Numerical and Experimental Correlation Between Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss in Corroded Reinforced Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Simulation

2.1. Principle Behind the Simulation

2.2. Model Geometry and Input Parameters

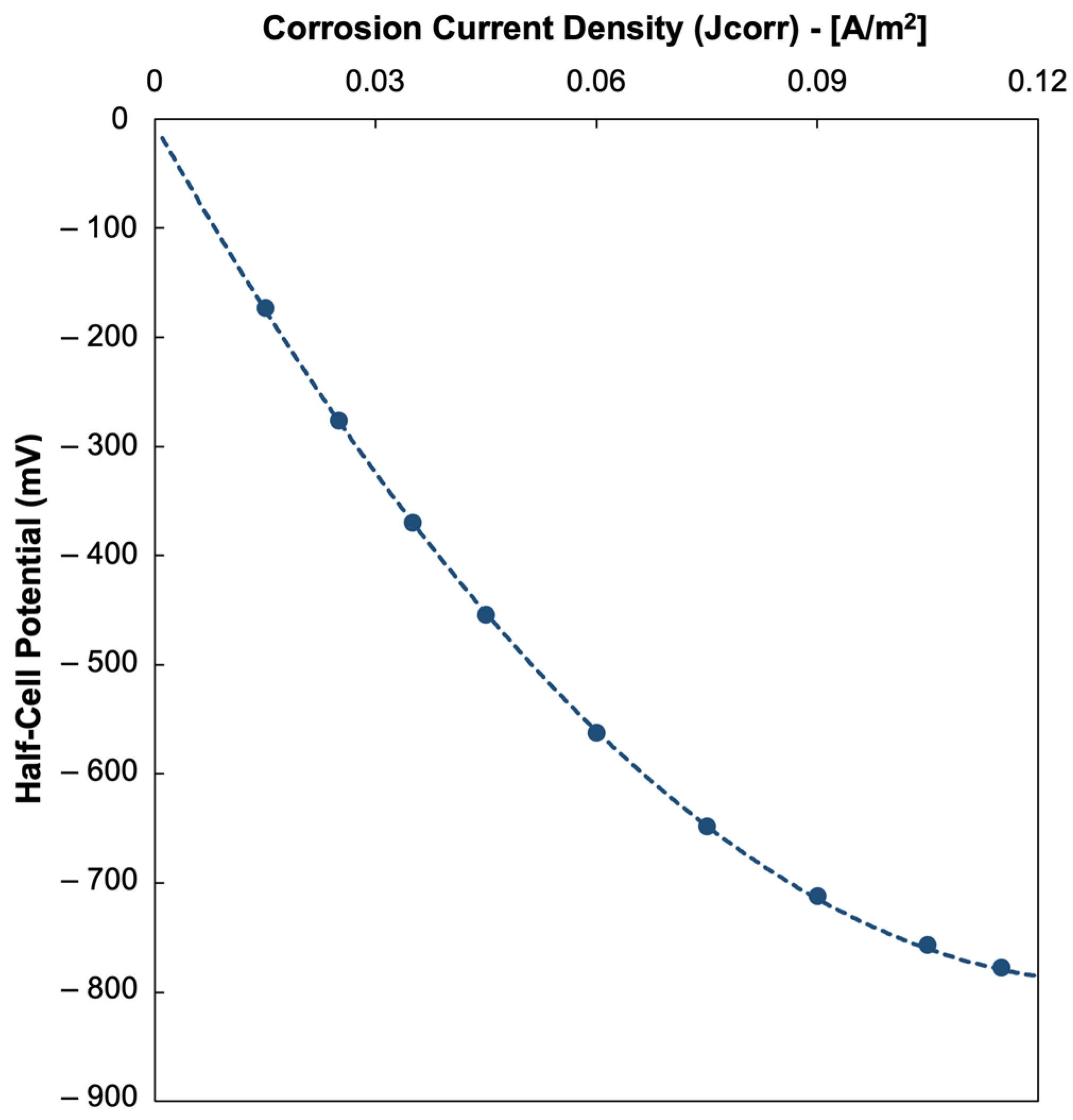

2.3. Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss

3. Experimental Study

3.1. Preparation of Specimens

3.2. Accelerated Corrosion and Actual Steel Mass Loss

3.3. Half-Cell Potential Measurements

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Distribution of Electrical Potential in Reinforced Concrete

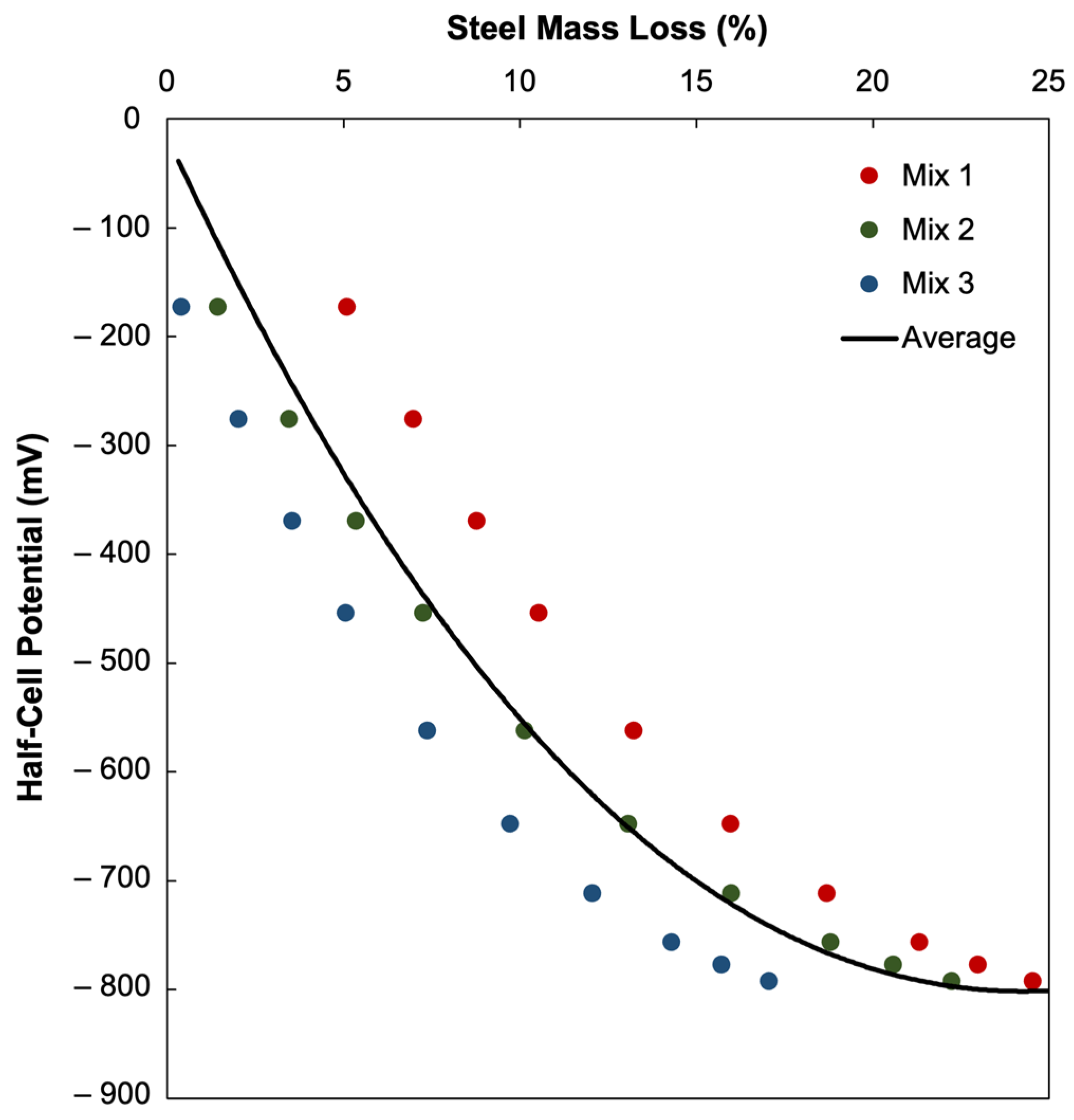

4.2. Relationship Between Half-Cell Potential of Concrete and Steel Mass Loss

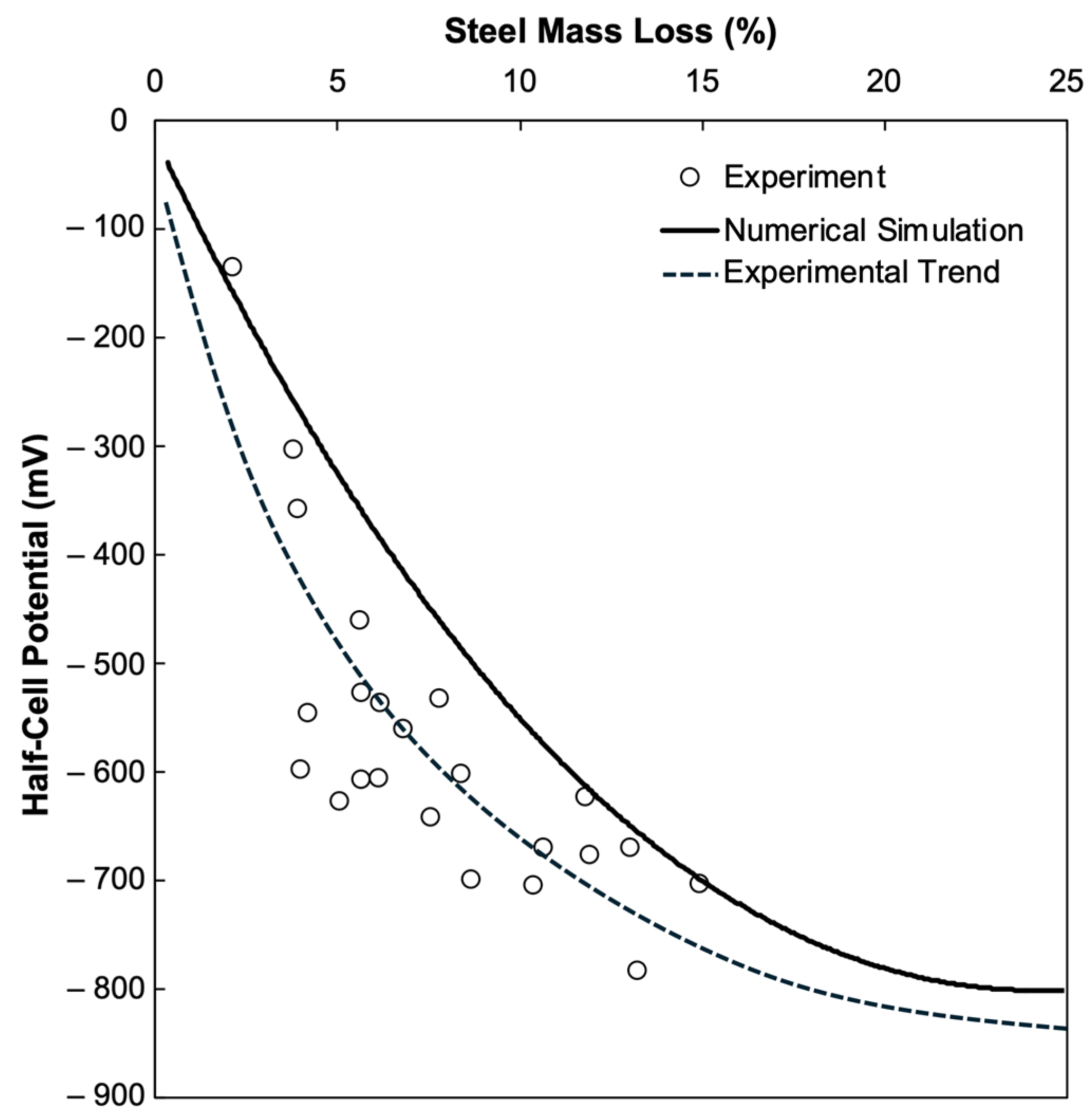

4.3. Validation of Results Through Experimental Investigation

4.4. Practical Applications and Future Recommendations

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A clear and strong polynomial relationship was observed between corrosion current density, electrical resistivity, and HCP values, confirming that electrochemical response can be accurately represented through numerical modeling. This study demonstrated an excellent correlation between simulated HCP values and measured steel mass loss, indicating that HCP can be used as a quantitative indicator of corrosion severity when properly calibrated.

- The correlation between half-cell potential and steel mass loss was best described by a second-order polynomial, , with R2 = 0.9999.

- HCP measurements obtained at the center of the concrete surface using a PROCEQ Profometer closely matched the numerical predictions, validating the applicability of the model despite minor variability in intermediate corrosion levels.

- A preliminary HCP–mass loss classification was developed, providing threshold ranges that can support condition-based maintenance strategies and corrosion monitoring in reinforced concrete structures. Future studies should incorporate variables such as concrete cover thickness, rebar diameter, moisture saturation, and crack conditions, supported by a larger and more diverse experimental dataset, to further refine and generalize the predictive framework.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valipour, M.; Yekkalar, M.; Shekarchi, M.; Panahi, S. Environmental Assessment of Green Concrete Containing Natural Zeolite on the Global Warming Index in Marine Environments. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubba, S. Green Building Materials and Products. In Handbook of Green Building Design and Construction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 257–351. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Qu, S.; Tian, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Recent Progress on Graphene Oxide for Next-Generation Concrete: Characterizations, Applications and Challenges. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 69, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhti, J.A.; Robles, K.P.V.; Lee, K.-H.; Kee, S.-H.; Mukhti, J.A.; Paolo, K.; Robles, V.; Lee, K.-H.; Kee, S.-H. Evaluation of Early Concrete Damage Caused by Chloride-Induced Steel Corrosion Using a Deep Learning Approach Based on RNN for Ultrasonic Pulse Waves. Materials 2023, 16, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Evaluation of Steel Corrosion-Induced Concrete Damage Using Electrical Resistivity Measurements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Evaluation of Ecological Environmental Pollution in Green Building Construction. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, L. Prediction of Corrosion-Induced Cracking of Concrete Cover: A Critical Review for Thick-Walled Cylinder Models. Ocean Eng. 2020, 213, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-W.; Saraswathy, V. Corrosion Monitoring of Reinforced Concrete Structures—A Review. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2007, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsudjai, W.; Pattarakittam, T. Factors Influencing Half-Cell Potential Measurement and Its Relationship with Corrosion Level. Measurement 2017, 104, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelalerkiet, V.; Kyung, J.-W.; Ohtsu, M.; Yokota, M. Analysis of Half-Cell Potential Measurement for Corrosion of Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.G.; Kahraman, R.; Alnuaimi, N.A.; Gencturk, B.; Alnahhal, W.; Dawood, M.; Belarbi, A. Electrochemical Behavior of Mild and Corrosion Resistant Concrete Reinforcing Steels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Li, X.; Ma, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Xu, W.; Lu, D.; Ma, F. The Cost of Corrosion in China. npj Mater. Degrad. 2017, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.C.; Ross, R.A.; Davis, G.D. Corrosion Monitoring of Steel Reinforced Concrete Structures Using Embedded Instrumentation. In Proceedings of the NACE–International Corrosion Conference Series, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–18 March 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, G. Cost of Corrosion. In Trends in Oil and Gas Corrosion Research and Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Papavinasam, S.; Rebak, R.B.; Yang, L.; Berke, N.S. Front Matter. In Advances in Electrochemical Techniques for Corrosion Monitoring and Laboratory Corrosion Measurements; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019; pp. FM1–FM12. [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the Global Cost of Corrosion. Available online: http://impact.nace.org/economic-impact.aspx (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Burkert, A.; Ebell, G.; Eichler, T.; Hariri, K.; Harnisch, J.; Keßler, S.; Mayer, T.; Meier, J.; Mietz, J.; Reichling, K.; et al. Electrochemical Half-Cell Potential Measurements for the Detection of Reinforcement Corrosion; German Society for Non-Destructive Testing (DGZfP): Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Shams, M.A.; Bheel, N.; Almaliki, A.H.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Dodo, Y.A.; Benjeddou, O. A Review on Chloride Induced Corrosion in Reinforced Concrete Structures: Lab and In Situ Investigation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 37252–37271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagüés, A.A.; Sánchez, A.N.; Lau, K.; Kranc, S.C. Service Life Forecasting for Reinforced Concrete Incorporating Potential-Dependent Chloride Threshold. Corrosion 2014, 70, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hover, K.C. The Influence of Water on the Performance of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3003–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouli, B.; Ballivy, G.; Rivard, P. Influence of Environmental Parameters on Application of Standard ASTM C876-91: Half Cell Potential Measurements. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, J.; Bennett, J.; Turk, T.; Hartt, W.H.; Lankard, D.R.; Sagues, A.A.; Savinell, R. Control Criteria and Materials Performance Studies for Cathodic Protection of Reinforced Concrete; Strategic Highway Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, S.; Gehlen, C. Influence of Concrete Moisture Condition on Half-Cell Potential Measurement. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the Durability of Concrete Structures, Shenzhen, China, 30 June–1 July 2016; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Baji, H.; Li, C.Q. A Comparative Study on Factors Affecting Time to Cover Cracking as a Service Life Indicator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Beushausen, H. Durability, Service Life Prediction, and Modelling for Reinforced Concrete Structures—Review and Critique. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, S.R.; van Zijl, G.P.A.G. Corrosion Propagation in Cracked Reinforced Concrete, toward Determining Residual Service Life. Struct. Concr. 2019, 20, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchige, L.J.; Li, C.; Wang, F. Recent Advances in Understanding Iron/Steel Corrosion: Mechanistic Insights from Molecular Simulations. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2025, 35, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.; Yee, J.J.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Hybrid Data-Driven Machine Learning Approach for Evaluating Steel Corrosion in Concrete Using Electrical Resistivity and Documented Concrete Performance Indicators. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Techniques for Inducing Accelerated Corrosion of Steel in Concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2009, 34, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Pilvar, A.; Mahdikhani, M.; Moodi, F. Practical Evaluation of Relationship between Concrete Resistivity, Water Penetration, Rapid Chloride Penetration and Compressive Strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormellese, M.; Berra, M.; Bolzoni, F.; Pastore, T. Corrosion Inhibitors for Chlorides Induced Corrosion in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, U.M. Challenges and Opportunities in Corrosion of Steel in Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2018, 51, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsener, B.; Rossi, A. Passivation of Steel and Stainless Steel in Alkaline Media Simulating Concrete. In Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Z. Basic Concepts in Corrosion. In Principles of Corrosion Engineering and Corrosion Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 9–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, K.; He, Z.; Yi, B.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Study on Electrochemical Characteristics of Reinforced Concrete Corrosion under the Action of Carbonation and Chloride. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xie, N.; Fortune, K.; Gong, J. Durability of Steel Reinforced Concrete in Chloride Environments: An Overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, L. Methodology for Assessing the Probability of Corrosion in Concrete Structures on the Basis of Half-Cell Potential and Concrete Resistivity Measurements. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 714501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, D.W.; Cairns, J.H. Evaluation of Corrosion Loss of Steel Reinforcing Bars in Concrete Using Linear Polarisation Resistance Measurements. Available online: https://www.ndt.net/article/ndtce03/papers/p015/p015.htm (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Moreno, M.; Morris, W.; Alvarez, M.G.; Duffó, G.S. Corrosion of Reinforcing Steel in Simulated Concrete Pore Solutions Effect of Carbonation and Chloride Content. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 2681–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Mendoza, J.; Flores, J.M.; Castillo, U.C. Effect of Superficial Oxides on Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement Embedded in Concrete. Corrosion 1994, 50, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, B.; L’Hostis, V.; Miserque, F.; Idrissi, H. Electrochemical Behavior of Mild Steel in Concrete: Influence of PH and Carbonate Content of Concrete Pore Solution. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 51, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.A.; Andrade, C. Eftect of Carbonation, Chlorides and Relative Ambient Humidity on the Corrosion of Galvanized Rebarsembedded in Concrete. Br. Corros. J. 1982, 17, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Chung, D.D.L. Effect of Admixtures in Concrete on the Corrosion Resistance of Steel Reinforced Concrete. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Kee, S.H. Electrical Resistivity Measurements for Nondestructive Evaluation of Chloride-Induced Deterioration of Reinforced Concrete—A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.; Kee, S.-H. An Electrical Resistivity Measurement Approach in the Determination of the Degree of Water Saturation of Reinforced Concrete by Machine Learning Methods. J. Acad. Present. Conf. Archit. Inst. Korea 2022, 42, 595–596. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, C.B.; Vartika; Dwivedi, S.K.; Raja, M.; Vidyarthi, U.S. Evaluation of the Corrosion Activity of Reinforcement in Drainage Gallery of Concrete Dam Using Half-Cell Potential (HCP). Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carufel, S. Half-Cell Potential Test: Measurement and Devices. 2023. Available online: https://www.giatecscientific.com/education/what-is-the-half-cell-potential-test/ (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Torres-Acosta, A.A. Technical Note: Considerations to Avoid Corrosion Rate Estimate Error of the Reinforcing Steel If Based Only on Concrete’s Electrical Resistivity. Corrosion 2024, 80, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, P.-G.; Isgor, O.B.; Pouria, G. Quantitative Interpretation of Half-Cell Potential Measurements in Concrete Structures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2009, 21, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C876-15; Standard Test Method for Corrosion Potentials of Uncoated Reinforcing Steel in Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Capasso, M.; Carusi, V.; Forte, A.; Lavorato, D.; Raoli, G.; Santini, S. A Probabilistic Interpretation of Corrosion State through Half-Cell Potential and Electrical Resistivity Measures: The Flaminio Bridge in Rome. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfändler, P.; Keßler, S.; Huber, M.; Angst, U. Spatial Variability of Half-Cell Potential Data from a Reinforced Concrete Structure—A Geostatistical Analysis. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 20, 1698–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoba, B.; Ajah, U.C.; Kennedy, C. Utilizing Electrochemical Techniques for Assessing the Probability of Concrete Resistivity and Corrosion Potential in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Middle East Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2024, 4, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golam, M.A. Reference Half Cells for Monitoring Corrosion Condition of Steel in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 1990, 37, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsener, B. Macrocell Corrosion of Steel in Concrete—Implications for Corrosion Monitoring. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2002, 24, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, R.B. Test Methods for on Site Measurement of Resistivity of Concrete—A RILEM TC-154 Technical Recommendation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2001, 15, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriman, R.; Ibrahim, I.B.M.; Huzni, S.; Fonna, S.; Ariffin, A.K. Improving Half-Cell Potential Survey through Computational Inverse Analysis for Quantitative Corrosion Profiling. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.B.; Park, K.T.; Kwon, S.J. Evaluation of Half Cell Potential Measurement in Cracked Concrete Exposed to Salt Spraying Test. J. Korea Concr. Inst. 2013, 25, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abouhussien, A.A.; Hassan, A.A.A. Acoustic Emission Monitoring of Corrosion Damage Propagation in Large-Scale Reinforced Concrete Beams. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2018, 32, 04017133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frølund, T.; Klinghoffer, O.; Sørensen, H.E. Pro’s and Con’s of Half-Cell Potentials and Corrosion Rate Measurements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Structural Faults + Repairs, London, UK, 1 July 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Almashakbeh, Y.; Saleh, E.; Al-Akhras, N.M. Evaluation of Half-Cell Potential Measurements for Reinforced Concrete Corrosion. Coatings 2022, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipek, R.; Szyszkiewicz-Warzecha, K.; Szczudło, J. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete—Modeling of Electrochemical Potential Measurement in 3D Geometry. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2020, 65, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comsol Multiphysics COMSOL AC/DC Module User’s Guide. 2018. Available online: https://doc.comsol.com/5.4/doc/com.comsol.help.acdc/ACDCModuleUsersGuide.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Shevtsov, D.S.; Zartsyn, I.D.; Komarova, E.S. Relation between Resistivity of Concrete and Corrosion Rate of Reinforcing Bars Caused by Galvanic Cells in the Presence of Chloride. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Kim, D.-W.; Kee, S.-H.; Yee, J.-J.; Paolo, K.; Robles, V.; Kim, D.-W.; Yee, J.-J.; Lee, J.-W.; Kee, S.-H.; et al. Electrical Resistivity Measurements of Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Delamination Defects. Sensors 2020, 20, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Calibrating Electrical Resistivity Measurements in Reinforced Concrete with Rebar Effects and Practical Guidelines. Measurement 2025, 244, 116542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, C.G.; Balaguru, P.N.; Auyeung, Y. Influence of FRP Confinement on Bond Behavior of Corroded Steel Reinforcement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, Q.; Wang, R.; Wu, M.; Jiang, Z. Corrosion Assessment of Reinforced Concrete Structures Exposed to Chloride Environments in Underground Tunnels: Theoretical Insights and Practical Data Interpretations. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 112, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Relationship between Half-Cell Potential and Corrosion Level of Rebar in Concrete. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakrashi, V.; Kelly, J.; O’Connor, A. Direct and Probabilistic Interrelationships between Half-Cell Potential and Resistivity Test Results for Durability Ranking. In Bridge Maintenance, Safety, Management, Resilience and Sustainability: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Bridge Maintenance, Safety and Management, Stresa, Italy, 8–12 July 2012; Biondini, F., Frangopol, D.M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 2190–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-L.; Kind, T.; Stoppel, M.; Wiggenhauser, H. Measurement of Accelerated Steel Corrosion in Concrete Using Ground-Penetrating Radar and a Modified Half-Cell Potential Method. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2013, 19, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Yu, T. Accelerated Artificial Corrosion Monitoring of Reinforced Concrete Slabs Using the Half-Cell Potential Method. In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems, Denver, CO, USA, 17–21 March 2013; Environment and Engineering Geophysical Society: Denver, CO, USA, 2013; pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.B.; Park, K.-T.; Kwon, S.-J. Variation of Half Cell Potential Measurement in Concrete with Different Properties and Anti-Corrosive Condition. J. Korea Inst. Struct. Maint. Insp. 2013, 17, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giri, S. The Study of Half-Cell Potential Behaviour of Reinforced Concrete in Marine Environment. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbela, G.; Moyo, P.; Alexander, M. Influence of Corrosion Crack Patterns on the Rate of Crack Widening of RC Beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2540–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.; Kee, S.-H. Experimental Investigation on the Influence of Degree of Saturation to the Effect of Steel Reinforcements to the Electrical Resistivity of Reinforced Concrete. J. Acad. Conf. Korean Concr. Inst. 2022, 34, 391–392. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Kee, S.H. Simulation-Based Assessment of the Impact of Internal and Surface-Breaking Cracks on Reinforced Concrete Electrical Resistivity. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Civil Engineering and Architecture, Da Nang, Vietnam, 7–9 December 2024; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banar, R.; Moodi, F.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Ramezanianpour, A.M.; Dashti, P. Experimental and Numerical Simulation of Carbonation-Induced Corrosion in Reinforced Concretes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Probability of Steel Corrosion | Half-Cell Potential for Cu/CuSO4 Electrode (Ecorr) [mV] |

|---|---|

| Low (<10%) | Ecorr > −200 |

| Intermediate | −200 < Ecorr < −350 |

| High (>90%) | Ecorr < −350 |

| J(corr)—[A/m2] | σ—[S/m] |

|---|---|

| 0.015 | 0.003554997 |

| 0.025 | 0.003717581 |

| 0.035 | 0.003886186 |

| 0.045 | 0.004068853 |

| 0.06 | 0.004382456 |

| 0.075 | 0.004755785 |

| 0.09 | 0.005196077 |

| 0.105 | 0.005704476 |

| 0.115 | 0.006079472 |

| 0.125 | 0.006480828 |

| Properties | Mix 1 (kg/m3) | Mix 2 (kg/m3) | Mix 3 (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 168 | 170 | 166 |

| Portland Cement Type I | 287 | 335 | 480 |

| Gravel Sand High-Performance Air-Entraining Agent | 898 957 2.58 | 956 870 2.5 | 993 720 4.32 |

| Concrete Mix | Regression | R2 Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mix 1 | R2 = 0.8078 | |

| Mix 2 | R2 = 0.9781 | |

| Mix 3 | R2 = 0.9971 |

| Properties | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Water | 168 kg/m3 |

| Portland Cement Type I | 287 kg/m3 |

| Gravel | 898 kg/m3 |

| Sand | 957 kg/m3 |

| High-Performance Air-Entraining Agent | 2.58 kg/m3 |

| Design Strength | 18 MPa |

| W/c Ratio | 0.585 |

| HCP | mL | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ≤−200 mV | ~0–2% | Light corrosion |

| −200 mV < x < −500 mV | ~2–7% | Moderate corrosion |

| ≥−500 mV | ~7–16% | Severe corrosion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.L.L.; Kee, S.-H.; Monjardin, C.E.F.; Robles, K.P.V. Numerical and Experimental Correlation Between Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss in Corroded Reinforced Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 5238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225238

Li MLL, Kee S-H, Monjardin CEF, Robles KPV. Numerical and Experimental Correlation Between Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss in Corroded Reinforced Concrete. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225238

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Max Lawrence L., Seong-Hoon Kee, Cris Edward F. Monjardin, and Kevin Paolo V. Robles. 2025. "Numerical and Experimental Correlation Between Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss in Corroded Reinforced Concrete" Materials 18, no. 22: 5238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225238

APA StyleLi, M. L. L., Kee, S.-H., Monjardin, C. E. F., & Robles, K. P. V. (2025). Numerical and Experimental Correlation Between Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss in Corroded Reinforced Concrete. Materials, 18(22), 5238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225238