Abstract

The global transition towards a clean energy system underscores the critical role of Green Electricity Certificates (GECs), yet their effectiveness is often hampered by an inability to credibly trace environmental attributes from generation to consumption. This study provides a systematic review of technological pathways and policy implications for enhancing GEC markets through real-time electricity-carbon traceability, using China’s large-scale and rapidly evolving market as a central case. Through comparative international analysis and examination of China’s market data (2023–2025), we identified a severe oversupply of certificates and a reliance on policy-driven demand as core structural dilemmas. The aim of this study was to clarify how real-time traceability can fundamentally enhance the credibility, temporal precision, and policy applicability of GEC mechanisms, particularly under China’s rapid institutional reforms. The findings indicate that a fundamental transition towards hourly granularity in certificate issuance and matching is critical to enhance credibility, prevent double-counting, and enable high-value applications like 24/7 clean energy matching. Furthermore, deep integration between the GEC market and the carbon emission trading (CET) scheme is necessary to expand value propositions. We conclude that the synergistic integration of market design (mandatory quotas), cross-market coupling (GEC-carbon market linkage), and robust digital traceability represents the most effective pathway to transform GECs into a credible instrument for driving additional renewable energy consumption and supporting global carbon mitigation goals.

1. Introduction

The global transition towards a clean and low-carbon energy system is an imperative undertaking for achieving climate goals. Within this transition, the power sector, accounting for over 40% of energy-related carbon emissions [1], represents a critical battleground. Green Electricity Certificate (GEC) mechanisms have emerged as pivotal market-based instruments designed to promote renewable energy (RE) consumption and facilitate this structural shift [2]. By decoupling and certifying the environmental attributes of electricity from its physical delivery, GECs aim to create a transparent market that values clean energy generation. However, many GEC markets worldwide, including the pioneering system in China, face a fundamental credibility crisis. This challenge primarily stems from an inability to accurately and reliably trace the environmental attributes of electricity from generation to consumption, which severely hampers the integration of GECs into high-stakes applications such as corporate carbon footprint accounting and international Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks. The primary objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of existing policy, market, and technological developments, and to assess how real-time electricity–carbon traceability can serve as a foundational solution to the credibility and additionality challenges facing GEC systems.

China’s power sector offers a salient and critical context for examining these challenges and opportunities. As the country with the largest installed capacity of renewable energy globally, China’s experience provides invaluable insights. While the share of renewable energy installation has reached a remarkable 56% [3,4,5], the intermittent nature of wind and solar power poses severe real-time absorption challenges for the grid [6,7,8]. China’s GEC market, officially launched in 2017 as a voluntary pilot, has evolved into a comprehensive management framework covering issuance, trading, and cancellation. A pivotal shift occurred with the transition to full-volume issuance for all renewable projects, dramatically expanding the market scale. Despite this progressive institutional development, a core structural contradiction persists: a substantial and growing gap between the volume of certificates issued and those actively traded. This disparity indicates that market demand remains primarily policy-driven and sporadic, rather than being fueled by stable, endogenous, and value-based demand, which is essential for long-term sustainability.

The existing academic literature on GEC markets has formed a relatively complete system, primarily focusing on three dimensions: institutional design and economic assessment [9,10,11], market linkages (e.g., with carbon markets) [12,13,14,15,16], and enabling technologies like blockchain for traceability [17,18,19]. However, evaluations of policy effectiveness show significant divergence. Model-based studies affirm the theoretical value of GECs in promoting a clean energy transition [20,21], whereas empirical analyses, often relying on early stage transaction data, highlight market inefficiencies and regional imbalances [22,23,24]. A critical synthesis reveals that these conflicting conclusions often stem from methodological and data limitations. Theoretical models frequently overlook the critical constraint that traceability defects impose on GEC credibility, while empirical studies, reliant on outdated data, fail to capture the dynamic evolution of the post-full-volume issuance market. More importantly, a significant research gap exists concerning the potential of real-time traceability technology to address the dual constraints of low credibility and inadequate application scenarios, particularly in the context of developing smart grids with active source–load interactions.

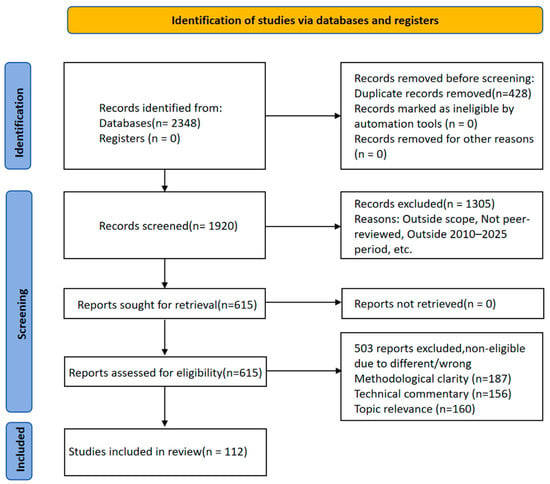

To ensure a methodologically rigorous and transparent literature review, this study employed a systematic identification and screening process. The initial search was conducted across major academic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, CNKI) using a combination of keywords related to green electricity certificates, market mechanisms, and credibility (e.g., “green electricity certificate”, “renewable energy certificate”, “greenwashing”, “electricity–carbon traceability”). The systematic screening and selection process, which followed the PRISMA guidelines, is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature identification, screening, and inclusion process.

The process began with 2348 identified records. After removing duplicates, 1920 records underwent title and abstract screening, primarily excluding those outside the topical scope, not peer-reviewed, or published outside the primary time window of 2010–2025. Subsequently, 615 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with a focus on methodological clarity and direct relevance to the core themes of GEC mechanisms, credibility, and market-technology integration. This led to the exclusion of 503 reports, primarily for being technical commentaries, lacking methodological clarity, or lacking sufficient topic relevance. The final corpus for in-depth analysis comprised 112 studies. A particular emphasis was placed on literature from 2023–2025, as this period represents the most data-rich and coherent phase following China’s shift to full-volume certificate issuance, a phase marked by key regulatory updates and the rapid deployment of digital traceability technologies.

Building upon this foundation, this paper provides a systematic review of the technological pathways and policy implications of real-time electricity-carbon traceability systems. The Chinese context serves as a central case study due to its massive market scale, rapid development, and pioneering policy experiments. The insights generated are intended to offer valuable lessons for the evolution of GEC systems globally. Ultimately, this review aims to reframe the discourse around GECs from one centered on administrative compliance to one focused on market-driven value creation enabled by technological precision. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review, synthesized from the screened corpus. Section 3 offers a comparative analysis of international GEC mechanisms. Section 4 analyzes the structural dilemmas and scenarios within China’s GEC market. Section 5 delves into the architecture and functions of real-time traceability technology. Section 6 proposes an integrated framework and discusses policy implications. Finally, Section 7 concludes and outlines future research directions.

2. Literature Review

The existing literature on policies supporting RE deployment is vast and methodologically diverse, encompassing economic analyses, evaluations of investment determinants, and sophisticated market modeling. A significant portion of this research focuses on key policy instruments such as Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) and, more centrally to this study, GEC markets. The integration of these markets with carbon pricing mechanisms and digital traceability technologies constitutes a critical and rapidly evolving frontier. Guided by the systematic screening process outlined in the Introduction (see Figure 1), this review synthesizes the key research streams pertinent to GECs. It is structured around four interconnected thematic areas: (1) the institutional design and evolution of GEC mechanisms, (2) their market integration, particularly with carbon markets, (3) technological solutions for enhancing temporal and spatial traceability, and (4) the persistent challenge of ensuring credibility and mitigating greenwashing risks. This structured synthesis ensures alignment with the study’s analytical focus and establishes a comprehensive foundation for analyzing the synergies and challenges within interconnected electricity–carbon–GEC systems.

A central theme in the literature is the economic viability and investment attractiveness of RE systems under various policy frameworks. Complementing micro-level analyses, broad reviews of empirical studies, such as Polzin et al. [25], identified that reduced risk and higher certainty are paramount for attracting private investment, with instruments like Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs) and RPS historically proving more effective than early stage green certificate mechanisms. This focus on investment is further supported by macro-level studies mapping global capital flows, which found FiTs to be highly effective for attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) [26].

Empirical evidence from China further corroborates the role of market-based instruments. Liu et al. [27] demonstrated that under the coexistence of FiT and RPS mechanisms, the pricing of GECs is critically influenced by government subsidies, and renewable energy generators are motivated to participate in the GEC market only when the certificate price approaches or exceeds the subsidy level. This indicates that GECs can serve as an effective market signal to guide capital allocation, particularly when the economic incentives are appropriately aligned.

The literature increasingly acknowledges the complex interactions between different policy instruments and market mechanisms. Wang et al. [28] combined evolutionary game theory with system dynamics modeling to analyze the strategic behaviors of power generators, users, and regulators in China’s green electricity market. Their results highlight that the implementation of RPS effectively promotes green electricity trading, especially under high premium conditions, and that the long-term stability of market participation depends on factors such as environmental perceptions and dynamic incentive designs.

Furthermore, studies such as Shang et al. [29] examined the coupling relationship between electricity and carbon markets, illustrating how carbon pricing influences power generation costs and dispatch decisions, thereby indirectly shaping the profitability and attractiveness of RE investments. This multi-market interplay is essential for modern policy design, as also emphasized in the system dynamics analysis by Yang et al. [30], which revealed that market mechanisms like RPS adjust generator profits and stimulate RE generation, thereby optimizing the overall power structure. Their findings further indicate that carbon emission trading (CET) and China Certified Emission Reduction (CCER) prices often move inversely to GEC prices, reflecting the sophisticated price dynamics within an integrated policy environment.

The evolution of policy mechanisms from fixed subsidies towards market-based integration represents a critical area of scholarship. Lam et al. [31] explored the transition as technology costs decline, arguing that grid parity reduces the need for direct government intervention and necessitates smarter market designs. The Chinese context provides a salient example, where the introduction of the GEC market was followed by a mandatory RPS. Research has begun to disentangle their effects, with Huang et al. [32] finding that while GECs spurred investment, it was the RPS that significantly drove consumption, underscoring the “additionality” principle—a GEC market oversupplied with certificates lacks the scarcity needed to create “additional” consumption incentives. The synergy between a mandatory quota (RPS) and a flexible market instrument (GEC) is thus critical.

The design of these integrated markets is a key focus. Study [33] proposed a collaborative optimization framework with Distributed Resource Aggregators (DRAs) as the main body, innovatively coupling CET with electric vehicle carbon quotas and RPS with GEC transactions. Their work constructs a connection path between these markets to realize the integrated utilization of environmental value, demonstrating a significant reduction in total costs under the proposed CET-RPS coupling mechanism.

Similarly, Study [34] systematically analyzed the main players in the electricity-CET-GEC markets and designed a synergistic mechanism, constructing optimal profit models for various entities and confirming that such synergy can increase the proportion of green power grid-connected in new power systems.

A growing strand of cutting-edge research investigates the role of digital technologies and precise mechanism design in enabling these new market paradigms and ensuring their credibility. Studies [35,36,37] have moved beyond traditional policy analysis by developing procedures for using high-frequency data from smart meters, highlighting the importance of data-driven management.

The potential of blockchain technology for creating decentralized, transparent, and efficient energy markets has been extensively addressed, with examples including studies of blockchain-based decentralized markets and peer-to-peer trade auctions [38,39,40,41,42]. The application of these technologies to solve specific credibility issues in GEC markets is particularly relevant. Research [43] pioneered the use of blockchain and graph computing to establish trustworthy green electricity tracing and certification platforms that enable full life cycle traceability. Wang et al. [44] contributed to this domain by designing an incentive-compatible mechanism for coordinating medium- and long-term markets with spot markets in high-penetration RE systems. Their three-stage framework, which employs machine learning for forecasting and develops a contract decomposition mechanism, demonstrates significant improvements in renewable energy utilization and a 13.47% improvement in GEC utilization efficiency.

Furthermore, Lu et al. [45] delved into the heart of environmental value quantification, designing a mechanism and constructing a model from the perspective of coal-fired power carbon abatement costs. Their analysis of the emission reduction value of green power provides a critical methodological foundation for rational pricing within the GEC and carbon markets, showing how the environmental value calculated based on marginal carbon abatement cost relates to GEC prices.

In summary, the existing body of literature provides valuable insights into the economic assessment of policies, their evolution towards integrated market-based mechanisms, and the potential of digital technologies. However, despite the existence of studies that begin to explore these themes in a more interconnected manner, a noticeable gap persists in the literature, as much of the existing work still examines policy mechanisms, market couplings, and enabling technologies in parallel rather than through a fully integrated analytical framework. While empirical work like Huang et al. [23] showed the limited consumption impact of standalone GECs, and technological studies propose tracing tools, the literature lacks a comprehensive framework that fully integrates these insights to address core market challenges like credibility deficits and the inability to generate verifiable “additionality”. While Pan et al. [46] modeled the tripartite market coupling to demonstrate cost optimization strategies for steel enterprises, study [32] empirically confirmed the significant contribution of certificate-electricity integration to regional emission reduction. However, these studies do not fully address the pivotal role of technology-enabled traceability. The potential of leveraging such precision to transform GECs into a credible, internationally accepted instrument that seamlessly integrates with carbon accounting and mitigates Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) liabilities constitutes a critical research gap.

Beyond the previously discussed institutional and technological gaps, the credibility of GECs is fundamentally challenged by the pervasive risk of greenwashing, a phenomenon well-documented across various environmental certification schemes and financial instruments. Studies show that firms may engage in the symbolic adoption of certifications for legitimacy, yielding minimal actual performance improvements [47,48], a risk exacerbated by information asymmetry and inadequate verification in voluntary markets [49,50]. This credibility deficit is not confined to traditional industries; research on emerging markets, such as African ESG bonds, underscores that without robust third-party certification, self-labeled “green” investments risk being mere marketing tools, failing to deliver tangible environmental benefits [51]. This cross-sectoral evidence highlights a fundamental challenge that is acutely present in GEC systems. Here, the inherent decoupling of environmental attributes from physical electricity is critically enabled by the prevailing practice of annual or monthly certificate matching. This coarse temporal granularity creates a significant disconnect between renewable generation and consumption, facilitating a form of “paper decarbonization” where corporate environmental claims can diverge from the grid’s real-time carbon intensity. Scholarly analyses have specifically linked this credibility gap to the technical limitations of low-granularity tracking [52,53,54,55,56], thereby fundamentally undermining the environmental integrity of GECs.

In response to these credibility challenges, the literature converges on a multi-faceted solution pathway that integrates market mechanism design, technological innovation, and insights from consumer behavior. The theoretical foundation is provided by game-theoretic models, which emphasize that a well-designed, truth-revealing certification mechanism is crucial for mitigating fraud and enhancing welfare, suggesting that policy support without robust certification can be counterproductive [52,53]. On a practical level, technological advancements are key to implementing this vision. The feasibility of high-precision traceability is supported by research on real-time optimization algorithms [54] and machine learning for generation forecasting [55], while blockchain technology is highlighted as a superior tool for ensuring tamper-proof transparency and trust compared to conventional systems [56,57].

Furthermore, the value and applicability of GECs can be expanded through strategic market integration. This includes creating innovative trading frameworks that explicitly link green electricity to carbon reduction attributes [58,59] and employing advanced computational methods like multi-agent reinforcement learning to optimize multi-market transactions [60]. The success of these mechanisms ultimately depends on stimulating genuine demand. Behavioral research confirms that consumer purchase intention is positively influenced by environmental concern and the perceived value of green certificates, underscoring the importance of credibility in fostering voluntary market uptake [61]. Therefore, advancing towards real-time, technology-backed traceability systems, underpinned by sound market rules and an understanding of stakeholder motivation, is posited as the essential direction for transforming GECs into a credible instrument for verifiable decarbonization.

By synthesizing the key themes identified in the literature review (see Table 1), this review posits that the key to bridging this gap lies in the development of systems that integrate market design, cross-market coupling, and robust digital traceability. Success in this integration will unlock the full potential of GECs, thereby driving genuine additional renewable energy consumption and thus offering a credible solution to global carbon mitigation challenges. This paper aims to address this precise gap by proposing an integrated framework that links real-time electricity-carbon traceability to the enhancement of GEC credibility and its practical applications.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Themes Identified in the Literature Review.

3. A Comparative Analysis of International GEC Mechanisms

Building on the scholarly foundations, a comparative analysis of international GEC mechanisms revealed a diverse yet converging landscape of approaches. Different jurisdictions have developed different certificates tailored to their specific contexts, but common trends point toward an evolution aimed at enhancing precision, credibility, and market integration.

3.1. Varied Models and Converging Goals in System Design

GEC systems in leading regions have evolved distinct characteristics. The European Union has developed a sophisticated system centered around Guarantees of Origin (GOs) within the binding framework of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) [62]. A significant recent development is the introduction of Granular Certificates (GCs) in RED III [63], mandating hourly matching for specific sectors like green hydrogen from 2027 onwards. This marks a decisive shift from annual/monthly tracking toward near-real-time precision, significantly enhancing credibility [64]. The United States exhibits a fragmented model, where state-level RPS create demand for Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs). While this leads to market complexity, it also fosters innovation at the state level, with some states allowing RECs to be used for compliance in regional carbon markets like RGGI, thereby expanding their application [65]. Australia employs a bifurcated system with separate certificates for large-scale (LGCs) and small-scale (STCs) generation, aiming to balance the development of centralized and distributed renewables through differentiated management [66]. The UK’s strategic transition from the Renewable Obligation (RO) mechanism, which operated through the issuance and trading of Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs), to the Contract for Difference (CfD) framework exemplifies a deliberate shift from a certificate-based quota system to a competitive auction model [67,68]. This evolution effectively stabilizes long-term revenue for renewable energy projects while controlling policy costs.

3.2. Common Evolutionary Trends in GEC Mechanisms

Despite their differences, these international experiences highlight several powerful, convergent trends that signal the future direction of GEC markets. A primary trend is the imperative for increased temporal precision, as exemplified by the EU’s move toward hourly matching. This shift underscores a global recognition that enhancing the temporal granularity of certification is fundamental to solving credibility issues and preventing double-counting. Concurrently, there is a clear drive for deeper market integration, demonstrated by practices in some U.S. states that link RECs to carbon markets. This reflects a growing effort to expand the application scenarios of GECs by creating synergies with other environmental commodity markets, thereby enhancing their utility and value. Furthermore, the refinement of price discovery mechanisms represents another key trend, illustrated by the UK’s adoption of CfDs. This evolution in price formation mechanisms aims to reduce market volatility, provide clearer long-term investment signals, and manage public expenditure more effectively. This comparative analysis demonstrates that while initial models varied significantly, the direction of travel is clear: successful GEC systems are increasingly relying on precision, market linkages, and stable price signals. This international context provides a crucial benchmark for analyzing the specific challenges and opportunities within the Chinese GEC market, which is the focus of the next section.

The following table (Table 2) provides a comparative overview of key mechanisms, highlighting their core features and evolutionary trajectories.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of International GEC Systems.

4. The Structural Dilemmas and Scenario Analysis of China’s GEC Market

The China’s GEC market, while developing rapidly, faces multiple structural dilemmas that necessitate scientific scenario analysis to identify pathways for improvement. This section systematically examines these inherent challenges and explores potential application scenarios, providing a comprehensive analysis framework to inform strategic policy design and market mechanism optimization.

4.1. Structural Dilemmas of China’s GEC Market

The development of China’s GEC market is constrained by several interconnected structural challenges, with a primary issue being the severe oversupply of certificates. By the end of 2024, the cumulative issuance of GECs had far exceeded transaction volumes, resulting in a pronounced buyer’s market. This supply demand imbalance, however, does not stem from a lack of mandatory consumption obligations. In fact, a significant portion of GEC purchases in China is driven by policy compliance, particularly evident in the year-end surge in trading activity aimed at meeting quota requirements.

Nevertheless, when viewed over the entire year, transaction volumes remain substantially lower than the number of certificates issued, indicating that endogenous market demand has yet to mature. While mandatory policy compliance can stimulate short-term transactions, it fails to generate steady and sustainable market demand. Overreliance on administrative measures, as noted in studies [69,70,71], tends to distort market mechanisms and is unsustainable in the long run. This highlights the urgency of fostering market-based demand mechanisms. Only by improving market design and enhancing voluntary corporate purchasing incentives can the long-term healthy development of China’s GEC market be achieved.

Furthermore, a critical disconnect exists between the GEC market and the CET. The environmental attributes certified by GECs are not yet seamlessly integrated into corporate carbon accounting systems, preventing GECs from being used for carbon emission deductions [72,73,74,75]. This isolation severely limits the value proposition and application scenarios of GECs. Additionally, the current mechanism lacks temporal precision. Certificates are issued based on monthly or annual energy generation data, failing to reflect real-time electricity consumption patterns. This coarse-grained approach undermines the credibility of green electricity claims [76] and hampers the development of high-value applications like 24/7 hourly matching of clean energy [77,78,79,80].

4.2. Scenario Analysis and Application Pathways for GECs

As outlined in Table 3, despite the challenges, GECs hold significant potential across multiple application scenarios, each with distinct value propositions and implementation requirements. The analysis can be categorized into three primary pathways based on the degree of marketization and the binding nature of the mechanisms.

Table 3.

Series Policy System of GECs in China.

Compliance-Driven Scenarios: This pathway involves using GECs to fulfill mandatory policy requirements. The most direct application is within a mandatory RPS framework, where obligated entities (e.g., grid companies, large electricity consumers) purchase GECs to meet their renewable energy consumption quotas. The design of the RPS, including the quota ratio, compliance entities, and penalty mechanisms, directly determines the market size and price of GECs. Another compliance application is the integration with the national carbon market. By establishing a linkage mechanism, companies could use GECs to offset a portion of their carbon emissions, thereby expanding the demand base for GECs and creating price linkages between the two environmental markets.

Corporate Voluntary Emission Reduction Scenarios: This pathway leverages GECs for corporate voluntary environmental goals. Many multinational corporations and leading domestic companies have made commitments to RE100 or carbon neutrality. Purchasing GECs provides them with a credible tool to verify and report the green attributes of their electricity consumption, reducing their Scope 2 carbon emissions. This enhances their ESG performance and strengthens their brand image [90]. Different industries have varying motivations and implementation models for procuring GECs.

However, the growth potential of this voluntary corporate demand is intrinsically linked to the overall credibility and market dynamics of the GEC system. To contextualize these corporate scenarios within the broader market framework, a detailed analysis of the latest issuance and transaction data is essential. The following examination of market performance from 2023 to 2025 revealed the structural opportunities and constraints that directly impact corporate procurement strategies.

Analysis of China’s GEC market data from 2023 to the first quarter of 2025 revealed both significant achievements and structural challenges. As shown in Table 4, renewable energy generation increased from 2.95 trillion kWh in 2023 to 3.46 trillion kWh in 2024, indicating the sector’s transition toward scale development and quality enhancement. The breakthrough in full-volume certificate issuance in 2024, covering all registered renewable energy projects with issued certificates reaching 4.734 trillion kWh, systematically addressed the historical backlog of certificate issuance. The cumulative issuance volume over two years accounted for 76.59% of total renewable energy generation during the same period, resolving previous issues of long issuance cycles and incomplete coverage. The following table provides detailed quantitative evidence supporting these observations.

Table 4.

Issuance and trading inventory data of RE and GECs. Unit: Trillion kWh.

Note 1: Renewable energy generation data for Q1 2025 is estimated. Total clean energy generation was 0.7 trillion kWh, with nuclear power accounting for one-seventh. After deducting nuclear power generation, renewable energy generation amounts to 0.6 trillion kWh.

Note 2: “Bundled GECs” (Certificate-Power Integration) refer to the simultaneous procurement of both the green certificate and the corresponding physical electricity within a single contract [91], where both the use value and environmental attributes of the renewable electricity are transferred upon transaction. “Unbundled GECs” (Certificate-Power Separation) indicate that the buyer acquires only the environmental attributes, which does not necessarily correspond to the physical consumption of the specific renewable electricity.

Value-Added and Innovative Scenarios: This pathway explores innovative applications that create additional value. A promising direction is the use of GECs for certifying the green attributes of specific products, known as “green power products”. This allows downstream manufacturers to differentiate their products in the market, potentially gaining a premium. Furthermore, with the advancement of metering and blockchain technologies, future applications could achieve hourly matching of green electricity consumption [92,93]. This high-precision certification is particularly crucial for emerging sectors like green hydrogen production [94] and data centers, supporting their participation in international markets and compliance with mechanisms like the EU’s CBAM [95]. The successful implementation of these innovative scenarios, however, depends on overcoming the current structural dilemmas, particularly the lack of temporal precision.

4.3. Synthesis and Policy Implications

Scenario analysis indicates that while China’s GEC market holds diverse and promising application pathways, its broader development remains constrained by fundamental structural challenges. Among these, stimulating endogenous market demand—rather than relying solely on policy enforcement—represents the most critical and urgent step to address the current supply demand imbalance.

Shifting from a policy-dependent model to one driven by genuine market engagement is essential to unlock the system’s full potential. This can be supported by strategically integrating the GEC market with the national CET, which would enhance the value proposition of green certificates and expand their practical application scenarios. Furthermore, investing in digital infrastructure to enable granular, time-stamped certificate issuance and verification will be crucial for fostering high-value applications—such as 24/7 hourly matching of clean energy—while significantly improving market credibility.

Only through a coordinated approach that prioritizes market-based incentives, cross-market synergy, and technological innovation can China’s GEC mechanism evolve into an effective instrument for accelerating renewable energy consumption and supporting the nation’s dual carbon goals.

5. Real-Time Electricity-Carbon Traceability

Real-time electricity-carbon traceability technology serves as a critical enabler for enhancing the credibility of green certificate markets and achieving precise allocation of environmental attributes. This section provides a synthesized review of the architectural frameworks, key technological advancements, and functional implementations that underpin these systems, moving beyond proposal to a comprehensive assessment of existing and emerging technical pathways.

5.1. The Architecture of Real-Time Traceability Systems

The architecture of real-time traceability systems typically comprises three core layers: a data acquisition layer, a model and algorithm layer, and an application service layer. The data acquisition layer is responsible for collecting high-frequency, multi-source data, including power generation data from renewable and conventional plants, electricity flow data from the grid, and consumption data from end-users. This layer relies heavily on the deployment of smart meters, phasor measurement units (PMUs), and IoT sensors to ensure data completeness and temporal resolution [96,97,98,99]. The model and algorithm layer processes these raw data to compute key metrics. Core computational models include the Carbon Emission Flow (CEF) theory for allocating carbon obligations across the network and various optimization algorithms for certificate issuance and matching [100,101,102,103,104,105]. The application service layer provides user-oriented functions such as certificate management, verification services, and carbon accounting interfaces, often delivered through cloud platforms or blockchain-based decentralized applications [106,107,108,109,110]. This layered architecture ensures scalability, reliability, and flexibility in supporting various market mechanisms and regulatory requirements.

5.2. Enhancing Credibility: From Annual to Hourly Granularity

A significant technological evolution in traceability systems is the shift from annual or monthly accounting to hourly and near-real-time granularity. This enhancement is fundamental to solving the credibility issues of traditional green certificates, such as double-counting and the lack of temporal correlation between generation and consumption. The implementation of hourly matching requires advancements in several key technologies. High-frequency data collection and processing capabilities are paramount, necessitating robust telecommunications infrastructure and edge computing resources to handle the vast data volumes. Furthermore, sophisticated algorithms for the allocation and matching of environmental attributes in minute-level or hourly timescales must be developed [111,112]. These algorithms must align with physical power dispatch principles to ensure that the traced carbon and green attributes accurately reflect the actual flow of electricity. The adoption of this high temporal precision is increasingly mandated in international standards and is particularly critical for certifying the green attributes of emerging commodities like green hydrogen, as stipulated in the EU’s RED III.

5.3. Enabling Carbon Footprint Accounting: The Data Foundation

The ultimate value of a traceability system lies in its ability to provide a reliable data foundation for carbon footprint accounting, thereby bridging the gap between green certificate markets and carbon markets. The core technological component here is the accurate calculation of the carbon emission factor for electricity consumption at any node in the grid and for any specific period. This is achieved by applying CEF theory, which traces the carbon content of electricity from generation sources through the transmission and distribution network to the final consumers. The calculated node-carbon intensity provides a scientific basis for allocating carbon responsibility [113,114]. This data foundation enables several key applications: it allows enterprises to accurately calculate and report the Scope 2 emissions based on their electricity consumption; it provides a basis for regulators to verify the authenticity of green electricity claims and prevent double-counting; and it creates the possibility for the future integration of GECs and carbon emission allowances (CEA), allowing for the potential offset or deduction of carbon emissions through the purchase of green certificates. The robustness and accuracy of these underlying algorithms directly determine the credibility and wider applicability of the entire market mechanism.

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

Based on the comprehensive review of international experiences, market dilemmas, and technological pathways presented in the preceding sections, this section proposes an integrated theoretical framework and derives specific policy implications aimed at addressing the core dilemmas of China’s GEC market and enhancing its effectiveness.

This section elaborates the internal structure and implementation pathway of the proposed real-time traceability framework, articulating its conceptual logic and practical feasibility with greater clarity.

6.1. An Integrated Framework Bridging Technology, Market, and Policy

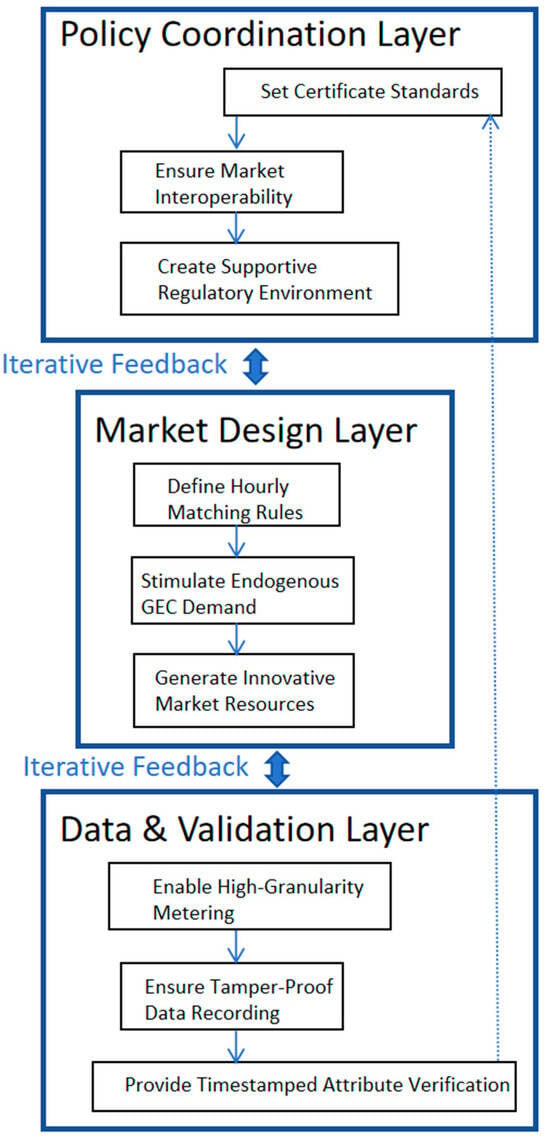

The synthesis of evidence indicates that the efficacy of a GEC market is not determined by a single factor but emerges from the synergistic interactions between technology, market mechanisms, and policy design. To conceptualize this, we propose an integrated framework that illustrates how these three core elements interconnect and mutually reinforce each other to drive a credible and efficient renewable energy attribution system. Advanced traceability technologies, characterized by high temporal granularity (e.g., hourly matching) and robust data integrity (e.g., via blockchain), provide the foundational credibility. They ensure the accurate and tamper-proof accounting of environmental attributes from generation to consumption, which is the prerequisite for stimulating corporate voluntary purchasing.

The framework comprises three mutually reinforcing layers: (1) a market-design layer governing certificate issuance, matching rules, and pricing signals; (2) a data and verification layer enabling real-time measurement, timestamping, and integrity assurance of renewable energy attributes; and (3) a policy coordination layer connecting the GEC system with other environmental markets such as the CET scheme. This layered structure clarifies the logical architecture of the framework and enhances its structural clarity.

This technological capability directly enables and empowers precise market mechanisms. Rather than relying solely on mandatory quotas, the market should focus on mechanisms that stimulate endogenous demand, such as enhancing the value proposition of GECs through seamless integration with carbon markets and corporate ESG frameworks. This integration expands their application scenarios and intrinsic value, thereby incentivizing voluntary purchases and reducing dependency on administrative coercion. The market, in turn, generates the demand and financial resources for further technological innovation and deployment.

Finally, supportive policy and regulation should evolve from direct intervention to a macro-governance role that guides and facilitates this transition. Policies should aim to set clear standards for certificate issuance and retirement, ensure interoperability between different environmental markets, and create an enabling environment for market-based transactions. The continuous feedback among these three domains—where policy shapes the market environment, the market drives technological adoption, and technology validates policy outcomes—creates a virtuous cycle that transforms the GEC system from a policy-driven tool into a market-driven engine for verifiable renewable energy consumption. This framework provides a holistic lens for diagnosing market failures and designing targeted interventions that prioritize market vitality over administrative control.

The implementation pathway for the framework is structured in phased steps: initial upgrades to metering infrastructure and dynamic emission factor modeling; followed by establishment of a unified, tamper-proof traceability ledger for timestamped attribute recording; and finally, integration of verified attributes into market transactions, corporate reporting, and CET linkages. Throughout this process, grid companies, certificate registries, renewable generators, digital platform operators, and regulators fulfill distinct yet complementary roles. This phased approach demonstrates operational feasibility and offers practical implementation guidance.

Figure 2 presents a conceptual diagram illustrating the interactions and information flows among the three layers of the framework. This schematic provides a high-level overview of the interplay between data, market rules, and policy instruments within the proposed real-time traceability architecture.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework of the Real-Time Electricity-Carbon Traceability System. Note: 1. Solid Arrow: Represents a direct promoting relationship. 2. Dashed Arrow: Indicates a potential or possible promoting relationship. 3. Double-headed Arrow: Denotes bidirectional feedback or interaction between layers.

6.2. Policy Implications

The integrated framework and the preceding analysis lead to several concrete and interconnected policy implications for the evolution of China’s GEC market. Firstly, fostering endogenous market demand, rather than relying solely on top-down mandates, represents the most critical and strategic direction. Policy should focus on creating an enabling environment that incentivizes voluntary purchases by corporates and institutions, for instance, by enhancing the value proposition of GECs through recognition within carbon accounting frameworks and ESG compliance mechanisms. This approach cultivates stable, market-driven demand essential to resolving the fundamental issue of oversupply and low liquidity, while gradually reducing dependency on administrative enforcement.

Secondly, policy should mandate and support the transition to hourly granularity in certificate issuance and matching. Shifting from annual or monthly averaging to near-real-time accounting is fundamental to enhancing credibility, preventing double-counting, and unlocking high-value applications such as 24/7 clean energy matching for green hydrogen production, and data centers. This technical upgrade is a prerequisite for market sophistication.

Thirdly, policymakers should actively facilitate the deep integration of GEC and CET markets. This can be achieved by establishing a robust and transparent accounting protocol that allows enterprises to use GECs to deduct their Scope 2 emissions within the CET scheme, thereby creating a direct price linkage and significantly expanding the utility and economic value of GECs. This synergy is a powerful market-based mechanism to drive demand.

Finally, significant public and private investment should be directed towards building the digital public infrastructure required for high-integrity traceability. This includes the widespread deployment of smart meters, the development of interoperable and secure data platforms, and the adoption of blockchain technology to ensure the immutability and transparency of the entire GEC lifecycle. Such infrastructure empowers market participants and ensures trust.

These policy actions, derived from a synthesis of international lessons and local challenges, are essential for transforming China’s GEC market from a policy-led mechanism into a credible, market-driven instrument for achieving its dual carbon goals. The overarching principle is to use policy to guide, enable, and catalyze market forces—not to replace them.

7. Conclusions and Research Prospects

7.1. Conclusions

This review synthesizes global evidence to establish that real-time electricity-carbon traceability constitutes a fundamental paradigm shift for GEC markets, transitioning from coarse-grained annual accounting toward a high-resolution, credible system capable of near-real-time environmental attribution. We demonstrate that the core challenges plaguing China’s GEC market—persistent oversupply, low liquidity, and insufficient credibility—are interlinked symptoms stemming from a misalignment among market mechanisms, policy frameworks, and technological capabilities. The proposed integrated framework reveals that the solution resides not in isolated fixes but in the strategic synergy of three domains: fostering endogenous market demand through value-enhancing mechanisms, deepening integration with carbon markets to unlock scalable value, and deploying granular traceability technologies to ensure integrity and enable high-value applications. International comparisons affirm that the global trajectory toward precision, integration, and digitization offers a clear benchmark for China’s reform. Ultimately, the successful evolution of the GEC system is pivotal for China to effectively harness market forces in driving verifiable renewable energy consumption and fulfilling its ambitious carbon neutrality goals.

7.2. Research Prospects

While this review outlines a clear pathway, it also reveals several critical gaps that present rich opportunities for future research. Firstly, as traceability systems require the collection and processing of vast amounts of high-frequency energy data, data privacy and security emerge as paramount concerns. Future research must develop robust cryptographic frameworks and governance models that ensure data can be utilized for public good while protecting the privacy and commercial interests of all market participants. Secondly, the rapid rise of distributed energy resources like rooftop solar and battery storage demands new algorithms for traceability in decentralized systems. Current centralized tracking models may be inadequate. Research is needed into decentralized or hybrid tracing models that can efficiently and accurately allocate environmental attributes in a system with millions of prosumers. Thirdly, the socio-economic impacts of the transition to a high-precision GEC market require thorough investigation. Research should explore the cost–benefit analysis for different stakeholders, the potential impact on electricity prices, and strategies to ensure a just transition that does not disproportionately burden certain consumer groups or hinder the competitiveness of energy-intensive industries. Finally, the international interoperability of GEC systems is a frontier topic. As mechanisms like the EU’s CBAM take effect, research is urgently needed on how to harmonize China’s domestic traceability standards with international frameworks to ensure that Chinese green products are recognized in the global market, thereby turning its green ambition into a competitive advantage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., H.W. and L.Z.; Methodology, L.X.; Investigation, J.H., L.X., S.L., L.T. and Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, J.H., L.X. and H.W.; Writing—review and editing, L.Z., L.T., S.L., Y.Z., Y.G. and Z.H.; Supervision, H.W. and Z.H.; Project administration, H.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.G. and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program “Methodology and Demonstration of Life Cycle Assessment of High Carbon Emission Products” funded by the Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province (No. 202303AC100004).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Li Zhang was employed by the company IKE Environmental Technology Company. Authors Shenzhang Li, Yanjie Zhu, Yudou Gao and Zuyuan Huang were employed by the company Yunnan Power Grid Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Thompson, S. Strategic Analysis of the Renewable Electricity Transition: Power to the World without Carbon Emissions? Energies 2023, 16, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Feng, T.; Cui, M.; Liu, L. Mechanisms and Motivations: Green Electricity Trading in China’s High-Energy-Consuming Industries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z. Analysis of Key Factors for New Energy Absorption and Research on Solutions. Proc. CSEE 2017, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, B.; Cai, Z. Risk Assessment of New Energy Consumption Capacity Considering Node Vulnerability. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 44, 4479–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, F. Refined Evaluation of Absorption Resistance of System with High Proportion of New Energy for Network Nodes. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2022, 41, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Li, H.W.; Zheng, G.; Sun, L.C. Research on Renewable Energy Accommodation Assessment Method Based on Time-series Production Simulation. Acta Energy Sol. Sin. 2020, 41, 26–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Jin, K.; Hou, B.; Wang, W. Control Strategy of Load Time-Shifting and Local Photovoltaic Consumption in Facility Agriculture Based on Energy Blockchain. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 47–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Yu, Q.; He, G. Collaborative Optimization Strategy for Multi-Microgrid Considering Spatio-Temporal Correlation of Distributed Hydro–Wind–Solar Power Generation. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2025, 53, 23–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Current Status and Existing Problems in the Construction of Green Electricity Market System. Energy Conserv. Nonferrous Metall. 2022, 38, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Collaborative Development and Policy Recommendations for Green Electricity and Green Certificates in the Context of New Power Systems. J. N. China Electr. Power Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 06, 63–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Xie, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, N.; Wu, S. Key Issues in the Construction of China’s Green Electricity Market Under the Dual-Carbon Goals. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 25–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Li, C.; Ban, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. A Multi-Market Equilibrium Model Considering the Carbon-Green Certificate Mutual Recognition Trading Mechanism under the Electricity Market. Energy 2025, 330, 136902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Chi, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, S.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Y. Analysis on the Synergy between Markets of Electricity, Carbon, and Tradable Green Certificates in China. Energy 2024, 302, 131808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. Dynamic Evolution of Electricity Price Transmission Effects from Electricity-Carbon Market Coupling under Tradable Green Certificate Price Regulation. Energy 2025, 334, 137861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, N.; Chen, Z.; Leng, Y. Mutual Recognition Mechanism and Key Technologies of Typical Environmental Interest Productsin Power and CET markets. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 2558–2577. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.; Li, Y.; Chang, L.; Qian, J.; Tu, S. Analysis of the Coupling Mechanism between Carbon and Electricity Markets under China’s Carbon Control Trend. Integr. Intell. Energy 2025, 47, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Che, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, S. Optimal Modelling and Analysis of DG-GC Joint Multilateral Transaction in Energy Blockchain Environment: From the REP Perspective. Energy 2025, 335, 137952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zeng, M. Key Blockchain Technologies for Synergistic Operation of Electricity–Carbon–Green Certificate Markets in New Power Systems. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 44, 1–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, W. A Blockchain Model Connecting Electricity Market and Carbon Trading Market. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 119, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.; Li, Y.P.; Jin, S.W.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.F.; Feng, R.F. Identifying Optimal Clean-Production Pattern for Energy Systems under Uncertainty through Introducing Carbon Emission Trading and Green Certificate Schemes. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Huang, G.; Li, Y. Analyzing the Carbon Mitigation Potential of Tradable Green Certificates Based on a GEC-FFSRO Model: A Case Study in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, W. The Development of Renewable Energy Industry under Renewable Portfolio Standards: From the Perspective of Provincial Resource Differences. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Leng, Y.; Shang, N.; Hu, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wen, H. Green Certificate Trading, Renewable Energy Investment and Its Absorption. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 40, 181–189. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Han, J.; Shan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, J.; Kou, Y. Efficiency of Tradable Green Certificate Markets in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, F.; Egli, F.; Steffen, B.; Schmidt, T.S. How Do Policies Mobilize Private Finance for Renewable Energy?—A Systematic Review with an Investor Perspective. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 1249–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, R.; Grafakos, S.; Gianoli, A.; Stavropoulos, S. Which Policy Instruments Attract Foreign Direct Investments in Renewable Energy? Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Peng, C.; Jian, J.; Zheng, J. Can Green Certificates Substitute for Renewable Electricity Subsidies? A Chinese Experience. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, M. How to Promote the Trading in China’s Green Electricity Market? Based on Environmental Perceptions, Renewable Portfolio Standard and Subsidies. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, N.; Chen, Z.; Lu, Z.; Leng, Y. Interaction Principle and Cohesive Mechanism Between Electricity Market, CET market and Green Power Certiffcate Market. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 142–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Mi, F. Renewable Portfolio Standards, Carbon Emissions Trading and China Certified Emission Reduction: The Role of Market Mechanisms in Optimizing China’s Power Generation Structure. Energies 2025, 18, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.T.I.; Law, A.O.K. Financing for Renewable Energy Projects: A Decision Guide by Developmental Stages with Case Studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, Z.; Shang, N.; Hu, X.; Wang, C.; Wen, H.; Liu, Z. Do Tradable Green Certificates Promote Regional Carbon Emissions Reduction for Sustainable Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhong, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, B. Optimal and Sustainable Scheduling of Integrated Energy System Coupled with CCS-P2G and Waste-to-Energy Under the “Green-Carbon” Offset Mechanism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, M.; An, L.; Lu, Y.; Zha, D.; Liu, L.; Feng, T. Research on the Synergistic Mechanism Design of Electricity-CET-GEC Markets and Transaction Strategies for Multiple Entities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, A.; Singh, A.; Mahanti, A. Detecting Anomalous Energy Consumption Using Contextual Analysis of Smart Meter Data. Wirel. Netw 2021, 27, 4275–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Haydarov, K.; Haq, I.U.; Muhammad, K.; Rho, S.; Lee, M.; Baik, S.W. Deep Learning Assisted Buildings Energy Consumption Profiling Using Smart Meter Data. Sensors 2020, 20, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korakianitis, N.; Papageorgas, P.; Vokas, G.; Piromalis, D.; Kaminaris, S.; Ioannidis, G.; Zuazola, A. Design and Evaluation of a Research-Oriented Open-Source Platform for Smart Grid Metering: A Comprehensive Review and Experimental Intercomparison of Smart Meter Technologies. Future Internet 2025, 17, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Myeong, S. A Comprehensive Study of Blockchain Technology and Its Role in Promoting Sustainability and Circularity across Large-Scale Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmat, A.; de Vos, M.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Palensky, P.; Epema, D. A Novel Decentralized Platform for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Market with Blockchain Technology. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, W.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y.; Li, K. An Efficient, Secured, and Infinitely Scalable Consensus Mechanism for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 5215–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Ou, X.; Chen, B. Blockchain-Based Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: A Decentralized and Innovative Approach for Sustainable Local Markets. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Wen, F.; Afzal, M.Z. Decentralized Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading in Microgrids: Leveraging Blockchain Technology and Smart Contracts. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, G. Preliminary Study on Key Technologies of Blockchain-Based Collaborative Sharing for Green Electricity Tracing and Certification. Distrib. Util. 2022, 39, 27–35, 57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Yan, S.; Li, Q. Incentive-Compatible Mechanism Design for Medium- and Long-Term/Spot Market Coordination in High-Penetration Renewable Energy Systems. Processes 2025, 13, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.; An, L.; Geng, P.; Liu, L.; Feng, T. Design and Evaluation of Environmental Value Mechanisms for Green Power Considering Carbon Reductions. Energies 2025, 18, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Xue, S.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z. Modeling the Tripartite Coupling Dynamics of Electricity–Carbon–Renewable Certificate Markets: A System Dynamics Approach. Processes 2025, 13, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Ren, S.; Zeng, H. Environmental labeling certification and firm environmental and financial performance: A resource management perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 31, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Environmental management certification and environmental performance: Greening or greenwashing? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2829–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, M.; Wu, M.; Wang, A. Voluntary environmental regulations, greenwashing and green innovation: Empirical study of China’s ISO14001 certification. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M. Third-party certification: How to effectively prevent greenwash in green bond market? –analysis based on signalling game. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 16173–16199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutarindwa, S.; Schäfer, D.; Stephan, A. Certification against greenwashing in nascent bond markets: Lessons from African ESG bonds. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittreich, T. Environmental Certification, Consumer Greenness, and Greenwashing. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2025, 46, 2289–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, C.; Blanco, E. On fraud and certification of green production. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2024, 34, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albogamy, F.R.; Hafeez, G.; Khan, I.; Ullah, Z.; Basit, A.; Amjad, M.; Rehman, A.U. Real-Time Scheduling for Optimal Energy Optimization in Smart Grid Integrated With Renewable Energy Sources. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 35498–35520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Vinopraba, T.; Chandrasekaran, K. Machine learning based demand response scheme for IoT enabled PV integrated smart building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.; Silkoset, R. Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Qin, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Ding, B.; Han, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, K. A review of the synergistic research on electricity and carbon in new power systems: Quantitative methods, key technologies and application prospects. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 1–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, K.; Xu, W. Application research of green power trading and carbon emission trading in zero-carbon buildings. Build. Sci. 2024, 40, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Qiao, S.; Zhou, H.; Luo, R.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Mechanism design and consumption certification of differentiated green electricity trading: A Zhejiang experience. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 967290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, J.; Shi, R.; He, Y.; Wu, M. Author Correction: Enhancing renewable energy certificate transactions through reinforcement learning and smart contracts integration. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Measuring purchase intention towards green power certificate in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulshof, D.; Jepma, C.; Mulder, M. Performance of Markets for European Renewable Energy Certificates. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Promotion of Energy from Renewable Sources, and Repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. Official Journal of the European Union, L 2023/2413, 31.10.2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Shi, J. Comparison and Enlightenment: The Pros and Cons of Green Certificate Mechanisms in Europe, the United States and China. Energy 2019, 11, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, J. Do Renewable Portfolio Standards Increase Renewable Energy Capacity? Evidence from the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Diaz-Rainey, I.; Kuruppuarachchi, D. The Interplay of Carbon Offset, Renewable Energy Certificate and Electricity Markets in Australia. Energy Econ. 2025, 144, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; O’Leary, N.; Shao, J. Excess Demand or Excess Supply? A Comparison of Renewable Energy Certificate Markets in the United Kingdom and Australia. Util. Policy 2024, 86, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverwood, J.; Jackson, J. The environmental state: Analysing the ‘creation’ of renewable energy markets in the United Kingdom. Compet. Change 2025, 10245294251346944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wȩdzik, A.; Siewierski, T.; Szypowski, M. Green certificates market in Poland—The sources of crisis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 75, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jin, L.; Ding, L.; Xie, Z.; Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P. Comprehensive Risk Assessment of Green Power Market Operation. Guangdong Electr. Power 2025, 38, 14–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Song, X.; Yang, H.; Zhai, X.; Han, J.; Ju, L. Multi-Scale Market Transaction Simulation of Electricity-Green Certificate-Excess Consumption Under the New RPS. J. Syst. Simul. 2022, 34, 2458–2469. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, J. Synergistic Effect of Market Participants in Green Certificate-Carbon-CCER Markets. China Electr. Power 2025, 58, 109–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, S.; Li, C.; Yuan, M. Optimal Operation of Integrated Energy System Considering Energy-Carbon Coupling Response under Green Certificate-Carbon Market Mutual Recognition Mechanism. Proc. CSEE 2025, 1–19. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2107.TM.20250708.1603.003 (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese).

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Incentive-Oriented Power-carbon Emissions Trading-Tradable Green Certificate Integrated Market Mechanisms Using Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Yu, T.; Wang, Y. The Coupling Effect of Carbon Emission Trading and Tradable Green Certificates under Electricity Marketization in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, B.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Xu, J. Carbon Trading Mechanism for Distributed Green Energy and Challenges of Carbon Data Management. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 56, 977–993. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. Beyond 100% Renewable: Policy and Practical Pathways to 24/7 Renewable Energy Procurement. Electr. J. 2020, 33, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Manocha, A.; Patankar, N.; Jenkins, J. System-level impacts of 24/7 carbon-free electricity procurement. Available SSRN 2021, 4248431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepin, I.; Brown, T. On the Means, Costs, and System-Level Impacts of 24/7 Carbon-Free Energy Procurement. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On the Development of Corporate Renewable Energy Procurement and Economic Modeling of Hourly Green Certificate Market. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/74f50e59-97e8-4039-a7e7-1095bb5b4b2c (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Zhong, L. Two Ministries and Commissions Jointly Issue the “Notice on Doing a Good Job in the Connection between Renewable Energy Green Electricity Certificates and the Voluntary Emission Reduction Market”. Fine Spec. Chem. 2024, 32, 19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission. Notice on Actively Promoting Grid-Parity and Low-Cost Grid-Connection for Wind and PV Power Generation. 2019. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201901/t20190109_962365.html (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission; National Energy Administration. Notice on Establishing and Improving a Renewable Energy Consumption Guarantee Mechanism. 2019. Available online: https://zfxxgk.ndrc.gov.cn/web/iteminfo.jsp?id=16176 (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission. Reply Letter on the Pilot Work Plan for Green Electricity Trading. 2021. Available online: https://www.pvmeng.com/2021/08/28/21253/ (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese).

- National Development and Reform Commission. Notice on Further Improving the Work Related to Excluding Newly Added Renewable Energy Consumption from Total Energy Consumption Control. 2022. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/tzgg/202211/t20221116_1341324.html (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission; National Energy Administration. Notice on Achieving Full Coverage of Renewable Energy Green Electricity Certificates and Promoting Renewable Energy Electricity Consumption. 2023. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/tzgg/202308/t20230803_1359093.html (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission; National Bureau of Statistics; National Energy Administration. Notice on Strengthening the Linkage Between Green Electricity Certificates and Energy-Saving Carbon-Reduction Policies, and Vigorously Promoting Non-Fossil Energy Consumption. 2024. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/jd/202402/t20240202_1363868.html (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Energy Administration. Notice on Printing and Distributing the “Rules for the Issuance and Trading of Renewable Energy Green Electricity Certificates”. 2024. Available online: https://zfxxgk.nea.gov.cn/2024-08/26/c_1310785819.htm (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission; National Bureau of Statistics; National Energy Administration. Guidelines on Promoting the High-Quality Development of the Renewable Energy Green Electricity Certificate Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202503/content_7014341.htm (accessed on 8 May 2025). (In Chinese)

- Lin, H.; Ying, Q. The Impact of Green Factory Certification on ESG Performance among Selected Chinese Companies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X. Launch of Green Electricity Trading Pilot to Promote the Construction of Green Electricity Market China. Electr. Eng. 2021, 11, 64–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.J.; Novan, K.; Jenn, A. Hourly Accounting of Carbon Emissions from Electricity Consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholta, H.F.; Blaschke, M.J. Temporal Matching as an Accounting Principle for Green Electricity Claims. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendi, M.; Mersch, M.; Mac Dowell, N. Electrolytic Hydrogen Production; How Green Must Green Be? iScience 2025, 28, 111955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Regulation-2023/956-EN-Cbam Regulation-EUR-Lex. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/956/oj/eng (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Du, E.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Kang, C. Carbon Emission Measurement Methods and Carbon Meter System for All Segments of Power System. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 2–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Song, J.; Deng, H.; Du, E.; Zhang, N.; Kang, C. Review of Carbon Emission Measurement and Analysis Methods for Power Systems. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 2220–2236. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Gao, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Y. Probabilistic Carbon Emission Flow Calculation for New Power Systems Considering Losses and Correlation. Distrib. Util. 2024, 41, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, X.; Shen, Y. Optimal Dispatch Method for Integrated Electricity-Carbon Demand Response in New Power Systems Considering Dynamic Carbon Emission Factors. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2024, 44, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Q. A Preliminary Study on the Theory of Carbon Emission Flow Analysis in Power Systems. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2012, 36, 38–43+85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Q. A Preliminary Study on the Calculation Method of Carbon Emission Flow in Power Systems. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2012, 36, 44–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H. Carbon Emission Flow Analysis Method for Active Distribution Network Based on Power Flow Tracing. Zhejiang Electr. 2024, 43, 80–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y. Optimal power scheduling using data-driven carbon emission flow modelling for carbon intensity control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 37, 2894–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Tian, G.; Wu, Z. Examining embodied carbon emission flow relationships among different industrial sectors in China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J. Low-carbon optimal learning scheduling of the power system based on carbon capture system and carbon emission flow theory. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 218, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hu, Z.; Song, Y.; Fang, X.; Yang, J. Assessment Principles and Models for Carbon Emission Intensity of Electricity at User Side. Power Syst. Technol. 2012, 36, 6–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Q.; Lu, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q. Calculation and Evaluation Method of User Carbon Emission Level Based on Power Flow Tracing. Electr. Mach. Control Appl. 2024, 51, 22–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hua, H.; Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Qin, Y.; Wang, B.; Yu, K.; Naidoo, P. Carbon emission flow based energy routing strategy in energy Internet. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 3974–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, W.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, C.; Song, J.; Kang, C. A distributed computing algorithm for electricity carbon emission flow and carbon emission intensity. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Wang, T. The spatial characteristics of embodied carbon emission flow in Chinese provinces: A network-based perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 34955–34973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, D. Evolution of Research Direction and Application Requirements for Grid Carbon Emission Factor. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 12–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Y. Research on Green Certificate Market Trading Based on Time-Sequence Simulation of Renewable Energy Economic Dispatch. Smart Power 2021, 49, 58–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, B.; Zhou, M.; Han, P. Low-Carbon Operation Simulation Method for Power System Based on Source-Side Carbon Emission Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 27, 78–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Shu, Y.; Huang, H.; Shu, A.; Ye, J.; Zhu, H. Calculation of Time-of-Use and Zonal Carbon Emission Factors and Its Application in Product Carbon Footprint Accounting. Eng. Sci. 2025, 27, 93–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.