Abstract

Effective scheduling and charging management of electric buses is essential for minimizing investment and operational costs while improving transit efficiency. The paper presents an optimization framework which provides a 3D Pareto frontier of fleet size, deadhead distance, and charging cost, while accounting for heterogeneous battery energy, charger power, charging spot capacities, integrated daily and night charging, and a charge sustaining condition. Two optimization approaches are developed: Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which finds globally optimal solutions, and an Insertion Heuristic (IH), which generates feasible schedules in a computationally efficient way. The framework operates iteratively, starting with MILP to determine the minimum number of buses for feasible operation. Then, additional buses are incrementally incorporated, and for each fixed fleet size, a multi-objective optimization of scheduling and charging management is applied to minimize deadhead distance and charging costs using both approaches. A case study on a synthetic transport network demonstrates that the proposed IH algorithm achieves nearly optimal performance at a fraction of the computational time and memory requirements of the MILP approach. A Pareto analysis shows that increasing fleet size reduces deadhead distance and charging costs up to a saturation point, beyond which further additions yield minimal benefits.

1. Introduction

The ongoing shift toward electromobility is transforming urban public transportation systems, with electric city buses (EBs) emerging as a sustainable alternative to conventional diesel engine-powered buses [1]. EBs provide significant environmental advantages, including reduced greenhouse gas and noise emissions and zero local pollution, as well as lower operational costs [2]. The city bus transport system is a natural candidate for electrification due to the predetermined and relatively short routes allowing for exploiting fast charging (e.g., at end stations) for reduced battery capacity, mass, and cost [3]. However, typical tasks in establishing a city bus fleet, such as line planning, vehicle scheduling [4], timetabling [5], and crew scheduling [6], become more complex in the case of EBs, as they should be integrated with charging management.

A primary limitation of EBs is their restricted driving range (typically 100–300 km per charge), necessitating recharging during operations [7]. This limitation is further compounded by longer recharging times compared to the rapid refueling of diesel buses, as well as increased energy consumption under adverse weather conditions due to auxiliary loads such as heating and air conditioning systems [8,9]. Moreover, charging infrastructure constraints, including limited charging power and station availability, add complexity to fleet scheduling and operational planning [10]. To mitigate these challenges during the transition toward fully electric bus fleets, plug-in hybrid electric buses are often introduced as an intermediate solution; however, they still require systematic charging planning to maximize electric operation and reduce energy costs and emissions [11]. In general, these challenges underscore the need for effective scheduling strategies that not only account for recharging requirements but also incorporate smart charging management into operational planning, ensuring a balance between service efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and passenger satisfaction. This introduces new complexities to the well-established Vehicle Scheduling Problem (VSP), which traditionally focuses on minimizing operational costs and fleet size while maintaining reliable service [12]. The Electric Bus Scheduling Problem (EBSP) extends the VSP by accounting for the aforementioned additional constraints [13]. Opportunity charging, where EBs recharge during layovers at terminals, end stations, or stops, adds further challenges to the scheduling process [14].

Early approaches to the EBSP build on the Single Depot Vehicle Scheduling Problem (SDVSP) by incorporating constraints unique to EBs. One such study [15] employs a two-stage modeling approach, first forming vehicle blocks and then chaining them while accounting for state of charge and spatial–temporal conditions. This method underscores the impact of limited driving range on fleet size, finding that a 150-mile range allows for significant electrification with a manageable increase in non-revenue time. Subsequent work [16] introduces a column generation-based algorithm to tackle EB scheduling with battery swapping and fast charging options. This approach evaluates real-world transit data to analyze fleet size, operational costs, and emissions, demonstrating its applicability to large-scale transit networks. Another study [17] refines the modeling of charging processes by proposing two frameworks: one assumes linear charging rates and constant electricity prices, while the other incorporates variable prices and battery degradation effects. Multi-depot scenarios are explored in [18], which extends the Multi-Depot Vehicle Scheduling Problem with Time Windows to include constraints such as limits on the number of buses that can be charged simultaneously and restrictions on overlapping use of individual chargers. The study develops a mixed-integer nonlinear programming model and subsequently linearizes it for computational efficiency, allowing for its application to larger problem instances. Similarly, ref. [19] presents a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model for electric bus scheduling that incorporates partial charging and charging at both depots and selected terminal stops through linear energy balance relations. The model explicitly considers constraints such as limited charger availability, where only one bus may charge at a time, and battery state of charge (SoC) requirements. Although convex relaxation can accelerate continuous energy dispatch models [20], the EBSP remains dominated by inherently discrete assignment and sequencing decisions, which naturally leads to mixed-integer formulations. An additional study [21] introduces a three-stage framework combining scheduling and overnight charging under depot layout constraints, jointly optimizing fleet size, battery capacity, and charger usage in a real-world airport shuttle case.

Integrating timetabling and scheduling, ref. [22] proposes a unified framework using a time-space network-based model, addressing trade-offs between fleet size and service quality. This integrated approach improves operational efficiency compared to traditional sequential planning. To address the complexities of mixed fleet operations, ref. [23] proposes a MILP model for optimizing fleets composed of both diesel and electric buses. The study demonstrates that early-stage electrification yields notable cost savings, but the marginal benefits decline as the share of EBs increases due to diminishing operational gains. More advanced methodologies handle large-scale transit systems with additional constraints. For instance, ref. [24] explores the challenges of vehicle relocation and partial charging in multi-depot systems. By applying a Large Neighborhood Search (LNS) heuristic algorithm, the study aims to optimize the battery capacity, charging rates, and charging locations. Another study tackles electric vehicle scheduling by modeling route and charging decisions using a path-based binary optimization approach [25]. To solve the problem efficiently, it employs column generation combined with tailored heuristics, achieving near-optimal solutions with less than 3.5% optimality gap on large-scale Dutch transit data. This approach has recently been extended to jointly optimize charging infrastructure deployment and charging schedules while explicitly accounting for energy system-level aspects, such as renewable energy integration and power distribution network impacts [26]. Further extensions incorporate heterogeneous fleet composition and advanced charging constraints, including multi-gun fast charging and vehicle–charger compatibility [27].

The work presented in this paper builds upon the foundational methodology introduced in [19] and further developed in the authors’ previous work [28]. In contrast to [19], which focuses solely on minimizing the fleet size, this study proposes a multi-objective MILP-based framework that jointly minimizes the fleet size, deadhead distance, and charging cost objectives, while accounting for heterogeneous battery energy, charger power, and charging spot capacities, integrated daily and night charging, and a charge sustaining condition, ensuring that the final batteries’ states of charge match the initial one. The MILP approach is complemented by an Insertion Heuristic (IH) algorithm for generating near-optimal large-scale solutions. Unlike the conventional fleet Insertion Heuristic [12], which relies solely on spatial–temporal proximity, the proposed IH introduces an energy-aware scheduling framework incorporating the aforementioned objectives and constraints. The main contributions of the paper include (i) formulation of a multi-objective MILP model for interactive EB scheduling and charging under realistic operational constraints, (ii) development of IH algorithm as a computationally efficient large-scale alternative to MILP, and (iii) a comparative assessment of MILP and IH approaches across multiple scenarios, highlighting trade-offs between accuracy and computing efficiency.

The remaining part of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the EBSP, including decision variables, constraints, and objectives. Section 3 presents the optimization methodology, covering both MILP and IH approaches. Section 4 describes the case study and analyzes the optimization results comparing MILP and IH solutions. Finally, Section 5 provides concluding remarks and outlines future research directions.

2. Problem Definition

2.1. Electric City Bus Scheduling Framework

Different charging stations (e.g., those at depot, end stations, etc.) may have different operating parameters, including (i) charging power and (ii) the number of EBs they can accommodate for charging simultaneously (i.e., number of chargers). A general scenario of continuous, full-day operation is considered, which unifies night charging and fast recharging, and satisfies the charge sustaining condition at the end of operational day, meaning that each EB starts and finishes an operational day with full battery for repeatable (sustaining) operation the next day(s). It is assumed that bus lines, timetables, charging station locations, and the number of available charging spots per station are predetermined and available for EB scheduling. Additionally, the hourly varying charging unit price for each charging station is assumed to be known in advance. Accordingly, the proposed formulation jointly determines trip-to-EB assignments and charging decisions to minimize fleet size, deadhead distance, and charging cost, while satisfying operational timing, battery capacity, charging station availability, and charge sustaining constraints.

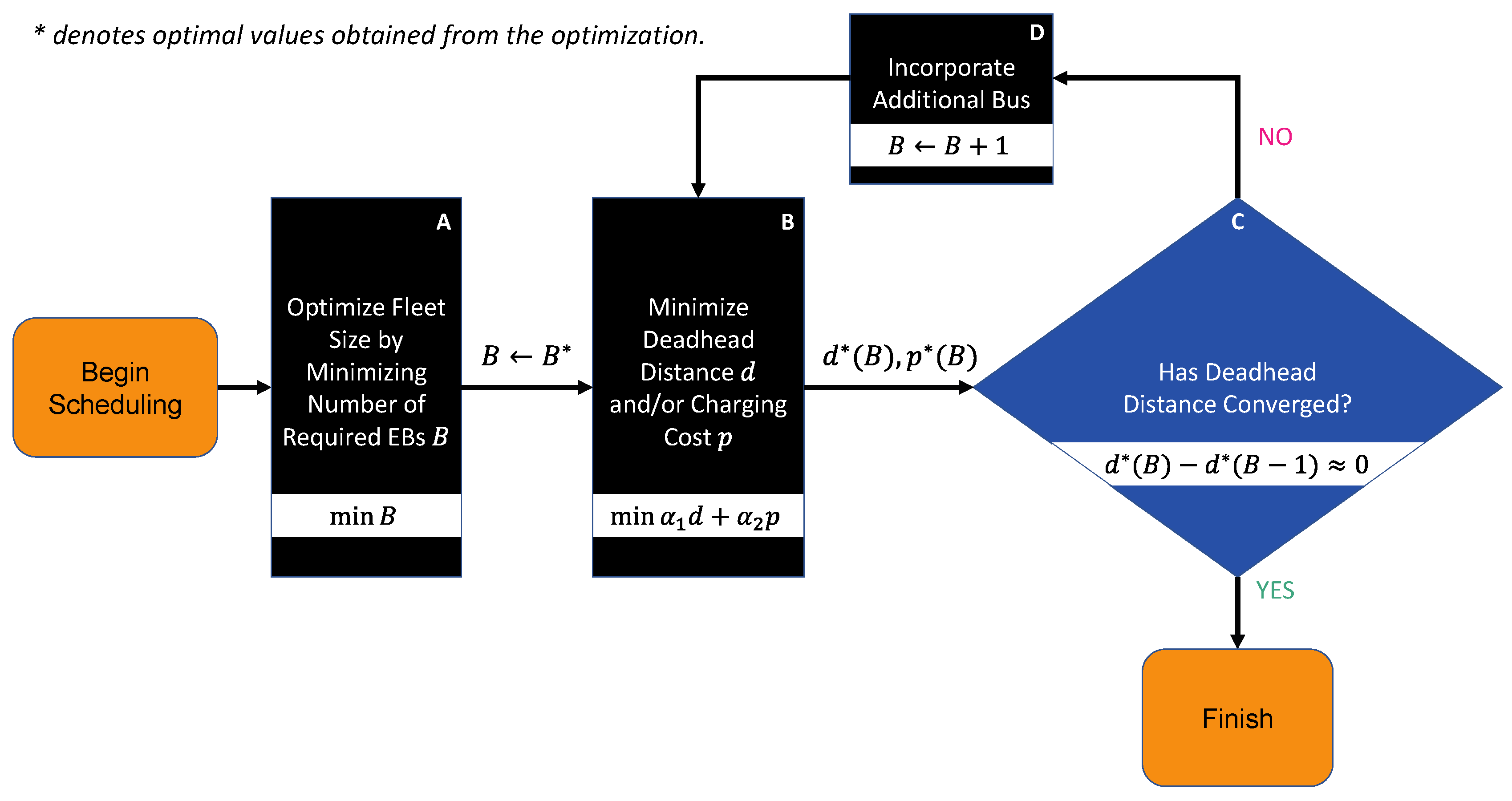

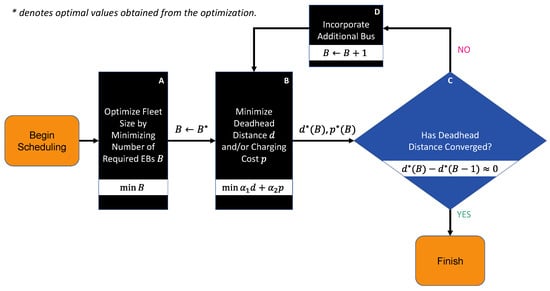

Figure 1 illustrates the EB scheduling optimization process, which begins by determining the minimal number of EBs required to complete the given timetables under the assumption of abundant battery capacity (Block A). Once the minimal fleet size is determined through MILP optimization, the next step focuses on optimizing trip assignment and charging schedules, where each timetable trip is allocated to an EB, aiming to minimize deadhead distance and charging cost (Block B). The deadhead distance is defined as the total distance traveled by empty EBs as they move between different routes to either start their next service trip or recharge at designated charging stations. To explore a trade-off between fleet size and deadhead distance (and also charging cost), the scheduling optimizations are conducted for a range of EB fleet sizes, starting from the minimum number and being incrementally increased (Block D) until the deadhead distance saturates (Block C).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of sequential EB scheduling optimization process.

2.2. Problem Formulation

Let denote the set of service trips awaiting scheduling, and the set of available EBs. Each EB is equipped with a battery of energy level , bounded by its respective minimum and maximum limits , and , thereby allowing for a heterogeneous fleet. Additionally, two specific points are defined: , the depot starting position (source) where EBs initiate their operations, and , the concluding point (sink) where EBs end their service. In the considered EBSP configuration, these two points are set to coincide, i.e., . Each service trip is defined by the following attributes:

- Start time: (minutes from midnight).

- Duration: (minutes).

- Energy consumption: (kWh).

- Start location: (2D Cartesian coordinates [m, m]).

- End location: (2D Cartesian coordinates [m, m]).

Furthermore, a set represents all charging stations, where each station is characterized by the following constant parameters:

- Its location: Situated either at the starting or end stations of the trips (, ), , or at the depot (, ), or at any other designated charging location (terminal) within the network.

- Charging power : Defined in kWh/min at which an EB is recharged.

- Charging spot capacity : The maximum number of EBs that can charge simultaneously (i.e., the number of chargers).

- Hourly charging price : Defined in monetary units per kWh at time , where denotes a discrete time point within the total operational timeline of the EB system.

Finally, the travel time and the respective traveling distance and energy consumption are introduced to denote deadhead traveling between a service trip to a charging station (), a charging station to a service trip (), and between two consecutive service trips, and (). Note that deadhead time, distance, and energy consumption can be zero when the end station of a trip coincides with the departure station of the next trip () or when a charging station is located at the trip’s end station.

When performing EB scheduling, it is essential to address both conventional scheduling constraints and those unique to EBs. The conventional constraints include:

- 1.

- Trip assignment condition where each service trip must be assigned to one, and only one, EB:where is a binary variable indicating whether th trip is assigned to th EB () or not ().

- 2.

- Feasible sequences, where each EB must follow an operationally achievable sequence of service trips:where the set comprises ordered consecutive trip pairs of th EB, ensuring that the start time of succeeding trip must not be earlier than the end time of preceding trip plus the travel time between them .

- EB scheduling is constrained by the predetermined lower and upper battery energy capacities:

Further, each charging station can accommodate only a predetermined number of EBs simultaneously:

where indicates how many EBs are charging at station at time instant . Finally, every EB must complete its operational day with a fully recharged battery, meaning its final energy level must match its initial energy level (charge sustaining condition):

where (1440 min = 24 h). This condition ensures repeatable day-to-day operation, i.e., the schedule remains feasible on consecutive days with no gradual battery depletion, which would, otherwise, be enforced to reduce the charging cost over a single operational day. In a specific (comparative) study, the initial and end battery energy level may be set to be lower than , i.e., one may set , and , where is a user-defined energy target.

Each charging station is associated with a set of charging events , where each event represents a one-hour time window. Charging sessions must be fully contained within a single event (i.e., within one hour), but the start time and duration are arbitrary within that window (and can be extended to the subsequent window through a new event). This enables flexible charging durations while ensuring that the full session is billed at a single, well-defined price . For each event , the applicable charging price is defined as:

where is the start time of event at charging station . The first charging event at station begins at the earliest possible arrival of any EB, rounded down to the previous full hour to align with discrete hourly electricity price intervals:

Subsequent events are spaced in fixed one-hour intervals ():

The charging event horizon is extended to incorporate overnight charging and ensure compliance with the charge sustaining condition at the end of the day:

where is the start time of the last scheduled trip of the previous day. While a finer discretization (e.g., 15 min intervals) could provide higher temporal resolution, the hourly discretization is chosen to align charging decisions with hourly electricity price signals and to limit computational complexity. Importantly, this does not enforce EBs to exclusively charge for a full hour or wait for the next hourly slot, since the charging amount within each interval is optimized as a continuous decision variable and can take on any value between 0 and 1 h (see the charging management results in Section 4.2). To assess the impact of this modeling approach, a finer time discretization is examined in Section 4.

Furthermore, the following supplementary sets are defined to capture the relationships between service trips, charging events, and vehicle schedules, providing a structured representation of feasible transitions, timing constraints, and operational limitations:

- : The set of trips that can feasibly follow trip , where according to (2).

- : The set of trips that can precede trip , where .

- : The set of charging events at charging station , which can begin after trip is completed and the EB reaches the charging station, where .

- : The set of charging events at charging station , which occur before the EB starts trip , where .

- : The set of trips that can start after charging event at charging station , where .

- : The set of trips that can end before charging event at charging station , where .

Several binary decision variables are introduced to optimize the EB fleet scheduling and charging:

- : Indicating whether EB performs service trip after service trip (implies in (1)).

- : Indicating whether EB begins charging at event on charging station after completing service trip .

- : Indicating whether EB starts service trip after completing charging event on charging station .

- : Indicating whether EB continues charging at the subsequent event on the same charging station after charging event .

Additionally, continuous decision variables are introduced to track and manage the battery energy levels of each EB throughout its operation:

- (or for trip ): The battery energy level th EB just before starting service trip .

- : The battery energy level of th EB just before it begins charging at event on charging station .

- : Amount of energy charged to th EB during charging event at charging station .

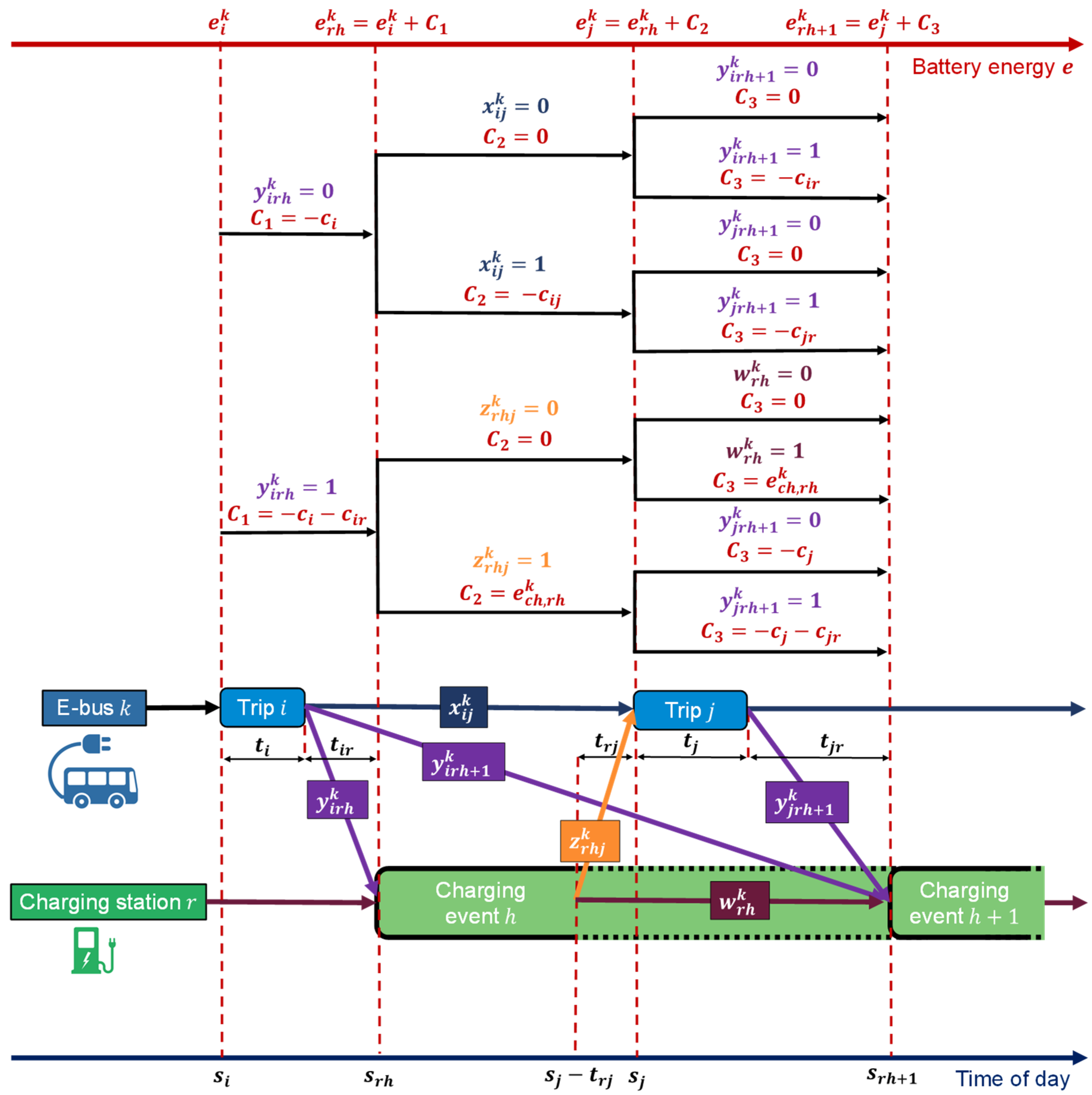

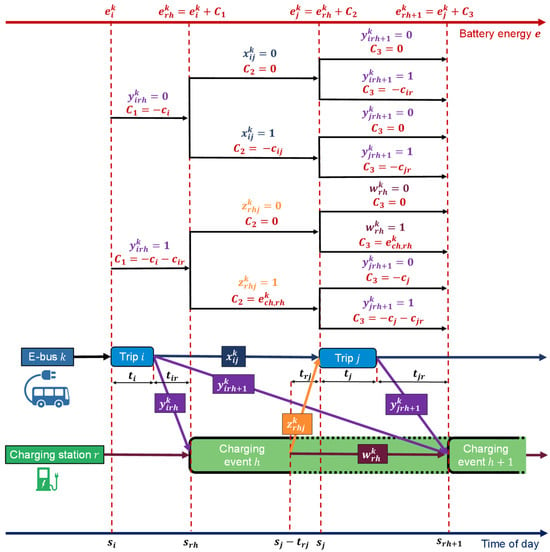

An energy level of individual EBs evolves through two processes: energy decrease due to consumption during trips and deadhead travel, and energy gain due to charging. Conceptually, the binary variables select the next action of each EB (drive to the next trip or charge), while the continuous energy variables track the battery state along the selected sequence. Feasibility is then guaranteed by time-sequencing constraints, charging station capacity limits, and battery bounds, together with the end-of-day charge sustaining condition. As illustrated in Figure 2, the battery state of th EB is updated depending on whether it (i) completes trip and travels from the end of trip to the start of trip (), (ii) completes trip and proceeds to charging event at charging station (), (iii) charges during charging event at charging station and then departs to the start of trip (), or (iv) charges at event and continues charging during the subsequent charging event at the same station (). At each discrete step, only one of these transition variables can be active, reflecting a single action taken by the EB. The corresponding energy variables and are constrained to remain within the battery limits (3), and the overall schedule must satisfy the charge sustaining condition (5), ensuring repeatable day-to-day operation. The change in the EB energy level is covered by the following (unified) battery state equation:

where the charging energy is constrained by:

ensuring that the charge intake is non-negative and does not exceed the maximum possible energy that can be charged within the available time frame under the given charging power . Note that the upper limit reduces to zero if no charging takes place, i.e., if and .

Figure 2.

Visualization of EB scheduling problem formulation.

As an illustration, in the case of with , relation (10) reduces to , which means that the energy at the beginning of th trip, , is determined by the energy level at the beginning of preceding charging event at the charging station r, , energy charged during that event, , and energy consumption for traveling from charging station r to trip j (see illustration in Figure 2).

To optimize EB fleet utilization while satisfying service requirements, the primary objective is to minimize the number of EBs deployed, which directly impacts the investment costs (Block A of Figure 1). As the total fleet size corresponds to the number of EBs dispatched from the depot , the objective function is expressed as:

subject to constraints (1)–(5), which ensure at least one feasible assignment of all service trips given operational and energy constraints.

The secondary objectives to be minimized include the total deadhead distance and the total charging cost (Block B of Figure 1):

3. Solution Approaches

3.1. Insertion Heuristic (IH) Algorithm

The IH scheduling algorithm iteratively assigns service trips to EBs while satisfying imposed operational and energy constraints. Although it does not guarantee a globally optimal solution, its ability to quickly generate feasible schedules makes it valuable for large-scale problems where exact methods are computationally prohibitive. Additionally, it provides a strong baseline against which more advanced optimization techniques can be compared and refined. The overall IH approach is given by Algorithm A1 (Appendix A) and described as follows.

The IH algorithm starts by assuming all EBs depart from the depot with a full battery energy level . All trips are then sorted by their start times to ensure a sequential handling order. For each trip , the set of available EBs is randomly shuffled before assignment, forming a shuffled subset . The introduced stochasticity allows the heuristic algorithm for exploring different assignment patterns across multiple consecutive algorithm executions to construct a Pareto frontier in the considered objectives. For each shuffled EB , an initial schedule feasibility check is performed based on (2). In addition, it should be checked if the charge sustaining condition (5) could be satisfied after completing trip , i.e., if the EB can reach a charging station and fully recharge before the start of its first scheduled trip the next day:

where is a fixed buffer accounting for operational uncertainties, set based on engineering judgment or historical data [29], and is the time required to fully charge the EB after trip :

Here, the energy consumption and the charging price are determined based on the nearest available charging station . If the closest charging station cannot be used due to the breach of simultaneous charging capacity constraint (4), the next nearest charging station is evaluated. The th EB proceeds to the assignment phase only if both conditions (2) and (15) are satisfied; otherwise, it is excluded from the working set , and the next EB in the shuffled set is evaluated. Once an EB passes the initial feasibility checks, the available battery energy is verified to determine whether the EB can perform trip . Specifically, it must have sufficient energy to (i) pass to the starting station of trip j (from trip ), (ii) perform trip j, and (iii) reach the nearest charging station after trip completion:

Once a suitable EB is found while iterating through , the assignment is completed and the process moves to the next trip.

If, however, no EB in can perform trip due to insufficient energy, the iteration over the shuffled set is restarted, and the EBs are re-evaluated to determine if they can feasibly insert a charging event between trip and trip , i.e., if the following condition is satisfied:

If (18) holds, the minimum required charging energy after th trip is calculated as:

Available charging events are then evaluated to ensure if they fit within the available time window between trips and , namely:

while also satisfying the simultaneous charging capacity constraint (4). If a single charging event does not provide sufficient energy to meet (i.e., if ), multiple sequential charging events are checked. The algorithm then searches through all possible sequences of consecutive charging events and selects the sequence with the lowest total charging cost defined by (14). If no feasible charging option exists at the current charging station, the algorithm proceeds to evaluate the next closest charging station. If no charging station can satisfy the required energy, timing, and simultaneous charging constraints, the algorithm then proceeds to evaluate the next EB in the shuffled set until a suitable assignment is found.

After all trips have been assigned, a final charging phase is scheduled at the end of the operational day to satisfy the charge sustaining condition (5), ensuring that each EB is fully recharged and ready to operate the next morning. Charging can take place at any available station, not necessarily at the depot . To prioritize charging operations, EBs are sorted based on their available time gap , defined as the difference between the start time of their first trip the next day and the end time of their final trip :

The total energy required for additional charging is defined as:

Potential charging stations for final charging are evaluated sequentially, starting with the closest one. Available charging events at charging station must (i) fit within the charging availability time window, i.e., , and (ii) comply with the simultaneous charging constraint (4). If no feasible sequence is available at the current charging station, the next closest charging station is evaluated, and among all feasible options, the lowest-cost sequence is selected according to (14).

3.2. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Formulation

3.2.1. General MILP Formulation

The general form of MILP problem is given as follows [30]:

subject to:

where and y represent the vectors of continuous and integer (binary) decision variables, respectively, and are cost coefficients of the objective function, , , and define the constraint matrices governing system relationships, and and are constraint limits based on operational requirements. Thus, the overall optimization problem should be prepared in the form (23) and (24) to be appropriate for solving with existing MILP solvers. While the MILP solvers can generally handle equality constraints directly (), they are often reformulated through two inequalities ( and ) (or eventually relaxed via slack variables) [30]. This approach improves numerical stability, and also allows the solver to treat all constraints in a consistent format, which simplifies presolve and improves convergence [31]. The MILP solvers offer robust capabilities, including guaranteed global optimality, convergence to feasible solutions, and automatic termination if constraints cannot be satisfied. For this study, the Gurobi solver [32], accessed through the PuLP library in Python, is utilized to solve the MILP formulation.

3.2.2. Objective Functions

The main aim is to provide Pareto optimal solutions in terms of total number of EBs, deadhead distance, and charging costs. In the first step, the optimization focuses on minimizing the number of EBs in accordance with objective function (12), which is needed to cover all trips (Block A in Figure 1; Section 2). To explore the trade-off between the deadhead distance and charging cost, objectives (13) and (14) are combined into a weighted normalized objective function:

where , and are reference values used for normalization, and and are the weighting factors satisfying and allowing for adjusting trade-off between the two objectives. It should be noted that, in general, the weighted-sum approach may not capture non-convex regions of the Pareto frontier, in which case alternative approaches such as the ε-constraint method or Chebyshev-based scalarization can be applied [33].

3.2.3. Vehicle Scheduling Constraints

The first vehicle scheduling constraint addresses the trip assignment condition (1), enforcing that every trip is either preceded by another trip from the feasible set or follows a charging event at charging station , belonging to (see Section 2 for definition of the sets and decision variables):

To ensure a continuous sequence of trips and charging events, the following flow conservation constraint enforces that the schedule assigned to each EB remains connected and feasible:

More specifically, it guarantees that every trip has exactly one predecessor m, which can be another trip or a charging event , and one successor, either another trip or a charging event . Building upon the flow constraint, it is further required that each EB either departs after charging or continues charging in the next time slot:

To ensure that, during the deadhead distance and charging cost minimization given by (25), the schedule uses exactly EBs optimized through (12), the following constraint is imposed:

3.2.4. Energy Consumption Constraints

The initial energy constraint ensures that each EB starts its operation with a fully charged battery:

Furthermore, each EB must satisfy the general energy feasibility constraint (3). Firstly, the EBs’ energy levels are to be kept above the minimum threshold while accounting for the energy consumption for the next trip:

In addition, if an EB charges at station before starting trip (), its energy level after charging must be sufficient to reach trip :

where a sufficiently large constant (big-M; [34]) is used to deactivate the constraint when no charging occurs. Similarly, the following constraint enforces the upper battery energy limit for th EB being charged at station before trip j:

The number of EBs being simultaneously charged at station must not exceed its available charging spots (cf. constraint (4)):

It is also necessary to ensure that each EB completes its schedule with a fully charged battery according to the charge sustaining condition (5), i.e., the energy level at the final depot (sink, ) is to reach its maximum level:

As discussed with constraint (5), this constraint can be relaxed by replacing with a user-defined terminal target , and the same relaxation applies to the initial energy constraint in (30). Note that (35) when combined with (33) for implements the equality constraint (see discussion in Section 3.2.1). Moreover, to ensure that every EB completes its daily operation by returning to the depot, it is required that each EB is assigned exactly one transition from its final charging event at station to the sink (including the case where the final charging event occurs at the depot itself):

To ensure that EBs have sufficient time to fully recharge before starting service on the following day in accordance with (5), it is necessary to verify that the final charging event is completed early enough in relation to the first trip the next day. This constraint links the first trip departing from the depot the next day with the EB’s return to the depot after the finish of its last charging event at charging station :

The following two inequalities implement an equality constraint on energy conservation between two consecutive service trips and assigned to the same EB (cf. (10)):

The constraint is deactivated through the big-M approach (with M = , specifically) if no direct transition occurs between the two trips (i.e., if ).

Similarly, the following constraints govern the energy conservation when transitioning to a charging station (cf. (10)):

Next, a couple of additional constraints are introduced to account for energy conservation in the cases when an EB undergoes charging, again in accordance with the energy state equation (10) (see also Figure 2). Unlike trip-to-trip transitions, strict energy balance is not imposed here; instead, the charging amount is treated as a decision variable within the available time interval of duration , constrained within the feasible range defined by (11) and optimized to minimize costs (14). If an EB charges before trip (i.e., ), its energy is updated based on the available charging time, charger power , and energy needed to reach trip from charging station :

Constraint (42) defines the upper bound, allowing the EB to charge up to the maximum feasible energy level permitted by the absolute limit in (33), while constraint (43) defines the lower bound, ensuring that the EB’s energy after charging cannot be lower than what it would have been if it had left the station without recharging. Similarly, the following constraints ensure energy conservation when charging EBs across consecutive time slots:

Building upon the charging energy bounds (42)–(45), the following two pairs of constraints are introduced to explicitly link the actual change in the EB’s battery level and the charged energy used in the total charging cost (14):

4. Case Study and Optimization Results

4.1. Case Study Description

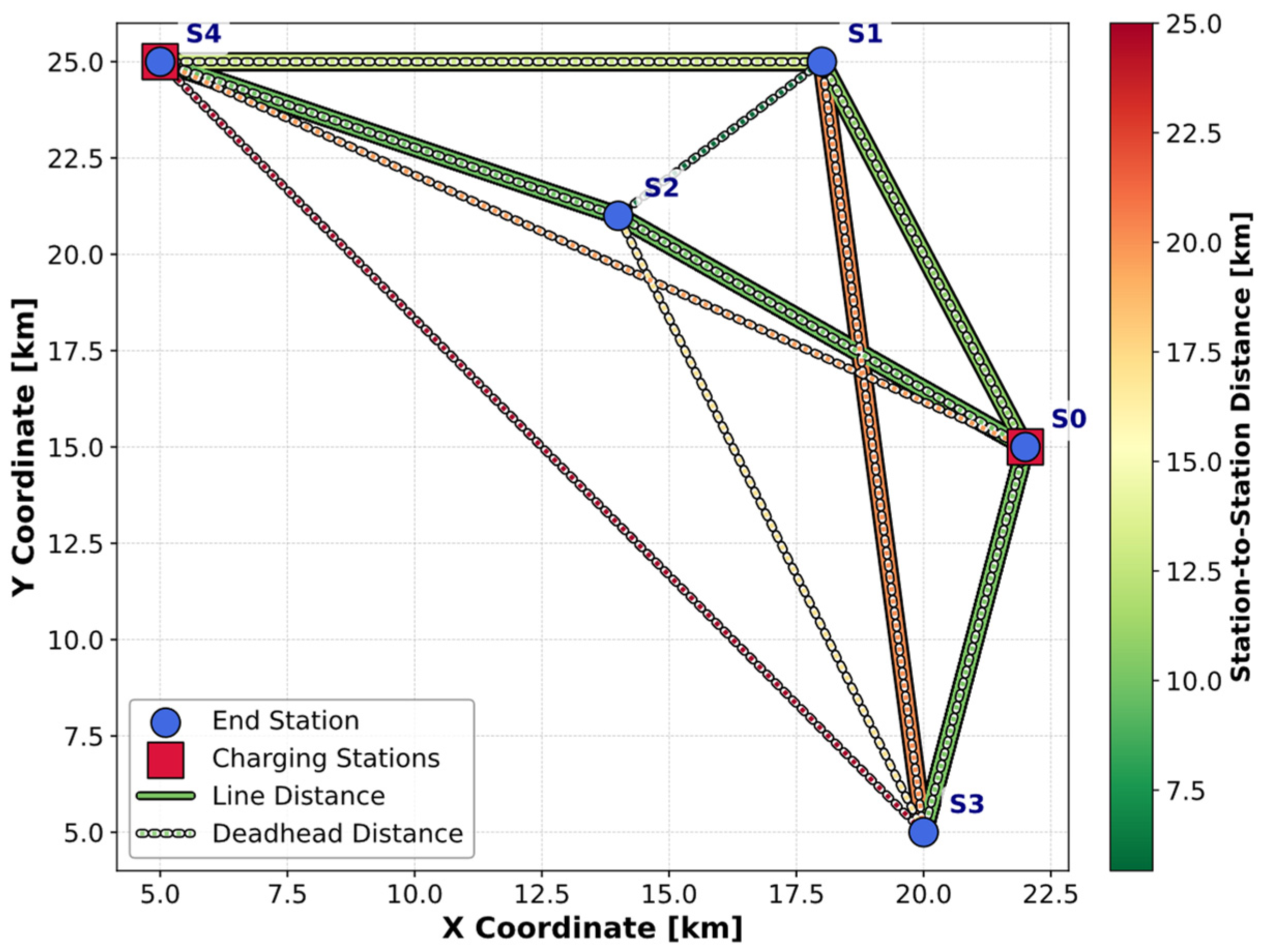

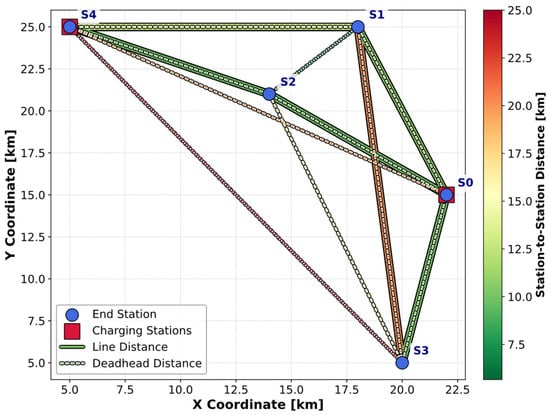

The proposed optimization method has been evaluated through a case study involving 20 trips (i.e., trip set cardinality ) spanning across nine distinct bus lines. As specified in Figure 3 and Table 1, each line is defined by two endpoints selected from a set of five predefined end stations (including two charging stations), which are uniformly randomly distributed in a 30 × 30 Cartesian grid to ensure line diversity. Based on the station locations, both service line and deadhead distances are calculated and distinguished in Figure 3 by solid and dashed lines, respectively. The EBs and charging stations are assumed to have the battery capacity of and the power capacity of 84 kW, respectively. Three EBs can simultaneously be charged at each charging station (. In all experiments, the safety margin included in constraint (15) is set to min to avoid introducing additional conservatism into the schedules.

Figure 3.

Spatial representation of bus stations, lines, and charging stations.

Table 1.

Trip timetable and energy consumption.

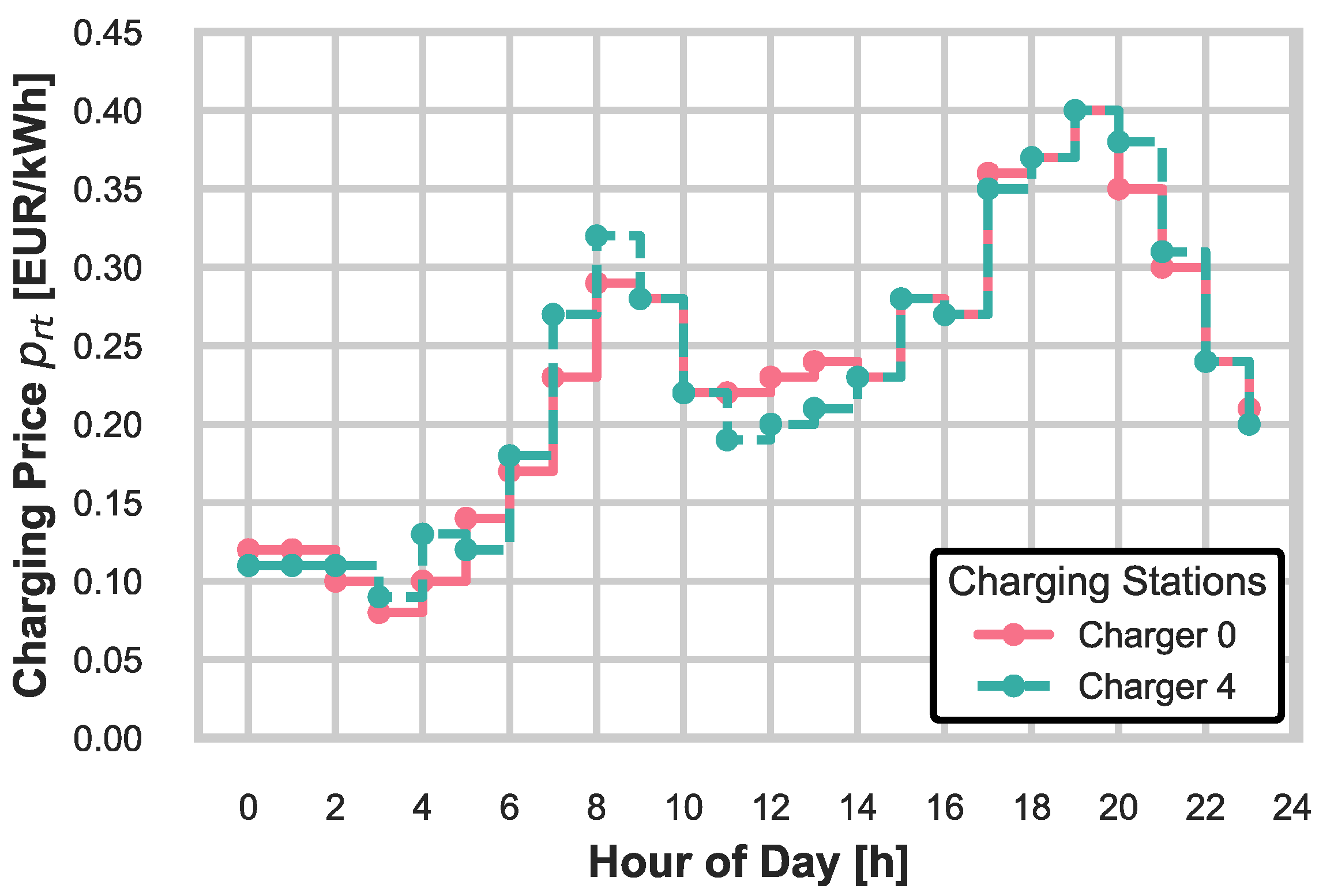

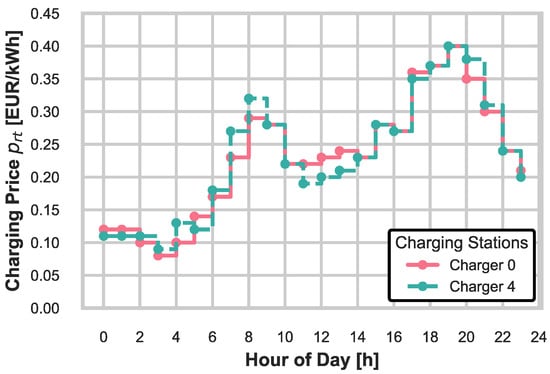

The trip departure times from Table 1 are randomly sampled from the uniform distribution, [min], where the time gaps between consecutive trip departures are drawn from [min]. The average trip velocities and corresponding energy consumption rates follow [km/h] and [kWh/min], respectively, where is expressed in kWh per minute (rather than per kilometer) to remain consistent with the time-based scheduling and charging formulation. The charging price profile is shown in Figure 4, and it reflects a typical daily pattern, with higher rates occurring during peak hours.

Figure 4.

Charging price time profile.

4.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Results

The EB scheduling problem was solved for the transport system from Section 4.1 by using the optimization setup outlined in Figure 1 and the IH and MILP methods proposed in Section 3. In the first step, the minimum number of EBs required to cover all trips from Table 1, while maintaining their feasibility, was determined by the MILP approach formulated by the objective function (12). It was found that six EBs were required to accommodate all 20 trips. In the second step, both optimization methods were applied to simultaneously minimize the deadhead distance and the charging cost for the fleets with the minimum and incrementally increased fleet sizes (Figure 1). By shuffling the set of available EBs (Section 3), the IH method generated 10,000 feasible solutions for each considered fleet size. Meanwhile, the MILP approach explored the trade-off between the deadhead distance and charging cost through changing the weighting coefficients of the weighted objective function (25): and .

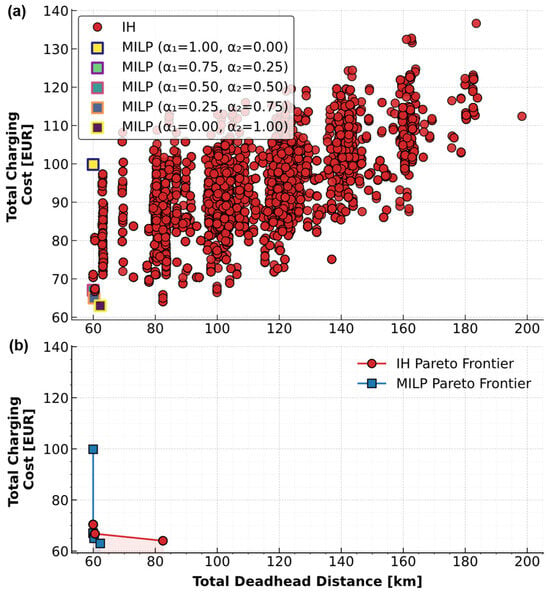

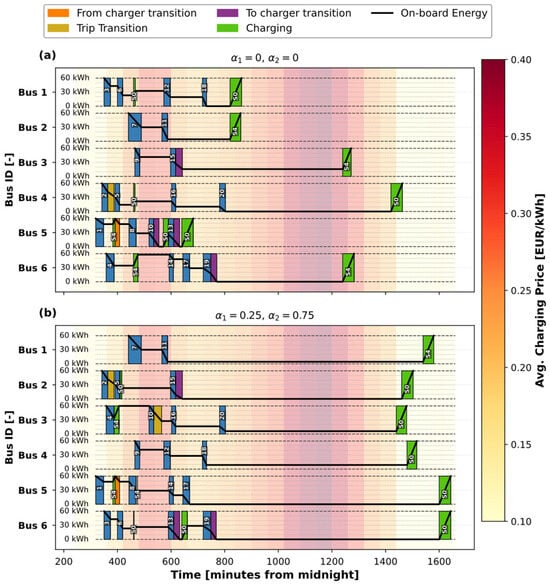

The optimization results are shown in Figure 5 for the minimum fleet size. From the large set of feasible solutions produced by the IH algorithm, only the Pareto optimal ones are shown in Figure 5b. They represent best-performing trade-offs, while most run-to-run variability occurs among dominated (non-Pareto) solutions. These non-dominated IH solutions (red circles) align closely with the globally optimal MILP results (blue squares). The MILP results point out that, when only the charging cost is concerned (), the obtained solution is nearly identical to the one produced when both objectives are weighted equally ( = = 0.5). When only deadhead distance is minimized (), the deadhead distance barely reduces compared to the case . In summary, narrowing the optimization to a single objective leads to a solution that is approached by the dual-objective solution in the same (single) objective. This effect is further illustrated in Figure 6, which compares the trip and charging schedules for the following two optimization cases: (a) deadhead distance minimization only (, Figure 6a), and (b) combined deadhead distance and charging cost minimization (; Figure 6b). As shown in Figure 5, the total deadhead distance remains nearly identical in both cases, even though the charging costs differ significantly. Figure 6 visualizes how the charging events distribute in time. In Case (a), the charging cost is not accounted for, leading to the charging of several buses during high-tariff periods (e.g., between 1000 and 1300 min). That is, the charging decisions are purely driven by trip sequencing feasibility for deadhead distance minimization, i.e., with no regard for economic efficiency. In contrast, in Case (b), charging events are rescheduled towards off-peak periods with lower tariffs. A similar effect was observed when only the charging cost was minimized (case in Figure 5a). In this case, the optimizer naturally selects the cheapest available charging options while ensuring feasibility, and as the feasible set of solutions does not significantly impact the deadhead distance, the resulting routes remain largely the same.

Figure 5.

Comparison of MILP and IH solutions for minimal feasible fleet size (six EBs) (a) and corresponding Pareto frontiers (b).

Figure 6.

Bus trip and charging schedules for deadhead distance minimization only () (a) and combined deadhead distance and charging cost minimization () (b) for minimal feasible fleet size (six EBs).

Figure 5b further indicates that the Pareto frontiers are quite narrow, meaning that no pronounced trade-off is observed between deadhead distance and charging cost. This is because the two metrics are strongly correlated, i.e., increasing the deadhead distance generally raises energy consumption and thus the total charging cost. Nevertheless, the strength of this correlation is generally case-dependent and may weaken in networks with stronger spatial/temporal price variability and charging infrastructure constraints, where longer deadhead trips can enable access to substantially cheaper charging options.

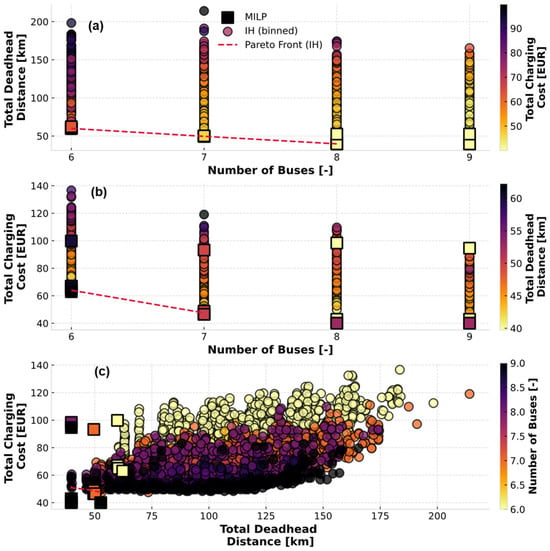

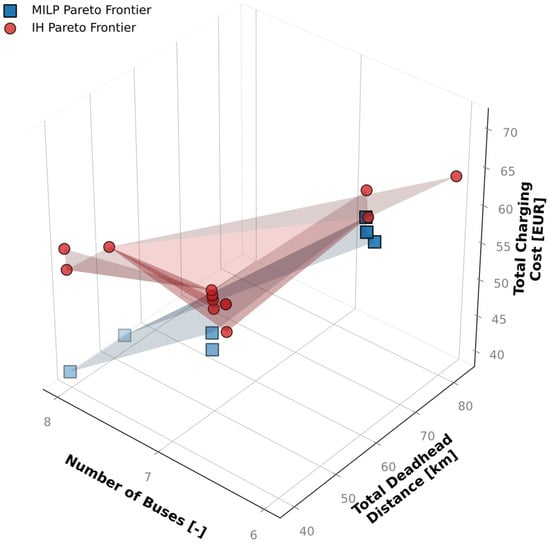

Performing scheduling for incrementally enlarged fleet sizes reveals that the total deadhead distance saturates at eight buses (Figure 7a). Both MILP and IH solutions follow this trend, with IH Pareto solutions (dashed red line) closely aligning with the MILP ones, demonstrating the effectiveness of the practical (computationally inexpensive) IH algorithm in approximating the optimal deadhead distances. Figure 7b indicates that increasing the fleet size generally reduces the total charging costs, as a direct consequence of the reduced deadhead distance. Again, the IH solutions show a good approximation to MILP results, especially for smaller fleets. Figure 7c and Figure 8 provide a 3D representation of the optimization results and the corresponding Pareto frontiers, which visualize the trade-offs in a single plot and confirm the favorable accuracy of the IH solutions. The designer can select any solution on the Pareto frontier based on specific priorities.

Figure 7.

Comparison of MILP and IH solutions across different fleet sizes: deadhead distance vs. fleet size (a), charging cost vs. fleet size (b), and charging cost versus deadhead distance (c), where color denotes the remaining variable.

Figure 8.

3D Pareto frontiers extracted from MILP and IH solutions.

Table 2 further confirms that the deadhead distance reaches saturation for the eight-EB fleet. When switching from six to seven EBs, the total charging cost in MILP reduces by 26%, and by an additional 14% for seven to eight EB shifts. The IH approach successfully finds the global optimum in terms of deadhead distance and achieves near-optimal charging costs for six and seven buses. However, for eight and nine buses, IH solutions exhibit higher charging costs. This charging cost excess is apparently due to the larger solution space, making it more challenging for the heuristics to consistently find the cost-optimal charging configurations with the fixed number of designs.

Table 2.

Comparison of minimal total deadhead distance and charging cost obtained by MILP and IH solutions for different fleet sizes.

Table 3 compares the computational efficiency of the MILP and IH approaches. The results show that MILP runtime increases sharply with fleet size due to the rapid growth in binary variables and constraints, whereas the IH method maintains high scalability and produces a large set of feasible solutions within seconds. Interestingly, IH runtime slightly decreases as the fleet size grows, since a larger number of available EBs reduces the need for inserted charging events and the number of iterations required for feasible trip assignment. Memory usage follows a similar trend, with MILP demands increasing moderately with fleet size, while IH requirements remain nearly constant. These results demonstrate that computational efficiency is a key limiting factor for viable EB scheduling, particularly for real-time and near-real-time applications, where operational changes may require fast rescheduling. Accordingly, MILP mainly serves as an offline globally optimal benchmark for smaller networks, whereas IH offers a scalable and computationally efficient solution for large-scale problem settings, including real-time application.

Table 3.

Computational performance comparison of MILP and IH approaches across different fleet sizes.

The impact of charging-slot discretization on MILP performance was evaluated by solving the six-bus network () for a four-fold finer charging time step min. As demonstrated in Table 4, the resulting deadhead distance and charging cost remain unchanged owing to the flexible charging durations within each discretized time slot (Section 2). However, the total MILP runtime increases substantially due to the larger number of charging decision slots (and corresponding binary variables), while memory usage rises only moderately.

Table 4.

Illustration of MILP computational performance sensitivity to charging-slot discretization step for six-bus network (B = 6).

To further assess the scalability of the IH algorithm to larger-scale transport systems, an additional analysis is conducted through increasing the system size in terms of the number of trips and EBs , while simultaneously scaling the transport network in terms of the number of stations , charging stations , and charging spot capacity . All the remaining parameters (e.g., battery capacity, charging power, and electricity price structure) are kept unchanged with respect to the original case study from Section 4.1. For each tested network, the IH is executed to generate 10,000 feasible solutions, from which the computational statistics are drawn. The results in Table 5 confirm that the IH approach remains computationally tractable as the system size grows, with the runtime increasing in a roughly linear manner with problem size and the memory usage remaining moderate. Even for the largest tested network (, , and ), the average runtime per generated solution remains below 1 s, supporting the applicability of IH for large-scale offline planning and time-sensitive rescheduling.

Table 5.

IH computational performance for increasing system size.

5. Conclusions

This study has dealt with electric bus scheduling through the minimization of fleet size, deadhead distance, and charging cost. Two approaches were proposed: Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), providing globally optimal solutions for small-scale systems, and computationally efficient Insertion Heuristic (IH), designed to generate large sets of feasible, near-optimal solutions.

A case study of a realistic transport network has demonstrated that the MILP approach captures the trade-offs between deadhead distance and charging cost. The results reveal that both deadhead distance and charging cost decrease with fleet size increase, until reaching a saturation point. The IH approach produces solutions that closely approximate the MILP Pareto frontier in the three objectives at a fraction of the computational time and memory. This makes the IH method particularly suitable for larger-scale or time-sensitive applications where MILP becomes computationally prohibitive.

Although this paper focuses on battery electric buses (BEBs), the proposed scheduling and charging framework can readily be extended to plug-in hybrid electric bus (PHEB) fleets and mixed BEB-PHEB fleets by adapting the trip-related battery energy consumption model, while preserving the same scheduling structure and infrastructure constraints. Moreover, the proposed MILP and IH frameworks are not tied to synthetic assumptions and can be directly applied to real-world operational data (e.g., trip schedules, charging prices, and charger locations) without any structural changes. Currently, application of the proposed framework is being carried out within the OLGA project [35], and the corresponding results will shortly be disseminated through a publicly available project deliverable.

Future research could extend this framework by incorporating the optimal placement of charging stations, real-time scheduling adjustments, stochastic trip demands, battery degradation effects, and integration with timetabling and crew scheduling. Additionally, the use of metaheuristics such as genetic algorithms (GAs) would enhance scalability and adaptability in large, complex networks, potentially bridging the IH approach’s accuracy gap with respect to the MILP benchmark while maintaining computational efficiency. The development of such a GA approach is the subject of the authors’ upcoming publication, which would include a comparative IH vs. GA evaluation for large-scale systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D., B.Š. and J.D.; Methodology, Z.D., B.Š. and J.D.; Software, Z.D.; Visualization, Z.D.; Formal Analysis, Z.D., B.Š. and J.D.; Investigation, Z.D.; Supervision, B.Š. and J.D.; Project Administration, J.D.; Funding Acquisition, J.D.; Writing—Original Draft, Z.D.; Writing—Review and Editing, B.Š. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

It is gratefully acknowledged that this work has been supported by the European Commission through Horizon 2020 Innovation action project OLGA (“hOListic Green Airport”) under the Grant Agreement No. 101036871.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code supporting this study are openly available at: https://github.com/zvonimirdabcevic/transit-scheduling (accessed on 30 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional | |

| BEB | Battery Electric Bus | |

| EB | Electric Bus | |

| EBSP | Electric Bus Scheduling Problem | |

| EV | Electric Vehicle | |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm | |

| IH | Insertion Heuristic | |

| LNS | Large Neighborhood Search | |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming | |

| PHEB | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Bus | |

| SoC | State of Charge | |

| SDVSP | Single Depot Vehicle Scheduling Problem | |

| VSP | Vehicle Scheduling Problem | |

| Nomenclature | ||

| Sets | ||

| set of service trips, indexed by | ||

| set of electric buses (EBs), indexed by | ||

| set of charging stations, indexed by | ||

| set of charging events (time slots) at station , indexed by | ||

| discrete time points within operational horizon | ||

| depot source node (start of operation) | ||

| depot sink node (end of operation) | ||

| set of trips that can feasibly follow trip | ||

| set of trips that can feasibly precede trip | ||

| set of charging events at station feasible after trip | ||

| set of charging events at station feasible before trip | ||

| set of trips feasible after charging event | ||

| set of trips feasible before charging event | ||

| Parameters | ||

| start time of trip , min | ||

| duration of trip , min | ||

| energy consumption of trip , min | ||

| start and end location of trip , m | ||

| deadhead travel from trip to , min | ||

| deadhead distance from trip to , m | ||

| deadhead energy consumption from trip to , kWh | ||

| charging power at station , kWh/min | ||

| charging spot capacity (number of chargers) at station | ||

| electricity price at station at time , EUR/kWh | ||

| electricity price during charging event , EUR/kWh | ||

| start time of charging event , min | ||

| duration of a charging event (charging time discretization step), min | ||

| minimum and maximum battery energy of th EB, kWh | ||

| safety time margin used in feasibility checks, min | ||

| time required to fully charge EB, min | ||

| fixed fleet size used in multi-objective analysis | ||

| weighting coefficients for deadhead distance and charging cost objectives | ||

| deadhead distance normalization constant | ||

| charging cost normalization constant | ||

| large positive constants used for conditional constraints | ||

| Decision Variables | ||

| 1 if th EB performs trip directly after trip , 0 otherwise | ||

| 1 if th EB starts charging at charging event after trip , 0 otherwise | ||

| 1 if th EB starts trip after charging at event , 0 otherwise | ||

| 1 if th EB continues charging from event to , 0 otherwise | ||

| battery energy of th EB before starting trip , kWh | ||

| battery energy of th EB before charging at event , kWh | ||

| energy charged to th EB during charging event , kWh | ||

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1. Insertion Heuristic (IH) scheduling approach | |||

| Input | |||

| ← | set of service trips, sorted by start time | ||

| ← | set of EBs | ||

| ← | set of charging stations | ||

| ← | set of trips that can legally follow trip | ||

| ← | set of charging events available at station | ||

| ← | number of chargers per charging station | ||

| ← | lower and upper individual battery energy limits | ||

| ← | energy required for driving | ||

| ← | charging rate during event at charging station | ||

| ← | starting and final point of each EB being at depot | ||

| Output—decision variables | |||

| ← | EB starts trip immediately after trip | ||

| ← | EB starts charging in slot of charging station after trip i | ||

| ← | EB continues charging in the next slot | ||

| ← | EB starts trip immediately after charging | ||

| ← | battery energy level of EB before starting trip | ||

| ← | battery energy level of EB before starting charging at event at station | ||

| INITIALIZATION | |||

| for each EB do | |||

| ← // previous trip, starting from depot | |||

| ← | |||

| ← ∞ | |||

| ← 0, ← 0, ← 0, ← 0; | |||

| end for | |||

| for each charging station do | |||

| for each charging event at charging station do | |||

| ← 0 | |||

| end for | |||

| end for | |||

| MAIN LOOP—assign every trip j ∈ N | |||

| for each trip do | |||

| ← RandomShuffle() // working list for this trip | |||

| trip_assigned ← False | |||

| // A. Direct assignment (no intermediate charging) | |||

| for each EB while !trip_assigned do | |||

| ← | |||

| // sequence & charge sustain checks | |||

| if ≠ or or !ChargeSustain(k, j) then | |||

| ← // Excluding EB k from set | |||

| continue // To next EB candidate | |||

| ← nearest charging station after trip | |||

| if then | |||

| ← | |||

| trip_assigned ← True | |||

| ← | |||

| if == then | |||

| ← | // Define start of first trip for following day | ||

| end if | |||

| end for | |||

| // B. assignment with pre-charging (if needed) | |||

| for each EB while !trip_assigned do | |||

| ← | |||

| for each station r ∈ R (nearest-first from end of trip ) do | |||

| if then continue | |||

| ← | |||

| ← { | |||

| // contains ordered charging events | |||

| if then | |||

| ← first(); ← last() | |||

| ← 1; ← + 1; ← | |||

| for each consecutive pair (, ) in S do | |||

| if then | |||

| ← 1; ← + 1 | |||

| end if | |||

| ← min (,()) | |||

| end for | |||

| ← 1; ← + 1 | |||

| ← | |||

| trip_assigned ← True | |||

| ← | |||

| break | |||

| end if | |||

| end for | |||

| end for | |||

| if !trip_assigned then | |||

| report “Trip infeasible” and terminate algorithm | |||

| end if | |||

| end for | |||

| CHARGE SUSTAINING CONDITION | |||

| sort(K) by , in ascending order | |||

| for each EB do | |||

| for each station r ∈ R (nearest-first from end of final trip) do | |||

| if then continue | |||

| ← { | |||

| if then | |||

| ← first(S); ← last(S) | |||

| ← 1; ← + 1; | |||

| ← | |||

| for each consecutive pair (, ) in S do | |||

| if then | |||

| ← 1; ← + 1 | |||

| end if | |||

| ← min (,()) | |||

| end for | |||

| ← 1 | |||

| ← | |||

| break | |||

| end if | |||

| end for | |||

| end for | |||

| Auxiliary procedures | |||

| ChargeSustain (k, j): | |||

| for each station r ∈ R (nearest-first from end of trip ) do | |||

| ← | |||

| if return True | |||

| return False | |||

References

- Braun, A.; Rid, W. Energy consumption of an electric and an internal combustion passenger car: A comparative case study from real-world data on the Erfurt circuit in Germany. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 27, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalghatgi, G. Is it really the end of internal combustion engines and petroleum in transport? Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topić, J.; Soldo, J.; Maletić, F.; Škugor, B.; Deur, J. Virtual simulation of electric bus fleets for city bus transport electrification planning. Energies 2020, 13, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.S.G.; Lusby, R.M.; Larsen, J. Electric bus planning and scheduling: A review of related problems and methodologies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Chen, T.; Fan, W. Integrated approach to vehicle scheduling and bus timetabling for an electric bus line. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04019073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.S.G.; Dollevoet, T.; Huisman, D.; Lusby, R.M.; Larsen, J.; Riis, M. Solution approaches for integrated vehicle and crew scheduling with electric buses. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 132, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallmann, T.; Delgado, O.; Jin, L.; Minjares, R.; Gadepalli, R.; Cheriyan, C.A. Strategies for deploying zero-emission bus fleets: Route-level energy consumption and driving range analysis. Int. Counc. Clean Transp. 2021, Working Paper 2021–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dabčević, Z.; Škugor, B.; Cvok, I.; Deur, J. A trip-based data-driven model for predicting battery energy consumption of electric city buses. Energies 2024, 17, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabčević, Z.; Škugor, B.; Topić, J.; Deur, J. Synthesis of Driving Cycles Based on Low-Sampling-Rate Vehicle-Tracking Data and Markov Chain Methodology. Energies 2022, 15, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiotsalitis, K. Bus holding of electric buses with scheduled charging times. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 6760–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wan, M.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhu, Z. Driver-Oriented Adaptive Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy for Plug-in Hybrid Electric Buses. Energies 2025, 18, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.M. Algorithms for the vehicle routing and scheduling problems with time window constraints. Oper. Res. 1987, 35, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lin, X.; He, F. Robust scheduling strategies of electric buses under stochastic traffic conditions. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, C.; Kepaptsoglou, K. Integrated transit route network design and infrastructure planning for on-line electric vehicles. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2019, 77, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokyasar, T.; Verbas, O.; Davatgari, A.; Mohammadian, A.K. Solving the electric vehicle scheduling problem at large-scale. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Bilbao, Spain, 24–28 September 2023; pp. 1134–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-Q. Transit bus scheduling with limited energy. Transp. Sci. 2014, 48, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kooten Niekerk, M.E.; van den Akker, J.M.; Hoogeveen, J.A. Scheduling electric vehicles. Public Transp. 2017, 9, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiotsalitis, K.; Iliopoulou, C.; Kepaptsoglou, K. An exact approach for the multi-depot electric bus scheduling problem with time windows. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovec, M.; Koháni, M. Exact approach to the electric bus fleet scheduling. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 40, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chung, C.Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Lin, W.; Wang, C. Enabling High-Efficiency Economic Dispatch of Hybrid AC/DC Networked Microgrids: Steady-State Convex Bi-Directional Converter Models. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabčević, Z.; Deur, J. Interactive optimization of electric bus scheduling and overnight charging. Energies 2025, 18, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yu, Y.; Long, J. Integrated electric bus timetabling and scheduling problem. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 149, 104057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Picarelli, E.; D’Ariano, A.; Viti, F. Mixed-fleet single-terminal bus scheduling problem: Modelling, solution scheme and potential applications. Omega 2020, 96, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Multi-depot electric bus scheduling considering operational constraints and partial charging: A case study in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, M.; van Lieshout, R.N.; Dollevoet, T. Electric vehicle scheduling with capacitated charging stations and partial charging. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.13734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Gao, K.; Parishwad, O.; Tsaousoglou, G.; Jin, S.; Yi, W. Integrated Optimization of Charging Infrastructure, Electric Bus Scheduling and Energy Systems. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 141, 104664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, M.; Zhang, R.; Peng, R. Joint Optimization of Electric Bus Infrastructure Planning, Fleet Composition, and Charging Schedule Considering Multi-Gun Charging and Compatibility. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6690–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabčević, Z.; Škugor, B.; Deur, J. Pareto optimization of electric city bus scheduling. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems (SDEWES), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Yao, E.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Joint optimal scheduling for a mixed bus fleet under micro driving conditions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 2464–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemhauser, G.L.; Wolsey, L.A. Integer and Combinatorial Optimization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, J. Linear Programming Notes V: Problem Transformations; University of California San Diego: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://econweb.ucsd.edu/~jsobel/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual; Gurobi Optimization, LLC: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.gurobi.com (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Clímaco, J.C.N.; Pascoal, M.M.B. An Approach to Determine Unsupported Non-Dominated Solutions in Bicriteria Integer Linear Programs. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2016, 54, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.P. Model Building in Mathematical Programming, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OLGA Consortium. OLGA Project—Public Reports and Deliverables. 2024. Available online: https://www.olga-project.eu/reports (accessed on 28 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.