1. Introduction

The emergence of increasingly sophisticated networking threats requires the development of more advanced tools. Prominent networking attacks include distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks such as network flooding [

1] (TCP, UDP, and ICMP), smurf attack [

2], and ping-of-death [

3]. Cyber-security researchers often unleash such attacks in controlled or simulated environments when developing detection and mitigation techniques using tools such as Hping3 [

4] and Ostinato [

5]. Due to their lack of scripting capabilities, libraries such as libtins [

6] and Scapy [

7] are often used instead to implement complex network attacks. However, even with a comprehensive knowledge of essential elements of an attack, the process of developing new or modifications of existing network attacks can be time-consuming.

To rectify these deficiencies, researchers have developed approaches that leverage pre-trained transformer models, specifically large language models (LLMs), to simulate complex network environments. Examples of these approaches include PAC-GPT [

8], NetGPT [

9], TrafficFormer [

10], and TrafficGPT [

11]. Although these approaches have demonstrated encouraging results, they often incur a high computational cost and complexity, and lack the flexibility required to adapt to novel attack patterns in specific network environments and protocols. All of these approaches aim to generate synthetic network traffic directly hoping to capture the intricacies of (potentially) malicious traffic effectively.

To tackle these challenges and limitations, we propose AgentRed, a novel AI agent-based framework for network traffic generation that can produce intermediate network traffic representations corresponding to various traffic patterns, including those associated with attacks. Tools like Scapy can consume these portable representations to produce immediate attack behavior, including the sending of packets, without requiring human-written code. In other words, we adopt a different approach i.e., our proposed framework aims to create accurate programs/scripts fast that deploy new or modified versions of attacks rather than generate synthetic traffic. Our method integrates the strengths of reinforcement learning [

12], specifically Group Relative Proximal Policy Optimization (GRPO) [

13], with the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

14] parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) technique during an agent-triggered fine-tuning. This combination enables us to adapt lightweight pre-trained LLMs, such as Qwen3 0.6B [

15], to specific network traffic patterns and environments while maintaining computational efficiency and flexibility. By enabling the framework to dynamically select and fine-tune various adapters based on traffic generation requirements, we create a system that can generate diverse and realistic network traffic patterns without manual implementation of such behavior. This adaptability is crucial for simulating various network scenarios, including benign and malicious traffic types and novel attack patterns.

Our contributions are as follows:

We introduce AgentRed, an AI agent networking tool. Unlike static pre-trained models (e.g., NetGPT) that are limited to their training cutoff, we introduce an autonomous agent workflow capable of creating lightweight LoRA adapers and retrieving real-time context via online search to generate traffic for various attack patterns without model retraining. This framework enables a deterministic network packet generator (Scapy) to be utilized as the verifier, enabling the fine-tuned model to learn strict protocol constraints without human supervision.

We design a novel portable traffic generation format that can be easily parsed to create network packets. This effectively alleviates the need to manually implement attacks in code, for example, using Scapy scripts. This novel intermediate XML traffic representation bridges the gap between probabilistic LLM generation and deterministic packet construction.

We evaluate the performance of our approach considering six popular network attacks to assess its ability to generate network packets with high accuracy and low latency.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews some recent related work in network traffic generation. We provide some technical background in

Section 3. In

Section 4, we detail our proposed methodology, including the proposed framework.

Section 5 presents the experimental setup, datasets, results, and analysis. Finally, we conclude the paper in

Section 7, summarizing our main findings.

2. Related Work

Several recent works have explored the application of pre-trained transformer models to the understanding and generation of network traffic as shown in

Table 1. Before the advent of large language models, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) represented the state-of-the-art in synthetic traffic generation. Anande and Leeson provide a comprehensive survey of this domain, categorizing various GAN architectures such as

PAC-GAN for packet-level generation and

ITCGAN for addressing class imbalance in traffic datasets [

16]. Their analysis highlights the evolution from simple flow-level statistical replication to complex packet-byte generation using adversarial training. However, they also identify key limitations in these architectures, specifically the difficulty in converging on multi-serial network packets for diverse protocols, a challenge our agent-based transformer approach aims to resolve.

Beyond adversarial networks, researchers have recently applied diffusion models to the domain of traffic synthesis. Jiang et al. proposed NetDiffusion, a framework that fine-tunes text-to-image latent diffusion models to generate high-fidelity network traffic [

17]. Their approach transforms traffic flows into image-based representations using the nPrint encoding and utilizes ControlNet to enforce protocol constraints and field-level consistency. While NetDiffusion demonstrates superior statistical similarity and utility for data augmentation compared to GAN-based baselines, it relies on converting binary network data into visual representations for processing. In contrast, our work with AgentRed treats network traffic generation as a language modeling task, leveraging the inherent sequential reasoning capabilities of LLMs to generate complex attack vectors without intermediate modality conversions.

In the realm of transformer-based architectures, several works have explored pre-training models for traffic understanding. The authors in TrafficFormer [

10] propose a two-stage pre-training approach. This approach, designed explicitly for traffic data, employs Masked Burst Modeling (MBM) and Same Origin-Direction-Flow (SODF). It is followed by supervised fine-tuning with Random Initialization Field Augmentation (RIFA). The evaluation of TrafficFormer shows superior protocol understanding capabilities. Although achieving nearly 100% F1 scores in packet direction judgment tasks, it mainly focuses on traffic classification rather than generation.

To enable generation capabilities within transformers, researchers designed a large-scale pre-training method, in NetGPT [

9], for generating and understanding network traffic. Existing encoding schemes used in LLM architectures are often unsuitable for network traffic data. Thus, the authors encode the network packets in hex and apply WordPiece tokenization, which can better handle the diverse byte patterns in network data. During fine-tuning, the researchers propose header field shuffling as an augmentation strategy to increase data diversity. With these changes, the traffic generation performance shows some improvements over baseline GPT-2 models. However, the results indicate a marginal average Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) score of 0.0406 across the packet length, source port, and destination port fields.

To address the token length limitations of previous approaches, the authors in [

11] propose TrafficGPT. To increase the generation throughput and handle large traffic flows, they extend the maximum token capacity from 512 to 12,032 tokens. Since traditional attention layers are quadratic in the input length, the authors choose to use linear attention mechanisms instead. Also, they design a novel tokenization strategy that incorporates packet start tokens, link type tokens, and time interval tokens. These changes provide a more comprehensive representation of traffic flow. Although their model shows a 2% improvement in classification tasks and a packet-level JSD score of 0.1605 for traffic generation, it requires 189 GB of traffic data for pre-training.

Most recently, Delgado-Soto et al. introduced a framework utilizing OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 Turbo to generate realistic multi-protocol network conversations [

18]. Their approach implements a Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture combined with prompt engineering to specialize the model in generating stateful traffic for specific protocols, including ICMP, ARP, DNS, TCP, and HTTP. Similar to our work, their system produces executable Scapy commands to construct the final network packets. However, their architecture relies on accessing large, API-based models and standard fine-tuning or few-shot prompting techniques. In contrast, AgentRed focuses on the parameter-efficient adaptation (LoRA) of lightweight, locally hostable models (e.g., Qwen3 0.6B) and integrates an autonomous agent capable of retrieving emerging attack contexts dynamically.

Despite these significant advancements, some drawbacks of existing methods include high computational costs, complex tokenization processes, limited adaptability to specific traffic types, and dependency on large datasets. These challenges hinder their practical application and ease of use.

3. Technical Overview

This section provides an overview of the key concepts discussed in our approach.

3.1. Network Traffic Generation Tools

Computer networking tools are often crucial in network cybersecurity research. They aid in the simulation of various network conditions and behaviors. These tools are typically used for testing and evaluation purposes. They often rely on static networking components, are rule-based systems, or use statistical models. Consequently, these tools may not accurately capture the complexity and diversity of real-world traffic patterns. For instance, tools such as aircrack-ng [

19], Hping3 are specifically designed to craft a specific kind of packets and network traffic. While frameworks like Metasploit [

20] contains various modules like aircrack-ng [

19] and mdk3 [

21] that can simulate different types of network traffic and attacks; they primarily rely on predefined templates and user-defined parameters. Other tools, such as Scapy [

7] and libtins [

6], enable the creation and manipulation of network packets. In a nutshell, all these tools require manual and time-consuming configuration and scripting, which can be a barrier for non-expert networking users. Conversely, the recent advancements in machine learning, specifically in LLMs, have enabled the development of more advanced tools. These tools typically utilize LLMs capable of autonomously generating more realistic and contextually relevant network traffic. These models can learn intricate patterns from vast datasets, which makes them well-suited for generating structured data, such as network packets.

3.2. PPO, GRPO, and LoRA

Reinforcement learning (RL) [

22] is a paradigm in machine learning, where an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. The agent receives the state of the environment and feedback in the form of rewards for each action taken. RL has recently shown remarkable results in fine-tuning LLMs for specific tasks. Specifically, RL algorithms can be utilized to optimize a model’s performance based on task-specific objectives. This is made possible by carefully selecting the reward mechanism, which can include a reward model [

23] (typically an LLM), a verifiable reward [

13] (a user-defined algorithm), or some form of internal reward. For instance, PPO [

23] is a widely used policy gradient algorithm designed to improve training stability. It constrains policy updates by clipping the probability ratio between the new policy

and the old policy

. The objective function is

where

is the probability ratio between the new and old policies,

is the advantage estimate, and

is a hyperparameter controlling the trust region. GRPO extends PPO with the introduction of a group-relative baseline and KL regularization. These improvements stabilize training in environments with sparse or noisy rewards. The GRPO objective is defined as

Here, the group-normalized advantage is computed as

Here, G denotes the group size, is the reward of the i-th sample in the group, is a reference policy (e.g., the original model), and controls the strength of the KL penalty. This relative formulation encourages the policy to prefer outputs that outperform the group baseline, thereby aiding in maintaining proximity to the reference policy.

LoRA [

14] is a Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) [

24] method that reduces the number of trainable parameters by injecting trainable low-rank matrices into each layer of a pre-trained model. It avoid updating the full weight matrix

, but instead LoRA freezes

and learns two low-rank matrices

and

:

Here is the low rank. These improvements significantly reduce the fine-tuning cost while maintaining model performance.

GRPO combined with LoRA provides an efficient and stable framework for fine-tuning LLMs on complex reasoning tasks, such as network traffic generation, where the model must learn to produce structured outputs that meet protocol specifications and satisfy verifiable reward criteria.

4. Methodology

In this work, we propose

AgentRed, a novel approach to generating synthetic network traffic using an LLM agent. Our approach, illustrated in

Figure 1, leverages an agentic fine-tuning (steps 2–4) and inference (steps 5–6) framework that unites the strengths of reinforcement learning, specifically GRPO, with the LoRA parameter-efficient fine-tuning technique. (see Algorithm 1).

To address the limitations of existing LLM-based traffic generators, AgentRed introduces a conceptual shift from Model-Centric to Agent-Centric generation. Previous approaches such as NetGPT [

9] and TrafficGPT [

11] rely on the “knowledge-in-weights” paradigm, where the model must memorize every protocol and byte pattern during massive pre-training. This results in static models that are computationally expensive and prone to structural hallucinations (e.g., incorrect checksums).

In contrast, AgentRed decouples intent from implementation. The agent handles high-level reasoning and dynamic context retrieval (e.g., searching for specific packet structures via online search), overcoming the static knowledge cutoff of traditional LLMs. Simultaneously, the LoRA Adapters provide lightweight, task-specific conditioning rather than broad general knowledge, drastically reducing computational overhead. Finally, the XML-like traffic representation format acts as a semantic bridge, allowing the LLM to generate logic (e.g., “set TCP flag to SYN”) while offloading the rigorous byte-level construction to a deterministic engine (Scapy).

A critical methodological innovation of our approach is the verifier-guided training methodology, detailed in

Figure 2. Unlike standard Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which typically treats the reward model as a black box, we integrate a deterministic tool-in-the-loop verifier. This mechanism, embedded within the reward computation of GRPO, executes the generated Scapy code in a sandboxed environment during the training loop (see Algorithms 1 and 2). First, the model generated text is parse to validate that it conforms to the correct format, as specified in

Figure A1 and

Figure A2. Invalid format are penalized while correct format are rewarded. Second, the packet generation code is extracted from the model’s output to reward valid code and penalize syntax errors. Finally, the list of packets are traversed to check that the fields match the expected fields to reward valid packet structures and penalized invalid packets. By applying immediate penalties for parsing failures, the system enforces strict protocol syntax without requiring human intervention, ensuring the model converges to generating executable network traffic rather than hallucinated text.

4.1. Workflow Overview

A workflow of our proposed tool, as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, has the following steps: (1) user prompt input, (2) traffic pattern identification, (3) adapter selection, (4) adapter creation with GRPO and LoRA, (5) agent online search, and (6) packet generation.

- ①:

User Prompt and PCAP Files. The workflow begins with the user providing a set of initial PCAP files and a prompt that specifies the desired characteristics of the network traffic to be generated. The PCAP files are used to bootstrap the creation of LoRA adapters, while the prompt is a natural language description of the traffic generation task. The prompt may include details such as the target protocols, traffic patterns, and any specific requirements.

- ②:

Traffic Pattern Identification. The AI agent analyzes the user prompt to identify the specific network traffic to generate. This step involves parsing the input to extract relevant information about protocols, packet structures, and traffic behaviors, and searching online for relevant information (see

Figure A1 for an example of agent output). Finally, the agent determines whether an existing adapter can be used or if a new one needs to be created.

- ③:

Adapter Selection. Based on the identified traffic pattern, the agent may consult its memory to check for existing adapters that match the requirements. A suitable adapter is one that has been fine-tuned on similar traffic patterns or protocols as specified in the user prompt. If a suitable adapter is found, its weights are merged into the base LLM for immediate use. Otherwise, the process continues with the creation of a new LoRA adapter.

- ④:

Adapter Creation with GRPO and LoRA. If no existing adapter is suitable, the agent initiates the creation of a new adapter, as shown in

Figure 2. This involves fine-tuning a base LLM (e.g., Qwen3 0.6B) using GRPO and LoRA techniques (see Equations (

2) and (

4)). The fine-tuning process is guided by a verifiable reward function that evaluates the quality of the generated network traffic based on Algorithm 1 and Equation (

3). The adapter(s) are trained on the provided initial PCAPs. The PCAPs may correspond to normal traffic that contains packets of the desired protocol/application, or they may contain packets with examples of the desired network attack.

- ⑤:

Agent Online Search. Once the adapter(s) are selected, the agent may perform an online search to gather additional context, for example, information relevant to a specific attack, the protocols involved, packet header fields, etc. This step ensures that the agent includes the latest information in the prompt to send to the adapter(s), enabling adaptation to emerging patterns or threats, such as new attack vectors or zero-day exploits.

- ⑥:

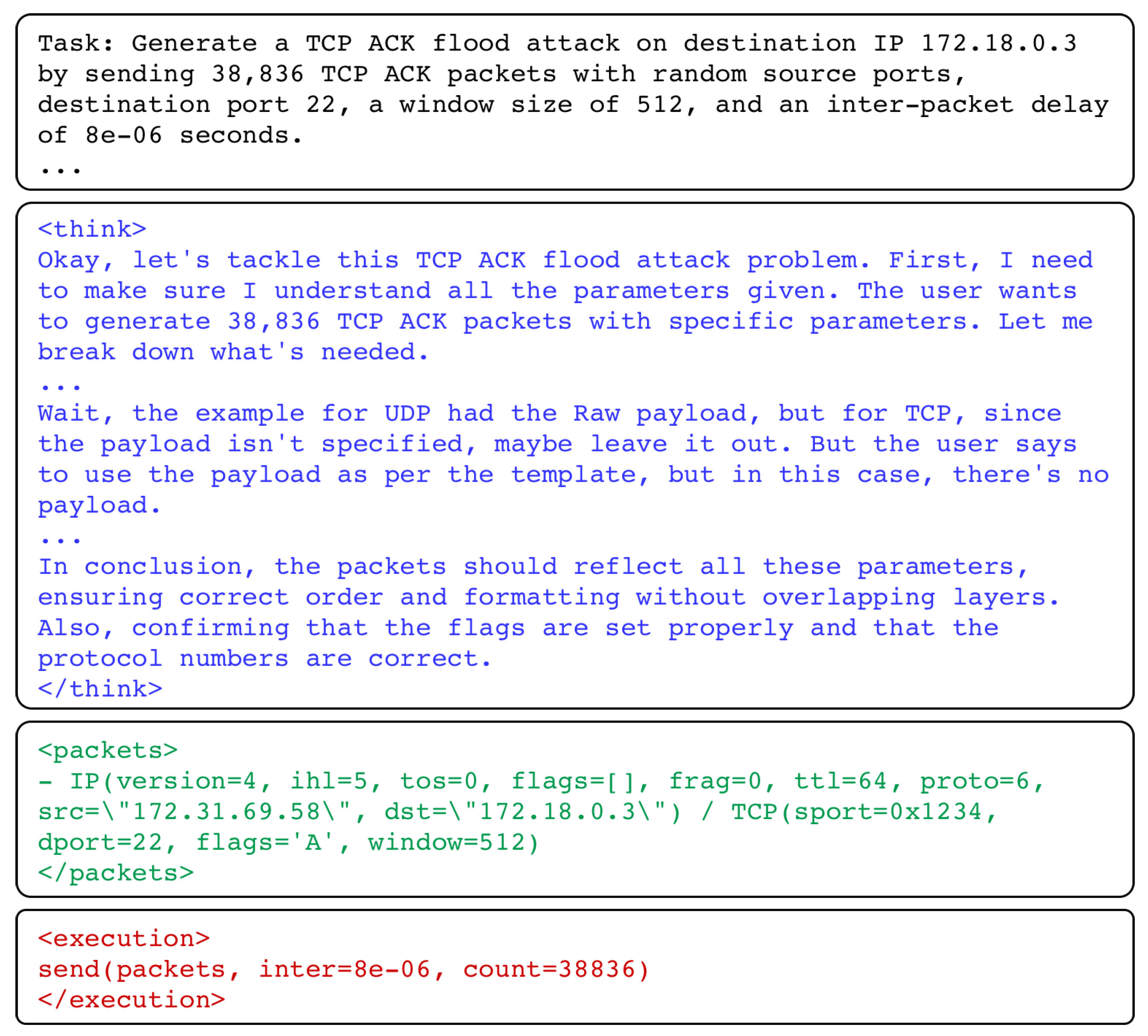

Packets Generation. Finally, the agent merges the weights of the adapter(s) into the base LLM model and then uses it for traffic generation. The adapter(s) may output an intermediate packet creation format structured with XML-like tags. This format includes the model thinking process in a thinking tag, the packet(s) creation details in a packets tag, and the Scapy execution script in a execution tag. Additionally, the agent may incorporate information obtained from the online search to further refine the generated intermediate format. Finally, the LLM output is parsed using Scapy to generate packets, which are stored in a PCAP file.

| Algorithm 1 GRPO Fine-Tuning for Network Traffic Generation |

Require: Pre-trained LLM , Dataset , Group size G Ensure: Fine-tuned Policy 1: initialize 2: for each training step do 3: Sample batch of prompts from 4: for each prompt do 5: Generate G outputs from 6: for each output do 7: ▹ See Algorithm 2 8: end for 9: Compute advantage using normalized rewards over group G 10: end for 11: Update via GRPO objective: 12: end for

|

| Algorithm 2 ComputeReward: Packet Reward Calculation |

Require: Generated Output o, Ground Truth Packet y Ensure: Scalar Reward R 1: 2: if o does not match XML regex <think>...<packets>... then return 3: ▹ Penalty for format violation 4: end if 5: Extract packet string s from o 6: if s fails eval(s) then return ▹ Penalty for malformed packet syntax 7: end if 8: 9: Parse generated packet 10: Parse ground truth 11: if fields match fields then 12: 13: else 14: 15: end if 16: ▹ Normalize reward between 0 and 1 return R

|

4.2. Fine-Tuning LoRA Adapters

We create and evaluate multiple adapters for various traffic patterns observed in normal ICMP Ping and in different flooding attack patterns, including TCP-SYN, UDP, TCP-ACK, and ICMP floods. Each adapter is fine-tuned using GRPO to optimize the model’s performance in generating realistic and diverse network traffic. The fine-tuning process is detailed in Algorithm 1. Moreover, we use a novel verifiable reward function and instruct the model to follow a structured output format. This format includes the model’s thought process in a thinking tag, a packets tag that contains representative packets for the specific traffic pattern, and a execution tag that contains the necessary parameters to generate the packets with Scapy (see

Figure A2 for an example of LLM response). This structured approach enables easy verification of the traffic generation output.

Our reward function, defined in Algorithm 2, captures the quality of the traffic generation output based on the following deterministic criteria. First, we measure the model’s ability to conform to the required XML-like structure. A failure to do so results in an immediate format penalty . Second, we evaluate the semantic validity of the code by attempting to evaluate code with Scapy. A malformed syntax that leads to execution errors is penalized (). Finally, we assess field-level accuracy by comparing the successfully parsed packets against the ground truth. If fields do not match, a logic penalty is applied (). This hierarchical design ensures stability by providing dense supervision forcing the model to first learn the format and syntax, before it can optimize for field accuracy.

5. Experiments

In this section, we describe the experimental setup used to evaluate our proposed agentic network tool.

5.1. Datasets

We created a simulated container-based test environment in our experiments. We set up two Docker containers, where one acts as an attacker and the other as the victim. The attacker container launches various network attacks, including UDP flood, TCP-SYN flood, TCP-ACK flood, ICMP flood, Ping-of-Death (PoD), ICMP Ping, and Smurf attack, against the victim container using Hping3 for simple attacks and Scapy for more complex attacks. The traffic from the attacker to the victim is captured using tcpdump [

25] and stored in a PCAP file. Each PCAP file contains between 20 (e.g., normal ICMP Ping) and 10,000 packets, with each file having a size of less than 5 MB. The discrepancy in the number of packets per PCAP file is due to the nature of the attack. For example, flooding attacks generate a large number of packets in a short period, while Ping-of-Death and Smurf attacks involve fewer packets with specific characteristics. For each traffic type, we captured 500 PCAP files, resulting in a total of 3500 PCAP files. The dataset was split into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets to ensure robust evaluation.

While this approach can generate a synthetic dataset, we opted for this controlled generation methodology to ensure the availability of high-fidelity code-level labels. Unlike real-world network traces which lack the generating source code, this pipeline provides the exact Scapy scripts required to train the model on valid API usage and protocol syntax. We maintain that for the specific task of learning protocol grammar, this synthetic data is functionally representative of real-world standards, as a packet’s validity is defined by its adherence to deterministic RFC specifications rather than environmental stochasticity.

5.2. Experimental Setup

Our experimental setup involved fine-tuning the Qwen3 0.6B model on the dataset we created. To ensure sufficient computational power for the fine-tuning process, we performed all the experiments (training and evaluation) on a machine equipped with two 2 NVIDIA A6000 GPUs.

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluated our approach using the following key metrics: traffic generation execution time, packet-level accuracy, statistical similarity measures, and field-level precision analysis. Each metric captures distinct aspects of generation quality critical for practical deployment in network security applications. We use the standard classification metrics, including accuracy, f1-score, precision, and recall.

5.3.1. Classification Metrics

We evaluate the fundamental ability of our models to generate correct packet structures using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. These metrics use the true positives (TPs) and false positives (FPs) in their calculations. The former (TP) represents correctly generated packet fields that match the target traffic type, while the latter (FP) represents those with incorrectly generated fields. These metrics are computed at both the packet level (overall structure) and field level (individual protocol fields). This enables a granular assessment of generation quality.

5.3.2. Statistical Distribution Similarity

We use the Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) as a score to assess whether the generated traffic exhibits realistic statistical properties. This aids in quantifying the similarity between the generated and original traffic distributions. We compute the JSD across the most critical packet attributes, including ports and IP addresses.

In this formula is the average distribution. represents Kullback-Leibler divergence. The JSD score provides a symmetric, bounded measure of distributional difference in the range of , with lower values indicating better statistical fidelity.

5.3.3. Field-Level Accuracy Analysis

We implement field-level accuracy scoring to assess generation quality at the granular level. Typical network packets are comprised of multiple protocol fields, each requiring precise values for successful transmission and processing.

Here is the indicator function, and N represents the total number of packets. We evaluate 16 critical header fields, including: IP fields (version, ihl, tos, flags, frag, ttl, proto, src, and dst), TCP fields (sport, dport, flags, and window), UDP fields (sport and dport), and ICMP fields (type and code).

5.4. Experimental Results

We evaluated our tool across three inference modes: (a) base mode, (b) adapter mode, and (c) agent mode. In the first experiment, we evaluate the performance of the base model using the Qwen3 0.6B model with a custom system prompt that instructs the model to generate network traffic in the specified intermediate format without any fine-tuning. The second experiment involves assessing the performance of the LoRA adapters created using GRPO fine-tuning by the AI Agents. Finally, in the third experiment, we evaluate the performance of the AI agent that utilizes online searches to enrich the context of the LoRA adapters during traffic generation. Our evaluation used seven distinct network attack patterns. The experiments assessed packet generation accuracy, field-level precision, execution efficiency, and statistical similarity to original traffic patterns. The results of our experiments are summarized in

Table 2.

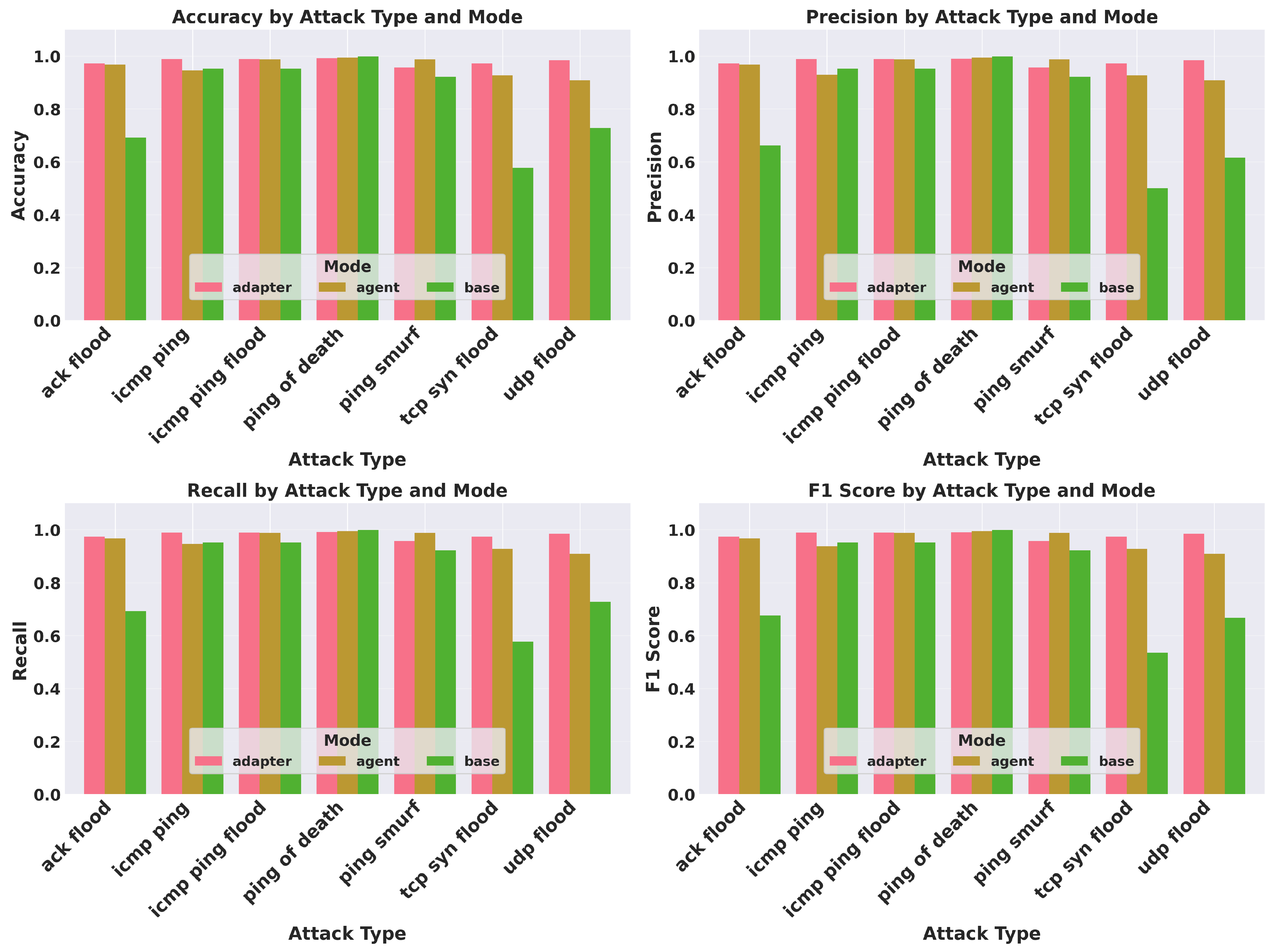

Table 3 and

Figure 3 present a performance comparison across the different inference modes. We further break down the performance evaluation by attack type to highlight the adaptability of our approach to diverse traffic patterns (see

Table 4 and

Figure 4).

5.4.1. Experiment 1: Evaluation of the base Mode

We evaluate the performance of the base LLM model (Qwen3 0.6B) without any fine-tuning on the intermediate traffic generation format. The goal is to assess the model’s inherent ability to generate network traffic patterns based solely on its pre-trained knowledge and the provided system prompt. The results indicate that the base model achieves an overall cumulative accuracy of 95.4% (±0.066), with a precision of 0.953, recall of 0.954, and F1-score of 0.954 across all traffic patterns. However, for attacks involving Ack Flood, TCP-SYN Flood, and UDP Flood, the accuracy drops significantly to 69.2%, 57.7%, and 72.7%, respectively. This demonstrates the limitations of the base model in capturing complex traffic patterns without fine-tuning. This also suggests that the base model may struggle to generalize to specific attack patterns that were not well-represented in its pre-training data.

5.4.2. Experiment 2: Evaluation of the adapter Mode

In this experiment, we assess the performance of the adapter mode, where LoRA adapters fine-tuned using GRPO are employed for traffic generation. The objective is to evaluate how effectively the fine-tuned adapters can enhance the model’s ability to generate accurate network traffic patterns corresponding to various types of attacks. The adapter mode demonstrates exceptional efficacy across all evaluated metrics. The overall cumulative accuracy reaches 97.9% (±0.043), with a precision of 0.980, recall of 0.979, and F1-score of 0.978. Notably, the adapter mode sustains superior accuracy across all attack types, including those that posed challenges for the base model. For instance, the accuracy for Ack Flood, TCP-SYN Flood, and UDP Flood attacks improves significantly to 97.2%, 97.3%, and 98.4%, respectively. This underscores the effectiveness of the adapter-based approach in capturing attack-specific characteristics through targeted fine-tuning. Furthermore, the adapter mode completed packet generation in an average of 20.8 s, representing a 37.5% improvement over the base mode (32.3 s).

5.4.3. Experiment 3: Evaluation of the agent Mode

We tested the performance of the agent mode, where an AI agent searches online to enrich the context of LoRA adapters for traffic generation. The aim is to evaluate how the agent’s ability to gather additional information impacts the quality of generated network traffic patterns. The agent mode achieves an overall cumulative accuracy of 96.0% (±0.071), with a precision of 0.961, recall of 0.960, and F1-score of 0.959. While the agent mode does not outperform the adapter mode in terms of raw accuracy, it still demonstrates significant improvements over the base model, particularly for complex attack patterns. For example, the accuracy for Ack Flood, TCP-SYN Flood, and UDP Flood attacks improves to 96.7%, 92.7%, and 90.8%, respectively. This indicates that the agent’s ability to gather additional context through online searches enhances its capacity to generate accurate traffic patterns, even when faced with novel or complex scenarios.

5.4.4. Attack-Specific Performance

We assess the performance of our framework across different attack types (see

Table 4 and

Figure 3). The Ping of Death attacks, for example, achieved the highest accuracy (99.5% ± 0.031), followed by ICMP Ping Flood (97.6% ± 0.049). More complex attacks, such as the UDP Flood, exhibited lower but still robust performance (92.5% ± 0.070), potentially due to the greater variability in legitimate UDP traffic patterns. Notably, the adapter mode maintained consistent high performance across all attack types (ranging from 97.2 to 99.1% accuracy), while the base mode showed significant degradation for certain attacks. In particular, the base mode performed poorly on ACK Flood (69.2%), TCP-SYN Flood (57.7%), and UDP Flood (72.7%). This underscores the adapter’s ability to capture attack-specific characteristics through targeted fine-tuning.

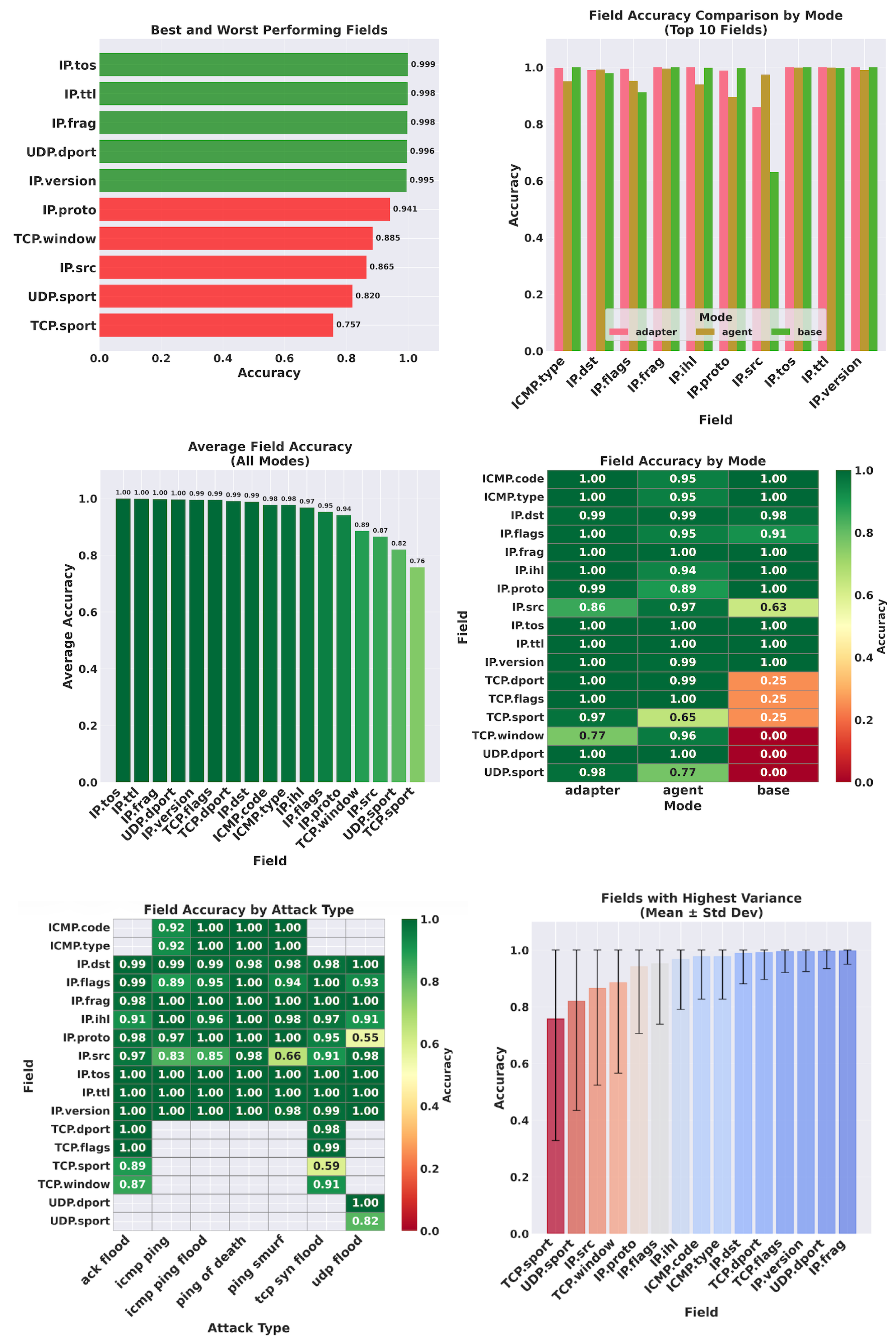

5.4.5. Field-Level Accuracy Analysis

We further assess the performance of our tools at the header field level (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The experimental results reveal near-perfect performance for critical protocol fields. To rigorously validate these findings, we conducted a statistical error analysis, as detailed in

Table 5, which reports the mean accuracy, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals for key fields. Our tools demonstrated high accuracy on header fields, including IP (IP.flags, IP.src, IP.dst) and ICMP header fields, achieving 95–100% accuracy across all modes with tight confidence intervals (±0.001–0.007). TCP and UDP port fields demonstrated the superiority of our adapter-based approach on the base model, with the adapter achieving 99% accuracy while the base model dropped to 25.0% for TCP and 0.0% for UDP. The agent mode demonstrated similar results to the adapter-based approach (94–100%), with the performance dropping to 89%, 77%, 65%, respectively, for the IP protocol field, TCP source port, and UDP source port. This further confirms the superiority of the agent-based approach in capturing complex field relationships, particularly when traffic patterns may not have been observed during the training of the base model. Although we observed some minor degradation in complex fields, such as TCP flags, in certain attack scenarios, the adapter mode maintains consistent high accuracy across all fields and attack types, as shown in

Figure 5.