Abstract

In the present study, highly transparent evaporated tungsten oxide films with improved charge storage properties were used in battery-like (b-ECDs) and hybrid electrochromic devices (h-ECDs). A Co2+/3+ redox couple was added to the electrolyte as an alternative to other redox couples that have been already used in h-ECDs. The as-prepared h-ECDs, colored homogeneously, exhibited a contrast ratio of up to 7:1 in the visible spectrum, at a cathodic voltage of −2.5 V for only 10 s, compared to 3.5:1 at a cathodic voltage of −3 V for 180 s for a b-ECD. Moreover, when the redox couple was present in the electrolyte, almost a 50% higher areal capacitance and a 55% lower charge transfer resistance at the electrochromic layer/electrolyte interface were achieved. Also, the results show that the optical performance depends strongly on the coloration procedure (potentiostatic or galvanostatic), that self-bleaching is not so intense, and especially that the energy density consumed during bleaching is reduced in the presence of the redox couple. Overall, the findings of this study highlight the benefits of using a cobalt redox electrolyte in h-ECDs, allowing a direct comparison with b-ECDs, to dynamically control incoming solar irradiation in a building, thus improving buildings’ energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

Presently, the three main sectors that consume a lot of primary energy are transport, industry, and buildings. Specifically, in the EU during 2023, buildings were responsible for 40% of total energy consumption and approximately 50% of all-natural gas use, and a large portion of this energy (≈80%) was dedicated specifically to heating, cooling, and hot water supply for the occupants [1]. Therefore, improving the energy efficiency of buildings is critical in saving energy, and an effective way to improve energy efficiency is to control significant energy losses (up to 60%) that occur through windows [2]. Energy losses occur through heat transfer via conduction, convection, and radiation, as well as through air leaks. Reducing these heat losses is possible using suitable chromogenic windows that adapt to climatic conditions.

Among the different chromogenic technologies, electrochromic windows or devices (ECWs or ECDs) offer dynamic control of visible light and solar heat passing through them by changing their appearance in response to a bias potential or current. According to numerous simulations and experimental studies, their use can lead to reduced heating and cooling needs, as well as to a reduced demand for lighting, simultaneously improving the occupants’ visual comfort. Thus, significant energy savings up to 200 kWh/m2/year can be achieved, depending on several parameters, such as the control strategy, window orientation and size, climate conditions, window-to-wall ratio, or building use [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Consequently, ECWs are considered a key technology to ensure a sustainable built environment.

There are three common types of electrochromic devices (ECDs) [8]: (a) solution-phase (sp-ECDs), (b) hybrid (h-ECDs), and (c) “battery-like” (b-ECDs). Hybrid devices combine the advantages of the other two types of ECDs, offering low operating voltages, good switching time, unlimited charge capacity, and, in some cases, bleaching under short-circuit conditions [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. More specifically, an h-ECD consists of two conductive glass substrates (FTO), the anode and the cathode. A tungsten oxide (WO3) layer and a thin platinum catalytic layer are deposited at the anode and the cathode, respectively. An electrolyte with high ionic conductivity, comprising lithium salt, a redox couple, and other additives, usually dissolved in an organic solvent, is introduced between them. During coloration, at the anode, lithium ions are intercalated into the WO3 layer, along with electrons from the external circuit to balance the charge (Equation (1)), and at the same time, the reduced species of the redox couple are oxidized (Equation (2)) at the cathode. During bleaching, the reactions are reversed. Thus, the redox couple counterbalances the redox reaction at the EC layer, offering an unlimited charge capacity.

Among the different inorganic transition metal oxides, tungsten oxide (WO3) has attracted the broadest research interest due to its unique band and crystalline structure, characterized by corner- and edge-sharing octahedra, that leaves plenty of available space for ion insertion [22]. Other advantages are high coloration efficiency, cyclic and chemical stability, fast switching speed, environmental friendliness, and the low-cost fabrication of large-area uniform thin films [23]. Finally, WO3 can be used in gas sensors, catalysis, optoelectronic devices, water splitting, etc. [24,25].

Moreover, a suitable redox electrolyte must fulfill certain specifications. For example, a high value of charge transfer resistance (RCT) at the anode and a low one at the cathode are preferable, since, due to the direct contact of the EC layer with the redox electrolyte, interfacial losses of electrons (Iloss: loss current) take place [16]. This loss mechanism leads to self-bleaching, thus limiting coloration depth and open-circuit memory. The deposition of electron barrier layers at the WO3/redox electrolyte interface is a common technique to minimize interfacial electron losses. For example, in [12], a significant reduction in loss current was achieved by using a silicon nitride (Si3N4) layer with a thickness of 80 nm, both in the case of an iodide/triiodide (I−/I3−) and a tetramethylthiourea/tetramethylformaminium disulfide dication (TMTU/TMFDS2+) redox couple. Huang et al. [26] came to the same conclusion, also using an 80 nm thick Si3N4 layer, even without the presence of a redox electrolyte. Other inorganic materials that have been used as electron barrier layers include SiO2 [12], ZnS [27,28], and Al2O3 [28]. Apparently, the low RCT at the cathode is ensured using the platinum catalytic layer. Another approach to minimizing self-bleaching is to replace the liquid electrolyte with a gel or a solid electrolyte [18].

Another parameter affecting the performance of h-ECDs is the redox potential of the electrolyte. Considering the redox potential of the electrolyte, a suitable applied bias potential for both coloration and bleaching can be chosen, as proposed by Bogati et al. in [13] for all investigated redox couples (TMTU/TMFDS2+, TEMPO/TEMPO+, I−/I3−). Also, the relative position of the redox potential of the electrolyte in respect with the electrochemical potential of the EC layer can affect also self-bleaching or even lead to self-coloration. In [16], the luminous transmittance (Tlum) in the initial state decreased from 55 to 47.2% due to self-coloration, even though the device was stored in the dark under open-circuit conditions, having an I−/I3− redox couple.

Finally, the optical properties of the redox electrolyte are crucial, since redox electrolytes usually absorb in the visible part of the spectrum, affecting the initial transparency of the h-ECDs. For example, in [16], an h-ECD with an I−/I3− redox electrolyte initially had a pale yellowish tint that became more intense after testing the device for one year. However, recently, colorless redox electrolytes were developed, based on a TMTU/TMFDS2+ [18] and a thiolate/disulfide (T−/T2) redox couple [10].

A list of performance indicators of h-ECDs with different redox couples appears in Table S1. From the available data, it appears that a cobalt-based redox electrolyte has not been used so far in h-ECDs, even though cobalt complexes present a few promising properties; for example, they absorb less visible light compared to other redox couples (e.g., I−/I3−), are non-corrosive and non-volatile, and have a tunable redox potential through the selection of different donor/acceptor substituents on the ligand. Also, cobalt complexes are already used in high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells [29,30]. Moreover, in all the above cases, the coloration of the devices took place using a potentiostatic method, by applying a bias potential of a few volts for a few seconds or minutes (Table S1), while a galvanostatic method has not been used so far, even though it is a widely used technique for evaluating the performance of charge storage devices. Therefore, in the present study, initially, the optical and electrochemical properties of evaporated tungsten oxide films were evaluated by various electrochemical techniques. Then, as-prepared WO3 films were used as the anode in b-ECDs and in h-ECDs, incorporating a cobalt-based redox couple. The optical performance of the two types of devices was evaluated, using a variety of techniques, including a potentiostatic and a galvanostatic method, to examine the effect of the coloration procedure on the device performance. Finally, the energy consumed during their operation was estimated.

Thus, we have evaluated the possible use of a cobalt-based redox electrolyte for the first time in an h-ECD, and our results show that the optical performance can be improved, also affecting the development and applicability of similar chromogenic devices, like photoelectrochromic devices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Tungsten Oxide (WO3) Thin Films

WO3 thin films were deposited on conductive glass substrates (FTO, 15 Ohm/sq) via electron beam gun evaporation at room temperature under high-vacuum conditions (P ≈ 10−5 mbar). The source material consisted of high-purity (99.99%) WO3 powder. The thickness of the as-deposited films was continuously monitored in situ during deposition via a calibrated quartz crystal sensor and subsequently validated using an XP-1 stylus profilometer (Ambios Technology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

2.2. Fabrication of Devices

2.2.1. Fabrication of Battery-like Electrochromic Devices (b-ECDs)

As-prepared WO3 films were used as the anode in b-ECDs. The cathode consisted of a bare FTO glass substrate; thus, an ion storage layer was not used in the present study, and the final configuration of the device was FTO/WO3/electrolyte/FTO. For assembling the ECD, the two electrodes (WO3/FTO and bare FTO) were positioned facing each other, slightly offset to allow space for electrical contacts. Sealing was performed using three layers of a thermoplastic material (PV5414, 0.5 mm, Dupont, Wilmington, DE, USA) at 120 °C for several minutes under pressure, which also served as a spacer. The inter-electrode space was filled by introducing the liquid electrolyte (1 M LiClO4 in propylene carbonate (PC)) through one of the two holes, drilled previously in the cathode, while allowing air to escape from the other. Finally, the holes were sealed using small glass pieces and a 50 μm thermoplastic film (Surlyn, GreatcellSolar, Queanbeyan, Australia).

2.2.2. Fabrication of Hybrid Electrochromic Devices (h-ECDs)

As-prepared WO3 films were also used as the anode in h-ECDs. The cathode consisted of a platinized FTO glass substrate, prepared by electrodeposition, as described in our previous work [16]. The final configuration of the device was FTO/WO3/redox electrolyte/Pt/FTO. Device assembly and electrolyte filling followed the same procedure as for the b-ECDs, using one layer of the PV5414 thermoplastic material. The redox electrolyte was composed of 0.055 M FK 102 Co(II) PF6, 0.5 M LiClO4, 0.5 M TBP in equal volumes of acetonitrile and 3-methoxypropionitrile.

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.3.1. Optical and Electrochemical Characterization of WO3 Thin Films

Transmittance spectra of WO3 thin films for visible and near-IR light were measured using a Lambda 650 UV/VIS spectrophotometer, supplied by Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA.

To assess the electrochemical properties of WO3 films, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) experiments occurred, using a 3-electrode configuration at room temperature (RT), where a WO3 electrode, a Ag/AgCl electrode, and a Pt wire served as the working, the reference, and the counter electrode, respectively, and a PGSTAT 204 potentiostat/galvanostat, supplied by Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland. The electrolyte used was 1 M LiClO4 in PC.

Specifically, CV measurements were carried out at varying scan rates ranging from 2 to 50 mV/s. Using these cycles, the areal capacitance (Ca) at different scan rates was calculated according to Equation (3), where v is the scan rate, ΔV is the voltage range of the potential window, and J is the current density [31].

Moreover, up to 100 successive cycles were performed to evaluate the stability of the WO3 films. Galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) measurements were employed to evaluate the energy storage performance of the electrochromic films. The procedure involved applying a constant negative and positive current density to charge and discharge the WO3 films, respectively, within a set potential window of 0–(−1) V. GCD curves performed at different current densities from 0.2 to 1 mA/cm2 [32] and the areal capacitance was calculated using Equation (4):

To gain insights into the electrochemical kinetics of WO3 films, we employed the Dunn method to quantitatively distinguish between surface capacitive processes and diffusion–controlled faradaic contributions. Therefore, CV measurements were performed within a potential window ranging from −1.0 V to +0.8 V, using scan rates of 2 mV/s, 4 mV/s, 6 mV/s, and 10 mV/s. The electrochemical reaction mechanism can be analyzed by determining the b value through the application of the Dunn power-law relationship, as expressed in Equation (5) [33]:

where ip is the peak current (mA/cm2), v is the scan rate (mV/s), and a and b are variable parameters. The b value can be extracted from the linear slope of the log i vs. log v relationship, as described by the above equation [34]. When the b value approaches 0.5, the electrochemical response is primarily governed by diffusion-controlled processes, whereas values near 1.0 indicate a dominant surface capacitive behavior [33,34].

Additionally, Equation (6) was employed to evaluate the relative contributions of surface capacitive and diffusion-controlled mechanisms, where k1v and k2v1/2 correspond to the currents associated with surface capacitive and diffusion-controlled insertion processes, respectively [33].

For analysis, this equation is expressed in the following form:

2.3.2. Optical and Electrochemical Characterization of ECDs

The coloration of the devices took place using a controlled galvanostatic process, in which incremental amounts of electric charge were applied, using the above potentiostat/galvanostat. During the process, the applied bias potential with time was recorded.

The transmittance of the devices at the different coloration stages was measured using the above spectrophotometer. Then, calculation of the luminous transmittance (Tlum) followed, using Equation (8):

with the sensitivity of the human eye f(λ) used as a weighting factor, and T(λ) being the transmittance spectrum as measured by the spectrophotometer.

The change in the optical density during coloration of the devices was calculated by Equation (9):

where Tlum,initial and Tlum,colored represent the luminous transmittance of the initial state and colored state, respectively.

The calculation of the coloration efficiency (CE) followed, using Equation (10):

where Q denotes the intercalated charge density. CE is expressed in units of cm2/C, and it is wavelength-dependent, with its value varying according to the specific wavelength at which the measurement is performed.

The open-circuit memory of the devices was evaluated by recording their transparency at 600 nm under open-circuit conditions. Therefore, an Oriel monochromator was used for analyzing the incident light and a calibrated Si photodiode for measuring the transparency of the devices.

Cyclic Voltammetry and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) were also performed to assess the electrochemical properties of the devices. Specifically, CV measurements were performed at a scan rate of 50 mV/s over a potential window of −3.0 V to +2.0 V for the b-ECDs, and −2.5 V to +2.0 V for h-ECDs. Regarding EIS measurements, the settings applied in the potentiostat software (Nova 1.10) for both devices were as follows: a bias potential of −2.0 V for 60 s, a sinusoidal signal amplitude of 0.01 V, and a scan frequency range from 0.5 Hz to 100 kHz.

3. Results and Discussion

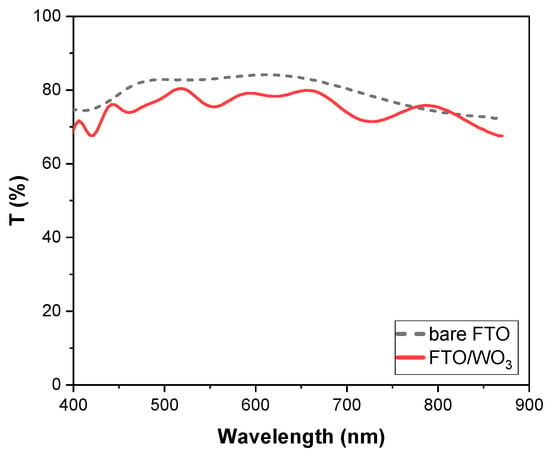

Figure 1 shows the transmittance spectra of a WO3 film deposited on an FTO glass substrate in the visible range, compared to a bare FTO glass substrate. We observe that WO3 films are highly transparent, comparable to bare FTO. More specifically, Tlum values were 77.1% and 83.2% for the WO3 film and the bare FTO glass substrate, respectively.

Figure 1.

Transmittance spectra of a WO3 thin film deposited on an FTO glass substrate (red line) and of a bare FTO glass substrate (black short-dashed line).

Thus, evaporated WO3 films were of optical quality, with no haze, and ideal for applications in smart windows. Finally, the thickness of WO3 films was 560 nm ± 10% (Figure S1) and as was examined in [35], as grown WO3 films were not entirely amorphous.

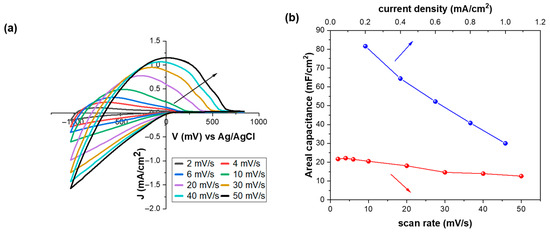

Figure 2a shows cyclic voltammograms of a WO3 film at different scan rates, ranging from 2 to 50 mV/s, keeping the voltage window constant, between −1.0 V and +0.8 V. As expected, the current density and the voltammogram area increase with increasing scan rate [36,37,38], while their shape is typical of an amorphous film [39]. More specifically, the coloration current at the most negative point on the CV plots was about 10 times higher when scan rate was 50 mV/s compared to 2 mV/s. Moreover, there is a positive shift in the voltage value where coloration begins. Simultaneously, as the scan rate increased, the de-intercalation of Li+ ions was more difficult, as depicted through the increased value of the bias potential for complete bleaching.

Figure 2.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms of a WO3 film at different scan rates (the arrow shows the increment in scan rate), (b) variation in the areal capacitance of a WO3 film as a function of the scan rate and current density, (c) GCD plots of a WO3 film at different current densities, and (d) CV curves of a WO3 film after three, sixty, and one hundred cycles. All the measurements were performed at room temperature (RT).

Cyclic voltammograms at different scan rates were also used for the calculation of the areal capacitance according to Equation (3). Figure 2b presents the areal capacitance plot as a function of the scan rate. We observe that the areal capacitance values of WO3 films decrease within the increasing scan rate [31]. This behavior is attributed to the limited penetration of electrolyte ions into the inner pore structure of the electrode at higher scan rates, imposed by time restrictions. Consequently, the loss of capacity under these conditions arises from the reduced contribution of the inner pores to charge storage due to ion transport limitations [40]. The highest areal capacitance value is almost 22.0 mF/cm2 at a scan rate of 2 mV/s, which is higher than those of previous reports (Figure S2), with comparable film thickness [31,41].

To further evaluate the electrochemical storage properties of the WO3 films, galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements at different current densities ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 mA/cm2 were performed [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. The nonlinear slopes at low current densities (Figure 2c) are due to the battery-like process (Faradaic Reaction), while the linear region at high current densities is attributed to the intercalation pseudocapacitance and surface-redox pseudocapacitance [49,50,51,52,53]. The difference between these two profiles is that the first one presents a plateau charge/discharge profile, while the second one presents a sloping charge/discharge profile [49,54]. Moreover, we observe that the charge and discharge time decreases as the current density increases, and the GCD profiles exhibit an IR drop associated with the electrode’s internal resistance, which becomes more pronounced at higher current densities, indicating that fewer active sites are available for electrochemical processes under these conditions [55].

To assess the stability of the WO3 films, 100 consecutive coloration/bleaching cycles were performed (Figure 2d). No significant changes were observed, showing stable behavior, besides a progressive reduction in the positive bias potential for complete bleaching of the WO3 film, especially after the first 60 cycles (from +780 mV to +530 mV). This ‘training’ phenomenon results from the improved wetting of the film from the electrolyte, as the number of cycles increases. As a result, more entry/exit points for Li+ are created, making their extraction easier.

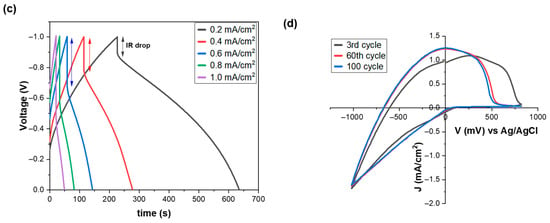

The final step was to perform the kinetic analysis of WO3 film, for the separation of the surface capacitive and diffusion-controlled faradaic processes (Figure 3). For the analysis, we used the above cycle voltammograms at scan rates of 2 mV/s, 4 mV/s, 6 mV/s, and 10 mV/s. Figure 3a shows the b value of WO3 film, which was calculated from Equation (5). The b value was 0.94, indicating that the surface capacitive process dominates.

Figure 3.

(a) Plot of log(j) vs. log(v) (scan rate) for determining the b value of a WO3 film, (b) CV plot at a scan rate of 10 mV/s, indicating the capacitive contribution to the total current, as highlighted by the colored region, and (c) relative contributions of surface capacitive and diffusion-controlled processes. All the measurements were performed at room temperature (RT).

According to Equations (6) and (7), we obtained k1 and k2 values at each potential, and the purely capacitive contribution to the total current is marked by the shaded cyan color region, at a scan rate of 10 mV/s (Figure 3b). Moreover, as shown in Figure 3c, the amount of the surface capacitive process is 79.5% of the total capacitance of the WO3 film, while the diffusion-controlled faradaic process dominates at the upper and lower limits of the potential window. Therefore, fast electron transfer kinetics are expected, due to the fast redox reactions (pseudocapacitance) [33]. The dominance of surface capacitive process over the diffusion-controlled insertion process is usually associated with an enlarged surface-reaction area [33,56].

The above results agree with GCD measurements, in which WO3 films present both battery-like process at low current densities and intercalation pseudocapacitance/surface-redox pseudocapacitance processes at high current densities.

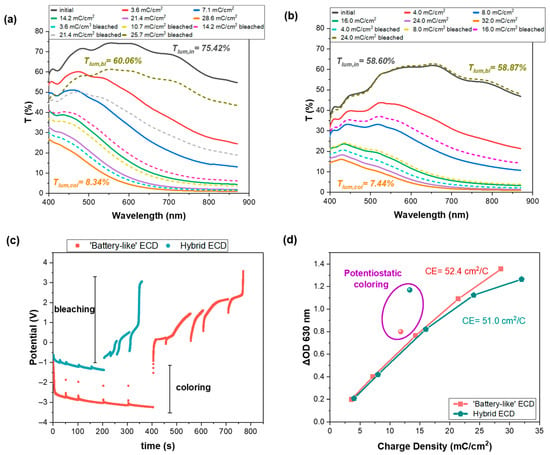

As-prepared WO3 films were used for the preparation of b-ECDs and h-ECDs. Figure 4a and Figure 4b show the transmittance spectra at diverse coloration steps of a typical b-ECD and an h-ECD, respectively. The cumulative intercalated and de-intercalated charge density appears in the legend of the graphs. We observe a high initial transparency (Tlum = 75.42%) in the visible part of the spectrum for the b-ECD, while the corresponding transparency for the h-ECD is at lower value (Tlum = 58.60%). This is attributed to the absorption by the cobalt redox electrolyte in the case of h-ECDs, resulting in a pale yellowish tint in the devices [57]. Thus, additional efforts are required to optimize the initial transparency of the h-ECDs. To this end, the concentration of the redox electrolyte, the distance between the two electrodes, or even the optical properties of the solvent must be carefully adjusted.

Figure 4.

Transmittance spectra of a b-ECD (a) and an h-ECD (b) at different coloration and bleaching states, (c) variation in the bias potential with respect to time for both devices during operation, and (d) variation in the optical density (ΔOD) as a function of the charge density at 630 nm for both devices.

Moreover, even from the first coloration stages for both devices, a distinct color change is evident. Both devices reached almost the same coloration depth (8.34% and 7.44%), even though the total charge density in the case of an h-ECD was ~12% higher than in the case of the b-ECD. This phenomenon is usual for hybrid ECDs due to the direct contact of the EC layer with the redox electrolyte, which leads to the so-called “loss-current” (Iloss) or equally self-bleaching. Thus, the total charge density (Qtotal) corresponds to the sum of the charge density associated with cobalt reduction at the anode (Qloss) and the charge stored in the WO3 film (Qstored) [16].

However, the bias potentials were −3.23 V and −1.38 V (Figure 4c) for the b-ECD and the h-ECD at the end of the coloration stage, respectively, showing a reduced operating voltage and thus a lower energy consumption in the case of the h-ECD.

Regarding the bleaching process, the de-intercalated charge density was 25.7 mC/cm2 for the b-ECD, without the device reaching its initial transparency. The reason for this irreversible behavior was that the bias potential surpassed the value of +3.6 V (Figure 4c), which we had set as a cut-off voltage in the potentiostat. Probably, at a higher bias potential, complete bleaching would be possible. On the other hand, the h-ECD was fully reversible, with the bias potential reaching the value of +3.0 V at the end of the bleaching stage (Figure 4c). However, the de-intercalated charge density was only 24 mC/cm2, compared to 32 mC/cm2, for complete coloration of the device, due to the above-mentioned contribution of Qloss to the total charge density (Qtotal), which overestimates the latter.

Finally, the coloration efficiency was calculated by the slope of the linear part in the graph of the optical density modulation with respect to the intercalated charge density at 630 nm. A slightly higher coloration efficiency was calculated in the case of a b-ECD compared to an h-ECD (Figure 4d). A higher CE value indicates that a significant optical contrast can be achieved with minimal charge consumption, a feature directly linked to faster switching response. However, the difference is small, demonstrating that h-ECDs with a cobalt redox electrolyte show strong potential as promising candidates for smart windows.

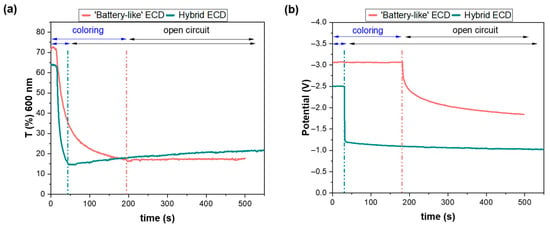

Another important parameter worth examining is self-bleaching, due to loss reactions at the WO3/electrolyte interface. Therefore, initially coloration of the b-ECD and the h-ECD took place, applying −3 V for 3 min and −2.5 V for 30 s, respectively, and then both devices remained under open-circuit conditions. The transmittance at 600 nm and the potential across the terminals of the devices were recorded (Figure 5). No significant changes were observed in the transparency of a b-ECD after 5 min in open-circuit conditions. However, a notable decrease in the potential across the device terminals was observed, with the value decreasing from −3 to −1.8 V (Figure 5b). Although self-bleaching of the device did not occur, self-discharging was important, indicating that the device cannot be considered as a high-performance EC battery. Nevertheless, it is suitable for smart window applications due to its pronounced optical modulation, particularly in the infrared region of the spectrum. This reduction in potential has not been discussed in the literature before, and further investigation is required to fully understand its underlying cause.

Figure 5.

(a) Variation in the transmittance at 600 nm and (b) in the potential difference across the terminals of the b-ECD and the h-ECD, during coloration and in open-circuit conditions.

On the other hand, the h-ECD appears to have optical losses in open-circuit conditions, as the transmittance at 600 nm increased from 14 to 21% (Figure 5a), due to self-bleaching. The presence of the redox couple in the electrolyte is expected to strengthen the self-bleaching mechanism and, to address this, several methods have been proposed in the relevant literature [9,10,13,14,21,58]. Also, a significant decrease in the potential across the device terminals from −2.5 to −1.0 V after 5 min under open-circuit conditions was observed, as in the case of the b-ECD (Figure 5b).

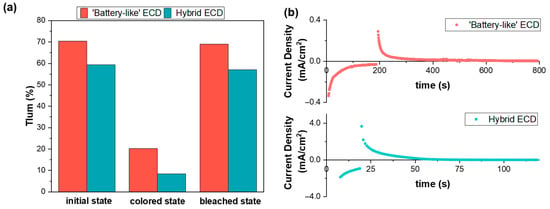

In addition to the galvanostatic method for evaluating the optical response of the devices, we also employed a potentiostatic method, applying a constant bias potential for coloration and bleaching, as shown in Table 1. We observed lower operating voltages and switching times and improved optical performance in the case of the h-ECD (Table 1, Figure 6a). For example, the b-ECD exhibited ΔOD = 0.8 at 630 nm and Tlum = 20.23% at the end of the coloration process, while the corresponding values for the h-ECD were 1.2 and 8.42%, respectively, exhibited in a shorter coloration time (Table 1, Figure 6a). Both devices exhibited also an improved ΔOD compared to the galvanostatic method (Figure 4d), due to differences in the applied bias potential during coloration. Moreover, initially, the total current passing through the h-ECD during coloration was almost 4 times higher compared to b-ECD (Figure 6b), due to the contribution of the loss current, resulting in a total charge density of 13.3 mC/cm2, compared to 11.8 mC/cm2 for the b-ECD (Table 1). As a result, coloration of the h-ECD was less energy-consuming than that of the b-ECD, as estimated by Equation (S1). However, a relatively high bias potential for coloration was applied, even though it was for a short period of time and before saturation was reached (Figure 6b), due to the more positive redox potential of the Co2+/3+, compared with other alternative redox couples [13].

Table 1.

Characteristic parameters during the potentiostatic coloration.

Figure 6.

(a) Luminous transmittance values for the b-ECD and the h-ECD in initial, colored, and bleached states and (b) variation in total current density during coloration and bleaching.

Additionally, both devices were optically reversible, even though bleaching was more facile in the presence of the cobalt redox couple, compared not only to b-ECDs but also to other redox couples used in the relevant literature (Table S1). For example, in [13] and in [18], devices were bleached at +0.6 V and at +1.5 V for 5 min, respectively. Considerable differences were also observed in current density values and the resulting charge densities during bleaching between the h-ECD and the b-ECD (Table 1, Figure 6b). More importantly, the required energy density for bleaching in the case of the b-ECD was twice as high compared to the h-ECD, proving once more the beneficial role of the redox couple (Table 1).

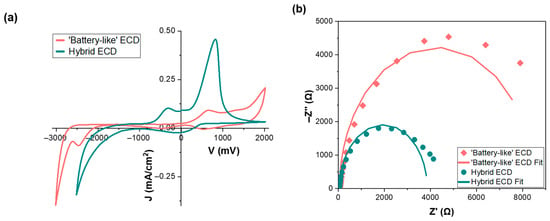

To assess the electrochemical properties of the devices, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) experiments were performed (Figure 7). The voltage window ranged from −3.0 to +2.0 V for the b-ECD and from −2.5 to +2.0 V for the h-ECD. A significant difference is observed between the areas of two voltammograms, which is proportional to the total charge density exchanged at the EC layer/electrolyte interface [59]. More specifically, the total charge densities were 8.84 and 12.08 mC/cm2 for the b-ECD and the h-ECD, respectively. As a result, the areal capacitance of b-ECD was 0.88 mF/cm2, while the h-ECD exhibited an areal capacitance of 1.34 mF/cm2. This further confirms the consistency of our results with the attainable coloration depth of the devices (Figure 6).

Figure 7.

(a) CV plots for the a b-ECD and an h-ECD and (b) Nyquist plots with fitted curves derived from the Randles equivalent circuit model.

Moreover, as shown in Figure 7a, the voltammogram of the b-ECD exhibits two peaks at −2477 mV and +640 mV, corresponding to the reduction and the oxidation processes of the WO3 film, according to Equation (1). As for the h-ECD, we observe two oxidations’ peaks (at −340 mV and 820 mV), which correspond to the oxidation of the cobalt species, as verified in Figure S4, and the Li+ ion de-intercalation (oxidation) from the WO3 film, respectively, while coloration begins at a lower bias potential resulting in lower operating voltages and improved coloration kinetics, as observed with both the galvanostatic and the potentiostatic method. Therefore, it is evident that the redox couple contributes to the overall charge storage mechanism and facilitates both the insertion and extraction of Li+, in combination with the platinized counter electrode.

Finally, EIS measurements were recorded for both devices (Figure 7b). Figure 7b shows the Nyquist plots of the b-ECD and the h-ECD and their fitting curves based on the Randles equivalent circuit model (Figure S5), implemented in the NOVA software [60]. More specifically, the Randles model consists of three elements: Rs, the series resistance dominant at high frequencies; Rct, the charge transfer resistance observed at intermediate frequencies; and Cdl, the capacitor representing the double-layer capacitance at the electrode/electrolyte interface, which stores charge at the electrode surface [61]. We observe a semicircle in the intermediate frequency region for both devices, with the only difference being their diameter, which corresponds to the charge transfer resistance. As a result, the charge transfer resistances were 8.45 and 3.81 kΩ for the b-ECD and the h-ECD, respectively, indicating that the presence of the redox couple facilitates the charge transfer at the WO3/electrolyte interface [28,61]. This agrees with the improved optical losses in open-circuit conditions, due to self-bleaching. Finally, no differences were observed between the two devices regarding Rs values, showing that the presence of the redox couple in the electrolyte has no effect on the ohmic resistance of the devices.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have fabricated WO3 thin films by e-gun evaporation. As-prepared films were highly transparent in the visible range, with an improved areal capacitance, as verified both by cyclic voltammetry and galvanostatic charge–discharge measurements, showing a pseudocapacitive behavior, where the surface-controlled processes were dominant over the diffusion-controlled processes. A training period was observed by performing consecutive cycles, during which extraction of Li+ became easier.

Then, as-prepared WO3 films were used as the EC layer in both b-ECDs and h-ECDs, using for the first time a Co2+/3+ redox couple. Both types of devices exhibited reversible behavior and an optical performance depending on the coloration procedure. More specifically, when we used a galvanostatic process, both devices exhibited comparable contrast ratios and coloration efficiencies. However, h-ECDs exhibited lower operating voltages and improved switching kinetics, compared to b-ECDs. On the other hand, the luminous transmittance of the h-ECD was switched from 59.45% to 8.42%, upon applying a cathodic voltage of 2.5 V for 10 s. Similarly, Tlum of the b-ECD was switched from 70.48% to 20.23% upon applying a cathodic voltage of 3 V for 3 min. The differences observed during the bleaching of the devices were more pronounced, and the areal capacitance was improved, indicating the beneficial effects of adding the redox couple in the electrolyte. Facile reaction kinetics at the platinized counter electrode facilitates insertion/extraction of Li+ from the WO3 layer; thus, the operation of the devices was less energy-consuming. However, an initial yellowish tint cannot be completely avoided, due to the absorption by the redox electrolyte, and the reduced charge transfer resistance at the WO3/electrolyte interface promotes self-bleaching.

To sum up, the introduction of the Co2+/3+ redox couple improves the optical performance and the charge storage capacity of the devices. Also, the coloration/bleaching procedure plays an important role in estimating the optical performance of the h-ECDs, with the galvanostatic procedure showing more reliable results, since optical modulation is voltage- and time-dependent. Thus, we need to be careful when reporting the performance of h-ECDs. Finally, the concentration of redox species must be optimized to fully exploit the benefits of h-ECDs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010068/s1, Figure S1: Thickness profile of a typical WO3 thin film; Figure S2: Areal capacitance of WO3 films, as calculated by performing Cyclic Voltammetry experiments at different scan rates [31,41]. * Film thickness was 2 μm. In all other cases, film thickness was about 500 nm; Figure S3: Areal capacitance values of WO3 films, under the galvanostatic charge–discharge method [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]; Figure S4: CV plot of a device with an electrolyte containing only cobalt species (LiClO4-free), used for peak assignment, especially during bleaching. Since no Li+ ions were present, the peak at ≈ −200 mV was assigned to the oxidation of cobalt species; Figure S5: Randles equivalent circuit model for the (a) ‘battery-like’ and (b) hybrid ECDs; Table S1: Redox electrolyte-dependent performance in h-ECDs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.; Investigation, E.M.; Formal analysis, G.S. and E.M.; Visualization, E.M.; Writing—original draft, G.S. and E.M.; Writing—review and editing, G.S. and E.M.; Supervision, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge financial support from the project ‘FENESTRAE’ co-funded by the European Union through the Interreg IPA ADRION programme. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of University of Patras, Department of Physics and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union and/or IPA ADRION programme authorities.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their large volume.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-performance-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Detsi, M.; Atsonios, I.; Mandilaras, I.; Founti, M. Effect of smart glazing with electrochromic and thermochromic layers on building’s energy efficiency and cost. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, R.; Jelle, B.P.; Gustavsen, A. Properties, requirements and possibilities of smart windows for dynamic daylight and solar energy control in buildings: A state-of-the-art review. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2010, 94, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.L.; Lee, E.S.; Ward, G. Lighting energy savings potential of split-pane electrochromic windows controlled for daylighting with visual comfort. Energy Build. 2013, 61, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavale, A.; Ayr, U.; Fiorito, F.; Martellotta, F. Smart Electrochromic Windows to Enhance Building Energy Efficiency and Visual Comfort. Energies 2020, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detsi, M.; Manolitsis, A.; Atsonios, I.; Mandilaras, I.; Founti, M. Energy Savings in an Office Building with High WWR Using Glazing Systems Combining Thermochromic and Electrochromic Layers. Energies 2020, 13, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.R.; Hong, J.; Choi, E.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, C.; Moon, J.W. Improvement in Energy Performance of Building Envelope Incorporating Electrochromic Windows (ECWs). Energies 2019, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklaus, L.; Schott, M.; Posset, U.; Giffin, G.A. Redox Electrolytes for Hybrid Type II Electrochromic Devices with Fe−MEPE or Ni1−xO as Electrode Materials. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 3274–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, H.; Moon, H.C.; Kim, S.H. Low-voltage, simple WO3-based electrochromic devices by directly incorporating an anodic species into the electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 10887–10892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannuzzi, R.; Prontera, C.T.; Primiceri, V.; Capodilupo, A.L.; Pugliese, M.; Mariano, F.; Maggiore, A.; Gigli, G.; Maiorano, V. Hybrid electrochromic device with transparent electrolyte. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 257, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georg, A.; Georg, A. Electrochromic device with a redox electrolyte. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2009, 93, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogati, S.; Georg, A.; Graf, W. Sputtered Si3N4 and SiO2 electron barrier layer between a redox electrolyte and the WO3 film in electrochromic devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 159, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogati, S.; Georg, A.; Jerg, C.; Graf, W. Tetramethylthiourea (TMTU) as an alternative redox mediator for electrochromic devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 157, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolović, M.; Hajzeri, M.; Tramšek, M.; Orel, B.; Surca, A.K. In situ Raman and UV–visible study of hybrid electrochromic devices with bis end-capped designed trialkoxysilyl-functionalized ionic liquid based electrolytes. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 220, 110863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Han, Z.; Cho, C.; Kim, E. Charge-Balancing Redox Mediators for High Color Contrast Electrochromism on Polyoxometalates. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 2000326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrrokostas, G.; Tsamoglou, S.; Leftheriotis, G. Limitations Imposed Using an Iodide/Triiodide Redox Couple in Solar-Powered Electrochromic Devices. Energies 2023, 16, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, K.; Xie, H.; Xue, B.; Zheng, J.; Xu, C. Robust non-complementary electrochromic device based on WO3 film and CoS catalytic counter electrode with TMTU/TMFDS2+ redox couple. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, M.; Krašovec, U.O. Solid electrolyte containing a colorless redox couple for electrochromic device. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 196, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, H.; Khalifa, M.A.; Zheng, J.; Xu, C. Long-Term Stable Complementary Electrochromic Device Based on WO3 Working Electrode and NiO-Pt Counter Electrode. Membranes 2023, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Li, X.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, H.C. Tetrathiafulvalene: Effective organic anodic materials for WO3-based electrochromic devices. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19450–19456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Huang, B.; Xu, Y.; Yang, K.; Li, Y.; Mu, Y.; Du, L.; Yun, S.; Kang, L. A Low Driving-Voltage Hybrid-Electrolyte Electrochromic Window with Only Ferreous Redox Couples. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, C.G. Electrochromics for smart windows: Oxide-based thin films and devices. Thin Solid Films 2014, 564, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Zhou, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yu, S.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cao, X.; Wu, X.; Gao, X.; et al. Research Progress on Electrochromic Properties of WO3 Thin Films. Coatings 2025, 15, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, O.M.; Toledo, R.P.; da Silva Barros, H.E.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Nunes, R.S.; Joshi, N.; Berengue, O.M. Advances and Challenges in WO3 Nanostructures’ Synthesis. Processes 2024, 12, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sang, D.; Zou, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C. A Review on the Properties and Applications of WO3 Nanostructure−Based Optical and Electronic Devices. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Dong, G.; Xiao, Y.; Diao, X. Electrochemical studies of silicon nitride electron blocking layer for all-solid-state inorganic electrochromic device. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 252, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokouzis, A.; Theodosiou, K.; Leftheriotis, G. Assessment of the long-term performance of partly covered photoelectrochromic devices under insolation and in storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 182, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokouzis, A.; Zhang, J.; Skarlatos, D.; Leftheriotis, G. Electrochemical evaluation of barrier layers for photoelectrochromic devices. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 464, 142941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F.; Galliano, S.; Gerbaldi, C.; Viscardi, G. Cobalt-Based Electrolytes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Recent Advances towards Stable Devices. Energies 2016, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giribabu, L.; Bolligarla, R.; Panigrahi, M. Recent Advances of Cobalt (II/III) Redox Couples for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Applications. Chem. Rec. 2015, 15, 760–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animasahun, L.O.; Taleatu, B.A.; Adewinbi, S.A.; Busari, R.A.; Omotoso, E.; Adewumi, O.E.; Fasasi, A.Y. Rapid synthesis and characterizations of defect-enhanced WO3-δ thin film electrode for effective energy storage application in asymmetric supercapacitor devices. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 167, 112378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, F.; Davis, M.A.; Andreas, H.A. Charge redistribution and electrode history impact galvanostatic charging/discharging and associated figures of merit. J. Power Sources 2020, 446, 227354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, M.; Diao, X.; Lee, C.S. Surface morphology engineering of WO3 films for increasing Li ion insertion area in electrochromic supercapacitors (ECSCs). Electrochim. Acta 2023, 472, 143394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Sun, P.; Du, L.; Liang, Z.; Xie, W.; Cai, X.; Huang, L.; Tan, S.; Mai, W. Quantitative Analysis of Charge Storage Process of Tungsten Oxide that Combines Pseudocapacitive and Electrochromic Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 16483–16489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrrokostas, G.; Leftheriotis, G.; Yianoulis, P. Performance and stability of ‘partly covered’ photoelectrochromic devices for energy saving and power production. Solid State Ion. 2015, 277, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftheriotis, G.; Papaefthimiou, S.; Yianoulis, P. Dependence of the estimated diffusion coefficient of LixWO3 films on the scan rate of cyclic voltammetry experiments. Solid State Ion. 2007, 178, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Deepa, M.; Singh, S.; Kishore, R.; Agnihotry, S.A. Microstructural and electrochromic characteristics of electrodeposited and annealed WO3 films. Solid State Ion. 2005, 176, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, M.; Saxena, T.K.; Singh, D.P.; Sood, K.N.; Agnihotry, S.A. Spin coated versus dip coated electrochromic tungsten oxide films: Structure, morphology, optical and electrochemical properties. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 1974–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, C.G. Handbook of Inorganic Electrochromic Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, B.; Dubal, D.P.; Gómez-Romero, P.; Kale, B.B.; Sankapal, B.R. V2O5 encapsulated MWCNTs in 2D surface architecture: Complete solid-state bendable highly stabilized energy efficient supercapacitor device. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.-C.; Lin, P.-H.; Hsu, C.-E.; Jian, W.-B.; Lin, Y.-L.; Chen, J.-T.; Banerjee, S.; Chu, C.-W.; Khedulkar, A.P.; Doong, R.-A.; et al. Boosting areal capacitance in WO3-based supercapacitor materials by stacking nanoporous composite films. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, X.; Bi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Gao, X. Dual-functional electrochromic and energy-storage electrodes based on tungsten trioxide nanostructures. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2018, 22, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Bi, Z.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Guo, X.; Gao, X.; Li, X. Electrodeposited Mo-doped WO3 film with large optical modulation and high areal capacitance toward electrochromic energy-storage applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 459, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Li, X.; He, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Gao, X. Integrated electrochromism and energy storage applications based on tungsten trioxide monohydrate nanosheets by novel one-step low temperature synthesis. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 183, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, X.; Lin, G.; Peng, Y.; Chao, J.; Yi, L.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Liao, W. Structure engineering in hexagonal tungsten trioxide/oriented titanium dioxide nanorods arrays with high performances for multi-color electrochromic energy storage device applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, G.; Tang, T.; Zeng, J.; Sagar, R.U.R.; Qi, X.; Liang, T. Construction of doped-rare earth (Ce, Eu, Sm, Gd) WO3 porous nanofilm for superior electrochromic and energy storage windows. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 412, 140099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, G.; Tang, T.; Sagar, R.U.R.; Qi, X. Growth of a high-performance WO3 nanofilm directly on a polydopamine-modified ITO electrode for electrochromism and power storage applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 573, 151603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liao, P.; Yuan, X.; Jia, J.; Lan, C.; Li, C. Co-sputtering construction of Gd-doped WO3 nano-stalagmites film for bi-funcional electrochromic and energy storage applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.P.; Shao, Z. Intercalation pseudocapacitance in electrochemical energy storage: Recent advances in fundamental understanding and materials development. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deebansok, S.; Deng, J.; Le Calvez, E.; Zhu, Y.; Crosnier, O.; Brousse, T.; Fontaine, O. Capacitive tendency concept alongside supervised machine-learning toward classifying electrochemical behavior of battery and pseudocapacitor materials. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, T.; He, Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, M.; Luo, Z.; Liu, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhong, X.; Du, K.; et al. All-solid-state electrochromic Li-ion hybrid supercapacitors for intelligent and wide-temperature energy storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, F.; Anwar, A.W.; Majeed, A.; Ahmad, M.A.; Ilyas, U.; Ahmad, F. High performance and remarkable cyclic stability of a nanostructured RGO–CNT-WO3 supercapacitor electrode. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 11293–11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodankar, N.R.; Pham, H.D.; Nanjundan, A.K.; Fernando, J.F.S.; Jayaramulu, K.; Golberg, D.; Han, Y.; Dubal, D.P. True Meaning of Pseudocapacitors and Their Performance Metrics: Asymmetric versus Hybrid Supercapacitors. Small 2020, 16, 2002806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-W.; Yun, T.Y.; You, S.-H.; Tang, X.; Lee, J.; Seo, Y.; Kim, Y.-T.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, H.C.; Kim, J.K. Extremely fast electrochromic supercapacitors based on mesoporous WO3 prepared by an evaporation-induced self-assembly. NPG Asia Mater. 2020, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, G.; Scuderi, M.; Escobar, G.P.; Mirabella, S.; Bruno, E. Engineering of Nanostructured WO3 Powders for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannuzzi, R.; Scarfiello, R.; Sibillano, T.; Nobile, C.; Grillo, V.; Giannini, C.; Cozzoli, P.D.; Manca, M. From capacitance-controlled to diffusion-controlled electrochromism in one-dimensional shape-tailored tungsten oxide nanocrystals. Nano Energy 2017, 41, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokouzis, A.; Bella, F.; Theodosiou, K.; Gerbaldi, C.; Leftheriotis, G. Photoelectrochromic devices with cobalt redox electrolytes. Mater. Today Energy 2020, 15, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Xu, F.; Shen, K.; Zheng, J.; Xu, C. Electrocatalytic PProDOT–Me2 counter electrode for a Br−/Br3− redox couple in a WO3-based electrochromic device. Electrochem. Commun. 2020, 111, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftheriotis, G.; Papaefthimiou, S.; Yianoulis, P.; Siokou, A.; Kefalas, D. Structural and electrochemical properties of opaque sol-gel deposited WO3 layers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 218, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckmann, F.-W.; Bintz, S.; Groninger, M.L.; Birke, K.P. Alkaline Electrolysis with Overpotential-Reducing Current Profiles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, F456–F462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondalkar, V.V.; Mali, S.S.; Kharade, R.R.; Khot, K.V.; Patil, P.B.; Mane, R.M.; Choudhury, S.; Patil, P.S.; Hong, C.K.; Kim, J.H.; et al. High performing smart electrochromic device based on honeycomb nanostructured h-WO3 thin films: Hydrothermal assisted synthesis. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2788–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.