Abstract

Building energy renovation planning should be based on a multi-criteria evaluation that targets both reduced energy consumption and a high-quality indoor thermal environment. The present study investigates the building energy retrofit technologies of thermal insulation, highly insulative windows, mechanical ventilation for cooling purposes, and shading, aiming to identify the optimum energy retrofit strategy for different building typologies. Indoor thermal comfort is evaluated with the thermal comfort indexes of the predicted mean vote (PMV) and the Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD). Each renovation scenario is evaluated in terms of thermal performance and thermal comfort, while an optimum retrofit scenario is defined as the one that simultaneously achieves the maximum decrease in the yearly energy demand and the greatest decrease in the building’s indoor thermal discomfort. The multi-objective analysis is performed using the EnergyPlus simulation engine, which is used to perform yearly dynamic simulations and provide accurate results. This study considers a typical one-story apartment building located in the city of Athens, Greece. According to the calculations, the retrofit strategy that combines all four examined interventions results in an 11.8% and 56.1% decrease in the building’s heating and cooling energy demand, respectively, while an annual enhancement of 16.6% in the building’s thermal comfort PPD index is calculated.

1. Introduction

To achieve low energy consumption and a high-quality occupancy experience, a building’s energy performance and indoor thermal environment are examined in combination. Thermal comfort is the state of being satisfied with a building’s thermal environment, allowing occupants to remain comfortable without adjusting conditions [1]. Unfortunately, the continuous rise in energy prices, coupled with inflationary pressures in the consumer goods and services market, persistently erodes household financial stability, putting them at risk of energy poverty [2]. Combined with the increasing phenomena of cold and, especially, hot extremes, a severe threat to human health has arisen.

Maintaining healthy and comfortable living conditions should not come at the expense of reducing energy consumption in buildings. Implementing passive building envelope retrofit technologies results in the mitigation of a building’s energy consumption, as well as in the enhancement of its indoor environment [3]. Thermal insulation is a conventional retrofit measure that is reported to mitigate both energy consumption and thermal comfort dissatisfaction in buildings [4]. Moreover, according to a study by Hu et al. [5], the implementation of passive cooling retrofit techniques that relate to a building’s window systems and the incoming solar irradiation is crucial to a building’s indoor air temperature distribution and cooling thermal loads. The installation of fixed, external shading elements on a building’s glazing components is currently the predominant solution for mitigating solar heat gains and enhancing visual comfort [6]. Additionally, the installation of a mechanical ventilation system for cooling purposes can effectively decrease a building’s cooling energy demand and enhance its indoor thermal comfort conditions [7]. However, the standalone implementation of mechanical ventilation systems cannot sufficiently meet the energy and thermal comfort requirements in hot Mediterranean climates [8] and therefore should be implemented as part of an expanded building energy renovation strategy.

The most common type of residence in the Greek building sector is located in multi-family buildings, and, as a result, apartment-type dwellings account for up to 44.7% of the total residential building stock [9]. Approximately two-fifths of these residencies are characterized by the absence of insulation, while up to 56% of them were built before 1980 [9]. The European goals on zero-energy buildings and low carbon footprint highlight [10] the urgent need for deep and holistic renovation strategies, which shield residencies against escalating frequency weather extremes [11]. However, just over 3% of the country’s residences have been retrofitted.

The thermal upgrade of a building’s thermal envelope properties is an efficient way to mitigate high energy consumption for heating and cooling. Both transparent and opaque building elements are crucial for the high energy performance and satisfactory indoor thermal environment of a building [12]. Global warming and rising air temperatures result in warmer climatic conditions and elongated cooling periods, and, therefore, in the need to adapt primarily cooling energy-intensive retrofit actions [13]. The Greek building sector is constructed with high-density load-bearing reinforced concrete and brick walls. Applying high thermal resistive technologies that include thermal insulation and highly insulative windows is necessary for the increase in the building’s thermal inertia and, therefore, effective thermal regulation. Additionally, due to the high solar irradiation potential of Mediterranean climates, retrofit actions that seasonally control solar heat gains [14] and passive aeration for cooling can result in important energy savings [15]. The level of solar exposure of the rooftop and external walls of building elements is an important parameter in the design of effective energy renovation strategies [16].

Building energy renovation techniques need to balance cost-effectiveness with a broad potential for application across various building geometries [17]. The technologies examined in this study do not present any limitations regarding a building’s geometry and location. The efficiency and suitability of a renovation planning scheme are a multifaceted process based on multiple indicators [18]. In a study by Martins et al. [19], the transformation of a residential building into a zero-energy building is performed using dynamic energy calculations in the EnergyPlus software and the use of the passive building envelope technologies of insulation, low infiltration windows, and shading. The efficiency of the renovation is measured both in terms of energy savings and thermal comfort improvement. In a study by Yuk et al. [20], various insulating materials and their impact on s building’s thermal performance are examined. They calculated that thermal insulation results in heating energy savings of 11% to 26%, but it can result in an increase in cooling energy demand due to thermal inertia. Additionally, in another study by Yuk et al. [21], double-glazed window replacement is proven to be an energy-efficient renovation technique that improves the building energy performance during the cooling season by 17%, and leverages airtightness to reduce heat losses during the heating season, resulting in 24% heating energy savings.

Wang et al. [22] underline that the enhancement in the building’s electrical equipment is of equal significance to improving a building’s thermal performance. In the dynamic and asymmetrically thermally burdened indoor environments of buildings, the addition of mechanical ventilation systems [23] and window shading [14] is catalytic to indoor thermal comfort. A mechanical ventilation system can be used as a cooling technique serving ventilative cooling. A common approach is night ventilation, which takes advantage of the ambient air temperature drop during the night and increases the air renewal rate. According to an optimization study by Zhang et al. [24], regarding mechanical ventilation in office rooms in Beijing, cooling energy savings mainly derive from the system’s night operation and the subsequent load shifting effect. The energy savings during the summer period are found to result in up to 47%. Additionally, in a study by Motuzienė et al. [25], regarding an office building located in Vilnius, Lithuania, the occupancy schedules are identified as a significant parameter of the ventilation rate, which can result in a 30.0% decrease in electricity consumption.

Static shading elements are identified as the most popular commercially available passive envelope solutions in the building sector [26] due to their low maintenance cost [27]. In a study by Méndez et al. [28], the application of a fixed shading element is found to improve the building energy performance under hot climatic conditions, resulting in a thermal discomfort alleviation in non-air-conditioned residences by over 70% and an energy consumption reduction for space cooling of up to 30%. In a study by Shah et al. [29], static shading techniques are combined with cool paints for multiple climatic conditions. According to their calculations, façade shading alone can result in cooling energy savings from 8.0% to 28.0%, while combining shading and cool coatings can increase savings to 10.0% and 40.0%.

A thermally neutral indoor environment is a subjective definition, determined by multiple health and physical parameters [30]. Multiple thermal comfort evaluation models are continually being developed using different regression models and sampling inspections. Fanger’s thermal comfort model is categorized among the oldest and most widely recognized ones, based on a foundational approach for analyzing thermal conditions [31]. This model incorporates the six key factors of air dry-bulb temperature, radiant temperature, air velocity, humidity ratio, occupants’ metabolic rate, and clothing insulation to compute generalized thermal comfort indices based on the ASHRAE [1] thermal sensation scale.

The objective of this analysis is to simultaneously assess energy-efficiency savings and thermal comfort enhancements from various renovation actions, applied individually and in combination, in a typical residential building. The selected renovation actions to be investigated include thermal insulation, highly insulative windows, mechanical ventilation for cooling, and shading. The importance of this study lies in the systematic assessment of various building envelope renovation technologies applicable across multiple building topologies. The study aims to identify the most effective renovation strategies from two perspectives, energy efficiency and thermal comfort, and to offer guidelines on the overall benefits of renovation procedures. The methodological insight of this study is prioritization in the application of fundamental retrofit technologies and is performed using the multi-objective evaluation tool and key criteria of energy performance and thermal comfort improvement. The present study presents a systematic evaluation process of selected retrofit technologies, applied either individually or in combination, providing an in-depth assessment of all possible retrofit strategies for residential buildings and finally identifying the most efficient ones in terms of seasonal and annual energy performance and thermal comfort. For this purpose, the simulation engine EnergyPlus is used, and the case study investigated is of the most common type of Greek residencies, apartments, for the Mediterranean representative climatic condition of Athens, Greece. The conclusions of this work provide valuable insight into the performance of various heating or cooling energy-intensive retrofit solutions, offering a clear ranking in terms of energy saving and thermal comfort, two crucial factors for residential buildings. Finally, the outputs of the study can be utilized as an asset for future renovation solutions, supporting sustainable urban design, reducing energy consumption, and promoting energy sufficiency in the building sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Building

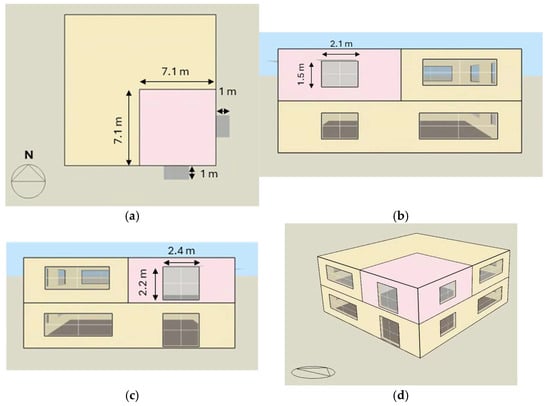

The present case study regards a single-level dwelling with a total floor area of 50 m2 and an interior ceiling height of 3 m, located in Athens, Greece. The building envelope includes partial thermal insulation and is only partly exposed to outdoor environmental conditions. Specifically, the southern and eastern façades, along with the roof, are directly exposed to the external environment, whereas the remaining envelope components adjoin neighboring residential apartments that are conditioned. As a result, these common structural elements are modeled under adiabatic boundary conditions. Fenestration is distributed unevenly across the façades, with glazing accounting for 25% of the southern wall area and 15% of the eastern wall area. The absorbance and emittance of the external surfaces are selected to be 60% [32] and 80%, respectively [33]. The studied building and its basic dimensions are illustrated in Figure 1 and are highlighted in pink color.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the examined residency highlighted with a pink-colored coating. (a) Plan view, (b) west-side, (c) south-side, and (d) axonometric view.

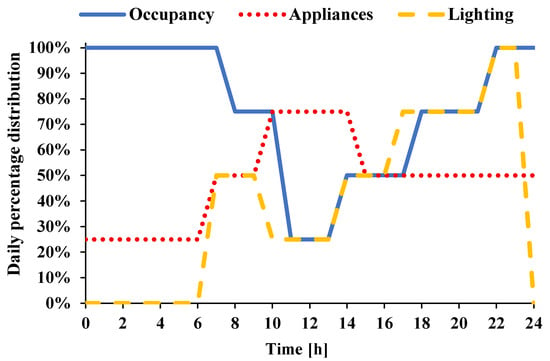

The studied building is constructed with brick walls and a reinforced concrete load-bearing frame. For the baseline scenario, the U-value of the external walls is chosen at 0.682 W/(m2·K) and of the roof at 0.629 W/(m2·K). The openings are covered with double-glazed windows, which present a thermal transmittance of 2.5 W/(m2·K) and a g-value of 80%. Table 1 includes the thermal and optical properties of the construction materials. The building has two residents with a thermal load of 80 W per person and a mean occupancy of 75% [33], while the infiltration rate is chosen at 0.8 ach [34]. The specific load of the lighting is selected at 2 W/m2 and the average operating fraction at 39% [33], while the specific load of the appliances is at 3 W/m2 and the average operating fraction at 48% [34]. These values are aligned with the Technical Guidelines of the Technical Chamber of Greece [33] and the typical operation of residential buildings. Table 2 summarizes the building’s geometric and operational data and Figure 2 illustrates the daily percentage distribution profiles of occupancy, appliances, and lighting for the examined residency. During the midday hours, the appliance operation ratio increases despite the low occupancy rate, mainly due to cooking activities, domestic hot water use, and associated kitchen appliance and ventilation demands. The building is fully electrified and equipped with split units to meet its heating and cooling load requirements. The air-sourced heating and cooling system is characterized by a seasonal coefficient of performance of 4.0 and 4.5, for the heating and cooling operations, respectively [35], and a nominal efficiency of 12,000 BTU/h. The temperature setpoint level for the heating and cooling periods are set to 20 °C and 26 °C, respectively.

Table 1.

Thermal and optical properties of building materials.

Table 2.

Geometric and operational data of the residence.

Figure 2.

Daily percentage distribution profile of occupancy, appliances, and lighting for the examined residency.

2.2. Description of Examined Scenarios

For the formulation of the various renovation scenarios, four different passive envelope retrofit technologies are investigated, either individually or in combination. The selected interventions concern the thermal upgrading of the building’s opaque and transparent elements, the reduction in the solar heat gains, and the additional aeration via mechanical ventilation for cooling. These solutions are cost-effective and, when combined, form a comprehensive strategy that addresses the main energy-consuming aspects of residential buildings. Specifically, the investigated building energy renovation technologies include the installation of the following:

- (i)

- 6 cm of thermal insulation with thermal conductivity of 0.031 W/(m·K) [36] on the building’s envelope external surfaces. The new mean thermal transmittance value of the building envelope is calculated at 0.289 W/(m2·K), a value which is in accordance with the literature data [37,38] regarding renovated thermal envelope practices for the climatic conditions of Athens.

- (ii)

- Triple-glazed argon-filled low-e windows with a total U-value of 1.1 W/(m2·K) [14] and a g-value of 0.65 [37].

- (iii)

- Mechanical ventilation for cooling with a summer-period operation and an internal minimum air temperature setpoint of 24 °C [39] and an external maximum air temperature setpoint of 26 °C, increasing the air change rate by up to 1.0 ach. More specifically, the mechanical ventilation system is activated only when the indoor air temperature is over 24 °C and the ambient air temperature is under 26 °C, meaning that it does not surpass the setpoint temperature of 26 °C the cooling period.

- (iv)

- External static horizontal shading elements, 1 m in length [40] and equal to the width of the building’s windows.

All possible combinations of the examined retrofit actions yield 15 distinct renovation scenarios, as shown in Table 3. The scenarios are labeled with two numbers: the first indicates the number of renovation actions in the scenario, and the second identifies the scenario itself. Specifically, four scenarios examine the four renovation actions of thermal insulation (Ins), triple-glazed agon-filled low-e windows (Win), a mechanical ventilation system for cooling (Vent), and horizontal external shading elements to windows (Shad), as standalone retrofit interventions. Also, six two-intervention renovation scenarios, four three-intervention renovation scenarios, and one four-intervention renovation scenario are investigated. Including the baseline scenario, there are 16 scenarios in total. Each renovation scenario is compared with the baseline to calculate energy savings and thermal comfort improvements.

Table 3.

Description of renovation scenarios.

2.3. Simulation Strategy

The energy and thermal comfort calculations are performed using the DesignBuilder software [41] and the EnergyPlus v24.2.0 simulation program [42]. The timestep is set to 5 min based on a sensitivity analysis. This analysis determines the maximum allowable timestep that balances low computational cost with high calculation accuracy. Additionally, the TARP (Thermal Analysis Research Program) algorithm [43] is selected to calculate the indoor and outdoor convective heat transfer coefficients. The TARP algorithm is a comprehensive model for exterior convection that combines correlations from ASHRAE [44]. The comparative simulation analysis is performed for the climatic conditions of Athens, Greece [37°58′54″ N, 23°43′51″ E], retrieved from the DesignBuilder weather library. In Athens, the ambient air temperature ranges from 2.0 °C to 37.0 °C, while the average annual air temperature is 18.0 °C. The heating period lasts from November to the middle of April, while the cooling period is between the last days of May and the middle of September. The location is characterized by a high level of annual solar horizontal irradiation of 1800.3 kWh/m2 [45]. From April until September, the monthly solar horizontal irradiation ranges between 162.0 kWh/m2 and 244 kWh/m2.

2.4. Basic Equations

The investigation of the renovation scenarios is based on the evaluation metrics of energy savings and thermal comfort indices. Specifically, the annual heating energy savings are calculated as follows:

The annual cooling energy savings are calculated as follows:

The index of predicted mean vote (PMV) is calculated as a deviation of an occupant’s total specific heat loss (L) from its specific metabolic rate (M), as described below [46]:

This equation, known as the thermal comfort equation, is based on a regression analysis of steady-state experimental data. Fanger’s model evaluates thermal sensation based on the degree of deviation from the ideal thermal comfort state. The Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD) is found according to the following equation as follows [46]:

For the calculation of the PMV and PPD indexes, the occupants’ metabolism is set to 58 W/m2 [47], which is representative of typical residential indoor activities, such as sitting, reading, or light household tasks, as defined in ISO 7730 [48] and ASHRAE 55 [1]. Additionally, the thermal insulation of occupants’ clothes varies between 1.0 clo or 0.2325 (m2·K/W) for the winter period and 0.5 clo or 0.0775 (m2·K)/W for the summer period [49]. These values are commonly used in residential thermal comfort studies and are consistent with international standards.

The multi-objective evaluation of the different retrofit strategies aims at the minimization of heating and cooling energy demand, denoted as Etotal and the minimization of the PPD index. For this end, the dimensionless geometric distance from the ideal solution is calculated for every retrofit strategy, according to the following equation:

The global optimum solution minimizes F and the ideal point corresponds to the minimum yearly energy demand for the heating and cooling and minimum PPD index (Etotal,min, PPDmin), while any examined scenario can be represented by the point (Etotal, PPD). Each term in Equation (5) is normalized by the corresponding maximum range observed among the examined scenarios, enabling a dimensionless analysis that assigns equal weight to both indices (Etotal and PPD). Consequently, each normalized term varies between 0 and 1, while the parameter F ranges between 0 and .

The apartment’s mean indoor carbon dioxide concentration is calculated using the Generic Contaminant model implemented in EnergyPlus [50]. This approach determines the net contaminant source strength in the zone by accounting for both time-varying generation and removal processes. The governing equation is the following [50]:

where (t) is the generic contaminant source strength measured in [m3/s], (t) is the generic contaminant generation rate in [m3/s], and is the source fraction, which is specified through a time-dependent schedule that follows the occupancy presence. Moreover, the removal term is represented by (t), which stands for the effective contaminant removal rate, given in [m3/s], scaled by the contaminant concentration (t) from the previous simulation time step, expressed in parts per million (ppm). The concentration is converted to a volumetric fraction using the factor 10−6. The sink fraction FR, defined by a schedule that follows the zone’s ventilation and infiltration rate, modulates the removal process.

For the calculation of the simple payback period (SPP), in years, of a retrofit strategy, the following equation is used [51]:

where C0 is the investment cost of the retrofit and Pel is the aggregated heating and cooling electricity consumption load, in W. The electricity price is denoted with kel and for residential use is assumed to be equal to 0.282 EUR/kWh [52].

3. Results and Discussion

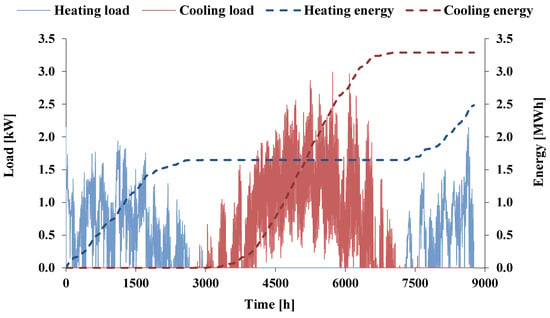

3.1. Baseline Scenario Dynamic Analysis

Firstly, the baseline scenario is investigated. According to Figure 3, the yearly heating energy demand is calculated at 2483 kWh, while the cooling energy demand is at 3290 kWh. The maximum heating load is 2.41 kW on the 27th of December, and the maximum cooling load is 2.99 kW on the 26th of August. The building is described as cooling energy-intensive, which is justified by the fact that both its rooftop and south wall are exposed to solar irradiation, and therefore, the amount of solar heat gain is an important part of the building’s energy equilibrium.

Figure 3.

Heating and cooling hourly load and cumulative energy demand for the baseline scenario.

3.2. Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Renovation Scenarios

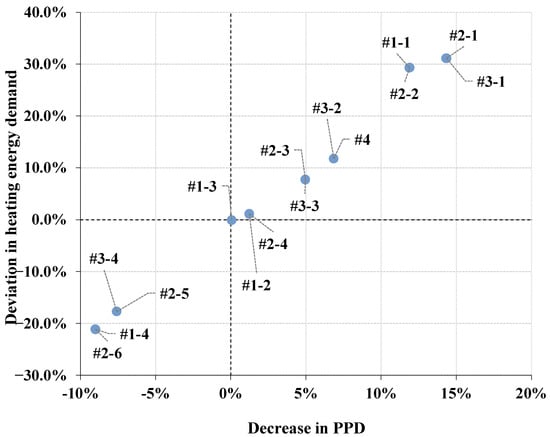

Following that, the multi-criteria evaluation of the 15 different renovation scenarios is performed. Firstly, the renovation scenarios are compared in terms of heating energy savings and decrease in the PPD index during the heating period, as illustrated in Figure 4. The renovation scenarios that result in increasing the building’s heating energy demand and discomfort during the heating season are scenarios #1-4 (Shad), #2-5 (Win and Shad), #2-6 (Vent and Shad), and #3-4 (Win, Vent, and Shad). On the other hand, the most efficient renovation scenarios are calculated to be scenarios #2-1 (Ins and Win) and #3-1 (Ins, Win, and Vent), which are practically identical since the mechanical ventilation system only operates during the cooling season. The addition of thermal insulation and the replacement of windows is the optimum renovation strategy for heating purposes, calculated to result in a 31.1% reduction in the heating energy demand and a 14.4% decrease in the PPD index.

Figure 4.

Multi-criteria evaluation of the heating energy savings and the decrease in the PPD index for the heating period.

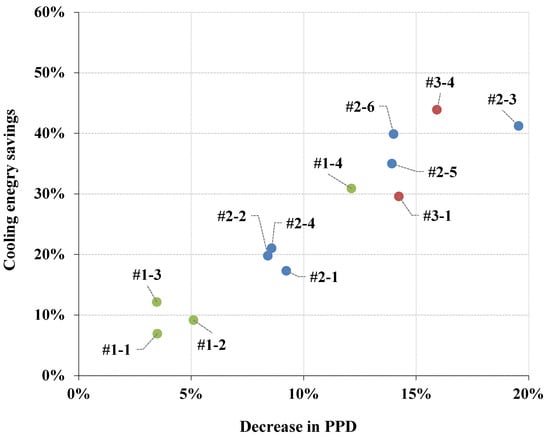

Regarding the cooling period, Figure 5 compares the renovation scenarios in terms of cooling energy savings and the decrease in thermal discomfort. The least effective renovation scenarios are the three one-intervention scenarios, #1-1 (Ins), #1-2 (Win), and #1-3 (Vent). Mechanical ventilation as a standalone retrofit action results in 12.2% cooling energy savings and a 3.5% decrease in the PPD index for the summer period. If combined with shading (#2-6), cooling energy savings equal 39.9%, and the decrease in PPD is 14.0%. Furthermore, the three-intervention scenario #3-3 (Ins, Vent, and Shad) results in 49.6% reduced energy demand and 22.1% better thermal comfort conditions. The optimum renovation scenario for cooling purposes combines all four retrofit technologies, resulting in 54.1% energy savings and a 24.4% enhancement in the summer indoor thermal comfort conditions.

Figure 5.

Multi-criteria evaluation of the cooling energy savings and the decrease in the PPD index for the cooling period.

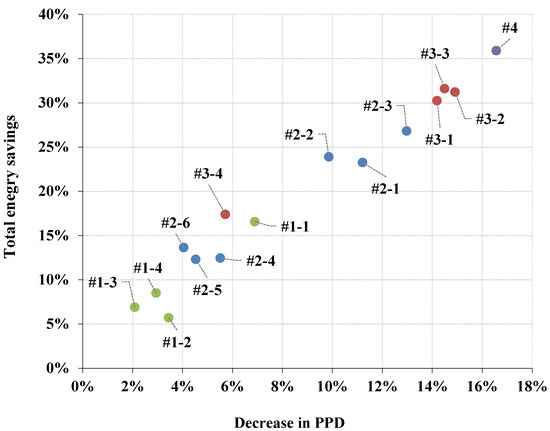

Finally, a multi-objective evaluation is performed comparing the renovation scenarios in terms of annual energy savings and decrease in discomfort. The results are illustrated in Figure 6. The one-intervention scenarios, #1-2, #1-3, and #1-4, are found to be the three least effective renovation strategies. The annual optimum renovation scenario involves all four retrofit technologies, resulting in yearly energy savings of 35.9% and a decrease in the PPD index equal to 16.6%. The second-best scenario is #3-2 (Ins, Vent, and Shad), with 31.2% energy savings and a 14.9% enhancement in thermal comfort. Based on graphical observation, the renovation scenarios are divided into two subgroups. The first subgroup reaches a maximum, with scenario #1-1, of 16.6% in energy savings and a 6.9% decrease in the PPD index. The second group outperforms the first one, scoring a minimum decrease of 23.9% in energy demand and 9.9% in the PPD index, which corresponds to scenario #2-2. It is important to notice that every renovation scenario that belongs to the second group involves the retrofit action of thermal insulation. The only exception is the one-intervention scenario #1-1, which belongs to the first group of less effective renovation strategies.

Figure 6.

Multi-criteria evaluation of the annual energy savings and the decrease in the PPD index.

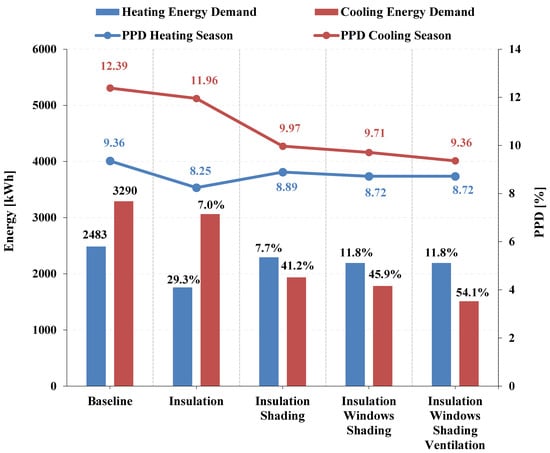

Based on the results of the multi-objective evaluation process, Figure 7 illustrates the annual energy demand and calculated PPD index for the optimum one-intervention (Ins), two-intervention (Ins and Shad), three-intervention (Ins, Win, and Shad), and four-intervention scenarios. This figure aids in prioritizing the implementation of renovation technologies, identifying thermal insulation as the top priority, followed by shading, windows, and, finally, mechanical ventilation systems for cooling. It is useful to state that the incorporation of insulation is vital for reducing the heating loads, while the addition of shading elements is the most important action for mitigating cooling energy loads. However, the application of shading and the restriction of the incoming solar irradiation during the winter period result in significant heating penalties. Therefore, a proper analysis is needed to balance the benefits and drawbacks of shading, a technique that is generally recommended for the climate conditions of Greece. Moreover, the multiple application of renovation actions is calculated to be more effective in improving a building’s indoor thermal comfort conditions. Specifically, the PPD index of the baseline scenario is found at 12.39% for the winter period and at 9.36% for the summer period, while for the four-intervention renovation scenario, it is reduced to 9.36% and 8.72%, respectively.

Figure 7.

Energy demand and PPD index of the annual optimum, one-, two-, three-, and four-intervention retrofit strategies.

3.3. Detailed Analysis of the Optimum Renovation Scenario

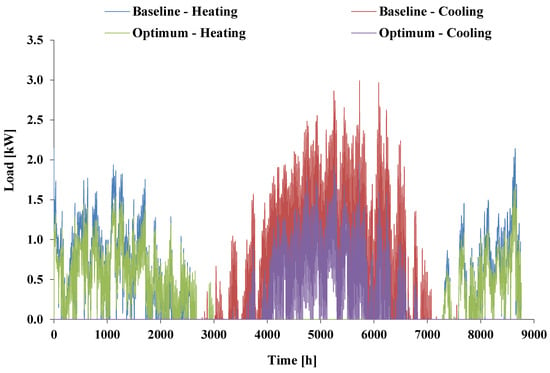

The global optimum retrofit scenario is characterized as the one with the maximum annual energy savings and the greatest decrease in indoor thermal discomfort. The combination of all four retrofit actions defines the optimal energy and thermal comfort renovation scenario. The energy analysis calculations of the baseline and the optimum renovation scenario are depicted in Figure 8. Specifically, the hourly heating and cooling loads for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios are given. According to the calculations, for the optimum renovation scenario, the maximum heating load is equal to 1.66 kW, a 22.6% decrease compared to the baseline scenario, while the maximum cooling load is calculated at 1.96 kW, a 34.6% reduction compared to the baseline scenario. The cumulative heating energy demand of the optimum scenario is found at 2191.1 kWh, a 11.8% reduction compared to the baseline scenario. Correspondingly, the cumulative cooling energy demand of the optimum scenario is found at 1509.5 kWh, a 54.1% reduction compared to the baseline scenario. Therefore, it is obvious that all the energy indices are enhanced through the application of all four renovation actions. Despite the application of cooling techniques, the addition of thermal insulation and high-performance window systems counterbalance the heating penalty induced by shading and finally result in heating energy savings.

Figure 8.

Comparison of heating and cooling loads for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios.

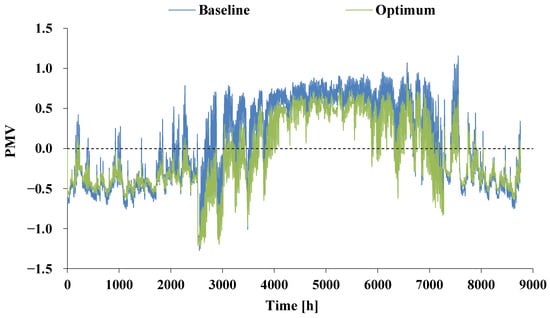

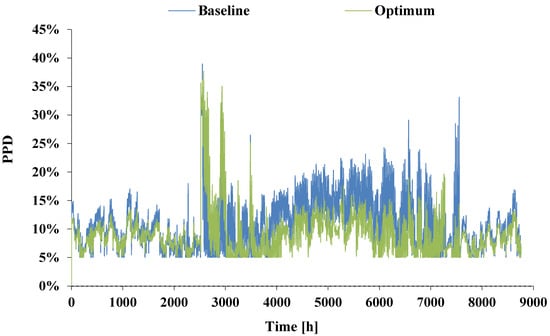

Finally, the hourly PMV and PPD index calculations for the baseline and four-intervention scenarios are given in Figure 9 and Figure 10. The enhancement in the indoor thermal environment is evident throughout the entire year, especially during the summer. During the middle of April and the end of October, the PPD index receives the highest values for both scenarios. These periods are characterized as transitional periods with very low heating or cooling loads, as shown in Figure 8. The high values of the PPD index can be attributed to the inappropriate selection of the light clothing input defined in this analysis. Despite this result, the four-intervention scenario demonstrates better thermal conditions, even during the transitional periods of the year. Specifically, according to the PMV calculations, the optimum scenario results in warmer indoor conditions (higher values of PMV) during the transitional period of spring, and, correspondingly, cooler indoor conditions (lower values of PMV) during the transitional period of autumn. Regarding the entire year, the average absolute deviation from the zero value of PMV, which corresponds to a thermally neutral indoor environment, is equal to 0.49 for the baseline and 0.40 for the optimum renovation scenario, resulting in a difference of 0.09.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the PMV index for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the PPD index for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios.

3.4. Indoor Air Quality Calculations for Baseline and Optimum Renovation Scenarios

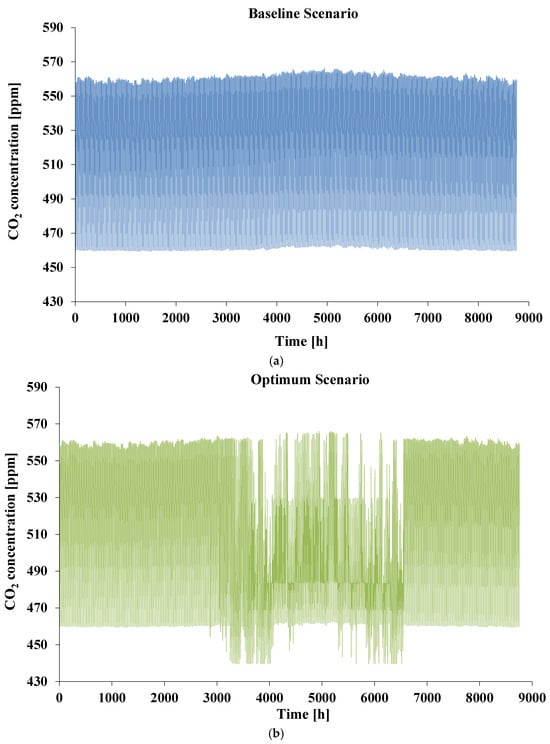

The baseline scenario and the optimum retrofit scenario are investigated regarding air quality. Specifically, the two indoor parameters calculated for both scenarios are the carbon dioxide concentration and relative humidity. Indoor air quality is directly linked to the outdoor air conditions, unless a mechanical ventilation system is installed that forces air renewal or purifies the air from contaminants through filters. Carbon dioxide concentration is examined in the case studied, which is directly linked to a healthy indoor environment and the appropriate air renewal rates. For outdoor air, the CO2 concentration is considered to be 425 ppm, based on the most recent global monthly average measurements reported by the Global Monitoring Laboratory [53]. The CO2 generation rate for residential purposes is considered to be 20 L/h, an average value for males and females corresponding to sitting and mild walking, as reported in the study by Li et al. [54].

The yearly carbon dioxide apartment’s mean indoor concentration for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios is depicted in Figure 11. The CO2 concentration ranges between 460 and 560 ppm, which meets the acceptable criteria for a healthy indoor environment. In the renovation scenario, adding the mechanical ventilation system reduces carbon dioxide concentration during summer operation. Specifically, during the summer period, the average carbon dioxide concentration for the optimum renovation scenario (504.4 ppm) is reduced by 4.6% compared to the baseline scenario (528.5 ppm).

Figure 11.

CO2 concentration for the (a) baseline and (b) optimum scenarios.

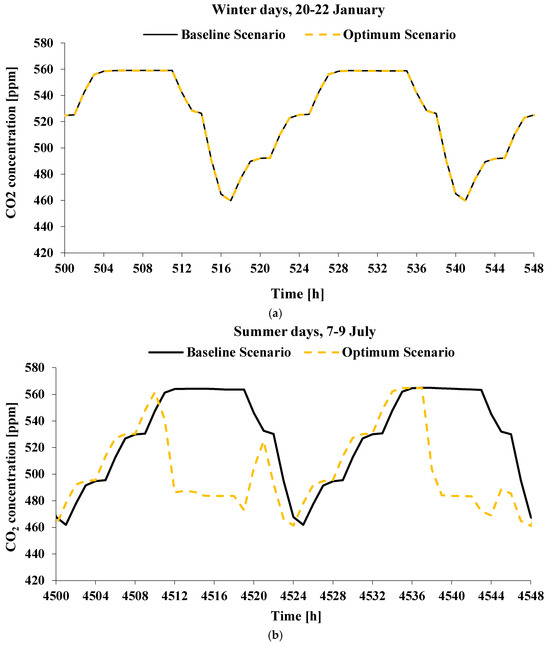

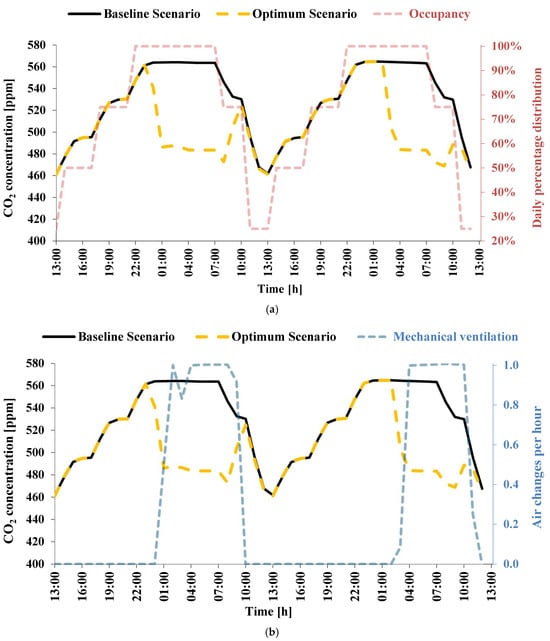

Figure 12 focuses on a typical two-day period for winter and summer, illustrating and comparing the carbon dioxide concentrations for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios. During the winter period, from 20:00 on 20 January to 20:00 on 22 January, the CO2 concentration distributions are identical; however, in summer, the optimum renovation scenario exhibits better air quality for some hours of the day. The carbon dioxide concentration is linked to the building’s aeration and the occupants’ presence. Figure 13a,b focus on the period from 13:00 on 7 July to 13:00 on 9 July and examine both the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios. Figure 13a compares the carbon dioxide concentration with the daily percentage distribution of occupancy, while Figure 13b compares the carbon dioxide concentration with the additional air changes per hour resulting from mechanical ventilation system operation, which range between 0 and 1 air changes per hour.

Figure 12.

Carbon dioxide concentrations for the baseline and optimum renovation scenario for two typical (a) winter and (b) summer days.

Figure 13.

Carbon dioxide concentration between the 7th and 9th of July for baseline and optimum renovation scenarios in contradiction to the (a) daily percentage distribution of occupancy and (b) mechanical ventilation additional air changes per hour.

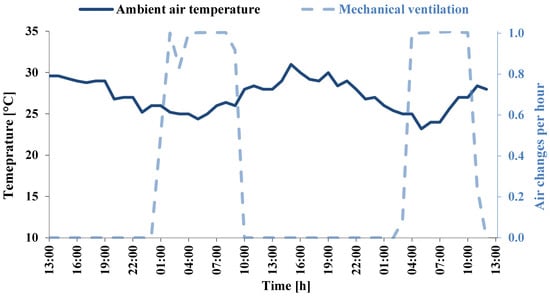

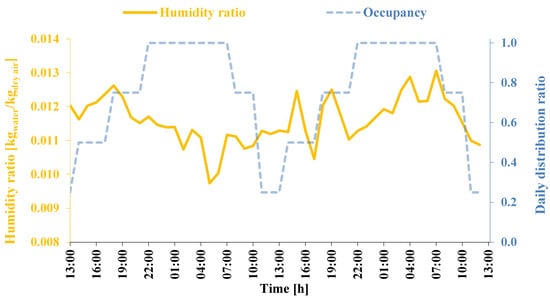

The operation of the mechanical ventilation systems is controlled by a maximum outdoor air temperature setpoint of 26 °C. Figure 14 depicts the additional air changes per hour introduced by the mechanical ventilation system from the 7th until the 9th of July, and the corresponding ambient air dry-bulb temperature. Figure 15 illustrates the humidity ratio of the indoor air for the same period and compares it with the occupancy distribution ratio. In general, the presence of occupants results in an increase in the indoor air humidity ratio due to the latent heat generated by respiration and sweating.

Figure 14.

Operation of the mechanical ventilation system in relation to the ambient and zone mean air temperature.

Figure 15.

Humidity ratio of indoor air for the optimum renovation scenario compared to the daily occupancy distribution ratio.

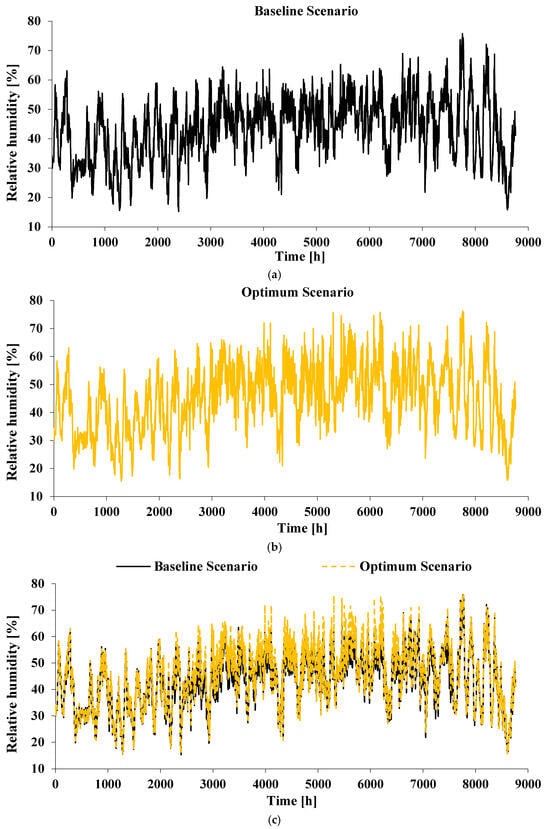

The calculations regarding the hourly relative humidity for the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios are presented. Figure 16 illustrates the yearly relative humidity for the baseline (Figure 16a) and optimum renovation scenario (Figure 16b). Compared to the baseline scenario, the optimum renovation scenario presents higher relative humidity during the summer period, as shown in Figure 16c. The increased air renewal rate due to the mechanical ventilation operation results in an average relative humidity during the summer period equal to 6.9%.

Figure 16.

Relative humidity for (a) baseline and (b) optimum renovation scenarios, and (c) both scenarios.

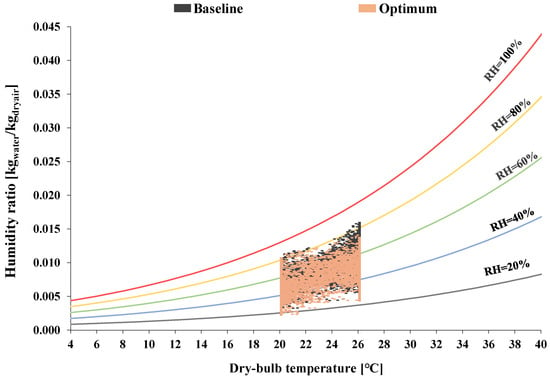

Finally, Figure 17 illustrates the psychrometric chart and the indoor air conditions for both the baseline and optimum renovation scenarios. The indoor air dry-bulb temperature is in the range of 20 °C and 26 °C, while the relative humidity is roughly between 20% and 70%. These values confirm that indoor thermal comfort conditions are within the desired comfort levels. These calculations also verify that the renovation scenario results in an increase in the indoor air relative humidity both in winter and summer.

Figure 17.

Psychrometric chart and indoor air operating conditions for the baseline and optimum retrofit scenario.

4. Discussion

The retrofit technologies investigated in this study aim to enhance the thermal performance of the building’s opaque and transparent elements, reduce solar heat gains, and increase the ventilation rate to dissipate the building’s cooling load. The combination of all four investigated technologies involves adding insulation to the outer surface of the building envelope, installing triple-glazed low-e windows, implementing mechanical cooling ventilation, and installing external static horizontal shading elements. This retrofit strategy results in a yearly aggregated electricity consumption for heating and cooling equal to 883.3 kWh, in comparison to the baseline scenario, for which it is equal to 1351.9 kWh. The optimum retrofit scenario primarily enhances the building’s thermal performance during the cooling period, achieving a 54.1% reduction in annual cooling energy demand, while the annual heating energy demand is reduced by 11.8%. The primary energy demand for the optimum retrofit scenario is calculated at 2561.6 kWh, compared to 3920.4 kWh for the baseline scenario, assuming a primary energy conversion factor for electricity of 2.9 for Greece [55].

The operational emissions are generated by the energy consumed during the building’s operation. For Greece, the CO2 emission factor for electricity is equal to 0.411 tnCO2/MWh [56]. Accordingly, the CO2 emissions resulting from electricity consumption for heating and cooling are calculated at 555.6 kg for the baseline scenario, and 363.1 kg for the optimum retrofit scenario, corresponding to a reduction of 34.7%. The superior performance of the optimum retrofit scenario is undeniable in terms of energy efficiency and thermal comfort. However, an economic evaluation is crucial to assess the feasibility and applicability of this strategy.

For the calculation of investment costs, the specific cost of EPS thermal insulation is 0.82 EUR/m2 per centimeter of insulation thickness according to present market trends in Europe [57]. For triple-glazed low-e windows, it is taken as 550 EUR/m2, according to Greek market trends for the technological provider of Kömmerling [58]. Finally, the capital cost of the mechanical ventilation system is EUR 1100 [59], and of external static horizontal shading elements is 60 EUR/m2 according to local market prices [60]. The methodology of the simple payback period takes into consideration current material and energy prices, reflecting the current economic profile of energy retrofit projects. However, it should be acknowledged that this methodology may result in underestimation or overestimation of the real economic performance of retrofit strategies throughout a project’s lifespan. Furthermore, the global economic volatility [61], and subsequent government practices on applying fixed seasonal energy tariffs to smooth variabilities [62], shape an unpredictable and dynamically evolving economic picture. In addition to that, construction materials present a gradual but persistent cost increase, which amounts up to 4.4% monthly increases [63].

Adding up, the total investment cost of the optimum, four-intervention, retrofit strategy is EUR 6734.3, and the SPP is 51.0 years. The combination of all technologies investigated results in a significant investment cost, which needs to be considered in the decision-making process for an energy renovation project. To increase the feasibility of a retrofit strategy, a more economically efficient perspective should be inherited. More specifically, a practical approach would prioritize the implementation of retrofit actions that are characterized by lower capital cost and therefore shorter payback periods. A different approach involves the selection of the single retrofit approach that co-optimizes energy savings and investment cost [64]. Finally, retrofit solutions that target seasonal objectives, for instance, cooling energy savings, are characterized by lower initial costs [65]. The selective and staged implementation of retrofit actions allows flexibility, requires lower upfront investment cost, and adapts better to future energy price fluctuations. Governmental financial incentives and policies for the implementation of holistic renovations strategies are crucial for the transformation of the existing building stock to energy-efficient and low-carbon-emissions buildings [66].

Focusing on seasonal energy savings, the two optimal retrofit scenarios dedicated to winter and summer use are also discussed. Firstly, regarding the winter season, the retrofit scenario that results in the maximum energy savings for heating (31.1%) and thermal comfort improvement (14.4%) includes the addition of insulation and windows replacement. According to the study by Schroderus et al. [67], the addition of insulation and windows replacement in multi-family buildings in Finland is calculated to result in a 25.5% decrease in the heating energy demand. Additionally, according to another multi-objective evaluation study of various retrofit scenarios for a one-story residential building, the addition of an external insulation layer to the building thermal envelope, and the installation of triple-glazed low-e windows, is found to induce 36.4% heating energy savings for the Mediterranean climatic conditions of Athens [37]. The capital cost of the retrofit strategy that is best suited for heating energy savings sums at EUR 5128.5. The corresponding SPP is calculated higher than the annual optimum scenario at 52.1 years.

On the other hand, the retrofit strategy that results in the greatest energy savings (41.2%) and thermal comfort enhancement (19.6%) during the cooling season includes the addition of insulation and external shading. These results are in accordance with the existing literature data and the study by Alhuwayil et al. [68], in which they investigated the combination of insulation and external shading for multi-story hotel buildings and various climatic conditions. Specifically, for the city of Athens, they reported that this retrofit strategy results in cooling energy savings that amount to 49%. The investment cost of the retrofit study is calculated significantly lower at EUR 997.8, with a much shorter SPP of 11.1 years. Table 4 summarizes the comparison metrics between the baseline and the annual and seasonally optimum retrofit scenarios.

Table 4.

Comparison of the baseline and optimum retrofit scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This work investigates the impact of various renovation actions on a typical residency apartment in Athens, Greece. The analysis focuses on various fundamental energy retrofit solutions and applies a multi-criteria evaluation process to determine energy savings in heating and cooling loads, as well as to estimate improvements in thermal comfort in each case. According to the results, the optimal annual renovation scenario in terms of annual energy savings and thermal comfort improvement is the one that combines all four retrofit technologies. In this scenario, the annual energy savings are 35.9%, the decrease in the PPD is 16.6%, and the decrease in the average absolute PMV is 0.09. Additionally, the maximum heating and cooling loads are restricted by 34.6% and 11.8%, respectively.

For the heating period, the two-intervention scenario of thermal insulation and window replacement is found to induce the maximum decrease in heating energy demand, equal to 31.1%, and the maximum decrease in thermal discomfort, equal to 14.4%. On the other hand, for the cooling period, the combination of all four passive building envelope technologies results in a 54.1% reduction in cooling energy demand and a 24.4% enhanced indoor thermal environment.

The present study offers valuable insights regarding the ranking of various heating and cooling energy-intensive retrofit technologies when applied on residency apartments for Mediterranean climatic conditions. The addition of thermal insulation is identified as a top-priority renovation action because it is involved in the one-, two-, three- and, of course, four-intervention optimum renovation scenarios. Shading ranks as second, window replacement as third, and, finally, the mechanical ventilation system is the fourth-priority renovation action. The installation of shading elements and mechanical ventilation systems is characterized as a cooling retrofit technique, for which shading is calculated to be more energy and thermal comfort effective. Thermal insulation and highly insulative windows are characterized as heating renovation actions. However, in contrast to shading, thermal insulation and highly insulative windows do not result in cooling penalties or an increase in thermal discomfort. These findings are highly useful for the definition of energy and thermal comfort efficient strategies for residential buildings, offering clear guidelines and a solid methodological framework for the prioritization of retrofit actions to achieve energy savings and improved thermal comfort.

The conclusions of this analysis need to be expanded for multiple building typologies and different types of building uses. Buildings with seasonal operation, such as hotels, as well as buildings in various climate zones, could greatly benefit from a proper prioritization of retrofit actions. However, the economic feasibility and direct applicability of the recommended retrofit strategies need to be further investigated through additional, case-specific analyses that consider local construction practices, cost structures, occupancy patterns, and regulatory constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., E.B. and D.G.; Methodology, A.K., E.B. and C.S.; Validation, A.K.; Formal analysis, A.K., E.B., D.G., E.V. and N.-C.C.; Investigation, A.K., E.B., C.S., D.G., E.V., N.-C.C., G.M. and C.T.; Resources, A.K.; Writing—original draft, A.K., E.B., C.S., D.G., E.V., N.-C.C., G.M. and C.T.; Supervision, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been carried out in the framework of the following projects: The European Union’s Horizon Europe program under grant agreement ID:101147412 (SIRCULAR: “Sustainable and integrated people centric solutions for building decarbonisation and circularity”); The project NEW-EPOCH (eNErgy Waste solutions through development of POsitive sChool buildings as sustainable, innovative Hubs for community engagement) co-funded by the European Urban Initiative (Project Number: EUI03-242), https://www.urban-initiative.eu/ia-cities/kifissia/home (accessed on 30 December 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request. Interested researchers are encouraged to contact the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| ach | Air changes per hour, - |

| CO2 concentration, ppm | |

| C0 | Investment cost, EUR |

| L | Human-specific thermal losses, W/m2 |

| M | Specific metabolic rate, W/m2 |

| FG | Source fraction, - |

| FR | Sink factor, - |

| CO2 generation rate, m3/s | |

| Pel | Electricity consumption load for heating and cooling, W |

| CO2 removal rate, m3/s | |

| CO2 source strength, m3/s | |

| t | Time, s |

| U-value | Thermal transmittance, W/(m2·K) |

| Abbreviations | |

| ES | Energy savings |

| Ins | Thermal insulation renovation action |

| Low-e | Low emittance |

| PMV | Predicted mean vote |

| PPD | Predicted percentage of dissatisfied |

| Shad | Shading renovation action |

| SSP | Simple payback period |

| Vent | Mechanical ventilation renovation action |

| Win | Replacement of windows renovation action |

References

- ASHRAE Handbook-Fundamentals. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/ashrae-handbook/description-2021-ashrae-handbook-fundamentals (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Kola-Bezka, M. One Size Fits All? Prospects for Developing a Common Strategy Supporting European Union Households in Times of Energy Crisis. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Pallantzas, D.; Sammoutos, C.; Lykas, P.; Bellos, E.; Vrachopoulos, M.; Tzivanidis, C. A Comparative Investigation of Building Rooftop Retrofit Actions Using an Energy and Computer Fluid Dynamics Approach. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homod, R.Z.; Almusaed, A.; Almssad, A.; Jaafar, M.K.; Goodarzi, M.; Sahari, K.S.M. Effect of Different Building Envelope Materials on Thermal Comfort and Air-Conditioning Energy Savings: A Case Study in Basra City, Iraq. J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, K.; Nguyen, Q.; Tasdizen, T. The Effects of Passive Design on Indoor Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings for Residential Buildings in Hot Climates: A Systematic Review. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, A.; Aba-alkhail, F.; ALAnzi, A. Determining the Optimum Fixed Solar-Shading Device for Minimizing the Energy Consumption of a Side-Lit Office Building in a Scorching Climate. J. Eng. Res. 2021, 9, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, Y.; Lai, D.; Lan, L.; Zhao, Z.; Du, H.; Lian, Z. Analysis of Occupant Thermal Comfort and Energy-Saving Potential Based on Cooling Behaviors in Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Shanghai. Build. Environ. 2025, 275, 112792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiques, M.; Tarragona, J.; Gangolells, M.; Casals, M. Energy Implications of Meeting Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Comfort Standards in Mediterranean Schools Using Natural and Mechanical Ventilation Strategies. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. Energy Inspections of Buildings, Statistical Analysis for the Year 2021 and the Period 2011–2019 06/20220; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2016. Available online: https://bpes.ypeka.gr/?page_id=21 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-performance-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Reveshti, A.M.; Mansoub, F.H.; Reveshti, J.N.; Bonab, K.F. Evaluation of Thermal Performance of Innovative Insulation Materials for Energy-Efficient Buildings in Cold Climates. Int. J. Thermofluids 2026, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Huang, H. A Review on Switchable Building Envelopes for Low-Energy Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.J.E.; Palutikof, J.P.; Tonmoy, F.N.; Smallcombe, J.W.; Rutherford, S.; Joarder, A.R.; Hossain, M.; Jay, O. Retrofitting Passive Cooling Strategies to Combat Heat Stress in the Face of Climate Change: A Case Study of a Ready-Made Garment Factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Energy Build. 2023, 286, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C. An Up-to-Date Review of Passive Building Envelope Technologies for Sustainable Design. Energies 2024, 17, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedki, A.; Hamza, N.; Zaffagnini, T. Effectiveness of Occupant Behavioral Ventilation Strategies on Indoor Thermal Comfort in Hot Arid Climate. In Sustainable Building for a Cleaner Environment: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Network’s Med Green Forum 2017; Sayigh, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 15–24. ISBN 978-3-319-94595-8. [Google Scholar]

- Miracco, G.; Nicoletti, F.; Arcuri, N. Adaptive Thermal Insulation for Energy-Efficient Buildings: Design and Analysis of an Innovative Thermal Switch Panel with Variable Transmittance. Energy 2025, 334, 137623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Ren, R.; Li, L. Existing Building Renovation: A Review of Barriers to Economic and Environmental Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.; O’Connell, J.; Goggins, J. Sustainable Energy Efficiency Retrofits as Residenial Buildings Move towards Nearly Zero Energy Building (NZEB) Standards. Energy Build. 2020, 211, 109816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.B.; Ferreira, A.C.; Pinto, B.; Gonçalves, P.; Rodrigues, N.; Teixeira, J.C.; Teixeira, S. Energy Simulations of an Existing Villa Converted into a nZEB Building with Assessment of the Human Thermal Comfort. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 275, 126857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.; Park, J.H.; Kang, Y.; Kim, S. Advancing Retrofitting Practices for Heritage Masonry: The Role of Insulation Materials in Thermal and Hygrothermal Performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.; Choi, J.Y.; Yang, S.; Kim, S. Balancing Preservation and Utilization: Window Retrofit Strategy for Energy Efficiency in Historic Modern Building. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Yao, S.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Thermo-Economic Optimization of a Building System Integrating Envelope and Energy Supply Equipment for the Rural Residence. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, B.; Marigo, M.; Tognon, G.; De Carli, M.; Zarrella, A. Investigation of the Localized Discomfort Due to Vertical Radiant Asymmetry in a Test Room with Radiant and Mechanical Ventilation Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 274, 126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, E. Optimization of Night Mechanical Ventilation Strategy in Summer for Cooling Energy Saving Based on Inverse Problem Method. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. Power Energy 2018, 232, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motuzienė, V.; Lapinskienė, V.; Rynkun, G. Optimizing Ventilation Systems for Sustainable Office Buildings: Long-Term Monitoring and Environmental Impact Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuwayil, W.K.; Abdul Mujeebu, M.; Algarny, A.M.M. Impact of External Shading Strategy on Energy Performance of Multi-Story Hotel Building in Hot-Humid Climate. Energy 2019, 169, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, A. Climate Adapted Façades in Zero-Waste and Cradle to Cradle Buildings—Comparison, Evaluation and Future Recommendations, e.g. in Regard to U-Values, G-Values, Photovoltaic Integration, Thermal Performance and Solar Orientation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 032105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, J.I.; Ibarra, L.; Ponce, P.; Meier, A.; Molina, A. A Static Rooftop Shading System for Year-Round Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings in Hot Climates. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.; Su, X.; Talami, R.; Ghahramani, A. Enhancing Building Envelopes: Parametric Analysis of Shading Systems for Opaque Facades and Their Comparison with Cool Paints. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 6, 904–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, F.; Hao, H. Human Thermal Comfort Model and Evaluation on Building Thermal Environment. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lian, Z.; Lai, D. Thermal Comfort Models and Their Developments: A Review. Energy Built Environ. 2021, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziozas, N.; Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Iliadis, P.; Gonidaki, D.; Angelakoglou, K.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Ricciuti, S.; Viesi, D. Energy Performance Analysis of the Renovation Process in an Italian Cultural Heritage Building. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Chamber of Greece. Technical Guidelines of Technical Chamber of Greece (ΤΕΕ); Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Sammoutos, C.; Lykas, P.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. A Detailed Investigation of Thermochromic Dye-Based Roof Coatings for Greek Climatic Conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Lykas, P.; Sammoutos, C.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. A Systematic Analysis of Phase Change Material and Optically Advanced Roof Coatings Integration for Athenian Climatic Conditions. Energies 2023, 16, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsø, B.G.; Haukø, A.-M.; Risholt, B. Experimental Study of Fire Exposed Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) Insulation Protected by Selected Coverings. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Lykas, P.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. Multi-Objective Evaluation of Different Retrofitting Scenarios for a Typical Greek Building. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Ziozas, N.; Iliadis, P.; Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C.; Nikolopoulos, N. Energy Performance Analysis of Alternative Building Retrofit Interventions for the Four Climatic Zones of Greece. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, C.; Orsino, M.; La Fianza, G.; Giametta, F.; Catalano, P. Study of a Mechanical Ventilation System with Heat Recovery to Control Temperature in a Monitored Agricultural Environment under Summer Conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Han, K.J.; Lee, J.W. The Impact of Shading Type and Azimuth Orientation on the Daylighting in a Classroom–Focusing on Effectiveness of Façade Shading, Comparing the Results of DA and UDI. Energies 2017, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesignBuilder Software Ltd. Available online: https://designbuilder.co.uk/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- EnergyPlus. Available online: https://energyplus.net (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Mirsadeghi, M.; Cóstola, D.; Blocken, B.; Hensen, J.L.M. Review of External Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient Models in Building Energy Simulation Programs: Implementation and Uncertainty. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 56, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N. Field Experiment Study on the Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient on Exterior Surface of a Building. ASHRAE Trans. 1972, 78, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- JRC Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS)—European Commission. Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/#api_5.1 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Engineering Reference. Available online: https://bigladdersoftware.com/epx/docs/22-1/engineering-reference/ (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Liu, J.; Foged, I.W.; Moeslund, T.B. Clothing Insulation Rate and Metabolic Rate Estimation for Individual Thermal Comfort Assessment in Real Life. Sensors 2022, 22, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7730:2005(En); Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment–Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:7730:ed-3:v1:en (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- de la Hoz-Torres, M.L.; Aguilar, A.J.; Costa, N.; Arezes, P.; Ruiz, D.P.; Martínez-Aires, M.D. Predictive Model of Clothing Insulation in Naturally Ventilated Educational Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnergyPlus Input-Output Reference. Available online: https://energyplus.net/assets/nrel_custom/pdfs/pdfs_v23.2.0/InputOutputReference.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Bellos, E.; Tsimpoukis, D.; Lykas, P.; Kitsopoulou, A.; Korres, D.N.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. Investigation of a High-Temperature Heat Pump for Heating Purposes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greece Electricity Prices. March 2025. Available online: https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/Greece/electricity_prices/ (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Team, G.W. Trends in CO2—NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/global.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Fang, T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Y. A Method for Estimating Occupant Carbon Dioxide Generation Rates. Energy Build. 2024, 312, 114163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOTEE (KENAK). TEE 2021. Available online: https://web.tee.gr/kenak/totee/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Bastos, J.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Melica, G. GHG Emission Factors for Electricity Consumption; European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jablite EPS Insulation. Available online: https://www.insulationuk.co.uk/collections/jablite-insulation (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- KÖMMERLING 76 MD Standard|KÖMMERLING. Available online: https://www.koemmerling.gr/gr/products/window-residential-door-systems/76-mm-systems/md-standard/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Shape, S. Mechanical ventilation systems. Available online: https://opsiktikos.gr/blog/sygkrisi-topikwn-systimatwn-mixanikou-aerismou-me-anaktisi/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Shamout, S.; Al-Khuraissat, M.; Jordan Green Building Council; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Amman Office. Your Guide to Building Envelop Retrofits for Optimising Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort in Jordan; Jordan Green Building Council: Amman, Jordan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Işık, C.; Kuziboev, B.; Ongan, S.; Saidmamatov, O.; Mirkhoshimova, M.; Rajabov, A. The Volatility of Global Energy Uncertainty: Renewable Alternatives. Energy 2024, 297, 131250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlík, M.; Kurimský, F.; Ševc, K. Renewable Energy and Price Stability: An Analysis of Volatility and Market Shifts in the European Electricity Sector (2015–2025). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ΕΒΕA ELSTAT: 4.4% Increase in Prices of Building Materials in January 2025—Directorate of Industry & Commerce, Athens 2025. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/4b9aeab3-95b8-cd4f-c98c-af4f80faa679 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Makris, D.; Antzoulatou, A.; Romaios, A.; Malefaki, S.; Paravantis, J.A.; Giannadakis, A.; Mihalakakou, G. Optimizing Energy and Cost Performance in Residential Buildings: A Multi-Objective Approach Applied to the City of Patras, Greece. Energies 2025, 18, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Muhieldeen, M.W. Evaluation of Cooling Energy Saving and Ventilation Renovations in Office Buildings by Combining Bioclimatic Design Strategies with CFD-BEM Coupled Simulation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, G.; Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Mauro, G.M. Incentive Policies for Building Energy Retrofit: A New Multi-Objective Optimization Framework to Trade-off Private and Public Interests. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 498, 145142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroderus, S.; Kuurola, P.; Kempe, M.; Fedorik, F.; Leivo, V.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Impacts of Building Energy Retrofits on Energy Consumption, Indoor Environment, and Hygrothermal Performance in Future Climate Scenarios. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuwayil, W.K.; Almaziad, F.A.; Abdul Mujeebu, M. Energy Performance of Passive Shading and Thermal Insulation in Multistory Hotel Building under Different Outdoor Climates and Geographic Locations. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 45, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.