Abstract

Dual Carbon Goals are driving transformation in China’s power system, where increased renewable energy penetration is accompanied by heightened fluctuations on the generation and load sides. Energy storage and microgrid coordination have emerged as key solutions. However, existing research faces the challenge of balancing microgrid operations, energy storage services, and the alignment of user demand with stakeholder interests. This paper establishes a tripartite collaborative optimization framework to balance multi-stakeholder interests and enhance system efficiency, assuming fixed energy storage capacity. Centering on a principal-agent game between microgrid operators and consumer aggregators, energy storage service providers are integrated into this dynamic. Microgrid operators set 24-h electricity and heat pricing while adhering to tariff constraints, prompting consumer aggregators to adjust energy consumption and storage strategies accordingly. The KKT conditional method is employed to solve the model, deriving optimal user energy consumption strategies at the lower level while solving marginal pricing equilibrium relationships at the upper level, balancing accuracy with information privacy. The creative contribution of this article lies in the first construction of a tripartite collaborative optimization architecture in which energy storage service providers are embedded in a game of ownership and subordination. It proposes a dynamic coupling mechanism between pricing power, energy consumption decision-making, and energy storage configuration under fixed energy storage capacity constraints, achieving a balance of interests among multiple parties. By building a case study using MATLAB (R2022b), we compare operation costs, benefits, and absorption rates across different scenarios to validate the framework’s effectiveness and provide a reference for engineering applications.

1. Introduction

Currently, rapid global industrialization has led to massive consumption of fossil fuels, with energy and environmental issues becoming increasingly prominent. Concurrently, traditional power systems suffer from low energy utilization efficiency and imbalances between energy supply and demand, creating an urgent need to develop more advanced, intelligent, and clean power systems to address these challenges. Against this backdrop, the concept of multi-energy microgrids has emerged. These systems offer advantages such as flexible operation modes and coordinated control of multiple energy sources, enabling effective integration and utilization of various energy forms. In addition, advancements in energy internet technology and electricity market reforms have created favorable conditions for the coordinated operation of regional multi-energy microgrids across physical, informational, and market dimensions [1,2]. Currently, to achieve coordinated and sustainable energy supply and economic development, the concept of the energy internet continues to evolve. It has expanded from the initial integration of energy and internet technologies into a complex system architecture featuring coordinated generation, transmission, consumption, and storage. Relevant standards and technical frameworks are also undergoing continuous refinement [3]. Notably, with the large-scale integration of distributed PV installations on the consumer side, the energy supply end exhibits pronounced intermittent and random characteristics. For instance, residential rooftop PV output fluctuates frequently due to variations in sunlight intensity, while the output peaks and troughs of commercial and industrial photovoltaic clusters often misalign with user load peaks and troughs. This places higher demands on the flexibility of power dispatch within the energy internet, requiring not only real-time balancing of fluctuations in generation and load but also efficient integration of renewable energy to avoid curtailment. The traditional passive dispatch mode is increasingly inadequate to meet these needs [4,5].

To date, game theory has become a core theoretical tool for optimizing distribution network operations due to its ability to precisely characterize multi-agent conflicts and synergies. Extensive research has been conducted by scholars worldwide in this domain. In the context of community energy internet scenarios, References [6,7] focus on the strategic interaction between microgrid operators and prosumer groups. By analyzing the game-theoretic relationship between the former’s pricing strategies and the latter’s electricity load, these studies achieve preliminary optimization of localized energy systems through hierarchical decision-making: operators set electricity prices while prosumers adjust their loads. However, such models exhibit clear limitations by focusing solely on electricity prices as decision variables, excluding heat prices from optimization. Reference [8] adopts a multi-energy vendor as the decision-maker, embedding variable heat price scenarios within electricity pricing logic. It constructs a distributed collaborative optimization model for community multi-energy systems using a leader-follower game framework, clarifying the impact mechanism of heat price fluctuations on user energy choices. Reference [9] proposes a distributed cooperative optimization operation strategy for community multi-energy systems based on requester–responder games. It positions multi-energy suppliers as leaders, while new energy cogeneration operators and load aggregators act as followers, solving for the interactive strategies pursued by all parties to achieve optimal objectives.

However, the aforementioned studies share a common shortcoming: they fail to consider the pivotal role of energy storage devices in optimized operation. In fact, as a key enabler for smoothing load fluctuations and enabling time-shifted energy transfer, energy storage significantly enhances the flexibility of distribution network regulation. Reference [10] constructs a coordinated optimization model for distribution network demand-side pricing, energy storage operation strategies, and capacity allocation, achieving maximum network benefits through multivariable coupled optimization. Reference [11] further focuses on energy storage scenarios, designing a centralized energy storage service mechanism tailored to the consumption characteristics of multiple photovoltaic producers and consumers within community energy internet systems.

The sharing economy, leveraging its core advantages of resource integration and on-demand allocation, has demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in reducing industrial costs and enhancing resource utilization, providing valuable insights for model innovation in the energy sector [12]. Reference [13] designed a day-ahead scheduling model for residential users based on centralized energy storage within community multi-energy systems incorporating cogeneration and photovoltaics. By coordinating energy supply and demand through storage systems, the model not only enhances overall residential user benefits but also creates stable profit opportunities for storage operators. Reference [14] focuses on industrial scenarios, establishing a collaborative operation model between centralized storage and diverse industrial users based on their load characteristics, demonstrating outstanding economic advantages. Reference [15] introduces the concept of cloud energy storage, integrating dispersed storage resources through a cloud platform to form virtualized storage services. It systematically outlines optimization directions and development prospects for cloud energy storage, laying a theoretical foundation for centralized storage applications. Reference [16] addresses the growing number of user-side energy storage systems by investigating their investment costs and value assessment. Through analyzing various storage system costs and employing a novel evaluation model that integrates multiple benefits of energy storage systems, it establishes a comprehensive decision-making framework for evaluating energy storage systems. Reference [17] proposed a strategy that involves the leasing of shared energy storage (SES) to establish a collaborative micro-grid coalition (MGCO), enabling active participation in the dispatching operations of active distribution networks (ADNs). Reference [18] presented a collaborative model of the MEMG community comprising electric, thermal, cooling, and an emerging hydrogen network with shared hybrid energy storage (SHES). The SHES comprises electric storage, a heat storage tank, and a hydrogen storage system to serve multiple demands within MEMGs.

The above studies still exhibit significant limitations: On one hand, they fail to comprehensively consider flexible resources on the user side, neglecting to fully integrate key regulatory measures such as combined electricity–heat demand response and electric heating. Reference [19] developed a collaborative optimization dispatch model integrating energy storage devices, focusing on the dispatch potential of massive controllable loads on the demand side of community integrated energy systems. Reference [20] pioneered a gas–electricity–heat multi-energy flow price-responsive model by analogizing the peak-off-peak electricity pricing mechanism based on the commodity attributes of natural gas and electricity. This led to an economic dispatch model for regional integrated energy systems targeting minimized operating costs, while holistically considering supply–demand balance and energy storage operation constraints. With the refinement of clean energy mechanisms and advancements in combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) technologies, Reference [21] further designed an economic dispatch strategy incorporating demand response and power mutual support among microgrids. Its objective function comprehensively covers gas costs, wind, solar, storage operation and maintenance expenses, and transaction gains or losses between microgrids and the main grid. On the demand side, considering the elasticity of electric heating loads and the diversity of heating modes, reference [22] established an integrated demand response (IDR) model, and a flexible IDR price compensation mechanism was introduced. In this paper, an electricity–heat integrated energy storage supplier (EHIESS) containing electricity and heat storage devices is proposed to provide shared energy storage services for multi-microgrid system in order to realize mutual profits for different subjects [23]. Reference [24] established a mechanism model for energy market participants and developed a joint market clearing model for electric heating to maximize global profits, considering multi energy storage.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper investigates community-based multi-energy microgrids involving microgrid operators and multiple users. Within a core framework where the microgrid operator sets electricity and heat prices, the study integrates user-side electricity and heat demand response, electric heating equipment, and centralized energy storage mechanisms into a unified optimization system. It constructs a multi-energy microgrid operation optimization model based on Stackelberg games and centralized energy storage. Through computational simulations, the model’s effectiveness in balancing multi-party interests and enhancing system operational efficiency is validated.

2. Community-Based Multi-Energy Microgrid Framework

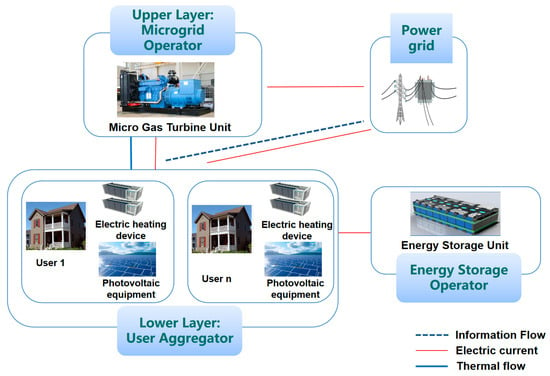

To achieve centralized management and optimized dispatch, dispersed clusters of distributed users within the microgrid system can be aggregated and abstracted into a single user aggregation entity. Under this framework, the core participants in a community-based multi-energy microgrid are defined as three key roles: the microgrid operator responsible for overall operational control, the user aggregator representing consumer-side energy demand, and the energy storage operator specializing in shared energy storage services. The specific architecture and interaction relationships for this scenario are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of a Community-Based Multi-Energy Microgrid Framework.

Microgrid operators serve as critical intermediaries between the power grid and end users, delivering core value across two dimensions: energy trading and physical energy supply. In the market transaction dimension, microgrid operators operate through market-based mechanisms: by accurately assessing regional energy supply–demand dynamics, grid electricity price fluctuations, and user consumption patterns, they establish differentiated electricity and heat pricing systems that balance economic viability and rationality. Leveraging this pricing mechanism, they establish stable energy trading relationships with user aggregators. While meeting user energy demands, they achieve balanced and enhanced operational profitability through reasonable spreads between energy procurement costs and sales prices. In the physical operation dimension, microgrid operators possess independent energy production and supply capabilities. Their operational side is equipped with distributed energy generation facilities such as gas turbines. These facilities efficiently convert clean energy sources like natural gas to simultaneously provide high-quality electricity and thermal energy to the user side, forming a combined heat and power (CHP) energy supply model. This approach ensures the stability of users’ energy demands while enhancing the overall energy utilization efficiency within the microgrid system.

Assuming conventional energy storage primarily provides storage services to the user side, its core objective is to enhance the flexibility of users’ own load adjustment. Through the charging and discharging operations of the energy storage system, users can flexibly allocate the timing of energy storage and usage based on their own energy consumption needs and external energy supply conditions. This effectively smooths out energy consumption peaks and troughs, optimizing the load curve. From an operational charging perspective, service fees for conventional energy storage are calculated based on the actual energy capacity stored or withdrawn by the user. That is, service charges are levied according to the specific capacity scale utilized.

User-side loads are primarily composed of electrical and thermal demands, with each user equipped with an independent photovoltaic system to form self-sufficient basic energy supply units. Regarding electricity procurement and sales pathways, given that the microgrid operator’s electricity sales price is lower than the grid-side rate, this study stipulates that users exclusively purchase electricity from the microgrid operator while selling electricity uniformly to the grid. This establishes a transaction model featuring one-way electricity procurement and centralized electricity sales.

From the perspective of electricity supply–demand regulation mechanisms, two key scenarios exist on the consumer side. When self-generated solar power cannot cover electricity load demands, consumers have dual options, either purchasing electricity from microgrid operators or drawing stored energy from their own conventional energy storage devices. When PV generation exceeds demand, surplus electricity similarly has two disposal pathways: it can be sold to the grid for revenue or stored in conventional energy storage devices to reserve energy for future needs. At the thermal load supply level, a dual-source coordination model ensures demand fulfillment, part of the thermal energy is produced and supplied by micro-combustion units on the microgrid operator side, while the other part is generated by converting electricity into heat through user-side electric heating equipment.

In the model constructed in this paper, users break free from single-source constraints for acquiring electricity and thermal energy, with diversified energy sources significantly enhancing energy utilization flexibility. Operational logic among microgrid participants is clearly defined and synergistically coordinated. Microgrid operators formulate optimal electricity purchase and sale prices during the day-ahead planning phase based on the next day of time-of-use grid tariffs. Users, in turn, optimize their daily electricity and heat load distribution by integrating the microgrid operator’s electricity and heat prices with the operational costs of conventional energy storage. Simultaneously, they enhance their energy consumption economics and profitability through scientifically scheduled deployment of conventional energy storage equipment.

3. Microgrid Operator Model

First, define the research scope and core issues. For single-microgrid scenarios, based on a two-layer requester–responder game between operators and users, we delineate the decision-making authority of operators as leaders and the responsive behaviors of users as followers. Second, extend the framework to multi-microgrid scenarios by introducing inter-operator energy trading and global coordination constraints. While retaining the requester–responder game logic within individual microgrids, we incorporate horizontal interaction mechanisms between operators. For the symbols and their units in the article, please refer to Appendix A.

3.1. Single-Micro-Network Operator Model

Suppose a day can be divided into time periods. Microgrid operators treat electricity and heat prices as strategic variables, with corresponding constraints as follows:

In the formula, , , represent the grid electricity purchase price and sale price, as well as the microgrid operator’s electricity sale price during the time period within a day; represents the microgrid operator’s heat sales price during the time period within a day; and represent the upper and lower limits of the thermal price.

Microgrid operators are equipped with micro-gas turbines primarily fueled by natural gas, providing electricity and thermal energy to the user side. The relationship between fuel costs and unit output power during the time period of the day can be expressed as:

In the formula, represents the electrical power output of the micro-gas turbine during the time period within a day; represents the unit price of natural gas; represents the lower heating value of natural gas; represents the power output of the micro-combustion unit.

The relationship between electrical and thermal output of a micro-gas turbine during the time interval can be expressed as:

In the formula, represents the thermal power output of the gas turbine during the time interval; represents the heat dissipation loss rate; represents the heating coefficient.

Considering the supply–demand balance of thermal power, we have:

In the formula, represents the thermal power purchased by the user aggregator from the microgrid operator during the time period within a day.

The daily revenue of a microgrid operator can be expressed as:

In the formula, , and represent the revenue generated by the microgrid operator from power transactions with the grid, power transactions with the user side, and heat supply to the user side within a single day; represents the daily thermal energy cost for microgrid operators. The above items can be further expressed as:

In the formula, represents the net electricity load for the user aggregator during the time period within a day.

3.2. Multi-Micro-Network Operator Model

The above model can serve as an individual model for a microgrid operator. In a scenario with multiple microgrids, there exist microgrid operators, forming a set , each microgrid operator possesses equipment configuration and decision-making authority for their individual microgrid. Additionally, energy exchange and strategy coordination among microgrids must be considered to identify optimal solutions in multi-microgrid scenarios.

Building upon the constraints within individual microgrids, new inter-microgrid interaction constraints are introduced: first, energy transmission constraints, which account for the capacity limitations of transmission lines between microgrids. Assume that the power exchange between microgrid and microgrid during the time interval is , meeting the following requirements:

In the formula, represents the maximum transmission power of the line, positive and negative values represent electricity sold to and from microgrid by microgrid , respectively; second, the regional energy balance constraint requires that the total electricity supply during the time period must satisfy the total electricity demand across the entire multi-microgrid region, namely,

In the formula, represents microgrid gas turbine power generation capacity; , represent the power flow between microgrid and the utility grid for electricity purchase and sale; , represent microgrid users’ aggregated energy storage charging and discharging power

The revenue function for each microgrid operator now includes an additional term for inter-microgrid energy transaction revenue, namely:

In the formula, , represent the electricity sales price from microgrid to microgrid , and the electricity purchase price from microgrid to microgrid .

4. Energy Storage Service Provider Model

Assuming a community multi-energy microgrid houses an Ordinary Energy Storage Service Provider (OESP), which independently invests in and centrally deploys energy storage devices. This provider offers only one-way storage and discharge services for a fee to user aggregators; it does not support energy complementarity between different users nor establish a shared pool mechanism. User aggregators pay fees hourly based on their net load profiles, using actual charge/discharge volumes as the settlement basis. Fees are calculated at the service provider’s published unit energy service rate (RMB·kWh−1). Let the scheduling cycle be periods, with as the step size. For any period, .

Service providers need only ensure energy conservation within their own equipment, without the need to balance the charging and discharging electricity of multiple users:

In the formula, , represent the charging power and discharging power (kW) requested by the user aggregator from the service provider during the time period; , represent the charging and discharging power; , represent the energy stored during periods 0 and (kWh).

The physical limits of energy storage equipment are set and publicly announced by the service provider:

In the formula, , represent the minimum and maximum values permitted for the energy storage system capacity; , represent the maximum charging power and maximum discharging power requested by the user aggregator from the service provider.

To ensure long-term stable operation of energy storage systems, the total daily charge and discharge must be balanced to prevent continuous capacity degradation, namely,

The energy storage service fee payable by the user aggregator within a single day shall be calculated based on the sum of the actual charge and discharge volumes:

In the formula, represents the fee payable to the energy storage service provider for charging power or unit discharge power during the time period within a day.

In the formula, , represent the internal unit cost of charging and discharging (RMB/kWh) for the service provider.

Thus, the daily revenue for energy storage service providers is

5. User Aggregator Model

User-side loads are primarily composed of electrical and thermal loads. This paper assumes that users exclusively purchase electricity from microgrid operators while selling electricity uniformly to the grid, establishing a transaction model characterized by one-way electricity procurement and centralized electricity sales.

Therefore, the electricity load of the user aggregator during the time interval of the day can be expressed as:

In the formula, , , and represent the total electricity load, rigid load, flexible load, and additional electricity consumption from electric heating for the user aggregator within a single day. Rigid load lacks flexibility for adjustment, power supply must be provided during fixed time periods, determined based on historical load data and user energy consumption patterns, representing known time series parameters. Flexible load transfers power supply period. Additional electrical load from electric heating refers to the electrical energy consumed by users to generate heat through electric heating equipment, which is directly linked to the output of electric heating.

In heating scenarios, under traditional operational models, users’ thermal energy supply channels are singular, relying entirely on thermal energy services provided by microgrid operators. However, with the maturation and widespread adoption of electric heating home appliance technology, most users can now utilize electric heating equipment to directly convert electrical energy into thermal energy that meets their own needs. Based on this, users can formulate more economical energy consumption strategies by leveraging fluctuations in grid electricity prices. The thermal load demand and corresponding constraints for a user aggregator within a single operational cycle can be expressed as:

In the formula, represents the thermal power supplied by user-side electric heating equipment during the time interval within a day for the user aggregator; , represent the maximum thermal load that the user aggregator actually reduced versus the maximum allowable reduction during the time period within a single day; represents the coefficient indicating whether the user selects the microgrid operator as the heating provider during the time period within a day. A value of 0 indicates the user utilizes electric heating equipment for heating, while a value of 1 indicates the user purchases electricity from the microgrid operator. The value is determined by economic comparison. When the equivalent cost of electric heating is lower than the microgrid’s heat sales price , electric heating is selected; otherwise, heat is purchased from the microgrid, namely:

To balance user energy comfort with grid/microgrid operational stability, establish multi-dimensional demand response constraints and define load adjustment boundaries:

Time-Slot adjustment ratio constraint: The flexible load adjustment for the time slot shall not exceed times the total electrical load to prevent excessive load fluctuations within a single time slot, namely:

The total daily flexible load adjustment shall not exceed times the total daily electricity load, to prevent excessive adjustments from impacting user life, namely:

The total electricity consumption of flexible non-peak loads remains unchanged throughout the day, with only the distribution of usage periods adjusted to ensure users’ core energy needs are met, namely:

Heat load reduction must be based on user comfort. Let the maximum allowable reduction in heat load be , namely:

Capacity limitations for electric heating output equipment: Set the maximum electric heating output to . The electric heating output and additional electrical load must satisfy the efficiency relationship to ensure energy conservation, namely:

In the formula, represents the overall efficiency of the user’s electric heating system; represents the user-side electric heating output during the time period within a day; represents the maximum allowable thermal output during the user aggregator’s electric heating process.

Considering the total electrical load, PV output, and conventional energy storage charging/discharging, the net electrical load for the user aggregator during the time period is:

In the formula, represents the predicted output of the user-side photovoltaic system; represents the net charging and discharging power of energy storage (positive values represent net charging, consuming electrical energy; negative values represent net discharging, supplying electrical energy); represents purchasing electricity from the microgrid operator, with the purchase cost calculated based on the microgrid electricity sales price ; represents electricity sold to the grid, with revenue calculated based on the grid’s purchase price .

The revenue objective of a user aggregator is to maximize electricity utility or minimize energy costs, requiring comprehensive consideration of electricity utility, energy transaction costs, energy storage operation and maintenance costs, and thermal load reduction penalties. The specific expression is:

In the formula, the electricity utility function is modeled as a quadratic function to describe the utility derived from user electricity consumption, reflecting the principle of diminishing marginal utility. It is related to the adjusted total electricity load, namely:

In the formula, a < 0, b > 0, and c are constants. The parameters are determined through user energy preference surveys and historical data fitting.

Electricity transaction cost represents the cost incurred by users when purchasing electricity from the microgrid operator, calculated solely on the net electricity purchase portion, namely:

Thermal transaction cost represents the cost incurred by users when purchasing heat from the microgrid operator. This cost arises only when users choose to purchase heat from the microgrid, namely:

Energy storage operation and maintenance costs represents the costs incurred by users for operating energy storage systems, including charging/discharging energy loss costs and equipment maintenance costs. These costs are calculated based on the total charging/discharging power, namely:

In the formula, , represent the unit charge/discharge loss cost coefficients, and represents the unit maintenance cost coefficient.

Heat load reduction penalty represents the penalty cost incurred due to reduced user comfort resulting from heat load reduction. represents the comfort penalty coefficient, where the penalty intensity increases quadratically with the reduction amount, reflecting the increasing marginal loss of comfort.

Revenue from selling electricity to the grid represents the revenue generated when users sell surplus electricity to the grid, occurring only when the net electricity load is negative, namely:

6. Stackelberg Game-Based Energy Storage Bidding Optimization Model

6.1. Game Theory Analysis

As the dominant party in energy transactions, microgrid operators hold pricing decision-making authority. They must set electricity sales prices and heat sales prices for all 24 time slots of the day based on the next day’s grid time-of-use electricity prices and their own gas turbine operating costs. Their core objective is to maximize daily profits by balancing revenues from grid transactions, revenues from electricity and heat sales to users, and gas turbine fuel costs through rational pricing. Pricing strategies must satisfy fundamental constraints: electricity prices must fall between the grid purchase price and grid sale price to ensure customers prefer microgrid electricity over grid supply; heat prices must remain within a reasonable fluctuation range to prevent excessive costs driving customers to switch to electric heating or insufficient margins causing operational losses.

As energy consumption responders, user aggregators lack pricing authority and must adjust their energy usage strategies after microgrid operators announce pricing. This adjustment integrates the operational characteristics of conventional energy storage, photovoltaic output, and electric heating equipment parameters. Specific measures include: shifting flexible electrical loads to off-peak periods, reducing thermal load proportions, and managing conventional energy storage charging/discharging power. The core objective is to optimize strategies for lowering energy costs, enhancing electricity utilization efficiency, and maximizing daily revenue.

The strategic interaction process is as follows: First, the microgrid operator publishes time-of-use electricity and heat prices. Next, the user aggregator adjusts energy consumption and conventional energy storage scheduling strategies based on pricing, calculates the optimal electricity and heat purchase quantities, and feeds this back to the microgrid. Finally, the microgrid re-evaluates pricing rationality based on the feedback. If profits do not reach the optimal level, pricing is adjusted. This process repeats until both parties’ strategies stabilize, forming a Stackelberg equilibrium.

6.2. Game Model Construction

Participants Set : composed of microgrid operators (leaders) and user aggregators (followers).

Leader Strategy Set : composed of electricity and heat sales prices for each time period, it must satisfy the pricing constraints in the original model, namely:

Follower strategy set : composed of flexible electrical load adjustment , thermal load reduction , and energy storage charging/discharging power , , it must satisfy three types of constraints: demand response constraints, energy storage operation constraints, and electric heating constraints.

Leader payoff function : formula same as (6).

Follower payoff function : formula same as (34).

Thus, the Stackelberg game model can be represented as .

Remark 1

(Existence and Uniqueness of Equilibrium Solutions [25]). 1. Proof of Equilibrium Solution Existence: The boundaries of strategy set and are finite values and include boundary values, making them compact sets. At least one set of strategies satisfies all constraints, ensuring the sets are non-empty. Any linear combination of two strategy sets still satisfies the constraints, making the sets convex. The income function has continuity, and the follower income is quasi convex. Therefore, an equilibrium solution exists. 2. Proof of Equilibrium Solution Uniqueness: The follower’s payoff function is strictly concave with respect to its own strategy. Since the maximum point of a strictly concave function is unique, the follower’s optimal response is unique. The leader’s payoff function is strictly concave, and its maximum point is unique, meaning the leader’s optimal strategy is unique. Therefore, the equilibrium solution is unique.

6.3. Model Solving Method

The core of this Stackelberg game model is a two-stage problem: upper-layer microgrid operators’ pricing optimization and lower-layer user aggregators’ commercial energy and storage strategy optimization. Both parties’ objective functions are convex, with constraints consisting of linear inequalities/equalities, applicable to scenarios satisfying the KKT condition. User aggregator optimization problem: the objective function is strictly concave with linear constraints, allowing direct solution of the optimal strategy via the KKT condition. Upper-Level Microgrid Operator Optimization Problem: Substitute the user’s KKT optimal solution into the microgrid revenue function, transforming it into a single-level convex optimization problem. Solve for the optimal pricing again using the KKT condition. The specific layered computation process is as follows:

(1) Initialization of user aggregator parameters, energy storage parameters, and microgrid operator parameters

(2) Incorporate into the lower-level KKT solution, construct the Lagrange function, and introduce Lagrange multipliers. Introduce multipliers for adjusting upper and lower limits of flexible electrical loads. Introduce multipliers for upper and lower limits of conventional energy storage capacity and charge/discharge power. Introduce multipliers for upper and lower limits of electric heating output and thermal load reduction. Introduce multipliers for equations ensuring conservation of total flexible electrical load and changes in conventional energy storage capacity. Combine constraints including zero gradient, feasibility, and complementary slackness to derive the optimal user strategy, specifying flexible electricity load, energy storage charge/discharge power, and thermal load reduction for each time period.

(3) Substitute into the upper-layer KKT solution, construct the Lagrange function, introduce Lagrange multipliers, and obtain the new pricing by finding the partial derivatives and setting them to zero to achieve the equilibrium between pricing and user energy demand.

(4) Calculate the change in microgrid pricing and mutual benefits between consecutive iterations. If both changes are less than the convergence error threshold of 0.01, terminate iteration. Otherwise, repeat the above steps with the new pricing until convergence is achieved.

7. Case Study Analysis

The practical case study described herein involves a residential community comprising five apartment buildings. A day can be divided into 24 periods, the daily rental fee for the energy storage service provider is 0.33 ¥/kWh. The upper and lower limits of thermal load are set at 0.15 kW/¥ and 0.6 kW/¥, respectively. Other parameters are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Remaining Model Parameters.

To further validate the model’s effectiveness, the case study scenarios are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Corresponding Descriptions for Four Scenarios.

Applying the proposed model to the aforementioned scenarios and implementing it through MATLAB programming, the optimization results for stakeholder benefits across the four scenarios are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Revenue Optimization Values for Microgrid Operators, User Aggregators, and Energy Storage Operators.

Based on the comparative analysis of the data in Table 3, the following conclusions can be drawn: compared to Scenario 1, where microgrid operators and users engage solely in direct electricity and heat transactions, the introduction of electric heating equipment (Scenario 2) and energy storage mechanisms (Scenario 3, respectively, achieves a significant increase in revenue for user aggregators. Simultaneously, these additions produce a certain reduction in revenue for microgrid operators.

Specifically, in Scenario 2, the user aggregator’s revenue increases by ¥205.26 compared to Scenario 1, while the microgrid operator’s revenue decreases by ¥25.26. This outcome stems from the synergistic effect between the electrically heated appliances deployed on the user side and the thermal load demand response strategy. This synergy effectively enhances the flexibility of regulating thermal energy demand on the user side, reducing the rigid dependence on the microgrid operator’s thermal supply. In Scenario 3, the user aggregator’s revenue increases by ¥709.67 compared to Scenario 1, while the microgrid operator’s revenue decreases by ¥43.67. Concurrently, the energy storage operator achieves a profit of ¥643.98. The core reason lies in energy storage services providing users with tools for flexible electrical load adjustment. Users can optimize electricity consumption timing through storage charging and discharging, significantly reducing their dependence on the microgrid operator’s electricity supply and demand, thereby optimizing their own revenue structure. Scenario 4 demonstrates the most pronounced optimization effect: user aggregator revenue increases by ¥977.95 compared to Scenario 1, microgrid operator revenue decreases by ¥53.28, and energy storage operators achieve a profit of ¥654.34. This is due to the synergistic effect between electric heating equipment and shared energy storage, which maximizes the bidirectional adjustment potential of both electricity and heat loads on the user side. This achieves further reductions in energy costs and optimal revenue enhancement.

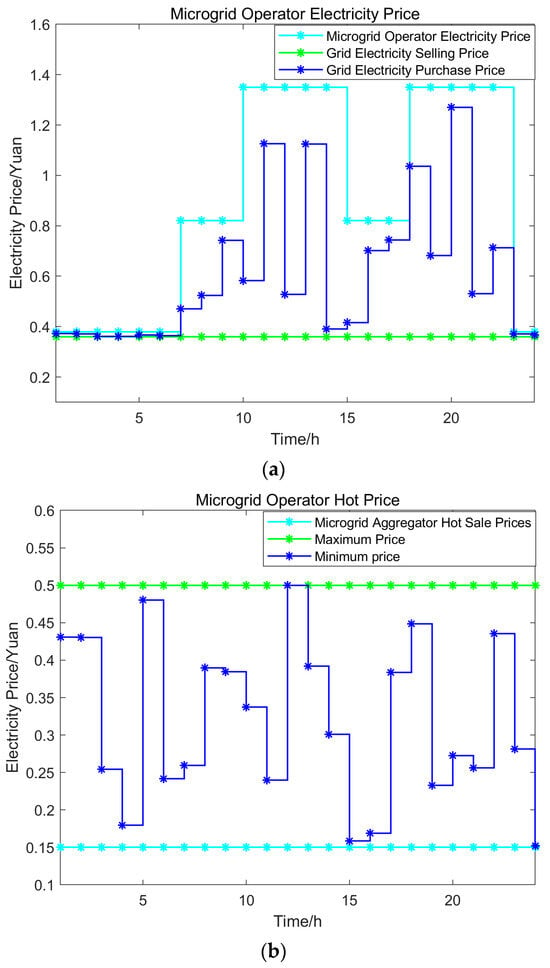

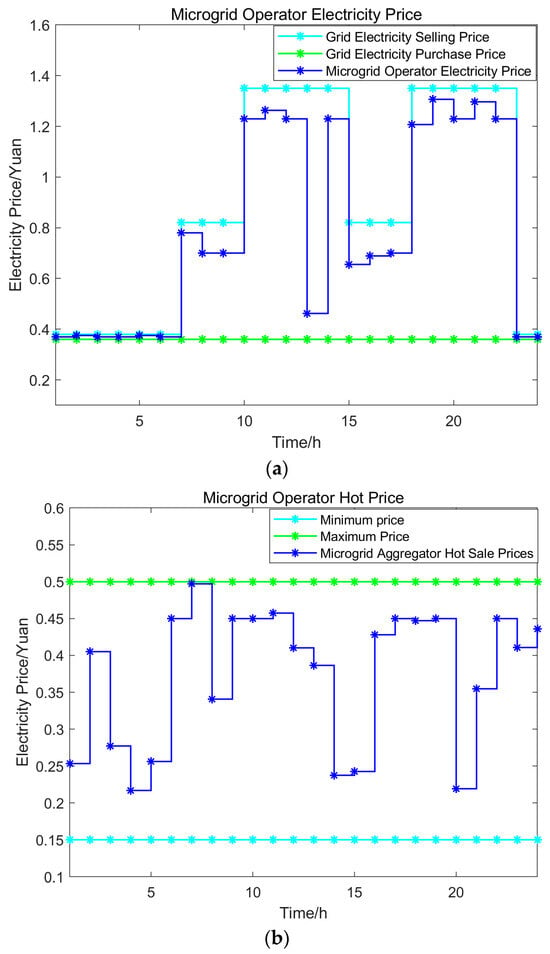

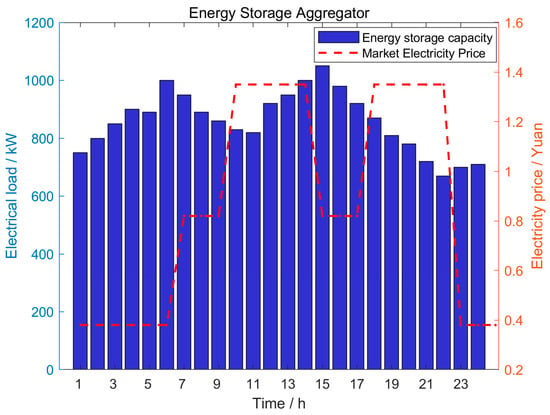

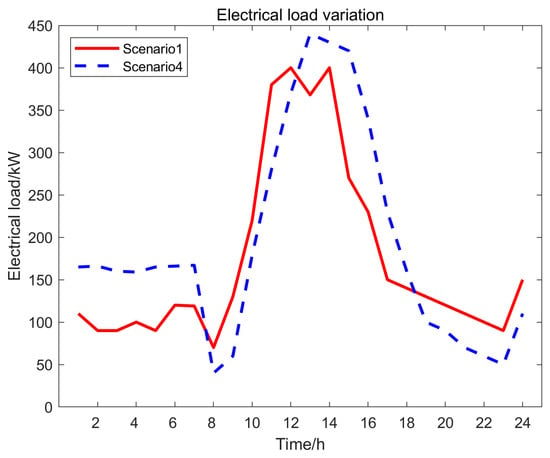

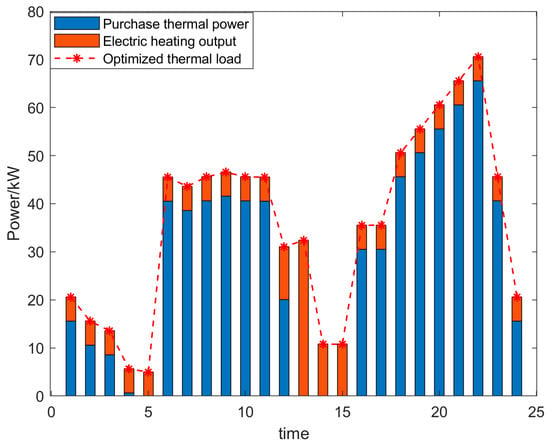

Due to space constraints, this paper focuses on analyzing Scenarios 1 and 4. The optimized electricity and heat sales prices for microgrid operators within a single day under Scenarios 1 and 4 are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively. The changes in energy storage system capacity, shifts in user-side electrical load, and the output curves of user aggregator electric heating equipment under Scenarios 1 and 4 are presented in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 2.

Microgrid Operator Electricity Sales Price (a) and Heat Sales Price (b) in Scenario 1.

Figure 3.

Microgrid Operator Electricity Sales Price (a) and Heat Sales Price (b) in Scenario 4.

Figure 4.

Daily Energy Storage Power Curve of the Energy Storage System under Scenario 4.

Figure 5.

Output Curves of Commercial Electric Heating Equipment for User Aggregators in Scenarios 1 and 4.

Figure 6.

Output Curve of Commercial Electric Heating Equipment for User Aggregators in Scenario 4.

An in-depth analysis combining Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 reveals the following: Figure 2 and Figure 3 clearly illustrate the disparity between the electricity and heat sales prices offered by microgrid operators under two distinct scenarios. This divergence arises because Scenario 4 incorporates electric heating equipment and energy storage services, which actively participate in regulating electricity and heat loads on the consumer side. This active involvement significantly impacts the strategic dynamics between the parties, altering the original outcome of their interactions.

Figure 4 details the capacity variation curve of the energy storage system throughout a day. The curve reveals that storage capacity consistently increases during the periods from 0:00 to 6:00, 11:00 to 15:00, and 23:00 to 24:00. This pattern aligns closely with the increased electricity load observed during these specific timeframes under Scenario 4. Specifically, during these periods, users choose to charge the energy storage system, storing electricity for later use. Conversely, from 7:00 to 10:00, and 16:00 to 22:00, the system’s capacity shows a decline, corresponding to the reduction in user electricity demand during this time. At this point, the energy storage system releases stored electricity to meet user consumption needs. This dynamic adjustment of energy storage capacity in response to user electricity load fluctuations fully demonstrates the critical role energy storage systems play in regulating user-side electricity demand.

Figure 5 highlights changes in user-side electricity load under two scenarios. Comparing Scenario 1 and Scenario 4 reveals that users exhibit similar electricity consumption patterns in both scenarios: they tend to increase electricity usage during the periods from 0:00 to 7:00, from 8:00 to 12:00 and from 23:00 to 24:00, while reducing consumption during the extended period from 13:00 to 22:00. This shift in electricity consumption is not coincidental but closely aligns with the optimized electricity purchase prices for microgrid operators shown in Figure 2a. During periods of lower electricity purchase prices, users increase their electricity consumption and purchase more power to reduce costs. Conversely, during periods of higher purchase prices, users reduce consumption to save expenses. This rational adjustment of electricity usage in response to price fluctuations further validates the accuracy and reliability of relevant research findings, demonstrating that users can make rational electricity consumption decisions based on price signals.

Figure 6 illustrates how users obtain thermal energy during different time periods. It is evident that during specific intervals, 0:00–7:00 and 23:00–24:00, users opt to use electric heating equipment for thermal energy. This occurs because the cost of generating heat via electric heating equipment is relatively low during these periods, satisfying users’ thermal needs while reducing heating expenses. During other hours, users opt to purchase heat from the microgrid operator. This flexible decision-making regarding heating methods across different time slots results from users’ comprehensive analysis and rational planning based on the microgrid operator’s heat and electricity pricing. By comparing the costs of different heating methods, users select the most economical option to maximize their own benefits. This behavior, where users autonomously adjust their heating methods based on price information, fully reflects the rational pursuit of economic benefit maximization under market mechanisms.

8. Conclusions

The decision-making model dominated by microgrid operators significantly compresses the profit margin for the user side. This paper focuses on community-based integrated energy microgrids and energy storage systems, proposing electricity-to-heat conversion technologies and energy storage optimization mechanisms oriented toward the user side. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Existing research primarily focuses on electricity–heat coupling at the microgrid operator level. This paper’s model further incorporates user-side electric heating equipment, achieving bidirectional electricity–heat coordination between generation and load. This comprehensive approach better aligns with the practical operational requirements of future integrated energy microgrids.

(2) Against the backdrop of rapidly advancing energy storage technologies, this model significantly increases user benefits by enhancing flexibility in electricity and heat regulation. It provides actionable decision support for energy storage participants, enabling mutual gains for user aggregators and storage operators. Quantitative analysis of key factors, including electric heating, electric heating demand response, and energy storage services, delivers critical decision-making insights for the user side.

(3) As household appliances and energy storage services become more prevalent, the coupling relationship between electricity and heat on the user side grows increasingly complex. This model effectively balances the conflicting interests between microgrid operators and user aggregators, providing quantitative references for operators to formulate dynamic electricity and heat pricing.

(4) A distributed solution framework integrating game theory algorithms with KKT conditions has been designed. Within this framework, game theory algorithms simulate strategic interactions among multiple participants, while KKT conditions ensure that each participant’s locally optimal strategy aligns with the overall model objective. This approach enables efficient model solution.

Limitations of this study: The current framework is based on the microgrid market rules of pilot provinces in China, and the requester–responder game hierarchy may not be applicable to fully liberalized electricity markets. Parameters such as user energy elasticity and renewable energy prediction accuracy significantly affect the equilibrium results, and the cost of data acquisition may limit practical applications. The model does not explicitly consider the internal line flow and cascading constraints of the microgrid, which may affect the feasibility of the strategy in high-density access scenarios. Assuming a single type of energy storage technology, without involving the optimization configuration and collaborative control of hybrid energy storage systems.

Global application potential: The requester–responder game structure can adapt to different organizational models such as Energy Communities in Europe and Virtual Power Plants in the United States, requiring only adjustments to the leader follower role definition. The pricing constraint module can be coupled with multiple policy tools such as country on grid electricity prices, capacity markets, and demand response subsidies. The KKT solution method has low requirements for communication infrastructure and is suitable for microgrid deployment in weak areas of home appliance networks in developing countries. The wind and solar power output model can be replaced by regional resource endowments such as geothermal and tidal energy, supporting special scenarios such as tropical and polar regions.

It should be noted that this paper assumes a fixed energy storage service fee. As a preliminary exploration of the tripartite collaborative optimization framework, fixed prices can clearly reveal the coupling mechanism between microgrid pricing power, user response behavior, and energy storage configuration, reduce model non convexity, and ensure the existence and solvability of equilibrium solutions in the requester–responder game; In this model, the energy storage service provider is embedded in the main subordinate game structure, and its revenue has been indirectly linked to the microgrid operator through service capacity leasing. Fixed costs can be regarded as an equivalent representation of long-term contract prices. Future research could explore dynamic pricing strategies when shared energy storage providers act as game participants. Shared energy storage providers could also actively engage in the game as players, with the formulation of their daily service fees emerging as a noteworthy topic for future investigation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.L., S.L., S.W. and K.W.; Software, Y.L.; Validation, Y.L.; Formal analysis, Y.L. and K.W.; Investigation, H.S. and S.W.; Resources, S.W.; Data curation, Z.H. and H.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, S.L. and K.W.; Visualization, S.L. and K.W.; Supervision, S.W. and K.W.; Project administration, Z.H., H.S. and S.L.; Funding acquisition, Z.H. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Smart Grid-National Science and Technology Major Project (2030) (2025ZD0805400). Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China (52272225002P).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Z.H. and H.S. were employed by State Grid Gansu Electric Power Company. Author S.L. was employed by NARI Technology Co., Ltd. Author S.W. was employed by the China Electric Power Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Gansu Electric Power Company. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADNs | Active distribution networks |

| CCHP | Combined Cooling, Heating and Power |

| CHP | Combined heat and power |

| EHIESS | Electricity-heat integrated energy storage supplier |

| IDR | Integrated Demand Response |

| KKT | Karush-Kuhn-Tucker |

| MGO | Microgrid Operator |

| MGCO | Micro-grid coalition |

| OESP | Ordinary Energy Storage Service Provider |

| SES | Shared energy storage |

| SHES | Shared hybrid energy storage |

Appendix A

Table A1.

A summary table of symbols and units used in formula descriptions.

Table A1.

A summary table of symbols and units used in formula descriptions.

| Symbol | Unit |

|---|---|

| ¥ | |

| ¥kW | |

| kWh |

References

- Li, Y.H.; Wei, M.S.; Tian, R. Performance analysis of an energy system with multiple combined cooling, heating and power systems considering hybrid shared energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 233, 121166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.Y.; Zhao, C.Z.; Wang, F. Optimal scheduling of integrated energy system considering power to gas and carbon capture system. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2025, 47, 9944–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.S.; Ran, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Guo, X. Integrated management of electric vehicle sharing system operations and Internet of Vehicles energy scheduling. Energy 2024, 309, 132498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Digital Technology Implementation in Battery-Management Systems for Sustainable Energy Storage: Review, Challenges, and Recommendations. Electronics 2022, 11, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.Q.; Liu, Z.F. Multistage Dynamic Interaction Strategy-Driven Collaborative Optimization of Regional Integrated Energy System with Electric Vehicle Cluster. J. Energy Eng. 2025, 151, 04025079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Tushar, W.; Yuen, C. Energy Management for Joint Operation of CHP and PV Prosumers Inside a Grid-Connected Microgrid: A Game Theoretic Approach. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 12, pp. 1930–1942. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, J.; Huang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hussain, F.; Ahmed, S.A.; Manzoor, K. Optimization of social welfare in P2P community microgrid with efficient decentralized energy management and communication-efficient power trading. J. Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.M.; Tang, H.L.; Wu, J.K.; Li, C.J.; Wang, Y.A. A robust optimization framework for energy management of CCHP users with integrated demand response in electricity market. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 141, 108181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Guo, Q.S.; Zeng, W. Optimal dispatch of community integrated energy system based on Stackelberg game and integrated demand response under carbon trading mechanism. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Energy Sharing Management for Microgrids With PV Prosumers: A Stackelberg Game Approach. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 1088–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.H.; Niu, C.E.; Zhang, Y.H.; Xie, A.B.; Lu, R.; Yu, S.J.; Qiao, S.; Lin, Z. A Multi-Time Scale Hierarchical Coordinated Optimization Operation Strategy for Distribution Networks with Aggregated Distributed Energy Storage. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.; Schanz, H. The sharing economy: A comprehensive business model framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, J.C.; Wen, Y.J.; Yu, X. Economic Optimal Coordinated Dispatch of Power for Community Users Considering Shared Energy Storage and Demand Response under Blockchain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Wang, H.L.; Li, B.; Li, C.J.; Tan, Z.K. Capacity model and optimal scheduling strategy of multi-microgrid based on shared energy storage. Energy 2024, 306, 132472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Li, Y.W.; Du, E.S.; Fan, C.; Wu, Z.L.; Yao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N. A review and outlook on cloud energy storage: An aggregated and shared utilizing method of energy storage system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Zhao, H.R.; Xie, G.L.; Lin, K.Y.; Hong, J.H. Research on Industrial and Commercial User-Side Energy Storage Planning Considering Uncertainty and Multi-Market Joint Operation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.A.; Zheng, W.J.; Yu, Z.W.; Xu, Z.Q.; Jiang, H.L.; Zeng, M.D. Optimizing Grid-Connected Multi-Microgrid Systems With Shared Energy Storage for Enhanced Local Energy Consumption. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 13663–13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Rehman, T.; Hussain, A.; Kim, H.M. Day-ahead operation of a multi-energy microgrid community with shared hybrid energy storage and EV integration. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.X.; Qian, Q.F.; Xu, P.P.; Wang, J.J. Optimal dispatch of integrated energy systems incorporating diversified energy storage under a long- and short-term synergistic strategy. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 5839–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Zeng, S.Q.; Li, Y.J. Optimal operation of regional integrated energy system considering demand response. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 191, 116860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, F.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Ren, A.; Zhang, J. Scheduling optimization mode of multi-microgrid considering demand response. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Beijing, China, 26–28 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.Q.; Yang, X.L.; Zhang, Z.N.; Zheng, S.Q.; Cui, B.W. Multi-Objective Optimal Source-Load Interaction Scheduling of Combined Heat and Power Microgrid Considering Stable Supply and Demand. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 901529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Dou, Z.H.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.M.; Zhao, J.W.; Yin, W.L. Optimal Configuration of Electricity-Heat Integrated Energy Storage Supplier and Multi-Microgrid System Scheduling Strategy Considering Demand Response. Energies 2024, 17, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huang, D.Y.; Hu, Q.; Jia, H.J.; Liu, B.; Lei, Y. Electricity-Heat-Based Integrated Demand Response Considering Double Auction Energy Market with Multi-Energy Storage for Interconnected Areas. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Clempner, J.B. A tri-level approach for computing Stackelberg Markov game equilibrium: Computational analysis. J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 68, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.