Abstract

Energy deficits have been a major challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), particularly in Nigeria. Consequently, the integration of renewable energy (RE) is a crucial strategy for achieving energy transition goals and addressing climate change issues. Therefore, this article investigates the technical, energy, economic, and environmental impact of PV/Wind/BS/Converter, a standalone hybrid energy mix for electrifying a single-family residential building prototype in multi-regional parts of Nigeria. This study aims to examine the renewable energy potential of three locations using HOMER Pro. The results indicate that Kano exhibits the lowest economic performance indices, with a net present cost (NPC) of USD 32,212.52 and a cost of energy (COE) of USD 0.6072/kWh, followed by Anambra (NPC: USD 45,671.68; COE: USD 0.8609/kWh) and Lagos (NPC: USD 47,184.62; COE: USD 0.8706/kWh). Technically, this study shows that the higher the renewable potential of a site, the lower the energy cost and vice versa. The sensitivity cases of key energy parameters—including solar PV cost, wind turbine cost, wind speed, solar radiation, and inflation rate—were considered to compare multiple scenarios and assess renewable energy potential variability under certain decision-making conditions. Economically, the Kano system shows the feasible capital cost of the energy produced, replacement cost, and operation and maintenance cost (O&M) for wind turbines, compared to the nil cost for Anambra and Lagos. Environmentally, the energy systems revealed 100% renewable fractions (RFs) with zero emissions at the three sites under study, which can enhance Nigeria’s energy transition plan and help in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Integrating RE supports the successful implementation of the recommended energy policy strategies for Nigeria.

1. Introduction

Global electricity consumption and climate change problems have greatly increased in recent years. This trend is attributed to the surge in urbanisation, industrialisation, and global population growth. The consumption of fossil forms of energy is becoming hazardous to human health, has serious environmental implications, and is subject to supply shortages and price volatilities [1]. These have caused a global energy crisis. More narrowly, developing nations, most especially in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) regions, are battling an energy shortage, which has contributed to the dwindling of industrial production and socio-economic growth [2]. This is, of course, a difficult-to-address energy problem in African nations due to weak policy frameworks and the lack of technology and financial institutions to assist in electricity affordability and accessibility compared to developed countries around the world. In general, the African continent is significantly affected by energy poverty in both urban and rural areas. Traditional fuel sources are creating further damage to the ecosystem [3], despite government initiatives and policies to ensure power accessibility by incorporating renewable energy sources to boost access and promote sustainable socio-economic growth. To date, over 60 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa are still affected by the energy poverty crisis, representing nearly half of the continent [4]. Power from the national grid, coal, oil, and gas are mostly unreliable, some of which increase greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that result in climate change and global warming [5]. Unstable electricity has hindered production processes and posed a serious threat to environmental health and economic growth over the years. Hence, electricity is crucial for socio-economic growth and for enhancing sustainable development. Moreover, electricity plays a significant role in Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while energy and accessibility are key drivers of a sustainable economy, essential for bridging inequality gaps, improving social well-being, and promoting national growth and development [6]. Energy sustainability plays a crucial role in alleviating poverty and improving the living standards of the population. Therefore, the integration of renewable energy resources would make a significant contribution to ameliorating the energy crisis of the country [7].

Hybrid renewable energy systems (HRESs) have been applied in various sectors in recent years. Oladigbolu et al. [8] proposed an off-grid energy system of PV/Wind/DG/Battery for the electrification of rural health care in Mokwa, the northern part of Nigeria, using the Homer tool. The optimal configuration showed an NPC of USD 16,457 and a COE of USD 0.259/kWh with a further emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) of 1304 kg/year, thereby creating more pollutants hazardous to environmental health. Amuta et al. [9] investigated the HES of PV/DG/Battery/wind for 95 buildings and four shops in rural community electrification in Nigeria. The system configuration revealed tremendous CO2 emissions, and the hybrid system had a net present cost of USD 54,496 and a levelised cost of energy of USD 0.08/kWh. Similarly, the techno-economic evaluation of a grid-connected PV/Grid/Wind/DG/Battery of a hybrid energy system was studied for a remote Southern Australian Coastline with carbon emissions of about 174.647 tons, NPC of USD 4.65, and COE of USD 0.196/kWh. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions bring about the continuous deterioration of environmental health and further result in climate change [10]. Furthermore, the techno-economic–environmental impact of PV/Wind/BGG/BS/DiG, using the Enhanced Combined Dispatch (ECD) tool, was investigated for community energy demand in Sabon-daga village, in the northern part of Nigeria [11], with increasing pollutant emissions. Also, for sustainable rural agricultural development, a hybrid energy system was studied for the configuration of solar PV/DG/Wind/Biomass/BS for an agricultural building in a remote village in Nigeria [12], where CO2 emissions were harmful to the farm ecosystem. In Rejuwa village of Tanzania, an Improved Chaos Grasshopper Optimiser (ICGO) was employed for the hybrid energy system (HES) comprising photovoltaic (PV), wind, and fuel cell components [13]. However, the ICGO tool demonstrated limited flexibility in its interface. Ukoima et al. [14] investigated the technical, economic, and environmental viability of a hybrid energy system of solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage (PV/Wind/BS) for Okorobo-lle town in the Adeni Local Government Area (LGA) of Rivers state in Nigeria, using HOMER Pro software for the assessment [14]. Additionally, an off-grid energy mix of solar PV/Wind/Fuel cell/H2 and techno-enviro-economic feasibility was assessed for community energy consumption in the Riyadh area of Saudi Arabia, yielding an NPC of USD 2,500,000 and a COE of USD 0.135/kWh [15]. Moreover, a hybrid renewable energy system comprising Wind/H2/Electrolysis/Battery/Converter was evaluated to meet rural community electricity demand in Billerahalli, Karnataka, India, using HOMER software for a techno-financial assessment [16]. Similarly, [17] investigated the techno-economic viability of a PV/Wind/Battery/Fuel cell configuration for transportation applications in a rural area of northern Alberta, Canada. The optimal system reported an NPC of USD 550,000 and a COE of USD 0.675/kWh.

From the above-mentioned literature, it can be deduced that most of the studies conducted in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries were based on community or rural electricity consumption. Despite growing interest, the existing literature does not sufficiently address the adverse climatic conditions of the region. Hence, the novelty of this study rests in the examination of the multi-regional climatic variation by exploring the renewable energy potential of the country, and it is the first of its kind. Secondly, this study focuses on improving the energy accessibility of low-income residential households to reduce energy poverty in the African context. Thirdly, it aims to comprehensively assess the technical performance, electricity production, economic feasibility, and environmental implications of standalone energy systems. Solving these problems would not only provide clean and affordable energy to resolve the power poverty of the region, but doing so would also help in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG7 and 13) and enhance the ambitions regarding the energy transition in the region. Therefore, this study centres on three main regions in Nigeria.

Kano state is located in the northern central region, Anambra state is situated in the southeastern part of the country, and Lagos state lies in the southwestern region of Nigeria. This study aims to bring about an evaluation of on-site renewable resources and their integration to ensure reliable, clean, and sustainable energy for residential purposes. This would automatically improve the living standards of low-income citizens and the socio-economic optimisation of the nation, rather than the current, absolute dependence on an oil and gas-based economy [18,19]. Nigeria, located on the western coast of West Africa, is the largest country in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The country is rich in renewable energy resources, including solar, wind, hydroelectric, and biomass power [20]. The country has over 23 billion barrels of crude oil, 4293 billion m3 of natural gas, 31 billion barrels of Tar sands, 10,000 MW of hydropower, and 2.7 billion tonnes of coal and lignite [21], to mention a few. Despite the energy potential of the nation and electricity initiatives by the government, the country has been unable to keep up with rapid population growth and rising electricity demand due to persistent techno-economic and political challenges within the national power grid, which delivers less than 13 gigawatts (GW) of electricity, resulting in limited access to power [22].

Therefore, to meet the energy deficits of Nigeria, the exploration of renewable energy options cannot be overemphasised to provide clean, affordable, and sustainable electricity for the growing demand. The main purpose of this work is to evaluate the optimal sizing of an off-grid, standalone energy mix to provide clean, sustainable, and reliable electricity for a prototyped residential household in three different climatic classifications. In an attempt to achieve this, the building electricity load is calculated, renewable energy resources are harnessed, and input parameters are processed through optimisation in the Hybrid Optimisation of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER) software (version 3.16, 64-bit). The optimisation iteration focused on three objectives: reduction in NPC, optimisation of COE, and maximisation of appliances’ electrical load.

The aim is to promote clean energy consumption and contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7, which seeks to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030 [23]. The Energy Transition Plan (ETP) [19] from fossil fuel-based to renewable options is imperative in attaining this universal goal. This will also enable Nigeria to double the rate of energy efficiency by 2030 by upgrading energy infrastructures to innovative and modern technologies through renewable energy technologies. Moreover, collaborative efforts are being made to improve the nation’s access to emission-free energy through research and innovative energy infrastructures. Achieving the energy transition goal would also enable Nigeria to combat climate change (Goal 13) simultaneously. Consequently, the consumption of eco-friendly energy options will automatically reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which will decrease climate change and global warming effects such as natural disasters, flooding, wildfire, and so on [12,23]. Table 1 presents a detailed summary of existing studies on the design and operation of on-grid and off-grid energy systems in various regions and countries.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed works focusing on Sustainable Development Goals—Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and Goal 13 (Climate Action) [23].

1.1. Motivation of This Study

The key interest motivating this study originated from the growing demand to model and simulate off-grid energy systems that are capable of integrating a solar panel, wind turbines, a battery, and a converter system for clean energy consumption. It is imperative to solve energy problems in developing African nations, especially in Nigeria, in terms of clean energy, economic feasibility, environmental sustainability, and technical adaptability to the local situation to achieve the energy transition goal. This work is motivated by the dire need to effectively model microgrid energy systems that will not only resolve the unreliable nature of national grid electricity but also enhance the integration of renewable energy resources to achieve the energy transition plan and Sustainable Development Goals.

1.2. Identified Research Gap

Despite the growing research output regarding off-grid energy mixes, such as solar PV/Wind/BS/Conv., crucial gaps remain in the hybrid energy literature, which include the following:

- i.

- Much of the existing literature lacks a holistic approach that itemises technical and energy–economic–environmental (3E) impacts on achieving energy transition plans (ETPs) [19].

- ii.

- There is a lack of sufficient research output on the variability of environmental factors and energy resources—specifically solar radiation and wind power—across different Nigerian climates and their impact on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 7(affordable and clean energy) consumption and Goal 13 (climate action) [38].

- iii.

- Limited work focuses on exploring the renewable energy resource potentials of different locations in Nigeria. Also, the use of Hybrid Optimisation of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER) Pro, developed by the National Renewable Laboratory (NREL) in the US, has proven its flexibility, adaptability, versatility, and robustness in solving microgrid energy problems, as it is adaptable to local areas and is utilised for this study.

- iv.

- There is insufficient renewable energy literature in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) considering the diverse climate characteristics of the region.

1.3. Contribution of This Work

This study, therefore, aims at hybrid optimisation to conduct a technical and economic–energy–environmental (3E) analysis of RESs for residential buildings in Kano, Anambra, and Lagos states for sustainable energy developments in Nigeria. These include the following:

- i.

- Shifting electricity consumption from fossil fuel, non-renewable to sustainable, economically viable, cleaner energy production free of emissions.

- ii.

- This work will not only create information for lawmakers but also provide environmentally friendly, techno-economic, and energy opportunities for energy investors and the public across the country.

- iii.

- This study aims to bring about economic optimality by transitioning from a fossil fuel-based economy to sustainable options via the hybrid energy resources (HES) of the country.

- iv.

- This study aims to investigate the technical advantage of promoting renewable energy options by utilising Nigeria’s diverse climate to generate reliable electricity for the growing demand.

- v.

- This research aims to bring about intergovernmental awareness for residential householders in Nigeria and other developing nations and regions that are also grappling with energy problems regarding the opportunities of a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES).

The remaining parts of this paper are as follows: Section 2 entails the methods and materials adopted for the hybrid energy mix. The experimental results of the optimisation procedures used are presented in Section 3. Section 4 provides a discussion of this study. Section 5 presents the recommendations of this study. Finally, Section 6 presents conclusions and outlines directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

In this work, the hybrid optimisation of a multiple energy mix of a PV/Wind/BS system is used for a prototype residential building in three zones under different meteorological conditions in Nigeria. Optimisation processes are carried out using the Hybrid Optimisation of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER) pro package to ensure that viable, feasible, and emission-free energy can be generated. This study focuses on achieving a sustainable energy transition from oil and gas-based systems to cleaner alternatives in Nigeria.

2.1. Description of Energy System

The residential building under study is hypothetically located in three states of Nigeria (Kano, Anambra, and Lagos). The building consists of three bedrooms, one sitting room, four toilets, and a kitchen. The basic electrical appliances include a washing machine, an electric cooker, a blender, standing fans, air conditioning, a laptop, lighting, a refrigerator, a television, and an electric iron. The residential building’s daily energy consumption load profile stands at 45.6336 kWh/day, based on the occupancy time of the house under study. It has a peak load in the early morning between 6:00 and 7:00 a.m. of 5.231 kWh/day. When the occupants are preparing to go to their workplaces, a peak load occurs between 6:00 and 8:00 p.m. at 6.6392 kWh/day, during which the house is fully occupied. The primary justification for selecting a single-family three-bedroom for this study is that it represents a common residential typology among low-income households in Nigeria, and typically accommodates a nuclear family consisting of parents and children. This contrasts with the situation of medium-to high-income households, which typically prefer larger residential units with approximately four to five bedrooms. Hence, for a household comprising only a husband and wife (newly married couple), the daily load profile peaks at 5.231 kWh/day during the morning period (06:00–07:00), when the appliances such as a blender, cooker, and pressing iron are used for food preparation and clothing before departing for work. Afterwards, the house is unoccupied until the evening when both the husband and wife return from work around 5 pm, and the appliances’ load profile peaks again at 6.639 kWh/day between 6:00 and 8:00 pm, when appliances such as the air conditioner, fan, TV set, laptop, and washing machine are put to use. Fewer appliances, such as refrigerators and LED bulbs, are often in operation throughout the day for food preservation and security purposes, respectively. In a family with children, the children leave for school while the parents go to work almost at the same time, and in most cases, they return home around 5:00–6:00 pm in the evening.

2.2. Site Description

The sites (Kano, Anambra, and Lagos) are states located in Nigeria in the western part of the African continent, with a growing population of over 200 million people [12], with a total land area of 923,768 m2, lying between the Equator and the Tropic of Cancer, positioned at latitude 10°00′ N and longitude 8°00′ E [39]. Additionally, Kano is situated in the northwest region, which is classified as a tropical savanna climate. At the same time, Anambra state is located in the southeast zone of the tropical wet and dry belt, and Lagos is positioned in the southwest in the tropical savanna climate classification, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Site metrological characteristics of locations.

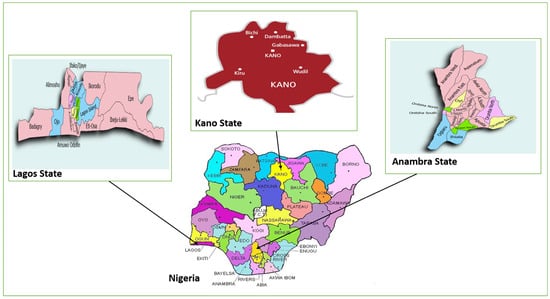

Despite the abundant oil and gas resources of the nation, which rank it as Africa’s biggest economy, Nigeria is still facing electricity problems, with over 90 million people living without power, out of which 17 million live in urban areas, while 73 million dwell in rural communities [12]. Due to the decrease in crude oil reserves and the associated emission potentials, it has become crucial for the country to migrate toward renewable energy alternatives for cleaner and sustainable energy demand, since the nation is richly endowed with abundant hydropower, wind power, biomass, and natural gas, to mention a few [44,45]. According to the report by Statista in 2022, the public services and commercial sector utilised 28,498 terajoules (TJ), the industrial sector consumed 26,167 terajoules (TJ), and residential buildings consumed 61,416 terajoules (TJ) of electricity. Yet, a significant effort needs to be made for sustainable domestic energy consumption [46,47]. Apart from the high cost of operation and maintenance of diesel generators, there are grid-connected areas with long periods of power outages. It is therefore imperative to find alternative energy systems to overcome these challenges [9]. Figure 1 shows a map of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the three regions under consideration for this study.

Figure 1.

This map represents the three regions under study in Nigeria.

2.3. The Load Profile of the Energy System

From the household electricity consumption point of view, the appliance load profiles of the evaluated energy system are pivotal in the modelling, simulation, and optimisation processes. For this study, data on daily energy demand for household appliances are extracted. This hybrid energy system is modelled to meet the 3-bedroom residential electricity demand. The electricity consumption () of the studied residential building in the three locations is defined as the summation of two types of electrical loads. Firstly, the electricity consumption for building appliances, such as lighting and electrical devices, is the total of the rated power (multiplied by the period during which they are operated) for all the electrical appliances. It is expressed mathematically as follows [24]:

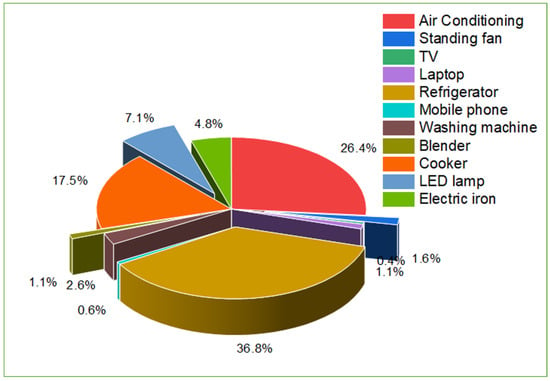

The building’s average daily energy demand is approximately 45.6636 kWh/day, mainly attributed to household appliances. These include washing machines, televisions, blenders, and heating devices (electric iron and cooker), lighting systems (LED lamps), and cooling equipment such as (refrigerator, air conditioners, and standing fans), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Appliances’ energy consumption for the residential household.

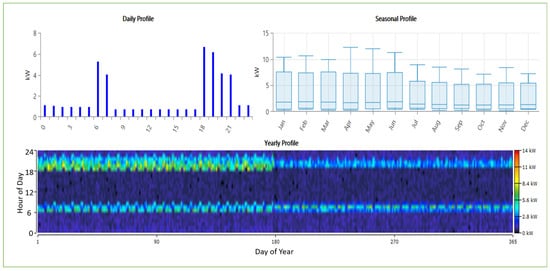

The building’s daily profile represents the energy demand of the building. The seasonal profile illustrates electricity consumption across the two primary seasons in Nigeria: the rainy and dry seasons. The yearly profile consists of the energy demand on an annual basis, from January to December. The daily energy demand profile has a peak load in the morning between 6:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. when the occupants make use of some appliances before going to work and a peak load in the evening between 6:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. when all the occupants have returned from work. As a result of the daily, seasonal, and yearly irregularity of renewable energy resources (RES), the hybrid energy system makes use of a converter and battery storage system to equilibrate the electricity load distribution around the year. Figure 3 represents the load profile of the building: daily energy demand, seasonal energy demand, and annual load profile.

Figure 3.

This figure represents the load profile of the building: daily energy demand, seasonal energy demand, and annual load profile.

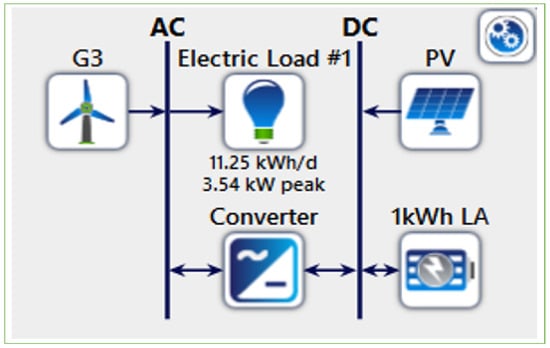

2.4. Input Parameters

The hybrid energy system uses a solar photovoltaic system, a mini wind turbine, lead–acid battery storage, and a converter. As a result of the intermittent nature of solar radiation and wind resources, the system uses a battery to store excess electricity during peak periods and supply it back to the system during periods of low renewable energy. These systems are put in place to ensure cleaner, steadier, and sustainable electricity. Figure 4 shows the schematic design of the hybrid energy configuration under study.

Figure 4.

Schematic design of HES.

The hybrid renewable energy (HRE) system considered in this study comprises solar photovoltaic (PV), wind turbine (WT), battery storage system (BS), and converter components, as summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Technical and economic parameters of photovoltaics, wind turbines, battery storage, and converters in Nigeria [1,11,48].

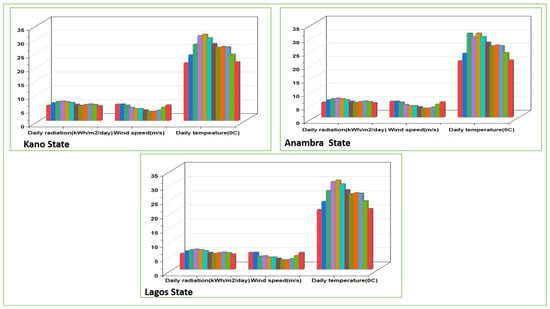

Furthermore, the site locations are richly endowed with renewable resources such as solar radiation, wind power, and temperature. Thus, the adoption of renewable energy options would enable residential householders to overcome electricity challenges and climate change issues in Nigeria [45,49]. Figure 5 illustrates the global horizontal irradiance (daily solar radiation), wind speed, and daily ambient temperature for the locations.

Figure 5.

Meteorological information for Kano State, Anambra State, and Lagos State.

2.4.1. Solar Resource

The sites have high solar radiation, with an approximate annual average global horizontal irradiance (GHI) of 5.47 kWh/m2/year. The NASA Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource (POWER) database, comprising over 22 years of meteorological data, was used for the study locations. The metrological data were collected and used for simulation processes. Moreover, a generic flat-plate solar panel (1 kW), with an initial cost of USD 1800, a replacement cost of USD 1800, and an operation and maintenance cost (O&M) of USD 18.00, was utilised for the simulation. Solar photovoltaic (PV) cells are dependent on many parameters for their sensitivity. These include the size of the electric load profile connected to the system, surface temperature, the intensity of solar radiation incident on the photovoltaic (PV) cell, and the manufacturer’s specifications of hybrid components, among others [50]. The solar radiation can be expressed mathematically as follows [51]:

where is the photovoltaic derating factor (%), is the rating capacity of the solar photovoltaic array under the standard test condition (kW), is the incident radiation on the photovoltaic panel array (kW/m2), is the incident radiation under the standard test condition (kW/m2), is the temperature of the photovoltaic panel cell (°C), is the temperature of the photovoltaic panel cell under standard test conditions (25 °C), and is the temperature coefficient of power (%/°C). It is mathematically expressed as follows [52]:

“Equation (3)” explains how HOMER Pro computes the temperature of a PV cell. is the solar radiation that strikes a photovoltaic panel array (kW/m2), is the temperature of the photovoltaic panel cell (°C), is the ambient temperature (°C), is the radiation of the sun at which the NOCT is determined (0.8 kW/m2), is the solar transmittance of the photovoltaic panel (%), is the electrical conversion efficiency of photovoltaic panels (%), is the solar absorptance of the photovoltaic panel (%), is the nominal temperature of the photovoltaic cell (°C), and is the ambient temperature at which the NOCT is determined (20 °C). Furthermore, HOMER Pro utilises a transposition model (TM) to compute the optimum angle from the database so that optimal solar radiation is captured for the production of renewable energy [53]. The incident radiation is expressed mathematically as follows [54]:

where is the ground reflection of solar radiation (W/m2), is the global inclined solar irradiance (W/m2), is the direct beam tilted solar radiation of the sun (W/m2), and is the sky-diffuse tilted solar irradiance (W/m2). The transposition factor () can be mathematically expressed as follows [55]:

where is the incidence angle of the sun, and is the solar zenith angle. Moreover, the incident angle on the horizontal surface is expressed by the following equation [56]:

where is the latitude of Kano, Anambra, and Lagos states; is the hour angle of the sun; and is the incident angle at which the sunbeam hits the normal surface.

2.4.2. Wind Resource

The sites offer tremendous potential for wind power resources, with an annual average wind speed of 4.53 m/s, 4.07 m/s, and 3.81 m/s for Kano, Anambra, and Lagos, respectively, and a monthly average wind speed at 50 m above the surface of the earth over 30 years [51]. In addition, a generic wind turbine (WT), 3 kW capacity, with an initial cost of USD 4000, a replacement cost of USD 3200, and an operation and maintenance cost (O&M) of USD 200.00, was used for the simulation processes. Wind energy is produced through wind turbines by the conversion of wind power into mechanical power and electrical energy. A generic wind turbine (WT) was considered for this work. The mechanical power of a wind turbine is governed by the following equation [8]:

where A is the surface swept by the rotor (m2), is the wind speed (m/s), and is air density (1.22 kg/m3). Thus, the electrical power of a wind turbine, WT is mathematically expressed as follows [8]:

where is the power coefficient of a wind turbine (WT).

HOMER (version 3.16, 64-bit) software computes the wind speed of a wind turbine using input specifications in the wind resource window and the shear window. Thus, the simulation tools use the hub height wind speed calculated by the following equation [51]:

where is the anemometer height (m), is the wind speed at the hub height of the wind turbine (m/s), is the wind turbine’s anemometer height (m/s), is the surface roughness length (m), is the hub height of the wind turbine (m), and is the natural logarithm. Alternatively, the hub height of the wind turbine can be computed using the power law, which is mathematically governed by the following equation [51]:

where

is the power law exponential,

is the wind speed at the hub height of the wind turbine (m/s),

is the wind speed anemometer height (m/s),

is the hub height of the wind turbine (m), and

is the anemometer height (m).

2.4.3. Battery Storage System

A battery storage system was integrated to save the excess electricity produced during the peak energy production period and then supply it when there is a shortage of renewable energy resources due to their intermittent nature. Therefore, a generic lead–acid battery storage system with a nominal voltage of 12 V, nominal capacity of 1 kWh, maximum capacity of 83.4 Ah, capacity ratio of 0.403, round-trip efficiency of 80%, maximum charge current of 16.7 A, maximum discharge current of 24.3 A, and maximum charge rate of 1 A/Ah is considered for this study due to its reliability, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and flexibility for replication anywhere for clean and sustainable energy production. Moreover, a generic battery has capital costs of USD 300, replacement costs of USD 250, and operating and maintenance costs of USD 5 used for this study. HOMER Pro was used to examine the maximum charge of the battery system, expressed mathematically by the following governing equation [51]:

A differential equation can be used to express the maximum quantity of power in a battery system as follows [4]:

The maximum quantity of electric power a battery storage system can store for a certain period is expressed mathematically as follows [4]:

where is the energy at the initial time step (kWh), is the maximum theoretical battery storage capacity (kWh), is the time step of the battery (h), is the quantity of electrical energy stored in the battery storage (kWh), and is the battery storage bank (kW). The maximum storage of the battery charge () equals the maximum current charges. It is governed by the following equation [4]:

where is the battery nominal voltage (V), is the maximum battery storage of current (A), and is the number of batteries in a storage tank. Also, battery charging efficiency is the square root of the battery round-trip efficiency, and it is denoted by the following equation [4]:

where is the battery round-trip efficiency, and is the battery storage system charging efficiency. A battery system loses charge from the storage bank, and this discharge is governed by the following equation [4]:

where is the battery system discharge efficiency.

2.4.4. Converter

The hybrid energy mix under study works with a converter system that converts electrical energy from alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC) or from direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC) [24]. That is, it acts as a rectifier by converting AC to DC power and works as an inverter by converting DC to AC. Hence, it works as an inverter or rectifier as the occasion demands [57]. This study utilises a generic system converter with a lifetime of 10 years, an initial cost of USD 300, a replacement cost of USD 250, and an operation and maintenance (O&M) cost of USD 5 used for this hybrid energy configuration. The generic system converter’s power output () is described mathematically by the following equation [51]:

The efficiency of the converter () can also be defined as the function of power input () and power output (), governed by the following equation [24]:

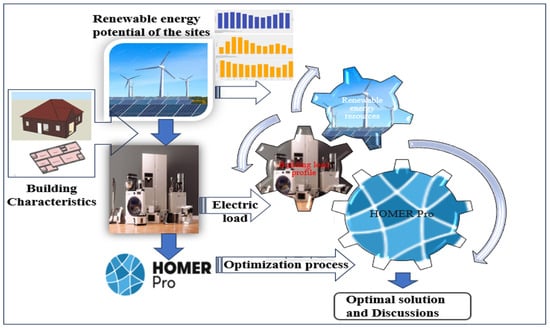

2.5. Optimisation Problem

Optimisation was performed to identify the optimal energy system configuration by minimising cost while ensuring technical feasibility, reasonable capital expenditure, and environmental sustainability. Optimisation iteration in HOMER Pro entails two processes. The first occurs within the search space, employing an algorithm to identify feasible and viable systems, while the second optimisation focuses on finding the configuration with the lowest system cost [51,58]. HOMER (version 3.16, 64-bit) software iterates a range of simulations of hybrid energy systems, which include solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage, to meet the energy demand of the household. The optimal energy solution aims to provide the lowest net present cost (NPC) and cost of energy (COE) and minimise CO2 emissions, depending on the energy configuration. Furthermore, NPC shows the general cost of the investment, operation, and maintenance of the HES over the system’s lifetime. The process starts by importing climatic information such as wind speed, solar irradiance, the temperature of the site locations, appliances’ load profile, and the cost components of the renewable energy technologies to be processed by the HOMER simulation tool. The energy system is sorted by the simulation process based on predefined parameters to search for the best techno-economic output. In addition, the optimisation procedure is performed to determine the optimal energy configuration, taking into account its viability, emission-free, and lowest capital expenditure (CAPEX), and the results are compared on a techno-economic and environmental impact basis [5,58]. The systematic approach for the optimisation framework of this work on residential building energy demand is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of proposed methodology.

2.5.1. Net Present Cost (NPC)

The net present cost (NPC) of the energy system is defined as the economic metric used to investigate the cost of energy configuration options over the project’s lifespan. It takes into consideration the present cash flow and the future cost of the energy investment. Thus, it is expressed mathematically as follows [28,52,59]:

where denotes the annualised inflation rate (%), N is the project’s lifetime (yrs), is the total annualised cost ($), is the interest rate, is the nominal interest (%), and CRF is the capital recovery factor ($).

2.5.2. Cost of Energy (COE)

The cost of energy (COE) is defined as the average cost per unit kWh of the electricity generated by the hybrid energy system. For HOMER Pro to estimate the COE, it divides the annualised cost of energy produced by the total electrical load. HOMER software evaluates the COE of an HRES as follows. It is expressed mathematically as follows [51]:

where is the total annualised cost of the hybrid energy system ($/year); is the boiler marginal cost ($/kWh); is the total thermal load served (kWh/yr), but if the system does not serve the thermal load (), it will equate to zero; and is the total electrical load served (kWh/yr).

2.5.3. Total Electricity Production

The total electrical energy produced is estimated as the total amount of electricity generated on an annual basis. The total electrical energy produced is estimated as the summation of electricity output from each of the hybrid energy (HE) components of the given system [60]. Moreover, total electrical energy production () is the ratio of total excess electricity () to the total excess electricity fraction () and is governed mathematically by the following equation [51]:

where is the total electricity produced (kWh/yr), and is the total electricity (kWh/yr).

2.5.4. Carbon Emission Index

Renewable energy sources are known to be a clean, viable, and environmentally friendly solution. However, due to their lifespan, they absorb embodied carbon from extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and maintenance processes. HOMER software estimates the embodied carbon emissions mathematically using the following equation [51]:

where (kWh) is total energy, and (kgCO2/kWh) is the total energy and emission factor.

The cost of environmental hazards in terms of the emissions of CO2 gas can be expressed by the following equation [61]:

where denotes the social cost of carbon ($/ton CO2) which can be considered as USD 70/tonCO2. The total cost of the hybrid energy system is considered over the lifespan of ‘n’ years, that is over 25 years of the hybrid energy project under the influence of the average inflation rate ‘r’. The total benefit (TB) is calculated using the following equation [61]:

where I is the income/year, $/year.

Therefore, this study targets techno-economic, environmental, and energy solutions for residential energy consumption for sustainable development in Nigeria to achieve its energy transition goal by 2060 [19,22,62]. This energy solution is designed to be emission-free, thereby mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and is mathematically described by the following equation [63]:

Also, the cost of environmental hazards () caused by greenhouse gases (GHGs) and annual residential electricity demand () is expressed by the following equation [63]:

where is the state of emission factor for CO2, CH4, and NO2 in kg/kWh, respectively, and the socio-economic cost of carbon is denoted by ($/year). Therefore, since the hybrid energy systems under consideration are targeted to be eco-friendly, this would minimise carbon emissions into the environment, thereby enhancing the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in terms of the clean and affordable energy consumption goals of 2030 [23], carbon neutrality [64], and the attainment of the energy transition goals of Nigeria by 2060 [19,64].

2.6. Model Assumptions and Limitations

The authors used HOMER Pro (version 3.16, 64-bit) for this study. The core justifiable reason for using HOMER Pro is that it is user-friendly, and it has a robust capacity for modelling, optimising, and analysing the techno-economic environmental feasibility of multiple energy sources. In general, the main reasons for using HOMER pro include the following:

- Techno-economic analysis: HOMER pro has the capacity to compute the cost of energy (COE), net present cost (NPC), and operating cost of the lifecycle of different hybrid energy mixes. It identifies the most feasible, viable, and cost-optimal energy solution for a given system.

- Optimisation of hybrid energy system (HES): HOMER software can simulate hundreds of thousands of feasible energy components such as PV, wind, battery, and converter components. It sizes the components to establish optimal configurations and to meet the specific load profile of a given application.

- Tackling various energy resources: This software is designed in such a way to model and compute renewable energy resource variability and intermittency using site-specific meteorological data for a long period of time.

- Sensitivity analysis: In HOMER Pro, the uncertainty of and variability in different parameters, such as the discount rate, inflation rate, and renewable penetration, can be calculated for an energy investor to examine various scenarios that can occur over the lifespan of a project.

However, despite the aforementioned advantages of using the HOMER tool, certain limitations remain, including the following: First, Homer is designed to work on site-specific data. As such, generic data of a site with peculiar features can limit the accuracy of the data. Hence, geographical variability can limit the usage of the result. Secondly, it can only make use of previous weather files, which can limit the accuracy compared to the present meteorological conditions of a given site, and it has a single-year resource data-default setting. Thirdly, the software was designed to focus on a microgrid energy system, which is not suitable for modelling a large-scale energy system.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Techno-Financial Feasibility of HRES

Despite the abundant renewable energy resources of wind, solar radiation, hydropower, and biomass in Nigeria, the financial implications of procuring energy components remain infeasible to many middle-income Nigerians. A Statista report in 2024 [65] stated that the minimum wage in Nigeria stood at approximately USD 44 (NGN 70,000), and the monthly cost of living in Nigeria was estimated at USD 27.8 (NGN 43,200). Therefore, this study tends to analyse the feasibility of the costs of a hybrid energy system of PV/Wind/Battery/Converter, considering the capital, replacement, and operation and maintenance (O&M) costs, and to observe whether it is feasible, especially for low-income citizens. In addition, the hybrid energy systems revealed the techno-economic feasibility of different energy mixes for this study in Kano, Anambra, and Lagos states. The energy systems show the cost of the components of the optimal solution and the energy parameters of the HRES. The best system assessment for the chosen locations was conducted based on the results of the sites. Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 describe the results of the viable and feasible configurations.

Table 4.

HRES comparison for Kano state.

Table 5.

HRES comparison for Anambra state.

Table 6.

HRES comparison for Lagos state.

Generally, the three locations and the optimal systems reveal a 100% renewable fraction (RF), which can be described as the ratio of energy produced by the hybrid renewable system to the energy consumption over a specific period. The higher the renewable fraction (RF), the higher the reliance on renewable energy resources and the lower the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into the environment. The three energy systems, in Kano, Anambra, and Lagos states, under study are regarded as off-grid or standalone configurations.

3.1.1. Technical Comparison of Optimal HRES

Technical Analysis of the Optimal Photovoltaic Arrays

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of power dispatch across the hybrid renewable energy systems components of Kano, Anambra, and Lagos states for their technical viability and feasibility for sustainable energy production. Furthermore, as rated capacity increases, total annual energy also increases drastically. The rated capacity of the PV array rises from 4.33 kW, 9.50 kW, and 10.0 kW, with an increase in total energy production from 7795 kWh/yr, 13,438 kWh/yr, and 14,031 kWh/yr in the Kano, Anambra, and Lagos systems, respectively. Therefore, Lagos’s hybrid configuration achieved the highest energy production, followed by Anambra and Kano. Meanwhile, the Lagos system consists of the minimum hours of PV penetration compared to other regions. Additionally, photovoltaic (PV) penetration can be defined as the average amount of PV output to the average amount of primary load. As PV penetration rises, the rated capacity of PV also increases and vice versa. The Lagos configuration has the highest PV penetration value of 342%, while the Anambra and Kano systems have 327% and 190%, respectively, as depicted in Table 7.

Table 7.

A comparative analysis of the technical parameters of the photovoltaic array across the three locations.

The Technical Feasibility of the Optimal Wind Turbine Systems

Technically, the higher the renewable potential of the site, the higher the technical advantage of such a location. The Anambra and Lagos configurations revealed a nil rating for wind energy resources in terms of maximum output, wind penetration, hours of penetration, capacity factor, mean output, and rated capacity. In contrast, Kano yielded a significantly rated capacity of 3.00 kW, with a total wind energy production of 3175 kWh/yr and a mean output of 0.362 kW. Likewise, wind penetration and the number of hours of penetration are at 77.3% and 6539 h/yr, respectively, as presented in Table 8. Hence, the Kano system is the optimal system that is technically feasible in terms of wind energy resources among the three systems under consideration.

Table 8.

A comparative analysis of the technical parameters of the Wind turbines across the three locations.

Technical Analysis of the Optimal Battery Storage Systems

Battery storage system autonomy is defined as the period during which a battery can supply power without depending on external components. The Anambra system shows the highest number of hours of autonomy at 57.7 h, followed by the Lagos and Kano systems, at 44.0 h and 30.0 h, respectively, revealing that the system can work without depending on external input. Furthermore, another key parameter to examine is annual throughput, which is defined as the total energy a battery storage system can process on a yearly basis. The Lagos configuration has the highest annual throughput of 3429 kWh/yr, followed by the Anambra system at 3400 kWh/yr and Kano at 2602 kWh/yr, as presented in Table 9, showing extensive parameters on the battery storage system of the locations under study.

Table 9.

A comparative analysis of the technical parameters of the battery storage system across the three locations.

Technical Analysis of the Optimal Converter Systems

The converter system is a device that plays a crucial role in the conversion of electricity from alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC) and vice versa for various electrical applications. Narrowly, the rectifier is a device that converts AC to DC, while an inverter, on the other hand, is an electrical device that transforms DC to AC [1]. The Anambra and Lagos systems have a comparably similar converter sizing of 3.3 kW, which is traceable to the identical PV energy outputs of the two cases. On the contrary, the Kano system reduced the sizing of the converter due to the high renewable potential for solar and wind resources compared to the Lagos and Anambra cases. Furthermore, the values of converter operational hours are higher in the Kano, Anambra, and Lagos cases because most power produced is from solar photovoltaic arrays. A comprehensive summary of the three converters is shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

A comparative analysis of the technical parameters of the converter across the three locations.

3.1.2. Optimal System Components

The choice of hybrid energy technologies is essential for sustainable and viable energy consumption. This study makes use of a generic flat-plate photovoltaic (PV), 3 kW generic wind turbine, 1 kW lead–acid battery, and converter system due to their adaptability, Nigeria’s terrains, and the meteorological information about the country. Additionally, the choice of hybrid configuration depends solely on the renewable energy potential of the location. The Kano region has the highest annual average global horizontal irradiance (GHI) of 6.04 kWh/m2/day, an annual average wind speed of 4.53 m/s, and a temperature of 26.36 °C for HRES generation, compared to Lagos with an annual average GHI of 4.74 kWh/m2/day, annual average wind speed of about 3.81 m/s, and annual average temperature of about 25.92 °C, and Anambra state has an annual average GHI of about 4.81 kwh/m2/day, annual average wind speed of about 4.07 m/s, and annual average temperature of about 25.30 °C. Hence, the optimal systems show that solar PV is suitable for all three zones, while wind energy is optimally feasible only for the Kano region. The optimal configurations of the hybrid energy components are given in Table 11 for each of the locations (zones).

Table 11.

Optimal configuration system for Kano, Anambra, and Lagos.

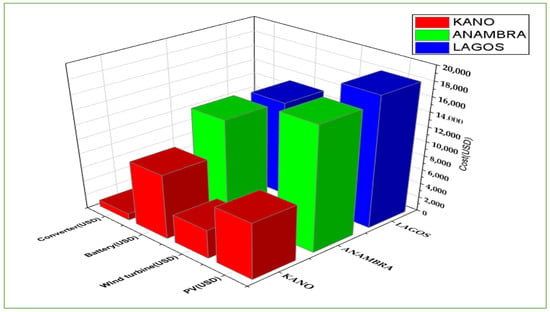

Furthermore, Figure 7 shows the financial metrics of the cost analysis for the three locations. The Lagos and Anambra configurations reveal nil financial implications for the wind turbine, i.e., initial cost, replacement cost, and operation and maintenance costs, due to the lack of wind renewable resources in the locations as compared to Kano state, with abundant solar radiation, wind, and temperature for HRES generation.

Figure 7.

Optimal energy components for the selected sites.

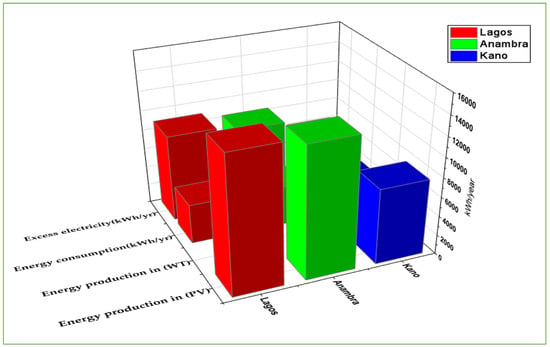

3.1.3. Optimal Energy Parameters

The sustainable production of clean energy for residential uses is the goal of this study. Lagos and Anambra produced energy only with the use of PV at 14,031 kWh/yr and 13,438 kwh/yr of electricity, respectively, due to low wind resources in the location, whereas Kano has high energy potential for both solar and wind energy, which produces 7795 kWh/yr and 3175 kWh/yr of electricity, respectively. The three energy systems consume 4104 kWh/yr of electricity on an annual basis. Additionally, the three locations produced excess electricity, which can be sold to the public or the national grid. This will boost the national grid for sustainable energy consumption in the residential sector in Nigeria. Figure 8 shows the optimal energy parameters of the three locations for this study.

Figure 8.

The energy parameters of the optimal configuration of the sites.

3.1.4. Economic Comparison

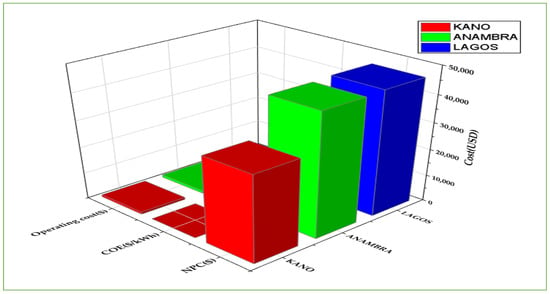

The optimal systems in Kano, Anambra, and Lagos indicated the cost of energy. The energy cost in Kano is much more techno-financially feasible compared to other locations, i.e., Anambra and Lagos states, due to the abundant renewable resource potentials (solar radiation, wind, and high temperature) that are available in Kano. Kano has the lowest net present cost (NPC) of USD 32,212.52, a levelised cost of energy (COE) of USD 0.6072/kWh, and an operating cost of USD 811.34 compared to the Anambra and Lagos systems with an NPC of USD 45,671.68, COE of USD 0.8609/kWh, and operating cost of USD 1087.54 and NPC of USD 46,184.62, COE of USD 0.8706/kWh, and operating cost of USD 1076.78, respectively. Kano exhibits greater renewable energy potential than Anambra and Lagos, which explains its higher cost-effectiveness compared to the other locations (Figure 9). Hence, this study reveals that the higher the renewable potential of the site, the lower the cost of energy and vice versa.

Figure 9.

The energy cost of optimal configurations for the locations.

3.1.5. Carbon Emissions and Energy Sustainability

The roadmap to reliable and sustainable energy in Nigeria mainly consists of the commercial production of renewable energy options, especially the maximisation of abundant solar and wind resources as primary energy sources. The three locations in this study have net-zero emissions (0% kg/yr) of pollutants such as carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), unburnt hydrocarbons (UHCs), particulate matter (PM), sulphur dioxide (SOX), and nitrogen oxides (NOX). Additionally, the Kano, Anambra, and Lagos systems have 100% renewable fractions (RFs) with 100% emission reduction, meaning that the energy configurations depend solely on renewable energy sources (RESs) without the support of non-renewable energy sources (NRESs). Therefore, the three scenarios have absolute reliance on RESs for demand loads. Thus, this enhances optimal system configurations to achieve zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and supports energy transition policies for sustainable energy consumption, as well as ensuring environmental protection.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy System

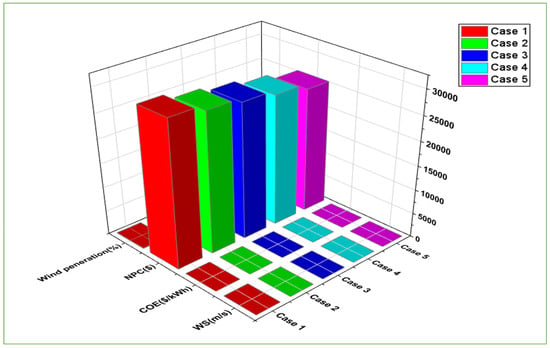

To evaluate the effect of certain variables, a sensitivity analysis is carried out on PV cost (), wind turbine cost (), solar radiation (SR), wind speed (WS), and inflation rate (IR), which are key parameters for the hybrid energy system, as shown in Table 12. These variables contribute greatly to the techno-economic and environmental impact of the hybrid renewable system engendered by renewable energy resources.

Table 12.

Summary of sensitivity analysis parameters and their ranges.

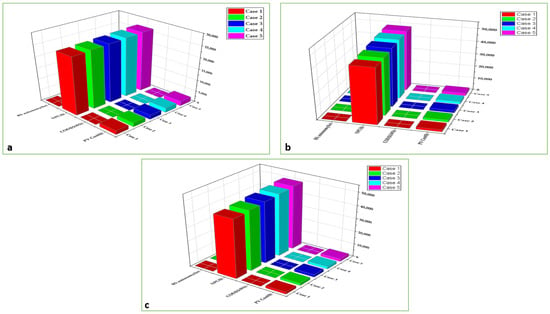

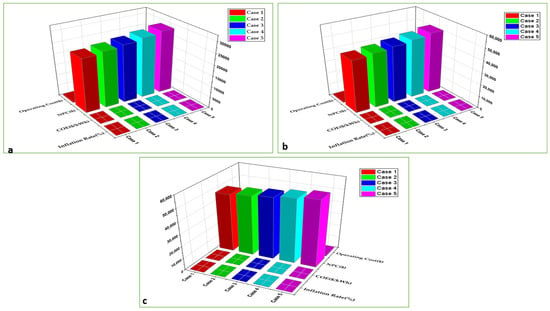

In this study, the effect of solar panel cost was evaluated. The output revealed that a reduction in PV cost would lead to a decrease in the cost of electricity (COE) and the net present cost (NPC), bringing about the financial attractiveness of the energy system. For instance, the PV cost at USD 1700 per kW yielded a COE and NPC of USD 0.479/kWh and USD 25,402 in the Kano configuration, respectively; USD 0.843/kWh and USD 44,722 in the Anambra system, respectively; and USD 0.852/kWh and USD 45,180 in the Lagos system, respectively, with a minimum battery autonomy of 30 h, as depicted in Figure 10. Hence, hybrid energy systems are economically appealing to low-income residential householders in terms of lowering PV cost compared to the PV cost estimated at USD 2,100, yielding a COE and NPC of USD 0.503/kWh and USD 26,684 in the Kano configuration, USD 0.911/kWh and USD 48,335 in the Anambra system, and USD 0.931/kWh and USD 49,380 in the Lagos configuration, respectively, at an inflation rate of 2% and discount rate of 8%.

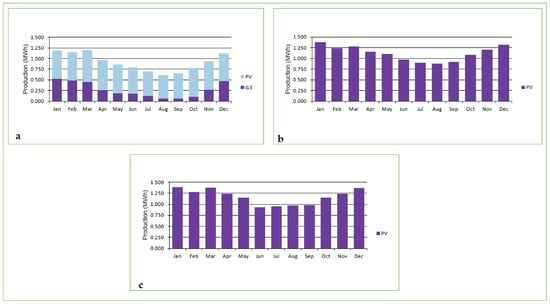

Figure 10.

Sensitivity analysis of solar PV cost as it affects COE, NPC and battery storage (BS) autonomy in (a) Kano, (b) Anambra, and (c) Lagos configurations.

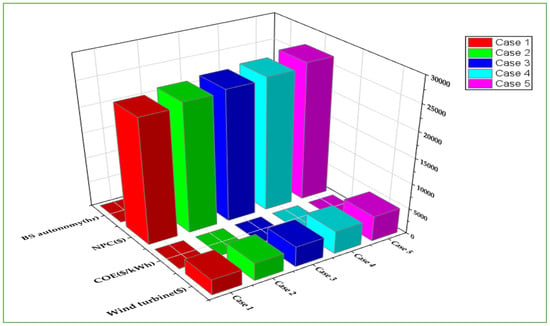

A similar effect was observed on the cost of a wind turbine, ranging from USD 3000 to USD 5000 per kW, yielding a COE from USD 0.46 to USD 0.512/kWh and NPC from USD 24,421 to USD 27,173 and a battery autonomy of 30 h for the Kano configuration. The results show that a lower cost is more economically appealing to low-income Nigerians, as described in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity analysis of wind turbine cost () as it affects COE, NPC, and battery storage (BS) autonomy in the Kano system.

Notably, the effect of solar radiation (SR) GHI on the cost of electricity (COE) and net present cost (NPC) of the systems was also examined. It was observed that lower solar radiation lowers solar PV energy production, while an increase in solar radiation increases energy generation with a drastic reduction in the COE and NPC of the system. For instance, Kano solar radiation ranges from 6.54 kWh/m2/day to 8.54 kWh/m2/day, producing a COE and NPC from USD 0.595/kWh to USD 0.559/kWh and from USD 31,568 to USD 29,667, respectively. Anambra solar radiation was shown to range from 5.31 kWh/m2/day to 7.31 kWh/m2/day and yielded a reduced COE and NPC from USD 0.825/kWh to USD 0.728/kWh and USD 43,790 to USD 38,635, respectively, and Lagos showed an SR from 5.24 kWh/m2/day to 7.4 kWh/m2/day and yielded a COE from USD 0.834 to USD 0.703/kWh and NPC from USD 44,222 to USD 37,313, respectively. Hence, a decrease in the COE and NPC is a result of high solar radiation, as illustrated in Figure 12. The energy system would be favourable to the three regions under study and thereby enhances the living standard of low-income Nigerians by providing clean energy and affordable cost due to the favourable climate and high PV penetration values throughout the system’s lifetime.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity analysis of solar radiation (SR) GHI on COE, NPC, and PV penetration in (a) Kano, (b) Anambra, and (c) Lagos systems.

Furthermore, the wind speed in the Kano region was also critically analysed, revealing an abundance of wind resources. Here, wind speed was assessed, ranging from 5.03 m/s to 7.03 m/s. The results show that an increase in wind speed brings about a decrease in the COE and NPC from USD 0.563/kWh to USD 0.485/kWh and USD 29,852 to USD 25,716, respectively, with wind penetration values ranging from 105% to 222%, as depicted in Figure 13. This output shows the financial attractiveness of using a wind energy solution, creating an opportunity for Nigeria to shift from fossil fuel consumption to cleaner, renewable energy alternatives.

Figure 13.

Sensitivity analysis of wind speed (WS) in terms of COE, NPC, and wind penetration in the Kano system.

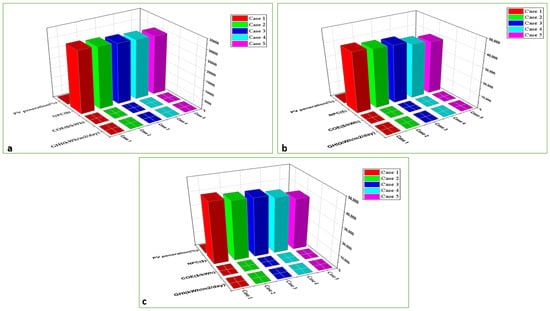

Moreover, a sensitivity assessment was conducted on the inflation rate as it affects the electricity cost, net present cost, and operating cost of a hybrid renewable energy mix. The inflation rate ranges from 1% to 6% for the three regions. The Kano and Anambra systems show a decrease in the COE but an increase in the NPC and operating cost as the inflation rate increases for the 25-year lifespan of the system. However, the Lagos configuration reveals a lower COE and operating cost while the NPC increases, as shown in Figure 14. Hence, the reduction in the inflation rate yields a reduction in the COE and NPC, and this makes investment in hybrid renewable infrastructure appealing to citizens for sustainable clean energy consumption.

Figure 14.

Sensitivity analysis of inflation rate (IR) in terms of COE, NPC, and operating cost in (a) Kano, (b) Anambra, and (c) Lagos systems.

4. Discussion

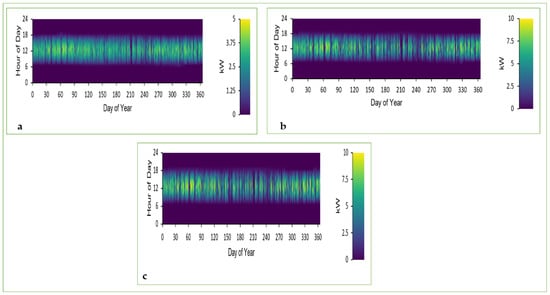

4.1. Energy Production

System energy output is vital in the consideration of a hybrid energy mix to be adopted for residential building applications. The Kano system (PV/Wind/Battery/Converter) produced 4.33 kW from solar panels and 1 kW from wind turbines at an NPC of USD 32,123 and COE of USD 0.607/kWh, which is more technically and financially feasible for low-income householders compared to the Anambra system (PV/Battery/Converter), which generated 9.50 kW from solar panels at an NPC of USD 45,672 and COE of USD 0.861/kWh of electricity, while the Lagos state configuration (PV/Battery/Converter) produced 10.0 kW of electricity at an NPC of USD 46,185 and COE of USD 0.871/kWh. Hence, the higher the renewable potential of a location, the lower the cost of energy. Figure 15 shows power production throughout the year in the solar PV in the three locations under study. Ultimately, sufficient energy is absorbed by the solar panel between 7:00 am and 6:00 pm daily, and excess electricity is stored in the battery storage system and utilised at night to compensate for intermittent solar radiation.

Figure 15.

PV power production on annual basis for (a) Kano system, (b) Anambra system, and (c) Lagos system.

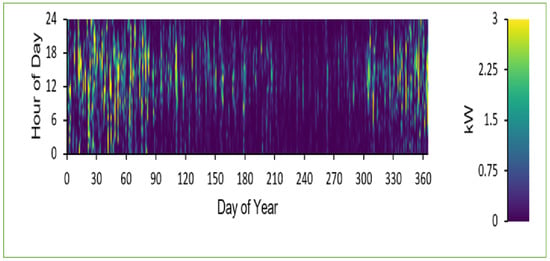

Additionally, the Kano configuration shows wind resource penetration at different periods of the year. In the first 90 days of each year, from January to March and the last 60 days of the year, from November to December, the wind resource absorption in the wind turbine is greater compared to April to October. This revealed the monthly fluctuation in the wind resource potential of the site for energy generation (see Figure 16 and Figure 17a).

Figure 16.

The Kano configuration showing the power output from a generic wind turbine.

Figure 17.

Electricity production in each of the systems: the (a) Kano system, (b) Anambra system, and (c) Lagos system.

Moreover, the energy system configuration for each of the states under consideration ensures steady, reliable, and resilient energy consumption throughout its lifespan, unlike on-grid electricity, which lacks sustainability and is inefficient due to high tariffs. Energy production from these standalone systems is reliable, clean, renewable, and eco-friendly compared to oil and gas-based power systems. This microgrid requires approximately 11 kWh/day and has peak periods of 5.231 kW/day in the morning and 6.6372 kW/day in the evening. The proposed system, showing energy generation, serves the electrical load. Figure 17 shows the solar and wind power output of the optimal configurations and monthly energy production on an annual basis, respectively.

4.2. Technical Analysis

Technically, it was observed from the optimal system results that Kano state has more solar and wind renewable resources compared to those of Anambra and Lagos states. Table 8 and Table 11 and Figure 7 and Figure 8 revealed nil wind energy resources in the Anambra and Lagos regions. It is technically infeasible to site wind energy infrastructure in both Lagos and Anambra states due to negligible wind potential. Technical assessments of wind turbine parameters—including rated capacity, mean output, capacity factor, total production, minimum and maximum output, and wind hour of penetration—confirm this, as shown in Table 8. In contrast, Kano state exhibits optimal values for all parameters, making it a suitable location for wind energy deployment. The technical investigation would also help lawmakers in Nigeria make informed decisions in the positioning of renewable facilities in an appropriate location for optimal techno-financial advantages.

Additionally, the Kano configuration (PV/Wind/Battery/Converter) was technically attractive, comprising 4.33 kW of solar PV, 1 kW of wind power, 30 lead–acid battery units, and a 3.09 kW converter system. the Anambra (PV/Battery/Converter) and Lagos (PV/Battery/Converter) systems were found to be advantageous, with Anambra system comprising 9.50 kW of PV, 45 batteries, and a 3.38 kW converter, and Lagos system comprising 10 kW of PV, 44 batteries, and a 3.27 kW converters.

4.3. Economic Analysis

In terms of the economic implications of these hybrid energy configurations, it is more financially viable and feasible to adopt the PV/Battery/Converter energy mix in Anambra and Lagos states, with a COE of USD 0.861/kWh and USD 0.871/kWh, respectively, while the Kano configuration (PV/Wind/Battery/Converter) produced electricity with a COE of USD 0.607/kWh. Therefore, the Kano system experienced a lower COE due to the abundant renewable energy resources provided by the sunlight and wind in the location. Apart from the cost of energy, capital expenditure (CAPEX) and net present cost (NPC) stood at USD 21,724 and USD 32,213 for Kano and USD 31,613 and USD 45,672 for Anambra, while those of the Lagos system were estimated at USD 32,265 and USD 46,185, respectively.

The standalone system under consideration shows the best economic optimality through the system’s lifetime with steady and sustainable electricity production at affordable costs, unlike the present national grid electricity that is erratic, unsustainable, and epileptic in supply. Hence, the integration of a hybrid energy mix will bring about not only the viable and reliable consumption of electricity at a cheaper cost but also a means of reviving the national power sector into a resilient one.

4.4. Environmental Emissions

The goals of the energy transition plan and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 7 and 13) are to combat the GHG emission problems caused by the consumption of fossil fuels over the years and ensure a sustainable and resilient energy future for Nigerians. The energy mix under study is one hundred per cent renewable and is environmentally friendly with zero operational emissions. Hence, the integration of a renewable energy system into the national energy grid will enhance the stable and viable consumption of clean energy for low-income residential areas and reduce absolute dependence on the electricity grid.

Furthermore, oil and gas-based energy systems involve significant emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), unburned hydrocarbons (UHCs), particulate matter (PM), sulphur dioxide (SOx), and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the surrounding areas, which are responsible for climate change and global warming. Hence, transitioning into a cleaner energy alternative is imperative for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and the energy transition plan/zero-emission target of Nigeria by 2060 [66]. However, the hybrid energy configurations in this study produce clean energy and 100% renewable fractions (RFs), with zero emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the environment. Therefore, the adoption of a policy framework that promotes the large-scale production of renewable energy is imperative to meet the needs of Nigeria’s growing population.

4.5. Practical Implications of PV Penetration and Autonomy as It Affects Consumers

PV penetration is the amount of electricity demand supplied by solar power. For instance, PV penetration in the Kano, Anambra, and Lagos systems has values ranging from 170 to 200%, 317 to 407%, and 228 to 357%, respectively. This implies that the amount of solar power generated by solar PV is sufficient to meet the household’s daily load profile. This brings about steady, reliable electricity, sufficient for the daily load profile, unlike on-grid, which is associated with blackouts and power outages. Furthermore, it also reduces operating costs and environmental pollution compared to a diesel generator system. The standalone system enhances energy planning, reduces electricity bills, improves predictability, and decreases frustration with the fuel price and noise and air pollution associated with gasoline generator configuration. This leads to better living standards and ensures sustainable and reliable electricity for low-income Nigerians.

Similarly, system autonomy simply means the number of hours that home appliances can be powered solely by solar PV or wind turbines with battery storage devices without depending on a diesel generator or grid electricity. For the hybrid energy mix under consideration, it was found that battery autonomy yields output ranging from 30 to 32 h, 57.7 to 61.5 h, and 56.4 to 60.2 h for the Kano, Anambra, and Lagos systems, respectively. The practical implication of this for Nigerian residential households is that it improves reliability during nighttime, enhances comfort and quality of life, reduces operational cost, and reduces power outages, as in the case of diesel generators and grid consumption.

Finally, the combined effects of PV penetration and high battery autonomy on energy policy and the socio-economy are that they decrease the load on Nigeria’s national grid, improve the adoption of the renewable energy transition ambition, reduce urban pollution, and aid in the migration toward sustainable clean energy consumption.

4.6. Technical–Energy–Economic–Environmental Comparison

Moreover, this study also compares techno-financial feasibility with other hybrid energy systems (HESs) in Nigeria and Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries and regions. The existing energy literature [11,12,67] in Nigeria shows a lack of energy production descriptions with further emissions of pollution into the atmosphere, while those of configurations in South Africa [68], Morocco [69], and Algeria [25] give insufficient detail on technical and energy feasibilities, as depicted in Table 13. However, the hybrid system in Biskra, Algeria [24], focuses on rural residential electrification, which is relatively similar to that of Lagos and Anambra states in terms of comprehensive analysis.

Table 13.

Energy cost comparison of the present study with other hybrid systems in Nigeria and across the African continent.

Therefore, the HRESs under consideration holistically illustrate technical feasibility, high potential for renewable energy production, economic effectiveness, and environmental friendliness with zero emissions. The configuration would automatically aid in achieving a zero-greenhouse gas emission policy for sustainable development. The Kano, Anambra, and Lagos systems show sustainable energy production, cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness, technical advantages, and economic benefits in comparison with the existing energy literature. The configuration enables a detailed analysis of hybrid renewable energy feasibility in the Nigerian climate using the three zones, and it can be feasible in other Sub-Saharan African (SSA) regions.

5. Recommendations

The following are recommended to achieve sustainable energy transition goals from oil and gas-based systems to a cleaner, hybrid energy alternative for Nigeria.

- Policymakers should make policies that will encourage the energy transition and adequate implementation strategies.

- The government and private investors should establish companies for producing renewable energy technologies locally to reduce the cost of importation.

- The energy transition plan (ETP) of Nigeria can be implemented by exploring the renewable energy resources of the nation.

- The production of locally manufactured hybrid technologies would also boost the socio-economic status of citizens and create job opportunities for the youth.

- The government should provide incentives and tax holidays for local manufacturing companies of hybrid energy components.

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Goal 7 (affordable and clean energy) and Goal 13 (climate action) can be achieved through the adoption of renewable energy resources as energy alternatives to improve the standard of living of citizens sustainably.

- The introduction of vocational training centres would help in educating the public and stakeholders to enhance the knowledge and know-how of the installation of various smart technologies, thereby creating employment opportunities for Nigerians and improving the standard of living of the citizens.

- Harnessing the renewable energy potential of the nation is a pathway to carbon neutrality, which will enable Nigeria to achieve its net-zero emission goal by 2060.

- An optimisation approach through the use of artificial intelligence (AI) can greatly enhance the accuracy of the hybrid energy system (HES) models and configurations in achieving a sustainable future.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This study shows the design, simulation, and optimisation of HESs for residential household energy demand to overcome energy deficits that many Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, particularly Nigeria, are battling. Therefore, for this work, HOMER tools were used for this analysis, as it is a user-friendly energy software, to investigate the best energy configurations. In sum, this study evaluates the technical, economic, energy, and environmental impact of the hybrid energy mix in the three states of Nigeria for residential energy application. The optimal systems and their associated cost implications for each location were analysed, leading to the following observations. The net present cost (NPC) and cost of energy (COE) vary across the locations. In Kano, the PV/Wind/Battery/Converter configuration yields an NPC of USD 32,212.52 and a COE of USD 0.6072/kWh. In Anambra, the PV/Battery/Converter system records an NPC of USD 45,671.68 and a COE of USD 0.8609/kWh. Similarly, in Lagos, the PV/Battery/Converter configuration results in an NPC of USD 47,184.62 and a COE of USD 0.8706/kWh. The Kano energy system has the best value compared to that of Anambra and Lagos states, which are the three sites under study. Hence, this study reveals that the higher the renewable potential of the site, the lower the energy cost. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted on various energy parameters such as solar PV cost (), wind turbine cost (), solar radiation (SR), wind speed (WS), and inflation rate (IR) to ascertain the energy optimality and robustness of the results. It was observed that lowering the cost of PV and wind turbines reduces the COE, NPC, and operating cost and vice versa. Also, an increase in the renewable energy resources (solar radiation and wind speed) of a location brings about a decrease in the COE and NPC. In addition, the analysis of varying inflation rates indicates that the lower the inflation rate is more financially attractive for the hybrid energy system than excessively high rates. The systems also present 100% renewable fractions (RFs), showing that residential householders, and other sectors such as the commercial sector, industry, and agro-allied enterprises, can adopt the use of renewable energy resources to ensure cleaner, viable, and sustainable energy consumption for their production processes. The implication of the results under the favourable policy framework is that the integration of a hybrid renewable energy mix would not only strengthen and support the national electricity grid but also improve the living standards of low-income citizens and promote sustainable and resilient energy consumption for Nigerians. In addition, this study’s results aim to achieve a net-zero GHG emission policy through the implementation of the recommended strategies for attaining the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and the achievement of the energy transition ambition of Nigeria by 2060.

The authors intend to carry out energy optimisation studies on mixed-use and multi-level high-rise buildings in Nigeria in future research to ensure resilient and sustainable residential energy consumption. Additionally, energy optimisation for residential buildings using artificial intelligence (AI) is another direction that the authors’ future research is also focusing on in ensuring smart and reliable energy consumption in the Sub-Saharan African (SSA) context.

Author Contributions

K.Z.B., Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualisation; R.G.E., Validation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation; A.M., Graphic editing, Visualisation; P.V.G., Writing—review and editing, Visualisation, Investigation; M.A.A., Writing—review, validation, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest concerning this article, authorship, and/or publication of this research.

Nomenclature

| Nomenclature | |

| NPC | Net present cost [$] |

| COE | Cost of energy [$/kWh] |

| O&M | Operation and maintenance [$] |

| Photovoltaic panel cell temperature under standard conditions [°C] | |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| PV cell temperature [°C] | |

| Global solar radiation [kW/m2] | |

| Solar transmittance PV array [%] | |

| Incident radiation on PV [kW/m2] | |

| Incident radiation under standard test conditions PV [kW/m2] | |

| Rating capacity of solar PV under standard test conditions [kW] | |

| PV derating factor [%] | |

| Ambient temperature [%] | |

| Ambient temperature at which NOCT is determined [%] | |

| Nominal temperature of PV cell [%] | |

| Electric conversion efficiency of PV [%] | |

| Global inclined solar irradiance [W/m2] | |

| Solar absorption of PV [%] | |

| Battery charging efficiency [%] | |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| NOCT | Nominal operating cell temperature [°C] |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas [kg/year] |

| Direct beam radiation transposition factor | |

| Transposition models | |

| Ground transposition models | |

| Slope angle between plane and solar radiation | |

| Latitude angle of sun | |

| Declination angle | |

| Air density [kg/m3] | |

| Photovoltaic | |

| WT | Wind turbine |

| TB | Total benefit |

| Latitude hour angle of sun | |

| Solar incident angle | |

| Sun’s zenith angle | |

| Battery power discharge | |

| Battery discharge efficiency | |

| Converter’s electrical power output | |

| AC | Alternating current |

| DC | Direct current |

| Temperature coefficient of power [%/°C] | |

| Environmental damage from greenhouse gas [kg/year] | |

| Cost of environmental damage from greenhouse gas [$/year] | |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| Parameters | |

| Charge and discharge efficiency of BS | |

| Minimum State of Charge (SOC) of BSS [%] | |

| Initial state of charge of BS [%] | |

| BS minimum energy level [kWh] | |

| BS maximum energy level [kWh] | |

| Battery system capital energy level [kWh] | |

| Capital cost of battery system [$/kW] | |

| Capital cost of PV array [$/kW] | |

| Replacement cost of PV array [$/kW] | |

| Capital cost of wind turbine [$/kW] | |

| Replacement cost of wind turbine [$/kW] | |

| Operation and maintenance cost of wind turbine [$/kW] | |

| Replacement cost of PV array [$/kW] | |

| Photovoltaic lifetime [yrs] | |

| Wind turbine lifetime [yrs] | |

| Battery system lifetime [yrs] |

References

- Ba-swaimi, S.; Verayiah, R.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; AlAhmad, A.K.; Abu-Rayash, A. Development and techno-economic assessment of an optimized and integrated solar/wind energy system for remote health applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 26, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takim, S.A.; Nwobi-Okoye, C.C. Measurement of the macro-efficiency of hydropower plants in nigeria using transfer functions and data envelopment analysis. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frnana, F.M.; Kareem, P.H. Pathways to achieving low energy-poverty problems in central african nations with government effectiveness, technology, natural resources and sustainable economic growth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, K.Z.; Elenga, R.G.; Genovese, P.V. Energy–economic–environmental (3E) optimization of a hybrid system for a residential building in a developing country: A case of nigeria. Sustain. Energy Res. 2025, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenga, R.G.; Assoumou, S.S.B.B.O. Optimal sizing of a grid-connected renewable energy system for a residential application in gabon. In Proceedings of the Digital Technologies and Applicaitions, Fez, Morocco, 28–29 January 2023; pp. 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Godawa, S.; Kęsy, I. Human safety in light of the economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development—Determination of the awareness of the young generation in poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchege, J.; Okpalaoka, C. Hydroelectric production and energy consumption in nigeria: Problems and solutions. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladigbolu, J.O.; Al-Turki, Y.A.; Olatomiwa, L. Comparative study and sensitivity analysis of a standalone hybrid energy system for electrification of rural healthcare facility in nigeria. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5547–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]