Abstract

This paper proposes the development of an IEC 61850-compliant platform that is readily programmable and deployable for future digital twin applications. Given the compatibility between IEC-61850 and digital twin concepts, a focused case study was conducted involving the robust development of a Raspberry Pi platform with protection relay functionality using the open-source libIEC61850 library. Leveraging IEC-61850’s object-oriented data modelling, the relay can be represented by fully consistent virtual and physical models, providing an essential foundation for accurate digital twin instantiation. The relay implementation supports high-speed Sampled Value (SV) subscription, real-time RMS calculations, IEC Standard Inverse overcurrent trip behaviour according to IEC-60255, and Generic Object-Oriented Substation Event (GOOSE) publishing. Further integration includes setting group functionality for dynamic parameter switching, report control blocks for MMS client–server monitoring, and GOOSE subscription to simulate backup relay protection behaviour with peer trip messages. A staged development methodology was used to iteratively develop features from simple to complex. At the end of each stage, the functionality of the added features was verified before proceeding to the next stage. The integration of the Raspberry Pi into Curtin’s IEC = 61,850 digital substation was undertaken to verify interoperability between IEDs, a key outcome relevant to large-scale digital twin systems. The experimental results confirm GOOSE transmission times below 4 ms, tight adherence to trip-time curves, and performance under higher network traffic. Such measured RMS and trip-time errors fall well within industry and IEC limits, confirming the reliability of the relay logic. The takeaways from this case study establish a high-performing, standardised foundation for a digital twin system that requires fast, bidirectional communication between a virtual and a physical system.

1. Introduction

Modern power systems continue to advance and pursue the integration of distributed energy resources (DERs) to harness renewable energies at a large scale. However, this transition to smart grids poses many challenges driven by decarbonisation, decentralisation, and increasingly volatile loads [1]. The increasing penetration of wind, solar, and battery power leads to dynamic fluctuations in power generation, making predictions difficult and adversely affecting system frequencies and voltage stability [2,3]. Such dynamic fluctuations, alongside rising power demand, make it challenging for utilities to quickly and effectively balance large loads to match supply with demand [4,5]. With the increased complexity of modern power systems, the reliability of protection, control, and monitoring remains a constant struggle. Additionally, a more digitalised power system exposes itself to higher computational requirements [6] and greater data exchange [7,8].

The inherent complexity, dynamics, and challenges of the modern power system make Digital Twin (DT) technology fundamentally necessary [9]. DTs provide a digital representation of a physical system that can be synchronised in real-time [10]. With essentially a virtual replica of the system and live data ingestion and processing, the DT can provide crucial services, from supervisory to complete control of the physical system. This includes real-time parameter estimation [11,12], monitoring [13,14], health assessment for power electronic converters [15], and risk assessment [16].

DTs offer a significant improvement over traditional modelling methods, enabling real-time monitoring of system behaviour and allowing operators to identify potential problems and stability issues before they occur. Since DTs are logically detached from the physical system, they can simulate and test complex nonlinear scenarios virtually to find optimal control settings for an extensive power system without affecting real-time operation [4]. This is particularly necessary to forecast the intermittent behaviour of renewable energy sources. For cybersecurity, anomaly detection and cyber-attack simulations can also be performed on the DT to identify potential breaches [17,18,19].

Furthermore, the grid structure of the new energy power system is becoming increasingly complex, with nonlinear characteristics. Artificial intelligence algorithms provide critical support for addressing such challenges. A deep review of how digital twins, together with artificial intelligence, are being applied across power systems to enhance monitoring, prediction, and cyber-resilience has been conducted [20,21]. A real-time digital twin reference model has been proposed to localize cyber-attacks in distribution systems [22], and an IoT-enabled digital twin for networked microgrids has been applied to improve resilience and enable rapid responses against cyber-attacks [23].

In recent years, DT technology has promising potential across industries; however, its current deployment in the evolving energy sector remains constrained. The deployment of accurate and reliable DT models for larger power systems is a computationally intensive feat. Most importantly, digital twin is highly important in power systems because it is difficult, costly, and sometimes unsafe to perform repeated overcurrent protection tests on real physical power equipment. With a digital twin, we can run a large number of tests under different fault conditions in a controllable environment and continuously collect high-quality data for analysis. This becomes even more critical when renewable energy sources are integrated into the grid, as the system dynamics become more complex and traditional protection settings may no longer remain optimal.

Without a digital twin, power system operators can only rely on limited on-site measurements and historical operational data, which often leads to an inadequate understanding of potential risks. Once an unexpected fault occurs, troubleshooting the system is time-consuming and labour-intensive. Moreover, optimising protection strategies without a digital twin relies heavily on empirical judgments, making it hard to adapt to the real-time changes in system operating conditions, especially when renewable energy output fluctuates sharply.

For a reliable solution, further research is still required to manage measurement and model errors and to determine how uncertainty propagates throughout the entire system life cycle. There is also a lack of focus on the security of DTs and the vulnerabilities they are exposed to, despite being positioned to be an extra layer of security. Although application to large-scale power systems remains a hurdle, DT observes success and promising results when applied to microgrids [16]. Smaller systems are generally less complex and can be treated as feasibility testing grounds. The focus of this paper is on the application of DT principles to smaller systems and how the IEC-61850 communication standard can be leveraged to bolster DT architecture. To be effective in practice, DTs require bidirectional, fast, and reliable data exchange. IEC-61850 becomes a key enabler of these requirements by providing standardisation and interoperability across devices.

IEC-61850 provides a standardised data model for Ethernet-based communication services to enable interoperability among devices, independent of their make or model [24,25]. Unlike previous communication infrastructures, IEC-61850 defines object-oriented Logical Devices, supports critical event-based messaging through Generic Object-Oriented Substation Events (GOOSEs), facilitates Sampled Value (SV) streams of analogue signals, and enables a remote connection and access to Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs) for reporting or configuration through Manufacturing Message Specification (MMS). Altogether, this enables IEDs to monitor, interact with, respond to, and report critical events from the substation with minimal latency and minimal engineering configuration. IEC-61850’s Substation Configuration Language (SCL) provides this formal method of representing and exchanging system configuration data between devices. SCL not only describes IEDs but also the substation structure, communication network topology, and mappings of physical equipment to logical functions. With the Substation Configuration Description (SCD) file, which describes a complete system and the dedicated Logical Nodes (LN) for DERs, IEC-61850 becomes particularly attractive for creating microgrid DT systems. This has taken away the friction of implementing a virtual twin for an existing power system.

In DT development, IEC-61850 can act as a core data structure and communication link. IEC-61850 communication, ideal for power management, protection, and control, is highly compatible with DT principles. This paper highlights this compatibility by focusing on a small-scale case study of a Raspberry Pi as a platform to run a DT node. This case study aims to develop a fully programmable and functional relay package that can be deployed as a DT node for future DT applications. The relay was designed from the ground up to have full control and oversight over its behaviour. This way, both virtual and physical nodes can be made identical, as is expected in a DT system. Testing the virtual and physical nodes as a DT system is outside the scope of this paper, as the focus is on developing the infrastructure. With Raspberry Pi 5 as the platform, the open-source libIEC61850 library provided the entire protocol stack for SV, GOOSE, and MMS services and the publisher–subscriber and client–server communication models. The objective was to implement and functionally test the final IED, ensuring it is operational and standards-compliant, with features including SV subscription, real-time RMS calculation, inverse-time overcurrent trip logic, and GOOSE trip message transmission to the network. Additional features include backup relaying via GOOSE messages from downstream relays, full setting-group control, MMS reporting, and compliance with IEC-60255-151 trip–timing accuracy. The work in this paper includes the setup and implementation of the IEC-61850 data model for a relay node running on a Raspberry Pi, which was used to demonstrate the virtualisation process, the operational likeness to the physical system, and the performance of a virtual relay.

Our digital twin relay was developed based on the IEC-61850 communication protocol and is designed to exchange real-time information with a physical protection relay. Since Curtin University has an established IEC-61850 laboratory, we had access to a complete testing platform and a standard-compliant data modelling environment. This allowed our digital twin to follow the IEC-61850 logical node and data object structure and validate its performance through practical communication tests, ensuring full compliance with the defined logical nodes and data objects.

2. Methodology

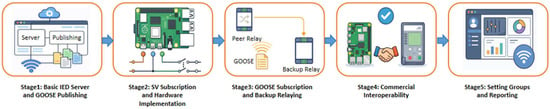

If the physical node does not yet exist in the DT system, the virtual relay node can first be created, tested, and validated before commissioning the physical node [26]. The implementation in this paper follows this order. To create the fully featured DT protection relay node, the implementation process spanned five stages. The purpose of this approach was to iteratively build and verify functionality for every IEC-61850 feature implemented on the relay. This ensured that at the end of each stage, the implemented feature was operational and testable. From the first stage of establishing a basic virtual IED, each subsequent stage and feature was stacked on top of the others to arrive at a highly capable IEC-61850 protection relay. The thorough implementation of IEC-61850 was crucial to demonstrate how the standard behaves as a vehicle for the seamless development of a DT node and system. The flowchart in Figure 1 outlines the scheme’s various stages. Our method contributes a practical, step-by-step workflow for building a fully featured IEC-61850 digital twin (DT) protection relay, starting from a virtual relay node and gradually moving toward deployable physical implementation. By validating IEC-61850 functions step-by-step (SV, GOOSE, MMS, and interoperability), each feature was tested and confirmed at every stage. This provides a framework for developing reliable and interoperable DT protection nodes before physical commissioning.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the methodology.

Stage 1: Basic IED Server and GOOSE Publishing.

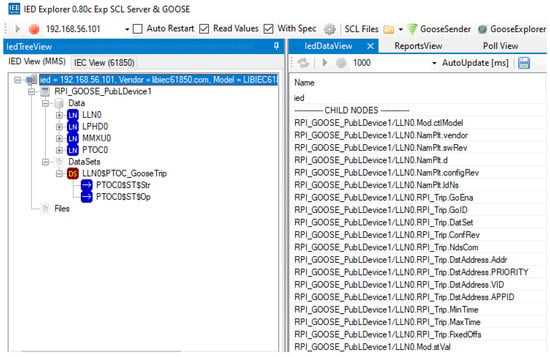

This stage involved validating the libIEC61850 library on a Linux Virtual Machine (VM) to replicate the Raspberry Pi’s environment as closely as possible. The Debian-based Kali VM was run using Oracle VirtualBox, which provided a Virtual Ethernet interface for testing the library. The heart of the IED, the IED Configuration Description (ICD), was developed in this stage to define the device’s logical model. Basic client–server functionality was tested with IEDExplorer across the Virtual Ethernet network, which confirmed the validity of the server program, the ICD file, and GOOSE publishing. Figure 2 shows the verification of the ICD file using IEDExplorer.

Figure 2.

IEDExplorer: Connecting to the Simple Server. (LN denotes Logical Node, DS denotes Dataset, denotes a reference address.).

Stage 2: SV Subscription and Hardware Implementation.

Due to the limited licensing of the Omicron Test Universe SV simulation module, an SV publisher was instead developed to simulate three-phase balanced current outputs. To receive the published SV, an SV subscriber was developed and integrated into the server code to handle the inputs. The program parses the received SV current samples and performs real-time RMS calculations using a sliding window method. These RMS values are fed into the overcurrent logic using the IEC Standard Inverse curve, and a decision to trip sends the GOOSE trip message to the network. With the preliminary verification of this logic, the programs were migrated to the Raspberry Pi 5 for validation and functional testing.

Stage 3: GOOSE Subscription and Backup Relaying.

Stage 2 presented a Raspberry Pi device that could subscribe to SV, operate on overcurrent trip, and publish GOOSE trip messages. This establishes the node’s fundamental functionality. Further exploring the IEC-61850 standard and protection principles, backup relaying was implemented via GOOSE subscriptions to peer relays.

Stage 4: Commercial Interoperability.

IEC-61850 boasts interoperability with multi-vendor relay systems. This stage explored IEC-61850 communication between the Raspberry Pi and an ABB REF615 relay to explore the interoperability of the Raspberry Pi IED. As a byproduct of the limitations of ABB’s PCM600 IED configuration software in importing the independently generated ICD file for the Raspberry Pi, ABB relay simulation on the Raspberry Pi was investigated and successfully achieved. This allowed the Raspberry Pi to communicate with the target ABB relay as an ‘ABB’ relay itself. We found that the original ICD file is compatible with Schneider CET850 software and relays, but not with ABB. However, testing and validation were performed using the ABB relay due to familiarity with its software. Using IEDScout [27], the GOOSE sniffer was used to observe the network when both devices were tested as primary and backup relays between each other. The success of this stage highlights the interoperability of the programmed DT node with a commercial relay and the ability to simulate third-party ICD files on any device, a key indication of how a DT system can seamlessly operate under the IEC-61850 standard.

Stage 5: Setting Groups and Reporting.

In this final stage, MMS-based services of setting-group and reporting functions were implemented to approach a more complete IED solution. A client–server connection to the Raspberry Pi enabled a client, such as IEDScout, to switch between or edit active setting groups, or simply monitor the reported RMS values calculated from the SV currents. Editing the Raspberry Pi’s overcurrent trip curve parameters, such as the Time Multiplier Setting (TMS), current pickup, and IEC curve type, enabled flexibility to change the relay’s behaviour without recompiling the program.

This staged methodology ensured that all features from the SV, GOOSE, and MMS services were progressively validated. This reduced the complexity of integrating all functions at once and set clear developmental milestones for the project.

3. Implementation

The philosophy behind implementing the DT relay node was to replicate key behaviours of modern IEDs: real-time current input and measurement, inverse-time overcurrent logic, high-speed GOOSE publishing, GOOSE subscription for backup relaying, and flexible operation through setting groups. All features were implemented using the C programming language, the libIEC61850 source code, and the Raspberry Pi 5’s processing and networking capabilities. As the product of this implementation is a Raspberry Pi Overcurrent Relay, it will be henceforth referred to as RPI-OCR. The following discussion follows the chronological order and the thought process during implementation.

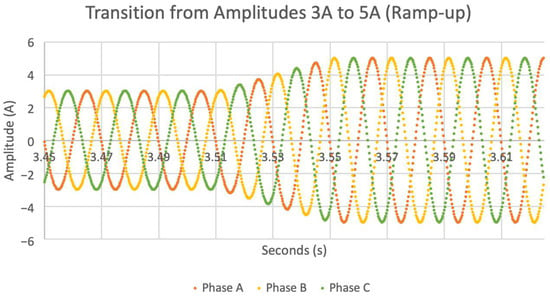

To replicate the Current Transformer (CT), Merging Unit (MU), and IED relationship, the IED must be able to receive the published SV currents from the MU and operate on it. The SV currents come as a digitised analogue signal; therefore, the RPI-OCR must perform the RMS calculations upon the arrival of SV messages. See Figure 3 for the output of the produced SV publisher’s current samples, along with its ramp-up feature between two set currents. The real-time RMS calculator is the RPI-OCR’s core measurement function. The RPI-OCR is configured as an SV subscriber, with a callback handler that extracts current samples and stores them in a circular buffer. The circular buffer stores up to 80 samples (one cycle) of the received signal, with which an RMS value is computed using the square root of the average power sum formula. At the system level, the RPI-OCR program runs two threads, one for the main program and another for listening to SV messages. Since variables such as RMS values are shared between the two threads, mutex locks were implemented to prevent race conditions when accessing them.

Figure 3.

Output of the SV Currents Publisher Program to simulate MU.

With the receipt of the RMS values, the RPI-OCR program could proceed to the overcurrent logic. The logic follows the IEC-60255 Standard Inverse Curve, which is described by the equation below [28]:

where I and IS indicate the input RMS current and the current pickup, respectively. Note that I is continuously checked against IS, and I/IS represents the pickup multiple. Once the pickup multiple exceeds 1, the time-to-trip is calculated to initiate a delay timer. Upon reaching the delay time, the relay operates or asserts the trip condition.

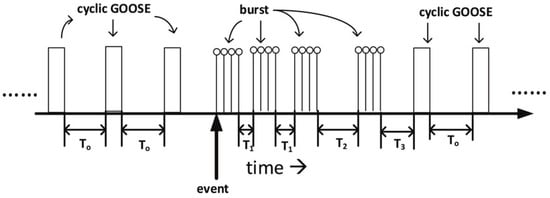

To broadcast the trip, a GOOSE dataset had to be sent, with data attributes PTOC.Str and PTOC.Op both set to True. The Str or Start returns True when a fault condition is detected (before the time delay), and Op or Operate returns True when the relay trips (after the time delay). Since the GOOSE service lacks acknowledgements, GOOSE messages must follow a cyclic–burst–cyclic retransmission scheme in case packets are dropped or lost, as recommended by IEC-61850-8-1. In this implementation, the GOOSE messages were retransmitted in exponentially increasing intervals from 4 ms to 1024 ms when sending trip signals, and a cyclic interval of 1000 ms before or after the trip to maintain status updates to relays subscribing to the RPI-OCR. This behaviour was confirmed by collecting timestamped packets using IEDScout, Wireshark, and RPI-OCR terminal outputs to ensure adherence to the design. This retransmission scheme is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

GOOSE Retransmission Scheme [26].

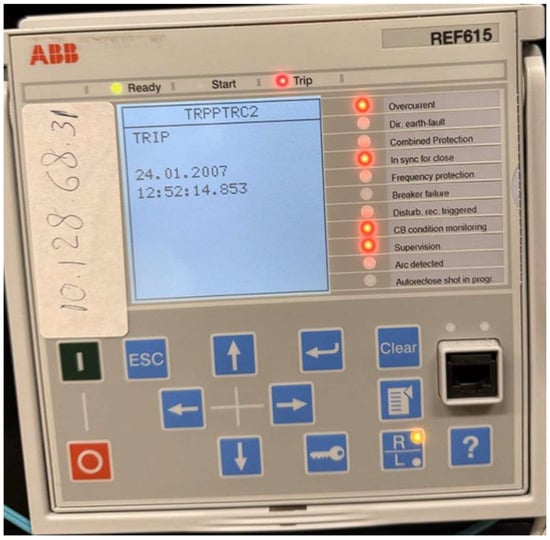

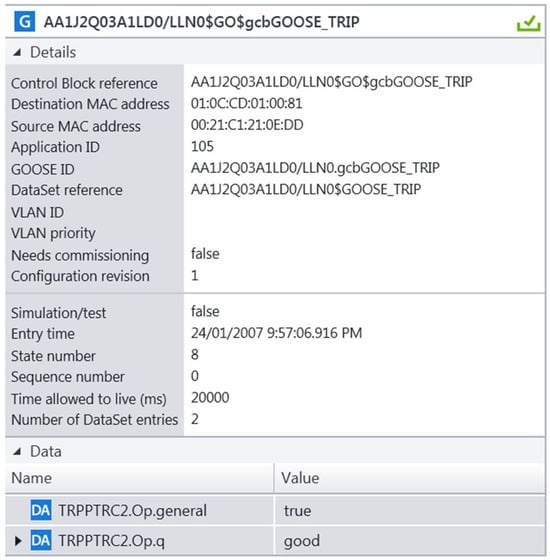

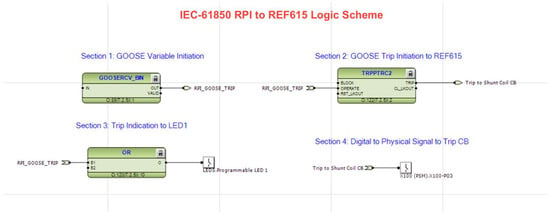

The RPI-OCR was also developed with a GOOSE subscriber functionality that listens for external trip signals from peer relays in the network. To validate the RPI-OCR’s backup relay function, the ABB REF615 relay was configured to publish its own GOOSE dataset to which the RPI-OCR would subscribe. As the RPI-OCR operates, a separate GOOSE thread, much like the SV thread, listens for GOOSE messages to which the RPI-OCR is subscribed. Once it receives a GOOSE message, the callback handler operates on the received dataset and reads whether the Op attribute is True, indicating the ABB relay had tripped. When the attribute reads True, the RPI-OCR is programmed to trip as well. Functional testing was conducted via simulations and in Curtin’s IEC-61850 digital substation, a network of IEC-61850 devices. After sending trips from the ABB relay, and subsequently from the RPI-OCR, both devices were able to subscribe to the published trip messages and trip themselves, confirming the publisher–subscriber configuration and the implementation’s interoperability. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the response of the ABB relay after receiving a trip message from the RPI-OCR. Figure 7 describes the logic functions that enable the responses shown in the previous figures.

Figure 5.

The ABB REF615 TRPPTRC2 trip after receiving the RPI-OCR trip.

Figure 6.

The IEDScout received the GOOSE packet from the ABB relay. (DA denotes Data Attribute.).

Figure 7.

The Logic Scheme Produced on PCM600 in the ABB environment.

As an extension of the implementation, the RPI was also investigated as a device for simulating relays using only an ICD or CID file. To properly operate under a third-party ICD/CID file, the RPI server program must be tweaked to match the data references to access and operate the third-party data model. The libIEC61850 library on the RPI can then behave like IEDScout or other engineering tools that enable IED simulation, such as Triangle Microworks Test Suit Pro. What sets the RPI apart is that any logic can be programmed for testing or prototyping.

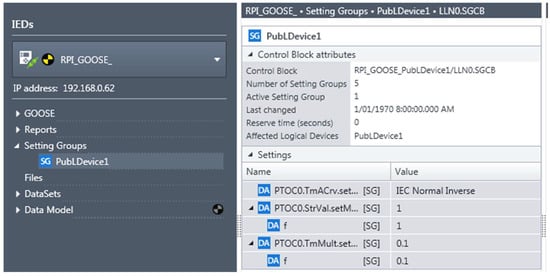

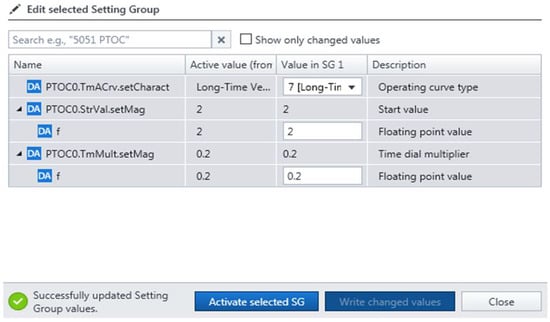

Expanding upon SV and GOOSE, setting groups were implemented. To enable a client to configure the RPI-OCR, the Setting Group Control Block (SGCB) must be initialised in the ICD file. The remaining setting group functions are handled internally in the RPI-OCR program. Setting groups are explored on both the client and server sides. The handling of SGCB data change requests is implemented on the server side. This handling includes functions loadActiveSgValues() and loadEditSgValues() from the libIEC61850 library, which swap and edit data attributes of the setting group (SG) and setting group editable (SE) functional constraints. Writing to ActSG, EditSG, and CnfEdit must be performed to trigger these handlers [29]. Figure 8 shows the SGCB of the RPI-OCR, confirming that it was configured correctly. On the client side, a program was developed that can connect to a target IED via its IP address on the network and edit/change setting groups. For example, the setting group client program could change the Operating Delay Time (OpDlTmms) of the ABB REF615 relay and switch from setting groups 1–6 when connected across the network.

Figure 8.

IEDScout Client Connection for Setting Group Function. (SG denotes Setting Group, DA denotes Data Attribute.).

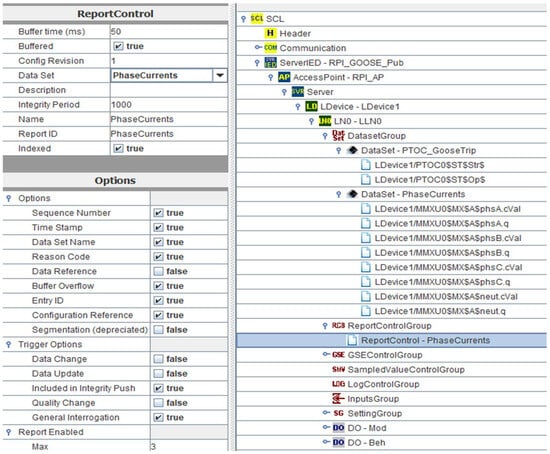

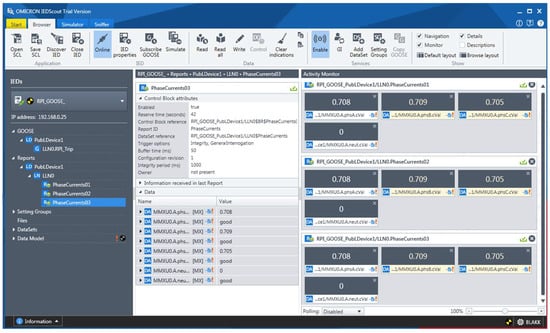

To wrap up the implementation, MMS reporting was implemented by setting up Report Control Blocks (RCBs) on the ICD file. ICD Designer was used once again to create datasets of data attributes for reporting and to link these datasets to the RCB. The reporting parameters, such as the buffer time, maximum number of reports, and trigger options, are defined in ICD Designer in Figure 9. For the RPI-OCR in Figure 10, the reporting dataset consisted of the three-phase RMS current values and quality bit under the measurement logical node (MMXU). This allows external clients, such as IEDScout, to receive data updates without manual polling or the need to define internal logic.

Figure 9.

ICD Designer to create reporting datasets.

Figure 10.

IEDScout Monitoring Reporting Blocks from RPI-OCR.

In all, these fundamental components formed the core of the DT protection relay node, not only providing protection functions but also demonstrating compliance with IEC-61850 services such as GOOSE, SV, and MMS.

4. Results and Future Application

The performance of the RPI-OCR was scrutinised under three key metrics: RMS calculation accuracy, trip timing accuracy, and GOOSE transmission time delay. These were selected to meet the minimum verification requirements for a protection relay in accordance with IEC-60255-151 and IEC-61850-8-1. Favourable results on these metrics indicate that implementing the IEC-61850 standard is highly capable of modelling a DT node for DT systems.

The internal RMS calculator demonstrated high accuracy, with a worst-case calculation error falling well below the accuracy requirements of industrial relays. When compared directly with the accuracy requirements of ABB REF615’s PHHPTOC three-phase high-set overcurrent function, for current ranges of 0.1–10× pickup current, accuracy should be 1.5%, and for current ranges of 10–40× pickup current, accuracy should be 5% [30]. Note that in Table 1 the pickup current is 1A; therefore, the current multiple is the RMS value itself. The error at ~10× pickup current (15A current amplitude) was at most 0.3172%, and at ~20×, the maximum error was observed at 0.5145%. For the two current ranges, the RPI-OCR performed with accuracy comparable to an ABB relay, indicating it meets or exceeds industry standards for RMS computations.

Table 1.

RMS Calculation Errors.

Trip-time accuracies were measured against the IEC Standard Curve, with the trip calculated using the maximum RMS current observed across the three phases at any one time. The error was calculated as shown in Table 2, and the largest average error observed occurred at the fastest trip time, at 0.2832%. Not included in the table, one sample out of 135 across all testing had an error of 0.472% at a trip time of 0.2256 s. For TMS values of 0.3 and 0.5, which produce longer trip-time durations, the errors were even lower.

Table 2.

Average Trip-Time Error for TMS = 0.1.

According to the Class 5 timing accuracy defined in IEC-60255-151 Clause 5.3, the accuracy requirements for pickup multiples 2–5, 5–10, and 10+ are 12.5%, 7.5%, and 5%, respectively. The results of the RPI-OCR at TMS = 0.1 confirm that the implementation is compliant with the accuracy requirements of the standard.

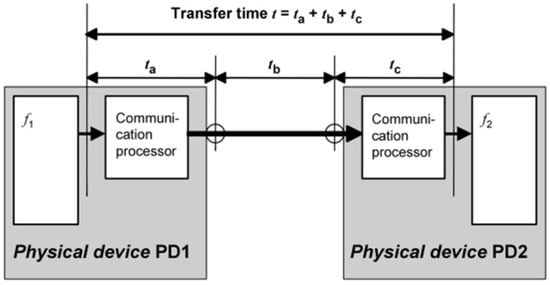

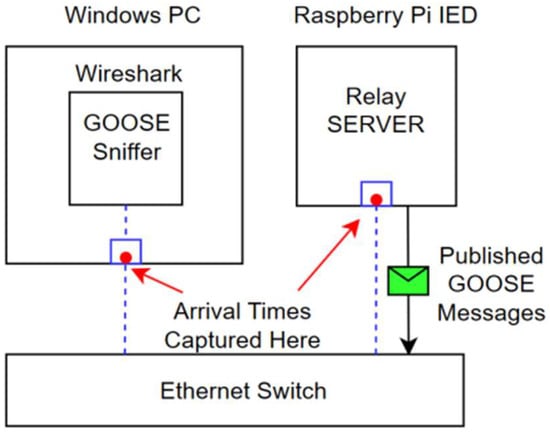

The GOOSE transmission delay was tested under three network conditions: GOOSE-only traffic, SV and GOOSE traffic, and SV, GOOSE, and MMS traffic. The average GOOSE transmission times (recorded over a minute) were 361 µs, 201 µs, and 1.912 ms, respectively, which all remained within the 4 ms requirement, according to IEC-61850-8-1. As part of this testing, the RPI-OCR and the Windows PC were time-synchronised under Network Time Protocol (NTP) to maintain sub-millisecond measurement resolution. It was observed that fluctuations occurred in time synchronisation, causing a positive or negative offset between the two devices at magnitudes of around ±100 µs, which may cause measurement inconsistencies. Nonetheless, a ±100 µs variation in the averaged results would keep the transmission times within the 4 ms requirement, suggesting it is fast enough for practical application in a substation. Note that according to IEC-61850-8-1, the GOOSE transmission time, also known as the transfer time, is the time between two application layers, as seen in Figure 11. Considering this, the developed experimental setup is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

GOOSE Transfer Time Breakdown [18].

Figure 12.

Experimental Test Setup for Measuring GOOSE Transmission. (The red dots highlight that the timestamps are being captured at the network adapters of each device.).

As part of the overall functional testing, the RPI-OCR was also verified for GOOSE subscription and setting-group changes. When the RPI-OCR is configured to receive trip signals from the ABB REF615, the relay reliably operates as a backup relay during fault conditions. It has a measured GOOSE reception-to-response delay of around 3.26 ms, which included processing overhead on top of the GOOSE transmission time. For the reverse, the ABB relay was also successfully tripped by the RPI-OCR’s trip signal. Both tests were conducted in Curtin’s IEC-61850 network, validating interoperability across devices, regardless of make or model.

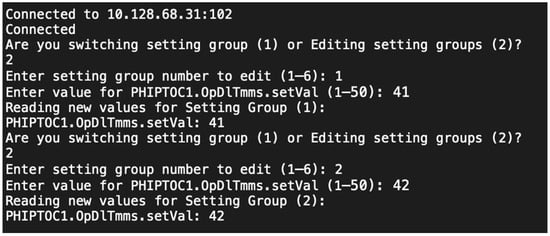

In testing setting groups, both server- and client-side functionalities were tested via either IEDScout’s client connection and IED simulation or directly with the ABB relay. Through testing, the RPI-OCR was able to accept and handle edit operations (EditSG), confirm edits (CnfEdit), and perform group switching (ActSG) (see Figure 13). A client-side program was also created to switch between all six setting groups of the ABB relay and to allow editing of the OpDlTmms data attribute. Live changes were monitored through IEDScout client connection to the ABB relay, as well as data model read outputs on the terminal from the client-side program, such as in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

RPI-OCR Server SGCB accessed through IEDScout. (DA denotes Data Attribute).

Figure 14.

SG Client Program for changing ABB REF615 settings.

Altogether, the results validate that the RPI-OCR implementation satisfies the measurement and timing accuracy requirements for an overcurrent protection relay under the IEC-61850 and IEC-60255-151 standards.

The success of this implementation provides a viable physical foundation for the DT of a protection relay. Through testing and validation, the developed system was already able to perform core DT services, including data acquisition, fast reaction time to network disturbances, and real-time network interaction. This paves the way for the next step in enabling bidirectional coordination between the DT and the physical power system. With the foundation of a programmable DT system, the natural progression is to integrate artificial intelligence (AI). Modern power systems are evolving rapidly, demanding new technologies such as adaptive protection using machine learning (ML) algorithms, system-wide optimisation and coordination, predictive and preventive maintenance of assets, and in-situ fault and disturbance simulation for refined control logic. Combining this IEC-61850 and DT foundation with this new technology is well poised to support a new generation of smart, adaptive, and decentralised power grids.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented the development of an IEC-61850-compliant relay implemented on a Raspberry Pi 5 using the open-source libIEC61850 library, which served as a programmable DT system suitable for future complex computational applications. The staged development approach established a fully functional IED that supports SV subscription, RMS calculation, IEC-60255 inverse-time trip behaviour, and GOOSE publishing. Additional features included GOOSE subscription for backup relaying, setting-group editing and switching, and reporting through MMS client–server communication. This resulted in a complete relay implementation that is interoperable with commercial vendors in a digital substation network.

Performance testing demonstrated valid protection logic. The RMS accuracies obtained fell below 0.5145% across all tested pickup multiples. Trip-time accuracies had a single sample error, reaching 0.472% across all samples; the average error at a pickup multiple of ~20× was only 0.2832% at TMS = 0.1. Samples with lower pickup multiples and higher TMS values fell further below this error value. GOOSE transmission times under network stress averaged 1.91 ms across all samples, remaining within the 4 ms requirement of IEC-61850-8-1. Additionally, interoperability was tested against an ABB REF615 relay, which included primary and backup relaying with GOOSE trip signals and setting-group editing through client connections. This test provided significant evidence that this open-source programmable platform has few compromises and firmly cements its place in future industrial-grade DT applications.

The logical next step for this research is to apply the concepts from this case study and build a small IEC-61850 DT system for further study. A virtual and physical system should be able to run in parallel and allow bidirectional communication and data exchange between them. Fault injection and system behaviour can be investigated as well. Further development of this communication scheme using IEC-61850 would be required and not necessarily limited to the Raspberry Pi. There are many more features that can be implemented using the libIEC61850 library, which requires deeper understanding of the source code and the IEC-61850 standard. This can be leveraged further to expand implementation on more computationally capable devices. The client–server communication afforded by the standard may allow the desired platform to control a network of relays to behave in accordance with network conditions. The open-source library offers the flexibility and programmability to configure, based on programmed logic, the protection and control of a power network. It can be positioned as the brain of the digital twin, receiving network conditions, processing them, and broadcasting control signals. This would enable adaptive substation automation and provide an avenue for integrating ML. In relation to adaptive behaviour, Distributed Energy Resource (DER) control capabilities should be explored. The logical nodes for DER devices, such as photovoltaic systems, battery energy storage, and fuel cells, are defined in IEC-61850-7-420. The success of this project supports the potential for a programmable DT equipped with the IEC-61850 standard to pave the way for AI to penetrate deeper into the energy industry.

In future work, we will investigate multi-node communication. The challenge is that, as the number of nodes increases, the requirements for hardware compatibility and system resources get much more demanding, including computational capacity and time-synchronization performance. This challenge will be addressed in our ongoing multi-node experiments and future system-level development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P., Y.L. and Y.Y.; methodology, Y.L., H.L. and Y.Y.; software, H.L. and Y.L.; validation, E.P. and S.R.; formal analysis, Y.L., H.L. and Y.Y.; investigation, H.L. and S.R.; data curation, Y.L., H.L. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L., H.L. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and S.R.; visualization, H.L. and Y.Y.; supervision, Y.L., H.L. and Y.Y.; project administration, E.P., S.R. and Y.Y.; funding acquisition, E.P. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| SV | Sampled Value |

| GOOSE | Generic Object-Oriented Substation Event |

| DT | Digital Twin |

References

- Yassin, M.A.M.; Shrestha, A.; Rabie, S. Digital twin in power system research and development: Principle, scope, and challenges. Energy Rev. 2023, 2, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, A.; Andresen, B. Power Quality Analysis and Improvement of Power-to-X Plants Using Digital Twins: A Practical Application in Denmark. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, Z.; Pashajavid, E.; Rajakaruna, S. Optimal Sizing and Economic Analysis of Community Battery Systems Considering Sensitivity and Uncertainty Factors. Energies 2024, 17, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifat, M.M.H.; Das, S.K. Proactive and Reactive Maintenance Strategies for Self-Healing Digital Twin Islanded Microgrids Using Fuzzy Logic Controllers and Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Azim, M.I.; Peters, J.; Pashajavid, E. Expediting battery investment returns for residential customers utilising spot price-aware local energy exchanges. Energy 2024, 306, 132458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Chen, T.; Karimi, M. A Review on Digital Twin Technology in Smart Grid, Transportation System and Smart City: Challenges and Future. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 17471–17484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomerdijk, W.; Palensky, P.; AlSkaif, T.; Vergara, P.P. On future power system digital twins: A vision towards a standard architecture. Digit. Twins Appl. 2024, 1, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heluany, J.; Gkioulos, V. A review on digital twins for power generation and distribution. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 23, 1171–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraño-Vargas, F.; Konstantinou, G. Modular Design and Real-Time Simulators Toward Power System Digital Twins Implementation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, N. Digital Twin Formation and Real-Time Parameter Estimation for Consumer-Integrated Grid-Tied PV Systems Using IFO-GDF and Coulomb-EFO. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7813–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrisov, I.; Veretennikov, I.; Ibanez, F.M. Dynamic State Estimation in Power Electronics-Dominated Grids Using a Digital Twin Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 53938–53948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, N. State-Space Driven Digital Twin for Condition Monitoring and Predictive Health Assessment in Grid-Integrated Power Converter System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2025, 3, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Li, Z.; Zha, X. A Digital Twin System of Capacitive DC Bank Using Rogowski Coil to Monitor Individual Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 9251–9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, N. Real-Time Digital Twin for Multiparameter Estimation and Health Assessment in a Two-Stage Grid-Connected Power Electronic Converter. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9009108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-Y.; Apolinario, G.F.D. Ancillary Services and Risk Assessment of Networked Microgrids Using Digital Twin. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 4542–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nand, K.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J. A Comprehensive Survey on the Usage of Machine Learning to Detect False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, R. Detection-Triggered Recursive Impact Mitigation Against Secondary False Data Injection Attacks in Cyber-Physical Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 1744–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.S.; Giraldo, J.A.; Parvania, M. Attack Detection in Power Distribution Systems Using a Cyber-Physical Real-Time Reference Model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani-Sane, G.; Azad, S.; Ameli, M.T.; Haghani, S. The Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twin in Power Systems: An In-Depth Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 108573–108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Arraño-Vargas, F.; Konstantinou, G. Artificial intelligence and digital twins in power systems: Trends, synergies and opportunities. Digit. Twin 2023, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.S.; Giraldo, J.; Parvania, M. Real-Time Cyber Attack Localization in Distribution Systems Using Digital Twin Reference Model. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 3238–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Faddel, S.; Youssef, T.; Mohammed, O.A. On the Implementation of IoT-Based Digital Twin for Networked Microgrids Resiliency Against Cyber Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 5138–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Shi, D.; Wang, P. IEC 61850-Based Information Model and Configuration Description of Communication Network in Substation Automation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2014, 29, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, G.; Machado, J.; Perondi, E.; Vyatkin, V. A Formal Methodology for Accomplishing IEC 61850 Real-Time Communication Requirements. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 6582–6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, M.A.; Hussain, S.; Roostaee, S.; Ali, I.; Mehfuz, S.; Thomas, M. Performance Evaluation of IEC 61850 GOOSE based inter substation communication for accelerated distance protection scheme. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 4089–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEDScout—IEC 61850 Client and IED Testing Tool; OMICRON: Houston, TX, USA, 2024.

- IEC 60255-151:2009; Measuring Relays and Protection Equipment—Part 151: Functional Requirements for over/Under Current Protection. International Electrotechnical: London, UK, 2009.

- Schossig, T. Application of Settings and Setting Groups in IEC 61850. J. Eng. 2018, 2018, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABB. Technical Manual—Protection and Control RELAY: REF615; ABB: Zürich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.