System Synchronization Based on Complex Frequency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Complex Frequency Synchronization Principle

2.1. Complex Frequency

2.2. Fundamental Principle of Complex Frequency Synchronization

2.3. Scope of Synchronization Criteria

2.3.1. Application Scenarios of Complex Frequency Synchronization

- Systems with high penetration of inverter-based resources. In such systems, rotational stability is directly determined by electrical and control dynamics, and the inertial response of conventional synchronous machines is effectively replaced by virtual inertia. At the same time, voltage-side dynamics have a pronounced impact on the transient response when the penetration level of grid-following (GFL) converters exceeds about 60% voltage dynamics or excitation-related dynamics tend to emerge or deteriorate before frequency synchronization issues become evident [20]. Hence, it is necessary to monitor both and in order to detect instability risks at an early stage.

- Operating conditions involving phase-locked loops (PLLs), such as grid connection or mode switching [21]. When responding to faults, switching events, or other disturbances, PLLs are prone to abrupt frequency changes or oscillations. A complex frequency can provide a smoother and more reliable frequency indicator, and the inclusion of the voltage magnitude rate helps mitigate the signal distortion associated with using alone.

- Distribution networks with low ratios, or systems whose electrical dynamics have time scales comparable to those of the control loops. When line resistance cannot be neglected, the coupling between active power/frequency and reactive power/voltage is significantly strengthened (with approximate relationships such as , so traditional observations based solely on will overlook the influence of voltage dynamics on frequency behavior [14]. In addition, in low-inertia systems, the time scales of line dynamics and AC filter control dynamics can be comparable, making the conventional assumption of neglecting network dynamics no longer valid.

- Islanded or weakly coupled operating areas. During transients, significant discrepancies may arise among the nodal frequencies [22], so relying solely on a single measurement point or on the system center of inertia (COI) frequency cannot accurately assess the synchronization status. In this case, employing a regionally consistent complex frequency variable can enhance the overall coordination of the system and improve the robustness of stability and synchronization criteria.

- Control scenarios with coupled frequency and voltage oscillations. The complex frequency synchronization framework indicates that, even in lossy networks, frequency oscillations can be suppressed through coordinated active and reactive power control. Simulation studies further show that frequency regulation based on the combined use of , , and achieves a better performance than schemes relying solely on active power [23]. In essence, this requires treating and as joint control objectives.

2.3.2. Application Scenarios of Conventional Synchronization

- Systems in which synchronous generators (SGs) dominate or the voltage stiffness is relatively high [24]. When the system is dominated by SGs and the automatic voltage regulator (AVR) together with the power system stabilizer (PSS) can effectively maintain the bus voltage magnitude nearly constant, one has . In this situation, system dynamics are mainly reflected in the frequency channel, and complex frequency synchronization naturally degenerates into conventional angular frequency synchronization. Existing work [21] also indicates that, as long as the system is able to preserve a firm voltage profile, stability issues arise primarily on the frequency side; only when the share of converter-interfaced generation (CIG) keeps increasing and the firm voltage condition is weakened do both state variables become necessary.

- Systems dominated by grid-forming converters (GFMs) that do not rely on phase-locked loops (PLLs) for synchronization. In GFM-based architectures providing system-wide voltage and frequency support, the frequency at the point of common coupling is prescribed by internal control rather than obtained via PLL tracking. This yields a frequency signal that is largely immune to grid disturbances. If, in addition, the AC system experiences only small variations in voltage magnitude, can be regarded as a reliable indicator of the synchronization state [25].

3. Design of Robustness Indices for System Synchronization

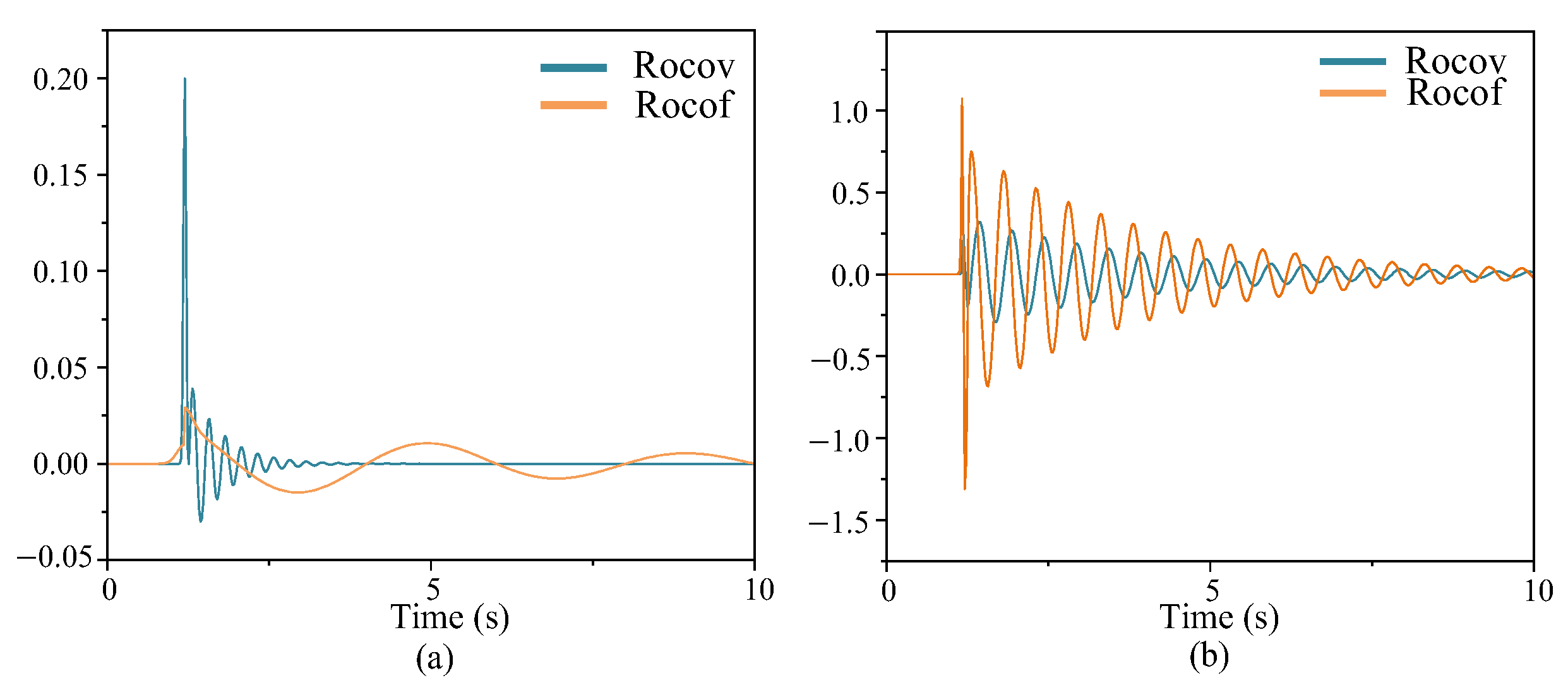

3.1. Oscillation Decay Rate

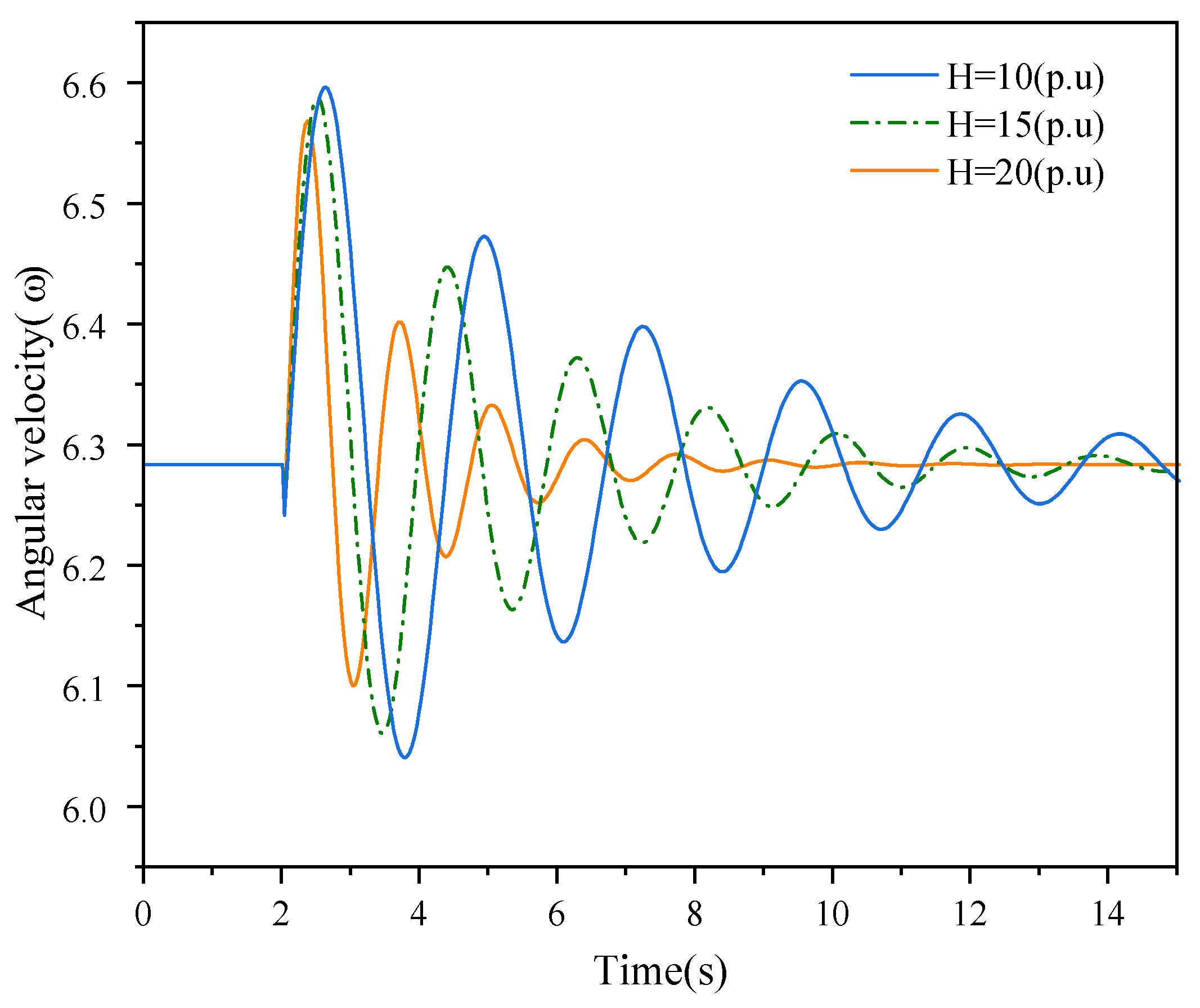

3.2. Complex Inertia

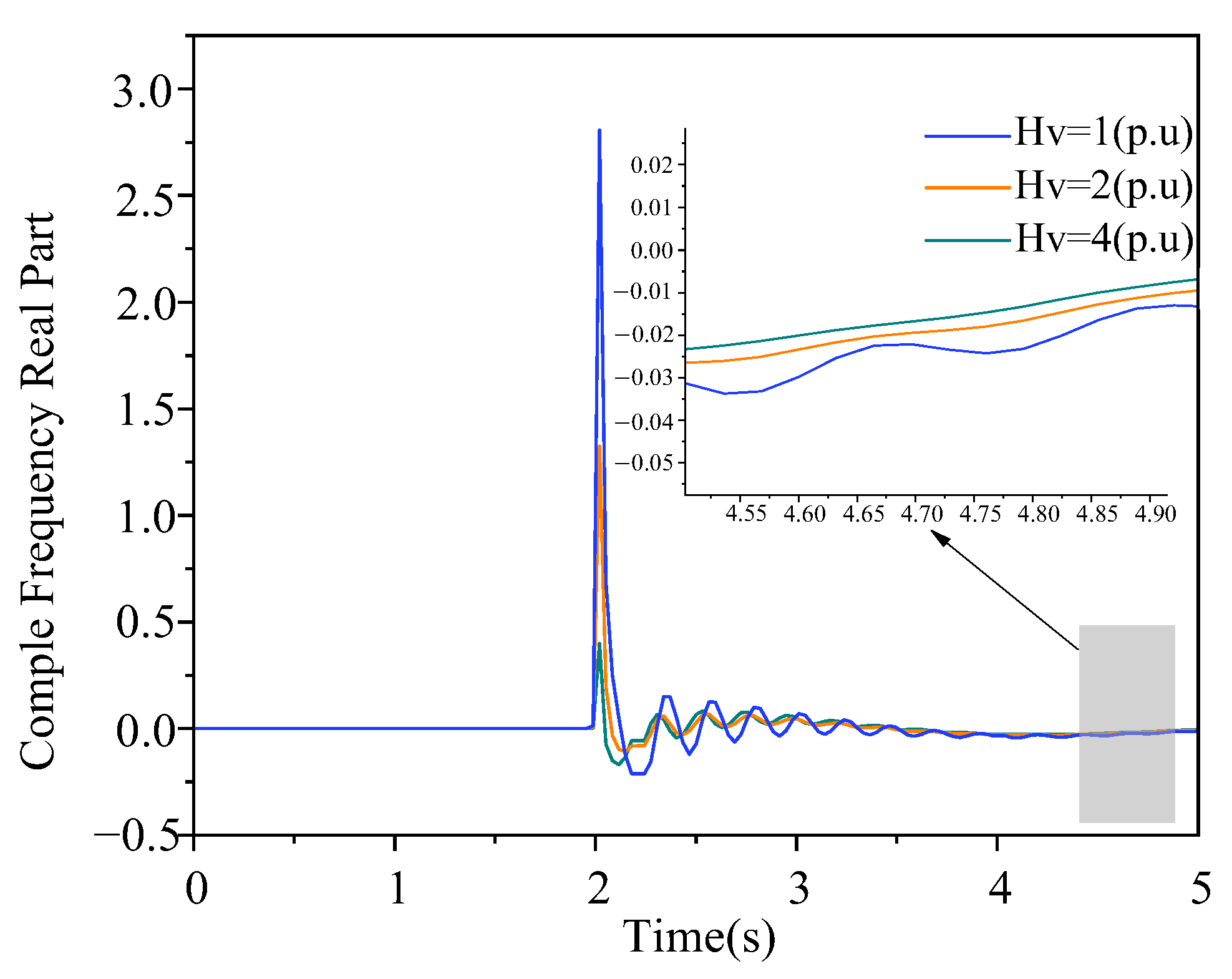

3.3. Effect of Voltage Inertia Values

3.3.1. Effect of Voltage Level

3.3.2. Effect of Equivalent Capacitance/Equivalent Susceptance

3.3.3. Effect of the Real Part of Complex Frequency

4. Case Studies

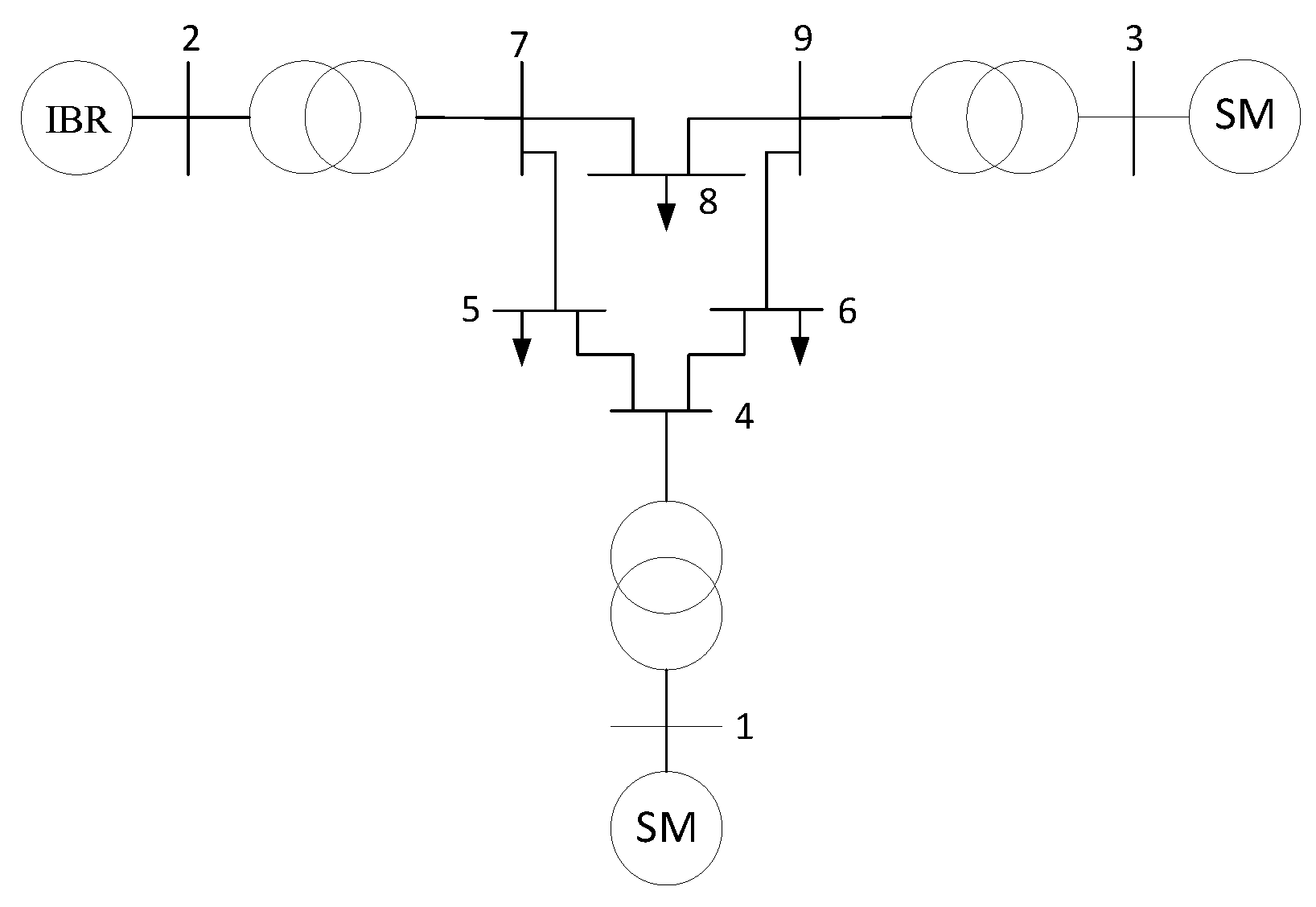

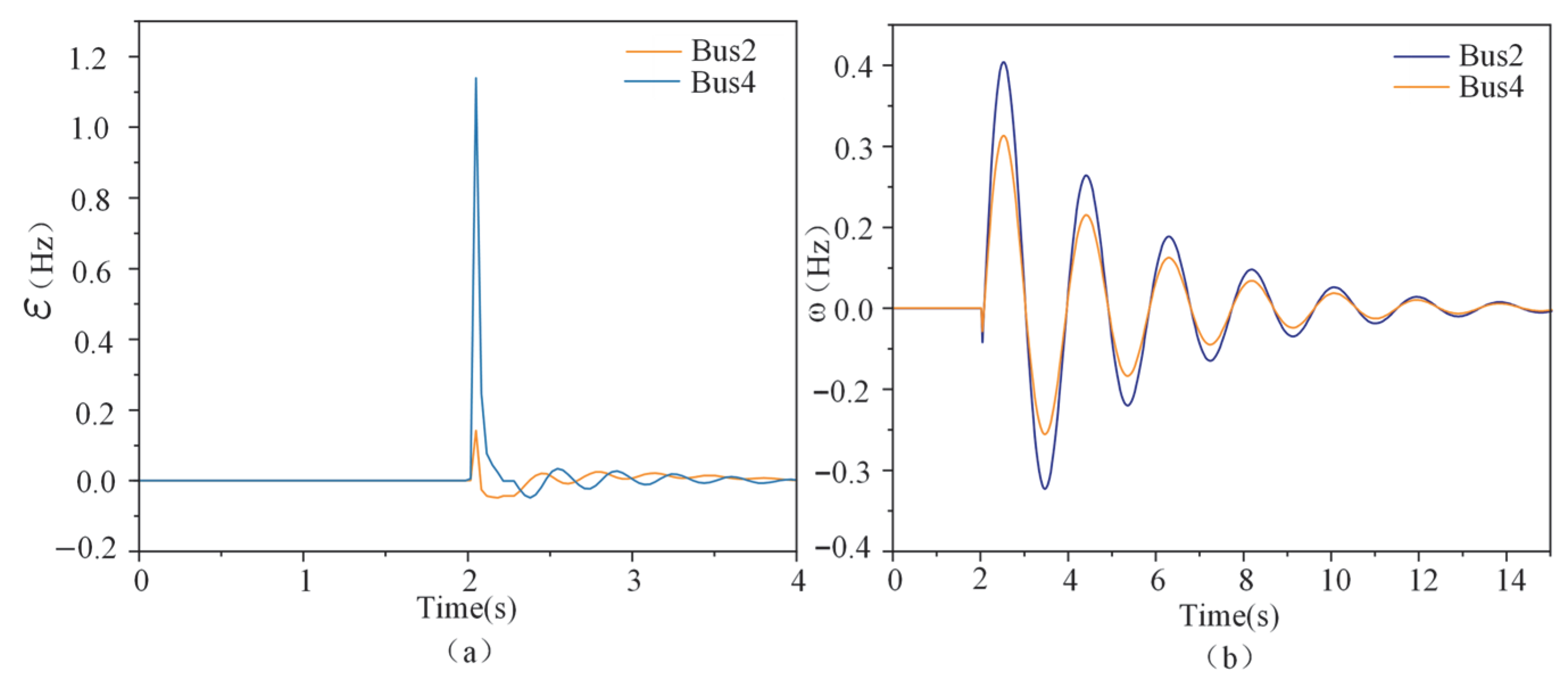

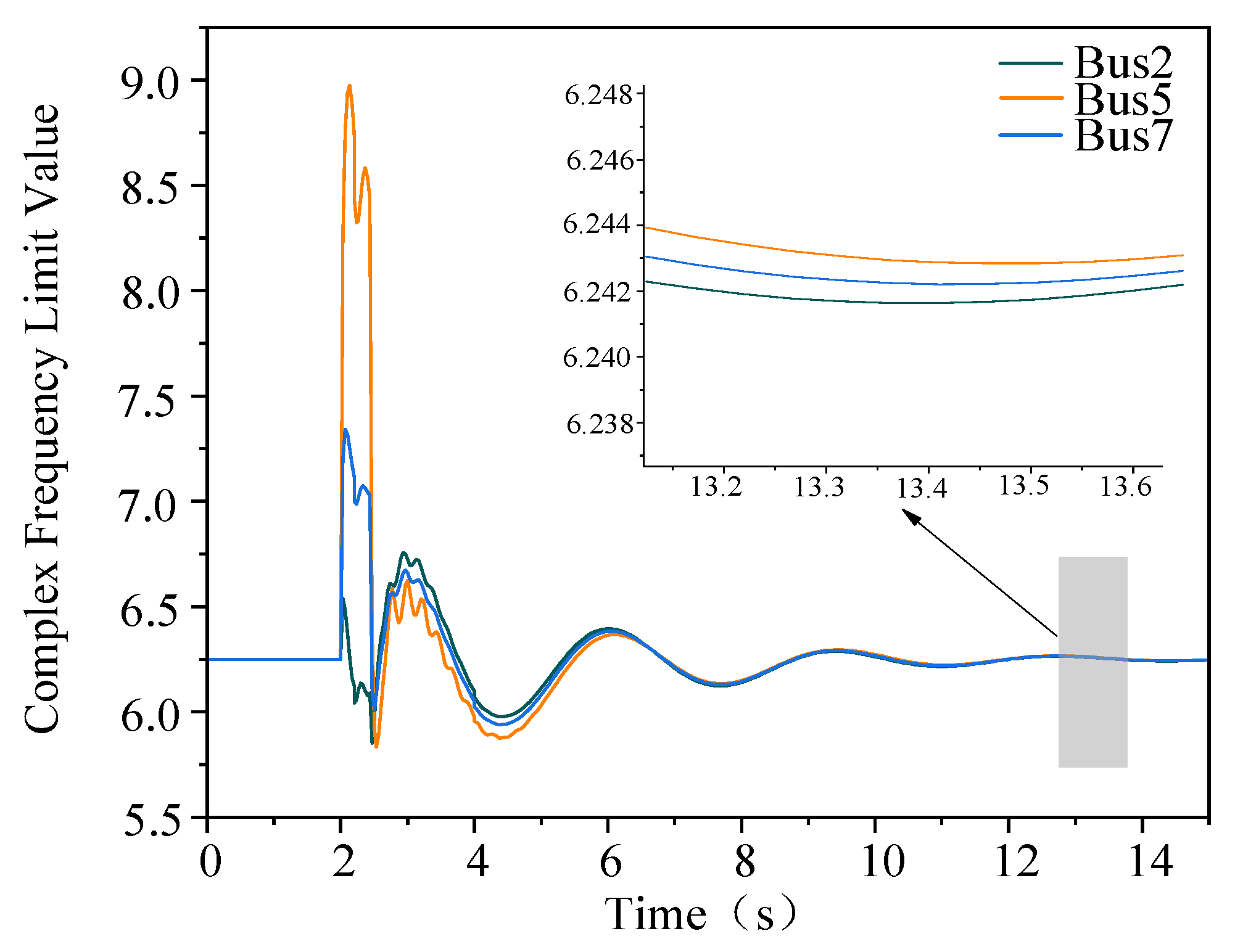

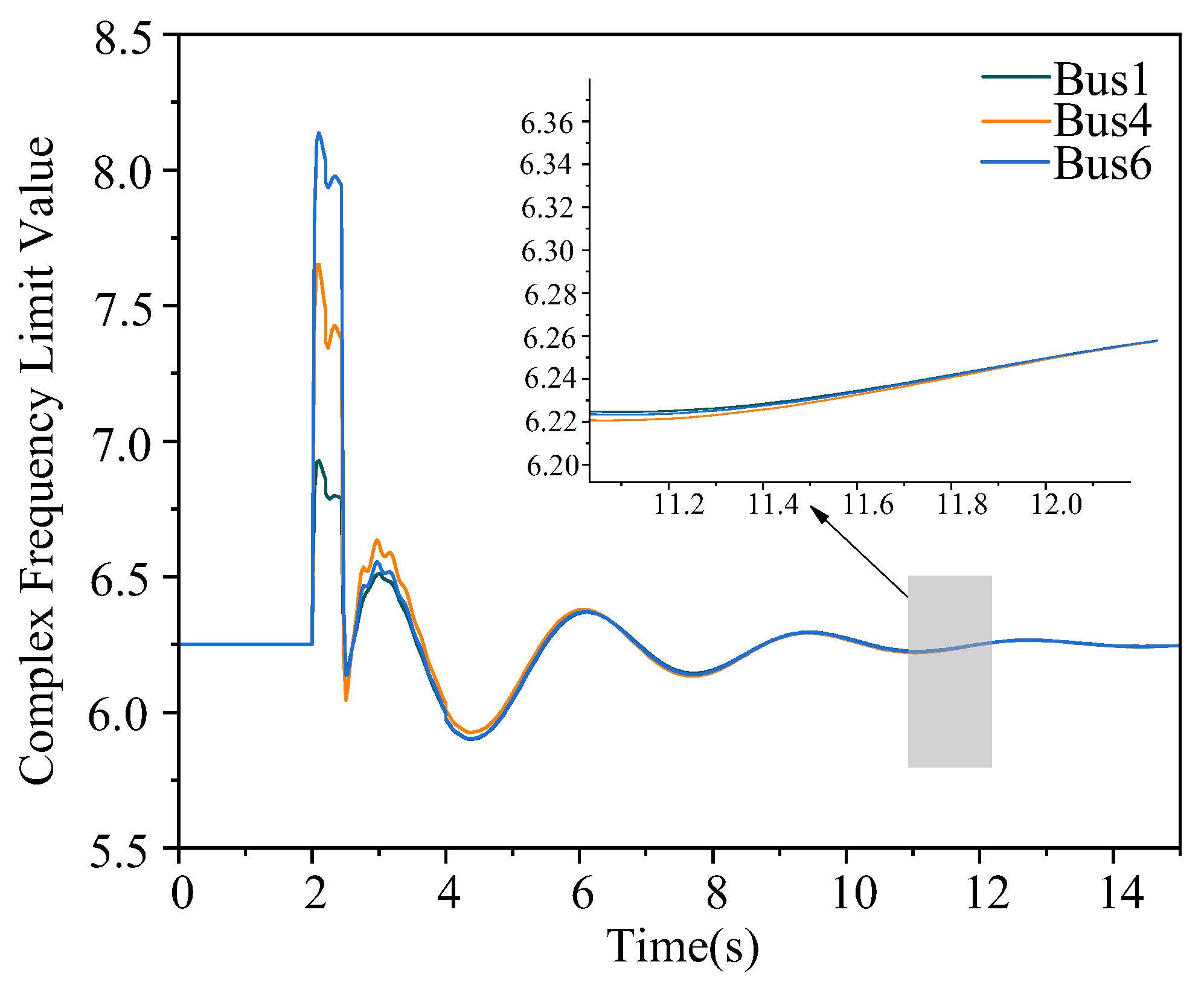

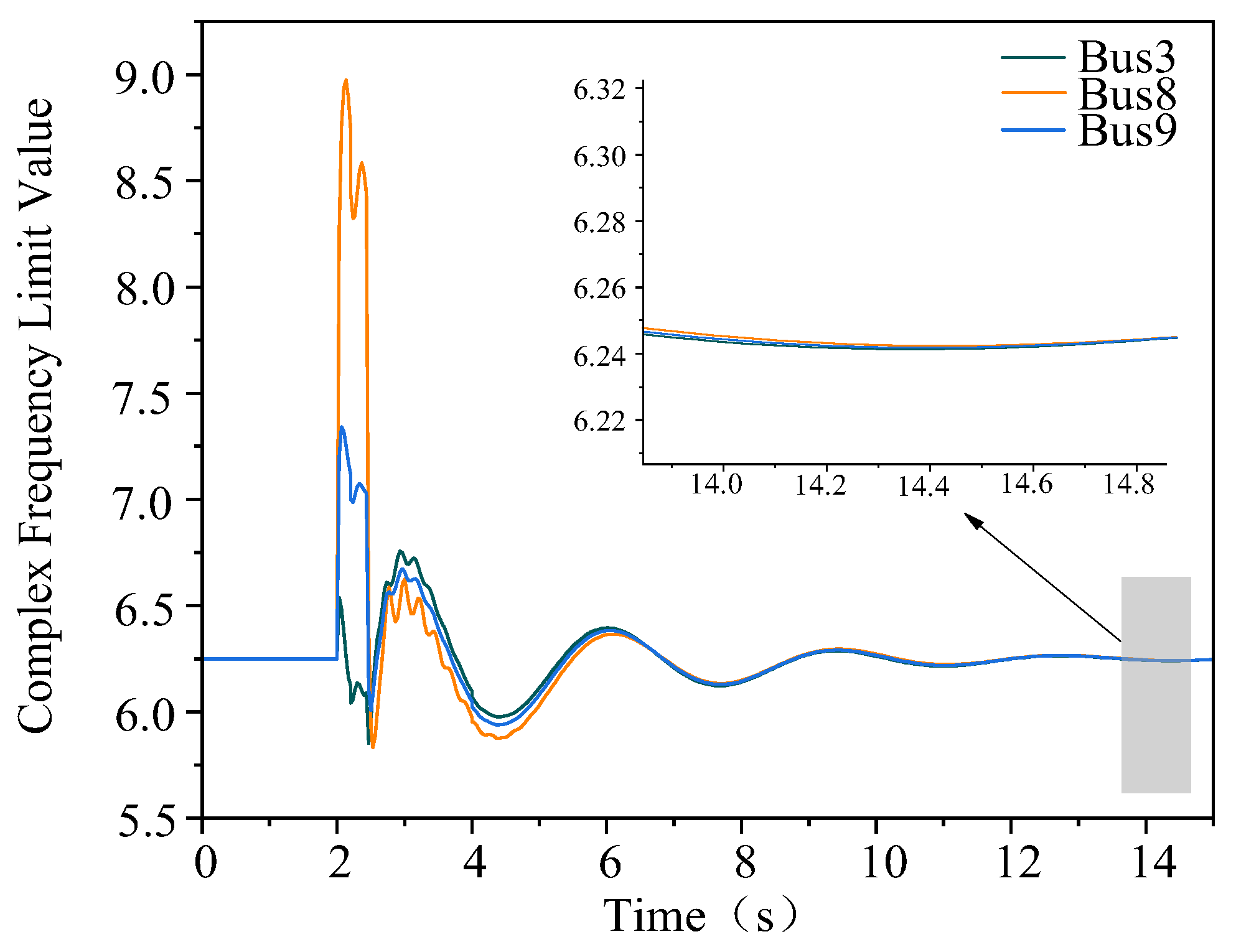

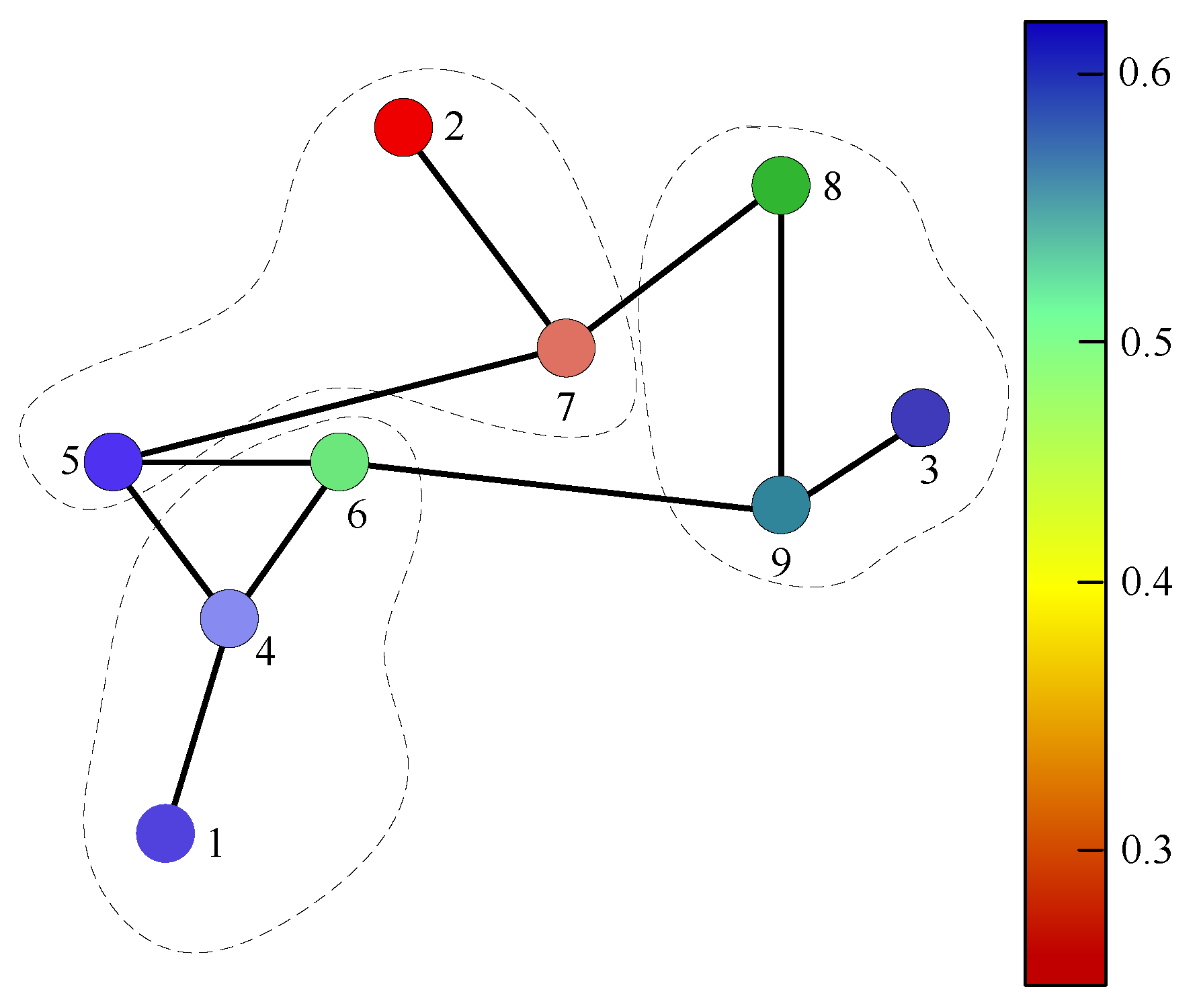

4.1. Local Synchronization Analysis

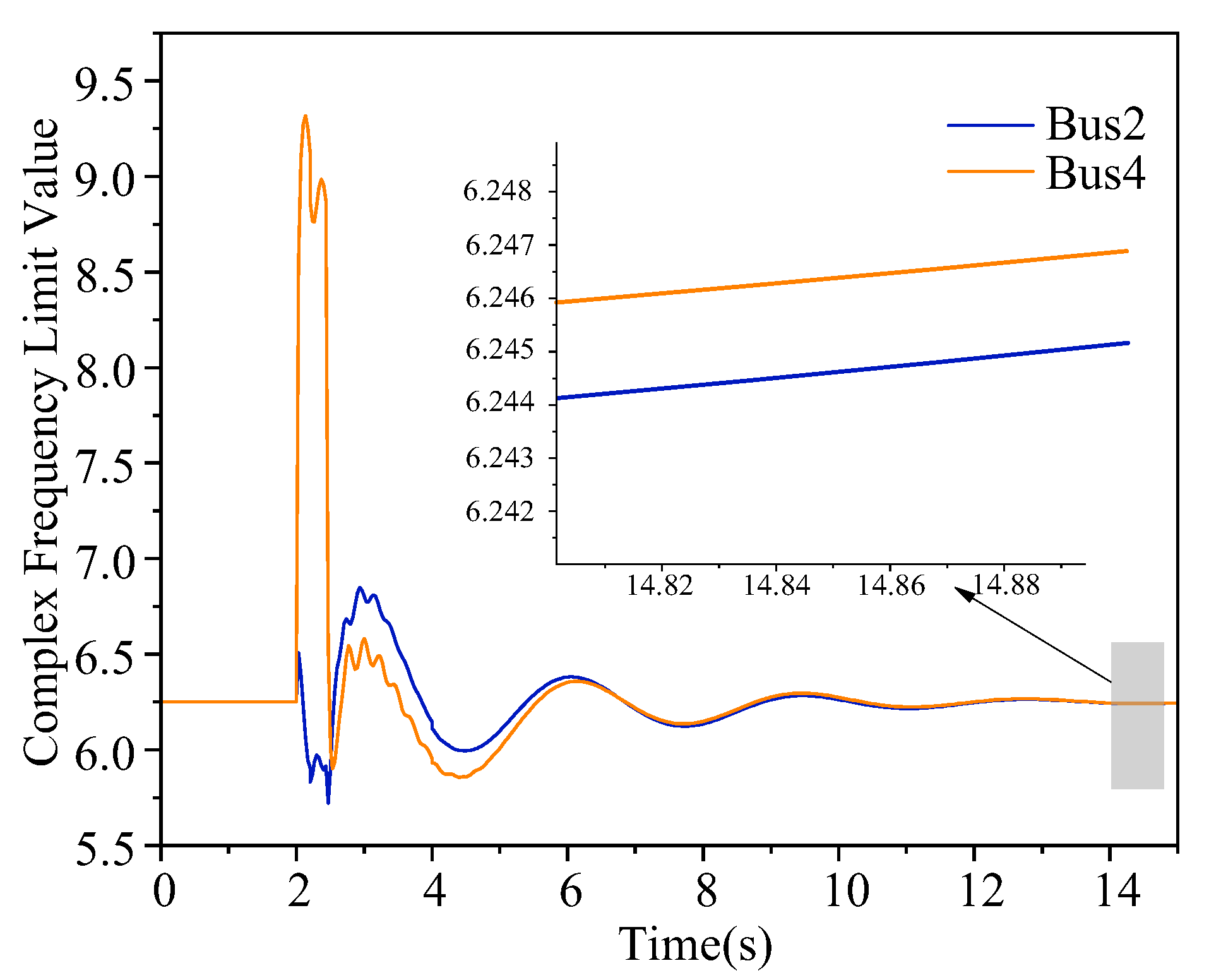

4.2. Global Synchronization Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sajadi, R.; Kenyon, W.; Hodge, B.M. Synchronization in electric power networks with inherent heterogeneity up to 100% inverter based renewable generation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Milanovic, J.; Rahmann, C.; Ajjarapu, V.; Canizares, C.; Erlich, I.; Hill, D.; Hiskens, I.; Kamwa, I.; Pal, B.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability—Revisited & extended. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3271–3281. [Google Scholar]

- Paganini, F.; Mallada, E. Global analysis of synchronization per-formance for power systems: Bridging the theory-practice gap. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 3007–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombino, M.; Groß, D.; Brouillon, J.-S.; Dörfler, F. Global phase and magnitude synchronization of coupled oscillators with application to the control of grid-forming power inverters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 4496–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.; Paserba, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Andersson, G.; Bose, A.; Canizares, C.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Hill, D.; Stankovic, A.; Taylor, C.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability IEEE/CIGRE joint task force on stability terms and definitions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Mao, H. Spectral analysis of network coupling on power system synchronization with varying phases and voltages. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 22–24 August 2020; pp. 880–885. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, W. Synchronizability and synchronization rate of ac microgrids: A topological perspective. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 1424–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NERC/WECC Joint Task Force. 1200 MW Fault Induced Solar Photo-Voltaic Resource Interruption Disturbance Report; Technical Report; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ulbig, A.; Borsche, T.S.; Andersson, G. Impact of low rotational inertia on power system stability and operation. IFAC Proc. 2014, 47, 7290–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, U.; Stanojev, O.; Aristidou, P.; Vrettos, E.; Callaway, D.; Hug, G. Understanding small-signal stability of low-inertia systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3997–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, P.; Gevorgian, V.; Zhang, Y. Inertia and the Power Grid: A Guide Without the Spin; Technical Report; NREL/TP-6A20-73856; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhujel, N.; Tamrakar, U.; Hansen, T.M.; Byrne, R.H.; Tonkoski, R. Model predictive integrated voltage and frequency support in microgrids. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES General Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, R.; Milano, F. Improving voltage and frequency control of DERs through dynamic power compensation. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, F. Complex frequency. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Geng, H. PLL Synchronization Stability of Grid-Connected Multiconverter Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, F.; Liu, T.; Hill, D.J. Augmented synchronization of power systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 3673–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. Complex frequency wave analysis for electric networks. J. Guangxi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1988, 13, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Häberle, V.; Dörfler, F. Complex-Frequency Synchronization of Converter-Based Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Control. Netw. Syst. 2024, 12, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, B.; Ponce, I.; Dotta, D.; Milano, F. Teager Energy Operator as a Metric to Evaluate Local Synchronization of Power System Devices. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Green, T.C. Power System Stability With a High Penetration of Inverter-Based Resources. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 832–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, F.; Dorfler, F.; Hug, G.; Hill, D.J.; Verbi, G. Foundations and Challenges of Low-Inertia Systems (Invited Paper). In Proceedings of the 2018 Power Systems Computation Conference (PSCC), Dublin, Ireland, 11–15 June 2018; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8450880 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Trujillo, M.; Sajadi, A.; Shaw, J.; Hodge, B.-M. Computationally Efficient Analytical Models of Frequency and Voltage in Low-Inertia Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Enrich, R.; He, X.; Häberle, V.; Dörfler, F. Dynamic Complex-Frequency Control of Grid-Forming Converters. In Proceedings of the IECON 2024-50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y. The definition of power grid strength and its calculation methods for power systems with high proportion nonsynchronous-machine sources. Energies 2023, 16, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.; Milano, F. Comparison of different PLL implementations for frequency estimation and control. In Proceedings of the 2018 18th International Conference Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 13–16 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Magnússon, S.; Coffrin, C.; Dörfler, F.; Hug, G.; Modaresi, J. Common-Mode Frequency of Power Systems Affected by Voltage Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 3279–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, I.; Milano, F. Analytical Framework for Power System Strength. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompoobutrgool, Y.; Li, W.; Vanfretti, L. Development and implementation of a Nordic grid model for power system small-signal and transient stability studies in a free and open source software. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Hill, D.J. Stability analysis of power systems: A network synchronization perspective. SIAM J. Control. Optim. 2018, 56, 1640–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.M. A reactance theorem. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1924, 3, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecchino, A.; Marinelli, M. Analytical assessment of voltage support via reactive power from new electric vehicles supply equipment in radial distribution grids with voltage-dependent loads. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 97, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, F.; Tomsovic, K. Hybrid Symbolic-Numeric Framework for Power System Modeling and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R.; Milano, F. Complex Frequency-Based Control for Inverter-Based Resources. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, R.; Holmes, D.G.; McGrath, B.P.; Meegahapola, L.G. Control of active and reactive power ripple to mitigate unbalanced grid voltages. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 1660–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, A.; Zhao, M.; Kocar, I.; Karaagac, U.; Chan, K.W.; Farantatos, E. Impact of inverter-based resources on negative sequence quantities-based protection elements. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Conventional Synchronization | Complex Frequency Synchronization |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronized variable | Angular frequencyconsistency ( or ) | Complex frequency consistency |

| Core requirement | (or ) | , both and |

| Physical meaning | Captures synchronization in the frequency/angle channel | Captures coordinated synchronization in both voltage magnitude dynamics and frequency/angle dynamics |

| Characteristics of desynchronization | Persistent mismatch in angle speed trajectories | Mismatch in either channel; notably, apparent frequency synchronization but internal desynchronization can occur when aligns while does not |

| Suited scenarios | Synchronous generator-dominated grids, high voltage stiffness, small disturbances, quasi-steady conditions | Converter-dominated/low-inertia systems, weak grids, strong P–f and Q–V coupling, fast voltage control dynamics, PLL-related transients |

| Relationship between the two | - | Reduces to conventional synchronization when (voltage magnitude is nearly constant) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, P.; Li, K.; Xie, J. System Synchronization Based on Complex Frequency. Energies 2026, 19, 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030701

Tang L, Wei Y, Wang C, Li P, Li K, Xie J. System Synchronization Based on Complex Frequency. Energies. 2026; 19(3):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030701

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Lan, Yusen Wei, Chenglei Wang, Peidong Li, Ke Li, and Jiajun Xie. 2026. "System Synchronization Based on Complex Frequency" Energies 19, no. 3: 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030701

APA StyleTang, L., Wei, Y., Wang, C., Li, P., Li, K., & Xie, J. (2026). System Synchronization Based on Complex Frequency. Energies, 19(3), 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030701