Abstract

This study aims to assess the energy efficiency of LED luminaires used in public road lighting by comparing manufacturer-declared photometric and electrical parameters with laboratory simulation results. The research also evaluates the performance of these luminaires across various road types and installation configurations to determine compliance with national and international standards. Eleven LED luminaires were tested using a rotating mirror goniophotometer in an ISO/IEC 17025-accredited laboratory. Simulations were conducted using Dialux Evo software across six road types (M1–M6) and three installation configurations (unilateral, bilateral, and staggered). Key parameters analyzed included brog (Lm), overall uniformity (U0), longitudinal uniformity (Ul), luminous efficacy (lm/W), power factor, and total harmonic distortion (THD) in voltage and current. Discrepancies were found between manufacturer-declared and simulation results, especially in higher-class roads (M1–M3), where up to 28.57% of luminaires failed to meet the minimum luminance requirements when tested. The study highlights the importance of validating manufacturer specifications through accredited laboratory testing. Overall, LED technology improves energy efficiency in public lighting, and inconsistencies in the power factor and luminance performance suggest the need for stricter regulatory oversight and more rigorous quality control. Simulation tools like Dialux Evo prove essential for optimizing lighting designs tailored to specific road types and traffic conditions.

1. Introduction

The estimated electricity consumption in Ecuador for the year 2022 was approximately 24,853.63 GWh. Public lighting services accounted for around 5.56% of this energy use [1]. Although this percentage may appear modest, it represents a substantial and continuous energy demand, particularly in urban areas where the lighting infrastructure operates throughout the night. The country has faced persistent challenges related to electricity supply, including generation deficits and grid limitations, which have underscored the urgency of implementing energy efficiency measures across all sectors. In response, the residential sector has increasingly adopted energy-efficient appliances and HVAC systems, while the commercial and public sectors have turned their attention to optimizing lighting technologies. Among these, public lighting stands out as a strategic area for intervention due to its high visibility, operational continuity, and potential for significant energy savings through technological upgrades [2].

The economic implications of efficient public lighting have garnered increasing attention since the widespread adoption of solid-state lighting (SSL) technologies. These systems, primarily based on light-emitting diodes (LEDs), have revolutionized the way urban environments are illuminated, offering substantial reductions in energy consumption and maintenance costs [3]. Beyond their technical advantages, SSL technologies have contributed to a broader understanding of the role of public lighting in enhancing urban functionality. Adequate public lighting is now widely recognized as a key enabler of nighttime productivity and human mobility. It facilitates safer and more comfortable conditions for both drivers and pedestrians, thereby improving traffic flow, reducing accident rates, and fostering a sense of security in public spaces [4]. As cities continue to expand and operate around the clock, the strategic deployment of energy-efficient lighting systems becomes essential not only for sustainability but also for supporting economic and social development [4].

In recent years, the implementation of lighting systems based on energy efficiency principles has gained momentum, turning efficient energy use into a national policy [5]. Meeting consumer demand while reducing environmental pollution positions LED technology as the ideal candidate for distribution systems [6].

Numerous studies have explored strategies to enhance energy efficiency in public lighting systems, with a particular focus on transitioning from traditional high-intensity discharge (HID) luminaires to modern solid-state lighting SSL technologies such as LEDs. This technological shift has been driven not only by the potential for energy savings but also by improvements in lighting quality, durability, and environmental impact [7,8]. In addition to the change in luminaire technology, research has emphasized the importance of intelligent lighting control systems, which enable the dynamic regulation of light output based on environmental conditions, occupancy, or time schedules. These systems contribute significantly to reducing unnecessary energy consumption and extending the operational life of the lighting infrastructure [9,10,11]. Furthermore, the long-term performance of lighting systems depends heavily on the lifespan and maintenance requirements of the luminaires. Studies have documented the degradation patterns of LED products, the influence of thermal and electrical stress, and the implications for maintenance planning and cost-effectiveness. Together, these aspects form a comprehensive framework for evaluating the sustainability and efficiency of public lighting systems in urban environments [12,13].

The widespread adoption of SSL technologies has played a pivotal role in significantly reducing energy consumption associated with lighting applications. This technological shift, driven by advances in semiconductor materials and optoelectronic design, has enabled higher luminous efficacy, longer operational lifespans, and lower maintenance requirements compared to traditional lighting systems. In many countries, including [Ecuador], this transition has been actively promoted through national energy efficiency programs and sustainability policies [14]. As a result, the implementation of SSL has not only transformed the lighting industry but has also necessitated the development and continuous revision of technical standards and regulatory frameworks. These standards, which govern both indoor and outdoor lighting products, aim to ensure performance consistency, safety, and environmental compliance, while also facilitating market integration and innovation [15].

In recent years, Ecuador has incorporated energy efficiency measures into its national energy policy as part of its commitment to sustainability and emission reduction. Among these measures, the promotion of LED lighting technology has been prioritized due to its capacity to significantly reduce electricity consumption and operational costs in public and residential sectors. Government initiatives such as the National Plan for Energy Efficiency and the replacement of traditional luminaires with LED systems in public lighting underscore the strategic role of this technology in achieving national energy goals.

Public policies proposed and implemented in Ecuador have actively promoted energy efficiency. For instance, it is mandatory to present photometric studies conducted in accredited laboratories [16,17,18]. Prior to the commercialization of luminaires in the Ecuadorian market [19,20], studies in Ecuador have examined the evolution, current structure, and development plans of the public lighting sector [21]. They have enabled the evaluation of specific lighting systems through case studies following the technological transition from traditional high-intensity discharge (HID) lamps to SSL systems, highlighting their positive energy impact [8].

The shift in lighting technology has proven to be a decisive measure for achieving efficient energy consumption in both indoor and outdoor lighting. Driven by policy and market demands, the entry of solid-state lighting products with physical and photometric characteristics indicating a certain level of quality remains limited. Nevertheless, this path leads toward efficient lighting systems, as LED performance continues to evolve thanks to ongoing research into the technical parameters of LED chip manufacturing [22]. Advancements in electronic control devices include drivers used in luminaires and their influence on luminaire performance, including photometric parameters, luminous flux (lm), installation efficiency, and the luminous intensity matrix of each luminaire within a system [23,24]. LED technology has already demonstrated effective results in reducing installed nominal power. For instance, a 32% reduction in energy consumption was observed when replacing a lighting system based on metal halide luminaires with LED technology [25]. These types of success stories have provided strong reliability and confidence in the use of this technology [3].

However, it is not sufficient to analyze only the light source; it is also essential to consider the intended use of the lighting system. Determining the environment and the functional requirements at the time of implementation and installation is crucial [26]. Hence, conducting a detailed study of the space to be illuminated is of great importance, including the photometric factors that the installation must meet according to the applicable recommendations and regulations for the specific type of road. When defining technical requirements, the design process focuses on meeting the prescribed parameters while ensuring visual comfort and safety for road users—both drivers and pedestrians—and maintaining energy efficiency [6].

Lighting designs take into account all necessary variables prior to system installation. Currently, several tools are available for lighting system design, which consider the road typology, the type of luminaires to be installed, and the use of simulation software, which is essential. Specifically, DIALux is a lighting design software that allows for both indoor and outdoor simulations. It provides design information by calculating illumination levels according to the required environment and includes a comprehensive module for road lighting. This module enables the definition of road types, pole arrangements and views, luminaire selection, and the inclusion of pedestrian crossings, roads with varying lane numbers, medians, sidewalks, and bicycle lanes [27]. The software offers a step-by-step guide to evaluate technical results in terms of system efficiency. Following the designer’s initial proposal, resources can be optimized by adjusting distances between lighting points, mounting heights, installation angles, luminaire tilt on poles, and their positioning [28].

This study presents an energy efficiency analysis based on the establishment of hypothetical conditions in a lighting design scenario, where photometric results provided by a manufacturer are compared with those measured by an independent laboratory accredited under the ISO/IEC 17025 standard [29]. The analysis considers key performance indicators such as uniformity levels, illuminance, and energy consumption [30]. This will utilize a rotating mirror goniophotometer to obtain the data required for this study [31,32,33].

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental procedures were carried out at the Lighting Laboratory of the Institute of Geological and Energy Research (IIGE), the only facility in Ecuador accredited under ISO/IEC 17025 for photometric measurements of lighting systems (Figure 1a,b). The primary objective of this study was to compare the luminous intensity distribution matrices provided by the manufacturer (ideal values) with those obtained through independent laboratory measurements (actual values).

Figure 1.

Experimental scheme for the measurement of luminous intensity distribution matrices. (a) LISUN 15 KVA power supply unit, Quito, Ecuador; (b) SENSING Type C rotating mirror goniophotometer, Quito, Ecuador.

The ideal photometric data were extracted from the manufacturer’s technical specifications, while the actual measurements were performed using a SENSING Type C rotating mirror goniophotometer, Quito, Ecuador (Figure 1b), powered by a LISUN 15 KVA power supply unit, Quito, Ecuador (Figure 1a). These measurements enabled the construction of real luminous intensity distribution matrices for the tested luminaires.

The experimental tests were carried out on public lighting luminaires connected to the National Interconnected System (SNI) of Ecuador, which operates at a nominal frequency of 50 Hz. The luminaires were supplied under a single-phase configuration of 220–240 V (±10%), representative of the typical low-voltage distribution used in urban public lighting circuits. For higher power models, three-phase 230/400 V configurations were also considered to simulate installation conditions on main roads. Power was provided through controlled laboratory setups replicating SNI characteristics, including photocell-based switching, overcurrent protection, and grounding systems, in accordance with the Ecuadorian Electrical Code (CEE) and INEN 2 229:2019 standards. This arrangement ensured that the electrical parameters—such as power factor, total harmonic distortion (THD), and luminous efficacy—were measured under realistic supply conditions equivalent to those found in the national distribution network.

To evaluate the impact of these differences on lighting performance, the ideal matrices were first used to design an optimized lighting system using DiaLux Evo 12.0 software. This simulation aimed to achieve optimal design parameters under ideal conditions. Subsequently, the measured matrices were applied to the same optimized design configuration, allowing for a direct comparison between the two scenarios.

The analysis focused on key lighting performance indicators, including overall uniformity, longitudinal uniformity, and average luminance. These metrics were assessed for both the ideal and measured luminous intensity distributions, providing insight into the practical implications of relying solely on manufacturer data versus independently verified photometric measurements. The number of luminaires used in this study with their corresponding characteristics can be seen in Table 1. The luminous flux values are those measured in the goniometer for each luminaire of the study. Additionally, the luminaire measurements in the goniometer test were performed with every five steps.

Table 1.

Description of the number of luminaires used for the study.

To assess the energy efficiency of the lighting system, both photometric and electrical parameters were analyzed. For the evaluation of the power quality, key electrical variables—including current, active power, and power factor—were measured using a Yokogawa WT310E precision power meter (Yokogawa Electric Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Additionally, total harmonic distortion (THD) values for both current and voltage were obtained using a SONEL PMQ 711 power network analyzer, SONEL S.A., Shvetsov, Poland (Figure 1a). These instruments provided high-resolution data essential for characterizing the electrical behavior of the lighting system under operational conditions. The combination of photometric and electrical measurements enabled a comprehensive analysis of system performance, with particular emphasis on energy consumption and power quality compliance.

To statistically validate the reliability of the observed non-compliance rates (), particularly those related to the average roadway luminance (), a statistical analysis was incorporated. Given the relatively small sample size () of simulated scenarios per road class and the presence of observed proportions close to zero, the 95% Wilson Score Confidence Interval (CI) was selected to estimate the true population proportion of failures. The Wilson CI is superior to the standard (Wald) interval for binomial proportions under these conditions, as it maintains more accurate coverage probabilities, preventing the lower bound from becoming negative and ensuring a more robust and statistically sound interpretation of the results’ significance. The limits of the CI are calculated using the following equation:

where is the observed proportion of non-compliant scenarios (failure rate), is the total number of simulated scenarios for the specific road class, and is the Z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level (for a 95% CI, ).

3. Results

The results of this study are organized into three main sections, each addressing a critical aspect of the lighting system’s performance, as follows:

- Photometric Analysis: This section presents the differences observed between the simulated photometric results based on the manufacturer’s ideal luminous intensity distribution matrices and those obtained from laboratory measurements. The comparison focuses on key parameters such as average luminance, overall uniformity, and longitudinal uniformity, highlighting the impact of using real versus ideal data in lighting design simulations.

- Efficiency Comparison: The second part of the results examines the differences between the declared luminous efficacy values and those measured under controlled laboratory conditions. This analysis provides insight into the reliability of manufacturer specifications and their influence on energy performance, particularly across different power ratings.

- Power Quality Assessment: Finally, the third section evaluates the electrical performance of the luminaires, focusing on power quality indicators. Measurements of the total harmonic distortion for current (THDi) and voltage (THDv), as well as power factor values, were obtained using specialized instrumentation. These results are analyzed in the context of compliance with international standards and their implications for system efficiency and grid compatibility.

3.1. Simulation Results with Ideal Factory Values and Simulation Results

Simulations were performed using Dialux Evo software according to road type, following the UNE-EN13201 standard [34]. It classifies roads used for pedestrian traffic as well as for various motorized vehicles. Variations in traffic and permitted speeds lead to a classification ranging from M6, with low traffic and minimum speeds, to M1, considered an arterial road due to its dense and continuous traffic.

The factory photometric matrix of the luminaire was taken, with which simulations were carried out with the three road layouts found in Ecuador. With these parameters, four new simulations were carried out with each luminaire matrix. These matrices were obtained from the goniophotometer test. The result of the simulation will be the average of the four matrices obtained from the test carried out.

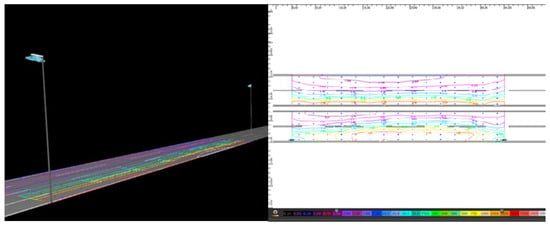

In addition to the aforementioned considerations regarding road type, three variants were simulated regarding the arrangement of the luminaires. The three variants introduced for this research were the implementation of a unilateral lighting system, with all luminaires on the right side of the road, and a roadway width of 7.3 m with two lines, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Simulation of a unilateral track in Dialux Evo.

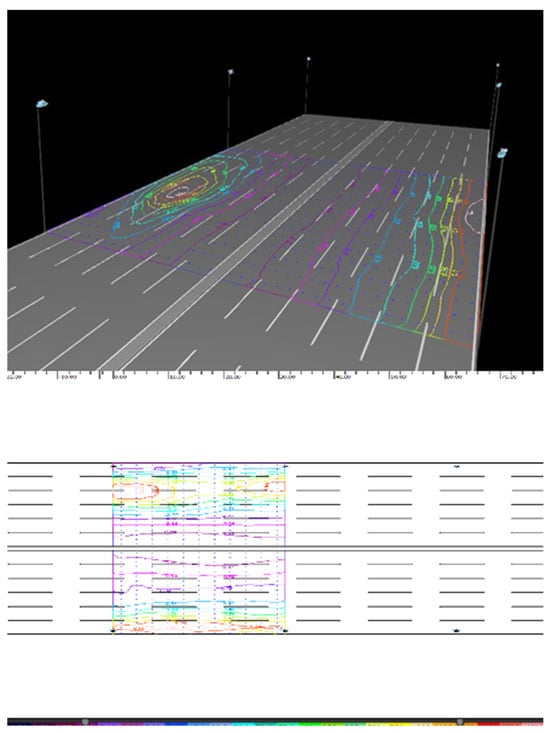

The road lighting configuration used in this study corresponds to a bilateral arrangement, in which luminaires are installed on both sides of the roadway. This setup is commonly employed in urban and interurban environments where symmetrical light distribution is required to ensure adequate visibility and uniformity across the entire road surface. Figure 3 illustrates the spatial arrangement of the luminaires, highlighting their positioning relative to the road axis and the typical mounting height used in the simulations and measurements. This is a two-way configuration with six lines for each way. This configuration was selected to evaluate the photometric and electrical performance of the luminaires under realistic installation conditions.

Figure 3.

Simulation of a bilateral track in Dialux Evo.

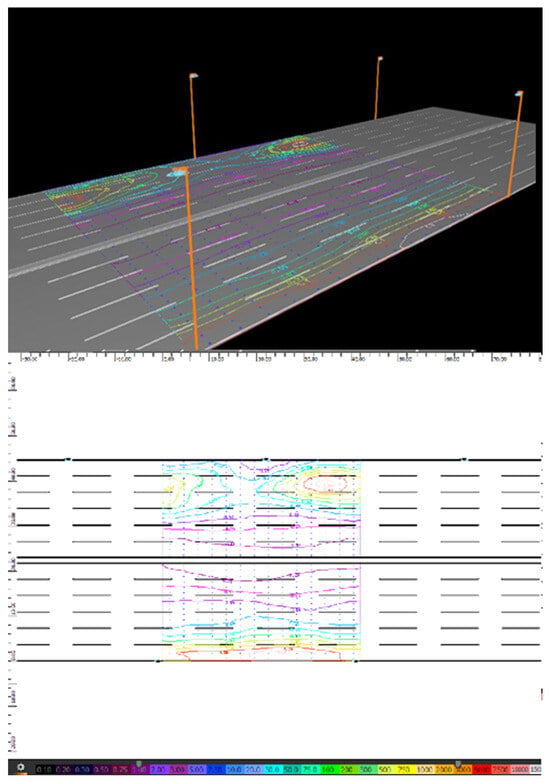

The third road lighting configuration analyzed in this study corresponds to a staggered bilateral arrangement, commonly referred to as a “staggered arrangement” structure. In this layout, luminaires are installed on both sides of the roadway, but unlike the conventional bilateral configuration—where fixtures are positioned directly opposite each other—this setup features alternating placements. Each luminaire is offset and located at the midpoint between two luminaires on the opposite side, creating a staggered pattern that enhances light distribution and reduces shadowing effects. Figure 4 illustrates this configuration, highlighting the spatial alternation and its implications for photometric performance. This is a two-way configuration with six lines for each way. This arrangement is particularly useful in scenarios where uniformity and visual comfort are prioritized, especially on roads with moderate to high traffic volumes.

Figure 4.

Bilateral pathway simulation in Dialux Evo.

In addition to the aforementioned considerations regarding the type of road and the arrangement of the luminaires, the following were taken into account regarding the distance between masts: a minimum distance of 15 m and a maximum of 50 m with a pitch of 1 m. Likewise, the height of the light point is a minimum of 6 m and a maximum of 10 m with a pitch of 0.5 m.

Another parameter that can be varied to better utilize the luminaire’s photometric characteristics during installation is the inclination of the luminaire-supporting arm, which was set within a range from 0° to 15° with a step width of 5°. For the light source projection, the parameter is from 0.5 m to 1 m with a step width of 0.5 m.

The factory values were compared with the average of the laboratory’s simulation results for the parameters of roadway luminance (), horizontal uniformity (), and longitudinal uniformity ().

The reliability and interpretation of the observed non-compliance rates for the average luminance () were enhanced through a statistical analysis. We calculated the 95% Wilson Score Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the true population proportion of non-compliant simulations across each road class. The observed failure rates () and their corresponding CIs are: as follows M1 ; M2 ; M3 ; M4 ; and M5 . Given that the lower bounds of the 95% CIs for classes M1 through M5 are all above zero, this statistical evidence supports the conclusion that the proportion of non-compliant scenarios based on measured data is significantly non-zero for these high-traffic road classes, validating the reported percentages as statistically reliable indicators of the failure risk.

The percentages indicated in the manuscript were calculated as the proportion of simulated scenarios that meet the regulatory requirement relative to the total number of scenarios evaluated for each road class and layout. Each scenario corresponds to a specific combination of the following:

- Road type (M1–M6).

- Luminaire layout (single-sided, double-sided, and alternating).

- Optimal distance between luminaires determined in the simulation.

For example, for class M3, 22 simulations were performed (n = 22). If two of these meet the overall uniformity requirement, the reported percentage is (2/22) × 100 ≈ 9%. This calculation was applied similarly for luminance and uniformity.

Since M6 is a type of road that can be considered a service road in an urban area with access to residential or community areas, or even in tertiary locations, its use is less common. Table 2 shows that 100% of the factory values meet the luminance requirement, and 66.67% of the simulation results exceed the minimum required value. Regarding horizontal uniformity, 100% of the factory values exceed the minimum required value, and 50% of the simulation results do not reach the minimum required value. Moreover, 100% of both factory and measured uniformities exceeded the minimum required value. The two-sided offset arrangement corresponds to an alternating installation on both sides of the track.

Table 2.

M6 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

The M5 highway is located in residential areas with little heavy-freight traffic. Table 3 shows that 70% of the factory-installed luminance values meet the minimum requirement, while 30% exceed it. However, 20% of the measured luminaires’ luminance levels fall below the minimum requirement. Analyzing the uniformity results, it is clear that 100% of the factory-installed horizontal uniformities exceed the minimum requirement, while 20% of the measured horizontal uniformities do not meet the minimum. Moreover, 100% of both factory-installed and measured longitudinal uniformities exceed the required value.

Table 3.

M5 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

The M4 road is located in residential areas with some heavy-freight traffic. Table 4 shows the factory luminance values, explained as follows: 50% of the luminaires meet the minimum requirement and the other 50% exceed it. In the case of the measured luminance, 10% do not reach the minimum required value. Regarding the uniformity results, 100% of the factory horizontal uniformities exceed the minimum requirement, while 25% of the measured horizontal uniformities do not meet the minimum value. Similarly, 15% of the factory longitudinal uniformities meet the minimum requirement, while the rest exceed it. Meanwhile, 25% of the measured longitudinal uniformities do not meet the minimum value.

Table 4.

M4 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

The M3 highway has medium traffic, with some heavy-goods vehicle traffic, and may be in commercial areas. Lighting is required to provide comfort and safety for both drivers and pedestrians. Table 5 shows that 27.27% of the factory luminance values meet the required minimum, while the rest exceed it. However, 18.18% of the measured luminance does not meet the required minimum. Analyzing the uniformity results, 9.09% of the factory horizontal uniformities meet the required minimum, while 18.18% of the measured horizontal uniformities do not meet the required minimum. Moreover, 18.18% of the factory longitudinal uniformities meet the required minimum, and 31.82% of the measured longitudinal uniformities do not meet the minimum.

Table 5.

M3 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

The M2 roads connect the main thoroughfares of major cities. The factory-installed luminance values are shown in Table 6. A total of 21.05% of the luminaires meet the minimum requirement, while the remaining luminaires exceed it. Of the measured luminance, 15.79% do not reach the minimum requirement. Regarding the uniformity results, 100% of the factory-installed horizontal uniformities exceed the minimum requirement, while 5.26% of the measured horizontal uniformities do not meet the minimum. Similarly, 100% of the factory-installed longitudinal uniformities exceed the required value, while 31.58% of the measured longitudinal uniformities do not meet the minimum requirement.

Table 6.

M2 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

M1 roads are the most important in the road hierarchy and require advanced and powerful lighting infrastructure to ensure traffic safety and efficiency under high-speed and high-volume conditions, providing a safe environment for both drivers and pedestrians in areas of very intense and fast-moving traffic. Table 7 shows the following factory luminance values: 14.29% of the luminaires meet the minimum requirement, while the remaining luminaires exceed it. Regarding the uniformity results, 100% of the factory horizontal uniformities and the measured horizontal uniformities exceed the minimum value. Similarly, 100% of the factory longitudinal uniformities exceed the required value, while 21.43% of the measured longitudinal uniformities do not meet the minimum required value.

Table 7.

M1 road configuration results. The results correspond to the optimal distance between luminaires obtained in the simulation (within the range of 15–50 m), which guarantees compliance with the regulatory parameters.

3.2. Differences Between Factory Efficiency and Measured Efficiency

Table 8 shows the difference in values found between the factory-declared electrical parameters and the errors obtained from the measured electrical parameters. It can be observed that, at low power levels, the measured efficiency is greater than that declared by the manufacturer, with a difference of approximately 11%. As the luminaire’s power increases, its efficiency is much closer to that of the factory, except in one case where the 8706-lumen luminaire delivers a considerably lower efficiency (−7.44%) than declared.

Table 8.

Description of the number of luminaires used for the study.

Regarding efficacy values, the assessment depends on each country’s energy policy. In the case of the Ecuadorian requirements [20], minimum efficiencies of 130 lm/W were established for LED luminaires. All measured efficacy values are within the established range, except for the luminaire that delivers 7144 lumens, with a measured efficacy of 126.35 lm/W. This luminaire also has the highest power than that declared by the factory; in all other cases, the power variation is within a 2% range. The national requirement was updated in 2024, increasing the efficacy for LED luminaires to values greater than 150 lm/W [35].

3.3. Power Quality Analysis

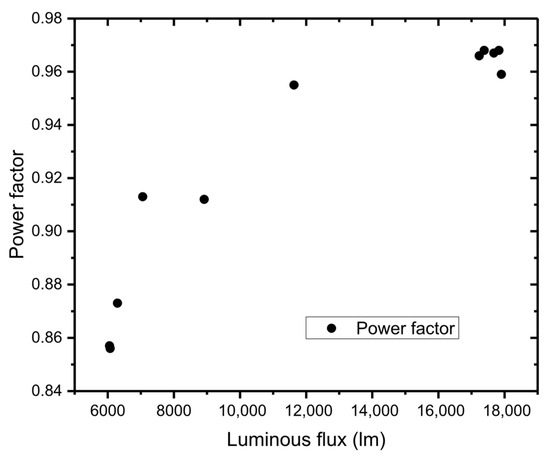

The parameters that will be analyzed in the article are the power factor and harmonic distortion in voltage and current. The importance of evaluating the power factor lies in that the closer its value is to 1, the more the consumed power is used as active power. In Ecuador, the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM) limits this parameter and requires in its technical specifications that the power factor be greater than 0.96 for LED luminaires [35]. Figure 5 shows that powers that deliver luminous flux values greater than 16,000 lumens comply with the power factor, except for one luminaire. On the contrary, powers that deliver a luminous flux of less than 16,000 lumens have a power factor below the MEM requirements, even reaching values close to 0.85.

Figure 5.

Power factor behavior as a function of the luminous flux of LED luminaires.

Regarding the assessment of harmonic distortion, its evaluation is essential for understanding the deformation of voltage and current waveforms, which can negatively affect other users connected to the same electrical network. Distorted waveforms may lead to increased losses, equipment malfunction, and reduced system reliability.

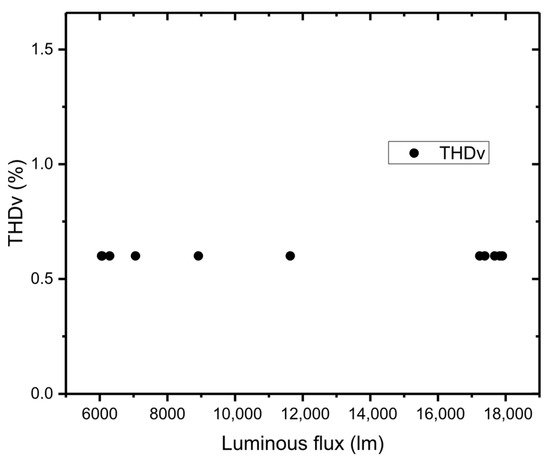

Figure 6 presents the results for the Total Harmonic Distortion of Voltage (THDv), showing a consistent value across all tested luminous flux levels. Regardless of the power output of the luminaires, the THDv remained stable at 0.6%, which is significantly below the maximum threshold of 8% established by national low-voltage regulations. This indicates excellent voltage waveform quality and minimal harmonic interference from the luminaires.

Figure 6.

Total harmonic distortion of voltage as a function of the luminous flux of LED luminaires.

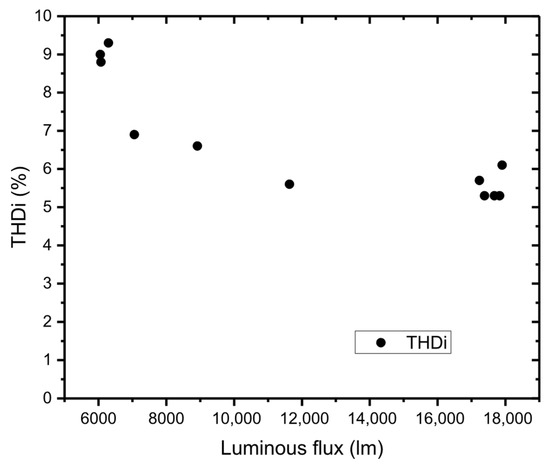

Figure 7 illustrates the Total Harmonic Distortion of Current (THDi), where the highest distortion values were observed at lower luminous flux levels. Despite this, all luminaires complied with the requirements set by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM), which stipulate a maximum THDi of 20%. The highest measured value was approximately 9%, confirming satisfactory performance across the entire sample. These results suggest that the luminaires tested exhibit acceptable harmonic behavior, contributing positively to power quality and system stability.

Figure 7.

Total harmonic distortion of the current as a function of the luminous flux of LED luminaires.

Measurements indicate that the power factor is the parameter that falls outside the limits established by technical specifications, especially at low power levels, and this is also consistent with maximum harmonic distortion values. The power factor is capacitive, which leads to an increase in capacitive reactive power, which in turn causes increased voltage levels in the grid. This is especially significant considering that the low-voltage grid is generally shared with the public lighting grid.

4. Discussion

The results of this study confirm that while LED technology offers significant potential for improving the energy efficiency of public lighting systems, discrepancies between manufacturer-declared parameters and laboratory simulation results remain a critical concern. In particular, the differences in luminance performance across road categories (up to 28.57% in M1 roads) highlight the risks of relying exclusively on catalogued values for design and regulatory approval. These findings are consistent with previous research reporting deviations between nominal and measured photometric parameters in SSL products [7,22,25], which can compromise both visual comfort and safety in real-world applications.

The analysis also shows that uniformity values tend to be more consistent than luminance levels, which suggests that road lighting designs based solely on factory data may provide acceptable spatial distribution but still fail to achieve the minimum brightness requirements. This is particularly relevant for higher-class roads (M1–M3), where compliance with luminance thresholds is critical for traffic safety. Similar results have been reported in comparative studies between HID and LED luminaires, where underperformance in luminance was found, despite improvements in efficacy and maintenance costs [8,25].

From the perspective of energy performance, measured efficiencies were generally within the regulatory thresholds established in Ecuador (≥130 lm/W) and comparable to those reported in international standards [14,15]. However, the introduction of stricter national requirements (≥150 lm/W from 2024) poses challenges for certain products, as evidenced by the luminaire with 7144 lm, which did not meet the updated efficiency criterion. This finding emphasizes the need for the continuous adaptation of product design and manufacturing processes to comply with evolving energy efficiency policies.

Setting a limit (≥150 lm/W) reflects global trends toward greater energy efficiency in solid-state lighting (SSL), which aims to reduce global emissions from the lighting sector.

Meeting this requirement calls for advances in LED chip efficiency, thermal management, and optical design optimization. Local and imported luminaires currently operating near the lowest efficiency range, such as the 7144 lm model evaluated in this study, may require redesigns involving improved driver circuits, higher quality phosphor materials, or more efficient heat sinks. Stricter quality control protocols must also be established to remain competitive.

This increase can be transformed into quantifiable benefits, including reduced operating costs for municipalities and extended luminaire life due to reduced thermal stress. However, the regulatory change highlights the need for continuous verification mechanisms and collaboration between laboratories, industry, and regulatory bodies to ensure that the declared performance values are realistic and verifiable under standardized test conditions.

The assessment of power quality further reveals important limitations. While the THDv and THDi remained within acceptable ranges and aligned with earlier studies on LED power electronics [23,24], the power factor frequently fell below the minimum required value of 0.96, falling as low as 0.85. This capacitive behavior, especially in low-power luminaires, may introduce additional stress on the distribution grid, leading to reactive power issues. Comparable concerns have been documented in large-scale LED deployments [25], suggesting that future regulatory frameworks should pay closer attention not only to efficacy but also to power quality parameters.

Regarding power measurement using simulations and factory information, although the THDv and THDi remained within acceptable ranges and in line with previous studies on LED power electronics [23,24], the power factor (PF) frequently fell below the minimum required value of 0.96, reaching values as low as 0.85. This behavior was particularly evident in luminaires with lower luminous flux levels, where low-cost, simplified power conversion controller circuits without an active power factor correction (PFC) were used. These designs typically employ single-stage or passive PFC topologies that cannot maintain a high PF under light-load conditions, resulting in a more pronounced capacitive character.

Technically, the reduction in PF at low power levels is due to the non-linear relationship between input current and voltage, caused by the presence of electrolytic capacitors and switching devices within the controller. As the operating current decreases, the input current waveform becomes increasingly distorted, increasing phase shift and reactive power components. This not only reduces the overall efficiency of the system, but it also places additional reactive power demands on the distribution network, especially when thousands of luminaires are used in street lighting systems. Similar effects have been observed in large-scale LED installations, where the cumulative low PF behavior has caused voltage instability in the grid and transformer overload [25].

Overall, the results underline the necessity of a mandatory independent verification of both photometric and electrical parameters in accredited laboratories before luminaires are introduced into public infrastructure. The integration of simulation tools such as Dialux Evo proved effective in identifying discrepancies and optimizing designs. However, reliance on unverified manufacturer data can result in non-compliance with international standards (UNE-EN 13201) and potentially unsafe lighting conditions.

This study contributes to the ongoing discussion about the balance between technological innovation, regulatory stringency, and urban sustainability. Ensuring high-performance, reliable LED systems is not only a matter of energy savings but also a public safety priority. Future research should explore the integration of intelligent lighting control systems—such as adaptive dimming, motion-based activation, and wireless communication protocols—to enhance energy management, extend luminaire lifespan, and improve safety in dynamic traffic environments. Evaluating the real-world performance of these smart systems under varying climatic and operational conditions will be essential in determining their long-term benefits and informing national lighting policies.

5. Conclusions

The proper identification of the road type where a lighting system is to be implemented is essential for designing solutions that comply with both safety and energy efficiency standards, as dictated by traffic demands and road morphology. This study demonstrates how luminaires can be adapted to different road categories (M1–M5) based on their power ratings, ensuring compliance with the minimum requirements for luminance, overall uniformity, and longitudinal uniformity.

The comparative analysis between manufacturer-declared photometric values and those obtained through accredited laboratory measurements revealed significant discrepancies. Specifically, the differences in luminance values were 28.57% for M1, 15.79% for M2, 18.18% for M3, 10% for M4, and 20% for M5. Although the manufacturer-declared data met the minimum requirements for the three evaluated parameters, the laboratory results showed that luminance values fell below the required thresholds in all cases.

Regarding electrical performance, the measured efficiencies for low-wattage luminaires were generally higher than those declared by the manufacturer, with an average difference of approximately 11%. As the wattage increased, the gap between declared and simulation efficiencies narrowed. However, one exception was observed, where the measured efficiency was 7.44% lower than the declared value. Given the limited sample size relative to national lighting inventories, these findings suggest the need for more rigorous monitoring and verification of manufacturer claims.

In terms of power quality, the measured power factor values showed inconsistencies with the required minimum of 0.96, reaching values as low as 0.85 in some cases. Nevertheless, total harmonic distortion values for voltage (THDv) and current (THDi) remained within acceptable limits. THDv was consistently low at 0.6%, well below the maximum allowable value of 8%, and THDi did not exceed 9%, remaining under the 20% threshold.

These results underscore the importance of the independent verification of photometric and electrical parameters in lighting systems, particularly when used in public infrastructure. Ensuring compliance with technical standards not only improves energy efficiency but also enhances safety and reliability for road users.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and C.V.; methodology, C.C., B.S., and C.V.; software, C.C. and B.S.; validation, C.V.; formal analysis, C.C.; investigation, C.C.; resources, C.C. and J.M.-G.; data curation, F.E. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and F.E.; writing—review and editing, J.M.-G. and C.V.; visualization, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. and J.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by University Internacional SEK, and this research was supported by Universidad Internacional SEK, grant number P121819.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Geological and Energy Research Institute for the funding and the CELEC TRANSELECTRIC business unit for lending their laboratory facilities, which is where this research was carried out. This study is a component of the Parque de Energias Renovables project P121819, which was started by Universidad Internacional SEK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Galindo, S.P.; Borge-Diez, D.; Icaza, D. Energy Sector in Ecuador for Public Lighting: Current Status. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, C.; Arteaga, J. Detrás de La Eficiencia Energética de Las Luminarias Led. CIEEPI—Col. Ing. Eléctr. Electrón. Pichincha 2016, 37, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F. Posibles Efectos Socioeconómicos de La Eficiencia Energética de Los Nuevos Sistemas de Iluminación Basados En Tecnología LED. Cienc. Ing. Apl. 2018, 1, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A.; Hurtado, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.C. Impact of Public Lighting on Pedestrians’ Perception of Safety and Well-Being. Saf. Sci. 2015, 78, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Candia, J.; Curt, M.D.; Domínguez, J. Understanding the Access to Fuels and Technologies for Cooking in Peru. Energies 2022, 15, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F.; Castro, M.Á.; Rodríguez, F. Energy Efficiency in Public Lighting Systems Friendly to the Environment and Protected Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, I.; Ciurescu-ţibrian, M. Energy Efficiency Increase in Public Lighting Systems. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. C Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2021, 83, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, G.; Peralta, D.; Molina, J.; Chasi, C.; Martínez-Gómez, J. Comparative Analysis of MH Versus LED Prototype Luminaires: Case Study for Lighting Public Areas. In International Conference on Innovation and Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1041, pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consilvio, A.; Sanetti, P.; Anguita, D.; Crovetto, C.; Dambra, C.; Oneto, L.; Papa, F.; Sacco, N. Prescriptive Maintenance of Railway Infrastructure: From Data Analytics to Decision Support. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems (MT-ITS), Cracow, Poland, 5–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbradica, M.; Trpovski, Z. Advanced Street Lighting Maintenance Using GPS, Light Intensity Measuring and Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation (HPCS), Bologna, Italy, 21–25 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Deshpande, A.; Ho, S.S.; Ku, J.S.; Sarma, S.E. Urban Street Lighting Infrastructure Monitoring Using a Mobile Sensor Platform. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 4981–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lin, J.; Zhang, L.; Kumar, U. A Dynamic Prescriptive Maintenance Model Considering System Aging and Degradation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 94931–94943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, Y.M.; Akilesh, S.; Karthik, S. Prasanth Intelligent Street Lights. Procedia Technol. 2015, 21, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valetti, L.; Floris, F.; Pellegrino, A. Renovation of Public Lighting Systems in Cultural Landscapes: Lighting and Energy Performance and Their Impact on Nightscapes. Energies 2021, 14, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-López, P.I.; Loor-Castillo, G.A. Metodología de control para la gestión de mantenimiento de alumbrado público en el cantón Machala. MQRInvestigar 2024, 8, 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, C.; Castro, M.A.; Rodriguez, F.; Espin, F.; Falconi, N. Optimization of the Calibration Interval of a Luminous Flux Measurement System in HID and SSL Lamps Using a Gray Model Approximation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Fifth Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), Cuenca, Ecuador, 12–15 October 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, C.; Juiña, D.; Iturra, F.; Silva, B.; Barona, D. Methodology for Declaration of Conformity Under ISO/IEC 17025 Associating Confidence Levels and Risk Analysis. In International Conference on Innovation and Research—Smart Technologies & Systems; Vizuete, M.Z., Botto-Tobar, M., Casillas, S., Gonzalez, C., Sánchez, C., Gomes, G., Durakovic, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Juiña, D.; Silva, B.; Velásquez, C. Análisis de Riesgo de La Declaración de Conformidad de La Potencia de Luminarias a Un Nivel Determinado de Confianza. Kill. Téc. 2024, 7, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, C.; Steg, L. The effect of information and values on acceptability of reduced street lighting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulla-Galindo, S.; Borge-Diez, D.; Icaza, D. Energy sector and public lighting. In Sustainable Energy Planning in Smart Grids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Icaza, D.; Borge-Diez, D.; Galindo, S.P. Analysis and Proposal of Energy Planning and Renewable Energy Plans in South America: Case Study of Ecuador. Renew. Energy 2022, 182, 314–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scozzina, E.F.; Marder, V.; Ramírez, J.L.; Fontana, J.L.; Lin, D.J. Desempeño de Productos: Aspectos Tecnológicos Más Relevantes de Los Dispositivos y Luminarias LEDs. Extens. Innov. Transf. Tecnol. 2021, 7, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusil, C.; Arcos, H.; Espin, F.; Velasquez, C. Analysis of Harmonic Distortion of LED Luminaires Connected to Utility Grid. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Andescon, Quito, Ecuador, 13–16 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brusil, C.; Espín, F.; Velásquez, C. Effect of Temperature in Electrical Magnitudes of LED and HPS Luminaires. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Syst. 2021, 12, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Rojas-Sola, J.I.; Gago-Calderón, A. Electrical Consequences of Large-Scale Replacement of Metal Halide by LED Luminaires. Light. Res. Technol. 2016, 50, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F.; Rodríguez, F.; Castro, M.Á. Heat Transfer Modeling in Road Lighting LED Luminaire. In Proceedings of the 11TH International Conference on Mathematical Modeling in Physical Sciences, Belgrade, Serbia, 5–8 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerry, E.; Gǎlǎtanu, C.D.; Canale, L.; Zissis, G. Optimizing the Luminous Environment Using DiaLUX Software at “Constantin and Elena” Elderly House—Study Case. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 32, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, J.; Cuji, C. Diseño y Evaluación de Un Sistema Fotovoltaico Aislado Para Iluminación En Vías Rurales y Carga de Vehículos Eléctricos Basado En Un Enfoque Multipropósito. Rev. Técnica Energía 2024, 20, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 17025; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- De La Bastida, R.; Velásquez, C.; Espín, F. Influencia de La Automatización de Ensayos de Flujo Luminoso Total En El Cálculo de Incertidumbre Combinada y En El Tiempo de Ejecución Del Ensayo. FIGEMPA Investig. Desarro. 2018, 5, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F. Cálculo de La Incertidumbre Combinada En Un Goniofotómetro de Espejo Rotante Tipo C y Una Esfera de Ulbricht. I + T + C—Res. Technol. Sci.—Unicomfacauca 2015, 1, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F.; Arteaga, J. Stray Light Measurement with Solid State Light Luminaire in a C-Type Goniophotometer with Rotating Mirror. In Proceedings of the CIE 2016: Lighting Quality & Energy Efficiency, Melbourne, Australia, 3–5 March 2016; pp. 753–761. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, C.; Espín, F. Metodología Para Cuantificación de Luz Intrusa En Fotometrías Obtenidas En Un Goniofotómetro. I + T + C—Res. Technol. Sci.—Unicomfacauca 2016, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13201; Standards for Road Lighting All Parts. European Standards: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- García-Tenorio, F.A.; Simisterra-Quintero, J.J.; Barre-Cedeño, K.N.; Bautista-Sánchez, J.V.; Chere-Quiñónez, B.F. Evaluación técnica, económica y ambiental del cambio del sistema de alumbrado público de la ciudadela Costa Verde-Esmeraldas a tecnología LED. Sapienza Int. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 3, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.