Abstract

Ammonia (NH3) is a promising carbon-free energy carrier for low-carbon power generation. However, in turbulent ammonia–methane (NH3-CH4) premixed swirling flames, operating at lean conditions to limit NOX, emissions can trigger strong thermoacoustic oscillations. This study investigates thermoacoustic oscillatory instability in an NH3-CH4 swirl-stabilized combustor using the chemiluminescence of CH*, OH*, and NH* over a wide range of ammonia fuel fraction (XNH3). Combined spectral measurements and 2D chemiluminescence imaging are employed to obtain the global emission characteristics and spatial distributions of OH* and NH* in the UV band and CH* in the visible band. A custom-designed intensified CMOS (ICMOS) camera based on a high-gain UV–visible image intensifier with direct coupling is developed to enable sensitive OH* and NH* imaging (gain > 104). Frequency analysis of continuous CH* imaging, together with morphology-based principal component analysis and k-means clustering of 46 image features, shows that oscillatory combustion occurs for XNH3 < 0.40, whereas XNH3 ≥ 0.40 leads to multimode, stable combustion. As XNH3 increases, OH* and NH* fields progressively decouple from CH*, becoming more elongated and shifting downstream. These results demonstrate that UV radical chemiluminescence provides indispensable information on NH3 reaction zones and should be combined with CH* diagnostics for reliable thermoacoustic analysis and control in practical NH3-fueled combustion systems.

1. Introduction

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) Global Energy Review 2025 [1] and World Energy Outlook 2023 [2], despite the rapid expansion of renewable energy, fossil fuels still accounted for approximately 80% of global primary energy supply in 2024, which is projected to decrease to approximately 73% by 2030. This situation, in turn, has made the accelerated deployment of renewable energy and low-carbon energy carriers such as hydrogen (H2) and ammonia (NH3), aimed at reducing carbon emissions, a key priority of national energy and climate policies. Because it can be synthesized by renewable electricity, has high energy density, and exhibits high safety in storage and transportation [3], NH3 has become an important candidate fuel for achieving zero-carbon combustion [4]. However, NH3 exhibits relatively low flammability [5], characterized by a low combustion velocity and a narrow flammability range. To improve the combustion performance of NH3, it is commonly mixed with conventional hydrocarbon fuels [6,7,8] or with H2 [9,10] to mitigate issues such as low combustion efficiency and poor flame stability. For example, novel engines employing NH3-H2 mixed-fuel show promising application prospects in power generation [11], shipping [12], and aerospace propulsion [13]. At present, the combustion characteristics of NH3-CH4 mixtures have been extensively investigated by numerical simulations [5,14,15], whereas experimental datasets obtained under realistic operating conditions remain relatively scarce. In particular, in turbulent engine combustion, NH3 enrichment of lean premixed flames can induce thermoacoustic instability and pronounced flame oscillations [16,17], which may lead to severe engine damage. A more comprehensive understanding of the combustion mechanisms underlying this phenomenon therefore requires additional experimental evidence.

In an NH3-CH4 combustion, the blending ratio directly influences flame stability, ignition characteristics, combustion efficiency, flame propagation, and NOx formation [9,18]. The optical diagnostics of flames are important tools for combustion mechanism studies due to their non-intrusive and a wide field of view [19,20,21]. During combustion, various electronically excited radicals, such as OH*, CH*, NH*, CO2*, and NH2*, are produced [22]. These species act as intermediates in chain reactions and are typically concentrated in regions of intense reaction, with spontaneous radiation at characteristic wavelengths. Measuring flame-emission characteristics under well-controlled laboratory conditions over a range of different blending ratios provides valuable data for elucidating the combustion mechanisms of NH3-CH4 mixtures, validating numerical simulations, enabling precise control of the combustion process, and supporting pollutant-mitigation strategies.

The main methods for characterizing the spontaneous chemiluminescence of flame radicals include spectral measurement [23,24,25] and chemiluminescence imaging [26,27]. Spectral measurement uses a spectrometer to measure the broadband emission spectrum of the flame (e.g., 200–600 nm). The spectral peak positions provide information on the types of radicals present during combustion, while the corresponding intensities and intensity ratios can be used to infer key parameters such as equivalence ratio and heat-release rate. In 2021, Zhu et al. [24] performed axial spectroscopic measurements of an NH3-CH4-air flame, targeting—NO*, OH*, NH*, CN*, CH*, and CO2*—in the 200–457 nm wavelength range. They analyzed the relationships between relative emission intensities and operating parameters such as equivalence ratio and NH3 fraction. This work represented the first detailed report of the radical chemiluminescence spectrum of an NH3-CH4 flame. However, a major limitation of spectral measurement is that the spectrum cannot provide spatial distribution information of radicals, a deficiency that chemiluminescence imaging can overcome. Chemiluminescence imaging techniques use narrowband optical filters and intensified cameras to obtain emissions from single radicals in specific wavelength bands, thereby resolving their spatial distribution. Pugh et al. applied chemiluminescence imaging to an NH3-H2 flame, selecting OH*, NH2*, and NH* as target species [28]. They used a Phantom v1212 high-speed CMOS camera coupled with a Specialised Imaging SIL40HG50 high-speed image intensifier, achieving an image resolution of 345 × 460 pixels, a frame rate of 4000 Hz, and an intensifier gate time of 10 µs. Mashruk et al. [29] conducted multi-radical chemiluminescence imaging diagnostics on a CH4-NH3-H2 premixed swirling flame, using narrowband filters to obtain 2D chemiluminescence fields of OH*, CH*, NH*, and NH2*, and subsequently deriving radial intensity profiles by time-averaging and Abel inversion. The results showed that, as the NH3 ratio increased, the main reaction zone of the flame extended significantly downstream and the flame became longer and thicker. These findings indicate that changes in fuel composition lead to a redistribution of radicals and a restructuring of the reaction-zone topology, which is of great importance for understanding the combustion and emission characteristics of NH3-based fuels. The two diagnostic approaches are complementary in the spectral and spatial domains and together can establish a comprehensive database of radical chemiluminescence characteristics. However, the existing literature still contains relatively few studies that employ multi-band optical diagnostics to capture radical chemiluminescence during thermoacoustic oscillations in turbulent swirling NH3-CH4-air flames.

In turbulent combustion, pressure oscillations arise from the interaction between unsteady heat release and the turbulent flow field [30,31,32]. These oscillations propagate within the combustor as acoustic waves, modulate the flame heat-release process, and thereby increase the unsteadiness of heat release, forming a feedback loop. When the pressure oscillations and heat release rate fluctuations satisfy certain phase and amplitude conditions, the pressure oscillations are amplified. The dominant oscillation frequencies are often on the order of 102 Hz, and resolving the flame dynamics within an oscillation cycle typically requires integration times on the order of hundreds of microseconds, which in turn necessitates the use of an image intensifier to amplify the optical signal. An image intensifier mainly consists of a photocathode, a microchannel plate, and a phosphor screen [33]. The photocathode converts incident photons into electrons via the photoelectric effect. These electrons are multiplied in the microchannel plate and then converted back into photons at the phosphor screen. For example, Gerke et al. [34], Paschal et al. [35], and Pugh et al. [28] coupled image intensifiers with high-speed cameras to perform high-speed chemiluminescence imaging. In NH3 combustion, the chemiluminescence intensity of NH* is weaker than that of radicals such as OH* and CH* [24], and the use of narrowband filter centered at 337 nm further attenuates the radiation reaching the camera. Therefore, the high-speed imaging of NH* requires image intensifiers with higher gain. The coupling configuration between the image intensifier and the high-speed camera is one of the key factors governing the effective system gain. Because high-speed cameras are expensive and susceptible to damage, most existing intensified imaging systems use relay-lens optical coupling, which can result in coupling-efficiency losses of up to 70% in the UV band. By contrast, direct coupling provides higher coupling efficiencies, achieving values exceeding 75%. Directly coupled intensified CMOS with high-gain UV–visible image intensifiers offer a promising route to overcome this limitation and enable high-sensitivity OH* and NH* imaging in thermoacoustically unstable NH3-CH4 flames.

Motivated by these considerations, the present work investigates thermoacoustic oscillatory instability in a premixed NH3-CH4 swirl-stabilized combustor using the chemiluminescence of CH*, OH*, and NH* over a range of ammonia fuel fraction XNH3. Combined spectral measurements and 2D chemiluminescence imaging are employed to characterize both the global emission spectra and the spatial distributions of the radicals. A custom-designed ICMOS camera based on a high-gain UV–visible image intensifier with direct coupling is developed to achieve high-sensitivity OH* and NH* imaging. Frequency analysis of continuous CH* imaging, together with morphology-based principal component analysis and k-means clustering of 46 image features, is used to classify flame morphologies and to distinguish between limit-cycle oscillation (LCO), quasi-periodic oscillation (QPO), and stable combustion (SC) regimes as XNH3 varies. The results demonstrate that oscillatory combustion occurs for XNH3 < 0.40, whereas XNH3 ≥ 0.40 leads to multimode, low-amplitude or stable combustion, and that OH* and NH* fields progressively decouple from CH* at high XNH3, becoming more elongated and shifted downstream. These findings highlight the need to incorporate UV radical chemiluminescence, together with CH* imaging, into thermoacoustic diagnostics and control strategies for practical NH3-containing swirling flames.

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Burner and Combustion Conditions

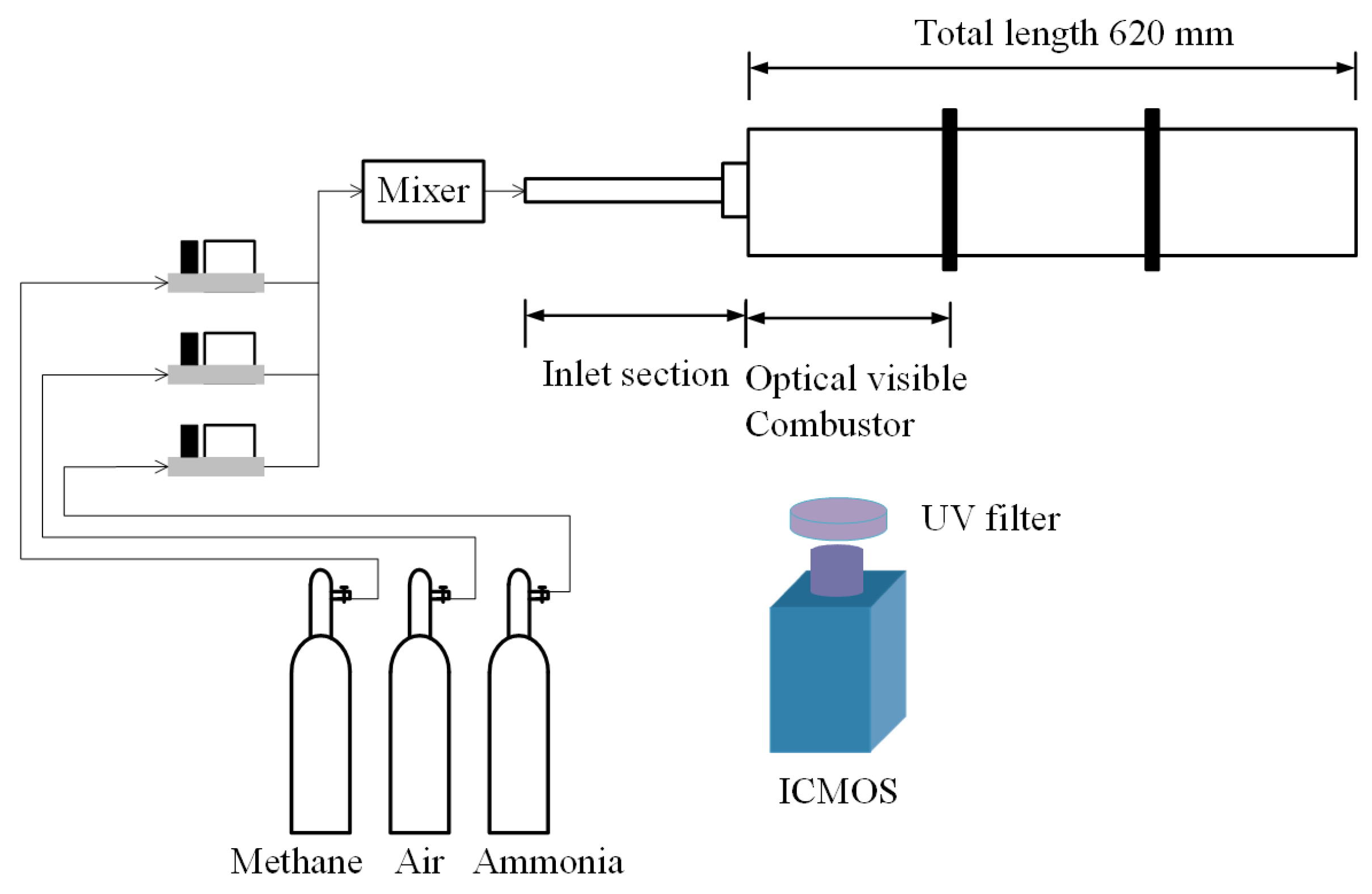

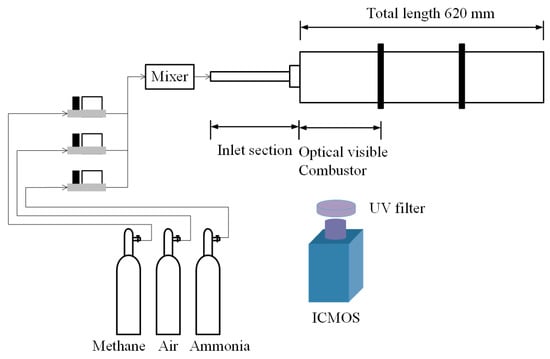

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the NH3-CH4 swirl burner. The burner consists of an inlet assembly, a combustion chamber observation section, and a combustion chamber extension section. Methane (99.999%) and ammonia (99.999%) are supplied from 40 L liquid cylinders. Air is compressed to 1.2 MPa by an air-compressor to ensure a stable supply of all the gases. Alicat mass flow controllers with an accuracy of ±1% are used to control the flow rates. A gas mixing tank is installed upstream of the inlet section, where the gases are thoroughly premixed before entering the burner. The axial swirler consists of a central hub and six helical vanes with vane thickness of 1 mm. The inner and outer diameters of the swirler are 4 mm and 11 mm, respectively, and the vane angle is 60°, corresponding to a geometric swirl number of 1.27. The combustor front-section inner diameter is 100 mm with a length of 200 mm, and the total chamber length is 620 mm, as shown in Figure 1. The outlet is treated as an open boundary. The initial condition is ambient temperature and atmospheric pressure. Based on the operating conditions in Table 1, the Reynolds number ranges from 1.48 × 104 to 1.56 × 104. Using a simplified 1D open-closed duct model, the fundamental longitudinal acoustic mode is estimated to be approximately 138 Hz under ambient conditions. Detailed geometric parameters of the combustor are presented in our previous work [17] and are not repeated here for brevity.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of ammonia–methane premixed swirl-stabilized combustor.

Table 1.

Different operating conditions for swirling combustion in this study.

The combustion chamber is equipped with quartz windows with a transmittance greater than 90% in the 300–700 nm wavelength range. During ignition, because of the poor combustibility of ammonia, a stoichiometric CH4-air mixture was first ignited to ensure stable flame establishment. After the flame had stabilized, the NH3 was gradually increased, and at each steady state the flame emission spectrum and 2D radical chemiluminescence images were acquired. As summarized in Table 1, measurements were performed at different XNH3, defined as the volume fraction of NH3 in the total fuel. The equivalence ratio was maintained at approximately 0.80. Based on preliminary tests, self-excited thermoacoustic oscillations were more readily observed under this lean condition.

2.2. Optical Diagnostic Methods

Spectral measurements were conducted using an Avantes spectrometer (Avantes BV, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands) (200–1000 nm) at the location of peak heat release (68 mm downstream of the nozzle exit). The spectra were background-subtracted. Owing to the swirling flame and its periodic dynamics, the measured spectra correspond to radiation integrated over the acquisition window; the integration time was 80 ms. Two-dimensional chemiluminescence imaging targeted CH*, OH*, and NH*. CH* images were acquired using an EyeiTS intensified high-speed module (gain > 103) with a 430 nm bandpass filter (FWHM 10 nm) at 5400 fps and an exposure time of 185 µs. OH* and NH* images were acquired using a self-designed ICMOS system consisting of a UV intensifier (North Night Vision; 200–800 nm, max gain 104) directly coupled to a CMOS sensor (Daheng VEN301, 2048 × 1536, from China Daheng Group, Inc., Beijing Image Vision Technology Branch, Beijing, China) and an Azure UV lens (200–1000 nm). The system was externally triggered to control the intensifier gate, with a 421 µs exposure time. Bandpass filters were centered at 310 nm (FWHM 10 nm) for OH* and 337 nm (FWHM 8 nm) for NH*. During the experiments, the ICMOS gain was empirically adjusted to avoid pixel saturation and to ensure that the image intensifier operated within its linear gain regime.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Flame Radiation Spectra at Different XNH3

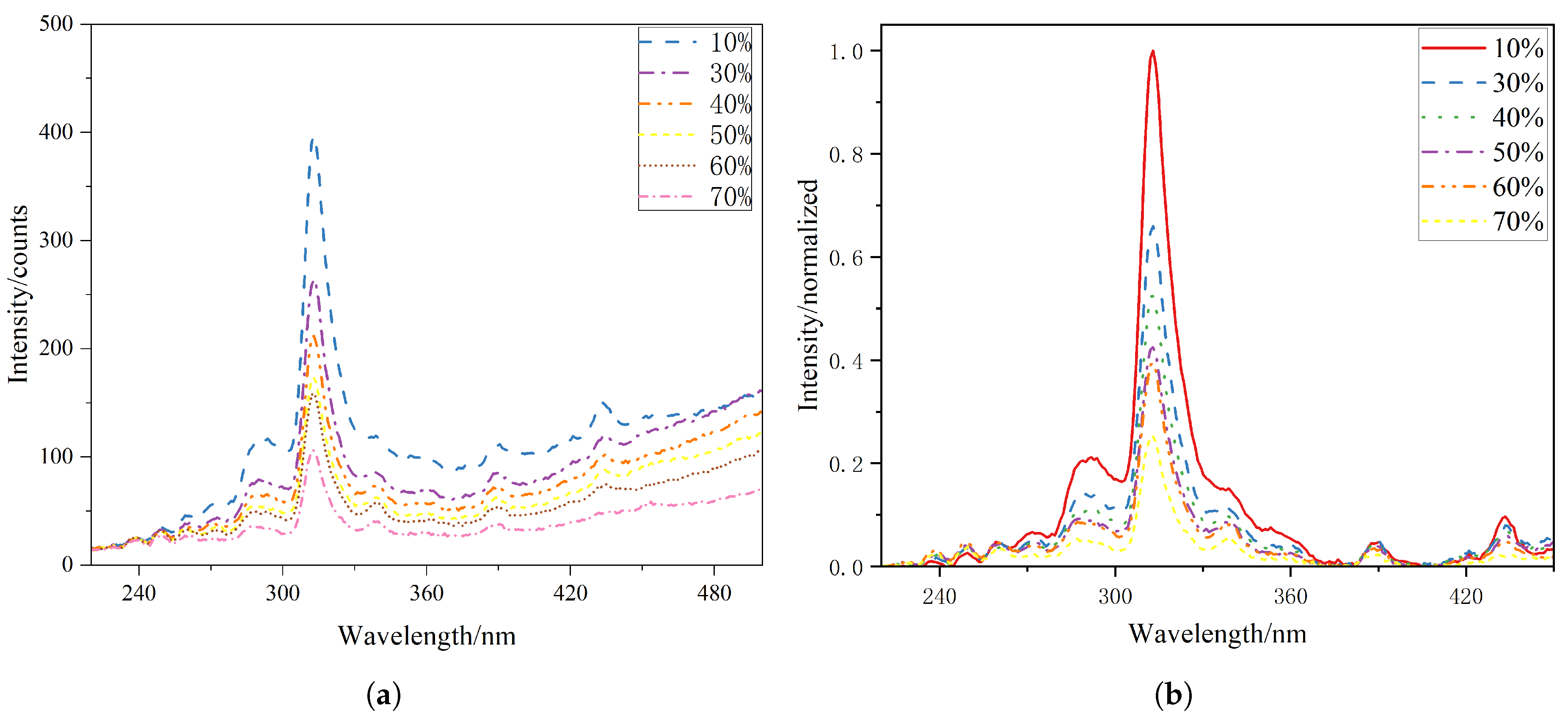

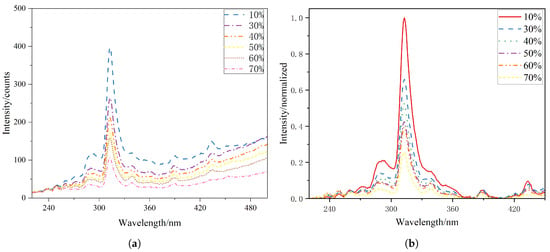

The flame radiation spectra obtained at different XNH3 were analyzed from several perspectives, including the characteristic spectral features of the flame and the relationships between XNH3 and radical intensity ratios. Figure 2a shows the raw radiation spectra measured under the conditions described in Section 2.1, focusing on the wavelength range from 220 to 500 nm. Because emitting species such as CO2*, and combustion products including H2O and CO2 exhibit broadband emission, baseline points were selected to fit the underlying broadband emission curve. This fitted baseline was then subtracted from the raw spectra to improve the accuracy of the line-emission data. The corrected spectra were then normalized using the peak intensity of all the spectra. The resulting normalized spectral distributions are shown in Figure 2b. The spectra at different ammonia blending ratios share several common features: radiation peaks are observed near 250, 310, 337, 390, and 430 nm, corresponding to NO*, OH*, NH*, CH(B–X), and CH(A–X), respectively. These spectral features confirm the presence of NO*, OH*, NH*, and CH* chemiluminescence in flames with NH3 addition. As the XNH3increases, the absolute chemiluminescence intensity of these radicals decreases, whereas the relative contribution of broadband emission from products such as H2O and CO2 increases. Under otherwise identical conditions, the time-averaged integrated chemiluminescence intensity progressively decreases with increasing XNH3, indicating a reduction in the overall reaction activity.

Figure 2.

(a) Original spectral data and (b) baseline-corrected and normalized spectra at different XNH3.

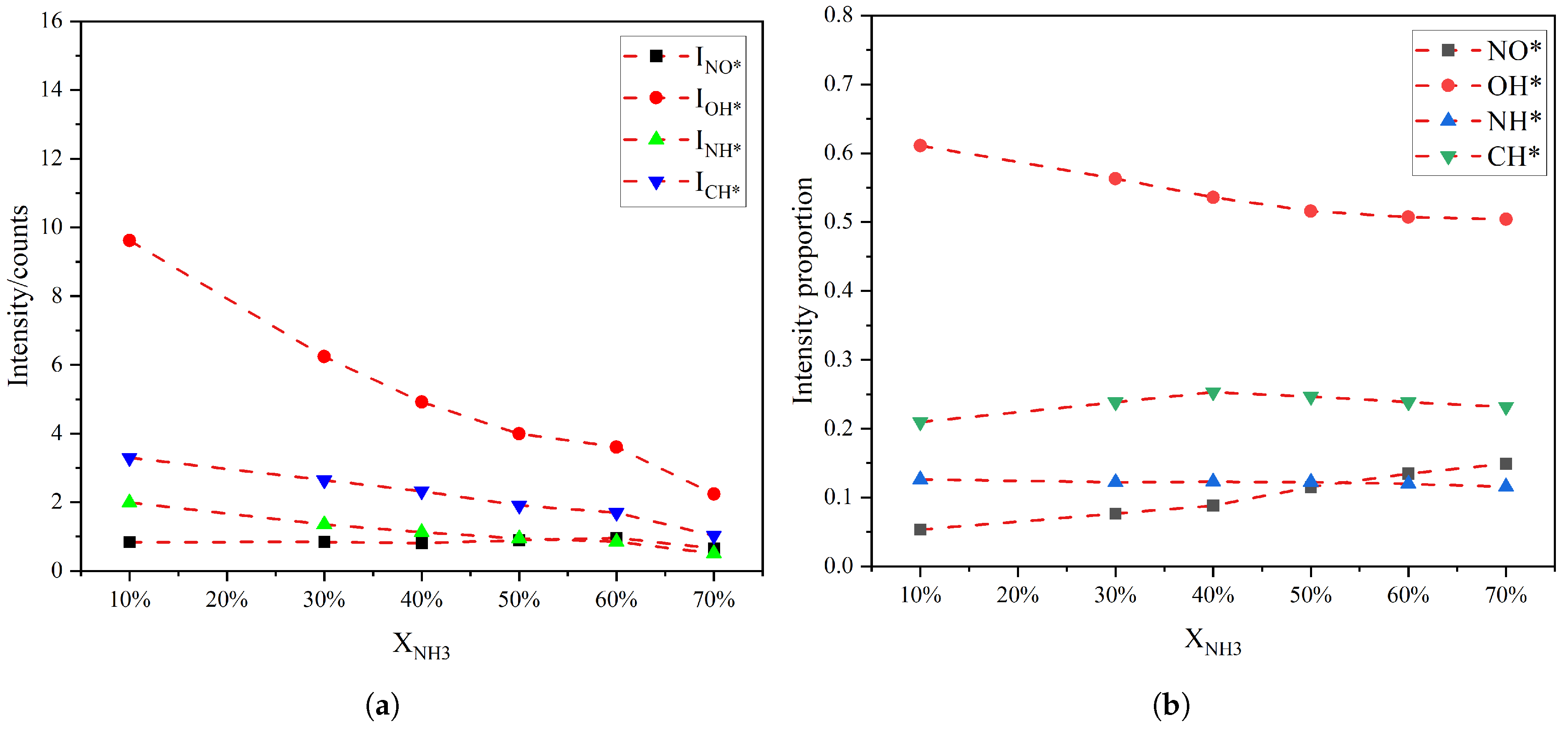

To further analyze how radical intensity and radical intensity ratios vary with the XNH3 different narrow spectral bands were selected for each radical, and the chemiluminescence intensity and corresponding intensity ratios were obtained by integrating over these bands. The uncertainty of the spectral-intensity ratios is primarily governed by baseline-removal settings, background drift, spectral overlap among different radical emissions, residual instrument-response uncertainty after calibration, and run-to-run flame fluctuations. To mitigate these effects, we performed a swept-parameter airPLS baseline correction, applied background subtraction during acquisition, adopted narrow integration windows dominated by a single radical feature, used instrument-response calibration, and employed time-integrated spectra to reduce the influence of short-time fluctuations on the integrated intensities. The integration intervals were chosen as follows: 220–275 nm for NO*, 300–327 nm for OH*, 328–347 nm for NH*, and 429–444 nm for CH*. The variations in the absolute intensities and radical chemiluminescence fraction in the total emission are shown in Figure 3. In terms of absolute intensity, the chemiluminescence from OH*, NH*, and CH* decreases with increasing XNH3, whereas the NO* emission remains relatively stable. In terms of relative contribution, the NO* fraction in the total emission increases almost monotonically with XNH3, the OH* fraction decreases monotonically, and the NH* fraction also decreases but with a smaller variation than OH*. NH* chemiluminescence is closely linked to reactions NH2 + O → NH* + OH and N + OH → NH* + O. As the CH4 fraction decreases with increasing XNH3, the hydrocarbon-driven H and OH radical concentration may be reduced, which can suppress NH* formation and thus lead to a monotonic decrease in NH* emissions. The CH* fraction reaches a maximum at XNH3 of approximately 40%. It should be noted that when the XNH3 exceeded about 70%, the mixed fuel cannot be ignited.

Figure 3.

(a) The intensity of radical radiation and (b) its proportion in the total radiation as a function of XNH3.

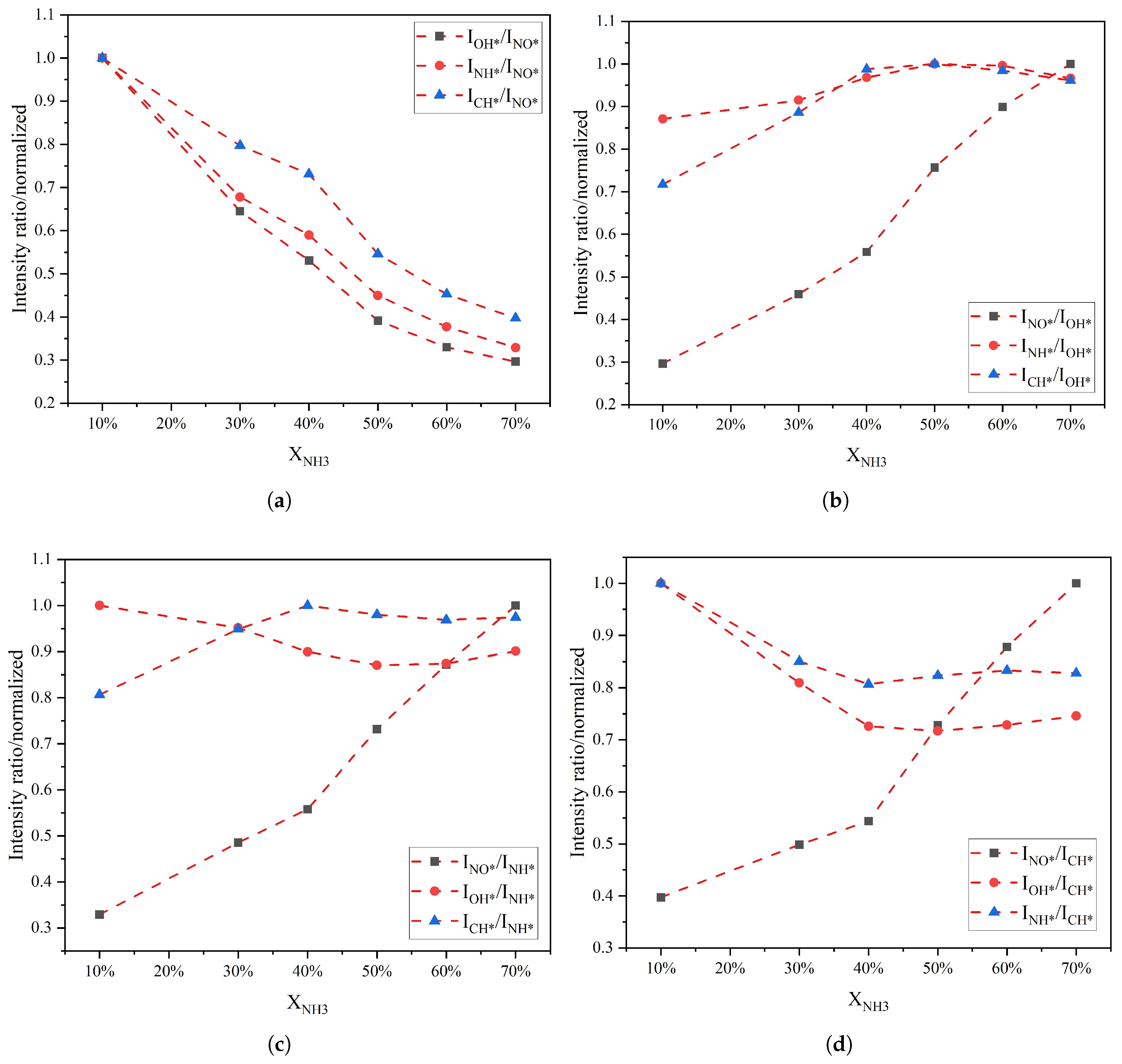

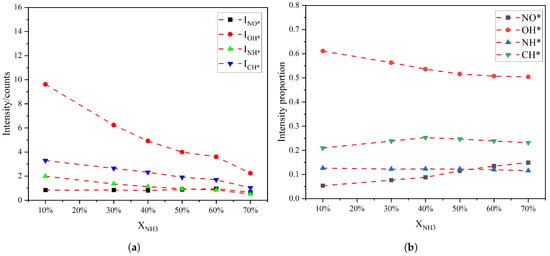

Figure 4 shows the variation in different radical intensity ratios as a function of the XNH3. Overall, the ratios involving NO* exhibit a steadily decreasing trend as the XNH3 increases. In contrast, the ratios involving OH*, NH*, and CH* show non-monotonic trends. Taking ratios with CH* as an example, the NO*/CH* and OH*/CH* intensity ratios decrease monotonically between 10% and 40% ammonia fuel fraction, whereas between 40% and 70% approximated a quadratic dependence on XNH3. The NH*/CH* intensity ratio increases monotonically in the range 10–40%, and its slope becomes steeper between 40% and 70%, indicating that the relative contribution of NH* increases substantially with increasing XNH3. All ratio curves exhibit an inflection point at XNH3 of 40%, indicating a transition in combustion mode from oscillatory to stable combustion, which is consistent with the behavior observed in the chemiluminescence images. The CH*/OH* intensity ratio, in particular, exhibits opposite trends on either side of 40%, switching from a monotonically increasing trend to a monotonically decreasing trend.

Figure 4.

Variation in the intensity ratios of different free radicals with XNH3: the ratio of other free radicals to (a) NO*, (b) OH*, (c) NH* and (d) CH*.

By combining the results of Figure 3 and Figure 4, as the XNH3 increases, the intensities of OH* and CH*, which are indicative of reaction intensity in the reaction zone, decrease under both oscillatory and SC mode, indicating a reduction in overall combustion efficiency. The CH* and OH* chemiluminescence intensities, as well as their intensity ratio, are sensitive to the combustion mode, exhibiting distinct trend changes with increasing XNH3, and can therefore be used as indicators of the combustion mode. Compared with the other radicals, the NH* chemiluminescence and its fraction in the total emission exhibit a stable, monotonic decrease with increasing NH3 fraction. The intensity ratios involving NO* are relatively insensitive to the combustion mode, showing a consistent trend and monotonic variation with increasing XNH3, and can thus be used as an indicator of XNH3. It can be seen that, at XNH3 = 0.40, there is a clear turning point in all distributions. This is because when XNH3 is greater than or equal to 0.40, the flame oscillations are no longer significant and the flame exhibits SC mode. The spectral emission characteristics accurately capture this transition. However, spectral analysis alone cannot distinguish between LCO and QPO modes; therefore, 2D chemiluminescence imaging is required for further analysis.

3.2. Free Radical Imaging Features Under Different XNH3

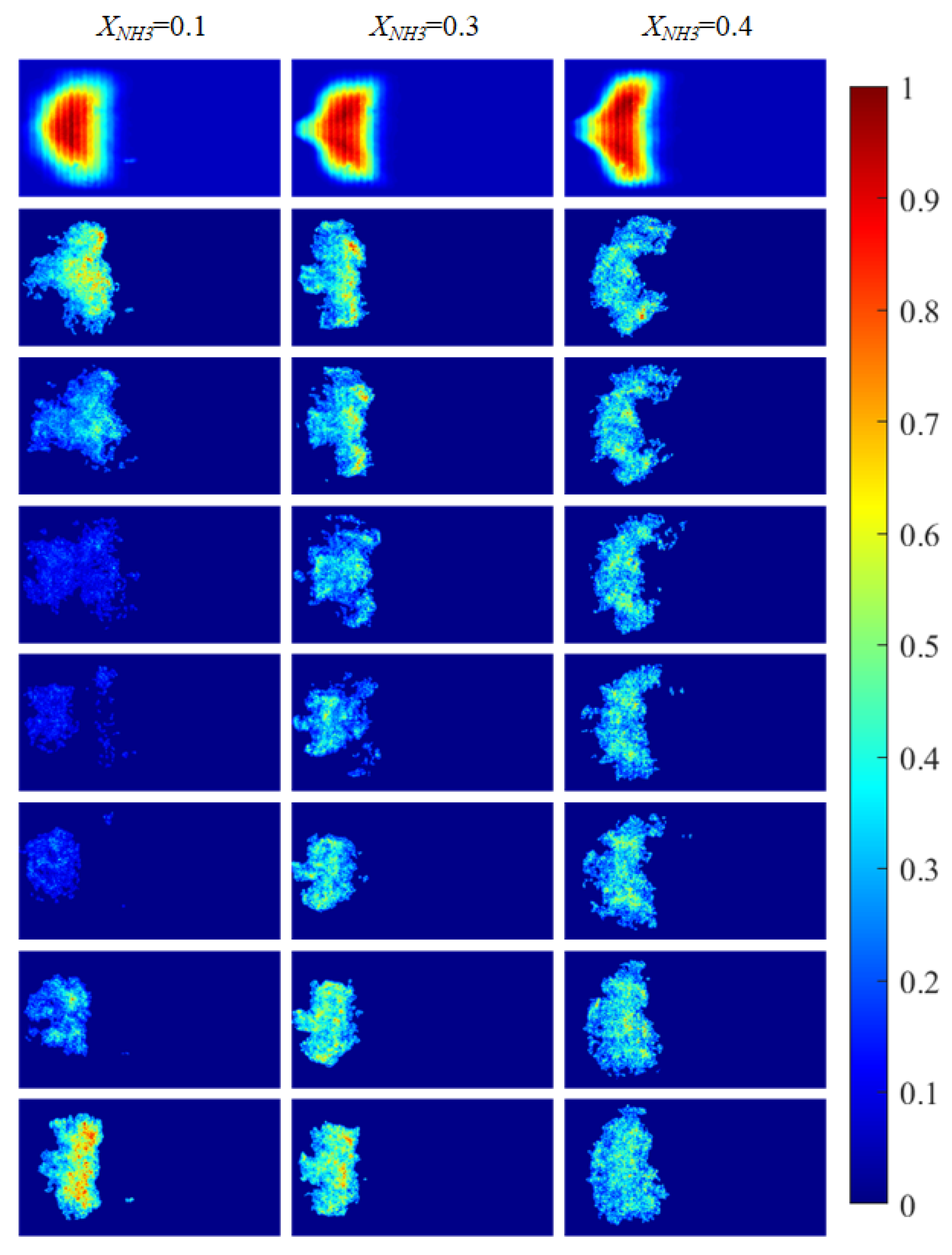

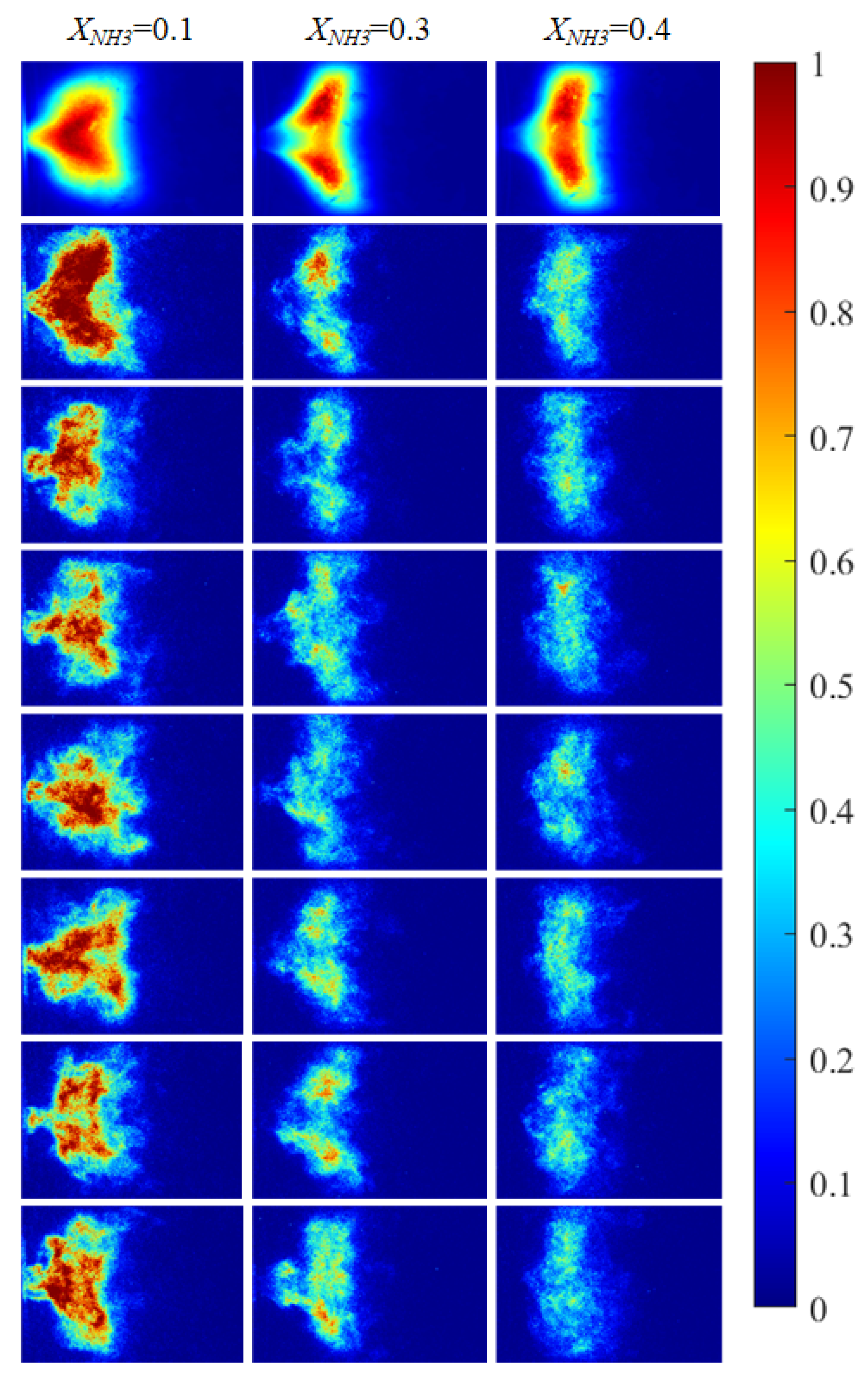

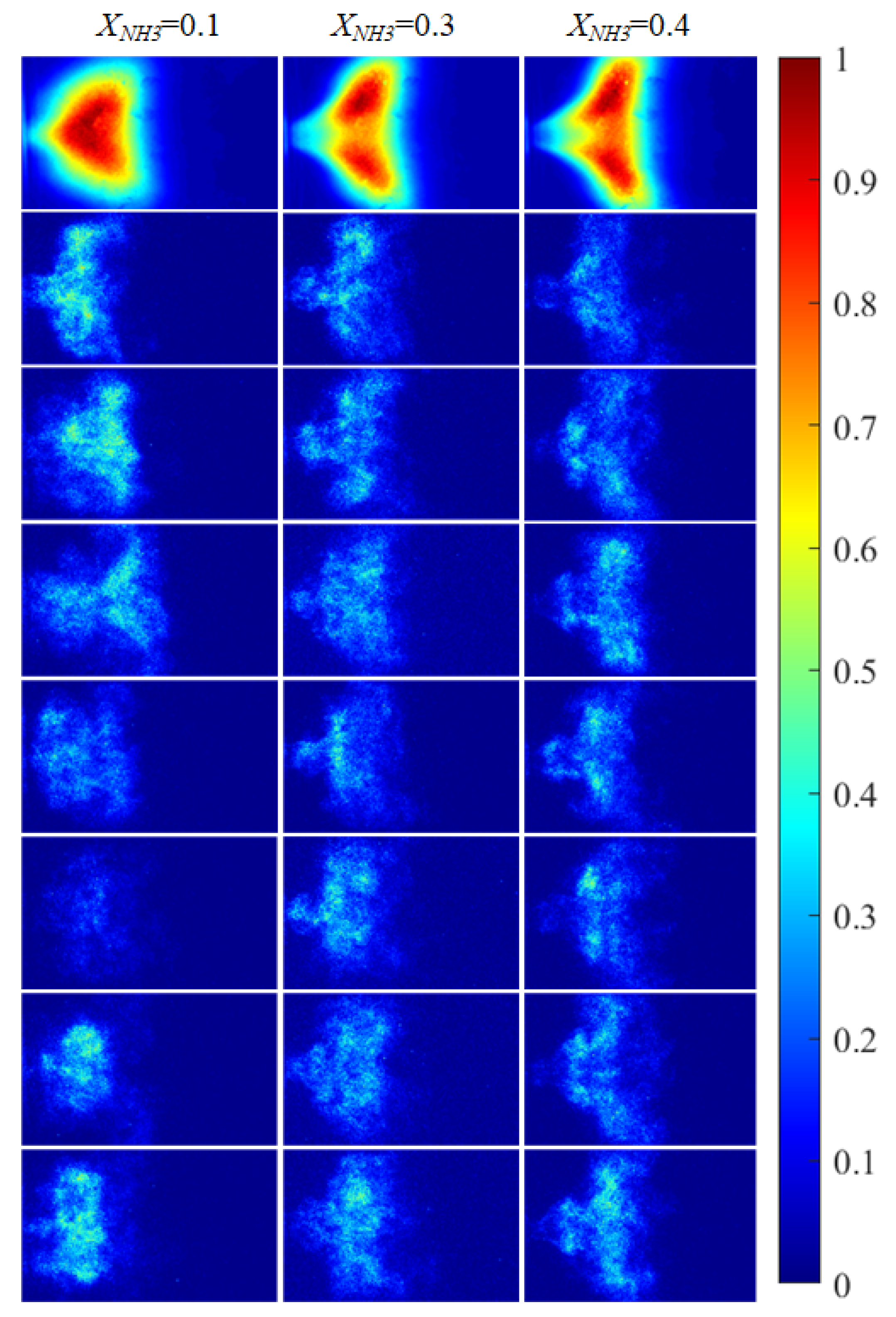

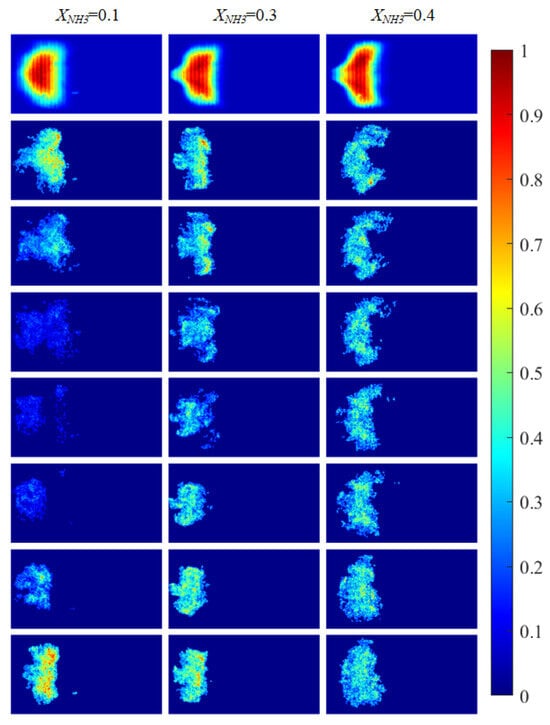

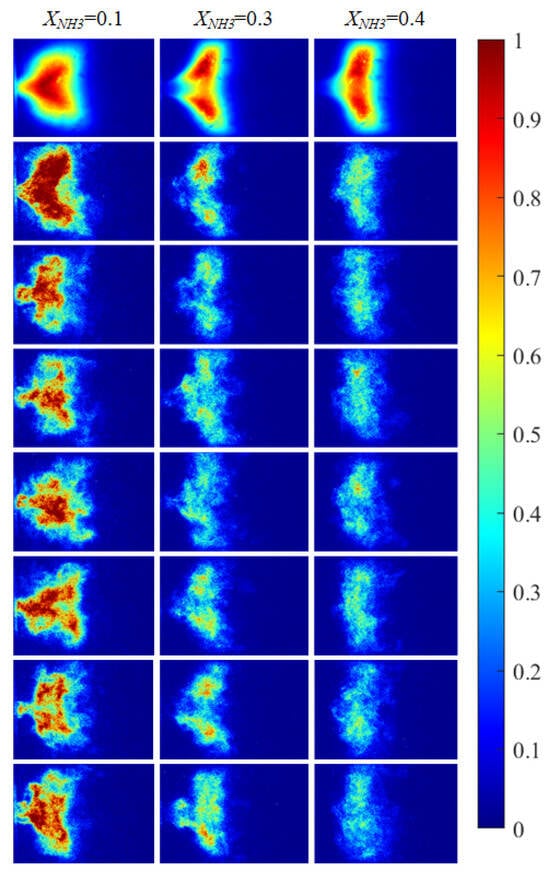

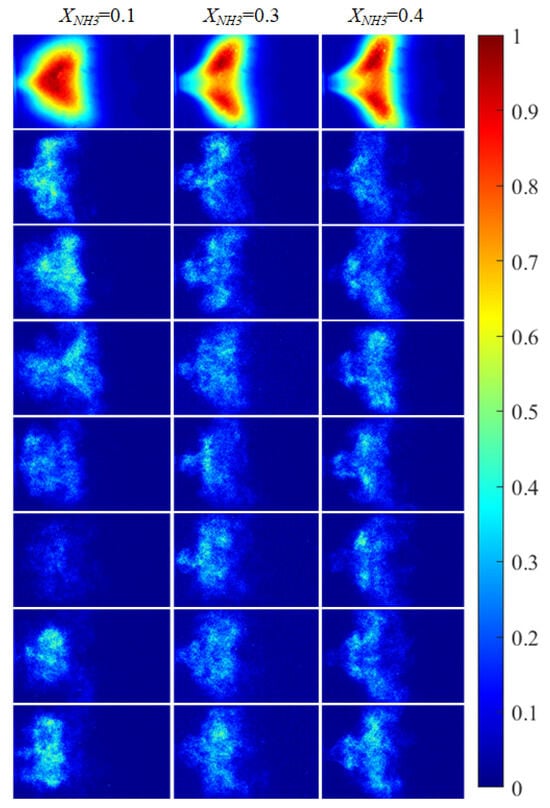

Based on the imaging system described in Section 2.2, the radical chemiluminescence images were recorded as 2D grayscale intensity fields (digital numbers, DN). Before further processing, all images were pre-processed. For CH* imaging, each raw frame was first denoised using a median filter and then corrected for fixed-pattern noise (FPN), yielding a pre-processed intensity field . For OH* and NH* imaging, median-filter denoising was applied. Subsequently, for CH* imaging, a time-averaged image was obtained by averaging a continuous sequence of 2397 frames, as shown in the first row of Figure 5. For OH* and NH* imaging, the time-averaged images were computed by averaging 620 instantaneous frames for each radical, as shown in the first rows of Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively. The rows below the first row in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 present representative instantaneous snapshots of each radical. To improve the readability of the spatial intensity distribution, all images in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 were globally normalized to [0, 1] for visualization using a single reference intensity , defined as the global maximum over the entire acquisition record for the corresponding radical, i.e., . As shown in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, due to thermoacoustic instability, both the 2D distributions and the intensity levels of the radicals exhibit pronounced oscillatory behavior. The detailed observations are discussed below.

Figure 5.

CH* chemiluminescence images of the swirling flame at different XNH3. The first row shows time-averaged images over a 10 s acquisition interval, and the subsequent rows are instantaneous single frames.

Figure 6.

OH* chemiluminescence images of the swirling flame at different XNH3. The first row shows time-averaged images over a 10 s acquisition interval, and the subsequent rows are instantaneous single frames.

Figure 7.

NH* chemiluminescence images of the swirling flame at different XNH3. The first row shows time-averaged images over a 10 s acquisition interval, and the subsequent rows are instantaneous single frames.

The combustion morphology of the flame differs for different XNH3. Due to the periodic oscillations of the swirling flame, the flame morphology also exhibits periodic variations. Imaging of the distributions of three radicals (CH*, OH*, and NH*) at XNH3 ratios of 10%, 30%, and 40% was carried out to analyze their spatial distributions, periodic variation characteristics, and corresponding morphological features. CH* chemiluminescence images were acquired using a high-speed camera. After noise reduction and image enhancement, a region-growing algorithm was applied to extract the flame region and eliminate residual noise and background interference. OH* and NH* images were acquired using the ICMOS camera with narrowband filters centered at 310 nm and 337 nm, respectively. The processed chemiluminescence images for the three radicals are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5 shows CH* chemiluminescence images. At XNH3 = 0.10, the flame exhibits a LCO regime, with large variations in flame morphology and grayscale distribution over time. At XNH3 = 0.30, the system is in a QPO regime, representing a transitional state between high-amplitude LCO and low-amplitude SC. Oscillations persist in the combustor, but their amplitudes are lower than in the LCO regime. At XNH3 = 0.40, the system exhibits SC, characterized by random, low-intensity oscillations and no clear periodicity in the images. Similar oscillatory behavior is observed in the OH* (Figure 6) and NH* (Figure 7) chemiluminescence fields.

The value of XNH3 also strongly affects the spatial distributions of the three radicals. At XNH3 = 0.10, the CH*, OH*, and NH* chemiluminescence fields are highly similar, indicating that the three radicals are generated at comparable locations and are approximately uniformly distributed within the reaction zone. As XNH3 increases, however, the OH* and NH* distributions gradually deviate from that of CH*, and these differences become more pronounced with increasing XNH3. At XNH3 = 0.30 and 0.40, the OH* and NH* fields are noticeably more elongated downstream than the CH* field. This behavior arises because, at low XNH3, the fuel contains a high fraction of CH4, so the flame dynamics are primarily governed by CH4 oxidation. Under these conditions, CH* is the dominant chemiluminescent product. At higher XNH3, combustion is instead dominated by NH3, and NH* is mainly formed via the reaction NH2 + H → NH + H2, so its emission is directly linked to the local NH3 concentration. Furthermore, the relatively slow overall reaction rate of NH3 leads to a longer flame and, consequently, to a more elongated OH* and NH* emission region. These observations demonstrate that, at low XNH3, CH* chemiluminescence can be used as a direct indicator of the flame reaction zone and overall reaction rate, whereas at higher XNH3 the OH* and NH* chemiluminescence distributions must also be considered.

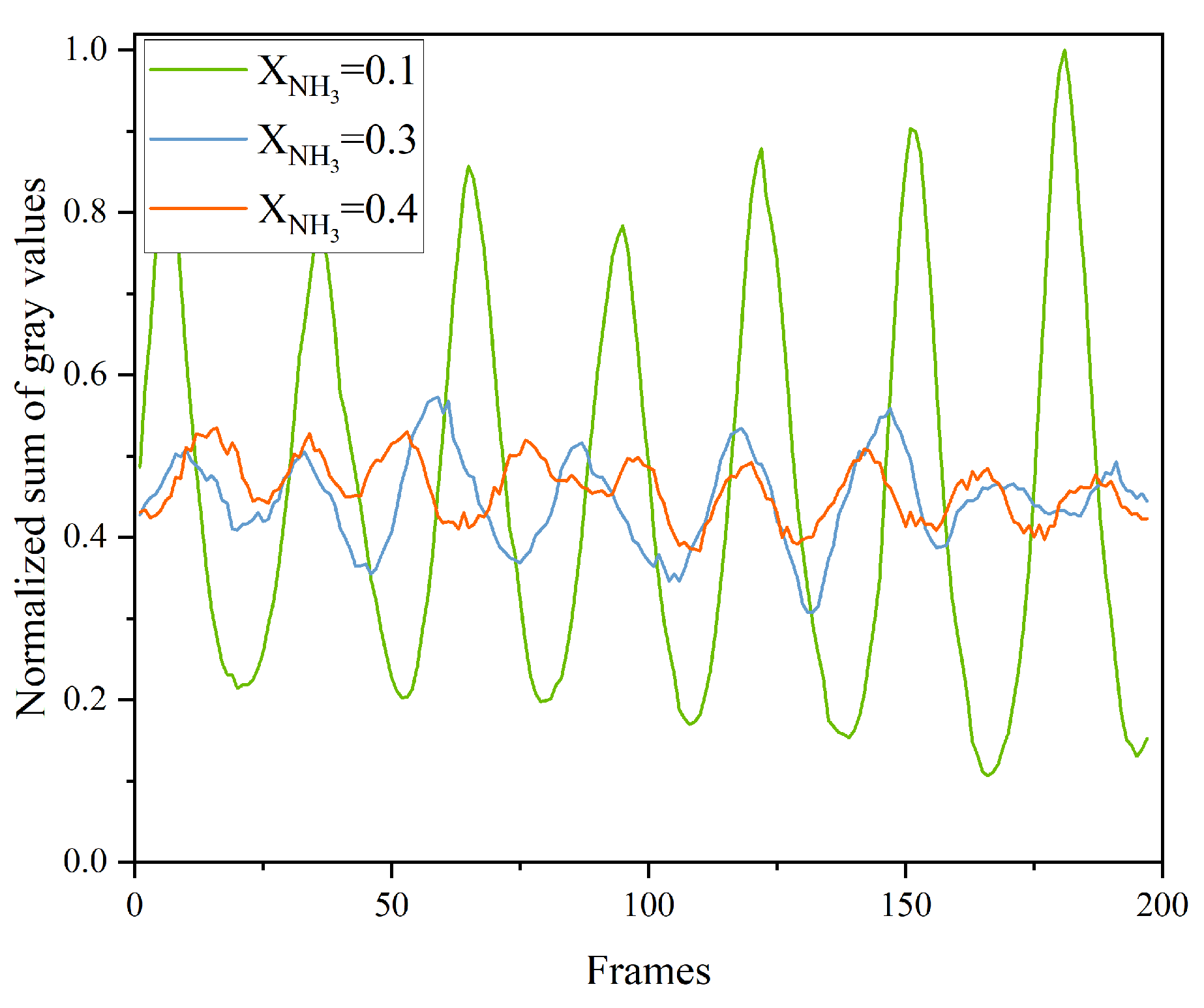

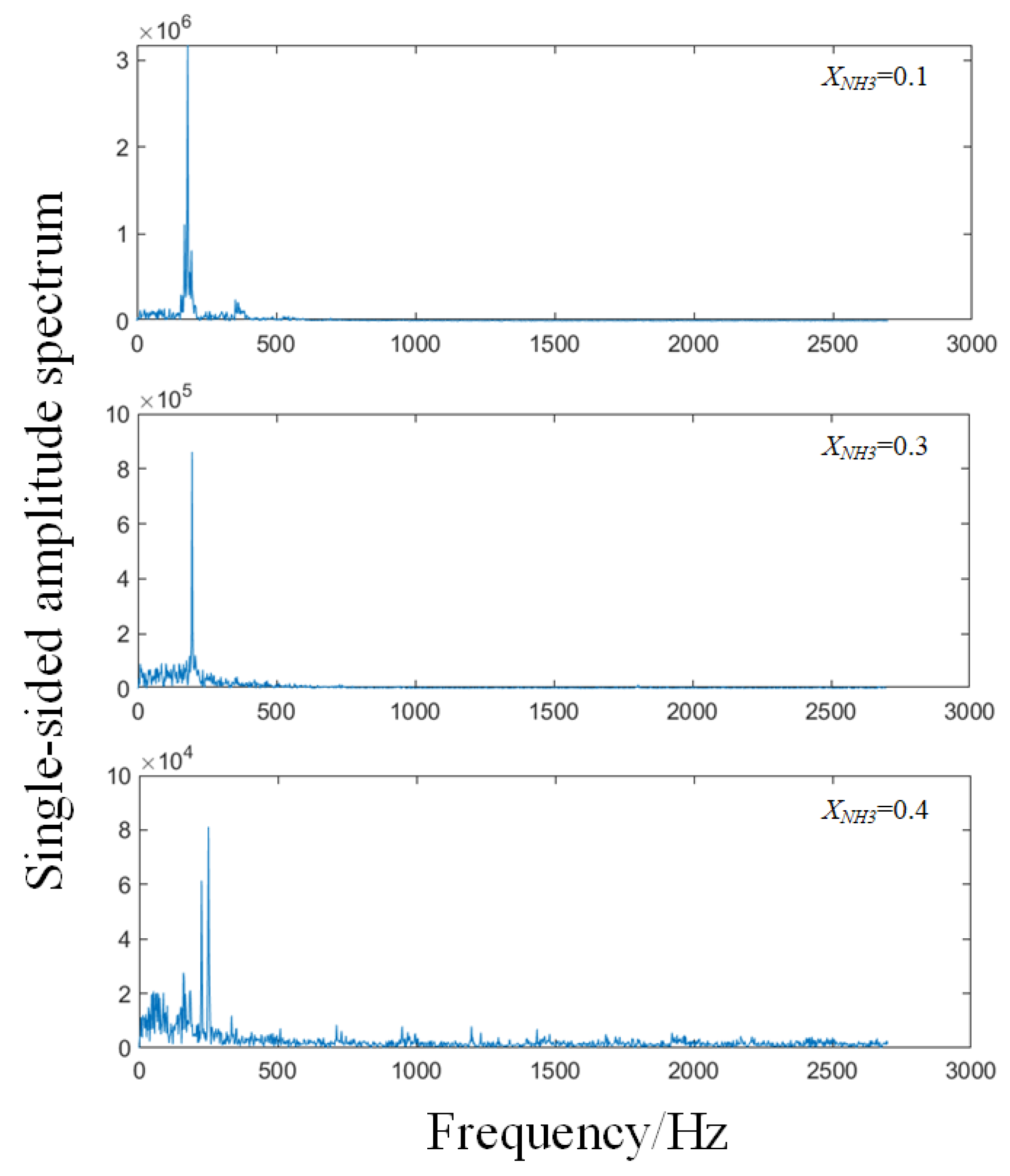

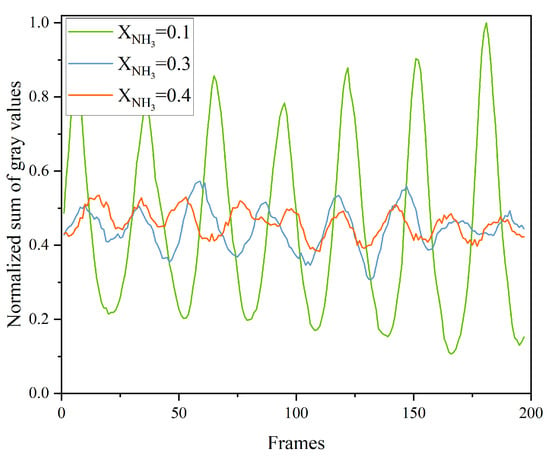

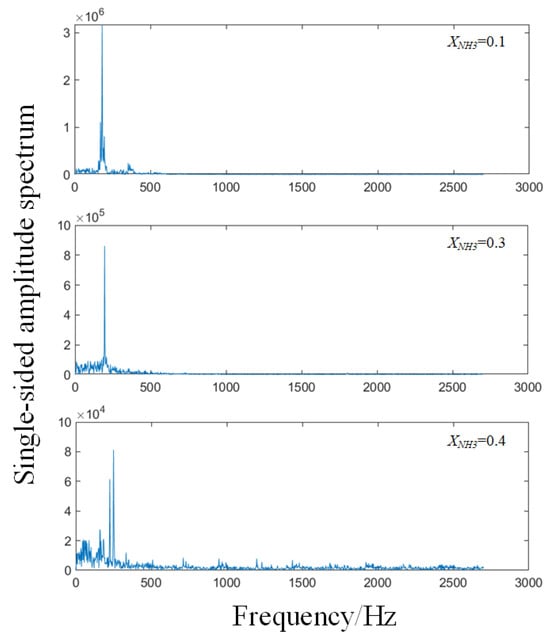

To assess flame combustion stability, the total grayscale value of CH* chemiluminescence was calculated for 200 consecutive frames for each value of XNH3, and the results are shown in Figure 8. As XNH3 increases, the total emission intensity markedly decreases, which is attributed to the lower combustion efficiency of NH3 compared with CH4. At XNH3 = 0.10, the oscillation period is stable, with the peak-to-peak variation in the total grayscale signal ranging from 0.5 to 0.9. At XNH3 = 0.30, although the oscillation period remains relatively stable, the frequency increases compared with XNH3 = 0.10, and the peak-to-peak value is reduced to the range 0.1–0.25. At XNH3 = 0.40, the oscillatory component of the signal is weak and the period is no longer clearly discernible. Frequency analysis of the total grayscale signal yields the corresponding power spectral density, as shown in Figure 9. For XNH3 = 0.10, the first and second dominant frequencies are 182.48 Hz and 180.23 Hz, respectively; for XNH3 = 0.30, they are 195.99 Hz and 198.25 Hz; and for XNH3 = 0.40, they are 159.95 Hz and 225.28 Hz. With increasing XNH3, the dominant mode shifts and higher frequencies become more prominent. This behavior is associated with changes in the shape of the recirculation zone, which increase the ratio of the effective average sound speed to the effective cavity length and thereby tend to increase the modal frequencies. For XNH3 = 0.10 and 0.30, the relative difference between the first and second dominant frequencies is less than 1.5%, indicating that they belong to the same thermoacoustic mode. However, when XNH3 = 0.40, the relative difference between the first and second dominant frequencies exceeds 26%, indicating the presence of at least two distinct modes in the flame and preventing the establishment of a single, stable periodic oscillation.

Figure 8.

Normalized sum of grayscale values per frame of CH* chemiluminescence images at different XNH3.

Figure 9.

Frequency spectra of the sum of grayscale values per frame of CH* chemiluminescence images at different XNH3.

3.3. Morphology-Based Clustering and POD Analysis of Radical Chemiluminescence at Different XNH3

To analyze the temporal and spatial distributions of radical chemiluminescence image features under different NH3 conditions, we employed k-means clustering and proper orthogonal decomposition (POD), respectively.

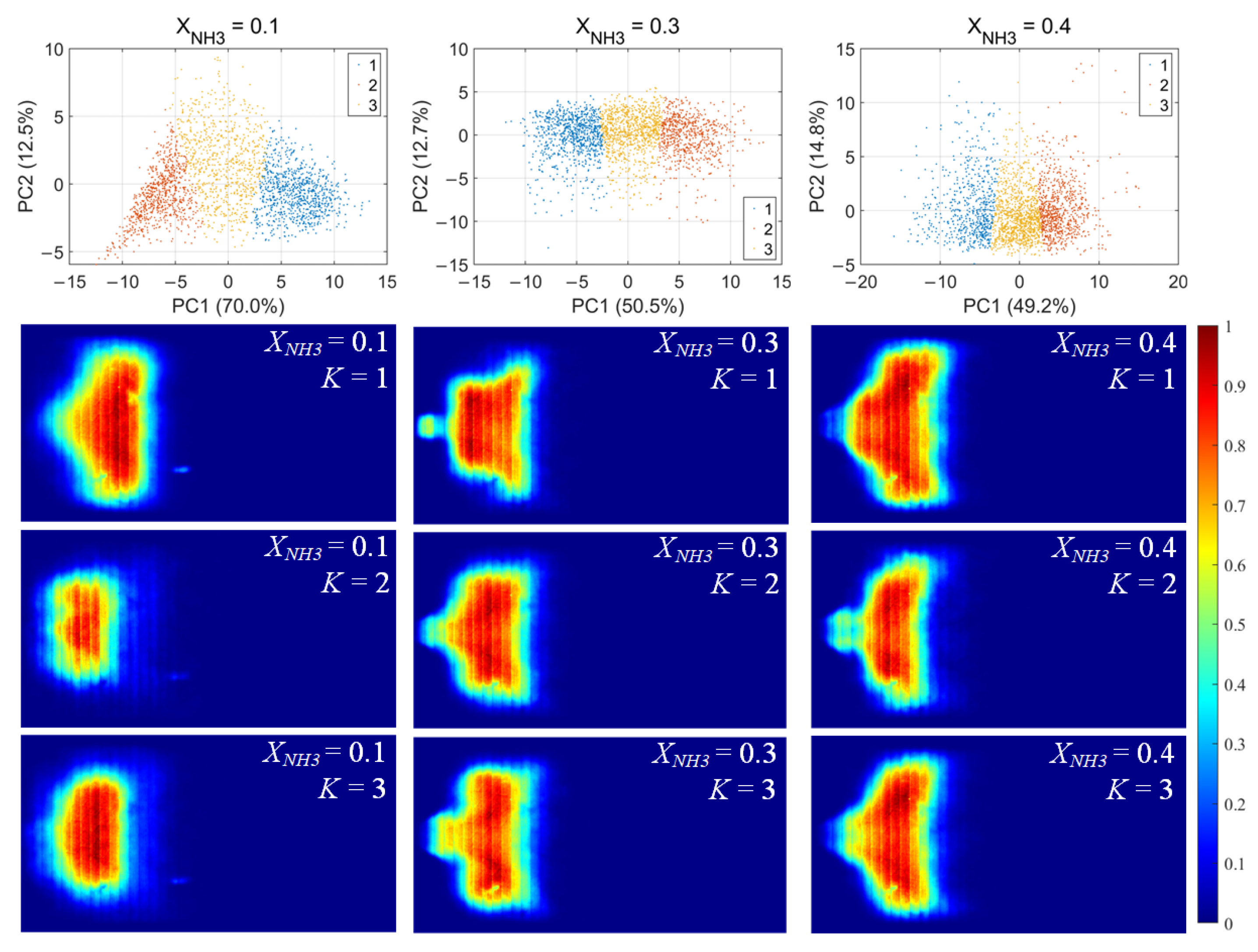

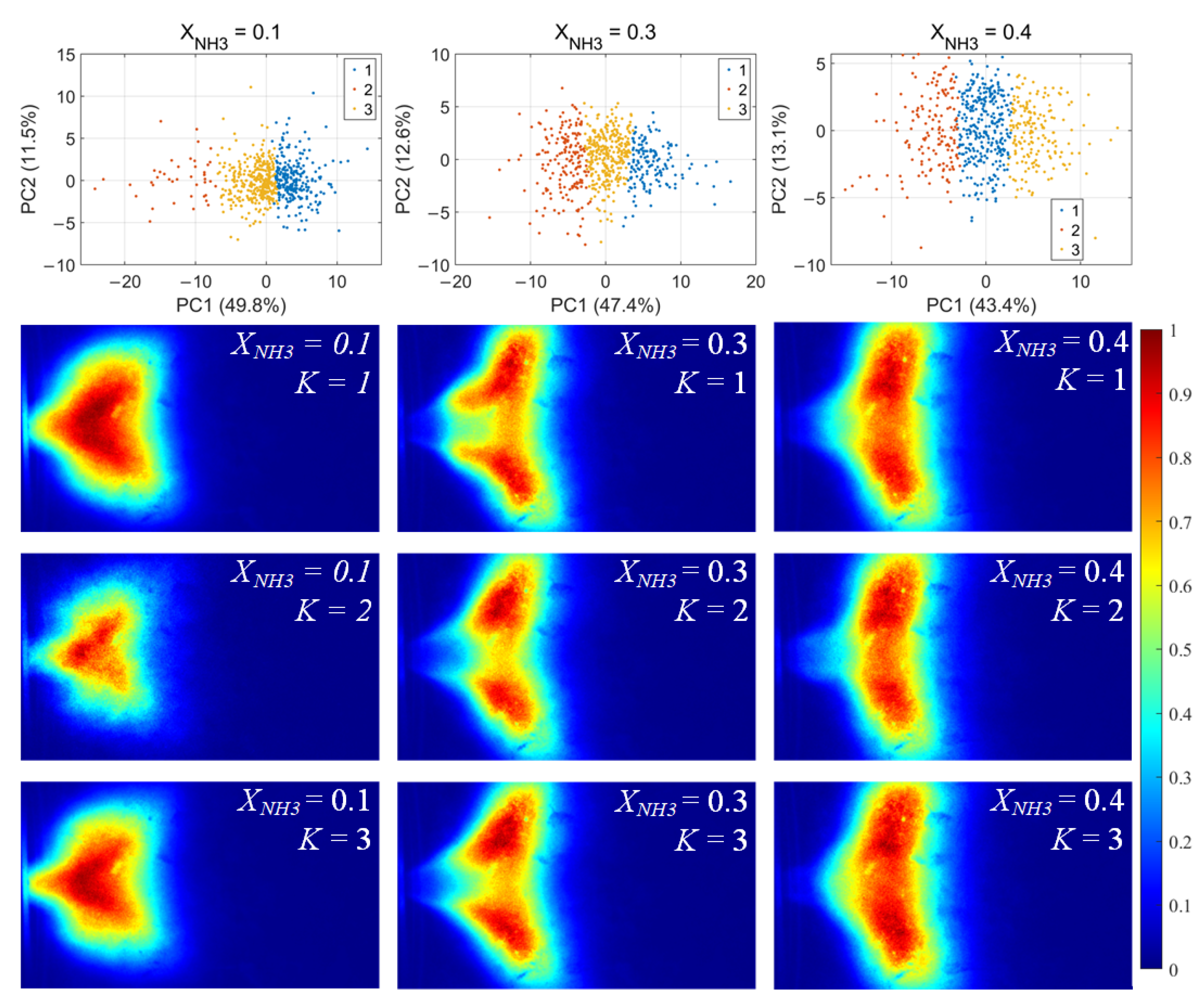

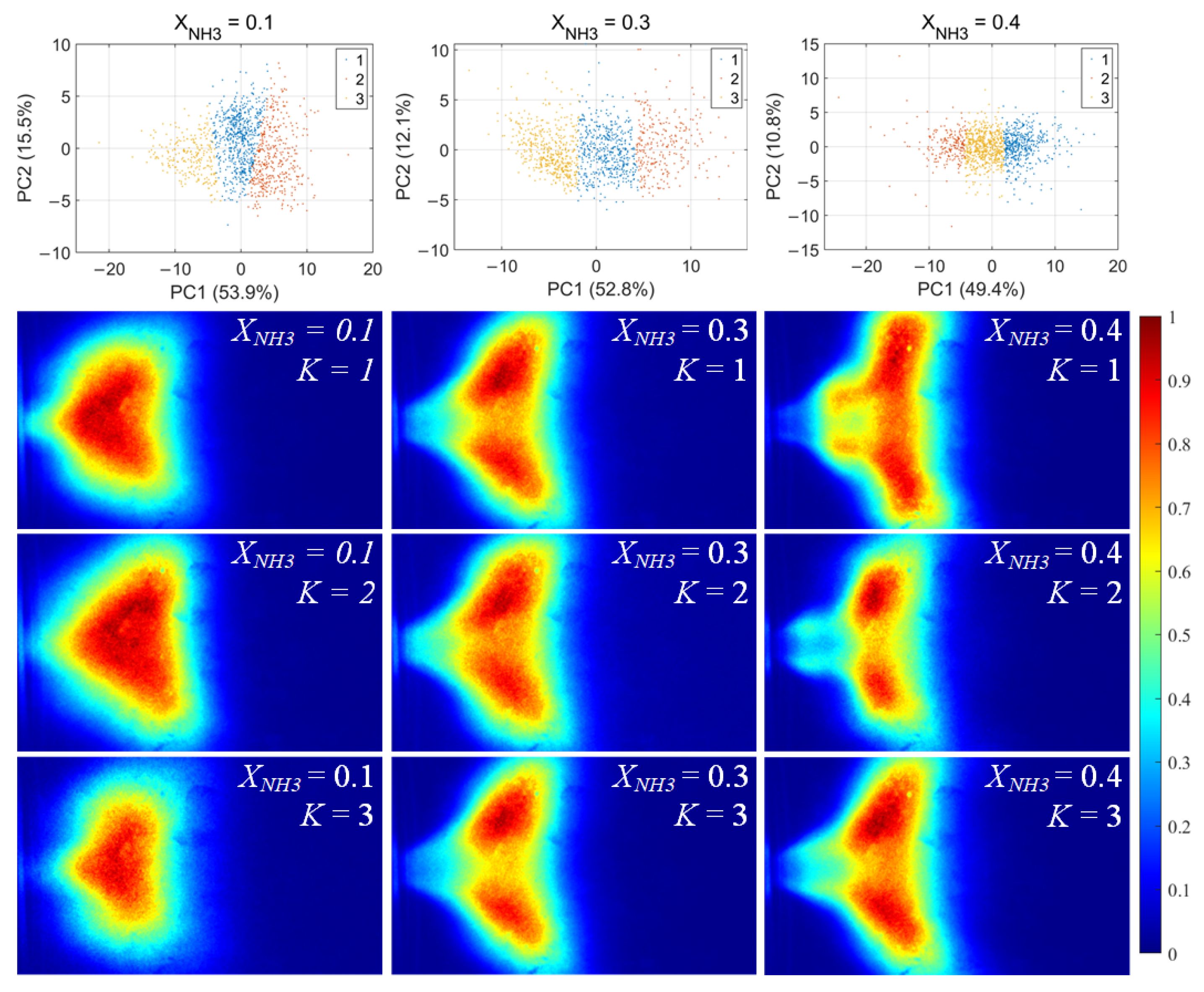

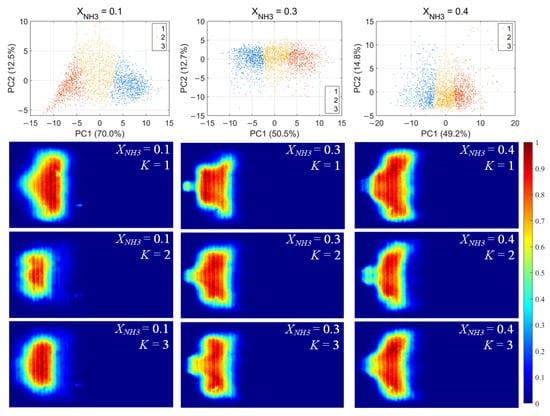

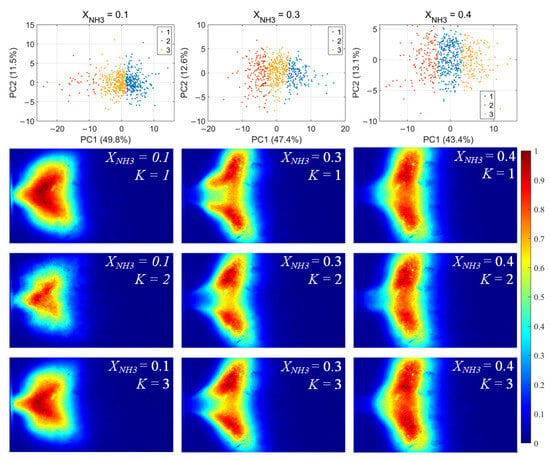

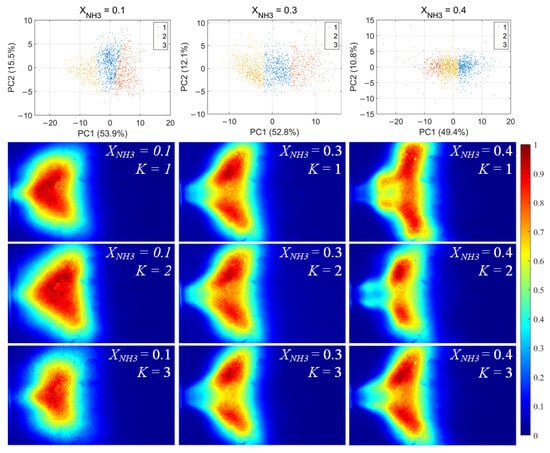

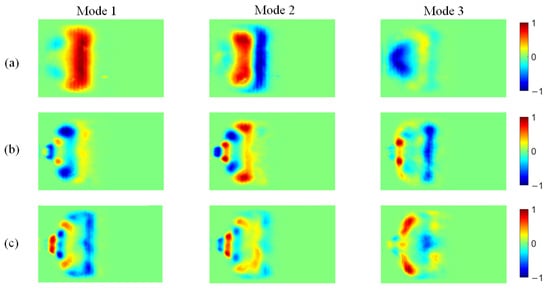

For each flame image, 46 morphology features were calculated, including the mean and standard deviation of the grayscale, the flame area and perimeter, the equivalent circular radius, the principal gradient direction, and the raw moments, central moments, and Hu invariant moments, forming a 46-dimensional feature vector. After standardizing these feature vectors, principal component analysis (PCA) was first applied to extract the principal directions in feature space. Then, k-means clustering was performed for unsupervised classification, dividing the samples into three clusters for each value of XNH3. The clustering results and the corresponding average flame images for each cluster are shown in Figure 10. Among the principal components, PC1 is the primary dimension describing flame morphology, with strong contributions from the mean grayscale, flame area, equivalent radius, and low-order raw moments. A small PC1 score corresponds to low overall brightness in the radical chemiluminescence images and a small flame area, indicating that the radical distribution is in a contracted state. Conversely, a large PC1 score indicates high imaging brightness and a large flame area, with the radical distribution in an expanded state. PC2 is mainly associated with the grayscale standard deviation, the directional gradient frequency, the central moments, and the Hu-invariant moments. A smaller PC2 score indicates a more uniform grayscale distribution in the image, whereas a larger PC2 score corresponds to stronger image contrast, more pronounced edge wrinkling, and a more elongated flame shape. Comparing Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, PC1 accounts for the majority of the variance between clusters and thus represents the main axis of classification under different combustion conditions.

Figure 10.

CH* chemiluminescence clustering results (first row) and corresponding mean image for each cluster.K denotes the cluster index obtained from the k-means classification.

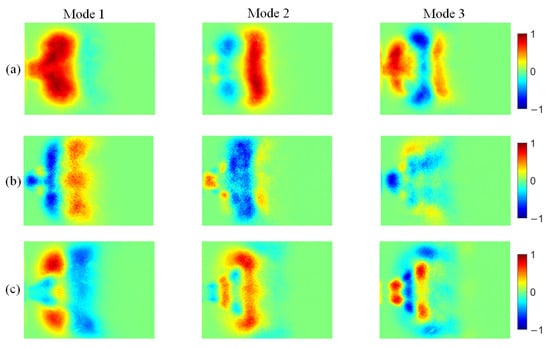

Figure 11.

OH* chemiluminescence clustering results (first row) and corresponding mean image for each cluster.K denotes the cluster index obtained from the k-means classification.

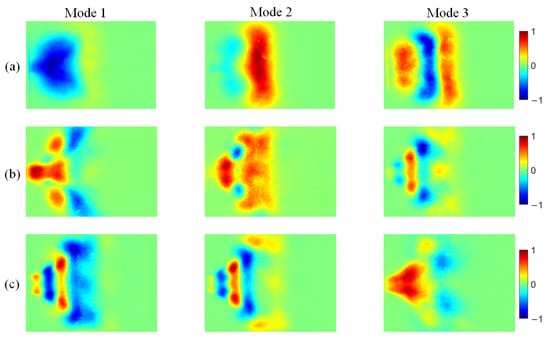

Figure 12.

NH* chemiluminescence clustering results (first row) and corresponding mean image for each cluster.K denotes the cluster index obtained from the k-means classification.

Under various operating conditions, the radical chemiluminescence images can be classified into three main categories, corresponding to the lowest, highest, and intermediate emission-intensity states within the oscillation cycle. For CH* imaging, at low XNH3, the oscillation period is stable and the three classes of flames exhibit pronounced differences in brightness, flame area, and morphology, indicating that the system undergoes large-amplitude periodic fluctuations in energy release. As XNH3 increases, the flame morphology becomes more elongated, the oscillation intensity decreases, and the differences among the three classes become relatively smaller. The OH* and NH* chemiluminescence fields exhibit the same qualitative trends under different operating conditions. A comparison of the clustering results for the three radicals shows that, at low XNH3, the spatial distributions and morphological characteristics of OH* and NH* are highly similar to those of CH* emission, indicating that the CH4 reaction dominates under these conditions. However, as XNH3 increases, the dominant morphologies of OH* and NH* become significantly different from that of CH*. These results are consistent with the conclusions drawn from the analyses presented above.

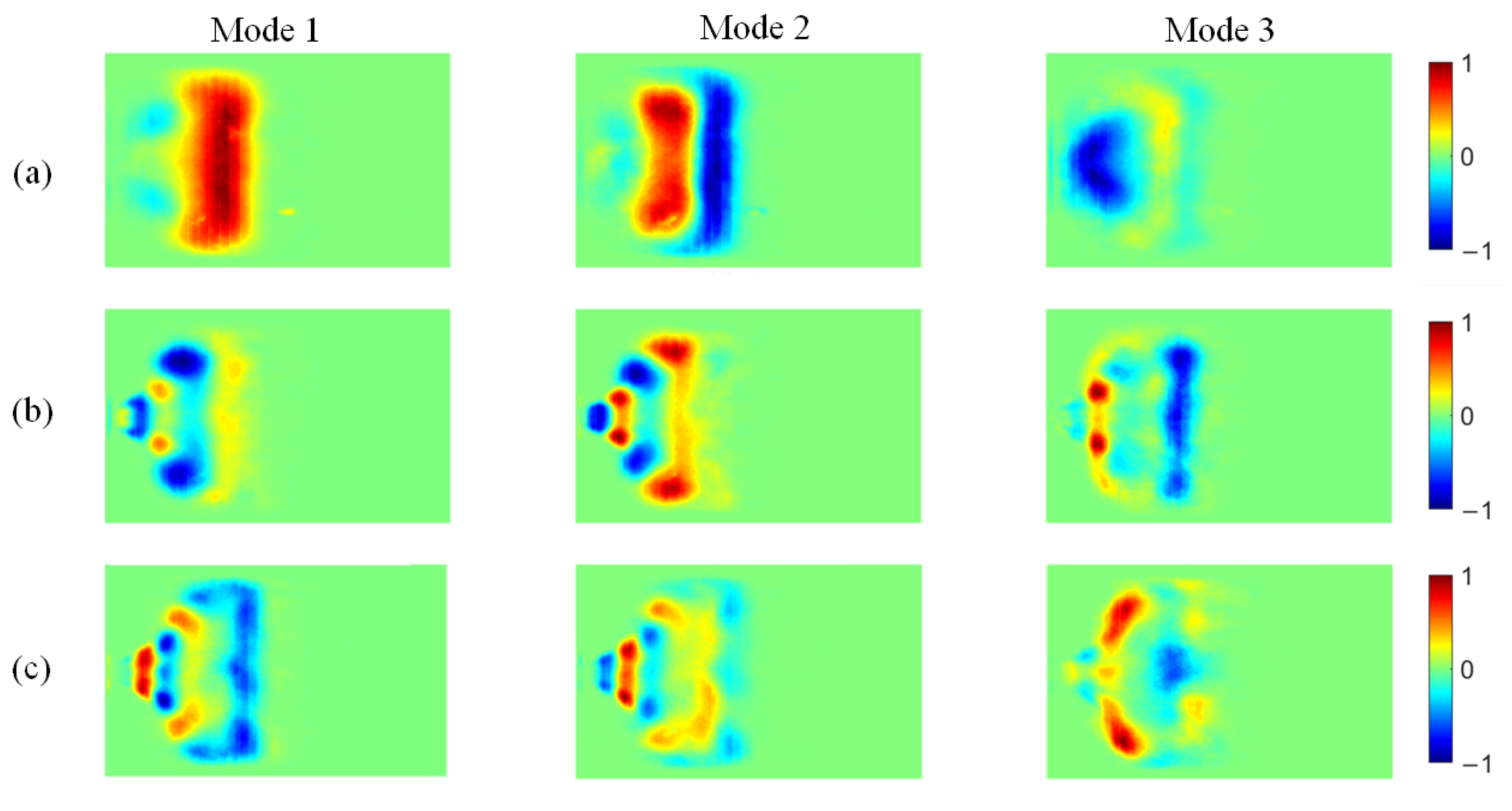

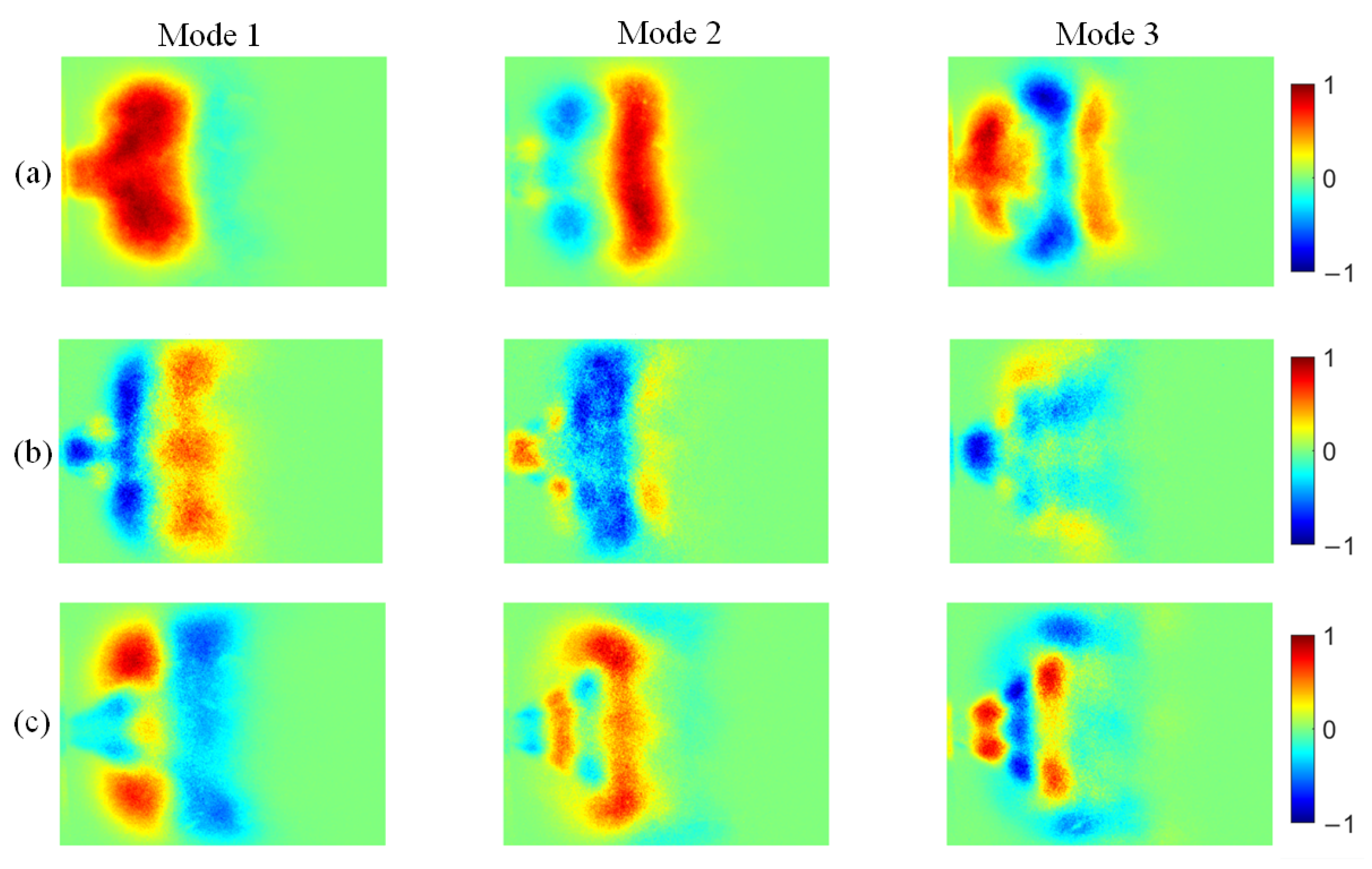

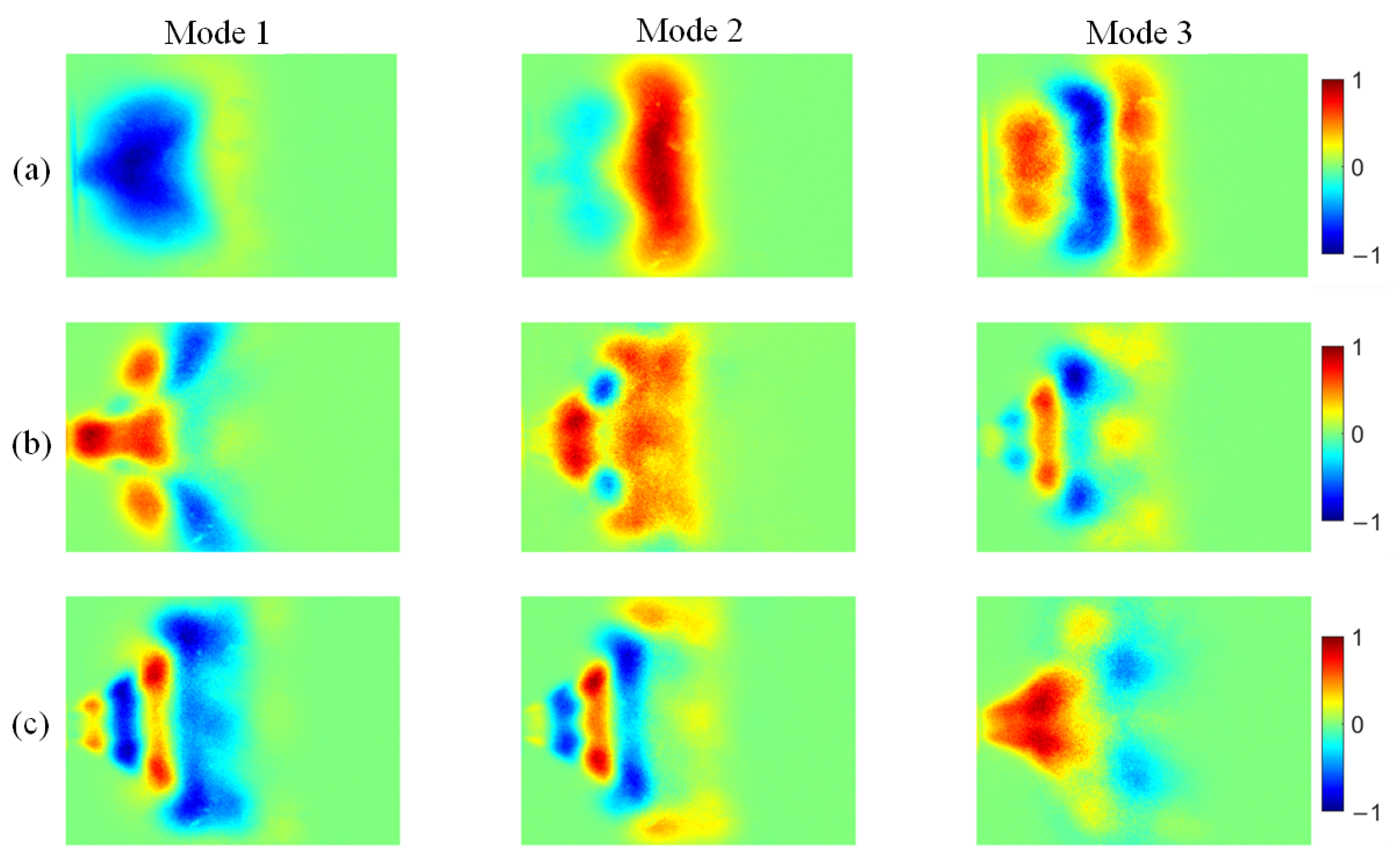

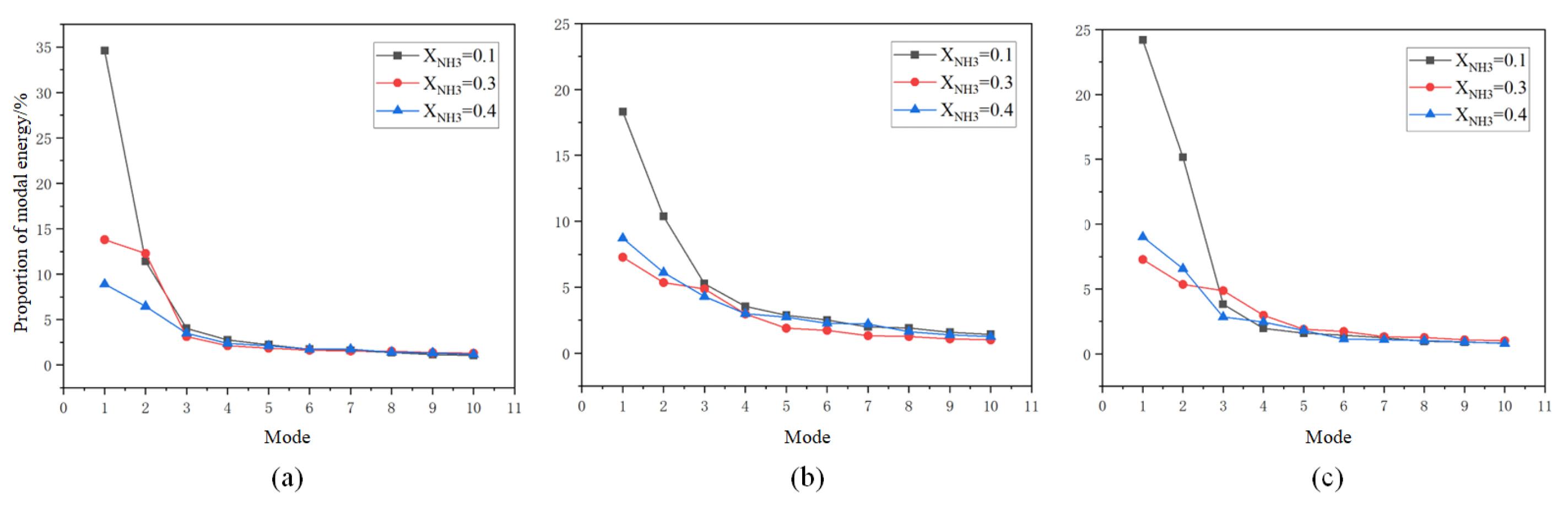

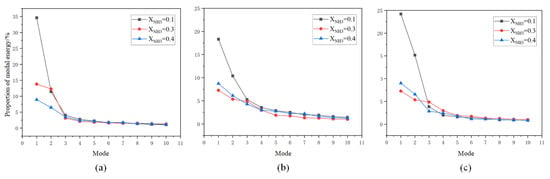

POD analysis was taken to extract the spatial modal structures of each radical field under different ammonia blending ratios. The POD modes were ranked by decreasing modal energy eigenvalues, enabling a clear identification of the dominant oscillatory structures and their spatial evolution. Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the two-dimensional distributions of the first three POD modes for each radical at all operating conditions, while Figure 16 summarizes the energy fractions of the first ten modes.

Figure 13.

POD modes of CH* chemiluminescence at different ammonia blending ratios: (a) 10%, (b) 30%, and (c) 40%.

Figure 14.

POD modes of OH* chemiluminescence at different ammonia blending ratios: (a) 10%, (b) 30%, and (c) 40%.

Figure 15.

POD modes of NH* chemiluminescence at different ammonia blending ratios: (a) 10%, (b) 30%, and (c) 40%.

Figure 16.

Energy fractions of POD modes for (a) CH*, (b) OH*, and (c) NH* at different ammonia blending ratios.

At an ammonia blending ratio of 10%, the first three modes collectively contain the majority of the fluctuation energy for all three radicals, indicating that low-order coherent structures dominate the instability dynamics. Consistent trends are observed across the three radical fields. In particular, Modes 1 and 2 exhibit large-scale, global patterns, which can be interpreted as representing the mean location and envelope of the primary heat-release region. In Modes 2 and 3, spatial regions with opposite phases are clearly separated, implying an axial modulation of the heat-release distribution. Notably, the spatial pattern of Mode 1 differs appreciably among the three radicals. At an ammonia blending ratio of 30%, the first two modes remain dominant, whereas the energy fractions of Mode 3 and higher-order modes are all below 5%. These two leading modes therefore capture the primary features of the time-evolving radical distributions. Moreover, Modes 1 and 2 of the three radicals display high structural similarity and consistently show axial oscillatory behavior. At an ammonia blending ratio of 40%, the modal energy of each radical field is distributed across many modes, with the energy fraction of each mode remaining below 10%. This indicates a breakdown of low-order coherence, with fluctuation energy dispersed into higher-order structures, resulting in a less organized and more spatially fragmented distribution.

4. Conclusions

To the authors’ knowledge, this work presents the first systematic investigation of thermoacoustic oscillatory instability in a premixed NH3-CH4 swirl-stabilized combustor using multi-band chemiluminescence of CH*, OH*, and NH*. Combined spectral measurements and 2D radical imaging were used to characterize both the global emission spectra and the spatial distributions of OH* and NH* in the UV band and CH* in the visible band over a range of XNH3. The results show that oscillatory combustion dominates for XNH3 < 0.40, whereas XNH3 ≥ 0.40 leads to multimode, low-amplitude stable combustion under the present lean operating condition with the equivalence ratio of 0.80. A frequency analysis of continuous CH* imaging, together with morphology-based principal component analysis and k-means clustering of 46 image features, reveals three characteristic flame-structure classes that are closely correlated with combustion mode. A custom-designed ICMOS camera based on a high-gain UV–visible image intensifier with direct coupling was developed to achieve high-sensitivity OH* and NH* imaging. As XNH3 increases and combustion becomes NH3-dominated, OH* and NH* fields progressively decouple from CH*, becoming more elongated and shifted downstream, which indicates that UV radical chemiluminescence provides indispensable information on NH3 reaction zones that cannot be captured by CH* diagnostics alone. This decoupled behavior may be attributed to the decreasing hydrocarbon fraction with increasing XNH3, which can modify the H/OH radical pool and the effective reaction-zone structure, causing different emitting species to respond differently. Meanwhile, the increased NO* fraction observed in Figure 3b may also suggest enhanced NOx formation. In addition, these trends were obtained at atmospheric pressure and laboratory scale; their transferability to high-pressure or full-scale combustors requires further validation, ideally combining exhaust-gas infrared diagnostics and numerical simulations. These findings highlight the need to incorporate multi-band radical chemiluminescence, especially OH* and NH*, into thermoacoustic diagnostics and control strategies for practical NH3-containing swirling flames.

Furthermore, by coupling the image intensifier to a high-speed camera and employing beam-splitting with FOV-splitting imaging will enable simultaneous, oscillation cycle-resolved measurements of CH*, OH*, and NH* fields, providing deeper insight into the instantaneous coupling between radical distributions and thermoacoustic modes. It should be noted that, although the broadband radiation background can be mitigated in spectral analysis via baseline correction, a rigorous removal of the broadband background in imaging typically requires two synchronously operated, identically configured cameras. Specifically, the target-radical channel and a background channel should be recorded at the same instant, after which the broadband contribution can be reduced by frame-by-frame differencing. At present, the number of self-developed ICMOS cameras available in our setup is not sufficient to enable such simultaneous dual-channel imaging. Increasing the number of ICMOS cameras is expected to enable synchronized background acquisition, which could further suppress the influence of broadband radiation in the imaging data. In future implementations, synchronization will be ensured by a common hardware trigger for all cameras to enable frame-by-frame differencing. Moreover, synchronized frame-to-frame comparisons among OH*, CH*, and NH* can resolve the phase-dependent response over a thermoacoustic cycle, helping distinguish global heat-release modulation and thereby strengthening the interpretation of instability mechanisms.

Overall, the present XNH3-dependent instability trends provide useful guidance for heavy-duty applications, such as marine propulsion and utility-scale power generation. These trends help identify operating windows that mitigate large-amplitude thermoacoustic oscillations. To strengthen mechanistic interpretation and improve scalability to engine-relevant conditions, combining the present optical-diagnostics database with CFD simulations and flame transfer function (FTF) measurements may help elucidate the underlying combustion–acoustics coupling and quantify how XNH3 affects flame structure, instability pathways, and NOx formation, thereby supporting safer operation and informing NOx-mitigation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; methodology, J.M. and X.F.; software, J.M.; validation, J.M. and D.C.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, J.M.; resources, L.W., H.W. and B.W.; data curation, J.M., X.F., D.C., L.C., Y.S. and H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and X.F.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, L.W., H.W. and B.W.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, L.W., H.W. and B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ye Qisun Science Foundation of National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2241226).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Le Chang was employed by the company North Night Vision Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CH4 | Methane |

| CMOS | Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| FOV | Field of view |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| H2O | Water |

| ICMOS | Intensified complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| K | Cluster index obtained from the k-means classification |

| LCO | Limit-cycle oscillation |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NOX | Nitrogen oxides |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC | Principal component |

| QPO | Quasi-periodic oscillation |

| SC | stable combustion |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Valera-Medina, A.; Morris, S.; Runyon, J.; Pugh, D.G.; Marsh, R.; Beasley, P.; Hughes, T. Ammonia, methane and hydrogen for gas turbines. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Xiao, H.; Owen-Jones, M.; David, W.I.F.; Bowen, P.J. Ammonia for power. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 69, 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Costa, M.; Sun, Z.; He, Y.; Cen, K. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of laminar burning velocities of NH3/air, NH3/H2/air, NH3/CO/air and NH3/CH4/air premixed flames. Combust. Flame 2019, 206, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Howard, M.; Valera-Medina, A.; Dooley, S.; Bowen, P.J. Study on reduced chemical mechanisms of ammonia/methane combustion under gas turbine conditions. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 8701–8710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, H.; Ren, Z. Analysis of air-staged combustion of NH3/CH4 mixture with low NOx emission at gas turbine conditions in model combustors. Fuel 2019, 237, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, N.; Chen, M.; Zheng, H. Numerically study of CH4/NH3 combustion characteristics in an industrial gas turbine combustor based on a reduced mechanism. Fuel 2022, 327, 124897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariemma, G.B.; Sorrentino, G.; Ragucci, R.; de Joannon, M.; Sabia, P. Ammonia/methane combustion: Stability and NOx emissions. Combust. Flame 2022, 241, 112071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, S. Kinetics modeling of NOx emissions characteristics of a NH3/H2 fueled gas turbine combustor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 4526–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanizzi, M.; Capurso, T.; Filomeno, G.; Torresi, M.; Pascazio, G. Recent combustion strategies in gas turbines for propulsion and power generation toward a zero-emissions future: Fuels, burners, and combustion techniques. Energies 2021, 14, 6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyisse, E.F.; Nadimi, E.; Wu, D. Ammonia combustion: Internal combustion engines and gas turbines. Energies 2025, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shuai, R.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Qian, W.; Ferrante, A.; Dai, K. Combustor shape optimization and NO emission characteristics for premixed NH3-CH4 turbulent swirling flame towards sustainable combustion. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.F.; Rocha, R.C.; Oliveira, P.M.; Costa, M.; Bai, X.S. Experimental and kinetic modelling investigation on NO, CO and NH3 emissions from NH3/CH4/air premixed flames. Fuel 2019, 254, 115693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, A.A. An exploratory modelling study of chemiluminescence in ammonia-fuelled flames. Part 1. Combust. Flame 2023, 253, 112788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, W.P.; Lee, J.G.; Santavicca, D.A. Stability and emissions characteristics of a lean premixed gas turbine combustor. In Symposium (International) on Combustion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 26, pp. 2771–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Rao, Z.; Hu, H.; Yang, J.; Wen, H.; Wang, B. Experimental study on the thermoacoustic instability and bifurcation phenomenon of ammonia-methane premixed swirl-stabilized combustor. Combust. Flame 2025, 273, 113963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Albalawi, A.M.; Wang, S.; Roberts, W.L. Stability and characteristics of NH3/CH4/air flames in a combustor fired by a double swirl stabilized burner. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 4205–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nori, V.; Seitzman, J. Evaluation of chemiluminescence as a combustion diagnostic under varying operating conditions. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 7–10 January 2008; p. 953. [Google Scholar]

- Tinaut, F.V.; Reyes, M.; Giménez, B.; Pastor, J.V. Measurements of OH* and CH* chemiluminescence in premixed flames in a constant volume combustion bomb under autoignition conditions. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, M.J.; Fuller, T.L.; Sardeshmukh, S.; Anderson, W.E. Chemiluminescence as a diagnostic in studying combustion instability in a practical combustor. Combust. Flame 2020, 213, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.; Kempf, A.M. Computed tomography of chemiluminescence (CTC): High resolution and instantaneous 3-D measurements of a matrix burner. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Kojima, J.; Hashimoto, H. Local chemiluminescence spectra measurements in a high-pressure laminar methane/air premixed flame. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Khateeb, A.A.; Roberts, W.L.; Guiberti, T.F. Chemiluminescence signature of premixed ammonia-methane-air flames. Combust. Flame 2021, 231, 111508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Aldén, M.; Li, Z. Visible chemiluminescence of ammonia premixed flames and its application for flame diagnostics. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 4327–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Lu, G.; Li, X.; Yan, Y. Prediction of NOx emissions from a biomass fired combustion process based on flame radical imaging and deep learning techniques. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2016, 188, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviso, D.; Mendieta, M.; Molina, J.; Rolón, J.C. Flame imaging reconstruction method using high resolution spectral data of OH*, CH* and C2* radicals. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2017, 121, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, D.; Runyon, J.; Bowen, P.; Giles, A.; Valera-Medina, A.; Marsh, R.; Hewlett, S. An investigation of ammonia primary flame combustor concepts for emissions reduction with OH*, NH2* and NH* chemiluminescence at elevated conditions. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 6451–6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashruk, S.; Vigueras-Zuniga, M.O.; Tejeda-del Cueto, M.E.; Xiao, H.; Yu, C.; Maas, U.; Valera-Medina, A. Combustion features of CH4/NH3/H2 ternary blends. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30315–30327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. The explanation of certain acoustical phenomena. R. Inst. Proc. 1878, 8, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polifke, W. Combustion instabilities. In Advances in Aeroacoustics and Applications; Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics (VKI): Rhode-Saint-Gen‘ese, Belgium, 2004; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, J. Understanding the role of flow dynamics in thermoacoustic combustion instability. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 4583–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, M.; DeCusatis, C.; Enoch, J.; Lakshminarayanan, V.; Li, G.; Macdonald, C.; Van Stryland, E. Handbook of Optics, Volume II: Design, Fabrication and Testing, Sources and Detectors, Radiometry and Photometry; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gerke, U.; Steurs, K.; Rebecchi, P.; Boulouchos, K. Derivation of burning velocities of premixed hydrogen/air flames at engine-relevant conditions using a single-cylinder compression machine with optical access. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 2566–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschal, T.; Parajuli, P.; Turner, M.A.; Petersen, E.L.; Kulatilaka, W.D. High-speed OH* and CH* chemiluminescence imaging and OH planar laser-induced fluorescence (PLIF) in spherically expanding flames. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019; p. 0574. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.