Abstract

To address interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production in gas reservoirs with pressure differences, this study investigates the low-permeability gas reservoir in the central Linxing area of the Ordos Basin. High-temperature, high-pressure physical simulation experiments were conducted to systematically study single-layer, two-layer, and three-layer commingled production under different pressures (13, 15, and 17 MPa). A large-scale physical simulation system, capable of withstanding 100 °C and 50 MPa, was constructed for the dynamic monitoring of multi-layer commingled production. This system accurately characterized the instantaneous gas production, cumulative gas production, and pressure drop behavior of individual layers under both single-layer and commingled production conditions. The results indicate that significant interlayer interference occurs during multi-layer commingled production. This interference is primarily manifested as a capacity inhibition effect, where the high-pressure layer suppresses the production of the low-pressure layer. Typical phenomena accompanying this effect include ‘backflow’ and ‘staggered production peaks’. Quantitative analysis indicates that the cumulative gas production for two-layer and three-layer commingled production is 3.2% and 9.06% lower, respectively, than the summed production from equivalent single-layer operations. Notably, in the three-layer commingled production scenario, the productivity of the low-pressure layer (Q5) was reduced by 19.87%, a significantly greater loss compared to the 4.39% reduction observed in the high-pressure layer (T2). Furthermore, the study demonstrates that the severity of interlayer interference is positively correlated with the interlayer pressure difference. Additionally, as the number of commingled layers increases, the interference effect exhibits a superimposed enhancement characteristic.

1. Introduction

China, as the world’s largest energy consumer, has long maintained a coal-dominant energy structure. This reliance poses significant challenges, including energy security risks, environmental pollution, and substantial carbon emissions. Rapid economic and social development continues to drive growth in energy demand. However, the concurrent increasing exhaustion of traditional fossil energy resources has intensified the contradiction between energy supply and demand [1]. Driven by the national “dual-carbon” strategic goals, the transition of the energy structure and the utilization of clean energy have become imperative [2]. Natural gas, as a comparatively clean fossil fuel, plays a pivotal role in this energy transition [3]. China possesses abundant natural gas resources; however, more than 60% of these resources are contained within low-permeability tight gas reservoirs [4]. Such reservoirs are typically characterized by low porosity, low permeability, significant heterogeneity, and substantial development challenges [5]. Consequently, traditional single-layer development technologies often fail to meet the demands for the economically efficient extraction of such resources. Multi-layer commingled production technology is extensively utilized in offshore oil fields, low-permeability gas reservoirs, and complex fault-block reservoirs to enhance single-well productivity and reduce development costs [6,7]. Particularly in the development of low-permeability tight gas reservoirs in western China, the effectiveness of single-layer production is often limited by complex geological conditions. Consequently, multi-layer commingled production technology has become a vital technique for significantly enhancing gas well productivity and extending the stable production period, thereby enabling efficient development in this region [8].

However, during multi-layer commingled production, significant interlayer interference inevitably occurs due to differences in pressure coefficients, permeability, and other physical properties between gas layers, which adversely impacts the overall development efficiency of gas wells [9]. The formation mechanism of interlayer interference, which represents a primary technical challenge in multi-layer commingled production, is predominantly governed by vertical permeability heterogeneity within the reservoir. This heterogeneity can be quantitatively characterized by parameters including the permeability baseline, permeability ratio, and permeability variation coefficient [10,11]. During commingled production, pressure equilibration and fluid redistribution occur among gas layers with distinct pressure coefficients, leading to an uneven productivity contribution from individual layers. This process can even induce interlayer cross-flow, where fluids reflux from high-pressure layers to low-pressure layers [12,13]. This interference effect is inherently dynamic, with its intensity evolving over production time. It is strongly influenced by key development parameters, including water saturation and recovery factor [14].

Current research on interlayer interference primarily advances along two avenues: mathematical simulation and field data analysis [15]. Wu et al. [16] developed a mathematical model to evaluate interlayer interference by integrating multiple factors, including the number of layers, thickness, permeability, porosity, viscosity, and formation pressure. Their study quantified the contribution of various parameters to interlayer interference, revealing that the permeability contrast, production scheme, water-cut stage, and static pressure account for approximately 50%, 25%, 15%, and 10% of the effect, respectively. Through numerical simulation, Zhang et al. [17] established a technical-limit chart for multi-layer commingled production in low-permeability gas reservoirs. Their findings reveal that the favorable operating window for such production is a narrow, diamond-shaped region, implying that commingled production is technically feasible only when the ratios of interlayer pressure coefficients and permeabilities fall within this specific domain. However, current understanding of this phenomenon relies predominantly on theoretical analysis and numerical simulation. A significant gap remains in systematic experimental studies aimed at elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of interlayer interference across varying pressure coefficient conditions.

Experimental research plays an irreplaceable role in the analysis of interlayer interference mechanism. Through oil-water displacement experiments, Zhao et al. [18] established a correlation between the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient and reservoir mobility. This work provided a crucial experimental basis for determining the interlayer interference coefficient. Meanwhile, Tao et al. [19] employed a dynamic inversion method to quantitatively evaluate interlayer interference. They subsequently developed a quantitative prediction model that incorporates key factors, including the oil-water relationship, permeability, effective thickness, and fluid properties. However, most existing experimental studies have focused on the influence of individual factors or specific geological conditions. A systematic investigation into the interference mechanisms governing multi-layer commingled production in gas reservoirs with varying pressure coefficients is notably lacking [20]. Therefore, conducting experimental research on the interference mechanisms in such gas reservoirs is of considerable theoretical and practical importance. It is crucial for elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of interlayer interference, optimizing commingled production parameters, and ultimately enhancing the development efficiency of gas wells.

This study investigates interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production from the Shiqianfeng, Shihezi, and Taiyuan Formations in the low-permeability gas reservoirs of the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin, under varying pressure conditions. A high-temperature, high-pressure physical flow simulation system for multi-layer commingled production was employed. Utilizing this system, experimental schemes simulating commingled production under various pressure conditions were designed. A series of simulation experiments, including single-layer, two-layer, and three-layer commingled production scenarios, were subsequently conducted. The gas production rates and recovery efficiencies from these commingled production experiments were then systematically compared with those obtained from single-layer production tests. This study aims to elucidate the principles governing interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production under varying pressure conditions, thereby providing theoretical support and technical guidance for the efficient development of low-permeability gas reservoirs. The findings are expected to provide an experimental basis and theoretical guidance for optimizing multi-layer commingled production technology in the low-permeability gas reservoirs of the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. Furthermore, they offer technical support and a methodological reference for the rational development of low-permeability tight gas reservoirs under complex geological conditions in Western China. This research holds significant scientific importance and substantial engineering application value for advancing efficient development technologies for low-permeability tight gas reservoirs in China and supporting the national energy security strategy.

2. Experiment Part

2.1. Experimental Principles

To systematically investigate the principles of interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production in low-permeability gas reservoirs under varying pressure conditions, this study established a dedicated experimental system for physical flow simulation. A series of multi-layer commingled production simulations were subsequently conducted using this indoor physical simulation approach. An ISCO precision syringe pump system was employed to maintain a stable displacement pressure during the step-wise production experiment conducted under constant temperature conditions. The pressure decline behavior observed in actual field production was simulated using a precisely regulated back-pressure valve [21]. To capture high-fidelity dynamic data, a computer-based data acquisition system was employed to monitor and record key parameters, including gas flow rates and outlet pressures for each layer, in real time. Through comparative analysis of instantaneous gas production, cumulative gas production, and pressure decline behavior for individual layers under both single-layer and commingled production scenarios, this study systematically elucidates the extent of interlayer interference across varying pressure conditions, the evolution of productivity contributions from each layer, and the associated dynamic equilibrium mechanisms. These findings clarify the key controlling factors behind interlayer interference and the intrinsic mechanisms responsible for productivity variations during commingled production.

2.2. Experimental Materials

Representative core samples from the Shiqianfeng (Q5), Shihezi (H4), and Taiyuan (T2) Formations in the Linxingzhong Block of the Ordos Basin were selected for the experiment. All samples consisted of tight sandstone.

The preparation steps of core samples are as follows:

- (1)

- Using a standard core drilling machine, 40 cylindrical core plug samples measuring 2.5 cm in diameter and 6 cm in length were drilled from the full-diameter core. During drilling and subsequent grinding, coolant was applied to prevent rock particle dislodgement and minimize structural damage, thereby preserving the core’s original physical properties, including pore structure and micro-fracture development.

- (2)

- Following drilling, the core sample requires cleaning and drying to eliminate impurities and native fluids from the pore throats, thereby preparing it for subsequent experimental procedures. The cleaning procedure involves placing the core into a Soxhlet extractor and continuously washing it with organic solvents, such as toluene and methanol, until the reflux solvent becomes colorless and transparent. This ensures the effective removal of hydrocarbons and soluble salts from the core matrix. Drying is subsequently performed by placing the cleaned core in a constant-temperature drying oven and heating it at 65 °C for more than 48 h until a constant weight is achieved. This step guarantees the complete evaporation and removal of any residual fluids from the core pores, ensuring the core is completely dry and establishing a fixed initial water saturation of 0% for the experiments.

- (3)

- The basic physical parameters of the dried core samples, including porosity and permeability, were measured. The total porosity was determined using a helium porosimeter based on Boyle’s law. Gas permeability was measured with a gas permeameter (core holder). Under specific confining pressure and gas flow rate conditions, the gas permeability was calculated utilizing Darcy’s law.

In this study, a total of 40 cylindrical core plug samples were prepared, comprising 15 samples from the Shiqianfeng (Q5) Formation, 10 from the Shihezi (H4) Formation, and 15 from the Taiyuan (T2) Formation. The permeability of these samples ranged from 0.0101 mD to 0.7911 mD, with an average value of 0.3302 mD. To isolate the impact of formation pressure and minimize the influence of permeability heterogeneity, core plugs with closely matched gas permeability values (0.25 ± 0.01 mD) were selectively chosen from the initial pool of 40 samples for the subsequent commingled production experiments. This approach ensures that the observed interlayer interference is primarily driven by the prescribed pressure differences rather than variations in intrinsic permeability. The detailed properties of the core plugs utilized in the commingled experiments are summarized in Table 1 below. Concurrently, the porosity ranged from 2.19% to 9.30%, with an average of 4.47%. High-purity nitrogen gas (99.99%) was used throughout the experimental procedures.

Table 1.

Geometric and physical properties of the core samples used in the commingled production experiments.

2.3. Experimental Installation

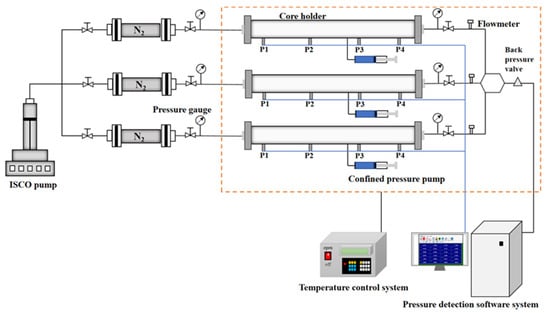

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the experimental data, the high-performance equipment utilized in this study was rigorously selected based on well-defined parameter indicators and demonstrated stable performance. This research employs a multi-layer physical flow simulation system developed by Nantong Huaxing Petroleum Instrument Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China). The system’s design adheres to industry standards, and its technical indicators as well as functional modules were customized to address the specific requirements of this investigation. Consequently, the system configuration is capable of meeting the technical demands for experiments involving single-layer comparative analysis, as well as two-layer and three-layer commingled production scenarios in sandstone formations.

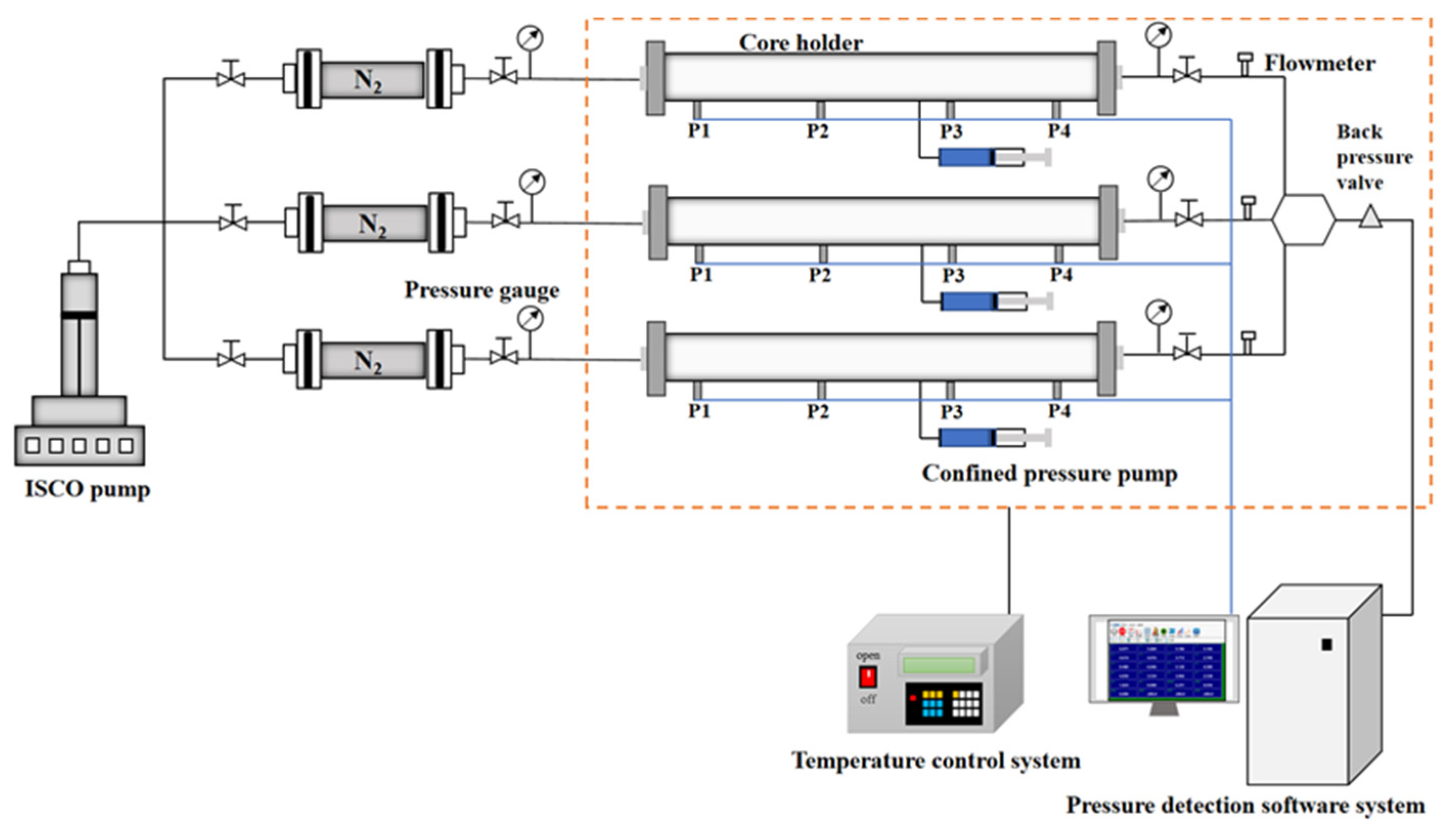

The core experimental setup comprised a Teledyne Isco (Lincoln, NE, USA) 260D precision metering pump, which operated at pressures up to 51.7 MPa and provided a continuous flow rate range of 0.001 to 80 mL/min. A D07 series mass flowmeter (Beijing Qixing Huachuang Electronic Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was employed, with a maximum pressure rating of 20 MPa. The flow totalization was handled by a D08-8CM unit from Beijing Qixing Huachuang Flowmeter Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Pressure data were recorded using a KSB20A0R paperless recorder (Ningbo Keshun Instrumentation Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). A schematic diagram of the complete experimental apparatus is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental device schematic.

2.4. Experimental Design

This experimental design systematically investigates the effects of formation pressure, reservoir physical properties, and commingled production techniques on gas recovery performance. Formation pressure was identified as the primary controlling factor. Three distinct pressure levels—13 MPa, 15 MPa, and 17 MPa—were established to simulate conditions ranging from low-pressure to high-pressure gas reservoirs. Reservoir physical properties were represented by selecting natural core samples from the Shiqianfeng (Q5), Shihezi (H4), and Taiyuan (T2) formations. The permeability of each layer was maintained at approximately 0.2570 mD to isolate and accentuate the impact of interlayer heterogeneity. The commingled production methodology incorporated three scenarios: single-layer production, two-layer commingled production, and three-layer commingled production. Each scenario was applied under various formation pressure combinations to elucidate the principles governing interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production across a range of pressure conditions. The detailed experimental matrix is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental design.

2.5. Experimental Process

This experimental system employs physical simulations of both single-layer and multi-layer commingled production to quantitatively characterize the interlayer interference effects across varying pressure combinations. As a benchmark, single-layer production experiments are initially conducted under conditions devoid of interlayer interference. The specific process is as follows:

- (1)

- Following the confirmation of system airtightness, the pretreated and thoroughly dried natural core sample was placed into a long core holder, and a predetermined confining pressure was applied. The experiments were performed with dry cores (Swi = 0%) to focus exclusively on the gas flow behavior controlled by interlayer pressure differences, without the interference of immobile water.

- (2)

- The outlet valve is then closed, and nitrogen (N2) is injected from the inlet end. The system pressure is subsequently raised to the target formation pressure using an ISCO pump and maintained at a constant level for over 8 h to ensure complete equilibration of the internal pore pressure within the core.

- (3)

- Under a constant temperature of 45 °C, the outlet valve is opened, and the back pressure is gradually reduced to simulate the well production process. Throughout this phase, a computer-based data acquisition system is employed to monitor and record the outlet gas flow rate and pressure dynamics in real time.

- (4)

- A stepwise depressurization protocol was implemented, wherein the pressure was reduced in increments of 3 MPa until reaching an abandonment pressure of 3 MPa (approximately 10% of the initial flowing pressure). Dynamic production data were recorded throughout this process, enabling the generation of curves for instantaneous gas production rate and cumulative gas production. Following the experiment, the core’s integrity was verified to ensure its suitability for subsequent testing.

- (5)

- A series of single-layer production experiments were conducted under three distinct formation pressures (13 MPa, 15 MPa, and 17 MPa) with consistent operating parameters. Each experimental scenario was repeated three times to ensure the consistency and reproducibility of the results, and the data presented are the average values from these parallel tests. After each experiment, the integrity of the core was verified to ensure its suitability for subsequent testing, and these replicated experiments established a reliable set of baseline data that served as a benchmark for the subsequent commingled production experiments.

- (6)

- Building upon the single-layer experiments, multi-layer commingled production experiments were conducted. These included two specific scenarios: a two-layer combination (15–13 MPa) and a three-layer combination (17–15–13 MPa).

- (7)

- Core samples subjected to different pressure conditions are connected in parallel via multiple flow branches to a common outlet pipeline, thereby accurately simulating the downhole commingled production environment within a single wellbore.

- (8)

- The same depressurization production procedure as employed in the single-layer experiments is conducted. A critical distinction lies in the simultaneous monitoring and recording of the inlet pressure and gas production rate for each independent core unit, while the outlet backpressure is maintained at a unified value representative of the commingled production point. This step is essential for capturing the dynamics of interlayer interference.

- (9)

- The analysis focuses on the production performance of individual layers during the initial stage of commingled production. The primary objective is to investigate the occurrence of reverse fluid channeling from high-pressure to low-pressure layers (i.e., the ‘backflow’ effect) and its consequent suppression of productivity in the low-pressure layers. Through these comparative experiments, the extent of interlayer interference during multi-layer commingled production and its impact on the overall recovery efficiency can be systematically quantified.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Single Mining Experiment

3.1.1. Experiment of Yield Change Rule

Following the experimental scheme detailed in Table 2, this study systematically conducted single-layer production experiments on the Q5, H4, and T2 formations. To ensure experimental comparability, key parameters, including permeability and water saturation, were rigorously maintained at consistent levels across all experimental groups. The effects of varying pressure conditions on single-layer production dynamics were investigated through systematic adjustments of the pressure gradient. Utilizing a multi-layer physical flow simulation system, instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates for each layer were monitored in real time. The production response characteristics and dynamic variation patterns of single-layer production under varying pressure conditions were analyzed in depth. This analysis provides a fundamental dataset and a reliable benchmark for subsequent commingled production experiments.

- (1)

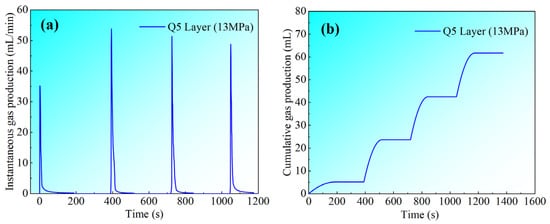

- Q5 single mining

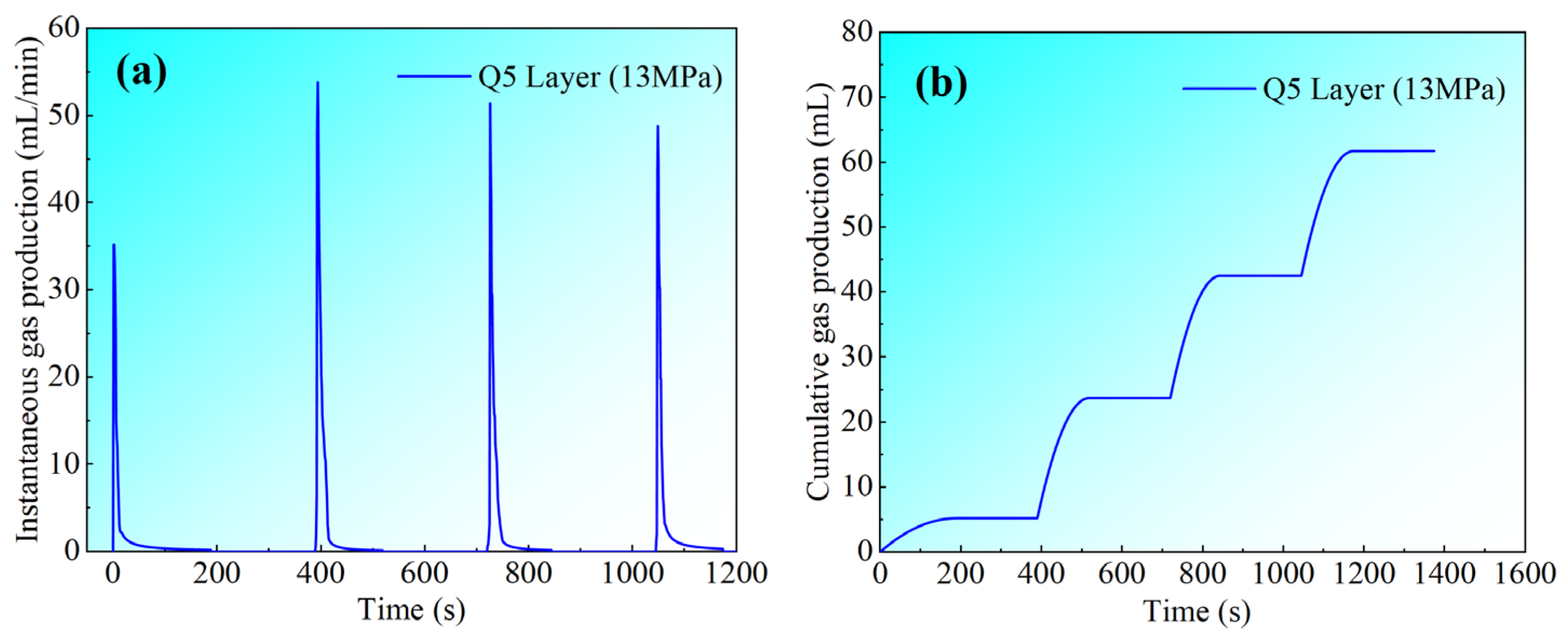

For the Q5 formation experiment, the simulated formation pressure was set at 13 MPa with a confining pressure of 16 MPa. An initial equilibrium period of 1 h was allowed, followed by a stabilization phase lasting 8 h. The initial formation pressure was maintained at 13 MPa. A production simulation was then initiated by gradually reducing the wellhead pressure from 12 MPa. Instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates were systematically monitored following each 3 MPa pressure reduction. The resulting production data are comprehensively presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Yield change of Q5 single layer single mining. (a) Instantaneous gas production rate of Q5 single-well production, (b) Cumulative gas production of Q5 single-well production.

Figure 2 illustrates the dynamic variations in instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates during the four-stage depressurization process for the Q5 formation. As shown in Figure 2a, each reduction in back pressure induced a distinct peak in the instantaneous gas production rate, which occurred at 4 s, 394 s, 726 s, and 1049 s after the initiation of the experiment. The corresponding peak instantaneous gas production rates were 35.2 mL/min, 53.8 mL/min, 51.4 mL/min, and 48.8 mL/min, respectively, yielding an average peak rate of 47.3 mL/min. During non-peak intervals, the instantaneous gas production rate decays rapidly and stabilizes at a low level. Periods characterized by zero instantaneous gas production or a constant cumulative gas production correspond to the shut-in stages. These stages are primarily utilized for system pressure regulation to prepare for the subsequent gas production phase. Figure 2b illustrates a characteristic stepwise increase in cumulative gas production corresponding to the cyclic alternation of well opening and shut-in periods. The gas production process concluded at a production time of 1174 s when the system pressure decreased to the abandonment pressure, yielding a final cumulative gas production of 61.7 mL. From an overview of the entire production process, each depressurization cycle is characterized by an initial rapid surge in cumulative gas production, which subsequently transitions into a relatively stable phase. This pattern establishes a distinct “growth-stationary” alternating evolution model [22]. As the production process advances, the incremental gas production per stage exhibits a gradual decline, reflecting the continuous attenuation of the reservoir’s energy.

- (2)

- H4 single mining

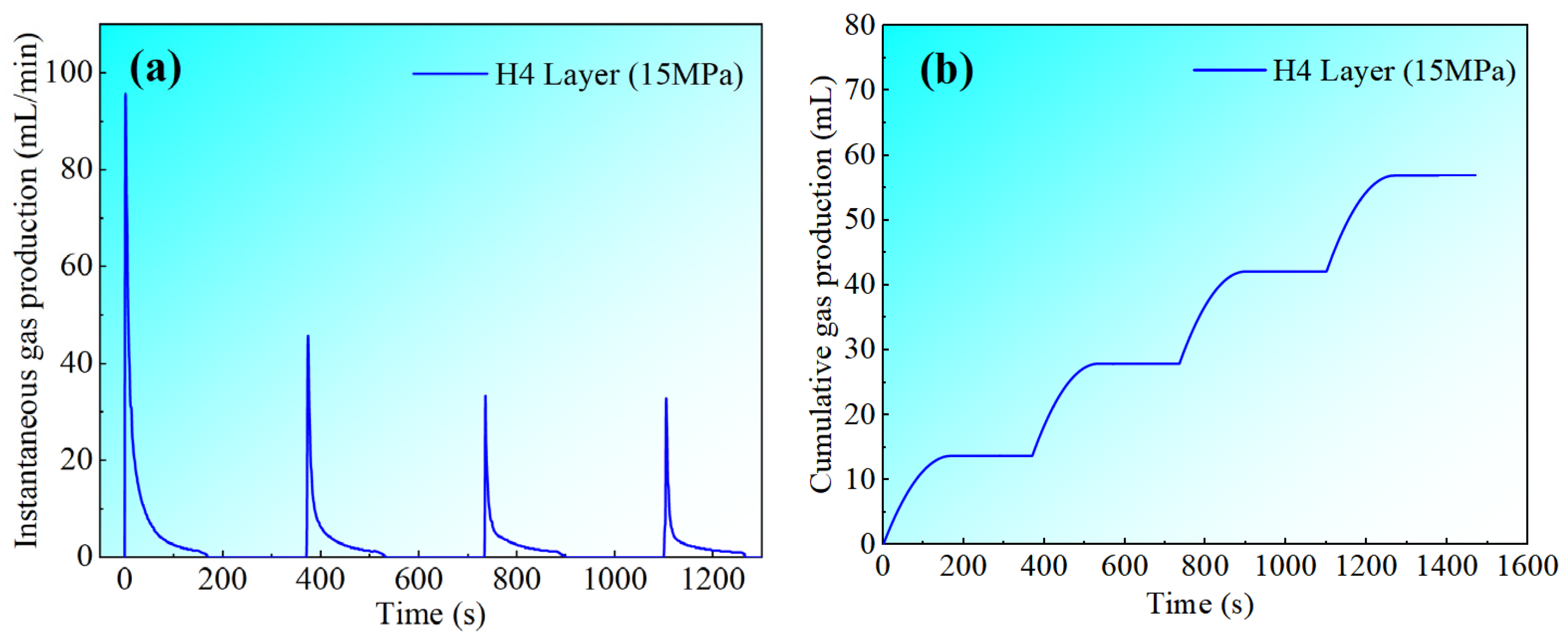

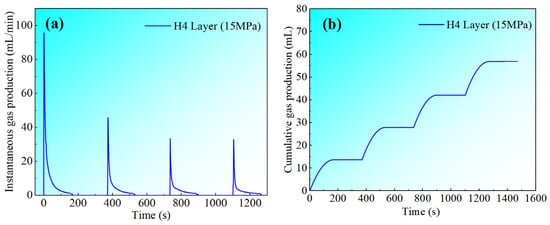

For the H4 formation experiment, the simulated formation pressure was set at 15 MPa with a confining pressure of 18 MPa, and an initial pressure equilibrium period of 7 h was implemented. The formation pressure was maintained at 15 MPa. Subsequently, the wellhead back pressure was gradually reduced from 12 MPa to simulate the production process. Instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates were systematically recorded following each 3 MPa reduction in pressure. The resulting production data are comprehensively presented in Figure 2.

Figure 3 illustrates the dynamic variations in instantaneous and cumulative gas production during the four-stage depressurization process for the H4 formation, following an experimental procedure consistent with that employed for the Q5 formation. As depicted in Figure 3a, distinct gas production peaks occurred at 3 s, 373 s, 736 s, and 1105 s after the initiation of the experiment. The corresponding peak instantaneous gas production rates were 99.8 mL/min, 47.0 mL/min, 42.4 mL/min, and 38.4 mL/min, respectively, yielding an average peak rate of 56.9 mL/min. A comparison with the Q5 formation reveals that the H4 formation exhibited a higher average peak instantaneous gas production rate. This observation indicates that an increase in reservoir pressure enhances the gas production capacity of the reservoir. During non-peak intervals, the instantaneous gas production rate decays rapidly and stabilizes at a low level.

Figure 3.

Yield change of H4 single layer single mining. (a) Instantaneous gas production rate of H4 single-well production, (b) Cumulative gas production of H4 single-well production.

Figure 3b demonstrates that the cumulative gas production exhibits a characteristic stepwise increase, corresponding to the cyclic alternation of well opening and shut-in operations. The gas production process concluded at a production time of 1269 s when the system pressure decreased to the abandonment pressure, resulting in a final cumulative gas production of 56.7 mL.

- (3)

- T2 single mining

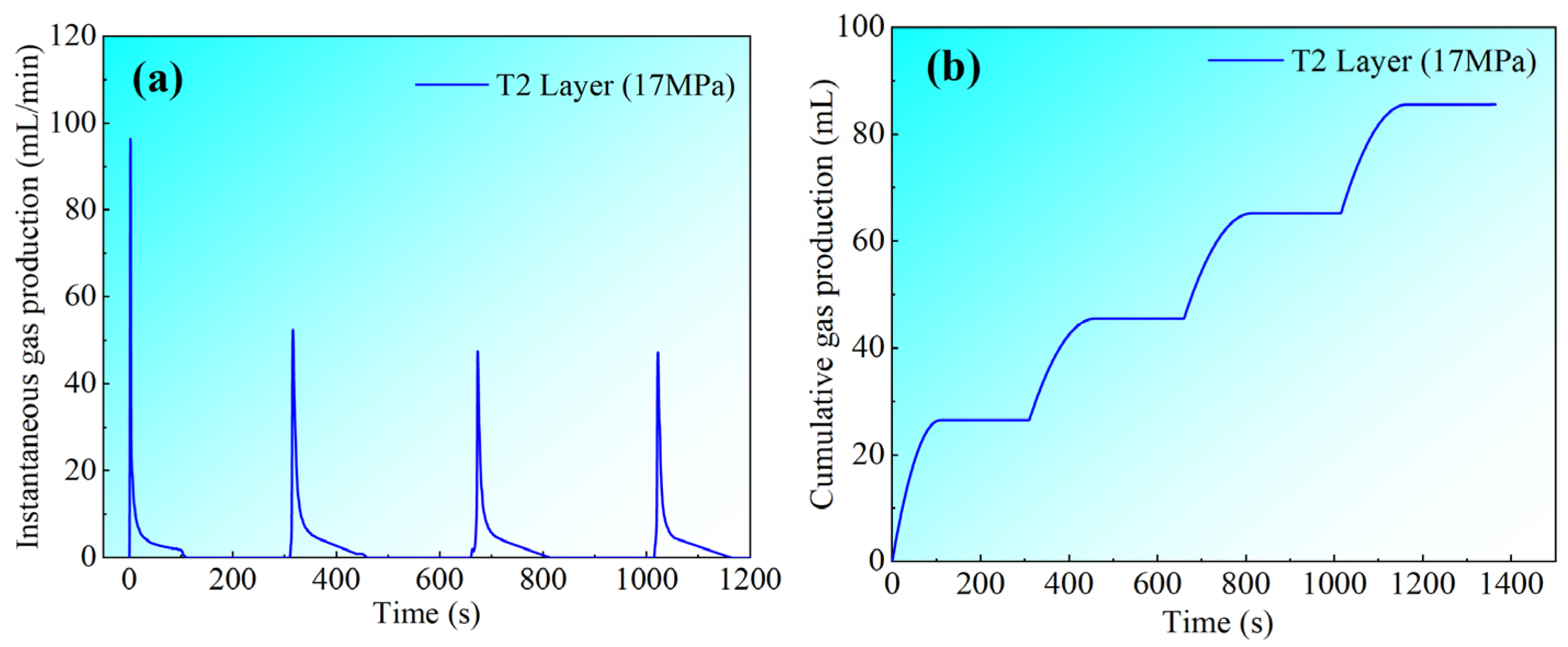

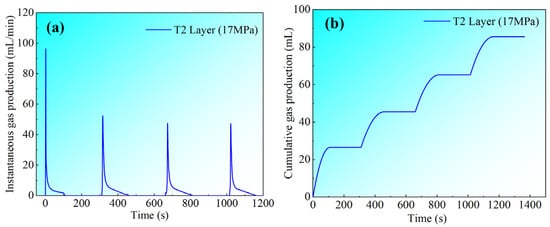

For the T2 formation experiment, the simulated formation pressure was set to 17 MPa with a confining pressure of 20 MPa, and an initial pressure equilibrium period of 4 h was implemented. Subsequently, the wellhead back pressure was gradually reduced from 12 MPa for the gas layer exhibiting a formation pressure of 17 MPa. Instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates were systematically recorded following each 3 MPa reduction in pressure. The resulting production data are comprehensively presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Yield change of T2 single layer single mining. (a) Instantaneous gas production rate of T2 single-well production, (b) Cumulative gas production of T2 single-well production.

Figure 4 illustrates the dynamic variations in instantaneous and cumulative gas production during the four-stage depressurization process for the T2 formation, following an experimental procedure consistent with that employed for the Q5 formation. As depicted in Figure 4a, distinct production peaks occurred at 3 s, 316 s, 673 s, and 1022 s after the initiation of the experiment. The corresponding peak instantaneous gas production rates were 131.38 mL/min, 53.8 mL/min, 51.4 mL/min, and 48.8 mL/min, respectively, yielding an average peak rate of 71.34 mL/min. A comparison with the Q5 and H4 formations reveals that the T2 formation exhibited a significantly higher average peak instantaneous gas production rate. This observation indicates that an increase in reservoir pressure effectively enhances the gas production capacity of the reservoir. During non-peak intervals, the instantaneous gas production rate decays rapidly and stabilizes at a low level. Figure 4b demonstrates that the cumulative gas production exhibits a characteristic stepwise increase, corresponding to the cyclic alternation of well opening and shut-in operations. The gas production process concluded at a production time of 1164 s. when the system pressure decreased to the abandonment pressure, resulting in a final cumulative gas production of 85.56 mL.

This study systematically investigates the gas production dynamics of individual Q5, H4, and T2 sandstone layers under varying pressure conditions through single-layer production experiments. The results demonstrate that all layers exhibit a characteristic response pattern, characterized by a rapid attenuation of instantaneous gas production peaks following each pressure reduction and a stepwise growth behavior in cumulative gas production. As the production process advances, the incremental gas production per stage displays a gradual decline, reflecting the continuous depletion of the reservoir’s energy [23]. A comparative analysis reveals significant differences in the gas production potential among the layers. The T2 formation demonstrates the highest production capacity, followed by H4, while Q5 exhibits a comparatively lower output. This finding underscores the substantial variations in production dynamics under different pressure regimes and provides a critical dataset and a reliable benchmark for subsequent multi-layer commingled production experiments.

3.1.2. Analysis of Yield Change Mechanism

According to the single-layer single-production yield change experiment, the mechanism analysis of the following experimental process can be obtained.

- (1)

- The primary mechanism governing production changes in single-layer mining stems from the depressurization process. Each reduction in back pressure generates an instantaneous high-pressure differential near the wellbore, significantly enhancing the reservoir’s driving energy [24]. This pressure disturbance rapidly disrupts the formation’s original pressure equilibrium, effectively overcoming capillary and flow resistances. This process stimulates gas desorption and creates a high-speed flow channel, resulting in a characteristic peak in instantaneous gas production [25]. For example, in the Q5 formation, peak gas production rates of 35.2 mL/min, 53.8 mL/min, 51.4 mL/min, and 48.8 mL/min were observed at 4 s, 394 s, 726 s, and 1049 s, respectively, during the four-stage depressurization process. Following the production peak, the rapid depletion of gas near the wellbore and the initial re-equilibration of the pressure field cause a swift decrease in the pressure differential. Consequently, gas flow becomes dominated by slow matrix diffusion or supply from more distant regions, leading to a sharp decline in instantaneous gas production. This sequence forms a characteristic response pattern marked by rapid peak attenuation [26].

- (2)

- The stepwise growth pattern of cumulative gas production directly reflects the periodic alternation between open-well production phases and shut-in recovery periods. At the onset of each depressurization stage, the accumulated free gas in the near-wellbore region is rapidly produced, which corresponds to the steep ascending segment of the cumulative production curve [27]. Once this readily available gas volume is largely depleted, and the gas supply rate from the formation interior can no longer sustain high flow rates, production enters a plateau phase. Although the subsequent shut-in phase contributes no direct production, it provides a critical window for formation pressure recovery and gas redistribution from the matrix to the fracture network. This process establishes a new mobile gas source for the next depressurization cycle. This cyclical depletion-recovery mechanism constitutes the fundamental driver behind the observed stepwise growth pattern [28].

- (3)

- As the mining process advances, each layer exhibits a characteristic stepwise decline in gas production increment, demonstrating the continuous attenuation of the reservoir’s internal driving energy [29]. Furthermore, the decrease in pore pressure during production leads to an increase in effective stress, which may cause a reduction in rock permeability. This effect contributes to the observed decline in flow rate under a constant pressure gradient during the later stages of each production cycle. During the initial mining stage, production primarily relies on the readily mobile free gas present in the near-wellbore region. This phase is characterized by abundant formation energy and a substantial driving pressure differential, resulting in high gas production efficiency [15]. As mining progresses to deeper stages, each successive depressurization cycle must access reservoir volumes increasingly farther from the wellbore. This leads to a considerable lengthening of the gas flow path and a corresponding rise in seepage resistance. Concurrently, the average formation pressure is systematically depleted due to continuous extraction, leading to a gradual reduction in the effective production pressure differential achievable during each depressurization cycle [30]. When the system pressure declines to the abandonment pressure, the remaining production pressure differential becomes insufficient to sustain effective gas flow, indicating that the reservoir has reached its economic production limit. This depletion process clearly demonstrates the constraints on movable fluid volumes and drive energy within the reservoir [31]. Comparative analysis reveals that the T2 formation exhibits higher initial energy and a more extensive pressure decline, yet maintains a superior overall productivity level. Conversely, the Q5 formation, characterized by lower initial energy and a more gradual depletion process, demonstrates a significantly lower overall productivity. The consistent decline in incremental gas production observed across each stage underscores the continuous depletion of reservoir energy throughout the production life cycle [32].

3.2. Double-Layer Commingling Experiment

Following the experimental scheme detailed in Table 2, a two-layer commingled production experiment was conducted on the Q5 and H4 formations. Key parameters, including permeability and water saturation, were rigorously maintained at consistent levels throughout the experiment. The primary focus was to investigate the influence of interlayer pressure difference on production performance. A multi-layer commingled production physical flow simulation system was employed to monitor instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates for each layer in real time. This enabled a systematic analysis of the gas production response characteristics and interlayer interference mechanisms under varying pressure conditions, thereby providing an experimental basis for understanding fluid flow behavior during multi-layer commingled production.

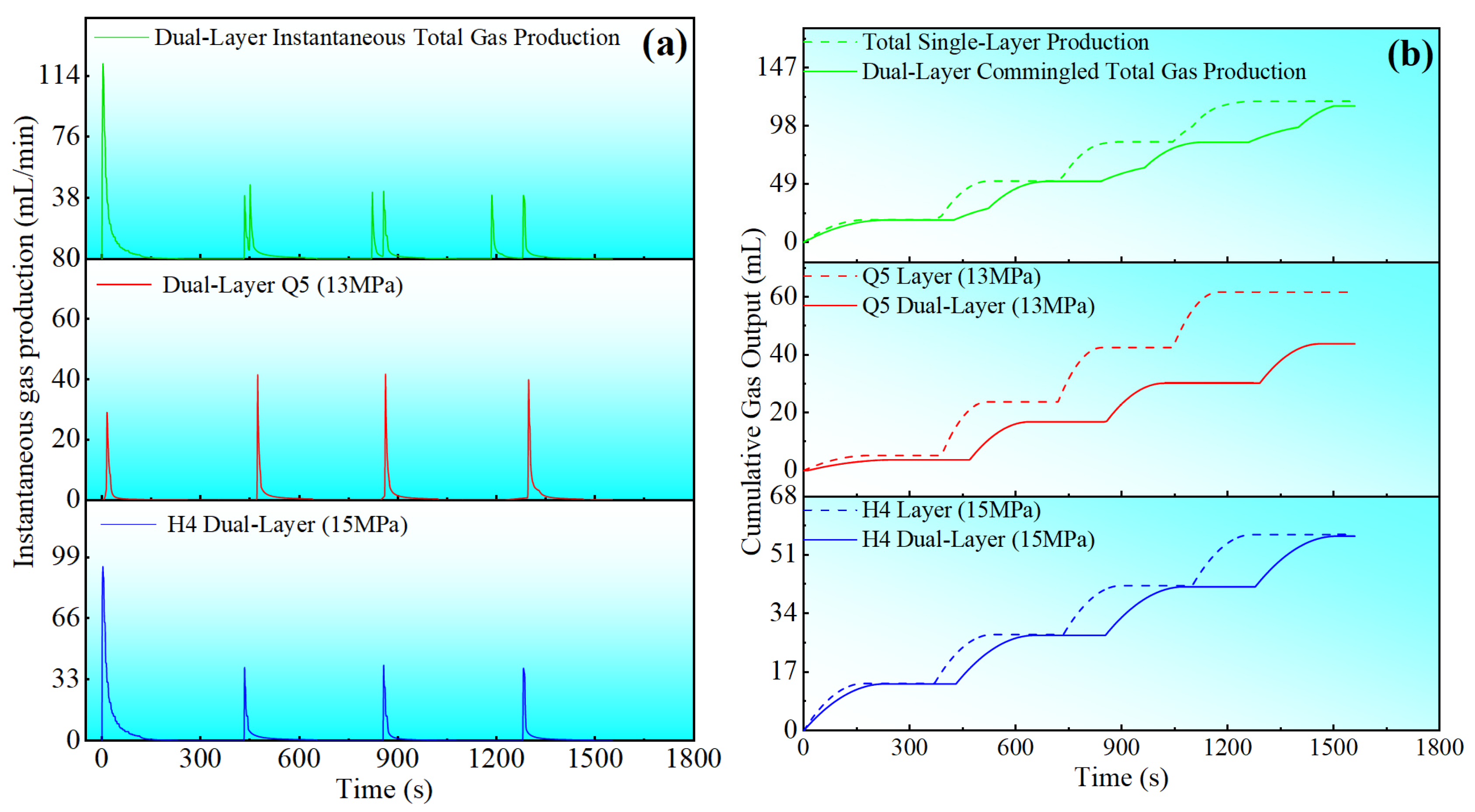

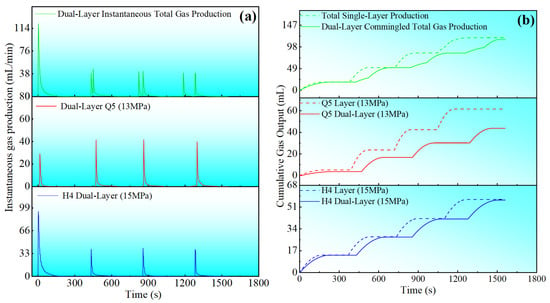

A double-layer commingled production experiment was conducted on the Q5 and H4 formations to systematically analyze production dynamics and interlayer interference effects. The initial pressure imbalance observed when connecting multiple cores—where pressure in some cores decreases while it transiently increases in others—is analyzed as a result of rapid system equilibration. Upon connection, the high-pressure layer (H4) releases fluid not only towards the wellbore but also backwards into the connected low-pressure layer (Q5) due to the initial large pressure differential. This “backflow” effect temporarily increases the pressure in the low-pressure core while decreasing it in the high-pressure core, directly suppressing the early-time productivity of the low-pressure layer. The formation pressures were set at 13 MPa for the Q5 layer and 15 MPa for the H4 layer. The wellhead back pressure was gradually reduced to the abandonment pressure of 3 MPa in stepwise increments of 3 MPa.

Figure 5a demonstrates that, compared to single-layer production conditions (See Figure 2 and Figure 3), both the instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates for the two layers in the commingled production system exhibited varying degrees of reduction. Notably, the production peak of the Q5 formation (low-pressure layer) consistently occurred later than that from the H4 formation (high-pressure layer), exhibiting a distinct “staggered peak production” phenomenon. This temporal misalignment is a direct manifestation of dynamic interlayer interference. The high-pressure layer (H4) rapidly establishes a pressure depletion zone upon well opening due to its inherent pressure advantage, leading to an early production peak. In contrast, the low-pressure layer (Q5) requires an extended period to develop an effective production pressure differential, resulting in a significantly delayed production peak. Under single-layer production conditions, the peak instantaneous gas production rates for the 15 MPa and 13 MPa layers were 97.32 mL/min and 30.59 mL/min, respectively, underscoring the significant influence of formation pressure on production capacity. In the commingled production scenario, this disparity became more pronounced. During the initial phase of two-layer commingled production, the instantaneous gas production from the high-pressure layer (15 MPa) was significantly greater than that from the low-pressure layer (13 MPa) due to its inherent pressure advantage. Notably, the instantaneous production from the low-pressure layer was zero initially, revealing a typical ‘inversion’ phenomenon. Specifically, the average instantaneous gas production rate for the Q5 formation (the relatively low-pressure layer) decreased from 47.3 mL/min to 42.12 mL/min, representing a reduction of 10.94%. In contrast, the average instantaneous gas production rate for the H4 formation (the relatively high-pressure layer) decreased marginally from 56.9 mL/min to 56.62 mL/min, a reduction of only 0.65%. This indicates a significant inhibitory effect exerted by the high-pressure layer on the production capacity of the low-pressure layer. Further observations indicated that during identical depressurization stages, the peak gas production from the Q5 formation consistently occurred later than that from the H4 formation, exhibiting a distinct “staggered peak production” phenomenon. As the production process advanced, the temporal offset between the two peaks within each stage progressively widened, demonstrating that the interlayer interference effect intensifies over time.

Figure 5.

Yield changes of Q5 and H4 double-layer commingled production. (a) Instantaneous gas production rate of Q5 and H4 dual-well production, (b) Cumulative gas production of Q5 and H4 dual-well production.

Figure 5b illustrates the evolution of cumulative gas production under commingled production conditions. The cumulative gas production exhibits a complex stepwise increase corresponding to the well opening and shut-in cycles. The final cumulative gas production from the commingled production system reached 114.8 mL, which is 3.2% lower than the theoretical sum of 118.6 mL obtained from the two layers under individual production conditions. Analysis of the total output indicates that, despite the presence of interlayer interference, the commingled production system can achieve high overall development efficiency through rational design of the production strategy. The overall recovery efficiency of the commingled production system reaches 96.8% of that achieved by the single-layer production system. This demonstrates that while interlayer interference indeed incurs a production loss, its adverse impact can be significantly mitigated through optimization of key production parameters. Furthermore, significant production lags are observed in both layers within the commingled system, and the magnitude of this lag increases progressively over time. Although the final cumulative gas production from the H4 layer is comparable under both single and commingled production scenarios, a significant production lag is evident during the commingled production process. This observation further confirms that the interlayer interference effect intensifies as production continues.

Based on experimental investigations of two-layer commingled production in the Q5 and H4 formations, this study systematically elucidates the gas production behavior and interlayer interference mechanisms. The fundamental driver of the observed phenomena is the dynamic equilibration of pressure within a connected system. During the initial phase of production, the rapid decrease in wellbore pressure creates a significant pressure sink. Due to the direct hydraulic communication between layers via the wellbore, the high-pressure layer (H4) responds instantaneously, releasing gas towards the wellbore. However, a portion of this driving energy is not solely directed into production but also initiates a ‘backflow’ or reverse invasion into the adjacent low-pressure layer (Q5). This occurs because, at the moment of well opening, the near-wellbore region of the low-pressure layer presents a path of relatively lower resistance compared to the longer flow path from the high-pressure layer’s interior, leading to a transient pressure balancing effect. Consequently, the low-pressure layer experiences a delay in establishing a favorable pressure gradient for production, manifesting as the observed ‘staggered peak production’ [33,34,35].

As production advances, the continuous depletion of overall system energy exacerbates this interference [36]. The energy loss in the low-pressure layer due to the initial backflow means it requires a longer time to accumulate sufficient mobile gas and pressure to contribute meaningfully to production in each subsequent depressurization cycle. This temporal misalignment, rooted in the energy redistribution between layers, intensifies over time and directly diminishes the overall production efficiency. The quantified cumulative production loss of 3.2% compared to the summed single-layer production is a direct manifestation of this inefficient energy utilization and the ineffective drainage of a portion of the reserves in the low-pressure layer [37,38].

3.3. Three-Layer Combined Mining Experiment

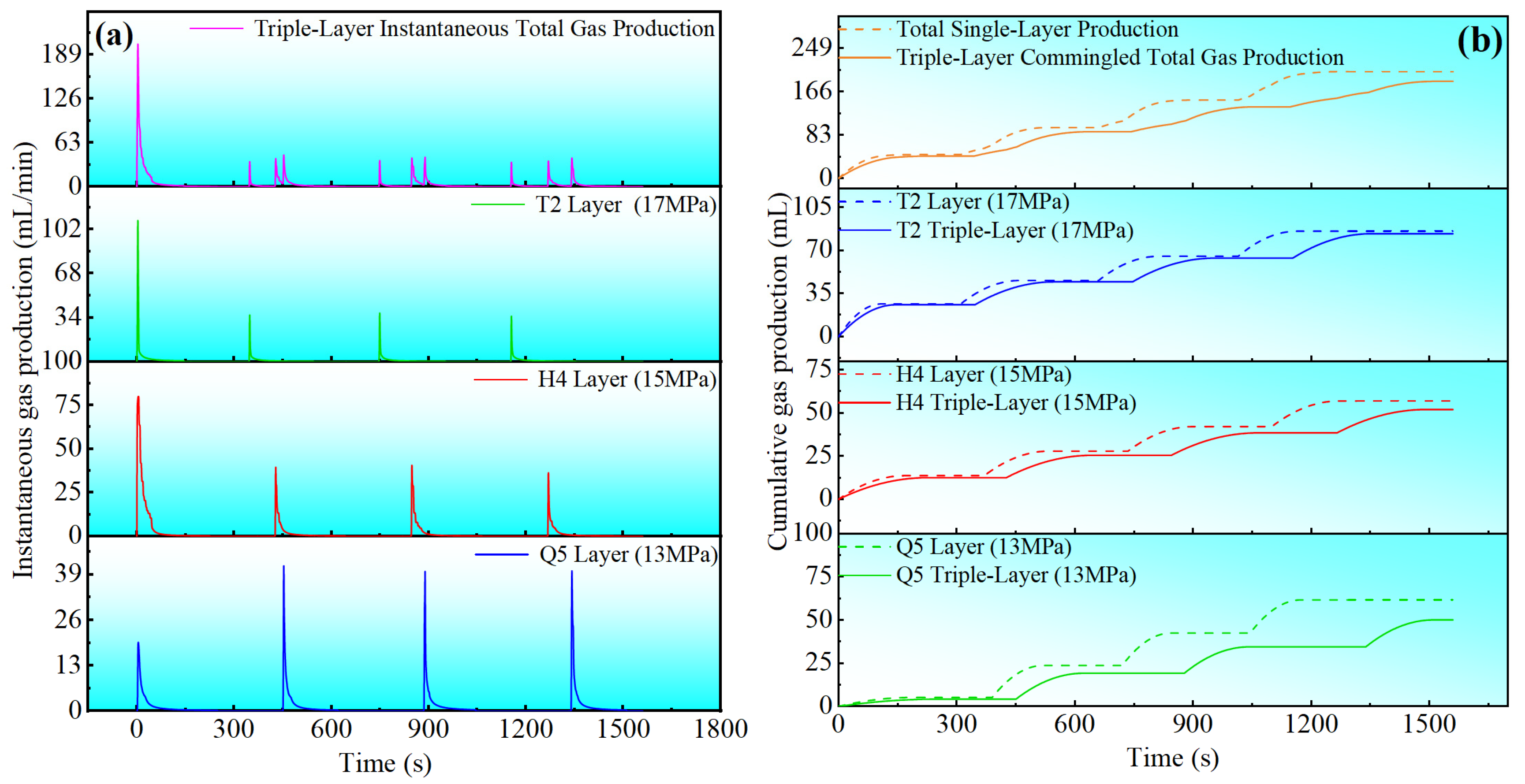

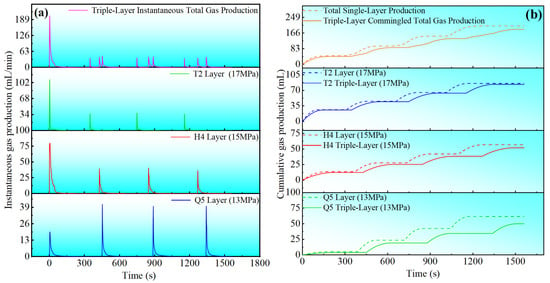

Building upon the insights gained from double-layer commingled production studies, a physical simulation of three-layer commingled production was conducted to investigate the cumulative effects and dynamic behavior of interlayer interference under more complex reservoir conditions. This section presents a detailed analysis of the experimental results for the three-layer system involving the T2, H4, and Q5 formations with respective formation pressures of 17 MPa, 15 MPa, and 13 MPa, as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Yield changes of Q5, H4 and T2 three-layer commingled production. (a) Instantaneous gas production rate of Q5, H4 and T2 triple-well production, (b) Cumulative gas production of Q5, H4 and T2 triple-well production.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the three-layer commingled production system exhibits more complex interlayer interference characteristics compared to the double-layer system. During the initial phase of commingled production, the peak instantaneous gas production rate in the high-pressure layer (17 MPa) reached 126.77 mL/min, significantly exceeding the rates of 80.16 mL/min in the medium-pressure layer (15 MPa) and 20.12 mL/min in the low-pressure layer (13 MPa). This finding is consistent with the results from the double-layer commingled production experiments, further confirming the dominant role of formation pressure in governing production capacity distribution.

Figure 6a demonstrates that, compared to single-layer production conditions (refer to Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), both the instantaneous and cumulative gas production rates for the three layers in the commingled production system exhibit varying degrees of reduction. Specifically, the average instantaneous gas production rate for the Q5 formation (the relatively low-pressure layer) decreased from 47.3 mL/min to 38.13 mL/min, representing a reduction of 19.87%. Similarly, the average instantaneous gas production rate for the H4 formation (the relatively medium-pressure layer) decreased from 56.9 mL/min to 51.04 mL/min, corresponding to a 10.46% reduction. In contrast, the average instantaneous gas production rate for the T2 formation (the relatively high-pressure layer) decreased marginally from 71.34 mL/min to 68.21 mL/min, a reduction of only 4.39%. This indicates a significant inhibitory effect of the high-pressure layer on the production capacity of the low-pressure layer. Further analysis reveals that at identical depressurization stages, the production peak of the Q5 layer lags behind that of H4, which in turn exhibits a noticeable lag behind the T2 layer, forming a distinct three-layer ‘staggered peak production’ phenomenon. As the production process advances, the temporal disparity between consecutive peaks within the same stage progressively widens, demonstrating that the interlayer interference effect intensifies over time. Figure 6b illustrates the evolution of cumulative gas production under commingled production conditions. The cumulative gas production exhibits a complex stepwise increase corresponding to the cyclic well opening and shut-in operations. The final cumulative gas production from the commingled production system reached 185.67 mL, which is significantly lower than the theoretical sum of 204.16 mL for the three layers produced individually, corresponding to a production reduction rate of 9.06%. Furthermore, significant production lags are observed across the three layers in the commingled system. The temporal disparity of these lags increases progressively over time, demonstrating an intensification of the interlayer interference effect.

The three-layer commingled production experiment reveals that the interference effect is not merely additive but exhibits superposition characteristics [39,40]. This amplification can be attributed to the formation of a more complex, multi-pathway pressure interference network. In the three-layer system, the highest-pressure layer (T2) exerts a dominant inhibitory effect on both the medium-pressure (H4) and low-pressure (Q5) layers. Critically, the medium-pressure layer (H4) itself acts as both a victim of T2’s suppression and a source of suppression for the Q5 layer. This creates a cascade effect where the interference mechanisms observed in the two-layer case are compounded.

The wider the pressure span and the greater the number of layers, the more challenging it becomes for the system to reach an efficient dynamic equilibrium [41]. The low-pressure layer (Q5) in this hierarchical pressure structure is subjected to sustained suppression from multiple sources, leading to a more severe and prolonged delay in its production contribution and a significantly greater productivity reduction (19.87%) compared to the two-layer scenario. The overall production loss of 9.06% underscores the systemic efficiency loss in such multi-layer systems, highlighting that the superposition of interference effects leads to a non-linear increase in productivity impairment.

This finding reveals two critical characteristics of interlayer interference in three-layer commingled production. First, the degree of interference exhibits a negative correlation with formation pressure; consequently, gas layers with lower pressure experience more severe production inhibition. Second, the interference effect demonstrates superposition characteristics, where the inhibition severity for the medium-pressure layer in the three-layer system is significantly greater than that observed in two-layer commingled production.

3.4. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

While this study elucidates the fundamental mechanisms of interlayer interference dominated by pressure difference under controlled laboratory conditions, several aspects warrant further investigation to enhance field applicability. The experimental setup maintained constant temperature and utilized homogeneous sandstone cores, thus excluding the dynamic effects of environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations or seismic activities. Furthermore, the influence of reservoir heterogeneity, including lithological variations and natural fractures, as well as the impact of different hydraulic fracturing techniques, was not considered in this physical model. Future research should integrate geological models to quantify the thresholds of these factors. Additionally, the high-resolution experimental dataset provided in this study (e.g., the dynamic production curves in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) serves as a valuable benchmark for developing machine learning and AI-based predictive models for interlayer interference. Lastly, investigating the coupled effects of chemical or biological processes on long-term permeability and interference behavior represents another critical direction for future study.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Systematic physical simulation experiments were conducted to elucidate the interference mechanisms governing multi-layer commingled production under varying formation pressure conditions. A comparative analysis of single-layer and multi-layer commingled production experiments revealed significant interlayer interference during the commingled extraction of gas layers exhibiting distinct initial pressure differentials. Experimental results demonstrate that commingled production exerts an inhibitory effect on the total gas recovery efficiency. The cumulative gas production losses for two-layer and three-layer commingled production were quantified at 3.2% and 9.06%, respectively, with a more pronounced adverse impact on the productivity of low-pressure reservoirs.

- (2)

- This study elucidates the mechanism of the backflow phenomenon in multi-layer commingled production under varying pressure conditions. This phenomenon directly suppresses gas production from low-pressure layers, and the magnitude of this suppression escalates with increasing interlayer pressure differential.

- (3)

- The findings of this study provide an experimental basis for optimizing the development of low-permeability gas reservoirs. To translate these insights into practical applications, future work should focus on (a) assessing the long-term economic impact of interlayer interference on development strategies; (b) developing real-time monitoring and intelligent completion technologies based on the identified interference signatures (e.g., backflow and staggered peaks) for effective management; and (c) combining with numerical simulation to establish technical limits for commingled production under complex geological conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, B.Z.; formal analysis, H.M.; investigation, C.W. (Chao Wei); data curation, B.W. and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F.; writing—review and editing, C.W. (Chen Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 14th Five-Year Plan Major Project (Key Technologies for Onshore Unconventional Natural Gas Exploration and Development) (KKGG-2021-1000),the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52374041), the Key Research and Development Projects of Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-YBGY-306), and the Key Research Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (No. 22JY054).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yu Su, Bing Zhang, Honggang Mi, Bo Wang, Le Sun and Tianyu Fu were employed by the China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd. Author Chao Wei was employed by the COSL-EXPRO Testing Services (Tianjin) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Qin, B.; Wang, H.; Li, F. Towards zero carbon hydrogen: Co-production of photovoltaic electrolysis and natural gas reforming with CCS. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, N. Improved relative permeability models incorporating water film effects in low and ultra-low permeability reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 16218–16239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, L.; Zhang, X. Impact of Demographic Age Structure on Energy Consumption Structure: Evidence from Population Aging in Mainland China. Energy 2023, 273, 127226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ju, S.; Xue, Y. China’s Energy Transitions for Carbon Neutrality: Challenges and Opportunities. Carbon Neutrality 2022, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, N. A Statistical Review of Considerations on the Implementation Path of China’s “Double Carbon” Goal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, K.; Xu, Y. Low-Carbon Transformation of Power Structure under the “Double Carbon” Goal: Power Planning and Policy Implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 66961–66977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Lu, S. Dynamic Comprehensive Evaluationof the Development Level of China’s Greenand Low Carbon Circular Economyunder the Double Carbon Target. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 33, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Van, D.H.K.; Haghighi, M. A new approach for production forecasting from individual layers in multi-layer commingled tight gas reservoirs. APPEA J. 2022, 62, S192–S195. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, A.; Wei, Y.; Guo, Z. Development Status and Prospect of Tight Sandstone Gas in China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2022, 9, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Co-production strategy and its influencing factors for stacked gas reservoirs. Fuel 2026, 404, 136171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Xue, W.; Guo, Z. Development of Large-Scale Tight Gas Sandstone Reservoirs and Recommendations for Stable Production—The Example of the Sulige Gas Field in the Ordos Basin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, J.; Leung, C. Opportunities and Challenges for Gas Coproduction from Coal Measure Gas Reservoirs with Coal-shale-tight Sandstone Layers: A Review. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2025, 4, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia, R.I.; Aagaard, T.F.; Gutierrez, V.S. Co-production of bioinsecticide and biochar from sunflower edible oil waste: A preliminary feasibility study. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okere, C.J.; Sheng, J.J.; Fan, L.K. Experimental study on the degree and damage-control mechanisms of fuzzy-ball-induced damage in single and multi-layer commingled tight reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 3598–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, J. Feasibility Analysis of Commingle Production of Multi-Layer Reservoirs in the High Water Cut Stage of Oilfield Development. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y. Layered Production Allocation Method for Dual-Gas Co-Production Wells. Energies 2025, 18, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Song, J. A Model of Pressure Distribution along the Wellbore for the Low Water-Producing Gas Well with Multilayer Commingled Production. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, X.S.; Chen, Z.Y. Numerical Investigation of Production Characteristics and Interlayer Interference during Co-Production of Natural Gas Hydrate and Shallow Gas Reservoir. Appl. Energy 2024, 354, 122219. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Okere, C.J.; Su, G. Experimental and Theoretical Evaluation of Interlayer Interference in Multi-Layer Commingled Gas Production of Tight Gas Reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.G.; Li, Y.Y.; Hua, X.L. Research on the Basic Theory and Application of Enhanced Recovery in Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoirs. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41306. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liang, Y. Evaluation Model of Water Production in Tight Gas Reservoirs Considering Bound Water Saturation. Processes 2025, 13, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhina, E.; Afanasev, P.; Mukhametdinova, A. A novel method for hydrogen synthesis in natural gas reservoirs. Fuel 2024, 370, 131758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukharova, T.; Maltsev, P.; Novozhilov, I. Development of a control system for pressure distribution during gas production in a structurally complex field. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; He, W.; Wang, J. Experimental Study on Interlayer Interference Characteristics during Commingled Production in a Multilayer Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoir. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Huang, X.; Deng, X. A Production Splitting Model of Heterogeneous Multi-Layered Reservoirs with Commingled Production. J. Porous Media 2023, 26, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, J.; Chan, T.G.L.; Mohammed, A. Towards flexible large-scale, environmentally sustainable methanol and ammonia co-production using industrial symbiosis. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Pusarapu, V.; Narayana, S.R.; Ochonma, P. Sustainable co-production of porous graphitic carbon and synthesis gas from biomass resources. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, C.; Du, J. Inter-Layer Interference in Commingled Tight Gas Reservoirs: Experiments and Simulations. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Tao, H. An Analytical Model Coupled with Orthogonal Experimental Design Is Used to Analyze the Main Controlling Factors of Multi-Layer Commingled Gas Reservoirs. Water 2023, 15, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, E.; Cheng, D. Characteristics of Energy Evolution and Acoustic Emission Response of Concrete under the Action of Acidic Drying-Saturation Processes Cycle. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 74, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Prabhudesai, V.S.; Vinu, R. Catalytic upcycling of post-consumer multilayered plastic packaging wastes for the selective production of monoaromatic hydrocarbons. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119630. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Aibaibu, A.; Wu, Y. Numerical Modeling of Hydraulic Fracturing Interference in Multi-Layer Shale Oil Wells. Processes 2024, 12, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seier, M.; Archodoulaki, V.M.; Koch, T. The morphology and properties of recycled plastics made from multi-layered packages and the consequences for the circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107388. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, B.R.; Zhao, Y.L. Inter-Layer Interference for Multi-Layered Tight Gas Reservoir in the Absence and Presence of Movable Water. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, F.; Wei, C.; Li, R. Reservoir Damage in Coalbed Methane Commingled Drainage Wells and Its Fatal Impact on Well Recovery. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, F.; Chen, G.; Tang, M. Analysis and Optimization of Wellbore Structure Considering Casing Stress in Oil and Gas Wells within Coal Mine Goaf Areas Subject to Overburden Movement. Processes 2025, 13, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Wu, D. Enhanced gas production from silty clay hydrate reservoirs using multi-branch wells combined with multi-stage fracturing: Influence of fracture parameters. Fuel 2024, 357, 129705. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, J.T.; White, J.A.; Hamon, F.P. Managing reservoir dynamics when converting natural gas fields to underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Skelly, B.P.; Rota, C.T.; Kolar, J.L. Mule deer mortality in the northern Great Plains in a landscape altered by oil and natural gas extraction. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 88, e22619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Optimizing unconventional gas extraction: The role of fracture roughness. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 036611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Li, J.; Liu, K. Numerical evaluation of commingled production potential of marine multilayered gas hydrate reservoirs using fractured horizontal wells and thermal fluid injection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.