Salt Deposit Detection on Offshore Photovoltaic Modules Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

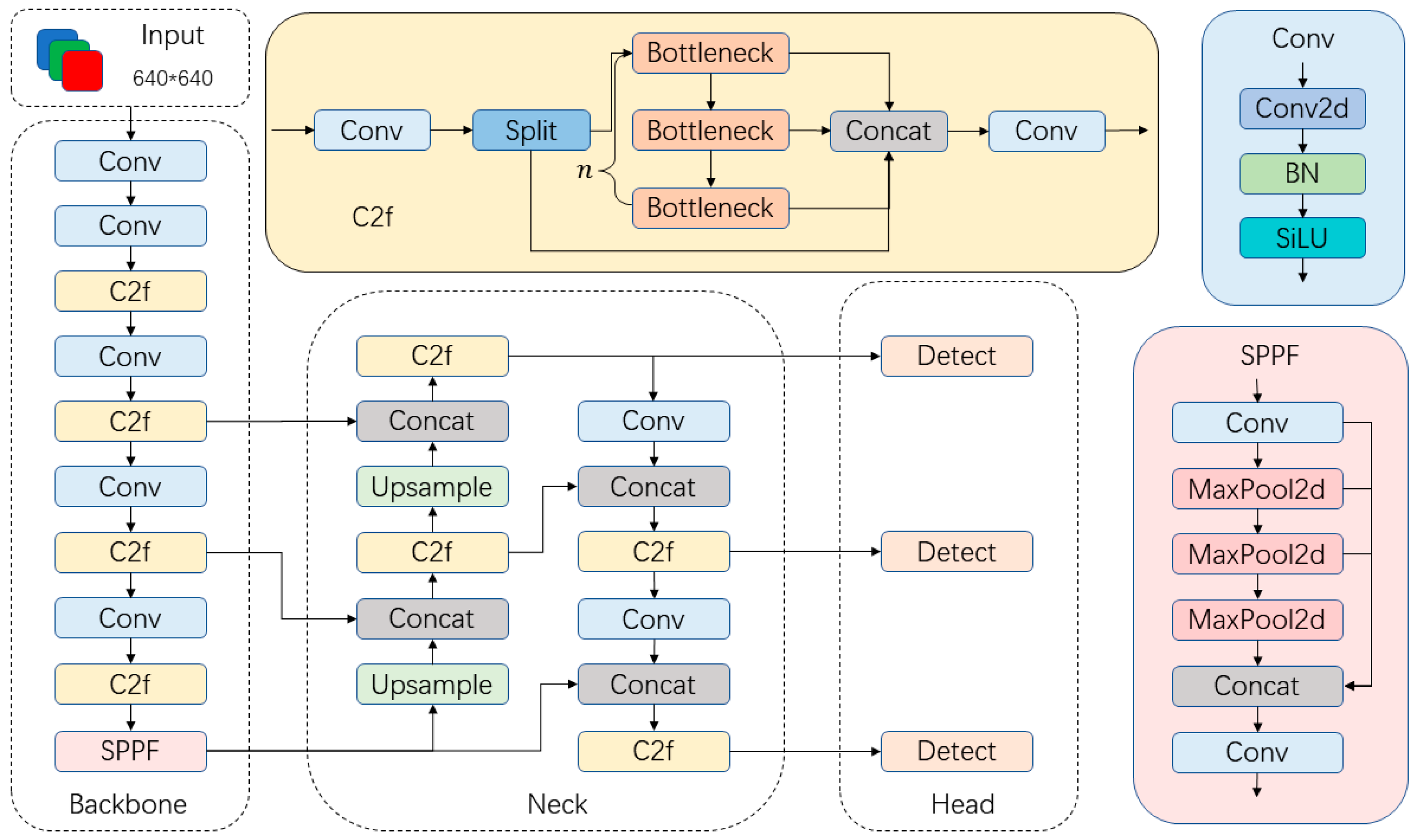

2.1. YOLOv8 Baseline Architecture

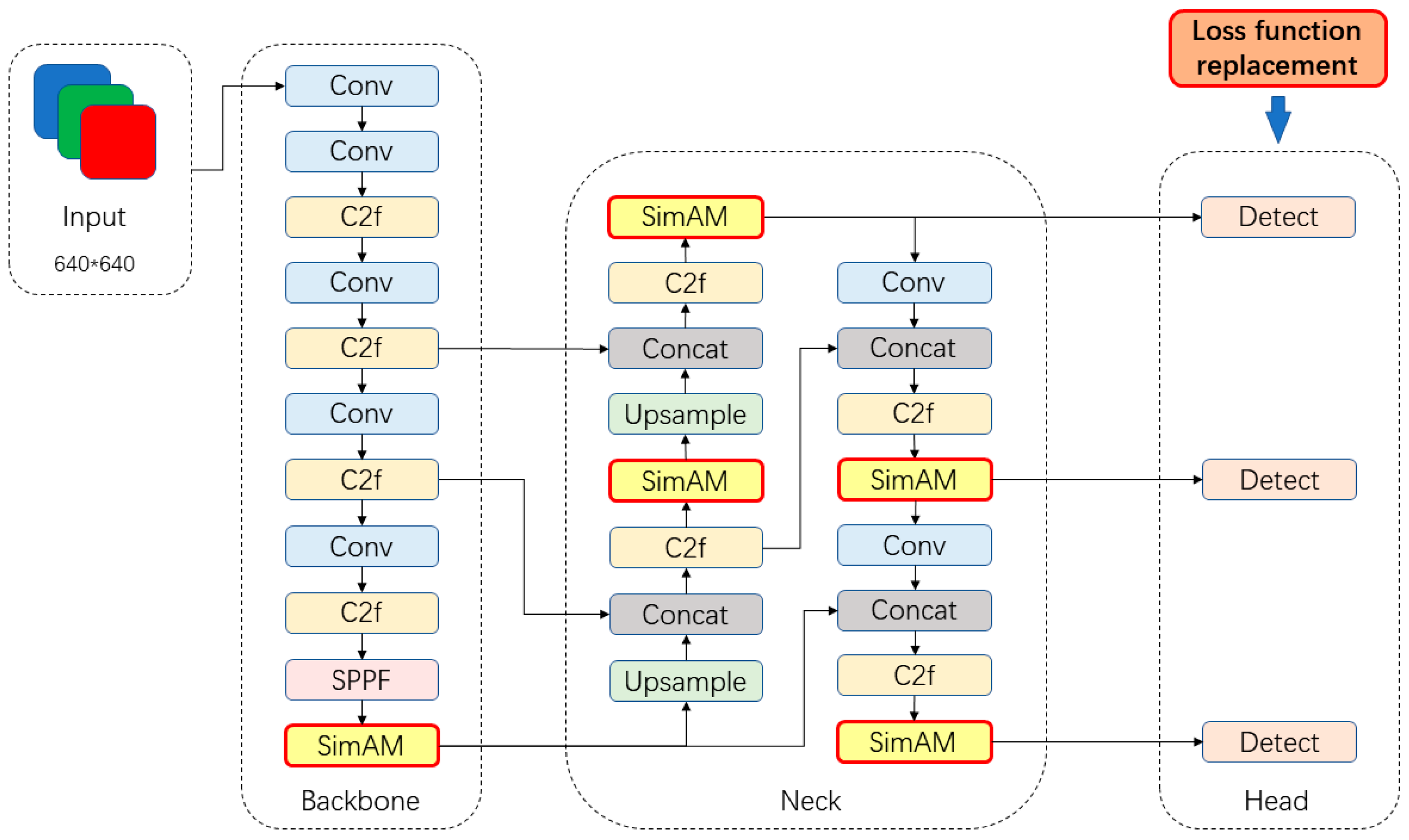

2.2. Proposed Improved YOLOv8 Method

2.2.1. Structural Improvements to the YOLOv8 Network

2.2.2. SimAM Attention Mechanism

2.2.3. Optimization of the Loss Function

3. Salt Deposit Detection Experiments

3.1. Experimental Dataset

3.2. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

3.3. Experimental Results

3.4. Ablation Experiment

3.5. Field Test Verification

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Embedding the SimAM parameter-free attention mechanism into both the backbone and neck enhances the ability of the network to extract discriminative features under complex offshore environmental conditions. Experimental results show that SimAM improves the mAP50 of the model while simultaneously reducing the number of parameters and GFLOPs, enabling better accuracy–efficiency balance.

- (2)

- Substituting the standard bounding-box regression loss with WIoU effectively suppresses the harmful gradients caused by low-quality samples. This improvement enhances the stability of the training process and increases the overall detection accuracy, demonstrating stronger robustness and generalization capability.

- (3)

- With the combination of both improvements, the proposed model achieves an mAP50 of 85.8%, representing a 3% gain over the YOLOv8 baseline. The improved algorithm also reduces model complexity and increases detection speed, and the final detection performance has been validated through real-measurement tests on the constructed offshore photovoltaic salt deposition dataset.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panjwani, B. Assessment of Breakwater as a Protection System against Aerodynamic Loads Acting on the Floating PV System. Energies 2024, 17, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; PL, D. Review of Recent Offshore Photovoltaics Development. Energies 2022, 15, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajc, T.; Kostadinović, D. Potential of usage of the floating photovoltaic systems on natural and artificial lakes in the Republic of Serbia. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafasfeh, M.; Abdel-Qader, I.; Bazuin, B.; Alsafasfeh, Q.; Su, W. Unsupervised Fault Detection and Analysis for Large Photovoltaic Systems Using Drones and Machine Vision. Energies 2018, 11, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Luo, X.; Yan, W. Visible defects detection based on UAV-based inspection in large-scale photovoltaic systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2017, 11, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-F.J.; Chen, S.-H.; Huang, C.-Y. Automatic detection, classification and localization of defects in large photovoltaic plants using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) based infrared (IR) and RGB imaging. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, L.S.; Sousa, T.D.; Pereira, C.D.; Pinto, A.M. Anomaly Detection for PV Modules using Multi-modal Data Fusion in Aerial Inspections. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 88762–88779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, J.A.; Chrysostomou, D.; Botsaris, P.N.; Gasteratos, A. Fault diagnosis of photovoltaic modules through image processing and Canny edge detection on field thermographic measurements. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2015, 34, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, G.C.; Macabebe, E.Q.B. Image segmentation using K-means color quantization and density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) for hotspot detection in photovoltaic modules. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Singapore, 22–25 November 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1614–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Khanam, R. In-depth review of yolov1 to yolov10 variants for enhanced photovoltaic defect detection. Solar 2024, 4, 351–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masita, K.; Hasan, A.; Shongwe, T.; Hilal, H.A. Deep learning in defects detection of PV modules: A review. Sol. Energy Adv. 2025, 5, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijjawi, U.; Lakshminarayana, S.; Xu, T.; Fierro, G.P.M.; Rahman, M. A review of automated solar photovoltaic defect detection systems: Approaches, challenges, and future orientations. Sol. Energy 2023, 266, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Pironti, C.; Saggese, A.; Vento, M.; Vigilante, V. A deep learning based approach for detecting panels in photovoltaic plants. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applications of Intelligent Systems, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 7–9 January 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hou, H.; Yu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, X. YOLO-LitePV: A lightweight detection algorithm for photovoltaic panel defects. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, D.; Lu, R.; Liu, X.; Wan, D. C2DEM-YOLO: Improved YOLOv8 for defect detection of photovoltaic cell modules in electroluminescence image. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 40, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, P. A novel lightweight detector for precise measurement of defects in photovoltaic panels in complex industrial scenarios. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liu, Z.; Aleksandrovich Martynov, S.; Zhao, X.; Tan, J.; Lu, S. Detection algorithm for solar photovoltaic cell surface defects based on multi-scale edge information selection. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tu, D. Unsupervised defect detection for solar photovoltaic cells based on convolutional autoencoder. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 40, 6143–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A review on Yolov8 and Its Advancements. In International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.S.; Simam, X. A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Hu, Q.; Zuo, W. Enhancing geometric factors in model learning and inference for object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 8574–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: Bounding Box Regression Loss with Dynamic Focusing Mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.10051. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

| Model | mAP50 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | 82.8 | 11.16 | 28.8 | 65.3 |

| +CA | 83.4 | 11.33 | 29.2 | 60.5 |

| +SE | 83.4 | 11.21 | 28.7 | 62 |

| +SimAM | 84.8 | 11.12 | 28.4 | 66.5 |

| Model | mAP50 (%) | FPS |

|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8+CIoU | 82.8 | 65.3 |

| YOLOv8+DIoU | 82.4 | 59.9 |

| YOLOv8+GIoU | 83.3 | 63.5 |

| YOLOv8+WIoU | 83.4 | 66.2 |

| Model | mAP50 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 | 82.5 | 14.40 | 15.8 | 75.0 |

| YOLOv8 | 82.8 | 11.16 | 28.8 | 65.3 |

| YOLOv10 | 81.1 | 8.04 | 16.6 | 78.0 |

| Proposed | 85.8 | 11.12 | 28.4 | 67.3 |

| Model | Loss | Attention | P (%) | R (%) | mAP50 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | 76.1 | 80.7 | 82.8 | 11.16 | 28.8 | 65.3 | ||

| A | √ | 79.4 | 79.2 | 83.4 | 11.16 | 28.8 | 66.2 | |

| B | √ | 77.6 | 80.8 | 84.8 | 11.12 | 28.4 | 66.5 | |

| C | √ | √ | 81.7 | 77.6 | 85.8 | 11.12 | 28.4 | 67.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Salt Deposit Detection on Offshore Photovoltaic Modules Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework. Energies 2026, 19, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020294

Li G, Wang S, Liu B, Xu M, Liu Z, Wang H. Salt Deposit Detection on Offshore Photovoltaic Modules Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework. Energies. 2026; 19(2):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020294

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Gang, Shuqing Wang, Bo Liu, Mingqiang Xu, Zhenhai Liu, and Haoge Wang. 2026. "Salt Deposit Detection on Offshore Photovoltaic Modules Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework" Energies 19, no. 2: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020294

APA StyleLi, G., Wang, S., Liu, B., Xu, M., Liu, Z., & Wang, H. (2026). Salt Deposit Detection on Offshore Photovoltaic Modules Using an Enhanced YOLOv8 Framework. Energies, 19(2), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020294