Abstract

To maintain power system stability and supply quality when integrating doubly fed induction generator (DFIG)-based wind energy conversion systems (DFIG-WECSs), regulators regularly update grid codes specifying low voltage ride-through (LVRT) requirements. This paper presents a systematic literature review (SLR) on the use of STATCOMs to enhance LVRT capability in DFIG-WECSs. Objectives included a structured literature search, bibliographic analysis, thematic synthesis, trend identification, and proposing future research directions. A PRISMA-based methodology guided the review, utilising PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts in the development of the abstract. The final search was conducted on Scopus (31 March 2025). Eligible studies were primary research in English (2009–2014) where STATCOM was central to LVRT enhancement; exclusions included non-English studies, duplicates, reviews, and studies without a STATCOM focus. Quality was assessed using an adapted Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool. No automation or machine learning tools were used. Thirty-eight studies met the criteria and were synthesised under four themes: operational contexts, STATCOM-based schemes, control strategies, and optimisation techniques. Unlike prior reviews, this study critically evaluates merits, limitations, and practical challenges. Trend analysis shows evolution from hardware-based fault survival strategies to advanced optimisation and coordinated control schemes, emphasising holistic grid stability and renewable integration. Identified gaps include cyber-physical security, techno-economic assessments, and multi-objective optimisation. Actionable research directions are proposed. By combining technical evaluation with systematic trend analysis, this review clarifies the state of STATCOM-assisted LVRT strategies and outlines pathways for future innovation in DFIG-WECS integration.

1. Introduction

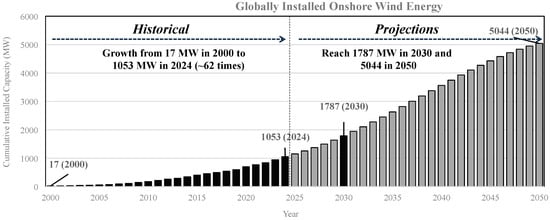

The ever-increasing demand for electrical energy to drive economic processes and provide a comfortable living environment for humans has historically been met using fossil fuels [1,2]. However, the increasing concerns about climate change and the projected adverse consequences, the risks associated with the prices of fossil fuels, and the finiteness of fossil fuels, among other reasons, have created a continually growing interest in the utilisation of renewable energy sources (RESs), especially wind energy [3]. Many countries are embracing wind, with wind power generation now being utilised in over 83 countries globally [4]. One of the reasons for this popularity is that wind has higher load factors than other types of RESs [5]. This has led to a significant increase in installed wind capacity worldwide. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the total globally installed wind capacity increased around 62 times from around 17 MW in 2000 to around 1053 MW in 2024, and this capacity is expected to reach the levels of 1787 MW and 5044 MW in 2030 and 2050, respectively [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Figure 1.

Historical values and future projections of the globally installed onshore wind generation capacity.

In generating electricity from wind energy, the kinetic energy due to the motion of the air is converted into electrical energy through a wind turbine [18]. The wind turbine has suitably shaped blades that radiate from a shaft, on which the force of the wind is applied, providing a mechanical energy input required to drive a wind turbine generator to produce electricity. The wind turbine components can be classified into three parts [19]. Firstly, the mechanical part comprises the blades, the drive train, the gearbox, and the pitch control mechanism. Secondly, the electrical part encompasses the electrical generator, all power electronic devices, including the converters, capacitance and inductance components, and the protection system. Thirdly, and lastly, there is the control system that includes the converter control and the blade angle control system, which sends signals to the pitch mechanism actuator to rotate the blades.

One way of classifying the wind energy conversion systems (WECSs) is by the speed of the wind turbine [19]. Type 1 and type 2 WECS use fixed-speed wind turbines together with an induction generator, but a variable rotor resistor is also attached to the latter. Type 3 and 4 WECSs use variable speed wind turbines, with a doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) used in the former and a permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) used in the latter. There has been a dominance of the variable-speed wind turbines as they offer some advantages, e.g., they maximise the capture of power, the controls of the active and reactive powers are decoupled, the wind turbines have reduced the mechanical stress, and the acoustic noise is also reduced [20].

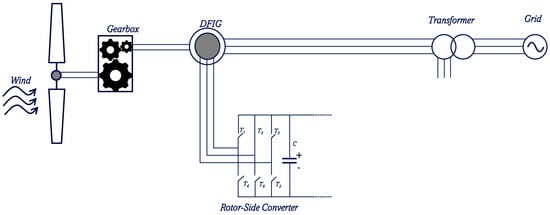

Figure 2 presents the layout of a Type 3 variable-speed, DFIG-type wind turbine [21]. The key components are an induction generator, with a stator connected directly to the grid, and a rotor that interfaces via a back-to-back partial-scale converter comprising the rotor-side converter (RSC) and the grid-side converter (GSC). The pitch controller and the electrical controllers of the converters make up the control system. Although both of these wind turbines have variable speed, the Type 3 DFIG-based WECS offers the advantage of using a partial converter compared to the Type 4 PMSG-based WECS that uses a full converter, making the latter more expensive. Thus, a DFIG-based WECS (DFIG-WECS) has better economic viability and, as a result, contributes more than 50% of the turbines used in the wind energy market [22].

Figure 2.

Key components of a DFIG wind turbine.

Wind turbines are integrated into power systems built in environments characterised by the existence of factors, e.g., animals, environmental conditions, weather and climatic phenomena, pollution, and human activity, which can cause faults that lead to system disturbances [23]. Other disturbances can be caused by significant variations in the levels of generation and load [24]. Due to these disturbances, system-wide variation in the magnitudes of voltages and frequencies can be experienced [25]. To protect the generators, they are fitted with overvoltage and undervoltage relays for extreme voltages, and generators are also provided with over-frequency and under-frequency relays to prevent damage from extreme frequencies [26]. Thus, disconnection will occur if acceptable ranges of the parameters are exceeded [27].

Disturbance occurring anywhere in the power system, even far away, could be felt at the point of DFIG connection, causing voltage variations [28,29]. Because of the direct connection of the DFIG’s stator to the grid, the DFIG is vulnerable to disturbances [30,31,32]. Any voltage sag or phase jump immediately propagates to the stator flux. If a sudden reduction in stator voltage occurs, the machine is demagnetised, with a large transient electromotive force (EMF) (proportional to , i.e., the rate of change in stator flux) induced in the rotor, demanding high rotor current. The RSC and GSC are current-limited, in the order of 1.2–1.5 , and the DC-link may experience overvoltage during extreme faults.

In the absence of any protection mechanism, when the system disturbances are sufficiently significant, the DFIG protects itself by disconnecting from the grid, e.g., when voltage sags result from faults that cause overcurrents. For networks with high penetration of wind, the disconnection of many wind plants could cause a severe shortage of power that can lead to a difficult network recovery from disturbances and impair the system’s stability.

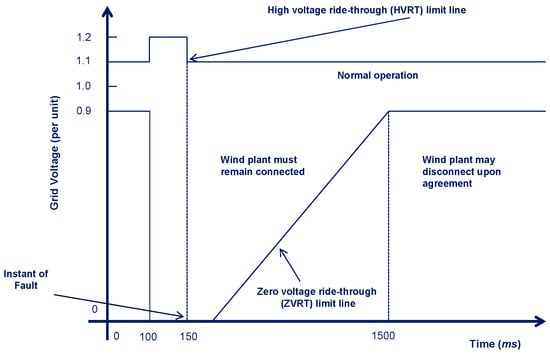

Thus, wind turbines should possess the so-called voltage ride-through (VRT) capability, meaning that following grid faults or disturbances, for certain ranges of voltage drop or rise and time intervals, the turbines should not be disconnected from the grid, but must be able to operate continuously [33,34]. In pursuance of this objective, technical specifications called grid codes are formulated and developed regularly to ascertain stability and quality of power [35,36,37,38]. As an example, Figure 3 graphically shows the requirements for VRT as specified in E. ON regulations, and with the requirements for high-VRT (HVRT), low-VRT (LVRT), and zero-VRT (ZVRT) indicated [39]. The criteria for LVRT and ZVRT are related, with ZVRT applicable in cases where voltage is reduced to zero by faults in the grid, and LVRT is applicable when faults in the grid reduce voltages to 15 to 25%, and below, of the nominal voltage value. All these criteria aim to ensure that turbines can work safely and support the grid during faults.

Figure 3.

Voltage ride-through requirements as specified in the E. ON regulations.

Broadly speaking, several strategies have been proposed to improve fault ride-through (FRT) capability of DFIGs, enabling the DFIG-WECS so that they can operate without disconnecting from the grid during faults. These strategies can be categorised into FRT schemes based on protection circuits, FRT schemes based on reactive power injecting devices, and FRT schemes based on control approaches [39,40,41,42]. The use of reactive power compensation devices has been adopted to minimise voltage collapse risk at the point of DFIG connection, to ensure the DFIG can continue to operate during faults, and to support voltage recovery after a fault [40,41]. Devices called flexible AC transmission systems (FACTS) controllers were developed, and they can supply fast, continuously variable compensation without the concern of mechanical wear, enabling them to dynamically inject or absorb reactive power, thereby smoothly and rapidly controlling active and reactive powers [43]. In this way, they can be of major benefit to the system and can enable voltage control [44,45].

When severe disturbances occur in the system, the crowbar protection circuit often triggers, shorting the rotor circuit, causing the generator to absorb reactive power from the system, further depressing the voltage at the point of common connection (PCC) and delaying post-fault voltage recovery [30,31,32]. Thus, fast external reactive power support at the PCC is required at the PCC to satisfy LVRT requirements in weak or disturbed grids. One device that belongs to the family of FACTS, i.e., the static synchronous compensator (STATCOM), has been proposed for reactive power injection to improve the FRT capability of the DFIG-WECS [39,46,47].

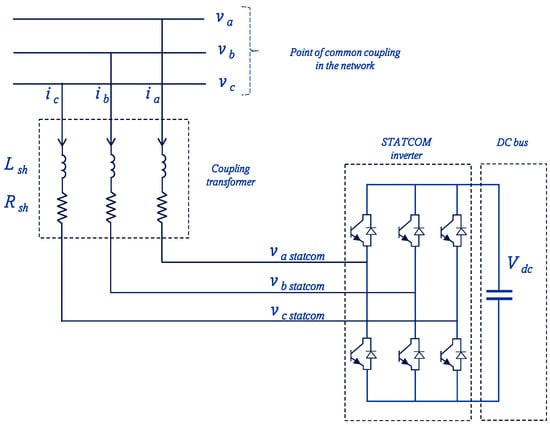

A STATCOM scheme is demonstrated in Figure 4 and its key components entail the DC side capacitor that provides voltage support, a voltage source inverter (VSC) built using the high-power electronic switching devices (either gate turn-off thyristors (GTO) or gate-insulated bipolar transistors (IGBT)), and a coupling transformer that serves to integrate the high power converter to the power systems, in addition to filtering harmonics of the output voltage of the inverter [48,49].

Figure 4.

A scheme of the STATCOM and its connection to the grid, showing the point of common connection (PCC), the coupling transformer, the converter, and the DC source.

STATCOM has three modes of operation [50]. It operates as a capacitor when , as an inductor when , and it floats when . The exchange of active ) and reactive ) power between the power system and the STATCOM can be formulated as

with being the active power exchanged through the coupling reactance, being the ac system/PCC side reactive power (positive if injected to the grid), being the STATCOM ac bus side reactive power (positive if absorbed by the STATCOM), being the root mean square (RMS) system voltage at the PCC, being the VSC RMS internal voltage, being the reactance of the coupling transformer, and being the phase angle difference between voltages and .

The global market for STATCOMs was around USD 1.08 billion in 2024 and is forecasted to steadily grow to USD 1.66 billion in 2029 [51]. Among the key drivers for this growth are increased uptake of renewable energy generation, especially wind and solar energy, the need to maintain grid stability amid increasing global demand for electricity, government initiatives and regulations that promote renewable energy, and initiatives aimed at grid modernisation [52]. The STATCOMs are highly effective for maintaining voltage levels, power factor correction, and mitigation of grid disturbances [53].

The author conducted a literature search of previous reviews addressing VRT enhancement of WECS by STATCOMs. A thorough search for relevant publications in Google Scholar, using the search string “Fault Ride-Through” and “dfig” and “statcom” and “review” or “survey”, was conducted on 31 November 2024, with a focus on material in English. Full texts were accessed through institutional subscriptions or other legitimate means, where required; no restriction based on free availability was applied. The search was restricted to the first 20 pages returned by the search engine. A total of eleven (11) literature reviews met the search criteria and were relevant to the study.

Some reviews focused on broad FRT issues for WECS, with Ansari [39] presenting a review on FRT operation analysis of the DFIG-WECS, Moheb [41] comprehensively reviewing FRT requirements applicable to renewable hybrid microgrids, Verma [42] reviewing FRT strategies for DFIG-based wind turbines, Ling [46] discussing the FRT technologies for DFIG wind turbines, and Parameswari [47] reviewing the FRT capability of grid-connected DFIG wind turbines. Moreover, Nguyen and Negnevitsky [54] reviewed the FRT strategies for different WECS, and Meegahapola et al. [38] reviewed the role of FRT strategies in power grids comprising 100% distributed renewable energy resources interfaced by power electronics.

In the review by Hannan et al. [55], a broad review on WECSs, their controls and applications as sustainable technology was presented. Another group of reviews dealt with methods for LVRT enhancement for a grid-integrated wind generator, with Howlader and Senjyu [56] presenting a review of LVRT strategies of WECSs and Mahela et al. [57] presenting an overview of LVRT methods for grid-integrated wind generators. Qin et al. performed the last review [58], and it focused on HVRT techniques for DFIG-based wind turbines.

Extensive research on the enhancement of VRT for WECSs, as evidenced by the number of reviews reported above and the primary research reported in these reviews, has been conducted. The author observed that these reviews [38,39,41,42,46,47,54,55,56,57,58] never dealt thoroughly with the application of FACTS for resolving VRT challenges for DFIG-WECSs. Issues related to this subject were only mentioned narrowly in these reviews, and no comprehensive treatment of this subject was carried out in any of these reviews.

Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to perform a systematic literature review (SLR) on the application of STATCOMs to improve the LVRT capability of DFIG-WECSs. In developing the SLR, the following key objectives have been set:

- Perform a structured literature search on the application of STATCOMs to improve the LVRT capability of DFIG-WECSs.

- Conduct an analysis of the bibliographic information for the documents identified and included in the SLR will be performed.

- Extract main themes from the body of the selected literature and synthesise summaries thereof.

- Research developments and trends will be analysed and presented, and this will help in determining directions for research.

- Suggest and present areas for future research into applications of STATCOMs for enhancing the LVRT of DFIG-WECSs.

The rest of the paper is made up of Section 2, which describes the methodology of the review, Section 3, in which the analysis of the bibliographic data is performed, and summaries of the main themes extracted from the body of the included publications are synthesised. In Section 4, research trends and gaps are presented, and Section 5 concludes the review and proposes directions for future research.

2. Research Methodology

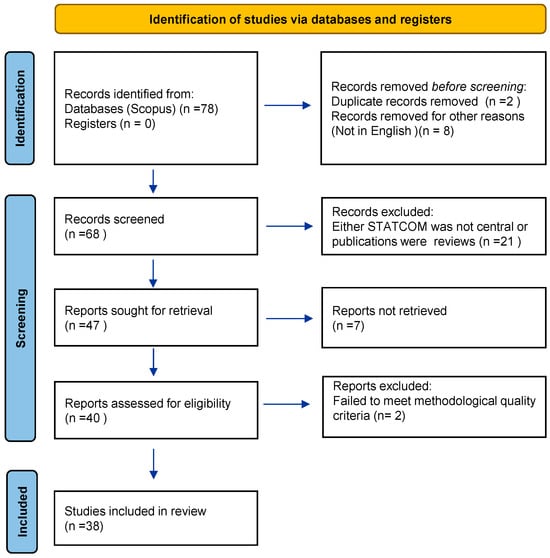

To conduct and report on the SLR proposed above, the author used a method based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [59]. The approach assisted the author in structuring the review into a sequence of stages, including identification, screening, determining eligibility, and deciding on inclusion into the review of publications. Figure 5 below shows a schematic summary of the process followed to identify the body of publications that form the basis of the SLR. A PRISMA 2020 expanded checklist was prepared on the conclusion of the SLR and will be provided as the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 5.

A schematic representation of a PRISMA-based approach to the SLR is shown.

2.1. Identification

The author selected Scopus as a database to be a source of publications that would form part of the SLR. This choice was firstly influenced by the fact that Scopus has extensive coverage of research from engineering, energy, and power systems, which align with the SLR’s focus and secondly by the availability of resources that constrained the feasibility of searching across multiple databases. Despite Scopus being a broad and reputable source of the scholarly literature, the author acknowledges that the comprehensiveness of the SLR may be restricted by the exclusion of other databases, such as IEEE Xplore and Web of Science. In interpreting the findings of the SLR, this limitation should be recognised and considered.

The following approach was used during the identification stage. The search option chosen was “Article, Title, and Abstract” with the string “Low” OR “High” OR “Zero” AND “Voltage Ride Through” AND “STATCOM” OR “static synchronous compensator” AND “dfig” OR “doubly fed induction generator” provided as input for the search. The final search for documents was conducted on 31 March 2025, with 78 publications returned. Publications produced over the 2009–2024 period were considered for further assessment. The screening phase of this SLR was performed at the end of the first quarter of 2025, at which time very few 2025 publications were available. The author thus opted to exclude 2025 from the review.

Further to this, 10 documents were not considered further as they were either not in English or had duplications. Thus, at the end of the identification stage, 68 documents remained.

2.2. Screening

Based on a detailed analysis of only the abstracts, documents in which STATCOMs were not a central focus, but were only mentioned casually, were eliminated from further consideration. Moreover, publications in which the STATCOM was mentioned for comparison purposes only, without providing technical details of their application, were excluded to maintain the review’s focus on STATCOM-based LVRT enhancement strategies. This also applied to documents that were identified by the search but were not relevant or were reviews. Twenty-one (21) such documents were identified and not considered further, leaving 47 documents for the next stages.

An attempt was made to assess whether the 47 documents at the end of the screening stage could be downloaded. Seven (7) of the documents did not meet this criterion and were not considered further, leaving 40 publications for the next stage.

2.3. Inclusion and Quality Assessment

The inclusion phase commenced with subjecting the 40 publications from the eligibility phase to a methodological quality assessment [60,61,62]. One of the tools that can be used for this purpose is the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [63,64], and it comprises 10 items that need consideration to establish the validity of the research studies, ascertain the results, and establish the applicability of the findings. In this paper, the author adapted CASP [65] to the engineering and energy context by using the following 5 focused questions (Q1 to Q5 below) to assess the methodological rigour in the publications. The process was conducted manually, without the use of automation or machine learning tools.

- Q1

- Does the study have clearly defined objectives that are relevant to the use of STATCOMs to enhance the LVRT of the DFIG-WECS?

- Q2

- Does the study have an appropriate research design to address the defined objectives?

- Q3

- Are there valid and adequately described data sources, models, and assumptions?

- Q4

- Is there a rigorous analysis of results that is supported by appropriate validation or some form of sensitivity checks?

- Q5

- Can the findings be reproduced and generalised to similar power system contexts?

Each publication was scored on the above five questions for quality and relevance, with only publications obtaining a score of 5 retained [66,67] for the next stage of thematic analysis, ensuring a robust and high-impact knowledge base for the review, and minimising the use of flawed studies. Utilising this approach enhances the reliability of the synthesised findings and provides transparency in the selection process.

At least two reviewers conduct the scoring of the quality criteria, and the inter-rater reliability is monitored using instruments with Cohen’s κ to assess the agreement between the reviewers. Discrepancies in the scores are normally resolved via consensus or by utilising a third reviewer. Due to resource constraints, the scoring was performed by a single reviewer in this paper. The reviewer adhered strictly to the predefined CASP-based questions above to mitigate bias.

In Table 1, the scores obtained for various publications assessed for quality are presented, demonstrating transparency and enhancing the robustness of the evidence base. Two publications by Karaagac et al. [68] and Qiu and Pan. [69] received scores of less than five and were not considered further in the SLR.

Table 1.

Quality assurance scoring for publications at the beginning of the inclusion phase.

Thirty-eight (38) publications met the quality requirement and were included in the next stage of the SLR. Some details of these documents, including the year of publication and the authors, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key details of publications that passed the inclusion phase and went into thematic analysis.

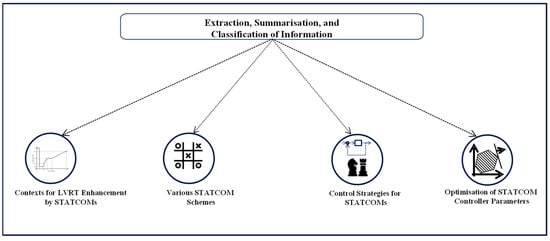

2.4. Synthesis from Included Publications

An in-depth review of the publications revealed four (4) main themes into which the information in the documents could be extracted and organised. These themes are shown schematically in Figure 6, and they include the following: contexts for LVRT enhancement using the STATCOMs, various STATCOM schemes, control strategies for the STATCOMs, and optimisation of STATCOM controller parameters. The author extracted the information from the selected publications and summarised and synthesised it under these themes and reported the results in Section 3. The author conducted the synthesis process manually, worked independently, did not consult the authors of the publications, and did not use any automation tools in the process.

Figure 6.

The four main themes that were used to synthesise the evidence from publications.

3. Results and Discussion

The results of the analysis of the publications included in the review are presented here. Firstly, the author presents the results of the analysis of the biographical data of the publications. Thereafter, the information extracted, summarised, and synthesised from the publications is presented under the four main themes that arose from the analysis of the publications, namely contexts for LVRT enhancement using STATCOMs, various STATCOM schemes, control strategies for STATCOMs, and optimisation of STATCOM controller parameters.

3.1. Analysis of Bibliographical Information

In this section, a bibliometric overview of the research on LVRT enhancement of DFIG-WECSs using STACTOMs is provided. The section gives an understanding of the maturity of the field, specifically highlighting the growth in publications, the prominence of certain journals, and the most cited papers that have shaped the current research directions.

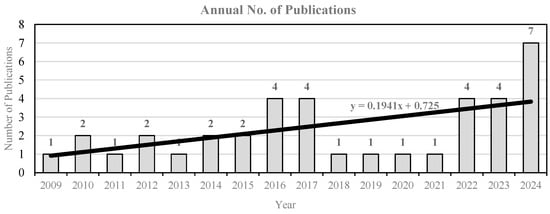

3.1.1. Annual Number of Publications

The number of publications produced annually over the period 2009–2024 is plotted in Figure 7. The graph shows a trend of a generally increasing number of publications, with a pronounced increase observable in the last 3 years. Starting with one publication in 2009, the number of publications has been increasing at an average rate of about 0.1941 papers per annum.

Figure 7.

Number of publications produced per annum.

3.1.2. Ten Most Cited Conferences and Journals

Some details of the ten most cited conferences and journals are presented in Table 3. The source with the most citations among the conferences and journals is the journal Energy Conversion and Management, with 124 citations. The remainder of the conferences and journals have produced publications with total numbers of citations ranging from the lowest of 13 to the highest of 59.

Table 3.

Top 10 most cited conferences and journals.

3.1.3. Top 10 Most Cited Papers

In Table 4, some details of the ten most cited papers are presented. The paper with the highest number of citations is titled “Supercapacitor energy storage system for fault ride-through of a DFIG wind generation system”; it was authored by Rahim and Nowicki in 2012 and has 124 citations. The remainder of the papers have a total number of citations ranging between 13 and 59.

Table 4.

Top 10 publications by the number of citations.

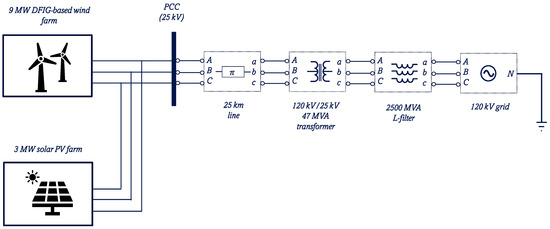

3.2. Contexts for LVRT Enhancement by STATCOMs

Different contexts of faults and system disturbances that can affect the LVRT and where STATCOMs can be utilised for enhancement of LVRT capability in DFIG-based WECSs are examined in this section. Faults within the DFIG-WECS can adversely affect its LVRT capability, e.g., an intermittent fire-through fault of a switch (such as T3, as demonstrated in Figure 8) of the RSC of a DFIG-based WECS [70]. It can result in a partial short circuit across the rotor when T6 begins to conduct, causing the voltage across the capacitor to drop to almost zero. In contrast, the rotor current will jump significantly to about 1.5 per unit. During the fault, a large amount of reactive power is drawn by the DFIG from the system. Once the fault is cleared, the DFIG will fail to return to operation at unity power factor and continue to draw reactive power.

Figure 8.

Configuration of the rotor-side converter during fire-through.

If a STATCOM is introduced, the system receives reactive power support. It becomes easier for the unity power factor operation of the DFIG to be restored once the fault has been cleared, and this reduces the reactive power required by the DFIG. Moreover, there is a reduction in the magnitude of the DFIG terminal voltage sag, and the steady state value of the voltage is recovered. Thus, the introduction of the STATCOM improves the WECS’s ability to comply with the LVRT requirements of modern grid codes during a fire-through fault in the RSC.

Besides faults within the DFIG, faults in the power system occurring near the DFIG-WECS could bring the voltage at the PCC down to levels below the disconnection threshold, leading to disconnection of the plants, which can result in active power imbalance and power system instability. Installing a STATCOM at the PCC can ensure that [71,72] reactive power is injected into the system to increase the PCC voltage, ascertaining that the DFIG is not disconnected from the system during three-phase-to-ground faults, and it continues to produce active power, thereby assisting in maintaining overall stability.

Installing a STATCOM at a PCC of various groups of DFIGs could, during a three-phase ground fault [73], improve voltages at various buses near the DFIG, leading to the increased electromagnetic torque and inhibition of the increase in rotational speed compared to the case without the STATCOM. Thus, during a fault, the output power is improved, the LVRT is enhanced, and overspeeding, which can, on its own, lead to disconnection, is prevented. Also, once the fault is removed, the installation of the STATCOM ensures a much more rapid recovery of the power generator’s output voltage.

Sudden changes in wind speed can result in significant voltage drops. They can cause various parameters and variables, e.g., grid current, stator current, rotor side voltage and current, reactive power, and active power, to change from their values during normal operation [74]. Connecting a STATCOM to the network can ensure that these parameters and variables can return to their normal values quickly while overcoming voltage drop challenges caused by the change in wind speed. This improves the LVRT of the DFIG wind plant.

STATCOMs can play a significant role in enhancing the LVRT of the DFIG-WECS under diverse operational contexts ranging from converter faults to grid-side disturbances and wind-speed fluctuations. STATCOMs can rapidly provide reactive power support to mitigate voltage sags and swells, stabilise generator dynamics, and reduce the risk of disconnection. This can ensure compliance with modern grid codes and improve system resilience. STATCOMs are thus an effective solution for maintaining stability and reliability in modern power networks that have an increasing share of renewable energy. However, despite the technical benefits of the STATCOMs, challenges related to cost, optimal sizing, and control coordination remain, highlighting the need for further research into the areas of hybrid strategies, techno-economic assessments, and field validation.

3.3. STATCOM Schemes for LVRT Enhancement

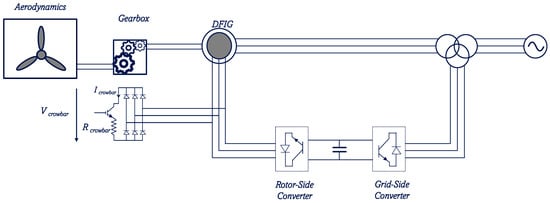

During grid faults, the converters of the DFIGs must be protected from overcurrents and overvoltages. In addition, modern grid codes mandate that DFIG-based WECSs must meet certain LVRT requirements. One of the well-known protection methods is the crowbar. It consists of a three-phase diode rectifier, a switching device (usually a thyristor or IGBT), and a small resistor, as demonstrated in Figure 9. The gate signal of the RSC is turned off during a voltage sag, thereby disconnecting the rotor from the crowbar.

Figure 9.

Connection of the crowbar protection to the rotor circuit.

Since the RSC is blocked during faults, there is a loss of control of the active and reactive powers of the wind turbine that the RSC performs. The DFIG acts as an induction generator, drawing reactive power from the grid, keeping the voltage at the PCC low, and, thus, delaying the grid’s recovery after the fault clearance. Upon clearance of the fault and sufficient recovery of the PCC voltage, the crowbar is removed, the RSC is re-enabled, and the DFIG can begin the supply of reactive power. Thus, during grid disturbances, conventional protection schemes such as crowbar circuits safeguard converters from overcurrents and overvoltages but often compromise reactive power support and delay voltage recovery.

To address these limitations of the conventional schemes, advanced solutions integrating STATCOMs have emerged, offering dynamic reactive power injection at the PCC, supporting effective steady-state operation, and improving system stability during disturbances. The remainder of this section explores various STATCOM-based configurations and complementary devices designed to enhance LVRT performance, minimise voltage fluctuations, and ensure reliable operation of DFIG-based wind farms under fault conditions.

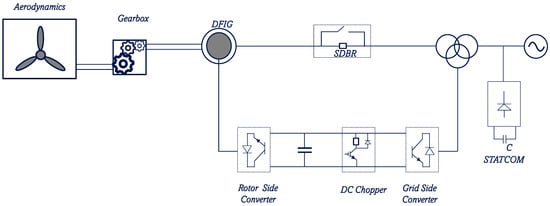

3.3.1. Proposed DFIG-SDBR Model Supported by a STATCOM

An improved model of a DFIG can also enhance its protection from system faults. This model can be realised if a DC chopper is connected on the DC bus side and a series dynamic braking resistor (SDBR) is connected to the stator of the DFIG, and the crowbar protection circuit (CPC) is removed, as shown in Figure 10. This action ensures that both the RSC and the GSC remain operational during grid faults. In this scheme [75], the DC bus is protected by the DC chopper, and the overcurrent on the rotor side is limited by the SDBR, while the stator is controlled by the RSC to supply reactive power during faults.

Figure 10.

The improved structure of a DFIG by the introduction of the SDBR and the DC chopper.

This enables the back-to-back converters to always supply the grid with reactive power. With a strategy of coordinated control of reactive power from the RSC, GSC, and the STATCOM connected to the PCC, the DC bus voltage fluctuation is small, and its value and that of the rotor current can be maintained near their nominal values during grid faults. Moreover, during a grid fault, the RSC is kept in service. In addition, the scheme has a better voltage recovery than the crowbar technology. Overall, the STATCOM contributes to better performance and enhances the LVRT ability of the whole system.

The STATCOM can support the continuity of power generation by the DFIG-WECS [76] by ensuring that the process of grid recovery is accelerated through speedy injection of reactive power into the grid once the crowbar is removed, and ensuring voltage can be recovered to around nominal levels in weak grids that do not have the means to return voltages to acceptable levels.

Despite the advantage of superior controllability offered by this scheme during faults, the need for additional hardware in the form of the SDBR and chopper increases the costs and raises concerns about the complexity of the scheme. Moreover, under prolonged faults, there is a practical challenge of thermal management of the SDBR.

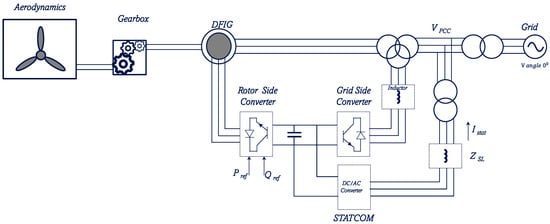

3.3.2. Common DC-Link of the RSC and GSC Supported by a STATCOM

In an ideal scenario, the voltage of the grid should be perfectly sinusoidal with constant frequency and constant amplitude. However, when connected to the grid, wind power systems will cause the deviation of voltage and frequency from ideal if, for example, any mismatch occurs between generation and demand, leading to deviation from nominal system frequency or if there is a sudden connection or disconnection of load.

These could cause the PCC to experience a voltage sag, with the DFIG suffering adverse impacts on its internal dynamics, e.g., the stator flux can be demagnetised, high transients can be developed in the electromagnetic torque, and the rotor current can develop excessive spikes. A STATCOM connected at the PCC, as demonstrated in Figure 11 [77], can mitigate these challenges.

Figure 11.

Common DC-link STATCOM support to DFIG.

The common DC-link STATCOM firstly improves the PCC voltage and current and, secondly, leads to an appreciable improvement in the suppression of the transients in the DC-link voltage, improves the power oscillation damping, reduces the ripple in the electromagnetic torque, removes stator flux demagnetisation, and reduces the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the grid current.

Although this scheme enhances oscillation damping and improves harmonic performance, precise coordination between converter and STATCOM controllers is crucial for its effectiveness. The tuning of the associated control loops can be challenging in weak grids, and miscoordination may lead to instability.

3.3.3. Operation of the GSC as a STATCOM During Crowbar Operation

Grid faults, even those occurring far from where the DFIG-WECSs are located, can cause the PCC to experience voltage sags that result in DC-link overvoltages and cause the rotor circuits and the RSC of the DFIG to suffer overcurrents, which can lead to the destruction of the RSC. During system faults, a crowbar protection circuit and a chopper system are often used to protect the RSC from these overvoltages and overcurrents. On control and operating strategies [78], can be used to maximise the controllability of the DFIG-WECS during faults. This can be achieved by operating the GSC as the STATCOM when the crowbar is activated and adjusting the RSC and GSC reactive power control loops to regulate the PCC voltage. This reduces the problems stated above and contributes to voltage improvements at the PCC during the disturbances. The foregoing strategies achieve improved compliance with the LVRT regulations.

Under normal operating conditions, the converters of the DFIG are operated so that the RSC supplies both the generator’s active and reactive powers. In contrast, the GSC operates at a unity power factor and maintains a constant DC voltage. The available current capacity of the GSC enables it to support the grid during disturbances by generating reactive power if an appropriate control system is implemented. Development of the control system must consider the control system of the RSC, the status of the RSC, and crowbar protection. One such coordinated system has been proposed by Sava et al. [79]. Based on the crowbar protection and the status of the RSC, the GSC must supply reactive power at the PCC to control the voltage level. This scheme increases the reactive power compensation capability for the DFIG-WECS, enhances the grid voltage stability, and improves the LVRT capability.

When the system voltage experiences a sharp decline, modifying the DFIG’s control strategy alone is insufficient to maintain system stability during the transient period, making additional hardware protection necessary. A widely implemented solution is the CPC. For the CPC to operate effectively, both the crowbar resistance value and its activation duration must be carefully designed.

The power electronic converters in a DFIG serve distinct purposes: the RSC enables vector control and separates active from reactive power, while the GSC regulates the AC side power factor, stabilises the voltage in the DC-link, and supports reliable operation of both the RSC and the entire excitation system. During CPC engagement, the RSC is deactivated, and the combination of the GSC with the DC-link functions in a manner like a STATCOM. During this condition, applying a suitable reactive power control strategy to the GSC, as suggested by Wang et al. [80], allows the STATCOM configuration to supply reactive power to the grid, compensating for the power absorbed by the DFIG. Once the grid returns to normal operation, the RSC switches to unity power factor control, eliminating the need for the GSC to supply reactive power. This operational approach of the GSC facilitates smoother and more reliable system recovery following disturbances.

The approach of operating a GSC as a STATCOM when the crowbar circuit is engaged is attractive due to its low hardware overhead. However, its reactive power capability is constrained by GSC current limits. The GSC alone may be insufficient to meet grid code requirements when severe voltage dips occur.

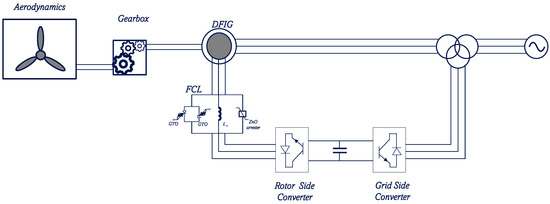

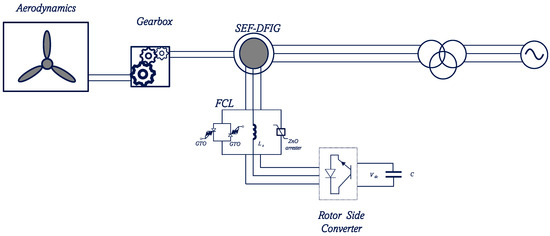

3.3.4. Combined Operation of STATCOM and Static FCL

Another scheme in which a static fault current limiter is placed between the rotor of a DFIG and the RSC, as shown in Figure 12, can enable uninterrupted operation during system faults [81]. The type of fault current limiter (FCL) comprises anti-parallel GTO switches, a zinc oxide (ZNO) arrester, and a current limiting inductor. During a grid fault, the GTOs of the FCL are turned off and connect a huge solenoid to the rotor circuit that inhibits the rotor current.

Figure 12.

Configuration of a turbine with a static fault current limiter.

On clearance of the fault, the GTOs are turned on, while the rotor circuit bypasses the solenoid. The advantages of this scheme are that during a fault, the generator and converter are not disconnected, the wind turbine generator maintains significant synchronous operation, and there can be immediate continuation of normal operation once the fault is cleared. Here, the STATCOM provides reactive power support at the PCC for effective steady-state operation and for requirements during fault conditions.

The incorporation of the FCL, while ensuring smooth and uninterrupted operation, can increase the DFIG-WECS cost, and the scalability of the scheme for large wind farms remains a question.

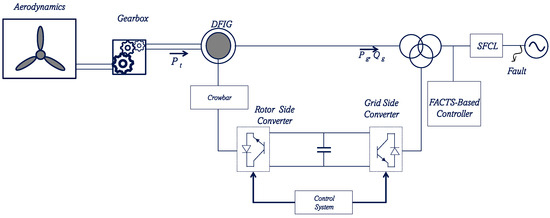

3.3.5. Combined Operation of STATCOM and SFCL

When grid faults occur near the terminals of a DFIG, the voltage will drop significantly, and if this persists, typically for more than 150 ms, the protection relay will take the DFIG out of operation, which can go against the LVRT requirements of the grid code. A STATCOM-SFCL scheme [82], demonstrated in Figure 13, in which a superconducting fault current limiter (SFCL), connected in series with the DFIG at the PCC, can be utilised for quadrature current generation to counter the drop in voltage resulting from faults.

Figure 13.

Proposed structure of a DFIG with an SFCL and a STATCOM.

The SFCL rapidly introduces impedance to limit excessive fault currents, allowing relay protection systems to function without disconnecting the DFIG. Its major strengths lie in remaining virtually invisible under normal grid conditions—exhibiting minimal impedance—and automatically returning to this low-impedance state once the fault is cleared.

The same STATCOM-FCL scheme described can also be used in a WECS that uses a DFIG configuration called single external feeding of the DFIG (SEF-DFIG) [83] in which the back-to-back variable frequency converter is replaced by the RSC in the layout of the conventional DFIG, as demonstrated in Figure 14. Moreover, the DC-link voltage can be lower than in a DFIG layout, ensuring lower switching losses and improved efficiency for the SEF-DFIG.

Figure 14.

Proposed scheme of SCL used in the SEF-DFIG.

Moreover, eliminating the GSC and filters reduces the overall cost and complexity of the WECS. The direct connection of the stator to the grid means that high currents, caused by grid faults, will be transferred to the DFIG. The RSC will feel no fault from the grid as it is isolated, but high currents will be induced in the RSC via the stator. The FCL between the stator and the RSC will protect the RSC from these overcurrents, while the STATCOM will supply the reactive power needed to support steady state and fault operation.

The utilisation of SFCL technology provides a hard to match speed of the limiting current during faults. However, its dependence on cryogenic systems significantly increases operational complexity and raises costs. There are also very scarce data on the practical deployment of SFCL, making reliability under real-world conditions uncertain.

3.3.6. PVSFC-STATCOM Scheme

The STATCOM utilises a DC/AC converter with a structure like that used in grid-connected renewable energy conversion systems, e.g., solar energy, as demonstrated in Figure 15. Thus, by adding an external loop that can control the voltage and reactive power exchanged between the converter and the grid, it is possible to make this converter of a photovoltaic (PV) generation plant operate as a STATCOM, forming a photovoltaic solar farm converter STATCOM (PVSFC-STATCOM) [84].

Figure 15.

Proposed scheme of a photovoltaic solar farm converter STATCOM (PVSFC-STATCOM).

The PVSFC can supply the reactive power required to support the grid when the DFIG cannot or during faults. The PVSFC can operate daily to supply the grid with active power under normal conditions. When there is either solar shading or if the weather is cloudy during the day, or during the night when there is reduced active power generation and some capacity exists for the converter to generate reactive power, operation in the PVSFC-STATCOM mode to supply reactive power and regulate the voltage at the PCC is reverted to. This improves the system voltages during disturbance, ensuring the continuity of service of generation.

When a disturbance occurs in the grid and a voltage dip occurs, the rotor currents in the DFIG experience high transients, and these can cause damage to the converters. This is also a safety issue, and it also influences system stability since, under these high transients, the DFIG must be tripped to avoid its islanded operation. Connecting the crowbar to the DFIG helps to reduce the high currents of the rotor. Still, the crowbar makes the DFIG operate like an induction generator, therefore drawing reactive power from the system and reducing the LVRT capability. If an appropriate control strategy can be provided to coordinate the operation of an active crowbar and the PVSFC-STATCOM, the latter [85] can act as a shunt compensator to enhance the stability of the system and improve the LVRT capability of the DFIG, thereby supporting the integration of wind farms.

The idea of leveraging PV converters for reactive support is innovative, but its effectiveness is contingent on PV availability and inter-plant coordination. Moreover, during peak solar generation, converter capacity for reactive power injection may be limited.

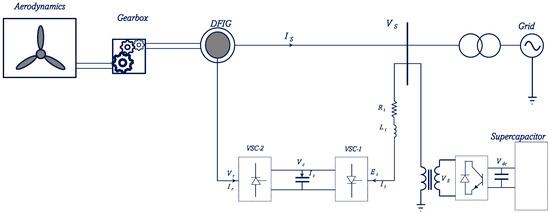

3.3.7. STATCOM-Supercapacitor Scheme

A STATCOM and a supercapacitor can be installed [86,87,88] at the bus where a DFIG-based wind farm has been connected. In this scheme, the STATCOM serves to supply the short-term reactive power required by the system and that required by the supercapacitor. On the other hand, the supercapacitor is utilised as an energy storage element. Following the occurrence and the clearance of faults in the power system, DFIG variables like output voltage, active power, angular speed, electrical torque, -axis stator current, and -axis stator current will oscillate.

If the STATCOM-supercapacitor scheme, as shown in Figure 16, is introduced, these oscillations are damped in a much shorter period than in the absence of the scheme. Moreover, when this scheme is used, the voltage drop at the DFIG terminals is reduced under fault conditions, increasing the chances of continuity of generation and the amount of power transfer during faults. The overall effect is that the scheme enables the DFIG to ride through some severe network faults.

Figure 16.

A STATCOM-supercapacitor scheme for the DFIG.

Once the fault has been cleared, the GTOs are turned on, and the rotor circuit bypasses the solenoid. The advantages of this scheme are that during a fault, the generator and converter are not disconnected from the grid, the generator maintains synchronous operation during faults, and on fault clearance, normal operation can be resumed immediately. The STATCOM provides reactive power support at the PCC for effective steady-state operation and for requirements during fault conditions.

The STATCOM-supercapacitor scheme is effective in damping oscillations and supporting deep sags. However, its deployment is seriously constrained by the supercapacitor cost and lifetime constraints.

3.3.8. Conclusions

STATCOM-based schemes enhance LVRT by stabilising PCC voltage and coordinating with protection devices, ensuring grid code compliance. Moreover, these schemes safeguard converter operation while enabling continuous active power delivery during faults. In addition, combined approaches, e.g., STATCOM-FCL and STATCOM-SFCL, besides extending the LVRT capability, reduce mechanical and electrical stresses on generators and converters, facilitating faster post-fault recovery.

3.4. Control Strategies of STATCOM

STATCOM control strategies critically influence LVRT performance by regulating reactive power and stabilising PCC voltage. Effective controllers regulate reactive power exchange, stabilise PCC voltage, and maintain DC-link voltage within safe limits during grid disturbances. A wide range of STATCOM control strategies and their relative advantages are discussed below.

3.4.1. PI-Based STATCOM Controllers

The relationship between the voltage of the AC system and that at the STATCOM terminals influences the amount and direction of reactive power flow to or from the STATCOM [70]. The flow from the STATCOM (capacitive mode of the STATCOM) will occur if the voltage at the terminals of the STATCOM is greater than the voltage in the system. The flow will be in the opposite direction (inductive mode of the STATCOM) when the voltage of the system is higher. When the conditions are normal, there will be two equal voltages, with no active and reactive powers exchanged. The exchange of active and reactive powers between the STATCOM and the grid is controlled through the firing angle and the modulation index to maintain the voltage at the PCC and the DC voltage within acceptable limits. The control system of the STATCOM will measure the voltages and currents at the PCC and transform them into components in a stator-flux oriented frame [89]. Comparison will be made between the voltage and current signals with reference values to derive the error signals and . The proportional integral (PI) controller will process these signals to derive the appropriate value of . The controller allows the STATCOM to reduce the fault impacts by restoring the PCC voltage to its nominal steady-state value and ensuring unity power factor operation of the DFIG both during and after the fault, thus improving its LVRT capability.

A STATCOM controlled by a Fractional-Order Proportional-Integral and Proportional-Integral (FOPI-PI)-controller [90], with the parameters of the controller optimised by using the Dandelion Optimiser (DO), has been proposed for DFIG wind turbines’ LVRT enhancement when faults occur. Moreover, the FOPI-PI controller can outperform the PI controller based on DO, the PI controller based on the Water Cycle Algorithm (WCA) algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) optimiser, and even a controller based on the hybrid WCA/PSO algorithm. With the superior FOPI-PI controller, the voltage drop is restricted to the lowest percentages, enhancing the LVRT ability of wind plants.

Because of their simplicity and ease of implementation, PI controllers are widely used. However, they have a limited performance under nonlinear and fast-changing conditions. They rely on fixed controller gains; they may not adapt well to changing grid dynamics. This can lead to slower recovery and possible overshoot of voltage at the PCC. Hybrid FOPI-PI controllers optimised by metaheuristic algorithms seem to demonstrate superior LVRT performance. However, their complexity and computational burden raise doubts about their real-time application in large-scale wind farms.

3.4.2. PID-Based STATCOM Controllers

Both symmetric or three-phase faults and asymmetric faults (e.g., double line-to-ground fault) can occur in hybrid networks, in which both PV and DFIG plants are present. In these circumstances, providing the STATCOM can be valuable in compensating for reactive power and improving LVRT. A Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controller [91] can be utilised for such STATCOMs, and this controller can adjust the PCC voltage during a grid fault by delivering reactive power, thereby enhancing the dynamic grid performance and enhancing the wind plant’s LVRT capability.

With the incorporation of a derivative term in the PIC controller, an improved dynamic response compared to PI controllers is achieved. However, tuning the parameters for multi-fault scenarios is challenging, especially under asymmetrical faults where the system is extremely nonlinear. Moreover, the derivative term could introduce noise, adversely impacting stability.

3.4.3. Indirect STATCOM Control Scheme Based on Decoupling Dual-Loop Current Control

An indirect control strategy employing decoupled dual-loop current regulation [73] was proposed for a STATCOM to improve LVRT performance during faults in a commercial wind farm with 23 DFIG units. This reactive power control scheme improves the voltage regulation performance during three-phase faults, enabling an enhanced LVRT capability and a speedy recovery of the output voltage of the DFIG.

The decoupled dual-loop approach separates active and reactive current control and is capable of precise reactive power compensation during severe faults. The approach enhances voltage regulation and improves the LVRT capability of the DFIG-WECS. The complexity of its implementation and its reliance on accurate modelling of the system are the major drawbacks with this approach that can limit its utilisation in weak grids or systems with high wind penetration.

3.4.4. Decoupled P-Q Control Strategy of a Supercapacitor Interfaced Through a STATCOM

During a severe symmetrical three-phase-to-ground fault at a grid bus, the resulting extremely low voltages can impair the operation of DFIG converters, threatening the stability and continuity of wind energy generation. To address this, a decoupled P–Q control strategy [88] has been proposed for a supercapacitor-based energy storage system interfaced through a STATCOM. This approach enhances the generator’s LVRT capability and improves damping performance. It allows the DFIG to remain operational under deep voltage sags for an extended period while effectively mitigating electromechanical transients, thereby facilitating a rapid return to normal converter operation.

The incorporation of supercapacitors provides fast energy support, enabling extended LVRT support during severe voltage sags, and mitigating electromechanical transients. However, there are additional costs introduced and maintenance challenges that come with energy storage systems.

3.4.5. Combined STATCOM with a Rotor Overspeeding Control Scheme

To support grid operation in a network with DFIG-based wind power generation during fault conditions and minimise the adverse consequences of resulting voltage sags, a STATCOM and a rotor overspeeding control strategy [92] have been suggested. The overspeeding scheme aims to substantially reduce the rotor overcurrents during voltage dips, thereby decreasing the torque and helping to hold the kinetic energy of the wind turbine for some time. Once the voltage dip has recovered, the stored energy is released.

Due to maximum generator speed limitations, using an overspeeding control strategy is not a long-lasting solution. Thus, a fast-acting STATCOM is also required to compensate for the demand for reactive power. The scheme has been demonstrated to minimise the grid transients, e.g., grid frequency fluctuations and enhance the LVRT capability.

The rotor overspeeding approach leverages the turbine’s kinetic energy to enhance LVRT performance by mitigating rotor overcurrents during faults. However, its capacity is only temporary, and its effectiveness is constrained by mechanical speed limits. While overall system resilience is enhanced by integrating this method with STATCOM, additional complexity is introduced to the control architecture.

3.4.6. Coordinated Control of DFIG and STATCOM

In DFIGs, the rotor speed will also vary nonlinearly with changes in wind speed, making the system behaviour unstable. Introducing a STATCOM at a good location along the system can help improve voltage stability. The coordinated operation of the DFIG and STATCOM [93] can be affected by using a PI controller whose parameters are selected in a multi-objective optimisation problem where the objective functions are the voltage at the PCC of the wind turbine and the low-frequency oscillation present in active power after recovery. The simulated annealing technique can be used to solve the optimisation problem. Under the mutually coordinated control action, the STATCOM can support the voltage at the PCC during faults and, therefore, enhance the FRT of the DFIG.

The previously described multi-objective optimisation problem for coordinated DFIG–STATCOM operation can be modified [94] by incorporating the real power available at the bus—both before and after a fault—into the objective function. Using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)-tuned PI controller for coordinated control, the scheme effectively enhances system stability and improves LVRT performance during grid disturbances.

When disturbances occur in the power system—such as the loss of a transmission line—the resulting network reconfiguration may fail to provide sufficient reactive power at the PCC of wind and conventional generators. This deficiency can lead to non-compliance with the LVRT requirements specified in grid codes. To address this, Lee et al. [95] proposed the concept of the Wind power plant applicable-effective Reactive Power Reserve (Wa-ERPR), which accounts for the reactive power capabilities of both wind farms and conventional generators at the Point of Interconnection (POI). Through the Wa-ERPR management algorithm, the reactive power demand corresponding to system topology changes before and after a contingency is determined. A STATCOM of suitable capacity, as computed through this scheme, is then applied at the POI. This approach ensures adequate reactive power support, allowing wind plants to meet LVRT criteria.

An optimised strategy for distributing reactive and active currents among the STATCOM, DFIG stator, and GSC during the LVRT period was proposed by Li et al. [96]. Unlike conventional LVRT methods that emphasise only reactive current injection, this approach accounts for the influence of active current on overall LVRT behaviour. By maintaining compliance with reactive current requirements while maximising active current contribution, the method effectively suppresses rotor speed acceleration and improves both fault ride-through and post-fault recovery performance of wind farms.

Because of the use of crowbar protection to prevent damage to the electronic equipment during faults, there is a blocking of the RSC, thereby removing the reactive power control ability. A coordinated control of the GSC, active crowbar protection, and the RSC proposed by Sava et al. [79], with the GSC controlled like a STATCOM, can ensure that reactive power can be supplied by the DFIG during faults, supporting LVRT requirements of grid codes and post-fault recovery of grid voltage.

To ensure stable grid-connected operation of a DFIG-WECS during asymmetrical grid faults, its reactive power requirements must be properly managed. Zheng et al. [97] introduced a control strategy that maintains DFIG controllability under mild asymmetrical conditions. To handle more severe disturbances, a STATCOM is integrated as auxiliary equipment, accompanied by a voltage compensation mechanism and a capacity coordination method. The proposed coordinated control between the DFIG-based wind farm and the STATCOM enables sufficient positive-sequence reactive current injection to support the grid, while also suppressing oscillations in electromagnetic torque and DC-link voltage. Consequently, the scheme enhances the reliability and stability of both the wind farm and the broader power system during fault conditions.

When a CPC is triggered in a wind farm, the system shifts from supplying reactive power to consuming it, thereby worsening the fault conditions in the grid. These issues can be addressed through a real-time coordinated control system (RTCCS) [98] that manages the reactive power output of a DFIG during faults. The RTCCS operates based on the voltage level and the status of the CPC to ensure dynamic reactive power control. Since the DFIG’s reactive power demand rises when the CPC is activated, a STATCOM is incorporated within the RTCCS to provide necessary reactive power support. During voltage dips, the RTCCS directs the STATCOM to supply reactive compensation, stabilise the voltage at the PCC, and minimise CPC activation. This coordination enhances the LVRT capability of the wind farm and strengthens its stability and fault support performance.

Low-voltage conditions during symmetrical or asymmetrical faults can cause disconnection of DFIG-based wind turbines. Van Dai [99] proposed a coordinated protection approach that employs several devices—including a STATCOM, crowbar, series dynamic resistor (SDR), and DC chopper. In this method, the STATCOM operates under PI control, while the remaining devices respond according to threshold limits of rotor current and DC-link voltage. By coordinating these elements, the scheme prevents rotor–grid disconnection, stabilises the DC-link voltage, enhances the turbine’s dynamic performance, and improves voltage recovery at the DFIG terminals. As a result, voltage at the PCC, DC-link stability, and power oscillation damping are all improved, leading to enhanced LVRT capability and continuous energy supply to the grid.

Coordinated control significantly enhances system stability and improves LVRT compliance, especially when optimised by applying advanced algorithms, e.g., simulated annealing or ANFIS. However, these methods often assume ideal communication and measurement conditions, which may not be applicable in real-world grids. Moreover, optimisation-based approaches can be computationally intensive, limiting real-time deployment.

3.4.7. Fuzzy Logic-Based Controllers

During faults in the grid, the voltage will drop, and wind turbines will be disconnected, with a negative impact on generation continuity and the reliability of the system. A STATCOM can reduce the frequency and severity of these effects. If the STATCOM is provided with a traditional PI controller, it will be compromised by the shortcomings of traditional PI control, e.g., slow response and low accuracy. Utilising a Fuzzy PI control strategy [100] gives a faster and more robust response, reduces the fluctuation in the receiving terminal voltage, significantly improves the DFIG output power, ensures a smoother DC voltage and reactive power output of the STATCOM and generally improves the ability of the DFIG to ride through low voltages.

A STATCOM can mitigate the negative effects of both balanced three-phase and unbalanced faults on hybrid PV/DFIG wind generation systems. For STATCOM control, an Artificial Intelligence-based Proportional-Integral Fuzzy Logic Controller (PI FLC) [91] has been employed. Studies indicate that this controller effectively suppresses DC-link voltage oscillations and overvoltages in PV and wind systems during three-phase faults and double line-to-ground faults. Consequently, it enhances the DFIG LVRT capability and improves overall power quality.

Fuzzy logic controllers outperform traditional PI controllers by offering adaptive and robust responses under uncertain conditions. Their ability to handle nonlinearities makes them suitable for fault scenarios in hybrid systems. However, designing fuzzy rules and membership functions remains heuristic and system-specific, and this can be a hindrance to scalability.

3.4.8. Multi-Target Coordinated LVRT Strategy Incorporating a STATCOM Scheme

As a technology for enhancing the LVRT capability and stability of power systems with the DFIG- WECS, STATCOMs have a critical role in ensuring a safe and stable power grid operation and a sustainable integration of wind power technology. However, the LVRT requirements are becoming stricter; thus, the LVRT schemes must be optimised. One way of achieving this is a multi-target coordinated LVRT strategy that considers national standard requirements, the available STATCOM, optimised operation targets, and converter voltage and current limitations to develop an optimal LVRT scheme [101].

This scheme ensures, firstly, that the national LVRT operation requirements are complied with. Secondly, there are benefits of reduced electromagnetic torque fluctuations, improved active power output, protection of converters, and mitigation of power fluctuations during faults. The innovation of this research lies in proposing and providing a new technical approach for improving the LVRT performance of wind farms and the stability of power grid operation.

While multi-target coordinated LVRT strategies represent a significant advancement, their practical implementation faces challenges. These include the complexity of real-time optimisation under dynamic grid conditions, dependency on accurate system models, and potential computational burden for large-scale wind farms. Moreover, most studies assume ideal communication and control environments, which may not hold in weak grids or mixed-generation systems.

3.4.9. Conclusions

The control strategies of a STATCOM play a crucial role in enabling the DFIG-WECS to withstand voltage sags and grid disturbances while maintaining reliable operation. A foundation for regulating reactive power is provided by conventional PI and PID controllers, while enhanced approaches, e.g., decoupled schemes, coordinated controls, and optimisation-based controllers, increase responsiveness and fault tolerance. Advanced approaches utilising fuzzy logic, artificial intelligence, and hybrid strategies can further strengthen system resilience by addressing nonlinearities and uncertainties inherent in wind power integration.

3.5. Optimisation of STATCOM Controllers

Proper tuning of the STATCOM’s control parameters greatly influences its effectiveness to support the DFIG-WECS during system faults. Various optimisation techniques can enhance the reliability and FRT performance of the DFIG-WECS and hybrid renewable energy systems. Some of these strategies utilise metaheuristic optimisation techniques, while others integrate fuzzy logic and artificial intelligence (AI) with metaheuristics.

3.5.1. Metaheuristic Algorithms

The use of metaheuristic algorithms, individually or in a hybridised form with others, to tune the parameters of the STATCOM controller, has been proposed. When a grid is disturbed, e.g., by faults, DFIG wind plants may be assisted by a STATCOM in meeting the LVRT stipulations of the grid codes. The DO algorithm has been suggested for optimising the gains of the STATCOM’s PI controller [102] and performed better than the WCA, a hybrid WCA/PSO and PSO with the lowest overshoots in voltage, active, and reactive power obtained with DO-tuned STATCOM, resulting in improved LVRT capability.

Severe faults in power systems can lead to voltage sags, causing numerous adverse effects. A STATCOM can alleviate these issues and enhance the system’s dynamic response. To achieve optimal performance, the parameters of the STATCOM’s PI controller must be carefully tuned. Metaheuristic optimisation techniques—such as [103] ant colony optimisation (ACO), PSO, and hybrid ACO-PSO—can be employed to fine-tune the controller coefficients. Compared to classical or fuzzy logic-based PI controllers, these approaches offer superior performance by minimising overshoot during faults and reducing the time required for the system to return to steady-state operation. Additionally, metaheuristic methods are more efficient than traditional trial-and-error tuning and require less expert input than fuzzy logic approaches. By leveraging these techniques, a STATCOM can support the continuous operation of a wind-driven DFIG while ensuring compliance with grid code standards.

With the growing integration of wind energy in microgrids, issues such as generation loss and oscillations during both symmetrical and asymmetrical grid faults—particularly when DFIGs are connected to weak AC networks—make LVRT performance a critical concern. In this context, a STATCOM plays a key role in enhancing LVRT capabilities. The PI controller of the STATCOM can be optimally tuned using metaheuristic approaches [104], for instance, a hybrid of PSO and the artificial hummingbird algorithm (AHA). The resulting PSO-AHA-tuned STATCOM effectively mitigates power losses during faults, suppresses post-fault oscillations by regulating reactive power flow between the PCC and the microgrid, and significantly improves the overall LVRT response.

An effective method for determining the PI controller parameters of a STATCOM, aimed at supporting a DFIG during voltage dips caused by phase-to-ground and three-phase faults, is to tune the controller using [105] the WCA, PSO, or a hybrid WCA-PSO approach. Employing a STATCOM tuned with the WCA-PSO algorithm minimises voltage fluctuations and limits active and reactive power overshoots under different fault conditions, thereby improving the LVRT capability of the DFIG-WECS.

The DFIG systems in microgrids operating in grid-connected mode can suffer adverse consequences if severe faults occur in the main grid. If turbines fail to ride through the faults, they may be disconnected, leading to the loss of generation capability during faults. Moreover, post-fault oscillations could disrupt the grid’s stability, potentially affecting other connected equipment, resulting in grid instability and blackouts. A metaheuristically tuned STATCOM [106], utilising a hybrid grasshopper optimisation algorithm–PSO (GOA-PSO) approach to tune the PI controller, can solve the abovementioned problems. This technique exploits the complementary capabilities of the two; the proposed hybrid optimiser aims to achieve superior tuning efficiency and effectiveness compared to selected gains of the STATCOM controller. The STATCOM improves the LVRT performance and enhances the DFIG microgrid resilience.

Metaheuristic algorithms, e.g., PSO, ACO, and GOA, have demonstrated superior performance over classical tuning methods, but they have their own limitations. Many of these techniques rely on stochastic search of the search space, which can lead to inconsistent convergence, require extensive parameter tuning, and have a computational burden that may be significant for real-time applications. Some of these algorithms may be prone to local optima and therefore struggle to achieve global optima. Others may provide better global search capabilities at the cost of higher complexity.

Hybrid metaheuristic approaches leverage complementary strengths of individual metaheuristic algorithms, often outperforming approaches based on single metaheuristic algorithms in terms of accuracy and fault tolerance. However, these methods introduce additional complexity and may require careful coordination between algorithms, which can hinder practical utilisation. Moreover, most studies have tested these methods in simulation-based validation, and there is a gap in experimental or real-time implementation.

3.5.2. Integration of Fuzzy Logic and AI with Metaheuristics

Approaches that integrate fuzzy logic and AI with metaheuristics for dynamic reference generation and adaptive tuning of parameters of the STATCOM controller have also been proposed. The grid codes stipulate requirements regarding the duration of connection of DFIG turbines to the system during normal operation and under fault conditions. Using STATCOMs as sources of reactive power support aids the DFIG wind plants to ride through faults. To accurately track system voltage amplitude, an optimised double decoupled synchronous reference frame phase-locked loop (ODDSRF-PLL) can be implemented [107]. A FLC, utilising the ODDSRF-PLL output, generates dynamic reactive power references, which are then applied to a hysteresis-based direct power control (H-DPC) scheme. Optimal hysteresis bands are determined using a fuzzy adaptive PSO algorithm, enhancing STATCOM performance. This approach improves voltage profiles under normal and fault conditions, allowing the wind generator to stay connected during voltage sags while meeting the reactive power requirements of modern grid codes.

In hybrid PV/DFIG wind generator networks, the negative effects of both balanced three-phase and asymmetric faults on system performance can be mitigated by STATCOMs. These devices can be controlled using a PI FLC [81], with the PI parameters optimised via the Lightning Attachment Procedure Optimisation (LAPO) algorithm to minimise error signals. The PI FLC-controlled STATCOM has proven effective in alleviating voltage dips, providing active power support to wind and PV farms, suppressing overvoltages, and dampening DC-link oscillations caused by three-phase or double line-to-ground faults. This improves LVRT capability and enhances power quality.

The integration of fuzzy logic into the optimisation framework enhances adaptability under nonlinear and uncertain conditions. However, performance is heavily dependent on the design of the rule base and expert knowledge. Although combining fuzzy logic with metaheuristic algorithms can enhance dynamic response, it leads to increased design complexity and tuning effort. The question of how these methods perform under extreme grid disturbances or in multi-objective optimisation scenarios remains unanswered.

3.5.3. Conclusions

Optimisation of STATCOM controllers is a key enabler for enhancing the LVRT capability and dynamic stability of the DFIG-WECS and hybrid RESs. Optimisation-based schemes—especially those using fuzzy logic, AI, and metaheuristic algorithms—offer superior adaptability, faster convergence, and reduced voltage and power oscillations under fault conditions compared to classical controllers. On the other hand, hybrid optimisation techniques have demonstrated the potential to leverage complementary strengths of different algorithms to achieve robustness and efficiency of controller tuning. The research studies demonstrate that STATCOM controllers can, in addition to enhancing fault resilience and grid code compliance, improve the long-term stability and overall reliability of DFIG-WECS-rich power systems.

3.6. Certainty of Evidence of Results

To weigh the certainty or quality of evidence, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system has been used extensively in the medical field [108]. The standard GRADE system has the following five major domains: risk of bias (RoB), inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [109]. The following adaptations of GRADE were implemented to operationalise GRADE for this study:

- Risk of bias. Assessment was based on the five questions of the adapted CASP checklist, as presented in Section 2.4. These questions are related to clarity of objectives, design appropriateness, model validity, analysis rigour, and reproducibility.

- Inconsistency: Assessed by comparing LVRT improvement signals (e.g., PCC voltage recovery, reactive power support) across diverse grid conditions and fault scenarios.

- Indirectness: Judged by the extent to which simulation contexts reflect real-world networks (e.g., weak grids, realistic fault profiles).

- Imprecision: Evaluated based on reporting completeness (controller tuning, STATCOM sizing) instead of statistical intervals.

- Publication Bias: Not formally assessed but acknowledged as a potential limitation given the narrative nature of the synthesis.

The findings of the research studies consistently indicated an improvement in LVRT compliance and voltage recovery by STATCOMs. However, most studies relied on validation based on simulations only, with very limited hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) or field trials and heterogeneity in grid strength, controller tuning, and STATCOM sizing. Thus, the strength of the overall certainty is judged to be at a low-to-moderate level, i.e., a level at which the strength of evidence for large-scale deployment remains constrained by these methodological limitations.

3.7. Risk of Bias in the Results

The screening of the methodological quality of the publications was conducted based on the CASP process, adapted for engineering studies that involved a checklist of five questions, as was discussed in Section 2.4. When 40 studies that passed the eligibility phase were assessed using this process, 38 achieved a score of 5/5 and were included in the thematic synthesis. Two studies scored less than 4/5 and were excluded to ensure a high-rigour evidence base.

Besides the inclusion of only the studies passing the 5-item assessment, some residual risks remained in the review due to some other steps undertaken:

- The methodological quality assessment was performed by a single reviewer with no inter-rater statistics produced and assessed, as was described in Section 2.4.

- Many studies used evidence from simulations only, where model assumptions can introduce bias (e.g., optimistic parameterisation, ideal communications).

Based on the methodological assessment of the risk of bias as analysed using the tool in Section 2.4, the outcome of RoB is presented as low for the included set of studies, while the contextual limitations are acknowledged in Section 3.8 (Limitations of the Study).

3.8. Limitations of the Study

Despite Scopus being a broad and reputable source of the scholarly literature, the author acknowledges that the comprehensiveness of the SLR may be restricted by the exclusion of other databases, such as IEEE Xplore and Web of Science. In interpreting the findings of the SLR, this limitation should be recognised and considered.

Although there was strict adherence to the predefined CASP-based questions to mitigate bias discrepancies in the process of quality assessment for studies, the residual bias of selection risk introduced by one reviewer, without any inter-rate interventions, remains and should be considered.

In evaluating this SLR, some limitations that arise from the review process followed, the nature of evidence gathered from the studies, and the synthesis generated should be considered. The review-process limitations are firstly due to a single-database search of Scopus, leaving out databases, e.g., IEEE Xplore and Web of Science, due to resource constraints, but meaning some relevant records may have been excluded. Secondly, concentrating on publications produced in 2009–2024 means potential publications generated before or after this period may also have been missed. Lastly, the screening, quality assurance, and data extraction by a single reviewer could have increased the risk of selection and/or extraction bias.

The first aspect of evidence limitation is the predominance of simulation-based evidence, with limited use of HIL and field validations, limiting validation to real-life networks. There is significant heterogeneity in grid conditions, STATCOM placement/sizing, and controller tuning, limiting the cross-study comparison and precluding meta-analysis. Lastly, incomplete details in some studies (e.g., incomplete tuning details, missing grid-strength metrics) limit reproducibility and synthesis depth. Since narrative synthesis and engineering evidence format were utilised in this review, potential publication/reporting bias was not formally assessed.

Limitations observed in the synthesis indicate that, while the direction of effect is consistent, i.e., STATCOMs generally improve LVRT compliance, support PCC voltage, improve recovery time, and enhance damping, there is tempering of strength and generalisability of the conclusions because of the level of validation and heterogeneity of studies.

4. Trends and Possibilities for Future Research

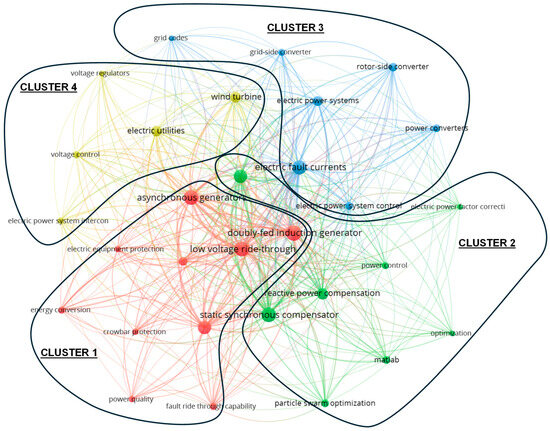

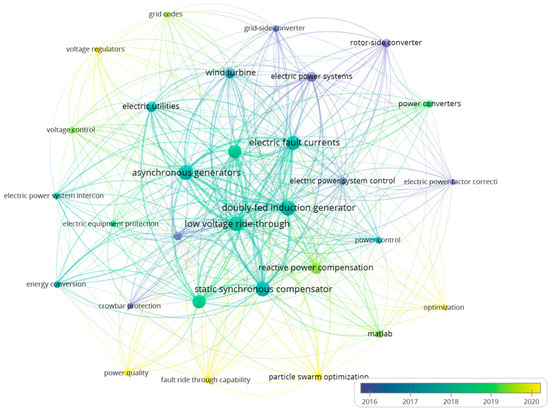

4.1. Description of the Approach