Novel Alginate-, Cellulose- and Starch-Based Membrane Materials for the Separation of Synthetic Dyes and Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions and Suspensions—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

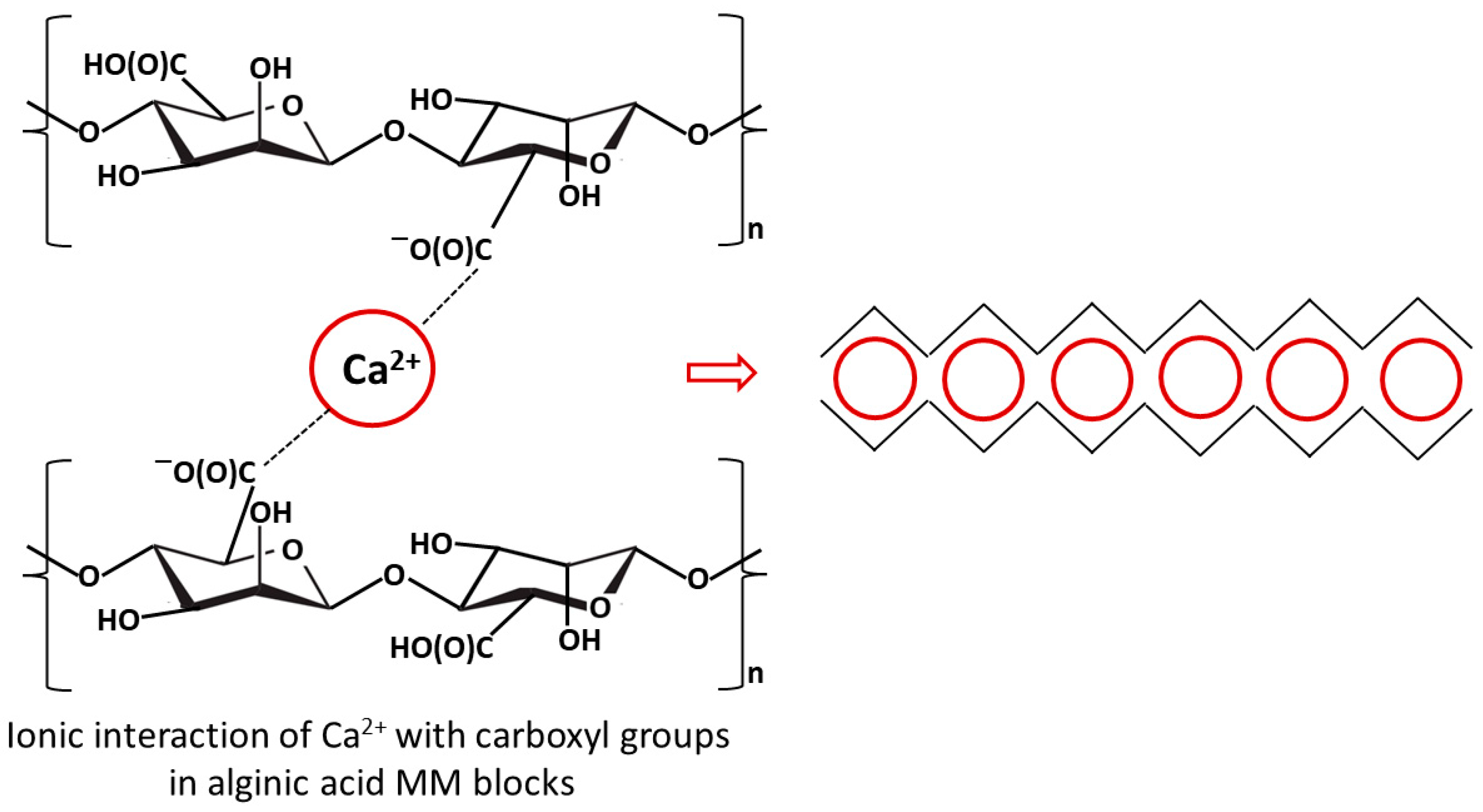

2. Alginates

2.1. Hydrogel Alginate-Based Membranes

2.2. Aerogel Alginate-Based Membranes

3. Cellulose and Its Derivatives

Cellulose Triacetate-Based Membranes

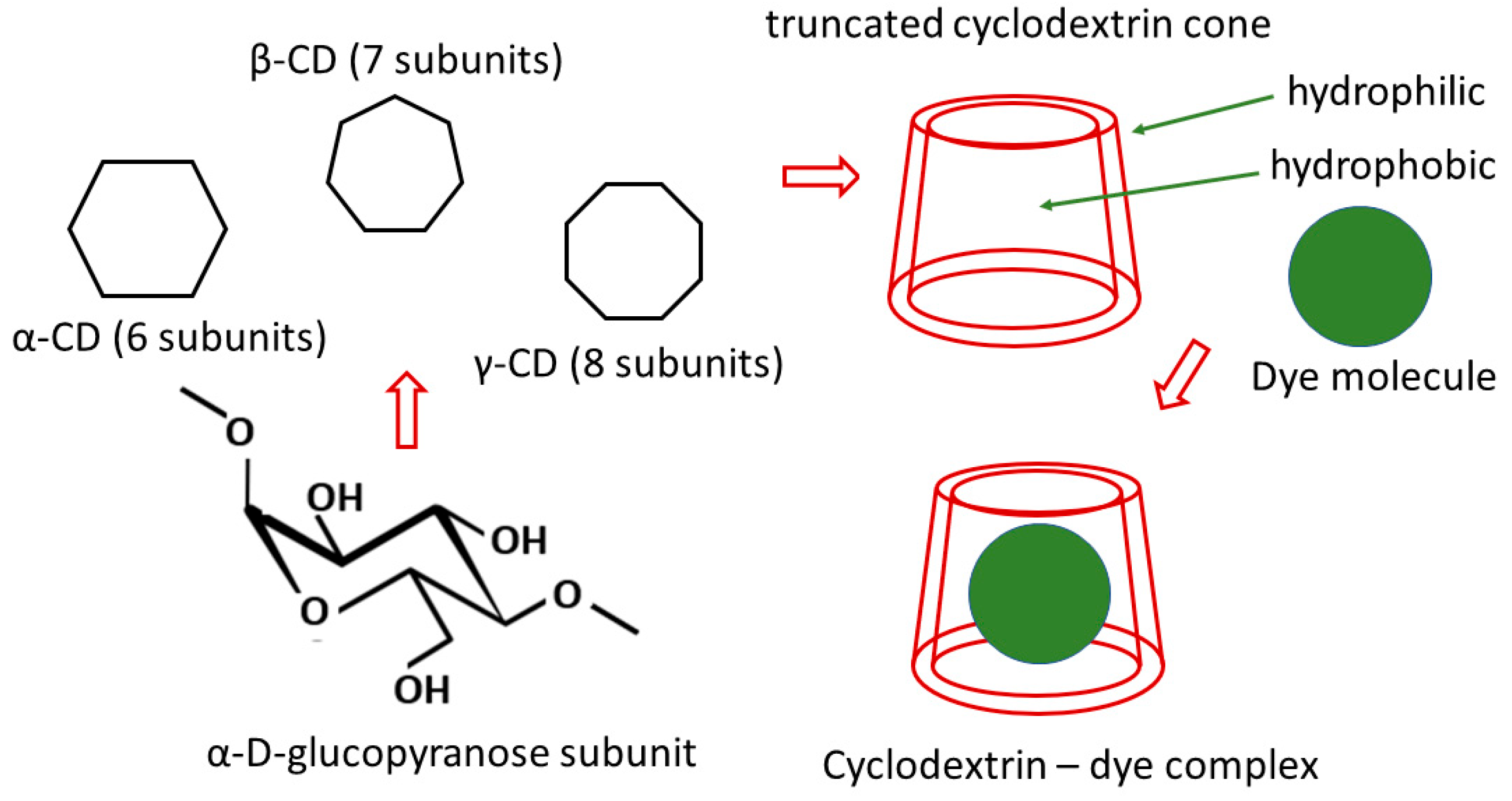

4. Starch and Cyclodextrin

4.1. Starch-Based Membranes

4.2. Cyclodextrins-Based Membranes

5. A Brief Summary of the Results Achieved Earlier Using Selected Polysaccharide-Based Membranes

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolya, H.; Kang, C.-W. Next-Generation Water Treatment: Exploring the Potential of Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposites in Adsorption and Membrane Filtration. Polymers 2023, 15, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Wu, M.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, B.; Shao, M.; Zhao, X. Textile Printing and Dyeing Wastewater: A Comprehensive Profiling and In-Depth Examination of Sustainable Treatment Strategies. Chemistry Select 2025, 10, e05659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Jamil, F.; Rashad, M.A.; Hussain, M.; Inayat, A.; Akhter, P.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Park, Y.K. Wastewater from the textile industry: Review of the technologies for wastewater treatment and reuse. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 2060–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktoryová, N.; Szarka, A.; Hrouzková, S. Recent Developments and Emerging Trends in Paint Industry Wastewater Treatment Methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, R.; Wang, R.; Sun, W.; Luo, Y.; Yu, Z. Technological advances and sustainable strategies for electrolytic manganese wastewater treatment: A critical review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 199, 107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toczyłowska-Mamińska, R.; Mamiński, M.Ł. Wastewater as a Renewable Energy Source—Utilisation of Microbial Fuel Cell Technology. Energies 2022, 15, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutair, M.; Kumar, R.; Al-Mur, B.A.; Mohamed, O.A.; Barakat, M.A. An overview of metals extraction and recovery from industrial wastewater sludge. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 102, 2892–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mavukkandy, M.O.; Giwa, A.; Elektorowicz, M.; Katsou, E.; Khelifi, O.; Naddeo, V.; Hasan, S.W. Recent developments in hazardous pollutants removal from wastewater and water reuse within a circular economy. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obotey Ezugbe, E.; Rathilal, S. Membrane Technologies in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, R.; Abbas, M.K.G.; Al-Ejji, M. Environmental remediation and the efficacy of ceramic membranes in wastewater treatment—A review. Emerg. Mater. 2024, 7, 1295–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Abetz, V. Nonequilibrium Processes in Polymer Membrane Formation: Theory and Experiment. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 14189–14231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Bi, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. High-performance calcium alginate hydrogel composite nanofiltration membrane for dyeing wastewater separation. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.-J.; Jiang, S.-K.; Chao, X.-Y.; Zhang, C.-X.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Liu, M.-L.; Sun, S.-P. Removing miscellaneous heavy metals by all-in-one ion exchange-nanofiltration membrane. Water Res. 2022, 222, 118888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoja-López, K.A.; Quiroz-Suárez, K.A.; Dueñas-Rivadeneira, A.A.; Maddela, N.R.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M.; Luque, R.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M. Polymeric membranes functionalized with nanomaterials (MP@NMs): A review of advances in pesticide removal. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandehali, S.; Sanaeepur, H.; Amooghin, A.E.; Shirazian, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Biodegradable polymers for membrane separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 269, 118731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, M.A.; Bożejewicz, D.; Witt, K. The Application of Polymer Inclusion Membranes for the Removal of Emerging Contaminants and Synthetic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions—A Mini Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, S.; Davarnejad, R.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F. Membranes based on non-synthetic (natural) polymers for wastewater treatment. Polym. Test. 2020, 84, 106381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidi, F.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Amooghin, A.E.; Saeb, M.R.; Xiao, H.; Jin, Y.; Rezakazemi, M. Biopolymer-based membranes from polysaccharides for CO2 separation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1083–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shen, P.; Peng, Q. Structures, properties and application of alginic acid: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Gao, C.; Avérous, L. Alginate-based materials: Enhancing properties through multiphase formulation design and processing innovation. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2024, 159, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, V.U.; Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ab Hamid, N.H.; Khoo, P.S.; Chowdhury, A.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Rani, M.S.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Alginate-based materials as adsorbent for sustainable water treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 298, 139946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Xiong, H.; Li, C. Superstrong Alginate Aerogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2501094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Long, A.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, S.; et al. Recent advances in alginate-based hydrogels for the adsorption–desorption of heavy metal ions from water: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353 Pt B, 128265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, S.; Lyu, S.; Liu, G.; Cao, D. Robust Alginate Aerogel Absorbents for Removal of Heavy Metal and Organic Pollutant. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2018, 12, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Maldonado, E.A.; Abdellaoui, Y.; Abu Elella, M.H.; Abdallah, H.M.; Pandey, M.; Anthony, E.T.; Ghimici, L.; Álvarez-Torrellas, S.; Pinos-Vélez, V.; Oladoja, N.A. Innovative biopolyelectrolytes-based technologies for wastewater treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273 Pt 2, 132895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Yu, D.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, W. Progress in Research on Metal Ion Crosslinking Alginate-Based Gels. Gels 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhao, K.; Xin, Q.; Gao, J.; Shi, J.; Zhong, J.; Wang, H. Ba2+/Ca2+ co-crosslinked alginate hydrogel filtration membrane with high strength, high flux and stability for dye/salt separation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, M.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Z.; Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Lin, L. Insight of multifunctional Cu-alginate hydrogel membrane for precise molecule/ion separation applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, W.; Xie, M.; Seo, D.H.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Van der Bruggen, B. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhao, K.; Xu, L.; Gao, N.; Zhao, H.; Gong, Z.; Yu, L.; Jiang, J. Oxalic acid cross-linked sodium alginate and carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel membrane for separation of dye/NaCl at high NaCl concentration. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1951–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Hou, M.; Wang, M.; Yang, K.; Qi, X.; Li, Q.; Zheng, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Lin, L. OA-NaAlg/CMCS/TiO2@PTFE hydrogel composite membrane crosslinked with oxalic acid for dye/salt separation in acidic conditions. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 734, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hou, M.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Chen, M.; Lin, L. Durable TiO2@Cu-alginate hydrogel membrane with rapid in-situ cleaning for high-performance dye desalination applications. Desalination 2025, 595, 118329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Bi, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Mao, J.; Shan, X.; Cao, J. Synergistic Optimization Strategies for SA-PVA Hydrogel Nanofiltration Membrane Performance by MWCNTs and TiO2. J. Polym. Environ. 2025, 33, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Tan, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Lu, J.; Ding, M.; Meng, C.; Liu, W.; et al. Self-supported hydrogel loose nanofiltration membrane for dye/salt separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 124982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, J.; Jiang, J.; Xie, W.; Yang, Z.; Lin, L.; Zhang, W.; Chu, R.; et al. Anti-fouling and anti-bacterial graphene oxide/calcium alginate hybrid hydrogel membrane for efficient dye/salt separation. Desalination 2022, 538, 115908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoor, S.; Kandel, D.R.; Chang, S.; Karayil, J.; Lee, J. Carrageenan/calcium alginate composite hydrogel filtration membranes for efficient cationic dye separation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270 Pt 2, 132309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Y.; Cai, R.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y. Sodium alginate-based nanocomposite hydrogel membrane for removal of heavy metal ions and dyes in water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307 Pt 2, 142109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Xue, Y.; Liang, J.; Tu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, Z. Traditional gel nanofiltration membranes doped with ball-milled crayfish shell biochar for high-selectivity dye/salt separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhursani, S.A.; Barai, H.R.; Alshangiti, D.M.; Al-Gahtany, S.A.; Ghobashy, M.M.; Atia, G.A.N.; Madani, M.; Kundu, M.K.; Joo, S.W. pH-Sensitive Hydrogel Membrane-Based Sodium Alginate/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Cross-Linked by Freeze–Thawing Cycles for Dye Water Purification. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dai, K.; Xiang, H.; Kou, J.; Guo, H.; Ying, H.; Wu, J. High adsorption capacities for dyes by a pH-responsive sodium alginate/sodium lignosulfonate/carboxylated chitosan/polyethyleneimine adsorbent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278 Pt 3, 135005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tiang, M.F.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Takriff, M.S.; Sajab, M.S.; Abdul, P.M.; Ding, G. Precisely controlled electrostatically sprayed sodium alginate/carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel microbeads as super-adsorbent for adsorption of cationic dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283 Pt 4, 137989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Tian, S. Ethylenediamine-oxidized sodium alginate hydrogel cross-linked graphene oxide nanofiltration membrane with self-healing property for efficient dye separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 670, 121366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, K.; Miao, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, L.; Su, H.; Lin, L.; Hu, Y. High-strength and anti-bacterial BSA/carboxymethyl chitosan/silver nanoparticles/calcium alginate composite hydrogel membrane for efficient dye/salt separation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Xiong, J.; Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Tan, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. A self-supported sodium alginate composite hydrogel membrane and its performance in filtering heavy metal ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Soyekwo, F.; Liu, C. Highly permeable forward osmosis membrane with selective layer “hooked” to a hydrophilic Cu-Alginate intermediate layer for efficient heavy metal rejection and sludge thickening. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 647, 120247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Vatanpour, V.; He, T. Antifouling thin-film nanocomposite NF membrane with polyvinyl alcohol-sodium alginate-graphene oxide nanocomposite hydrogel coated layer for As(III) removal. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, M.; Tang, K.; Pan, B.; Liu, C.; Luo, J.; Pang, X. Multi-crosslinked robust alginate/polyethyleneimine modified graphene aerogel for efficient organic dye removal. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 683, 133034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zang, W.; Peng, M.; Yang, M.; Wang, S.; Xu, C.; et al. Multifunctional polyaniline modified calcium alginate aerogel membrane with antibacterial, oil-water separation, dye and heavy metal ions removal properties for complex water purification. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, A.; Zhang, Y. Superhydrophilic quaternized calcium alginate based aerogel membrane for oil-water separation and removal of bacteria and dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Guo, J.; Gao, N.; Hou, M.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, K.; Lin, L. High-strength, super-hydrophilic alginate electrospun nanofibrous membranes for rapid oil-water emulsion separation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705 Pt 1, 135637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chen, R.; Luo, S.; Yu, W.; Yuan, J.; Lin, F.; Wang, M.; Cao, X.; Liao, Y.; Huang, B.; et al. Regenerated cellulose membranes for efficient separation of organic mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 125118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybek, P.; Dudek, G.; van der Bruggen, B. Cellulose-based films and membranes: A comprehensive review on preparation and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Qi, B.; Cui, Z.; Chen, X.; Wan, Y.; Luo, J. Cellulose-based separation membranes: A sustainable evolution or fleeting trend? Adv. Membr. 2025, 5, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gethami, W.; Qamar, M.A.; Shariq, M.; Alaghaz, A.-N.M.A.; Farhan, A.; Areshif, A.A.; Alnasirg, M.H. Emerging environmentally friendly bio-based nanocomposites for the efficient removal of dyes and micropollutants from wastewater by adsorption: A comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2804–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayl, A.A.; Abd-Elhamid, A.I.; Mosnáčková, K.; Arafa, W.A.A.; Alanazi, A.H.; Ahmed, I.M.; Ali, H.M.; Aly, A.A.; Akl, M.A.; Doma, A.S.; et al. Advances in the modification and applications of cellulosic-based materials for wastewater remediation: A review. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziya, K.; Kotze, I.; Mahlangu, O.T.; Richards, H.L. Low pressure thin film membranes with cellulose nanocrystals derived from Cannabis sativa for enhanced dye and salt removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 366, 132829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, A.; Cheng, G.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Zheng, N.; Cui, J.; Pan, J. Electrostatically repulsion-adjusted self-cleaning BiOCl/CNF/MXene membranes for enhanced dye separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 734, 124479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Meng, T.; Peng, Y.; Su, H.; Chaleawlert-umpon, S.; Li, L. PAF@BC composite membrane for multifunctional environmental Applications: Dye Separation, Degradation, and iodine Adsorption, interception. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364 Pt 3, 132546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Mo, M.; Lin, J.; Ma, X.; Hong, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Huang, L. Cellulose Acetate-Based Polyamide Nanofiltration Membranes by Diethylenetriamine-Assisted Interfacial Polymerization for Effective Removal of Dyes and Salt Ions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 4153–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Luo, S.; Song, Z.; Tian, Y.; Shi, D.; Lu, B.; Liu, H.; Tang, L.; Lin, G.; Shi, J.; et al. Gradient-charged cellulose acetate membranes enabled by ionic COF nanosheets for enhanced nanofiltration-based desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 734, 124391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsalan, M.; Rhithuparna, D.; Khan, M.A.; Rahman, W.R.; Alajmi, M.F.; Hussain, A.; Koo, B.-H.; Halder, G. Multifaceted CA@TiO2 nanocomposite-based thin film composite membrane for advanced separation and environmental detoxification. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.P.; Cui, L.J.; Shi, W.J.; Shi, X.K.; Xu, C. Multifunctional antifouling sustainable membranes integrating MIL-125(Ti) and carboxylated cellulose nanofibers for self-cleaning and dye degradation. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 9103–9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, D.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y. Integrated dual antifouling mechanism onto graphene oxide membranes for dye wastewater treatment: Synergistic effects of photocatalytic and antimicrobial. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378 Pt 3, 134356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Karim, Z.; Pakawanit, P.; Supruangnet, R.; Pongchaikul, P.; Posoknistakul, P.; Laosiripojana, N.; Wu, K.C.W.; Sakdaronnarong, C. TEMPO-oxidized and carbon dots bound cellulosic nanostructured composite for sustainable fully biobased membranes for separation of nano/micro-sized particles/molecules. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 197, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.T.; Raja, V.K.; Arthanareeswaran, G.; Khoa, T.D.; Taweepreda, W. A high-performance nanofiltration membrane synthesized by embedding amino acids and ionic liquids in cellulose acetate for heavy metal separation. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 1966–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M.; Shayani-Jam, H.; Dolatyari, L.; Yaftian, M.R. Membrane Extraction of Bi(III) by a Cellulose Triacetate/Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride-Co-Hexafluoropropylene) Blend Polymer Inclusion Membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncib, S.; Brahmi, K.; Othmen, K.; Lasaad, D.; Elaloui, E.; Bouguerra, W. Enhanced Ni(II) recovery via D2EHPA-cellulose triacetate-based polymer inclusion membranes: Optimized extraction and stability analysis. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2025, 10, 2245–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, Z.; Yue, X.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, T.; Xue, S.; Qiu, F.; Pan, J.; Li, C. A wastes-based hierarchically structured cellulose membrane: Adsorption performance and adsorption mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Chen, X.; Qiu, Z.; Yao, G.; Qiu, F.; Zhang, T. Fabrication of hierarchical porous MgO/cellulose acetate hybrid membrane with improved antifouling properties for tellurium separation. Cellulose 2021, 28, 10549–10563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Huang, F. Construction of biomass-based loose nanofiltration membranes via electrostatic self-assembly and crosslinking collaboration strategy for high-efficiency dye/salt separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre-Celeizabal, A.; Russo, F.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A.; Casado-Coterillo, C.; Garea, A. Green Synthesis of Cellulose Acetate Mixed Matrix Membranes: Structure–Function Characterization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.Y.; Burrows, A.D.; Xie, M. Sustainable Polymeric Membranes: Green Chemistry and Circular Economy Approaches. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 1882–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luca, G.; Galiano, F.; Russo, F.; Tornaghi, S.; Di Nicolò, E.; Mancuso, R.; Gabriele, B.; Figoli, A. Sustainable Membrane Preparation: Approaches Using Cellulose Acetate as a Biopolymer and Ethyl Lactate as a Green Solvent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 9074–9086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, M.A. The Use of Polymer Inclusion Membranes for the Removal of Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions—The Latest Achievements and Potential Industrial Applications: A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczorowska, M.A. The Latest Achievements of Liquid Membranes for Rare Earth Elements Recovery from Aqueous Solutions—A Mini Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaijan, Z.A.; Bahrami, S.; Dolatyari, L.; Farajmand, B.; Yaftian, M.R. Recovery of the Co(II) ions from thiocyanate aqueous solutions using cellulose triacetate/tri-n-octylamine/tributyl phosphate polymer inclusion membranes. Miner. Eng. 2025, 233, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, N.; Dolatyari, L.; Kazemi, D.; Sharafi, H.R.; Shayani-Jam, H.; Yaftian, M.R. Application of a polymer inclusion membrane made of cellulose triacetate base polymer and trioctylamine for the selective extraction of bismuth(III) from chloride solutions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntombela, S.C.; Chimuka, L.; Tutu, H.; Richards, H.; Ndungu, K.; Ardelan, M.V. Behavior of Major Cations in Optimization of Polymer Inclusion Membrane for the Transport of Lithium From Seawater. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wang, D.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, F.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, C. Highly permeable and selective polymer inclusion membrane for Li+ recovery and underlying enhanced mechanism. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 699, 122671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, M.A. Novel and Sustainable Materials for the Separation of Lithium, Rubidium, and Cesium Ions from Aqueous Solutions in Adsorption Processes—A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, B.; Zeytuncu, B.; Koyuncu, I. Efficient Separation and Recovery of Precious Metal Ions by Polymer Inclusion Membranes (PIMs): A Mini Review. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2024, 42, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozejewicz, D.; Kaczorowska, M.A.; Witt, K. Recent advances in the recovery of precious metals (Au, Ag, Pd) from acidic and WEEE solutions by solvent extraction and polymer inclusion membrane processes-a mini-review. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 246, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbanian, M.; Nezhadali, A. Highly selective transport of Ag+ from a mixture of some bivalent cations using polymer inclusion membrane by 2,2′-dithio-bis-benzothiazole as a carrier. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 3125–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde, B.; Fontàs, C.; Anticó, E. A calibration approach for a passive sampler based on a polymer inclusion membrane (PIM) for in situ Zn monitoring in Catalan rivers. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitti, F.; Boliona, A.A.; Nitbani, F.O.; Naat, J.N.; Lapailaka, T.; Kadang, L.; Pingak, R.K.; Kiswandono, A.A. Fabrication of Polymer Inclusion Membrane Using Recycled Polyvinyl Chloride as Sustainable Alternative Support Polymer for the Extraction of Zn(II) From Water. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, C.; Zawierucha, I. Polymer Inclusion Membranes Based on Sulfonic Acid Derivatives as Ion Carriers for Selective Separation of Pb(II) Ions. Membranes 2025, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, M. Polymer Inclusion Membranes (PIMs) for Metal Separation—Toward Environmentally Friendly Production and Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatir, N.; Alcalde, B.; Anticó, E.; Fontàs, C. Polymer inclusion membrane (PIM) extraction technique for assessing metal interactions with organic pollutants and microplastics in aquatic systems. Adv. Sample Prep. 2025, 14, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Hudson, S.M.; El-Shafei, A.; Shamey, R. Diffusion of reactive dyes through cationized cellophane films. Cellulose 2025, 32, 10237–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, D.S.; Santhosh, K.N.; Hemavathi, A.B.; Kalpana, D.; Nataraj, S.K. A sustainable approach to lithium and industrial wastewater separation using recycled cellulose membrane with Zr-functionalized silicate clay. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.X.; Zhang, R.; Cao, S.C.; Chang, N.; Zhang, H. Preparation of grafted starch-based cationic flocculants and its removal of reactive and disperse dyes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Chang, N. Preparation of cationic starch flocculants by etherification, esterification and grafting approach for removal of textile dyes. Iran. Polym. J. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haodi, W.; Wen, L.; Jianjian, X.; Shuxing, Z.; Yujuan, J.; Haibo, L. Research Progress in Starch-based Dye Adsorbents. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2024, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Shen, S.; Liu, D.; Hong, Y.; Sun, S.; Wyman, I. Overview on modified membranes by different polysaccharides and their derivatives: Preparation and performances. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.; Haq, F.; Ullah, M.; Ullah, N.; Chinnam, S.; Ashique, S.; Mishra, N.; Wani, A.W.; Farid, A. Starch-based bio-membrane for water purification, biomedical waste, and environmental remediation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282 Pt 4, 137033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, R.; Heidari, A.A.; Mahdavi, H. Core-shell antibacterial conjugated nanostarch incorporated PVDF membrane for fast and efficient dye separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhang, G.; Shen, S.; Liu, D.; Zhou, X.; Hong, Y. Improving multifunctional properties of the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane with crosslinked dialdehyde-starch (DAS) and polyethyleneimine (PEI) coating. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280 Pt 3, 136015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, H.M.; Othman, S.H.; Shapi, R.A.; Yunos, K.H.M. Starch/chitosan nanoparticles bionanocomposite membranes for methylene blue dye removal. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 335704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, N.M.; Ali, S.S.; Mohamed, G.G.; Omar, M.M.; Amin, S.K. Fabrication of composite ceramic polymeric membranes for agricultural wastewater treatment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, P.; Karadjova, I. Newly Designed Organic-Inorganic Nanocomposite Membrane for Simultaneous Cr and Mn Speciation in Waters. Gels 2025, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggakusuma, R.; Utama, G.L.; Sumiarsa, D.; Muslimah, P.A.D.; Asgar, A. Utilization of Cassava Starch–Glycerol Gel as a Sustainable Material to Decrease Metal Ion Surface Contamination. Gels 2025, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanpour, V.; Bijari, M.; Sadiksoz, B.; Gul, B.Y.; Koyuncu, I. Starch as an eco-friendly and sustainable option for separation membranes: A review of current status and future directions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2026, 371, 124475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulson, B.G.; Alsulami, Q.A.; Sharfalddin, A.; El Agammy, E.F.; Mouffouk, F.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M. Cyclodextrins: Structural, Chemical, and Physical Properties, and Applications. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Shao, R.; Li, N.; Min, C.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Qian, X.; Wang, L. Progress of cyclodextrin based-membranes in water treatment: Special 3D bowl-like structure to achieve excellent separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dai, Y.; Liu, R.; Shi, Y.; Dai, G.; Xia, F.; Zhang, X. Facile synthesis of high-swelling cyclodextrin polymer for sustainable water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; He, Y.; Dai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, F.; Zhang, X. Cyclodextrin membranes prepared by interfacial polymerization for separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 152165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.L.; Gu, S.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Xu, Z. Cyclodextrin-Embedded Nanofilms With “Knot-Thread” Structure for Efficient Lithium Extraction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2506147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łagiewka, J.; Witt, K.; Gierszewska, M.; Zawierucha, I. Selective removal of organic dyes via polymer inclusion membrane containing a perbenzylated β-cyclodextrin derivative. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Yang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Bi, Q.; Zhong, J.; Matsuyama, H. Quaternary ammonium-functionalized γ-cyclodextrin tailored polyamide nanofiltration membranes for highly selective Li+/Mg2+ separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 377 Pt 1, 134161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Yu, H.; Qian, Y.; Zuo, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z.; et al. β-Cyclodextrin enabled ultrahigh-permeance loose nanofiltration membrane for efficient dye separation. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Fu, T.; Liu, G.; Shen, X.; Zhao, H. High-flux and stability nanofiltration membranes prepared with β-cyclodextrin and in-situ co-polymerized of TpPa COFs for dye desalination. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qin, W.; Wang, L.; Zhao, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Wei, J. Desalination of dye utilizing carboxylated TiO2/calcium alginate hydrogel nanofiltration membrane with high salt permeation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 253, 117475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Qi, M.; Bai, T.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X. Removal of Dyes and Cd2+ in Water by Kaolin/Calcium Alginate Filtration Membrane. Coatings 2019, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarczyk, C.; Fryczkowska, B. Structure–Property Relationships of Pure Cellulose and GO/CEL Membranes Regenerated from Ionic Liquid Solutions. Polymers 2019, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derami, H.G.; Jiang, Q.; Ghim, D.; Cao, S.; Chandar, Y.J.; Morrissey, J.J.; Jun, Y.-S.; Singamaneni, S. A Robust and Scalable Polydopamine/Bacterial Nanocellulose Hybrid Membrane for Efficient Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Nano Matter. 2019, 2, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhina, T.S.; Yushkin, A.A.; Makarov, I.S.; Ignatenko, V.Y.; Kostyuk, A.V.; Anotonov, S.V.; Volkov, A.V. Cellulose Composite Membranes for Nanofiltration of Aprotic Solvents. Pet. Chem. 2016, 56, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Lin, S.; Wei, X.; Guo, M.J. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals with different aspect ratios as nano-composite membrane for cationic dye removal. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, L.; Borjigin, B.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Hou, D. Fabrication of thin-film composite nanofiltration membranes with improved performance using β-cyclodextrin as monomer for efficient separation of dye/salt mixtures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 539, 148284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, E.; Khajavian, M.; Sahebjamee, N.; Mahmoudi, M.; Drioli, E.; Matsuura, T. Advances in nanocomposite and nanostructured chitosan membrane adsorbents for environmental remediation: A review. Desalination 2022, 527, 115565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, K.; Yuvaraj, K.M.; Kapoor, A. Chitosan-blended membranes for heavy metal removal from aqueous systems: A review of synthesis, separation mechanism, and performance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 134996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Merino, G.; Salinas-Hernández, J.A.; Manzano-Villanueva, R.P.; Perez, R.M.; Benítez-Zamudio, J.E.; San Román-Escudero, L.; Silva-González, N.R.; Méndez-Rojas, M.A.; Aguilar, N.M.; Salazar-Kuri, U. Chitosan-Fe3O4 Membranes for Biosorption of Cr(VI) in Water, and Study of its Degradation Using Entomopathogenic Fungi (Beauveria sp and Nomureae sp). Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane Type and Composition | Separated Substances | Main Advantages of Novel Membrane Materials | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaAlg-PVA-PVDF hydrogel composite nanofiltration (NF) membrane; sodium alginate and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)—the hydrogel coatings, porous polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)—matrix | Methylene blue, Congo red, Coomassie brilliant blue | High retention ratios of 91.4% for Methylene blue, 95.6% for Congo red, 97.7% for Coomassie brilliant blue. Promising potential of membrane in treating printing and dye-laden wastewater. | [12] |

| CMCS-OA-NaAlg hydrogel composite membrane; sodium alginate and carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS), non-metallic ions of oxalic acid (OA)—crosslinking agent | Right blue, Direct black, Direct red, Congo red, NaCl | The rejection higher than 95.0% for dyes and lower than 7.0% for NaCl. The membrane showed excellent anti-swelling and antifouling properties and performed well at high salt concentration. | [30] |

| OANaAlg/CMCS/TiO2@PTFE composite hydrogel membrane; CMCS, nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2), NaAlg aqueous solution (matrix), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) nanofiber membrane—the support layer, OA—the crosslinking agent | Direct Black, Coomassie Brilliant Blue, Direct Red, Congo Red, NaCl, Na2SO4, MgCl2, MgSO4 | High rejection rates: 99% for Direct Black, over 95% for all other separated dyes. Rejection rates below 10% for all inorganic salts. The membrane was characterized by very good mechanical properties (a tensile strength of 9.06 MPa), the embedded TiO2 could be recovered and reused. The membrane can be used for treating high-salinity wastewater under acidic conditions. | [31] |

| CuCaAlg/TiO2 hydrogel membranes; TiO2 nanoparticles, alginate polymer network, Ca2+/Cu2+—dual crosslinking agents | Coomassie brilliant blue, Direct black, Methyl orange, Congo red, Direct red, NaCl | The membrane exhibited excellent dye/salt selective separation performance (for Coomassie brilliant blue removal exceeded 99%, salt removal below 5%) and demonstrated excellent hydrophilicity, swelling resistance, and antifouling properties. Possibility of using a simple cleaning strategy (UV-H2O2-cross flow filtration) for rapid in situ cleaning of membrane in high-concentration dye solution. | [32] |

| P-MT@NaAlg-PVA-PVDF hydrogel nanofiltration (NF) membrane; multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and TiO2 (P-MT)—coatings, NaAlg, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), PVDF—matrix | Coomassie brilliant blue, Congo red, Methylene blue | High rejection rates: Coomassie brilliant blue—96.3%, Congo red—95.5%, Methylene blue—92.1%. Membrane displayed hydrophilicity and antifouling properties. It has great potential in the field of printing and dyeing wastewater treatment. | [33] |

| NaAlg/PEG/CNF/MWCNT-COOH hydrogel loose nanofiltration (LNF) membrane; NaAlg—matrix, large molecular weight PEG—pore-making agent, cellulose nanofibers (CNF) and carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT-COOH)—additives | Crystal violet, Congo red, Tartrazine, Methylene blue, MgSO4, Na2SO4, MgCl2, NaCl | High rejection rates: Crystal violet—99.8%, Congo red—98.9%, Tartrazine—93.1%, Methylene blue—85.7%, low retention of salts (in the range of 7.3% to 11.6%). The membrane exhibited high separation efficiency towards the mixed dye/salt solution, showed excellent hydrophilicity and stain resistance, had good recycling effect | [34] |

| GO-CaAlg hybrid hydrogel membrane; graphene oxide (GO), calcium alginate hydrogel, Ca2+ ions—crosslinking agent | Coomassie brilliant blue, NaCl | Rejection rates: Coomassie brilliant blue—99%, NaCl—8%. The membrane maintained a good separation efficiency after 45 days of process, has shown superior antifouling performance, was characterized by antimicrobial properties (towards E. coli). | [35] |

| Car/CaAlg-NWF hydrogel composite filtration membrane; carrageenan (Car), calcium alginate, polyester NWF (nonwoven fabric) | Methylene blue | λ-Car/CaAlg-NWF exhibited superior dye rejection (100%). The hydrogel membranes were recyclable over nine cycles and have potential for water treatment applications. | [36] |

| NaAlg/CNF/UiO-66 dual-network composite hydrogel membrane; metal–organic frame UiO-66, sodium alginate, cellulose nanofibers (CNF) | Congo red Pb2+, Cu2+, Cd2+ | Removal rates for Pb2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ ions were 99.9%, 98.5%, and 96.5%, respectively. Removal rate for high concentration Congo red reached >99.8%. The membrane showed excellent reusability (high removal rates after ten consecutive filtration/elution cycles) and mechanical properties (resistant to deformation, the fracture stress exceeded 6 MPa), and may be, potentially useful in solving the problem of water resources pollution. | [37] |

| BCFS800/NaAlg composite hydrogel membrane; ball-milled crayfish shell biochar (BCFS800), sodium alginate, Ca2+ crosslinking agent | Congo red, NaCl | The membrane exhibited higher dye removal selectivity and lower inorganic salt ion rejection compared to the control membrane without biochar doping (149.2 vs. 34.3, and 4.54% vs. 7.56%, respectively), demonstrating exceptional dye/salt separation capability. | [38] |

| NaAlg/PVA hydrogel membrane; sodium alginate and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | Toluidine blue | The membrane (whose structure—pore size, quantity, and diameter distribution—depended on the number of freeze–thawing cycles used) showed significant potential for removing Toluidine blue dye from aqueous solutions with maximum adsorption capacity of 74.1 mg/g (Langmuir isotherm model). | [39] |

| Membrane Type and Composition | Separated Substances | Main Advantages of Novel Membrane Material | Reference/ Year of Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNC-GLU TFN thin film nanocomposite membranes; cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) dispersed within a polyamide (PA) film, glutamic acid—modifier, polysulfone (PSF) | Methylene blue, Methyl orange, MgSO4, NaCl | CNC-GLU TFN membranes showed high dye rejection (99.83% for Methylene blue, 90.63% for Methyl orange) and salt removal (MgSO4 = 86%; NaCl = 38%). They demonstrated good operational stability after six cycles. | [56] |

| BiOCl/CNF/Mxene composite membrane; BiOCl, Mxene, cellulose nanofibers (CNF) | Congo red, Methyl blue, Rhodamine B, Crystal violet | Membrane showed excellent rejection for dyes (98.9% for Congo red, 97.2% for Methyl blue, 99.6% for Rhodamine B, 99.7% for Crystal violet), exhibited good stability and robust antifouling performance across different pH conditions. | [57] |

| PAF@BC multifunctional composite membrane; hydrophilic bacterial cellulose (BC), porous aromatic framework (PAF-45) | Anionic and cationic dyes, Iodide ions, | PAF@BC exhibited high efficiency and stability in intercepting both anionic and cationic dyes and iodide ions from aqueous solutions. The captured pollutants were effectively degraded. It also efficiently separated iodine vapor (96%). The membrane shows significant potential in environmental remediation and open new possibilities for the versatile application of composite membranes. | [58] |

| CA-NF-2/0.4 nanofiltration membranes; cellulose acetate (CA), polyamide (PA), diethylenetriamine (DETA), 1,3,5-benzenetricarbonyl chloride (TMC) | Rose Bengal, Congo red, Methyl orange, Methylene blue, MgCl2, Na2SO4, MgSO4, NaCl, | CA-NF-2/0.4 exhibited high removal efficiencies for dyes (99% for Rose Bengal and Congo red, 95.5% for Methyl orange, 96.1% for Methylene blue), and salts (MgCl2—84.2%, Na2SO4—92.7%, MgSO4—91.8%, NaCl—54.1%). Membranes demonstrated excellent antifouling properties (permeation recovery ratio >98% after three cycles of filtration), long-term durability, and stability (10 days) under high operational pressures and salt concentrations. | [59] |

| GC-CAMs gradient-charged membrane; cellulose acetate, ionic covalent organic framework nanosheets (iCOFNs), GC-gradient charged | Na2SO4, total dissolved solids, | GC-CAM achieved Na2SO4 rejection of about 95%, when applied to natural water purification, it reduced total dissolved solids to 83% while moderately removing heavy metal ions. The proposed gradient structure offers a novel approach for the charge engineering of nanofiltration membranes. | [60] |

| CA@TiO2 reverse osmosis composite membrane; CA, TiO2 nanoparticles, dimethylformamide (DMF)—solvent | Methylene blue, Ca2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Cr3+, Fe3+, | The membrane showed over 60% of Ca2+and Mg2+ ions rejection, removed 90–97% of heavy metals ions, achieved about 85% oil/water separation efficiency and degraded 89.6% of Methylene blue under UV light in 90 min, showing good photocatalytic activity. The membrane offers promising potential for sustainable water purification and wastewater treatment. | [61] |

| MIL-125/CCNFs/PVDF multifunctional membrane; Ti-based MOF derived from Ti metal ions and carboxylate organic ligands (MIL-125), carboxylated cellulose nanofibers (CCNFs), PVDF | Crystal violet, Methylene blue, Malachite green, | MIL-125/CCNFs/PVDF exhibited excellent dye rejection (>97% for all dyes), strong self-cleaning ability, and antifouling stability. Developed separation method can be treated as a green and efficient strategy for next-generation water treatment. | [62] |

| EGO-DACNC-AgNPs composite membranes; ethylenediamine (EDA) and GO (EGO), silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), dialdehyde cellulose nanocrystal (DACNC) | Methylene blue, Crystal violet, Congo red | The membrane allowed for effective dye separation, had good mechanical stability, a long service life, strong antifouling properties. The degradation rate of Methylene blue (under visible light irradiation) reached 94% within 5 h, and the inhibition rate of E. coli reached 95%. Separation based on this type of membrane can potentially solve problems of membrane pollution and environmental protection in dye wastewater treatment. | [63] |

| Series of fully biobased membranes fabricated from pristine (P) and functionalized (T) cellulose nanofibers (CNF); T-CD-CNF-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO), carbon dots (CDs), cellulose nanofiber (CNF), other membranes: T-CNF, P-CNF, CD-CNF | Protein (bovine serum albumin), Cu2+, Fe+3, Methylene blue | T-CD-CNF and T-CNF membranes have high filtration efficiency for heavy metals, dyes and protein from model solutions (e.g., for Methylene blue about 95% and 80%, respectively), in and garment industry wastewater (for MB about 20% and 25%, respectively). Such biobased composite membranes can be reused (in 5 cycles), which may have influence on the circular economy. | [64] |

| AA–IL-CA membranes; cellulose acetate, amino acids (AAs), 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid (IL) | Fe+3, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, | The membrane enabled high rejection rates for copper, zinc, iron, and lead ions present in the industrial effluent (89%, 91%, 84%, and 90%, respectively). The use of CA, AAs, and IL aligns with sustainability goals; the cost-effectiveness, availability of materials, and the simplicity of the fabrication process suggest that the membrane fabrication process can be scaled up for large-scale industrial applications. | [65] |

| CTA/PVDF-HFP/TOA/TBP a blend polymer inclusion membrane (BPIM); cellulose triacetate (CTA), poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoro propylene) (PVDF-HFP), tri-n-octylamine (TOA, extractant) and tri-n-butylphosphate (TBP, plasticizer) | Bi(III) in the presence of various metal ions, including Cu(II), Fe(III), Cr(III) Co(II), Zn(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Ni(II), Cd(II) | The BPIM exhibited selective extraction of Bi(III) (removal of 97%), in the presence of various metal ions, and was reusable (efficient in four consecutive cycles) BPIM is suitable for the efficient recovery of bismuth ions from zinc production plants residue. | [66] |

| CTA/AKL/D2EHPA polymer inclusion membranes; CTA, acetylated kraft lignin (AKL), di(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) | Ni2+ | The membranes were highly efficient in the recovery of Ni(II) ions (about 65% under optimized conditions). | [67] |

| Membrane Composition/ Reference | Rejection/ Separated Substances | Selected Membrane Process Parameters | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2-COOH/CaAlg; carboxylated titanium dioxide and calcium alginate hydrogel nanofiltration membrane [112] | 98.4% for Brilliant blue G250, 96.8% for Direct black, 38. 95.9% for Congo red | The permeate flux was about 14.1 L/m2⋅h | The membrane was characterized by low rejection ratios for inorganic salts (16.1%, 15.6%, 12.3% and 9.0% for MgSO4, Na2SO4, MgCl2 and NaCl, respectively). |

| Kaolin/CaAlg; kaolin, sodium alginate, Ca2+ (crosslinking agent), urea (porogen agent) [113] | 100% for Brilliant blue G250, 95.2% for Congo red, 62.8% for Methylene blue, 99.7% for Cd2+ | The permeate flux was 17.06 L/m2·h at 0.1 MPa. | Kaolin significantly improved the mechanical behavior of the membrane (with the 70% content of kaolin in NaAlg, the stress of the kaolin/CaAlg membrane reached 963.95 KP and was three times higher than in the case of CaAlg membrane). |

| GO/CEL; graphene oxide/cellulose, various coagulants [114] | 100% for Co2+ 98–100% for Zn2+, 97–99% for Ni2+ | The permeate flux was 50 L/m2⋅h, | The physicochemical properties of the coagulant used (e.g., molecular mass, dipole moment) had a large influence on the volume content of the membrane pores. In the case of 1-octanol GO/CEL membrane—volume fraction of pores was 1.82% |

| PDA/BNC; polydopamine (PDA) particles and bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) [115] | >98% in the case of Pb2+, Cd2+, Methyl orange, Methylene blue, Rhodamine 6G | - | The regenerated membranes exhibited excellent contaminant removal efficiency after 10 cycles of filtration (about 90%). The pore size of PDA/BNC was about 10 nm |

| Cellophane; cellulose solution in N-methyl- morpholine oxide, nonwoven polyester support [116] | 15–85% for Orange II, 42–94% for Remazol Brilliant Blue R | Permeability depended on the solvent used (e.g., it changed from about 0.11 to about 2.5 kg/m2 h⋅bar, in the order: DMSO > NMP > DMFA > THF > acetone | Cellophane was stable in aprotic solvents, solvents interacted with the membrane material differently—a lower degree of cellulose swelling has been observed in THF (37%) and a higher degree has been noted in DMSO (230%). The rejection of solutes by the composite membranes correlated with the degree of cellulose swelling. |

| Nano-composite membranes CNCs, cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) with different properties derived from raw microcrystalline cellulose [117] | 99.9% for Methylene blue, 97.9% for Rhodamine B | The lowest permeate flux was about 12 L/m2⋅h | The permeation flux of the membranes depended on CNC concentration. |

| β -CD/TMC membranes, β -cyclodextrin and trimesoyl chloride (TMC) [118] | 100.0% for Congo red, 99.1% for Rose bengal | A pure water flux of 207.8 L/m2⋅h at 2.0 bar | The membrane performance (e.g., permeate flux, efficiency) depended on β-CD and NaOH (aqueous additive) concentration. The rejection of NaCl was below 10.6%. The membrane showed desirable stability; the flux remained at 82.9% of the initial value after filtration for 16 h. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaczorowska, M.A. Novel Alginate-, Cellulose- and Starch-Based Membrane Materials for the Separation of Synthetic Dyes and Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions and Suspensions—A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 5495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245495

Kaczorowska MA. Novel Alginate-, Cellulose- and Starch-Based Membrane Materials for the Separation of Synthetic Dyes and Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions and Suspensions—A Review. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245495

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaczorowska, Małgorzata A. 2025. "Novel Alginate-, Cellulose- and Starch-Based Membrane Materials for the Separation of Synthetic Dyes and Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions and Suspensions—A Review" Materials 18, no. 24: 5495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245495

APA StyleKaczorowska, M. A. (2025). Novel Alginate-, Cellulose- and Starch-Based Membrane Materials for the Separation of Synthetic Dyes and Metal Ions from Aqueous Solutions and Suspensions—A Review. Materials, 18(24), 5495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245495