Abstract

Field-oriented control (FOC) of induction motors (IMs) is used in railway rolling stock. In such control systems, a fixed frequency of the pulse-width modulation (PWM) inverter is used, which leads to an increase in power losses in the traction drive. To optimize power losses in the locomotive traction drive system, it is proposed to adapt the number of PWM inverter pulses to the frequency of the FOC speed controller, which is proportional to the locomotive speed. To solve this problem, conceptual foundations for adapting FOC to the locomotive speed have been developed, the key aspects of which are algorithms for adapting the PWM inverter frequency, the controller parameters and the parameters of the FOC speed controller frequency filters. The most significant results of the work are the methods for adjusting the maximum of the controllers of the basic FOC IM system, the filter structure and the inverter control scheme, adapted to the locomotive speed. The modeling results have shown the effectiveness of the proposed technical solutions. The proposed approach to developing FOC will allow minimizing the consumption of energy resources by the locomotive in the entire range of changes in its speed.

1. Introduction

The trend of increasing prices for energy resources imposes strict requirements on energy consumption [1,2,3,4]. One of the largest energy-consuming industries is transport, in particular, electric transport [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, saving electrical energy consumed by electric transport is an urgent task [9,10]. The largest part of the energy consumed by electric transport falls on the traction drive (TD). Research analysis shows that the directions for increasing the TD energy efficiency of electric rolling stock (ERS) are: compensation of higher current harmonics in TD circuits [11,12], use of on-board energy storage devices [13,14,15,16] and energy-efficient management of the TD system [17,18,19], implementation of intelligent TD control systems [20,21]. When using compensation devices, additional power elements are introduced into the TD [22,23,24,25]. The introduction of on-board energy storage also requires the introduction of additional power elements into the traction drive system, such as the storage devices themselves and converters, on which the energy exchange system between the storage device and the TD is organized [26,27,28].

Energy-efficient control, as well as intelligent control systems, do not require the inclusion of additional power elements into the TP system when they are implemented. This is explained by the fact that such algorithms are implemented on existing microprocessor control systems of TD. However, the implementation of intelligent control systems requires a large amount of a priori data. Induction motors (IM) are most widely used in modern electric rolling stock (ERS) [29,30]. FOC [31,32,33], direct torque control (DTC) systems [34,35,36] and model predictive control (MPC) method [37,38,39] are used as ERS control systems.

Various approaches exist for designing energy-efficient drives with field-oriented control of induction motors. These approaches are presented in [40] and can be classified as follows:

- Improvement of the energy efficiency of induction motors.

- Application of energy-efficient control systems for induction motor drives.

- Implementation of energy-efficient operating modes of the drives.

- Improvement of operational maintenance practices.

- Enhancement of manufacturing technologies.

The factors that directly affect the overall efficiency of induction motor drives are summarized in Table 1 [30].

Table 1.

Factors affecting the overall efficiency of induction motor drives. Reproduced from [30].

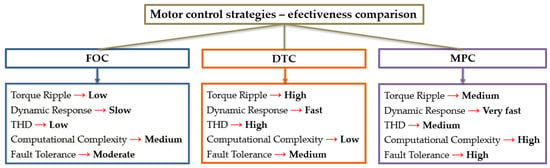

Since modifications to the motor design, the type of inverter power semiconductor devices, the inverter hardware topology, and the cooling systems of both the converter and the motor require substantial capital investment—and operating conditions and maintenance practices are beyond the scope of this study—improving the overall efficiency of induction motor drives is primarily achieved through the application of energy-efficient control strategies. In [41], the effectiveness of various control strategies is analyzed, and their comparative assessment is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparative assessment of the efficiency of various control strategies. Inspired by the data reported in [30].

An analysis of the data presented in Figure 1 indicates that drives employing FOC exhibit the lowest torque ripple, reduced THD of the stator current, and superior fault-tolerance characteristics. In addition, it is reported in [32] that traction drives with FOC provide better speed regulation performance compared to DTC. This characteristic is particularly important for the traction drive of a mainline locomotive. Therefore, a traction drive based on FOC is considered in the subsequent analysis.

In study [42], the following classification of field-oriented control methods for induction motors is proposed: direct field-oriented control (DFOC) [31,43] and indirect field-oriented control (IFOC) [44,45].

In drives employing DFOC, the occurrence of resistance deviations leads to an undesirable drop in speed; however, the speed recovers within a very short time interval once the deviation diminishes. In general, the DFOC method performs poorly when the stator and rotor resistances increase, due to excessive voltage drops across the stator and rotor windings. Moreover, an increase in the rotor magnetic flux is caused by the discrepancy between the calculated flux and the actual flux in the motor, as well as by differences between the resistance values used in the observer and those of the motor. Unlike DFOC, IFOC operates reliably and stably in the field-weakening region [42]. Since, in contrast to DFOC, IFOC demonstrates robust and stable performance under field-weakening conditions, energy-efficient control algorithms are considered specifically for this method of implementing field-oriented control of induction motors.

An analysis of energy-efficient IFOC algorithms is presented in [46]. The following algorithms were considered:

- Hybrid FOC based on a phase-locked loop (PLL) [46].

- FOC with an extended Kalman filter (EKF) [47,48].

- FOC with a sliding-mode observer (SMO) [49,50,51].

- Baseline IFOC.

The results of the comparative analysis of the above algorithms are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative assessment of the efficiency of various control strategies. Reproduced from [46].

An analysis of the results presented in Table 2 indicates that the hybrid PLL-based FOC algorithm provides high accuracy and favorable transient performance but exhibits lower robustness to parameter variations than FOC with a sliding-mode observer, as well as higher computational complexity and implementation cost compared to the baseline IFOC approach.

Among the factors affecting the efficiency of FOC-based drives, Table 2 identifies the switching strategy of the inverter power electronic devices. Therefore, in order to develop an energy-efficient control strategy for a traction drive, an analysis of power losses in its components is carried out below.

From the analysis of the data in [52,53] power losses in TDs with FOC can be divided into power losses in TDs and inverters. Power losses in TD are divided into magnetic power losses in motor steel, thermal power losses in the motor windings, and power losses from high-frequency harmonics. Power losses in the inverter are divided into constant and switching.

Magnetic power losses in TM steel depend on the following factors [54,55]:

- Design parameters and properties of the material from which the corresponding TM elements are made.

- Magnetic flux through the structural elements.

- Supply voltage frequency.

Thermal power losses in TM windings are caused by the flow of current through them. With increasing current, the amount of heat released by the active resistances of the TM windings increases. An increase in the amount of heat released by the windings leads to an increase in temperature and, as a result, to an increase in the active resistances of the windings. This leads to an increase in power losses in the TM windings [56,57].

In systems with FOC, a pulse-width modulation (PWM) algorithm is implemented to control the inverter. THD of the TD stator phase currents depends on the frequency of the PWM pulses. The higher the frequency of the PWM pulses, the lower the THD value [31,32,33]. Reducing the THD value leads to a decrease in power losses in the traction motor from high-frequency current harmonics and a decrease in the torque ripple coefficient on the motor shaft, which leads to an improvement in the reliability indicators of the mechanical part of the TD [58]. But in TD systems, powerful IGBT modules are used as power switches of the inverter, the maximum switching frequency of which, according to the data of the manufacturers, is limited to a frequency of 1 kHz [59,60]. While in general industrial drives this value is within several tens of kHz.

The current flowing through the IGBT and the voltage drop across them cause constant power losses in the inverter. The magnitude of the switching energy losses in the IGBT depends on the values in unstable modes of the currents flowing through the insulated gate bipolar transistor (IGBT), the voltage drops across them and the switching frequency [59,60]. Moreover, the magnitude of the switching energy losses is directly proportional to the value of the switching frequency (PWM pulse frequency). In FOC synthesis [61,62], the frequency of the inverter PWM pulses is assumed to be constant. And the parameters of such FOC controllers as current, flux linkage and speed are functions of this frequency.

From the analysis of the time diagrams of torque and phase currents of the TM stator [31,32,33] it is seen that THD and the torque ripple coefficient depend on the frequency of the TM supply voltage, with its increase these parameters increase. This fact is explained by the fact that at a lower frequency of the supply voltage the period of the stator phase currents is larger, and it is filled with a larger number of PWM pulses. With an increase in the frequency of the supply voltage, the period of the stator phase currents decreases and, as a result, the corresponding number of PWM pulses decreases. Therefore, when the TD supply voltage frequency decreases due to a larger number of PWM pulses, the THD value decreases and, as a result, losses from high-frequency harmonics of the stator phase currents decrease. The PWM pulse frequency remains constant and, as a result, the switching energy losses in the inverter may be overestimated. Thus, optimizing the choice of PWM pulse frequency to reduce power losses is a relevant task.

The objective of this study is to develop a concept for improving the energy efficiency of the traction drive through the adaptation of the field-oriented control system to the locomotive operating speed.

To achieve the stated objective, the following research contributions were made:

- The selection of tuning methods for maximizing the performance of the controllers in the baseline field-oriented control (FOC) system of the induction motor was substantiated.

- Analytical relationships were derived, and the parameters of the controllers and filters for the current, flux linkage, and speed control loops of the baseline FOC IM were calculated.

- As a result of simulation modeling, the transient responses of each control loop were obtained, on the basis of which the performance indices of the transient processes were evaluated.

- Methods for adapting the parameters of the controllers and filters of the baseline FOC induction motor system to the locomotive operating speed were proposed.

- A control scheme for the inverter was proposed, enabling the adaptation of the controller parameters of the baseline field-oriented control (FOC) induction motor system to the locomotive operating speed.

- A filter structure was developed, allowing the parameters of the filters in the baseline FOC induction motor system to be adapted to the locomotive operating speed.

- Based on a comparative analysis of the simulation results of the baseline and adaptive FOC induction motor systems, the effectiveness of the proposed technical solutions was demonstrated.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2—selection of the object of study. Section 3 is devoted to the development of a simulation model of the basic FOC scheme. Section 4 reports on the simulation model of the FOC scheme, the parameters of which are adapted to the speed of the locomotive. Section 5 presents the simulation results and discussion. Section 6 summarizes the results.

2. Selection of the Research Object

When conducting the research, the following methods can be employed:

- Performing investigations directly on the traction drive of electric rolling stock.

- Applying scaling approaches, i.e., conducting studies on drives equipped with lower-power motors.

- Simulation-based modeling.

Conducting research directly on the traction drive of electric rolling stock requires substantial capital investment. In addition, the present study addresses only the conceptual foundations of adapting the field-oriented control system of traction induction motors to the operational parameters of the locomotive. Implementing the necessary modifications to the control system on a locomotive in active service also requires appropriate certification.

The application of scaling approaches would be inappropriate. This is because, unlike industrial induction motors, traction induction motors operate under magnetic saturation conditions; that is, their magnetic systems exhibit nonlinear behavior. At present, a validated methodology for transitioning from a linear magnetic system to a nonlinear one has not yet been established. Consequently, results obtained from industrial induction motors with linear magnetic systems cannot be reliably transferred to traction induction motors.

For these reasons, the authors decided to conduct the study using simulation-based modeling. This approach makes it possible to develop an induction motor model that accounts for magnetic circuit saturation and to construct a field-oriented control system whose parameters are adapted to the magnetic saturation characteristics of the induction motor.

Therefore, it was carried out using simulation modeling on the example of a mainline electric locomotive of the DS3 series [63,64,65]. The object of research is its TD. The electric locomotive uses the IM of the STA 1200 series as TM, the parameters of which are given in Table 3 [66].

Table 3.

Parameters of an induction motor. Adapted from [66].

Other IM parameters required for developing a TD simulation model are calculated below.

3. Development of a Simulation Model of the Basic FOC Scheme

3.1. Selection of the Basic FOC Scheme

When developing the simulation model, several assumptions were made about the absence of:

- Thermal power losses in the TM.

- Power losses from higher current harmonics in the TM.

- Switching power losses in the inverter.

Also, the disturbances acting on the TD caused by changes in train dynamics [67,68,69,70] and disturbances caused by noise in IGBT modules [71,72,73,74] were not considered. When developing the simulation model, the nominal static moment served as the TD load, which was given in the form of a function Tc = 1(t − tdelal), where tdelal is the time of switching on the speed controller. In other words, when creating the TD simulation model, a load model was not developed, which is a function of the weight and movement of the train, the parameters of the track section, etc. [75].

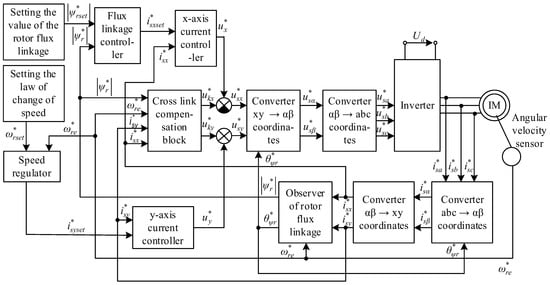

Due to the limitations in mass and dimensions, IMs are designed to operate in the saturation mode. In [75], a simulation model of the output part of the TD with FOC is presented, in which the structural elements of the FOC are designed considering the IM saturation (Figure 2). That is why it was chosen as the basic scheme. Based on this block diagram, a simulation model of the baseline FOC scheme was developed; after introducing minor structural modifications, a speed-adaptive FOC scheme was also implemented.

Figure 2.

Structural scheme of FOC with induction TD. Adapted from [75].

The simulation model of an induction TM in [75] is made in three-phase coordinates, the conceptual principles of its construction were given in [76], and the implementation considering magnetic losses in steel [77]. They were considered by creating an additional static moment on the shaft of an induction motor. As shown in [54], this approach is not entirely correct and it is proposed to consider magnetic losses in the IM steel [78,79,80] by introducing additional electromotive forces into the stator and rotor circuits, which simulate the specified losses. Therefore, in this work, the IM simulation model [77] is taken as a basis.

3.2. The Model of Traffic on the Railway Section

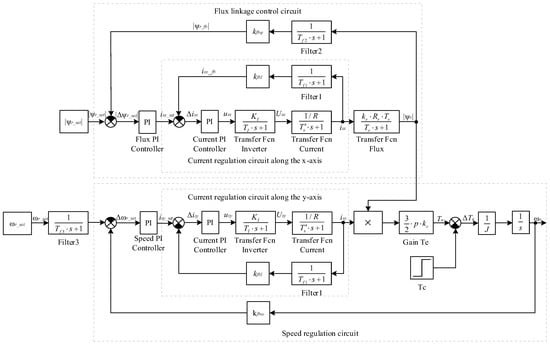

To calculate the parameters and set the controllers of the basic FOC scheme, the structural scheme of this system [81] was used, which is depicted in the transfer functions of the elements (Figure 3). To determine the parameters of the controllers, several auxiliary IM parameters were calculated. Since the simulation model of the FOC scheme is made in relative units, a system of basic quantities was calculated (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Structural diagram of TD with FOC in transfer functions. Adapted from [81].

3.2.1. Calculation of Current Controller Parameters

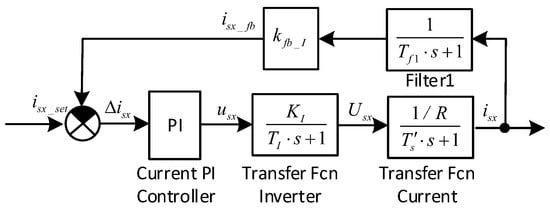

The structural diagram of the TM with FOC consists of a flux-linkage control loop and an angular velocity control loop (Figure 3). Each of these loops includes a current control loop—a current control loop along the x axis to the flux-linkage control loop, and a current control loop along the y axis to the velocity control loop. In accordance with Figure 3, the current control loop diagram has the form (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Current control loop in the TD with FOC.

The current loop (Figure 4) contains an ideal inverter with a transfer function:

where the inverter gain KI is defined as:

In Equation (2) Usnom = 1080 V is the modulus of the space vector of the stator phase voltage (Table 4); Ucmax = 1 V is the maximum inverter control voltage.

Table 4.

Calculation of auxiliary IM parameters. Adapted from [67].

The inverter time constant is defined as:

where fsnom = 55.8 Hz is the nominal frequency of the stator supply voltage; N = 20 the number of PWM pulses.

The inverter load is represented by the equivalent resistance of the stator winding R and the time constant Ts. The equivalent resistance of the stator winding in absolute units is calculated as:

where r = 0.0188 r.u. the equivalent resistance of the stator winding in relative units (Table 5); Zb = 2.5216 Ω is the base active resistance (Table 5).

Table 5.

The results of the calculation of the quality indicators of the control loops.

Equivalent time constant:

where = 8.0386 r.u. is the equivalent time constant in relative units (Table 5); Ωb = 350.6 1/s is the base frequency (Table 5).

Load transfer function (stator winding circuit):

Filter transfer function Filtr1:

where Tf1 = 0.1 · TI = 0.1 · 0.000448 = 0.0000448 s, the filter time constant. The current feedback coefficient is defined as:

where Icsmax = 1, A—maximum value of current in FOC in stable mode; Ib = 605.7, A—base value of current (Table 5).

As can be seen from Figure 3, the open circuit of the current control loop contains two aperiodic links—inverter and stator winding circuit. Moreover, the time constant of the stator winding Ts is greater than the time constant of the inverter TI (Ts = 0.0229 s > TI = 0.000448 s). For such circuits, the calculation of the controller parameters is most expedient to perform by the Absolute Value Optimum (AVO) method [82,83]. In accordance with this method, it is recommended to use a proportional-integral controller with a transfer function of the form:

where kcontr gain coefficient of the proportional part of the controller; Tiz the isodrome time equal to the large time constant, i.e., Tiz = Ts.

For the current controller, the gain of the proportional part of the controller is defined as:

where ak = 2 the optimization coefficient according to the absolute optimum method; Ts = Tiz1 = 0.0229 s, the large time constant equal to the isodrome time Tiz1 = Ts;

Tμ1 = TI + Tf1 = 0.000448 + 0.0000448 = 0.00049283 s, the equivalent small time constant of the current loop.

For the current controller, the gain of the integral part of the controller is defined as:

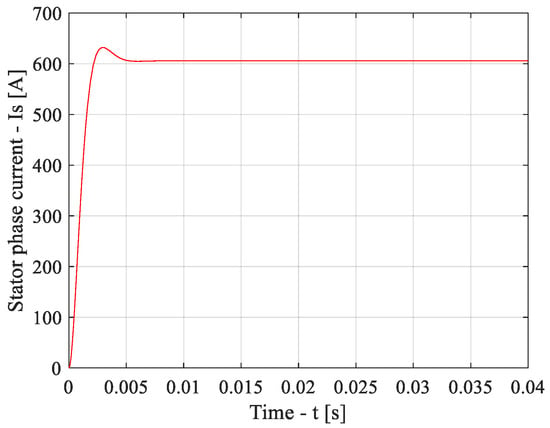

A simulation model was developed in the MATLAB 2020b software environment for the current regulation loop scheme in the TD with FOC (Figure 3). On it, under the condition of a stepwise control influence, the transient characteristic of the current regulation loop was obtained (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Transient characteristic of the current control loop.

3.2.2. Calculation of the Parameters of the Flux Linkage Controller

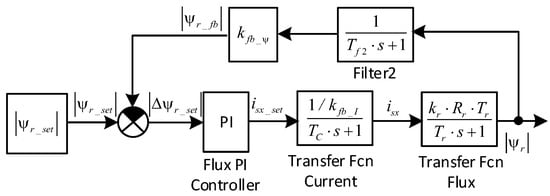

Considering the above optimized current loop, the structural diagram of the flux linkage loop (Figure 3) has the form (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Structural diagram of the flux linkage loop.

The flux linkage loop contains an equivalent subordinate current loop, the transfer function of which has the form:

where TC = ak · Tμ1 = 2 · 0.00049283 = 0.000986 s, the equivalent time constant of the current loop.

The transfer function of the flux linkage block has the form:

where Tr = T*r/Ωb = 267.0967/350.6 = 0.7618 the rotor circle time constant in s.

The transfer function of filter Filtr2 has the form:

where Tf2 = TI = 0.000448 s, the time constant of filter 2.

The feedback coefficient for the flux linkage is calculated as:

As can be seen from Figure 6, the open circuit of the current control loop contains two aperiodic links—the transfer function of the equivalent subordinate current loop and the flux linkage transfer function. Moreover, the flux linkage time constant (rotor circle time constant) Tr is greater than the equivalent current loop constant TC (Tr = 0.7618 s > TC = 0.000986 s). For such circuits, the calculation of the controller parameters is most expediently performed by the absolute value optimum (AVO) method [82,83]. In accordance with this method, it is recommended to use a proportional-integral controller, the transfer function of which is described by Expression (9).

The gain coefficient of the proportional part of the flux linkage controller is defined as:

where ak = 2 optimization coefficient by the absolute value optimum method; Tr = T*r/Ωb = Tiz2 = 0.7618 s—a large time constant equal to the time of the isodrome Tiz2; Tμ2 = TC + Tf2 = 0.000986 + 0.000448 = 0.0014 s, the equivalent small-time constant of the flux linkage.

The gain coefficient of the integral part of the flux linkage controller is defined as:

For the scheme of the flux linkage control loop in the TD with FOC (Figure 6), a simulation model was developed in the MATLAB 2020b software environment, on which, under the condition of a stepwise control effect, the transient characteristic of the flux linkage control loop was obtained (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Transient characteristic of the flux linkage control loop.

Figure 8.

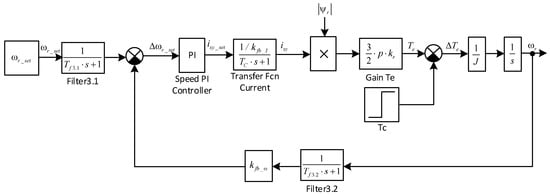

Structural diagram of the speed loop.

The speed loop contains an equivalent subordinate current loop with a transfer function:

where TC = ak · Tμ1 = 2 · 0.00049283 = 0.000986 s, the equivalent constant of the current loop.

The magnetic flux is represented by the nominal value |ψrx| = ψnom = Usnom/ωnom = (30 · 1527)/(3 · π · 1110) = (30 · p · Usnom)/(π · nnom) = 4.3799 Wb.

The gain of the torque block is calculated as:

The transfer function of the filter Filtr32 has the form:

where Tf3.2 = Tf2 = 0.000448 s, the time constant of the filter 3.2 (Figure 8).

The transfer function of the IM is represented by an integrating element with a time constant TInt = 1 s and a gain of KInt = 1/J = 1/39 = 0.0256.

The speed feedback coefficient is:

where ωr_set = 1, rad/s the value of the output signal of the angular velocity controller in a stable mode; Ωb = 350.6, rad/s the basic value of the flux linkage (Table 5); p = 3 the number of pole pairs (Table 4).

As can be seen from Figure 8, the open circuit speed control circuit contains two links—aperiodic and integral. The aperiodic link is the transfer function of the equivalent subordinate current loop, and the integral link is the transfer function of the motor. Moreover, the motor time constant TInt is greater than the equivalent current loop constant TC (TInt = 1 s > TC = 0.000986 s). For such circuits, the calculation of the controller parameters is most expediently performed by the symmetrical optimum (SO) method [84,85]. In accordance with this method, it is recommended to use a proportional-integral controller, the transfer function of which has the form (9).

The gain coefficient of the proportional part of the speed controller is determined in accordance with the equation:

where Tμ3 = TC + Tf3.2 = 0.000986 + 0.000448 = 0.0014 s, the small-time constant of the speed loop.

The equivalent time constant of the optimized speed loop (the time of the speed controller isodrome) is determined as:

where bk = 2 the optimization coefficient by the symmetric optimum method.

The gain coefficient of the integral part of the speed controller is determined as:

Transient processes in the symmetric optimum optimized loop are characterized by large overshoot and oscillation. Their cause is the forcing link in the numerator of the controller transfer function. Compensation of the forcing effect is achieved by installing an inertial link (filter) Filtr31 with a transfer function in the task channel:

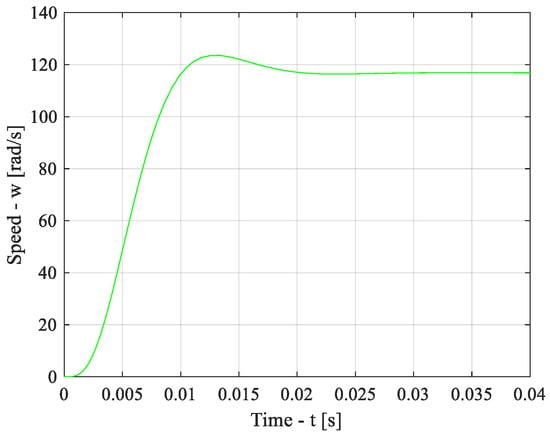

For the speed control circuit scheme in the TD with FOC (Figure 8), a simulation model was developed in the MATLAB 2020b software environment, on which, under the condition of a stepped control influence, the transient characteristic of the speed control circuit was obtained (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Transient characteristic of the speed control loop.

3.2.3. Calculation of the Quality Indicators of the Operation of the Control Loops

The quality indicators of the operation of the circuits when working out the stepped control influence are as follows:

- Overshoot.

- Time of the first entry into the 5% zone.

- Time of the unstable mode.

- Error in determining the controlled value in the stable mode.

The overshoot of the automatic control system is determined in accordance with the expression:

where Xmax the maximum value of the controlled value; Xstab the value of the controlled variable in the stable mode.

When implementing the AVO method [82,83], the overshoot value should not be more than 4.32%, and when implementing the SO method [84,85], the overshoot value is not more than 8.14%. In accordance with the AVO method, the time of the first entry into the 5% zone is determined as:

where Tμx the small-time constant of the corresponding circuit.

In accordance with the SO method, the time of the first entry into the 5% zone is determined in accordance with the expression:

For a circuit configured using the AVO method, the time of the unstable mode is equal to the time of entry into the 5% zone. For a circuit configured using the SO method, the time of the unstable mode is determined by the formula:

From Figure 4, the value of the time of the first entry into the 5% zone is determined, which was 0.00193 s.

The error in determining the controlled quantity in a stable mode is calculated as:

where Xset the set value of the controlled parameter; Xstab the value of the controlled parameter in a stable mode.

To calculate the quality indicators of the current control loop from Figure 5, the following parameters are defined: the current value in a stable mode Istab = 605.7 A; the maximum value of the phase current Ismax = 631.2 A; the time of the first entry into the 5% zone tI(5) = 0.00193 s.

To calculate the quality indicators of the flux linkage control loop from Figure 7, the following parameters are defined: the flux linkage value in a stable mode ψstab = 4.356 Wb; the maximum value of the flux linkage ψmax = 4.543 Wb; the time of the first entry into the 5% zone tω(5) = 0.0092 s.

To calculate the quality indicators of the speed control loop from Figure 9 the following parameters are defined: the speed value in the stable mode ωstab = 116.9 rpm; the maximum speed value ωmax = 123.5 rpm; the time of the first entry into the 5% zone tω(5) = 0.0092 s. The results of the calculation of the quality indicators are listed in Table 5.

In accordance with the AVO and SO methods, the error values of the controlled quantities in the stable mode should be equal to zero. The obtained indicators of the quality of the current loop operation when testing the stepwise control influence indicate the correctness of the adjustment of the controllers by the AVO (current loops and flux linkage) and SO (speed loops) methods.

When modeling FOC, several studies [86,87] use PI controllers with saturation. This approach allows to reduce the amount of overshoot but increases the time of the unstable mode in the circuits [88,89,90,91]. Since the overshoot in the corresponding circuits does not exceed the values regulated by the corresponding methods of adjusting the controllers to the optimum, the use of saturation in them is inappropriate. The diagram of the simulation model of the TD with FOC is given in the next section.

4. Development of the Conceptual Basis for Adapting FOC by Traction IM to the Operational Parameters of the Locomotive

4.1. Development of the Concept of Adaptation Basics

The proposed concept of adaptation of FOC by traction IM to the operational parameters of the locomotive is based on the following aspects:

- Justification of the need to adapt the FOC operation to the operational parameter of the locomotive.

- Selection of the operational parameter of the locomotive to which the FOC operation is adapted.

- Justification of the selection of FOC elements and which parameters should be adapted.

As was noted, the PWM frequency is a constant value. This value is proportional to the nominal frequency of rotation of the IM shaft. FOC synthesizes supply voltage signals, the frequency of which is proportional to the specified frequency of rotation of the motor shaft. Therefore, with a change in the specified frequency of rotation of the motor shaft, the number of PWM pulses in the supply voltage period changes. At frequencies of rotation of the motor shaft less than the nominal, the number of PWM pulses in the supply voltage period is greater than at the nominal frequency. This leads to a decrease in the THD value of the IM stator current and, as a result, to a decrease in the level of higher harmonic components in its spectrum. This fact will lead to a decrease in power losses in the IM from higher harmonics of the stator current and to overestimated values of switching power losses. At IM shaft rotation frequencies higher than the nominal, in the supply voltage period the number of PWM pulses is less than at nominal frequency, which leads to an increase in the THD value of the IM stator current. The consequence of this is an increase in the level of higher harmonic components in its spectrum, which will lead to an increase in power losses.

The operation of the FOC is based on the synthesis of IM supply voltage signals. The frequency of these signals is proportional to the given frequency of rotation of its shaft. It is proportional to the frequency of rotation of the wheelset, which, in turn, is proportional to the linear speed of the locomotive. In this regard, the linear speed of the locomotive was chosen as an adaptation parameter. In FOC, the linear speed of the locomotive is set by the speed controller. Therefore, the operation of the FOC is adapted to the speed controller signal.

The THD of the phase current system of the IM stator depends on the number of PWM pulses of the inverter. In this regard, the number of PWM pulses of the inverter is adapted to the speed controller signal. In addition, the parameters of the gain coefficients of the current, flux linkage and speed controllers depend on the frequency of the PWM pulses. The operation of these controllers affects the quality indicators of the FOC. Therefore, the gain coefficients of the specified controllers are also adapted to the speed controller signal.

4.2. Development of an Inverter Control Scheme, the Operation of Which Is Adapted to the Speed Change Function Generator Signal

In [34,35], an inverter is used, the basis of the operation of the control scheme of which is the implementation of PWM. In such schemes, the input parameters are the frequency of the modulated signal and the number of PWM pulses (N). The product of the frequency of the modulated signal and the number of PWM pulses is called the PWM frequency, which in these control schemes has a fixed value. Usually, the frequency of the modulated signal is chosen equal to the nominal frequency of the IM supply voltage (fnom), and the number of PWM pulses is chosen from the following condition:

where fnom the nominal value of the IM supply voltage frequency; fmax the maximum switching frequency of the IGBT of the inverter; N the number of PWM pulses.

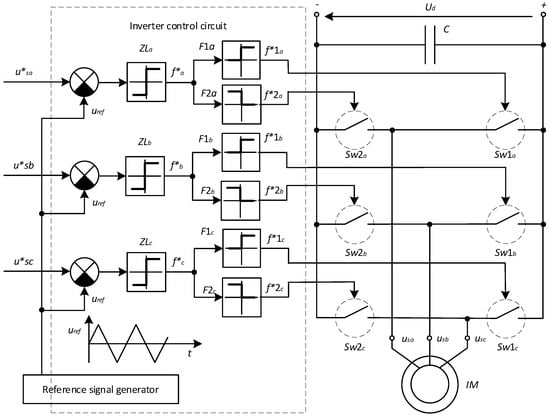

To solve the problem of minimizing the total losses in the FOC of the IM by determining the balance between the values of losses from higher harmonics in the IM and the values of switching losses in the inverter, appropriate studies should be conducted. For this purpose, an inverter control scheme is proposed with adaptation of its operation to the speed change function generator signal. When constructing it, an approach based on the analysis of the functional scheme “Inverter with PWM IM” with a fixed PWM frequency (Figure 10) was used, where the following notations were adopted:

Figure 10.

Functional diagram of the “PWM inverter” with a fixed PWM frequency. Inspired by the concepts reported in [92].

- u*a, u*b, u*c, modulated voltage signals coming from the FOC.

- uref a reference signal, which is a sawtooth, two-sided, symmetrical voltage with a modulation frequency that significantly exceeds the frequency of the modulated voltage signals.

- Zla, Zlb and Zlb zero-elements that provide a comparison of the modulated voltage signals with the reference signal. If u*a,b,c > uref then the output signals of the zero-elements f*a,b,c > 0 otherwise f*a,b,c < 0.

- F1a and F2a, F1b and F2b, F1c and F2c—the shapers of the power switch control signals. They have mutually inverse relay characteristics and separate the zero-element signal Zl by two channels of control of the inverter switches [71]. In addition, small time delays of switching on the switches are provided. This is necessary to prevent short circuits of the DC voltage source Ud through the power switches of the inverter.

- F1a i F2a, F1b i F2b, F1c i F2c—discrete output signals from the shapers that control the switching on of the power switches.

- Sw1a and Sw2a, Sw1b and Sw2b, Sw1c and Sw2c—power switches that alternately connect the motor phase windings to opposite poles of the DC voltage source Ud.

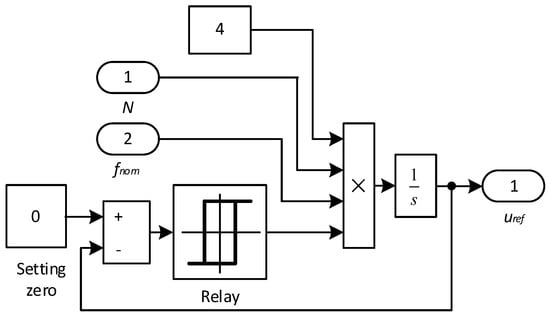

The mathematical model of the sawtooth voltage generator is shown in Figure 11 [92].

Figure 11.

Mathematical model of the sawtooth voltage generator. Inspired by the concepts reported in [92].

The input signals that set the parameters of the output signal uref are the number of pulses N and the nominal frequency of the IM supply voltage fnom. The signal period is 1/(N · fnom), the signal has four intervals—the signal increases by two and decreases by two. Therefore, the period of one interval is equal to 1/(4 · N · fnom).

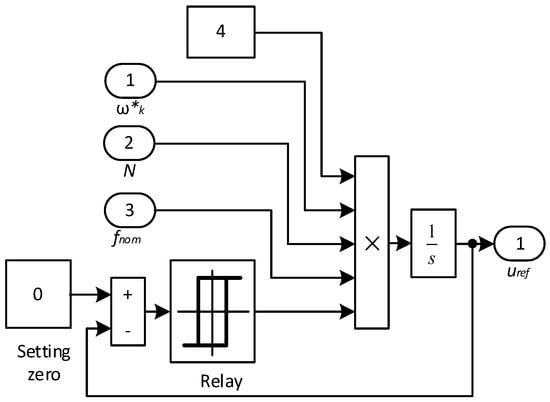

As can be seen from Figure 10 and Figure 11, in the circuit, turning to the power supply frequency of the IM is possible by changing the interval period of the output signal of the sawtooth voltage generator. The speed change function generator signal ω*set is presented in relative units. Therefore, adaptation of the inverter operation to a change in the speed change function generator signal is possible by multiplying the frequency of the interval change of the output signal of the sawtooth voltage generator by the signal ω*set. Taking this fact into account, the mathematical model of the sawtooth voltage generator will have the form (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Mathematical model of the sawtooth voltage generator with adaptation of its operation to the speed change function generator signal.

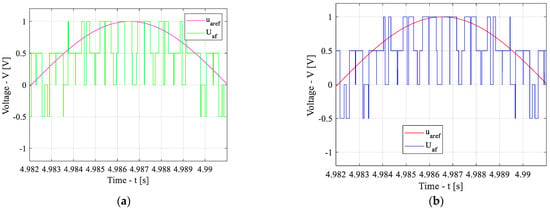

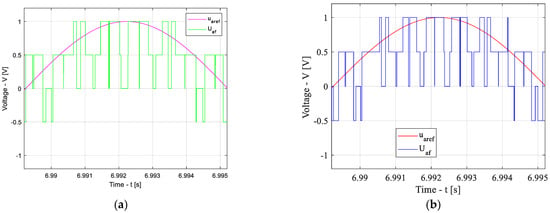

To present the results of the PWM adaptation process, simulation modeling was performed in the MATLAB 2020b software environment for an inverter with both baseline and adaptive inverter control schemes. For the baseline and adaptive control schemes, the time-domain signals of the reference voltage (urefA) and the inverter output voltage (UAf were obtained from the simulation models. Since asymmetric operating modes of the inverter and the induction motor are not considered in this study, it is sufficient to present the PWM adaptation results for a single phase; the results for the other two phases are analogous. Accordingly, the signals urefA and UAf were analyzed.

The simulations were carried out for three operating cases:

- At a speed 50% lower than the rated speed.

- At the rated speed.

- At a speed 25% higher than the rated speed.

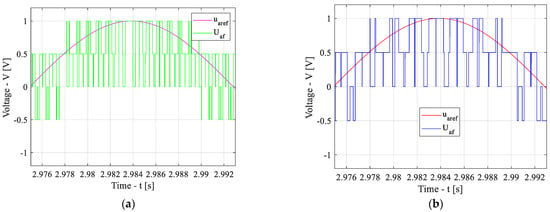

For clarity, the signals urefA and UAf were scaled to 1 V and only the positive half-cycle of the waveforms is presented. The simulation results are shown in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 13.

Time-domain waveforms of the reference voltage (urefA) and inverter output voltage (UAf) at a speed 50% lower than the rated value: baseline scheme (a) and adaptive scheme (b).

Figure 14.

Time-domain waveforms of the reference voltage (urefA) and inverter output voltage (UAf) at rated speed: baseline scheme (a) and adaptive scheme (b).

Figure 15.

Time-domain waveforms of the reference voltage (urefA) and inverter output voltage (UAf) at a speed 25% higher than the rated value: baseline scheme (a) and adaptive scheme (b).

As shown in Figure 13, at a speed 50% lower than the rated value, the number of PWM pulses per signal half-period for the baseline scheme is greater than that at the rated speed. Figure 14 demonstrates that, at the rated speed, the number of pulses per half-period is the same for both the baseline and adaptive schemes. In contrast, Figure 15 indicates that, at a speed 25% higher than the rated value, the number of PWM pulses per half-period for the baseline scheme is lower than that at the rated speed. At the same time, for the adaptive scheme, the number of pulses per half-period remains identical for all three operating cases.

4.3. Adaptation of Controller Parameters to the Speed Setpoint Signal

4.3.1. Adaptation of Current Controller Parameters

From the analysis of Formula (10) it follows that both the proportional and integral coefficients of the controller in the current loop depend on the PWM frequency. This is explained by the fact that the equivalent small time constant of the current loop Tμ1 depends on the PWM frequency, which, in turn, depends on the PWM frequency. Thus, the equivalent small-time constant of the current loop Tμ1 as a function of the PWM frequency is defined as:

When adapting the operation of the inverter control circuit to the speed setpoint signal, the PWM frequency is equal to 2 · N · fsnom · ω*k. After substituting Expression (32) into Expression (10):

When calculating the gain of the integral part of the controller in the current loop, Expression (33) should be substituted into Expression (11), since the isodrome time Ts = Tiz1 does not depend on the inverter frequency.

4.3.2. Adaptation of the Parameters of the Flux Linkage Controller

From the analysis of Formula (16), it follows that both the proportional coefficient and the integral coefficient of the controller in the flux linkage loop depend on the PWM frequency. This is explained by the fact that the equivalent small-time constant of the flux linkage loop Tμ2 depends on the PWM frequency, which, in turn, depends on the frequency of the speed controller. Then the equivalent small-time constant of the flux linkage loop Tμ2 as a function of the PWM frequency is determined in accordance with the expression:

Considering that when adapting the operation of the inverter control circuit to the frequency of the speed change function generator, the PWM frequency will be equal to 2 · N · fsnom · . After substituting Expression (34) into Expression (16):

The isodrome time Tr = Tiz2 does not depend on the frequency of the IM supply voltage. Therefore, when calculating the integral coefficient of the controller in the flux linkage loop, Expression (33) is substituted into Expression (17).

4.3.3. Adaptation of Speed Controller Parameters

From the analysis of Formula (22), it follows that both the proportional coefficient and the integral coefficient of the controller in the speed loop depend on the frequency of the speed change function generator. This is explained by the fact that the equivalent small-time constant of the speed loop Tμ3 depends on the PWM frequency, which, in turn, depends on the frequency of the speed controller. After presenting the equivalent small-time constant of the speed loop Tμ3 as a function of the speed controller frequency:

When adapting the operation of the inverter control circuit to the frequency of the speed controller, the PWM frequency is equal to 2 · N · fsnom · . After substituting Expression (36) into Expression (22):

From the analysis of Formula (23), it follows that the isodrome time of the speed controller depends on the frequency of the IM supply voltage. After substituting Expression (36) into Expression (23):

The expression for determining the integral coefficient of the speed controller is obtained by substituting Expressions (37) and (38) into Expression (24). Given that the PWM frequency will be equal to 2 · N · fsnom · , then:

4.4. Adaptation of the Filter Cutoff Frequency to the PWM Frequency

Analysis of the transfer functions of the filters in the current loop WF1(s) (7), in the flux linkage loop WF2(s) (14) and in the velocity loop WF3.2(s) (20) gave the following results:

- All transfer functions are aperiodic links.

- The time constants of all filters (Tf1, Tf2, Tf3.2), which are inversely proportional to the cutoff frequencies, depend on the frequency of the IM supply voltage.

By analogy with Expressions (32), (33) and (35), the adaptation of the filter time constants to the PWM frequency was performed:

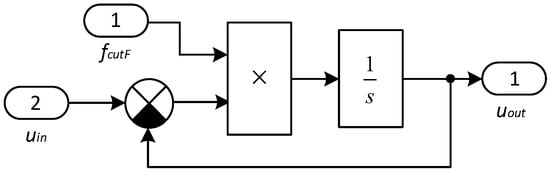

To implement the adaptation of the filter time constants to the PWM frequency, the transfer functions, which are aperiodic links, are decomposed to the integrator level (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The filter transfer function is in the form of an integrator.

The following notations are used in Figure 16:

- uin is the signal value at the filter input.

- uout is the signal value at the filter output.

- fcutF is the filter cutoff frequency, the value of which is inversely proportional to Expressions (41)–(43) depending on the filter being modeled.

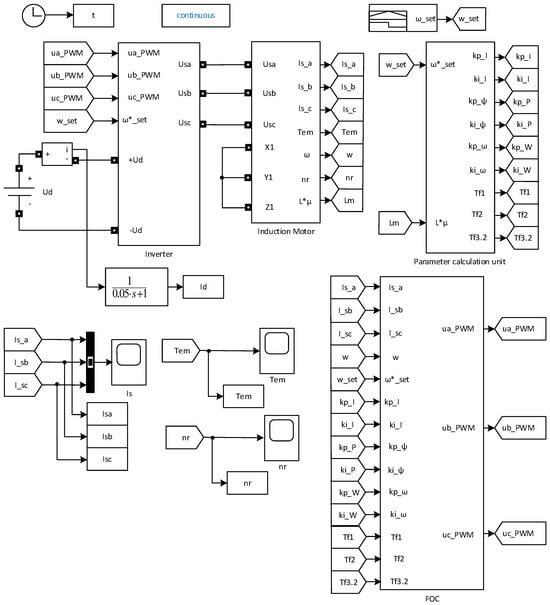

4.5. Development of a Simulation Model of the Output Part of the Traction Drive

As already mentioned in Section 3, the model of the output part of the traction drive is used as a base, in which the IM saturation is considered when calculating the parameters of the FOC structural elements [74]. Saturation was considered by multiplying the value of the main inductance Lμ by the normalized function L*μ = f(ψ*μ), where ψ*μ—the modulus of the spatial vector of flux linkage in relative units.

From Expressions (33), (35), (37) and (39), it follows that both the proportional and integral parameters of the controllers depend on the normalized value of the frequency of the speed change function generator ω*set. From Expressions (40)–(42) the time constants of the filters depend on this frequency. These parameters are calculated in the “Parameter calculation unit”. Considering the above, the complex simulation model of the proposed circuit of the output part of the TD with FOC has the form shown in Figure 17. During the research, the following parameters of the TD operation were analyzed, such as the stator phase currents, the torque on the IM shaft and the motor shaft rotation frequency. To visualize these parameters on the complex simulation model (Figure 17), the elements of the MATLAB/Simulink 2020b Scope library were used. To set the law of change of the IM shaft rotation frequency, the element of the MATLAB/Simulink 2020b Signal Builder library was used.

Figure 17.

Complex simulation model of the adapted circuit of the output part of the TD with FOC.

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

The effectiveness of the proposed technical solutions was carried out by comparing the parameters of the basic and adapted circuit of the output part of the TD. When determining the parameters of the basic circuit on a complex simulation model in the “Parameter calculation unit” signal w_set is taken equal to 1.

When implementing the law of changing the shaft rotation frequency of an induction motor, the following sections were selected:

- Operation of the circuit with the speed controller turned off, necessary for the induction motor to enter the saturation mode.

- Acceleration of the induction motor to a frequency equals half the nominal speed.

- Operation of the induction motor at a frequency equal to half the rated speed.

- Acceleration of the induction motor to a frequency equal to the rated speed.

- Operation of the induction motor at a frequency equal to the rated speed.

- Acceleration of the induction motor to a frequency 25% higher than the rated speed.

- Operation of the induction motor at a frequency 25% higher than the rated speed.

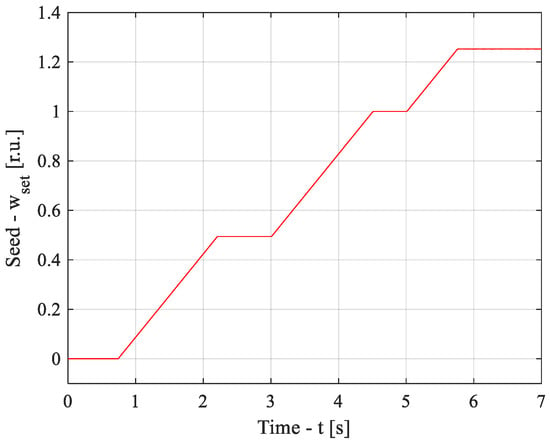

The acceleration for all intervals of IM acceleration is the same. The law of change in the motor shaft speed is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

The law of change in the motor shaft speed.

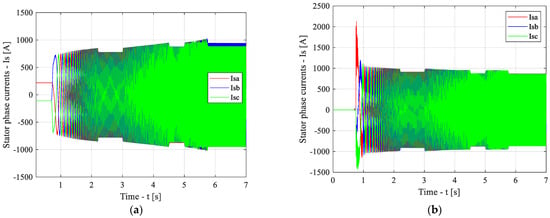

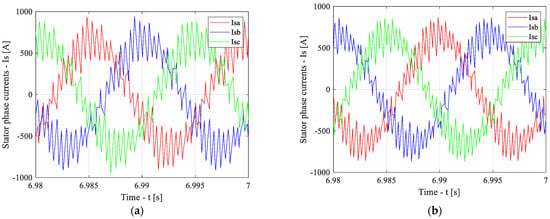

As a result of the simulation modeling, start-up waveforms of the stator phase currents were obtained for the baseline (Figure 19a) and adaptive (Figure 19b) schemes.

Figure 19.

Start-up waveforms of the stator phase currents for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

An analysis of the start-up waveforms of the stator phase currents (Figure 19) indicates that, in the adaptive scheme, a significant overshoot of the phase-A current occurs at the moment when the speed change function generator is activated; however, the system stabilizes rapidly. Under transient operating conditions, as the set speed value increases, the stator currents increase in the baseline scheme, whereas they decrease in the adaptive scheme. Under steady-state conditions, the phase current magnitudes remain constant in both schemes. Nevertheless, in the baseline scheme, the phase current magnitude increases with increasing set speed, while in the adaptive scheme it decreases slightly.

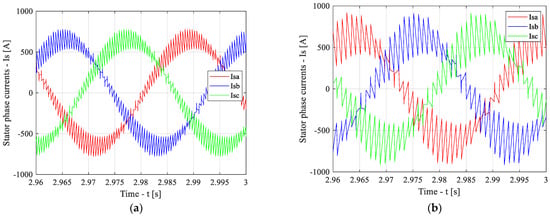

Figure 20 presents the time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at a speed 50% lower than the rated value for the baseline (Figure 20a) and adaptive (Figure 20b) schemes. As can be observed from Figure 20, the baseline scheme exhibits a lower level of higher-order harmonics in the stator phase currents compared to the adaptive scheme. This is attributed to the higher number of PWM pulses per period in the baseline scheme at this operating speed relative to the adaptive scheme.

Figure 20.

Time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at a speed 50% lower than the rated value for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

Figure 21 presents the time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at the rated speed for the baseline (Figure 21a) and adaptive (Figure 21b) schemes. As can be observed from Figure 21, the level of higher-order harmonics in the stator phase currents is the same for both the baseline and adaptive schemes. This is due to the identical number of PWM pulses per period in the baseline and adaptive schemes at this operating speed.

Figure 21.

Time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at the rated speed for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

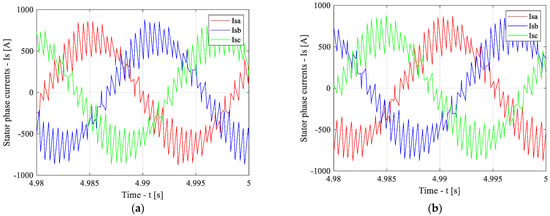

Figure 22 presents the time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at a speed 25% higher than the rated value for the baseline (Figure 22a) and adaptive (Figure 22b) schemes. As can be observed from Figure 22, the baseline scheme exhibits a higher level of higher-order harmonics in the stator phase currents compared to the adaptive scheme. This is attributed to the lower number of PWM pulses per period in the baseline scheme relative to the adaptive scheme at this operating speed.

Figure 22.

Time-domain waveforms of the stator phase currents under steady-state conditions at a speed 25% higher than the rated value for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

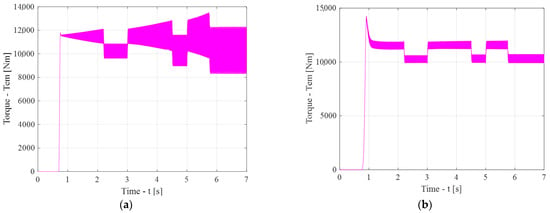

An analysis of the start-up torque waveforms (Figure 23) indicates that, in the adaptive scheme, a significant torque overshoot occurs at the moment when the speed change function generator is activated; however, the system stabilizes rapidly. Under transient operating conditions, as the set speed value increases, torque ripple increases in the baseline scheme (Figure 23a), whereas it remains stable in the adaptive scheme (Figure 23b). Under steady-state conditions, the torque magnitude remains constant in both schemes. Nevertheless, in the baseline scheme, the torque magnitude increases with increasing set speed, while in the adaptive scheme it remains constant.

Figure 23.

Start-up torque waveforms for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

In Figure 24, the start-up responses of the motor shaft rotational speed are presented for the baseline (Figure 24a) and adaptive (Figure 24b) schemes.

Figure 24.

Start-up waveforms of the motor shaft rotational speed for the baseline (a) and adaptive (b) schemes.

An analysis of the start-up responses of the motor shaft rotational speed (Figure 24) indicates that, in the adaptive scheme (Figure 24b), a nonlinear segment appears at the moment when the speed change function generator is activated, after which the motor shaft speed varies according to a linear law. The presence of this nonlinear segment is attributed to the significant overshoot of the stator phase currents. In the baseline scheme, the motor shaft rotational speed (Figure 24a) varies according to a linear law throughout the start-up process.

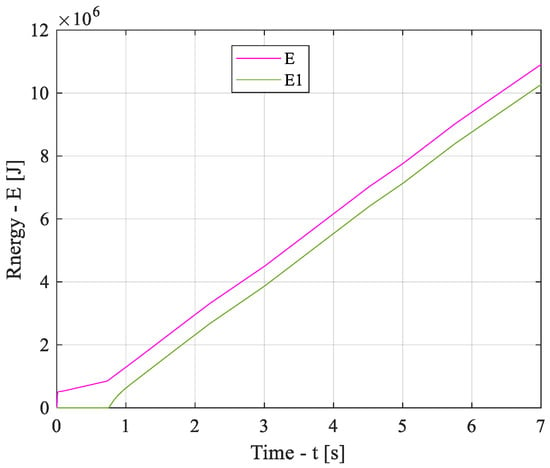

Analysis of the energy consumed by both schemes (Figure 21) shows that the proposed scheme consumes energy by 5.85%. This circumstance is explained by the fact that in the time interval from the motor start to the speed controller activation, the proposed scheme does not consume the power required to saturate the motor magnetic system. This was made possible by adaptively adjusting the FOC parameters to the speed controller frequency.

From the torque diagrams (Figure 23a,b) for stable operating modes, the average values of the torque (Tav) and the average values of the torque ripples (ΔT) were determined. Based on the obtained average values of the torque and its ripples, the value of the torque ripple coefficient was calculated in accordance with the expression [93]:

where Tav the average value of the torque; ΔT the average value of the torque ripples.

The total values of the energy consumed by TD for both studied schemes and the calculation results are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of simulation modeling.

Based on the phase current waveforms under steady-state conditions for the baseline control scheme (Figure 20a, Figure 21a, and Figure 22a) and for the adaptive control scheme (Figure 20b, Figure 21b, and Figure 22b), the components of the amplitude–frequency spectrum were determined, from which THD was calculated. The amplitude–frequency spectrum components were obtained using the discrete Fourier transform in accordance with Equations [94,95]:

where IsA(fi) the i-th component of the stator current spectrum of phase A; IsA(tn) the n-th time sample of the stator phase-A current; N = 128 the number of spectral components of the stator phase-A current.

THD of the stator phase-A current were calculated using Equations [96,97]:

where |IsA(fi)| the magnitude of the i-th component of the stator phase-A current spectrum.

The results of the calculations of the THD of the stator phase-A current are presented in Table 6.

Based on Figure 24a,b, the motor shaft rotational speeds under steady-state conditions were determined for the baseline and adaptive schemes, respectively. The obtained results are summarized in Table 6.

In accordance with Equation (47), the errors in estimating the motor shaft rotational speed were calculated. The corresponding results are also presented in Table 6.

The error in estimating the motor shaft rotational speed under rated operating conditions is determined in accordance with the following expression:

where nrnom = 1110 rpm the rated value of the motor shaft rotational speed according to the manufacturer’s data (Table 4); nrm the motor shaft rotational speed value obtained through simulation.

When determining the motor shaft rotational speed estimation error at speeds 50% below and 25% above the rated value, the parameter nrnom in Equation (47) was multiplied by 0.5 and 1.25, respectively.

Comprehensive indicators of energy efficiency include the efficiency factor (η) and the power factor (kP). In the context of a traction drive, the efficiency is defined as the ratio of the useful mechanical power at the motor shaft to the active electrical power drawn from the supply. The power factor is defined as the ratio of the active power drawn from the supply to the apparent power drawn from the supply. However, since the traction drive (inverter) is powered from a DC link, the use of the power factor in this case is not appropriate.

For steady-state operating conditions, the efficiency was calculated in accordance with the following expression:

where P2 useful mechanical power at the motor shaft; P1 denotes the active electrical power drawn from the supply.

The useful mechanical power at the motor shaft was determined as:

where Tav is the average torque, and nr enotes the motor shaft rotational speed.

The active power drawn from the supply was determined using the following expression:

where Ud—the direct voltage of the inverter supply, and Id the direct current consumed by the transformer.

The results of the efficiency calculations are presented in Table 6. Since determining the efficiency of the drive under transient operating conditions is a nontrivial task, while the drive consumes electrical energy during transients as well, the impact of transient performance on the energy efficiency of the traction drive was analyzed. For this purpose, energy consumption waveforms for the baseline and adaptive schemes were obtained using the simulation model (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Time diagrams of the consumed energy for the basic (E) and adapted (E1) schemes of the output part of the TD with FOC.

The consumed TD energy was calculated in accordance with the expression:

where t—time.

From the analysis of the results, it follows that for the basic scheme with an increase in the frequency of the IM supply voltage in a steady state, the value of the torque ripple coefficient increases much faster than for the adapted scheme. This circumstance is explained by the presence of adaptation of the parameters of the inverter, controllers and filters in the proposed scheme.

An analysis of the results presented in Table 6 indicates that, for the adaptive scheme, the values of the stator phase-A current harmonic distortion coefficients under steady-state conditions remain constant across the entire speed range. For the baseline scheme, at a speed equal to half of the rated value, this coefficient is lower than that of the adaptive scheme; however, at the rated speed and at a speed 25% higher than the rated value, it is higher than that of the adaptive scheme. The lower THD of the stator phase-A current observed for the adaptive scheme at the rated speed is attributed to the adaptation of the filters in the current, flux-linkage, and speed control loops to the rotational frequency of the induction motor shaft.

As can be seen from Table 6, for the baseline scheme, the error in estimating the motor shaft rotational speed is identical at locomotive operating speeds 50% below the rated value and at the rated speed; however, with increasing locomotive speed, the estimation error increases. For the adaptive scheme, the motor shaft speed estimation error remains constant across all three operating conditions, and its value is three times lower than that of the baseline scheme at speeds 50% below the rated value and at the rated speed, and five times lower at a speed 25% above the rated value.

Analysis of the energy consumed by both schemes (Figure 25) shows that the proposed scheme consumes energy by 5.85%. The obtained results can be explained by the following factors:

- During the time interval from motor start-up to the activation of the speed change function generator, the adaptive scheme does not consume the power required to saturate the motor magnetic system.

- The adaptive scheme exhibits superior transient performance compared to the baseline scheme, with the exception of the moment when the speed change function generator is activated.

The authors continue to work on this research topic. In particular, ongoing studies are focused on investigating the effects of disturbances of both electrical and mechanical origin on the performance of the locomotive traction drive. In addition, the authors are developing an algorithm for optimizing the controller parameters while accounting for the aforementioned disturbances. Until these studies are completed, a quantitative comparison with other methods in terms of performance indicators such as response time, ripple, and energy efficiency would be inappropriate. Therefore, in the present work, the authors have limited the analysis to qualitative indicators only. As a reference, Table 2 presented in Section 1 was used.

When formulating the qualitative assessment of the proposed method, the authors were guided by the following considerations:

- Since the proposed method does not require significant circuit-level modifications to the baseline scheme and does not involve computationally intensive calculations, the rotor magnetic flux angle estimation method, transient performance, robustness to parameter variations, computational complexity, and implementation cost are expected to be comparable to those of the baseline scheme.

- The steady-state accuracy is expected to be moderately high, as the controller and filter parameters are adapted to the supply frequency of the induction motor.

An analysis of the results presented in Table 7 indicates that the proposed method is inferior only in terms of steady-state accuracy when compared with the hybrid phase-locked loop (PLL)-based FOC method. This can be explained by the fact that, in the proposed method, the rotor magnetic flux angle is estimated based on slip estimation, which is sensitive to rotor parameter variations.

Table 7.

Comparative assessment of the efficiency of the proposed method with various control strategies.

In the hybrid PLL-based FOC method, the estimation of the rotor magnetic flux angle is based on phase-locked loop (PLL) synchronization. The high accuracy of the hybrid PLL-based FOC approach is attributed to the precise tuning of the PLL.

6. Conclusions

This work proposes a concept for improving the energy efficiency of a traction drive by adapting an FOC system to the locomotive operating speed.

From analyzing the causes of increased power losses in a locomotive traction drive with FOC-controlled induction motors, it was established that a fixed inverter PWM switching frequency at motor shaft rotational speeds below the rated value leads to a reduction in power losses associated with higher-order harmonics of the stator current, while simultaneously increasing switching losses. Conversely, at shaft rotational speeds exceeding the rated value, a fixed PWM switching frequency results in increased power losses due to higher-order harmonics of the stator current.

To minimize power losses in the traction drive, it is proposed to adapt the parameters of the FOC system to the frequency of the speed change function generator, which is proportional to the locomotive operating speed.

To achieve this objective, the following tasks were performed:

- The selection of controller tuning methods for maximizing the performance of the baseline FOC IM system was substantiated. The absolute value optimum (AVO) was adopted for the current and flux control loops, while the symmetric optimum (SO) was applied to the speed control loop.

- Analytical relationships were derived, and the parameters of the controllers and filters for the current, flux-linkage, and speed control loops of the baseline FOC IM system were calculated.

- As a result of simulation modeling, the transient responses of each control loop were obtained, and the corresponding transient performance indices were evaluated. These results confirm the correctness of the controller tuning using the AVO method for the current and flux-linkage loops and the SO method for the speed loop.

- Methods for adapting the parameters of the controllers and filters of the baseline FOC IM system to the locomotive operating speed were proposed.

- An inverter control scheme was proposed that enables adaptation of the controller parameters of the baseline FOC IM system to the locomotive operating speed. The proposed scheme is based on adapting the PWM switching frequency to the signal generated by the speed change function generator.

- A filter structure was developed that allows the filter parameters of the baseline FOC IM system to be adapted to the locomotive operating speed.

- Based on a comparison of the simulation results of the baseline and adaptive FOC IM systems, the effectiveness of the proposed technical solutions was demonstrated.

Future research will focus on investigating the impact of electrical and mechanical disturbances on the energy efficiency of the proposed traction drive control system, as well as on optimizing controller tuning strategies under such disturbances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and I.D.; methodology, S.G. and I.D.; software, S.G. and I.D.; validation, S.G. and I.D.; formal analysis, S.G. and I.D.; investigation, S.G. and I.D.; resources, S.G., I.D. and L.N.; data curation, S.G., I.D. and L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.L., S.G., I.D., L.N., A.K. and V.D.; writing—review and editing, V.L., S.G., I.D., L.N., A.K. and V.D.; visualization, S.G. and I.D.; supervision, V.L. and S.G.; project administration, V.L. and S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bednář, O.; Čečrdlová, A.; Kadeřábková, B.; Řežábek, P. Energy Prices Impact on Inflationary Spiral. Energies 2022, 15, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruç, E.; Solmaz, A.R.; İnce, M.R.; Kılınç, Y. Oil Prices, Financial Development, and Urbanization in the Renewable Energy Transition: Empirical Evidence from E-10 Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Oleksy-Gębczyk, A.; Ciuła, J.; Cembruch-Nowakowski, M.; Peter-Bombik, K.; Rydwańska, P.; Zacłona, T. Energy Transformation Within the Framework of Sustainable Development and Consumer Behavior. Energies 2025, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powroźnik, P.; Szcześniak, P. Predictive Analytics for Energy Efficiency: Leveraging Machine Learning to Optimize Household Energy Consumption. Energies 2024, 17, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, G.; Mikulik, J.; Lewicki, W.; Niekurzak, M. Assessment of the Energy Efficiency of Individual Means of Transport in the Process of Optimizing Transport Environments in Urban Areas in Line with the Smart City Idea. Energies 2025, 18, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenna, M.; Bucci, V.; Falvo, M.C.; Foiadelli, F.; Ruvio, A.; Sulligoi, G.; Vicenzutti, A. A Review on Energy Efficiency in Three Transportation Sectors: Railways, Electrical Vehicles and Marine. Energies 2020, 13, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, N.; Wu, K. Energy Consumption and Energy Efficiency of the Transportation Sector in Shanghai. Sustainability 2014, 6, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Durlik, I.; Kostecka, E.; Łobodzińska, A.; Matuszak, M. The Emerging Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Energy Efficiency and Reducing GHG Emissions in Transport Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnci, M.; Çelik, Ö.; Lashab, A.; Bayındır, K.Ç.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. Power System Integration of Electric Vehicles: A Review on Impacts and Contributions to the Smart Grid. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuman, H. Modelling a DC Electric Railway System and Determining the Optimal Location of Wayside Energy Storage Systems for Enhancing Energy Efficiency and Energy Management. Energies 2024, 17, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, M.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, B.; Zou, J. High-frequency Resonance Suppression of Railway Traction Power Supply System Based on the Combination of Single-Tuned and C-Type Filters. Recent Pat. Mech. Eng. 2024, 17, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Maiti, D.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Biswas, S.K. Optimized design coordination of a single phase static VAr compensator for AC railway traction. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 243, 111502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, I.; Overianova, L.; Iakunin, D.; Neshcheret, V.; Ivanov, K. Equipping suburban diesel-electric multiple unit with a hybrid power unit. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 11, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, I.; Kondratieva, L.; Overianova, L.; Iakunin, D.; Yeritsyan, B. Mathematical Model of the Traction System of an Electric Locomotive Equipped with an On-Board Energy Storage System. In Proceedings of the 27th International Scientific Conference on Transport Means, Palanga, Lithuania, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Milojević, S.; Stopka, O.; Kontrec, N.; Orynycz, O.; Hlatká, M.; Radojković, M.; Stojanović, B. Analytical Characterization of Thermal Efficiency and Emissions from a Diesel Engine Using Diesel and Biodiesel and Its Significance for Logistics Management. Processes 2025, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhevzhyk, O.; Potapchuk, I.; Horiachkin, V.; Raksha, S.; Bosyi, D.; Reznyk, A. Mathematical modelling of mixture formation in the combustion chamber of a diesel engine. Technol. Audit Prod. Reserves 2025, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Tian, Z. Energy-efficient train control incorporating inherent reduced-power and hybrid braking characteristics of railway vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 163, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Zhang, M. A new look at the shape characteristics of optimal speed profile for energy-efficient train control considering multi-train power flow. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2025, 34, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nold, M.; Corman, F. Increasing realism in modelling energy losses in railway vehicles and their impact to energy-efficient train control. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2024, 32, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butko, T.; Babanin, A.; Gorobchenko, A. Rationale for the type of the membership function of fuzzy parameters of locomotive intelligent control systems. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2015, 1, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorobchenko, O.; Holub, H.; Zaika, D. Theoretical basics of the self-learning system of intelligent locomotive decision support systems. Arch. Transp. 2024, 71, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Gulzar, M.M.; Khalid, M. A review on harmonic elimination and mitigation techniques in power converter based systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaciński, P.; Pepliński, M.; Muc, A.; Hallmann, D. Induction Motors Under Voltage Unbalance Combined with Voltage Subharmonics. Energies 2024, 17, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhu, X.; Tao, H. Traction power systems for electrified railways: Evolution, state of the art, and future trends. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2024, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knast, P.; Petrů, J.; Legutko, S.; Soos, L.; Pokusova, M.; Borecki, P. Methodology for comprehensive testing and optimization of gears for torsional strength. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 25, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, I.; Goolak, S.; Neduzha, L. An Estimation of the Energy Savings of a Mainline Diesel Locomotive Equipped with an Energy Storage Device. Vehicles 2024, 6, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslii, A.; Buriakovskyi, S.; Antonenko, R.; Gevrasov, V.; Maslii, A. Assessing the applicability of energy storage system for plug-in hybrid traction system in rail rolling stock. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2025, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.; Mazorra, L.; Villalba, I.; Navarro, G.; Nájera, J.; Lafoz, M. Power Smoothing in a Wave Energy Conversion Using Energy Storage Systems: Benefits of Forecasting-Enhanced Filtering for Reduction in Energy Storage Requirements. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Panikkar, P.P.K. A comprehensive review of different electric motors for electric vehicles application. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. 2024, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M. A Review of Recent Trends in High-Efficiency Induction Motor Drives. Vehicles 2025, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Z. Direct Field-Oriented Control of Induction Motor with Discrete Full-Order Flux Observer. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 9416–9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolak, S.; Liubarskyi, B.; Riabov, I.; Lukoševičius, V.; Keršys, A.; Kilikevičius, S. Analysis of the Efficiency of Traction Drive Control Systems of Electric Locomotives with Asynchronous Traction Motors. Energies 2023, 16, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshbib, M.; Abdulkerim, S. Empirical Advancements in Field Oriented Control for Enhanced Induction Motor Performance in Electric Vehicle. Celal Bayar Univ. J. Sci. 2024, 20, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasri, A.; Ouari, K.; Belkhier, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Zaitsev, I. Optimizing electric vehicle powertrains peak performance with robust predictive direct torque control of induction motors: A practical approach and experimental validation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goolak, S.; Liubarskyi, B.; Riabov, I.; Chepurna, N.; Pohosov, O. Simulation of a direct torque control system in the presence of winding asymmetry in induction motor. Eng. Res. Express 2023, 5, 025070–025086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatte, Y. Torque ripple reduction with modified torque comparator in direct torque-controlled induction motor. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 4045–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbudak, O.; Gokdag, M.; Komurcugil, H. Model predictive control strategy for induction motor drive using Lyapunov stability objective. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 12119–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdali, E.; Rivera, M.; Wheeler, P. A review on weighting factor design of finite control set model predictive control strategies for ac electric drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 9967–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhou, J.; Qian, W.; Wang, B.; Zhao, C.; Han, P. Advanced electrical motors and control strategies for high-quality servo systems-a comprehensive review. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2024, 10, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinolova, P.; Ruseva, V.; Dinolov, O. Energy efficiency of induction motor drives: State of the art, analysis and recommendations. Energies 2023, 16, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. Comprehensive Analysis of FOC, MPC, and DTC Controlling Methods for Five-Phase Induction Motor Drives using Two-Level and Three-Level Inverters. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. (IJRASET) 2025, 13, 5054–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.G.M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Ali, Z.M.; Diab, A.A.Z. A Comprehensive examination of vector-controlled induction motor drive techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoke, E.; Szabo, C.; Pintilie, L.N. Artificial Intelligence-Based Sensorless Control of Induction Motors with Dual-Field Orientation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.D.A.; Cale, J.; Shahroudi, K.E. Rotor position synchronization in central-converter multi-motor electric actuation systems. Energies 2021, 14, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Lima, C.; Cale, J. Control Design for Position Synchronization in Central Converter Multi-Machine Actuators. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Tenerife, Spain, 19–21 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.W.; Tung, P.C. A New Approach to Field-Oriented Control That Substantially Improves the Efficiency of an Induction Motor with Speed Control. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megrini, M.; Gaga, A.; Mehdaoui, Y.; Khyat, J. Design and PIL test of extended Kalman filter for PMSM field-oriented control. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, M.; Naoui, M.; Mansouri, A. PMSM Inter-Turn Short Circuit Fault Detection Using the Fuzzy-Extended Kalman Filter in Electric Vehicles. Electronics 2023, 12, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hung, V.; Yoon, K.K.; Lee, S.G. Improved sliding mode observer for FOC control system with discontinuous PWM of sensorless PMSM. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. (JAMET) 2023, 47, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zou, X.; Li, J. Sensorless control strategy of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on fuzzy sliding mode observer. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36743–36752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Jaimes, V.; Coronel-Escamilla, A.; Escobar-Jiménez, R.F.; Adam-Medina, M.; Guerrero-Ramírez, G.V.; Sánchez-Coronado, E.M.; García-Morales, J. Fractional-order sliding mode observer for actuator fault estimation in a quadrotor UAV. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujeeth, A.; Di Cataldo, A.; Tornello, L.D.; Pulvirenti, M.; Salvo, L.; Sciacca, A.G.; Scelba, G.; Cacciato, M. Power Loss Modelling and Performance Comparison of Three-Level GaN-Based Inverters Used for Electric Traction. Energies 2024, 17, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusser, C.A.; Parra, M.; Mino-Aguilar, G.; Gonzalez-Diaz, V.R. Comparison of Induction Machine Drive Control Schemes on the Distribution of Power Losses in a Three-Level NPC Converter. Machines 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Dong, Q.; Sun, J.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; Goh, H.H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, D. Iron Loss in Electrical Machine—Influencing Factors, Model, and Measurement. Prog. Electromagn. Res. B 2024, 107, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörée, G.; Leijon, M. Iron loss models: A review of simplified models of magnetization losses in electrical machines. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 609, 172163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, Y.R.; Ponnaganti, V.K.; Reddy, P.V.S.; Singh, R.R.; Mercorelli, P.; Gundabattini, E.; Solomon, D.G. Thermal Analysis and Cooling Strategies of High-Efficiency Three-Phase Squirrel-Cage Induction Motors—A Review. Computation 2024, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shao, Y.; Long, Y.; He, X.; Wu, K.; Cai, L.; Wu, J.; Fang, Y. Methods for the Viscous Loss Calculation and Thermal Analysis of Oil-Filled Motors: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubarevych, O.; Wierzbicki, S.; Melnyk, O.; Kyrychenko, O.; Riashchenko, O. Increasing the accuracy of calculated indicators of operational reliability of industrial electric motors. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.—Maint. Reliab. 2025, 27, 203006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolak, S.; Kyrychenko, M. Thermal Model of the Output Traction Converter of an Electric Locomotive with Induction Motors. Probl. Energeticii Reg. 2022, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolak, S.; Riabov, I.; Tkachenko, V.; Yeritsyan, B. The Determination of Power Losses in the Traction Electric Drive Converter of the Electric Locomotive. In Proceedings of the 26th International Scientific Conference on Transport Means, Kaunas, Lithuania, 5–7 October 2022; pp. 487–492. [Google Scholar]