Abstract

Hydrogen energy is vital for a clean, low-carbon society, and proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) represent a core technology for the conversion of hydrogen chemical energy into electrical energy. When PEMFC single cells are stacked under assembly force for high power output, their porous electrodes (gas diffusion layers, GDLs; catalyst layers, CLs) undergo compressive deformation, altering internal transport processes and affecting cell performance. However, existing microscale studies on PEMFC porous electrodes insufficiently consider compression (especially in CLs) and have limitations in obtaining compressed microstructures. This study proposes a combined framework from a microstructure perspective. It integrates the finite element method (FEM) with computational fluid dynamics (CFD). It reconstructs microstructures of GDL, CL, and GDL-bipolar plate (BP) interface. FEM simulates elastic compressive deformation, and CFD calculates transport properties (solid zone: heat/charge conduction via Laplace equation; fluid zone: gas diffusion/liquid permeation via Fick’s/Darcy’s law). Validation shows simulated stress–strain curves and transport coefficients match experimental data. Under 2.5 MPa, GDL’s gas diffusivity drops 16.5%, permeability 58.8%, while conductivity rises 2.9-fold; CL compaction increases gas resistance but facilitates electron/proton conduction. This framework effectively investigates compression-induced transport property changes in PEMFC porous electrodes.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen energy is an indispensable energy for building a clean and low-carbon society in the future. Hydrogen has high abundance, high calorific value, and no pollution during the energy conversion process, making it an ideal alternative to traditional fossil fuels [1]. The hydrogen energy industry chain includes upstream hydrogen production, midstream hydrogen storage and transportation, and downstream hydrogen utilization [2]. Spanning from upstream hydrogen production to midstream storage and transportation, and further to downstream utilization, the hydrogen energy industry chain forms an integrated and interdependent system [2]. Within this industrial chain, PEMFCs act as pivotal energy conversion units, enabling the direct conversion of hydrogen’s chemical energy into usable electrical energy with high efficiency [3]. It has the advantages of low noise, high efficiency, and low-temperature startup, and has achieved rapid development in recent years. A single fuel cell consists of bipolar plates (BPs), gas diffusion layers (GDLs), catalyst layers (CLs) on both the anode and cathode sides, and a proton exchange membrane sandwiched in the middle [1]. To achieve high power output, several single cells are stacked in series under assembly force. At this point, the porous electrodes (including GDL and CL) in the fuel cell undergo compressive deformation, which changes the internal transport processes and further affects the cell output performance [4,5].

The porous electrode of PEMFC is the core region where mass, energy transport, and electrochemical reactions occur [6]. Heat conduction, charge conduction, water permeation, and gas diffusion coexist and are mutually coupled. The GDL is a porous material composed of carbon fibers, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), and binders. The functions of the GDL include transporting reaction gases from the flow field plate to the CL, discharging water generated by the reaction in the CL, and conducting electrons [7]. The CL is generally composed of catalyst (comprising anchored catalyst nanoparticles and their carbon support), ionomer, and pores. Electrochemical reactions occur at the three-phase boundary (TPB) formed by the ionomer, pores, and catalyst [8]. Besides, a microporous layer (MPL) sometimes exists between the GDL and the CL; however, its thickness is usually thin and it is not the main source of transport resistance. Therefore, many scholars have focused on the transport properties of the CL and GDL.

Transport phenomena within the CL directly determine the reaction rate, thus attracting extensive attention from researchers. Yamamoto et al. [9] developed a mass transport-aware model to simulate reactions and mass transport in the catalyst layer (CL). Their results show that the interior-to-total Pt ratio is impactful, while carbon support pore size distribution is critical under low relative humidity. Lee et al. [10] investigated the influence of the film thickness on the transport properties using molecular dynamics simulations. It was found that thicker films favor water and proton vehicular transport but impede proton hopping and oxygen permeability (oxygen solubility dominates permeability). Prokop et al. [11] employed FIB-SEM for 3D microstructure reconstruction of PBI-bonded CLs in HT-PEM fuel cells. The mathematical models were developed based on the reconstructed microstructure to calculate effective transport properties (gas diffusivity, electrical conductivity, permeability, and Knudsen diffusivity), revealing that heat treatment reduces CL porosity, enhances structural consolidation and electrical conductivity stability, and mitigates delamination. Overall, none of the aforementioned studies have considered the effect of compression on the transport mechanisms within the CL. However, as the site where electrochemical reactions occur directly, compression-induced changes in the transport properties of the CL exert a direct impact on cell performance. Accurate quantification of such variations in the transport coefficients within the CL is critical for improving the prediction of fuel cell performance and the optimal design of assembly pressure, a research gap that has not been adequately addressed to date.

Among the components of PEMFC, the GDL exhibits the largest deformation due to its smallest elastic modulus. On the one hand, an appropriate assembly force is beneficial for reducing the contact resistance at the interface between the GDL and the BP. On the other hand, the gas, electrical, and thermal transport in the GDL are also affected by compression [12]. Extensive research has been conducted on measuring or simulating these transport properties (such as gas diffusivity, permeability, and electrical/thermal conductivity) in GDL. Ercelik et al. [13] innovatively resolved the non-uniformity of the GDL computationally efficient 2D models of local nickel foam slices from the imaged structure. The results show that, compared to the conventionally used carbon substrate, the nickel foam sample demonstrate a high degree of uniformity and isotropy and that it has superior structural and mass transport properties. In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have focused on the influence of compression. Li et al. [4,14] reconstructed GDL’s 3D microstructure under non-uniform rib–channel compression via a custom compression fixture and XCT, comprehensively investigating structural/transport properties (thickness distribution, porosity, tortuosity, diffusivity, permeability, electrical/thermal conductivity, liquid water transport). Their simulations show TP-direction (through-plane) diffusivity and permeability are lower than IP-direction (in-plane) values. To assess GDL transport properties across varying compression ratios, Chen et al. [15] integrated 3D stochastic reconstruction, Lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) simulations, and theoretical formulas for serial transport elements. In this study, the thickness of the GDL under various compression ratios were measured firstly and porosity is then calculated. Corresponding computational domains were established according to the porosity of the GDL at different compression ratios. The results showed compression negatively affects GDL mass transport (primary cause: increased tortuosity leading to higher gas/water transport resistance), yet concurrently enhances electrical conductivity by reducing bulk and contact resistance. From the aforementioned studies, it can be found that obtaining the compressed microstructure is a prerequisite for acquiring transport coefficients. Existing compressed GDL porous structures are mostly obtained by experimentally scanning compressed GDL or randomly reconstructing GDL with low porosity. Direct experimental methods are costly and not conducive to parameterized research (compared to stochastic reconstruction methods). Meanwhile, the method of randomly reconstructing GDL with low porosity struggles to reflect compression-induced microstructural changes, such as local carbon fiber contact.

In fact, besides the GDL and CL themselves, the electrical/thermal conduction mechanisms at the GDL-BP interface are also significantly affected by compression. Currently, numerous studies have been conducted on the contact electrical/thermal resistance (CR/TCR) at the BP-GDL interface. Marceli et al. [16] measured the contact resistance, and then an analytical model was developed based on experimental data. Liang et al. [17] developed a comprehensive 3D finite element model to study the effects of coating, welding, and dimensional errors on CR, revealing the fabrication process’s influence (especially welding and forming characteristics) on CR. However, numerical simulation studies based on the real interface microstructure (reconstructed from profilometer data) have not been reported yet. Our group [18] proposed a TCR prediction approach for rough surfaces, involving contour profiler-based measurement of actual rough topography and subsequent reconstruction for numerical analysis of mechanical/thermal contact performance. It provides a potential solution to this problem. It is worth noting that the GDL-BP interface constitutes an essential component of the FEM-CFD framework established in this study.

In summary, as listed in Table 1, complex heat conduction, electrical conduction, gas diffusion, and permeation behaviors exist within the GDL/CL and at the GDL-BP interface. Their macroscopic transport properties are essentially determined by the microstructure. In existing microscale studies, the influence of compression has not been fully considered, especially in the catalyst layer region. Conducting finite element mechanical simulations based on reconstructed or scanned original microstructures can yield compressed microstructures with higher accuracy, on the basis of which various transport coefficients can be further studied and obtained. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no scholars have yet proposed the aforementioned framework for fuel cell porous electrodes to investigate compression-induced changes in transport coefficients. Therefore, this study intends to establish a research framework ranging from microstructure reconstruction to finite element mechanical simulation, and further to computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulation of macroscopic transport properties.

Table 1.

Various Transport Processes in Porous Electrodes of PEMFC.

2. Framework Detail

This section will sequentially introduce the reconstruction or scanning method for the microstructure of the fuel cell porous electrode, the finite element model for studying compressive deformation, and the CFD model for studying various transport processes in the microstructure.

2.1. Microstructure Reconstruction

From a microstructure perspective, this study focuses on the transport processes within the GDL, CL, and at the BP-GDL contact interface. The following sections will, respectively, introduce the microstructure modeling methods for these three different locations.

2.1.1. Gas Diffusion Layer

The random reconstruction algorithm for the porous structure of carbon paper is based on the following assumptions [19]:

- (1)

- Randomly distributed carbon fibers are treated as cylinders, and their axes are parallel to the x-y plane (in-plane direction). Carbon fibers in the same layer can overlap;

- (2)

- PTFE and binders within the carbon paper are neglected, and “bonded” contact settings are used between carbon fibers to approximate the effect of binders;

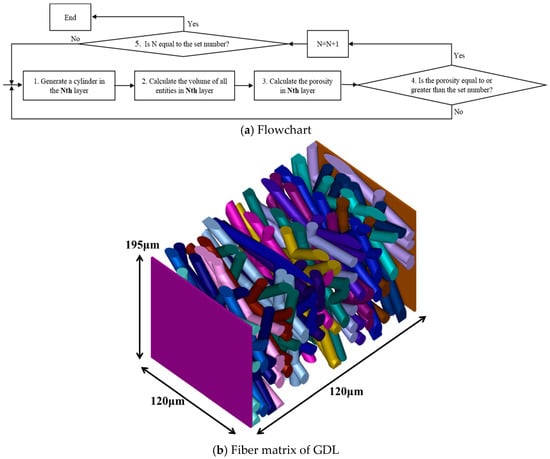

Figure 1a shows the flowchart of the reconstruction of the porous structure of carbon paper, which is implemented using the ANSYS (version of 2022R1) Parametric Design Language (APDL). It is worth noting that in the first step, the Boolean operations need to be performed on the carbon fibers to realize the overlap of carbon fibers in the same layer, and the fibers are truncated within the in-plane space of 120 μm × 120 μm. Figure 1b presents the microstructurally reconstructed carbon paper, with two plates placed on the upper and lower surfaces of the GDL to facilitate the application of boundary conditions.

Figure 1.

GDL microstructure reconstruction.

2.1.2. Catalyst Layer

The random reconstruction algorithm for the CL structure is based on the following assumptions:

- (1)

- Carbon particles are ideal and uniform spheres, and mutual overlap between them is allowed;

- (2)

- The ionomer forms a thin film uniformly coated on the surface of carbon spheres;

- (3)

- The porous structure inside carbon particles is ignored, and changes in particle shape are not considered.

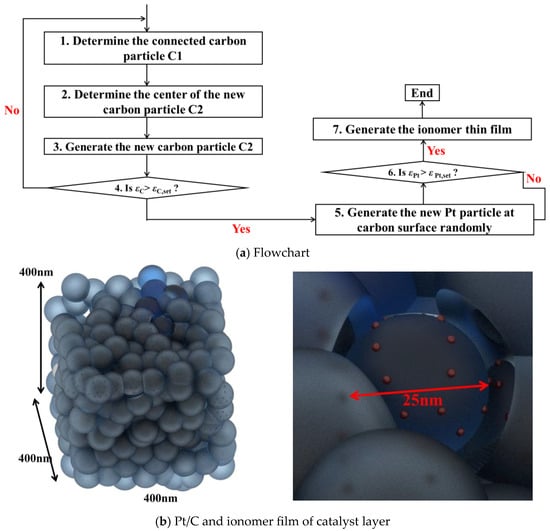

Several algorithms for reconstructing CL structures have been reported in the literature. The most basic and core step is the reconstruction of carbon chains. This paper adopts the reconstruction model developed by Inoue and Kawase [20], which is based on the preparation process of primary carbon chains. In this reconstruction model, a single parameter is proposed to control the shape of the carbon skeleton, enabling convenient and effective control of the morphology of the reconstructed carbon chains. Figure 2a shows the steps of implementing this reconstruction algorithm, where the growth of aggregates is controlled by the inter-particle distance and probability function [20]. Finally, based on the generated carbon particles, Pt particles and annular electrolyte regions can be randomly generated on their spherical surfaces. Figure 2b shows the microstructurally reconstructed catalyst layer and a magnified view of its Pt/C.

Figure 2.

CL microstructure reconstruction.

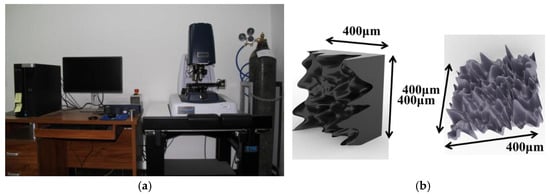

2.1.3. Contact Surface Between GDL and BP

Figure 3a shows the surface topography measurement setup used in this study, which consists of a Bruker white-light interferometric profilometer (Bruker GT-K 3D, Berlin, Germany), a TMC pneumatic vibration-isolation table (nitrogen supplied) to minimize vibration-induced measurement disturbances, and the Vision 64 software for data processing. During measurement, the specimen was placed flat and secured on the scanning stage. A 2.5× objective was used, providing a single-scan field of view of 4.2 × 3.8 mm. To ensure representativeness, measurements were repeated at multiple locations on each specimen for consistency comparison. A representative sub-area of 0.4 × 0.4 mm was then cropped from the original field of view in Vision 64, and the corresponding 3D surface point-cloud data were exported. Before export, planar leveling was applied to remove sample tilt and eliminate its influence on height statistics, followed by point-cloud refinement. Finally, the reconstructed rough surfaces were generated based on the measured 3D point-cloud data. The rough surface reconstructed in this way is based on the actual measurement results of the sample rather than assumptions; thus, the simulation results are more reliable. In this study, the interpolation function in COMSOL 6.2 software is used to obtain the parametric surface, and the final reconstructed rough surface microstructures of the BP and GDL are shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Rough surface microstructure reconstruction of BP and GDL. (a) Bruker GT-K surface topography measuring instrument. (b) Rough surface microstructures of BP (left) and GDL (right).

2.2. Solid Mechanical Simulation

In the present study, the compressive deformation of the GDL/CL and the GDL-BP interface is regarded as elastic deformation [21,22], and plastic deformation of carbon fibers is ignored. This section will present the corresponding elastic mechanics governing equations and the corresponding boundary conditions.

2.2.1. Governing Equations

(1) Equilibrium equations:

(2) Geometric equations:

(3) Constitutive equations:

where σ (Pa) denotes the normal stress, τ (Pa) represents the shear stress, Fi (N·m−3) stands for the body force, ε is the normal strain, and γ is the shear strain. Subscripts i, j, and k denote the x, y, and z coordinates, respectively. In the constitutive equations, λ (Pa) is defined as the first Lame constant, G (Pa) as the shear modulus (also referred to as the second Lame constant in solid mechanics), and e as the trace of the strain tensor, corresponding to the sum of normal strains in three mutually perpendicular directions. The expressions for these parameters are given below:

where E (MPa) is the Young’s modulus and ν is the Poisson’s ratio.

The elastic moduli and Poisson’s ratios of the materials involved in the three calculation regions, such as the GDL microstructure (i.e., fibers), bipolar plate, ionomer, and Pt/C, are listed in Table 2. In a practical PEMFC assembly, the clamping pressure must not be excessively high, as this could cause carbon fiber fracture and subsequent damage to the GDL. Within the pressure range below 3 MPa, carbon fiber deformation is generally regarded as elastic—a linear elastic deformation model that has been widely adopted in numerous previous studies [21,22,23], and the present work draws on these prior investigations.

Table 2.

Material properties values [2,23].

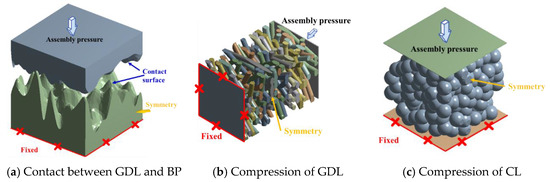

2.2.2. Boundary Conditions

Figure 4 shows the calculation domains corresponding to the compressive deformation of different microstructures in this study. The corresponding boundary conditions are marked in the figure. In the through-plane direction, one side is set as a fixed boundary, and the other side is applied with an assembly force. The other four sides of the calculation domain are set with symmetric constraints, i.e., no normal displacement is allowed. For the BP-GDL contact surface and the GDL fiber solid array, complex changes in the contact state (between carbon fibers, and between BP and GDL) occur during the compression process, so it is necessary to reasonably set the corresponding contact detection conditions. Due to the strong nonlinearity of this process (caused by sudden changes in the contact state), the compaction force needs to be gradually increased during the mechanical simulation.

Figure 4.

Solid mechanical simulation.

2.3. CFD Simulation

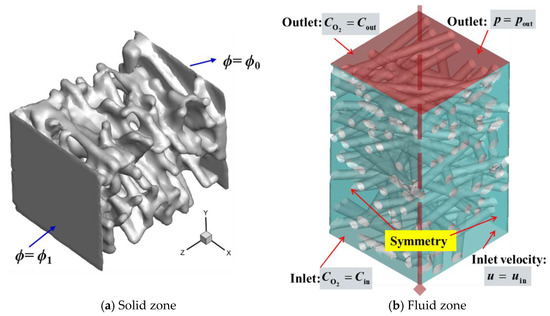

Based on the deformed microstructure, the simulation of the transport processes in the corresponding regions can be carried out accordingly. Among them, the conduction of charge and heat mainly occurs in the solid skeleton, while the transport of water and gas mainly occurs in the pore fluid region. Therefore, this section will, respectively, introduce the models of the transport processes in the solid and fluid regions, and present the corresponding governing equations and boundary conditions. The GDL is selected as an example for illustration below; similar methods can be used for modeling the CL region and the BP-GDL contact surface. During the operation of PEMFC, the transport phenomenon in the through-plane (TP) direction is often more critical and influential compared to that in the in-plane (IP) direction. Therefore, in the present study, only the transport property in TP direction is considered.

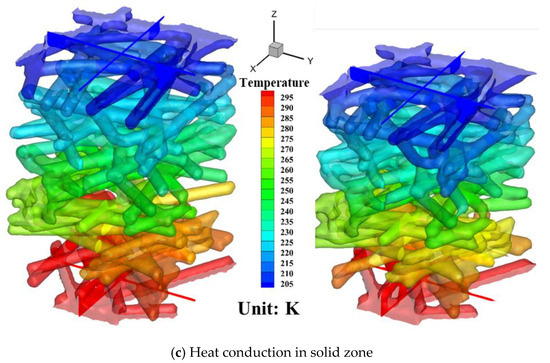

2.3.1. Solid Zone

In the simulated deformed microstructure, the contact at many internal interfaces is point contact. These sharp positions usually result in low-quality meshes during mesh generation (a key step in CFD). To better handle mesh generation efficiently and improve accuracy, the Wrap method is used for the solid region in this paper to generate a simplified geometric surface, as shown in Figure 5a. On this basis, Dirichlet boundary conditions can be applied to both ends of the GDL, respectively. The conduction process in the GDL fiber skeleton is described by the Laplace equation, as follows:

where κ0 is the intrinsic electrical conductivity (S·m−1) or thermal conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) (this value can be canceled out and its value does not affect the results), and ϕ is the electric potential (V) or temperature (K). The normalized effective conductivity, fκ, can be calculated by the following equation [24]:

where l (m) is the thickness of the compressed GDL, the z-direction is the through-plane direction, the xy-plane is the in-plane direction, and A (m2) is the area of the end faces. The subscripts 0 and 1, respectively, represent two end faces. The concepts of thermal resistance or electrical resistance are commonly used in experiments; thus, the normalized conduction resistance is defined in this paper as follows:

Figure 5.

CFD simulation.

2.3.2. Fluid Zone

Based on the deformed microstructure, the fluid domain is extracted as shown in Figure 5b. This study investigates the gas diffusion and liquid water permeation behaviors in the fluid domain, and obtains the normalized effective gas diffusivity and intrinsic permeability. For gas diffusion, according to Fick’s diffusion law:

where D0 (m2·s−1) is the intrinsic diffusivity (this value can be canceled out and its value does not affect the results), and C is the gas concentration (mol·m−3). During the simulation, fixed gas concentrations (Cin and Cout in Figure 5b) are specified at the inlet and outlet end faces, respectively. The normalized effective gas diffusivity, fD, can be calculated by the following equation:

Meanwhile, assuming that the tortuosity τ and diffusion coefficient satisfy the following relationship:

where θ is the porosity. Thus, the tortuosity τ can be further calculated by combining Equations (13) and (14) as follows:

As derived from Equations (12) and (13), the proportional scaling of oxygen concentration exerts no influence on the relative distribution of oxygen concentration, nor does it change the value of normalized effective gas diffusivity. In the present study, the inlet and outlet oxygen concentrations are set to 3 mol·m−3 and 1 mol·m−3, respectively.

For the permeation process, the velocity (uin) and pressure (pout) are specified at the inlet and outlet, respectively. Then, according to Darcy’s law, the intrinsic permeability K (m2) of the GDL is calculated by the following equation:

where uin (m·s−1) is the specified inlet velocity, taken as 0.01 m·s−1; μ (kg·m−1·s−1) is the dynamic viscosity of liquid water, taken as 0.001003 kg·m−1·s−1; Δp (Pa) is the pressure difference between the inlet and outlet; and l (m) is the thickness of the gas diffusion layer.

3. Results and Discussion

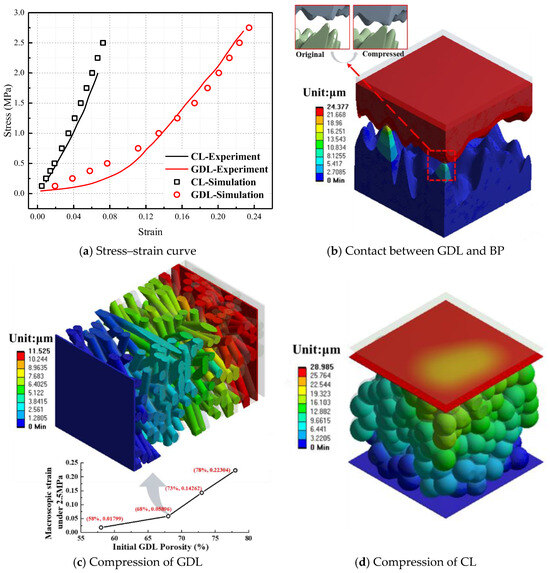

3.1. Deformation of Microstructure

To verify the accuracy of the mechanical model in this paper, Figure 6a shows a comparison between the simulated stress–strain curves of the GDL and CL and the experimental values [25,26]. The two are in good agreement, indicating that the results of this paper can truly reflect the state of the porous electrodes in the fuel cell stack after being compressed. Figure 6b–d show the results of compressive deformation of the three regions under a pressure of 2.5 MPa. The color of the regions represents the displacement value at the corresponding position, and the transparent shadow shows the original structure before deformation (for easy comparison). The red regions indicate the maximum deformation (i.e., displacement) during compression, corresponding to the side adjacent to the load application. In contrast, the blue regions represent zero displacement, which is associated with the applied fixed boundary conditions (see Figure 4). Although the material properties assumed in this study are linearly elastic (i.e., plastic deformation is excluded), the stress–strain curves derived from the statistical analysis of microstructures (Figure 6a) exhibit nonlinear characteristics. This implies that the GDL and CL behave as nonlinear materials at the macroscale, which is consistent with experimental measurements. In macroscale mechanical simulations, this nonlinear curve can be further incorporated into the material property definitions for improved accuracy.

Figure 6.

Deformed microstructure.

As shown in Figure 6b, under the compaction force, the rough structures on the surface of the bipolar plate and the carbon paper will be in further contact. From the locally magnified view (with different colors denoting independent structures), it can be seen that compression brings the two initially separated surfaces into contact. More local surface contact between the two is beneficial for forming pathways for electron and heat conduction, thereby reducing the contact resistance/thermal resistance between the BP and GDL. It can be seen from Figure 6c that the maximum strain value of the GDL here is 11.525 μm, and the corresponding strain is approximately 0.059 (calculated from the initial thickness of 195 μm). It is worth noting that the deformability of the GDL is directly related to its porosity; the result shown here is for a low porosity (68%). The present study supplements the macroscopic strain rates under different porosity conditions (in Figure 6c). It is straightforward to envision that the pore regions behave as if they have an elastic modulus of zero, whereas the solid carbon fiber components possess a considerably high Young’s modulus. Notably, higher porosity corresponds to a lower proportion of the solid skeleton, resulting in reduced resistance to compressive deformation. The influence of the changes in its microstructure on the transport process will be discussed in detail below. Figure 6d shows the microstructure of the catalyst layer after compression. Obviously, the entire Pt/C and electrolyte regions become more compact to a certain extent after being compressed. The pores in the catalyst layer will inevitably decrease, thereby increasing the resistance to the transport of reaction gases. This phenomenon can be validated by the normalized effective gas diffusivity calculated in the subsequent section. However, at the same time, more connections between carbon spheres are beneficial for expanding the electron conduction pathways (see the normalized effective conductivity presented in the subsequent section).

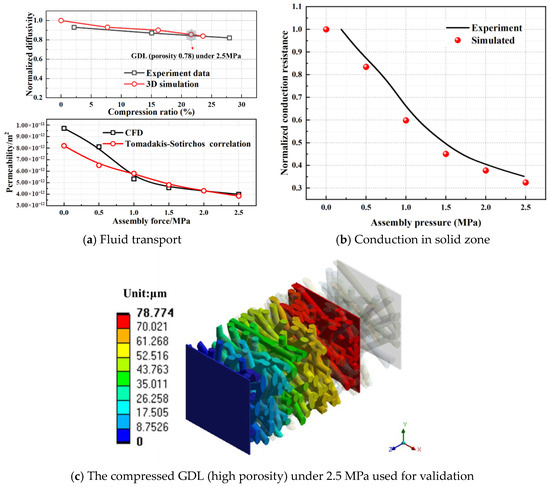

3.2. Transport Property After Compression

For both the GDL and CL, compression exerts a multitude of influences on material properties and structural characteristics. Two specific effects stand out as the most critical determinants of the overall performance of PEMFCs: (a) Compaction of the pore structure, which gives rise to an increase in gas diffusion resistance across the layer; (b) Strengthened electron and proton conduction efficiency, which stems from the enhanced connectivity of the solid-phase components within the layer. A comprehensive elaboration of these two key effects is presented here. Figure 7 shows a comparison between the macroscopic transport coefficient values obtained by simulation in this paper and the experimental values [27,28,29]. The normalized effective gas diffusivity and intrinsic permeability of the fluid domain, as well as the normalized conduction resistance of the solid domain, corresponding to the GDL under different compaction forces, are obtained and shown in Figure 7a,b, respectively. The simulation results agree well with the experimental data, which verifies the accuracy of our model. In our mechanical simulations, the compression ratio reaches 23.6% at a compression force of 3 MPa; accordingly, this value was set as the upper limit of the compression ratio. Notably, the compression forces investigated in relevant literature generally do not exceed this range. Within this scope, the deviation of the normalized effective coefficients is no more than 4.7%. It is worth noting that the GDL employed in the experiments featured a high porosity of approximately 80%. Given the pronounced effect of porosity on the measured properties, the high-porosity GDL was also adopted for the validation process, and its deformation behavior under a compression force of 2.5 MPa is illustrated in Figure 7c.

Figure 7.

Model validation.

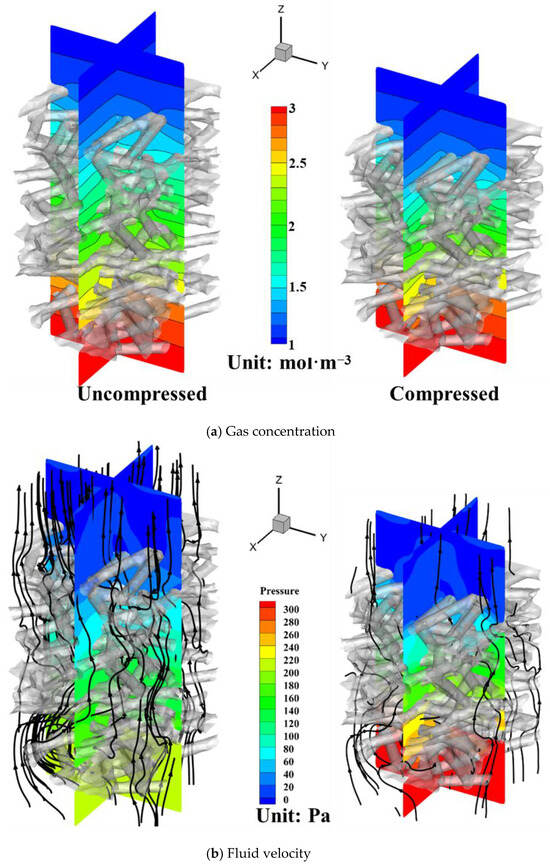

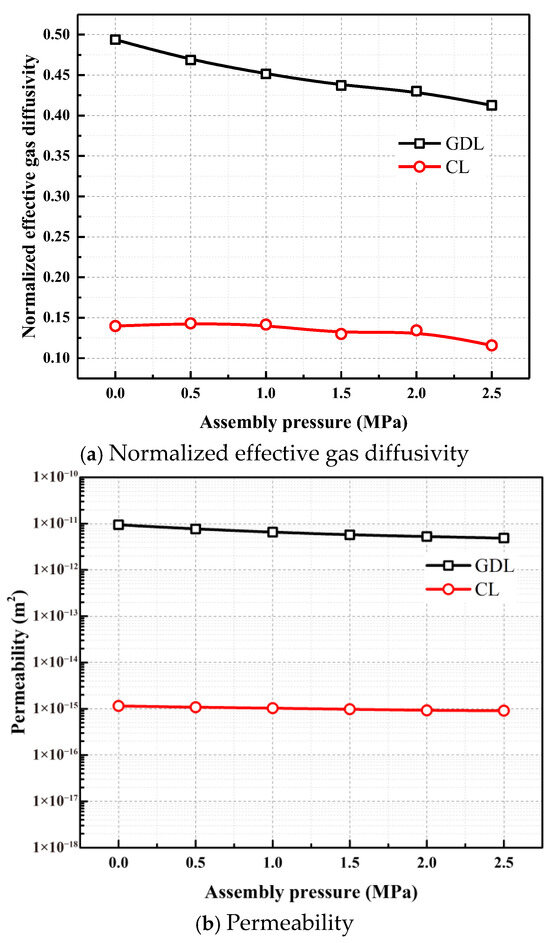

In addition, it can be seen from Figure 7a that the normalized effective gas diffusivity decreases with the increase in the compression ratio. Figure 8a shows the oxygen concentration distribution in the GDL under the original state and 2.5 MPa; the complex pore distribution causes the concentration contour lines to become tortuous. Under 2.5 MPa, fD decreases by 16.5% compared with the original state, with the corresponding tortuosity increasing by 19.7% (calculated via Equation (15)). After compression, the pore size decreases, leading to an increase in gas diffusion resistance. Figure 9a simultaneously illustrates the variation in normalized effective gas diffusivity (fD) of both the GDL and CL as a function of the compression force. It can be observed that the fD for the CL decreases with increasing compression; however, the magnitude of this reduction (dropping from 0.140 to 0.116) is smaller than that of the GDL. This observation corresponds well with the relatively small deformation degree of the CL presented in Figure 6a. Similarly, the permeability also decreases with the increase in the compaction force; the reduction in the pore region significantly increases the flow resistance. This can be observed from the pressure contour map in Figure 7b. Under the initial state and a compaction force of 2.5 MPa, the permeability of the gas diffusion layer is 9.7 × 10−12 m2 and 4.0 × 10−12 m2, respectively; that is, the permeability decreases by 58.8% under a pressure of 2.5 MPa. In Figure 9b, the logarithmic coordinate axis reveals that the permeability of the CL is approximately four orders of magnitude lower than that of the GDL. Additionally, it exhibits a slight decrease with increasing compression force.

Figure 8.

Transport phenomenon inside GDL.

Figure 9.

Transport properties of GDL and CL.

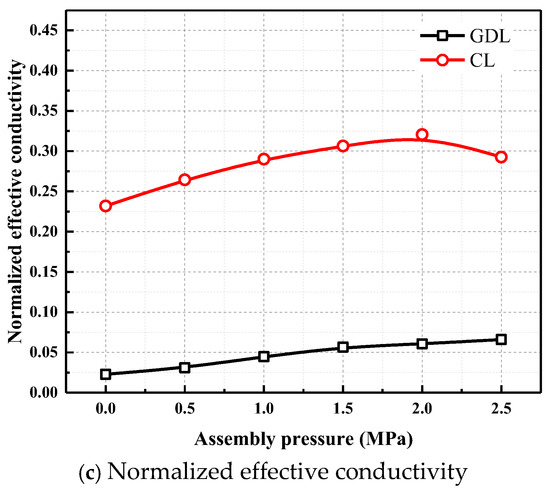

In contrast, the heat/electric conduction in the solid domain follows the opposite law to that in the fluid domain. As shown in Figure 7b, with the increase in the compaction force, the conduction resistance decreases gradually, i.e., the normalized effective conductivity increases gradually. This is because more internal fiber contact points are formed, and the conduction path between the inlet and outlet ends becomes shorter, both of which help to reduce the conduction resistance. Under 2.5 MPa, fκ is 2.9 times the original state. Figure 9c shows that the normalized effective conductivity (fκ) of the CL is higher than that of the GDL, which is consistent with the lower porosity of the CL (indicating a larger solid-phase fraction). At a compression force of 2.5 MPa, the fκ of the CL is increased by 26.2% compared with the original state, while the simulation results reveal that the fκ at the GDL-BP interface is enhanced by 35.0% relative to the original state.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes a comprehensive combined FEM-CFD research framework centered on microstructure reconstruction, aiming to systematically investigate the influence of compression on the transport properties of porous electrodes (GDL, CL) and GDL-BP interface in PEMFC. The key conclusions are as follows:

- The microstructure reconstruction methods for different regions of PEMFC porous electrodes are reliable. It lays a solid foundation for subsequent mechanical and transport simulations.

- Under 2.5 MPa compression, GDL is compressed from its initial thickness of 195.0 μm to 183.5 μm, corresponding to a macroscopic strain of approximately 0.059 while the CL undergoes a smaller deformation. Both, however, become significantly more compact, with obvious changes in internal pore structure and component contact state.

- For the fluid zone, GDL’s normalized effective gas diffusivity decreases by 16.5% and intrinsic permeability (from 9.7 × 10−12 m2 to 4.0 × 10−12 m2) decreases by 58.8%, under 2.5 MPa. For the solid zone (heat/charge conduction), compression increases internal contact points and GDL’s normalized effective conductivity under 2.5 MPa is 2.9 times the original value.

- Due to its lower porosity compared to the GDL, the CL exhibits lower diffusivity and permeability but a higher thermal conductivity. Additionally, the changes in its transport coefficients under compression are less pronounced than those of the GDL, which is consistent with its smaller compressive deformation.

5. Future Outlook

From the results of the present study, it can be found that there exists an inherent trade-off between the enhanced charge and heat conduction efficiencies and the increased mass transfer resistance arising from compression. Given that both temperature distribution and mass transfer behavior exert significant influences on the electrochemical reaction kinetics of PEMFCs, it is necessary to further establish a macroscale 3D multiphysics simulation framework to capture their synergistic effects. This aspect, however, exceeds the research scope of the current microscale investigation. A promising avenue for future research would be to integrate the transport coefficients of compressed electrodes derived from this work into such a macroscale model, thereby quantitatively assessing the comprehensive impact of compression on the overall electrochemical performance of PEMFCs.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.Z.; Software, Z.T.; Validation, L.C.; Formal analysis, Z.W. and Y.W.; Investigation, Z.Z. and Y.D.; Resources, Z.T. and L.C.; Data curation, R.Z.; Writing—original draft, Z.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Z.Z., Z.T. and W.T.; Visualization, X.Z.; Supervision, W.T.; Project administration, Y.D.; Funding acquisition, W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study is supported by the Young Scientists Foundation of National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Number 52506103, the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Numbers BX20240285M and 2025M770627, and the S&T Program of Energy Shaanxi Laboratory, Grant No. ESLB202408.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tamilarasan, S.; Wang, C.-K.; Kuan, Y.-D.; Shih, Y.-C.; Stachiv, I. Machine learning as a catalyst for PEMFC optimization: A comprehensive review from flow fields to system integration with a multiscale perspective on research and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, S.-J.; Cheng, J.-H.; Guo, H.-B.; Tao, W.-Q. A comprehensive system simulation from PEMFC stack to fuel cell vehicle. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, D.S.; Pinto, A.M.F.R. A review on PEM electrolyzer modelling: Guidelines for beginners. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.-T.; Wei, L.; Lyu, J.; Hu, C.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Modeling study on anisotropic transport properties of PEMFC GDLs facilitated by XCT. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.-T.; Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Modeling study on liquid water transport dynamics in PEMFC GDLs facilitated by X-ray CT. Fuel 2026, 403, 136097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bai, F.; He, P.; Li, Z.; Tao, W.-Q. A novel cathode flow field for PEMFC and its performance analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 24459–24480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, H.M. Numerical investigation of effective thermal conductivity of gas diffusion layer of the PEM fuel cell. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2023, 85, 1356–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Shahgaldi, S.; Qin, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, X. Modelling of mechanical microstructure changes in the catalyst layer of a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 29904–29916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Katayama, S.; Makino, S.; Inoue, G. Influence of the catalyst layer and carbon structure on the cell performance: Simulation of the reaction and mass transport in a PEFC. J. Power Sources 2026, 661, 238556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kang, H.; Yim, S.-D.; Sohn, Y.-J.; Lee, S.G. Revelation of transport properties of ultra-thin ionomer films in catalyst layer of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells using molecular dynamics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 598, 153815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, M.; Vesely, M.; Capek, P.; Paidar, M.; Bouzek, K. High-temperature PEM fuel cell electrode catalyst layers part 1: Microstructure reconstructed using FIB-SEM tomography and its calculated effective transport properties. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 413, 140133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A.C.; Berning, T.; Kær, S.K. The Effect of Inhomogeneous Compression on Water Transport in the Cathode of a Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. J. Fuel Cell Sci. Technol. 2012, 9, 031010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercelik, M.; Ismail, M.S.; Ingham, D.B.; Hughes, K.J.; Ma, L.; Pourkashanian, M. Efficient X-ray CT-based numerical computations of structural and mass transport properties of nickel foam-based GDLs for PEFCs. Energy 2023, 262, 125531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Gao, S.; Liu, H.; Hao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, L.; Jiang, H.; Hu, C.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Linking 3D microstructure evolution to anisotropic transport in channel-rib induced non-uniformly compressed PEMFC GDLs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 179, 151715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, W.; Ning, T.; Meng, L.; Yin, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Wang, C. Effect of GDL compression on PEMFC performance: A comprehensive cross-scale study. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, L.; Chamoret, D.; Mancini, E.; François, X.; Meyer, Y.; Candusso, D. Contact pressure in the proton exchange membrane fuel cell: Development of analytical models based on experimental investigation and a posteriori design of experiments. J. Power Sources 2024, 617, 235158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Qiu, D.; Peng, L.; Yi, P.; Lai, X.; Ni, J. Contact resistance prediction of proton exchange membrane fuel cell considering fabrication characteristics of metallic bipolar plates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 169, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.-J.; Ren, X.-J.; Dai, Y.-J.; Li, S.; Tao, W.-Q. Study of thermal contact resistance of rough surfaces based on the practical topography. Comput. Fluids 2018, 164, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeefard, M.H.; Molaeimanesh, G.R.; Nazemian, M.; Moqaddari, M.R. A review on microstructure reconstruction of PEM fuel cells porous electrodes for pore scale simulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 20276–20293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, G.; Kawase, M. Effect of porous structure of catalyst layer on effective oxygen diffusion coefficient in polymer electrolyte fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2016, 327, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Um, S. Influence of external clamping pressure on nanoscopic mechanical deformation and catalyst utilization of quaternion PtC catalyst layers for PEMFCs. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Luo, M.; Zhang, H.; Zeis, R.; Sui, P.-C. Solid mechanics simulation of reconstructed gas diffusion layers for PEMFCs. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, F377–F385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, P.; Dai, Y.-J.; Jin, P.-H.; Tao, W.-Q. Study of the mechanical behavior of paper-type GDL in PEMFC based on microstructure morphology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 29379–29394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gao, F.; Du, Q.; Jiao, K. Transport properties of gas diffusion layer of proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Effects of compression. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 178, 121608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekian, A.; Salari, S.; Tam, M.; Oldknow, K.; Djilali, N.; Bahrami, M. Compressive behaviour of thin catalyst layers. Part I-Experimental study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 18450–18460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, M.F.; Roth, J.; Fleming, J.; Lehnert, W. Diffusion Media Materials and Characterisation; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, T.J.; Millichamp, J.; Neville, T.P.; El-kharouf, A.; Pollet, B.G.; Brett, D.J.L. Effect of clamping pressure on ohmic resistance and compression of gas diffusion layers for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2012, 219, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomadakis, M.M.; Robertson, T.J. Viscous permeability of random fiber structures: Comparison of electrical and diffusional estimates with experimental and analytical results. J. Compos. Mater. 2005, 39, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhu, L.; Clökler, C.; Grünzweig, A.; Wilhelm, F.; Scholta, J.; Zeis, R.; Shen, Z.-G.; Luo, M.; Sui, P.-C. Experimental validation of pore-scale models for gas diffusion layers. J. Power Sources 2022, 536, 231515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.