Abstract

In machine learning, feature selection (FS) is crucial for simplifying data while preserving the variables that most influence predictive performance. Although FS has been extensively studied, addressing it in an unsupervised setting remains challenging. Without class labels, optimization is more prone to slow convergence and the local optima. In particular, unsupervised text FS has received comparatively little attention, and its effectiveness is often limited by the underlying search strategy. To address this issue, we propose a hybrid breeding cooperative whale optimization algorithm (HBCWOA) tailored to unsupervised text FS. HBCWOA combines the cooperative evolutionary mechanism of hybrid breeding optimization with the global search capability of the whale optimization algorithm. The population is partitioned into three lines that evolve independently, while high-quality candidates are periodically exchanged among them to maintain diversity and promote stable, progressive convergence. Moreover, we design an adaptive dynamic accurate probabilistic transfer function (ADAPTF) to balance exploration and exploitation. By integrating the refinement ability of S-shaped transfer functions with the broader search ability of V-shaped ones, ADAPTF adaptively adjusts the exploration depth, reduces redundancy, and improves the convergence stability. After FS, K-means clustering is employed to assess how well the selected features structure document groups. Experiments on the CEC2022 benchmark functions and eight text datasets, under multiple evaluation metrics, show that HBCWOA attains faster convergence, more effective search exploration, and higher clustering accuracy than its S-shaped and V-shaped variants as well as several competitive text FS methods.

1. Introduction

The explosive growth of web-scale text has created a pressing need to extract meaningful signals from massive corpora. Learning from raw high-dimensional features can degrade accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. Feature selection (FS) has a well-known solution: By removing irrelevant or redundant variables and retaining informative ones, FS provides a concise, discriminative representation of a subset of the original feature space that can improve the reliability and utility of the model [1,2,3]. In text analytics, FS methods are generally classified into two main groups: supervised and unsupervised. Supervised FS methods require labeled corpora and are the natural choice for supervised classification tasks [4,5]. Unsupervised methods operate without labels and serve to cluster documents, discovering latent relationships across a corpus. By removing uninformative dimensions, they reduce dimensionality and can facilitate downstream learning for exploratory tasks [6,7]. The lack of labeled data makes unsupervised FS particularly challenging: Supervised evaluation criteria cannot be applied, and a consensus evaluation metric is still pending, while different algorithms can result in significantly different ”optimal” subsets [8]. In practice, implementation is left to heuristic algorithms, and the lack of standardized benchmarks further hinders comparing different methods to each other [9,10].

From an optimization perspective, FS is generally recognized as an NP-hard binary combinatorial optimization problem [11]. Since exact solutions are intractable, metaheuristics are widely adopted to obtain high-quality approximations within practical time. Representative families include genetic algorithms (GAs) [12], ant colony optimization (ACO) [13], differential evolution (DE) [14], hybrid breeding optimization (HBO) [15], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [16], and the whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [17], all of which are devised to enhance the balance between exploration and exploitation and improve the robustness of FS. For instance, Msallam and Idris [18] proposed a binary fire hawk optimizer (FHO) that effectively handles unsupervised text-based FS problems. In unsupervised clustering settings, Nachaoui et al. [19] developed hybrid PSO (HPSO), which is an enhanced PSO variant that incorporates dynamic weights, a constriction factor, and a penalty term to mitigate premature convergence and local trapping, achieving higher clustering accuracy and more reliable feature subsets.

Despite their success, metaheuristic-based FS still faces two persistent difficulties: approaching globally competitive solutions and maintaining stable convergence behavior. This has motivated hybrid frameworks that more effectively coordinate exploration and exploitation. HBO introduces a three-line cooperative co-evolution mechanism inspired by the heterosis effect in hybrid rice breeding and has been applied to FS [20], the 0–1 knapsack problem [21], and various global optimization and engineering tasks [22]; however, it may exhibit limited search diversity and unstable convergence [15]. WOA [23], in contrast, is attractive because of its simple structure and few control parameters, and has been extensively studied. We build on WOA because its lightweight operators and minimal parametrization make it a practical baseline for high-dimensional sparse text scenarios while also providing a clear foundation for systematic hybrid enhancements. Numerous WOA variants have been proposed by incorporating adaptive parameter control [24], chaotic maps [25], or opposition-based learning [26], as well as by integrating Lévy flights [27] and differential operators [28] to alleviate premature convergence and strengthen exploitation. WOA has also been extended to FS via binary transfer mechanisms and high-dimensional search enhancement strategies [29,30].

In unsupervised text FS for clustering, metaheuristic optimizers are widely used to search compact term subsets, and candidate subsets are typically evaluated using clustering objectives or validity indices. Representative approaches employ GA- [31], PSO- [19], ACO- [32], and DE-based schemes [33], and some further couple feature selection with clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means) for joint optimization [34,35]. Nevertheless, in high-dimensional binary text FS, canonical WOA and its variants may still experience rapid diversity loss and premature stagnation, leading to performance variability across datasets. These observations suggest that combining WOA’s exploration capability with HBO’s cooperative co-evolution may offer a complementary mechanism to mitigate local entrapment and improve convergence stability for text FS.

In binary FS, the design of the transfer function is crucial: It transfers continuous positions to the 0/1 domain and controls the probability of state flips [36]. The implementation of a judiciously crafted transfer function mitigates premature convergence at local optima and ensures an equilibrium between the global exploration and local exploitation phases [37]. Recent research has focused on this component directly. Regularized binary encoding (RBE) achieves better performance than conventional S-shaped and V-shaped functions on UCI [20]. Moreover, S-shaped, V-shaped, and Z-shaped functions have been embedded into a binary FHO for text mining [18], with further enhancements explored in related work. Yet, for complex, high-dimensional issues, many existing designs still lack sufficient stability and adaptability, underscoring transfer-function refinement as an open and promising research direction.

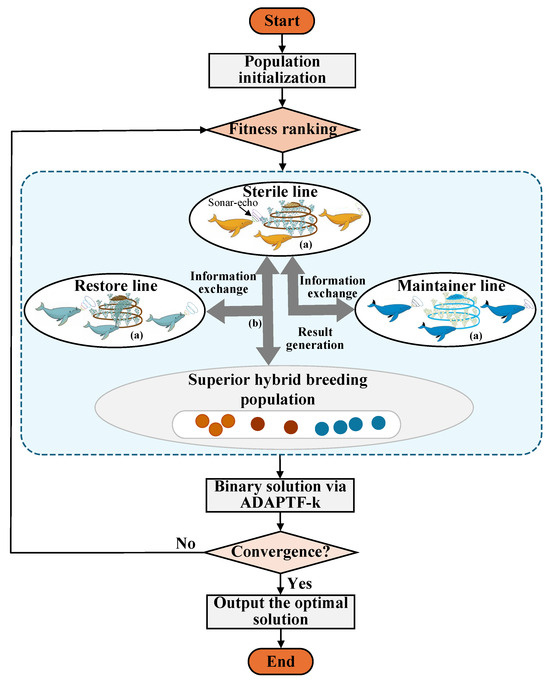

To address the above issues, this paper proposes a hybrid breeding cooperative WOA (HBCWOA), which integrates WOA with HBO to select a compact yet informative feature subset from the original feature space. The population is ranked by fitness and partitioned into three evolutionary lines, within which a sonar-echo–enhanced WOA (SE-WOA) is performed. Periodic information exchange among the three lines enables collaborative evolution until a termination criterion is met. To further adapt the framework to unsupervised text feature selection in a binary search space, we incorporate an adaptive dynamic accurate probabilistic transfer function (ADAPTF), resulting in a binary variant termed B-HBCWOA. Extensive experiments on CEC2022 benchmark functions and six unsupervised text datasets, with comparisons against eight state-of-the-art metaheuristics and two internal variants (S-shaped HBCWOA and V-shaped HBCWOA), demonstrate that B-HBCWOA consistently achieves superior feature-selection quality, more stable convergence behavior, and better overall performance.

This study makes the following key contributions:

- An HBCWOA is proposed. Following the three-line cooperative evolution mechanism in HBO, the division of the population yields three sub-populations, designated as the maintainer line, restorer line, and sterile line. Then, the SE-WOA is run within each line, and the periodic information exchange of elite solutions among the three lines is conducted. Finally, through iterative cooperation among the three lines, the HBCWOA achieves the global convergence and significantly enhances the search ability and the convergence performance for FS;

- An SE-WOA is introduced. With the aid of virtual sonar wave emission and echo feedback, and inspired by the wave attenuation process and interference effect, the SE-WOA endows individuals with the abilities of active perception and adaptive search. Therefore, the SE-WOA can reach the goal more rapidly and enhance the ability of the global search capability compared with that of the standard WOA;

- An ADAPTF is designed. It maps the continuous position to the binary space. Additionally, the local exploitation ability of the S-shaped function and the global exploration ability of the V-shaped function are adaptively combined, and the diversity preservation strategy and the redundancy suppression strategy are also designed. Thus, the search procedure can maintain a balance, which not only explores the new region but also gradually refines the promising solution.

This paper is structured into distinct sections. Following this introduction, Section 2 covers the core tenets of HBO and WOA. The newly introduced framework is then fully described in Section 3. Thereafter, Section 4 offers an interpretation of the experimental findings based on real-world datasets, and the final insights are consolidated in the concluding Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce the key principles of HBO and WOA, providing the background necessary for understanding the proposed method.

2.1. Overview of the Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm

The HBO algorithm was introduced by Ye et al. [15], drawing inspiration from China’s three-line hybrid rice-breeding system. In this method, solutions are ranked based on fitness and assigned to one of three specialized sub-populations. The most fit third constitutes the maintainer line, , while the least fit third forms the sterile line, The intermediate individuals populate the restorer line, Here, each entity, , denotes a position in a D-dimensional search domain, and the subgroup size is given by where N is the total population size.

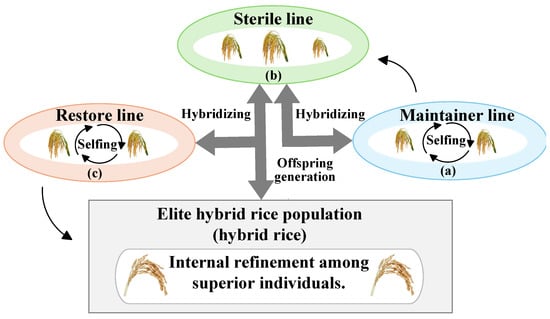

To preserve diversity during evolution, the algorithm incorporates multiple bio-inspired strategies: crossbreeding across maintainer and sterile lines, self-reproduction among restorer members, and a reset mechanism that alleviates premature convergence risks. A structural overview of the HBO framework is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Principal phases of HBO: (a) The procedure begins by initializing the restorer line, which undergoes a self-fertilization process. (b) The sterile line is subsequently produced and crossed with the maintainer line to generate new offspring. (c) The maintainer line is strengthened and preserved through selfing, ensuring population stability.

2.2. Overview of the Whale Optimization Algorithm

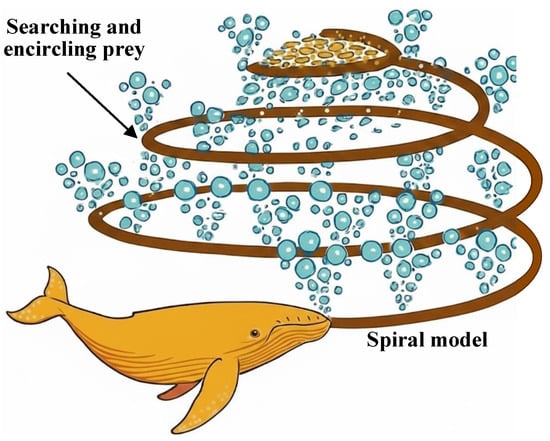

The WOA derives its inspiration from the bubble-net hunting strategy of humpback whales, as depicted in Figure 2. Its operational framework is governed by three core principles: (i) Prey encirclement, which identifies the current best position as the prey and guides the remaining search agents to surround it; (ii) Bubble-net attack: This process is simulated by a spiral-shrinking path that surrounds the prey; it also increases the local search quality. and (iii) Searching for prey: Each whale randomly selects a position as a reference point to search for prey; this helps to diversify the exploration and reduces the risk of premature convergence.

Figure 2.

Humpback whale bubble-net hunting behavior.

By alternatively employing these three mechanisms and successfully navigating the tradeoff between extensive global exploration and intensive local exploitation, WOA guides the search process toward the global optimum.

3. The Proposed Method

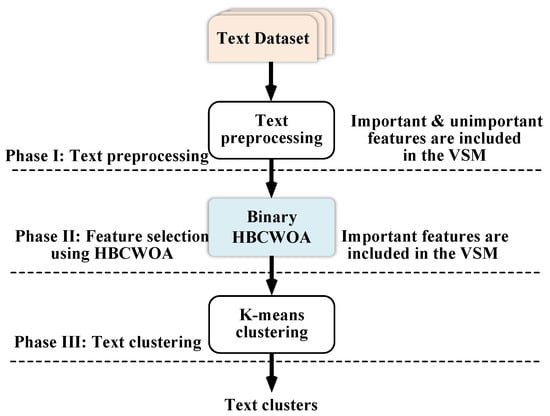

This section presents an FS method designed to identify the most discriminative subset of terms to enhance the clustering task. The best features are delivered as input to the clustering model. By doing so, the problem of the curse of dimensionality in textual data is mitigated, and the validity and reliability of clustering results are enhanced. Figure 3 presents a schematic diagram of the overall workflow of the proposed methodology.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the proposed approach.

3.1. Phase I: Text Preprocessing

In the first phase, raw textual material is normalized. This phase entails four sequential operations: tokenization, stop-word removal, stemming, and term weighting. After preprocessing, each document can be expressed numerically for algorithmic processing.

(i) Tokenization: It decomposes sentences into lexical units (tokens).

(ii) Stop-word Filtering: It removes highly frequent but semantically negligible words, such as pronouns or auxiliaries, thereby reducing the data scale and computation time.

(iii) Stemming: It converts different inflected or derived forms of a word to a common base form.

(iv) Feature Weighting: An importance score for each token is determined by integrating its intra-document frequency with its distribution across the entire corpus. The term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF–IDF) scheme is adopted for this task, as expressed in Equation (1).

Here, quantifies the occurrence frequency of term j in document i. The variable N denotes the total number of documents in the corpus, while is quantified as the document count that contains term j.

At this stage, documents are transformed to a structured format using a vector space model (VSM) [38], representing each text as a multidimensional numerical vector that can be directly processed by clustering algorithms.

3.2. Phase II: Feature Selection Using B-HBCWOA

In this subsection, the overall design of HBCWOA is introduced together with its binary version, and the corresponding solution representation and objective function adopted in this work are also described.

3.2.1. Hybrid Breeding Cooperative WOA

The HBCWOA is motivated by the tri-line cooperative breeding mechanism in HBO. In its design, the population is initially partitioned into three distinct subgroups according to a fitness ranking: the maintainer line, the restorer line, and the sterile line. Within each subgroup, optimization is performed by a sonar-echo-enhanced WOA (SE-WOA), and the subgroups periodically exchange information about their best members to improve the convergence. The flowchart of the B-HBCWOA is shown in Figure 4, and its procedure is as follows:

- (i)

- Tri-line population partitioning.

The population (P) is divided into three subgroups, as shown in Equation (2).

where , , and correspond to the preserving, restoring, and sterile subgroups, respectively. The population size is N, and the parameters , , and specify the proportion of individuals assigned to each subgroup.

- (ii)

- Sonar-echo-enhanced WOA (SE-WOA).

Whales naturally use echolocation (a biological sonar mechanism) to detect prey and navigate in complex environments. Inspired by this behavior, SE-WOA models each candidate solution () by emitting a simulated sonar signal at a given distance (d), as defined in Equation (3).

where is the initial signal strength, and is the attenuation coefficient.

The received signal of individual i is then expressed as shown in Equation (4).

where denotes the distance between individuals i and j, with representing Gaussian noise.

The solution position is adjusted using the information from the received echo, following Equation (5).

where determines the extent of the update, whereas reflects the orientation given by the evaluation feedback.

- (iii)

- Inter-line communication.

To maintain population diversity and promote global exploration, inter-line communication is carried out once every generations. During each exchange, the top individuals from , , and are shared among the subgroups. This cooperative mechanism allows high-quality solutions to diffuse through the population, helping to keep a healthy tradeoff between exploration and exploitation and speeding up convergence toward the optimal feature subset.

3.2.2. Binary HBCWOA

FS is, by nature, a binary decision process in which each feature is either included or omitted. Accordingly, the continuous position vectors produced by the HBCWOA must be projected to a binary search space. To accomplish this mapping, an adaptive transfer function is employed that combines the local refinement ability of an S-shaped function [39] with the global exploration capability of a V-shaped function [40]. This hybrid design enables the simultaneous preservation of population diversity and the attainment of a desired exploration–exploitation equilibrium.

The selection probability for feature j at iteration t is given by Equation (6).

where and indicate the families of S-type and V-type transfer functions, respectively, and represents an adaptive coefficient that increases linearly with the iteration index. The S-shaped transfer function adopts the form , while the V-shaped function is defined by , where governs the steepness of the transition curves. During the early iterations, a lower encourages global exploration through ; as grows in the later stages, local exploitation is strengthened via .

The binary decision variable is selected to be 1 if is higher than a variable () following a uniform distribution (). The conversion is performed following Equation (7).

Here, indicates the selection status of feature j, where 1 denotes selection and 0, omission. This probabilistic approach enables the algorithm to dynamically determine the feature subset size, moving beyond a fixed threshold to significantly improve adaptability and robustness.

3.2.3. Solution Representation

Each candidate solution () is encoded as a continuous-valued vector in the space , which is then transformed to a binary vector () by means of ADAPTF-k. In this binary representation, the value of corresponds to the selection status of feature j: 1 for selected and 0 for not selected. To enforce a fixed subset size, the following cardinality constraint is applied, as shown in Equation (8):

which guarantees that exactly k features are included in each candidate solution. For example, when and , the solution representation is illustrated in Equation (9).

which represents the selection of the first, third, and sixth features.

3.2.4. Objective Function

The fitness function guides the evaluation of the feature subset quality. In this framework, we employ the mean absolute difference (MAD) [18], formulated in Equation (10), to quantify the discriminative power of features.

Here, let m be the feature dimension, n the total number of documents, the value of feature i in document j, and the mean value of feature i (). The key intuition is that features with higher MAD values show greater variability among documents, which contributes to stronger discriminative power. Maximizing is expected to enhance the cluster separability and improve the clustering accuracy.

3.3. Phase III: Text Clustering

After FS, we use the obtained subset as the document-clustering input. Owing to its computational efficiency and straightforward implementation, the k-means algorithm has become a prevalent choice in clustering tasks, motivating our adoption of it in this work [41]. A prerequisite for k-means is the pre-definition of the cluster number (k), which is typically informed by the data prior knowledge or intrinsic structure. The algorithm proceeds as follows: First, k data objects are randomly sampled as initial centroids [42]. Subsequently, each document is assigned to the cluster which centroid is the nearest, as measured by the Euclidean distance. Next, update the centroid of each cluster as the average of its member documents, and then update the cluster memberships in the next step. The above process will continue until the centroids converge and no big change happens. Finally, all the documents will be clustered into k coherent clusters.

3.4. Time Complexity Analysis

The computational cost of our proposed framework can be broken down into three primary stages: The text preprocessing stage’s main cost is TF–IDF feature weighting. Since all n documents should be considered in m-term vocabulary, the cost will be . The FS stage consists of HBCWOA. Since each individual in each iteration should evaluate the pairwise distance and update its position from N individuals in the d dimensional search space, the cost of each iteration will be and over T iterations, will be . Finally, the text-clustering stage uses the k-means algorithm which cost repeatedly assigns n documents to k clusters and recalculates their centroids over I iterations, which is . By combining these three parts, we finally obtain the overall time complexity, as shown in Equation (11).

where n is the number of documents, m is the vocabulary size after preprocessing, d is the feature dimensionality (typically ), k is the number of clusters, T is the maximum number of HBCWOA iterations, N is the population size, and I is the number of k-means iterations.

Scalability discussion. This expression indicates that the computational cost is approximately linear in the numbers of documents (n), features (d), and clusters (k) and linear in the control parameters (T and I), while it is quadratic in the population size (N). Therefore, HBCWOA is expected to scale to moderately larger datasets, but the runtime will increase with n, d, and N. For substantially larger problems, several strategies can be adopted: (i) applying a fast-filter-based pre-selection to reduce the feature space before running HBCWOA, (ii) choosing smaller population sizes and iteration numbers together with early-stopping criteria, (iii) parallelizing the fitness evaluation of individuals, and (iv) using sampling or mini-batch evaluation when n is extremely high. In practice, the main limitation is, thus, the available computational resources rather than the algorithm itself.

4. Experiments

The descriptions of the text datasets, experimental setup—including the environment and configuration of the metaheuristic algorithms—evaluation metrics, comparative analysis of experimental results, ablation study, parameter sensitivity analysis, and significance evaluation are presented in this section.

4.1. Dataset Description

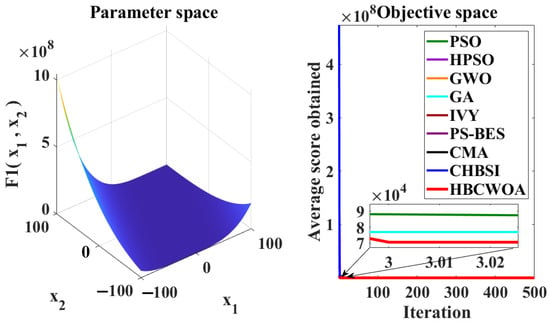

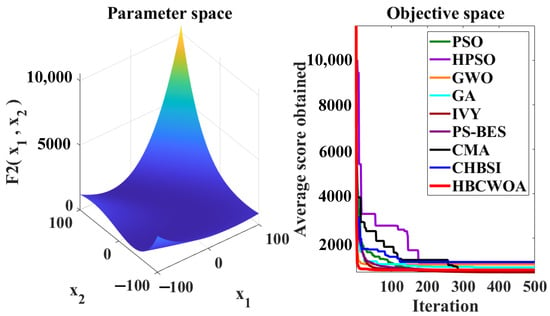

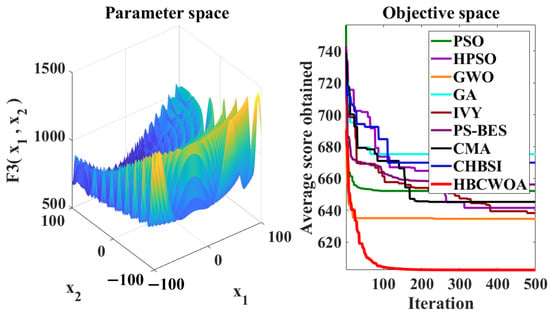

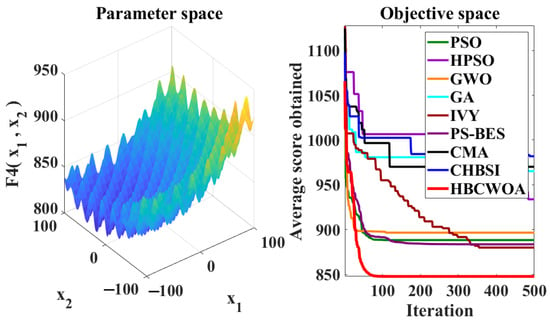

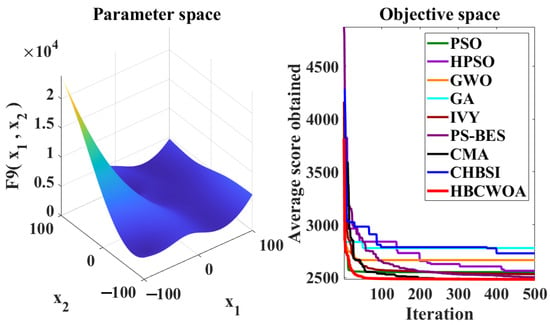

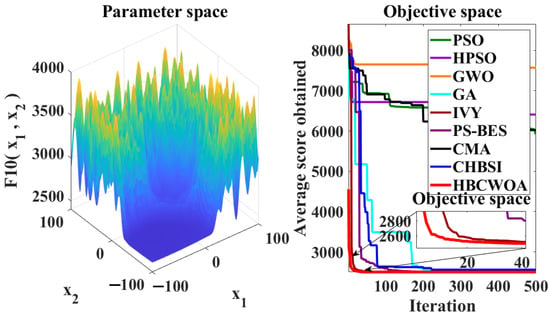

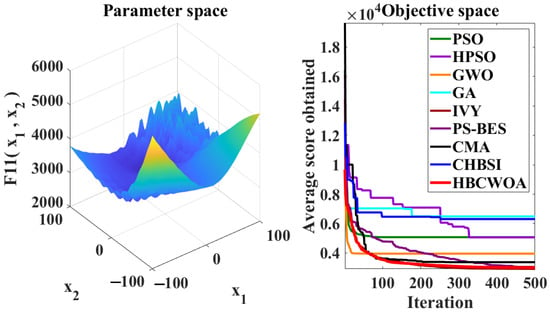

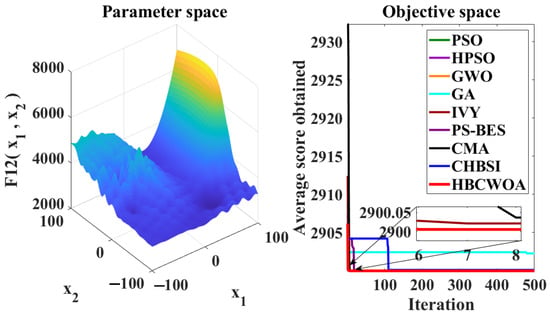

Prior to its application in unsupervised text FS, an initial assessment of the proposed HBCWOA is conducted using the CEC2022 benchmark suite [43,44] to evaluate its overall optimization behavior. The suite comprises four groups of functions—unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition—each representing a different level of search complexity. F1–F2 highlight the convergence and local search efficiency, F3–F6 challenge the global exploration ability, F7–F10 mix diverse components to test adaptivity and balance within complex landscapes, and F11–F12 provide composite scenarios that expose robustness and stability in highly nonlinear environments. Once these characteristics are confirmed, HBCWOA is subsequently applied to unsupervised text datasets to further test its effectiveness and reliability in practical FS tasks.

To mimic realistic high-dimensional text applications, we adopt eight widely used document corpora, which statistics are summarized in Table 1. Re8, Tr21, Tr41, and Tr12 are subsets of the Reuters-21578 news collection, covering different topic hierarchies and numbers of categories. They are representative of news portals or online media platforms where large volumes of articles must be grouped by topic for navigation and recommendation. Reuters-21578 is the full multi-topic news dataset, which reflects large-scale financial or economic news-monitoring scenarios. SyskillWebert consists of webpages labeled with user interests, corresponding to webpage recommendations and personalized filtering in information retrieval systems. Wap contains web advertising pages with 20 topical classes, resembling commercial web content classification and ad-targeting applications. CSTR is a collection of computer science technical reports, modeling digital library and research paper organization tasks.

Table 1.

Description of datasets.

Across these corpora, the feature dimensionality ranges from 1725 to 8460 terms, while the number of clusters varies from four to twenty, which closely matches real-world settings, where text data are high-dimensional, sparsely labeled, and thematically diverse. These datasets, therefore, provide realistic test beds to demonstrate how HBCWOA can be applied to news clustering, webpage categorization, scientific document management, and other unsupervised text-mining problems.

4.2. Comparison Algorithms and Parameter Settings

To evaluate the global search strength of the proposed HBCWOA on the CEC2022 benchmark problems, eight representative metaheuristic optimizers are employed for comparison. These consist of three recently developed hybrid methods—CHBSI [20], CMA [22], and PS-BES [45]—together with one single-strategy approach, IVY [46], and four classical algorithms, HPSO [19], PSO [47], GA [48], and GWO [49]. These methods are widely used metaheuristic optimizers that cover different search paradigms (evolutionary algorithms, swarm intelligence, and hybrid schemes). Furthermore, to verify the adaptability of HBCWOA to practical unsupervised text FS, additional experiments are conducted in comparison with six established text FS methods: S-BFHO [18], HPSO [19], GA [48], PSO [47], MORDC [50], and GWO [49]. Together, these algorithms form a representative set of state-of-the-art metaheuristic approaches for high-dimensional text FS. Their parameter settings are clearly documented in the literature, which allows for fair and reproducible comparisons. We note that classical non-metaheuristic text FS methods (e.g., [51], information gain [52], and mutual information [14]) are typically filter/embedded techniques with different optimization objectives and computational budgets from wrapper-based metaheuristics. Since this study focuses on improving metaheuristic wrapper search and convergence robustness, we restrict the main comparisons to metaheuristic baselines and discuss broader comparisons with non-metaheuristic FS methods as future work.

Parameter configurations for all the comparative algorithms are aligned with their original publications. The key parameters of B-HBCWOA are set following empirical validation and prior studies [20,30]. The initial signal strength is , with noise . Subgroup ratios are , and the weighting function is . Additionally, shapes the S-shaped response, regulates information exchange, and enables communication every five generations. The exploration weight () balances exploration and exploitation. Each run uses a population of 20 agents () and allows up to iterations. All the parameters are empirically chosen to ensure stable convergence and fair comparison across algorithms.

4.3. Experimental Environment

The comparative experiments are carried out on an HP workstation running Windows 11 Professional (23H2), featuring a multi-core CPU, 32 GB of RAM, and GPU support. All the algorithms were implemented in PyCharm using Python 3.8.

4.4. Evaluation Measures

In the field of text clustering, there is no single universally accepted evaluation criterion. In this work, we follow the evaluation framework used in [18,50], which also focuses on unsupervised text FS, and adopt several complementary external measures: reduction rate, accuracy, purity, F-measure, and entropy.

The reduction rate quantifies the dimensionality reduction achieved by FS. Accuracy measures the agreement between the clustering result and the ground-truth labels. The F-measure combines precision and recall to assess the balance between the accuracy and completeness of the clustering, which is particularly important for imbalanced and noisy text clusters. Purity reflects the extent to which each cluster predominantly contains documents from a single true class, while entropy represents the uncertainty in the class distribution within clusters.

Taken together, these metrics provide a comprehensive view of the clustering quality from different perspectives (correctness, compactness, and uncertainty) and have been widely used in previous studies on text clustering and text FS. Using this set of measures, therefore, allows for a balanced assessment of performance and a fair comparison among different algorithms.

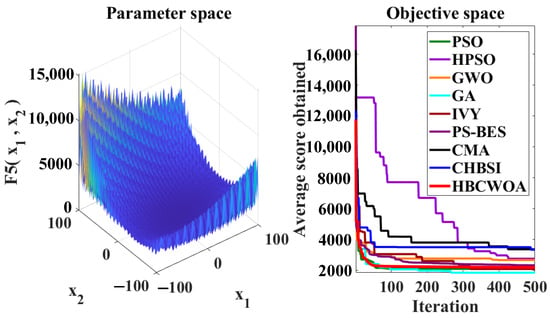

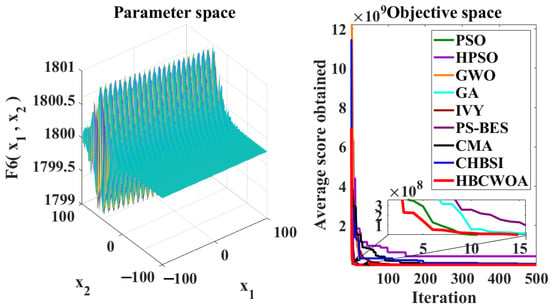

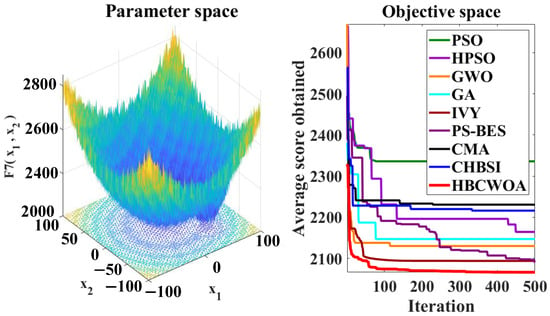

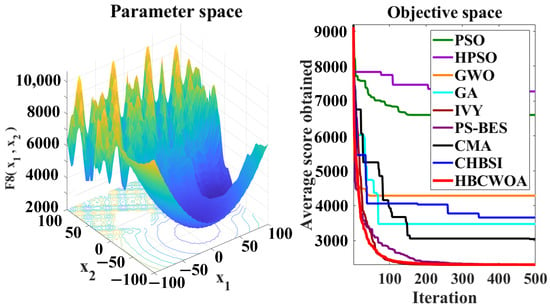

4.5. Global Search Performance Analysis of HBCWOA

The global optimization capability of HBCWOA is assessed through 30 independent runs on the CEC2022 benchmark, configured with 500 iterations in a 20-dimensional space. Under this configuration, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 reveal distinct convergence profiles. Notably, for functions F1, F2, F6, F10, and F12, HBCWOA demonstrates superior performance by achieving near-optimal solutions within about 10 iterations, establishing an early advantage over its counterparts. On F3, F4, F5, and F9, the algorithm becomes stable after around 100 iterations and maintains the best performance, even with a moderate convergence pace. For F7, F8, and F11, HBCWOA achieves near-optimal solutions within 200 iterations, exhibiting strong convergence stability. HBCWOA consistently surpasses competing algorithms on nearly all the test functions, demonstrating its powerful global exploration capability and stable convergence behavior. These findings indicate that HBCWOA has substantial potential for handling high-dimensional, nonlinear, and unlabeled text FS tasks, effectively alleviating local stagnation and convergence instability frequently encountered in unsupervised learning scenarios.

Figure 5.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F1 function of CEC2022.

Figure 6.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F2 function of CEC2022.

Figure 7.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F3 function of CEC2022.

Figure 8.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F4 function of CEC2022.

Figure 9.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F5 function of CEC2022.

Figure 10.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F6 function of CEC2022.

Figure 11.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F7 function of CEC2022.

Figure 12.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F8 function of CEC2022.

Figure 13.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F9 function of CEC2022.

Figure 14.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F10 function of CEC2022.

Figure 15.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F11 function of CEC2022.

Figure 16.

Convergence behaviors of different algorithms on the F12 function of CEC2022.

4.6. Performance Comparison of the Proposed Approach and Other Text Feature Selection Methods

To assess the performance of B-HBCWOA compared with those of other methods, we use the following four metrics: accuracy, F-measure, purity, and entropy. In Table 2, we show the experimental results achieved in ten benchmark text datasets. In each experimental implementation, we initially select the relevant features from the dataset by means of an FS algorithm and then apply K-means to cluster the documents. For the sake of completeness, we also show the results obtained when applying K-means directly to the complete feature space without FS. Both CHBSI and CMA utilize an S-shaped transfer function for the transformation from a continuous search space to a binary domain. The remaining compared methods employ the transfer strategies reported in the original studies. The reported results for each dataset represent the average of 30 independent trials per algorithm, with optimal values emphasized in bold.

Table 2.

Average performances in accuracy, F-measure, purity, and entropy across thirty independent runs in ten text-clustering datasets. The best results are highlighted in bold.

The experimental findings confirm the superiority of B-HBCWOA across most datasets, outperforming all the compared methods on the given evaluation metrics. Except for the CSTR dataset, HBCWOA attains the highest accuracy and purity. In addition, the clustering results obtained on features selected by HBCWOA are better than those obtained by applying K-means on the full feature space. It is also worth noting that, in general, the overall accuracy is not very high, which is mainly due to the fact that the datasets are of high dimensionality and structural complexity, making it harder to find optimal solutions. In addition, the performance of K-means is greatly sensitive to the initialization, specifically, to the choice of cluster centroids.

Entropy is used as an index to evaluate the quality of clustering results. Lower entropy means that the clusters are more coherent, while higher values indicate worse performance.

For most of the datasets, B-HBCWOA attains the lowest entropy value compared with those attained using the other competitors. It is an established practice in text clustering to adopt the F-measure as an evaluation metric. The experimental results shown in the previous section indicate that compared with the other competitors, the proposed algorithm attains a higher average F-measure value, which also suggests that the algorithm has a stronger global optimization capability and, thus, confirms the effectiveness of the algorithm as a whole.

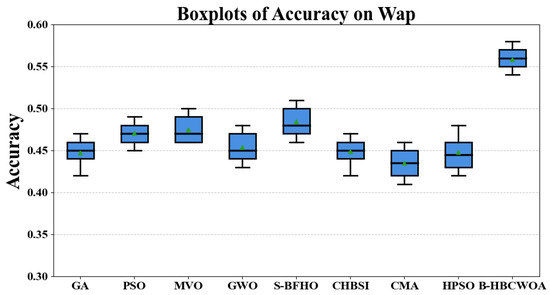

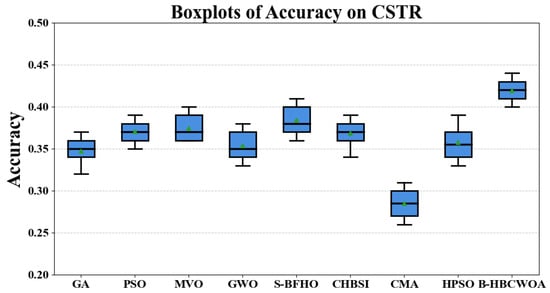

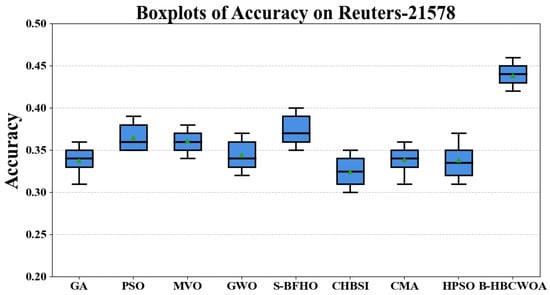

In Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19, we show the boxplots of accuracy achieved using B-HBCWOA and the comparative algorithms on Wap, CSTP, and Reuters_21578. It can be seen that in both datasets, the accuracy achieved using B-HBCWOA is consistently higher than that achieved using the alternative approaches.

Figure 17.

Boxplots illustrating the accuracy results for Wap.

Figure 18.

Boxplots illustrating the accuracy results for CSTP.

Figure 19.

Boxplots illustrating the accuracy results for Reuters_21578.

The sensitivity of a dataset’s search space may cause large performance fluctuations from one dataset to another. That is, the same algorithm may behave differently on the basis of different underlying data distributions. In our experiments, B-HBCWOA obtains the best result in seven datasets and obtains the second best result in CSTR. Overall, it demonstrates a strong capability to achieve a well-balanced interplay between exploration and exploitation during optimization, enabling it to efficiently discover near-optimal solutions for the given problems.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the feature subset sizes selected using various FS methods, where optimal values are bolded. As illustrated, the proposed B-HBCWOA consistently produces the smallest feature subsets across most datasets, demonstrating its strong capability in dimensionality reduction. For instance, in the SyskillWebert dataset, B-HBCWOA selects 1364 features, with a reduction rate of 0.6124, outperforming S-BFHO (1866 features and 0.5703) and GWO (1972 features and 0.5483). Other comparison algorithms generate larger feature sets and correspondingly lower reduction rates than B-HBCWOA. In general, B-HBCWOA exhibits excellent effectiveness in feature elimination, with its reduction rate ranging from 0.5904 to 0.6958, indicating a consistently stable and efficient dimensionality reduction performance.

Table 3.

The selected feature counts and associated reduction ratios yielded by different methods in the benchmark datasets.

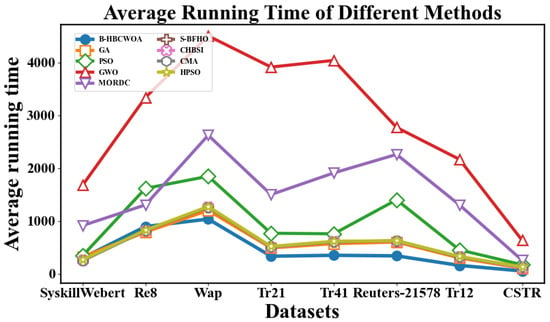

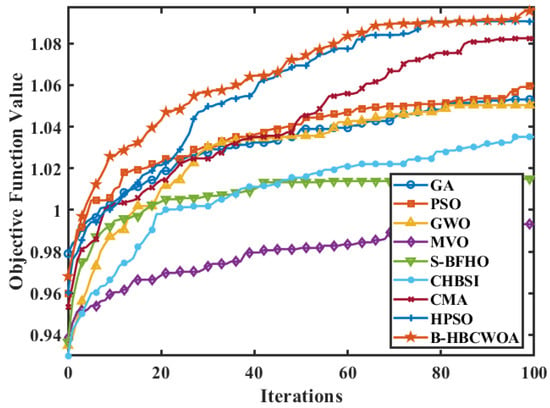

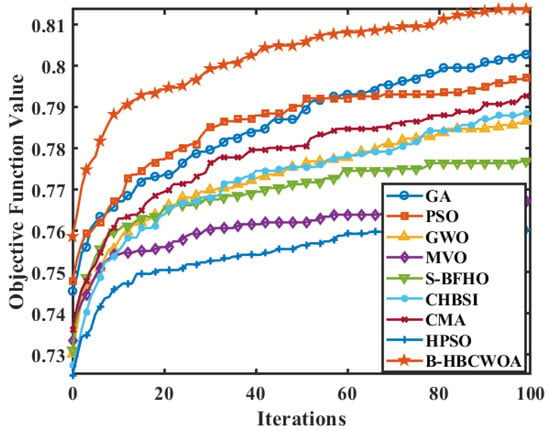

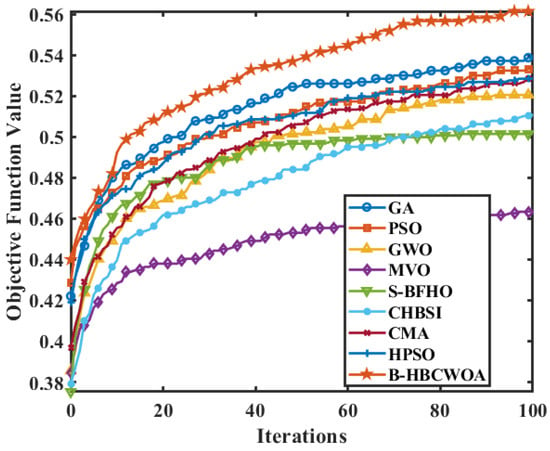

Figure 20 compares the average running times of the proposed B-HBCWOA and other algorithms across all the datasets, averaged over 30 independent runs. In the SyskillWebert and Re8 datasets, B-HBCWOA achieves running times comparable to those of GA and PSO while obtaining noticeably shorter times in the remaining datasets. Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23 present the convergence profiles of the objective function in the Wap, CSTR, and Reuters-21578 datasets, indicating that B-HBCWOA surpasses the competing methods in both the convergence speed and final objective value. The overall performance of B-HBCWOA showcases enhanced efficiency and stability, stemming from its well-maintained equilibrium between exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization.

Figure 20.

Comparison of the average running times of different methods in eight datasets.

Figure 21.

Evolution of the objective function values for various algorithms in the Wap dataset.

Figure 22.

Evolution of the objective function values for various algorithms in the CSTR dataset.

Figure 23.

Evolution of the objective function values for various algorithms in the Reuters-21578 dataset.

4.7. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

We perform a parameter sensitivity study on three datasets with different scales (CSTR, Tr41, and Wap) selected from the eight benchmark corpora. The accuracy and F-measure are used as evaluation metrics, and each setting is run 30 times, with the average being reported. The key parameters of the proposed method include the subgroup ratios (), the maximum iteration number (), the population size (N), and the exploration weight ().

For N, we fix and keep all the other parameters at their default values while varying For , we set (and keep all the other parameters at their default values) and test For , we fix and and evaluate

For the subgroup ratios , and , to avoid destroying the functional balance among the three lines, we only consider reasonably balanced settings, where each component lies between and and These configurations are chosen as perturbations around the default and are consistent with the original HBO design. Very extreme ratios (e.g., one component is >0.5) are unlikely to be used in practice and are, therefore, not included in the sensitivity study.

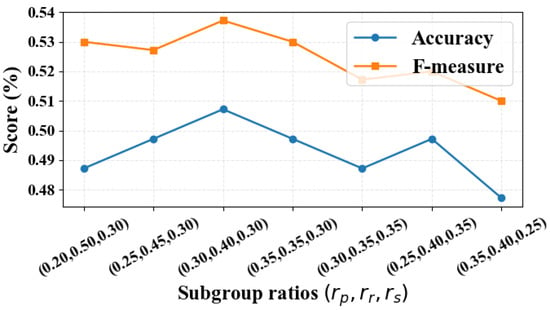

Figure 24 presents the parameter sensitivity of the subgroup ratios and . It can be observed that when , both the accuracy and F-measure attain their highest values, indicating that this is the most effective ratio configuration. Table 4 reports the parameter sensitivity of B-HBCWOA with respect to N, , and ; bold entries denote the best results. As shown, the combination of , , and yields the highest accuracy and F-measure simultaneously.

Figure 24.

The parameter sensitivity of the subgroup ratios , and .

Table 4.

Parameter sensitivity of B-HBCWOA with respect to N, , and .

4.8. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of each component in the proposed B-HBCWOA, an ablation experiment is conducted on three benchmark datasets—Wap, Tr21, and CSTR. The assessment employs four performance measures: the accuracy, F-measure, purity, and entropy. The experimental configurations are defined as follows: (i) B-HBCWOA-I: the tri-population co-evolution strategy in the HBO module is omitted; (ii) B-HBCWOA-II: the sonar enhancement mechanism in the SE-WOA module is excluded; (iii) B-HBCWOA-III: the complete SE-WOA module is removed while keeping HBO; (iv) S-HBCWOA: the proposed adaptive transformation function (ADAPTF) is replaced by an S-shaped transformation function; (v) V-HBCWOA: ADAPTF is replaced by a V-shaped transformation function.

As shown in Table 5, which presents the average results from 30 independent runs (the best results are in bold), we consistently observe that the removal of any component from B-HBCWOA degrades its performance across the accuracy, F-measure, purity, and entropy metrics compared to the corresponding performance metrics of the full model. Moreover, the variants using only S-shaped or V-shaped transfer functions yield inferior results to those obtained by employing the proposed ADAPTF, confirming that ADAPTF provides a more effective mapping from continuous representations to the binary feature selection space.

Table 5.

Accuracy, F-measure, purity, and entropy averaged over three text-clustering datasets.

4.9. Statistical Significance Analysis

To evaluate the differences in performance between B-HBCWOA and competing methods, the F-measure metric is adopted as the primary assessment indicator. Each approach runs 30 independent executions on every dataset to obtain statistically consistent outcomes. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test () is employed to evaluate pairwise algorithmic differences, the outcomes of which are cataloged in Table 6. Statistical significance is declared for p-values of below 0.05; otherwise, the difference is considered as non-significant. Furthermore, the effect size is computed to gauge the practical significance of the differences. These magnitudes are conventionally interpreted as small for values in , moderate for , and large for or greater.

Table 6.

Outcomes of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test conducted on eight datasets, with a significance level of .

For intuitive comparison, the notations ’+’, ’≈’, and ’−’ correspond to cases where B-HBCWOA demonstrates significantly better, statistically similar, or worse performances compared to those of the baseline algorithms. The analysis indicates that B-HBCWOA consistently surpasses most baseline models across the evaluated datasets. For example, relative to S-BFHO, B-HBCWOA achieves superior results in eight datasets, with none showing equal or inferior outcomes. The obtained p-value of confirms the statistical significance of this improvement, and an effect size of reflects a marked advantage in performance.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduces an HBCWOA for unsupervised text FS, a cooperative evolution mechanism composed of three interacting sub-populations, effectively enhancing the search diversity and convergence stability of FS. During optimization, the population is divided into three distinct groups, each evolving independently through an SE-WOA, while periodic exchanges of elite individuals help to achieve a balance between global exploration and local exploitation. In addition, an ADAPTF that merges the characteristics of S-type and V-type mappings is introduced to convert continuous positions to a binary space while adaptively regulating the number of features selected. The binary variant of the HBCWOA is referred to as B-HBCWOA. Experimental results for CEC2022 test functions and eight benchmark text datasets indicate that B-HBCWOA outperforms competing approaches in terms of the accuracy, F-measure, entropy, purity, computational efficiency, and convergence, demonstrating stronger stability and effectiveness. Future efforts will aim to expand the algorithm to address multiobjective and large-scale FS problems and integrate it with deep representation learning to improve the generalization ability and robustness of B-HBCWOA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., Z.Y. and S.Z.; methodology, Y.Z., Z.Y. and S.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z. and S.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and S.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., S.Z. and Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Z.Y.; project administration, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded through grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62376089, U23A20318; 62302154, 62302153), the Program for Scientific and Technological Innovation Teams of Young and Middle-Aged Researchers in Higher Education Institutions of Hubei Province (T2023007), and the Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2023BEB024).

Data Availability Statement

The publicly accessible datasets employed in this research are available at http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/reuters21578, http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~webkb/, and in Ref. [18].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abualigah, L.; Gandomi, A.H.; Elaziz, M.A.; Hamad, H.A.; Omari, M.; Alshinwan, M.; Khasawneh, A.M. Advances in meta-heuristic optimization algorithms in big data text clustering. Electronics 2021, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, N.; Pant, M. Link based BPSO for feature selection in big data text clustering. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 82, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S. Binary Particle Swarm Optimization with Manta Ray Foraging Learning Strategies for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanrasu, S.S.; Janani, K.; Rakkiyappan, R. A COPRAS-based approach to multi-label feature selection for text classification. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 222, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Huang, X.; Qian, Y.; Ding, W. A fuzzy C-means clustering-based hybrid multivariate time series prediction framework with feature selection. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 32, 4270–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jadir, I.; Wong, K.W.; Fung, C.C.; Xie, H. Unsupervised text feature selection using memetic dichotomous differential evolution. Algorithms 2020, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkalioglu, M. A novel redistribution-based feature selection for text classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 246, 123119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Almotairi, K.H.; Al-qaness, M.A.; Ewees, A.A.; Yousri, D.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H. Efficient text document clustering approach using multi-search Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 248, 108833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrino, D.; De Prisco, R.; Ianulardo, M.; Zaccagnino, R. An adaptive meta-heuristic for music plagiarism detection based on text similarity and clustering. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2022, 36, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, A.K.; Khader, A.T.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Alyasseri, Z.A.A.; Makhadmeh, S.N.; Al-laham, M.; Naim, S. A hybrid salp swarm algorithm with β-hill climbing algorithm for text documents clustering. In Evolutionary Data Clustering: Algorithms and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 129–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Fei, M.; Zhou, W.; Du, S.; Fei, Z.; Zhou, H. Binary Banyan tree growth optimization: A practical approach to high-dimensional feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 315, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Z.Y.; Abdullah, A.A.; Rashid, T.A. Optimizing feature selection with genetic algorithms: A review of methods and applications. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 9739–9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, L.; Jiao, L. A two-stage hybrid ant colony optimization for high-dimensional feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 116, 107933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Guan, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, B. Multi-population differential evolution approach for feature selection with mutual information ranking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 260, 125404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Ma, L.; Chen, H. A hybrid rice optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Nagoya, Japan, 23–25 August 2016; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, C.; Guo, Y. A Surrogate-Assisted Multi-Phase Ensemble Feature Selection Algorithm with Particle Swarm Optimization in Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 3833–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; He, J.; Wang, Y. A Feature Selection Method for Software Defect Prediction Based on Improved Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 4879–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msallam, M.M.; Bin Idris, S.A. Unsupervised text feature selection by binary fire hawk optimizer for text clustering. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 7721–7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachaoui, M.; Lakouam, I.; Hafidi, I. Hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm for text feature selection problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 7471–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, L.; Shen, J. A cooperative hybrid breeding swarm intelligence algorithm for feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 169, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zong, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, M. A modified hybrid rice optimization algorithm for solving 0-1 knapsack problem. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 5751–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wang, M.; He, Q.; Chen, Z.; Bai, W. Cooperative metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization and engineering problems inspired by heterosis theory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.S. Optimizing Kernel Extreme Learning Machine based on a Enhanced Adaptive Whale Optimization Algorithm for classification task. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, E0309741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Da, W.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Wei, J. Research on a drilling rate of penetration prediction model based on the improved chaos whale optimization and back propagation algorithm. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 240, 213017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touabi, C.; Ouadi, A.; Bentarzi, H.; Recioui, A. Photovoltaic Panel Parameter Estimation Enhancement Using a Modified Quasi-Opposition-Based Killer Whale Optimization Technique. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braik, M. Hybrid enhanced whale optimization algorithm for contrast and detail enhancement of color images. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 231–267. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z. Prediction of end-point temperature and carbon content in electric arc furnace steelmaking based on a whale optimization algorithm with lévy flight and stochastic configuration network algorithm. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Wu, Y. State of Health Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Enhanced Whale Optimization Algorithm for Feature Selection and Support Vector Regression Model. Processes 2025, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Wu, Y.; Yan, G.; Si, X. A memory interaction quadratic interpolation whale optimization algorithm based on reverse information correction for high-dimensional feature selection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 111979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareb, A.S.; Bakar, A.A.; Hamdan, A.R. Hybrid feature selection based on enhanced genetic algorithm for text categorization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 49, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.R.; Bakar, A.A.; Yaakub, M.R. Ant colony optimization for text feature selection in sentiment analysis. Intell. Data Anal. 2019, 23, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Mani, A.; Bansal, R. Feature selection for text and image data using differential evolution with SVM and naïve Bayes classifiers. Eng. J. 2020, 24, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.Z.; Xu, G.; Du, J.; Zhu, H.; Yan, T.; Yu, Y.F. Flexible subspace clustering: A joint feature selection and k-means clustering framework. Big Data Res. 2021, 23, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Song, P.; Zhou, S.; Mu, J.; Liu, Z. Consensus and discriminative non-negative matrix factorization for multi-view unsupervised feature selection. Digit. Signal Process. 2024, 154, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.L.; Song, Y.W.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, S.; Jin, S.Y.; Xu, Z.R. Stochastic fractal equilibrium optimizer with X-shaped dynamic transfer function for solving large-scale feature selection problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 318, 113567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.L.; Song, Y.W.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Song, H.M.; Shang-Guan, Y.P. EQUILIBRIUM optimizer with integrated M-shaped transfer function family for solving feature selection problems. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, G. Vector Space Model. In Syntactic n-Grams in Computational Linguistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Seyyedabbasi, A.; Hu, G.; Shehadeh, H.A.; Wang, X.; Canatalay, P.J. V-shaped and S-shaped binary artificial protozoa optimizer (APO) algorithm for wrapper feature selection on biological data. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.S.; Hou, J.N.; Song, H.M.; Li, X.D.; Guo, F.J. RG-NBEO: A ReliefF guided novel binary equilibrium optimizer with opposition-based S-shaped and V-shaped transfer functions for feature selection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 6509–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Mallipeddi, R.; Lee, D.G. High-density cluster core-based k-means clustering with an unknown number of clusters. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 155, 111419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Seraj, R.; Islam, S.M.S. The k-means algorithm: A comprehensive survey and performance evaluation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Mirjalili, S. Superb Fairy-wren Optimization Algorithm: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for solving feature selection problems. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q. A novel hybrid improved RIME algorithm for global optimization problems. Biomimetics 2024, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakye, B.D.; Li, Y.; Mohamed, H.H.; Baidoo, E.; Asenso, T.Q. Particle guided metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization and feature selection problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 248, 123362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Zare, M.; Trojovský, P.; Rao, R.V.; Trojovská, E.; Kandasamy, V. Optimization based on the smart behavior of plants with its engineering applications: Ivy algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 295, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.; Malik, F.; Khan, Q.W.; Ahmad, N.; Sardaraz, M.; Karim, F.K.; Elmannai, H. A Hybrid K-Means++ and Particle Swarm Optimization Approach for Enhanced Document Clustering. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 48818–48840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.M.; Khader, A.T.; Al-Betar, M.A. Unsupervised feature selection technique based on genetic algorithm for improving the text clustering. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CSIT), Amman, Jordan, 13–14 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. K-Means text clustering method based on Decision Grey Wolf Optimization. In ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Labani, M.; Moradi, P.; Jalili, M. A multi-objective genetic algorithm for text feature selection using the relative discriminative criterion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 149, 113276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupapara, V.; Rustam, F.; Ishaq, A.; Lee, E.; Ashraf, I. Chi-Square and PCA Based Feature Selection for Diabetes Detection with Ensemble Classifier. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 36, 1931–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuya, E.O.; Okeyo, G.O.; Kimwele, M.W. Feature selection for classification using principal component analysis and information gain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 174, 114765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.