Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly regarded as a transformative enabler of sustainable logistics and supply chain management, particularly in the context of global energy transition and decarbonization efforts. This study provides a comprehensive conceptual and exploratory assessment of the multidimensional role of AI, highlighting both its potential to enhance energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as its inherent environmental costs associated with digital infrastructures such as data centers. The findings reveal the dual character of digitalization: while predictive algorithms and digital twin applications facilitate demand forecasting, process optimization, and real-time adaptation to market fluctuations, they simultaneously generate additional energy demand that must be offset through renewable energy integration and intelligent energy balancing. The analysis underscores that the effectiveness of AI deployment cannot be captured solely through economic metrics but requires a holistic evaluation framework that incorporates environmental and social dimensions. Moreover, regional disparities are identified, with advanced economies accelerating AI-driven green transformations under regulatory and societal pressures, while developing economies face constraints linked to infrastructure gaps and investment limitations. The analysis emphasizes that AI-driven predictive models and digital twin applications are not only tools for energy optimization but also mechanisms that enhance systemic resilience by enabling risk anticipation, adaptive resource allocation, and continuity of operations in volatile environment. The contribution of this study lies in situating AI within the digital–green synergy discourse, demonstrating that its role in logistics decarbonization is conditional upon integrated energy–climate strategies, organizational change, and workforce reskilling. By synthesizing emerging evidence, this article provides actionable insights for policymakers, managers, and scholars, and calls for more rigorous empirical research across sectors, regions, and time horizons to verify the long-term sustainability impacts of AI-enabled solutions in supply chains.

1. Introduction

In the era of energy transition, geopolitical uncertainty, and rising sustainability requirements, the effective management of energy consumption in logistics and supply chain management (SCM) has become a critical challenge [1,2,3]. Logistics and supply chain operations are among the most energy-intensive activities in modern economies, generating a significant share of global energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [3]. Logistics and transport activities contribute a significant share of global energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, playing a major role in climate impact. Estimates suggest that these operations are responsible for roughly 7–11% of global emissions, with transport being the largest contributor [4,5]. At the same time, businesses are confronted with rising energy prices, frequent disruptions in energy supply, and tightening sustainability regulations, creating pressure to adopt advanced tools that minimize energy losses, optimize operations, and strengthen systemic resilience [6]. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a particularly promising solution in this context, with applications in logistics and supply chain management advancing rapidly [7,8]. Machine learning algorithms, predictive models, and digital twin technologies enable not only monitoring and forecasting of energy consumption but also real-time optimization of energy use in transport, warehousing, and production. However, the deployment of AI in logistics and SCM is associated with substantial increases in energy demand, particularly in the early stages of digitalization and infrastructure development [9]. On one hand, this enables the functioning and expansion of innovative digital solutions; on the other, it creates additional environmental burdens through higher GHG emissions and continued reliance on fossil fuels [6]. This duality underscores the need for sustainable energy sources to ensure the long-term viability of digital and AI-driven transformation. While digitalization initially drives significant increases in energy consumption, evidence suggests that, with appropriate policies and technologies, it may ultimately lead to improved efficiency and even reversal of the trend [10].

It can therefore be argued that organizations capable of using energy more efficiently in the implementation and operation of artificial intelligence (AI) tools within logistics processes will achieve higher levels of process management efficiency. Consequently, this capability may allow them to generate sustainable competitive advantage under conditions of increasing pressure from both energy transition and digitalization. The application of AI solutions and digital technologies, which by their very nature lead to increased energy demand, can only become a true source of competitive advantage when the costs of acquiring and utilizing energy are lower compared to those borne by competing entities. This means that the implementation of AI, while potentially improving process and decision-making efficiency, does not guarantee success if accompanied by a disproportionately high energy burden. Such efficiency can be achieved in several ways: by relying on more sustainable energy sources, optimizing energy consumption over time through demand-side management, employing algorithms that reduce computational intensity, and integrating distributed energy systems with logistics operations. From a strategic perspective, the organizations that will gain an advantage are those that not only implement AI tools in logistics but also develop intelligent mechanisms for balancing energy use. In doing so, digital technologies will enhance both operational efficiency and progress toward sustainability objectives.

The adoption of AI solutions in logistics and supply chain management inevitably leads to increased overall energy consumption, although the pace and scale of this growth vary across regions. These differences are shaped by regulatory barriers, the level of technological advancement and investment, market competition, and the degree of alignment with climate policies emphasizing energy efficiency. In this context, AI plays a particularly significant role, with its applications in logistics and energy management evolving rapidly [7]. Machine learning algorithms, predictive models, and digital twin concepts enable not only monitoring and forecasting of energy consumption but also dynamic optimization of energy use in transport, warehousing, and production processes. As a result, organizations can reduce operational costs, lower emissions, and increase the adaptability of supply chains to fluctuations in energy prices and disruptions in availability. The academic literature increasingly emphasizes the need to integrate energy management with the broader concept of systemic resilience, encompassing energy, financial, and operational dimensions [11,12]. Digitalization undoubtedly raises energy requirements but, if steered by appropriate strategies, it may simultaneously enhance systemic resilience [13]. Entities that can not only reduce their energy consumption but also use energy more intelligently with the support of AI may secure long-term strategic advantage, effectively “winning the energy race” while strengthening their competitive position. Nonetheless, empirical studies explicitly examining how AI tools support supply chain management in terms of energy efficiency and systemic resilience remain limited, representing an important gap in the current research landscape. The purpose of this article is to address the existing research gap by analyzing the role of AI in enhancing energy efficiency within logistics and supply chain management. Particular emphasis is placed on how AI-driven technologies not only influence energy consumption in transport, warehousing, and production processes but also shape the long-term trajectories of systemic resilience and decarbonization. This study examines both sides of the “energy race”: on the one hand, the rising demand for electricity resulting from large-scale adoption of AI tools, and on the other, the capacity of these tools to reduce inefficiencies, optimize operations, and foster sustainable growth in logistics networks.

The structure of the article is as follows: Section 2 outlines the global energy context and the challenges posed by the increasing demand from AI-related infrastructures. Section 3 discusses the energy consumption of AI in relation to supply chain processes and highlights its systemic implications. Section 4 analyzes the opportunities of AI to balance energy demand with efficiency gains across logistics operations. Section 5 explores alternative scenarios of electricity demand in AI-driven supply chains, while the calculations underlying these scenarios, together with the simulation framework, are pre-sented in Section 6. Section 7 presents the conclusions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

The methodological approach adopted in this study is conceptual and exploratory, designed to synthesize and extend the existing body of knowledge on the intersection of artificial intelligence, energy consumption, and supply chain transformation. Rather than testing a specific hypothesis, the research employs integrative theoretical analysis combined with systematic literature review to identify causal mechanisms and emerging patterns linking AI adoption with energy efficiency and systemic resilience. The methodological framework aligns with the logic of conceptual review articles, where the primary objective is to build a coherent model of understanding that bridges multiple disciplinary perspectives—energy systems, logistics management, and digital transformation. The analysis integrates data and insights from peer-reviewed journal articles, policy reports, and industrial case studies to ensure both academic rigor and practical relevance.

The article is organized in a sequential structure that mirrors the research logic. Section 2 reviews and categorizes the relevant literature across three analytical dimensions: (1) the energy implications of AI technologies, (2) their operational impact on logistics systems, and (3) their systemic influence on sustainability and resilience. Section 3 presents the theoretical and conceptual framework derived from systems theory and complex adaptive systems, while Section 4 and Section 5 apply these concepts to empirical and simulated contexts. Finally, Section 6 introduces the quantitative Scenario Simulation Framework, which operationalizes the conceptual model through scenario-based analysis. This design ensures methodological coherence between conceptual reasoning, theoretical synthesis, and empirical illustration, thereby fulfilling the exploratory and integrative goals of the study. This discussion is guided by the following research questions:

- −

- RQ1: To what extent can AI reduce energy consumption and emissions in logistics and supply chain management despite its own energy intensity?

- −

- RQ2: What technological, infrastructural, and organizational mechanisms are required to ensure that AI adoption contributes to systemic resilience and sustainable energy transitions?

In addition, given the current gap in empirical research directly addressing operational aspects of supply chains, this study introduces a third research question aimed at linking AI adoption to measurable energy outcomes at the process level:

- −

- RQ3: How do AI-enabled applications in logistics operations—such as transportation, warehousing, and port management—translate into measurable energy savings and emission reductions across different supply chain segments and regions?

By integrating this dimension, the analysis extends beyond macro-level considerations of digital infrastructures to the tangible impacts of AI on logistics efficiency and sustainability.

By addressing these questions, the article contributes to a deeper understanding of how AI can simultaneously act as both a driver of increased energy demand and a catalyst for efficiency improvements, ultimately shaping the sustainability and competitiveness of global supply chains.

2. Theoretical Background—Global Energy Context

The global demand for electricity is entering a new era of rapid growth, amplified by AI workloads, data centers, the electrification of transport and heating, and the spread of 5G networks. According to the International Energy Agency [4], global electricity consumption rose by 4.3% year-on-year in 2024, compared to 2.5% in 2023, with forecasts through 2027 suggesting continued growth at nearly 4% annually. Emerging and developing economies are expected to account for around 85% of this additional demand, with China alone contributing more than half.

Within this expansion, AI-related infrastructure is emerging as a major driver of demand. AI-dedicated data centers are particularly energy intensive, significantly contributing to load growth. In China, electricity demand has been rising faster than GDP since 2020, fuelled by clean energy manufacturing, electric vehicle adoption, intensive cooling, and data center capacity. Meanwhile, renewable energy deployment is accelerating at an unprecedented scale: by mid-2025 China surpassed 1.08 terawatts (TW) of cumulative installed solar PV capacity, representing a 56.9% year-on-year increase, while total generation capacity reached 3.61 TW [14].

The implications for logistics and supply chains are profound. Energy-intensive processes such as freight transportation, warehousing, and port operations are already responsible for up to 11% of global GHG emissions (Table 1). Estimates suggest that logistics operations alone account for around 22% of energy use across global supply chains [7]. The transport sector, which represents the backbone of logistics, accounts for approximately 15% of global GHG emissions and about 23% of global CO2 emissions related to energy use [15]. Freight transportation generates around 8% of global emissions, and when warehouses and ports are included, this share rises to about 11%. McKinsey [16] reports that logistics processes (transportation and warehousing combined) account for at least 7% of global GHG emissions, while the Rocky Mountain Institute [17] places this closer to 10%, noting that the sector also contributes significantly to air pollution. According to the IEA, CO2 emissions from transport reached nearly 8 gigatons in 2022, highlighting its critical role in energy-related emissions worldwide. These data confirm that logistics and transportation remain among the most emission- and energy-intensive segments of the global economy.

Table 1.

Energy intensity and emissions of logistics processes—overview across different operational scopes.

Table 1 highlights the structural energy intensity of logistics and freight processes. Against this backdrop, the additional electricity required to sustain AI-driven optimization could either reinforce unsustainable consumption patterns or, if coupled with renewable integration, accelerate decarbonization. In other words, the “energy race” in AI is also a race to determine whether global supply chains will become greener and more resilient or more energy-constrained and fragile. As AI systems become increasingly embedded in supply chain management—optimizing routing, demand forecasting, and warehouse operations—they both create opportunities for reducing inefficiencies and simultaneously drive higher energy requirements through intensive computation and digital infrastructure. The challenge lies in ensuring that the electricity enabling AI-enhanced logistics comes from low-carbon and reliable sources; otherwise, supply chains risk locking into higher emissions and greater exposure to volatile energy costs.

Analysis highlights the rapidly escalating electricity demand among leading technology companies, particularly in relation to their growing investment in artificial intelligence (AI). Google reported an increase from 21,776 GWh in 2022 to 25,307 GWh in 2023, largely driven by AI-related data center operations [20]. Samsung’s consumption reached nearly 30,000 GWh in the same year, comparable to the annual demand of entire nations such as Ireland or Serbia [21]. Similarly, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) consumed 24,775 GWh, placing its electricity use above that of Azerbaijan. Even smaller-scale operations (Table 2), such as NVIDIA (613 GWh) and Broadcom (417 GWh), surpassed the annual consumption of small island states, reflecting the pervasive energy intensity of semiconductor and AI-related industries [20].

Table 2.

Annual electricity consumption and costs of selected technology companies (2023–2024).

The financial implications of presented results are significant. Based on average 2023–2024 industrial electricity tariffs, annual expenditures ranged from approximately USD 54.6 million (Broadcom) to over USD 3 billion (Google, Samsung, TSMC). Despite the scale of these costs, most firms were capable of covering their entire annual electricity bills within several days of revenue—Apple within half a day, NVIDIA within a day, and Google in less than four. However, TSMC required over 17 days, with energy costs equaling nearly 5% of its annual revenue. These findings illustrate both the enormous purchasing power of technology giants and the structural vulnerability of their operations to fluctuating electricity markets.

From the perspective of supply chain management, this dynamic introduces additional layers of complexity. AI-driven demand for semiconductors, high-performance computing infrastructure, and renewable energy procurement places pressure on global logistics networks that must support both production and delivery of critical components. Semiconductor fabs such as TSMC’s are highly energy-intensive nodes within supply chains, while hyperscale data centers increasingly dictate the flow of hardware, cooling systems, and renewable power contracts. This means that disruptions in electricity supply or instability in renewable generation not only threaten corporate balance sheets but also reverberate across interconnected supply chains, amplifying systemic risks [22,23].

For instance [24] demonstrates that the digitalization of supply chains particularly through the implementation of AI-based predictive and optimization systems significantly improves energy efficiency, with the strongest effects observed in energy-intensive and high-emission industries. Their findings empirically confirm that AI can serve as a structural enabler of sustainable energy transition within logistics ecosystems. Similarly [25] propose an AI- and digital twin–based simulation framework for e-commerce supply chains, showing energy savings of 19.7% and emission reductions of 14.3% through adaptive optimization of operations and demand forecasting. These studies exemplify the growing body of evidence that links intelligent digitalization with measurable environmental and energy benefits.

The theoretical foundations of this study have been further reinforced by framing the relationship between artificial intelligence, energy use, and supply chain performance within the broader systems theory and complex adaptive systems (CAS) paradigm. In this view, supply chains are treated as open, dynamic socio-technical systems where energy flows, digital information, and material movements are interdependent and continuously co-evolve. Artificial intelligence acts as a catalytic mechanism of adaptation, enabling real-time decision-making, predictive optimization, and autonomous control that collectively alter the energy–information balance within logistics networks. This systemic lens supports a more comprehensive understanding of how technological innovation drives both efficiency and structural transformation in supply chains.

Furthermore, the analysis builds upon conceptual contributions from industrial ecology and sustainable systems management, which emphasize the coupling of energy and information flows in achieving long-term efficiency and decarbonization goals. Drawing on the logic of socio-metabolic transitions, the study positions AI-enabled logistics as a critical intermediary between resource inputs and sustainable operational outputs. This theoretical positioning allows the research to go beyond a descriptive account of energy use and instead explain the mechanistic pathways through which AI contributes to energy resilience, emission reduction, and circular performance improvement in logistics systems.

Finally, the revised conceptual framework integrates elements of resilience theory and transition management, allowing the discussion to capture not only efficiency-oriented outcomes but also the adaptive capacity of AI-driven supply chains under energy and operational uncertainties. From this perspective, AI-enabled systems are not static efficiency tools but dynamic infrastructures that strengthen the ability of organizations to anticipate, absorb, and respond to energy disruptions or environmental pressures. This integration provides a coherent theoretical foundation for the quantitative model presented later in the paper, which operationalizes these mechanisms through scenario-based simulation and system-level feedback analysis.

3. Energy Consumption of Artificial Intelligence and Supply Chain Implications

The diffusion of artificial intelligence (AI), and particularly generative AI (Gen-AI), has coincided with a notable acceleration in global energy demand. Empirical evidence demonstrates that inference queries to large language models (LLMs) require significantly more energy than conventional digital services. According to Goldman Sachs [26], a single ChatGPT query consumes approximately 2.9 watt-hours (Wh) of electricity, nearly ten times more than a standard Google search, which requires only 0.3 Wh. The International Energy Agency (IEA) [27] confirms this magnitude of difference, underscoring the energy intensity of Gen-AI. Training AI models is even more resource-intensive. The development of GPT-3 required energy equivalent to the annual consumption of around 130 U.S. households, while GPT-4 demanded nearly 50 times more. Estimates for GPT-5 suggest that training may have required more than eight times the energy of GPT-4, depending on hardware assumptions [20]. This scaling illustrates the exponential increase in energy required to sustain model advancement.

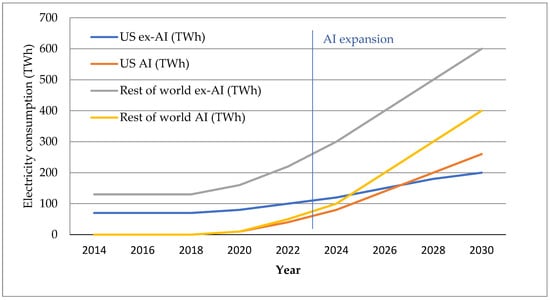

The operational side-AI inference at global scale is equally challenging. Estimates suggest that GPT-5 may consume ~18 Wh per query, compared to ~2.9 Wh for GPT-3.5. Given the reported 2.5 billion daily queries to OpenAI models, total consumption could reach 45 GWh per day, equivalent to the hourly output of a modern nuclear power plant operating at full capacity. While these values remain uncertain due to undisclosed infrastructure details, they reflect the order of magnitude of energy at stake. Data centers, the backbone of AI workloads, already account for 1–2% of global electricity demand. This share is expected to double to 3–4% by 2030, driven by AI adoption [25]. In the United States, Goldman Sachs [26] projects that data centers will consume 8% of total national electricity by 2030, compared with only 3% in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data center power demand (TWh). Based on [27,28].

This growth also entails parallel increases in carbon emissions and water use for cooling. Estimates of consumption at multiple scales are summarized in Table 3, ranging from single-query comparisons to national projections of data center demand.

Table 3.

Estimated electricity consumption of AI systems and data centers.

For supply chains, these dynamics imply a structural shift. AI adoption requires continuous availability of electricity not only for inference and training but also for upstream processes such as semiconductor fabrication, GPU production, and logistics of cooling and server components. Each of these layers embeds additional energy consumption into global supply chains, amplifying environmental footprints [9,29]. Moreover, increased energy demand intensifies competition for scarce resources—such as advanced chips and efficient cooling systems—adding volatility to logistics flows. The implications are profound. Tech corporations such as Google and Microsoft have pledged carbon neutrality within this decade; however, AI has significantly challenged these goals. Google reported a 48% increase in emissions over the past five years, attributing most of the rise to AI-driven energy use [20]. Microsoft executives likewise admit that carbon-negative goals may be unattainable on current timelines, given AI’s escalating energy requirements. This tension also extends to their supply chains: carbon-neutral targets require not only internal energy sourcing but also decarbonization of upstream suppliers and logistics partners, which remain energy-intensive [30].

Although electricity demand from data centers is projected to rise sharply, in the baseline trajectory this growth accounts for less than 10% of the global increase in electricity consumption between 2024 and 2030 [31]. By comparison, structural drivers such as industrial expansion, large-scale electrification, the rapid diffusion of electric vehicles, and the widespread uptake of air conditioning remain the dominant contributors to global demand growth. Yet, the relative scale of data centers should not obscure their systemic importance. Unlike electric vehicles, which are geographically dispersed across markets, data centers tend to cluster in specific regions, generating localised peaks in electricity demand that challenge grid stability and resource allocation. From a supply chain perspective, the spatial concentration of data centers amplifies logistical complexity. The deployment of high-performance servers, advanced cooling systems, and backup energy infrastructure requires finely tuned global supply chains capable of delivering specialised equipment on time and in sequence. Congestion in freight transportation, delays in the shipment of semiconductors, or bottlenecks in the construction materials sector can significantly slow down facility deployment, increasing the pressure on already strained local grids. Moreover, supply chains themselves are increasingly reliant on the digital services hosted in these data centers, meaning that disruptions in energy integration cascade into broader risks for logistics operations. Consequently, the challenge is not only to balance overall energy demand growth, but also to design resilient supply chain and logistics strategies that ensure efficient siting, construction, and operation of data centers in line with sustainable energy objectives.

Ultimately, the race for global leadership in AI and other frontier technologies may hinge less on algorithmic breakthroughs than on energy systems and supply chain resilience. The state capable of scaling reliable, low-carbon electricity production and integrating it efficiently into supply chains will likely gain long-term competitive advantage. China provides a striking case: by mid-2025 it surpassed 1 terawatt (TW) of installed solar PV capacity, adding nearly 93 GW in May alone, while continuing to expand wind and hydropower [14]. By coupling rapid AI deployment with aggressive renewable expansion and large-scale integration into logistics and energy supply chains, China is positioning itself to sustain AI growth without proportional increases in fossil fuel consumption. From this perspective, energy capacity and supply chain sustainability have become strategic levers of technological dominance. Countries that lag in expanding renewables, nuclear, or other clean baseload power—and fail to align energy flows with resilient supply chains—may find their AI ambitions constrained by energy bottlenecks. In contrast, those with forward-leaning energy transitions and logistics innovation may simultaneously advance digital competitiveness, climate objectives, and supply chain resilience.

4. Artificial Intelligence in Logistics: Energy Demand Versus Energy Efficiency

To complement the conceptual discussion, this section incorporates empirical case-based evidence illustrating how AI applications in logistics operations contribute to measurable energy savings and emission reductions. The following examples drawn from industry reports and peer-reviewed studies serve as practical demonstrations of AI’s impact across different supply chain segments.

The rapid diffusion of artificial intelligence in logistics processes reflects the broader tension between digital transformation and sustainability. This section directly addresses RQ1 by examining the extent to which AI technologies reduce energy consumption and emissions within core logistics operations such as transportation, warehousing, and port activities. Market forecasts underline the accelerating role of artificial intelligence in logistics and supply chain management. According to [32], the global market for AI in supply chains is projected to expand from approximately $5 billion in 2023 to more than $51 billion by 2030. This exponential growth is driven primarily by North America, which dominates the current market due to its advanced digital infrastructure and early adoption of AI-powered logistics systems. The Asia-Pacific region, however, is expected to experience the fastest growth, reflecting both the scale of regional logistics networks and increasing investments in AI to overcome infrastructure bottlenecks and rising energy costs. Europe shows steady but more moderate expansion, largely shaped by stringent environmental regulations and policies that prioritize energy efficiency and emissions reduction. Meanwhile, Latin America and MEA (Middle East, Africa) contribute smaller shares but are gradually integrating AI, particularly in port logistics and resource-intensive transport sectors.

From the perspective of energy demand versus energy efficiency, these regional trends suggest differentiated challenges. North America and Asia-Pacific may face the greatest risks of rising energy consumption due to large-scale deployments of AI-driven automation, while Europe’s regulatory landscape could help balance energy demand with sustainability imperatives. In all cases, the projected market expansion reinforces the duality of AI in logistics: as adoption grows, energy requirements will inevitably rise, yet so will the opportunities to leverage AI for route optimization, predictive maintenance, and intelligent energy management systems that collectively reduce emissions and operational inefficiencies [33].

4.1. Micro-Level Energy Efficiency in Logistics Operations

AI applications in transportation have proven to be among the most mature and quantifiable in terms of energy impact. Predictive routing and dynamic fleet scheduling allow logistics providers to minimize empty runs and fuel consumption. The well-documented UPS ORION platform reduced driving distances by more than 160 million km annually, saving over 10 million gallons of fuel and cutting CO2 emissions by approximately 100,000 tons per year [16]. Similar algorithms integrated into transport-management systems achieve 15–20% fuel savings and up to 30% reductions in fleet-related emissions [33]. Moreover, AI-supported electrification scheduling enables optimal battery charging during low-tariff periods, improving the energy efficiency of electric truck fleets.

In warehousing, AI enables continuous monitoring of temperature, humidity, and equipment performance through IoT sensors and machine-learning-based control of HVAC systems. Studies show that predictive HVAC algorithms can cut electricity use in logistics facilities by 20–25%, while AI-driven robotic systems improve throughput and lower idle power losses [32]. By dynamically adjusting lighting and material-handling operations, AI transforms warehouses from static energy consumers into adaptive, data-responsive facilities.

Port and terminal operations also demonstrate measurable energy improvements. Predictive maintenance of quay cranes and smart scheduling of container handling have been shown to lower energy use by 15% per load cycle and to reduce peak power demand during congestion periods [34]. Digital twins of port energy systems support real-time balancing between on-site renewable generation and electricity use, enhancing both operational continuity and energy resilience. Examples of AI applications and their energy impacts in logistics operations are showed in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of AI applications and their energy impacts in logistics operations.

At the aggregate level, these micro-scale savings translate into significant macro-scale benefits. According to estimates by the London School of Economics and Carbon Credits [32], AI-enabled optimization could reduce global logistics-related emissions by 10–15%, equivalent to 3.2–5.4 billion tons of CO2 by 2035. Importantly, these results highlight that energy efficiency gains stem not only from automation but from adaptive intelligence—AI systems continuously learning from operational data to align resource use with real-time conditions. Despite the rising electricity demand linked to AI, sector-level studies emphasize that logistics applications generate efficiency dividends surpassing consumption costs. Analyses by the London School of Economics and Carbon Credits [32] estimate that AI could cut global emissions annually by 3.2–5.4 billion tons of CO2 by 2035, particularly in logistics and transport. In freight logistics alone, AI-driven measures such as route optimization, improved load factors, and modal shifts can reduce emissions by 10–15% [33].

Overall, AI contributes to measurable reductions in energy use and emissions across logistics activities, confirming that—despite its digital energy costs—it can serve as a net-positive mechanism for energy efficiency within supply chains, thereby addressing RQ1 and setting the foundation for the subsequent analysis of systemic resilience (RQ2).

4.2. Systemic Implications, Trade-Offs, and Pathways Toward Energy-Resilient Supply Chains

While AI contributes to measurable micro-level energy savings across logistics operations, its widespread adoption also triggers system-wide trade-offs that reshape the energy dynamics of global supply chains. These broader implications go beyond individual warehouses or transport routes, extending to the digital and physical infrastructures that sustain AI-driven logistics. In this respect, RQ2 focuses on the technological, infrastructural, and organizational mechanisms that ensure the energy sustainability and systemic resilience of such transformations. The systemic perspective highlights that energy efficiency at the operational level cannot be sustained without resilient supporting systems—stable power grids, optimized data-center architectures, adaptive algorithms, and renewable-energy integration within logistics networks. The remainder of this section therefore examines how AI affects the overall energy equilibrium of supply chains, the efficiency–demand paradox of large-scale digitalization, and the pathways through which innovation in hardware, algorithms, and infrastructure can enhance long-term resilience.

4.2.1. Energy Efficiency Opportunities of AI in Logistics

The logistics sector, encompassing warehousing, transportation, and supply chain management, is among the most energy-intensive areas of the global economy. Artificial intelligence (AI) offers significant potential to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, provided that new technologies and optimization strategies are deployed in parallel. Recent analyses, such as those by Boston Consulting Group [33], estimate that AI applications could lower global emissions by 5–10% by 2030 through improved efficiency in industrial processes, energy use, and resource allocation. Nevertheless, critical voices warn that the AI supply chain—from chip production to lithium demand—may impose additional climate and resource pressures. This underscores the necessity of integrating AI adoption with systemic energy strategies, including renewable sourcing, energy-efficient algorithms, and demand-side management [32]. While AI technologies in logistics inevitably raise baseline energy consumption, their transformative potential lies in enabling more intelligent and adaptive energy use. Organizations that balance these dualities-leveraging AI to reduce inefficiencies while mitigating its inherent energy footprint-will secure strategic advantage in the era of decarbonization and digitalization.

4.2.2. Hardware Efficiency and Data Center Optimization

One critical pathway for energy reduction lies in the development of more efficient hardware architectures. Specialized accelerators, three-dimensional integrated circuits, and advanced cooling systems are designed to deliver higher performance per watt. For example, NVIDIA has reported that its next-generation superchips can achieve up to a thirty-fold increase in performance for generative AI workloads while consuming up to twenty-five times less energy compared to current-generation hardware [35]. Such advances allow for substantial reductions in the energy intensity of computation, particularly in data centers that serve as the backbone of AI-driven logistics operations. At the infrastructure level, data centers are increasingly designed with energy efficiency in mind. Techniques such as liquid cooling, dynamic workload allocation, and geographical siting near renewable energy sources allow operators to match computational demand with periods of low-cost and low-carbon electricity [36]. Moreover, ensuring that facilities operate on a 24/7 renewable basis enhances both energy stability and sustainability, directly contributing to reduced emissions in logistics networks.

4.2.3. Model Size Rationalization

Energy efficiency can also be achieved by rationalizing the use of AI models. Not all logistics tasks require large language models (LLMs) with hundreds of billions of parameters. In many cases, small language models (SLMs), with only millions or a few billion parameters, are sufficient. These models require far fewer computational resources, can be deployed on smaller edge devices, and offer significant reductions in energy consumption [37]. For instance, in predictive maintenance or demand forecasting in logistics, compact models can deliver high performance while minimizing energy overhead.

4.2.4. AI-Driven Energy Optimization

AI is also directly applied to energy management in logistics systems. The International Energy Agency notes that AI already supports more than fifty applications in the energy sector, ranging from load balancing to demand prediction, with the global market for AI-enabled energy management technologies projected to reach USD 13 billion in the coming years [25]. Smart meters and digital twins enhance grid visibility by generating orders of magnitude more data than traditional devices, enabling optimized distribution and integration of renewable energy sources. Within logistics, this translates into smarter routing, fleet management, and warehouse operations with reduced energy intensity [38]. By integrating these technological, infrastructural, and algorithmic innovations, AI can play a dual role in logistics: not only as a driver of automation and efficiency, but also as a catalyst for systemic reductions in energy consumption and emissions.

4.2.5. Smart Cooling and Environmental Control in Data Centers

A highly technical area where AI contributes to energy reduction is the optimization of cooling and thermal management in data centers. Machine learning models can forecast server workloads and local temperature variations, allowing cooling systems to adjust dynamically rather than operating at constant capacity. By applying predictive control, AI avoids overcooling and ensures that only high-load zones receive additional cooling, which minimizes overall energy consumption. Recent industrial deployments of AI-enabled cooling systems, such as Huawei’s iCooling@AI platform, have reported reductions in Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) of 8–15%, demonstrating the effectiveness of predictive models in large-scale computing facilities [39]. These techniques are particularly relevant in logistics environments where cloud-based AI platforms and digital twins play an increasing role in supply chain management, and where the supporting data center infrastructure has become a major driver of energy demand.

4.2.6. Network Infrastructure and Core System Optimization

Another technically advanced application lies in the use of AI for energy optimization in telecommunications and network infrastructure, which indirectly supports logistics platforms that rely on real-time connectivity. AI models can predict traffic patterns and adjust the operation of network nodes, base stations, and routing systems in real time. By placing certain network cells into low-power or sleep modes during periods of low demand, AI reduces unnecessary energy expenditure without compromising service quality. Large-scale implementations, have demonstrated potential energy reductions of up to 30–40% in mobile network operations [40]. Similarly, AI-driven optimizations in 5G core networks have achieved 7–15% energy savings by dynamically adapting routing and user plane functions. Since modern logistics systems increasingly depend on continuous communication between vehicles, warehouses, and management hubs, such reductions in network energy demand represent an important technical contribution to sustainability.

AI deployment in logistics produces a dual effect: while operational applications demonstrably reduce energy intensity, the cumulative energy demand of digital infrastructures can offset or even exceed these gains unless counterbalanced by systemic optimization. The emerging challenge is therefore not only to make AI “smarter” in logistics processes but also to make the energy systems supporting AI smarter and more resilient.

The evidence reviewed here suggests that three mechanisms are decisive for achieving this balance:

- (1)

- technological efficiency improvements in computation and cooling;

- (2)

- infrastructural adaptation through renewable integration and distributed energy systems; and

- (3)

- organizational governance linking digital transformation with sustainability objectives.

When these elements operate in synergy, AI evolves from an energy-intensive technology into a stabilizing force that enhances supply-chain resilience to energy shocks, price volatility, and climate disruptions.

5. Alternative Pathways of Electricity Demand in AI-Driven Supply Chains

Projections of global electricity demand from data centers reveal diverging pathways that depend on the pace of AI adoption, progress in energy efficiency, and the resilience of supply chains. In scenarios of accelerated AI uptake, resilient logistics networks and flexible supply chain configurations enable rapid expansion of data center capacity by facilitating the delivery of advanced hardware, cooling systems, and renewable energy integration. Under these conditions, global data center demand could surpass 1700 TWh [41] by 2035—around 45% above the baseline—and represent over 4% of total electricity use (Table 5). Such growth would place significant stress on both energy markets and the logistical systems required to sustain large-scale deployment, including the transport of critical minerals, high-performance semiconductors, and specialised infrastructure modules.

Table 5.

Global data center electricity consumption by sensitivity case, 2020–2035.

An alternative trajectory assumes that comparable demand for digital services can be met through substantial improvements in efficiency at the software, hardware, and infrastructure levels. When supply chains are capable of coordinating the timely sourcing and distribution of next-generation chips, modular data center components, and energy-efficient cooling solutions, overall energy use can be contained. In this case, data center demand in 2035 would remain closer to 970 TWh, accounting for only 2.6% of global consumption, while generating energy savings above 15% relative to the baseline. The logistics sector plays a decisive role in this outcome: smoother freight flows, standardized warehousing practices, and optimised multimodal transport reduce costs and ensure that technological advances diffuse rapidly and evenly across regions. A more constrained future emerges when supply chains experience bottlenecks in critical segments—such as limited semiconductor availability, congestion in global shipping, or delays in renewable energy integration. These frictions can slow down the deployment of new facilities and restrict the scale of AI adoption. Although efficiency improvements would still compensate for some of the demand, total electricity use by data centers would plateau around 700 TWh in 2035, limiting their share of global demand to below 2%. While this alleviates some energy pressures, it also curtails the broader potential of AI to optimise logistics and enhance systemic resilience. These outlooks demonstrate that the trajectory of AI-driven electricity demand cannot be explained solely by technological factors. It is equally shaped by the efficiency, adaptability, and resilience of global supply chains, which determine how rapidly energy-intensive infrastructures are built, distributed, and maintained. In other words, the race to balance digital expansion with sustainable energy use is as much a matter of logistics coordination as it is of energy policy or innovation.

6. Scenario Simulation Framework

This study proposes a quantitative simulation framework to examine how the large-scale adoption of AI in logistics affects total energy demand, carbon emissions, and systemic resilience. To complement the conceptual analysis, a scenario-based simulation will be implemented in Python PyCharm 2024.3.1.1, combining elements of system dynamics (SD) and agent-based modeling (ABM). The Python environment helps reproducible modeling of complex interdependencies between data-center energy demand, AI-driven operational efficiency, and renewable energy integration within supply chains. The initial prototype is developed as a time-stepped model (2024–2035). The model architecture captures both macro-level energy flows and micro-level behavioral dynamics.

At the macro level, the SD layer represents energy generation, renewable-share evolution, data-center electricity demand, and emission factors across regions. At the micro level, the ABM/DE layer represents logistics agents—trucking fleets, warehouses, cold-chain facilities, ports, and data centers—each responding to AI-driven optimization, cost signals, and policy incentives. This dual perspective allows the analysis of feedback loops from energy price through AI utilization to emissions and the heterogeneity of firm-level adoption patterns. Core modules include:

- (1)

- Energy supply and grid mix (TWh, share of renewables, reserve margin, prices),

- (2)

- Data-center infrastructure (AI workload share, Power Usage Effectiveness—PUE, energy per inference),

- (3)

- Transportation (energy consumption and fuel savings from predictive routing),

- (4)

- Warehousing (HVAC control, robotics efficiency),

- (5)

- Ports and terminals (energy per handling cycle, predictive maintenance),

- (6)

- Governance and policy mechanisms (renewable integration targets, dynamic pricing).

Baseline data and calibration values are drawn from the IEA Energy [25], which estimates total data-center electricity use at 415–460 TWh in 2024 and approximately 945 TWh by 2030. Goldman Sachs Research [24] projects AI-related data-center demand to increase by 160–165% through 2030. The model also incorporates empirical efficiency benchmarks from (predictive routing saving ≈10 million gallons of fuel and ≈100,000 t CO2 annually) and cooling systems, which report 8–15% PUE improvements in operational deployments (Huawei, 2024 [39]). Scenarios are defined as follows:

- −

- Scenario A—Baseline/Low-AI adoption

- Represents gradual digitalization of logistics. AI is adopted primarily in pilot-scale route optimization and warehouse automation. Data-center energy demand grows modestly in line with historical trends (+10% by 2035). Energy savings from AI applications are visible but limited to niche operations.

- −

- Scenario B—High-AI adoption with conventional grid

- Describes rapid scaling of AI systems in logistics—autonomous dispatch, predictive maintenance, and large-scale optimization—without parallel investment in renewable energy or efficiency. Data-center electricity use follows the Goldman Sachs projection of +160% growth by 2030. PUE improvements are minimal (≈5%), resulting in the sharpest increase in both total energy and CO2 emissions.

- −

- Scenario C—High-AI adoption with green integration

- Illustrates an accelerated digital transformation synchronized with renewable integration and advanced energy-management technologies. Smart cooling improves PUE by 8–15%, and renewable energy reaches 60% of total supply by 2035. Small and medium AI models are deployed for routine operations to minimize computational load. This scenario tests whether system-level optimization can offset the energy intensity of AI.

- −

- Scenario D—Bottlenecked adoption

- Captures conditions of constrained supply chains—limited semiconductor availability, delayed data-center construction, and insufficient cooling infrastructure. AI deployment progresses slowly (≈35% by 2035), reducing both efficiency gains and additional energy demand.

The simulation computes annual energy demand (E_total [TWh]) and emissions (CO2_total [Mt CO2]). Calibration aligns 2024 values with IEA and corporate data, while sensitivity analyses (Monte Carlo) test uncertainties of ±25% in operational savings and ±30% in data-center energy intensity. Scenario C is expected to yield a net-positive balance—higher AI utilization but lower overall emissions—consistent with projections from BCG [34] and Carbon Credits [32], which estimate global CO2-reduction potentials of 2.6–5.3 Gt through AI-enabled optimization. The Python-based simulation thus operationalizes the conceptual duality of AI as both an energy consumer and efficiency enabler, transforming theoretical insights into quantifiable trajectories of sustainability and resilience in global supply chains.

The simulation links the energy and emission impacts of AI adoption through simplified balance equations representing four major components: data centers, AI computation, transport, and warehousing.

Data-center demand grows according to the IEA baseline (460 TWh in 2024) and scenario-specific growth multipliers:

where reflects cumulative infrastructure growth (e.g., 2.6× for Scenario B) and decreases proportionally to smart-cooling efficiency (5–15%).

AI inference energy is approximated by:

where is the annual number of queries, the energy per query (2.9–18 Wh per inference), and the share of AI adoption over time.

Transport and warehouse energy decrease linearly with AI adoption due to optimization and predictive control:

with savings coefficients (10% fuel reduction) and (22% HVAC saving), calibrated from UPS ORION and predictive HVAC benchmarks. Total annual emissions are obtained by multiplying total energy consumption by regional emission factors:

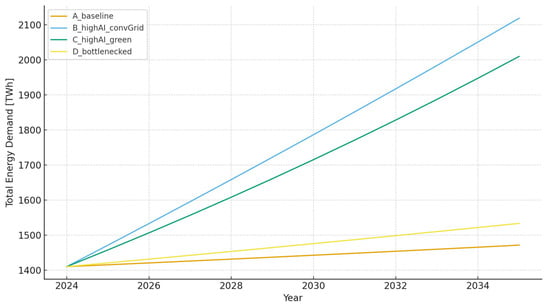

where denotes annual total electricity demand in terawatt-hours (TWh) and represents the carbon intensity of the energy mix (kg CO2/kWh). The multiplication yields total annual emissions in megatonnes of CO2 (Mt CO2). The emission factor declines proportionally to the renewable share in each scenario. The model uses a global average of 0.45 kg CO2/kWh as a starting point. All equations are implemented in Python as a deterministic year-by-year computation. Parameters such as adoption rates, growth factors, and efficiency gains are linearly interpolated between 2024 and 2035. The framework allows rapid scenario testing and sensitivity analysis by varying assumptions (e.g., AI adoption speed, PUE improvement, renewable share). This model deliberately abstracts from market prices and feedback loops to isolate physical and technological effects. While simplified, it provides a transparent structure for further refinement—linking AI scaling, digital energy demand, and emission outcomes in a quantifiable manner. Total energy demand and carbon emissions evolve differently across the four simulated scenarios (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The results quantify how the interaction between AI deployment intensity, energy efficiency, and renewable integration shapes overall system performance in logistics.

Figure 2.

Total energy demand—scenario prediction.

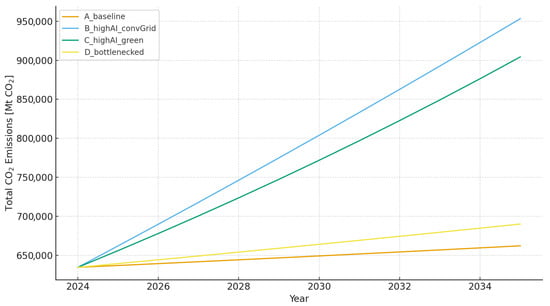

Figure 3.

Total carbon emissions—scenario prediction.

Figure 2 shows that total energy demand increases under all pathways, but the slope and curvature differ markedly. Figure 3 mirrors these dynamics for emissions. Scenarios A and D follow relatively stable CO2 trajectories, while Scenario B generates the highest cumulative emissions—an outcome of high data-center load combined with fossil-dominated power. In contrast, Scenario C demonstrates the potential for decoupling digital expansion from emission growth, yielding a substantially flatter CO2 curve as renewable generation and AI-based optimization reduce the effective emission factor.

Overall, the results confirm two key insights. First, AI-driven efficiency at the operational level does not guarantee lower total energy use: large-scale data-center growth can outweigh localized savings if grid decarbonization lags behind. Second, integration of AI with renewable energy and efficiency technologies—as represented in Scenario C—is essential to ensure a net-positive environmental balance. This scenario illustrates that the twin goals of digital innovation and sustainability are compatible only when pursued jointly. The simulated trajectories thus translate the conceptual argument of the paper into empirical form: AI constitutes both a consumer and an enabler of energy efficiency, and its long-term impact depends on the systemic coordination between technological progress, energy policy, and infrastructure investment.

7. Limitations, Conclusions, and Future Work

The present study is subject to several important limitations that must be acknowledged. It is based primarily on secondary data, which restricts the possibility of direct empirical verification of the conclusions drawn. A further constraint lies in the absence of primary investigations and the limited availability of comprehensive, harmonized information on actual energy consumption across supply chains. Given that supply chains differ considerably in structure, scale, and scope of interconnections, conducting an exhaustive assessment of their energy use remains highly complex. Consequently, the findings presented here should be understood as largely prognostic, grounded in the existing literature, and intended as a foundation for subsequent scientific exploration. Moreover, the global perspective adopted in this study does not capture local and regional conditions, which may differ significantly due to contextual specificities and, in turn, shape the energy efficiency of implemented solutions. The results should therefore be interpreted as conceptual and exploratory, with their full validation requiring further empirical research encompassing diverse sectors, regions, and longer time horizons.

The analysis underscores the critical role of artificial intelligence in logistics processes and supply chain management in the context of the energy transition. The findings suggest that AI can substantially contribute to reducing energy consumption and limiting emissions, yet it simultaneously generates additional energy demand stemming from the operation of digital infrastructure and data centers. This phenomenon illustrates the dual nature of digitalization: while it streamlines processes and reduces inefficiencies, it may also amplify environmental burdens. The study further highlights that organizations implementing intelligent energy-balancing mechanisms achieve enhanced systemic resilience and competitive advantage. Importantly, AI technologies do not automatically guarantee improvements in efficiency unless accompanied by parallel deployment of renewable energy solutions.

Another notable observation concerns the pronounced regional disparities that determine the pace and scope of AI adoption in logistics. In developed economies, environmental regulations and societal pressures accelerate the integration of environmentally friendly solutions, whereas in developing contexts the key limiting factor remains the availability of energy infrastructure. The findings therefore suggest that, without coherent policy frameworks and adequate investments in clean energy, the growth of AI applications may reinforce high-emission trajectories. Of particular importance is the recognition that the energy efficiency of AI depends on the choice of algorithms, the optimization of computational capacity, and integration with real-time energy management systems. In this regard, predictive models and digital twin technologies assume a strategic role in reducing energy losses—an element that may prove decisive for future success.

It is also worth emphasizing that artificial intelligence contributes not only to operational efficiency but also to the resilience of logistics systems in the face of energy-related disruptions. By enabling the forecasting of energy demand and prices, AI allows organizations to better prepare for market fluctuations and volatility. Equally important, however, is the recognition that the successful implementation of AI requires parallel organizational and competency-related transformations. This underscores the necessity of developing new models of human resource management that align technological adoption with workforce adaptation and capacity building [43]. It is also essential that the effectiveness of AI implementation be assessed not only in economic terms but also through environmental and social dimensions [42]. The present article aligns with the ongoing discourse on sustainable development and highlights the necessity of fostering synergies between digital technologies and climate policy [44,45]. Nevertheless, a research gap has been identified regarding empirical analyses of AI implementation in logistics, which constrains the ability to unambiguously determine long-term outcomes. Further work is required to develop more precise methodologies for assessing the impact of AI on pollutant emissions, including a full life-cycle perspective of digital infrastructure. In light of the findings, it can be argued that AI holds significant potential to become a key instrument in supporting decarbonization processes; however, this potential can only be realized if accompanied by a parallel energy transition and the deployment of renewable energy sources. Forecasting algorithms for energy demand and prices can support enterprises in adapting to fluctuations in costs and resource availability. At the same time, the implementation of AI necessitates organizational changes and the development of new employee competencies, highlighting the need for an integrated approach that encompasses not only technological but also managerial and social dimensions. The effectiveness of AI implementation should therefore be assessed in a multidimensional manner, incorporating economic, environmental, and social criteria [46]. The discussion also underscores the role of artificial intelligence in enhancing the resilience of logistics systems to energy and market disruptions. Forecasting algorithms for energy demand and prices can aid enterprises in adapting to fluctuations in both cost and resource availability [47]. Simultaneously, the deployment of AI requires organizational adjustments and the cultivation of new workforce skills, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach that addresses technological, managerial, and societal factors [48,49]. Consequently, the effectiveness of AI adoption must be evaluated through multidimensional frameworks that integrate economic, environmental, and social dimensions [50].

The conducted research further confirms the critical role of artificial intelligence in logistics processes and supply chain management, particularly within the context of the energy transition and growing sustainability requirements. The results indicate that AI can significantly reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [51], while simultaneously generating additional energy demand due to the operation of digital infrastructure and data centers [52]. This duality illustrates the paradoxical nature of digitalization: while enhancing efficiency and reducing operational losses, it also introduces new environmental burdens [53,54]. A key factor determining the success of AI deployment lies in the capacity of organizations to intelligently balance energy consumption while simultaneously integrating renewable sources [55]. Only under such conditions can AI technologies generate lasting competitive advantage and strengthen the systemic resilience of supply chains.

The findings also reveal pronounced regional heterogeneity in AI adoption. In developed economies, regulatory frameworks and societal pressures accelerate the integration of environmentally oriented technologies [55,56,57,58], whereas in developing economies, barriers are predominantly associated with limited energy infrastructure and investment capacity [59]. Within this context, AI does not guarantee automatic improvements in energy efficiency; its success depends on coordinated energy and climate policies as well as investments in clean energy [60]. Of particular relevance are predictive models and digital twin technologies, which enable real-time optimization by reducing energy losses and enhancing operational flexibility [61].

In conclusion, the presented analysis contributes to the ongoing discourse on sustainable development and demonstrates that AI holds substantial potential to serve as a key instrument for decarbonization. However, this potential can only be realized if AI adoption is accompanied by parallel energy transition strategies and the use of renewable resources. The study also points to the need for further empirical research to evaluate the long-term effects of AI deployment across sectors and regions and to design more accurate methodologies for assessing its impacts on emissions and energy efficiency. The findings provide compelling evidence of the growing role of AI in shaping energy transition and enhancing the efficiency of logistics processes. The analysis suggests that while AI can contribute significantly to reducing energy use and emissions, these benefits are not automatic and depend on contextual factors, including energy mix and digital infrastructure quality. The results highlight the dual nature of digitalization: technologies that streamline operations and reduce inefficiencies may simultaneously generate additional environmental burdens through higher energy demand. This ambivalence underscores the importance of sustainable strategies that align AI adoption with broader energy transition objectives.

Ultimately, the study confirms that AI’s effectiveness in supporting decarbonization depends on the integration of renewable energy, predictive models, and advanced digital solutions such as digital twins. Developed economies appear to be progressing faster due to regulatory and societal pressures, whereas developing economies face constraints linked to infrastructure and financing. This regional divergence implies that the global impacts of AI adoption will remain heterogeneous. Future research should focus on empirical analyses that incorporate sectoral and regional specificities, assess long-term sustainability outcomes, and include full life-cycle assessments of AI-driven infrastructures. Only through such multidimensional and holistic evaluations can AI’s role in building resilient, low-carbon, and sustainable logistics systems be fully understood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T. and T.W.; methodology, B.T. and T.W.; validation, B.T. and T.W.; formal analysis, B.T. and T.W.; investigation, B.T. and T.W.; resources, B.T. and T.W.; data curation, B.T. and T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T. and T.W.; writing—review and editing, B.T. and T.W.; visualization, B.T. and T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the Minister of Science (Poland) under the “Regional Excellence Initiative”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hmouda, A.M.; Orzes, G.; Sauer, P.C. Sustainable supply chain management in energy production: A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, Z.; Musilek, P. Impact of digital transformation on the energy sector: A review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raygoza-Limón, M.E.; Orduño-Osuna, J.H.; Trujillo-Hernández, G.; Bravo-Zanoguera, M.E.; Amezquita Garcia, J.A.; Ramírez-Hernández, L.R.; Flores-Fuentes, W.; Antúnez-García, J.; Murrieta-Rico, F.N. Supply Chain Management in Renewable Energy Projects from a Life Cycle Perspective: A Review. Appl. Sci. (2076-3417) 2025, 15, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Electricity 2025: Analysis and Forecast to 2027. 2025. International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2025 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- McKinsey & Company. The Net-Zero Transition: What it Would Cost, What it Could Bring. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/the-net-zero-transition-what-it-would-cost-what-it-could-bring (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q. Digitalization, electricity consumption and carbon emissions—Evidence from manufacturing industries in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Men, Y.; Fuster, N.; Osorio, C.; Juan, A. A Artificial intelligence in logistics optimization with sustainable criteria: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfaqih, H. Artificial intelligence in logistics and supply chain management: A perspective on research trends and challenges. In International Conference on Business and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1241–1247. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, A. The growing energy footprint of artificial intelligence. Joule 2023, 7, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, B.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Y. Supply chain digitalization, green technology innovation and corporate energy efficiency. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiūnas, J.; Lund, P.D.; Mikkola, J. Energy system resilience–A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasa, O.P.; Phoya, S.; Monko, R.J.; Musonda, I. Integrating Sustainability and Resilience Objectives for Energy Decisions: A Systematic Review. Resources 2025, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Tang, Q.; Li, C.M.; Liu, J. Exploring the impact of digital transformation on productivity: The role of artificial intelligence technology, green technology, and energy technology. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2025, 31, 1499–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, V. China Hits 1 TW Solar Milestone, PV Magazine. 2025. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/06/23/china-hits-1-tw-solar-milestone/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Ed.) Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinnes, E.; Perez, F.; Kandel, M.; Probst, T. Decarbonizing Logistics: Charting the Path Ahead. 2024. McKinsey & Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/decarbonizing-logistics-charting-the-path-ahead (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bankoti, N.; Nagpal, C.; Shiledar, S. Spearheading Efficiency and Sustainability in Global Supply Chains. 2024. Available online: https://rmi.org/spearheading-efficiency-and-sustainability-in-global-supply-chains (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Olivari, E.; Caballini, C.; Lluch, X. How to calculate GHG emissions in freight transport? A review of the main existing online tools. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 19, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global CO2 Emissions from Transport by Subsector, 2000–2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-co2-emissions-from-transport-by-subsector-2000-2030 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Hoffman. Big Tech’s Staggering Power Consumption: Calculating the Massive Electricity Bills Companies Pay Off with Ease. 2024. Available online: https://www.bestbrokers.com/stock-brokers/big-techs-staggering-power-consumption-calculating-the-massive-electricity-bills-companies-pay-off-with-ease/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Electricity Data Browser. U.S. Department of Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Krisknakumari, S. Artificial intelligence in enhancing operational efficiency in logistics and SCM. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Shekarabi, S.A.; Kiani Mavi, R.; Romero Macau, F. Supply Chain Resilience: A Critical Review of Risk Mitigation, Robust Optimisation, and Technological Solutions and Future Research Directions. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2025, 26, 681–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, W.; Chen, L. How does artificial intelligence affect energy efficiency? Evidence from supply chain digitization pilot program. Energy Econ. 2025, 149, 108728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Research on energy efficiency optimization strategies for E-commerce platform product supply chain based on artificial intelligence. Sustain. Energy Res. 2025, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman Sachs. AI is Poised to Drive 160% Increase in Data Center Power Demand. Goldman Sachs Research. 2023. Available online: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/AI-poised-to-drive-160-increase-in-power-demand (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Energy demand from AI. In Electricity 2023: Analysis and Forecast to 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/energy-demand-from-ai (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Masanet, E.; Shehabi, A.; Lei, N.; Smith, S.; Koomey, J. Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates. Science 2020, 367, 984–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mompó, A.; Mavromatis, I.; Li, P.; Katsaros, K.; Khan, A. Green MLOps to Green GenOps: An Empirical Study of Energy Consumption in Discriminative and Generative AI Operations. Information 2025, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Eid, F.; El-Sappagh, S.; Abuhmed, T. Sustainable energy management in the AI era: A comprehensive analysis of ML and DL approaches. Computing 2025, 107, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain Market (2024–2030). 2025. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-supply-chain-market-report (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Carbon Credits. Study Shows How AI can Cut Over 5 Billion Tons of Carbon Emissions in 3 Key Climate Sectors. 2025. Available online: https://carboncredits.com/study-shows-how-ai-can-cut-over-5-billion-tons-of-carbon-emissions-in-3-key-climate-sector (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Taft, M. AI Is Eating Data Center Power Demand—And It’s Only Getting Worse, Wired. 2025. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/new-research-energy-electricity-artificial-intelligence-ai/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Boston Consulting Group. How AI Can Be a Powerful Tool in the Fight Against Climate Change. 2022. Available online: https://web-assets.bcg.com/ff/d7/90b70d9f405fa2b67c8498ed39f3/ai-for-the-planet-bcg-report-july-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Nvidia. NVIDIA Introduces Blackwell GPU Architecture. 2024. Available online: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/data-center/technologies/blackwell-architecture/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Jalasri, M.; Panchal, S.M.; Mahalingam, K.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Hemalatha, R.; Boopathi, S. AI-Powered Smart Energy Management for Optimizing Energy Efficiency in High-Performance Computing Systems. In Future of Digital Technology and AI in Social Sectors; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 329–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rosamma, K.S. Small Language Models and Their Role in Hybrid AI Architectures for Big Data Analytics. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Sustainable Communication Networks and Application (ICSCNA), Theni, India, 11–13 December 2024; pp. 594–599. [Google Scholar]

- Onwusinkwue, S.; Osasona, F.; Ahmad, I.A.I.; Anyanwu, A.C.; Dawodu, S.O.; Obi, O.C.; Hamdan, A. Artificial intelligence (AI) in renewable energy: A review of predictive maintenance and energy optimization. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 2487–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huawei. iCooling@AI: Smart Cooling for Data Centers. 2024. Available online: https://www.huawei.com/en/huaweitech/publication/90/smart-cooling-data-centers (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Sankarananth, S.; Karthiga, M.; Bavirisetti, D.P. AI-enabled metaheuristic optimization for predictive management of renewable energy production in smart grids. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Increase in Electricity Demand by Sector, Base Case, 2024–2030; IEA: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Adewuyi, O.B.; Luwaca, E.; Ratshitanga, M.; Moodley, P. Artificial intelligence-based forecasting models for integrated energy system management planning: An exploration of the prospects for South Africa. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, N.; Arunachalam, H.; Pathi, B.K.; Gajenderan, V. The adoption of artificial intelligence in human resources management practices. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zuo, Z.; Han, J.; Zhang, W. Is digital-green synergy the future of carbon emission performance? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Can Functional Industrial Policy Promote Digital–Green Synergy Development? Sustainability 2025, 17, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, F.; Wagner, J.; Meyer, A.; Reinhard, P.; Voss, M.; Petschow, U.; Mollen, A. Broadening the perspective for sustainable AI: Comprehensive sustainability criteria and indicators for AI systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Energy cost forecasting and financial strategy optimization in smart grids via ensemble algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1353312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Islam, N.; Parida, V.; Singh, H.; Altwaijry, N. Artificial intelligence (AI) competencies for organizational performance: A B2B marketing capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Niu, L.; Chen, Z.; Fan, Y. How Organizational AI Adoption and Employee AI Skills Fit to Affect Organizational Performance. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Valhalla, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 2025, p. 12059. [Google Scholar]

- Toderas, M. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Critical Analysis of AI Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Lee, C.C.; Lev, B. Optimizing AI-based emission reduction efficiency and subsidies in supply chain management: A sensitivity-based approach with duopoly game dynamics. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 494, 144991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, T.; Holzapfel, P.; Stobbe, L.; Grimm, A.; Nissen, N.F.; Finkbeiner, M. Toward climate neutral data centers: Greenhouse gas inventory, scenarios, and strategies. iScience 2025, 28, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Tang, R.; Chen, N. Enterprise Digitalization and ESG Performance: Evidence from Interpretable AI Large Language Models. Systems 2025, 13, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Masurkar, S.; Pathade, G.R. An overview of digital transformation and environmental sustainability: Threats, opportunities, and solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, R. Integrating artificial intelligence in energy transition: A comprehensive review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 57, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Deng, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency under integrated governance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pricopoaia, O.; Cristache, N.; Lupașc, A.; Iancu, D. The implications of digital transformation and environmental innovation for sustainability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergroach, S.; Héritier, J. Emerging Divides in the Transition to Artificial Intelligence; OECD Regional Development Papers No. 147; OECD: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Javed, A. Artificial Intelligence Adoption and Role of Energy Structure, Infrastructure, Financial Inclusions, and Carbon Emissions: Quantile Analysis of E-7 Nations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]