Numerical Investigation on Mixture Formation and Injection Strategy Optimization in a Heavy-Duty PFI Methanol Engine

Abstract

1. Introduction

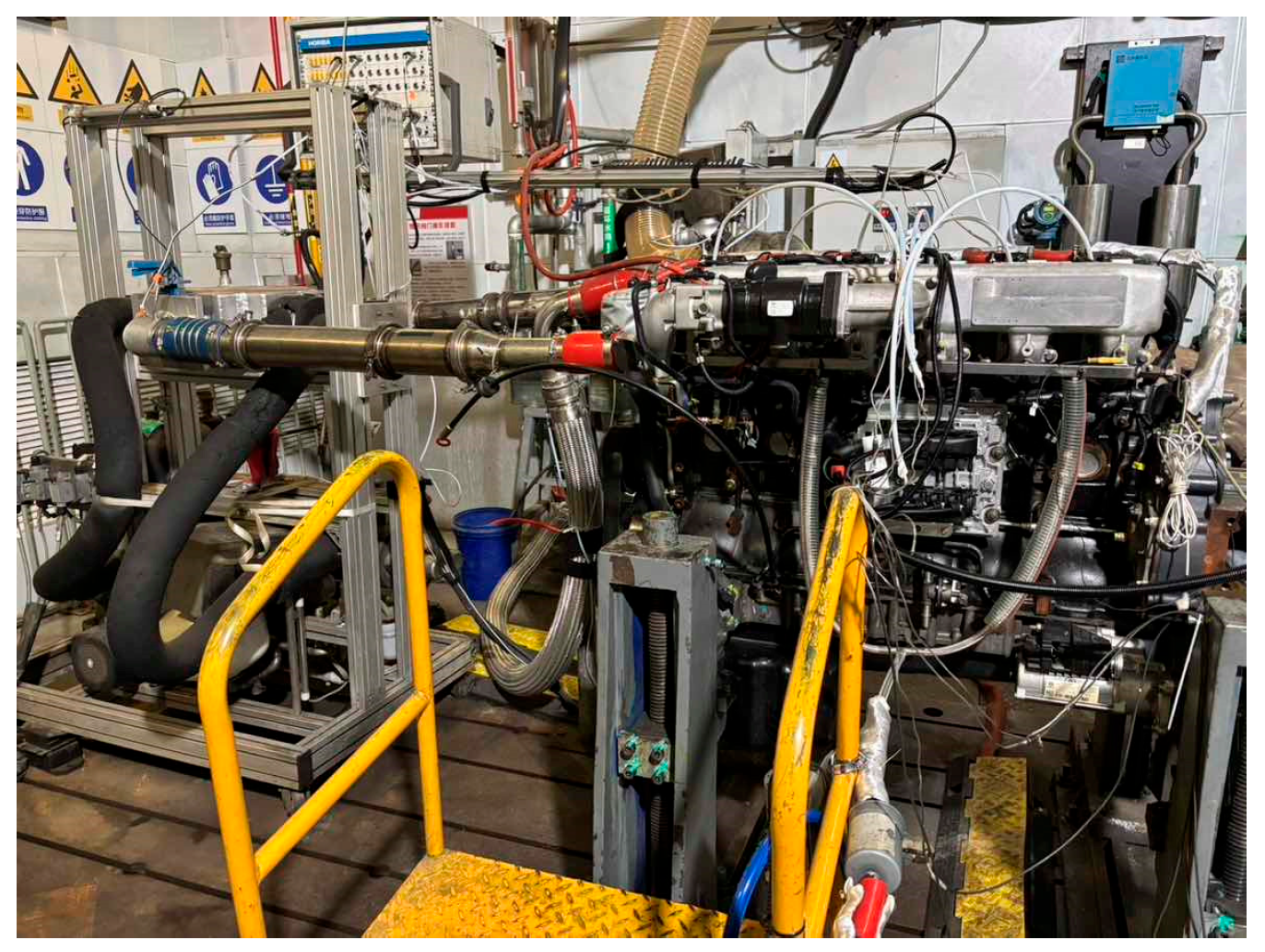

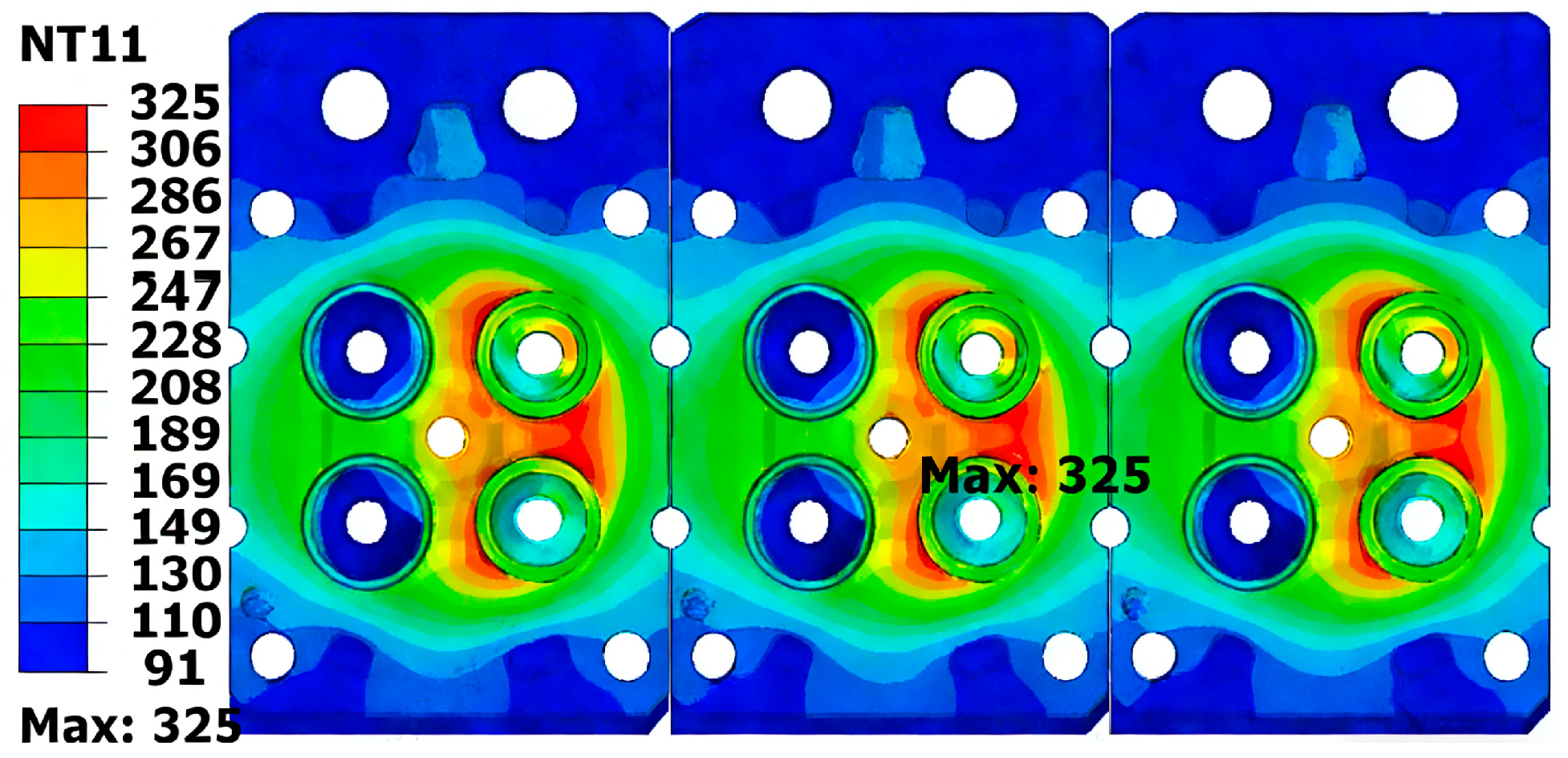

2. Methodology

3. Results

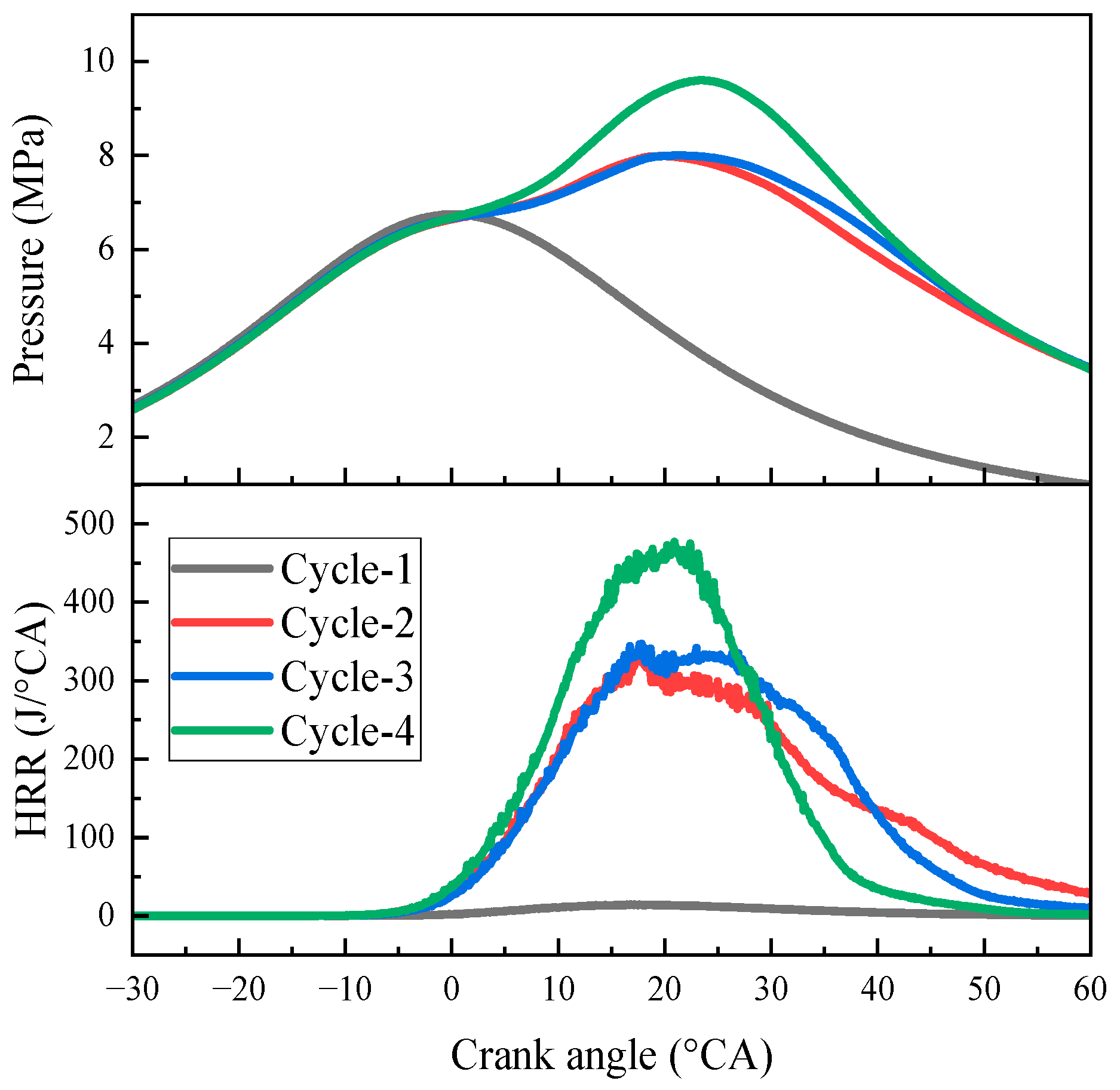

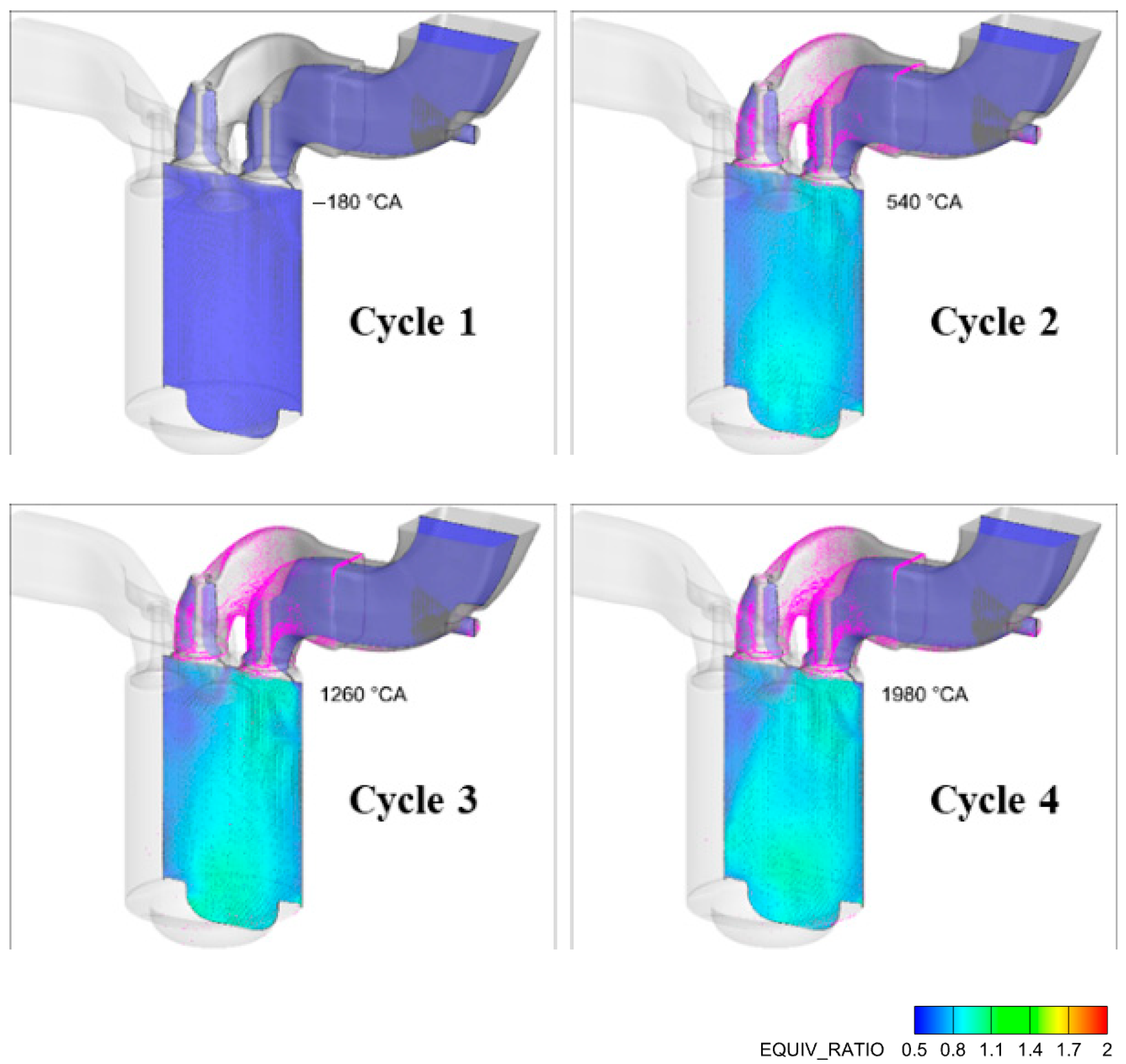

3.1. Multi-Cycle Numerical Simulation and Combustion Stabilization Process

3.2. Injection Phasing

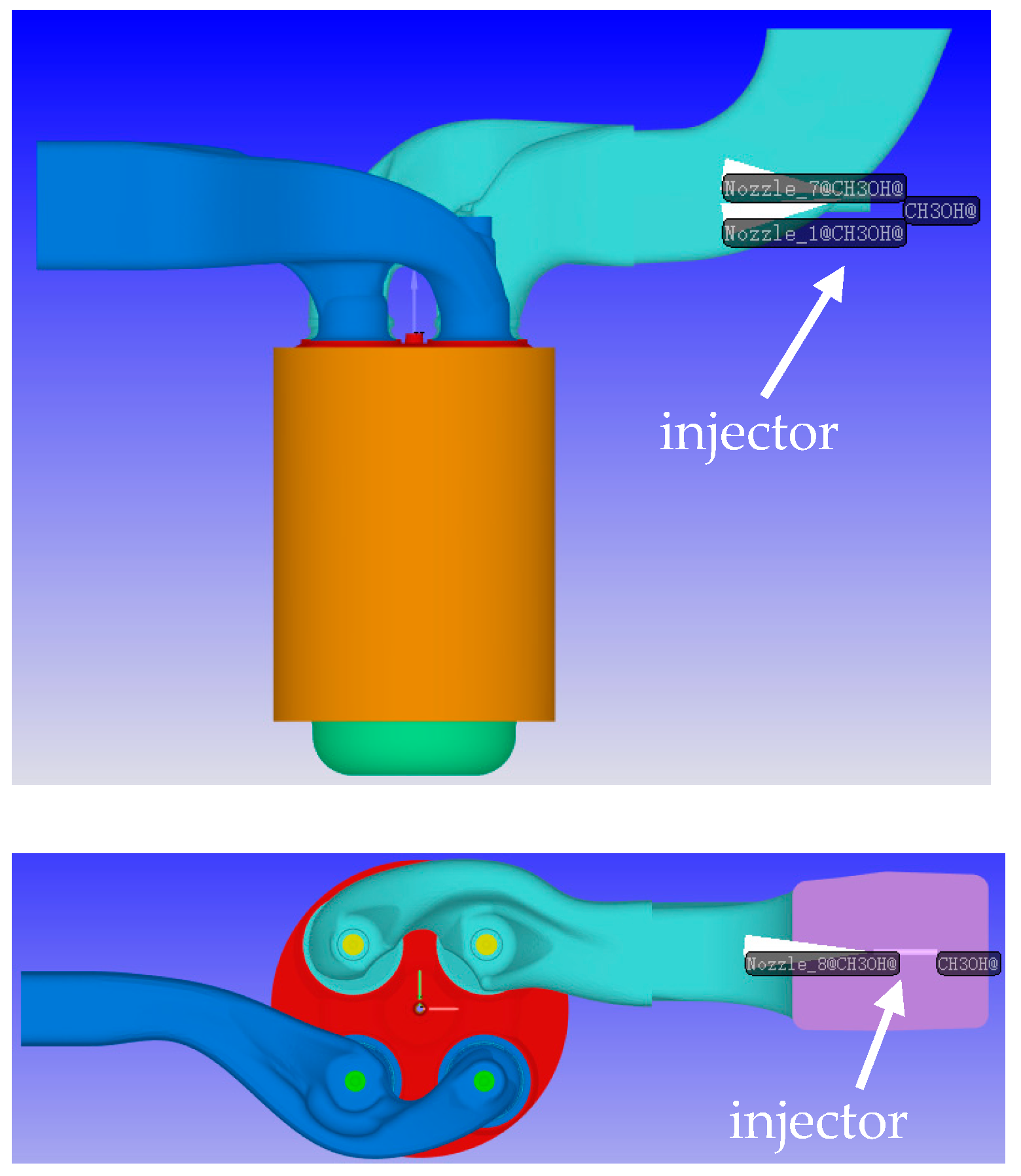

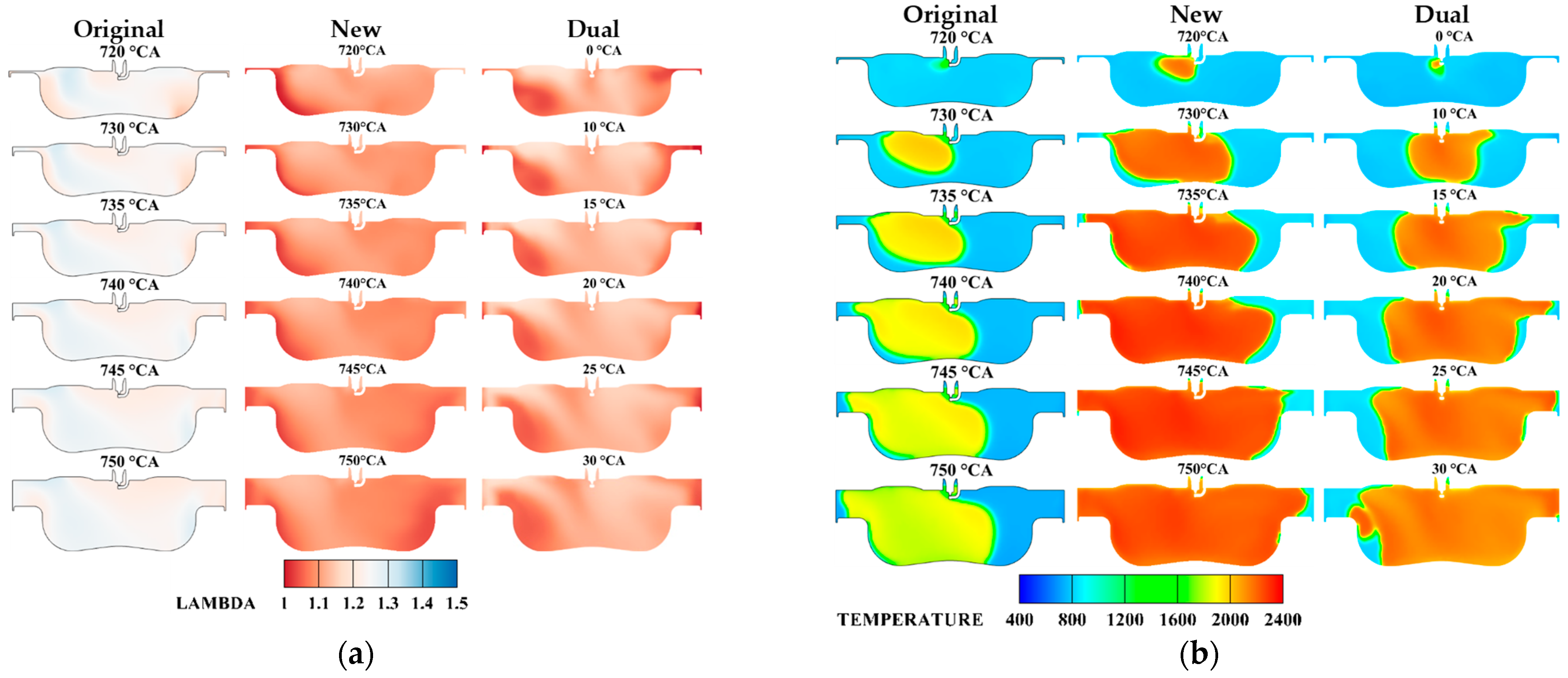

3.3. Injector Number and Position

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, X.; Liu, Z. The Effect of Methanol Production and Application in Internal Combustion Engines on Emissions in the Context of Carbon Neutrality: A Review. Fuel 2022, 320, 123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Turner, J.W.; Sileghem, L.; Vancoillie, J. Methanol as a Fuel for Internal Combustion Engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 70, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Wang, Y. An Overview of Methanol as an Internal Combustion Engine Fuel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Liu, F. Assessment of Ultra-Lean Burn Characteristics for a Stratified-Charge Direct-Injection Spark-Ignition Methanol Engine under Different High Compression Ratios. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güdden, A.; Pischinger, S.; Geiger, J.; Heuser, B.; Müther, M. An Experimental Study on Methanol as a Fuel in Large Bore High Speed Engine Applications–Port Fuel Injected Spark Ignited Combustion. Fuel 2021, 303, 121292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancoillie, J.; Sileghem, L.; Van De Ginste, M.; Demuynck, J.; Galle, J.; Verhelst, S. Experimental Evaluation of Lean-Burn and EGR as Load Control Strategies for Methanol Engines. In Proceedings of the SAE 2012 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–26 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhai, C.; Zeng, X.; Shi, K.; Wu, X.; Ma, T.; Qi, Y. Review of Pre-Ignition Research in Methanol Engines. Energies 2024, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayler, P.J.; Colechin, M.J.F.; Scarisbrick, A. Intra-Cycle Resolution of Heat Transfer to Fuel in the Intake Port of an S.I. Engine. In Proceedings of the 1996 SAE International Fall Fuels and Lubricants Meeting and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–17 October 1996; p. 961995. [Google Scholar]

- Servati, H.B.; Yuen, W.W. Deposition of Fuel Droplets in Horizontal Intake Manifolds and the Behavior of Fuel Film Flow on Its Walls. In Proceedings of the SAE International Congress and Exposition, Detroit, MI, USA, 27 February–2 March 1984; p. 840239. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Chang, W.; Shu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Yao, M. Experimental and Simulation Study on Reducing the Liquid Film and Improving the Performance of a Carbon-Neutral Methanol Engine. Energies 2025, 18, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Investigation on the Development Law of Methanol Spray Impinging on Intake Valve during Port Fuel Injection. Energy 2025, 320, 135250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Yao, C.; Liu, M.; Wu, T.; Wei, H.; Dou, Z. Study on Cyclic Variability of Dual Fuel Combustion in a Methanol Fumigated Diesel Engine. Fuel 2016, 164, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yao, C.; Yao, A.; Dou, Z.; Wang, B.; Wei, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Shi, J. The Impact of Methanol Injecting Position on Cylinder-to-Cylinder Variation in a Diesel Methanol Dual Fuel Engine. Fuel 2017, 191, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Tripathy, S.; Molander, P.; Dahlander, P. Effects of Port-Fuel Injected Methanol Distribution on Cylinder-to-Cylinder Variations in a Retrofitted Heavy-Duty Diesel–Methanol Dual Fuel Engine. Fuel 2025, 391, 134733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Jia, M.; Xie, M.; Lee, C.F. Three-Dimensional Numerical Investigation on Wall Film Formation and Evaporation in Port Fuel Injection Engines. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2016, 69, 1405–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, X. Mixture Formation Characteristics and Feasibility of Methanol as an Alternative Fuel for Gasoline in Port Fuel Injection Engines: Droplet Evaporation and Spray Visualization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, C.-M.; Su, Y.; Dou, H.-L.; Liu, X.-J. Effect of Injection and Ignition Timings on Performance and Emissions from a Spark-Ignition Engine Fueled with Methanol. Fuel 2010, 89, 3919–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Mu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Du, R.; Guan, W.; Liu, S. Cylinder-to-Cylinder Variation of Knock and Effects of Mixture Formation on Knock Tendency for a Heavy-Duty Spark Ignition Methanol Engine. Energy 2022, 254, 124197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Shi, Z.; Zeng, Z. Investigation on Injection Strategy Affecting the Mixture Formation and Combustion of a Heavy-Duty Spark-Ignition Methanol Engine. Fuel 2023, 334, 126680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Xing, Y. Effect of Injection Angle on Combustion and Emission Performance of Spark Ignition M100 Methanol Engine in Equivalent Combustion. Energy 2025, 324, 135876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Jing, H.; Shen, J. Numerical Investigation on the Influence of Injection Location and Injection Strategy on a High-Pressure Direct Injection Diesel/Methanol Dual-Fuel Engine. Energies 2023, 16, 4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Zuo, Q.; Wang, H.; Ning, D.; Kou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G. Combustion Characteristics and Performance Analysis of a Heavy-Fuel Rotary Engine by Designing Fuel Injection Position. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 247, 123021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Study on the Mechanism of Influence of Cetane Improver on Methanol Ignition. Fuel 2023, 354, 129383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bore | 131 mm |

| Stroke | 160 mm |

| Intake Valve Opening | −373° CA |

| Intake Valve Closing | −153° CA |

| Ignition Energy | 90 mJ |

| Compression Ratio | 12.5 |

| Excess Air Coefficient | 1 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| RT Model size constant | 0.1 |

| Rebound Weber number | 50 |

| Separation constant | 80 |

| Wall roughness | 2.6 × 10−4 m |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Speed | 1900 rpm |

| Intake pressure | 0.237 MPa |

| Intake temperature | 338.4 K |

| Fuel injection pressure | 0.5 MPa |

| Fuel injection duration | −310~203° CA |

| EGR ratio | 25% |

| Spark timing | −12.6° CA ATDC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dou, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhai, C.; Zeng, X.; Shi, K.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z. Numerical Investigation on Mixture Formation and Injection Strategy Optimization in a Heavy-Duty PFI Methanol Engine. Energies 2026, 19, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020304

Dou Z, Xu X, Zhai C, Zeng X, Shi K, Wu X, Liu Y, Qi Y, Wang Z. Numerical Investigation on Mixture Formation and Injection Strategy Optimization in a Heavy-Duty PFI Methanol Engine. Energies. 2026; 19(2):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020304

Chicago/Turabian StyleDou, Zhancheng, Xiaoting Xu, Changhui Zhai, Xiaoxiao Zeng, Kui Shi, Xinbo Wu, Yi Liu, Yunliang Qi, and Zhi Wang. 2026. "Numerical Investigation on Mixture Formation and Injection Strategy Optimization in a Heavy-Duty PFI Methanol Engine" Energies 19, no. 2: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020304

APA StyleDou, Z., Xu, X., Zhai, C., Zeng, X., Shi, K., Wu, X., Liu, Y., Qi, Y., & Wang, Z. (2026). Numerical Investigation on Mixture Formation and Injection Strategy Optimization in a Heavy-Duty PFI Methanol Engine. Energies, 19(2), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020304