 0.001) at the end of each rotation (black letters for the 1st rotation; italic blue letters for the 2nd rotation). AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Rp-H and Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance, respectively); Up (Ulmus pumila). Treatments: 100% AF2 (Rp0-AF100); 25% Rp-G + 75% AF2 (Rp25-AF75); 50% Rp-G + 50% AF2 (Rp50-AF50); 75% Rp-G + 25% AF2 (Rp75-AF25); 100% Rp-G (Rp100-AF0).

Overall, the H and D increments were greater in the first two years after planting or after cutting, but this was not the case with the increase in biomass, which was greater during the second–fourth years after planting, or the second–third years after cutting (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 and Figure S4). It should be noted that biomass production the first year after cutting (second rotation) was much more vigorous than that obtained the first year after planting (first rotation). In spite of the significantly smaller diameters in the second rotation than in the first one (Table S4 and Figure S5), the number of stems sprouted from the stump (NSt) increased in the second rotation, resulting in larger QMD and basal area and, consequently, increasing the biomass production. On average, NSt ranged from 1.02–1.88 at the end of the first rotation to 2.71–4.89 in the second (only diameters greater than 15 mm were counted). Therefore, QMD was quite similar to D in the first rotation, but more than 80% greater than the mean diameter in the second one. On average, for all species as a whole and the four field trials, BA increased by 55% from the first to the second rotation (from 35.3 to 55.7 m2 ha−1).

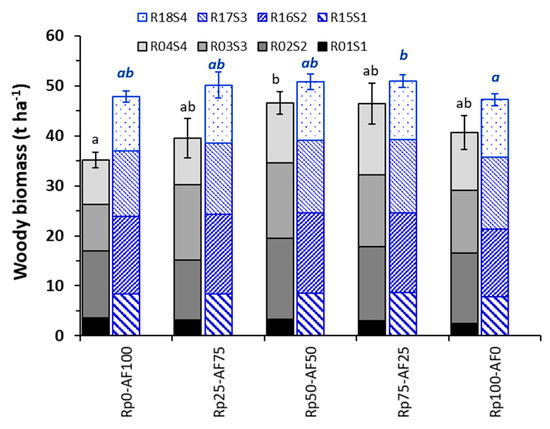

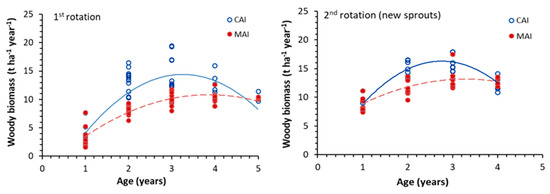

Figure 2.

Mean annual values of woody biomass dry weight of the aboveground part of the plant (AGWB) for the four mixture treatments assessed in the Mo2 trial. First rotation (grey colors) and second rotation (blue color). The bars indicate the standard error (SE) at the end of the fourth year of each rotation (R04S4 for the 1st rotation, and R18S4 for the 2nd). Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.001) at the end of each rotation (black letters for the 1st rotation; italic blue letters for the 2nd rotation). Treatments: 100% AF2 (Rp0-AF100); 25% Rp-G + 75% AF2 (Rp25-AF75); 50% Rp-G + 50% AF2 (Rp50-AF50); 75% Rp-G + 25% AF2 (Rp75-AF25); 100% Rp-G (Rp100-AF0).

Figure 3.

Mean annual values of woody biomass dry weight of the aboveground part of the plant (AGWB) for the four taxa assessed in the Ra4 (left) and Mo3 (right) trials. First rotation (grey colors) and second rotation (blue color). The bars indicate the standard error (SE) at the end of the third (Ra4 trial) or the fifth (Mo3 trial) year of each rotation. R03S3 for the 1st rotation and R16S3 for the 2nd one in the Ra4 trial; R05S5 for the Mo3 trial. Different letters indicate significant differences between taxa (p < 0.001) at the end of each rotation (black letters for the 1st rotation; italic blue letters for the 2nd rotation). AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Rp-H and Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance, respectively); Up (Ulmus pumila).

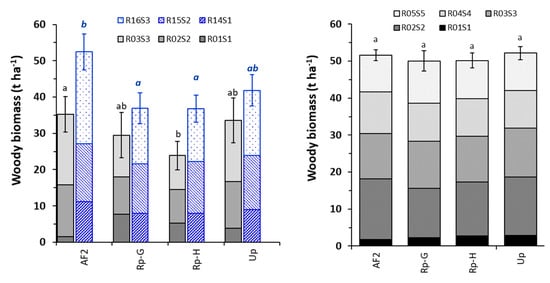

Figure 4.

Current annual increment (CAI) and mean annual increment (MAI) of the woody biomass dry weight of the aboveground part of the plant (AGWB) throughout the period studied for the 1st and 2nd rotations. Data from all field trials and four taxa are shown as a whole. Taxa: AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Rp-H and Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance, respectively); Up (Ulmus pumila). Equations of the fit lines: (i) 1st rotation, y = −2026x2 + 13,185x − 7043 (R2 = 0.69) for CAI, and y = −0.894x2 + 6902x − 2487 (R2 = 0.85) for MAI; (ii) 2nd rotation, y = -2427x2 + 13,381x − 2151 (R2 = 0.65) for CAI, and y = −0.824x2 + 5413x + 4280 (R2 = 0.62) for MAI.

Considering Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila, the mean annual increment (MAI) was about 9–11 t ha−1 year−1 at the end of the first rotation, but increased to 12.5–14.5 t ha−1 year−1 at the end of the second one. However, current annual increments (CAI) up to 15-20 t ha−1 year−1 were obtained (Figure 4 and Figure S4). On average, the second rotation increased biomass production by 10–40% compared to the first (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Regarding the treatments with a mixture of taxa in the same planting line (Mo2 trial), it should be highlighted that the treatments with a 50–75% proportion of the nitrogen-fixing species improved the total biomass production the first rotation, although this positive effect was a bit diluted in the second rotation (Figure 2). From the second year (Robinia pseudoacacia) and the third year (Ulmus pumila) after planting, the production of reproductive organs began to be important, representing up to 8% of aboveground biomass at the end of the rotation. At harvest time, the litter layers averaged 942 (115), 1027 (103) and 1054 (96) kg ha−1 year−1 of dry matter for Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila, respectively, without significant differences among field trials.

3.2. Physical–Chemical Characterization of Soil and Plant Biomass

Many of the physical–chemical characteristics analyzed in the uppermost layer (0–30 cm) of the initial soils (Table 2 and Table S1) did not show significant differences when they were measured again after several years of cultivation (first and second rotation), neither for the main effects nor for their interactions (0.052 < p < 0.970). The only exception was the significant TX × Year interaction for organic matter in the Mo1 trial (p = 0.013). However, some of the properties did show significant differences (Table 6), mainly for Year, but also for TX or TR and soil depth (SLY).

Table 6.

Significance level (p values) of the fixed effects of the two- and three-way ANOVA used to evaluate soil characteristics for each assay carried out. Measurements took place at the end of the 1st and the 2nd rotations for Mo1, Mo2 and Ra4 trials, while for Mo3 trial it was measured in the middle (3rd year) and at the end (5th year) of its 1st rotation.

Considering the evolution of the upper 30 cm of the soil during the first and second rotations, for all taxa as a whole, the following trends can be pointed out (Table 2 and Table 7):

Table 7.

Average values, for all the taxa as a whole, of some physical–chemical characteristics of the upper soil layer of the soils (0–30 cm) at the end of the 1st and 2nd rotations for Mo1, Mo2 and Ra4 trials, while for the Mo3 trial (1) these were measured in the middle (3rd year) and at the end (5th year) of the 1st rotation. The asterisks mean significant difference from the initial soil. In such cases, (+) and (−) mean that the measured parameter significantly increased or decreased, respectively, during the cultivation period. ns indicates non-significant differences with respect to the initial soil.

- A significant increase in exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), organic carbon (OC), N content and available K content. The increase in ESP was evident at the end of the first rotation (3–4 years), but those of OC, N and K took 5–8 years to differentiate from the initial soil;

- The opposite trend was obtained for C/N ratio and the contents of P and active limestone—that is, a significant decrease over time;

- For the rest of the properties analyzed in the initial soils, no significant differences were obtained for the studied period (5–8 years, depending on the experiment);

- In the Ra4 assay, those cases in which differences between the two soil layers (0–15 and 15–30 cm) were significant were due to a higher mineral nutrient content (+ 40–75%), greater OC (+ 130–160%) and lower ESP (−28%) in the shallowest horizon (0–15 cm) than in the deepest.

Finally, regarding the differences in soil properties due to the cultivation of different taxa, we can conclude that: (a) in the Mo1 and Mo2 trials, the few cases in which the differences were significant were due to differences between the cultivated taxa and the non-cultivated land, while the soil under the different cultivated taxa did not differ from each other for the studied period; (b) no significant differences were obtained between taxa in the Mo3 trial for nutrient and OC contents; and (c) in the Ra4 trial, higher N and P contents, greater ESP and lower C/N ratio for Robinia pseudoacacia (mean values 0.07%, 36.6 mg kg−1, 17.1% and 7.92, for N, P, ESP and C/N, respectively, at the end of the second rotation) than for Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana “AF2” (0.06%, 27.3 mg kg−1, 10.1% and 9.35, respectively) were obtained.

Regarding the physical–chemical and energetic properties of the harvested biomass, as well as the roots and the litterfall (Table 8), it should be noted that:

Table 8.

Physical–chemical and energetic characteristics (mean (SE)) of Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila, expressed on a dry weight basis, for aboveground woody biomass (AGWB), roots and litterfall, and all the trials as a whole. HHV, LHV: high and low heating value, respectively. Bdp, pellets bulk density. MDup, pellets mechanical durability. Moisturep, pellets moisture. WdB, wood density including bark. na, not analyzed.

- No significant differences were found between different trials (p > 0.060), and therefore the mean value from the four trials as a whole has been shown for each taxon;

- Significant differences between taxa were obtained for N, Ca, S, Fe, Cl and Ash contents (p < 0.040), although these differences were not very high in absolute terms. Robinia pseudoacacia stands out for its high N and low Ca contents, and high wood density;

- According to the ISO 17225-4 standard [67], the chipped woody biomass is of high quality, since it is harvested without leaves and has a low bark percentage (12% for Robinia pseudoacacia, 15% for Ulmus pumila, and 14% for Populus × euroamericana “AF2”);

- Due to their physical–mechanical and energetic properties (heating values; bulk density, mechanical durability and moisture of pellets), the highest-quality pellets (i.e., ENplus-A1 for domestic use) could be obtained for the three species studied according to standard ISO 17225-2 [50]. However, the chemical properties (N, S, Cl or ash contents) devalue their quality to commercial ENplus-B or Industrial grade pellets. ENplus-A2 quality pellets could be manufactured from debarked wood of these three species, since it contains ≤0.5% N, ≤0.05% S, ≤0.02% Cl and ≤1.2% ash;

- Considering the Mo1, Mo3 and Ra4 trials as a whole, the average amounts of N, P and K removed with the aboveground woody biomass harvested during the studied period were 53.7, 10.8 and 35.0 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively. The nutrient contents in the litterfall (11.5, 1.3 and 2.2 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively) and roots (47.1, 4.6 and 15.6 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively), as well as the new amounts accumulated in the uppermost layer of the soil (0–30 cm) (57.9, −5.5, 36.7 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively), must be added to those contained in the AGWD, which amounted to 170.2, 11.2 and 89.5 kg ha−1 year−1 during the study period. Since in this study the root biomass has not been evaluated, in order to estimate it, averages value of the AGWB/root dry matter ratio of 2.03, 1.70 and 2.10 have been considered for Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, respectively, according to the results reported by other authors for plants of similar size [68,69,70];

- Taking into account that, on average for all the trials as a whole, the amounts of N, P and K supplied by fertilization (62.3, 27.2 and 51.7 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively) and by the irrigation water (24.4, 0.6 and 0.9 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively) were 86.7, 27.8 and 52.6 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively—for instance, in the case of N there were 83.5 kg ha−1 year−1 in the plants and in the soil layer, whose origin has not been determined.

3.3. Economic, Energy and CO2 Emission Balances of the Production Process

The technical characteristics of machinery, cultivation practices, frequencies and costs, as well as energy equivalent and materials used in the cultivation process, are shown in Table 5 and Table 9. In order to elaborate an approximation of the economic and energy costs and the CO2 emissions that the biomass production entails (Table 10), the following assumptions have been taken into account:

Table 9.

Crop assumptions deduced from each SRC field trial carried out: duration of crop rotations and cycles, cultivation practices, used material and application frequencies.

- The average biomass production of Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila as a whole in the SRC field trials carried out was considered for the estimates (Table 10);

- Although only one to two rotations have been studied in each field trial, the calculation has been extrapolated to four to five rotations, to complete a cycle of at least 15 years (Table 9). Biomass production and cultivation works from the third to the fourth–fifth rotations have been considered the same as for the second rotation;

- The biomass produced will be harvested, chipped and transported by truck over a distance of 25 km;

- The equivalent selling price of the chipped dry biomass, taken to the factory, has been estimated at EUR 82 t−1;

- The valves, filters, dosing pump, irrigation pump, pressure gauges, plastic pipes (PE, PVC), installation, etc., of the irrigation system have been taken into account in the economic costs. However, only plastic pipes have been considered in the assessment of energy costs and CO2 emissions;

- Diesel combustion releases 2.65 kg of CO2 per liter; the average C content of the harvested biomass is 50.5%; 1 tonne of C is equivalent to 3.67 tonnes of CO2; 1 kg of diesel is equivalent to 42.71 MJ, and its density is 0.85 kg L−1; the energy to CO2 conversion factor, corresponding to the Spanish electricity mix of 2019, is 241 g of CO2 released per kWh generated.

According to Table 10 and the assumptions aforementioned, the Ra4 trial improved the economic, energy and CO2 emissions ratios (that is the incomes/costs, energy generated/consumed, and CO2 fixed/released ratios) by around 2.9%, 8.1% and 3.5%, respectively, compared to Mo1; the Mo3 trial increased the economic ratio by 2.3% compared to Mo1, with similar environmental costs; in the case of the Mo2 trial (whose cultivation practices were similar to Mo1 in all aspects except in the nitrogen supplied, which was reduced by half), if it is considered that the Rp50–AF50 and Rp75–AF25 mixing treatments average the same amount of biomass as the Mo1 trial, then the Mo2 cultivation practices reduce economic costs by 4.5%, energy consumption by 12.4%, and CO2 emissions by 12.5% compared to Mo1.

In the Mo1 and Mo3 trials, the first rotation ended with negative cash flow (−570.0 and −356.4 EUR ha−1 year−1, respectively), but the investment showed profits after harvesting the second rotation (57.2 and 270.9 EUR ha−1 year−1), that is, at the 8th and 9th years after planting, respectively. However, in the Ra4 trial, economic losses persisted until the second rotation (–968.7 the 1st and −236.1 EUR ha−1 year−1 the second rotation), for which the profits were not achieved until the third rotation, in the 9th year.

Considering all the cultivation practices together, fertilizers accounted for 27–31% of the total cost, harvesting 17–21%, seedlings 17–18%, irrigation material 13–14%, transportation around 8.3%, stump removal and clearing at the end of the cycle over 4.4%, and the remaining 10% for the rest of mechanical works and water pumping. For energy consumption and CO2 emissions, the manufacture of fertilizers accounted for 35–38% of the total costs, the manufacture of irrigation plastic materials 24–26%, water pumping 21–22%, the harvest 7–9%, transportation 4–5%, and the rest of activities and materials around 4.5%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Plant Growth and Biomass Production

All the studied taxa are well adapted to the experimental growing conditions, as demonstrated by the growth rates and survival (>95%). The size reached by the plants (i.e., D, H) and the annual biomass yielded in these field trials (mean annual increments of about 12–14 t ha−1 year−1 for 3–5 years rotations, and CAI up to 15–20 t ha−1 year−1 according to Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) are lower than the highest mean biomass production (20–50 t ha−1 year−1) reported in the Iberian Peninsula with other woody crops, such as Eucalyptus, kenaf or Leucaena [11,12,30,59,71,72], but it is within the highest production range reported for the taxa studied [18,19,20,23,73,74]. However, under conditions of high water and nutrient availability, mean biomass yields of around 20 t ha−1 year−1 can be obtained with hybrid poplar clones [18,75,76]. It should be noted that in this study, the total aboveground dry biomass, which includes branches and bark and excludes leaves, is assessed. A larger H and D did not always imply more biomass production, since the latter is affected by wood density. For example, despite Paulownia fortunei “UHU” being one of the taxa that achieved the largest size, the biomass produced was overcome by many other taxa (Figure 1), because of its low wood density (0.282 kg dm−3) and the hole inside the stem. Bringing all this together, and the damage caused by frosts, this species is not recommended under a climate with cold winters; at the very least, it would be necessary to test the clones first before starting a commercial plantation for energy purposes. Similarly, due to their low productivity, the use of Ailanthus altissima and Platanus × hispanica is not recommended. On the contrary, the establishment of SRC commercial plantations of Populus × euroamericana, Robinia pseudoacaia and Ulmus pumila under these environmental conditions is recommended. However, in areas with mild winters, such as La Rábida, biomass production can be exceeded by evergreen species such as Eucalyptus sp. [11].

Considering the differences among taxa, on the one hand, Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Robinia pseudoacaia and Ulmus pumila stood out in terms of biomass yield from the other deciduous species assessed (Figure 1). However, the differences between these three outstanding taxa were small in absolute value, and not significant in many cases, although they were in some others. For this reason, the discussion of results is shown together in most of the cases, differentiating between taxa only for those properties in which the differences were significant. Regarding Populus, the differences between clones make it advisable to carry out a previous analysis to select the clones best adapted to the climate and soil of the area to be planted, with special attention paid to drought tolerance [76,77]. It seems that it showed a tendency toward greater biomass production than R. pseudoacacia and U. pumila under conditions of good water availability (Figure 4 left), in addition to having a better aerial structure that facilitates the mechanization of the harvest [64,75]. Regarding Robinia pseudoacacia and Ulmus pumila, selection and improvement programs must still be developed based on survival, growth, delay in the change of phase from juvenile to mature, straightness of the main trunk, scarce branching, small thorns in the case of black locust, etc. [78,79], and, if possible, sterile hybrids that eliminate their invasive character. Ulmus pumila showed greater tolerance than Robinia pseudoacacia and Populus × euroamericana during the short water stress events suffered by the plants, showing physiological plasticity in adapting to drought by increasing leaf thickness and thus reducing water loss [80], hence its greater drought tolerance than the other two species. The climate change scenarios predict an increase in temperatures and aridity in the Mediterranean environment, which will undoubtedly affect plant growth and mortality, as well as sustainability and economic balance, since small differences in tree mortality have an important effect on land expectation value [15,81]. Therefore, the choice of the appropriate taxon and the development of genetic improvement programs are of vital importance.

On the other hand, with regard to the crop treatments assessed (monoculture or mixture of species), there was evidence that a mixed plantation that includes 50–75% of the N-fixing species may improve biomass production, as other authors have also reported for these species [19,80]. The positive effect of the mixtures 50Rp–50AF and 75Rp–25AF from our study in terms of biomass yield (7–32% higher than that of the Robinia pseudoacacia and Populus × euroamericana “AF2” monocultures) indicates the presence of competitive reduction or facilitation as mechanisms that increase biomass production under certain mixture ratios [44], and points to the importance of mixing the two species within the same row in this type of plantation [19]. However, in our study, the effect of the mixed plantation could have been slightly diminished, probably due to the N supplied with the fertilization, the N already present in the soil of the plantation site (5120 kg ha−1 in the 0–30 cm of the upper layer at the Mo2 trial), as well as the N provided by the irrigation water. This aspect should be studied in greater depth, testing different mixture ratios of R. pseudoacaia/P. × euroamericana or R. pseudoacacia/U. pumila depending on whether the growing conditions are of greater or lesser water availability, respectively.

The lower planting density in the Mo3 trial, compared to Mo1, did not increase biomass yield, but it did increase the diameters of the trunks of the plants, which would improve the quality of the biomass due to its lower proportion of bark. Under cold winter Mediterranean climates (Mo trials), rotations of 5 years (the first) followed by 4 years (the second and subsequent) could be recommended, in order to optimize biomass yield and save harvest costs. However, in areas with a climate with mild winters and a longer growing season (Ra trials), rotations can be shortened by up to 3 years without impairing biomass yield. The biomass produced by the one-year-old sprouts after cutting (R11S1) was always greater than that one year after planting (R01S1), with slight but significant differences among taxa, probably due to the planting shock, which slows growth for a few months until the root system expands and fully contacts the soil [82]. As a result, coppicing can invigorate plant growth after harvesting related to the breakdown of apical dominance and the following development of several new sprouts from dormant buds that had retained their juvenile stage. Not only the hormonal imbalance induced by cutting the shoots but also the higher proportion of earlywood vessels in the new stems might prove this response [12]. The proliferation of thinner stems after the st rotation, with higher stem number per stump, can also facilitate the mechanization of the harvest, since it largely depends on the D and H [83]. The fact that Robinia pseudoacaia and Ulmus pumila produce fruits from the 2nd or 3rd year (up to 8% of aboveground biomass) would reduce biomass production. Therefore, coppicing at the end of the rotation can improve vegetative growth for at least 1–2 years after harvesting by maintaining the juvenile stage of the plants, during which the production of reproductive organs is reduced, thus increasing the woody biomass yield in the following rotation.

4.2. Physical–Chemical Characteristics of Soil and Biomass and CO2 Sequestration

The mineral nutrient contents in plants (Table 8) are within the ranges reported by other authors for these plant species and cultivation practices, and the soils are typical farmlands with intermediate characteristics (Table 2 and Table 7), without any extreme value outside the normal range of a high-pH calcareous soil [41,80,84,85,86]. Regarding the mineral composition of the three species evaluated, it should be noted that Robinia pseudoacacia, the N-fixing species, showed higher N and lower Ca contents than the other two taxa (Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana “AF2”).

Overall, for all trials and taxa as a whole, taking into account the tested experimental conditions, in which water and fertilizers were supplied, and despite the intensive production of lignocellulosic biomass, the cultivation practices made it possible to obtain a commercially demanded product, while improving soil properties. In just over 5–8 years, significant increases in parameters as important as the soil content of N, K and organic C were observed, compared with the original soil or with the uncultivated land. All this improves soil fertility, as well as the sequestration of C in stable forms in the soil, due to the cultivation system [11,12,41]. The average increase in C in the uppermost layer of the soil (0–30 cm) of this study (0.36–0.83 t ha−1 year−1 of C) is equivalent to sequestering 1.3 t ha−1 year−1 of atmospheric CO2 in the Ra4 trial, and about 3.0 t ha−1 year−1 in the Mo1, Mo2 and Mo3 trials, thus allowing the mitigation of the effects of climate change by acting as a true sink for C. The reason for the lower increase at Ra than at Mo could be due to the fact that the former has a warmer and more humid climate, which increases soil respiration, hence the C consumption and CO2 emission, in spite of presenting high biomass and litterfall production [87,88]. The capacity to sequester C obtained by SRC plantations of Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana is within the average range reported for other crops—0.28–1.39 t ha−1 year−1 of C [89]. The positive effect of SRC on soil C and fertility contrasts with some negative effects of biomass production in traditional forest systems at sensitive sites [15,16,40,81]. These differences can be due to the lower level of organic matter in farmlands (<2%) with respect to forest soil and the fertilization designed to compensate for the extractions with the harvested biomass.

Additional atmospheric C has been fixed, but has not yet been mineralized into soil layers as it is in the litterfall and roots [48,86,90]. This accumulation of litterfall is close to that reported by other authors for SRC, and a good proportion of the litter C and other mineral nutrients represents a reservoir that will slowly be released into the soil [10,11,86,91], which, when added to those provided by the fine roots [92], will support the productivity of the sites. Only in litterfall, between 0.40 (Mo1) and 0.54 (Ra4) t ha−1 year−1 of C were accumulated, which is equivalent to 1.48 and 1.97 t ha−1 year−1 of CO2, respectively, although without significant differences among field trials. Likewise, the decrease in the C/N ratio to 8.6–10.4 is indicative of an adequate N release rate, and the decrease in active limestone will help to overcome the iron chlorosis observed in some taxa, as well as the decrease in the edaphic content of P [80,93,94]. The most negative aspect found in the field trials carried out has been the decrease in the soil P content (on average −5.5 kg ha−1 year−1), despite having supplied an average of 27.7 kg ha−1 year−1, and that the P contents in the harvested biomass (10.8 kg ha−1 year−1), the roots (4.6 kg ha−1 year−1) and the litter (1.3 kg ha−1 year−1) add up to 16.7 kg ha−1 year−1. Therefore, there are 16.5 kg ha−1 year−1 of P not absorbed by plants (i.e., 59.6% of the P supplied) that may have been locked by the active limestone or leached to deeper layers of the soil, out of reach of the roots. Special attention must be paid to phosphorous fertilization to ensure the sustainability of the production system. Another aspect to take into account is the slight increase in ESP, mainly at La Rábida, since this site presents values close to 15%, the threshold above which Na becomes a problem, affecting the mineral nutrition of other cations, soil dispersion and, consequently, soil crusting [95].

At Los Morales, the effects on the soil of the cultivated taxa and the mixture treatments did not differ significantly from each other in the period studied in any of the three trials (Mo1, Mo2 and Mo3). There was not even any distinction between the N-fixing species and the other species. This may be due to the fact that soil evolution processes take many years to show differences. However, the eight years for which the Mo1 and Mo2 trials lasted were enough to differentiate them from the uncultivated soil with natural herbaceous vegetation, demonstrating that a properly managed short-rotation coppice does not degrade the soil, but can improve it. However, at La Rábida, with a more humid and warmer climate than Los Morales, although the evolution of the soil under the four taxa was favorable for the 6 years studied, the effect of Robinia pseudoacacia differed from that of Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana. In this case, R. pseudoacaia showed higher contents in N and P, higher ESP, and lower C/N ratio, than U. pumila and P. × euroamericana after the second rotation. The latter is consistent with other studies [80,96], and may be due to the fact that when black locust grows on nutrient-poor soils, it supplements soil nitrogen pools, increases nitrogen return in litterfall, and enhances soil nitrogen mineralization rates associated with an abundance of high nitrogen and low lignin leaf litter [96]. However, it is important to keep track of the soil’s evolution since the microorganism community could be modified [94,97].

It has been estimated that up to 76% of Robinia pseudoacaia N can come from atmospheric N2 fixation [34]. As a consequence, a large amount of inorganic N fertilizers can be substituted with the nitrogen fixed, thus reducing the high energy and economic costs related to their manufacturing [43]. Considering an average production of about 18 t ha−1 year−1 of dry biomass (AGWB + roots + leaves and fruits) and the biomass nitrogen content, around 93 kg ha−1 year−1 of N are needed to support plant growth, of which Robinia-Rhizobium root nodules can fix 71 kg ha−1 year−1. Consequently, the 71 kg of inorganic N fertilizer saved means saving about EUR 237 ha−1 year−1 (473 kg of fertilizer 15–15–15, EUR 0.5 kg−1) and 3195 MJ ha−1 year−1 during fertilizer manufacturing [43,53], and reducing the CO2 emissions into the atmosphere by about 214 kg ha−1 year−1. The role of Robinia pseudoacacia as a nitrogen-fixing species makes it an interesting species to be used in SRC energy crops, as a monoculture or mixed with other species, at least for degraded soils. However, its invasive nature suggests managing it with caution or looking for other alternative species that offer similar results. It was mentioned above that there are 83.5 kg ha−1 year−1 of N in the upper layer of the soil, the origin of which has not been verified. In the case of Robinia pseudoacacia, this could be explained by the fixation of atmospheric N. However, as other species are also evaluated in monoculture, other possible explanations are that it could come from soil layers deeper than 30 cm; N-fixing herbaceous species that grow from November to March, when the leaves of the trees have fallen; the experimental error itself, since a variation of only 0.01% in the soil N content, due to the sampling process or laboratory analysis, represents 54.5 kg ha−1 year−1 of N. As such, this will need to be assessed more precisely. In addition, the grasses that grow from November to March between the plantation lines (Figure S5) could be grazed by sheep, which would increase the production and the sustainability of the system.

The aboveground woody biomass from the three species (Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana), which can be made into chips and pellets, has evidenced its appropriateness for energy use according to the international standards (Table 8), due to the energy and chemical characteristics, as well as the physical–mechanical properties, of the pellets and chips [98,99]. Its most immediate use is in thermal boilers or cogeneration plants after transformation into chips, offering a high-quality biomass since it is harvested without leaves and possesses a bark percentage of less than 15%, similar to the percentage reported for other poplar hybrid clones [100]. The resulting pellets possessed the characteristics of hardwood species [11,12,98,101,102,103], and were of a better quality than pellets from non-woody species, but did not reach the highest standardized quality of pellets derived from conifer debarked wood because of the chemical composition, which is one of the factors that affects the bonding quality of the biomass particles during pelletization [104,105]. Considering only the physical–mechanical properties of the pellets, they could provide the best quality for domestic use (ENplus-A1 commercial quality [99]). Nevertheless, the slightly high N, Cl, S and ash contents limit their suitability for domestic use to commercial ENplus-B quality, yet they are not suited for industrial purposes, according to international standards [99,106]. Therefore, this woody biomass presents high commercial quality thanks to the fact that it is harvested without leaves, the organs that possess the highest concentrations of harmful minerals, such as N, S, K and Cl, responsible for many undesirable reactions during combustion that damage furnaces and power boilers [107]. Consequently, transforming this biomass into pellets endows it with added commercial value and, taking into account the chemical properties, it would be possible to obtain pellets of the highest commercial quality (i.e., ENplus-A1) if 10–20% of this biomass is mixed with 90–80% of debarked coniferous wood (volume ratio), depending on the raw materials and the drying system. In addition, if possible, the aboveground woody biomass of Robinia pseudoacacia, Ulmus pumila and Populus × euroamericana should be debarked and used as raw material in the manufacture of pellets, in order to obtain ENplus-A2-quality pellets, or in combination with the debarked wood of species that present low enough nutrients and ash contents [102,103]. However, currently, the SRC production systems make debarking the plants difficult when they are harvested, due to their size and structure.

The determination of the rotation (harvest frequency) is of special relevance as it determines the distribution of the biomass (stems of different thickness, bark proportion, twigs) and the nutrient extraction. This last factor is relevant both in maintaining soil fertility [15,16,40,81] and in the proportion of some elements detrimental to its energy use (Cl, N, etc.) or its use in some industrial transformation processes [8,27].

4.3. Economic, Energy and CO2 Emission Balances

Overall, according to the results obtained and the proposed cultivation assumptions, with 15–17-year-long productive cycles and harvests every 3–5 years, the economic and environmental balances were shown to be positive (Table 10). The ratios greater than 1 (incomes/costs, energy generated/consumed, CO2 fixed/released) mean that the intensive cultivation of black locust, Siberian elm and hybrid poplar for energy purposes (SRC energy crop) under the Mediterranean climate can be considered sustainable over time, since it maintains or slightly improves the soil properties, while obtaining socio-economic and environmental benefits, such as the reuse of abandoned lands, rural development, the reduction of CO2 emissions and the mitigation of climate change [61,89,90,91,92,93,108]. The planning of multi-year cycles using species that sprout from the stump limits soil tillage by reducing the latter to the initial preparation of the land, and contributes to soil erosion control [59]. Despite the not too high yields, the investigated production system on degraded soils had a positive energy balance (205–237 GJ ha−1 year−1), producing 22–24 times more energy than it consumed, and in spite of the fact that the harvested biomass is burned, after a production cycle (15–17 years), 1.46–1.54 times more C remains sequestered in the production system than the production process releases into the atmosphere, in accordance with other studies [59,61,108]. With all this, the cost of the energy generated (EUR 3.1–3.2 GJ−1) is extremely competitive compared to other energy sources.

The resulting earnings (EUR 328–392 ha−1 year−1) are usually lower than those obtained from food crops when fertilizers and irrigation water are supplied, and are of the same order of magnitude as the current state subventions received by farmers. If we add to this that the initial investment does not begin to be recovered until the 8th–9th year after planting, national governments must take measures to incentivize the production of this renewable resource [58,62]. As the Mo3 trial increased the profit by 2.3% compared to Mo1, with similar environmental costs, it is possible to save some money on the initial investment by reducing the initial planting density from about 5500 to 3800 plants ha−1. Likewise, reducing the amount of inorganic N fertilizer, which can be saved in a culture of a N-fixing species mixed with another with high biomass production (Mo2 versus Mo1 trials), means reducing economic costs by at least 4.5%, and environmental costs by close to 12.5%. Therefore, in order to reduce the economic and environmental costs derived from the manufacture of N fertilizers, the inorganic fertilizer must be adjusted to the minimum amount necessary to support growth and replace the nutrients removed by the harvested biomass [11,63]. In the same way, any cultivation practice that promotes growth and reduces the supply of water and fertilizers as well as the cost of harvesting will have a major impact on the operation activities that have had the greatest weight in the economic, energy and CO2 emission balances (i.e., fertilization, irrigation, harvesting), as has also been reported by other authors [31,58,61,64]. So, to achieve higher annuities, several options could be proposed, such us the extension of the rotation cycle for 1–2 years when possible; the selection of highly efficient taxa in the use of water and nutrients; the optimization of water and nutrient supply, as well as the plantation density; the improvement of the stem structure (straightness, branching) that facilitates the harvest mechanization; the use of a mixed plantation that includes a N-fixing species; the use of a two-step harvesting system; transformation into quality chips or pellets that add value to biomass. In addition, it remains to be studied whether more than three or four cuts can be applied to the stumps, which would improve the expected earnings. As many countries have established guidelines for the sustainable harvesting of forest biomass in traditional forest systems in order to limit nutrient exports and the effect on diversity [7,16], it would be advisable to develop good practice guidelines for SRC in order to reduce the possible negative effects. Some of the aspects that should be addressed include the sites where SRC can be implanted, the distance to possible sensitive areas, the precautions to be taken with invasive species, the extension of the SRC harvest periods, the maximum area harvested per year, the correct management of fertigation, etc.

5. Conclusions

- The biomass yield under a Mediterranean climate for short-rotation coppicing crops of Ulmus pumila, Robinia pseudoacacia and Populus × euroamericana “AF2” ranges from less than 5 to more than 20 t ha−1 year−1 (on average 12–14 t ha−1 year−1), depending on irrigation and soil quality;

- At least 800 mm of water (rainfall + irrigation) and about 60 kg ha−1 of N (fertilization) are required annually;

- This production system not only produces high-quality woody biomass, but, after a cycle of 15–17 years, on average it would also be able to:

- -

- Generate 205–237 GJ ha−1 year−1 net (equivalent to 57–66 MWh ha−1 year−1, or to the replacement of 5647–6528 L ha−1 year−1 of diesel);

- -

- Offer a profit of about EUR 1.5 per euro invested;

- -

- Sequester in the 0–30 cm layer of mineral soil 1.5 kg of C per kilogram released into the atmosphere.

- After the first two rotations evaluated (5–8 years), the upper layer of the mineral soil (0–30 cm) compared to the original soil sequestered 0.36–0.83 t ha−1 year−1 of carbon (equivalent to 1.3–3.0 t ha−1 year−1 of CO2);

- Nutrient inputs and outputs should be taken into consideration by the plantation managers in order to offset the outputs contained in the harvested biomass, and to prevent any loss in soil fertility and productivity;

- Degraded soils could be improved if the crop is properly managed, and any cultivation practice that promotes growth, reduces irrigation, fertilization and the cost of harvesting, and increases the added value of the final marketed product will have a major impact on the economic, energy and CO2 emission balances;

- The use of N-fixing species, such as Robinia pseudoacacia, and mixed plantations with the other two species are important aspects to be considered in future plantations.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f12101337/s1, Figure S1: Schematic representation of the experimental design of the Mo1 (left) and Mo2 (right) field trials. Mo1 field trial: four hybrid clones of Populus × euroamericana (Dode) Guinier (clones “Adige” (Adg), “AF2” (AF2), “Oudenberg” (Odg), I214 (I214)); one hybrid clone of Populus × interamericana van Broekhuizen (clone “Raspalje” (Rj0); Pf, one clone of Paulownia fortunei (Seem.) Hemsl. (clone “UHU”); RpH (Robinia pseudoacacia, improved cultivar “Nyírségi”); commercial nursery plants of Populus nigra L. (Pn), Ailanthus altissima (Mill) Swingle. (Aa), Platanus × hispanica Mill. ex Münchh. (Pxh), and Ulmus pumila L. (Up). Mo2 treatments (combinations of the five different species compositions): 100% AF2 (Rp0-AF100); 25% Rp-G + 75% AF2 (Rp25-AF75); 50% Rp-G + 50% AF2 (Rp50-AF50); 75% Rp-G + 25% AF2 (Rp75-AF25); 100% Rp-G (Rp100-AF0). Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia, commercial nursery plants from Germany), Figure S2: Schematic representation of the experimental design of the Mo3 field trial. AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Rp-H and Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance, respectively); Up (Ulmus pumila), Figure S3: Schematic representation of the experimental design of the Ra4 field trial. AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Rp-H and Rp-G (Robinia pseudoacacia cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance, respectively); Up (Ulmus pumila), Figure S4: Current annual increment (CAI) and mean annual increment (MAI) of the woody biomass dry weight of the aboveground part of the plant (AGWB) throughout the period studied for the 1st (left) and 2nd (right) rotations and the three taxa. Data from all field trials are shown as a whole. Taxa: Populus AF2 (Populus × euroamericana “AF2”), Robinia pseudoacacia (including cultivar “Nyírségi” and German provenance); Ulmus pumila, Figure S5: (a) 3.5-year-old Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, 1st rotation; (b) 3.5-year-old Ulmus pumila, 1st rotation—the litter layer can be seen on the soil surface; (c) 2.0-year-old Robinia pseudoacacia, 1st rotation—it can be seen the grass grown during the cold season, which can be grazed by sheep; (d) 2.0-year-old mixed plantation of Populus × euroamericana “AF2” and Robinia pseudoacacia, 1st rotation; (e, f, g) 3.0-year-old sprouts of Populus × euroamericana “AF2”, Ulmus pumila and Robinia pseudoacacia, respectively; (h) litterfall of Robinia pseudoacacia; (i, j) wood pellets from Ulmus pumila and Robinia pseudoacacia, respectively, Table S1: Physical–chemical characteristics of the upper soil layer at the beginning of the experiments (mean (SE)). Mo (Los Morales), Ra (La Rábida), Table S2: Relationships between stem diameter measured at 10 cm above ground (D, mm) and plant height (H, cm). H = a·D2 + b·D + c·D ranged from 6 to 170 mm. r = Pearson coefficient. Significance level, p < 0.001 for all cases. n = sample size, Table S3: Standard technical methods and instruments used to assess the physical–chemical properties of plant material, soil and litterfall, Table S4: Morphological characteristics (average (SE)) of the main stems emerging from the stumps at the end of the 1st (R04S4 plants) and the 2nd (R18S4 plants) rotation for the Mo1 assay. Dmax, maximum stem diameter among those emerging from a stump; NSt, number of stems; BA, basal area. The four variables showed significant differences between taxa and between rotations, p < 0.001.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., J.A. and R.T.; methodology, S.P.A., M.F. and R.T.; software, S.P.A.; validation, M.F., R.T. and J.A.; formal analysis, S.P.A., R.T.; investigation, S.P.A.; resources, R.T., J.A.; data curation, S.P.A. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.A.; writing—review and editing, M.F., J.A. and R.T.; visualization, S.P.A., M.F. and J.A.; supervision, R.T. and M.F.; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F., R.T. and J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Innovation Ministry (ref. AGL2010-16575) and the Economy and Competitiveness Ministry of Spain (ref. CTQ2013-46804-C2-1-R and CTQ2017-85251-C2-2-R), by FEDER funds of the EU, and by the company ENCE, energía y celulosa S.A. (8%, 6%, 6%, 70%, 10%, respectively).

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Diputación de Granada (Spain) for the donation of farmland for the establishment of the experimental plots in Los Morales, and for the help in the cultivation works; the company Tubocás S.L. for its contribution to the sampling and transport of biomass, as well as to the harvest at the end of each crop rotation; and Biopoplar Ibérica S.L. for the provision of some plant taxa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- United Nations. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session, Paris, France, 30 November–13 December 2015. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2001/oj (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- REN21. Renewable. Global Status Report, Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century, France. Available online: https://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GSR2017_Full-Report_English.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from The Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of The Regions Energy Roadmap 2050/* COM/2011/0885 final */. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex:52011DC0885 (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4a50d774-5e8c-457e-bcc9513357f9b2fb/World_Energy_Outlook_2017.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Antczak, A.; Swierkosz, R.; Szeniawski, M.; Marchwicka, M.; Akus-Szylberg, F.; Przybysz, P.; Zawadzki, J. The comparison of acid and enzymatic hydrolysis of pulp obtained from poplar wood (Populus sp.) by the Kraft method. Drewno 2019, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, B.D.; Brown, K.; Helmisaari, H.-S.; Vanguelova, E.; Stupak, I.; Evans, A.; Clarke, N.; Guidi, C.; Bruckman, V.J.; Varnagiryte-Kabasinskiene, I.; et al. Sustainable forest biomass: A review of current residue harvesting guidelines. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2021, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska, E.; Lipkiewicz, A.; Niemczyk, M.; Dubowik, M.; Boruszewski, P.; Przybysz, P. Influences of fiber and pulp properties on papermaking ability of cellulosic pulps produced from alternative fibrous raw materials. J. Nat. Fibers 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIC. Strategic innovation and research agenda (SIRA) Bio-based and renewable industries for development and growth in Europe. In A Public-Private Partnership on Bio-Based Industries; Biobased Industries Consortium, Ed.; Biobased Industries Consortium: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/other/legal_basis/jtis/bbi/bbi-sira_en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Bogdanski, A.; Dubois, O.; Jamieson, C.; Krell, R. Making Integrated Food-Energy Systems Work for People and Climate; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; p. 116. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2044e/i2044e.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Fernández, M.; Alaejos, J.; Andivia, E.; Vázquez-Piqué, J.; Ruiz, F.; López, F.; Tapias, R. Eucalyptus x urograndis biomass production for energy purposes exposed to a Mediterranean climate under different irrigation and fertilisation regimes. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 111, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Alaejos, J.; Andivia, E.; Madejón, P.; Díaz, M.; Tapias, R. Short rotation coppice of leguminous tree Leucaena spp. improves soil fertility while producing high biomass yields in Mediterranean environment. Ind. Crop Prod. 2020, 157, 112911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffell, S.; Verschuyl, J.; Miller, D.; Wigley, T.B. Biofuel harvests, coarse woody debris, and biodiversity—A meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouget, C.; Lassauce, A.; Jonsell, M. Effects of fuelwood harvesting on biodiversity—A review focused on the situation in Europe. Can. J. For. Res. 2012, 42, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]