Abstract

Among the recently developed ferroelectric nematic liquid crystals, FNLC-919, synthesized by Merck Electronics KGaA, stands out for its stable, room-temperature, ferroelectric nematic (NF) phase. This renders it a promising candidate for both fundamental research and device-level applications. In this study, we present a comprehensive experimental investigation of FNLC-919, focusing on its structural, optical, dielectric, and elastic properties in the paraelectric nematic (N) and the intermediate antiferroelectric phase (dubbed NX) that occur in a temperature range between the N and NF phases. Key material parameters such as ferroelectric polarization, viscosity, and nanostructure are characterized as functions of temperature in all mesophases, while the orientational elastic constants are determined only in the N and NX phases. Our findings are compared with prior results concerning the benchmark compound DIO that also exhibits the phase sequence N-NX-NF and reveals a smectic-like mass density wave coinciding with antiferroelectric ordering in the NX phase.

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of liquid crystals in 1888 by Friedrich Reinitzer [1], numerous exotic nematic phases such as the chiral, biaxial, bent-core, and twist–bend nematic phase of liquid crystals have been theoretically predicted and experimentally realized, expanding the horizon of soft matter physics [2,3,4]. The traditional nematic phase of liquid crystals is characterized by a long-range orientational order but no positional order or macroscopic polarization. While most compounds that exhibit the nematic phase have non-zero molecular dipole moments, the bulk material remains non-polar because the director ( exhibits head-to-tail equivalency [5].

In 2017, two materials were independently reported [6,7] to exhibit the polar nematic phase. Shortly thereafter, these materials were confirmed to possess switchable spontaneous [8,9] polarization, i.e., ferroelectricity [10]; this phase is denoted as the ferroelectric nematic (NF) phase. The polar nature of this phase allows for linear electro-optic coupling at fields as low 1 V/mm [10]. The discovery of the long-sought-after NF phase has catalyzed a significant increase in the synthesis [11,12,13,14] and analysis [15,16,17,18,19] of new FNLCs. Furthermore, the NF phase exhibits electrohydrodynamic instability [20,21,22], thermomechanical coupling [23], and filament formation [8,9]. NF materials also show remarkable linear electromechanical responses [24,25,26], large second harmonic generation signals [12,27,28], second-order non-linear optical (NLO) coefficients [29,30], exotic entangled photon-pair generation [31], and bulk photovoltaic effects [32] that hold promise for new technological applications. Many technological applications will become far more accessible with access to stable materials exhibiting the NF phase at ambient temperatures.

In this work, we report comprehensive physical property measurements on one such candidate material, the mixture FNLC-919, prepared and provided by Merck Electronics, KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Its phase sequence on cooling was reported as I-80 °C-N-44 °C–NX-32 °C-NF-8 °C–Cr, where NX is the tentative identifier for the phase that is intermediate between N and NF. Although FNLC-919 has been studied by various groups describing their alignment properties and birefringence [33], its ability to form free-standing filaments [8] and its use in electrically tunable lenses and reflectors [34,35,36], a complete characterization of its physical properties and the identification of the nature of its phase between the N and NF phases, are lacking. To fill this gap, we present a detailed experimental investigation of FNLC-919, encompassing complete phase identification, polarization and dielectric constant measurements, orientational elastic constants and viscosity measurements, and results from small-angle X-ray scattering.

2. Methods and Results

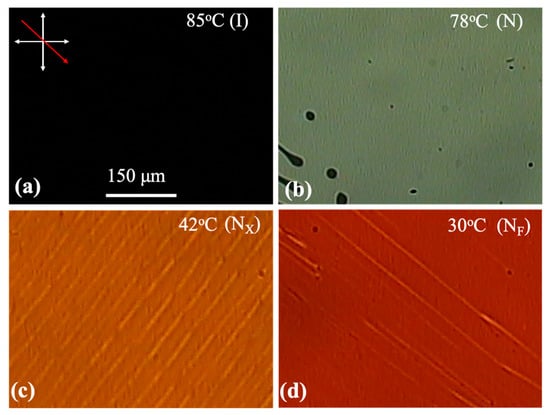

Polarizing optical microscopy (POM) studies were carried out using Olympus BX60, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan in sandwich cells between 1 µm and 10 µm thicknesses, with the surfaces treated for planar alignment by PI2555 polyimide coating on the substrates and then rubbing; the substrates were assembled with parallel rubbing directions. This surface treatment and thickness resulted in a uniform planar alignment and made reliable mesophase determination possible. The temperature dependences of the POM images provided the phase sequence (I-79 °C-N-42 °C-NX-30 °C-NF), which disagrees slightly with the originally reported transition temperatures [33]. The small differences in phase transition temperatures observed are understandable given (a) differences in temperature control performance in various instruments, and (b) that FNLC-919 is a mixture and measurements were performed on different batches as received from the manufacture, which likely do not have exactly matching compositions. Representative textures for a 2 µm cell in each phase are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Representative polarizing optical microscopy (POM) textures for a 2 µm cell in the isotropic (I), N, NX, and NF phases. (a) Isotropic phase, (b) nematic phase, (c) NX phase, (d) NF phase.

The texture in the NX phase shows a faint stripe texture perpendicular to the rubbing direction with a periodicity of about 10 μm. POM images where the crossed polarizers are parallel to the rubbing direction and with polarizers uncrossed by and , are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. They show that the director structure in between the defect lines (or walls) is uniformly parallel or perpendicular to the rubbing direction. Uncrossing the polarizers by , it appears that the defect lines break into oppositely twisted structures. Based on these, we suggest that in adjacent domains the director is slightly tilted (in opposing directions) with respect to the rubbing directions: so-called chevron structures as they have been termed in SmC* materials [37,38]. These have also been reported in the intermediate phase between N and NF in the prototypical material, DIO [6,39], in the antiferroelectric SmZA phase. We note that in other film thicknesses the stripe system seen in the NX phase of the 2 µm film are much less regular. On cooling the sample to the NF phase, we observe a few lines along the rubbing direction that might indicate domains with opposite polarization along the rubbing direction, as was observed and analyzed before [10,16].

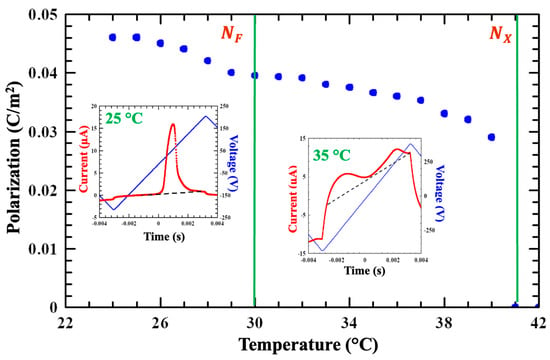

Polarization measurements employed planar cells with separation and in-plane electrodes on one substrate separated by 1. This is the standard geometry for accurate measurement of ferroelectric polarization of ferroelectric nematic liquid crystals [10]. The samples were heated to the isotropic phase and then cooled to the NX phase at 1 °C/min. Polarization was determined using the triangle wave technique [40,41] at a frequency of 80 Hz and a maximum potential difference up to 500 V applied between plane electrodes separated by a gap. The temperature dependence of the ferroelectric polarization is shown in the main pane of Figure 2. The inset shows representative examples of the ferroelectric and antiferroelectric current peaks.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the ferroelectric polarization measured on a 10 µm film with in –plane electrodes. Insets show the time dependences of the electric currents at 25 °C in the NF phase and at 35 °C in the NX phase. The vertical green lines indicate where the phase transitions were observed. The black, dashed lines in the insets represent the baseline for establishing the ferroelectricity peaks.

The polarization is about 0.04 C/m2 just below the N-NX transition and increases by about 15% throughout the NX phase. In the NX phase the polarization current shows two distinct peaks: the first where the applied potential difference is negative and the second where it is positive, as shown in the right inset of Figure 2. This signifies antiferroelectricity, where the polarization vector oscillates in space so that the net dipole moment vanishes [37,38]. In the NF phase, the polarization current shows a single peak signifying a true ferroelectric phase (see left inset in Figure 2); the polarization reaches 0.045 C/m2 at 25 °C, in agreement with published values [24].

Polarization is directly related to both the molecular dipole and the density. Other materials exhibiting the NF phase have reported densities substantially higher than typical liquid crystals [19,42], even as much as 1.54 g/cm3 [38]. Being a mixture, the concept of molecular dipole for FNLC-919 is not straightforward, but we can report its density. Mass density measurements were obtained by placing a pre-weighed mass of FNLC 919 in a precision borosilicate glass capillary with a calibrated bore. The material volume was then obtained by measuring the height of the resulting column. These measurements provided the density of FNLC919 at 25 °C as —which is in between previously reported NF materials and the highest ever reported.

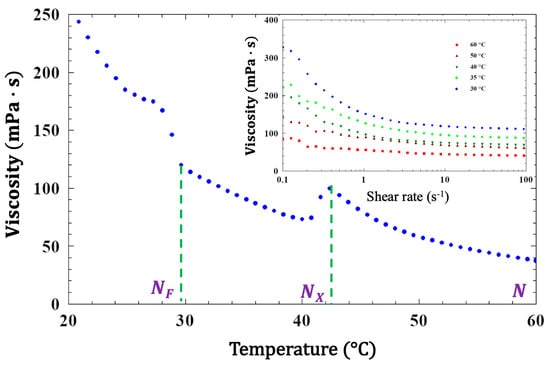

Flow viscosity measurements were carried out in a 25 mm diameter cone plate Anton–Paar rheometer with 49 µm cell gap. The temperature dependence of the bulk viscosity is shown in Figure 3 at . The viscosity increases on cooling from about at 60 °C to at 20 °C. Remarkably, the viscosity shows a sharp ~30% decrease upon transition to the NX phase. In the shear rate range, the viscosity decreases at increasing shear rates, indicating shear thinning behavior; this may be evidence of shear alignment. This manner of temperature dependence was also observed in the compound DIO [43].

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of the flow viscosity of FNLC 919 at shear rate. The inset shows the shear rate dependence of the viscosity at various temperatures in the three mesophases in shear rate range.

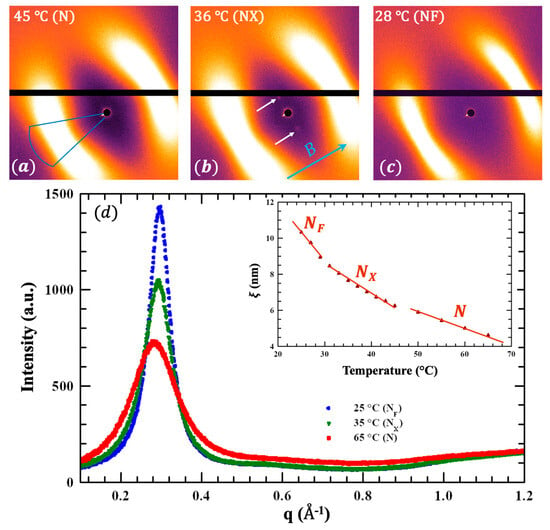

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) studies were carried out by a Xeuss 3.0 (U)SAXS-WAXS instrument, Xenocs SAS, Grenoble, France. FNLC-919 was filled in a 2 mm X-ray capillary held in a temperature-controlled housing. Samarium cobalt permanent magnets on either side of the capillary (perpendicular to the X-ray beam) provided a constant ~0.5 T magnetic induction. Examples of 2D SAXS images are shown in Figure 4a–c at 45 °C (N phase), 36 °C (NX phase), and 28 °C (NF phase). The blue arrow indicates the magnetic field direction. In all cases we observe diffuse peaks centered at along the field direction. They indicate spatial correlations on a length scale of .

Figure 4.

Summary of X-ray measurements. (a–c) 2D SAXS images (2 h exposure) at representative temperatures in the N (a), NX (b), and NF (c) phases. (d) Intensity of diffuse, wider-angle peaks vs. scattering vector q at three temperatures. Inset: Temperature dependence of the correlation length associated with short range positional order of the molecules along the average director. The white arrows in (b) indicate weak Bragg spots associated with a mass density wave running perpendicular to the director and consistent with the Sm ZA phase. B and the blue arrow depicts the magnetic field direction.

Figure 4d shows the representative SAXS intensity vs. scattering vector in all three mesophases. For this analysis the intensity was integrated over the area of the blue box in Figure 4a. The spatial correlation length ξ is estimated as 2π over the peak full width at half maximum. ξ vs. temperature is shown in Figure 4d. The lines through the data points show three distinct trends. This shows that there is a subtle although measurably distinct temperature dependence in each phase.

A particularly important finding is shown in Figure 4b, which corresponds to the NX phase. Two distinct (although faint) Bragg peaks are centered at nm−1 along the axis, normal to the magnetic field (i.e., normal to the director); this indicates smectic Z-type layering. The q value corresponds to . This is precisely the structure found in DIO [43] and several other materials [37] where the SmZA phase (intermediate between para- and ferroelectric nematic phases) has been confirmed by extensive experimental evidence [37]. These structural studies, along with the demonstration of antiferroelectricity shown in Figure 2 give definitive evidence that the intermediate mesophase in FNLC-919 is positively identified as smectic ZA.

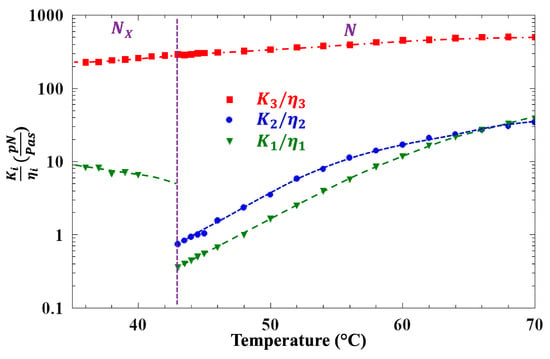

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were conducted on a 4.6 μm thick sample of FNLC-919 contained in an optical sandwich cell treated with parallel rubbed polyimide alignment layers. This geometry is required to (a) minimize static scattering, and (b) eliminate twist domains in the NF phase. The sample was placed in a temperature-controlled oven with optical access and illuminated with 532 nm laser light (focused waist ~30 μm). Time correlation functions of the depolarized scattered light intensity were recorded as a function of temperature for scattering geometries that isolate contributions from the splay, twist, and bend director fluctuations in the nematic phase. The scattered field correlation function in each case was analyzed to extract the relaxation rate (Γ) of the corresponding director fluctuations. The temperature dependence of the ratios of Γ to the square of the scattering vector (q2) is presented in Figure 5. In the nematic phase, the ratios represent the ratio of the splay, twist, or bend elastic constant to the corresponding orientational viscosity—i.e., , , or . Both and show strong pre-transitional decreases above the N to NX transition, while varies smoothly across the transition. Similarly, the pre-transitional behavior of these parameters was observed in the compound DIO [44]. The absence of any pre-transitional effect on is consistent with an N-SmZA transition, since in this case the layers form parallel to the director, and bend fluctuations would not disrupt the layer structure. In the NX phase, the ratio Γ/q2, measured in the geometry that corresponds to splay fluctuations in the N phase, increases 20-fold from its value at the transition. As argued in Ref. [44], the splay and twist director fluctuations in the SmZA phase are coupled due to the unusual layer structure, with the director lying parallel to the layers, and the dispersion of Γ measured in DIO for scattering angles ranging between the normal twist and splay scattering geometries was explained by this coupling. Unfortunately, we were unable to measure Γ reliably in the twist geometry in the NX phase of FNLC919 due to contamination from strong static scattering at a low angle.

Figure 5.

Ratio of relaxation rates to scattering wavenumber squared (Γ/q2) vs. temperature obtained from light scattering measurements on a 4.6 µm planar-aligned FNLC 919 sample. In the nematic phase, Γ/q2 corresponds to the ratio of the splay, twist, or bend elastic constant to the corresponding orientational viscosity—namely, (green points in N phase), (blue points in N phase), and (red points in N phase).

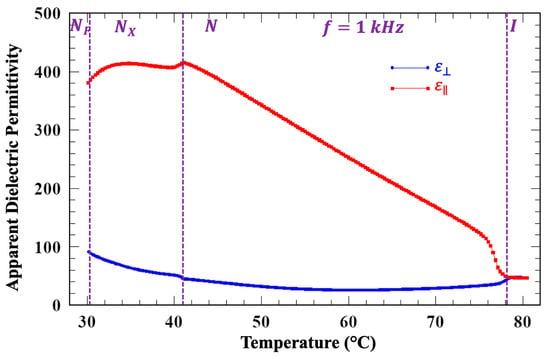

To measure the apparent dielectric constants, we measured the current produced by a sine-wave potential in an FNLC-919 sample. Specifically, we used a Princeton Applied Research Model 181 Princeton Applied Research, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, current-to-voltage preamplifier and a Stanford Research Systems 830 lock-in amplifier, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA to simultaneously measure the in-phase and out-of-phase current. For each elastic constant, the cell thickness and rubbing direction were chosen so as to observe the relevant Freedericksz transition (splay, twist or bend) at an attainable external field. The ratio of the out-of-phase current to the voltage then yields the apparent dielectric permittivity. To determine the material was held in a 7.3 μm thick sandwich cell with planar alignment. was measured using a cell having 9.8 μm spacing with surfaces treated for homeotropic alignment (in the N and NX phases). For all measurements reported here, the applied potential was and . [45]. For both cells, prior to introducing the LC material, the empty cell capacitance was measured. These data do not extend into the NF phase because of the well-documented issues with determining material dielectric constants using capacitance measurements [46,47], as well as the difficulty in obtaining homeotropic alignment in this phase. These results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Apparent perpendicular and parallel component of the real part of the dielectric permittivity vs. temperature measured in cooling at 1 kHz under 4 mV input voltage.

In the N phase increases from at the I-N transition to , while remains almost constant indicating positive dielectric anisotropy () increasing to about 360 at the transition to the NX phase. Such a large dielectric anisotropy is either an artifact related to ferroelectric clusters or due to the large dipole moment (), which is likely over 9D.

How might we understand such a large Δε? Since this material does exhibit an underlying ferroelectric phase, the effective molecular dipole μmol must be fairly large, presumably greater than 9D. Yet, according to Maier-Meier theory [48], this in and of itself is likely not enough. While a large molecular dipole results in large Δε, orientational correlations between dipoles enhance this effect substantially. Roughly, the result for Δε can be explained with a Kirkwood correlation factor (g) of about 4. That is, for every antiparallel dipole pair, there are four parallel pairs. This can be contrasted to 5CB, in which g is around unity [49]; indeed, water at standard temperature (0 °C) and pressure (1 bar), which is known to be highly coordinated, also has g around 4 [50]. It must be stated that the mechanism noted here is presented as being plausible, and certainly not definitive—especially given that we are considering a mixture containing an unspecified number of compounds.

In the NX phase, is increasing and is decreasing, and thus the apparent is decreasing. The reason for this is less clear, although the measurements in Figure 2 indicate that this phase is antiferroelectric; we can speculate that this may be the effect of decreasing correlation between molecular dipoles. Such an effect would require independent confirmation which is beyond the scope of this work.

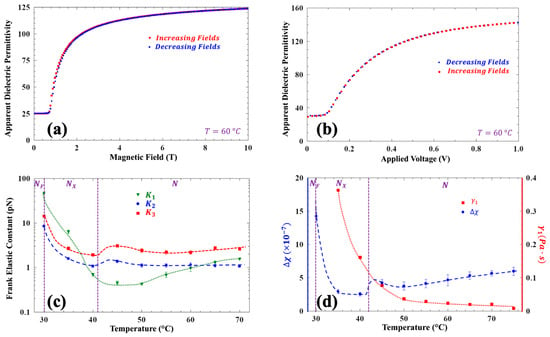

The Frank elastic constants for FNLC-919 were determined via observing the Freedericksz transitions in this material. The results of magnetic and electric Freedericksz transition measurements are shown in Figure 7a and Figure 7b, respectively. The calculated temperature-dependent Frank elastic constants are shown in Figure 7c, and the temperature dependences of the diamagnetic anisotropy and rotational viscosity are represented in Figure 7d. All calculations employed to determine elastic constants are described in Ref [51].

Figure 7.

Magnetic field and applied voltage dependences of the apparent dielectric constant, the temperature dependences of the Frank elastic constants, the diamagnetic anisotropy, and the rotational viscosities. (a) Magnetic field dependence of the apparent dielectric constant at 60 °C in the N phase; (b) 1 kHz sinusoidal applied voltage dependence of the apparent dielectric constant at 60 °C; (c) temperature dependences of the Frank elastic constants calculated from Freedericksz measurements in the N and NX phases; (d) temperature dependence of the diamagnetic anisotropy calculated from magnetic Freedericksz measurements in the N and NX phases (left axis) and of the rotational viscosity calculated from the relaxation time of the magnetic measurements.

Specifically, in the splay geometry, the threshold voltage Vth for the electric field-induced Freedericksz transition is ; an example is shown in Figure 7b. Using from the previously described measurements allows for the determination splay constant, K11. In the same geometry, when inducing the Freedericksz transition with a magnetic field, the threshold is given by , where d is the separation between the substrates. Using the value of K11 from the electric Freedericksz transition measurement, we then obtain diamagnetic anisotropy, as shown in Figure 7d.

For the magnetically induced bend and twist Freedericksz transitions, we employed different geometries. For the bend transition, we used homeotropic alignment with a magnetic field parallel to the substrates. For the twist transition, we used planar alignment with a magnetic field parallel to the substrates and perpendicular to the rubbing direction. In both cases, we detected the onset of the Freedericksz transitions via measuring the capacitance. The threshold field for the bend transition is ; using the previously determined Δχ we obtained the bend elastic constant, K33. For the twist Freedericksz threshold measurements, we used a cell with planar alignment (9 µm cell gap) and in-plane electrodes with a separation of 15 µm on one substrate—the rubbing direction was perpendicular to the probe electric field. In the undistorted state, the director is everywhere parallel to the director and so the capacitance will be proportional to ε||. Above the twist transition, the director turns away from the probe electric field, and we see a contribution from . Even though the precise relationship between the capacitance and twist angle is complex, the onset of twist, i.e., the Freedericksz transition, is plainly observed—c.f. Figure S3. The threshold gives the twist constant, K22. All elastic constants in the N and NX phase are shown in Figure 7c. When in the NF phase, as the standard Freedericksz transition is not present, this approach for measuring elastic constants is not applicable.

The relaxation from the Freedericksz transition-induced distorted state provides insight into the orientational viscosity. When the external field is abruptly decreased from a value above the threshold to zero, the effective birefringence decays exponentially, characterized by a time constant τ = , where is the orientational viscosity. The representative time dependence of the birefringence upon the electric field removal at 75 °C is shown in Figure S4. Although backflow effects are theoretically anticipated in this configuration, they are not expected to significantly influence the decay time constant [52]. The temperature dependence of the rotational viscosity is shown in Figure 7d. It increases from at 70 °C in the N phase to at 35 °C in the NX phase, without showing a significant change at the N-NX transition. This suggests a continuous change in the molecular ordering across the phase boundary. Furthermore, the absolute values of are comparable to those reported for conventional calamitic nematics.

3. Conclusions

The room-temperature NF mixture FNLC-919, made and distributed by Merck Electronics, KGaA, is a prime candidate as a “reference material” for expanded studies of the recently established ferroelectric nematic (NF) phase. This material is stable, readily available, and the relevant mesophases lie in convenient temperature ranges, including a room-temperature NF phase. This latter attribute also renders FNLC-919 attractive for the further development of applications exploiting the ferroelectric nematic state, many of which have been proposed.

In this work, we report a comprehensive set of measurements of those material properties, such as temperature-dependent ferroelectric polarization, flow and rotational viscosity, Frank elastic constants, and diamagnetic anisotropy values, that will be necessary to enhance the future use of this material for both fundamental studies and novel technologies.

Additionally, dynamic light scattering measurements show that the NX phase of FNLC 919, which is intermediate between the nematic and ferroelectric nematic phase, match qualitatively with another material (DIO) with a similar, intermediate phase. In contrast to DIO, FNLC-919 exhibits the NF phase at a lower temperature (closer to ambient) NF phase, although with slightly smaller polarization but larger polarization in the SmZA phase than that in DIO. Small-angle X-ray measurements confirm that the previously labeled NX phase in FNLC-919 indeed has long-range smectic Z positional ordering. Moreover, polarization measurements reveal that the NX phase is antiferroelectric and temperature-dependent viscosity measurements also show similar behavior to the SmZA of the DIO. We are therefore confident in establishing the previously identified NX phase of FNLC-919 as a useful reference exemplar of the smectic ZA mesophase.

We show that the polarization increases from 3 µC/cm2 to 4 µC/cm2 in the SmZA phase and further to 4.6 µC/cm2 by reaching the room temperature in the NF phase. The flow viscosity that shows shear thinning behavior increases from at 60 °C to at a shear rate. Similarly, the rotational viscosity increases on cooling from less than at 60 °C to in the middle of the SmZA phase. The twist and bend Frank elastic constant values are similar to those of the conventional N phase, being in the few pN range, whereas the splay constant is below 1 pN in the N phase, then strongly increases in the SmZA phase to about 50 pN before reaching the NF phase. Unlike in conventional nematic materials where the diamagnetic anisotropy increases on cooling, here we find it to slightly decrease in the N phase, then strongly increase in the SmZA phase, when approaching the NF phase.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ma18245496/s1, Figure S1: POM images of a 2 µm FNLC 919 film in the NX phase at 36 °C. In the central texture where the crossed polarizers are parallel/perpendicular to the rubbing direction. Top textures at the left (right) correspond polarizers uncrossed by (). Bottom textures at the left (right) correspond polarizers uncrossed by (); Figure S2: Phase sequence by polarizing optical microscopy of FNLC-919 ferroelectric nematic liquid crystal for a 1 μm cell. (a) 85 °C in the isotropic phase; (b) 80 °C right below the I-N phase transition; (c) 42 °C in the NX phase; (d) 30 °C in the NF phase; Figure S3: Magnetic field dependence of the capacitance indicative of the twist Freedericksz transition in an in-plane switching cell at 65 °C; Figure S4: Time dependence of the birefringence upon the removal of the electric field at 75 °C. Blue line is a fit corresponding to single exponential function.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and A.J.; Methodology, S.S. and J.T.G.; Software, A.P.; Formal analysis, M.P., M.B., A.G., N.P.D., A.J. and J.T.G.; Investigation, A.P., M.P., M.B., A.G. and N.P.D.; Writing—original draft, A.P. and J.T.G.; Visualization, S.S.; Supervision, A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMR-2210083).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The material FNLC919 was provided by Merck Electronics KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reinitzer, F. Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Cholesterins. Monatshefte Chem. Verwandte Teile Anderer Wiss. 1888, 9, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jákli, A.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Selinger, J.V. Physics of Liquid Crystals of Bent-Shaped Molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, L.A.; Dingemans, T.J.; Nakata, M.; Samulski, E.T. Thermotropic Biaxial Nematic Liquid Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 145505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandle, R.J. A Ten-Year Perspective on Twist-Bend Nematic Materials. Molecules 2022, 27, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Aya, S.; Huang, M. Review of Emergent Polar Liquid Crystals from Material Aspects. Liq. Cryst. Rev. 2024, 12, 149–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Shiroshita, K.; Higuchi, H.; Okumura, Y.; Haseba, Y.; Yamamoto, S.I.; Sago, K.; Kikuchi, H. A Fluid Liquid-Crystal Material with Highly Polar Order. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandle, R.J.; Cowling, S.J.; Goodby, J.W. A Nematic to Nematic Transformation Exhibited by a Rod-like Liquid Crystal. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 11429–11435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Máthé, M.T.; Perera, K.; Buka, Á.; Salamon, P.; Jákli, A. Fluid Ferroelectric Filaments. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2305950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosik, A.; Nádasi, H.; Schwidder, M.; Manabe, A.; Bremer, M.; Klasen-Memmer, M.; Eremin, A. Fluid Fibers in True 3D Ferroelectric Liquids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2313629121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Korblova, E.; Dong, D.; Wei, X.; Shao, R.; Radzihovsky, L.; Glaser, M.A.; MacLennan, J.E.; Bedrov, D.; Walba, D.M.; et al. First-Principles Experimental Demonstration of Ferroelectricity in a Thermotropic Nematic Liquid Crystal: Polar Domains and Striking Electro-Optics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14021–14031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nishikawa, H.; Kougo, J.; Zhou, J.; Dai, S.; Tang, W.; Zhao, X.; Hisai, Y.; Huang, M.; Aya, S. Development of Ferroelectric Nematic Fluids with Giant-Dielectricity and Nonlinear Optical Properties. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, 5047–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, R.; Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Kougo, J.; Lei, H.; Dai, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; et al. How Far Can We Push the Rigid Oligomers/Polymers toward Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystals? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17857–17861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pociecha, D.; Walker, R.; Cruickshank, E.; Szydlowska, J.; Rybak, P.; Makal, A.; Matraszek, J.; Wolska, J.M.; Storey, J.M.D.; Imrie, C.T.; et al. Intrinsically Chiral Ferronematic Liquid Crystals: An Inversion of the Helical Twist Sense at the Chiral Nematic—Chiral Ferronematic Phase Transition. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 361, 119532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, G.J.; Górecka, E.; Hobbs, J.; Pociecha, D. Fluorination: Simple Change but Complex Impact on Ferroelectric Nematic and Smectic Liquid Crystal Phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 6058–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, N.; Čopič, M.; Mertelj, A. Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid-Crystalline Phases. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 106, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Nepal, P.; Feng, C.; Hossain, M.S.; Fukuto, M.; Li, R.; Gleeson, J.T.; Sprunt, S.; Twieg, R.J.; Jákli, A. Multiple Ferroelectric Nematic Phases of a Highly Polar Liquid Crystal Compound. Liq. Cryst. 2022, 49, 1784–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcz, J.; Herman, J.; Rychłowicz, N.; Kula, P.; Górecka, E.; Szydlowska, J.; Majewski, P.W.; Pociecha, D. Spontaneous Chiral Symmetry Breaking in Polar Fluid–Heliconical Ferroelectric Nematic Phase. Science 2024, 384, 1096–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Martinez, V.; Nacke, P.; Korblova, E.; Manabe, A.; Klasen-Memmer, M.; Freychet, G.; Zhernenkov, M.; Glaser, M.A.; Radzihovsky, L.; et al. Observation of a Uniaxial Ferroelectric Smectic A Phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2210062119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guragain, P.; Ghimire, A.; Badu, M.; Dhakal, N.P.; Nepal, P.; Gleeson, J.T.; Sprunt, S.; Twieg, R.J.; Jákli, A. Ferroelectric Nematic and Smectic Liquid Crystals with Sub-Molecular Spatial Correlations. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 8153–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastián, N.; Mandle, R.J.; Petelin, A.; Eremin, A.; Mertelj, A. Electrooptics of Mm-Scale Polar Domains in the Ferroelectric Nematic Phase. Liq. Cryst. 2021, 48, 2055–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, M.T.; Farkas, B.; Péter, L.; Buka, Á.; Jákli, A.; Salamon, P. Electric Field-Induced Interfacial Instability in a Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, R.; Marni, S.; Ciciulla, F.; Mir, F.A.; Nava, G.; Caimi, F.; Zaltron, A.; Clark, N.A.; Bellini, T.; Lucchetti, L. Explosive Electrostatic Instability of Ferroelectric Liquid Droplets on Ferroelectric Solid Surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207858119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, M.T.; Buka, Á.; Jákli, A.; Salamon, P. Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal Thermomotor. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 105, L052701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, M.T.; Himel, M.S.H.; Adaka, A.; Gleeson, J.T.; Sprunt, S.; Salamon, P.; Jákli, A. Liquid Piezoelectric Materials: Linear Electromechanical Effect in Fluid Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medle Rupnik, P.; Cmok, L.; Sebastián, N.; Mertelj, A. Viscous Mechano-Electric Response of Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.; Máthé, M.T.; Salamon, P.; Gleeson, J.T.; Jakli, A. From Solid to Liquid Piezoelectric Materials. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 8920–8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zou, Y.; Tang, W.; Li, J.; Huang, M.; Aya, S. Spontaneous Electric-Polarization Topology in Confined Ferroelectric Nematics. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovšin, M.; Petelin, A.; Berteloot, B.; Osterman, N.; Aya, S.; Huang, M.; Drevenšek-Olenik, I.; Mandle, R.J.; Neyts, K.; Mertelj, A.; et al. Patterning of 2D Second Harmonic Generation Active Arrays in Ferroelectric Nematic Fluids. Giant 2024, 19, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folcia, C.L.; Ortega, J.; Vidal, R.; Sierra, T.; Etxebarria, J. The Ferroelectric Nematic Phase: An Optimum Liquid Crystal Candidate for Nonlinear Optics. Liq. Cryst. 2022, 49, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Lei, H.; Song, Y.; Peng, W.; Zhang, X.; Aya, S.; Huang, M. Achieving Enhanced Second-Harmonic Generation in Ferroelectric Nematics by Doping D-π-A Chromophores. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2023, 11, 10905–10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanov, V.; Kavčič, A.; Kokkinakis, E.; Sebastián, N.; Chekhova, M.V.; Humar, M. Tunable Entangled Photon-Pair Generation in a Liquid Crystal. Nature 2024, 631, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Yang, D.; Saadaoui, L.; Wang, Y.; Drevensek-Olenik, I.; Qiu, Z.; Shao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Bulk Photovoltaic Effect in Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystals. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-H. Alignment Properties of a Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal on the Rubbed Substrates. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 2446–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, K.; Haputhantrige, N.; Hossain, S.; Mostafa, M.; Adaka, A.; Mann, E.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Jákli, A. Electrically Tunable Polymer Stabilized Chiral Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal Microlenses. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2302500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himel, M.S.H.; Perera, K.; Adaka, A.; Guragain, P.; Twieg, R.J.; Sprunt, S.; Gleeson, J.T.; Jákli, A. Electrically Tunable Chiral Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal Reflectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2413674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, M.; Perera, K.; Mostafa, M.; Gill, M.; Nepal, P.; Guragain, P.; Landau, I.; Kula, P.; Twieg, R.; West, J.L.; et al. Optically Isotropic Polymer Stabilized Liquid Crystals with Fast and Large Field-Induced Refractive Index Variation. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacke, P.; Manabe, A.; Klasen-Memmer, M.; Chen, X.; Martinez, V.; Freychet, G.; Zhernenkov, M.; Maclennan, J.E.; Clark, N.A.; Bremer, M.; et al. New Examples of Ferroelectric Nematic Materials Showing Evidence for the Antiferroelectric Smectic-Z Phase. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Martinez, V.; Korblova, E.; Freychet, G.; Zhernenkov, M.; Glaser, M.A.; Wang, C.; Zhu, C.; Radzihovsky, L.; Maclennan, J.E.; et al. The Smectic ZA Phase: Antiferroelectric Smectic Order as a Prelude to the Ferroelectric Nematic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217150120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Basnet, B.; Wang, H.; Guragain, P.; Baldwin, A.; Twieg, R.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Gleeson, J.; Jakli, A.; Sprunt, S. Director-Layer Dynamics in the Antiferroelectric Smectic-ZA Phase of a Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12541. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.S.; Goodby, J.W. The Dependence of the Magnitude of the Spontaneous Polarization on the Cell Thickness in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987, 137, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasato, K.; Abe, S.; Takezoe, H.; Fukuda, A.; Kuze, E. Direct Method with Triangular Waves for Measuring Spontaneous Polarization in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 2 Lett. 1983, 22, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton-Barr, C.; Gleeson, H.F.; Mandle, R.J. Room-Temperature Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal Showing a Large and Diverging Density. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Salamon, P.; Máthé, M.T.; Jákli, A.; Araoka, F. Giant Electro-Viscous Effects in Polar Fluids with Paraelectric–Modulated Antiferroelectric–Ferroelectric Phase Sequence. Giant 2025, 22, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Basnet, B.; Wang, H.; Guragain, P.; Baldwin, A.R.; Twieg, R.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Gleeson, J.T.; Jakli, A.; Sprunt, S. Dynamics of the Antiferroelectric Smectic-Z A Phase in a Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystal. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 8510–8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, H.; Scheuble, B.; Nehring, J. On the Field Dependence of the Optical Phase Difference and Capacitance of Nematic Layers. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 71, 5140–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.A.; Chen, X.; MacLennan, J.E.; Glaser, M.A. Dielectric Spectroscopy of Ferroelectric Nematic Liquid Crystals: Measuring the Capacitance of Insulating Interfacial Layers. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 013195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaka, A.; Rajabi, M.; Haputhantrige, N.; Sprunt, S.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Jákli, A. Dielectric Properties of a Ferroelectric Nematic Material: Quantitative Test of the Polarization-Capacitance Goldstone Mode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 038101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, W.; Meier, G. Eine Einfache Theorie Der Dielektrischen Eigenschaften Homogen Orientierter Kristallinflüssiger Phasen Des Nematischen Typs. Z. Naturforschung–Sect. A J. Phys. Sci. 1961, 16, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavvou, E.E.; Ramou, E.; Ahmed, Z.; Welch, C.; Mehl, G.H.; Vanakaras, A.G.; Karahaliou, P.K. Dipole–Dipole Correlations in the Nematic Phases of Symmetric Cyanobiphenyl Dimers and Their Binary Mixtures with 5CB–Soft Matter (RSC Publishing). Soft Matter 2023, 19, 9224–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hutter, J.; Sprik, M. Computing the Kirkwood g–Factor by Combining Constant Maxwell Electric Field and Electric Displacement Simulations: Application to the Dielectric Constant of Liquid Water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 2696–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gennes, P.-G. The Physics of Liquid Crystals; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1974; ISBN 0198512856. [Google Scholar]

- Brochard, F. Backflow Effects in Nematic Liquid Crystals. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1973, 23, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).