Abstract

Energy management systems incorporating battery energy storage systems (BESSs) are an effective way to deal with peak power demand in power systems, contributing to sustainability and energy management. In these systems, BESS interface converters encounter many challenges, such as achieving high efficiency, reliability, and scalability. A partial power processing (PPP) converter is one of the promising methods for reducing system energy losses and increasing reliability, thereby optimizing energy conversion between the BESS and the dc bus. However, implementing PPP in a BESS requires a high input-to-output voltage ratio and bidirectional operation over the battery voltage variation, which increases the design complexity. This paper proposes a half-bridge push–pull converter and provides guidance on its design for that purpose. A design procedure considering system efficiency and operating principles is comprehensively investigated and is applied to a PPP converter operating with a 15 kW BESS. The simulation and experimental results show that the efficiency of the system reaches up to 99% with a converter efficiency of 88%, which shows that the proposed structure achieves bidirectional operation and high efficiency based on the partial power processing concept.

1. Introduction

With the expansion of the electric vehicle (EV) market, the rapid growth in EV energy demand is expected to increase the required capacity of charging infrastructure [1,2]. The BESS has emerged as a pivotal technology for supporting grid stability, enhancing energy reliability, and facilitating the transition to a more sustainable energy future [3,4,5]. As a representative large-scale energy storage technology, pumped-hydro storage typically exhibits a round-trip efficiency of 75–85%, whereas a BESS can achieve 90–98% [5]. By enabling the storage and dispatch of energy during periods of excess production, a BESS provides critical services, such as load leveling, frequency regulation, and power backup, ensuring that energy availability aligns with demand. As the scale and complexity of these systems continue to grow, there is an increasing need for high-efficiency power conversion solutions capable of handling large power ratings and meeting the stringent requirements of modern energy storage systems [6,7].

To improve the performance and efficiency of BESSs, extensive research has been conducted on battery pack state estimation [8,9,10,11,12] and power converter control strategies [13,14,15,16,17,18]. The power converter is a central component in a BESS, responsible for interfacing battery storage with the grid or load. In particular, the dc-dc converter plays a crucial role in converting the battery voltage to the required level for grid or load supply while maintaining high efficiency to minimize losses and maximize system performance [19,20,21,22]. Given the large power throughput in high-capacity BESS applications, the design of these converters must focus on minimizing conversion losses, reducing component stresses, and ensuring high reliability under dynamic operating conditions.

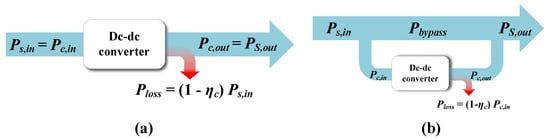

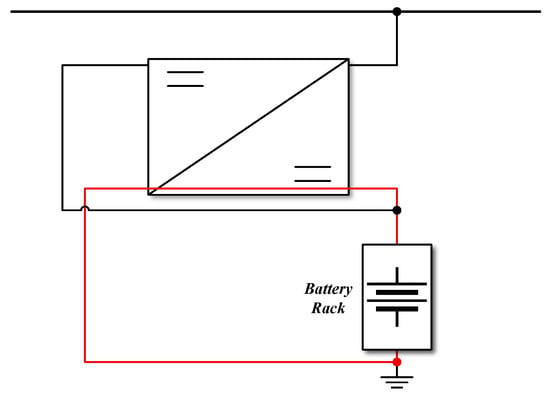

To address these challenges, the concept of partial power processing (PPP), shown in Figure 1, has been introduced to improve the efficiency of energy exchange between the BESS and the dc grid [23,24,25,26,27,28]. In the conventional configuration in Figure 1a, a dc-dc converter processes 100% of the power flow between the BESS and the dc grid, which is referred to as full power processing (FPP). However, the FPP concept faces several challenges: as the BESS power increases, the converter rating increases proportionally, leading to a linear rise in component cost and practical difficulty in selecting suitable components [29]. Furthermore, the dc-dc converter accounts for a significant portion of the total power loss in the BESS. In contrast, in Figure 1b, the converter processes only a small portion of the total power flowing between the BESS and the dc grid; thus, PPP can achieve a reduced converter rating and improved efficiency compared to its FPP counterpart. Therefore, PPP can be a viable solution for downsizing power converters and improving overall system efficiency.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of power processing: (a) full power processing, (b) partial power processing.

Recent PPP studies have mainly focused on applications with operating voltage variations, such as photovoltaic generation [30,31], wind power [32], and BESSs. As mentioned earlier, PPP can enhance overall efficiency by reducing the power processed through the converter, thereby lowering conversion losses and thermal burden in high-power interfaces. However, achieving a lower power processing ratio may require a higher input–output voltage ratio than in FPP. Especially in BESS applications, a systematic design procedure is essential to ensure stable bidirectional operation across wide operating conditions.

The BESS is regarded as a key target for PPP because its terminal voltage varies significantly with the charge and discharge states, while high efficiency and power density are required for high-power, large-capacity operation. Although prior studies have demonstrated the feasibility of PPP-based interfaces and reported high efficiencies and reduced processed-power fractions, systematic design procedures that guarantee stable bidirectional operation over the full battery voltage range remain limited.

In PPP, the converter handles only a portion of the overall voltage conversion, which yields an effective input–output voltage ratio that differs from that of FPP under identical operating conditions. This effective voltage ratio can deviate significantly from that of FPP, as the fraction of system power processed by the converter decreases. Based on that property, various dc-dc converter topologies have been investigated and applied for various battery applications. Granello et al. implemented a flyback-based battery charger operating in PPP at 5.5 kW, achieving over 99% system efficiency while the converter processed only 21% of the total system power. In addition, a design procedure for the proposed PPP topology was presented [33]. Iyer et al. applied a dual active bridge (DAB) converter to an EV fast-charging station using PPP, in which the converter processed 27% of the system power, and its design procedure was also proposed [34]. Cao et al. developed a 15 kW rated CLLC-based PPP battery charger that reduces the processed-power fraction to near zero at nominal voltage and keeps it below 20% across most of the operating range, achieving a peak efficiency of 98.8% through a systematic decoupled design procedure [35]. Abdel-Rahim et al. proposed a current-fed dual-inductor push–pull PPP architecture, in which 25% of the system power is processed by the converter; however, the design methodology for component and experimental hardware validation could be further investigated [36].

Among the various bidirectional PPP converter candidates, the DAB is one of the most widely adopted topologies due to its symmetric circuit structure and simple operating principle [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], together with various control methods [45,46]. However, a DAB employs a relatively large number of switching devices, which increases its cost and often requires advanced control methods to achieve high performance [47]. Furthermore, as discussed earlier, reducing the fraction of system power processed by the converter can lead to a significantly increased or decreased effective input–output voltage ratio. This imbalance in the voltage ratio results in substantially higher current on one side of the converter compared to the other, thereby increasing conduction losses and degrading the overall converter efficiency and the lifetime of switching components.

To mitigate these drawbacks, the half-bridge push–pull (HBPP) structure is a viable bidirectional PPP candidate. Compared with DAB-based implementations, HBPP can reduce the number of active switches and alleviate device current stress, particularly on the secondary side, which can contribute to improved efficiency in high-power BESS interfaces. These attributes make HBPP a promising topology for PPP-based BESS applications, where efficiency and reliability are of primary importance. Nevertheless, a systematic and practical design methodology for HBPP-based bidirectional PPP converters has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

In this paper, a bidirectional PPP converter design framework is presented for a BESS. The proposed approach targets applications requiring both a high voltage conversion ratio and bidirectional operation over a battery voltage range. To meet these requirements with reduced converter power rating, an HBPP PPP topology is adopted, and its operating principles are systematically analyzed. The present study further completes the validation of the proposed design methodology by implementing and testing a 15 kW hardware prototype under charge and discharge conditions. Then, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- The design requirements and practical constraints for implementing PPP in a parallel BESS (e.g., bidirectional operation, high conversion ratio, and feasible duty ratio) are identified and discussed.

- A bidirectional HBPP PPP converter is analyzed in a mode-by-mode manner, providing design-oriented insights into its steady-state operation.

- A unified design procedure is established to select the duty ratio, transformer turn ratio, and passive/active components over the battery voltage operating range.

- The proposed converter and design methodology are validated through simulations and 15 kW experimental results, including efficiency and loss breakdown analysis.

2. Configuration of PPC-Integrated Battery Energy Storage Systems

2.1. Operation Principle of Partial Power Processing

As discussed in the previous section, the PPP concept indicates that the converter handles only a portion of the total system power. In other words, PPP aims to reduce or eliminate unnecessary power conversion, thereby minimizing losses in the overall power-handling process. The advantages of employing the PPP concept include (1) system efficiency improvement and (2) converter size reduction, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

2.1.1. System Efficiency Improvement

As shown in Figure 1a, the system output power () is equal to the converter output power () in FPP, since all the power is processed by the converter. Thus, the system loss is identical to the converter loss.

where and are the input power of the converter and system, respectively. Therefore, in FPP, the system efficiency () is also equal to the converter efficiency ().

In contrast, in the case of PPP, shown in Figure 1b, the system output power () can be expressed as the sum of the bypassed power () and the power processed by the converter (), as given in (3).

To represent the ratio of the power processed by the converter to the power handled by the system, the power processing ratio () is defined as

Accordingly, can be expressed in terms of the power processing ratio:

and the bypassed power () can be expressed as

Since the converter’s efficiency () is defined as the ratio of its output power to its input power,

from (4) and (7), the converter input power can be derived as

Since the overall system efficiency () is the ratio of the system’s output power () to its input power (), where the input power is the sum of the converter’s input power () and the bypassed power (), the following holds:

By substituting (6) and (8) into (9), the system efficiency () can be derived as a function of the power processing ratio () and the converter efficiency () as follows:

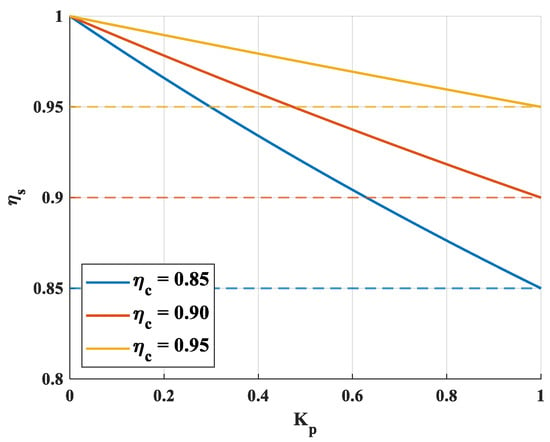

Therefore, from (10), system efficiency () is a function of converter efficiency () and the power processing ratio (). It can be observed that, regardless of how small is, the system efficiency approaches unity as approaches zero. Consequently, in a PPP system, the power processing ratio () can be utilized as an index to evaluate the performance of PPP. Figure 2 shows the effect of variations in and on the system efficiency . When is equal to unity, the converter processes the entire system power, and thus, becomes equal to . However, when becomes less than 1, meaning that the converter processes only a portion of the system power, it can be observed that the system efficiency () becomes higher than the converter efficiency ().

Figure 2.

System efficiency vs. power processing ratio for various converter efficiencies.

2.1.2. Size Reduction

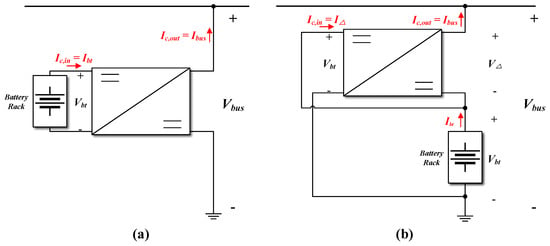

Another significant advantage of employing PPP is the reduction in converter size. This can be understood through the following analysis. Figure 3 illustrates the configurations of the battery interface converters for FPP and PPP, along with their respective current flows during battery discharge mode. The details about PPP configuration will be discussed in the following section.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of battery interface converters: (a) full power processing, (b) partial power processing.

From Figure 3b, applying Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) yields

where is the headroom voltage processed by the PPP converter, and is the dc bus voltage. In Figure 3b, the power processing ratio in discharging mode in (4) can be expressed as

Considering that the battery voltage can vary during operation, also varies according to the variation in the battery voltage. Therefore, in this system comes to have a certain range, from to . Each can be expressed as

and

By applying (11) to (13) and (14), the above expressions can be rewritten as follows. In the case of ,

and for ,

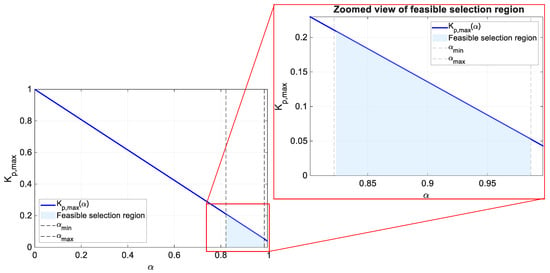

where and represent the maximum battery voltage and minimum battery voltage, respectively. From (16), we can obtain the condition for whether PPP can be satisfied within the allowable battery voltage range. Here, for clarity, we define as the ratio of the maximum battery voltage to the minimum battery voltage, which are defined as

Therefore, the converter power reduction ratio is determined by the battery voltage ratio . A wider battery voltage range (a smaller ) requires a converter designed with a higher maximum power processing ratio . Figure 4 illustrates that when , the converter must be rated for higher power to satisfy a power processing ratio exceeding 0.2. In contrast, when , the required converter power rating is significantly reduced, enabling a very high system efficiency, as remains below 0.05.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of battery voltage ratio and maximum power processing ratio .

2.2. System Configuration for Partial Power Processing

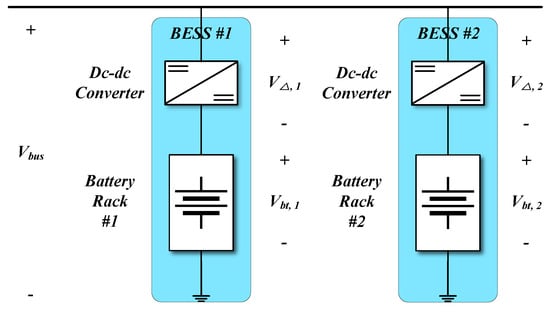

To improve the reliability and operational flexibility of the battery, a parallel BESS architecture has been researched [21,48,49]. However, the voltage difference in each battery, resulting from the state-of-charge (SOC) imbalance, induces unintended circulating currents among the parallel units, which lead to unnecessary lifetime degradation and potential safety issues. To address these challenges, the parallel BESS architecture necessitates the integration of a dedicated dc-dc converter for each BESS unit, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Parallel BESS architecture with dc-dc converter.

The role of PPP in this system is the same as that of a series voltage regulator (SVR): to maintain the voltage of the BESS equal to , regardless of the variations in . In this configuration, the role of the dc-dc converter is to compensate for the voltage difference between the dc bus and the battery rack, thereby ensuring the BESS voltage equals the dc bus voltage.

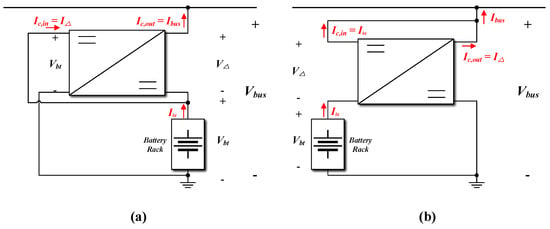

As previously mentioned, to implement partial power processing, it is necessary to share either the voltage or the current. Therefore, two different connection schemes can be considered, as illustrated in Figure 6. In Figure 6a, the converter is connected in parallel with the battery on one side, while its other side is connected in series between the battery and the dc bus. In this paper, according to its connection, this configuration is referred to as Battery Parallel and DC bus Series (BPDS).

Figure 6.

Candidate PPP configurations: (a) Battery Parallel and DC bus Series, (b) DC bus Parallel and Battery Series.

In contrast, Figure 6b shows a configuration where the dc bus is connected in parallel with the converter, with the opposite side maintaining the same series connection as in Figure 6a. For the same reason, this configuration is called DC bus Parallel and Battery Series (DPBS). In both configurations, applying Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL) gives the following equation:

where is the processed current handled by the PPP converter.

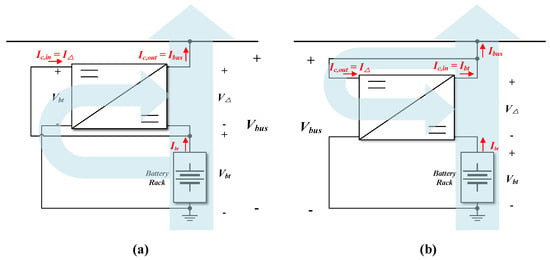

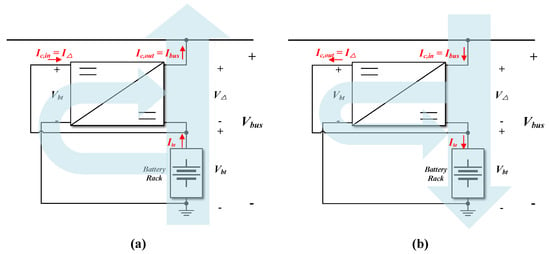

In both cases, the converter is able to maintain and regulate the headroom voltage (). However, the two configurations show differences in the aspect of circulating power. Figure 7 illustrates the power flow of the converter and system during the battery discharging operation [50]. When the system operates in battery discharging mode, as shown in Figure 7a, the converter receives and processes the battery voltage. In this operating mode, the directions of the system power and the converter-processed power are identical. However, the power flow of the discharging operation in Figure 7b clearly demonstrates circulating power. Therefore, the converter draws power from the dc bus, processes it, and delivers it back to the dc bus.

Figure 7.

Power flow analysis in battery discharging mode: (a) Battery Parallel and DC bus Series, (b) DC bus Parallel and Battery Series.

In the discharging mode, for the two operating modes is derived as follows:

Under the same input–output voltage condition, the DPBS configuration yields a higher than the BPDS configuration, as can be seen by comparing (20) and (21). Similarly, in the charging mode, of BPDS is expressed as

In the case of DPBS,

Also, in the charging mode, the DPBS configuration shows higher than BPDS. Therefore, under the given conditions, configuring both the discharging and charging modes as BPDS is the most favorable option. However, due to the inherent constraints of the system interconnection, this is not feasible in practice. Consequently, one operating mode must be configured as BPDS, while the other must be configured as DPBS. Thus, in this paper, the BPDS configuration is selected for the battery discharging mode and DPBS for the charging mode. Figure 8a,b illustrate the power flow directions in the converter and the system during both discharging and charging operations of the selected configuration, respectively.

Figure 8.

Power flow analysis of BPDS configuration: (a) battery discharging mode, (b) battery charging mode.

3. Proposed Converter Topology

3.1. Required Features

To achieve bidirectional power flow with PPP, the converter applied in this system needs to meet several requirements:

- An isolated converter is preferred.According to ref. [27], both isolated (e.g., DAB, flyback) and non-isolated topologies (e.g., buck–boost, SEPIC) can be employed in implementing PPP systems. However, if non-isolated topologies are applied to the configuration in Figure 6a, a short-circuit path is formed between the negative terminal of the converter and the battery, as illustrated in Figure 9. Therefore, to prevent a short circuit in this configuration, galvanic isolation of the converter output stage via a transformer is required. Furthermore, the use of a transformer facilitates achieving a high input–output voltage ratio, which will be discussed in a later section.

Figure 9. Illustration of the potential short-circuit path due to the common ground in non-isolated configurations.

Figure 9. Illustration of the potential short-circuit path due to the common ground in non-isolated configurations.

- A high input–output voltage ratio () is essential.In PPP, the dc-dc converter demands a higher voltage gain than in FPP. As discussed previously, Figure 7a,b illustrate the conceptual block diagrams of a PPP-based BESS in discharging and charging modes. Considering the power flow through the converter, the converter operates in the step-up mode to charge the battery and in the step-down mode to discharge it. In both modes, (11) and the following equation hold:In the discharging mode, the voltage gain of the PPP converter in Figure 7b is expressed as follows:On the other hand, in the FPP shown in Figure 5, the voltage gain is expressed asTherefore, from (27), it can be proven that the dc-dc converter for a PPP-based BESS requires a lower voltage gain than an FPP-based BESS in discharging mode. However, in the charging mode, the voltage gain is expressed as the reciprocal of (27), which exhibits a higher voltage gain compared to FPP. Considering the voltage gain requirements in both operational modes, a transformer is typically employed to achieve a high voltage conversion ratio, even though the PPP configuration is inherently a non-isolated structure.

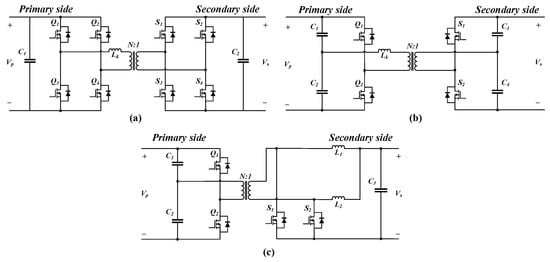

3.2. Topology Selection

Taking into account what was mentioned earlier, the three isolated bidirectional topologies shown in Figure 10 are considered for the PPP implementation. In every topology in Figure 10, the primary side is connected to the battery, and the secondary side is placed between the dc bus and the battery; the primary voltage, , is always much higher than the secondary voltage, . In Table 1, the three topologies are compared in terms of various criteria. Compared to an FBDAB, the other two can reduce the number of switching components by half, thereby decreasing the volume of the converter. Between the remaining two topologies, HBPP can lower the secondary-side conduction loss owing to its reduced RMS current. In the case of an HBDAB, the half-bridge structure inherently imposes higher current stress on the switches compared to a full-bridge DAB of the same rating, making it unsuitable for PPP configurations that require higher current.

Figure 10.

Proposed topology and applications: (a) full-bridge dual active bridge (FBDAB), (b) half-bridge dual active bridge (HBDAB), (c) half-bridge push–pull (HBPP).

Table 1.

Comparison of converter topologies.

In contrast, HBPP benefits from its dual-inductor push–pull structure, which reduces the current stress on the switching components and makes it more suitable for the series-connected section of a PPP configuration.

In addition, HBPP offers the following advantages from a voltage perspective. In conventional push–pull structures of HBPP, high peak voltage is commonly applied to the switching components during switching. However, in the BPDS structure used in this paper in Figure 8, the push–pull terminal is connected in series with the dc bus and the battery, thereby mitigating the voltage stress applied to the switching components. Considering these factors, HBPP is selected as the most suitable topology in terms of switch count and stress.

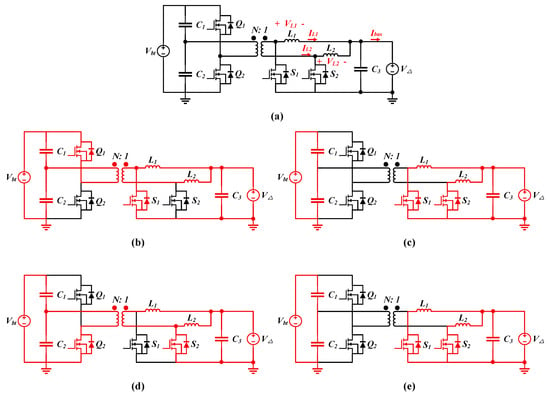

3.3. Operation Analysis

Figure 11 shows a circuit diagram of the proposed topology. As shown in the figure, the half-bridge side is connected to the battery , while the push–pull side is connected between the battery and the dc bus, and the voltage is represented as . On the push–pull side, an interleaved structure employing two inductors is applied to achieve a reduction in the output current ripple. The primary and secondary sides are also referred to as the half-bridge and push–pull sides, respectively.

Figure 11.

Analysis of the operation mode: (a) equivalent circuit, (b) Interval 1 (∼), (c) Interval 2 (∼), (d) Interval 3 (∼), (e) Interval 4 (∼).

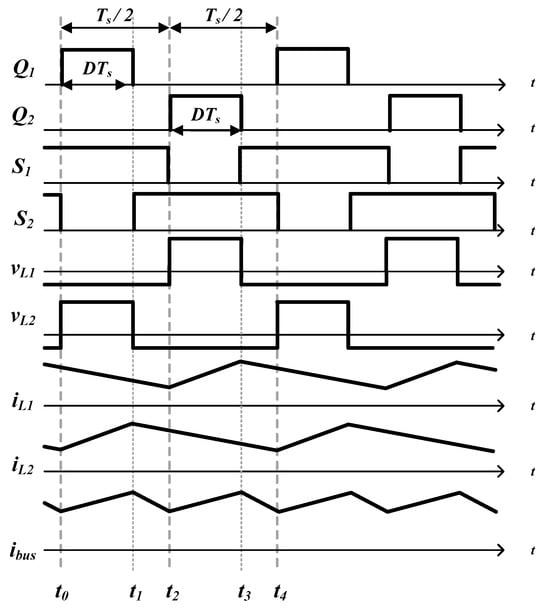

The converter can be operated in either the step-down mode or step-up mode. In the step-up mode, the power flows from the push–pull side to the half-bridge side, whereas in the step-down mode, the power flows from the half-bridge side to the push–pull side. In the following analysis, the reference directions of voltage and current are defined based on the step-down mode operation, following the passive sign convention shown in Figure 11a. The on–off signals of each switch over time, along with the corresponding operational waveforms of the converter, are shown in Figure 12. The detailed operating principles of each mode are described as follows.

Figure 12.

Switching voltage and current waveforms of the HBPP topology in the step-down mode.

- Interval 1 ∼At , is turned on and is turned off while is turned on, as shown in Figure 11b. Therefore, the voltage applied to the primary winding of the transformer isThus, the voltage applied to each inductor can be expressed asIn the step-down mode, is connected to through and releases its stored energy, while is connected to and stores energy from .In the step-up mode, in contrast, stores energy through and releases the energy into .

- Interval 2 ∼At , is turned off to ensure the deadtime for the half-bridge, and is turned on while keeping on, as shown in Figure 11c. In other words, both push–pull-side switches are turned on. Therefore, the voltage of and is given as follows:Therefore, both inductors discharge the stored energy to in the step-down mode, or they are charged by in the step-up mode. Thus, there is no power flow between the primary and secondary sides via the transformer during this interval.

- Interval 3 ∼At , is turned on and is turned off while is turned on, as shown in Figure 11d. The operations in Interval 1 and Interval 3 are similar to each other, and thus, the following holds:In the step-down mode, is energized by the transformer. The power starts to flow from the primary side to the secondary side. Therefore, stores energy and increases. Similarly to in Interval 1, releases energy to .In the step-up mode, releases energy to the primary side of the transformer, and is charged while is discharged by the primary reflected current of . In this mode, stores energy through .

- Interval 4 ∼At , is turned off to ensure the deadtime for the half-bridge, and is turned on while keeping on. It operates in a similar way to Interval 2, as shown in Figure 11e, and the following holds:Both inductors are to store energy in step-up mode operation or release energy in step-down mode operation during this time interval. By the voltage-second balance of and , the voltage step-down ratio of the converter can be defined as a function of the primary-side switch duty ratio (D) and the transformer turn ratio (N) as follows:where D is the duty cycle of primary-side switching components, and . Since the voltage ratio is the reciprocal of (36) when the power flow reverses, increasing the transformer turn ratio N yields a reduced voltage ratio during discharge operation and an increased voltage ratio during charging.

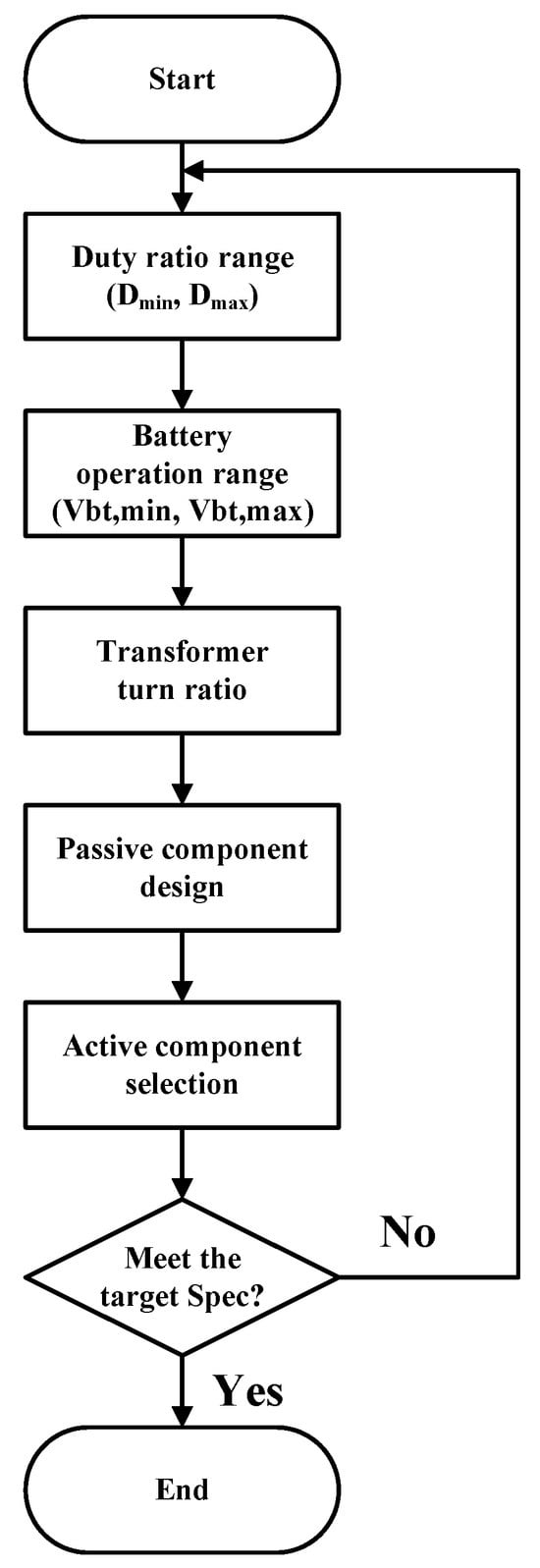

3.4. Design Procedure

- Duty cycle (D)The first step is to select the duty cycle of the converter. In this study, the duty cycle of the primary-side switches (, ) is defined as D, while the duty cycle of the secondary-side switches (, ) is controlled as .

- Battery voltage range (, )Next, according to the dc bus voltage , the battery operating range must be determined. Assuming that the converter output current () is controlled to be constant during the battery discharge mode, the range of in the discharge mode is defined by the following equation:Considering the voltage step-down ratio defined in (36), it must satisfy the following relationships:andThus, and can be described as follows:To lower , must be set close to . However, as indicated by (41), this requirement, combined with the constraint, necessitates a high turn ratio (N). From (43), it is evident that as the turn ratio (N) increases, the battery voltage ratio approaches unity. This implies that a high N significantly narrows the battery’s operational voltage range, as is constrained to be very close to . Therefore, a clear trade-off exists between the battery operating voltage range and the transformer turn ratio. If the target BESS employs a battery type whose terminal voltage varies significantly with the state of charge—such as Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) or sodium-based batteries—a relatively low turn ratio N becomes essential to secure a sufficiently wide operating voltage window. In contrast, for chemistries such as Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP), where the voltage variation over the SOC range is comparatively small, a higher turn ratio can still cover most of the usable range, while also helping reduce .

- Transformer turn ratio (N)The feasible range for the transformer turn ratio (N) is determined by the constraints derived in the previous section. From the maximum battery voltage condition (39), the lower limit of N is obtained by rearranging the terms as follows:

- Passive component designand are calculated by the inductor ripple current specification:where is the ripple current of the dc bus. From (46), N and are fixed values, and determines the value of L. Since the term reaches its maximum value at , it is advisable to design at to become the midpoint of the battery operation range. in (46) can therefore be treated asThe values of the half-bridge-side filter capacitors, and , are calculated in the step-up mode operation of the converter, while the value of the push–pull-side filter capacitor is calculated in the step-down mode operation by the capacitor voltage ripple specifications, as follows:where and represent the voltage ripple of the capacitors , , and , respectively, and is the total current of the push–pull side denoted in Figure 11a, which is described as

- Active component designThe drain-to-source voltage stresses for the primary () and secondary () sides are given by (51) and (52), respectively:Assuming that the current ripple is negligible, the RMS currents for the primary () and secondary () sides are expressed as (53) and (54), respectively:Therefore, the switching devices for both sides must be selected with voltage and current ratings that provide a sufficient margin above these calculated stresses (the voltage and the RMS current) to ensure reliable operation. The entire design flow is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Design flow of proposed procedure.

Figure 13. Design flow of proposed procedure.

3.5. Loss Breakdown

To analyze the power loss of the converter, the losses of the transformer and inductors are assumed to be negligible. Therefore, in this section, the total converter power loss is approximated as the power loss of the MOSFETs. The MOSFET losses consist of conduction loss, switching loss, output capacitance loss, and body diode loss, as described in ref. [53]. The MOSFET conduction loss is caused by the drain-to-source current flowing through the on-state channel resistance during the conduction interval. The conduction loss is calculated as

where is the drain-to-source current, is the on-state resistance, D is the duty cycle, and is the number of MOSFETs. The switching loss is determined by the total energy dissipated during the turn-on and turn-off transitions. The average switching power loss is expressed as

where is the drain-to-source voltage, and are the turn-on and turn-off times of the MOSFET, and is the switching frequency. The loss represents the energy dissipated during the charging and discharging of the MOSFET output capacitance in each switching cycle and is given by

where is the output capacitance energy loss per switching event, which can be obtained from the device datasheet. The body diode loss is the power dissipated when the intrinsic body diode conducts current, typically during deadtime intervals or reverse current operation. This loss is caused by the forward voltage drop of the diode and is calculated as

where is the diode forward voltage, and is the fraction of time during which the diode conducts. Finally, the total MOSFET power loss is calculated as

4. Design Implementation and Validation

4.1. Simulation

To verify the proposed design approach for the 15 kW partial power processing (PPP) system, an HBPP converter was designed. The duty ratio D was constrained to the range of 10% to 45%, reflecting the duty-cycle limitation of the half-bridge topology, and the battery voltage range was specified as 350–360 V. Based on these specifications, the transformer turn ratio N was determined using (45) and was required to be less than 2.625. Accordingly, the nearest feasible value, , was selected. For an operating bus current of = 35 A, the inductances and were each designed as 100 uH to limit the current ripple to below 5%. Furthermore, to constrain the voltage deviation and limit the battery-side voltage ripple to 0.5%, the capacitors and were designed as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

BESS specifications and electrical grid parameters.

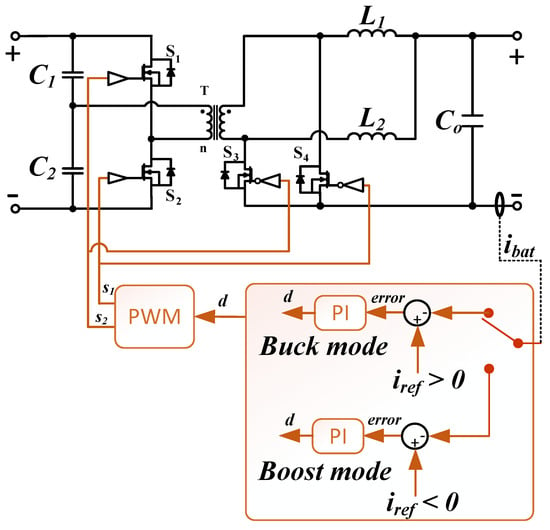

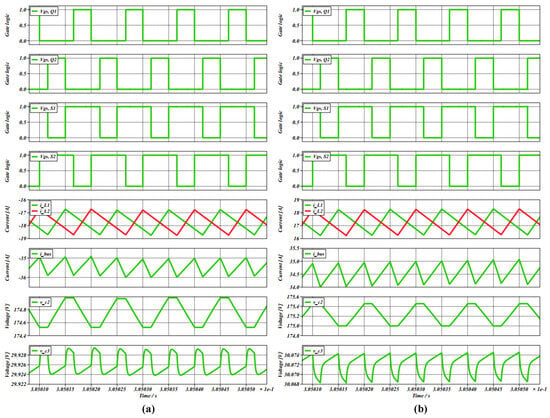

The operation of the designed converter was first verified through PLECS simulation [54]. As shown in this figure, two separate PI controllers were designed based on the converter modeling approach presented in ref. [53].

In buck mode, when energy is transferred from the high-voltage side to the low-voltage side, the reference current is set to a positive value. Conversely, in boost mode, when energy flows from the low-voltage side to the high-voltage side, the reference current is assigned a negative value. The converter was operated under constant current (CC) control with = ± 35 A across all voltage ranges, based on the control strategy shown in Figure 14. Here, is the reference current used to regulate at a constant level.

Figure 14.

Control strategy of HBPP converter.

Figure 15 illustrates the simulation waveforms. The parameters used in the simulation are listed in Table 2. To limit to less than 1.2 A, and were designed to be 100 uH. The simulation results confirm this, showing a measured of approximately 1.07 A. The capacitors , and were designed using (48) and (49), respectively. The maximum voltage ripple was designed to be 0.5% of for and , and 0.05% of for . The simulation confirmed that was approximately 0.31% and was under 0.03%, thus satisfying the design requirements.

Figure 15.

Simulation waveform of the proposed topology: (a) battery charging mode, (b) battery discharging mode.

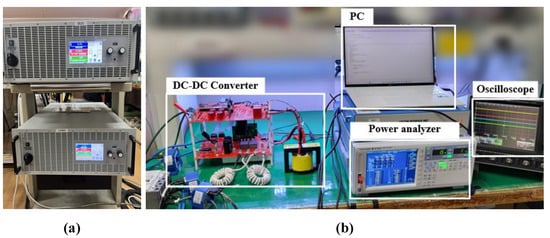

4.2. Experimental Validation

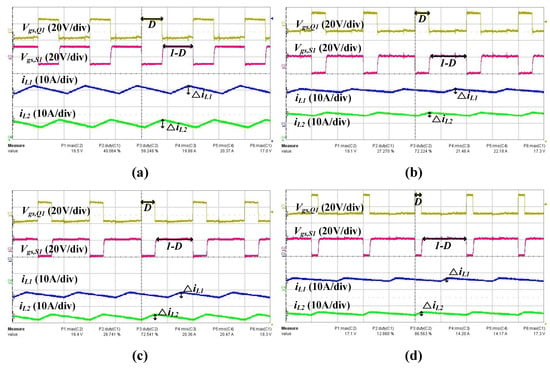

Figure 16b shows the prototype converter, along with the test environment used for its evaluation. Two bidirectional power supplies shown in Figure 16a are used as the battery and dc bus. Figure 17 displays the primary waveforms of the converter during operation in a 35 A constant current (CC) mode. The measurements encompass the gate-source signals of switching components and and the currents of and , respectively. In more detail, the overall operation waveforms of the battery charging mode in Figure 17a and the battery discharging mode in Figure 17b are similar to each other, with the direction of and inversed.

Figure 16.

Hardware configuration: (a) bidirectional power supplies, (b) overall view of converter hardware setup.

Figure 17.

Converter operation waveforms: (a,b) discharging at 350 V and 360 V, (c,d) charging at 350 V and 360 V.

Unlike the simulation, which assumes a relatively ideal environment, the hardware validation stage showed some voltage drops in both the dc bus and the battery. This effect is largely influenced by the resistance of the wiring used to connect the dc bus and the battery to the converter, with each wire having a resistance of approximately 0.1 . Including these additional voltage drops in (36), the achievable in the simulation stage may exceed the duty range in the actual hardware experiment, making it unattainable. Considering this, the maximum during operation was limited to 35 A in the hardware verification stage.

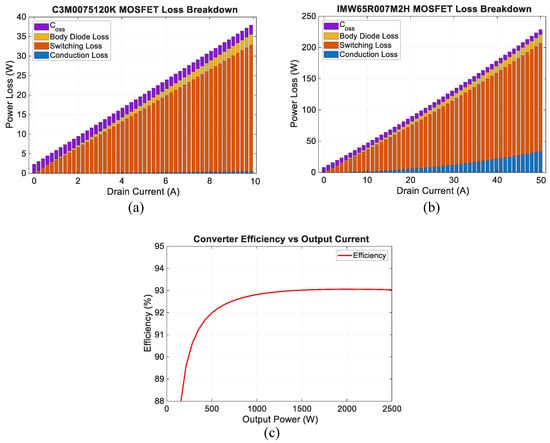

Figure 18 presents the loss breakdown analysis using the C3M0075120K MOSFET on the high-voltage side and the IMW65R007M2H MOSFET on the low-voltage side. The simulation results indicate that the primary-side switches experience high voltage stress but relatively low current conduction, resulting in comparatively low power loss. The maximum power loss on the high-voltage side is 37.9 W under the 2.5 kW operating condition, as shown in Figure 18a. In contrast, the low-voltage-side MOSFETs experience significantly higher current stress, leading to substantially higher power loss. As shown in Figure 18b, the maximum loss on the low-voltage side reaches 228.7 W under the 2.5 kW load condition. Based on these results, the overall converter efficiency is estimated to reach approximately 93% at full load.

Figure 18.

Loss breakdown analysis: (a) primary switches using C3M0075120K, (b) secondary switches using IMW65R007M2H, and (c) HPBB converter efficiency.

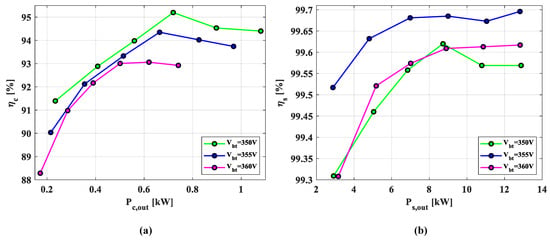

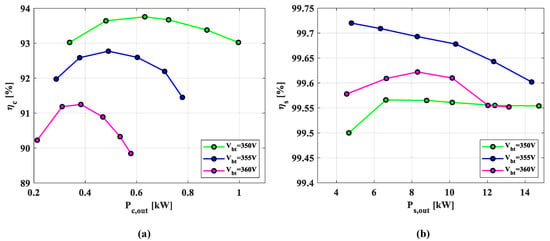

Figure 19 illustrates the efficiency of the converter and system with various battery voltages under a constant . While the maximum efficiency of the converter is approximately 95.2% at = 720 W, the system efficiency remained above 99.3% across the entire operating range. A similar trend is observed in the charging mode shown in Figure 20; while the converter efficiency peaks at approximately 93.7% at = 630 W, the system efficiency consistently remains above 99%. From Figure 19a, although the converter efficiency () at = 360 V is the lowest among the tested conditions, the power processing ratio at this voltage is the lowest as well. As a result, the overall system efficiency () shown in Figure 19b remains comparable to that at = 350 V. Similar behavior is observed in the charging mode results of Figure 20. At = 360 V, converter efficiency again reaches its minimum; however, due to the relatively low , the system efficiency at this voltage becomes comparable to that of the = 350 V. However, the system efficiency at = 360 V still remains lower than that at = 355 V. This suggests that both the power processing ratio and the converter efficiency must be jointly considered to achieve higher system efficiency.

Figure 19.

Measured efficiency in discharging mode: (a) converter, (b) system.

Figure 20.

Measured efficiency in charging mode: (a) converter, (b) system.

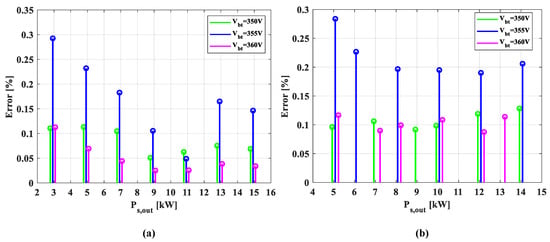

Figure 21 presents an error analysis plot of the theoretical efficiency against the empirically measured efficiency in the battery discharging mode in (a) and the charging mode operation in (b). The theoretical system efficiency was calculated using (10), where was calculated based on (22). When calculating system efficiency , measured converter efficiency from the power analyzer is used. Even though the measured system efficiency and the theoretical system efficiency differ by only a small margin up to 0.3%, it was confirmed that the two values are very similar to each other.

Figure 21.

Error analysis of theoretical and measured system efficiency: (a) battery charging mode, (b) battery discharging mode.

Table 3 presents the key operating parameters of the proposed converter under varying battery voltage conditions, from 350 V to 360 V. As the battery voltage varies within this range, the peak current of the secondary-side MOSFET remains relatively stable, with values of 37.11 A, 34.622 A, and 35.94 A, respectively. This current behavior demonstrates that the proposed power-handling strategy prevents excessive semiconductor stress under constant power operating conditions. Furthermore, the inductance of and is fixed at 100 uH for all operating points, ensuring the same current ripple characteristic across the entire voltage range. This design choice allows for a fair comparison of device stress and loss distribution, as variations in current ripple and switching dynamics are minimized.

Table 3.

Summary of key parameters under different conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the design considerations of bidirectional partial power processing (PPP) converters for battery energy storage systems (BESSs), focusing on achieving high system efficiency while reducing converter size and power-handling requirements. By analyzing the characteristics of PPP-based architectures, the half-bridge push–pull (HBPP) structure was selected as a suitable topology due to its reduced conduction loss, minimized device stress, and favorable current characteristics on the secondary side. A detailed operational analysis was provided, including interval-based switching behavior and voltage gain derivation, and a systematic design procedure was established to guide the selection of the duty ratio, transformer turn ratio, and passive and active components under practical battery voltage conditions.

The feasibility and performance of the proposed design were validated through simulation and hardware experiments on a 15 kW BESS hardware test bed. This prototype successfully demonstrated stable bidirectional power flow and achieved a peak system efficiency exceeding 99.4%, confirming the beneficial impact of PPP in reducing processed power and improving overall energy conversion performance. Although the converter efficiency remained below 91% at partial load, the experimental results verified that the overall system efficiency is significantly enhanced due to the small power processing ratio, in accordance with the analytical expectations. Minor discrepancies between simulation and experimental current limits were attributed to parasitic resistance and minimum duty constraints, indicating areas for hardware refinement.

The analysis and results of this work highlight the practical value of PPP-based converter architectures for next-generation energy storage systems, where high efficiency, modular scalability, and reduced converter rating are essential. Future research will focus on optimizing soft-switching conditions, extending the design methodology to higher-power or higher-frequency operation. The proposed converter can also be investigated within grid-connected parallel BESS architectures using partial power processing, including the development of advanced control strategies. Furthermore, extending the concept to hybrid ESS configurations that integrate additional storage elements—such as hydrogen fuel cells—offers another promising direction. Finally, system-level evaluation of long-term reliability and large-scale parallel operation remains essential for further improving the practicality of the proposed HBPP-PPP topology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-J.J., N.-A.N. and N.-T.P.; funding acquisition, S.-J.C.; investigation, S.-J.J., N.-A.N. and N.-T.P.; methodology, S.-J.J., N.-A.N., N.-T.P., J.-S.P. and S.-J.C.; project administration, S.-J.C.; resources, S.-J.C.; supervision, S.-J.C.; validation, S.-J.J., N.-A.N., N.-T.P., J.-S.P. and S.-J.C.; visualization, S.-J.J., N.-A.N., N.-T.P. and J.-S.P.; writing—original draft, S.-J.J. and N.-A.N.; writing—review and editing, S.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by a Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2025-02263945, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation) and by the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Ulsan RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ulsan Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-07-001).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050; COM (2011)112 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024. 2024. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a9e3544b-0b12-4e15-b407-65f5c8ce1b5f/GlobalEVOutlook2024.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Kim, J.; Song, J.; Kim, C.H.; Mahseredjian, J.; Kim, S. Consideration on the Present and Future of Battery Energy Storage System to Unlock Battery Value. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 13, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.M.; Esan, O.C.; Ijaola, A.O.; Farayibi, P.K. Advancements in hybrid energy storage systems for enhancing renewable energy-to-grid integration. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, G.G.; Manalastas, W.; Tafti, H.D.; Ceballos, S.; Sanchez-Ruiz, A.; Lovell, E.C.; Konstantinou, G.; Townsend, C.D.; Srinivasan, M.; Pou, J. Grid-Connected Energy Storage Systems: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguenon, L.; Yamegueu, D.; Gomna, A. Overcoming the challenges of integrating variable renewable energy to the grid: A comprehensive review of electrochemical battery storage systems. J. Power Sources 2023, 580, 233343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkin, I.A.; Blinov, A.; Vorobyov, M.; Bubovich, A.; Saltanovs, R.; Peftitsis, D. Interface Converters for Residential Battery Energy Storage Systems: Practices, Difficulties and Prospects. Energies 2021, 14, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, M.O.; Buswig, Y.; Hossain, M.L.; Abu-Siada, A. Recent progress and future trends on the state of charge estimation methods to improve battery-storage efficiency: A review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 8, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Chen, C.; Shi, H.; Yao, Z. State of charge estimation of battery energy storage systems based on adaptive unscented Kalman filter with a noise statistics estimator. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 13202–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Na, S.J.; Cho, I.H. Research on improving the reliability and reducing the weight of battery packs for railway vehicles. J. Power Electron. 2024, 24, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciato, M.; Nobile, G.; Scarcella, G.; Scelba, G. Real-time model-based estimation of SOC and SOH for energy storage systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Feng, C.; Li, L.; Wu, Q. Combined EKF–LSTM algorithm-based enhanced state-of-charge estimation for energy storage container cells. J. Power Electron. 2024, 24, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.; Ferreira, A.; Pomilio, J. Control strategy for battery-ultracapacitor hybrid energy storage system. In Proceedings of the 2009 Twenty-Fourth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Washington, DC, USA, 15–19 February 2009; pp. 826–832. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, A.; Gatto, G.; Marongiu, I.; Porru, M.; Serpi, A. Real-time control strategy of energy storage systems for renewable energy sources exploitation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2013, 5, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Gao, D.W.; Xu, B. MDT-MVMD-based frequency modulation for photovoltaic energy storage systems. J. Power Electron. 2025, 25, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleke, S.; Baran, M.E.; Huang, A.Q.; Bhattacharya, S.; Anderson, L. Control strategies for battery energy storage for wind farm dispatching. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2009, 24, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xiong, L.; Ban, C.; Huang, S. Distributed sliding mode consensus control of energy storage systems in wind farms for power system frequency regulation. J. Power Electron. 2024, 24, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Guo, H. Hierarchical cooperative control strategy for battery storage system in islanded DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 37, 4028–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.A.H.; Bauman, J. A Comprehensive Review of DC Fast-Charging Stations With Energy Storage: Architectures, Power Converters, and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, T.S.; Vasudevan, K.R.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Sani, S.B.; Chemud, S.; Lajim, R.M. A Comprehensive Review of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems: Converter Topologies, Control Strategies and Future Prospects. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 148702–148721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cao, X.; Cao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Pei, J.; Lei, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, R.; Li, J. A review of power conversion systems and design schemes of high-capacity battery energy storage systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52030–52042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, T.; Lehn, P.W. Evaluation of emerging modular multilevel converters for BESS applications. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2014, 29, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, N.G.F.; Zientarski, J.R.R.; da Silva Martins, M.L. A review of series-connected partial power converters for DC–DC applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 10, 7825–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamy, M.S.; Harfman-Todorovic, M.; Elasser, A.; Chi, S.; Steigerwald, R.L.; Sabate, J.A.; McCann, A.J.; Zhang, L.; Mueller, F.J. An efficient partial power processing DC/DC converter for distributed PV architectures. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 29, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientarski, J.R.R.; da Silva Martins, M.L.; Pinheiro, J.R.; Hey, H.L. Evaluation of power processing in series-connected partial-power converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2018, 7, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzola, J.; Aizpuru, I.; Arruti, A. Partial power processing based converter for electric vehicle fast charging stations. Electronics 2021, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzola, J.; Aizpuru, I.; Romero, A.A.; Loiti, A.A.; Lopez-Erauskin, R.; Artal-Sevil, J.S.; Bernal, C. Review of architectures based on partial power processing for dc-dc applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 103405–103418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, M.C.; Zhang, Z.; Jørgensen, K.L.; Andersen, M.A. Fractional charging converter with high efficiency and low cost for electrochemical energy storage devices. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 7461–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.J.; Baliga, B.J. Design and Economic Considerations to Achieve the Price Parity of SiC MOSFETs with Silicon IGBTs. In Proceedings of the Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publ: Baech, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 858, pp. 889–893. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.D.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, T.J.; Yoo, D.W.; Song, E.H. A new topology with high efficiency throughout all load range for photovoltaic PCS. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 56, 4427–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, J.; Han, Y. PV balancers: Concept, architectures, and realization. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 30, 3479–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbino, A.J.; Tanca-Villanueva, M.C.; Lazzarin, T.B. A full-bridge partial-power processing converter applied to small wind turbines systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 29th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Delft, The Netherlands, 17–19 June 2020; pp. 985–990. [Google Scholar]

- Granello, P.; Soeiro, T.B.; Van Der Blij, N.H.; Bauer, P. Revisiting the partial power processing concept: Case study of a 5-kW 99.11% efficient flyback converter-based battery charger. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3934–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, V.M.; Gulur, S.; Gohil, G.; Bhattacharya, S. An approach towards extreme fast charging station power delivery for electric vehicles with partial power processing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 8076–8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ngo, M.; Yan, N.; Dong, D.; Burgos, R.; Ismail, A. Design and implementation of an 18-kW 500-kHz 98.8% efficiency high-density battery charger with partial power processing. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 10, 7963–7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahim, O.; Chub, A.; Blinov, A.; Vinnikov, D. Current-fed dual inductor push-pull partial power converter. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 20th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC), Brasov, Romania, 25–28 September 2022; pp. 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Pape, M.; Kazerani, M. Turbine Startup and Shutdown in Wind Farms Featuring Partial Power Processing Converters. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2020, 7, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, M.C.; Zhang, Z.; Andersen, M.A. Review of high efficiency bidirectional dc-dc topologies with high voltage gain. In Proceedings of the 2017 52nd International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Heraklion, Greece, 28–31 August 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, V.M.; Gulur, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Ramabhadran, R. A partial power converter interface for battery energy storage integration with a DC microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 September–3 October 2019; pp. 5783–5790. [Google Scholar]

- Shousha, M.; Prodić, A.; Marten, V.; Milios, J. Design and implementation of assisting converter-based integrated battery management system for electromobility applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2017, 6, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, H.; Xu, P.; Hu, H.; Wan, C. A high step-down non-isolated bus converter with partial power conversion based on synchronous LLC resonant converter. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Charlotte, NC, USA, 15–19 March 2015; pp. 1950–1955. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N.; Kouro, S.; Zanchetta, P.; Wheeler, P. Bidirectional partial power converter interface for energy storage systems to provide peak shaving in grid-tied PV plants. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Lyon, France, 20–22 February 2018; pp. 892–897. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Tamballa, S.; Pallantala, M.; Raju, S.; Mohan, N. Cascaded dual-active bridge cell based partial power converter for battery emulation. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–20 June 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pape, M.; Kazerani, M. An offshore wind farm with DC collection system featuring differential power processing. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 35, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Chen, L.; Shan, Z.; Gao, F.; Chen, H.; Sha, D.; Dragičević, T. Modeling and advanced control of dual-active-bridge DC–DC converters: A review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 1524–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Ayyanar, R. PWM control of dual active bridge: Comprehensive analysis and experimental verification. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 26, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Malekjamshidi, Z.; Zhu, J.G. Analysis of operation modes and limitations of dual active bridge phase shift converter. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 11th International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems, Sydney, Australia, 9–12 June 2015; pp. 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Moo, C.S.; Ng, K.S.; Hsieh, Y.C. Parallel operation of battery power modules. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2008, 23, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Mao, S.; Shen, F. Virtual DC machine-based distributed SoC balancing control strategy for parallel battery storage units in DC microgrids. J. Power Electron. 2025, 25, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yeates, K.; Han, Y. Analysis of high efficiency DC/DC converter processing partial input/output power. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 14th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 23–26 June 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alemanno, A.; Morici, R.; Pretelli, M.; Florian, C. Design of a 7.5 kW dual active bridge converter in 650 V GaN technology for charging applications. Electronics 2023, 12, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. Fully ZVS, minimum RMS current operation of the dual-active half-bridge converter using closed-loop three-degree-of-freedom control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 10188–10199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, R.W.; Maksimovic, D. Fundamentals of Power Electronics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plexim GmbH. PLECS User Manual. 2025. Available online: https://www.plexim.com (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.