Abstract

Determinants of consumers’ decisions in the electric vehicle market are dictated by many factors, starting from ecology to the profitability of owning an electric vehicle. Currently, the electric vehicle market in Poland grows every year. When addressing the issues related to the determinants of consumer decisions on the electric vehicle market, statistical data and an online questionnaire were used, in which 103 people, who were interested in electric vehicles, participated. The main purpose of this research was to determine what factors influence consumers’ attitude to the purchase of electric vehicles the most. The study focuses primarily on Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), as reflected in the survey design and respondents’ interpretations of electric vehicles. The study showed that over half of the respondents are considering the purchase of an electric vehicle, and to purchase this type of car they would be more encouraged by financial support, such as subsidies from the state and tax relief, as well as free parking spaces in cities. It was also established that consumers are discouraged from buying electric vehicles by the lack of adequate infrastructure in cities needed to freely own an electric vehicle, as well as too high prices of these cars and the long time it takes to charge the battery.

1. Introduction

The dawn of using electric vehicles as a means of transport can be traced back to the late 19th century. In 1880, Frenchman Gustave Trouvé constructed the first electric vehicle. Additionally, the first electric vehicle in the USA was constructed by William Morrison in 1890–1891, although people from this part of the world became more interested in electric vehicles only when Riker installed an engine in three-wheeled vehicles. Between 1890 and 1920, electric vehicles had their golden age. Until combustion cars were introduced into everyday use, which could cover longer distances and were cheaper than electric vehicles. Currently, electric vehicles are experiencing a renaissance, as society increasingly chooses such cars for many reasons related to environmental protection or ideological reasons. While China is the world leader, Norway and Germany are the leading European countries. According to research [1], the key factors influencing the development of the German electric vehicle market are as follows: energy prices and state compensation, as well as a flexible credit policy. The cited authors also emphasized the high uncertainty of the market evolution. In accordance with this state of affairs, state policy in this area should be adapted to dynamically changing market conditions. The increase in interest in electric vehicles in European countries may result not only from the growing ecological awareness and easier availability of such cars, but also from the introduction of government subsidies encouraging the change from cars with combustion engines to electric ones. This fact is confirmed by Bloomberg data. It was noted that the depletion of financial incentives to purchase electric vehicles contributed to the recorded decline in new car sales in Germany at the end of 2023.

A review of the literature on the subject [2] shows that the main factors shaping the development of the global electric vehicle market can be grouped into technical, economic (cost of vehicles, savings related to operating costs, and availability of charging stations), and environmental (ecological awareness of consumers and possibilities of reducing pollution). The potential of electric transport is estimated to be large enough to ensure the economic and energy security of individual countries. It is advisable to conduct research that will allow the identification of factors on both a micro and macro scale that influence the development of the electric vehicle market.

Recent research shows that governments worldwide are pursuing electric vehicle adoption not only for environmental and energy security reasons but also as part of strategic industrial policy efforts to build competitive automotive value chains and stimulate innovation in green technologies [3,4]. For example, national-level policies targeting EV and battery industries have been linked with increases in EV patent activity and broader innovation trends across the global automobile sector [3]. This aligns with systematic reviews highlighting the role of regulatory, incentive, and infrastructure measures as critical facilitators of EV adoption across different regions [4,5]. In large EV markets, such as China, government strategies explicitly incorporate industry support and export-oriented development objectives, further illustrating the dual environmental and competitive priorities of contemporary EV policy frameworks [6].

An assessment of the impact of car dealers’ activities on the level of sales of electric vehicles was conducted in the USA, California. The research results of the cited authors showed that lower profits obtained from the sale of electric vehicles contribute to sellers encouraging customers to purchase traditional models. In this context, legal regulations (e.g., in the form of stricter environmental requirements) and incentives (e.g., preferential tax policy for producers and compensation programs for the costs of purchasing an electric vehicle for buyers) are needed [7]. Based on the results of research conducted among two Greek electric vehicle distributors, it is pointed out that vehicle sellers have a critical influence on the decisions of their customers. Recommendations from the research to take action to increase the sales of electric vehicles in the country included the following: state aid in the appropriate training of sellers, dissemination of knowledge about the benefits of using electric vehicles, and improving the network of charging stations [8]. Analyzing the drivers and barriers to purchasing electric vehicles, the high cost of electric vehicles was identified as the main barrier. Purchasing decisions are strengthened by the expected moral satisfaction and high ecological awareness of consumers [9]. Research on the factors influencing the development of the electric vehicle market in Malaysia has shown that these include consumers’ concern for the environment, their knowledge about the advantages of electric vehicles, and psychological benefits [10]. Research was also carried out on the development possibilities of the Indian electric vehicle market, taking into account the barriers and benefits that may accompany a full transition to the use of electric transport; this research considered not only the technical aspects of this process (electric vehicle models, charging stations, and their network of charging methods, etc.), but also management (government policy supporting market development and the economic and environmental effects of the introduction of electric vehicles) [11].

Even before the outbreak of the war, the electric vehicle market in Ukraine was investigated. It has been noticed that the market is growing. Significant barriers to its expansion have been identified, including a poorly developed network of charging stations, as well as a limited possibility of charging an electric vehicle at home [12]. Subsequent researchers [13] also pointed out the high cost of purchasing an electric vehicle and too few specialists in the maintenance of electric transport in Ukraine. The validity of further government incentives for the development of the electromobility market was emphasized. Among the identified advantages of using electric vehicles, the authors mentioned—for the state—reduced environmental pollution, and—for owners—the opportunity to save on fuel.

Using the example of Poland in the post-COVID-19 reality, several groups of factors determining the electric vehicle market were distinguished, including the following [14]:

- (1)

- Government factors, stating that the effectiveness of government initiatives is not clear-cut, the quoted author identified the need for more effective educational campaigns;

- (2)

- Economic factors (e.g., inflation affecting the costs of vehicle production and the purchasing power of consumers, currency fluctuations affecting imports and the final price, and the price of electricity influencing the operating costs of electric vehicles);

- (3)

- Social factors (broadly understood safety, battery repairability, and range);

- (4)

- Technological factors (battery technology repair cost, fire risk, and increasing the charging network);

- (5)

- Ecological factors (questioning the environmental benefits of electric vehicles powered by non-renewable sources, recycling, and battery disposal).

It was pointed out [15] that the most frequently undertaken scientific research in the area of electric vehicles includes market segmentation, battery life and optimization, charging speed, and pricing policy. From an economic point of view, price is the basic determinant that has the greatest impact on decision-making, including the purchase of an electric vehicle. The modern consumer has increasing knowledge, including information about the goods they decide to purchase. We are probably dealing with a similar situation in the electric vehicle market. This manuscript focuses on understanding the issue, especially from the consumer’s perspective. Electric vehicles include several technological categories, most notably Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs), and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs), each characterized by different operational constraints and infrastructural requirements [16,17]. Technical challenges highlighted in the recent literature concern battery size and range limitations, safety considerations, charging time, and battery degradation [18,19,20,21]. Another relevant factor involves the types and capacities of charging infrastructure. Slow AC charging, fast DC charging, and ultra-fast charging vary significantly in availability and charging times, with implications for grid stability and peak-load management [22]. Limited charger density, long charging sessions, and potential grid bottlenecks are therefore important determinants of consumers’ willingness to adopt electric vehicles.

The novelty of this study lies in its inferential assessment of electric vehicle adoption barriers in Poland during the early implementation phase of EU decarbonization policies, providing updated, context-specific evidence from an emerging EV market. The aim of the study was to determine what factors influence consumers’ decisions regarding the purchase of cars with an electric engine. The research problem undertaken is relatively new, but it constitutes a promising research need. Electric vehicles are somewhat controversial because, while they are zero-emission vehicles in themselves, the batteries are difficult to recycle or dispose of; in addition, they are charged with energy obtained from coal, which is not an ecological way of generating energy. Hence, there are discussions about whether electric vehicles are truly ecological vehicles.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the research design, data collection procedure, and statistical methods used. Section 3 presents the empirical results derived from descriptive and inferential analyses. Section 4 discusses the findings in the context of the international literature and policy implications. Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions and outlining directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the literature on the subject, a research gap was identified in the electric vehicle market in Poland. This research attempted to understand the respondents’ attitude to electric vehicles, and to learn about the factors determining their decisions in this market. The intention was to uncover the respondents’ attitude towards electric vehicles, including their doubts, beliefs, and views, and conduct an assessment of the prospects for this market in Poland. However, the empirical part of this study refers to electric vehicles as understood by respondents, which, in practice, predominantly correspond to Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs). Therefore, no distinction between EV subtypes is made in the survey analysis. The study design did not distinguish between subtypes of electric vehicles, and the analysis was not intended to make generalizations across different electric vehicle technologies. The survey was conducted in 2023, a period chosen to ensure stability in market conditions, availability of up-to-date policy incentives, and comparability with national EV registration statistics. The questionnaire was modeled on established consumer-adoption frameworks, including segmentation and behavioral intention models used in EV adoption studies [15,23]. The structure of the questionnaire was also aligned with the communication- and perception-related determinants incorporated in the goal-directed behavior model for electric vehicle adoption proposed by He and Hu [24].

The study addressed the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What are the key economic, technical, and environmental determinants of electric vehicle (EV) purchase intentions in Poland?

RQ2: To what extent do demographic characteristics (age and education) influence perceptions of incentives and barriers?

RQ3: Which perceived barriers are the strongest predictors of reduced likelihood of EV purchase?

The study used an online survey method. Survey research is characterized by obtaining opinions and data from respondents, analyzing their market behavior, preferences, and data on decisions made. The questions included in the survey were related to feelings and views regarding electric vehicles, and the assessment of the future of the electric vehicle market in Poland. The survey was addressed to users of the Facebook social networking site (in the group of people interested in electric vehicles), where it was also published. A total of 103 people took part in the study. Although the sample size of 103 respondents is relatively modest, similar sample sizes are commonly used in exploratory consumer surveys on electric vehicle adoption. For example, Hanus [25] conducted a survey of Polish consumers with 130 participants to analyze attitudes toward electric vehicles and purchase determinants. Similarly, Sureshkumar and Adarsh [26] employed a survey with approximately 100 respondents to examine consumer perceptions and adoption barriers of EVs in an emerging market context. The research results were supplemented with statistical data regarding, among others, the number of electric vehicles in Poland. Tabular, descriptive, and graphic forms of data presentation were used to present the results.

Consumer decisions are determined by many factors, which may be related to the consumer’s value system, their needs and expectations, brand loyalty, or the search for the best offer on the market. A total of 36 women (35%) and 67 men (65%) participated in the study. Respondents aged 18–26 constituted the largest group (52.43%), the second largest group were those aged 27–35 (22.33%), and the next largest groups were those aged 36–44 (16.50%) and 45–53 years (5.83%). The smallest group of respondents were the oldest ones, from 54 to 62 years old (2.91%). Respondents who declared having a master’s degree were the largest group of respondents (34.95%), the second largest group were those with a bachelor’s degree (33.98%), and then those with secondary education (25.24%). Some respondents had vocational education (3.88%) and post-secondary education (1.94%).

In addition to descriptive statistics, the study employed inferential methods to examine whether observed differences in attitudes were statistically meaningful. Because the questionnaire used ordinal Likert-type scales (1–5), the data did not meet the assumptions of normality required for parametric procedures, Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was used to analyze associations between key perceived barriers (price, infrastructure, range, and charging time) and the respondents’ likelihood of purchasing an electric vehicle. Spearman correlation is a robust non-parametric measure commonly applied in exploratory consumer research, particularly with modest sample sizes such as in this study (n = 103).

Additionally, chi-square tests of independence were conducted to assess the relationships between categorical variables, including the following:

- −

- Age and purchase intention;

- −

- Education level and perceived effectiveness of financial incentives.

Standard significance thresholds (α = 0.05) were applied, and all tests were two-tailed. The results provide an exploratory assessment of whether demographic factors or perceived barriers are significantly associated with purchase intentions.

To further assess the methodological adequacy of the sample size, we note that exploratory consumer research commonly relies on samples of 100–150 respondents. Power analyses for non-parametric tests comparable to those used in this study (Spearman correlations and chi-square tests) indicate sufficient statistical power for detecting medium-to-large effects (Cohen’s d ≥ 0.3). Therefore, the sample of 103 respondents was adequate for the inferential procedures applied. The internal consistency of the multi-item scales used in the questionnaire was verified using Cronbach’s alpha. The reliability of the barrier scale (price, infrastructure, range, and charging time) was acceptable (α = 0.78), and the reliability of the benefits scale (nine items) reached α = 0.83, indicating good internal consistency for exploratory analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Survey-Based Analysis of Consumer Attitudes

The number of registered electric vehicles is growing in EU countries. This is a consequence of, among others, the need to reduce greenhouse gases determined by the assumptions of Fit for 55. There is also an expansion of the infrastructure network necessary for the operation of vehicles powered by current engines. Among other things, as a result of the following changes in European Union regulations, cars powered by electric engines appeared in Poland. There is a noticeable increase in the number of registrations of cars with this type of drive in Poland. In 2019, the number of electric vehicles was expressed in thousands, and in subsequent years—in tens of thousands. According to data from the Polish Alternative Fuels Association (Table 1). The total numerical value of registered electric vehicles in four years has increased almost 11 times compared to 2019. This provides an average result of 22,298 newly registered electric vehicles per year.

Table 1.

Number of electric vehicles in Poland in 2019–2023.

It should be emphasized that the sampling strategy—recruiting respondents exclusively through a Facebook group devoted to electric vehicle enthusiasts—introduces a positive attitudinal bias, as members of such groups are already more interested in electromobility than the general population. Consequently, the results should be interpreted as reflecting the perceptions of a technologically informed and mobility-oriented subgroup rather than the national consumer base. Additionally, the sample is strongly skewed toward young and highly educated respondents (over 74% under 35 years old and nearly 70% with tertiary education). This demographic profile further limits the transferability of the findings to the broader Polish population. We therefore frame all conclusions as representative of an EV-interested consumer segment rather than the market at large.

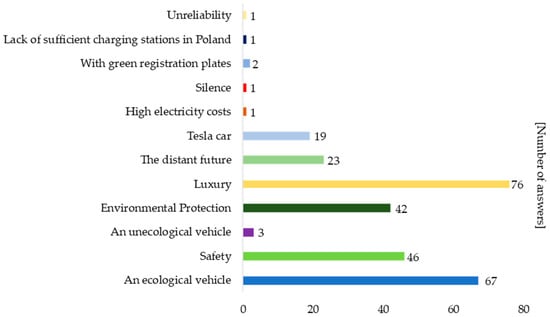

The respondents were asked what they associated electric vehicles with. The most frequently chosen answer was luxury—76 people (73.79%). The second most popular connotation was an ecological vehicle—67 people (65.05%), while the third most common indication was safety—46 people (44.66%) (Figure 1). The surveyed group least often associated electric vehicles with unreliability, silence, high electricity costs, or the shortage of charging stations. An interesting finding was the appearance of the Tesla car brand among the respondents’ answers. It proves how this brand has become embedded in the respondents’ minds. This answer was most often given by respondents aged 18–26.

Figure 1.

What do you associate an electric vehicle with?

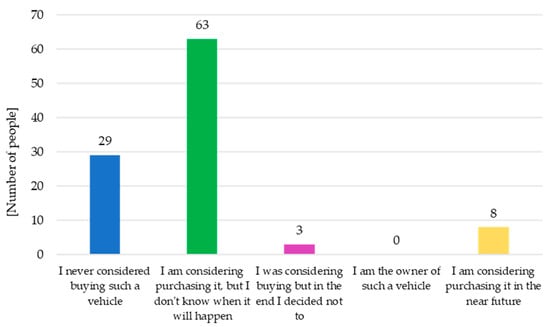

The respondents were also asked whether they had ever considered buying an electric vehicle (Figure 2). The vast majority of them, 63 people (61.17%), answered that they were considering the purchase but did not know when it would happen, while 8 respondents (7.77%) indicated that they were planning to purchase this type of car in the near future. This attitude may result from legal regulations regarding combustion cars or the cessation of production of combustion cars by some companies.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ opinion on purchasing an electric vehicle.

According to the Electromobility Development Plan in Poland (2016), prepared by the Ministry of Energy, consideration is being given to abolishing the emission fee for electric vehicles and introducing paid zones in cities for combustion cars. Such regulations are intended to create the belief that electric vehicles are a good alternative to combustion cars. But such actions will be taken not only to encourage consumers to buy electric vehicles. The plan includes bringing battery prices down to a level where the prices of electric vehicles are competitive with the prices of combustion cars. However, 29 people (28.16%) indicated in the survey that they had never considered purchasing this type of car. This attitude may result from the current prices of electric vehicles on the market and the lack of appropriate infrastructure for electric vehicles (e.g., charging stations).

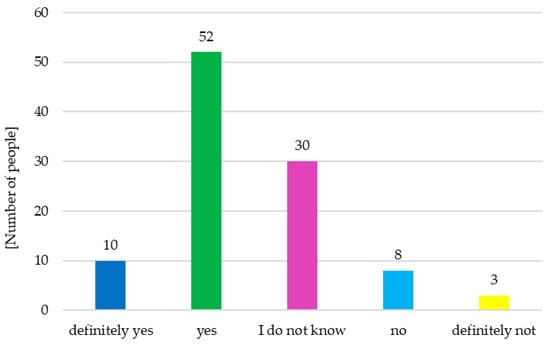

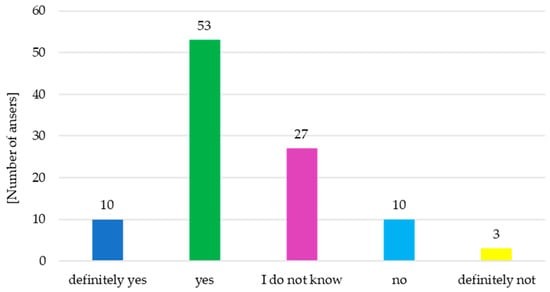

When the respondents were asked whether they would decide to buy an electric vehicle if they had the financial means (Figure 3), and whether they would buy this type of car for environmental protection reasons (Figure 4), more than half of the respondents, 52 people (50.49%), answered that they could buy a car of this type if their financial resources allowed it, and 10 (9.71%) respondents answered that they would definitely buy such a car.

Figure 3.

Financial resources and the purchase of an electric vehicle.

Figure 4.

Ecology and the purchase of an electric vehicle.

However, when asked about buying an “electric” car for ecological reasons, 53 people (51.46%) answered that they could, and 10 respondents (9.71%) answered that they would definitely buy such a car for these reasons. It can be concluded that the prices of electric vehicles are one of the main factors that deter respondents from buying an electric vehicle. However, 30 respondents (29.13%) answered that they did not know whether they would buy an electric vehicle if they had the funds to purchase such a car, and regarding ecological reasons—27 respondents (26.21%) did not know whether they would prompt them to buy such a car (Figure 4). Therefore, if the state wants to achieve the assumed goals regarding electromobility in Poland, it would be necessary to ensure that the prices of electric vehicles are competitive in relation to combustion cars, as this is one of the main problems regarding electric vehicles in Poland, as indicated by the respondents.

The Polish state should also encourage Polish or foreign technology companies operating in Poland to develop technology that would allow them to somehow reduce the prices of such cars. The authorities should also purchase such a car more profitable for consumers and convince them that it is worth owning such cars for ecological reasons through appropriate campaigns raising awareness that these cars are ecological and that the electricity that will be used to charge electric vehicles will come from ecological sources. A total of 13 respondents (12.62%) were against purchasing an electric vehicle for ecological reasons, and 11 respondents (10.68%) would not buy a car of this type if they had the financial means. This may reflect skepticism about electric vehicles, the belief that these cars are generally not good for the environment. Another reason could be that people are accustomed to combustion cars and consider them the best option for an everyday-use car.

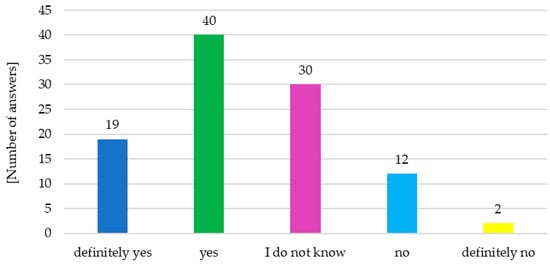

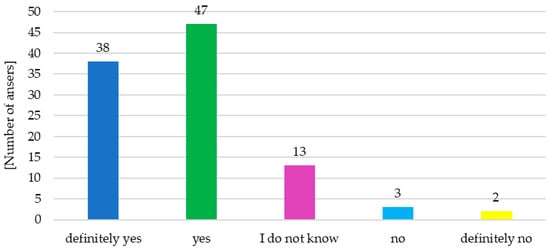

The respondents were asked which of the three forms of financial support would encourage them to purchase an electric vehicle and to what extent; these were as follows: tax relief during the period of operation (e.g., deduction from income) (Figure 5), co-financing the purchase under publicly available funds (Figure 6), and tax relief when purchasing (e.g., excise tax refund). Their answers were as follows. The most encouraging form of financial support according to the respondents was tax relief during the period of use, which would allow them to deduct part of the amount from their income, thanks to which some of the money spent on operating the car would be returned to their wallets every year. This is the form of support with which 38 respondents (36.89%) would definitely be encouraged, and 47 respondents (45.63%) could decide to buy an electric vehicle. However, this form of support would not encourage two respondents at all (1.94%), or might not encourage only three respondents (2.91%).

Figure 5.

Answers of respondents on the validity of subsidizing the purchase of an electric vehicle in the form of a tax relief during operation.

Figure 6.

Answers of respondents regarding co-financing for the purchase of an electric vehicle in the form of payment programs.

Financing in the form of publicly available programs (e.g., My Electric) did not appeal to many respondents. Only 19 (18.45%) would fully use this option, and 40 respondents (38.83%) might use this form of support. However, 2 people (1.94%) would certainly not use the proposed form of support, and 12 (11.65%) respondents could just consider using it. It can be assumed that this form of support was not appreciated by the respondents because they were afraid that during the financial process of purchasing a car with this option, they could encounter bureaucracy and a long waiting time for a positive decision from the body that would provide support, which may discourage them from using this form of funding.

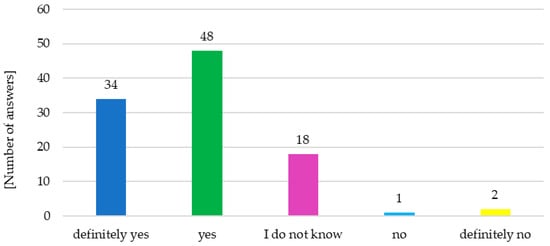

The relief for purchasing an electric vehicle raised similar interest to tax relief during operation. If such a form of support was available, 34 respondents (33.01%) would decide to buy an electric vehicle, and 48 respondents (46.60%) could make such a purchase. However, only two people (1.94%) would not decide to buy such a car only because this type of relief was available (Figure 7). Analyzing these data, it can be concluded that the respondents are more satisfied with forms of support such as tax reliefs than a certain calculated amount of money from the government.

Figure 7.

Answers of respondents regarding support for the purchase of an electric vehicle in the form of tax relief when purchasing.

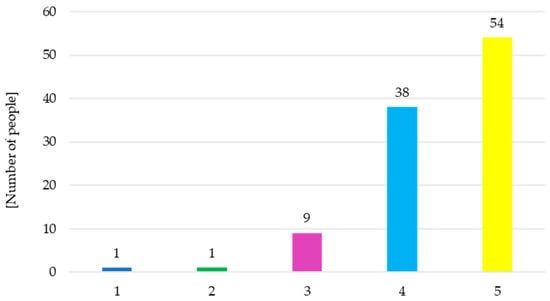

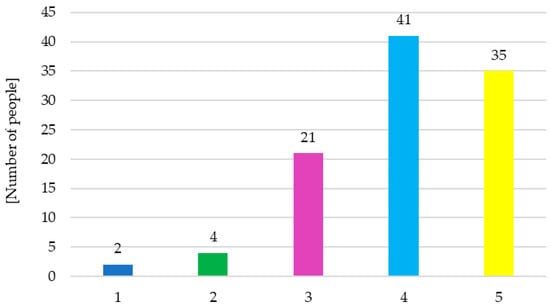

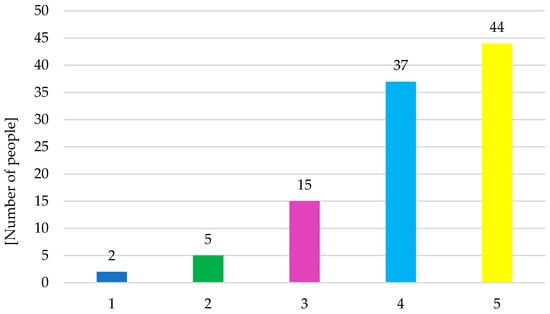

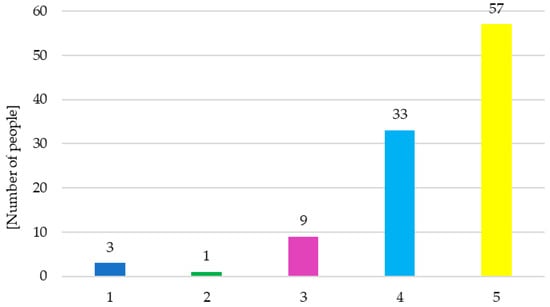

The respondents were also asked about technical limitations and which of them would be most important (on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means the least influence and 5 means the greatest influence) for their decision to purchase an electric vehicle. The technical limitations included in the question were as follows: lack of infrastructure (Figure 8), too small a range on one charge (Figure 9), long battery charging time (Figure 10), and too high prices (Figure 11).

Figure 8.

Impact of the lack of infrastructure on purchase; 1—least impact, 2—little impact, 3—medium impact, 4—huge impact, and 5—the greatest impact.

Figure 9.

The impact of too short range of an electric vehicle battery on the purchase; 1—least impact, 2—little impact, 3—medium impact, 4—huge impact, and 5—greatest impact.

Figure 10.

The impact of too long a charging time on the purchase; 1—least impact, 2—little impact, 3—medium impact, 4—huge impact, and 5—greatest impact.

Figure 11.

The impact of too high prices on purchases; 1—least impact, 2—little impact, 3—medium impact, 4—huge impact, and 5—greatest impact.

For the surveyed group, the greatest impact on their decision to buy a car would be the limitations related to the lack of infrastructure; 54 people (52.43%) rated this limitation as 5 (on a 5-point scale, where 5—definitely yes and 1—definitely not). As regards too high prices, 57 people (55.34%) scored this limitation as 5 on the given scale, and too long battery charging time would also have a significant impact on the decision to buy an electric vehicle for 44 people (42.72%).

For the respondents, the possibility of driving too few kilometers on one charge would have less impact (4) on their decision compared to the previously mentioned limitations, as 41 people (39.81%) chose this score on the given scale, although for 35 respondents (33.98%), it was the biggest limitation (5).

For some respondents, the decision to buy an electric vehicle would not be influenced by any of the restrictions. The lack of infrastructure would not have an impact on one respondent (0.97%), which means that this person would most likely charge their electric vehicle at home, from their energy sources. Too small battery range would not be a limitation for two respondents (1.94%). Long battery charging time would not be a limitation for two respondents, and too high prices would be a limitation for three respondents (2.91%).

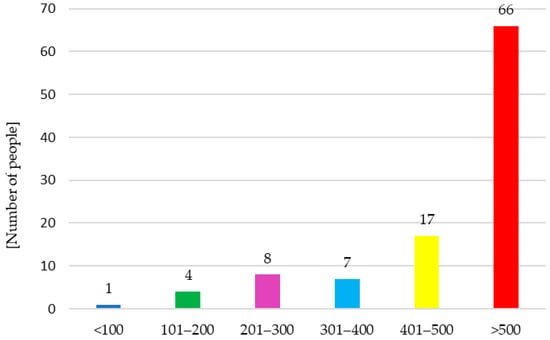

Next, the respondents were asked about the acceptable distance to travel on one charge (Figure 12). The majority, i.e., 66 respondents (64.08%), answered that the acceptable distance to travel on one charge is 500 km and more; the second most common indication was from 401 to 500 km (17 respondents—16.50%). However, only one respondent answered that the acceptable driving distance is up to 100 km. This attitude of the respondents is most likely due to being accustomed to the range of combustion cars, which can travel up to 1000 km on a full tank.

Figure 12.

Acceptable distance to travel on one charge.

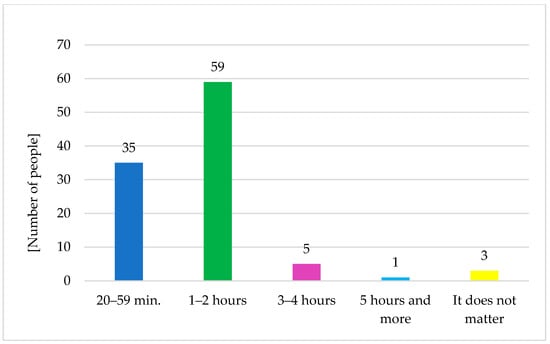

The respondents were also asked about the acceptable time for charging the battery to 100% (Figure 13). Most often, the respondents answered that for them, the acceptable time for fully charging the battery was from 1 to 2 h, as this answer was given by 59 people (57.28%). For 35 respondents (33.98%), the acceptable battery charging time was in the range of 20–59 min. For only three respondents (2.91%), the battery charging time is unimportant. It is possible that in the future, a technology will be created that will shorten the battery charging time to full by 20 to 30 min. Currently, the battery charging time varies depending on the capacity of the battery. Typically, in cars with medium capacity, the battery charging time for the next 100 km is 25 min, so if the batteries installed in the car allow you to travel 400 km on one charge, the time to fully charge is one hour. Therefore, in Poland, consumers in the car market are still turning to combustion cars, one reason being that such a car can be refueled relatively quickly.

Figure 13.

Acceptable battery charging time to 100% capacity of the battery.

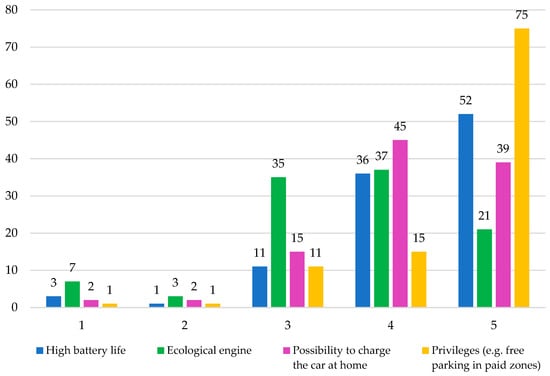

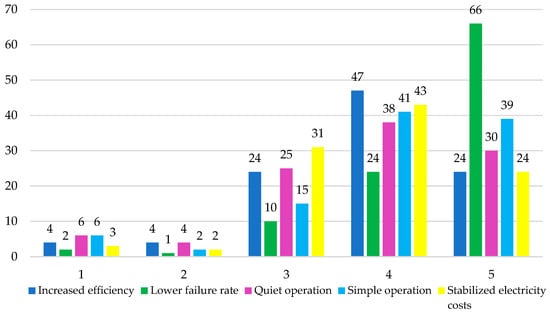

The respondents were also asked which of the benefits included in the cafeteria would encourage them to buy an electric vehicle (on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means it would not encourage it and 5 means it would encourage it the most). The group of respondents had the following benefits to choose from: long battery life, eco-friendly engine, ability to charge the car at home, privileges (e.g., free parking in paid zones) (Figure 14), increased efficiency, lower failure rate, quiet operation, simple operation, and stabilized costs of electricity (Figure 15).

Figure 14.

Benefits related to electric vehicles, part 1.

Figure 15.

Benefits related to electric vehicles, part 2.

Of the given benefits that would have the greatest impact on the purchase decision, respondents chose privileges (e.g., free parking spaces in paid zones); 75 people (72.82%) opted for the lower failure rate and 52 people (50.49%) indicated long battery life. These are benefits related to reducing the expenses incurred by car use. Lower failure rates entail fewer visits to a car mechanic, long battery life means lower expenses related to its replacement and purchase, and free parking in paid zones will save drivers money that they can spend on other consumer goods, because parking in cities, especially in their centers, is becoming more and more expensive. Another privilege is the ability to use bus lanes, which will allow one to move around the city faster, especially when there are traffic jams. The most frequently selected benefits that would encourage respondents to buy an electric vehicle less included increased efficiency—47 people (45.63%), the ability to charge the car at home—45 people (43.69%), and stabilized electricity costs—43 people (41.75%) (Figure 15).

The most frequently chosen benefits that would definitely not encourage respondents to buy an electric vehicle were as follows: ecological engine—seven people (6.80%) and quiet and easy operation of the car—six people (5.83%). Two of the three benefits concern the functioning of a car. This means that these benefits related to the functioning of a car have the least impact on the decision to buy a car among the respondents.

3.2. Inferential Statistical Results

To assess whether demographic characteristics were associated with purchase intention or perceptions of incentives, chi-square tests of independence were conducted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chi-square tests of independence (n = 103).

A chi-square test showed that the association between age and purchase intention was not statistically significant (χ2(16) = 20.84, p = 0.185), although the effect size indicates a weak trend (Cramer’s V = 0.22) in which younger respondents more frequently expressed willingness to purchase an electric vehicle. A second chi-square test assessed whether education level influenced respondents’ perceptions of tax relief incentives (χ2(8) = 14.11, p = 0.079), indicating a near-significant association. Respondents with higher education were more likely to evaluate tax relief as encouraging. To analyze the associations between perceived barriers and willingness to purchase an electric vehicle, Spearman correlations were calculated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations between perceived barriers and purchase likelihood.

Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated significant negative relationships between perceived barriers and purchase likelihood. The strongest effects were observed for price (ρ = −0.48, p < 0.001) and insufficient charging infrastructure (ρ = −0.41, p < 0.01). Charging time (ρ = −0.29, p = 0.004) and limited range (ρ = −0.22, p = 0.028) showed weaker but still noteworthy associations. These results demonstrate that economic and infrastructural barriers are the most influential factors reducing the likelihood of purchasing an EV, while technical factors, such as charging time and range, also play a role, albeit to a lesser extent. To further illustrate the relative strength of determinants, we compared mean scores for ecological motivations and financial motivations. Financial incentives (M = 4.21) were rated significantly higher than ecological motivations (M = 3.48), confirming that economic considerations are more decisive drivers of EV purchase intentions. This aligns with prior findings in Germany, Croatia, and India, where financial incentives consistently outperform environmental motives in predictive strength [16,27,28].

4. Discussion

The mobility needs of the population, most often linked to the use of private vehicles, contribute to significant socio-environmental problems [22,29]. Many authors emphasize that for electric vehicles, the EV type may be the solution to many such issues. Their more widespread use is hoped to enable lower fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [30,31,32]. To facilitate interpretation, the discussion below is structured around four analytically distinct groups of determinants: economic factors (vehicle price, purchase subsidies, tax reliefs, and operating costs), technical and infrastructural factors (charging availability, charging time, and driving range), environmental factors (ecological associations and environmental concerns), and policy-related factors (regulatory measures and public support schemes). This categorization provides a consistent interpretative framework for the questionnaire’s design, results presentation, and inferential analysis. The findings suggest that economic and infrastructural factors exert the strongest influence on purchase intention, while technical constraints play a secondary role and environmental considerations function primarily as supportive rather than decisive motivations. Policy-related factors appear to affect adoption indirectly by shaping economic conditions and infrastructure development.

Gaining a higher share of the European Union’s electric vehicle market depends on several factors [33,34,35]. The available literature attempts to identify direct barriers to the growth of electromobility. At the same time, it emphasizes the most important areas, such as technological progress in battery design, production, service life, as well as recycling, access to charging points, efficiency, and connectivity to the power grid, effect on energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions, standardization of charging stations, infrastructure management, and also organizational readiness [16,17]. In the current market reality, consumer attitudes significantly influence the popularity of electric vehicles and contribute to their market success [9,20,36,37].

It is important to distinguish subjective perceptions reported by respondents from actual technological, infrastructural, or policy realities. For example, concerns about insufficient charging infrastructure reflect individual impressions and personal experiences within the sample rather than a comprehensive assessment of the national charging network. Similarly, respondents’ views regarding battery range or charging time represent expectations shaped by comparisons with conventional vehicles and do not necessarily correspond to current technological capabilities or future developments. Therefore, policy- or technology-related conclusions drawn in this manuscript should be understood as interpretations of respondents’ attitudes rather than normative evaluations of existing regulations or market conditions. This distinction helps to avoid overgeneralization and clarifies the scope of inference appropriate for the survey-based methodology used in this study.

In the present survey, over 50% of respondents are considering purchasing an electric vehicle. However, in the study by Lewicki et al. 2021 [38], that percentage was only 13. Financial support in the form of state subsidies, tax breaks, and free parking spaces in cities would be more encouraging for the purchase of this type of car. Studies by other authors [38,39,40] assert that the price of electric vehicles also plays a significant role in the mass use of electric vehicles, especially in the context of the purchasing power of money and the economic conditions in Poland. Similar conclusions were reported in a Croatian study, in which respondents maintained that the current policy aimed at encouraging the Croatian government to adopt electromobility was insufficient, and that the infrastructure for electric vehicles was very poor. Inadequate infrastructure may also prove to be a significant problem in relation to the year of cessation of combustion motor vehicles specified by the EU [27]. Another important fact is the steadily growing awareness of the availability of electric vehicles, the advantages of their use, and how their broader use can be encouraged through infrastructural investments [29].

In the context of Poland’s policy environment, the findings have direct implications for national and local stakeholders. The financial incentives preferred by respondents (tax reliefs and operational subsidies) align with the EU’s broader decarbonization agenda, particularly the Fit for 55 package [41], which anticipates the accelerated phase-out of ICE vehicles. For Poland, this suggests prioritizing cost-reducing instruments and simplified access to funding schemes, alongside investments in public charging infrastructure to offset consumer concerns about availability and charging times [42]. Strengthening communication on battery sustainability and the origins of electricity generation could also help bridge the gap between policy goals and consumer perceptions. The results should also be interpreted in the context of Poland’s EV market maturity, which remains at an earlier stage compared with Western Europe [43]. Poland exhibits a lower density of public charging infrastructure, a higher share of rural population, and a market structure dominated by used-car imports. These conditions shape consumer expectations differently than in Norway [44], Germany, or the Netherlands [45], where EV adoption is more advanced and supported by long-standing incentive schemes.

The demographic profile of our sample—young, urban, and technologically engaged—also reflects the early adopter segment typical of emerging EV markets. Therefore, the findings align more closely with consumer attitudes in early stage markets rather than fully developed ones. A noteworthy finding is the coexistence of strong ecological associations with electric vehicles and simultaneous skepticism toward ecology as an actual purchase motivator. This ambivalence likely reflects broader public debates in Poland concerning the real environmental footprint of EVs, especially given the country’s still coal-dominated energy mix and uncertainties regarding battery recycling [19,46]. Such conflicting narratives may weaken the persuasive power of environmental arguments [47]. For policymakers and marketers, this suggests that ecological messaging alone may not be sufficient; instead, communication strategies should combine environmental benefits with practical advantages, such as cost savings, reliability, and operational convenience. Studies also show that ecological messaging alone is insufficient without complementary communication on cost, reliability, and convenience [48,49].

Consumer behavior concerning the automotive market has long been the subject of research. The scholarly discourse on consumer behavior demonstrates a notably growing interest in this issue, especially in the research on electromobility [9,36,37]. Doubtless, the use of electric vehicles is becoming an imperative to reduce GHG emissions [22]. However, a more widespread use of electric vehicles may be hindered by insufficiently formulated government policies, as well as the slow pace of adjusting the infrastructure to the needs of charging electric vehicle batteries [50].

This study has several limitations. First, the sampling strategy relied on a convenience sample of EV-interested Facebook users, which introduces a positive attitudinal bias and limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the relatively small sample size (n = 103) constrains the statistical power of more advanced multivariate analyses, such as regression modeling. Third, the study relies on self-reported perceptions, which may not fully reflect objective market realities or technological conditions. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings and designing future research.

5. Conclusions

Nowadays, electric vehicles are experiencing a renaissance. Their sales are increasing year by year in terms of the total number of cars sold, and automotive companies are withdrawing from the production of combustion cars. This study examined the determinants influencing consumer decisions regarding electric vehicle adoption in Poland, focusing on perceived economic, technical, and environmental factors. The results indicate that financial considerations—particularly vehicle price and the availability of incentives—constitute the most salient drivers of purchase intention, while limited charging infrastructure and concerns related to driving range and charging time remain major perceived barriers. Although respondents commonly associate electric vehicles with ecological benefits, environmental motives alone were not strong predictors of adoption, reflecting a pattern documented in international research.

The findings should be interpreted within the specific context of the survey sample, which consisted of individuals already interested in electric vehicles and was skewed toward younger and highly educated users. Consequently, the results reflect the perceptions of an early adopter subgroup rather than the broader population of Polish consumers. Nonetheless, these insights provide valuable evidence on the attitudes of a key segment likely to shape early market dynamics. Several implications emerge for policymakers and industry stakeholders. In line with EU decarbonization objectives, including the Fit for 55 package, measures aimed at reducing upfront costs and expanding the charging network appear central to stimulating demand. Moreover, communication strategies may need to balance ecological narratives with transparent information on technological capabilities, battery sustainability, and operational cost advantages. The study contributes to the literature by situating the Polish case within the wider international landscape of EV adoption research, confirming the predominance of economic over environmental motivations while also identifying ambivalence in consumer perceptions regarding ecological benefits.

Future research could expand on these findings by employing larger and more diverse samples, integrating longitudinal data, and utilizing multivariate models to explore causal pathways between perceptions, socio-demographic characteristics, and behavioral intentions. Further comparative analyses across Central and Eastern European markets would also enhance the understanding of EV adoption in emerging contexts. Overall, the present study offers an empirically grounded and contextually informed perspective on consumer attitudes toward electric vehicles in Poland, contributing both to academic debates and to the formulation of evidence-based policy interventions. By explicitly linking consumer perceptions to economic, infrastructural, environmental, and policy-related determinants, this study responds to calls in the literature for more structured and empirically grounded analyses of EV adoption in emerging European markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.-B. and P.S.; methodology, R.M.-B.; software, S.B., K.K. and P.W.; validation, S.B. and P.W.; formal analysis, R.M.-B.; investigation, R.M.-B. and P.S.; data curation, R.M.-B. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.-B. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, R.M.-B., S.B., K.K. and P.W.; visualization, P.S., K.K. and S.B.; supervision, S.B. and R.M.-B.; project administration, S.B. and R.M.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gnann, T.; Plötz, P.; Kühn, A.; Wietschel, M. Modelling market diffusion of electric vehicles with real world driving data—German market and policy options. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 77, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnyk, I.; Hulak, D.; Jakuszew, O.; Jakuszewa, O.; Prokopenko, O.V.; Jewdokimow, A. Development of the US electric car market: Macroeconomic determinants and forecasts. Energy Policy J. 2020, 23, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwick, P.J.; Kwon, H.S.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zahur, N.B. Industrial Policies and Innovation: Evidence from the Global Automobile Industry; NBER Working Paper No. 33138; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w33138/w33138.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Xie, T. The impact of policy thematic differences on industrial development: An empirical study based on China’s electric vehicle industry policies at the central and local levels. Energies 2024, 17, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaino, R.; Ahmed, V.; Alhammadi, A.M.; Alghoush, M. Electric vehicle adoption: A comprehensive systematic review of technological, environmental, organizational and policy impacts. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Hao, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Bouchard, J.; He, X.; LaClair, T.J. Light-duty plug-in electric vehicles in China: An overview on the market and its comparisons to the United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, E.; Davies-Shawhyde, J.; Turrentine, T. New Car Dealers and Retail Innovation in California’s Plug-in Electric Vehicle Market; Working Paper UCD-ITS-WP-14-04; Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt9x7255md/qt9x7255md_noSplash_eda8065ee88034a7e30519afe73d3e4c.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Tromaras, A.; Aggelakakis, A.; Margaritis, D. Car dealerships and their role in electric vehicles’ market penetration—A Greek market case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.-N.; Bekhet, H.A. Exploring factors influencing electric vehicle usage intention: An empirical study in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Manocha, S.; Saini, P. A study on an automobile revolution and future of electric cars in India. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Girin, V.; Girin, I. The current state of electric vehicles and its prospects in Ukraine. Min. Bull. 2017, 102, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gorova, K.; Sheverdina, A. The actuality of electric cars usage in Ukraine. Probl. Prospect. Entrep. Dev. 2015, 3, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, M. Post-COVID-19 electric vehicle market in Poland: Economic-based determinants. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H 2024, 58, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, J.; Hadasik, B. Segmentation of passenger electric cars market in Poland. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, P.; Focas, C. Factors affecting the uptake of hybrid and electric vehicles in the European Union. Energies 2019, 12, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, M.; Bernstein, P.; Wee, S. Electric vehicles revisited: A review of factors that affect adoption. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Wilberforce, T.; Alkhalidi, A.; Salameh, T.; Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Sayed, E.T. Battery electric vehicles: Progress, power electronic converters, strength (S), weakness (W), opportunity (O), and threats (T). Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 16, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, M.; Jackowski, J.; Jurecki, R.S.; Szumska, E.M.; Zdanowicz, P.; Żmuda, M. Electric vehicles—An overview of current issues—Part 1—Environmental impact, source of energy, recycling, and second life of battery. Energies 2024, 17, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Z.Y.; Qing, S.; Ma, J.J.; Xie, B.C. What are the barriers to widespread adoption of battery electric vehicles? A survey of public perception in Tianjin, China. Transp. Policy 2017, 56, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Rosenberger, J.M.; Hladik, G. Evaluation of barriers to electric vehicle adoption: A study of technological, environmental, financial, and infrastructure factors. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 22, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Christidis, P. Measuring cross-border road accessibility in the European Union. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; Beckmann, S.C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I.; Gwozdz, W. A self-identity based model of electric car adoption intention: A cross-cultural comparative study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hu, Y. The decision-making processes for consumer electric vehicle adoption based on a goal-directed behavior model. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, G. Polscy konsumenci wobec samochodów elektrycznych. Mark. Rynek 2024, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, G.; Adarsh, A. Customer Perceptions and Adoption Barriers of Electric Vehicles in India. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2024. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1901643/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Mutavdžija, M.; Kovačić, M.; Buntak, K. Assessment of selected factors influencing the purchase of electric vehicles—A case study of the Republic of Croatia. Energies 2022, 15, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V. Financial incentives for promotion of electric vehicles in India—An analysis using the environmental policy framework. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2022, 21, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Khanali, M.; Demirbas, A. A comprehensive review on the environmental impacts of diesel/biodiesel additives. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 174, 579–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrúcaný, T.; Kendra, M.; Stopka, O.; Milojević, S.; Figlus, T.; Csiszár, C. Impact of the electric mobility implementation on the greenhouse gases production in Central European countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucki, K.; Orynycz, O.; Świć, A.; Mitoraj-Wojtanek, M. The development of electromobility in Poland and EU states as a tool for management of CO2 emissions. Energies 2019, 12, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veum, K.; Bauknecht, D. How to reach the EU renewables target by 2030? An analysis of the governance framework. Energy Policy 2019, 127, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Rao, R.; Liang, Y. Policy incentives for the adoption of electric vehicles across countries. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8056–8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, I.; Campillo, J. Adoption barriers for electric vehicles: Experiences from early adopters in Sweden. Energy 2017, 120, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauf, K.; Pfahl, S.; Degenkolb, R. Taxation of electric vehicles in Europe: A methodology for comparison. World Electr. Veh. J. 2018, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I. Personal values, green self-identity, and electric car adoption. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahwish, A.; Khan, H.; Shakeel, A.; Thalassinos, I.E. The antecedents of consumer eco-friendly vehicles purchase behavior in United Arab Emirates: The roles of perception, personality innovativeness and sustainability. Int. J. Appl. Eng. 2020, 14, 343–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, W.; Drożdż, W.; Wróblewski, P.; Żarna, K. The road to electromobility in Poland: Consumer attitude assessment. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridstrøm, L.; Østli, V. Direct and cross-price elasticities of demand for gasoline, diesel, hybrid, and battery electric cars: The case of Norway. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansino, J.M.; Sánchez-Braza, A.; Sanz-Díaz, T. Policy instruments to promote electro-mobility in the EU28: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. EU Ban on the Sale of New Petrol and Diesel Cars from 2035 Explained. 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20221019STO44572/eu-ban-on-sale-of-new-petrol-and-diesel-cars-from-2035-explained (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ministry of Energy. Electromobility Development Plan in Poland; Ministry of Energy: Warsaw, Poland, 2016.

- Künle, E.; Minke, C. Macro-environmental comparative analysis of e-mobility adoption pathways in France, Germany and Norway. Transp. Policy 2022, 124, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, T.A.; Hasan, S. Policy measures for electric vehicle adoption: A review of evidence from Norway and China. Econ. Policy Energy Environ. 2020, 1, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.D.; Brungard, E. Consumer adoption of plug-in electric vehicles in selected countries. Future Transp. 2021, 1, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breetz, H.; Mildenberger, M.; Stokes, L. The political logics of clean energy transitions. Bus. Polit. 2018, 20, 492–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.R.; Gausen, O.M.; Strømman, A.H. Environmental impacts of hybrid and electric vehicles—A review. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppers, E.H.; Keizer, K.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. The adoption of sustainable innovations: Driven by symbolic and environmental motives. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 25, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Anable, J.; Nelson, J.D. Consumer structure in the emerging market for electric vehicles: Identifying market segments using cluster analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2017, 11, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.; Harichandan, S.; Kar, S.K.; Sreejesh, S. An empirical study on consumer motives and attitude towards adoption of electric vehicles in India: Policy implications for stakeholders. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.