1. Introduction

In recent decades, the adoption of climate-friendly technologies—particularly in the transportation sector—has accelerated due to growing concerns about climate change, air quality, and the need to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions [

1]. In this context, electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as an effective and increasingly mature alternative to internal combustion engine vehicles, contributing to reduced fossil-fuel dependence and lower urban pollution levels [

2]. However, the large-scale integration of EVs also introduces nontrivial technical challenges for power distribution networks, especially in terms of maintaining acceptable voltage levels under highly variable and concentrated charging demand [

3].

EV charging represents a highly volatile, time-dependent, and spatially clustered electrical load. When deployed at scale, especially in urban areas, this additional demand can distort nodal voltage profiles and increase the risk of sustained under-voltage conditions during peak hours [

4]. These effects are often exacerbated in distribution systems characterized by radial topology, long feeders, aged infrastructure, and limited short-circuit strength, which are common features of many existing networks worldwide [

5]. Consequently, distribution system operators face the challenge of accommodating rapidly growing EV charging demand without compromising service quality, regulatory compliance, or system security.

In recent years, EV charging technology itself has evolved rapidly toward higher power levels. While early fast chargers operated in the 50–150 kW range, modern ultra-fast charging stations commonly deliver 150–350 kW, and emerging platforms are targeting power levels approaching or exceeding 1 MW per charging point. Such ultra-fast chargers are typically based on power-electronic converters operating under constant-current (CC) and constant-voltage (CV) charging stages, which implies that the instantaneous active power and effective power factor may vary during a charging session. From a grid perspective, this behavior can translate into large and rapidly coincident power injections with non-negligible reactive demand, intensifying steady-state voltage stress at specific network locations. These characteristics make ultra-fast charging fundamentally different from conventional residential or commercial loads and motivate dedicated assessment methodologies.

From a regulatory standpoint, maintaining voltage within permissible limits is a core requirement for distribution network operation. Although exact thresholds depend on national standards, long-term steady-state voltage deviations are commonly restricted to bands on the order of to around nominal values. As a result, planning-oriented studies often adopt conservative screening criteria such as a minimum voltage of 0.95 p.u. to identify potential compliance violations and operational risk under normal operating conditions. In the context of high-power EV charging, sustained excursions below this threshold are of particular concern, as they may affect sensitive equipment, reduce power quality, and trigger corrective actions.

Given the inherent uncertainty associated with EV user behavior, charging coincidence, and background demand variability, probabilistic simulation has become a key tool for assessing the impact of EV integration on distribution-system voltage performance. Among available approaches, the Monte Carlo method has been widely adopted to model stochastic demand patterns and to evaluate EV charging under multiple operating scenarios [

6]. By sampling realistic variations in both load and charging activation, Monte Carlo-based assessments provide a more representative picture of voltage-risk exposure over daily operation than deterministic worst-case snapshots.

1.1. Literature Review

A substantial body of research has investigated the effects of EV penetration on voltage performance in distribution networks. Early studies such as [

7] demonstrate that uncontrolled EV charging can trigger significant voltage fluctuations and, in electrically weak buses, may even lead to critical voltage instability if mitigation strategies are not implemented. Similarly, the work in [

8] analyzes EV penetration under different demand levels and demand-side management strategies, concluding that coordinated charging and load shifting can effectively reduce voltage deviations.

Other contributions emphasize the relevance of probabilistic tools for capturing uncertainty. The authors of [

9] analyze EV integration using Monte Carlo-based charging patterns and show that voltage regulation improves when dynamic reactive compensation and load-management schemes are incorporated. Likewise, ref. [

10] highlights the importance of stochastic approaches to model variability in EV charging profiles and to support robust multi-scenario evaluation. The Monte Carlo formulation proposed in [

11] explicitly accounts for EV location, charging demand, and time-of-use behavior, demonstrating that charging uncertainty introduces significant voltage volatility that must be addressed through appropriate mitigation measures.

Monte Carlo-based evaluations have been applied to both rural and urban networks. In [

12], the authors conclude that distribution systems with higher operational flexibility and storage capability exhibit greater resilience to EV integration. The study in [

13] investigates IEEE benchmark feeders under 30%, 50%, and 70% EV penetration, reporting increased power losses and marked voltage-profile degradation as penetration grows while also quantifying associated environmental benefits. Analytical approaches have further explored voltage-support mechanisms in EV-rich systems. For example, ref. [

14] derives analytical relationships between EVs and microgrids and applies eigenvalue-based monitoring to show that coordinated EV integration can, under certain conditions, improve voltage profiles.

Comprehensive reviews such as [

15] summarize power-quality challenges associated with EV charging, including voltage imbalance, harmonic distortion, and transformer thermal stress, and discuss mitigation solutions such as active filters and FACTS devices. Advances in the spatio-temporal modeling of EV demand are reported in [

16], where coupled vehicle–load–road frameworks reveal that high charging density can cause localized voltage drops. Real-network studies, including [

17], confirm that penetration levels around 40% may lead to under-voltage violations and line overloads, motivating sensitivity-based reactive compensation. Additional probabilistic and coordinated-charging studies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] consistently indicate that voltage risk increases with penetration, while mitigation through smart charging and reactive support becomes increasingly important.

Despite these extensive contributions, two practical gaps remain. First, many studies quantify voltage degradation under EV penetration but do not explicitly address the robust placement of ultra-fast charging stations based on network sensitivity characteristics. Second, reactive support is often determined through iterative optimization or heuristic techniques, which may be computationally intensive or opaque for planning-stage studies. These gaps motivate the development of probabilistic, sensitivity-guided methodologies that simultaneously account for charging uncertainty, placement robustness, and targeted voltage support.

1.2. Problem Statement and Contributions

The growing penetration of ultra-fast EV charging stations in distribution grids poses a significant technical challenge for maintaining steady-state voltage compliance [

23]. In particular, the simultaneous operation of multiple high-power chargers may induce substantial voltage drops at specific buses, jeopardizing adherence to typical operational limits (e.g.,

p.u.) even under a normal network topology.

In this study, steady-state voltage performance is assessed through the behavior of the minimum system voltage over a 24 h operating horizon, explicitly accounting for uncertainty in both residential demand and EV charging activation. To this end, a Monte Carlo framework is employed to generate multiple hourly operating scenarios and to compute statistically meaningful voltage indicators. In parallel, a voltage–reactive power (V–Q) sensitivity analysis based on the coefficients is used to (i) identify electrically robust buses for the installation of ultra-fast chargers and (ii) estimate the reactive power required to mitigate under-voltage conditions when they arise.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

A probabilistic, hourly assessment of steady-state voltage performance in an IEEE 33-bus radial distribution system under uncertain residential load and stochastic ultra-fast EV charging.

A sensitivity-based criterion for locating EV charging stations at the most robust buses using auto-sensitivity indices .

A direct, closed-form reactive compensation scheme derived from V–Q sensitivity to support critical buses and alleviate under-voltage conditions without iterative optimization.

A comparative evaluation of two penetration levels (6 and 12 charging points) and two charging-power ratings (1 MW and 350 kW), quantifying their impact on voltage performance and reactive-support requirements.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the Monte Carlo formulation adopted for uncertainty modeling.

Section 3 presents the proposed methodology, including sensitivity analysis and compensation strategy.

Section 4 discusses the numerical results for all penetration and power scenarios. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and delineates the scope and applicability of the proposed approach.

4. Results

This section summarizes the numerical results of the proposed probabilistic voltage-assessment framework. First, the V–Q nodal sensitivity ranking is reported to justify charger siting. Next, the four charging scenarios are analyzed in terms of minimum-hourly voltage, critical buses, and the required sensitivity-guided reactive compensation. Finally, a compact cross-case summary is provided to highlight the influence of charger rating and penetration level on voltage compliance.

4.1. Nodal Sensitivity Analysis

Nodal V–Q sensitivity indicates how strongly each PQ bus voltage responds to incremental reactive-power changes. The auto-sensitivity index measures the voltage variation at a bus when reactive power is injected at that same bus. Hence, smaller values denote higher robustness, because the bus experiences weaker voltage deviations for a given reactive perturbation. This property makes low-sensitivity buses technically preferable for connecting large EV charging loads.

Figure 2 shows the auto-sensitivity values for all PQ buses of the IEEE 33-bus feeder. The lowest sensitivities are concentrated in the central–southern portion of the network, identifying electrically strong locations.

From this ranking, the robust buses selected for EV charger placement are as follows:

Cases 1 and 3 (6 chargers): buses 2, 19, 3, 4, 23, 5.

Cases 2 and 4 (12 chargers): buses 2, 19, 3, 4, 23, 5, 24, 6, 20, 26, 27, 21.

Table 1 provides the full sorted list of buses by auto-sensitivity. This classification substantiates the siting strategy for the subsequent probabilistic simulations.

Overall, the sensitivity study confirms that robust-bus siting reduces the intrinsic vulnerability of the feeder to EV charging, but it does not by itself guarantee immunity to under-voltage under high-power, high-penetration conditions. This motivates the compensation analysis below.

4.2. Case 1: 6 Robust Buses, 1 MW Chargers

Case 1 evaluates moderate EV penetration using six ultra-fast chargers located at the most robust buses (2, 19, 3, 4, 23, 5). Each charger is rated at 1 MW. The objective is to quantify the resulting minimum-voltage degradation and test the proposed sensitivity-based compensation.

4.2.1. Hourly Minimum-Voltage Behavior

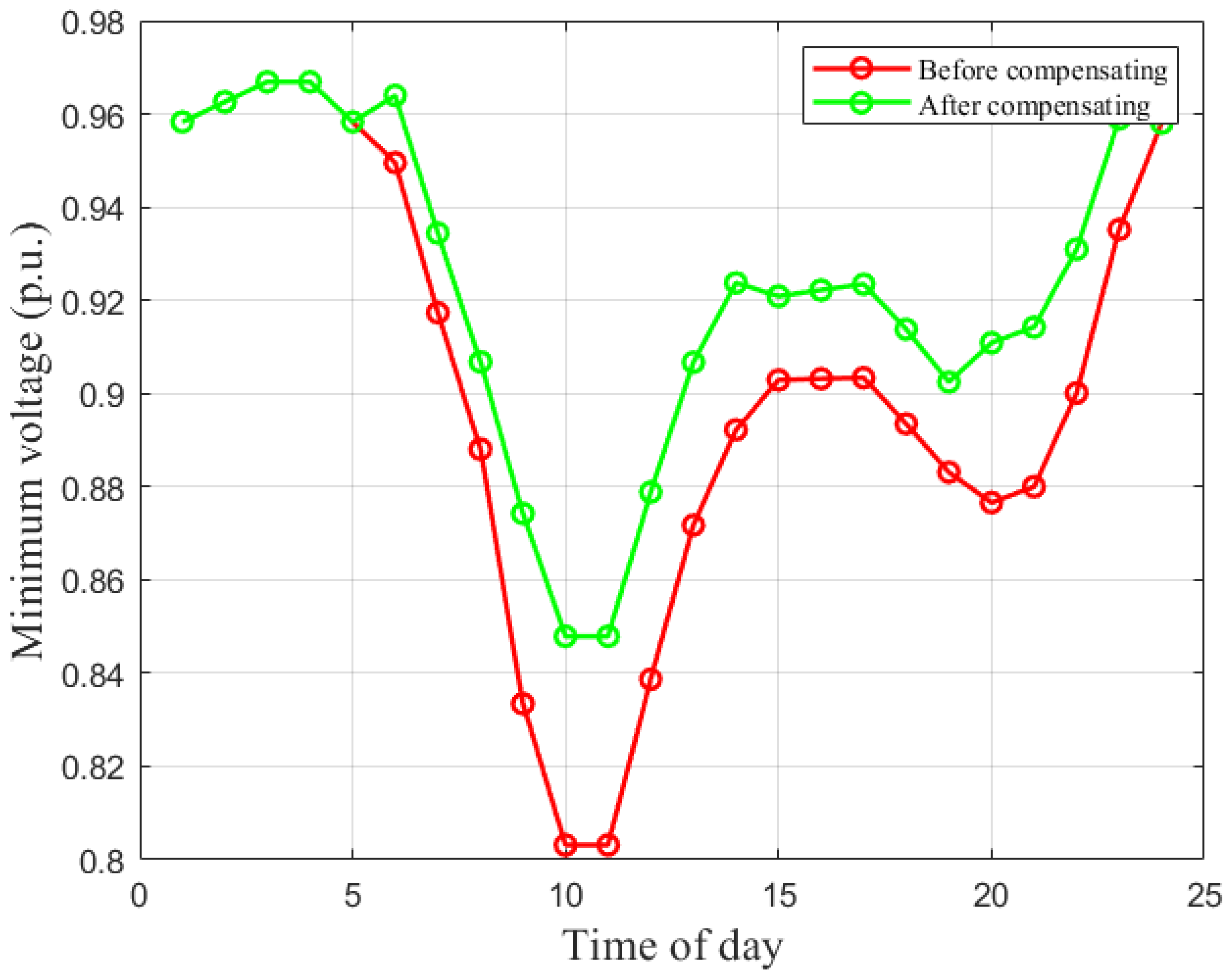

Figure 3 compares the hourly minimum system voltage before and after applying nodal compensation. Without compensation, the minimum voltage violates the 0.95 p.u. limit from hour 7 to hour 22, reaching a nadir of 0.881 p.u. at hour 11. Such a sustained infravoltage interval reflects the strong aggregated demand imposed via simultaneous 1 MW charging, even when chargers are connected to robust buses.

After injecting reactive support at the critical bus of each hour, the minimum-voltage profile improves substantially. Although the system does not recover to exactly 1 p.u., the compensated minimum remains in an acceptable range (above ≈0.926 p.u. at the most stressed hours), demonstrating effective mitigation.

4.2.2. Reactive Compensation Summary

Table 2 reports the stressed hours and the reactive injection required to restore voltage. Bus 18 is consistently the critical location. The required

ranges from 1.56 to 2.61 Mvar, with the highest demand aligned with the daytime load peak. Negative values correspond to capacitive support in MATPOWER convention.

This case confirms that robust placement reduces but does not eliminate voltage violations under 1 MW ultra-fast charging; however, the proposed local compensation restores feasibility efficiently.

4.3. Case 2: 12 Robust Buses, 1 MW Chargers

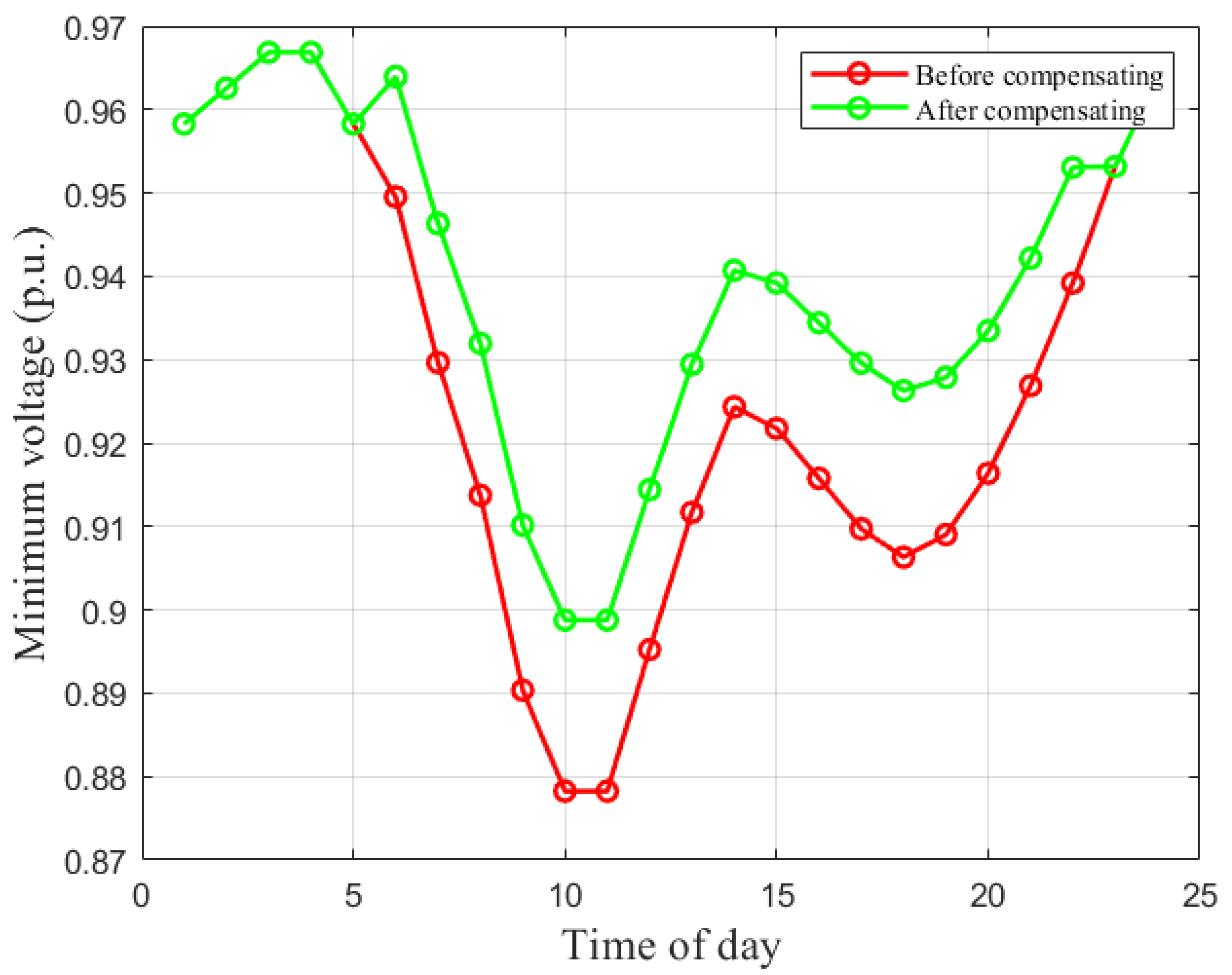

Case 2 represents high penetration (12 ultra-fast chargers) at the most robust buses. Each unit is rated at 1 MW. This scenario stresses the feeder under dense ultra-fast charging.

Figure 4 shows that uncompensated minimum voltages collapse below 0.85 p.u. at peak hours (9–11), reaching about 0.803 p.u. Such values are close to a static voltage-collapse regime for radial feeders. With compensation, the minimum profile is lifted above 0.90 p.u. across the critical interval, validating the mitigation principle, although full recovery to 1 p.u. is limited by the magnitude of the aggregated load and network topology.

Table 3 shows that the critical bus shifts between buses 18 and 33. Under dense charging, the feeder-end bus (33) becomes dominant during the most stressed hours, requiring up to 6.35 Mvar of capacitive support.

Therefore, Case 2 evidences that high ultra-fast charging density can drive severe under-voltage and relocate weakness toward the feeder tail.

4.4. Case 3: 6 Robust Buses, 350 kW Chargers

Case 3 keeps the same moderate penetration (six chargers) but reduces unit power to 350 kW. This isolates the effect of charger rating on steady-state voltage compliance.

Figure 5 indicates that uncompensated voltages still fall below 0.95 p.u. during daytime peaks, but the valley is shallower than in Case 1 (minimum around 0.902 p.u.). Compensation restores the minimum to roughly 0.93–0.94 p.u. in the stressed interval, confirming improved resilience at lower ratings.

As reported in

Table 4, the critical bus remains bus 18, yet the reactive support needed decreases, peaking at 2.29 Mvar.

4.5. Case 4: 12 Robust Buses, 350 kW Chargers

Case 4 combines high penetration (12 chargers) with the reduced unit rating of 350 kW.

Figure 6 shows sustained under-voltage from hours 6 to 22 in the uncompensated profile, with the minimum reaching 0.878 p.u. at hour 10. Although the violation is less severe than Case 2, it confirms that high penetration alone is sufficient to drive instability even at moderate power levels. Compensation lifts the valley to about 0.90–0.94 p.u.

Table 5 indicates that bus 18 remains the critical location and requires up to 2.66 Mvar, clearly below the peak need observed for 1 MW chargers.

4.6. Cross-Case Summary and Discussion

To provide a compact view of the main system-level effects,

Table 6 compares the four scenarios using three stability indicators: (i) the minimum uncompensated voltage across the day, (ii) the minimum compensated voltage across the day, and (iii) the maximum reactive support required in any hour. These indicators are consistent with the profiles and hourly compensation tables reported above.

Two consistent trends emerge:

Effect of penetration: Increasing the number of chargers from 6 to 12 deepens the voltage valley and increases the required reactive support. Under 1 MW charging, this shift is particularly severe (Case 2), and the weakest bus migrates toward the feeder end (bus 33).

Effect of charger rating: Reducing the unit rating from 1 MW to 350 kW mitigates under-voltage and lowers compensation needs at both penetration levels. The improvement is evident when comparing Case 1 vs. Case 3 (moderate penetration) and Case 2 vs. Case 4 (high penetration).

These results confirm that robust bus-siting and sensitivity-guided local reactive compensation are complementary: siting reduces baseline vulnerability, while compensation ensures operational feasibility under stochastic high-demand charging. Moreover, limiting ultra-fast charger ratings (or enforcing smart charging profiles) appears as a practical planning lever to preserve steady-state voltage compliance in distribution feeders with increasing EV adoption.

4.7. Confidence Intervals of Minimum Voltage

Beyond mean voltage trajectories, confidence intervals (CIs) are used to quantify the statistical dispersion of the minimum system voltage under uncertainty. For each hour,

h, the

confidence interval of the minimum voltage is computed using the Monte Carlo estimators defined in

Section 2, specifically (

2)–(

4).

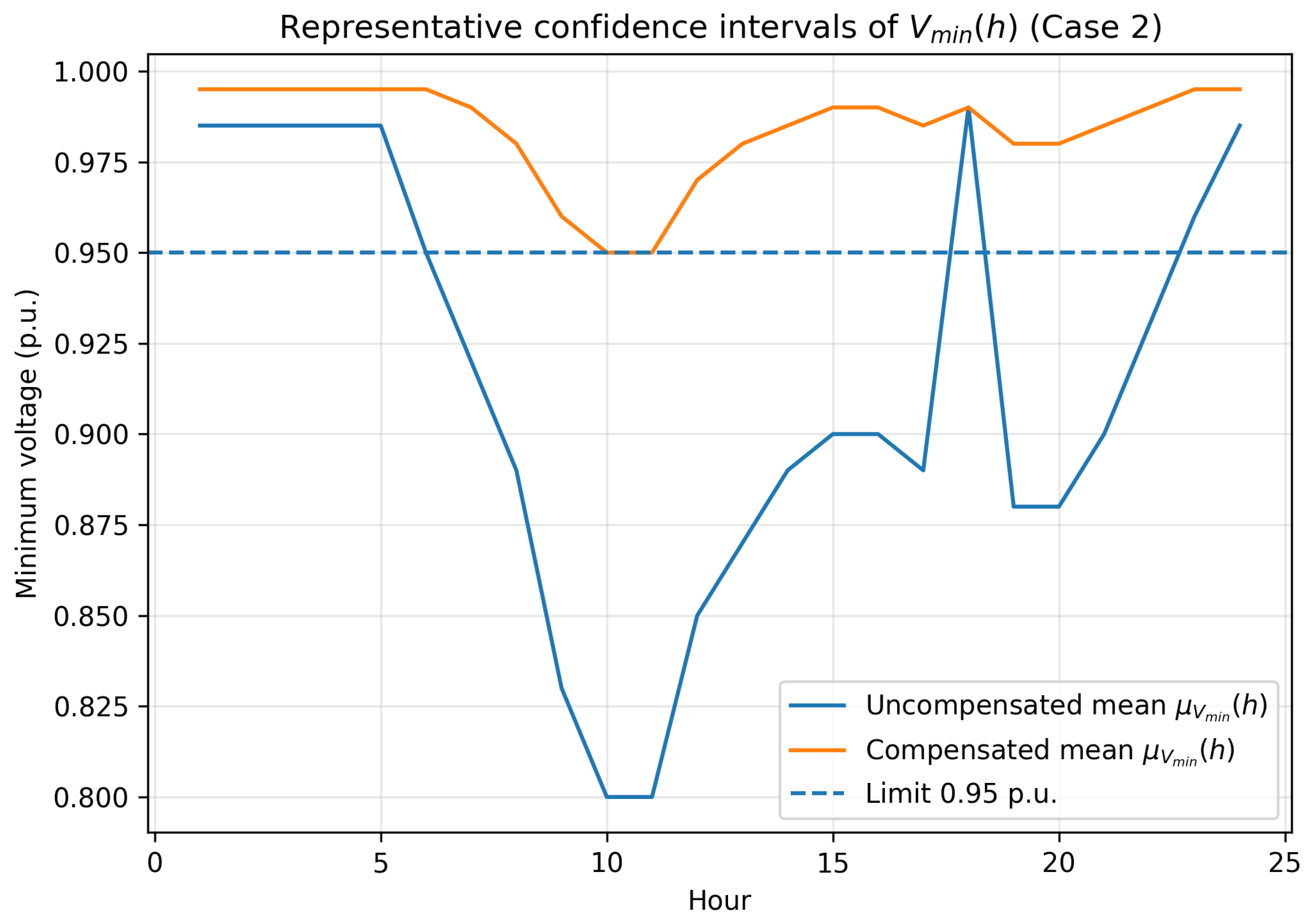

Figure 7 illustrates a representative case in which the expected hourly minimum voltage,

, is reported together with its corresponding confidence band. The CI width increases during peak-stress hours, reflecting higher variability caused by coincident residential demand and stochastic EV charging activation. After applying sensitivity-guided reactive compensation, both the mean trajectory and the CI band are shifted upward, indicating not only voltage recovery but also a reduction in statistical dispersion. This confirms that the proposed mitigation improves voltage robustness under uncertainty, rather than correcting isolated deterministic outliers.

4.8. Hourly Probability of Under-Voltage Violation

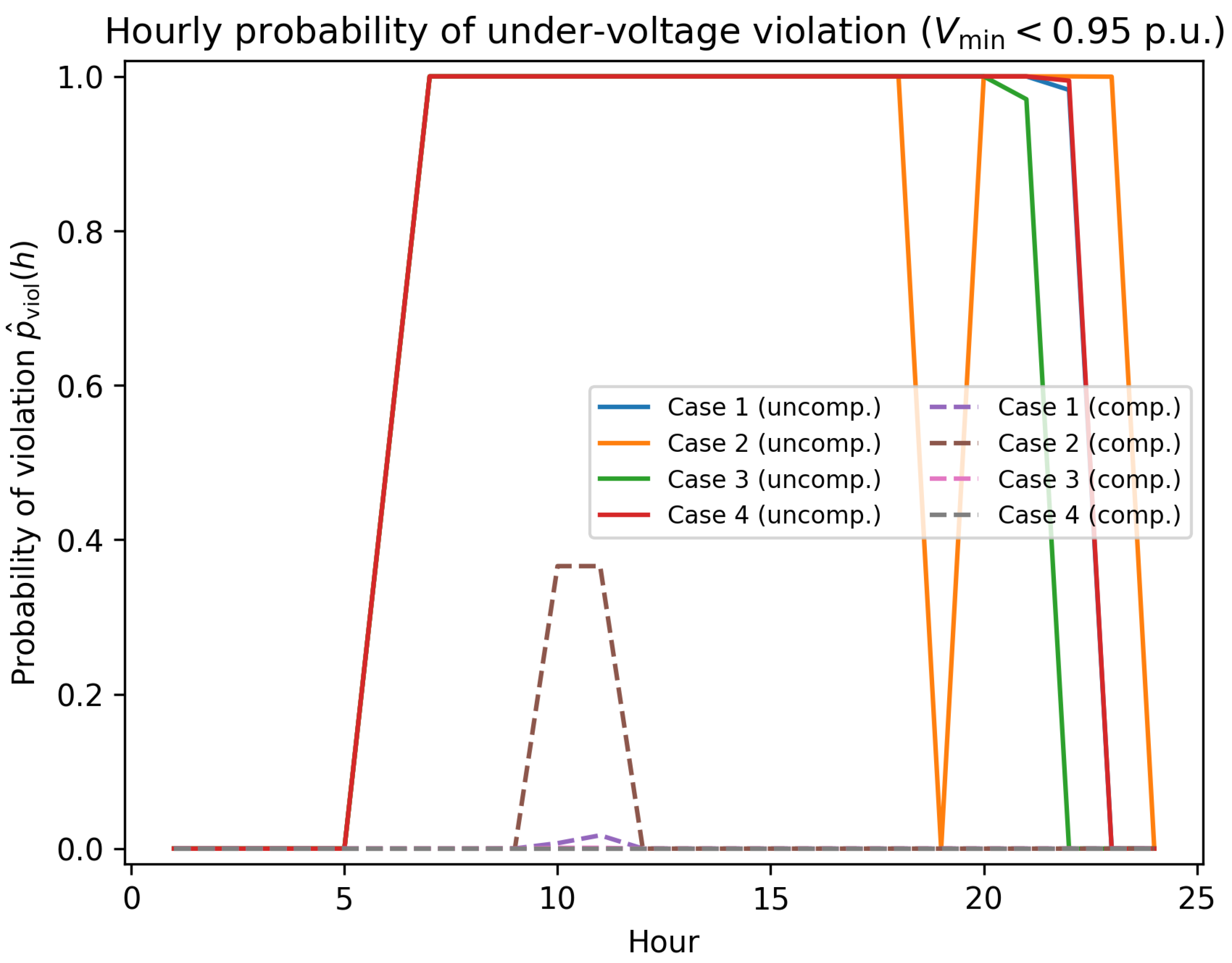

To complement mean-based indicators, the probability of under-voltage violation is evaluated for each hour using the estimator defined in (

16). This metric represents the fraction of Monte Carlo realizations for which the minimum system voltage falls below the admissible threshold of 0.95 p.u.

Figure 8 reports the hourly probability of violation for the four charging scenarios, both before and after compensation. In the uncompensated cases, violation probabilities approach unity during peak hours under high penetration and high charger power, indicating that under-voltage is not an isolated event but a highly probable operating condition. Conversely, after compensation, the probability of violation is substantially reduced across all scenarios, with the most pronounced improvement observed for the 350 kW charging cases. These results demonstrate that the proposed compensation strategy mitigates voltage risk in a probabilistic sense by reducing both the likelihood and persistence of under-voltage events.

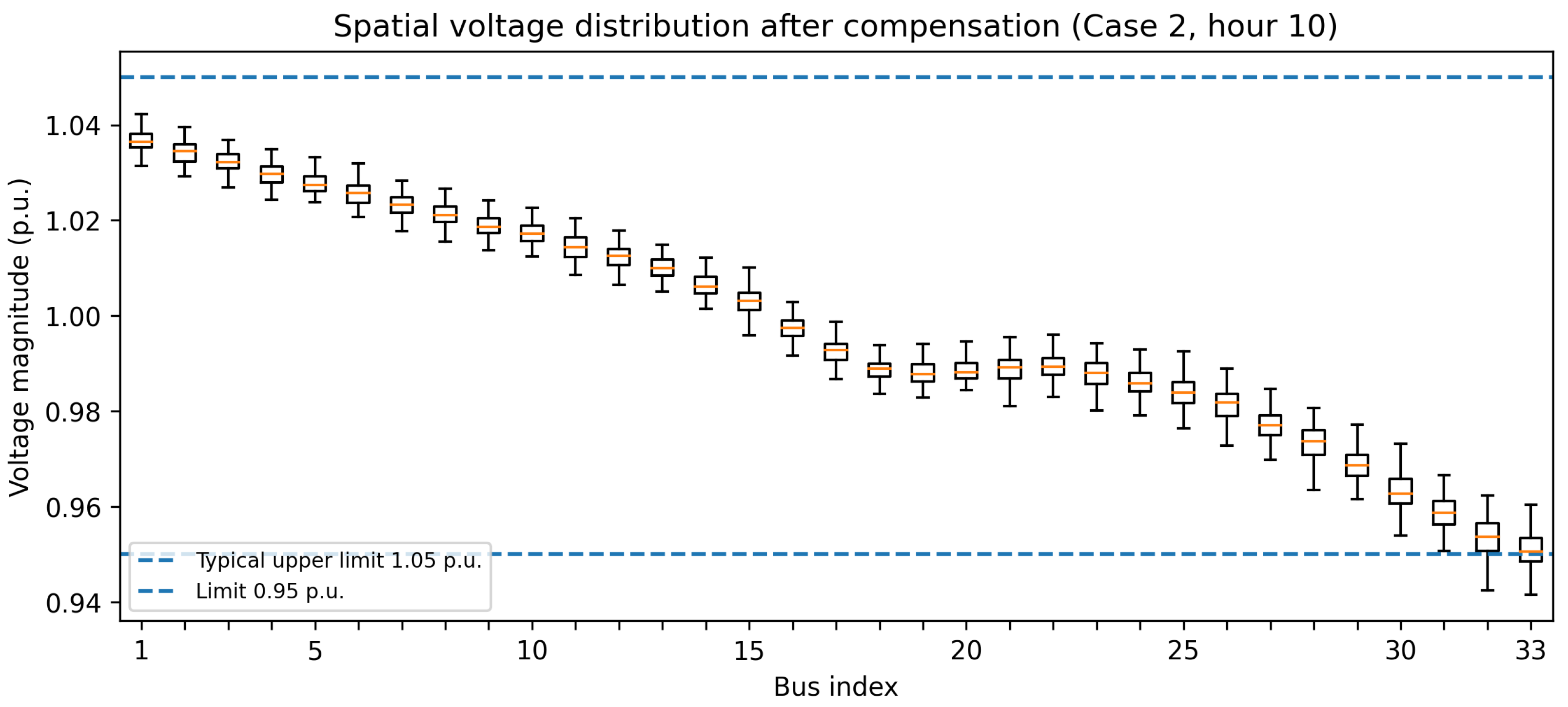

4.9. Spatial Voltage Distribution After Compensation

While the compensation strategy is designed to improve the minimum system voltage, it is also necessary to verify that localized reactive support does not introduce over-voltage conditions at other buses. To this end, the spatial distribution of nodal voltages across the feeder is examined after compensation during representative peak-stress hours.

Figure 9 presents the spatial distribution of nodal voltages using boxplots obtained from Monte Carlo realizations. The results confirm that, although voltages at the weakest buses are lifted toward the admissible range, voltages at upstream and electrically strong buses remain well below typical upper operational limits (commonly 1.05–1.10 p.u., depending on the grid code). This observation indicates that the proposed sensitivity-guided compensation acts locally and proportionally, improving the weakest nodes without inducing widespread over-voltage conditions elsewhere in the feeder. Therefore, the method preserves overall voltage-profile integrity while addressing the most critical locations.

4.10. Summary of Probabilistic Performance Indicators

Taken together, the confidence intervals, violation probabilities, and spatial voltage distributions provide a comprehensive probabilistic characterization of voltage performance under ultra-fast EV charging. These indicators complement the earlier reported mean trajectories and confirm that the proposed methodology improves steady-state voltage compliance margins not only in expectation but also in terms of dispersion control and risk reduction, thereby enhancing the robustness of distribution networks under stochastic high-power EV charging.

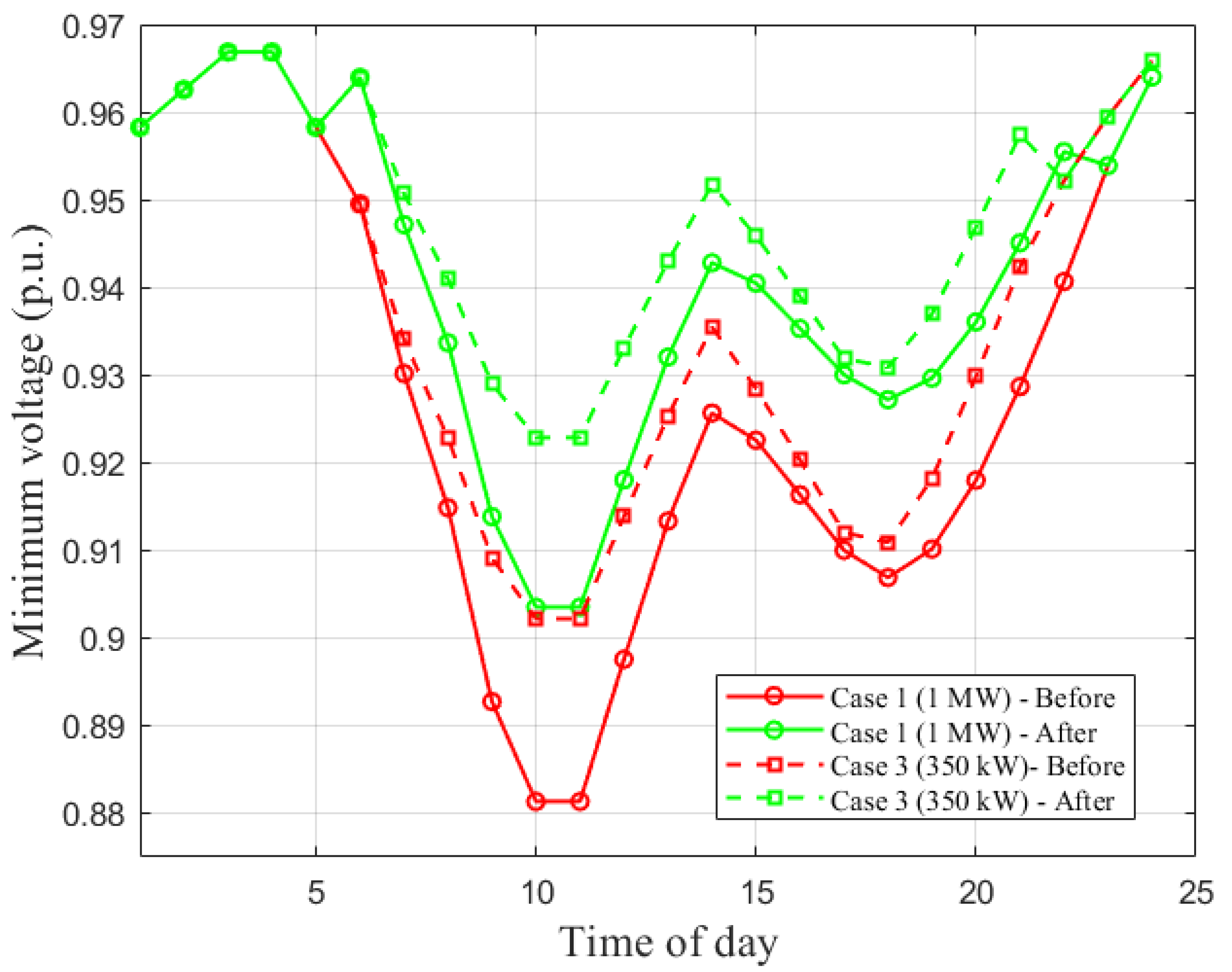

4.11. Comparison of Case 1 vs. Case 3 (6 Chargers)

Figure 10 contrasts moderate-penetration scenarios. Both cases exhibit their deepest drop around hours 9–11, but Case 3 (350 kW) increases the uncompensated minimum from 0.881 p.u. to 0.902 p.u. and yields a higher compensated minimum. Therefore, lowering unit charger power reduces both the intensity and duration of voltage violations.

4.12. Comparison of Case 2 vs. Case 4 (12 Chargers)

Figure 11 compares high-penetration scenarios. Case 2 (1 MW) produces a minimum of ∼0.80 p.u., whereas Case 4 limits the minimum to 0.878 p.u. With compensation, Case 4 sustains higher voltages and requires substantially less reactive support, reinforcing the benefit of moderate-power charging under dense deployment.

5. Discussion

This section provides an in-depth interpretation of the results obtained from the probabilistic steady-state assessment and the sensitivity-guided reactive compensation framework. The discussion is structured to address both physical insight and engineering relevance, with explicit consideration of uncertainty, network characteristics, and practical deployment constraints. The analysis is organized around the following aspects: (i) the interpretation of V–Q sensitivity and charger placement, (ii) the combined impact of EV charging power and penetration levels, (iii) the role of uncertainty and Monte Carlo aggregation, (iv) the effectiveness and limitations of the proposed compensation strategy, (v) the physical feasibility of reactive support, and (vi) the scope and applicability of the proposed framework.

5.1. Interpretation of V–Q Sensitivity and Charger Placement

The nodal sensitivity analysis based on the voltage–reactive power coefficient provides a physically grounded indicator of how robust each bus is to reactive-power perturbations. Buses exhibiting low auto-sensitivity values correspond to locations where a given reactive-power change produces only a limited voltage deviation. In radial distribution systems, such buses are typically electrically closer to the slack/substation or embedded within stronger lateral branches characterized by lower equivalent impedance.

Consequently, selecting the least sensitive buses for the installation of ultra-fast EV charging stations is consistent with classical distribution-planning principles, whereby high-power loads are preferentially allocated to electrically stiff nodes. The ordered sensitivity values reported in

Table 1 clearly reveal a stratification between robust and weak buses along the feeder.

However, an important and nontrivial result emerges from the simulations: even when EV chargers are installed exclusively at the most robust buses, the minimum system voltage still violates the admissible threshold in all considered scenarios. This leads to two key practical insights. First, V–Q robustness is a necessary but not sufficient condition to guarantee voltage compliance under ultra-fast charging, as cumulative loading effects and feeder topology ultimately dominate voltage behavior. Second, the sensitivity-based ranking remains highly valuable because it delays the onset of under-voltage conditions and reduces their severity relative to random or uninformed placement. Thus, sensitivity-guided siting provides a rational and defensible baseline strategy, even though it must be complemented with additional mitigation measures under high-stress conditions.

5.2. Impact of EV Charging Power and Penetration Level

Across all investigated scenarios, a systematic relationship is observed between EV charging power, penetration levels, and voltage degradation. For a fixed number of charging points, reducing the unit charger rating from 1 MW to 350 kW consistently mitigates both the depth and duration of minimum-voltage sags. This trend is evident when comparing Case 1 versus Case 3 and Case 2 versus Case 4, for which lower charging power results in higher voltage minima and shorter under-voltage intervals.

This behavior is physically intuitive: in radial feeders, voltage drops scale with line impedance and current magnitude, which in turn depends primarily on active and reactive power injection. Lower charger ratings imply reduced current flow and therefore alleviate voltage stress along the feeder.

The penetration level exerts an equally strong influence. The 12-charger scenarios (Cases 2 and 4) represent high-density charging conditions and produce substantially deeper voltage valleys than the corresponding 6-charger cases, even when chargers are located at robust buses. These results confirm that distribution networks can accommodate moderate levels of ultra-fast charging only up to a certain spatial density, beyond which voltage compliance becomes contingent on additional control or infrastructure reinforcement.

From a planning perspective, the contrast between 6- and 12-node cases can be interpreted as representing intermediate versus advanced EV adoption stages. The results suggest that voltage compliance margins shrink rapidly with charging clustering, emphasizing the need for proactive coordination between EV infrastructure roll-out and voltage-support planning.

5.3. Role of Load Uncertainty and Monte Carlo Assessment

The Monte Carlo framework adopted in this work clarifies that voltage performance in EV-rich feeders cannot be adequately characterized by a single deterministic trajectory. Instead, voltage behavior emerges as a distribution of possible operating states driven by residential demand variability and stochastic EV charging activation.

Two important implications follow from this probabilistic perspective. First, the hours identified as most critical are consistent across Monte Carlo realizations, indicating that the network exhibits structurally vulnerable time windows where the coincidence of residential peaks and EV charging is recurrent, rather than accidental. Second, probabilistic aggregation yields smoother and more reliable indicators of voltage risk, filtering out isolated outliers and highlighting statistically persistent trends.

This is particularly relevant for planning studies, where decisions must be robust to uncertainty, rather than optimized for extreme or unlikely scenarios. The probabilistic metrics reported in

Section 4, including confidence intervals and violation probabilities, demonstrate that the proposed compensation strategy reduces not only the expected severity of voltage drops but also their likelihood of occurrence, reinforcing its practical relevance.

5.4. Effectiveness and Limitations of Sensitivity-Guided Reactive Compensation

The proposed compensation strategy leverages local V–Q auto-sensitivity to compute a closed-form estimate of the reactive power required to support the most critical bus at each hour. Across all scenarios, the compensated voltage profiles exhibit a clear upward shift of the minimum-voltage curve, reducing violation depth by several hundredths of per-unit and substantially improving voltage margins.

A notable and consistent pattern is that the same buses repeatedly emerge as critical locations, particularly bus 18 and, under the most stressed conditions, bus 33. This is not an artifact of the algorithm but, rather, a structural property of the IEEE 33-bus feeder, where electrically remote buses with high cumulative impedance and downstream loading are inherently more vulnerable. The compensation results, therefore, align closely with physical intuition and classical feeder analysis.

At the same time, compensation does not always restore voltages fully to 1 p.u., especially in the high-penetration, 1 MW charging scenario. This highlights an important operational interpretation: when active-power stress dominates, reactive support alone can lift voltages into an acceptable range but may not completely eliminate deviations. In such cases, complementary measures—such as coordinated charging, feeder reinforcement, or distributed generation—become necessary. The proposed method should, therefore, be viewed as an efficient corrective layer within a broader voltage-management strategy, rather than as a standalone solution.

5.5. Validity of the Linear V–Q Sensitivity Approximation

The compensation approach relies on a first-order linear approximation of the nonlinear power-flow equations, expressed through the voltage–reactive sensitivity coefficient

. Locally, the voltage response at a PQ bus can be approximated as

which represents the first-order truncation of the Jacobian-based formulation.

In this study, sensitivities are computed around the uncompensated operating point for each hour, and the resulting compensation is applied in a corrective (rather than predictive) manner. Although the required reactive injections may reach several Mvar in the most stressed scenarios, the objective is not to achieve exact restoration to 1 p.u. but to lift voltages into an acceptable operating band. The compensated results confirm that, despite the simplicity of the linear approximation, the voltage response remains monotonic and physically consistent, with no evidence of numerical instability or overcompensation.

Nevertheless, as increases, higher-order nonlinear effects may become relevant. For this reason, the proposed approach is best interpreted as a planning-stage, first-order tool. If larger voltage recovery is required, the same framework can be applied iteratively or complemented by coordinated charging and infrastructure reinforcement.

5.6. Physical Feasibility of Reactive Power Support

The magnitude of the computed reactive compensation in some scenarios (up to approximately 6.35 Mvar) raises legitimate questions regarding physical feasibility. In this work, the computed values represent an equivalent reactive-support requirement at the critical bus, rather than the output of a single physical device.

In practice, reactive support can be provided through a combination of switched capacitor banks, SVCs, STATCOMs, or inverter-based resources embedded within EV charging infrastructure. Modern ultra-fast chargers are interfaced through power-electronic converters capable of exchanging reactive power with the grid, subject to apparent-power limits. For an inverter rated at

and operating at active power

P, the available reactive capability is bounded by

Equation (

24) highlights that delivering large amounts of reactive power may require curtailment of active charging power during peak operation. This trade-off is not explicitly modeled here, as the focus is on quantifying voltage-support needs, rather than prescribing device-level control strategies. The results, therefore, indicate where and how much reactive support is required, leaving detailed allocation among physical resources as a subsequent design step.

5.7. Scope and Applicability of the Proposed Framework

Finally, it is essential to delineate the scope and limitations of the proposed Monte Carlo–sensitivity framework. The analysis is restricted to steady-state conditions and does not capture dynamic phenomena such as transient voltage dips, fast converter dynamics, control delays, or protection actions. The method is, therefore, not intended for dynamic voltage-stability assessment or post-fault analysis.

Moreover, the study focuses on a radial feeder operating under normal topology. Contingency conditions and reconfigured states are not considered and may lead to more severe voltage stress. Within these boundaries, the framework is particularly well suited for planning-stage and what-if analyses, enabling comparison of EV penetration levels, charger ratings, and siting strategies under uncertainty.

By explicitly acknowledging these limitations, the applicability boundaries of the proposed approach are clearly defined, ensuring that the results are interpreted within their intended engineering context.

From a quantitative perspective, the proposed sensitivity-based compensation strategy increased the minimum hourly voltage by approximately 0.03–0.12 p.u., depending on the EV penetration level and charger rating. In the most critical scenarios, the method reduced voltage-limit violations from values below 0.85 p.u. to levels closer to the regulatory threshold. The required equivalent reactive compensation ranged from approximately 2 Mvar in moderate-demand periods to about 6.35 Mvar during peak ultra-fast charging conditions, providing a compact numerical interpretation of the effectiveness observed in the hourly voltage profiles.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented a probabilistic steady-state voltage assessment of a radial distribution feeder subject to ultra-fast electric vehicle (EV) charging, integrating Monte Carlo simulation with voltage–reactive power (V–Q) sensitivity analysis. The main conclusions, derived directly from the numerical results obtained for the IEEE 33-bus test system, are summarized as follows.

First, ultra-fast EV charging introduces a pronounced risk of sustained under-voltage even when charging stations are connected exclusively to electrically robust buses. For the scenarios analyzed, the minimum uncompensated system voltage reached values as low as 0.803 p.u. under high penetration (12 chargers) and high power rating (1 MW), while moderate penetration (6 chargers) still produced minima around 0.88–0.90 p.u. These results confirm that robust siting alone is insufficient to guarantee voltage compliance when ultra-fast charging loads cluster in distribution feeders.

Second, the probabilistic Monte Carlo framework proved essential for capturing voltage-risk exposure under realistic uncertainty. By jointly modeling residential demand variability and stochastic EV charging activation, the method provided statistically meaningful indicators beyond deterministic worst-case snapshots. In particular, the analysis revealed persistent critical time windows during daytime peak hours, where under-voltage violations occur with high probability across Monte Carlo realizations, emphasizing the need for mitigation strategies that are robust to uncertainty.

Third, the proposed sensitivity-guided reactive compensation strategy demonstrated consistent effectiveness in mitigating under-voltage conditions. Across all scenarios, the application of local reactive support at the most critical bus increased the worst-hour minimum voltage by approximately 0.03–0.12 p.u., substantially reducing both the depth and duration of voltage violations. The maximum equivalent reactive support required reached 6.35 Mvar in the most stressed case, while scenarios with reduced charger ratings (350 kW) required significantly lower compensation levels.

Fourth, the comparative analysis highlighted two dominant planning insights. Increasing EV charging penetration from 6 to 12 points significantly exacerbates voltage degradation and shifts the weakest locations toward the feeder end, whereas reducing the unit charger rating from 1 MW to 350 kW markedly alleviates voltage stress and reactive-support requirements. These findings indicate that limiting individual charger power or adopting mixed charging hierarchies can be an effective lever for preserving voltage margins in EV-rich distribution networks.

Finally, the scope of the proposed Monte Carlo–V–Q sensitivity framework should be clearly interpreted. The approach is well suited for planning-stage studies of radial distribution systems operating under steady-state conditions, where the objective is to screen EV deployment scenarios, identify vulnerable buses, and estimate reactive-support needs under uncertainty. It is not intended to replace dynamic voltage-stability analysis, detailed inverter-level control design, or contingency-based operational studies. Within these boundaries, the framework offers a lightweight, transparent, and reproducible tool to support distribution-network planning in the context of accelerating ultra-fast EV charging adoption.