Abstract

Against the backdrop of global energy transition and increasingly severe environmental conditions, developing clean and efficient energy systems has become crucial. This study aims to investigate a solar tower receiver tri-generation (STRT) system combining supercritical CO2 (S-CO2) Brayton cycle and organic Rankine cycle (ORC), with the objective of achieving the production of electricity, hydrogen, and oxygen. The modeling of the STRT system is completed by using Ebsilon, and the performance of the STRT system is analyzed. The results show that the output power and efficiency of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle are 62.29 MW and 48.3%, respectively. The net power and efficiency of ORC are 8.02 MW and 16.35%. The hydrogen and oxygen production rates of the STRT system are 183.8 kg·h−1 and 1470.4 kg·h−1, respectively. The STRT system shows stable and effective operation performance throughout the year. Through the exergy analysis, the exergy losses and exergy efficiencies of different components of the STRT system are obtained. The solar tower has the largest exergy loss (218.85 MW) and the lowest exergy efficiency (63%). The levelized electricity cost and the levelized hydrogen cost of the STRT system are 0.0788 USD·kWh−1 and 2.97 USD·kg−1 with a recovery period of 8.05 years, which reveal the economic competitiveness of the STRT system.

1. Introduction

With the development of the world economy and industry technology, energy plays an increasingly indispensable role [1]. Nowadays, in the face of increasingly severe environmental problems, traditional energy is facing great challenges [2]. At present, the main sources of energy consumed by the world are still fossil fuels, which can cause serious pollution to the environment. Therefore, environmentally friendly and efficient renewable energy sources are urgently needed to address these issues [3].

Solar energy, as a clean energy source, features abundant reserves, wide distribution, and environmental friendliness, and has remarkable advantages among many renewable energy sources [4]. Solar power generation mainly includes two types, which are concentrated solar thermal power (CSP) [5] and photovoltaic power generation [6,7]. Solar thermal power generation can not only be combined with other heat sources, but can also be integrated with thermal storage systems [8]. The supercritical CO2 (S-CO2) Brayton cycle, as a power generation module, is widely adopted in many future solar power systems due to its advantages such as high energy conversion efficiency, compact structure, and small footprint [9]. The solar S-CO2 Brayton system combines solar thermal power generation with the S-CO2 Brayton cycle, improving the comprehensive energy utilization efficiency [10].

Many studies on S-CO2 Brayton cycles driven by CSP have been conducted. Lykas et al. [11] comprehensively studied a polygeneration system driven by both solar energy and biomass. The results showed that the energy efficiency at the optimal operation point was 37.89%, and the exergy efficiency was 20.86%. The yearly energy efficiency and exergy efficiency were 32.52% and 18.51%, respectively. Chen and Romero et al. [12] compared several solar S-CO2 Brayton systems and optimized the system by using genetic algorithms. The results indicated that simple re-generation cycle and re-compression cycles were the most effective S-CO2 Brayton systems when they were integrated with high-temperature CSP systems. Zaharil et al. [13] conducted a thermodynamic analysis on a solar-driven S-CO2 Brayton cycle and desalination system. The results demonstrated that the decrease in the direct normal irradiance (DNI) would lead to a reduction in the exergy efficiency of the system, and the system had an optimal efficiency when the pressure ratio was 3.1. Liu et al. [14] conducted a comprehensive analysis of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle and two dual pressure organic Rankine cycles (ORCs) from various perspectives. The results revealed that the total energy efficiency was 16.7%, the total exergy efficiency was 17.9%, and the recovery period was 4.38 years. Liu et al. [15] performed an advanced exergy analysis of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle. The results indicated that half of the exergy loss of each component was caused by the interaction between the components. Xingyan et al. [16] compared and optimized four different configurations of the S-CO2 Brayton cycles. The results indicated that the intercooling cycle exhibited the highest thermal efficiency under medium- and low-loads, while the re-heating cycle showed the highest thermal efficiency under high loads. Tafur-Escanta et al. [17] conducted an effect analysis of three various CO2-based mixed working fluids on operation performance of CSP driven S-CO2 Brayton cycle power plant. Results revealed that when the mixed fluid composed by CO2 and hexane was used, the Brayton cycle with two re-heaters had the optimal operation performance, leading to a cycle efficiency of 51.3%. Nieto et al. [18] carried out economic and dynamic analyses on a tower solar collector (TSC) driven S-CO2 Brayton cycle power system with thermo-chemical energy storage. They found that when the solar multiple was 2.6, and the discharging duration was 24 h, the power plant had the optimal performance, with an electric efficiency of 39%. Alves and Maia [19] conducted optimization works on TSC-driven S-CO2 Brayton cycle power plants in five various areas of Brazil. Results indicated that when the gas turbine inlet temperature and thermal input were 565.0 °C and 206.8 MW, respectively, the power plant had the highest cycle efficiency, which was 48.4%.

This paper proposes a solar tower receiver tri-generation (STRT) system that combines the S-CO2 Brayton cycle with ORC. The STRT system integrates multiple energy conversion systems to achieve the collaborative production of electric power, hydrogen, and oxygen. Electric power is generated by the S-CO2 Brayton cycle, while hydrogen and oxygen are produced by using a proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer (PEMWE) equipment. The operation process of STRT system is simulated by using Ebsilon software (Version: Professional 13 P2), and calculations are carried out for the entire year under non-design conditions. The system performance is evaluated in terms of exergy and economy. The main purpose of this study is to provide references for the research methods and development of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle multigeneration systems driven by solar tower. For the following contents of this paper, Section 2 presents the configuration, basic working principle, and design methods of the STRT system, simulation model, and formulas for exergy and economic analyses are introduced in Section 3, operation, exergy and economic performance evaluation results of the STRT system are presented in Section 4, and Section 5 serves as the conclusions section.

2. STRT System Design

2.1. Overall Design

The STRT system primarily consists of the TSC system, S-CO2 Brayton cycle, and ORC driven hydrogen production (ORCHP) system. The TSC system is primarily composed of heliostats field, solar tower receiver, and two thermal energy storage tanks (TESTs), with the working fluid consisting of 67% KCl and 33% MgCl2. The TSC system transfers heat to the S-CO2 Brayton cycle through two main heat exchangers (MHXs). This cycle adopts re-compression and re-heat combined configuration, which maximizes the utilization of the heat supplied by the MHXs to achieve high-efficiency energy conversion and ultimately converts thermal energy into electric power output. The ORC uses hexane as the working fluid and recovers waste heat from the TSC system through an evaporator (EVA). Hexane is vaporized into steam by heating, and then drives turbine (TUB) and power generator (G2) for power generation. All the power generated by ORC is supplied to the PEMWE, where water is split into hydrogen and oxygen through an electrochemical reaction.

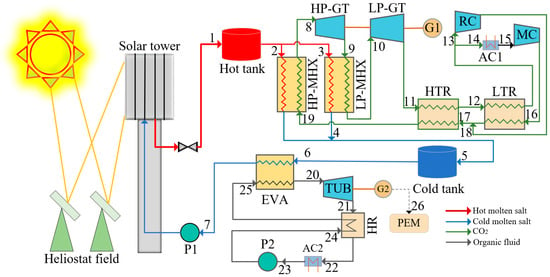

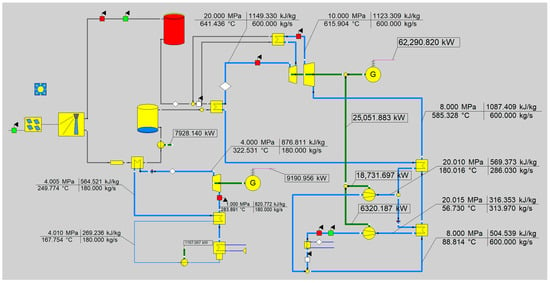

Figure 1 shows the working flow diagram of STRT system, where the heliostat field collects and reflects sunlight onto the receiver at the top of solar tower. The molten salt heats the S-CO2 through high-pressure and low-pressure main heat exchangers (HP- and LP-MHXs). The molten salt, after being heated in the receiver (State 1), flows into the two MHXs (States 2 and 3), and the excess molten salt will flow into the hot heat storage (HHS) tank. Then the molten salt flows into the cold heat storage (CHS) tank after being utilized by MHXs (States 4 and 5). As the molten salt out from the LP-MHX still has a certain amount of heat, to fully utilize the heat, the molten salt is transported to the EVA (State 6) and exchanges heat with hexane before returning to the solar tower receiver (State 7). To achieve cascaded energy utilization, the high-temperature S-CO2 does work through high-pressure and low-pressure gas turbines (HP- and LP-GTs) in turn (States 8 and 10), and then sequentially flows through various components of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle (States 9, 11–18) before finally returning to the HP-MHX (State 19). The hexane heated by the EVA will drive the TUB (State 20), which drives G2 to produce electric power. Then, the electric power is transported to the PEMWE (State 26).

Figure 1.

Abridged general view of STRT system.

2.2. TSC System

The TSC system consists of heliostat field, solar tower, molten salt pipeline, and TESTs. The heliostat field tracks the sun, reflects sunlight onto the receiver at the top of solar tower, and heats the molten salt inside the receiver. The TESTs store heat during periods of sufficient sunlight and releases heat when sunlight is insufficient, ensuring uninterrupted operation of the STRT system and a stable power supply throughout the day. Based on different energy utilization methods, the heliostat field area is divided into three parts, including the parts for S-CO2 Brayton cycle, ORCHP system, and TESTs. The calculation formulas are shown below [20]:

where QBC and QORC are the heat transferred from the TSC system to the S-CO2 Brayton cycle and ORC, respectively. QTSC is the heat storage capacity of HHS tank under rated operation conditions. DNIm and DNI1 are the rated and daily average solar radiation intensities, respectively. ηfield is the optical reflectivity of heliostat field. ηreceiver is the heat absorption efficiency of tower solar receiver. ηhex1 is the total heat transfer efficiency of HP- and LP-MHXs. ηhex2 is the heat transfer efficiency of EVA. ηhs and ths are the charging efficiency and charging time of the HHS tank, respectively. ATotal is the total area of the heliostat field required by STRT system. Ms is the solar multiple. The calculation results show that ABC, AORC, ATSC and ATotal are 235,164.6 m2, 101,853.9 m2, 527,420.4 m2, and 864,439.0 m2, respectively.

The acquisition of solar energy relies on sunlight, which is affected by factors such as day/night alternation and weather conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to add TESTs to CSP plants. Currently, there are two commonly used TEST system types, which are single and double TESTs. This study adopts the double TEST system for the STRT system. The TESTs employ the mixture composed of 67% KCl and 33% MgCl2 as the working fluid [21]. The physical properties of the mixture are [22]

where T is the working fluid temperature. ρMS, μMS, and kMS represent the density, dynamic viscosity, and thermal conductivity of working fluid. The constant–pressure specific heat capacity cp,MS is taken as 1.150 kJ·(kg·K)−1 at all temperatures [23].

Under the design condition, the TEST system of STRT system adopts a charging duration of 10 h and a discharging duration of 14 h. Formulas for the TEST system include

where E and ηE are the output power and efficiency of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle at the design point. EORC and ηORC are the net electric power and cycle efficiency of ORC at the design point. mMS refers to the quality of working fluid in the HHS tank while ensuring stable system operation. ΔT is the temperature difference between the HHS and CHS tanks. VTSC is the HHS tank volume. ηp is the pipeline efficiency of TSC system. thr is the discharging duration of HHS tank. The parameters of TESTs of the STRT system are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of TESTs.

2.3. Brayton Cycle

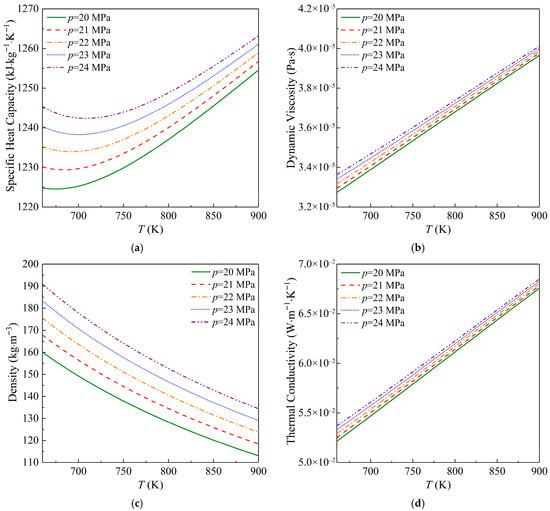

The STRT system adopts an S-CO2 Brayton cycle as the power cycle, which combines re-heating and re-compression. The re-heating process applies a staged expansion principle, dividing the expansion into two stages. Between the two expansion stages, the working fluid is re-heated by the LP-MHX using molten salt, achieving cascaded heating that improves energy utilization efficiency. The re-compression process utilizes two-stage re-generation with HTR and LTR. After coming out from the LTR, the working fluid is split into two streams, one stream of which flows directly into the HTR after passing through the RC, while the other stream enters the LTR after going through AC1 and MC. This configuration reduces the temperature difference between the hot and cold sides of the re-generators, enabling more efficient heat transfer and improving the total thermal efficiency of the cycle. Table 2 shows the relevant parameters of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle of STRT system, and Table 3 provides some brief performance introductions of some components in the Brayton cycle. Figure 2 presents the thermophysical parameters of S-CO2 under the operation pressure range of 20.0~24.0 MPa [24].

Table 2.

Parameters of Brayton cycle.

Table 3.

Brief performance introductions of some components in Brayton cycle.

Figure 2.

Thermophysical parameters of S-CO2 under the operation pressure range of 20.0~24.0 MPa: (a) specific heat capacity, (b) dynamic viscosity, (c) density, and (d) thermal conductivity.

2.4. ORCHP System

In the STRT system, the ORCHP system generates hydrogen and oxygen through the PEMWE, and the electricity required for the operation of PEMWE is provided by ORC. In the ORC, hexane is utilized as the working fluid [25,26]. After being heated in the EVA, the working fluid expands through the TUB to drive G2 for power generation. Following heat recovery in the HR, the organic fluid sequentially passes through AC2 and P2, thereby completing a full cycle. The working pressure and mass flow rate of ORC are 4.0 MPa and 180.0 kg·s−1, respectively.

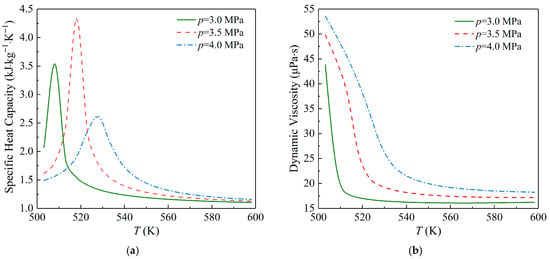

Hexane is selected as the working fluid for ORC due to some of its advantages compared with other organic fluids [27]. For instance, hexane has relatively good thermodynamic properties, which can improve the overall performance of the system. Meanwhile, it belongs to dry working fluid and is not able to easily enter the wet steam zone during the expansion process, which can protect the steam turbine and effectively ensure the stable operation of the equipment. In addition, the ozone depletion potential of hexane is zero, and its global warming potential is also at a relatively low level, with a small impact on the environment. Figure 3 presents the thermophysical parameters of hexane under the operation pressure range of 3.0~4.0 MPa.

Figure 3.

Thermophysical parameters of hexane under the operation pressure range of 3.0~4.0 MPa: (a) specific heat capacity, (b) dynamic viscosity, (c) density, and (d) thermal conductivity.

To address flammability and materials concerns brought by the usage of hexane, some safety measures should be adopted. For instance, inert gas should be used for protection, sealing design, and explosion-proof equipment, and a leak detection system should be adopted. Meanwhile, it is necessary to control the pinch temperature difference in the system to ensure the stability of the cycle.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Simulation Model

This study adopts Ebsilon to construct the simulation model [28]. Ebsilon is a software that can calculate and simulate various types of power generation systems based on thermodynamic principles and thermal equilibrium principles. The software can enable efficient calculations of different kinds of systems, analyze energy flow, conversion and destruction within the system, perform calculations for both design and off-design conditions, and demonstrate the operation characteristics of a system under various scenarios.

Based on the above system principles, Ebsilon (Version: Professional 13 P2) is used to simulate and model the STRT system. Figure 4 presents the STRT system model developed in Ebsilon. For simulations of the STRT system, Span–Wagner state formulas are used to calculate the enthalpy, entropy, and other parameters of CO2, and properties of hexane are calculated by using thermodynamic models adapted to hydrocarbon working fluids in the REFPROP property database within Ebsilon. Through system simulation and calculation, the operation, exergy, and economic performances of the STRT system are investigated.

Figure 4.

Simulation model of the STRT system.

To verify the quality and reliability of the Ebsilon-based model, a TSC system mentioned in Reference [29], a double-stage compressed S-CO2 Brayton cycle mentioned in Reference [30], and an ORC mentioned in Reference [31] are used for verification. Models of the TSC system, S-CO2 Brayton cycle, and ORC are constructed using Ebsilon, and the models are simulated with the same parameters. The simulation results are presented in Table 4. According to the results, the simulation outcomes of the Ebsilon-based models are basically consistent with the reference values in the literature, with only some components showing small discrepancies. This implies that the accuracy and reliability of Ebsilon are verified.

Table 4.

Verification results of Ebsilon.

3.2. Formulas for Exergy Evaluation

For the STRT system, to highlight the location where irreversibility of energy conversion occurs, the exergy loss and exergy efficiency of each component in the system are evaluated based on the second law of thermodynamics [32,33].

The formulas for calculating the exergy loss and exergy efficiency of the TSC system are

where Ex,r is the available energy absorbed by the TSC. mTSC is the mass flow rate of molten salt in the TSC system. hb and ha are the enthalpy values at the outlet and inlet of the TSC. The ambient temperature T0 is set to 25.0 °C. sb and sa are the entropy values at the outlet and inlet of solar receiver.

The exergy loss formula of an HX is

where Ex,hot,in and Ex,hot,out are the inlet and outlet exergies of hot fluid in the HX, and Ex,cold,in and Ex,cold,out are those of cold fluid in the HX.

The exergy loss formulas of the compressor and ST are

where Wcom is the power consumption of compressor. Ex,com,in and Ex,com,out are the inlet and outlet exergies of compressor. Ex,st,in and Ex,st,out are the inlet and outlet exergies of ST. Wst is the output power of ST.

The formulas for the exergy loss and exergy efficiency of other components in the S-CO2 Brayton cycle and ORC can be calculated as

3.3. Formulas for Economic Evaluation

The economic evaluation of the STRT system is mainly based on the levelized costs, net proceeds, and recovery period [34]. Levelized electricity cost (LEC) is

where R is the discount rate. CBC and CBC,th are the component costs and thermal costs of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle, respectively. OMCF and OMCV are fixed and variable operating and maintenance costs for the S-CO2 Brayton cycle and TSC system. Eyearly is the power generation of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle every year.

The levelized hydrogen cost (LHC) is

where CORC and CORC,th are the component costs and thermal costs of ORCHP system. CORC,op is the operation costs of ORC. tser is the service life of STRT system. Mh,yearly is the hydrogen production of STRT system every year.

For cost calculations of typical items of STRT system, formulas are presented in Table 5 [35,36]. In Table 5, Hhx, Hreg, and Hcooler are conductance values of the heat exchanger, re-generator, and pre-cooler. Wtur is the output power of GT. Wcom and Ppemwe are the power consumptions of the compressor and PEMWE, respectively. htow is the height of the solar tower. Cemployee is the average salary. Nemployee is the number of employees. α is the welfare coefficient. Cfuel is the fuel costs, which is 0.0 for the STRT system. C1, C2, and C3 are the cost coefficients of the heliostats, molten salt, and TEST system, respectively.

Table 5.

Some detailed cost calculation formulas [34,35].

Table 5.

Some detailed cost calculation formulas [34,35].

| Item | Formula | |

|---|---|---|

| Heat exchanger | (23) | |

| GT | (24) | |

| Re-generator | (25) | |

| Compressor | (26) | |

| Pre-cooler | (27) | |

| Heliostats | (28) | |

| Solar tower | (29) | |

| TEST | (30) | |

| Heat transfer fluid | (31) | |

| PEMWE | (32) | |

| Fixed operating and maintenance costs | (33) | |

| Fixed maintenance costs | (34) | |

| Employee costs | (35) | |

The net proceeds of the STRT system are

where PE, Ph, and Po are the selling prices of electricity, hydrogen, and oxygen, respectively. Mo,yearly is the oxygen production of the STRT system every year.

The cost recovery period of STRT system is

where CTotal represents the total investment cost of the STRT system.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Operation Simulation Results

4.1.1. Design Conditions

Based on the STRT system model constructed in Ebsilon, under design conditions, DNIm is 900.0 W·m−2. the external temperature is 25.0 °C, and the atmospheric pressure is 0.101 MPa. The operation process of the STRT system is simulated and calculated under design operation conditions. Table 6 shows the simulation results of the STRT system.

Table 6.

Simulation results of STRT system under design conditions.

Results show that under design conditions, the electric power of the S-CO2 Brayton cycle is 62.29 MW, with a cycle efficiency of 48.3%. The ORC, serving as the bottoming cycle for the entire system, recovers the waste heat from the S-CO2 Brayton cycle. Its net power is 8.02 MW, and its cycle efficiency is 16.35%. All the electricity generated by ORC is transported to PEMWE to produce hydrogen and oxygen, with a hydrogen production rate of 183.8 kg·h−1 and an oxygen production rate of 1470.4 kg·h−1.

The results of this paper are compared with those of other multigeneration systems, and the comparison results are shown in Table 7. In Table 7, normalized parameters are obtained through dividing production rates or output power by the total solar concentrator field area of each multigeneration system. Due to the differences in the structures, principles, and unit capacities of these multigeneration systems, their product categories and normalized production capacities are also different.

Table 7.

Comparison of this work and some other typical solar multigeneration systems.

4.1.2. Off-Design Conditions

To analyze the operation characteristics of the STRT system under actual weather conditions, the system is simulated throughout the year based on the changes in daily DNI. There can be many different operation strategies for a certain solar multigeneration system, and the operation strategy for the STRT system in this study is as follows:

- (1)

- During the period of 7:00 to 17:00, when the DNI is sufficient, the Brayton cycle and ORCHP system operate at 100% rated level. In the case of insufficient DNI, the two systems operate at 50% rated level if the working fluid level state in the HHS tank can be in 2.0%~98.0%.

- (2)

- During the period of 17:00 to 7:00, when the working fluid level state in the HHS tank can be in 2.0%~98.0%, the Brayton cycle and ORCHP system operated at 50% rated level.

- (3)

- When the working fluid level state in the HHS tank is in 2.0%~98.0%, if there is excess solar radiation, the HHS tank should be charged, and if the solar heat is insufficient, the HHS tank should be discharged. When the working fluid level state in the HHS tank is greater than or equal to 98.0%, the HHS tank should not be charged even if there is excess solar radiation, so that the pressure in the HHS tank does not exceed the limit. When the working fluid level state in the HHS tank is smaller than or equal to 2.0%, the HHS tank should not be discharged.

- (4)

- When both the DNI and the working fluid in the HHS tank are insufficient simultaneously, the STRT system stops running. Here, insufficient working fluid in the HHS tank refers to that the working fluid level state in the HHS tank is smaller than or equal to 2.0%.

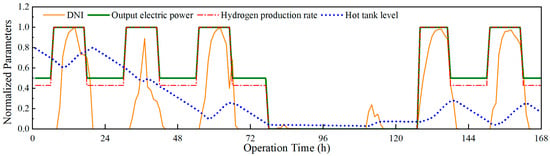

Based on the operation strategy and actual sunlight data, a year-round simulation of the STRT system is conducted. The DNI and temperature data are selected from a typical year in Lanzhou City (36°03′ N, 103°49′ E) of China. Figure 5 shows the normalized simulation results of the STRT system for seven consecutive days in February. Results show that during days with sufficient DNI, the electric power and hydrogen production rate of the STRT system remain at 62.29 MW and 183.8 kg·h−1. During days and nights when DNI is low and the working fluid in the HHS tank is sufficient, the output powers of the Brayton cycle and ORC are 50% of the rated level. When the solar radiation and working fluid are both insufficient, the STRT system is shut down. The working fluid level in the HHS tank is jointly affected by DNI and heat consumed by the STRT system. Therefore, it is concluded that the TSC system, S-CO2 Brayton cycle, and ORCHP system are able to achieve long-term stable operation under the formulated operation strategy.

Figure 5.

Simulation results of operation process of STRT system for seven consecutive days.

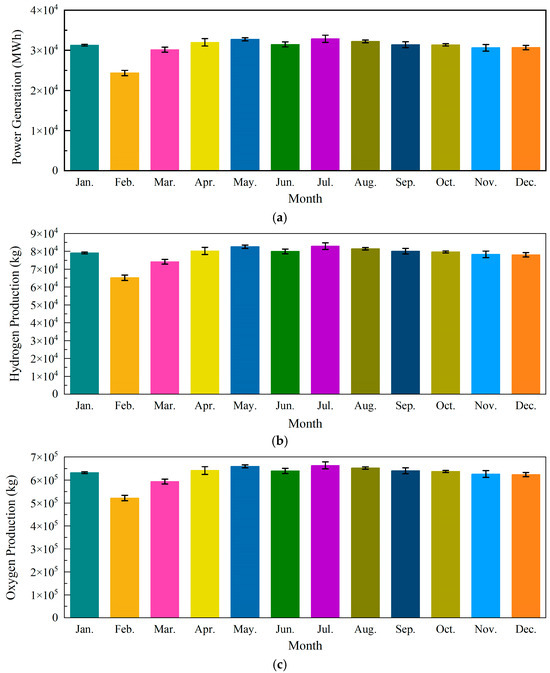

Table 8 and Figure 6 show the operation results of STRT system for electric power, hydrogen, and oxygen productions in a year. We,BC represents the electric power generation of the Brayton cycle. We,ORC represents the net power generation of ORC. And Mh,ORC and Mo,ORC represent the hydrogen and oxygen productions of the ORCHP system. Results show that the whole system produces the highest amounts of electricity, hydrogen and oxygen in July, which are 32,835.43 MWh, 82,503.17 kg and 660,025.35 kg, respectively. For the whole year, the power output of STRT system is 371,069.12 MWh, and the hydrogen and oxygen productions are 939,295.7 kg and 7,514,365.57 kg. These data basically match the evaluation results of STRT system under design operating conditions.

Table 8.

Annual operation performance of STRT system.

Figure 6.

Annual operation performance of STRT system: (a) We,BC, (b) Mh,ORC, and (c) Mo,ORC.

4.2. Exergy Evaluation Results

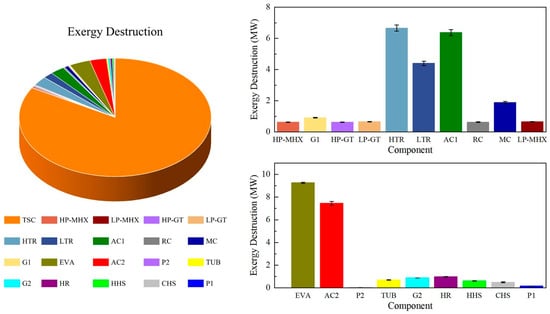

In the exergy evaluation of STRT system, based on the second law of thermodynamics, the exergy losses and exergy efficiencies of various components in the STRT system are analyzed using the equations of Section 3.2 as well as Ebsilon. Results are shown in Figure 7 and Table 9.

Figure 7.

Exergy loss distribution of STRT system.

Table 9.

Exergy performance of STRT system.

Table 9 shows the exergy losses and exergy efficiencies of typical components of STRT system. HHS, CHS, and P1 represent the HHS tank, CHS tank, and pump in the TSC system, respectively. Results show that the TSC has the largest exergy loss (218.85 MW). At the same time, it has an exergy efficiency of only 63%, which is also the lowest. The large exergy loss in the TSC is mainly brought by two aspects, which are the optical loss of TSC, and thermal conduction, radiation, and convection heat losses of the solar tower. To decrease the exergy loss of the TSC, the design and structural materials of the TSC should be improved. For instance, heliostat material with higher reflectance should be utilized, and TSC tube materials with larger absorptance should be developed. EVA has the second highest level of exergy loss (9.25 MW), while AC1 and AC2 have similar levels of exergy losses (i.e., 6.37 MW and 7.42 MW). Hence, there is certain potential for improvement in energy utilization for these components.

4.3. Economic Evaluation Results

The economic evaluation of STRT system is based on the theoretical framework of levelized cost of energy. Under this framework, a dynamic discount analysis is conducted on STRT system with considering fixed investment cost, operation and maintenance cost, thermal cost, and equipment depreciation cost. The economic evaluation of the STRT system mainly calculates the levelized costs, net proceeds, and recovery period. Table 10 shows some initial parameters for the economic evaluation. For the whole system, the discount rate is 0.1, the external power required for the ORCHP system is 0.0. The service life of STRT system is 25 years. Table 11 shows the economic evaluation results.

Table 10.

Parameters for economic analysis of STRT system.

Table 11.

Results for economic evaluation of STRT system.

Results reveal that LEC of STRT system is 0.0788 USD·kWh−1, and LHC is 2.97 USD·kg−1. A review of the literature [41] shows that the cost of hydrogen production from electrolytic water in the United States ranges from 2.0 USD·kg−1 to 12.0 USD·kg−1. Those indicate that LHC of STRT system is relatively reasonable and economically competitive. The net proceeds and recovery period of STRT system are calculated when the selling prices of electricity, hydrogen, and oxygen are chosen to be 0.164 USD·kWh−1, 6.00 USD·kg−1, and 0.064 USD·kg−1, respectively. According to the economic evaluation, the net proceeds of selling electricity is about 8.11 × 108 USD, and that of selling hydrogen and oxygen is about 8.93 × 107 USD. The recovery period of the entire STRT system is 8.05 years.

5. Conclusions

To contribute to the goal of achieving carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, this study proposes a novel STRT system utilizing the S-CO2 Brayton cycle and ORC, which is designed to produce electric power, hydrogen, and oxygen. The STRT system consists of the TSC system, S-CO2 Brayton cycle, and ORC powered hydrogen production system. By using Ebsilon, evaluations of operation, exergic, and economic performances are conducted for the STRT system. Main results are concluded as follows:

- (a)

- The operation simulation results reveal that the S-CO2 Brayton cycle has an electric power of 62.29 MW and a cycle efficiency of 48.29%. Hydrogen and oxygen production rates of the STRT system are 183.8 kg·h−1 and 1470.4 kg·h−1, respectively. The STRT system can achieve long-term and stable operation.

- (b)

- The exergy analysis results show that the TSC had the highest exergy loss of 218.85 MW and the lowest exergy efficiency of 63%. The overall exergy efficiency of the STRT system is 25%.

- (c)

- The economic analysis shows that the levelized electricity and hydrogen costs of the STRT system are 0.0788 USD·kWh−1 and 2.97 USD·kg−1, respectively. The net proceeds of selling electricity and selling hydrogen and oxygen are 8.11 × 108 USD and 8.93 × 107 USD, respectively, and the recovery period is 8.05 years.

For further research, dynamic simulations of the STRT system should be conducted to evaluate the dynamic characteristics of the system. In addition, advanced exergy analysis is also meaningful for the deep understanding and optimization works of the STRT system. Moreover, the optimization study on operation strategy of the STRT system is also a further research work in the future.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, G.W.; Writing—review and editing, T.B. and Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| A | area (m2) |

| C | cost (USD) |

| cp,MS | specific heat capacity (kJ·(kg·K)−1) |

| P | price (USD) |

| DNI | solar intensity (W·m−2) |

| E | electric power (MW) |

| Ex | exergy loss (MW) |

| k | thermal conductivity (W·(m·K)−1) |

| LEC | levelized electricity cost (USD·kWh−1) |

| LHC | levelized hydrogen cost (USD·kg−1) |

| m | mass (kg) |

| Ms | solar multiple |

| OMCf | fixed operating and maintenance cost (USD) |

| OMCv | variable operating and maintaining cost (USD·kWh−1) |

| Q | heat (kJ) |

| R | discounted rate (-) |

| t | time (h) |

| T | temperature |

| V | volume (m3) |

| ΔT | temperature difference (℃) |

| Greek symbols | |

| η | efficiency (-) |

| ρ | density (kg·m−3) |

| μ | dynamic viscosity (Pa·s) |

| Subscripts | |

| BC | Brayton cycle |

| field | heliostats field |

| h | hydrogen |

| hex | heat exchanger |

| hr | heat release |

| hs | heat storage |

| MS | molten salt |

| np | net proceeds |

| o | oxygen |

| op | operation |

| receiver | solar receiver |

| rev | revenue |

| ser | service life |

| th | thermal |

| tur | turbine |

| x | exergic |

| p | pipe |

| Abbreviations | |

| AC | air cooler |

| CFPP | coal-fired power plant |

| CSP | concentrated solar power |

| EVA | evaporator |

| G | generator |

| GT | gas turbine |

| HR | heat regenerator |

| HTR | high-temperature recuperator |

| HX | heat exchanger |

| LTR | low-temperature recuperator |

| MC | main-compressor |

| MHX | main heat exchanger |

| ORC | organic Rankine cycle |

| ORCHP | ORC driven hydrogen production |

| P | pump |

| PEMWE | proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer |

| RC | re-compressor |

| S-CO2 | supercritical CO2 |

| STRT | solar tower receiver tri-generation |

| TEST | thermal energy storage tank |

| TSC | tower solar collector |

| TUB | turbine |

References

- Yilmaz, F.; Ozturk, M.; Selbas, R. Thermodynamic investigation of a concentrating solar collector based combined plant for polygeneration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 26138–26155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Duan, L.; Yang, M.; Jiang, Y. Performance analysis and optimization study of a new supercritical CO2 solar tower power generation system integrated with steam Rankine cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 232, 121050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhai, R.; Liu, L.; Yin, H.; Yang, L. Capacity optimization and performance analysis of wind power-photovoltaic-concentrating solar power generation system integrating different S-CO2 Brayton cycle layouts. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 433, 139342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z.; Gong, X.; Dai, Y.; Markides, C. Thermo-economic assessment and systematic comparison of combined supercritical CO2 and organic Rankine cycle (SCO2-ORC) systems for solar power tower plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrafi, E.; Khaliq, A.; Kumar, R.; Bamasag, A.; Siddiqui, M. Proposal and Investigation of a New Tower Solar Collector-Based Trigeneration Energy System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ji, X.; Zou, T.; Chen, Z. Effect evaluation of frame perforation on reducing photovoltaic panel temperature with passive air cooling. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 76, 107296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Zou, T.; Han, W.; Chen, Z. Design and performance evaluation of a novel solar concentration PVT system with dual-runner nanofluids optical filtering. Energy 2025, 340, 139259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Y. A review on integrated design and off-design operation of solar power tower system with S-CO2 Brayton cycle. Energy 2022, 246, 123348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, D.; Zou, T.; Duan, Y. Design and performance evaluation of an innovative solar concentration polygeneration system. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghafar, M.; Hassan, M.; Kayed, H. Direct integration of supercritical carbon dioxide-based concentrated solar power systems and gas power cycles: Advances and outlook. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 269, 126064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykas, P.; Bellos, E.; Kitsopoulou, A.; Tzivanidis, C. Dynamic analysis of a solar-biomass-driven multigeneration system based on s-CO2 Brayton cycle. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 1268–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Romero, M.; González-Aguilar, J.; Rovense, F.; Rao, Z.; Liao, S. Design and off-design performance comparison of supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycles for particle-based high temperature concentrating solar power plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 232, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharil, H.; Yang, H. Thermodynamic analysis of a parabolic trough power plant integrating supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle and direct contact membrane distillation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 252, 123637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Talesh, S. Assessment of a sustainable power generation system utilizing supercritical carbon dioxide working fluid: Thermodynamic, economic, and environmental analysis. Energy 2024, 290, 130321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cao, X.; Luo, T.; Yang, X. Advanced exergoeconomic evaluation on supercritical carbon dioxide recompression Brayton cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyan, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Cai, J.; Tian, H.; Shu, G. Optimal selection of supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle layouts based on part-load performance. Energy 2022, 256, 124691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafur-Escanta, P.; Valencia-Chapi, R.; Muñoz-Antón, J. Entropy analysis of new proposed Brayton cycle configurations for solar thermal power plants. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 62, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, F.; Calle, A.; Arias, I.; Cardemil, J.; Bayon, A.; Escobar, R. Annual performance of a calcium looping thermochemical energy storage with sCO2 Brayton cycle in a solar power tower. Energy 2025, 336, 138344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I.; Maia, C. Thermodynamic assessment of a molten salt solar power tower integrated with a supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle under Brazilian solar conditions. Sol. Energy 2025, 301, 113962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hao, J.; Wang, B.; Han, W. Comparative study on thermal and mechanical performances of liquid lead thermocline heat storage tank with different solid filling material layouts. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Bauer, T. Progress in Research and Development of Molten Chloride Salt Technology for Next Generation Concentrated Solar Power Plants. Engineering 2021, 7, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavoico, A.B. Solar Power Tower Design Basis Document; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mehos, M.; Turchi, C.; Vidal, J.; Wagner, M.; Ma, Z.; Ho, C.; Kolb, W.; Andraka, C.; Kruizenga, A. Concentrating Solar Power Gen3 Demonstration Roadmap; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Applewood, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Zou, T. Design and comparison study of a novel linear Fresnel reflector solar ORC-driven hydrogen production system using different working fluids. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 71, 106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.; Almatrafi, E.; Bamasag, A.; Saeed, U. Adoption of CO2-based binary mixture to operate transcritical Rankine cycle in warm regions. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.; Almatrafi, E.; Saeed, U.; Taimoor, A. Selection of Organic Fluid Based on Exergetic Performance of Subcritical Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) for Warm Regions. Energies 2023, 16, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, C.; Yagli, H.; Ata, S.; Koc, A.; Kocaman, E. Scrutinizing effect of temperature and pressure variation of a double-pressure dual-cycle geothermal power plant turbines on the temperature profile and heat gain of the heat exchangers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Cheng, Z. Coupled optical and thermal performance of a fin-like molten salt receiver for the next-generation solar power tower. Appl. Energy 2020, 272, 115079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiao, J. Characteristic Analysis of an S-CO2 Recompression Brayton Cycle. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2018, 38, 763–767. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, C.; Kanoglu, M.; Abusoglu, A. Exergetic cost evaluation of hydrogen production powered by combined flash-binary geothermal power plant. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 14021–14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Jia, C.; Liu, P.; Li, Z. Analysis of the effect of the ceramic membrane module based on Ebsilon software on water recovery of flue gas from coalfired power plants. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2020, 48, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayer, E.; Galanis, N.; Desilets, M.; Nesreddine, H.; Roy, P. Analysis of a carbon dioxide transcritical power cycle using a low temperature source. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, A.; Vesely, L.; Kapat, J. Exergoeconomic analysis of hybrid sCO2 Brayton power cycle. Energy 2022, 247, 123436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neises, T.; Turchi, C. Supercritical carbon dioxide power cycle design and configuration optimization to minimize levelized cost of energy of molten salt power towers operating at 650 °C. Sol. Energy 2019, 181, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, K.; McGowan, J.; Saghafifar, M. Thermoeconomic analysis of multi-stage recuperative Brayton power cycles: Part I-hybridization with a solar power tower system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 185, 898–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozgeyik, A.; Altay, L.; Hepbasli, A. A parametric study of a renewable energy based multigeneration system using PEM for hydrogen production with and without once-through MSF desalination. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 31742–31754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, G.; Ghaebi, H.; Ziapour, B.; Javani, N. Comprehensive thermoeconomic analysis of a novel solar based multigeneration system by incorporating of S-CO2 Brayton, HRSG and Cu-Cl cycles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.; Babaelahi, M. Innovative solar-based multi-generation system for sustainable power generation, desalination, hydrogen production, and refrigeration in a novel configuration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dong, B.; Chen, Z. Design and behaviour estimate of a novel concentrated solar-driven power and desalination system using S-CO2 Brayton cycle and MSF technology. Renew. Energy 2021, 176, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, D.; Qi, M.; Kim, J. Techno-economic analysis of anion exchange membrane electrolysis process for green hydrogen production under uncertainty. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.