Abstract

Far offshore wind resources are important for reaching the global renewable energy and decarbonization objectives, but great distances to shore and deep waters preclude underwater electricity lines or traditional turbine or platform foundations. At these distances, converting the produced electricity to hydrogen via electrolysis of purified seawater is attracting interest. This hydrogen can then be transferred with fewer losses via undersea pipelines or transported to shore via ships. The difficulties of storing and transporting hydrogen over large distances can also be remedied by converting it into easily transported “e-fuels”, such as methanol and ammonia. The paper summarizes the current literature in terms of technologies and strategies involved in these renewable fuel production processes and highlights power consumption, efficiency, and levelized cost figures. These renewable e-fuels promise an environmentally friendly method of tapping into vast overseas resources that can be utilized on shore or provided to sea vessels for refueling. However, electrolyzer, synthesis reactor, and deep-water foundation or floating platform costs need to be brought down significantly by research and development before they can become commercially feasible in the coming decades.

1. Introduction

Renewable electricity production from offshore wind energy has grown by more than 20% successively in the last few years, and the industry has set a target of 380 GW installed offshore capacity by 2030 to match the worldwide efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 °C [1]. At present, the majority of offshore wind power investments, including recent offshore wind farms in the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and the South of China, are installed—and continue to be installed—in waters up to 40–50 m in depth [2]. Only a handful of offshore wind farms push for distances between 105 and 120 km from the shore [3].

Deeper waters offer an untapped, rich source of renewable energy. The advantages of offshore wind energy—stronger winds, higher capacity factors, and less noise and visual pollution—are even more applicable at water depths beyond 50 m, where many of today’s offshore turbine foundation techniques cannot be applied [3]. Furthermore, transferring the produced electrical energy back to shore starts to become an issue. As the distance to shore increases, transfer via undersea cables becomes prohibitively inefficient. At distances up to 20 km, HVAC cables and transfer technologies are employed to overcome these disadvantages; further away, up to 40 km, HVDC technologies are utilized to transfer the produced energy back to the shore with acceptable efficiency [4,5]. Still, greater distances to shore and deeper waters offer more intense and plentiful wind energy resources, and at these distances, alternative methods and technologies must be employed if these renewable energies are to be utilized.

The major alternative in this regard, both in terms of research volume and available literature, is to utilize electrolysis technologies to convert the electricity into green hydrogen. Seawater is desalinated and purified using various methods on offshore platforms, and the resulting demineralized water is electrolyzed to split it into hydrogen and oxygen. Beyond this point, there are various methods to store and transfer these two gases, either as-is or in a further developed form. It is possible to utilize the resulting hydrogen as a building block for the production of more complex alternative fuels, such as methanol and ammonia, with the addition of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, respectively, which have also garnered interest as potential replacement industrial and maritime fuels. These so-called “e-fuels” are expected to reach a market size of 17 Mtoe for the maritime industry and 44–62 Mtoe overall by 2030 [6], in line with industry efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 20–30% by 2030 and 70–80% by 2040 and reach “net zero” by 2050 [6].

This paper does not discuss the economic utilization of high-purity oxygen, a by-product of electrolysis, which can also be sold to various industries, but rather aims to present a review of the current literature on producing hydrogen through various methods on offshore wind farms and platforms, as well as further processing this hydrogen into methanol, a low-carbon alternative fuel for various industries and land/sea transport, or into ammonia, the main building block of fertilizers commonly used in agriculture worldwide, as well as another alternative fuel and energy carrier. Methods for temporarily storing the separated hydrogen—which requires a great amount of compression or condensation into a liquid through an energy-intensive process to be stored effectively on an offshore platform with limited space—and the synthesized methanol or ammonia (which are much easier to store and transport, thanks to being (or being easily converted to) more conveniently transferred liquids will also be briefly discussed.

1.1. Literature Review

In order to produce a comprehensive yet concise review of offshore hydrogen and e-fuel production articles, the authors’ literature review began with searches for related keywords on Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and MDPI websites, with a focus on relevant articles from 2019 onward. The main objective during article selection was to provide a wide-ranging, global picture of the expansion of offshore wind power and the conversion of this electricity to alternative fuels. Several articles discussing the basics of offshore wind energy production and utilizing seawater, either purified or directly, in electrolysis, were included to provide a concise introduction to the field. Papers that established the foundations for the research area were also included in the review to provide a sense of how research has evolved over time. To provide another focus to the review while staying true to the global scope, recent articles on the use of hydrogen and e-fuels in maritime and aviation industries were included to direct attention to these industries’ decarbonization efforts.

1.2. Article Relevance

The literature includes a high number of papers on offshore wind energy production after decades of interest, investment, and expansion into farther distances from shore and deeper waters. The possibility of producing hydrogen by bringing together electricity produced from offshore wind and purified seawater is also well-studied. However, articles investigating the conversion of this hydrogen to further developed e-fuels are sparser. There are also relatively few articles on the suitability of these green e-fuels in the maritime and aviation industries. Finally, articles conducting technoeconomic analyses to provide levelized costs are spread over more than a decade of research and are located in distant locations in the world. The authors aim to provide a global outlook of contemporary research into offshore e-fuel production with a wide range of articles and installation locations covered, comparable LCOE and LCOH figures, and insights into how these e-fuels can transform maritime and aviation industries to fit into a decarbonized future to make a valuable contribution to the field and provide researchers with a good starting point.

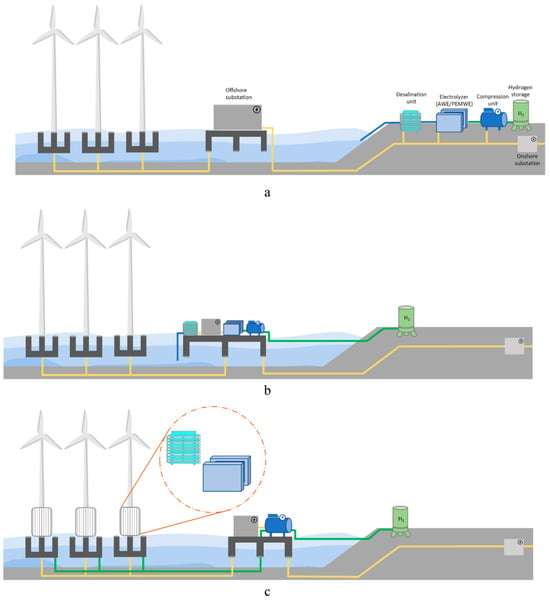

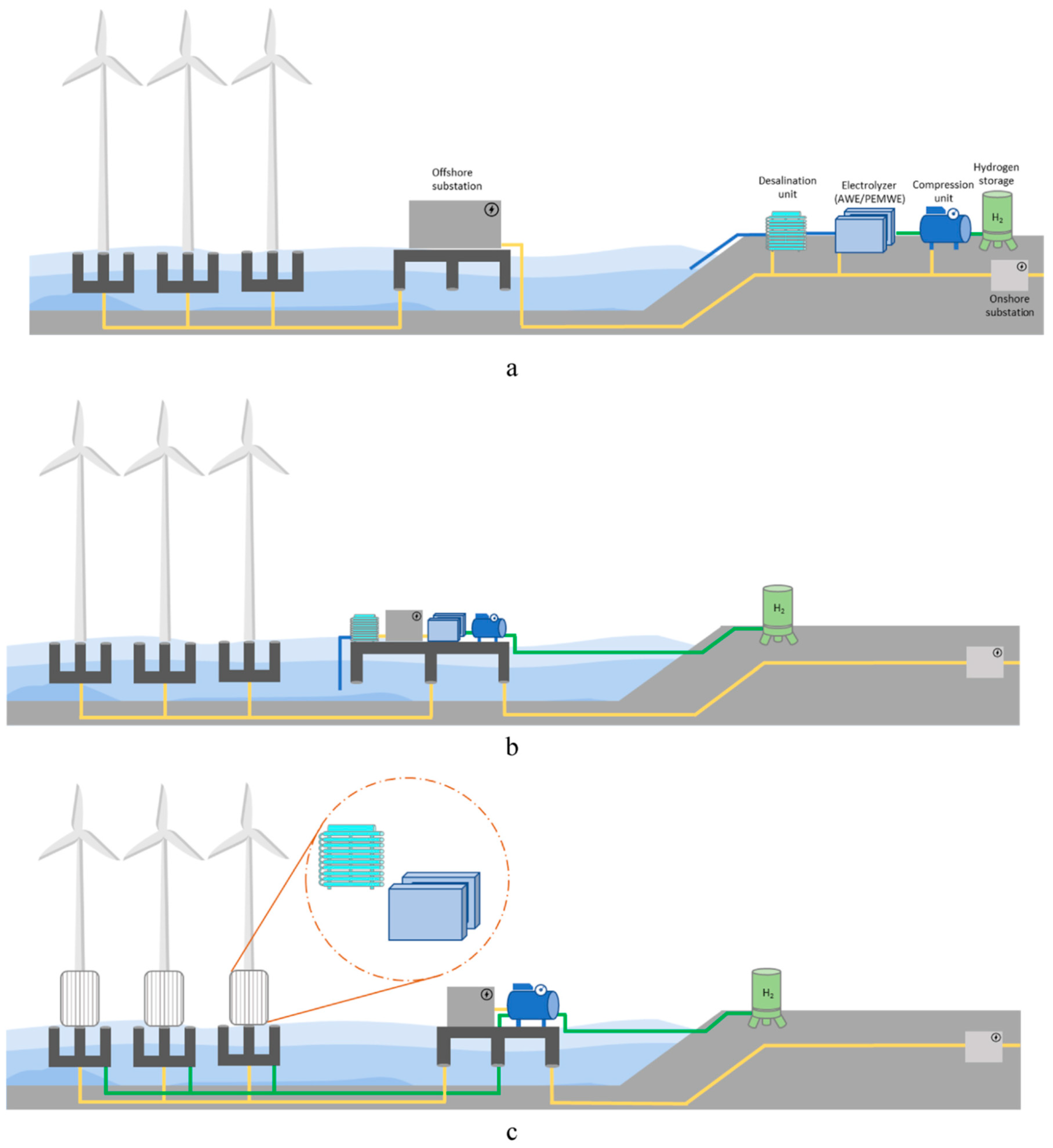

2. Producing Green Hydrogen from Offshore Wind

A wide range of literature is present on the production of green hydrogen through electrolysis powered by offshore wind energy. These numerous papers and articles can be categorized according to which technical and economic aspect of green hydrogen production they focus on, which industries or geographies they investigate, or their overall opinion on the technological process. Many of the papers also investigate the optimum location for the electrolysis to take place — whether the electrolyzers will be located onshore, connected to the wind farm by electric cables, offshore, on a central platform, or offshore, with separate electrolyzers in each turbine. These main topologies are shown in Figure 1.

2.1. Early Literature on Offshore Hydrogen Production

One of the earliest papers on the topic is by Matzen, Alhajji, and Demirel [7], where the authors introduced hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia as possible future replacement fuels, discussed the technical and economic possibilities for production, and inspected the sustainability of these processes, comparing hydrogen produced from offshore wind energy with hydrogen produced from natural gas or syngas. The paper points out that even though “green” production methods prove to be more expensive compared to other sources (production of hydrogen was responsible for a large part of the e-fuels’ costs), their contribution to the reduction in carbon emissions is highly important. The paper stated that even though the round-trip efficiency of storing energy in chemical form is low (the paper states efficiency figures of around 35%), the ability to store energy for long periods of time is a big advantage.

Loisel, Baranger, Chemouri, Spinu, and Pardo also studied a hybrid offshore wind power and hydrogen storage system in 2015 [8], where they investigated various scenarios of integrating H2 production, storage, and distribution into a 1000 MW wind farm at Belle-Ile Island, France. They sought to alleviate wind power curtailments and grid constraints at the wind farm by producing hydrogen and utilizing it in power-to-gas, power-to-mobility, and power-to-power routes. In their study, the cost of hydrogen production ranged from 4.2 to 47.1 €/kg, and every considered scenario resulted in a negative Net Present Value (NPV), implying that the scenarios are not profitable. The authors stated that the benefits from such an investment would be in carbon savings and grid flexibility, as well as energy independence, rather than economic savings. The study concluded that cost reductions by further R&D, harmonization of industry standards, supportive environmental policies, and taxation of high-carbon energy sources could make such investments more feasible in the future.

Another early paper focusing on the far offshore wind energy potential for the production of hydrogen was by Babarit et al. [9], which proposed a fleet of hydrogen production vessels that utilized wind energy in deep waters to produce hydrogen and bring it back to shore for commercial utilization. The paper presented the enormous far offshore wind energy potential, discussed potential vessel designs for energy production, and explored how the produced energy could be stored on the vessels before it was offloaded on shore. The paper suggested that there could be a market for green hydrogen produced by this method if it could be sold at 3 to 5 €/kg; production costs were expected to exceed this amount in the short term, but over a longer period, with reductions in equipment costs and the presence of supportive mechanisms, such as subsidies or carbon taxes, such an investment could be economically feasible. This was followed by Crivellari, Cozzani, and Dincer’s work from 2019 [10], which inquired into the commercial feasibility of repurposing already built offshore platforms for hydrogen production, where the decommissioned Thebaud offshore platform off the Nova Scotia (Canada) coast was studied.

Figure 1.

Three main plant topologies for offshore hydrogen production: (a) onshore electrolyzer; (b) offshore electrolyzer; and (c) decentralized electrolyzer by Ramakrishnan et al. [11]. For near-shore wind installations, it may make more sense to transport the produced electricity to the shore and produce hydrogen on land. As the distances and sea depths increase in far offshore wind farms, electrolyzers are better off installed in the wind farms themselves, either as a central large facility or as smaller, independent electrolyzers in each wind turbine.

Figure 1.

Three main plant topologies for offshore hydrogen production: (a) onshore electrolyzer; (b) offshore electrolyzer; and (c) decentralized electrolyzer by Ramakrishnan et al. [11]. For near-shore wind installations, it may make more sense to transport the produced electricity to the shore and produce hydrogen on land. As the distances and sea depths increase in far offshore wind farms, electrolyzers are better off installed in the wind farms themselves, either as a central large facility or as smaller, independent electrolyzers in each wind turbine.

2.2. Studies Focused on Establishing LCOE and LCOH

Many of the techno-economic studies on the topic of hydrogen production from offshore wind focus on establishing the levelized cost of hydrogen, the cost to produce 1 kg of hydrogen at the proposed facility, or the production method. These calculations began with the determination of the levelized cost of energy, which is the electricity produced from the offshore wind farm driving the electrolysis process. A paper by Franco, Baptista, Neto, and Ganilha from 2021 [12] compared production and exportation pathways of hydrogen produced offshore. The paper compared costs for transferring the produced electricity to shore via DC cables and producing hydrogen onshore, producing H2 on an offshore platform and delivering it to shore via a pipeline after compression or by vessels after liquefaction, and converting the hydrogen produced offshore into NH3 by adding nitrogen or into liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) and either delivering via pipelines or shipping by vessels to shore. The paper assumed a leveraged cost of electricity (LCOE) of 50 €/MWh, dropping in the future to 20 €/MWh, and found capital expenditures (CAPEXs) ranging from 175 M€ (by transferring NH3 or LOHC via pipeline) to 230 M€ (by transferring the electricity onshore via DC cables) and leveraged costs of hydrogen ranging from 5.2 €/kg H2 (by producing the hydrogen with offshore electrolyzers and transferring the compressed H2 via pipelines) to 7.25 €/kg H2 (by converting the hydrogen into LOHC or NH3 and shipping via vessels to shore). The paper suggests these values could be halved after technological developments and scaling up hydrogen production, with the possibility to decline further to around 40% of the initial projected values with strong financial support, such as support from the EU hydrogen deployment program. The paper concludes that the wind farm’s distance to shore is the decisive factor for choosing between onshore or offshore electrolysis, that this choice would lean further towards offshore in the future, and that at present, conversion of H2 into NH3 or LOHCs does not seem to offer tangible benefits in LCOH.

Calado and Castro presented the current electrolyzer technologies and state of the offshore wind farms in operation at the time, and introduced the distributed, centralized, and onshore configurations for electrolysis using electricity from offshore wind farms in their 2021 article [13]. The authors also presented use cases for hydrogen. Singlicito, Ostergaard, and Chatzivasileiadis suggested, in their 2021 paper investigating offshore electricity and hydrogen hubs [14], that unit hydrogen costs could be lowered as far as 2.4 €/kg for offshore hydrogen production, which would make it on par with producing hydrogen from natural gas. The paper went on to state that accounting for savings due to avoided grid extensions can drive the costs further down to the level of 1.75 €/kg.

Another techno-economic analysis by Rezaei, Akimov, and Gray [15] located the offshore wind farm off the Australian coast and hydrogen production on the continental island, but provided globally applicable insight by simulating two “development scenarios”. The paper provided a novel approach to estimating the overall electrolyzer efficiency by adopting a dynamic renewable hydrogen production model to address the fluctuation of plant and electrolyzer stack efficiencies with changes in the level of utilization, and strove to faithfully replicate real-world economies of scale and cost modeling. The study assumed two scenarios for the future: an optimistic outlook with high demand for renewable hydrogen and a pessimistic forecast with low demand. The low-demand scenario placed the total hydrogen demand in 2050 at 118 Mt. The fast-development scenario assumed that the total demand would reach 660 Mt in the same year. Through analysis of the capacity factor of selected locations off the Australian coast and the utilization rate of the plant, while also utilizing the model for the fluctuation of overall electrolysis efficiency, the study found that the slow-development scenario would result in an LCOH of at least 5.1 $/kg by 2040, missing the DOE target, while the fast-development–high-demand scenario could drive the LCOH down to 3.3 $/kg at the best plant location, making renewable hydrogen competitive with natural gas reforming.

Similarly, a 2024 study by Ding, Fu, and Hsieh [16] investigated a theoretical installation in the Taiwan Strait but aimed to provide globally relevant results. The study was based on PEM electrolyzers with a base efficiency of 73.6%; the efficiency increased annually by 0.25% with advances in technology, but the electrolyzers also suffered from yearly stack degradation. The study evaluated the three hydrogen production topologies shown in Figure 1, with a wind farm comprised of 31 turbines at 9.5 MW capacity each, totaling 294.5 MW for the wind farm. The produced electricity, or hydrogen, was transported to the island of Taiwan by HVDC lines or a hydrogen pipeline. Through Net Present Value, sensitivity, and Monte Carlo uncertainty analyses, the study found LCOH values of 11.1 $/kg for centralized production, 9.8 $/kg for distributed production in each turbine, and 11.3 $/kg, the highest in the study, for onshore electrolysis. These LCOH values were projected to decrease by around 20% by 2035 with advances in technology, allowing the investment to pay for itself in 9 years (12 years for the onshore scenario) with a hydrogen selling price of 9 $/kg. The study also clearly showed that as the distance to shore increases, the costs for onshore electrolysis increase more than those for centralized or distributed production.

In contrast to papers that foresaw that most of the hydrogen produced from offshore wind energy would be electrolyzed offshore, Gea-Bermùdez et al. stated in their 2022 paper [17] that they expected onshore electrolysis to provide more socio-economic benefits in the near future, up to 2050. The study took into account various scenarios until 2050, including a “base” scenario with commonly foreseen technical improvements, cost reductions, and hydrogen demand, as well as alternatives where all of the electrolysis was made offshore, excess heat from onshore electrolysis was not utilized for residential heating, offshore caverns could be utilized for hydrogen storage, all generated electricity would be used in electrolysis, and electrolyzer costs declined at a decreased rate. At the highest rate, when all those scenarios were applied in combination, the optimization algorithm allocated 26% of hydrogen generation to offshore platforms, while in the base scenario, in 2045, only 2% of hydrogen generation would be more feasible offshore rather than onshore. The study instead advised associating hydrogen production with the amount of generated photovoltaic electricity, establishing electricity transmission lines to transfer the electricity generated offshore to the mainland, and utilizing hydrogen pipelines only for far offshore wind generation areas. The study concluded that when a holistic, socio-economic approach was taken instead of a techno-economic analysis, it could be seen that producing hydrogen onshore on electrically connected “energy islands” is the most beneficial route.

The resulting LCOH values from all referenced papers are displayed in Table 1 further in the article.

2.3. Studies Focused on Transportation and Industries

Articles that aimed to determine the suitability of offshore hydrogen for transportation, by land, sea, or air, as well as other industries, were also present in the literature. Galimova et al. [18] began their comparison by stating an important fact: sea and air transport are under the same pressure as other industries for decarbonization and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but both of these sectors require energy-dense fuels to take as little space and weigh as little as possible during voyages, and are especially difficult to electrify. Both marine and aviation industries are set to grow in the aftermath of the pandemic and show strong growth indicators up to the 2050s. The authors also drew attention to the differences between the industries: the aviation industry is more customer-facing, with passenger demands more directly influencing operations. Industry standards are centrally established and rapidly applied, and with two major manufacturers, changes can be implemented more quickly and decisively. In contrast, the maritime sector is not directly in the public mind when it comes to decarbonization efforts; with many independent manufacturers, port operators, and industry unions, changes are decided upon and implemented more slowly. Newly developed, environmentally friendly fuels’ compatibility with existing marine engines is very important for their successful introduction to the market. Therefore, these two sectors require different approaches in the decarbonization challenge. For aviation, the two main contenders were hydrogen and e-kerosene—while there were trials of battery-powered flight, these could not provide the long-distance capabilities required by intercontinental routes. E-LNG and e-methanol did not offer sufficient energy density to be valid options. Hydrogen was one possible future fuel, but at the time, the industry was leaning towards e-kerosene and bio-kerosene as drop-in low-GHG fuels. In both cases, a major decline in electrolysis costs was expected in the 2040s to make these options economically viable. The marine industry could afford more choices in environmentally friendly fuels due to larger storage space and less dependence on low weight. Herem battery-powered vessels were a more feasible approach, but the industry was, again, leaning toward liquid fuels. E-ammonia and e-methanol were leading candidates, with e-ammonia offering lower overall costs for the industry. When carbon emission taxes were applied, however, hydrogen took the lead in total costs and was expected to be a major option, especially with the maturing of electrolyzer options and reductions in costs.

A 2021 paper by Bonacina, Gaskare, and Valenti [19] studied the techno-economic prefeasibility of providing hydrogen fuel, produced from offshore wind through seawater purification and electrolysis, to maritime transportation in the Mediterranean. The study formed a general outlook on the sea traffic around the Mediterranean, established the components of a dedicated wind farm with electrolysis, liquefaction, and storage facilities, and considered several locations where such an installation would make economic sense. After the parametric economic analysis, the paper established the payback time of the investment between 9 and 15 years based on hydrogen prices from 5 to 7 €/kg. The study expected the mean cost of hydrogen production via wind energy and electrolysis to drop down to around 3 €/kg, in line with IEA’s assumptions from 2019 to 2060, but pointed out that this would still be higher than the estimated cost of hydrogen produced from natural gas and coal with carbon capture, and economies of scale should be applied to drive down the cost of green hydrogen even lower. The study was still optimistic about the role such facilities may play in the decarbonization of the maritime sector.

Serrano et al. [20] took a different approach and studied the applicability of oxy-fuel combustion (OFC), which is the consumption of fuel with pure oxygen carried in the vessel, with e-fuels. Obviously, marine vessels were a better fit for this technology as airplanes could not efficiently carry the required oxygen in flight. Apart from providing cleaner combustion, OFC allowed for the economic utility of the pure oxygen side-product of electrolysis. When combined with carbon capture, oxy-fuel combustion of biodiesel effectively resulted in negative carbon emissions, and biodiesel was a drop-in fuel that could easily be integrated into existing vessels. However, widespread adoption of biodiesel required the allocation of large farmlands for biodiesel-focused agriculture. Blue ammonia, with carbon capture, was a much better fit with OFC in regard to carbon emissions, but required more energy input for the capture process. The authors again highlighted the expectation of cheaper electrolyzed hydrogen for their 2050 outlook, which would increase the preferability of e-methanol. In the end, they proposed a blended pathway with both e-diesel and biodiesel utilized in a circular-economy model; carbon capture allowed this to be a closed-cycle for carbon, and OFC could help with achieving cleaner combustion and lower emissions as an interim measure.

A 2021 paper by McKinlay, Turnock, and Hudson [21] also examined the outlook for environmentally friendly fuels for maritime use, but the authors specifically aimed for “zero emissions” instead of reduced GHG emissions. The reason behind this was a proposal by the UK government, which stated that by 2025, all newly made vessels should have “zero emissions propulsion capacity”. The paper therefore focused on hydrogen, ammonia, and methanol with carbon capture as future zero-emission fuels. The paper also proposed that all these fuels should be used with a fuel cell instead of combusted in an engine to increase energy conversion efficiencies from around 40% to 55–60%, lower NOx emissions, and facilitate carbon capture for methanol. A comparison of these chemicals’ current production versus the required amount to power 50,000 ships revealed that hydrogen production would have to be scaled up to 171% of current production levels to fulfill the new demand; this ratio was 391% for ammonia and 859% for methanol, despite hydrogen being the chemical with the least actual production in the comparison. The paper also debunked the idea that hydrogen offered too low volumetric efficiency to be viable for long voyages, especially with cryogenic storage; however, methanol still stood out as the best solution for volumetric efficiency. Given that both ammonia and methanol required additional steps for synthesis and that these steps were harder to bring down to zero emissions, the paper proposed hydrogen as the ideal zero-emission fuel for future maritime transportation, but noted that it had complex storage requirements. The paper also mentioned the high toxicity and corrosion of ammonia and the carbon-capture requirement of methanol as drawbacks.

Lindstad et al. [22] compared five e-fuels proposed for future maritime use—e-hydrogen, e-ammonia, e-diesel, e-LNG, and e-methanol—from a well-to-wake greenhouse gas and total energy use perspective. The authors assumed that all electricity used in the electrolysis and synthesis of the studied e-fuels came from renewable sources and was emission-free. The cost for this renewable electricity was assessed as the main reason these e-fuels were much more costly at the time compared to fossil fuels; the authors stated that these costs would decrease in the future with the increase in renewable energy production, but there would also be many industries competing for the limited supply of renewable energy. The most efficient e-fuels from an energy use point of view were determined to be e-hydrogen and e-ammonia; for e-diesel, e-LNG, and e-methanol, switching to emission-free synthesis might in fact double or triple the well-to-wake total energy consumption for the same chemical energy. The authors proposed that narrowly focusing on an aggressive reduction in maritime emissions might in fact be counterproductive to global efforts for decarbonization, and utilizing dual-fuel engines to provide flexibility in fuel selection and increase compatibility with existing vessels might be better suited to lowering risks and preparing for the growing supplies of energy-efficient and emission-free e-fuels.

In numerous recent publications on the topic by energy agencies [23], alliances [24] and councils [25], engineering consultants [5,26,27], and manufacturers of hydrogen production and compression equipment [28] targeting the general public and business partners, it is possible to note that the potential to produce green hydrogen offshore is attracting public and industrial interest.

2.4. Feasibility Studies for Geographic Locations

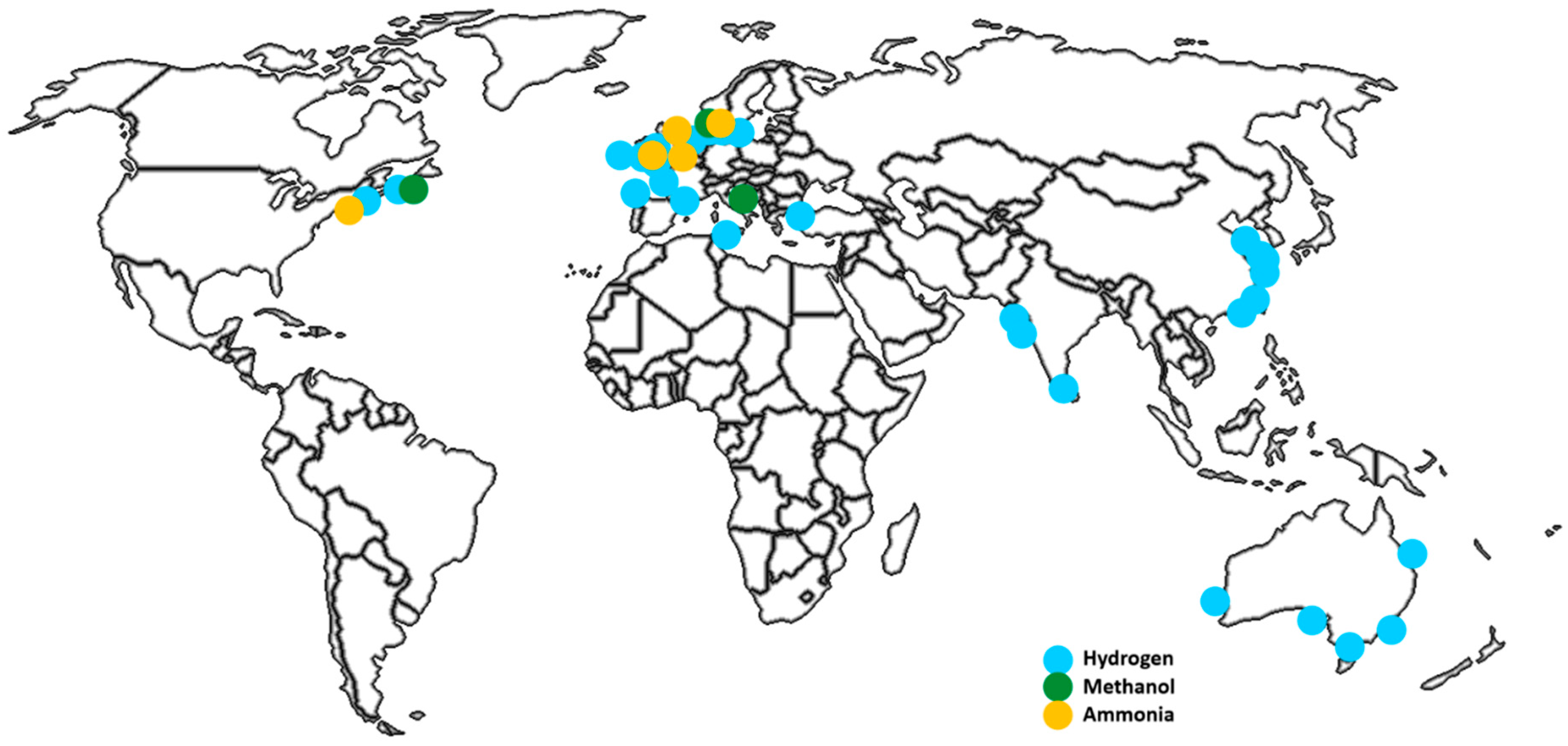

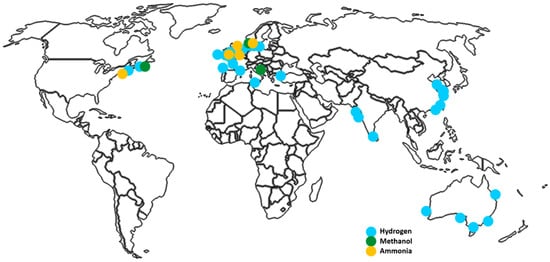

There are also reports and analyses aimed at determining how suitable offshore wind and hydrogen production investments are for specific regions and pointing out the best methods for production in these areas. These studies are marked on Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Wind farm locations investigated in covered articles on the offshore production of hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia. Authors’ work.

A case study by Dinh, Leahy et al. [29] investigated a hypothetical 101.3 MW offshore wind farm incorporating underground hydrogen storage off the East Coast of Ireland. Their Discounted Payback and Net Present Value flows for storage scenarios and the viability model suggested that such a system would be feasible in 2030, assuming a hydrogen sale price of 5 €/kg. A 2021 study by Luo, Wang, and Pei [30] discussed hydrogen production from electricity produced at an offshore wind farm in South China and introduced the onshore and offshore electrolysis options also discussed in other papers. The paper is optimistic, concluding that selling the produced hydrogen could offer higher economic benefits than selling the wind farm’s electricity without subsidies.

A recent paper by Rogeau, Vieubled et al. [31] focused on finding the best ways for various European countries to benefit from producing hydrogen using offshore wind energy. The paper discussed centralized and decentralized hydrogen production options with the electrolyzers located onshore or offshore and suggested that, in the future, moving hydrogen production to offshore platforms would make more sense. Countries bordering the North and Baltic Seas have much more economically feasible offshore wind energy potentials, whereas the Mediterranean Sea offers less dense energy resources. Cost estimates in the paper implied that green hydrogen could be produced at less than 3.0 €/kg by 2030 and less than 2.0 €/kg by 2050, and the paper provided cost evolution graphs for nine European countries for different configurations and connection technologies.

Glaum, Neumann, and Brown [32] highlighted the EU’s plans to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and the premise of building an energy hub in the North Sea; the authors pointed out that utilizing floating wind energy turbines and establishing international hybrid or meshed grid connections would be necessary to achieve this objective, and included both energy and non-energy sectors in their analysis. Through offshore energy, turbine cost, and wake effect modeling, the paper calculated capacity factors and costs per kW of electricity, moving on to investigating the possible offshore hydrogen network and proposing four topologies: a P2P power network without hydrogen infrastructure, taken as a reference; a meshed power network without hydrogen infrastructure; a P2P power and hydrogen network; and a meshed power and hydrogen network. The study found that integrating a hydrogen network lowered the need for offshore transmission infrastructures and significantly reduced curtailment. The study proposed that most of the electrolysis should take place offshore, mainly owing to the high offshore HVDC transmission platform costs, and suggested that integrating offshore wind energy and hydrogen production in a meshed network in the North Sea with solar energy production in South Europe and possibly hydrogen imports from North Africa could provide the necessary reliable and safe supply of renewable energy to Europe.

A 2023 report by Arthur D. Little [5] stated that offshore wind and hydrogen integration was “a cornerstone of EU decarbonization”; the report pointed out the advantages of this integration in terms of higher production stability, increased energy generation, growing financial incentives, and geographical expansion and integration opportunities. The report pointed out that hydrogen’s low round-trip efficiency made it a poor candidate for electricity production, but its advantages in long-term storage of energy and, if necessary, balancing grid demands were valuable. The report established various methods of producing hydrogen from offshore wind, using onshore/offshore and centralized/decentralized electrolyzers, and divided European countries into three broad categories: those who would lead decarbonization, those with a high potential for decarbonization, and those who would import green energy. Most of the studies on the potential of offshore hydrogen production in Europe mentioned the importance of “energy security” in the aftermath of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and the cut-off of Russian natural gas.

A paper by Patidar, Shende, Baredar, and Soni of the Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology [33] aimed to introduce the production of hydrogen from offshore wind energy to Indian readers. The paper highlighted the most favorable sites off the Indian Coast for such an investment, suggested that advancements in this area could make India a dominant force in the offshore wind energy market, and offered various routes to integrate hydrogen production with offshore wind energy. The paper concluded that offshore wind energy, coupled with hydrogen production, held immense possibilities for the energy transition of India into a low-carbon future, but required wide collaboration between stakeholders, policy makers, and civil society for realization.

Scolaro and Kittner [34] studied the optimization of hybrid offshore wind farms with a focus on the German energy market and bidding mechanisms. Their paper calculated the most beneficial sizing of electrolyzers and the optimal bidding mechanism to benefit from higher rates for ancillary services, frequency regulation, and periods of high demand. The paper provided details on the German tariffs and taxes for the electricity market and found that the lowest costs for hydrogen, 4.9 €/kg, were obtained when electrolyzer capacity was around 87% of the wind farm’s electricity production capacity. The paper also investigated the possibility of adding a fuel cell to the production plant to benefit from higher electricity rates during peak hours, but found that the low round-trip efficiency of power-to-power conversion made it harder to justify this investment, also noting that carbon abatement subsidies could also be applied to hydrogen production equipment to make them more attractive for investors.

Groenemans et al. [35] investigated an offshore hydrogen production plant to be built off Cape Cod in Massachusetts. The study compared the costs of electricity produced at an offshore wind farm and carried onshore via high voltage AC to the cost of hydrogen produced offshore at the same wind farm. The paper pointed out that if the electricity required for electrolysis was purchased from the power grid, with an electricity consumption of 50 kWh/kg hydrogen at a rate of 0.06 $/kWh, this alone would lead to an energy cost of 3 $/kg. The paper also assumed that electrolysis costs would decline rapidly with future R&D, falling from 300 $/kW to 100 $/kW. With these decreased electrolysis costs and a 560 MW wind farm located 60 km from shore at a sea depth of 35 m, the paper found an LCOH of 2.09 $/kg, on par with steam natural gas reforming, compared to the 3.86 $/kg that would arise if the same electricity was transported onshore for electrolysis.

Dinh et al. [36] aimed to establish a geospatial method to determine the LCOH for offshore wind installations in their study. Their study was centered around Ireland, assessing the offshore wind, sea depth, proximity to major ports, and possible injection points of the hydrogen in the national natural gas grid to provide a layer of LCOH values on Irish waters. This paper assumed a 510 MW offshore wind farm with monopile, jacket, and floating foundations according to sea depth, PEM technology, and two installation architectures with offshore or onshore electrolyzers. For onshore electrolyzers, the connection to shore was established via HVAC cables for distances of up to 50 km from the shore and via HVDC cables for distances of 50 to 100 km. The paper undertook an economic assessment to determine the CAPEX and OPEX for the wind farm and hydrogen plant, including the costs for the connection to shore and the natural gas pipeline network. A novel approach in the paper was incorporating five variables—seabed depth, distance to the supporting port, distance to the point of pipeline injection, and two parameters from the wind power Weibull distribution—as input resources in a Cobb–Douglas model to build an LCOH function. The paper then utilized this function to map LCOH forecasts over the seas around Ireland. Three locations, providing LCOH values of 3.4, 3.26, and 3.04 €/kg, were highlighted as promising candidates for such an installation.

In an article from 2023, Akdağ [37] studied an offshore hydrogen production plant to be built in the northwest of Türkiye, at Enez, Edirne. The paper stated the current conjuncture regarding the demand for green hydrogen and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, and proceeded to discuss the economic, transportation, environmental, and seawater/seabed requirements for a feasible green hydrogen investment, which were covered by the proposed plant location. The paper included calculations for wind power, hydrogen production capacity, CAPEX, and OPEX for the plant, LCOH estimates, and “pump prices” for hydrogen to be supplied to fuel cell vehicles in the nearby Istanbul market. LCOH for 2022 was calculated as 6.26 €/kg, which was in line with similar papers in the literature. It was further stated that this LCOH would result in an approximate hydrogen refilling station price of 10.7 €/kg. With the current state of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, this led to a fuel cost of 0.0927 €/km, currently above the level of 0.043 €/km, which could be reasonably assumed for gasoline vehicles. The paper included an outlook for the future, including trends found in the literature for cost decreases due to advances in R&D and economies of scale. For the year 2050, the paper forecasted that LCOH would drop to 1.13 €/kg, and this drop would be reflected in refilling station prices, which would decrease to 2.42 €/kg, and result in fuel costs of 0.021 €/km for future hydrogen vehicles.

A study of recent additions to the literature suggests that a high concentration of papers from Europe is concerned about decarbonization, protection of the environment, and the possibility of supplying sufficient “green” energy to Europe. From the Americas, we have seen papers investigating the economic feasibility of green hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia, and how these can be produced at low cost from regional waters. Papers from Asia aimed to introduce the topic to wider audiences and determine the regional potential for offshore wind and e-fuels, which would reduce dependence on foreign oil.

2.5. Feasibility and Decision-Making Analyses

Some of the papers on the subject focused on how such investments should be planned, calculated, and brought to life. A study by Wu, Liu et al. [38] tackled incomplete barrier identification and biased analysis methods in the development of offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects. The paper established algorithms and matrices, weighing the barriers in the decision-making process and utilizing fuzzy algorithms to analyze the interaction and relative importance of these barriers, and identified the most critical barriers as the complexity of planning and design, unclear technical specifications, steep initial investments, immature business models, and deficiencies in high-matching modeling possibilities.

Another paper by McDonagh, Ahmed, Desmond, and Murphy [39] investigated the profitability of adding H2 production facilities to an offshore wind farm from an investor’s perspective and focused on how much curtailment the offshore wind farm must experience for the hybrid production capacity to be feasible. The study found an LCOH of 3.77 €/kg for the hybrid plant and stated that hydrogen should be salable at a price of 4 €/kg and the wind farm must experience a curtailment of 17% for the hybrid system’s Net Present Value to exceed the offshore wind farm alone. The paper foresaw that a 30% reduction in power-to-gas costs was necessary if the system is expected to convert all electricity to hydrogen to offer equal profitability to the wind farm itself; without this, a hybrid system offering just enough hydrogen production capability to account for curtailment and fluctuations in electricity prices would be more reasonable.

2.6. Technology-Focused Articles

Some of the articles in the literature sought to clarify technical specifications or process choices for the production of hydrogen from offshore wind. A paper by d’Amore-Domenech, Santiago, and Leo [40] aimed to determine the most suitable electrolyzer technology for offshore hydrogen production, comparing direct electrolysis of seawater (DES), alkaline electrolysis (AEL), proton exchange membrane electrolysis (PEM), and solid oxide electrolysis (SOEC). After running five different multicriteria decision-making methods with weighed criteria from social, environmental, and economic factors, PEM came out on top in all methods, with AEL a close second, and DES consistently scoring in last place.

The mentioned paper by Ramakrishnan et al. [11] also investigated direct electrolysis of seawater; the study discussed current electrolysis methods, including the possibility of directly utilizing seawater, as well as various offshore platforms and electrolyzer placements (onshore, offshore, and in-turbine) to support the UK government’s plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. The paper stated that other studies in the field suggested an LCOH of 2 £/kg could be possible and included an in-depth chemical analysis of the challenges brought by the direct electrolysis of seawater. The paper concluded that while there would be the possibility of increasing seawater concentration in electrolyzers in the future, more research was still required regarding the corrosion resistance and efficiency of such electrolyzers, and purification and desalination before electrolysis, particularly incorporating reverse osmosis, offered higher viability and an immediate solution compared to direct electrolysis of seawater.

A previously mentioned paper by Singlicito, Ostergaard, and Chatzivasileiadis [14] investigated the choice between onshore, offshore, and in-turbine electrolysis, as well as three major electrolyzer technologies—PEM, AEL, and SOEC. While the three electrolyzer technologies were determined to be equally competitive, offshore electrolysis stood out as the winner of the first comparison, especially when deployed in a hub-and-wheel architecture (as planned for the North Sea) and performing peak load shaving duties. The paper suggested that employing existing oil and gas infrastructures, utilizing the produced hydrogen to reduce the need to expand electrical grids, benefiting from the co-produced heat and oxygen, and directing most of the produced electricity to hydrogen production provided further advantages.

Jang, Kim, Kim, and Kang [41] highlighted the three main installation types for offshore hydrogen production—distributed hydrogen production in each turbine, collecting the electricity produced at individual turbines in a central electrolyzer platform, and directing the electricity via high-voltage cables to onshore electrolysis—and employed a Monte Carlo simulation to assess the uncertainties in each scenario and how they affect the feasibility and profitability of the investment. First, the paper assumed that a complete installation—together with wind turbines, electrolyzers, offshore platforms, and connection infrastructure—would be built for the explicit purpose of hydrogen production, found LCOH values ranging from 13.81 to 14.56 $/kg, and stated that none of the three alternatives could provide a profitable LCOH for such an investment to make economic sense. The study later proposed the addition of a central electrolyzer (or separate electrolyzers) and hydrogen infrastructure to an existing offshore wind farm to utilize the “zero-cost” electricity in the production of green hydrogen. The study then found LCOH values of 5.28 $/kg for distributed hydrogen production, 5.32 $/kg for centralized electrolysis, and 4.16 $/kg for onshore production, which were close to the DOE target of 5.0 $/kg. The sensitivity analysis found that capacity factors, together with the tax rate, were the main influencing variables in the LCOH calculation, followed by turbine cost, electrolysis systems, and the offshore platform. The Monte Carlo analysis found that, assuming the produced green hydrogen could be sold at 14 $/kg, the distributed production alternative had an 80.3% probability rate of being profitable, followed by centralized production at 71.5% and onshore at 34.35%.

Table 1.

Levelized costs of hydrogen in the studies. Normalized into Euros (Jan 2026).

Table 1.

Levelized costs of hydrogen in the studies. Normalized into Euros (Jan 2026).

| Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (per kg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study by | LCOE (kWh) | Current or Near Past | Calculated for | Forecast | Calculated for |

| Loisel et al. [8] | 4.2–47.1 € | 2030 | |||

| Babarit et al. [9] | 0.08 €/0.04 € | 5.11 € | 2025 | 2.34 € | “longer term” |

| Ramakrishnan et al. [11] | 2024 | 2.31 € | 2050 | ||

| Franco et al. [12] | 50 € (baseline) | 5.35 € | 2021 | 2.17 € | 2030–2050 |

| Calado and Castro [13] | 3.77–11.75 € | 2021 | |||

| Singlicito et al. [14] | 39.4 € | 2.4–4.3 € | 2021 | ||

| Rezaei et al. [15] | 35–90 € | 3.26–5.87 € | 2024 | 2.03–4.36 € | 2040 |

| Ding, Wu and Hsieh [16] | 7.18–8.28 € | 2024 | 6.74–7.76 € | 2035 | |

| Bonacina et al. [19] | <5–7 € | 2021 | 3 € | 2060 | |

| Dinh, Leahy et al. [29] | <5 € | 2030 | |||

| Rogeau, Vieubled et al. [31] | 4.5–7.5 € | 2020 | 1.5–3.0 € | 2050 | |

| Scolaro and Kittner [34] | 4.9 € | 2025 | |||

| Groenemans et al. [35] | 48.44 € | 1.78 € | 2022 | ||

| Dinh, Dinh et al. [36] | 3.04–3.4 € | 2030 | |||

| Akdağ [37] | 6.26 € | 2022 | |||

| McDonagh et al. [39] | 3.77 € | 2020 | |||

| Jang, Kim, Kim and Kang [41] | 11.77–12.42 € | 2022 | |||

A paper by Tran, Ngo, T. Nguyen, and H. Nguyen of Eindhoven University of Technology and Thai Nguyen University of Technology [42] investigated the electrical infrastructure of a stand-alone offshore wind farm. The authors asserted that a stand-alone wind farm and hydrogen production plant should have solid black-start and grid-forming capabilities to initialize and regulate its own operation from a cold start when the wind speed reaches a suitable level (assumed as 5 m/s in the paper) and shut down gracefully when the speed falls below this level. The paper determined the components and network topology of a standalone, AC-based offshore hydrogen production facility, consisting of wind turbines, a backup battery, a PEM electrolyzer, transformers, an active rectifier, a buck converter, and a bidirectional AC/DC converter, which supplies/draws from the battery. The control system assumed droop control, voltage and phase synchronization, and power reference duties. Assuming an installation with 500 MW wind power (25 turbines, 20 MW each) and 400 MW electrolyzer capacity (40 PEM electrolyzers, 10 MW each), the simulations performed in the paper established the electrical parameters for the smooth operation of the above duties and provided graphs of system voltage, frequency, generated power, battery power, and charge from standstill to the start of hydrogen production in a steady regime. The study found that voltage and frequency fluctuations remained at acceptable levels for the operation of such an installation, but power transients occurring at the connection and mode switches of system components needed to be considered.

2.7. Hybrid Approaches and Projects

The literature also included examples of combining other sources of renewable energy production and energy storage to create hybrid energy production projects. A paper by Guo, Gao, Liu, and He [43] aimed to assist investors in deciding the feasibility of offshore wind–photovoltaic–hydrogen storage projects by establishing a decision-making matrix. This matrix was comprised of a criteria system that included economic and situational conditions, a relative-entropy-based model to assess the weights of criteria, and a PROMETHEE method to choose the best investment alternative.

A 2023 paper by Kenez and Dincer [44] combined an offshore wind-powered hydrogen production and liquification plant with residential heating, utilizing the heat removed during hydrogen refrigeration. The paper stated an overall energy efficiency of 70.54% and an overall exergy efficiency of 57.32%, but even with these relatively high efficiencies, the exergy destruction of the hydrogen refrigeration process was noticeable.

A study by Gao, Zhang, and Cheng [45] investigated an offshore wind farm and electrolyzer plant, which transferred both electricity and, during times of low grid demand, green hydrogen to shore. With the aim of achieving maximum efficiency from the plant at various distances (80 km, 100 km, 200 km, and 300 km) to the Chinese coast, the paper compared HVAC and HVDC electricity transmission lines and transportation of hydrogen by pipelines and tankers. Their results implied that HVAC electricity transmission was more efficient in the 80 km distance scenario; at 100, 200, and 300 km, HVDC electricity transmission was more economical. Similarly, a hydrogen pipeline was feasible at 80 and 100 km distances to shore; at 200 and 300 km, transportation by tanker proved more advantageous. Overall, the study found that the proposed system allowed for a smoother adaptation of offshore wind energy to changing grid demands.

2.8. Review Articles on Offshore Hydrogen Production

Review articles focusing on various aspects of offshore hydrogen production are also present in the literature, where the authors review the current literature in terms of technical, economic, or project development topics. The previously mentioned 2021 article by Calado and Castro [13] included a review of offshore hydrogen production articles, including a comparison of the LCOH values provided in these papers for hydrogen produced by AEL and PEM electrolyzers from various green energy sources. For offshore wind, the LCOH with AEL electrolysis was given as 9.17 €/kg, compared to the range of 3.77 to 11.75 €/kg for PEM. The paper contrasted this with the much lower LCOH values obtained from solar PV (2.04 to 5.00 €/kg) and onshore wind (4.33 to 6.61 €/kg) and suggested that it was much more feasible to utilize these energy sources instead to produce green hydrogen.

Ibrahim et al. [46] stated that far offshore wind resources, which would require floating wind turbines, offered a large resource of renewable energy, and offshore wind farms built in these areas were likely to be utilized for hydrogen production in the near future. This paper also included information on the offshore wind farms in operation or under construction at the time of the article and described, with references to many articles in the literature, the main typologies and components for designing and constructing an offshore wind farm to produce green hydrogen, complete with information on desalination, floating platforms, and energy transmission by electric cables or hydrogen pipeline.

A detailed 2023 review by Niblett, Delpisheh, Ramakrishnan, and Mamlouk [47] stated the necessity to increase the production of green energy worldwide and pointed out that electrolysis from far offshore wind resources could be an effective method of green hydrogen. The paper thoroughly discussed electrolysis technologies in detail and listed the challenges of implementing an electrolysis facility in far offshore waters. The review continued with information on other components of the offshore facility, such as pumps, separators, and transformers. The conditions affecting electricity and hydrogen production that would be experienced in offshore operating conditions were listed, and an outlook for future electrolysis designs was provided. The paper concluded with current information on the commercialization of these technologies and a review of current and future projects on the topic.

The previously mentioned critical review paper by Ramakrishnan et al. [11] brought together the current offshore hydrogen production projects of the UK and EU, different platform architectures for the offshore facilities, and detailed information on conventional and direct seawater electrolysis. A list of electrocatalysts utilized for seawater electrolysis, a field receiving increased research and development, was provided, together with possibilities for their future practical implementation offshore. A review by Yuxuan Ye of North China Electric Power University [48] commenced with an introduction to the subject and the current state of wind power production and consumption. The paper discussed the various foundation technologies for different water depths and provided information on the technological implementation of hydrogen production in offshore conditions.

2.9. Environmental Impacts

The main objectives for the utilization of renewable energy sources and production of clean fuels are achieving net reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring sustainable treatment of the environment. Due to the materials used, production methods, and construction work, renewable energy investments themselves are not zero-emission, but they are expected to make up for these emissions and environmental impacts many times over during their service life. One of the leading turbine manufacturers, Ørsted, stated [49] that dividing the total emissions related to a wind turbine during its lifetime by the amount of electricity it produces resulted in 6 g of carbon dioxide emitted for each kilowatt-hour of energy. The report compared this to generating electricity from coal, which resulted in 900 g of carbon dioxide emitted for each kilowatt-hour of energy, resulting in a 99% reduction in emissions by choosing wind power. The company was intent on further reducing the carbon footprint of its turbines, stating that they were on track to reduce the emissions intensity of their products by 98% by 2025 compared to figures from 2006 and were working on eliminating the last 6 g of carbon dioxide emissions as well. The carbon footprint of hydrogen also depends heavily on the production method. A research paper by Davies and Hastings [50] compared the GHG emissions of blue hydrogen produced from offshore methane, green hydrogen from offshore wind energy, and hydrogen produced by electrolysis using the UK National Grid and the current “business-as-usual” case of combusting methane for energy. The authors measured carbon emissions by the tons of CO2 emitted to produce 0.5 tons of H2 per year for a duration of 25 years. In their analysis, the carbon emissions of blue hydrogen production varied by the efficiency of carbon capture, ranging from 200 to 262 tons per 0.5 ton H2/year. Green hydrogen produced from 100% renewable electricity reduced this to 20 tons. The carbon footprint of hydrogen produced with electricity from the National Grid depended on the success of the UK NetZero strategy and varied from 103 to 168 tons according to the constituents of the energy mix. In comparison, combustion of the same amount of offshore methane resulted in 250 tons of carbon dioxide emissions. The authors stated that production of blue hydrogen at scale is not at all a “low carbon technology” and should not be taken as a decarbonization route. A 2022 study by de Kleijne, de Connink et al. [51] set the greenhouse gas footprint of grey hydrogen at 12 kg CO2-equivalent per kg H2, blue hydrogen with 55% capture at 6.5 kg CO2/kg H2, and blue hydrogen with 93% capture at kg CO2/kg H2. In contrast, electrolysis using the EU electricity mix for 2020 resulted in 17 kg CO2/kg H2, higher than grey hydrogen. With a more environmentally friendly electricity mix in 2030, the figure dropped to 5.5 CO2/kg H2. Utilizing electricity from offshore wind reduced the emissions to around 1 CO2/kg H2. As a result, the authors stated that the GHG footprint of green hydrogen could vary greatly with electricity choice. A lifecycle assessment by Balaji and You [52] set in the USA found attributional lifecycle GHG emissions from 0.6 to 3.0 CO2/kg H2. This was much better than grey hydrogen, estimated at 10–11 CO2/kg H2 in the USA. The US Department of Energy limited the GHG emissions of “clean hydrogen” by definition to 4 CO2/kg H2, sourcing the electricity from offshore wind, which allowed production to stay within this limit. The analysis also predicted delivered costs of H2 from 2.50 to 7.00 $/kg and found delivery of hydrogen by pipelines to be more environmentally and economically sound than liquefied shipping. A 2023 study by Zhou and Baldino [53] also noted that carbon capture during blue hydrogen production only captured around 55% of the CO2 and called for stringent ISO standards to define GHG emissions for blue hydrogen so as not to overestimate the environmental benefits.

Greenhouse gas emissions are not the only environmental impact of offshore hydrogen production. A 2025 report [54] on the local hydrographic footprint of offshore hydrogen production described how the release of waste heat and brine from the operation impacted the marine environment for hundreds of meters around the site. The models run by the authors implied that waste heat, in particular, could cause surface heating, which exceeds the long-term natural variance and even the expected climate change outcomes. Future offshore hydrogen production with capacities up to a 2 GW range could increase the local sea surface temperature by 0.2 °C within 500–1000 m of the site, with even higher capacities intensifying the effects. The authors suggested that spreading the disposal of waste heat and brine, perhaps by using decentralized electrolyzers at each turbine, could mitigate the effects.

2.10. Technological Readiness and Bottlenecks

This subsection will present how ready the technologies detailed above are for deployment in offshore environments, describe the steps that must be taken to improve their readiness and commercial feasibility, and identify the bottlenecks that currently exist and are likely to arise when the technologies are installed and in operation. The first technology that must be inspected is offshore wind energy itself—we have more than a century of experience in generating electricity with wind turbines on land, and in the last 10 years, there have been great strides in offshore installations, with blade wheel diameters exceeding 300 m and rated power reaching 26 MW. The US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) stated in their Energy Clusters Offshore: A Technology Feasibility Review from December 2024 [55] that fixed-bottom offshore wind turbines offered energy costs ranging from 0.06 to 0.11 $/kWh and placed their Technology Readiness Level (TRL) at high (levels 7 and above are considered “high”). For floating offshore wind turbines, energy costs were stated as 0.07 to 0.17 $/kWh and their TRL was described as “medium-high” (equal to 6 to 7). Fixed-bottom offshore wind turbines are a proven technology, and with commercial use at numerous new installations, floating turbines could soon reach “high” TRL as well. The next link in the chain is generating hydrogen from this offshore wind energy. The same NREL report mentioned that “electrolysis is the only clean technology for producing hydrogen with a high TRL”, placing the cost of hydrogen produced with wind power and PEM electrolyzers at 2 $/kg at the low end and 11 $/kg at the high end. The report continued with the figures for hydrogen storage, as the produced hydrogen would need to be stored on the platform. Here, both gaseous storage in pressure vessels and liquified storage were listed with a “high” TRL, with costs ranging between 13 and 17 $/kWh for gaseous storage and 10 and 30 $/kWh for liquid storage. The report suggested that the higher cost and boil-off characteristics of liquified storage meant it might not be a good fit for offshore platforms and commented “liquid material-based storage has promising performance and costs comparable to gaseous storage, hence, could be studied for offshore energy clusters”. In their paper dated November 2024, Marques, Vieria et al. [56] stated that alkaline electrolyzers still offered a higher TRL than PEM electrolyzers. Bos, Kersten, and Brilman [57] assigned TRLs of 9 to alkaline and 5–7 to PEM electrolysis, with solid oxide technologies receiving a TRL of 3–5. The Maritime Knowledge Centre, TNO, and TU Delft’s assessment [58] of alternative fuels for seagoing vessels using Heavy Fuel Oil listed Power-to-Hydrogen through electrolysis using renewable electricity at TRL 9 for 2019 and expected TRL 10 for 2030. In general, offshore wind energy is commercially viable at this point, and while alkaline electrolyzers are the more mature option, PEM electrolyzers appear ready to be employed in the initial installations that will produce hydrogen offshore.

The biggest bottleneck, perhaps for all offshore energy and e-fuel production, could be the high installation, maintenance and repair costs, and qualified workforce demand for deep-water platforms. Even though fixed-bottom foundations are tested-and-true solutions, it is still necessary to tow large equipment to installation locations, employ crane ships for installation, and transport specialist crew during installation and frequently during maintenance and repair. For deeper waters and floating platforms, there are still uncertainties in choosing the right support structure and spar configuration, and many other installations need to be completed before economies of scale and experience in production and installation bring costs down. All equipment to be employed on offshore platforms needs to withstand severe saltwater atmospheres and frequent oscillations, requiring even the paint to be specified for marine conditions. The choice of electrolyzers is also affected by marine operation, which will also be discussed in its separate subsection—with high fluctuations in energy production and frequent start–stop requirements, AEL electrolyzers are a poor fit for these platforms, and their high maintenance requirements utilizing corrosive liquids are also likely to cause a plateau. This leads to another big bottleneck: PEM electrolyzers, which are a better fit for the intermittent levels of renewable energy, are currently very expensive, with their costs accounting for up to 70% of the total cost of installations in the referenced examples. The industry is expecting heavy discounts in the future with more R&D in the area, and this needs to be realized before PEM electrolyzers can be deployed at full scale. Finally, hydrogen storage on the platforms can be accomplished with either pressurized vessels or liquefaction and cryogenic storage; here, the high costs of liquid storage will likely be prohibitive, while compressed gas storage will either occupy large tanks with low pressures, where space is already at a premium in offshore platforms, or require compression to high pressures, which consumes more energy and creates occupational hazards of its own.

Government and industry alliances could speed up the evolution of offshore wind electricity and e-fuel production by adopting supportive policies. Among them, the foremost is establishing clear administrative frameworks and industry standards for offshore operation and power generation. Initiatives by the European Union, Great Britain, the USA, and China to transform their seas into “energy corridors” will likely have the greatest bolstering effect in the expansion into deeper waters. Even though the energy generation potential is enormous, it is expected that the field will require subsidies and incentives to appeal to contractors. Already, the European Green Deal is pushing corporations toward using green technologies to avoid carbon taxes, and some of the scenarios in the literature can only become financially feasible if carbon taxes preclude other sources of energy or fuel. Finally, international energy trade agreements will play a large role in establishing regional electricity grids and hydrogen pipeline corridors, leading to some countries becoming “green energy exporters” and others becoming “importers”. These agreements can ensure that national and industrial green transformation objectives are realized, and their progress will indicate if the transition is continuing as intended.

2.11. Electrolysis in Offshore Conditions

Electrolyzer technologies are developed and tested with operation on land in mind, in stable and protected environments. Operating electrolyzers in offshore conditions puts much higher demands on load cycles, minimum operating loads, support stability, corrosivity of the environment, and difficulties in installation and maintenance. Some of these demands can be known beforehand, such as the intermittency of renewable energy resources. Most authors in the reviewed articles chose PEM electrolyzers for their analyses because these electrolyzers can operate at levels as low as 5% of their capacities. However, alkaline electrolyzers are not to be dismissed completely. A 2024 study aimed to assess the cost of offshore-produced hydrogen [59] and ran their model with AEL and PEMEL electrolyzers, with a 42.6% capacity factor for each. The resulting hydrogen production amounts were 35,393,000 kg for AEL and 33,840,000 kg for PEMEL electrolyzers, showing that AEL electrolyzers produced around 5% more hydrogen. The paper itself acknowledged the suitability of PEMEL electrolyzers with intermittent energy sources, but in their study with 98 electrolyzer stacks, AELs were sufficiently adapted to generation with fluctuating supply. The study leaned toward AEL electrolyzers in the end owing to their higher hydrogen production at lower costs. While AEL and PEMEL electrolyzers are sufficiently studied, another analysis [60] was performed with the intention of determining the dynamic response of AEM electrolyzers, with abrupt changes in supply currents. The voltage drops in the electrolyzers, total hydrogen production, and the power consumption of the electrolyzers were noted. The authors noted that AEM electrolyzers reacted quickly to changes in the power sources, but a few minutes of inertia were noticeable in the system. The AEM electrolyzers studied had a nominal workload efficiency of 0.738, which dropped to 0.65 in the study. The analysis achieved the longest operating times at the nominal operation point when the electrolyzer power was equal to 0.21 times the wind farm’s rated power.

The previously mentioned review by Niblett et al. [47] detailed the effects of the offshore environment on electrolyzers and hydrogen production. First, fluctuating power might cause start-and-stop cycling in the electrolyzers, potentially decreasing durability and increasing maintenance periods. Splitting the power by increasing the number of stacks could decrease the amount of electricity wasted due to the minimum load criteria. A power generated curve, calculated for the wind farm’s location, may be employed in modeling to predict total production and efficiency. The study noted that while the better start-up times and load response ramps of PEM electrolyzers compared to AEL are well-known, AWE could also adapt to dynamic changes in load and integrate with renewable electricity production.

On offshore platforms, electrolyzers’ exact vertical orientation may not be guaranteed. In such situations, oxygen and hydrogen bubble dynamics and liquid–gas separators could be affected by swaying motion: cross-over of bubbles and cross-channel convection might be introduced [61]. The authors also pointed out that if fuel cells were integrated into the system to also produce electricity when required, storing the oxygen side-product may be worthwhile to increase the efficiency of production.

In another novel article [62] studying the utilization of electrolyzers, fuel cells, and desalination together, the authors studied a hypothetical renewable hydrogen energy system on an island close to Tasmania. The waste heat from PEM electrolyzers and fuel cells, which could be considered “low grade energy” due to its low temperature (compared to SOEC electrolyzers, for example), was nevertheless isolated and utilized to power Direct Contact Membrane Desalination. In their analysis of the system, 65% of the total available waste heat was utilized to provide energy for desalination that met over 30% of the electrolyzer’s water demand. The authors note that the system can be expanded to cover almost all of the desalination energy, and this could be adapted to offshore platforms to reduce the energy drain from desalination systems.

Another previously mentioned paper [11] noted that though space is very limited on offshore platforms, the high power density and compact dimensions of electrolyzer systems meant they were not likely to become an issue. However, the study warned that the risk of fires, leaks, and other accidents means emergency plans and precautions need to be established, and these could be more expensive than land-based facilities. To protect the equipment from the corrosive, salty, and humid atmosphere, special coatings and cathodic protection would be needed. Some of the water treatment and electrolyzer systems might require protection in enclosures. According to the electrolyzer type, some chemicals may need to be brought to the platform, while some may need to be taken away, which would require transport infrastructure. The authors noted that access to offshore equipment could be challenging, especially when hindered by harsh ocean weather, and maintenance could be very costly because of the need to send specialists on long voyages for repairs. Reliable processing systems and effective maintenance strategies must be in place to minimize downtime, with solid infrastructure for electrolyzers and their heat management, power conversion, gas purification, and compression.

Some academics also investigated direct seawater electrolysis in their papers [47]. Directly using seawater allowed the removal of water desalination and deionization processes and their respective costs, but these were offset by the high cost, lower efficiency, and higher maintenance of direct seawater electrolysis. In acidic environments, the chlorine evolution reaction (CER) might compete with the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), causing chlorite precipitation and pH gradients in the device. In addition, as seawater does not have the same composition of salts and cations around the world, there could be variances in ionic conductivity and precipitation rates in different operations around the world. Indissoluble materials might precipitate on electrode surfaces, degrading performance. The authors suggested increasing flow rates to prevent the build-up of solids and decrease the pH gradient. They also noted that seawater electrolysis without desalination might be possible via specialized catalysts and proper handling of fluids in a membrane-less device; however, pH gradients need to be prevented as they could still exist without a buffer. The paper also noted that using direct seawater as the electrolyte could allow for near-neutral pH operation, which would allow the use of lower-cost construction materials, but the low efficiency, current density, side reactions, and corrosion of this method limited its appeal.

2.12. Levelized Costs, Assumptions, and Efficiencies

The levelized costs of hydrogen (LCOHs) provided in covered articles are presented below, together with levelized costs of electricity (LCOEs) powering electrolysis and the assumptions made and equipment efficiencies whenever stated by the authors.

The table for the levelized costs of hydrogen includes the levelized costs of electricity whenever included in the original text. There are also variances in electrolyzer and equipment efficiencies and assumptions made to simplify calculations, which will be discussed below.

Loisel et al. provided a relatively early paper in the literature, and the text stated that as of 2015, “the hydrogen cost varies from 5 €/kg to 30 €/kg” depending on equipment size. The authors quoted that with an electricity cost of 40 €/mWh, a large-scale hydrogen plant could reduce the cost to 3 €/kg hydrogen [CEA. French Atomic Energy Commission]. Their own review assumed a PEM electrolyzer efficiency of 65% and a fuel cell efficiency of 55%. The total installed wind power capacity was 1000 MW, and they stated that reserve electricity prices were regulated at fixed rates of 18.12 €/MW by hour for the capacity and 10.43 € by MWh for energy delivered. Their scenario for 2030 assumed that hydrogen-to-power would be sold at a price of 165 €/mWh and the carbon tax would be 35 €/ton CO2. This early paper with relatively low equipment efficiency and multiple outputs for hydrogen found higher levelized costs for hydrogen ranging from 4.2 to 47.1 €/kg.

Babarit et al. assumed low electricity costs at far offshore locations at 0.08 €/kWh (with electrolyzer prices of 900 €/kW and energy consumption of 55 kWh/kg) declining to half this amount 0.04 €/kWh (with electrolyzer prices of 600 €/kWh and energy consumption of 50 kWh/kg) in the “longer term”. The authors also assumed high-capacity factors for the wind conversion, at 80% for 2025 and 90% for the longer term, and therefore reached relatively low hydrogen costs at the electrolyzer at 5.11 €/kg for today and 2.34 €/kg for the longer term, which increased when the hydrogen was transported back to shore, to 8.7/4.4 €/kg for liquified transport and 8.8/4.7 €/kg for compressed gas transport.

Ramakrishnan et al. studied direct electrolysis of seawater, stating that PTFE-based membrane electrolyzers achieved 67% electrical efficiency. The authors compared this to PEM and alkaline electrolyzers, which operated at 95–87% electrical efficiency, and mentioned the need and possibility to further refine direct seawater electrolyzers.

Franco et al. assumed an offshore wind farm with a nominal capacity of 100 MW with a more modest capacity factor of 0.5, where hydrogen was produced at PEM electrolyzers with 60% system efficiency. The lifetime of the project was 25 years, whereby the € inflation rate was 1.7% and the discount rate was 7%. The authors performed a sensitivity analysis with varying electricity prices, electrolyzer costs, and efficiencies, and stated that LCOE was the most dominant factor in hydrogen production cost. With baseline calculations and pipeline delivery, the authors calculated an LCOH of 5.35 €/kg and a future cost, with successful EU support, of 2.17 €/kg.

Singlicito et al. stated that the cost of offshore wind electricity in Europe at the time of writing was 45–79 €/MWh and compared this with the lowest LCOE they calculated at 39.4 €/MWh in the scenario with offshore electrolysis. The authors stated that AEL electrolyzers, with 66% estimated efficiency, provided the lowest costs, with PEMEL (62% eff.) and SOEL (79% eff.) trailing behind. In their system, with 100 MW total wind energy capacity, they found the lowest LCOH of 4.2 € with offshore electrolyzers at a 100 km distance to shore and the highest LCOH of 4.3 € with in-turbine electrolyzers at approximately 380 km to shore.

Rezaei et al. utilized PEM electrolyzers in their article, with dynamic, load-based efficiency ranging from 55 to 80%. They also assumed a project lifetime of 25 years. Their LCOE findings ranged from 53 to 90 €/kWh in 2024 to 35 to 70 €/kWh in 2040, resulting in a minimum LCOH of 2.03 € in 2040 and a maximum LCOH of 5.87 € in 2024.

Ding, Fu, and Hsieh employed PEM electrolyzers with a rated efficiency of 73.6%. The authors employed a dynamic efficiency model by load so as not to overestimate hydrogen production. The efficiency of the electrolyzers also increased by 0.25% per year. Electricity losses during transmission were set to 3% per 1000 km. Annual degradation of wind turbine efficiency was 1.6% per year. With a 100 MW system and capacity factors from 0.4 to 0.6, the study found LCOH ranging from 7.18–8.28 € in 2024 to 6.74–7.76 € in 2035 but did not disclose LCOE values.

Bonacina, Gaskare, and Valenci proposed a 150 MW wind farm with electrolyzer-power-to-wind-power rates from 0.8 to 0.9 in their analysis. They assumed a plant life of 25 years, electrolyzer efficiency of 64%, and an overall plant efficiency of 55.2%. The authors specifically stated that they would provide LCOH values, ranging from 5 to 7 € in 2021 to 3 € in 2060, instead of LCOE values.

Dinh, Leahy et al. studied a hypothetical wind farm with a capacity of 101.3 MW, a power coefficient of 0.3 to 0.5, and an availability of 95%. Electrolyzer efficiency was set at 93% and stack life at 12.5 years. Electrolyzer power consumption was set as 58 kWh/kg in 2017 and 50 kWh/kg in 2030. Again, the authors did not state LCOE values but reported that the plant would be profitable in 2030 with a hydrogen price of 5 €/kg.

Rogeau et al. investigated offshore wind farms at differing distances to shore, with the 1 GW-capacity wind farm’s availability kept at 94% and a failure rate of 0.08 per year. HVDC substation efficiency was 99%, power converters were 99.5%, and electrolyzer efficiencies were 62% for 2020, 65% for 2030, and 70.5% for 2050. The desalinator was set to operate at 99.9% efficiency. The authors found LCOH values of 4.5–7.5 € for 2020 and 1.5 to 3.0 € for 2030.

Scolaro and Kittner analyzed a potential 150 MW offshore wind farm, with a levelized cost of 75 €/MWh. They found that 20 MW PEM electrolyzers produced hydrogen with 46.6 kWh/kg H2 electricity consumption, with a system life of 20 years and a 50,000 h stack life for 2017. For the 2025 assessment, power consumption was reduced by 10%. The cost of electricity from the wind farm was assumed to be 75 €/MWh. With a 131 MW electrolyzer, equaling 87% of the capacity of the wind farm, the authors calculated an LCOH of 4.9 €/kg.