Abstract

The development of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and other applications requires numerous complex and time-consuming research efforts. Numerical modeling can significantly reduce both the scope and duration of laboratory testing by enabling rapid prediction of cell behavior under various operating conditions. In this study, it is demonstrated that the parameters of the Newman–Tiedemann–Gu–Kim (NTGK) battery model can be determined using only extreme discharge current values, omitting intermediate currents. This approach increases the average voltage error by 0.23% but reduces the average temperature error by 0.22%. Additionally, the use of limited experimental data leads to extrapolation errors at an 8 A discharge current from 1.20% to 0.65% for voltage and from 7.04% to 5.78% for temperature. Furthermore, the proposed model enables accurate prediction of the state of charge (SoC) and battery temperature evolution without additional measurements under realistic driving conditions, such as the Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicle Test Cycle (WLTC).

1. Introduction

The number and diversity of large batteries used in modern light-duty, heavy-duty, and L-category vehicles have increased dramatically over the past decade. Battery design, R&D, and performance and validation testing, as well as durability and safety analysis, have become critical elements of the product development cycle for passenger cars (PCs) and other vehicle categories. In the case of passenger cars, more than 50% of new vehicles sold in the EU are now electrified (BEV, PHEV, or HEV), while most L-category vehicles are of the BEV type [1,2].

Battery testing is a broad and evolving field that encompasses basic and advanced test methodologies. Such testing is generally divided into two categories based on its purpose:

- (1)

- Tests performed according to procedures developed by battery manufacturers and international standards such as the ISO 16750 series [3], ISO 12405-4 [4], and ISO 6469-1 [5], aimed at verifying performance, reliability, and safety under defined operating conditions;

- (2)

- Certification and regulatory compliance tests conducted to confirm durability and safety for transport and market approval.

The transport of lithium batteries is regulated by national and international authorities such as the United Nations (UN), the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and the United States Department of Transportation (DOT). The tests are typically categorized as environmental, mechanical, thermal, or electrical. UN 38.3 of the Manual of Tests and Criteria establishes mandatory safety standards for transporting lithium cells and batteries—both lithium-ion and lithium-metal types—ensuring that they can withstand vibrations, shocks, and temperature variations during shipment to prevent fires or explosions. Manufacturers must also provide detailed test summaries for compliance [6]. In the United States, lithium primary and rechargeable batteries are regulated under the Code of Federal Regulations (49 CFR Parts 171–180), where most lithium batteries packed with equipment are classified as Class 9 hazardous materials and must comply with UN 38.3 testing requirements [7,8].

Certification (type-approval) tests are performed in accordance with Regulation UN No. 100 [9], which verifies battery safety and durability and authorizes products for market release. Test results are further used in certification processes for market approval and as input data for CO2 emission declarations for light-duty (LD) and heavy-duty (HD) vehicles. The EU’s CO2 emission regulations mandate substantial reductions compared with 2021 levels: 15% by 2025, 55% for PCs and 50% for LCVs by 2030, and a full phase-out of internal combustion engines (ICEs) by 2035 [10,11].

Battery performance evaluation typically follows international standards such as ISO 12405-4 (Electrically Propelled Road Vehicles—Test Specifications for Lithium-Ion Traction Battery Packs and Systems—Part 4: Performance Testing) [3] and OEM-specific standards that adapt international procedures to product-specific characteristics. Recent research has introduced additional diagnostic approaches [12] that estimate the state of health of lithium-ion cells using acoustic emission techniques, allowing real-time monitoring of mechanical degradation inside batteries. Other studies have explored thermal management improvements, such as the use of Tesla valves to maintain optimal cell temperatures in electric vehicles [13].

This article focuses on testing battery performance and durability. The basic tests performed on such components include the following:

- −

- Preconditioning of the device under test (DUT);

- −

- Measurement of energy and capacity at room temperature and under various discharge rates;

- −

- Power and internal resistance evaluation;

- −

- Assessment of state-of-charge (SoC) loss under no-load and storage conditions;

- −

- Cranking power tests at low and high temperatures;

- −

- Energy-efficiency measurements during normal and fast charging;

- −

- Cycle-life testing.

For compliance with the standards, the testing setup must include a climatic chamber capable of regulating temperatures from −30 °C to +50 °C (Figure 1) and bidirectional power sources (Figure 2), allowing cell and battery tests with voltage ranges up to 5 V DC for single cells and up to 1200 V DC for battery packs with current capacities from several amperes up to 1000 A.

Figure 1.

Climatic chambers—BOSMAL Battery Testing Laboratory.

Figure 2.

Bidirectional power sources—BOSMAL Battery Testing Laboratory.

The overall accuracy of externally measured or monitored values relative to specified or actual ones must remain within the following tolerances: voltage ± 1%; current ± 1%; temperature ± 2 K; and time ± 0.1%.

Numerical modeling can significantly reduce the time and scope of laboratory testing of lithium-ion cells and batteries, enabling rapid and reliable predictions of their behavior under various operating conditions. A modeling approach based on the equivalent circuit model (ECM) combined with a CFD-based thermal model has been proposed to predict the electrical performance and thermal characteristics of batteries [5]. Comparisons between ECM and physics-based models (PBM) for 60 Ah prismatic graphite/LiFePO4 batteries [6] indicate that ECMs are computationally efficient and reasonably accurate for low-to-moderate current intensities, whereas PBMs offer higher fidelity under high-rate or near-limit operating conditions close to full charge or discharge of the cell.

Thermal modeling approaches are typically divided into three categories: lumped, CFD, and physics-based electrochemical models. Lumped models approximate a cell as a homogeneous body, which makes them computationally efficient and suitable for real-time Battery Management System (BMS) applications [14]. However, such models cannot accurately capture internal temperature gradients at high C-rates. Thermal RC-network models, representing cells as an array of heat-capacity and resistance elements, predict bulk temperature under various loads but are unable to determine internal gradients at high C-rates [15,16]. CFD models, on the other hand, provide detailed two- and three-dimensional (2D/3D) spatial temperature distributions, which are invaluable for battery thermal management system (BTMS) design—especially for complex cooling solutions such as air channels, cooling plates, heat pipes, or immersion systems [17,18,19]. Nevertheless, CFD models are both computationally expensive and sensitive to parameter calibration. Physics-based electrochemical models, such as pseudo-two-dimensional (P2D) formulations, describe ion transport, charge conservation, and reaction kinetics to yield accurate estimates of heat generation [20,21]. Their reduced-order variants, including the Newman–Tiedemann–Gu–Kim (NTGK) model, achieve a favorable balance between physical accuracy and computational efficiency, though they remain highly sensitive to the selection of model parameters under dynamic current profiles [22,23]. Incorrect parameterization can significantly reduce predictive accuracy, especially when extrapolating across wide temperature or depth-of-discharge ranges [24,25]. Accurate determination of the heat generated within batteries is essential, since this energy directly affects thermal behavior and may also be recoverable for secondary applications [26,27].

Numerous computational tools are currently available for lithium-ion cell simulation, ranging from open-source to commercial packages offering capabilities that allow users to perform purely electrochemical simulations based on the Doyle–Fuller–Newman model or simulations combined with thermal/mechanical physics, which are described in [28]. However, a more detailed description of the processes occurring inside the cells requires significantly more experimental input data, and the computational algorithm is much longer. Therefore, simplified models such as NTGK remain widely used in engineering practice due to their reasonable accuracy and low computational cost. Despite the vast literature dedicated to experimental and numerical investigations of lithium-ion batteries, relatively few studies address how simulation can reduce the amount of necessary laboratory testing.

The present work aims to demonstrate that the NTGK model can effectively minimize the required experimental dataset while retaining high predictive accuracy, thus shortening the overall validation process for lithium-ion cells.

2. Mathematical Model

The transient thermal field inside a cylindrical lithium-ion cylindrical cell is governed by the following differential Equation (1):

The active zone is usually orthotropic, and , but the anode and the cathode can be assumed to be isotropic, .

To uniquely solve this equation, the initial condition

and a boundary condition, often in the form of a third-order condition on the outer surface of the cell,

are needed. In the last equation, h is the heat transfer coefficient to the environment at temperature Tf. Both of these quantities can change over time.

It is assumed that the cell is operated without an internal short circuit and there are no thermal runaway reactions. In such a case, in Equation (1) represents a volumetric heat source due to current transfer and electrochemical reactions:

where rp and rn are the electrical resistivity [Ω m] of the positive and negative electrodes, and ip and in are current density vectors [A/m2]. If internal short circuit or thermal runaway phenomena do occur, the proposed model is unable to take them into account, and the voltages and temperatures determined from it may differ significantly from those measured experimentally.

In this work, NTGK model [29] is used to formulate the volumetric current transfer rate j due to electrochemical reactions:

where Vol is the active volume of the cell; V is the battery cell voltage; Qnominal is the battery’s total electric capacity [Ah]; and Qref is the capacity of the battery that is used in experiments to obtain the model parameters U and Y.

U [V] and Y [A/V] and are functions of the battery depth of discharge DoD.

The coefficients an and bn in the functions U and Y can be determined from experimentally measured discharge rate characteristics for selected current intensities. For this purpose, a module in ANSYS software [30] can be applied. To obtain more accurate results, the algorithm proposed in [24] is used.

3. Materials and Methods

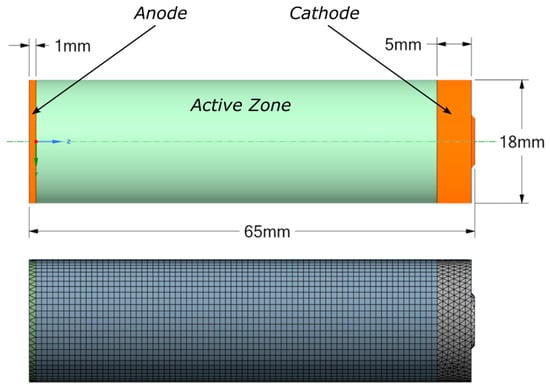

In this study, simulations are performed for a cylindrical 18,650 lithium-ion cell with a height of 65 mm and a diameter of 18 mm, whose specifications are listed in Table 1 [22]. The cell is of wound construction, consisting of alternating cathode and anode layers separated by a porous separator, impregnated with liquid electrolyte, and enclosed in a tubular metal casing. Within the NTGK framework, the detailed internal geometry (anode, cathode, separator, and electrolyte) is not represented explicitly; instead, it is homogenized into effective lumped parameters [30]. A simplified three-dimensional geometric model is developed that comprises three regions: the active zone, the anode, and the cathode, with the dimensions shown in Figure 3. All regions are discretized using hexahedral elements in the active zone and tetrahedral elements in the positive and negative zones.

Table 1.

Specifications for NCR18650GA.

Figure 3.

Battery model and its mesh structure.

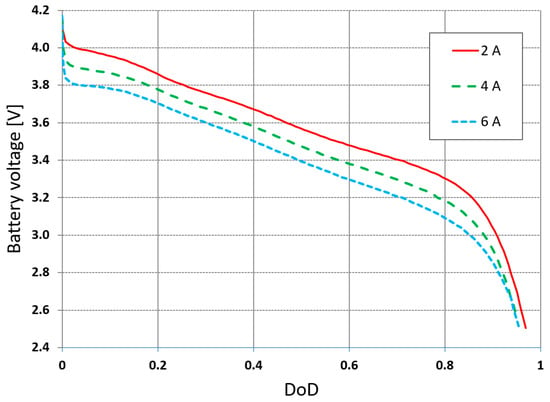

Material properties in Equations (1) and (3), such as specific heat (cp), density (ρ), and thermal conductivity (k), of the active, negative, and positive zones are presented in Table 2 [17]. They are assumed to be temperature-independent; the thermal conductivity in the active zone is orthotropic and isotropic in the cathode and the anode. Analysis taking into account the temperature-dependent material properties showed, similarly to [31], slight changes in the calculated temperatures in relation to the assumption of temperature-independent properties: an average difference of 0.07 °C, with a maximum deviation of 0.1 °C. The electrical resistivity rp and rn of the positive and negative electrodes in Equation (4) are 2.82 × 10−8 and 1.20 × 10−7 [Ω m]. The volumetric heat source due to electrochemical reactions in the active zone is calculated by the NTGK model based on Equations (4)–(8). To determine the coefficients in Equations (7) and (8), the results of laboratory tests related to battery discharge at selected flow currents in the external circuit are required. The first simulation uses all the measured values shown in Figure 4, i.e., the recorded cell voltage waveforms for the current flow during discharges of 2, 4, and 6 A [32].

Table 2.

Materials and properties of active, negative, and positive zones.

Figure 4.

Manufacturer’s discharge rate characteristics.

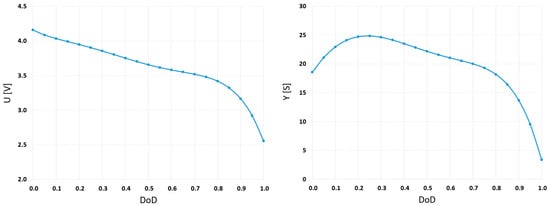

The coefficients in functions U and Y are evaluated based on the algorithm [17], which is applied in MATLAB R2023b software. The calculated values are presented in Table 3, and functions U and Y in Figure 5.

Table 3.

The estimated coefficients of the U and Y parameters based on (2, 4, 6 A) discharge rate characteristics.

Figure 5.

The estimated functions U and Y for NTGK model based on the manufacturer’s discharge rate characteristics for 2, 4, and 6 A.

The initial temperature in the condition described by Equation (2) is assumed to be 25 °C. In the boundary condition defined by Equation (3), h = 20 W/m2K and the ambient temperature Tf = 25 °C are assumed. Calculations are performed with a time step of 1 s. A mesh ensuring sufficient accuracy while reducing the computational cost is applied (element size of 1 mm, resulting in 69,605 elements). To avoid numerical inaccuracies, the influence of mesh refinement on the obtained results is examined. The element size is reduced to 0.5 mm, yielding 458,043 elements. The average temperature difference between the resulting temperature profiles is only 0.021 °C, while the maximum deviation reaches 0.027 °C. Reducing the element size significantly increases analysis time. Calculations for 1 mm and 0.5 mm meshes on a Dell-P7540 Intel i9-9980HK CPU @ 2.40 GHz computer take 21 min 15 s and 144 min 27 s, respectively. For this reason, all further simulations are performed for a finite element size of 1 mm and a time step of 25 s.

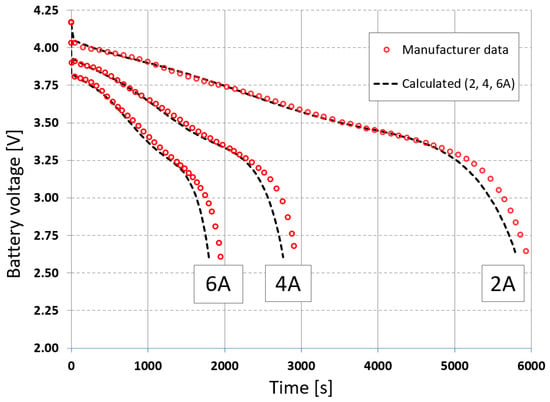

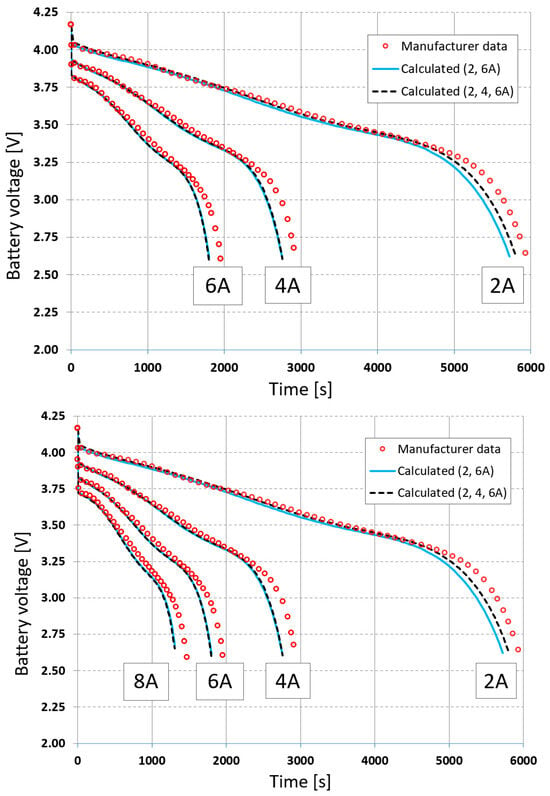

The developed numerical model allows for the determination of cell discharge curves at constant current values in the external circuit of 2, 4, and 6 A. Due to the previous measurements of these values made by the manufacturer, it is possible to compare the simulated values with the measured ones, which is shown in Figure 6. The upper cutoff voltage is 4.2 V, while the lower cutoff voltage is 2.6 V. The simulated voltages closely represent the actual data in the initial stages of discharge, but deviations occur later.

Figure 6.

Comparison of voltages at 2 A, 4 A, and 6 A for constant current loads.

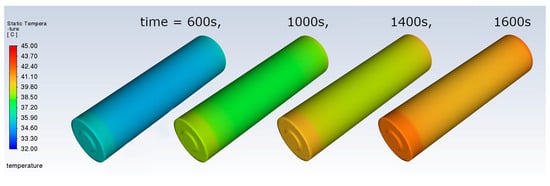

Additionally, the temperature distribution in the tested cell is simulated. Figure 7 presents the space temperature distribution for selected time steps when the current is set to 6 A.

Figure 7.

Space temperature distribution for selected time steps.

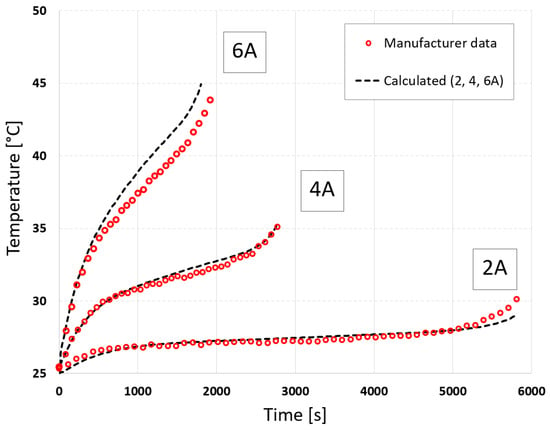

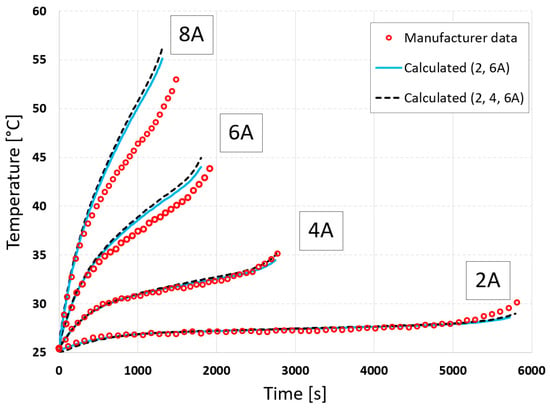

The determined transient temperature distributions can also be verified with the temperature curves of the outer cell surface, which is available from the manufacturer [22]. The obtained comparison is presented in Figure 8. Some differences are visible in the later stages of discharge for a current of 6 A. Worse accuracy towards the end of discharge is characteristic of the simplified NTGK model when the cell behavior becomes strongly nonlinear and transport-limited, which is not accounted for in this model.

Figure 8.

Comparison of simulated and measured cell surface temperature.

The accuracy of the obtained voltage and temperature waveforms is also assessed quantitatively. Among the many error metrics used to assess the accuracy of numerical models such as the Maximum Absolute Error and Coefficient of Determination, the most frequently used are Root Mean Square Error and Relative Percentage Error:

where N is the number of time steps. For the voltage curves at currents 2, 4, and 6 A, the errors obtained are 0.04 V, 0.07 V, and 0.06 V, and 0.65%, 1.03%, and 1.22%, respectively. For the temperature curves at currents 2, 4, and 6 A, the errors obtained are 0.21 °C, 0.29 °C, and 1.40 °C, and 3.37%, 0.76%, and 1.22%, respectively.

The NTGK model is then calibrated based on incomplete measurement data. We decided to use discharge curves only for the extreme currents in the external circuit, i.e., 2 and 6 A, while omitting the 4 A curve. The coefficients for the U and Y functions were determined using the same program in the MATLAB environment as for the full measurement data. Table 4 presents the calculated coefficients for incomplete measurement data.

Table 4.

The estimated coefficients of the U and Y parameters based on (2, 6 A) discharge rate characteristics.

As before, the cell discharge is modeled for three currents in the external circuit, and the calculated voltage and temperature curves are presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Comparison of voltages at 2 A, 4 A, and 6 A for constant current loads using full-data (2, 4, 6 A) and reduced-data (2, 6 A) calibration.

Figure 10.

Comparison of simulated and measured cell surface temperature using full-data (2, 4, 6 A) and reduced-data (2, 6 A) calibration.

Despite the limitation of the measurement data, the results obtained during cell discharge agreed with the values measured by the manufacturer and did not differ from those obtained for the full measurement data. For the voltage curves at currents 2, 4, and 6 A, the errors obtained were 0.08 V, 0.08 V, and 0.06 V, and 1.20%, 1.20%, and 1.17%, respectively. For the temperature curves at currents 2, 4, and 6 A, the errors obtained were 0.17 °C, 0.17 °C, and 1.05 °C, and 2.52%, 0.45%, and 1.17%, respectively.

Using limited data can lead to increased extrapolation errors outside this range. To verify this, calculations were also performed for a discharge current of 8 A. The calculation results using full and limited measurement data were compared with the measured data in Figure 9 and Figure 10. The errors obtained for voltage were 1.20% and 0.65%, and for temperature, they were 7.04% and 5.78%, respectively. The use of limited data therefore reduced extrapolation errors.

4. Dynamic Battery Simulation

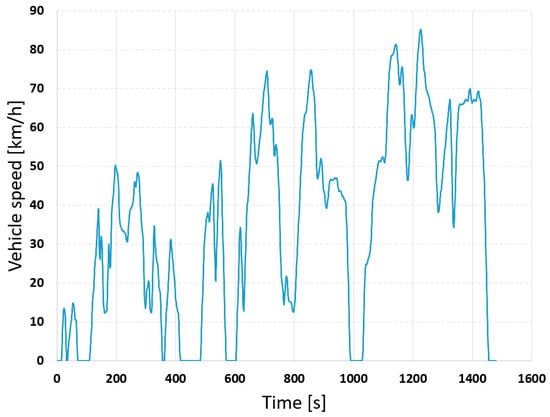

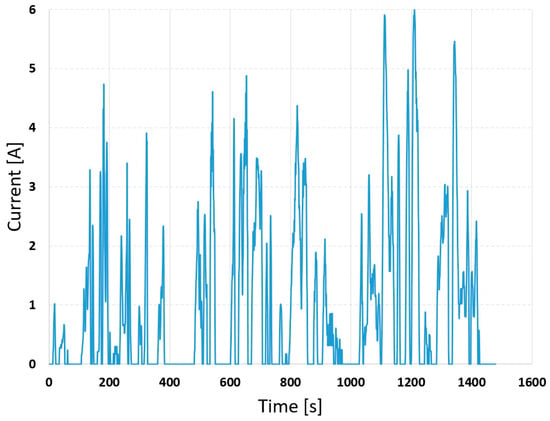

Additionally, the battery was analyzed under dynamic loading scenarios. The variable current profile was first generated based on an electric vehicle operating in the Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicle Test Cycle (WLTC) [33], and the maximum current was scaled to 6.0 A, without recuperation. The speed and current curves are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively.

Figure 11.

Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicle Test Cycle (WLTC).

Figure 12.

Scaled current profile under the WLTC-class 2.

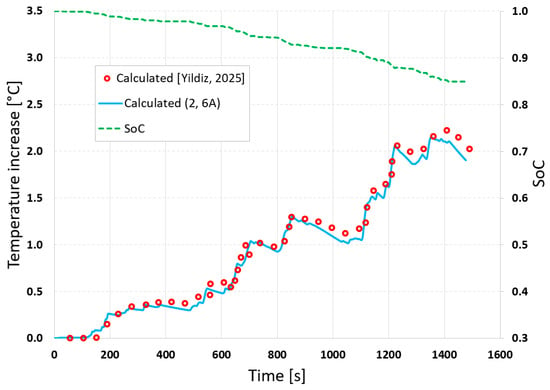

The NTGK model calibrated based on incomplete measurement data, i.e., for 2 and 6 A, was used for the calculations. It enabled the prediction of both electrical and thermal characteristics. To validate the model, the temperature curve obtained from the simulation was compared with results available from the literature [24]. Figure 13 also presents the SoC to which the battery is subjected in the simulation.

Figure 13.

Calculated, taken-from-the-literature [24] outer cell temperature and SoC during a single cycle.

The proposed model allows for the determination of the changes in SoC and battery temperature without the need to conduct measurements for a selected realistic drive cycle, such as WLTC. The model can also be used for long-term multi-cycle driving modes. Despite the use of incomplete data to calibrate the model, the obtained results are very similar to those obtained for the model based on full data.

5. Conclusions

The analyses presented in this study demonstrate that numerical modeling substantially reduces both the scope and duration of laboratory testing for lithium-ion cells and batteries, enabling rapid predictions of their behavior across diverse operating conditions. The Newman–Tiedemann–Gu–Kim (NTGK) model, when properly calibrated, delivers accurate voltage and temperature predictions over a wide range of discharge currents.

Key findings include that NTGK model parameters can be reliably identified using only extreme discharge current values (2 A and 6 A), omitting intermediate currents (4 A). This reduced calibration approach yields a modest 0.23% increase in average voltage error but achieves a 0.22% reduction in average temperature error. Moreover, it lowers extrapolation errors at an 8 A discharge current from 1.20% to 0.65% for voltage and from 7.04% to 5.78% for temperature.

The proposed model further enables accurate determination of state-of-charge (SoC) evolution and temperature profiles without additional experimental measurements under realistic driving cycles, such as the Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicle Test Cycle (WLTC). The predicted temperature rise over a single WLTC aligns closely with data in the literature, confirming the model’s robustness even with limited calibration data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D. and P.B.; methodology, P.D.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, P.D. and P.B.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.; writing—review and editing P.D. and P.B.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to legal reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Piotr Bielaczyc was employed by the BOSMAL Automotive Research & Development Institute Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| BTMS | Battery Thermal Management System |

| CFD | computational fluid dynamics |

| DC | direct current |

| DOT(US) | Department of Transportation (US) |

| ECM | equivalent circuit model |

| EVs | electric vehicles |

| HEVs | hybrid electric vehicles |

| ICE | internal combustion engine |

| ISO | International Standards Organization |

| LCV | light commercial vehicles (vans) |

| MSMD | multi scale multi domain |

| NTGK | The Newman–Tiedemann–Gu–Kim |

| PC | passenger car |

| PHEV | plug-in hybrid electric vehicle |

| PBM | physics-based model |

| RC | resistor–capacitor |

| REESS | rechargeable electric energy storage system |

| SoC | state of charge |

| SOH | state of health |

| UN | United Nations |

| WLTC | Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicle Test Cycle |

| WLTP | Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicle Test Procedure |

References

- Sawicz, W.; Bielaczyc, P. Development trends of vehicular batteries testing on the test rigs. In Proceedings of the SAE International Powertrains, Fuels & Lubricants Conference & Exhibition, Cracow, Poland, 6–8 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16750-1:2023; Road Vehicles—Environmental Conditions and Testing for Electrical and Electronic Equipment—Part 1: General; Part 2: Electrical Loads; Part 3: Mechanical Loads; Part 4: Climatic Loads; Part 5: Chemical Loads. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69568.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ISO 12405-4:2018; Electrically Propelled Road Vehicles—Test Specification for Lithium-Ion Traction Battery Packs and Systems—Part 4: Performance Testing. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71407.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ISO 6469-1:2019; Electrically Propelled Road Vehicles—Safety Specifications—Part 1: Rechargeable Energy Storage System (RESS). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:6469:-1:ed-3:v1:en (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- UNECE. Regulation No. 136—Uniform Provisions Concerning the Approval of Vehicles of Category L with Regard to Specific Requirements for the Electric Power Train; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/main/wp29/wp29regs/2016/R136e.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- United Nations. Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods—Manual of Tests and Criteria, 7th ed.; ST/SG/AC.10/11/Rev.7; Amend. 1, 2021; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Part 49 Code of Federal Regulations of the US Hazardous Materials Regulations (49 CFR Sections 100-185).

- Ruiz, V.; Pfrang, A.; Kriston, A.; Omar, N.; Van den Bossche, P.; Boon-Brett, L. A review of international abuse testing standards and regulations for lithium-ion batteries in electric and hybrid electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1427–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agreement Concerning the Adoption of Harmonized Technical United Nations Regulations for Wheeled Vehicles, Equipment and Parts Which Can Be Fitted and/or Be Used on Wheeled Vehicles and the Conditions for Reciprocal Recognition of Approvals Granted on the Basis of These United Nations Regulations Addendum 99: Regulation No. 100 Revision 3, E/ECE/324/Rev.2/Add.99/Rev.3 E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.2/Add.99/Rev.3. 23 March 2022. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-01/R0100r3e.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/631 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 Setting CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Passenger Cars and for New Light Commercial Vehicles, and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 443/2009 and (EU) No 510/2011 (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance.) PE/6/2019/REV/1. Current Consolidated Version: 09/07/2025. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/631/oj (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1242 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 Setting CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Heavy-Duty Vehicles. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1242/oj (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- He, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Tang, L.; Liu, F.; Li, Q.; Yin, Y.; Xu, S.; Deng, B. State of health estimation of lithium-ion battery based on full life cycle acoustic emission signals. J. Energy Storage 2025, 139, 118725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; He, L.; Deng, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, L. Performance study of Tesla valve-based direct cooling thermal management system for batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendecka, B.; Krastev, V.; Serao, P.; Bella, G. Experimental and numerical electro-thermal characterization of lithium-ion cells for vehicle battery pack applications. SAE Tech. Pap. 2023, 2023-24-0159, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagnoni, M.; Scarpelli, C.; Lutzemberger, G.; Bertei, A. Critical comparison of equivalent circuit and physics-based models for lithium-ion batteries: A graphite/lithium-iron-phosphate case study. J. Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allafi, W.; Zhang, C.; Uddin, K.; Worwood, D.; Dinh, T.Q.; Ormeno, P.A.; Li, K.; Marco, J. A lumped thermal model of lithium-ion battery cells considering radiative heat transfer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 141, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinejad, K.; Arunachala, R.; Arnold, S.; Ennifar, H.; Zhou, H.; Jossen, A.; Wen, C. A lumped electro-thermal model for Li-ion cells in electric vehicle application. World Electr. Veh. J. 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliaperumal, M.; Chidambaram, R.K. Thermal management of lithium-ion battery pack using equivalent circuit model. Vehicles 2024, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Qin, D.; Duan, Y. Thermal modeling and prediction of the lithium-ion battery based on driving behavior. Energies 2022, 15, 9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, T.; Shahbazian, H.; Hoseinalipour, M.; Sunden, B. 3D CFD modeling of cylindrical lithium-ion cells with anisotropic thermal conductivity. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 226, 120225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Guo, L.; Wu, L.; Jin, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, K. A novel extended Kalman filter-based battery internal and surface temperature estimation based on an improved electro-thermal model. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Ziebert, C.; Marzband, M. Thermal behavior modeling of lithium-ion batteries: A comprehensive review. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Yu, X. Simulation study on heat generation characteristics of lithium-ion battery aging process. Electronics 2023, 12, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.; Aktürk, A. Battery simulation using the NTGK model: Effects of model parameters and implementation under dynamic current profiles. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2025, 22, 0971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Li, X. Battery internal temperature estimation via double extended Kalman filtering. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 56, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.-Z.; Wu, Y.-X.; Ying, P.-J.; He, R.; Fu, C.-G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, T.-J. Application requirements and design strategies of Bi2Te3-based thermoelectric devices for low-quality thermal energy. cMat 2024, 1, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccha-Herrera, E.; Calderón-Muñoz, W.R.; Orchard, M.; Jaramillo, F.; Medjaher, K. Thermal modeling approaches for a LiCoO2 lithium-ion battery—A comparative study with experimental validation. Batteries 2020, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanoro, K.C.; Mercer, M.P.; Hoster, H.E. Assessment and comparative study of free and commercial numerical software packages for lithium-ion battery modeling. Adv. Theory Simul. 2025, 8, e00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.H.; Shin, C.B.; Kang, T.H.; Kim, C.-S. A two-dimensional modeling of a lithium-polymer battery. J. Power Sources 2006, 163, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS User’s Manual, Release 19.1; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2019.

- Murashko, K.A.; Pyrhönen, J.; Jokiniemi, J. Determination of the through-plane thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity of a Li-ion cylindrical cell. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 162, 120330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasonic Corporation. NCR18650GA Datasheet. Available online: https://www.orbtronic.com/ (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- UNECE. Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Cycle (WLTC). Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/doc/2012/wp29grpe/WLTP-DHC-12-07e.xls (accessed on 10 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.