Abstract

In traditional industry setups, Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) follow trajectories planned together with the layout of the storage or production facility and supported by fixed markers on the floor or on the walls. Traffic rules manage the avoidance of multiple vehicles, while fleet management gets movement and transportation commands completed as soon as possible. In contrast, recent developments in navigation and advanced computing, sensor, and communication capabilities make their free movement safe and manageable. Detailed route planning and scheduling can guarantee that the vehicles keep a safe distance in time and space. A recent challenge of electric AGVs is that their charging may take several hours, which must be factored into their schedule. This has made minimal energy demand a key objective alongside earliest delivery and strictly meeting the deadlines. This paper presents a method for detailed routing and scheduling of AGV fleets to minimize energy consumption while considering battery levels and charging times. The optimization method is illustrated by a case study where multiple delivery tasks are performed by synchronized movement of vehicles on a complex warehouse layout. In the optimal solution, the scheduled waiting times for collision avoidance are utilized by the vehicles to pre-charge their batteries.

1. Introduction

The routing and scheduling of Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) involve two major problems that must be solved. The first problem is how to find a safe route in the physical environment for each transportation task. The second issue concerns the economic and ecological objectives of fleet management by an organization.

Nishi and Maeno [1] proposed a Petri Net (PN) decomposition method to optimize route planning for AGVs in semiconductor fabrication bays. The approach involves breaking down the PN into independent subnets and using a penalty function algorithm with a shortest path method to find near-optimal solutions. While computational experiments show significant reductions in computation time, the method’s performance depends on subnet selection, and future research will focus on handling real-time constraints and uncertainties.

A heuristic algorithm was presented by Fan et al. [2] for multi-AGV path planning in logistics centers, aiming to maximize sorting throughput by identifying conflict-free time windows along paths. Compared to methods like Hierarchical Task Network (HTN) and Time-Windowed A* (TW-A*), the proposed approach improves transportation efficiency with fewer path-finding failures, and future work will address multi-destination path planning for AGVs.

Zhang et al. [3] presented a collision-free routing method for Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) in an automated warehouse using a grid-based environment divided into five areas. The server detects potential collisions by comparing workstation IDs and time windows, classifying them into four types, and providing three solutions: selecting alternative routes, delaying AGVs, or modifying routes. Case studies show that this approach, which incorporates an improved version of Dijkstra’s algorithm and new collision types based on AGV status, increases the efficiency of multi-AGV systems.

Yuan et al. [4] introduced a bi-level path planning algorithm to optimize Multi-Automated Guided Vehicle (MAGV) routing and reduce path conflicts. The first level uses an improved A* algorithm for global path optimization on a topology map. In contrast, the second level applies a dynamic Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithm with kinematic constraints to avoid collisions locally. The simulation results show that the algorithm significantly improves search efficiency and reduces AGV path conflicts compared to Dijkstra and classic A* algorithms.

To address the scheduling and path planning challenges of AGVs in container terminal operations, Su [5] developed a two-level planning model to minimize task completion time and travel distance while resolving potential path conflicts. A bi-level algorithm that uses an enhanced Genetic Algorithm (GA) for scheduling and a Dijkstra-based approach for conflict-free path optimization is tested through case studies.

Barak et al. [6] launched a novel multi-objective scheduling model for resource-constrained Flexible Manufacturing Systems that addresses machine loading and unloading, operation scheduling, machine assignment, and AGV scheduling, emphasizing energy efficiency and sustainability. The proposed solution, utilizing a Modified Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (M-MOPSO) algorithm, outperforms the classic Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) in solving the scheduling problem, as validated through multi-criteria decision-making and performance metrics.

Xin et al. [7] presented an energy-efficient path-planning problem for AGVs that optimizes both vehicle speed and conflict-free paths using a Flexible Time-Space Network (FTSN) framework. The proposed hybrid metaheuristic method reduces kinetic energy consumption by approximately 10% without compromising transport productivity, offering significant benefits for cleaner production in flexible manufacturing and smart logistics systems.

Zhou et al. [8] introduced a novel AGV scheduling model that incorporates charging constraints to minimize energy consumption costs in automated ports, utilizing a Large Neighborhood Search (LNS) algorithm to solve the problem. Numerical experiments at a large port in China highlight the importance of strategically placing charging areas based on task sizes, offering valuable insights for optimizing AGV operations in container terminals.

To simultaneously account for time constraints, energy management, and sustainability objectives, a highly versatile optimization method is needed. The P-graph framework is a robust methodology designed to address complex optimization challenges across various domains, including vehicle assignment, battery management, and multi-site mission scheduling [9]. This versatile framework can simultaneously manage time, cost, and sustainability aspects within processes, making it a comprehensive tool for improving operational efficiency across multiple fields. By leveraging Process-Network Synthesis (PNS), the P-graph framework integrates various decision-making criteria. It provides both optimal and suboptimal solutions, which are ranked based on diverse factors such as cost, emission, and time constraints.Reference [9] introduced a vehicle assignment optimization method within this framework, focusing on minimizing cost and emissions in transportation tasks. Using the P-graph methodology, they generated alternative solutions ranked by criteria, such as cost and environmental impact, showing how different priorities can affect the outcome. Their approach demonstrates that vehicle assignments can vary significantly depending on the objective, emphasizing the need to consider multiple solutions to enhance decision-making in transportation logistics.

Expanding on that study, Bertok and Bartos [10] applied the P-graph framework to optimize energy distribution in isolated microgrids, especially in regions not connected to the national grid. This methodology efficiently manages the distribution of energy generated from solar power, stored in batteries, and supported by diesel generators. The approach balances the needs of energy producers, storage systems, and consumers while accounting for sustainability. By generating preliminary estimates of energy balances and offering real-time control, the method enhances resource utilization, reduces environmental impacts, and improves consumer satisfaction, ultimately laying the groundwork for future energy distribution systems.

Frits and Bertok [11] further expanded the P-graph framework application by adapting it to address large-scale field service operations through the Time Constrained Process-Network Synthesis (TCPNS) model. This two-level optimization model first assigns tasks to service groups based on availability and capacity and then refines task scheduling and route planning with minute-level precision. The iterative TCPNS method is highly efficient, enabling it to schedule thousands of tasks and optimize routes for numerous service groups, all within a short processing time. This allows organizations to handle complex field operations, prioritize tasks, and improve overall service delivery.

The review of previous work on AGV optimization shows that there have been tangible achievements in finding the shortest paths or minimizing time for travel or task completion [1,2,5] and collision prevention [3,4,5]. Energy issues of AGV management were accounted for in [6] without demand management. Path routing achieving a certain energy use reduction has been reported in [7], and in [8], charging constraints were used to achieve energy minimization. Previous methods based on the P-graph framework have addressed vehicle assignment for minimizing cost and emissions [9], efficient electrical grid management [10], and time-constrained processing networks [11]. While those works provide strong achievements and elements of solving the current problem, they cannot be directly applied to the management of AGV systems for the minimization of their energy consumption. The current work sets out to optimize the planning of AGV systems in terms of complete AGV missions with minimal energy demands. The proposed method leverages the P-graph framework as a basis. This framework is a powerful and adaptable toolset that integrates various optimization challenges across vehicle assignment, energy management, field operations, and supply chains. It offers a systematic approach to handling complex tasks by considering time, cost, and sustainability, thus enhancing decision-making and operational efficiency across diverse industries.

Table 1 highlights a clear fragmentation in the existing literature: most studies address only a subset of the decision layers required for realistic industrial deployment. Collision avoidance and static or time-dependent routing are well covered, whereas dynamic routing (understood as online, execution-time replanning) and explicit energy management remain comparatively rare and are typically treated separately.

Table 1.

Comparative scoring of the reviewed literature (ordered as in the reference list).

To facilitate a consistent and fine-grained comparison across the reviewed studies, each paper is rated on a four-level ordinal scale (0–3) for five methodological dimensions: collision avoidance/monitoring, trajectory/kinematics, dynamic routing, transport scheduling (job–time–vehicle), and energy management. A score of 0 indicates that the aspect is not addressed in the study. A score of 1 indicates that the aspect is only mentioned as background context and is not supported by a substantive mathematical or algorithmic model. A score of 2 indicates that the aspect is explicitly modeled via constraints or formulations (e.g., conflict constraints, kinematic limits, battery bounds), but it is not the primary optimization focus. A score of 3 indicates that the aspect constitutes a central contribution of the study and is addressed through dedicated algorithms or optimization methods and supported by experimental or quantitative evaluation.

The dynamic routing score is interpreted strictly as the capability for online or execution-time route replanning. Time-dependent routing, routing flexibility, or repeated offline re-optimization is not sufficient to achieve a high score in this dimension. Furthermore, an energy management score of 3 is assigned only if energy or battery charging is formulated as an explicit optimization objective or constraint set and is supported by numerical or experimental evaluation; purely cost-based or qualitative energy considerations are rated lower.

Several works achieve high scores in collision avoidance by means of time-window reservations or resource-based constraints (e.g., Nishi et al. [1], Fan et al. [2], Zhang et al. [3]), yet they largely rely on predefined routes or repeated offline planning. Similarly, path-planning-focused contributions (e.g., Yuan et al. [4], Xin et al. [7]) emphasize conflict-free routing and kinematic feasibility, but commonly assume fixed task assignments and omit vehicle-level dispatching and charging decisions. Conversely, scheduling-oriented studies (e.g., Barak et al. [6], Zhou et al. [8], Barany et al. [9]) provide strong formulations for job–time–vehicle assignment and, in some cases, energy-aware optimization, but treat vehicle movement through aggregated travel times rather than explicit routing or online replanning.

Against this backdrop, the proposed approach occupies a distinct position by simultaneously addressing all five dimensions evaluated in this review. In particular, it combines (i) collision avoidance embedded in a time–space representation, (ii) motion feasibility through trajectory-related timing constraints, (iii) dynamic routing via execution-time route adaptation, (iv) integrated transport scheduling at the mission level, and (v) explicit energy and charging management as part of the optimization model. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work in the reviewed set achieves a comparable level of integration across these layers within a single optimization framework.

This positioning is especially relevant for real-world AGV and electric forklift fleets operating under uncertainty, congestion, and battery limitations. By unifying routing, replanning, scheduling, and energy management, the proposed method closes a gap between theoretically sound planning models and the operational requirements of industrial intralogistics and terminal environments.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 defines the AGV routing and scheduling problem, including mission deadlines, energy consumption, battery constraints, and collision-free operation. Section 3 presents the proposed P-graph-based methodology for route generation and time scheduling while considering energy and charging aspects. Section 4 illustrates the approach through a warehouse case study. Section 5 summarizes the main results and discusses the benefits of the proposed method, and Section 6 outlines directions for future research, with a focus on advanced trajectory planning.

2. Problem Definition

This work addresses the integrated routing, scheduling, and energy management problem of an AGV fleet operating in a warehouse environment. The objective is to execute a set of transportation missions in a collision-free, energy-efficient, and deadline-compliant manner, while respecting the physical layout of the warehouse and the operational constraints of the vehicles.

2.1. Warehouse Environment

The warehouse layout is assumed to be known and consists of a set of functional elements, including:

- Loading and unloading points,

- Storage locations (bins or shelves),

- Charging stations,

- Transportation aisles connecting these locations.

AGVs navigate the warehouse using indoor localization and are capable of moving between any two connected locations via feasible paths along the aisles. The layout implicitly defines a set of spatial regions whose simultaneous occupation by multiple AGVs may lead to unsafe situations. Therefore, vehicle movements must be scheduled in such a way that conflicting spatial usage is avoided at all times.

2.2. AGV Fleet

The AGV fleet is denoted by

Each vehicle is characterized by its initial position, maximum velocity , maximum acceleration , battery capacity , and initial battery energy . The travel time and energy consumption of a movement depend on the distance traveled and the dynamic properties of the vehicle.

2.3. Transportation Missions

Let

denote the set of transportation missions. Each mission is defined by:

- An origin location (e.g., a loading point or storage bin),

- A destination location ,

- A strict deadline .

The execution order of missions is not predefined, and it is not required that all missions be completed. However, any completed mission must satisfy its deadline.

2.4. Movement Activities

Let denote the set of feasible movement activities. Each activity represents a vehicle movement between two connected locations in the warehouse and is associated with:

- A traversal time for vehicle v,

- An energy consumption .

Some pairs of activities are mutually exclusive in time due to spatial conflicts and cannot be executed simultaneously by different vehicles.

2.5. Decision Variables

The optimization problem is formulated by the following decision variables.

Vehicle assignment

Activity execution

Mission completion indicator

Start times

Charging time

Makespan

2.6. Constraints

Each mission is assigned to at most one vehicle:

A mission can only be completed if it is assigned to a vehicle:

If a mission is assigned to a vehicle, all activities required to complete that mission must be executed by the same vehicle:

where denotes the set of activities associated with mission m.

Precedence relations between consecutive activities must be respected:

for all consecutive activities , where is the length of the time horizon, i.e., a number large enough to exceed all deadlines:

Each completed mission must satisfy its deadline:

where denotes the final activity of mission m.

For any pair of activities that require exclusive access to the same spatial region, at most one of them may be executed at a time:

for all vehicles .

For each vehicle, the total energy consumption of the assigned activities must not exceed the available battery energy:

where denotes the charging rate of vehicle v.

Charging can only occur at designated charging stations and within a bounded time:

2.7. Objective Function

The primary goal is to maximize the number of completed transportation missions:

Among all solutions completing the maximum number of missions, minimize the total energy consumption of the AGV fleet:

Finally, the makespan of the resulting schedule is minimized.

To combine the above objectives into a single scalar objective function, a weighted-sum formulation is applied:

where A, B, and C are non-negative weighting constants that control the relative importance of mission completion maximization, energy consumption minimization, and makespan minimization, respectively.

The solution yields a conflict-free and time-feasible execution plan specifying the assigned vehicle, route, and exact start time for each completed transportation mission and associated movement and charging activity. The resulting schedule can be visualized using directed graphs, warehouse layout overlays, or Gantt charts.

3. Methodology

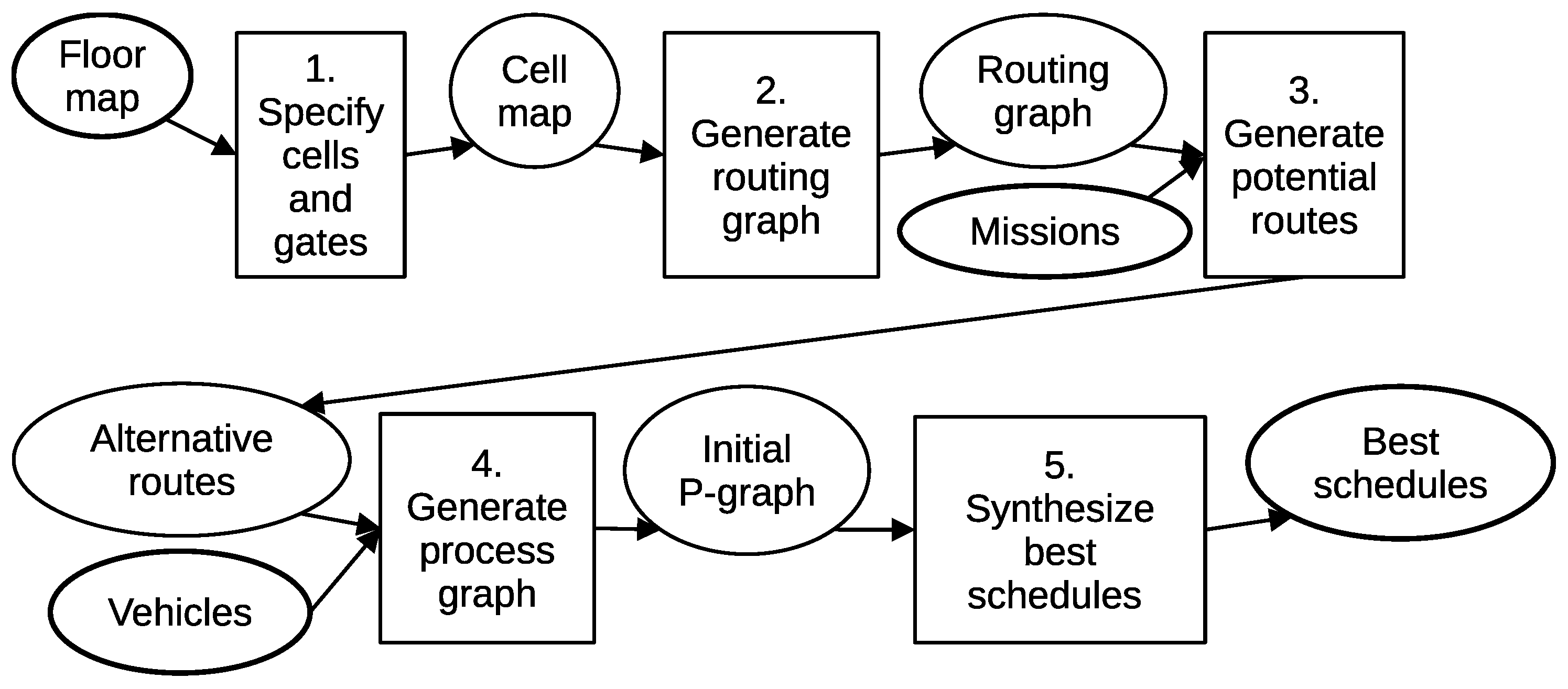

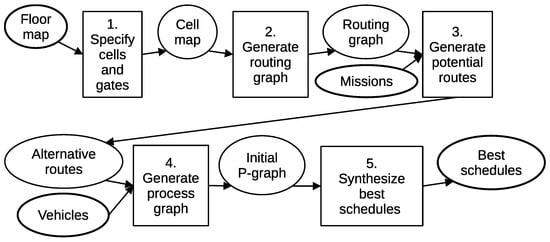

This section presents the proposed methodology for the integrated routing, scheduling, and energy-aware planning of AGV operations in a warehouse environment. An overview of the main modeling and optimization steps is illustrated in Figure 1, while the individual components of the method are detailed in the subsequent subsections.

Figure 1.

Steps of the solution method with their inputs and results.

The methodology starts from a geometric abstraction of the warehouse layout, which is introduced to enable safe and conflict-free vehicle movements. The floor plan is decomposed into spatial regions that can be occupied by at most one AGV at a time, and within these regions, transit points and points of interest are identified to represent feasible entry, exit, and service locations. This spatial representation provides the foundation for defining mutually exclusive movement areas and for estimating travel times in a consistent manner.

Based on the identified transit points and points of interest, a routing graph is constructed that captures all feasible movements of the vehicles within the warehouse. The edges of this graph correspond to executable movements, whose traversal times are estimated using vehicle-specific trajectory planning that accounts for kinematic constraints such as maximum velocity and acceleration. Note that the trajectories are not fixed a priori but can also be part of the optimization, assuming that vehicles can move freely within a spatial region. In this paper, the calculation of a feasible trajectory is presented; however, due to its complexity, the determination of the optimal trajectory via an optimization model will be the subject of a subsequent publication. To provide sufficient flexibility for scheduling, multiple alternative routes are generated for each transportation mission, rather than restricting the solution space to a single shortest path.

The routing alternatives are then translated into an initial process structure, where each movement along a route is represented as an activity. This process structure is formulated in the parlance of Time-Constrained Process Network Synthesis (TCPNS), in which AGVs and shared spatial regions are modeled as resources. Within this representation, activities can only be executed if the required resources are available, which naturally enforces vehicle availability and mutual exclusion of conflicting movements.

The TCPNS-based model enables the simultaneous assignment of vehicles to transportation tasks, the selection of routes, and the determination of an exact execution schedule. In addition to routing and collision avoidance, the model explicitly incorporates energy-related constraints. The energy required for vehicle movements is estimated based on the selected routes, and the current battery state of each AGV is taken into account during scheduling. Furthermore, optional charging operations can be inserted into the schedule, allowing vehicles to increase their available energy before executing transportation tasks.

As a result, the proposed methodology produces a time-feasible, collision-free, and energy-aware execution plan for the AGV fleet. The detailed modeling steps underlying this approach are presented in the following subsections, covering floor map abstraction, routing graph generation, trajectory and time estimation, TCPNS-based process modeling, multi-AGV coordination, and battery charging management.

3.1. Modeling the Floor Map

The floor plan is segmented into adjacent cells. For safety reasons, only one vehicle may stay in each cell at a time. The cells are required to be convex so that each point can be reached in one turn from any other point, regardless of the vehicle’s initial orientation. Assuming convex cells simplifies trajectory planning and travel time estimation.

Although efficient algorithms are available for convex decomposition [13], the resulting cells are often counterintuitive and difficult for users to interpret. Therefore, practitioners prefer user-defined cells. This approach enables automated trajectory generation while the effort required for cell definition is substantially lower than that of manual trajectory planning.

Cell boundaries can represent physical objects, such as walls or shelves, that cannot be crossed. Transit points are defined for each possible crossing. These points can be doors, gates, or points where vehicles stop waiting for the other vehicle to leave the cell ahead. If they are equally usable, a cell can have multiple points of interest, such as several storage slots, conveyors, or charging stations. However, it is assumed that at most one of them is visited in each mission. During the mission, a vehicle goes there from a gate and continues to another gate.

If movement between more than one point of interest may be requested within a single cell in a mission, then the cell should be divided into several parts. According to the proposed method, movement is determined by process synthesis; trajectory generation is to be kept as simple and unambiguous as possible.

3.2. Generation of the Routing Graph

The routing graph is constructed by adding nodes and edges. Nodes represent exactly the transit point between cells and all the points of interest of the actual missions, including the actual locations of the vehicles.

Edges are generated by connecting nodes. In each cell, each transit point is connected to any other, and each point of interest is connected to the other transit point. The edges represent a potential two-way movement; each edge can be traversed in both directions.

A typical interpretation of involving an edge from a transit point to a point of interest and one from the point of interest to another transit point in the route graph is that the vehicle enters the cell at the transit point, visits the point of interest for some reason, and leaves the cell through the other transit point. The weight of an edge is the estimated duration of the vehicle between the nodes connected by the edge. The duration of the movement is estimated by trajectory planning.

Trajectory Planning and Travel Time Estimation

The purpose of trajectory planning is to provide an executable movement for each candidate vehicle between two points in a cell. Furthermore, based on the characteristics of the vehicle, it can estimate the duration of the movement. This requires the value of the maximum acceleration and maximum speed or speed limit for the vehicle.

Each edge on the routing graph represents a movement by a specific vehicle. Different routing graphs are generated for vehicles with different properties.

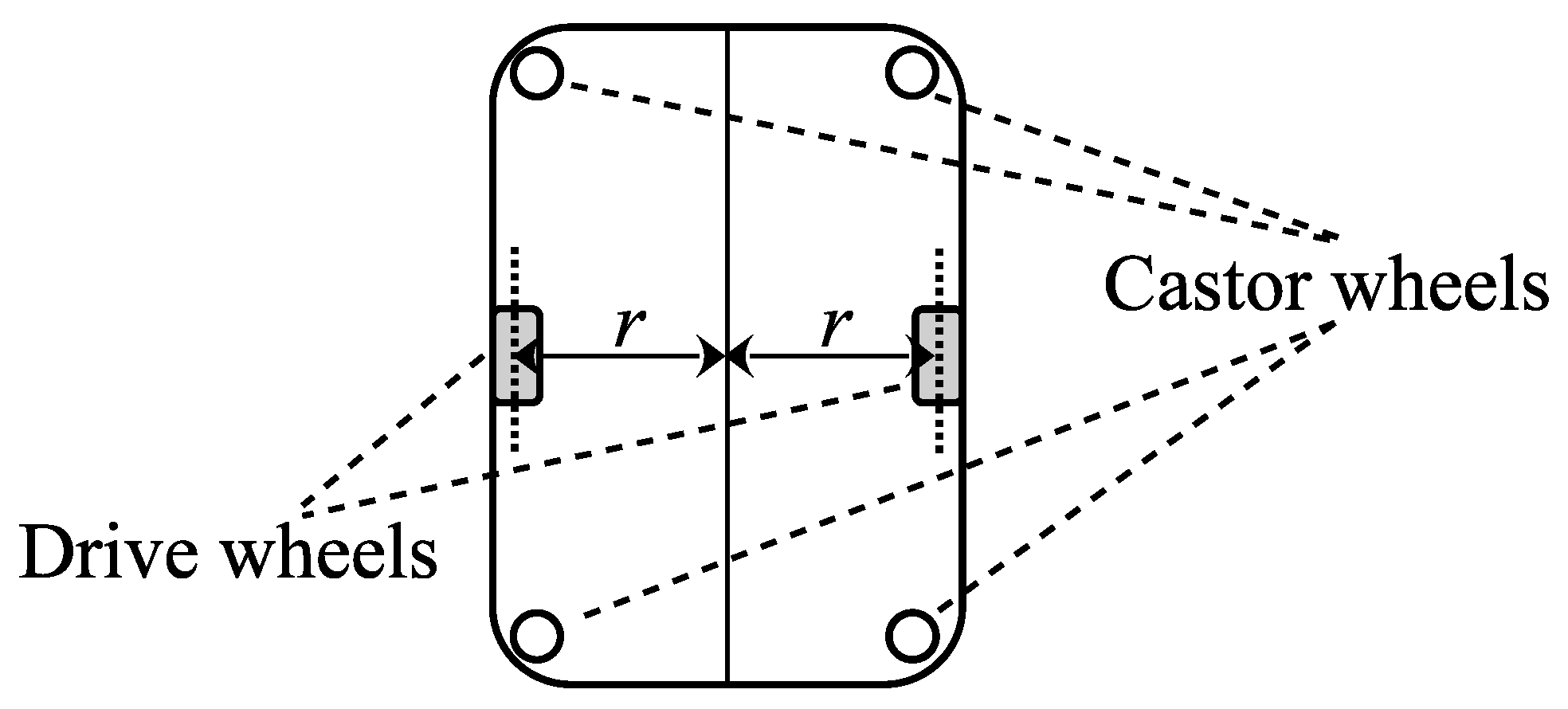

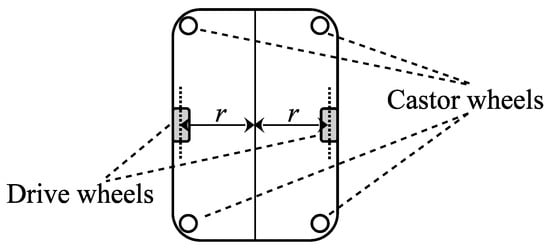

In the present implementation, it is assumed that each vehicle

- Delivers its shipment aligned to the center of its top,

- Is able to rotate around its center, and

- Is symmetrical in its direction of travel, so it does not have to turn around after picking up the shipment.

As an example, see the differential drive moving a turtle-type AGV depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

AGV with 2 differential drive wheels and 4 castor wheels.

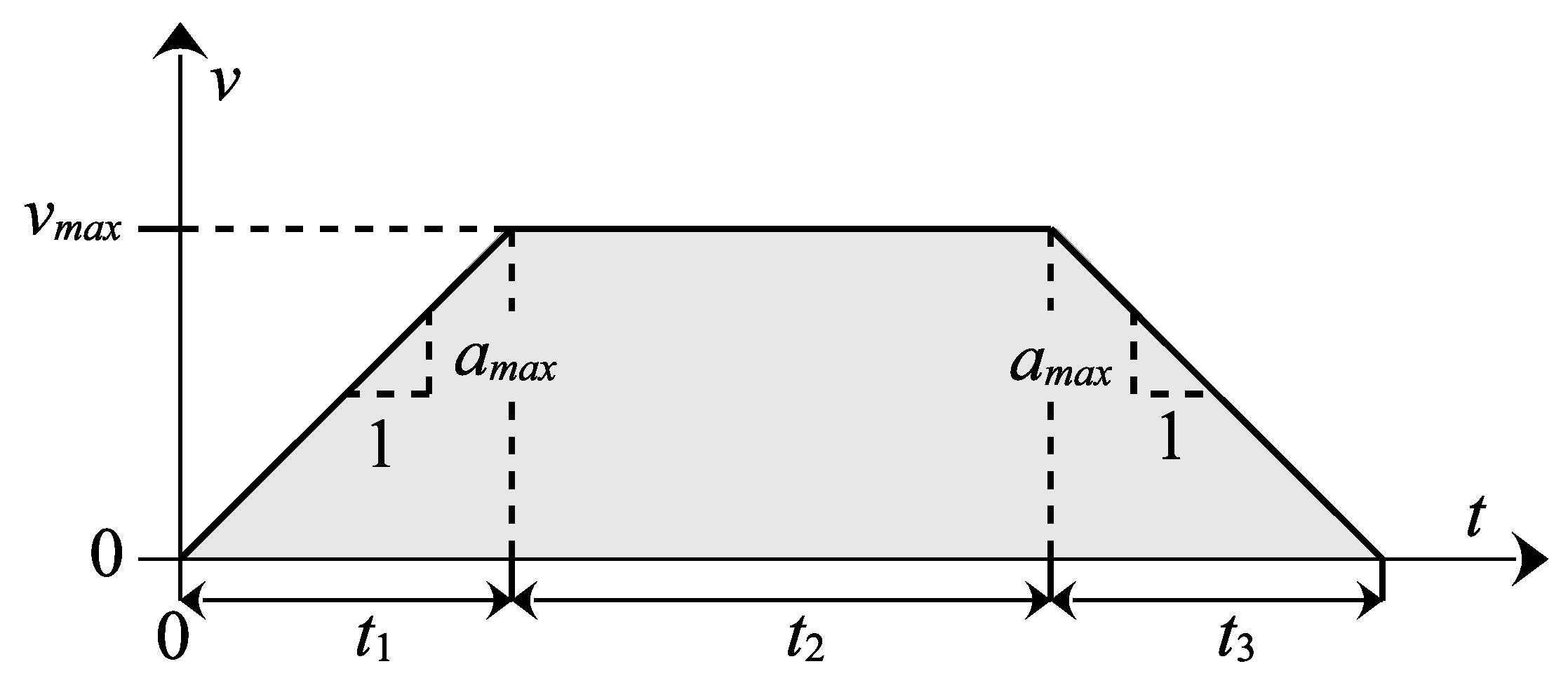

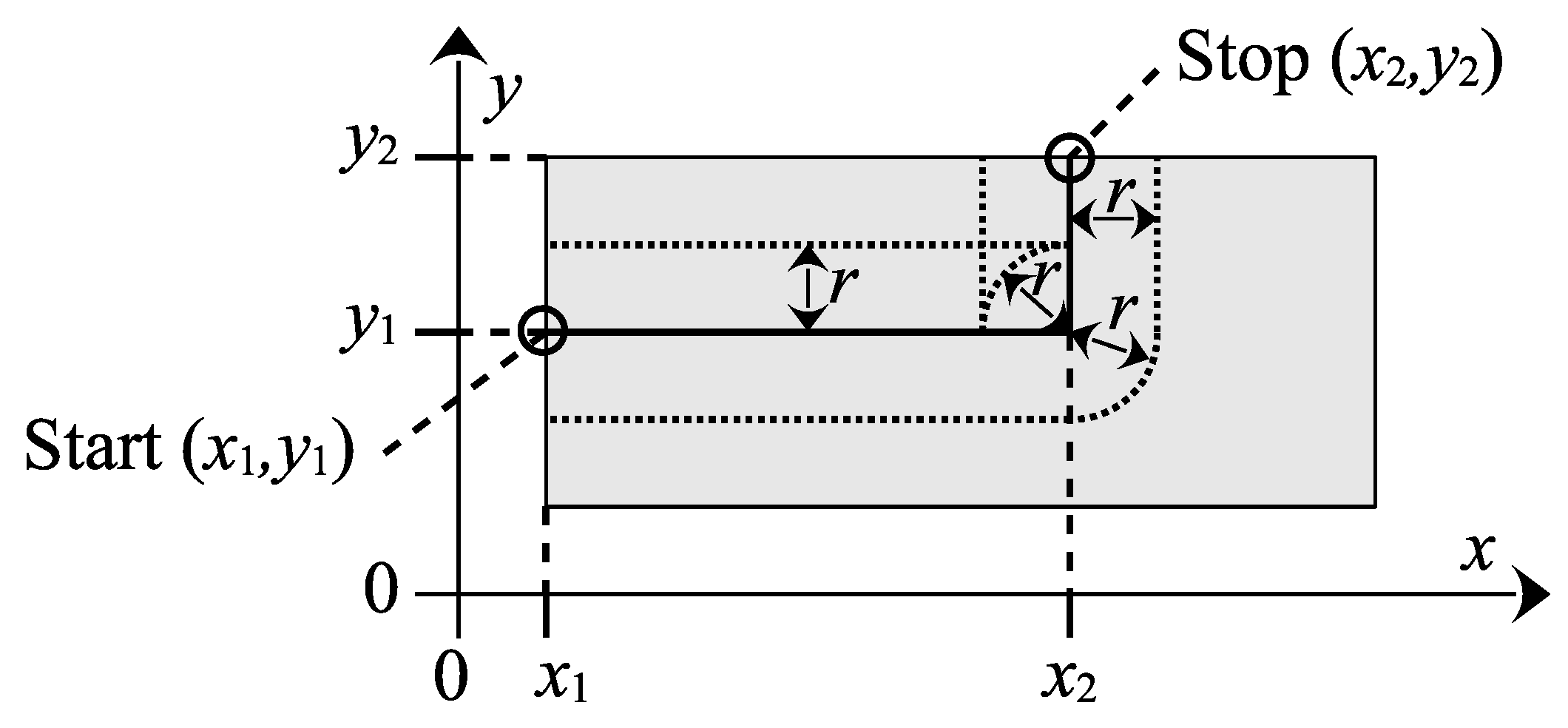

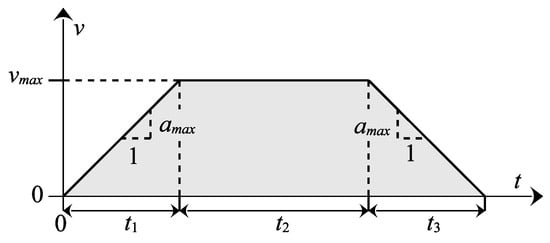

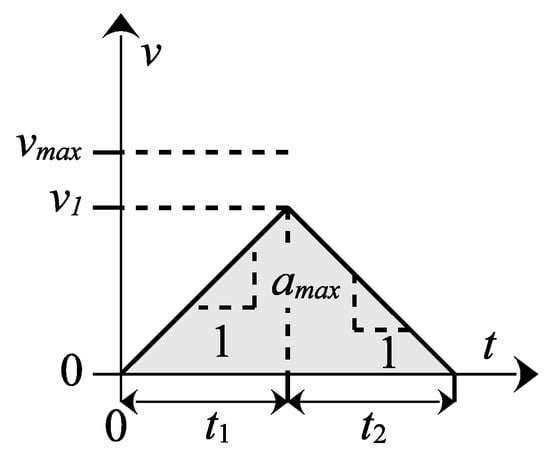

In order to estimate the time required to move between two points, as in Case 1, it is assumed that the vehicle starts from a standstill and accelerates as quickly as possible until it reaches its maximum speed. Subsequently, it decelerates at its maximum rate until it comes to a complete stop at the destination (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Case 1: Acceleration to maximal speed and deceleration until reaching the target.

In this case, the duration can be calculated as

and the corresponding traveled distances are given by

Note that Case 1 is only applicable if there is sufficient distance to reach the maximum speed, i.e., . Thus, the total traveled distance can be written as

from which the cruising distance follows as

The corresponding cruising time is then given by

Thus, the total travel time in Case 1 becomes

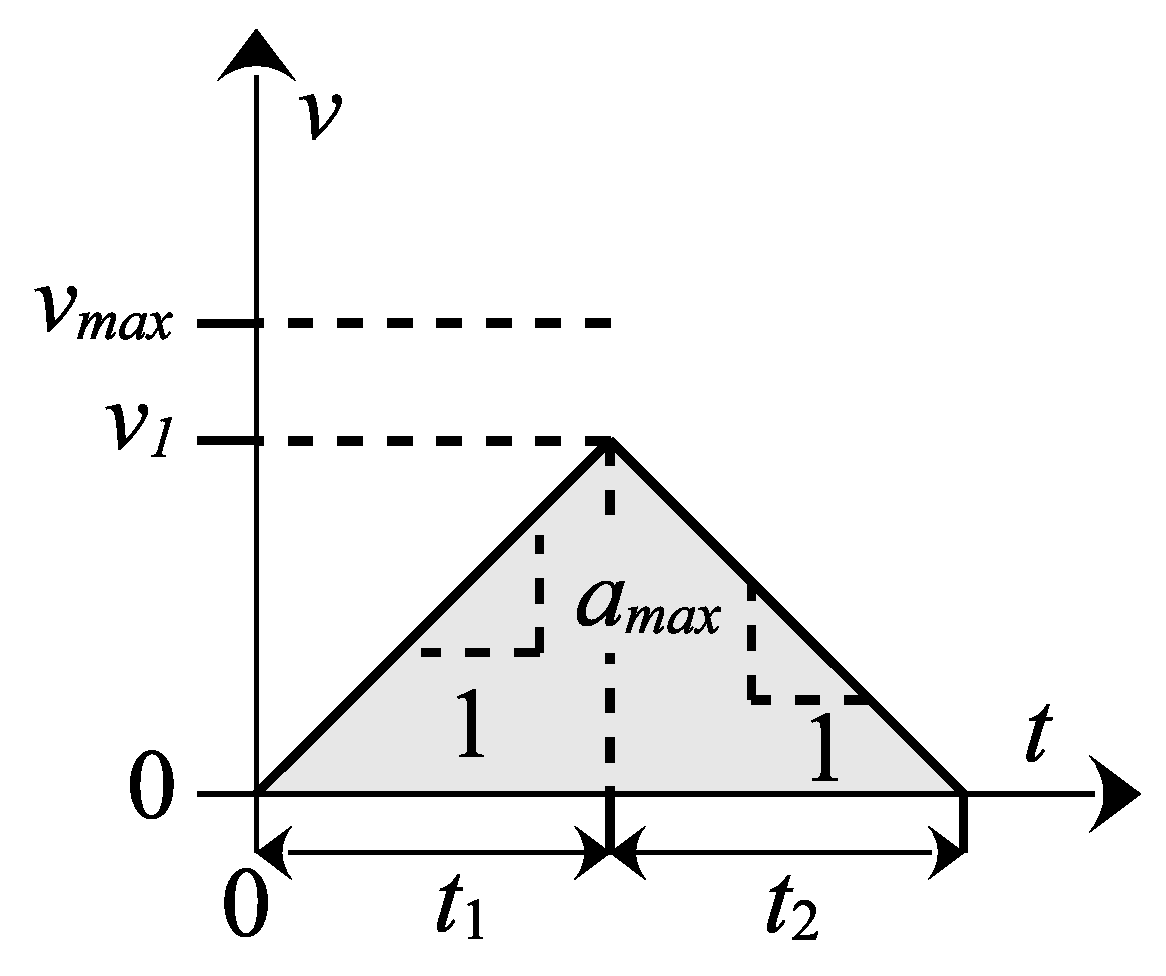

If there is insufficient distance for the vehicle to accelerate to its maximum speed and decelerate to a stop before reaching the destination, i.e., if , the motion consists only of an acceleration and a deceleration phase, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Case 2: Acceleration and deceleration without reaching the maximal speed.

This corresponds to Case 2, for which the acceleration and deceleration times are equal and can be written as

The total traveled distance is then given by

from which the duration of each phase follows as

Accordingly, the total travel time in Case 2 becomes

Consequently, the estimated travel time as a function of the distance s can be summarized as

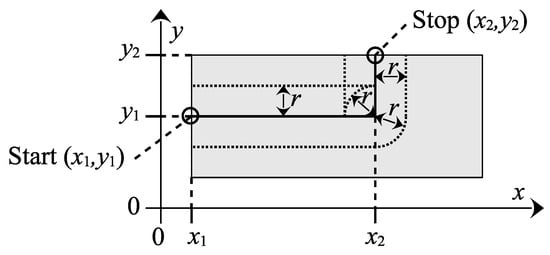

If the points marked on the floor plan require movement both parallel and perpendicular to the shelf rows, then the vehicle must turn; see Figure 5. With the help of the turning radius of the vehicle, the turning time can be calculated similarly to other movements, where .

Figure 5.

Movement of the AGV with 2-wheel differential drive inside a cell.

In summary, the total time required to move between two points and , while accounting for any necessary turns, can be expressed as

3.3. Generation of Potential Routes for Missions

Using Dijkstra’s algorithm, not only can the shortest path be generated, but by not stopping at the first solution, additional paths within a given tolerance can also be obtained. The route graph must include all movements that appear in at least one of the paths. Potential movements that are not included in any of the paths will not be included in the route graph either, thereby reducing the set of operations to be considered in process planning.

Note that the pathfinding process is aimed at mapping the environment, i.e., the locations near vehicles and goals, as well as the feasible transitions between them. Any individual step can be incorporated into any schedule during the final optimization phase. Thus, pathfinding is not a direct determination of vehicle motion but a pre-screening tool used to identify candidate actions and reduce the search space, effectively mitigating the complexity of the forthcoming scheduling and routing problem.

3.4. Generation of the Initial Process Graph

The concept of Process Network Synthesis (PNS) was introduced by Ferenc Friedler, L. T. Fan, and their collaborators in 1992 as a systematic methodology for the design of chemical process systems [14,15]. The primary objective of PNS is the exhaustive generation and evaluation of all feasible structural configurations that can be constructed from a given set of process building blocks. Due to the inherently combinatorial nature of the synthesis problem, the development of rigorous algorithmic methods was essential to mitigate the risk of suboptimal designs and to ensure the identification of globally optimal process structures.

In the formal framework presented by Bertok et al. [10], a synthesis problem is defined by the parameter tuple (, , , , , ). Here, the sets and denote the collections of actions, and the set of their preconditions and results, respectively. The set represents the available resources, while specifies the desired objectives of the process network.

According to the original formulation by Friedler and Fan, each input to an action is either a primary resource or the output of another action. Interconnections between actions are realized through intermediate entities, and actions and intermediates are strictly distinguished, ensuring a clear conceptual separation between process steps and material flows.

The function defines the set of prerequisites required for the execution of an action ,

where denotes the power set of . Similarly, the function specifies the set of outcomes produced by action ,

and therefore both the prerequisites and outcomes of any action are elements of the set of entities, i.e.,

This formulation implies that all preconditions and results associated with actions are treated uniformly as elements of . Furthermore, the available resources and the desired target products of the synthesis problem are also defined as subsets of the material set,

while it is required that the sets of resources and target products be mutually exclusive,

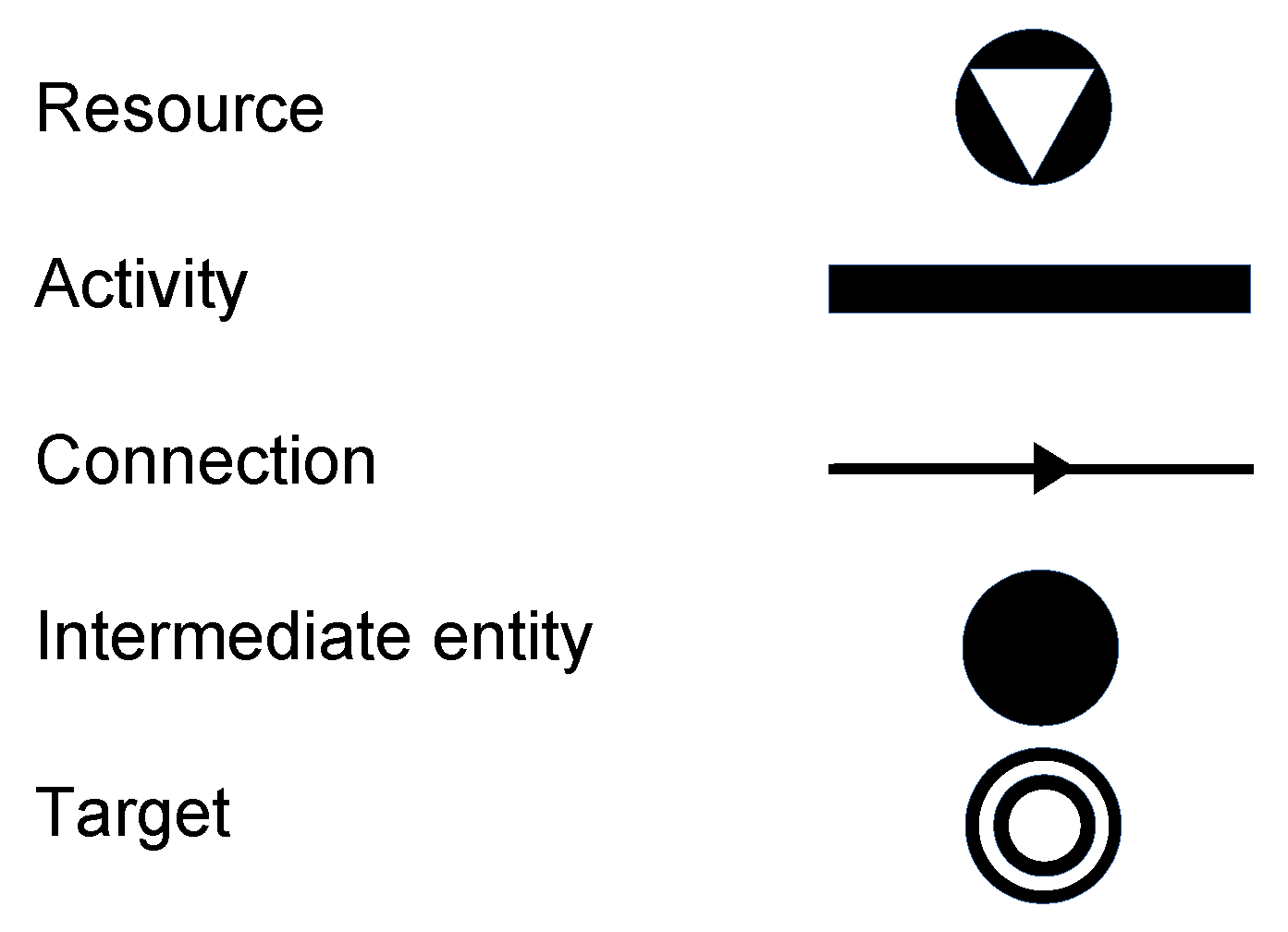

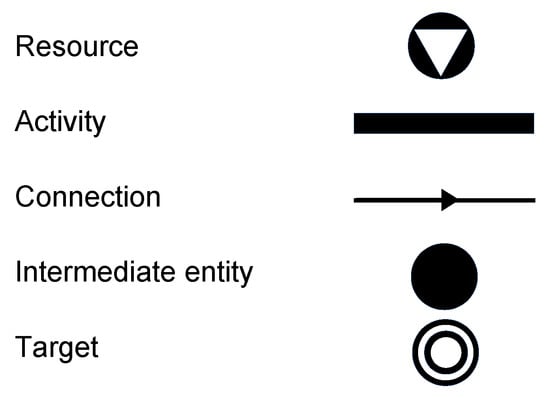

Figure 6 illustrates the graphical representation of nodes and arcs in P-graphs.

Figure 6.

Graphical representations of nodes and arcs of P-graphs.

P-graphs provide an intuitive and structured visual framework that supports the systematic formulation of process synthesis problems and facilitates the identification of all parameters relevant to optimization. Over the past decades, the PNS methodology has been successfully applied to a wide range of engineering optimization problems. A substantial portion of the reported applications focuses on energy-related challenges, as reflected in the extensive body of scientific literature. These include chemical reaction modeling by Mercado and Cabezas [16], energy network optimization by Niemetz et al. [17], district heating network design by Sandor et al. [18], and optimal carbon trading by How et al. [19], as well as the evaluation of energy supply options for manufacturing plants by Éles et al. [20].

In the last decade, the applicability of the PNS framework to business processes and supply chain systems has been examined. In such applications, not only the structural configuration of the process is of relevance, but also the execution times associated with individual activities. When certain activities can be reached through multiple alternative pathways, the synchronization of these branches becomes necessary. Moreover, beyond the overall execution time of the process, both the start times and durations of all individual activities must be explicitly specified. These requirements necessitate the direct incorporation of time parameters into the model, which led to the development of Time-Constrained Process Network Synthesis (TCPNS).

The introduction of additional parameters and time constraints in TCPNS enables the representation of processes as sequences of successive activities originating from an initial state. As a result, if a superstructure can be constructed that captures all feasible execution orders of process steps by different resources, scheduling problems can be effectively formulated and solved within the TCPNS framework.

The fundamental idea of applying the TCPNS framework to scheduling problems is that shared resources are explicitly represented within the process network. Each activity can only be executed if the required resource is available, thereby enabling the systematic modeling of resource-constrained scheduling and mutual exclusivity. Conceptually, a resource is represented by a token that moves along a path in the directed P-graph, where the nodes along this path correspond to the activities performed by the resource. The trajectory of the token defines the sequence of tasks, while its arrival time at a node determines the start time of the associated activity. The steps involved in constructing the superstructure used for solving scheduling problems are described in more detail in the work of Frits and Bertok [12].

Building upon the TCPNS framework, the methodology can be naturally extended to the modeling and optimization of automated material handling systems. In particular, the characteristics of TCPNS make it well-suited for addressing scheduling and routing problems that arise in the operation of AGV fleets.

AGVs are capable of autonomously transporting materials, products, and components between different locations within a warehouse environment, thereby significantly reducing the need for manual handling. Transport requirements specify both the origin and destination of materials, as well as the time windows within which transportation tasks must be completed. While individual transportation tasks are executed autonomously by the vehicles, the coordinated operation of an AGV fleet requires centralized optimization to ensure efficient task allocation and temporal synchronization. Such an optimization framework must account for current transport demands, the positions and capacities of available AGVs, and the traffic conditions characteristic of the warehouse layout.

The primary objectives of AGV fleet optimization typically include the minimization of total energy consumption and service time, which can be achieved by reducing waiting times, balancing the workload among vehicles, and preventing unnecessary detours. Although modern AGVs are capable of local collision avoidance, global efficiency can be further improved if routes and their intersections are planned in a manner that prevents vehicle encounters altogether.

In this work, the AGV routing and scheduling problem is formulated as a process network synthesis problem, in which feasible routes are generated and an exact execution schedule is constructed automatically. The resulting model is represented using the P-graph formalism, enabling the systematic exploration of alternative routing and scheduling solutions within a unified optimization framework.

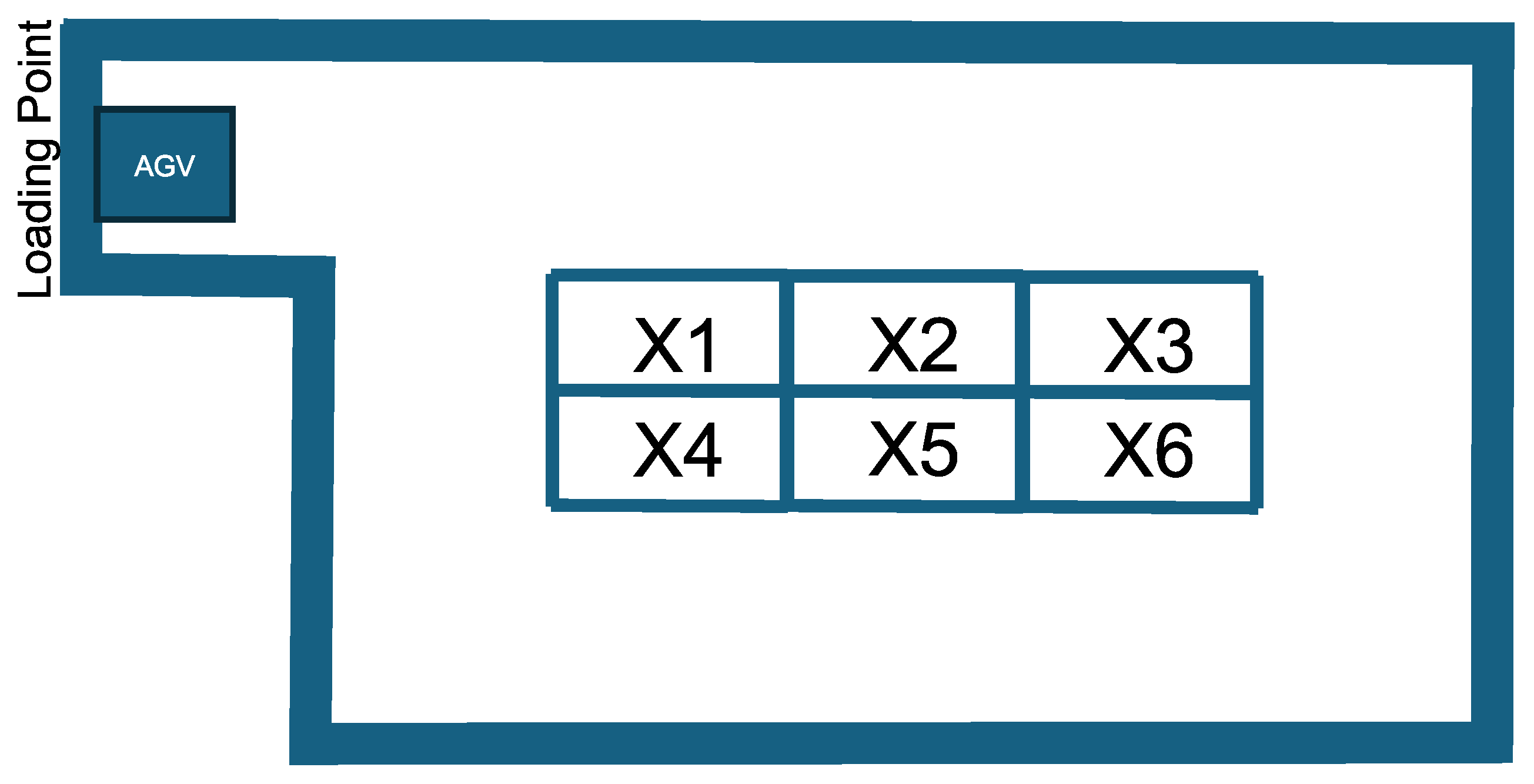

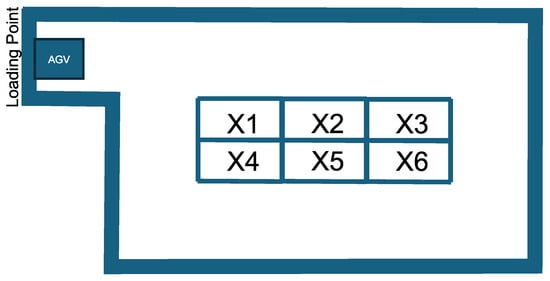

3.4.1. Managing the Warehouse Layout

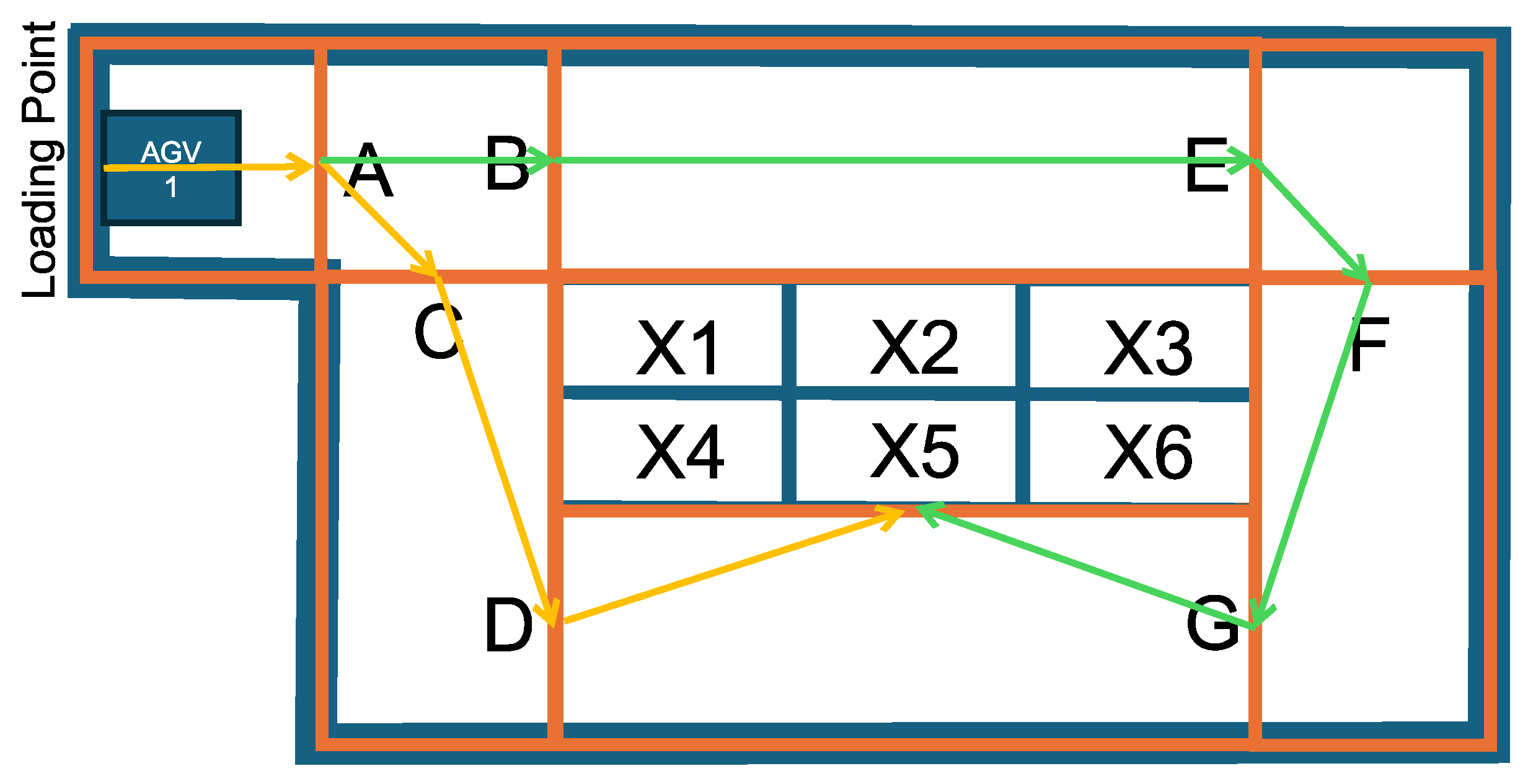

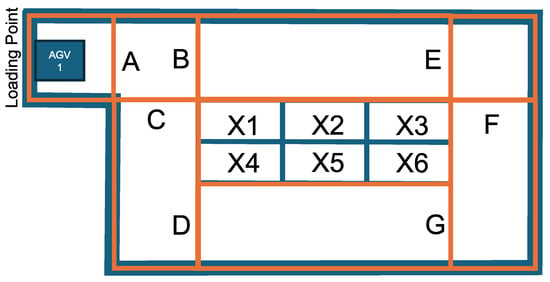

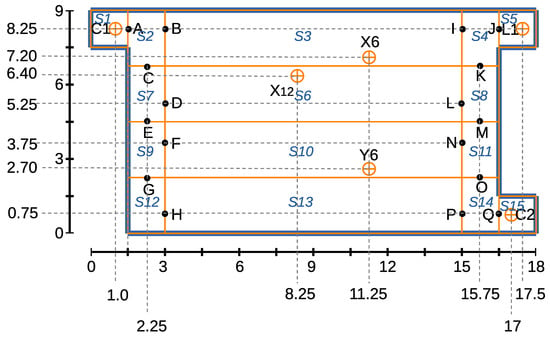

The layout of warehouses determines the locations of key transport points, such as loading and transfer points, as well as the shelves’ bin, which typically serve as the starting and ending points of transportation. AGVs travel the routes between these points, using indoor localization to navigate through any available spaces. To ensure the AGV fleet can be scheduled, it is necessary to define mutually exclusive areas that only one AGV can occupy at any given time; these areas are referred to as cells. In this approach, a route taken by an AGV can be viewed as a series of cells. The sample layout used in the section can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Example for layout: Loactions of the loading point and bins X1, X2, …, X6.

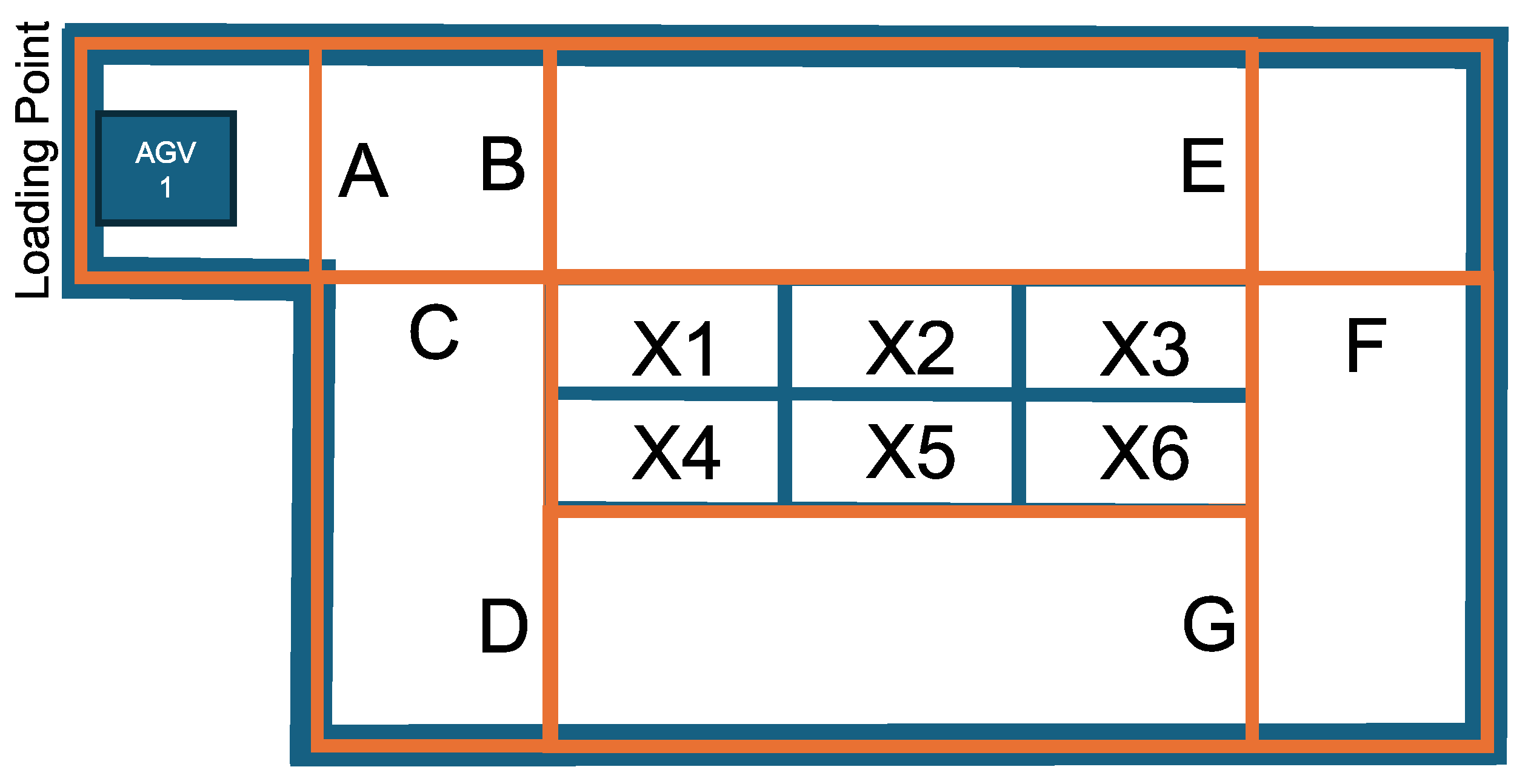

There is a loading point on the warehouse layout, which will currently also be the departure point for the AGV. In the middle, there is a shelf system with six bins. To model the routes, cells need to be defined, with two constraints: (1) the cell must be convex, and (2) the cells must fit together. In the example, square-shaped cells have been defined for simplicity and clarity, as shown in Figure 8. Each edge that is adjacent to two cells is assigned a unique ID, which is referred to as a gate. The gates help define the AGV’s path; for example, the cell ABC, in the upper left corner, allows multiple transit directions: A → B, A → C, B → A, B → C, C → A, C → B.

Figure 8.

Cells on the warehouse layout.

In the P-graph model, movements between these gates will be recorded as activity. In the case of movement between two cells, it is assumed that the exit gate of the cell always has an entry gate pair in the neighboring cell. For example, gate B can be an exit gate in cell ABC, while it serves as an entry gate in cell BE.

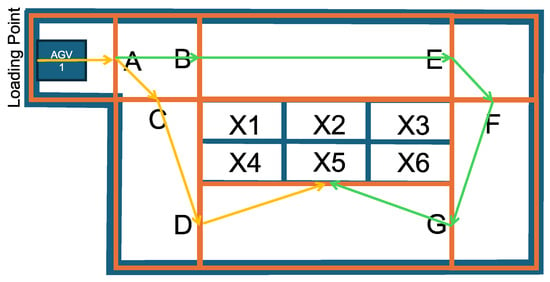

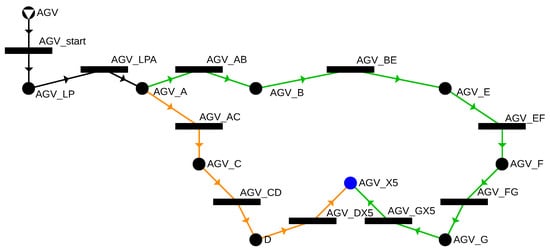

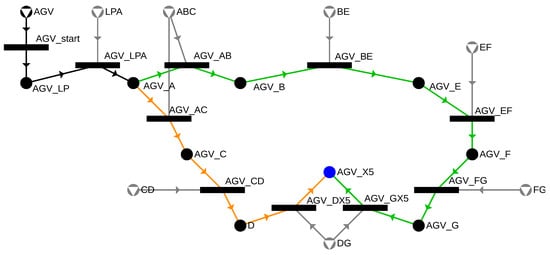

3.4.2. Modeling Possible Routes of AGVs

Using cells and gates, it is now possible to clearly define the routes. Consider an example where the AGV moves from the loading point (LP) to bin X5. Any general path-finding algorithm, such as the well-known Dijkstra algorithm, can be used to find the shortest path from LP to X5. Based on the previously defined gates, the shortest path is LP → A → C → D → X5. However, to provide more flexibility for the scheduling algorithm, several possible routes between the two points can be considered. Therefore, it is beneficial to use a path-finding algorithm capable of generating multiple alternative routes. In the current example, another possible route is LP → A → B → E → F → G → X5. These routes are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Possible routes between the loading point and the X5 bin.

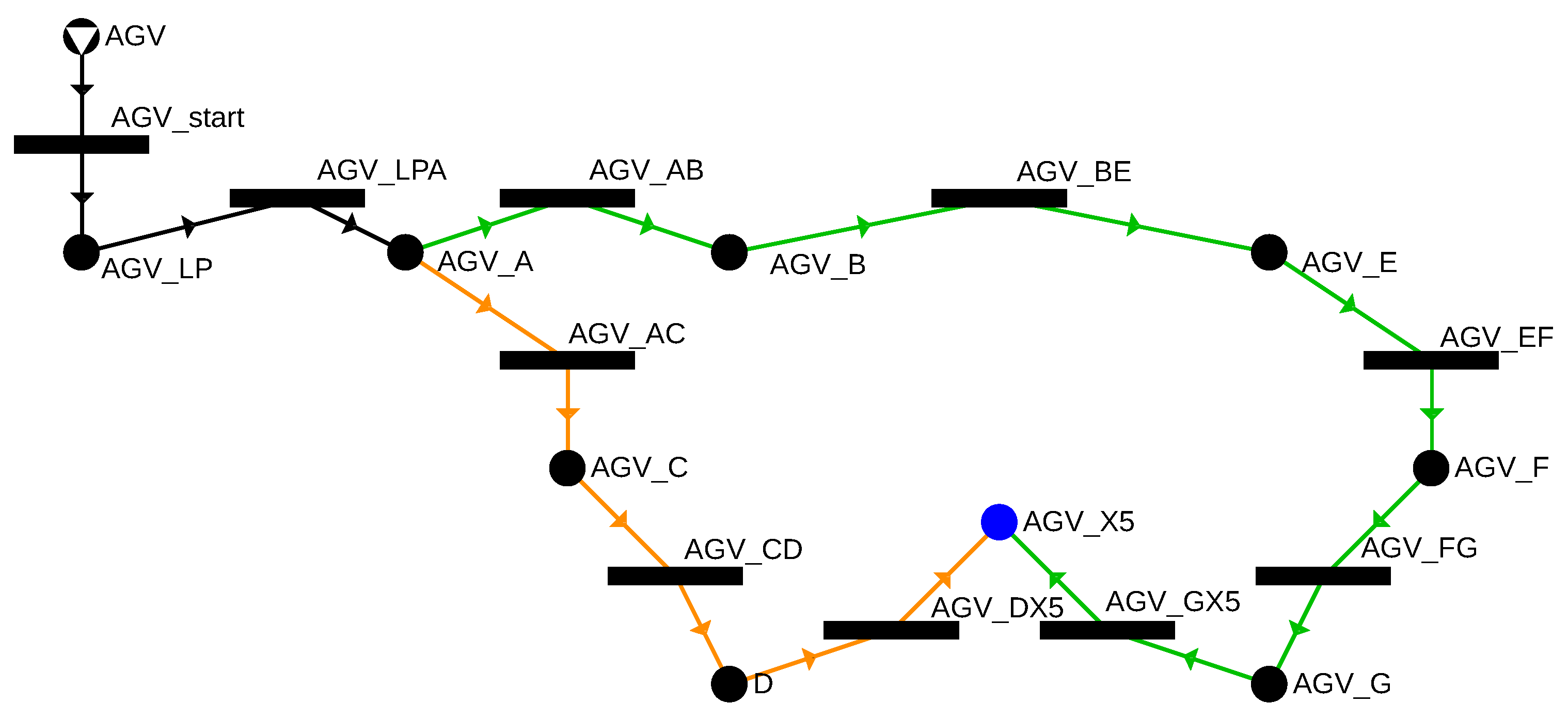

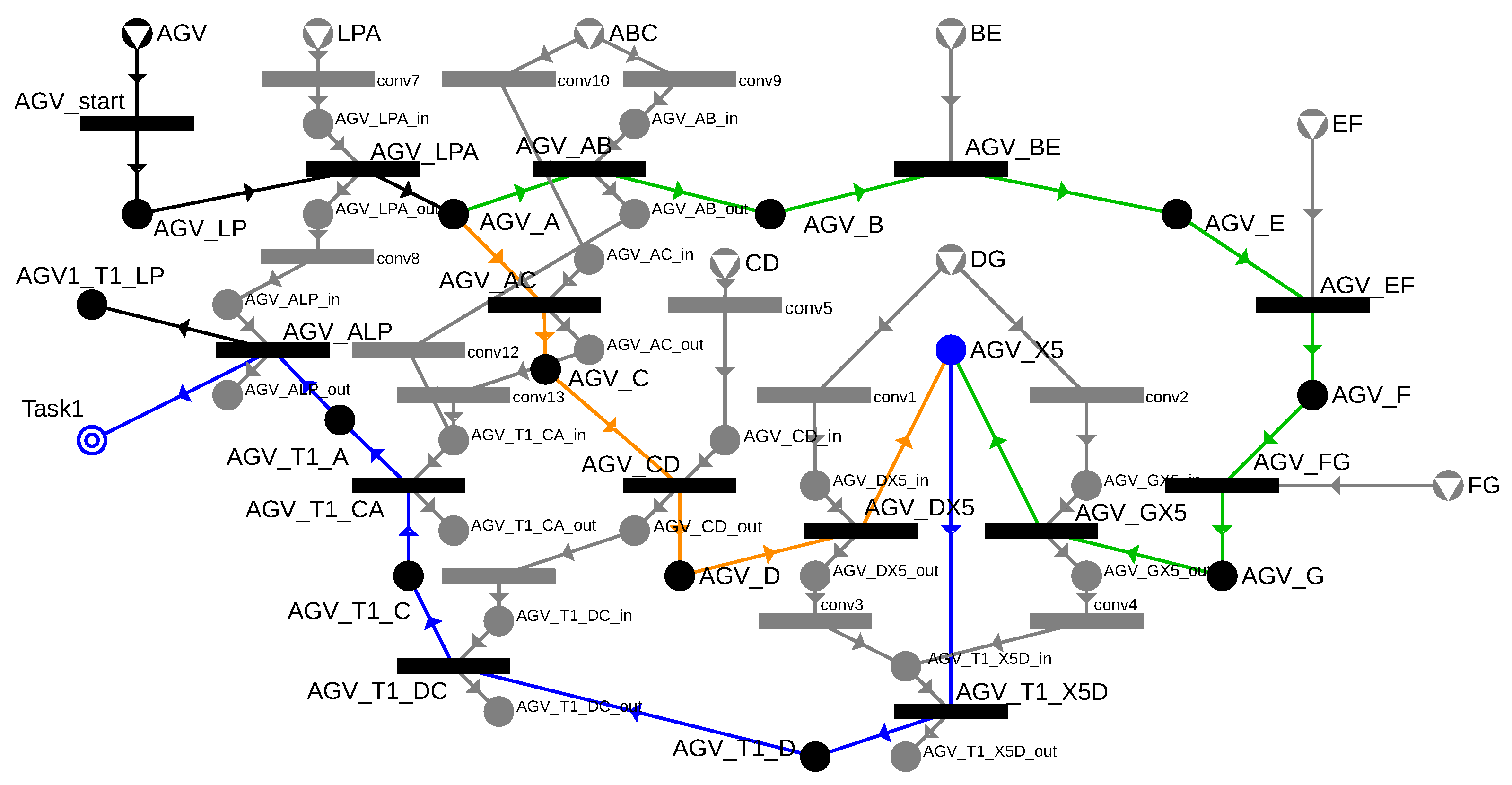

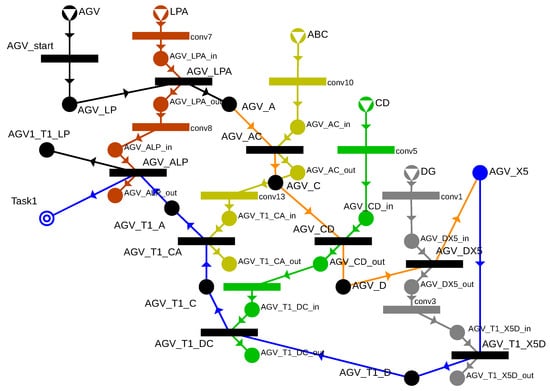

In the P-graph model, the AGV is represented as a resource, while the task to be performed is represented as a target. During modeling, a structure needs to be built that maps the movement of the AGV through the cells and gates while fulfilling the transportation demands, ensuring the exclusive use of each cell. The P-graph structure shown in Figure 10 includes the movements between gates that make the LP → X5 route possible. The yellow and green edges indicate the routes, where the preconditions and results of the activities depicted as solid circles represent that the AGV has reached a gate. For example, in the case of AGV_A, the AGV is at gate A. The activities depicted as horizontal bars describe the movement between two gates; for instance, AGV_AB connects gates A and B. For each movement activity, the time required to perform is assigned, which takes into account the cell’s geometry as well as the constraints on the AGV’s acceleration and maximum speed, based on the formulas described in Section “Trajectory Planning and Travel Time Estimation”.

Figure 10.

Two possible routes from the loading point to bin X5 denoted by green and orange arcs in the P-graph model.

It is important to note that during the generation of the P-graph model, only those routes that are actually necessary for fulfilling a transportation demand are included in the graph. Thus, the structure is dynamically updated according to the current demands.

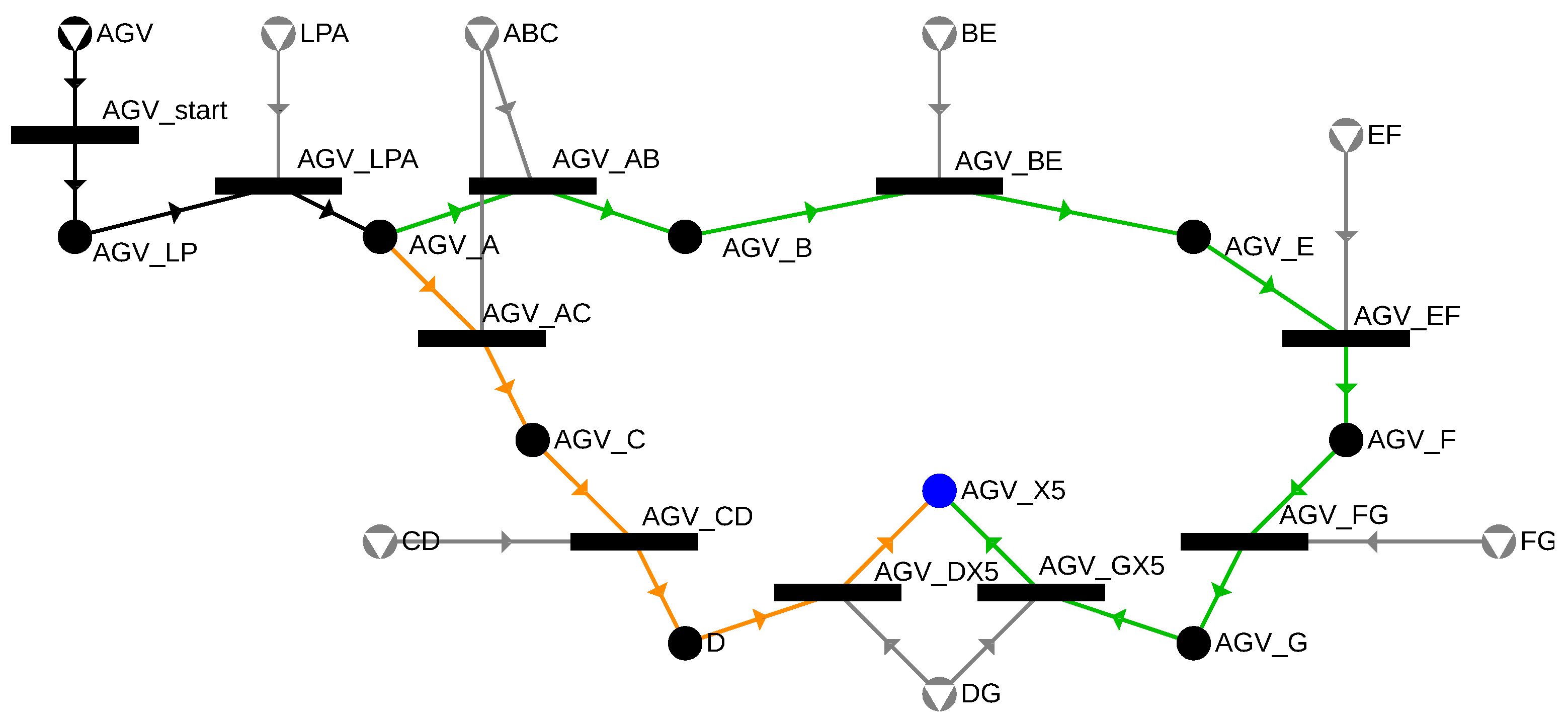

3.4.3. Modeling the Exclusive Use of Cells

The routes have already been included in the graph, but based on the initial condition, it must be ensured that only one AGV can occupy each cell at a time. To meet the condition, the previously defined cells are also added to the P-graph as resources, and for each movement, the availability of the cell containing the gates involved in the movement is assigned as a precondition. Exclusivity can only be guaranteed if there is exactly one unit available of these resources, and this unit is required for each movement. If a cell is associated with only one movement, this can be managed simply by a new edge, as seen with the cell BE, which is only connected to the AGV_BE movement. A similar approach can be applied to a cell that belongs to multiple movements, but only one of them can be included in the solution. For example, cell ABC is a precondition to both AGV_AB and AGV_AC movements, but the AGV in the example will choose only one route. The P-graph extended with cell handling related to the two possible routes is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

P-graph model extended by cells represented as resources in gray.

In this example, the AGV passes through each cell only once; however, in a general case, it may pass through the same cell multiple times, which also needs to be managed in the model. Let us consider an example where the good in bin X5 needs to be transported back to the loading point. In the TCPNS model, the start time for each node’s execution or its production during the process is determined. The MILP model generated based on the P-graph can only be solved if each node is touched only once in the solution structure. Therefore, when modeling a round trip (e.g., LP → X5 and X5 → LP), the nodes associated with the two routes must be treated separately, as their start times will differ. For this reason, it is necessary to extend the current example with the X5 → LP route, but this raises new questions regarding cell management. Figure 12 shows a detail from the extended model with the return route, where the handling of each cell is marked in different colors. It can be seen that the cell is first assigned to the route where the AGV is moving empty toward bin X5, and then a conversion operation allows it to be available for the movements marked in blue on the return route. To generalize this approach, a new precondition ({movement}_in) and result ({movement}_out) have been introduced for the movements, and conversion takes place between these nodes. For example, the ABC cell marked in yellow is required for both the A → C movement (AGV_AC) and the C → A movement (AGV_CA). First, the ABC cell is converted as a resource into the AGV_AC_in state, allowing the A → C movement to be performed. As a result, AGV_AC_out results, indicating that the cell can be reserved for another movement. For the reverse C → A movement, AGV_CA_in is converted from AGV_AC_out state, enabling the AGV_CA operation to be executed.

Figure 12.

P-graph representing cell-wise color-coded assignment operations in case of multiple passages.

This approach allows for handling cases where a large number of movements share a cell, such as multiple AGVs or a high number of transport demands, and also simplifies the model generation algorithm.

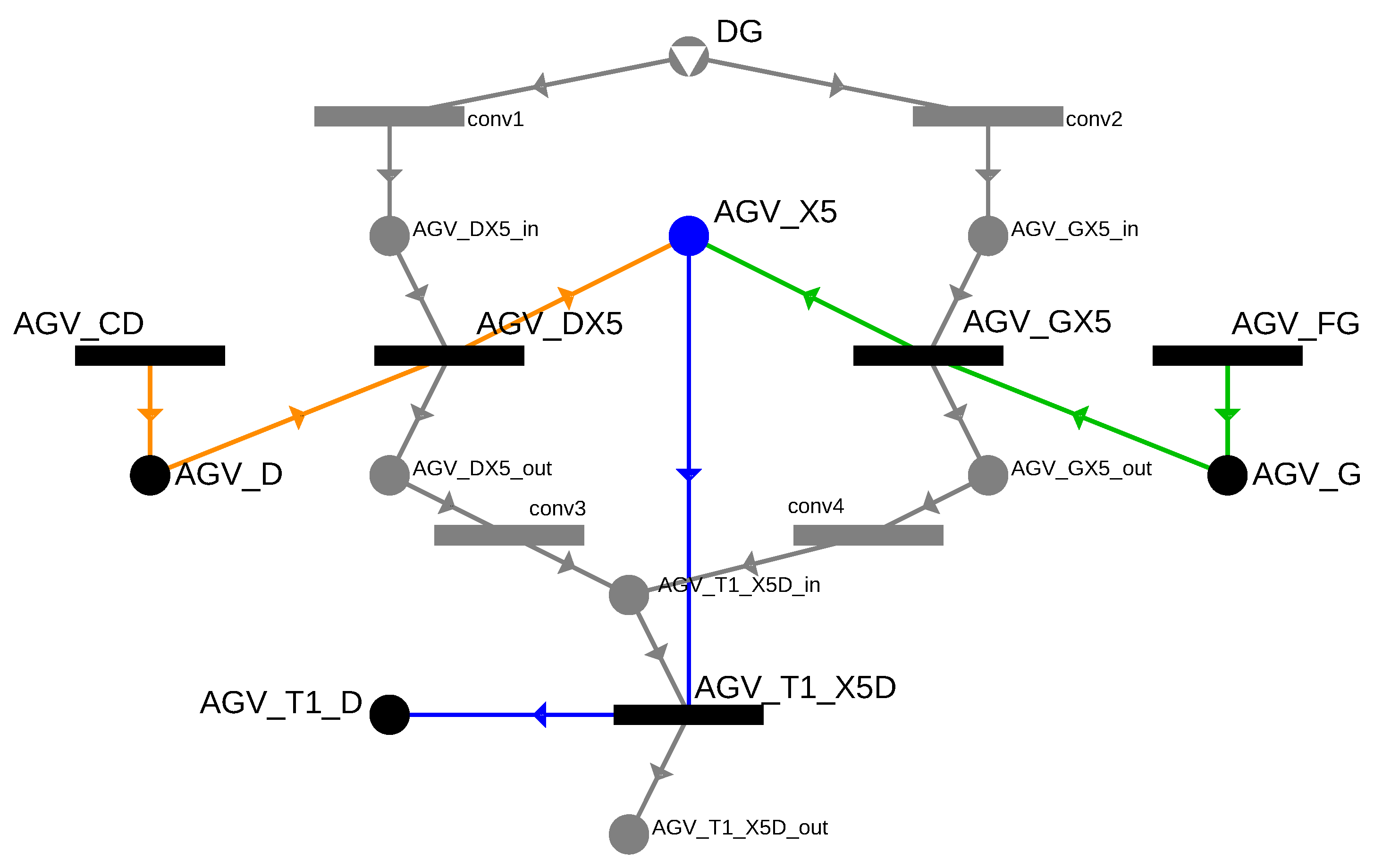

As the next example, let us consider a subgraph that demonstrates the handling of the cell DG associated with bin X5. Here, in addition to the two previously introduced possible routes, marked in yellow and green, the return route marked in blue is also present. In this case, the following combinations must be modeled: depending on the chosen route, the DG cell must be assigned to either the AGV_DX5 or the AGV_GX5 movement. Additionally, it must be ensured that the cell is available for AGV_T1_X5D, which describes the actual transport within the DG cell. In Figure 13, the nodes and edges implementing the handling of the DG cell are marked in gray. The DG cell as a resource can be independently converted into either the AGV_DX5_in or AGV_GX5_in state. One of the two movements will be executed, resulting in either AGV_DX5_out or AGV_GX5_out. However, since it is not possible to know exactly which one, the conversion to the AGV_T1_X5D_in state must be ensured for both. This way, all combinations are included in the initial graph, ensuring that, regardless of the chosen route, the cell is available for each movement.

Figure 13.

Handling multiple passages in the case of several possible combinations of assignment operations.

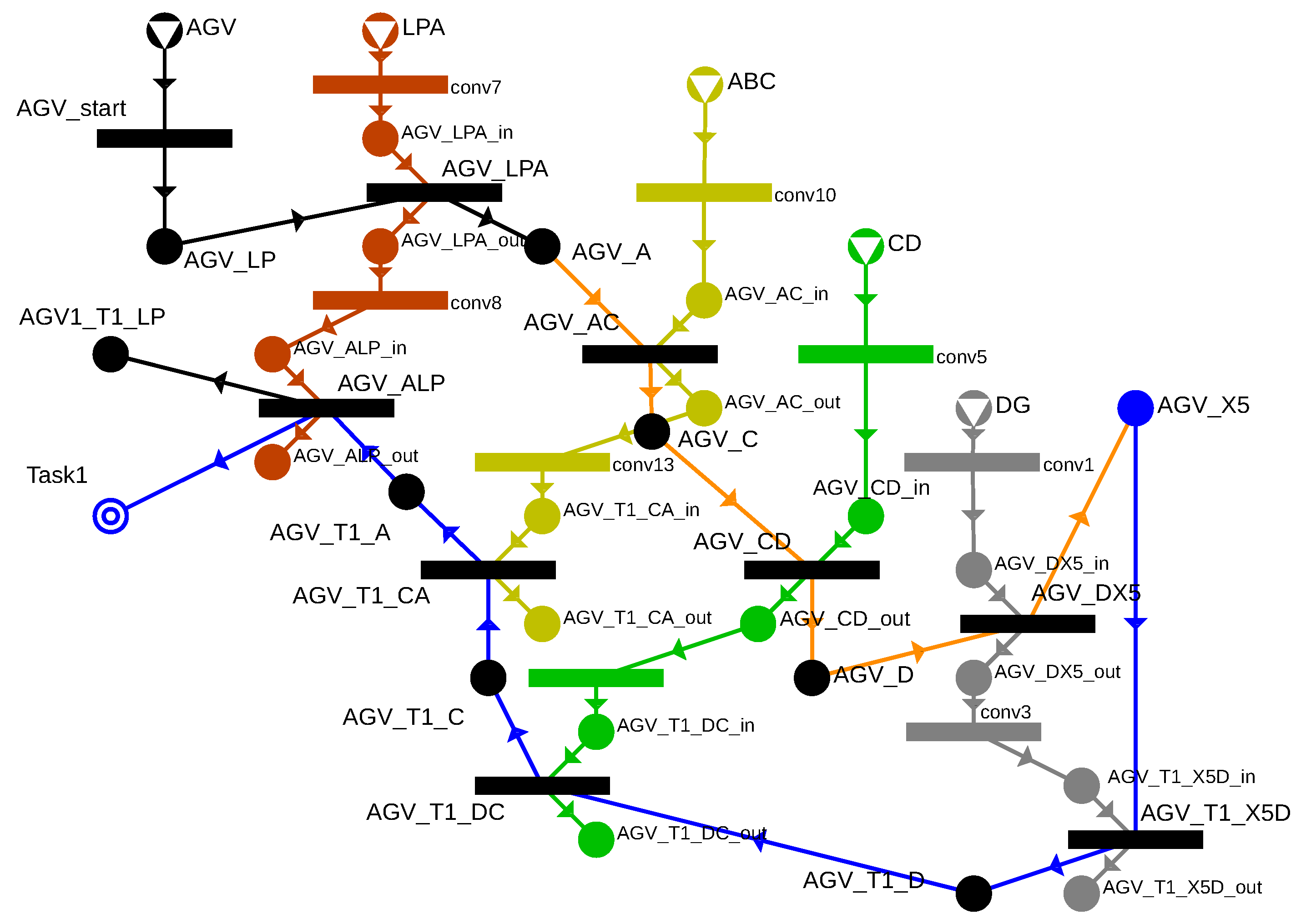

Figure 14 presents the complete P-graph, which can handle both alternative routes as well as transportation from bin X5 back to the loading point while ensuring the exclusive use of cells.

Figure 14.

The model with the handling of multiple possible routes and multiple passages.

3.4.4. Modeling Multiple AGVs

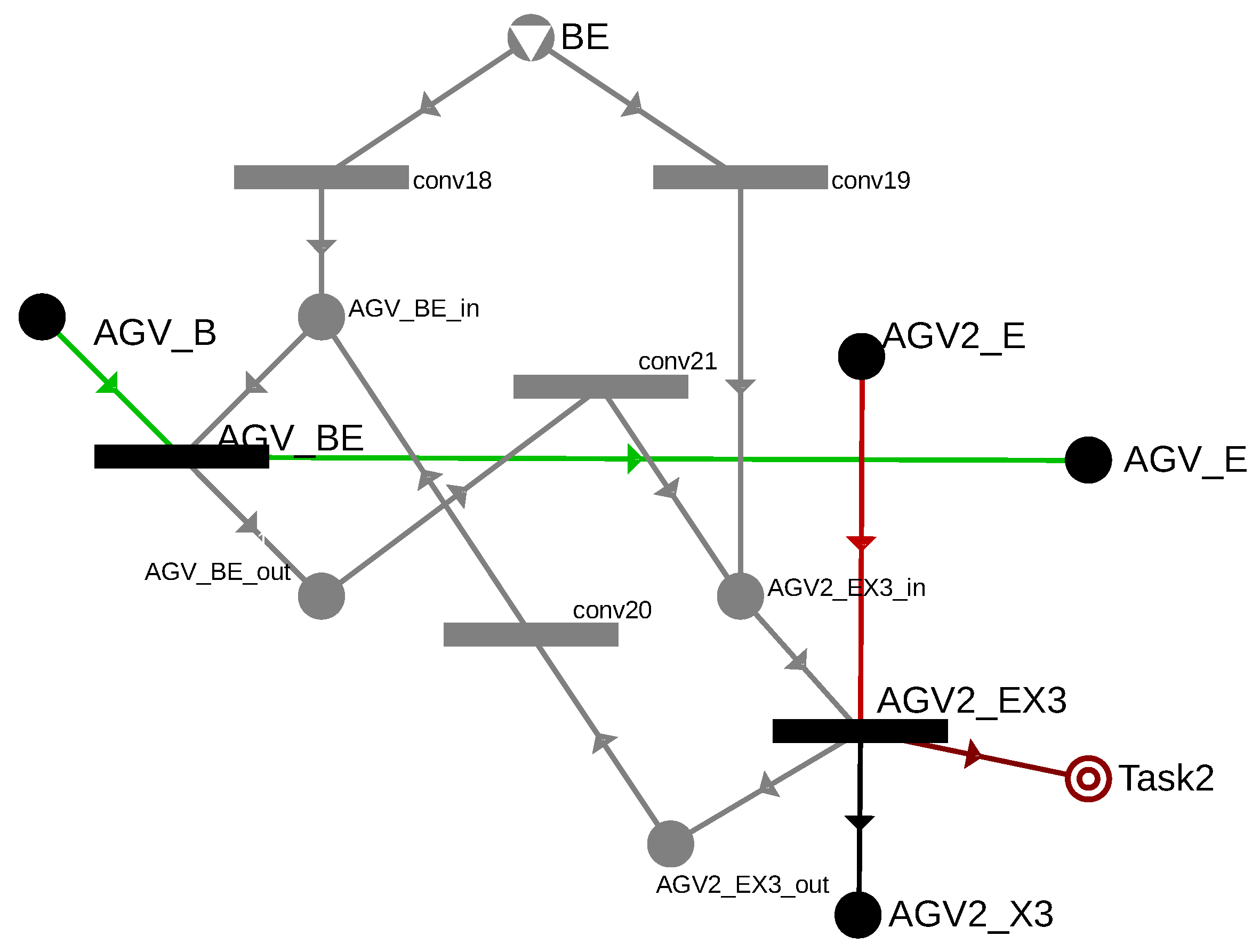

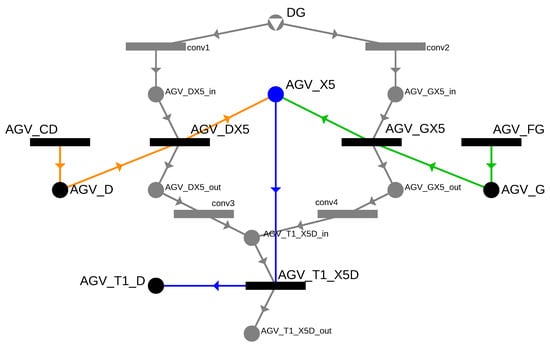

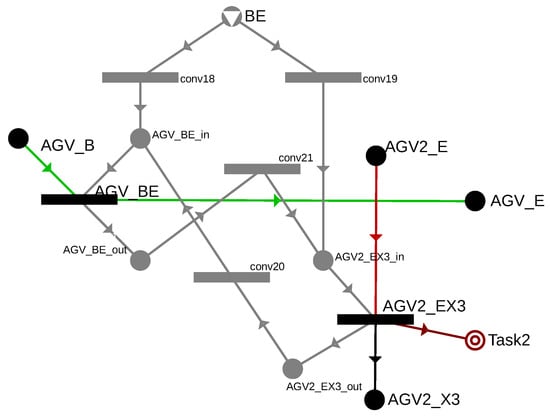

The AGV fleet can only be scheduled efficiently if the routes of individual AGVs are synchronized with each other. For this, it is necessary to handle all possible routes of all AGVs within a single model, where the synchronization will be ensured by the exclusive use of cells. The cell management described in the previous subsection can also be applied to the routes of multiple AGVs, but more combinations may need to be handled. Let us extend the previous example by adding another AGV, called AGV2, which is located in cell EF and has to place its shipment in bin X3. Both cell EF and cell BE are in AGV’s routes, but the order of passage has not been predefined, so the structure must involve both possibilities.

Figure 15 highlights the handling of cell BE, which must be accessible for AGV during the B → E movement (AGV_BE), and for AGV2 during the E → X3 movement. For both movements, the previously introduced {movement}_in as input and {movement}_out as output were specified. In the case of cell BE as a resource, the conversion to the AGV_BE_in and AGV2_EX3_in states must be ensured, which enables passage through the cell. Depending on whether AGV or AGV2 passes first, AGV_BE_out or AGV_EX3_out will be the result. However, to ensure the second passage, additional conversion operations are needed to make the cell available for the second movement as well. Therefore, transitions between AGV_BE_out and AGV2_EX3_in, as well as AGV2_EX2_out and AGV_BE_in, need to be added. Thus, the structure guarantees passage in both possible orders, and the solver algorithm determines the optimal order based on the time parameters and the objective function.

Figure 15.

Handling potential assigments of cell EF to two AGVs: AGV denoted by green and AGV2 denoted by red.

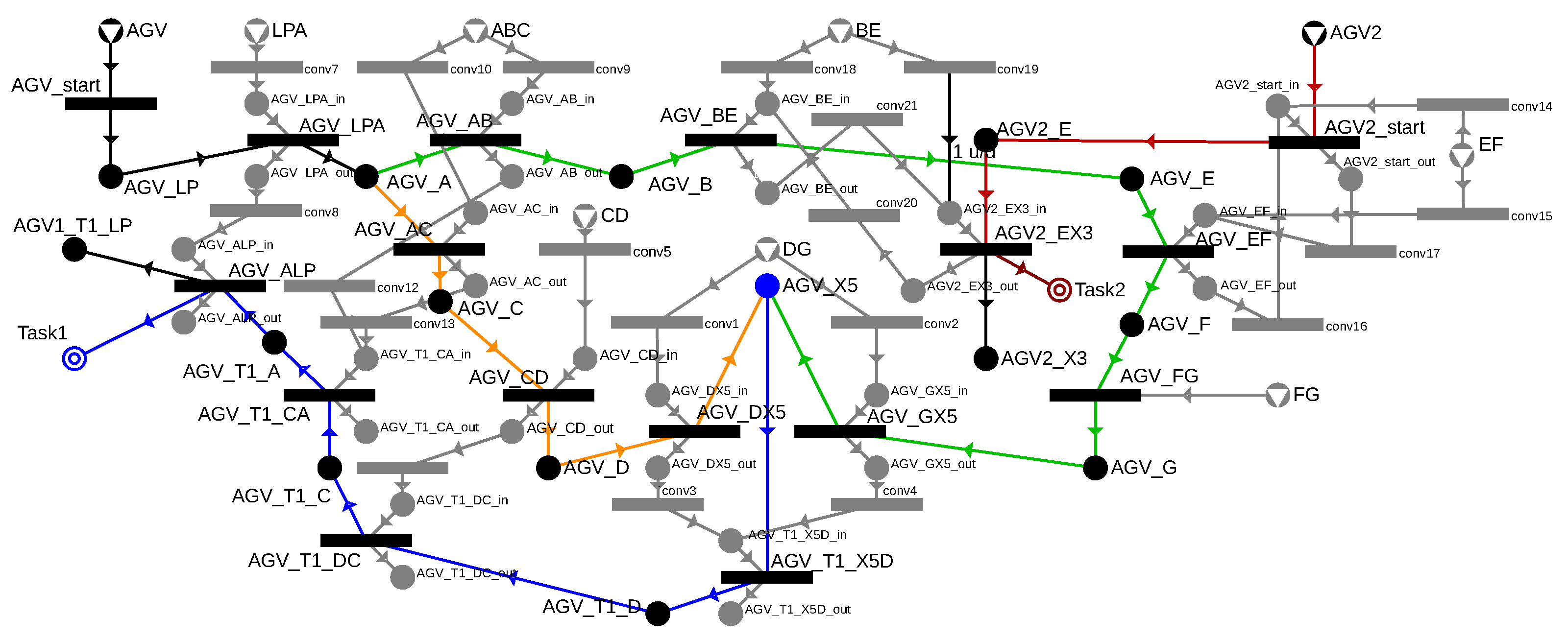

In Figure 16, the full example is extended with the E → X3 route for AGV2, highlighted in red, and the nodes required for cell management are shown in grey.

Figure 16.

The complete P-graph model with the handling of multiple possible routes and two AGVs.

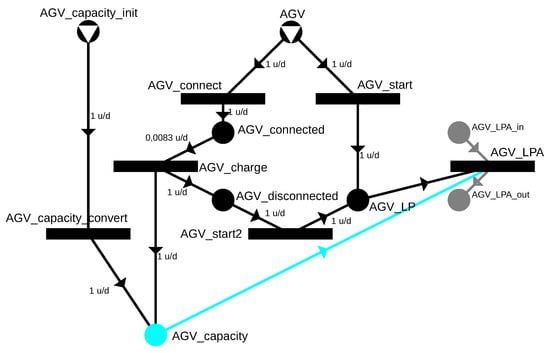

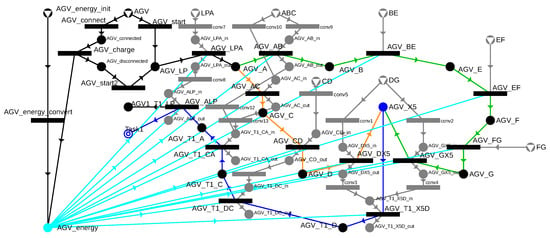

3.5. Charging and Range Modeling for Electric AGVs

The AGVs used in warehouses are typically electric, so scheduling will only be feasible in practice if the energy required for the planned movements can be covered by the AGV’s battery. This can only be ensured if the AGV battery charge level is managed and the expected consumption is estimated during the design phase at the modeling level. It is assumed that at the beginning of the scheduling, the current battery charge level of the AGVs is known and represented as a resource in the P-graph model. For every planned movement, the AGV consumes energy, which is determined based on the distance traveled between the two gates. It is useful to differentiate between empty and loaded states to achieve a more accurate model. The energy consumption can be defined by the weight of the input, describing the energy consumption of the movements. This approach restricts the route that the AGV can traverse, so during scheduling, only as many transportation demands are assigned as can be completed based on the battery charge.

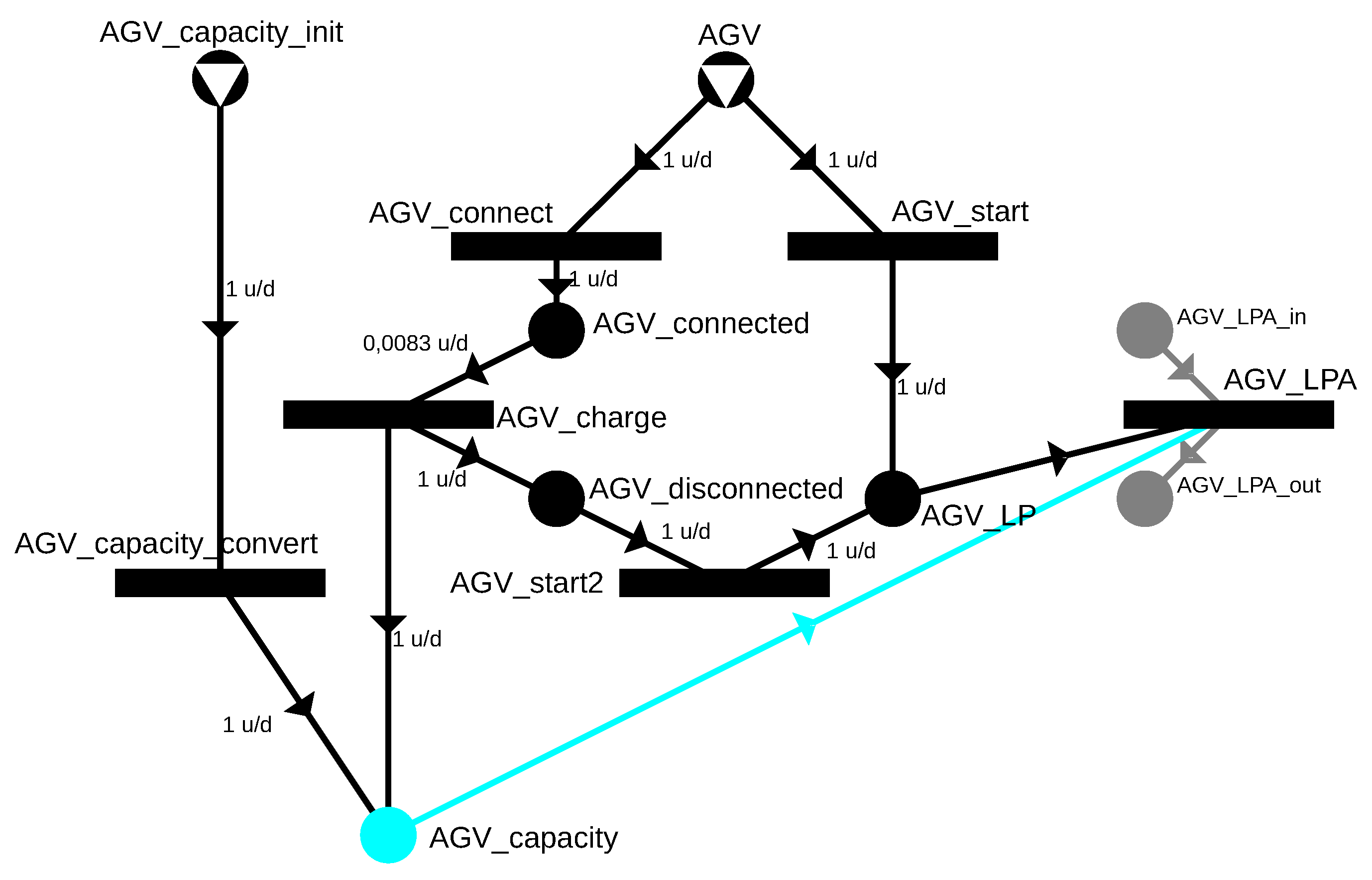

During route generation, it must be ensured that the AGV can return to the charging station, so a corresponding route must be generated according to the modeling steps presented earlier. A further option is that the AGV may not start immediately at the beginning of scheduling but instead wait at a charging station, thereby increasing its battery charge and thus the distance it can cover; the P-graph model describing the charge is shown in Figure 17. The precondition for movements is AGVenergy, which is composed of two parts: (1) the initial level of energy (AGV_energy_init) and (2) the extra energy gained from charging. The previously used AGV, as a resource, can either start executing a transportation demand without charging via the AGV start transition or virtually connect to the charger by the AGV_connect operation. The AGV_charge operation increases the battery energy level on a per-minute basis, with its input being a small portion of AGV_connected; in the example, it is 1/120, which limits the charging to 2 h. The AGV_charge operation is assigned 1 min of proportional time, which regulates the time to achieve the AGV_disconnected state, after which transportation demand can commence following the charging. The other result shows the energy gained from 1 min of charging, so the volume of AGV_charge will determine how much the initial energy level has been increased.

Figure 17.

P-graph depicting battery charging by operation AGV_charge and energy consumption by cyan arc for electric AGVs.

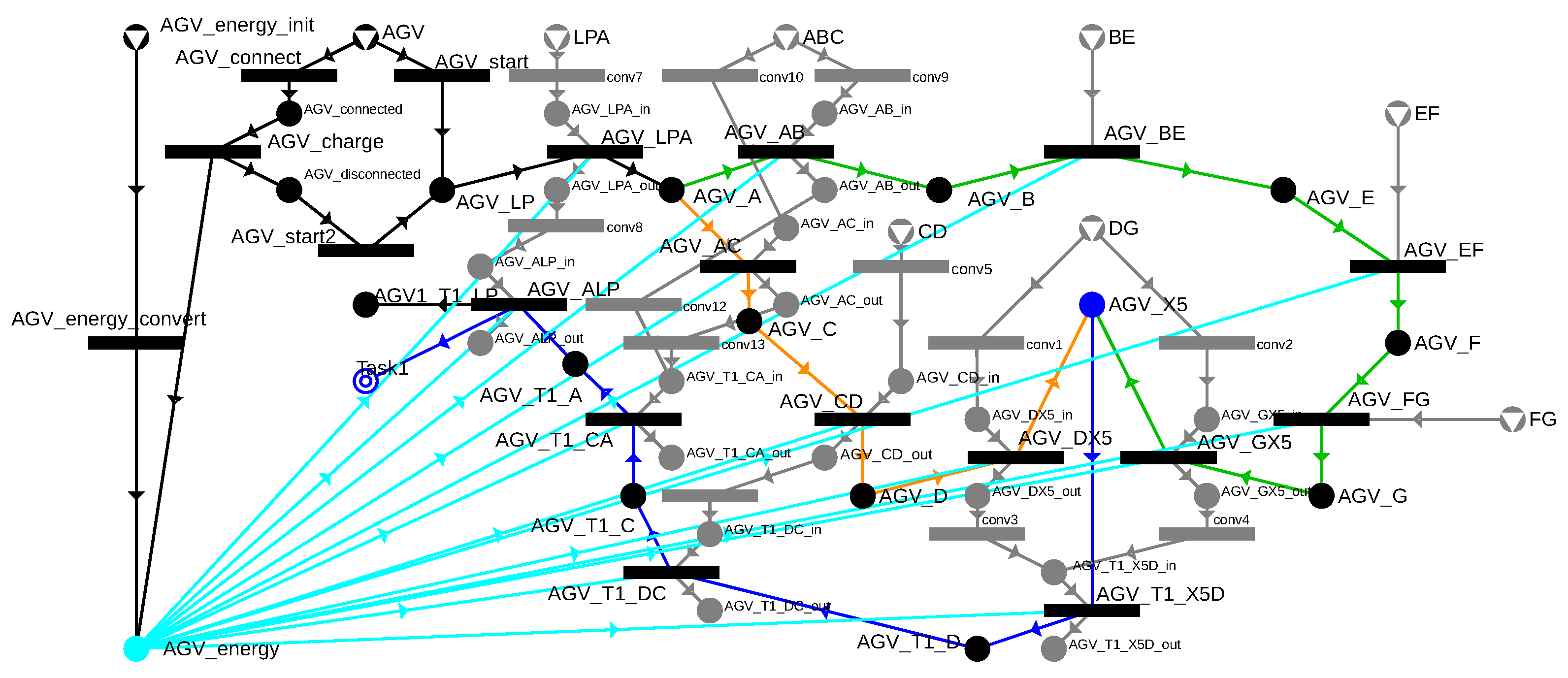

The P-graph shown in Figure 18 already includes the AGV charging option, and for every previously introduced movement, the arc modeling of the energy consumption has also been integrated.

Figure 18.

P-graph depicting energy consumptions by cyan arcs of operations potentially performed by an electric AGV.

The modeling steps presented in this section mainly demonstrate the AGV movements, collision avoidance, and proper modeling of battery management. Naturally, the scheduling problem is expanded to include the appropriate handling of transportation times and deadlines, as well as a more accurate determination of energy consumption and charging, which will be illustrated through an example in Section 4. Based on the warehouse layout, AGV parameters, and transport requirements, a software module capable of automatically generating and solving the P-graph model can be developed with the described modeling steps, thereby automating the planning process.

4. Case Study

In this case study, two representative internal transportation tasks are analyzed within a given warehouse layout using realistic operational parameters of an electric AGV.

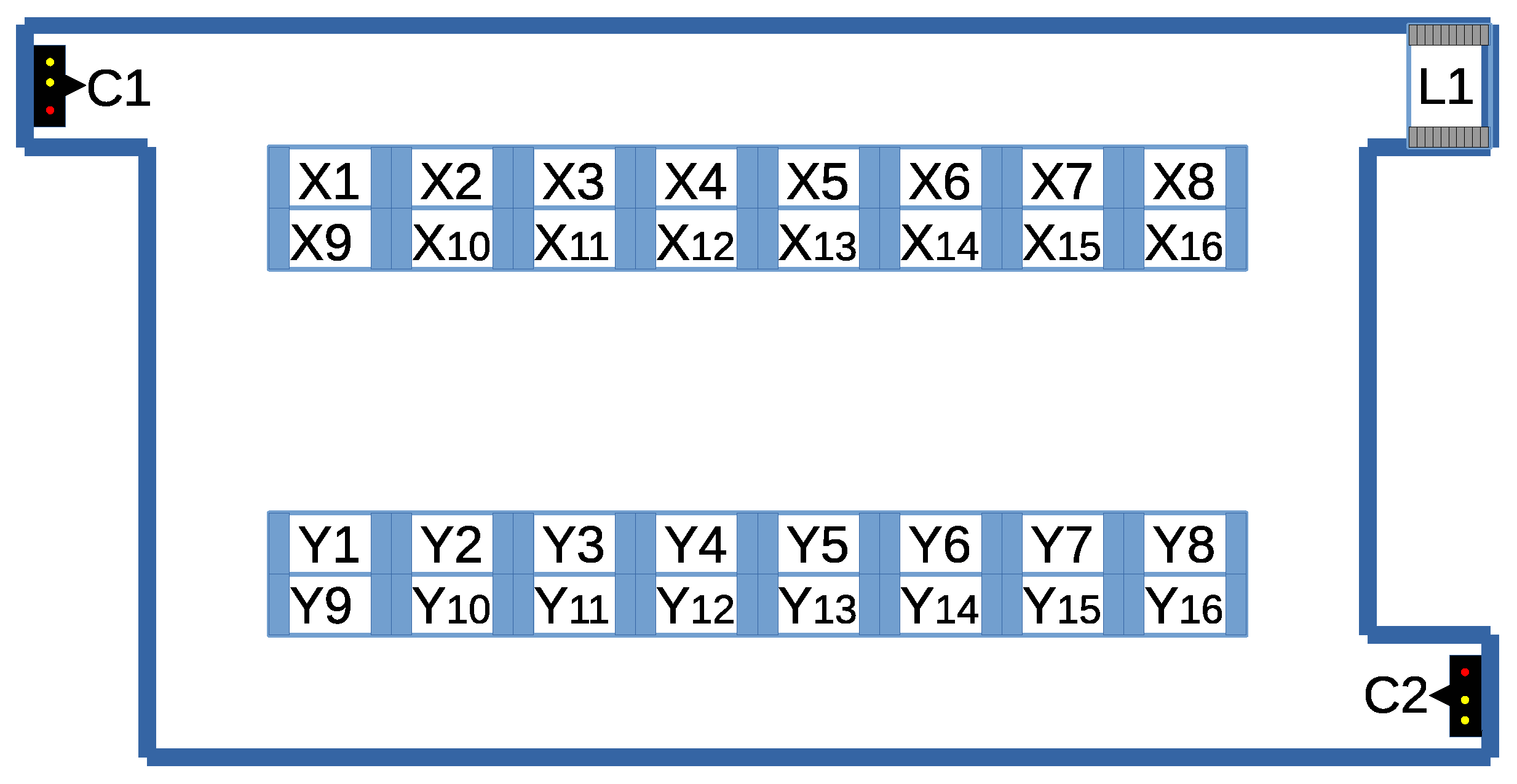

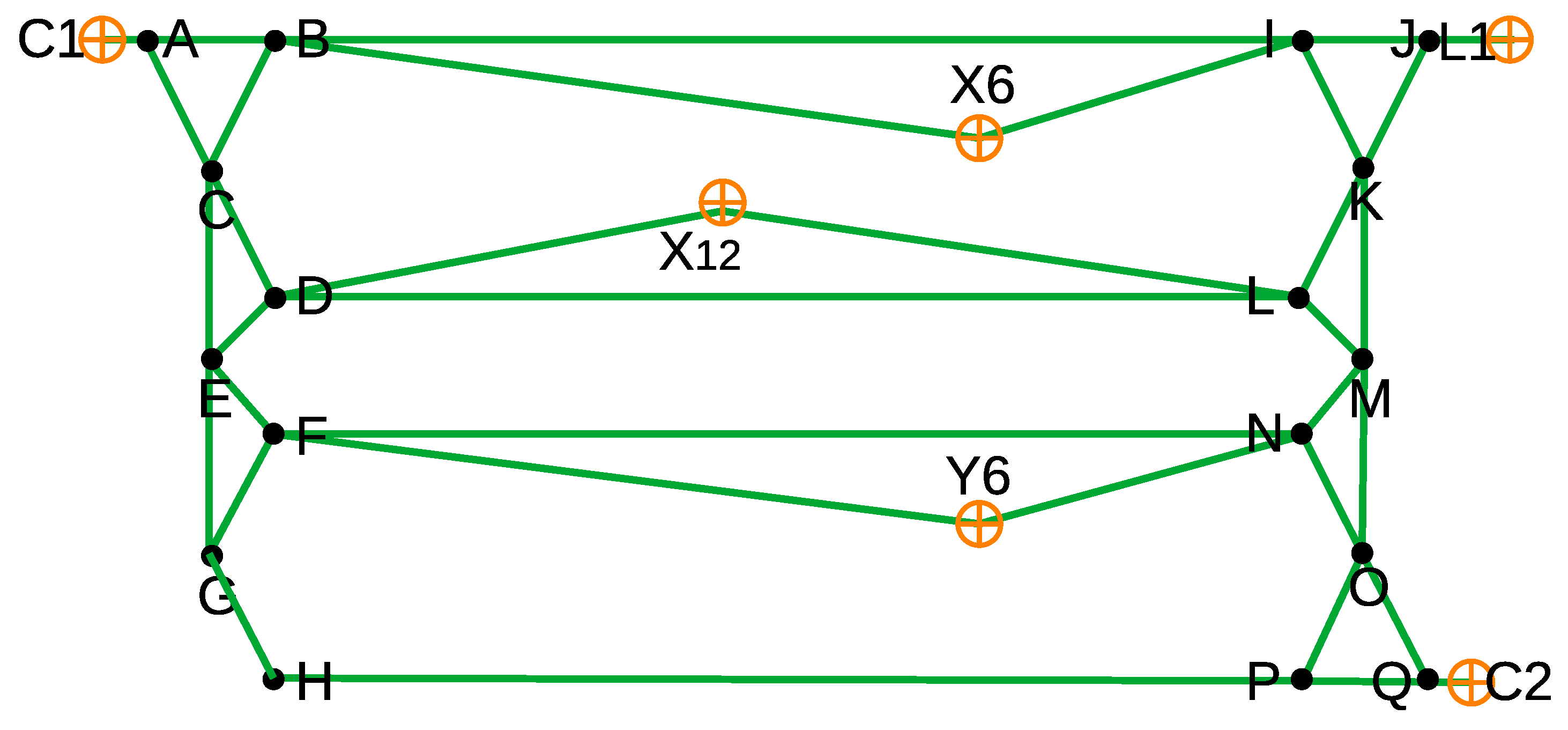

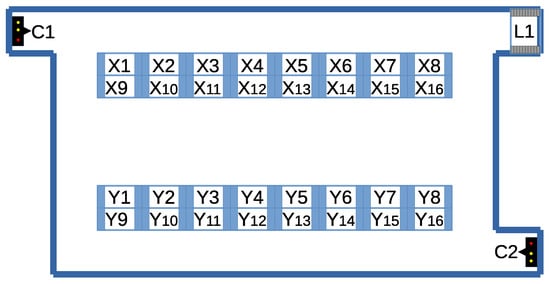

Consider the warehouse layout shown in Figure 19, with storage bins X1–Y16.

Figure 19.

Warehouse layout for the case study involving charging stations C1 and C2, conveyor L1, and storage locations X1, X2, …, Y16.

There are two types of missions to complete. One is to deliver goods from storage to conveyor L1, e.g., from position Y6. The other type of mission is to retrieve a pallet from positions X9–X16 or Y1–Y16 to positions X1–X8 because picking can only be performed at the locations represented in the top row of the figure, e.g., retrieving a pallet from storage X12 to position X6. The AGV missions considered in the present case study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Case study: AGV mission definitions for the considered warehouse layout.

A typical indoor electric AGV is designed to operate safely in human–robot shared environments; therefore, its dynamic performance is deliberately limited. The maximum driving speed is typically in the range of 1.2–1.8 m/s, while the longitudinal acceleration is constrained to approximately 0.2–0.6 m/s2, depending on the payload and safety configuration. These limits ensure smooth motion, short stopping distances, and predictable behavior during autonomous material handling operations. The representative motion parameters used in this study are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative dynamic parameters of an indoor electric AGV.

The electrical system of an AGV is optimized for energy-efficient continuous operation and opportunity charging. Such vehicles are commonly equipped with lithium-ion battery systems operating at nominal voltages between 24 and . Depending on the mission profile, the average electrical power consumption during normal operation ranges from to , including traction, lifting, and onboard control systems. These values allow for several hours of autonomous operation while maintaining predictable energy usage. The representative electrical parameters adopted in this study are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Representative electrical and energy-related parameters of an indoor electric AGV forklift.

For high-power opportunity charging, a onboard or external charger can be applied. Considering a total battery capacity of 14.4 kWh and an overall charging efficiency of approximately 90%, the theoretical full charging time is estimated to be around 45 min.

4.1. Modeling the Floor Map for the Case Study

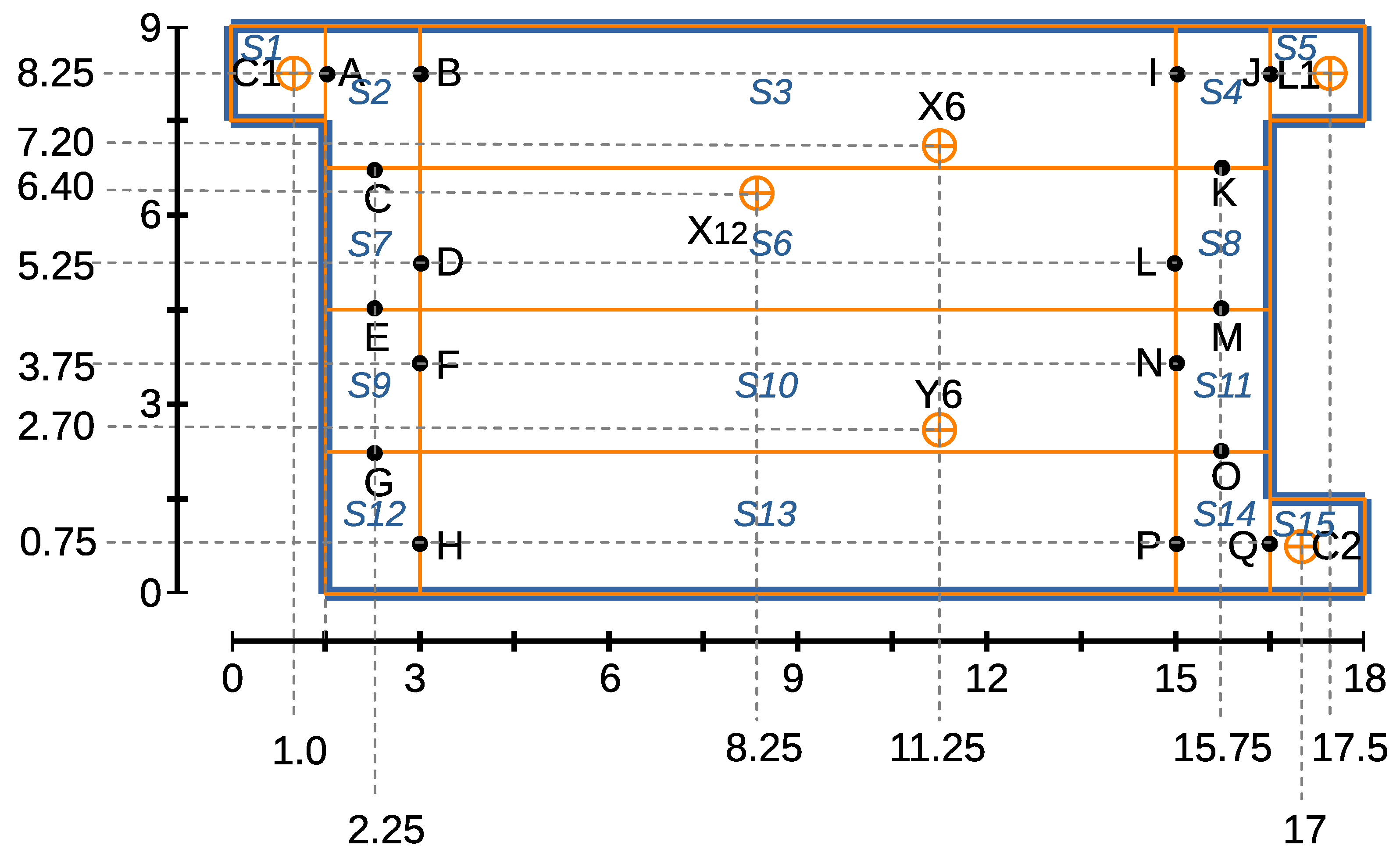

In Figure 20, the floor map has separated into cells S1, S2, …S16 cells. Cells S1 and S2 contain the charging stations C1 and C2, respectively. Cell S5 contains conveyor belt L1. Shelves X1–X8 and Y9–Y16 can only be packed by at most one AGV at a time, so cells S3 and S13 are assigned, which can only have one vehicle at a time. The distance between shelf rows X9–X16 and Y1–Y8 is large enough to allow the two shelf rows to be packed separately from cells S6 and S10.

Figure 20.

Cells S1, S2 …S15 and gates A, B, …Q specified for modeling the floor map involving charging stations C1 and C2, conveyor L1, and storage locations X6, X12, and Y6.

A cell can contain at most one vehicle at a time, but due to the segmentation, before a vehicle exits cells S1, S3, S5, S6, S10, S13, and S15, it can wait for another vehicle to pass cell S2, S4, S7, S8, S9, S11, S12, or S14. They can move from one cell to another by passing through gates A, B, …, and Q.

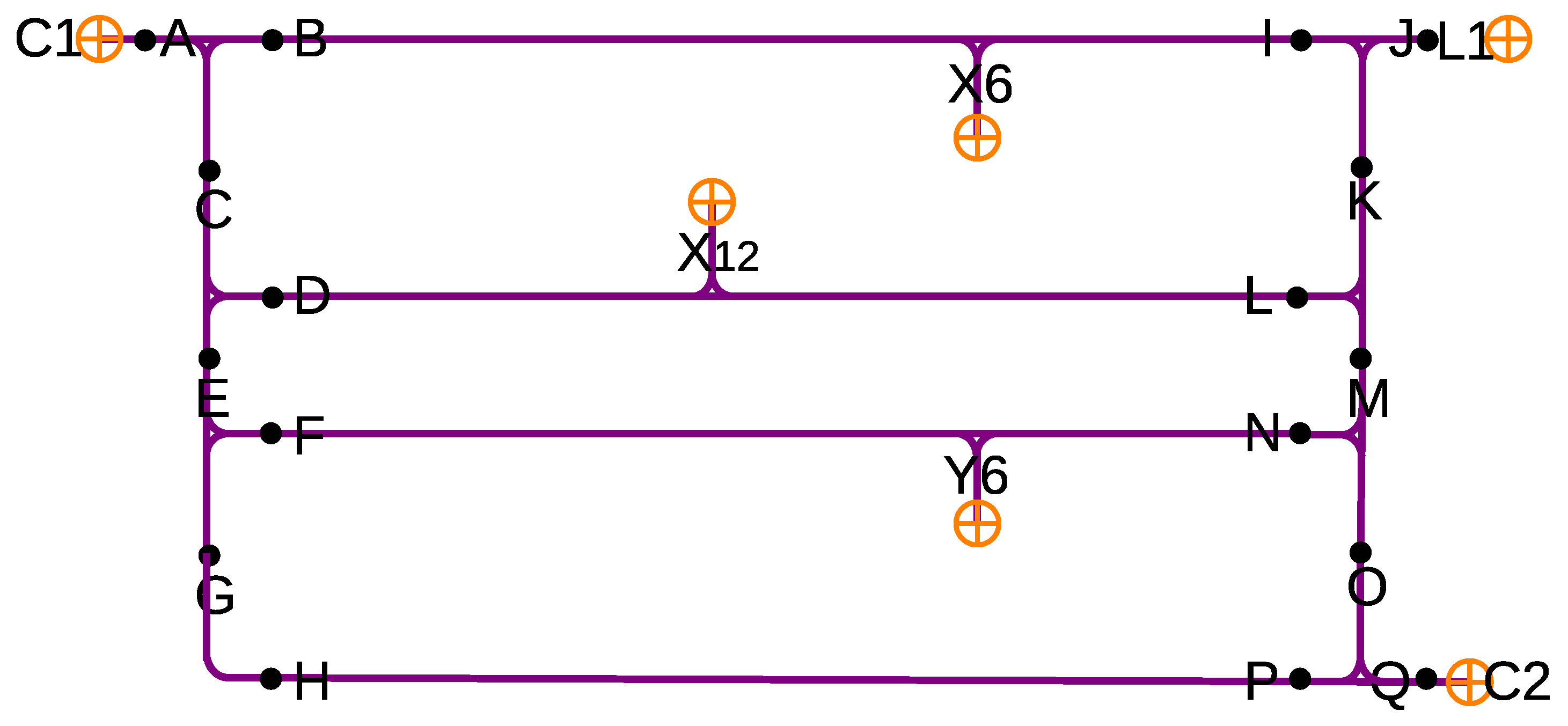

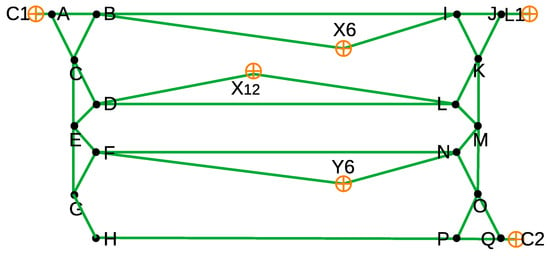

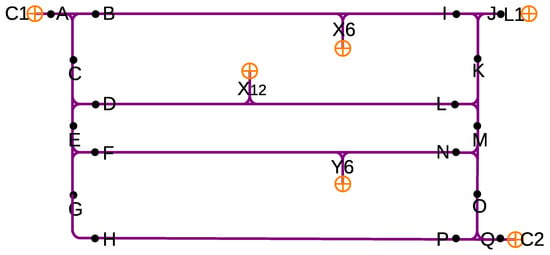

4.2. Generation of the Routing Graph for the Case Study

Vehicles move between points A, B, …, Q at the cell boundaries as they traverse the cells. Therefore, the route is represented by a graph where edges connect all entry and exit points within each cell, as shown in Figure 21. For example, the entry points C, D, and E of cell S7 are connected by three edges forming a triangle.

Figure 21.

Routing graph involving gates A, B, …Q charging stations C1 and C2, conveyor L1, and storage locations of interest X6, X12, and Y6.

Additionally, there is an edge leading to every point visited by a mission. For example, there is an edge from the entry point J of cell S5 to the L1 drop-off point or from the entry points B and I of cell S3 to the X6 storage area. Similarly, there is an edge from the vehicle’s starting point to the exit point of the current cell, such as from the C1 charging station in cell S1 to exit point A or from the C2 charging station in cell S15 to exit point Q. Figure 21 includes an edge for each possible movement within each cell.

4.2.1. Trajectory Planning and Travel Time Estimation for the Case Study

Applying the calculation method described in Section “Trajectory Planning and Travel Time Estimation”, and based on the vehicle parameters presented in Section 4, the travel times for each edge of the route graph are given in Table 5. In this example, the two vehicles have identical properties.

Table 5.

Estimation of travel, turning, and lifting times for vehicles moving according to the routing graph.

Between turns, the vehicles move parallel to the racks and shelves; thus, finally, they move along the lines depicted in Figure 22 between the points of the route graph.

Figure 22.

Trajectories for vehicles moving on the floor map between locations identified in the routing graph.

4.2.2. Energy Consumption Estimation

Based on the energy consumption parameters of the AGV and the edges of the route graph presented in the previous section, the energy consumption values are estimated and summarized in Table 6. The expected energy consumption is distinguished for unloaded () and loaded () states. These values are subsequently used to parameterize the P-graph model, where the energy requirement of transport between two nodes is defined accordingly.

Table 6.

Estimation of energy consumption for vehicles moving according to the routing graph.

The energy consumption associated with material handling operations is determined separately for a single lifting–lowering cycle (), with the energy demand of the handling operation set to 0.7 Wh. The calculation uses the time parameter defined in Table 5 and the value of 30 Wh/min determined in Table 4. This energy amount is added to each tour that involves material handling at its beginning or end.

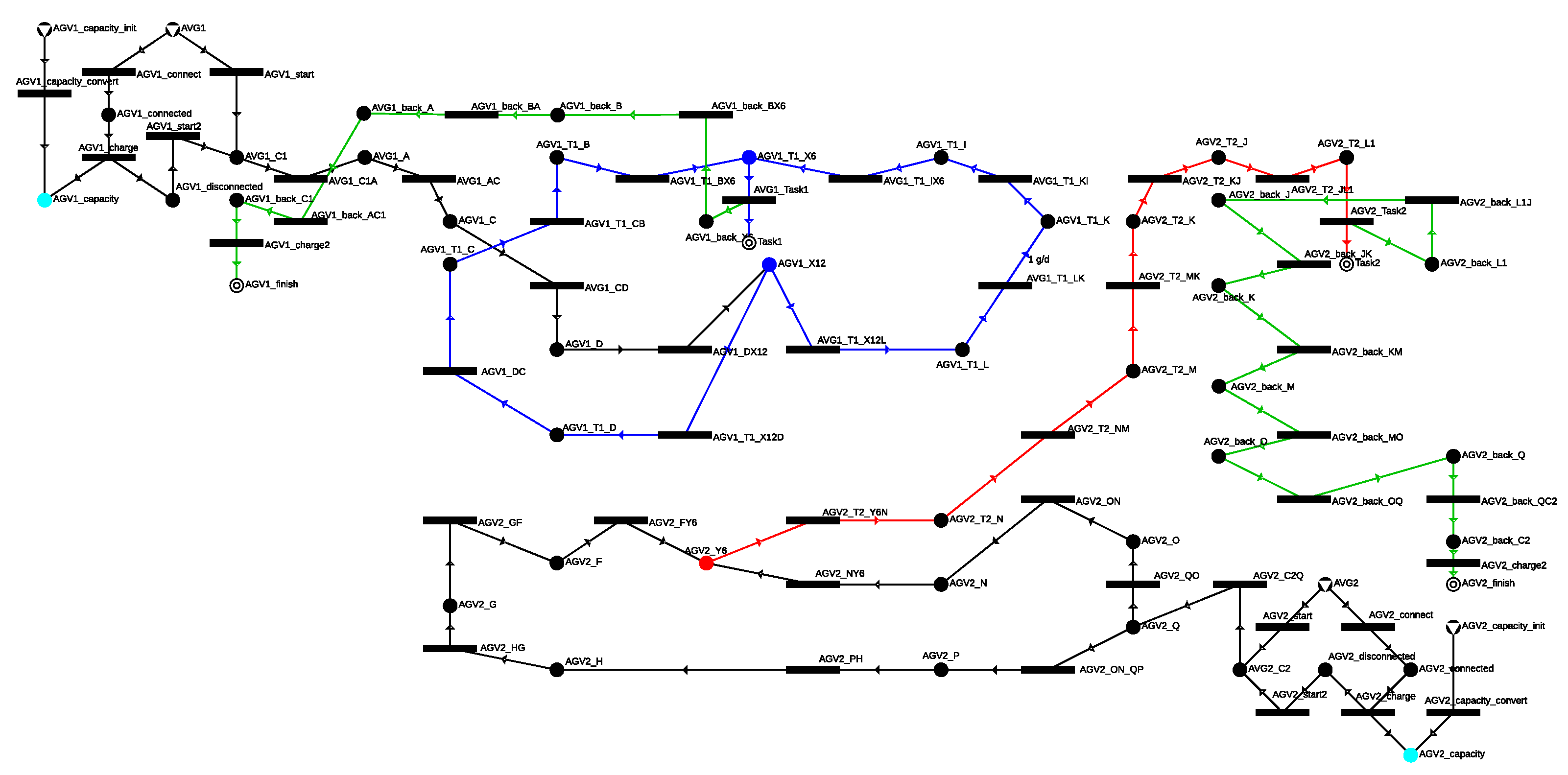

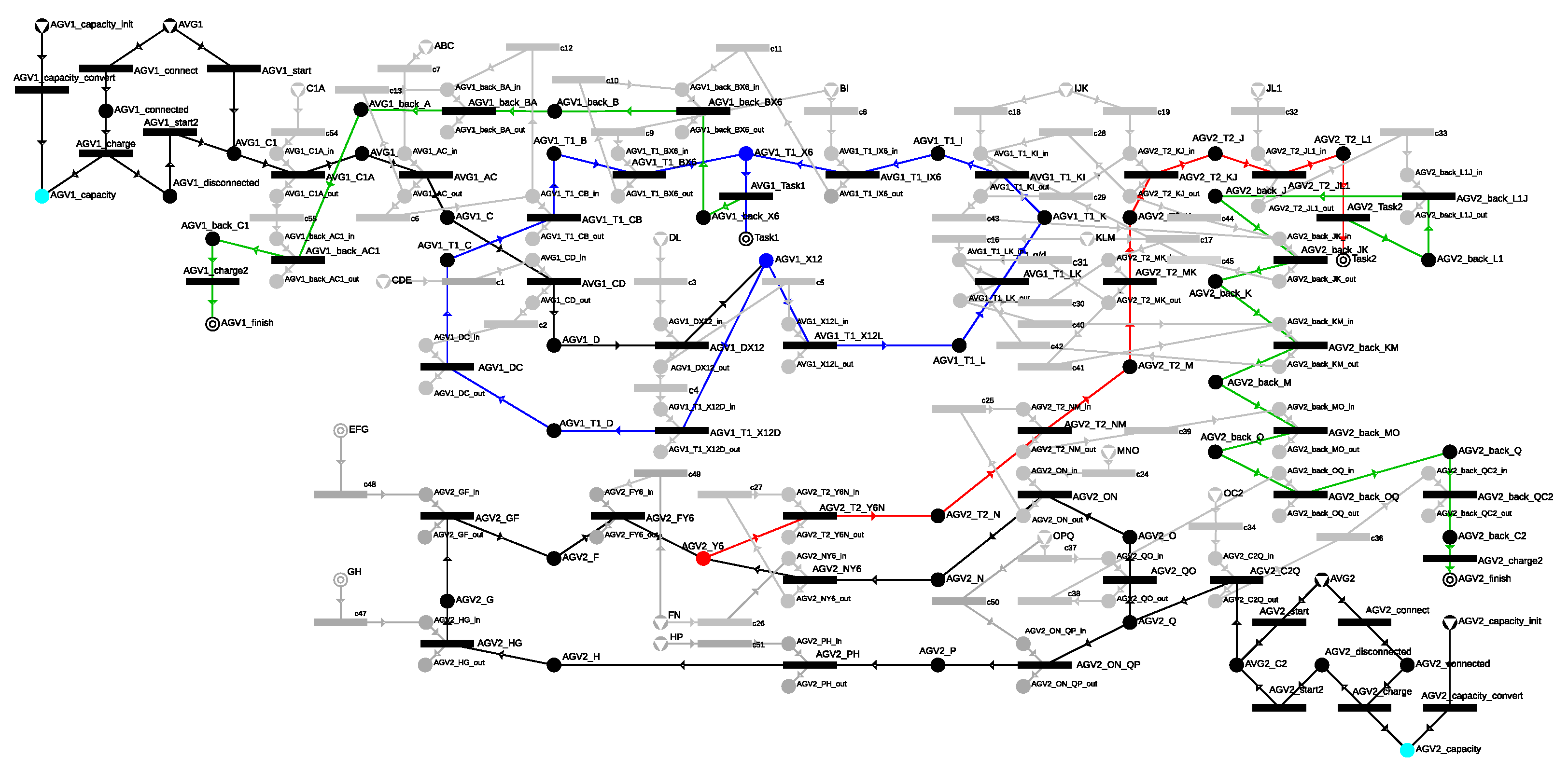

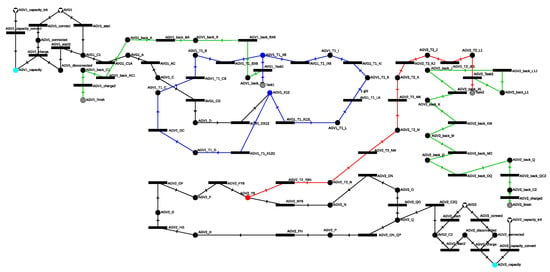

4.3. Generated P-Graph Model

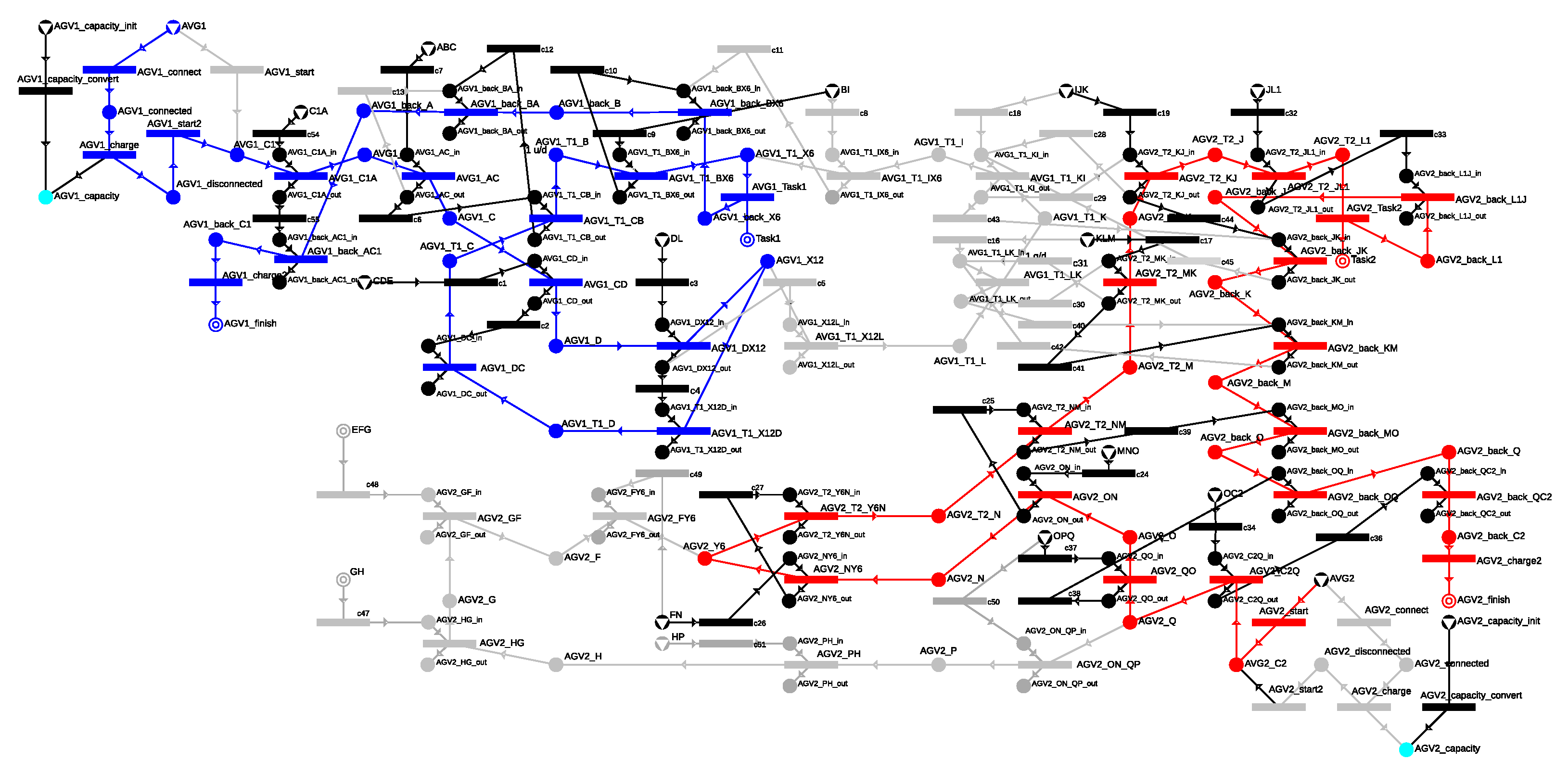

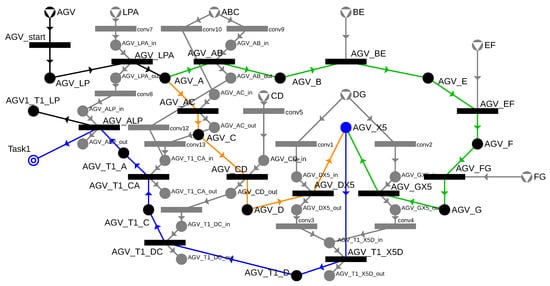

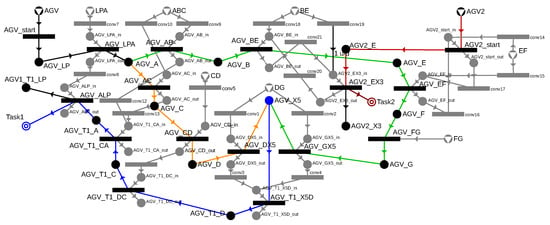

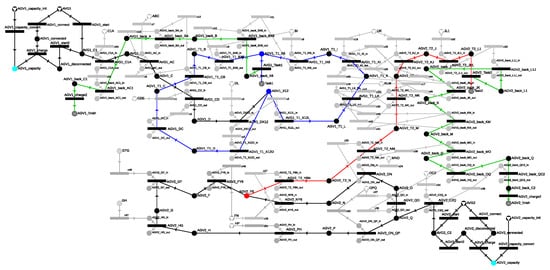

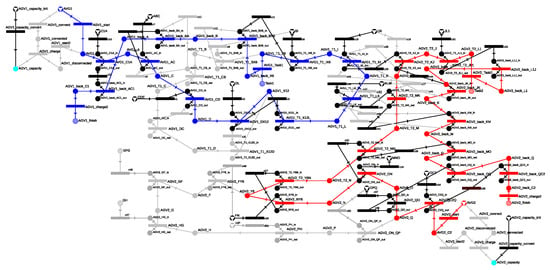

The construction of the P-graph model is based on the steps presented in Section 3.4, upon which a model-generating algorithm was developed. This algorithm is capable of generating and managing numerous alternative routes based on the set parameters. In the case study, the number of possible routes is limited in order to make the P-graph more readable: AGV1 starts from the C1 charger and reaches the starting point of task T1, which is bin X6, via the shortest route. It can then perform the transfer between bins X6 and X12 via the two shortest routes. After completing the task, AGV1 returns to the charger. In the case of AGV2, two alternative routes were considered, which allow it to reach the starting point of task T2, the Y6 bin, and it can execute the task via a single route. After completing the task, AGV2 returns to the C2 charger. The possible routes of the two AGVs intersect in the cells KLM and IJK. Figure 23 illustrates the modeling of the possible routes, where the routes for executing task T1 are marked in blue, the routes for executing task T2 are marked in red, and the routes marked in green represent the return to the charger.

Figure 23.

The P-graph model of the possible routes in a case study.

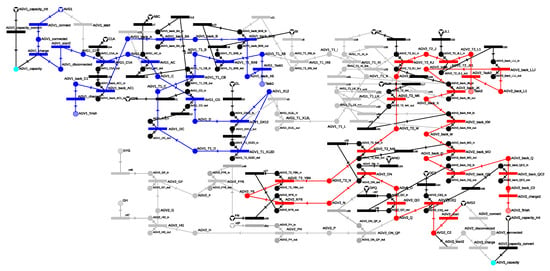

The next key step in generation is the management of the cells, which ensures that only one AGV can occupy a cell at any given time. Due to the alternative routes and AGVs passing through the same cell multiple times, appropriate management was required, which was done according to the steps outlined in Section 3.4.3. The P-graph model with cell management, related to the use case, is shown in Figure 24, which also represents the maximal structure. The movement times of the AGVs within the cells were determined based on Table 5.

Figure 24.

The maximal structure of the case study, which includes the possible routes with the appropriate cell management.

4.4. Solutions

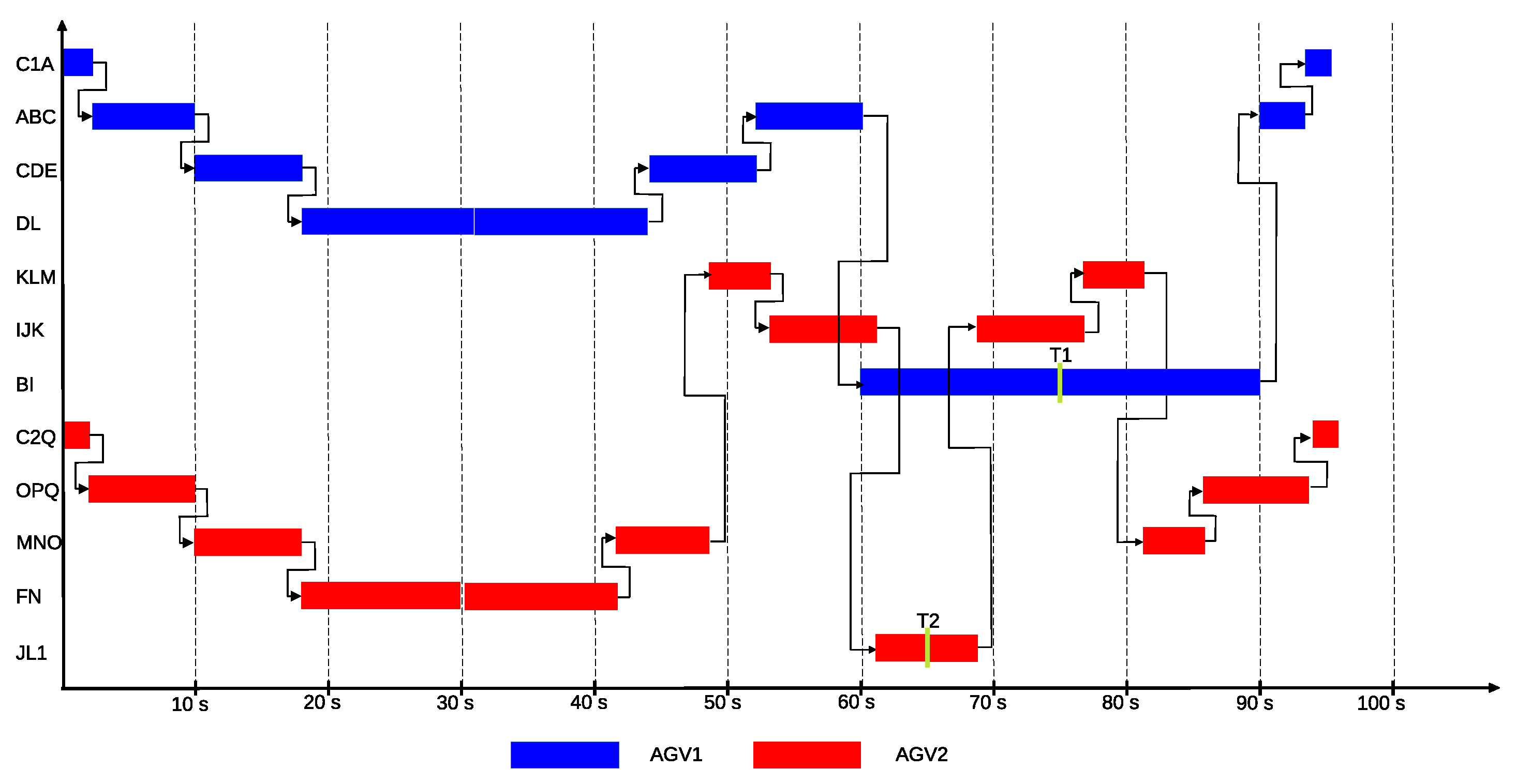

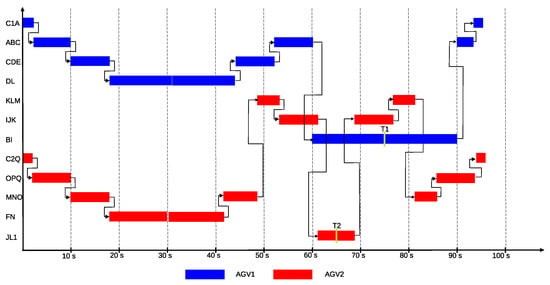

The maximal structure includes the previously defined alternative routes, as well as the passage through the corresponding cells with the estimated travel times. In the current example, the initial charge of both AGVs’ batteries is set to the maximum, enabling them to perform the assigned tasks. Accordingly, both AGV1 and AGV2 can start at the beginning of the scheduling period. Based on the optimal solution provided by the P-graph model, AGV1 travels from cell C1 along the route C1 → A → C → D → X12 to reach the starting point of task T1, where it picks up the load, which takes 31.35 s. It then performs the transport along the route X12 → D → C → B → X6, which requires 44.25 s. Meanwhile, AGV2 departs from the charger C2 along the route C2 → Q → O → N → Y6, which takes 29.90 s, and then begins executing task T2 along the route Y6 → N → M → K → J → L1.

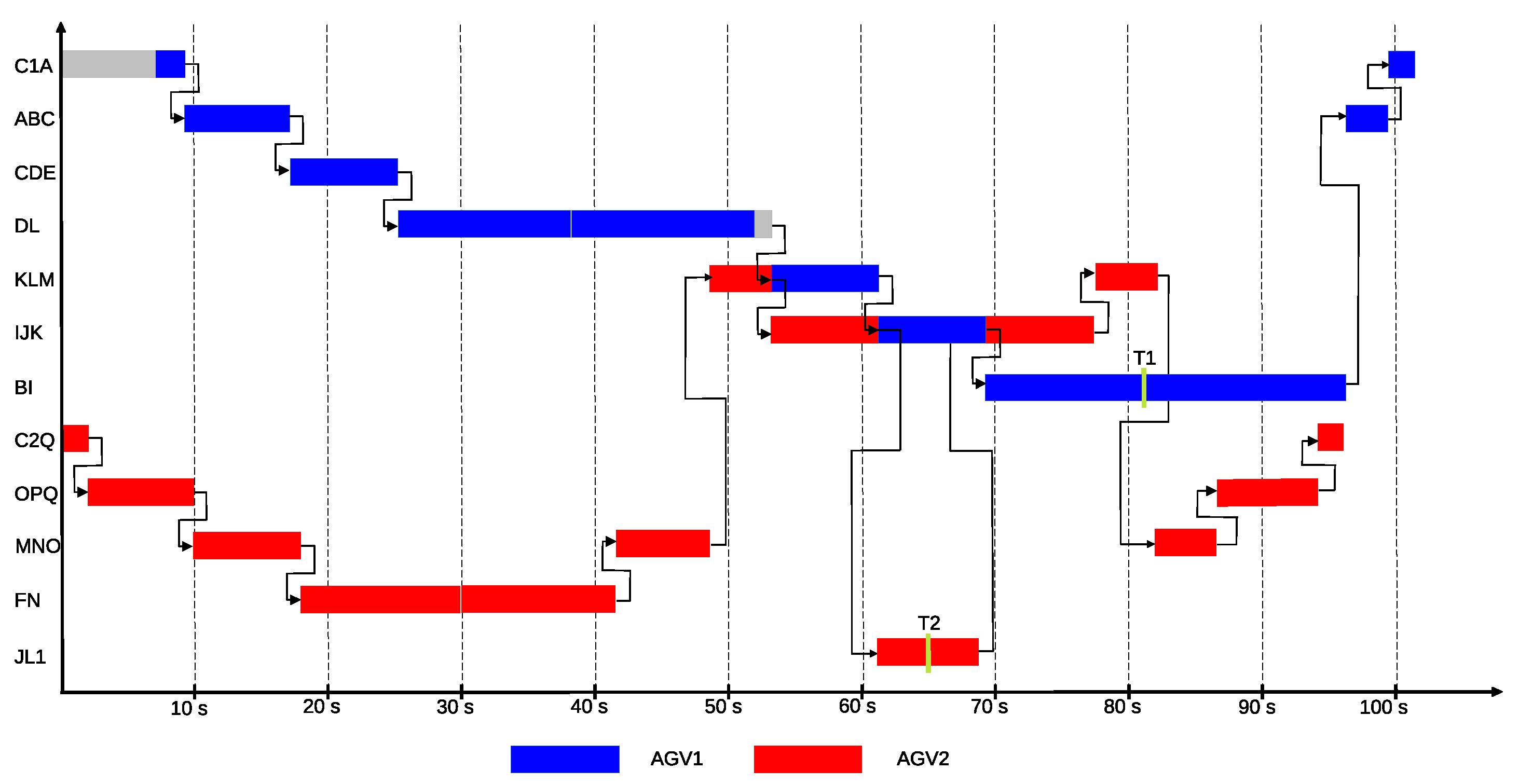

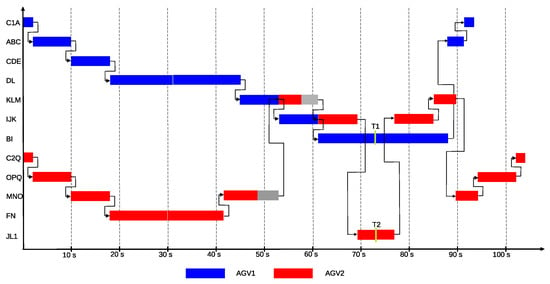

This solution is shown in Figure 25 in the P-graph structure, and in Figure 26 as a Gantt chart, where the path taken by AGV1 is represented in blue, and that of AGV2 in red. According to the objective function, the goal is the fastest execution, which in the optimal solution requires 75.60 s for task T1 and 65.26 s for task T2. The estimated energy consumption of the individual segments of the routes defined in the solution is determined based on Table 6. The calculation accounts for the energy consumption values corresponding to loaded and unloaded operating conditions. Based on these values, the energy demand of the routes traveled by AGV1 and AGV2 amounts to 28.64 Wh and 25.44 Wh, respectively. The objective function is evaluated using the formula introduced in Section 2.7, in which the values related to mission completion, energy consumption, and makespan are considered with equal weights. Accordingly, the value of the objective function is obtained as follows

Figure 25.

P-graph representing optimal routes for two AGVs: the operations of AGV1 are shown in blue, the AGV2’s in red.

Figure 26.

Gantt chart representating the optimal solution of the case study for two AGVs: the operations of AGV1 are shown in blue, the AGV2’s in red.

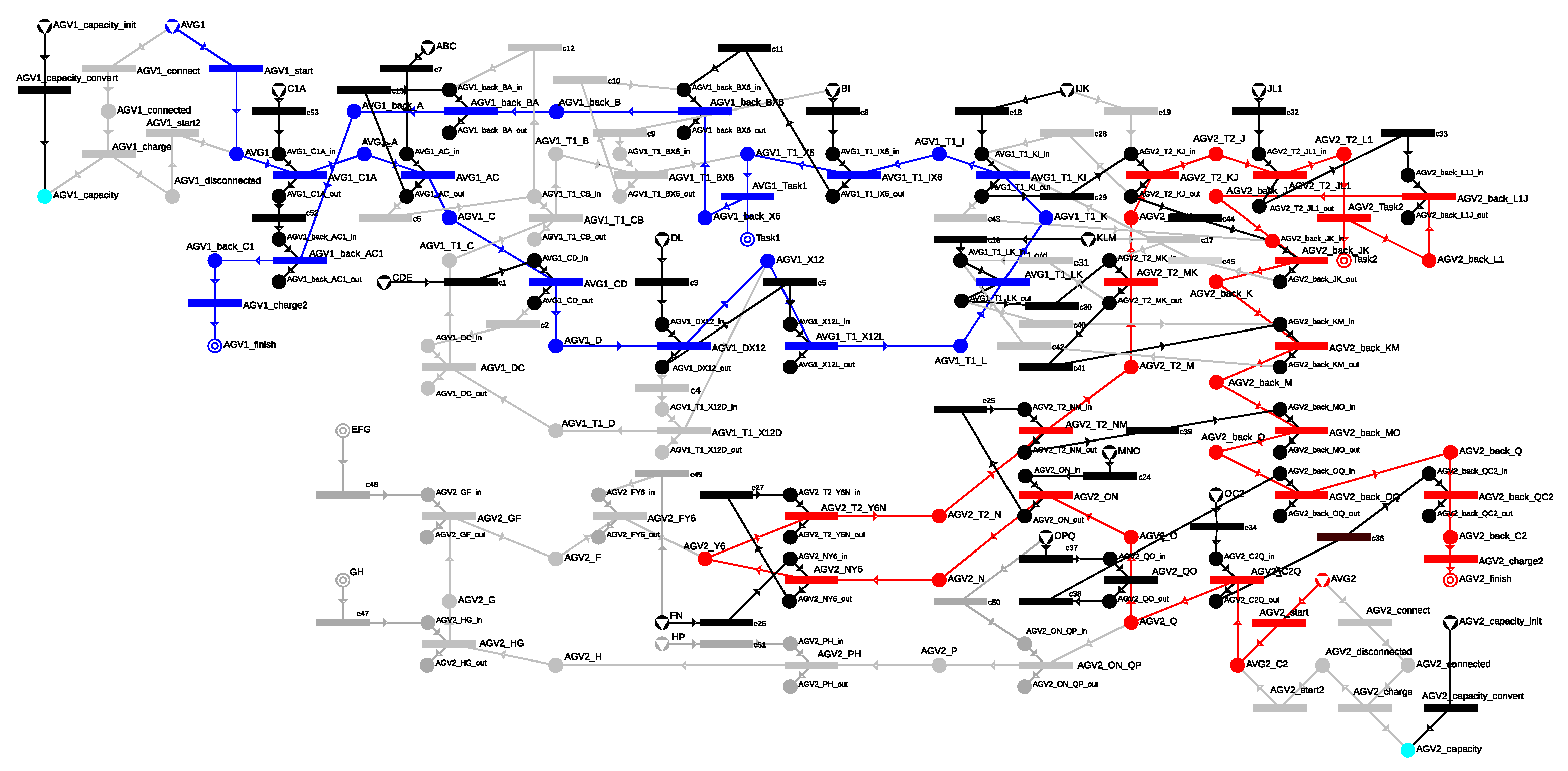

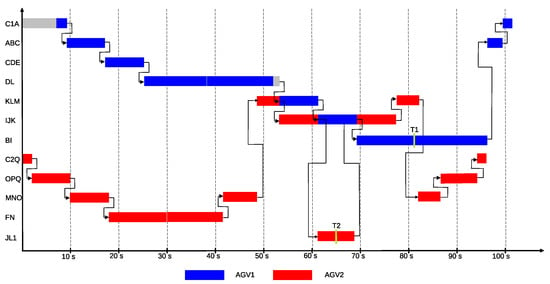

Based on the time requirements for passing through each cell, it can be determined that AGV1 take the longer route, as the faster option for completing task T1 would have been X12 → L → K → I → X6. Since the PNS framework is capable of generating not only the optimal but also the N-best solutions, this scenario can also be examined as the second-best solution. This solution is also represented in Figure 27 and Figure 28 within the P-graph structure and the Gantt chart. In the second-best solution, the shorter route X12 → L → K → I → X6 is selected for AGV1 to complete task T1. However, during its journey, AGV1 obstructs AGV2 twice, slowing down its execution of task T2, which results in a worse objective function value. The routes of the AGVs first conflict at the cell KLM, where AGV1 arrives first at 45.09 s, and it requires 8.01 s to make the turn, occupying the cell until 53.11 s. Meanwhile, AGV2 arrives at the M gate at 48.78 s and must wait 4.31 s until the cell is vacated to begin its passage, which takes 4.24 s. A similar situation arises at the next cell IJK, which AGV1 will vacate at 61.12 s after making the turn, causing AGV2 to wait an additional 61.12 − 53.11 − 4.24 = 3.77 s. Thus, AGV1 completes task T1 in 73.29 s, while AGV2 completes task T2 in 73.34 s.

Figure 27.

P-graph representing second best routes for two AGVs: the operations of AGV1 are shown in blue, the AGV2’s in red.

Figure 28.

Gantt chart representating the second best solution of the case study for two AGVs: the operations of AGV1 are shown in blue, the AGV2’s in red.

The energy consumption is calculated in a similar manner to that of the optimal solution. As a result, for AGV1, the shorter route leads to a reduced energy consumption of 27.6 Wh. However, due to the additional time requirement, the value of the objective function becomes less favorable and is given by

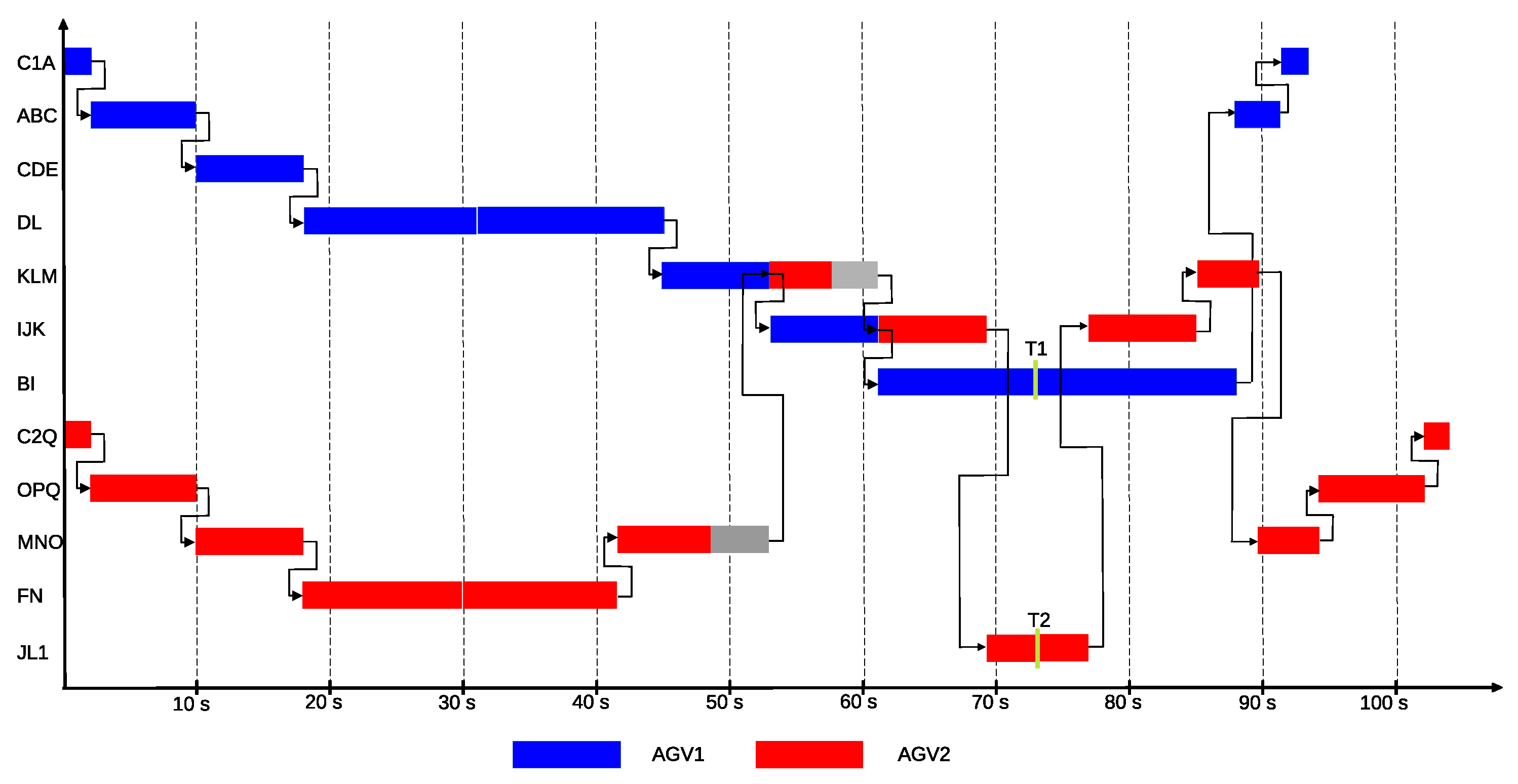

Consider the example in which AGV1 cannot start at the beginning of the scheduling period because it requires additional charging to complete the necessary route. The constructed P-graph model handles the initial battery capacity of the AGVs and ensures the charging operation as described in Section 3.5. To ensure that AGV1 can perform task T1 and then return to its starting position, an additional 9 s of charging is required in the current example. It is important to note that passing through the cells requires not only time but also energy, which is modeled according to the details described in Section 3.5. Although it is necessary to include the battery capacity as input for each operation in such cases, this detail was not presented in the maximum structure, as it would have significantly reduced the clarity of the structure. The charging time is not specified during the parameterization of the model but is determined during the solution process, so in the current example, reducing the initial battery capacity ensures that AGV1 needs charging.

With the extra charging time considered, the P-graph solver provides the schedule shown in Figure 29, corresponding to the previously presented solution structure on Figure 27. It is evident that the initial delay caused by charging leads to AGV1 having to wait less on the shorter X12 → L → K → I → X6 route; as a result, the optimal solution now includes this route for serving task T1, which is completed in 82.29 s, and task T2, which is completed in 65.26 s.

Figure 29.

Representation of the optimal solution of the case study in the Gantt chart, in the case when AGV1 requires additional charging at the beginning of the schedule.

The AGVs follow the same routes as in the second solution; therefore, the energy consumption remains unchanged. The charging time is added to the completion time of task T1; therefore, the value of the objective function is given as follows:

Table 7 illustrates the time and energy requirements of the three presented solutions and the resulting objective values.

Table 7.

Comparison of the three presented solutions.

5. Discussion

The alternative scenarios presented in the case study demonstrate that the proposed integrated routing, scheduling, and energy management methodology effectively evaluates various options. It shows how task assignment, collision avoidance, and battery charging requirements result in distinct mission plans for the fleet.

The case study further illustrates that combining multiple objective functions can lead to solutions that perform better in one aspect but worse in another. The final ranking is determined by the assigned weighting factors. In the presented comparison, the second route plan consumes slightly more energy, while its execution time degrades more significantly. If energy consumption were assigned double the weight, the ranking of these two solutions would be reversed.

The case study presents a smaller example as an illustration, for which the related P-graph structures were manually drawn using the P-graph Studio software version 5.2.5.0. In the case of a large number of transport demands, cells, and possible routes, the graph is only constructed algorithmically as a data structure without graphical elements, based on which the MILP model describing the P-graph model can be generated. The model generation algorithm can be implemented based on the modeling steps presented in Section 3.4, enabling the full automation of the scheduling and routing problem.

For the presented case studies, the computational time for the entire automated algorithmic process is under two seconds on a laptop. However, solving routing, scheduling, and resource allocation problems simultaneously is computationally demanding. When dealing with a large number of open tasks, a viable strategy is to split the problem into two levels, and prioritize the tasks at the upper level based on deadlines and importance to include only those that realistically fit into the current planning horizon [12]. This approach ensures fast execution of the computation at the lower level, even when handling thousands of tasks.

As a future research direction, a trajectory optimization procedure is to be developed that supports the free movement of vehicles within safety zones. It aims to simultaneously minimize the required control effort and energy demand for maneuvers spanning multiple cells.

6. Conclusions

The problem addressed herein concerns the simultaneous optimization of routing and scheduling for AGVs, coupled with explicit energy management. The proposed methodology begins with a geometric abstraction of the warehouse environment. By decomposing the floor plan into discrete spatial regions, the model enforces a mutual exclusion constraint where each zone can be occupied by only a single AGV at any given time to guarantee safe and conflict-free navigation. In contrast to conventional segment-based traffic regulations, the region-oriented representation maintains the flexibility of autonomous free movement within each spatial region.

Transit points and points of interest are defined to serve as feasible entry, exit, and service nodes in the routing graph to consistently estimate travel times and energy demand of AVG operations. A routing graph is established to encapsulate all feasible vehicle trajectories within the facility. The edges of this network represent executable maneuvers, with traversal times derived from vehicle-specific kinematics—including velocity and acceleration limits. Crucially, these trajectories are not predetermined; rather, they remain decision variables within the optimization framework, allowing for flexible movement within each spatial region.

These routing options are converted into a process network where movements function as activities. Formulated as a TCPNS problem, the model defines AGVs and spatial regions as resources, meaning an activity can proceed only if its required resources are free. This approach naturally incorporates vehicle availability and the mutual exclusion of conflicting paths into the core of the optimization process.

The proposed approach uniquely spans the five dimensions aimed, bridging gaps found in previous studies. Specifically, it unifies collision avoidance, motion feasibility, and dynamic routing with mission-level scheduling and energy management within a single optimization scheme by the TCPNS (Time-Constrained Process Network Synthesis) formalism.

A key feature of the model is the explicit integration of energy constraints; it evaluates energy requirements based on path selection while considering the real-time battery status of the AGVs. The framework further enhances operational flexibility by incorporating optional charging intervals, ultimately yielding a robust execution plan that prioritizes energy sustainability.

The alternative scenarios explored in the case study confirm that the proposed integrated framework effectively evaluates diverse operational configurations. The results illustrate how the interplay of task assignment, collision avoidance, and battery charging requirements yields distinct, feasible mission plans for the AGV fleet. Furthermore, the analysis highlights the inherent trade-offs between competing objective functions, where the final solution ranking is sensitive to the assigned weighting factors.

The proposed solution is built upon a modular framework that is fully algorithmic and automated from end to end. A key advantage of this architecture is that its individual components, such as the trajectory planning algorithm, remain interchangeable, allowing for seamless upgrades to more advanced versions in the future.

7. Future Work

Moving forward, trajectory planning is to be further developed to enable vehicles to move freely in any direction within cells, subject to safety constraints and required orientations of vehicles at entry and exit points. An optimization model must be developed for trajectory planning that ensures vehicles arrive at their destinations on schedule while minimizing accelerations affecting the vehicle and cargo, along with the energy demands associated with the control interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., M.F. and K.K.; methodology, K.K.; formal analysis, M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B., M.F. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, B.B., M.F., K.K. and P.S.V.; supervision, B.B.; project administration, P.S.V.; funding acquisition, B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office within the project TKP2021-NVA-23.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| FTSN | Flexible Time-Space Network |

| HTN | Hierarchical Task Network |

| LNS | Large Neighborhood Search |

| MAGV | Multi-Automated Guided Vehicle |

| MOPSO | Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization |

| M-MOPSO | Modified Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PN | Petri Net |

| PNS | Process-Network Synthesis |

| RRT | Rapidly-exploring Random Tree |

| TCPNS | Time Constrained Process-Network Synthesis |

References

- Nishi, T.; Maeno, R. Petri Net Decomposition Approach to Optimization of Route Planning Problems for AGV Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2010, 7, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Gu, C.; Yin, X.; Liu, C.; Huang, H. Time window based path planning of multi-AGVs in logistics center. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID), Hangzhou, China, 9–10 December 2017; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Chen, J.; Yuan, P. Collision-Free Route Planning for Multiple AGVs in an Automated Warehouse Based on Collision Classification. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 26022–26035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lv, L.; Shi, Y. A bi-level path planning algorithm for multi-AGV routing problem. Electronics 2020, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P. AGV Scheduling and Path Planning Considering Opportunistic Charging Process. Int. Core J. Eng. 2022, 8, 523–538. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, S.; Moghdani, R.; Maghsoudlou, H. Energy-efficient multi-objective flexible manufacturing scheduling. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Wei, L.; D’Ariano, A.; Zhang, F.; Negenborn, R. Flexible time–space network formulation and hybrid metaheuristic for conflict-free and energy-efficient path planning of automated guided vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liao, Q.; Xiong, C.; Chen, J.; Li, S. A novel metaheuristic approach for AGVs resilient scheduling problem with battery constraints in automated container terminal. J. Sea Res. 2024, 202, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barany, M.; Bertok, B.; Kovacs, Z.; Friedler, F.; Fan, L.T. Solving vehicle assignment problems by process-network synthesis to minimize cost and environmental impact of transportation. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2011, 13, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertok, B.; Bartos, A. Renewable energy storage and distribution scheduling for microgrids by exploiting recent developments in process network synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frits, M.; Bertok, B. Routing and scheduling field service operation by P-graph. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 136, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frits, M.; Bertok, B. Scheduling custom printed napkin manufacturing by P-graphs. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 141, 107017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Cánovas, L.; Pelegrin, B. Algorithms for the decomposition of a polygon into convex polygons. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 121, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, F.; Tarjan, K.; Huang, Y.; Fan, L. Combinatorial algorithms for process synthesis. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1992, 16, S313–S320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, F.; Orosz, Á.; Losada, J.P. P-Graphs for Process Systems Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado, G.R.; Cabezas, H. Sustainability in the Design, Synthesis and Analysis of Chemical Engineering Processes; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niemetz, N.; Kettl, K.H.; Eder, M.; Narodoslawsky, M. RegiOpt conceptual planner—Identifying possible energy network solutions for regions. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2012, 29, 517–522. [Google Scholar]

- Sandor, N.; Eder, M.; Niemetz, N.; Kettl, K.H.; Narodoslawsky, M.; Halasz, L. Optimizing the energy link between city and industry. Chem. Eng. 2010, 21, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- How, B.S.; Andiappan, V.; Aviso, K.B.; Migo-Sumagang, M.V.; Tan, A.S.T.; Tan, R.R. P-graph approach for optimal carbon trading with cost and time constraints. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 9003–9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Éles, A.; Halász, L.; Heckl, I.; Cabezas, H. Evaluation of the energy supply options of a manufacturing plant by the application of the P-graph framework. Energies 2019, 12, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.